↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many reinforcement learning algorithms struggle to learn multiple ways to achieve a goal, limiting their adaptability to complex and dynamic environments. Existing methods often parameterize policies in a way that restricts learning to a single behavior mode, hindering their versatility. This is especially problematic when dealing with sparse rewards, which are common in real-world scenarios.

The paper introduces Deep Diffusion Policy Gradient (DDiffPG), which utilizes diffusion models to address these issues. DDiffPG uses a novel actor-critic algorithm that learns multimodal policies by explicitly discovering, preserving, and improving multiple behaviors. The algorithm incorporates mode-specific Q-learning to overcome the limitations of traditional RL methods and uses unsupervised clustering to discover different behaviors. Empirical evaluations showcase its capability to master diverse behaviors in high-dimensional continuous control tasks with sparse rewards, showcasing improved sample efficiency and successful online replanning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to training multimodal policies in reinforcement learning using diffusion models. This addresses a significant limitation of current RL methods, which often struggle to learn diverse behaviors. The proposed method, DDiffPG, not only learns multimodal policies but also explicitly controls and improves these multiple modes, which has significant implications for applications in robotics, continuous control, and other fields.

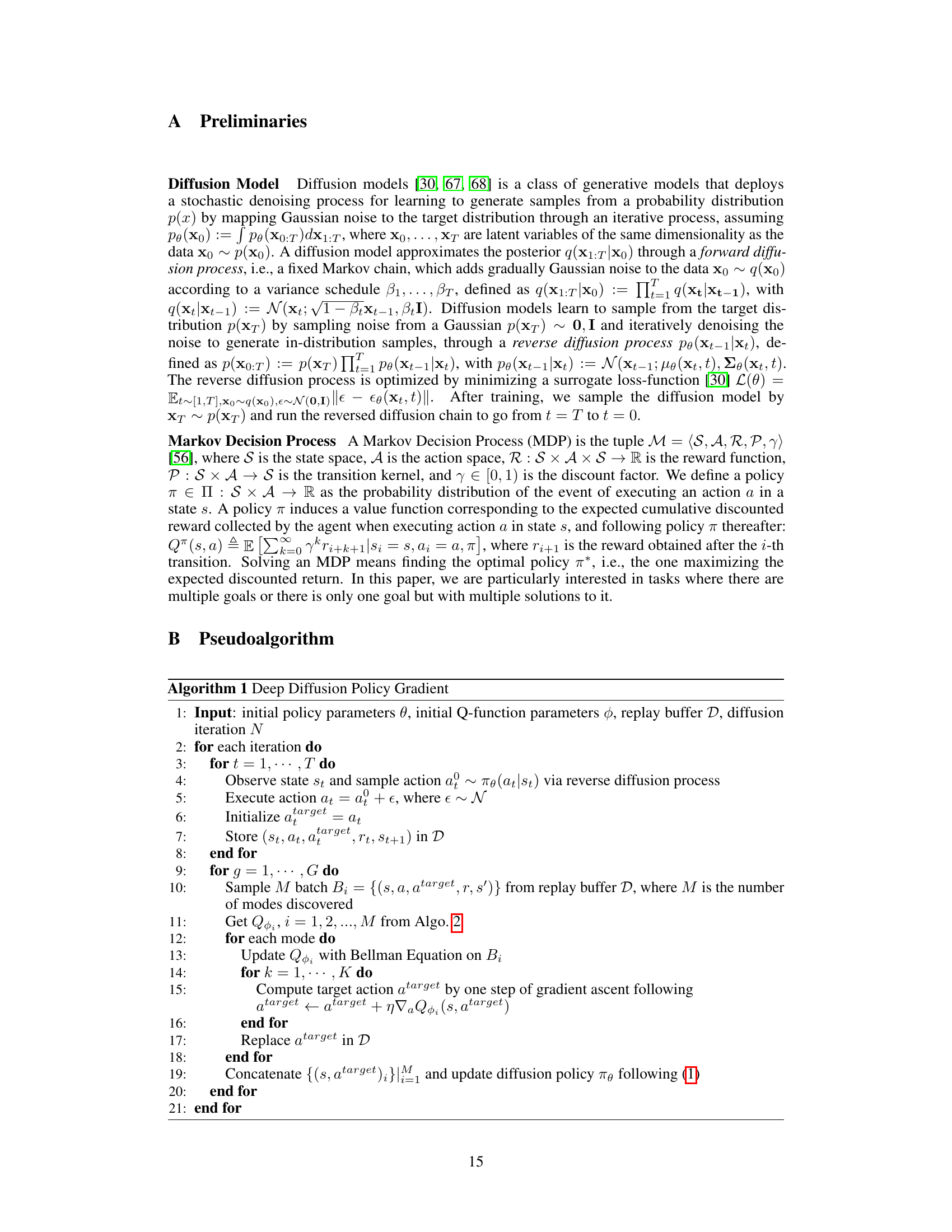

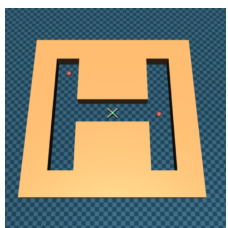

Visual Insights#

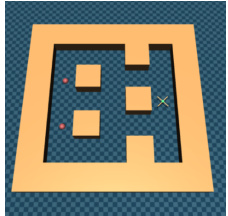

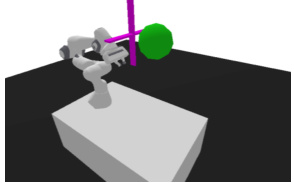

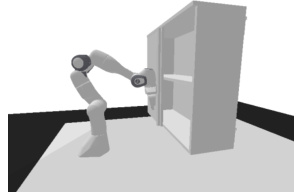

This figure shows the eight different tasks used to evaluate the proposed multimodal policy learning algorithm, DDiffPG. The top row displays four variations of the AntMaze environment, each with a different maze layout, designed to test the agent’s ability to find multiple paths to the goal. The bottom row shows four robotic manipulation tasks: Reach (reaching for an object), Peg-in-hole (inserting a peg into a hole), Drawer-close (closing a drawer), and Cabinet-open (opening a cabinet). These tasks were selected to present challenges requiring multiple strategies or diverse solutions to complete successfully.

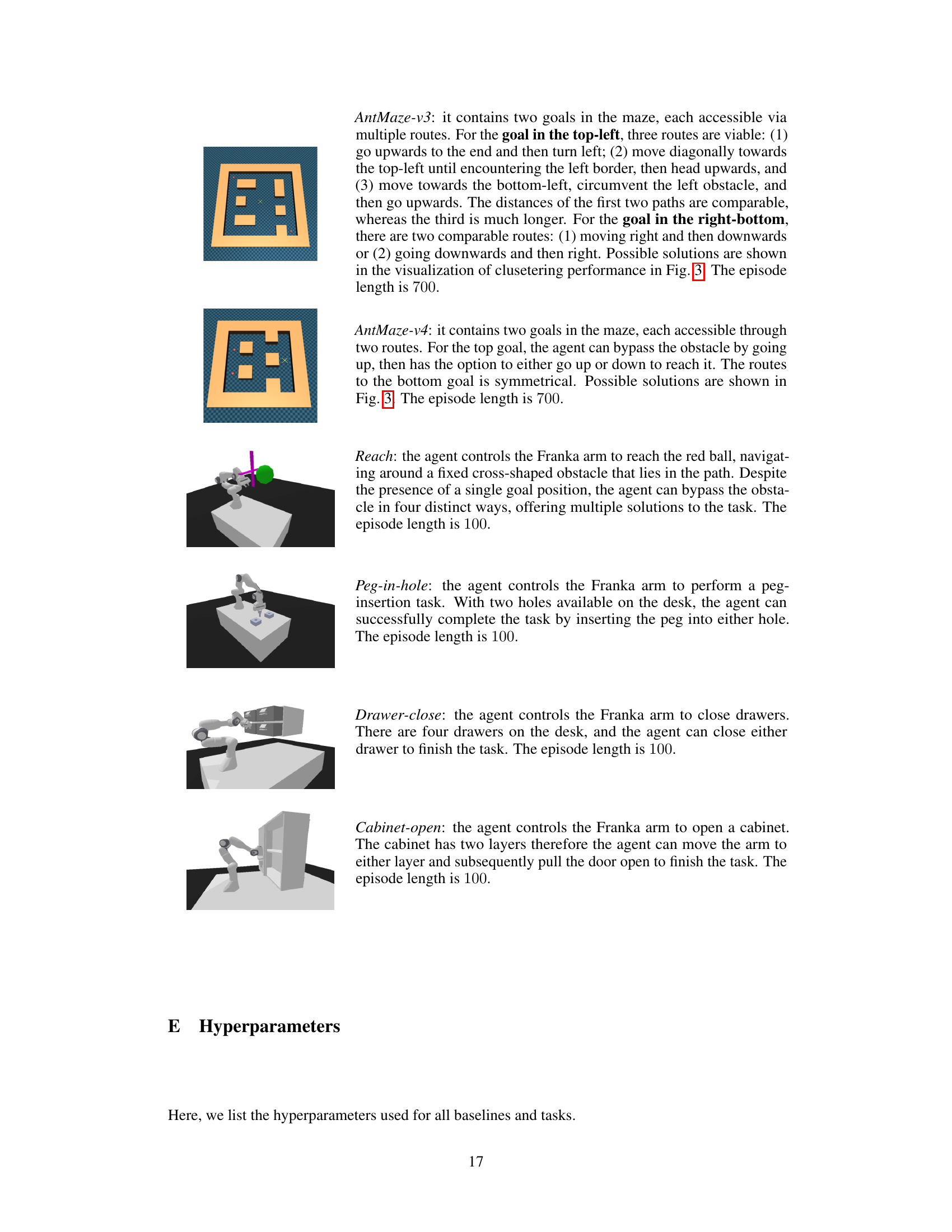

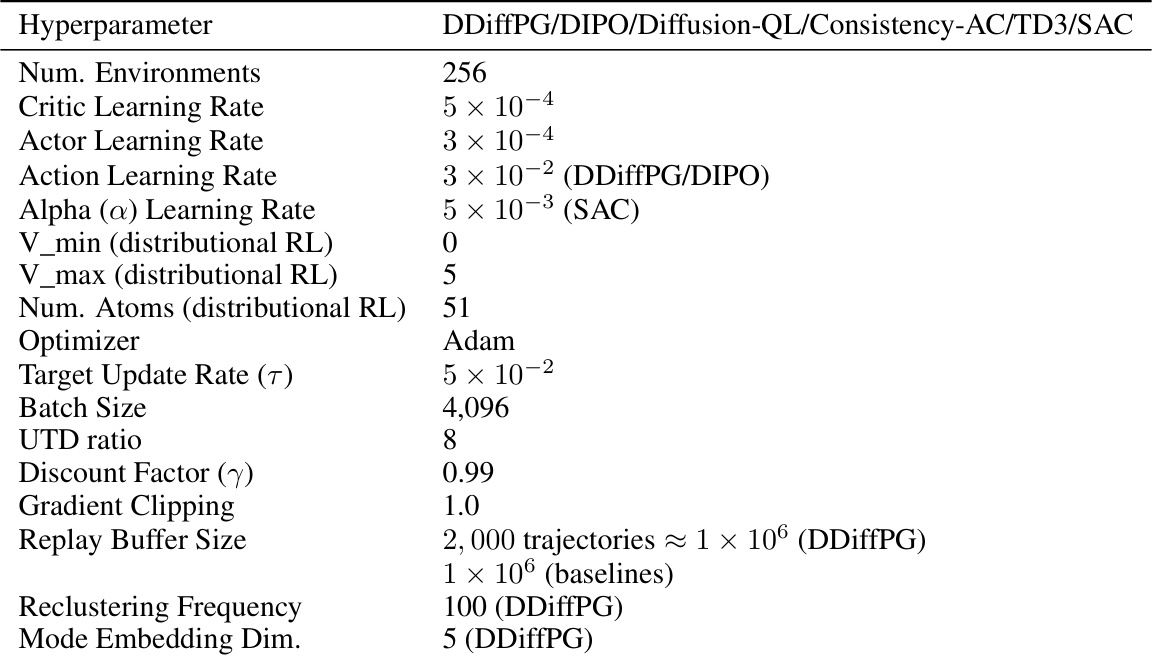

This table lists the hyperparameters used for all baselines and tasks in the experiments. It shows values for parameters such as the number of environments, learning rates (critic, actor, and action), alpha learning rate (for SAC), V_min and V_max for distributional RL, the number of atoms, the optimizer used, target update rate, batch size, UTD ratio, discount factor, gradient clipping, replay buffer size, reclustering frequency, and mode embedding dimension. Note that separate hyperparameters are given for DDiffPG/DIPO/Diffusion-QL/Consistency-AC/TD3/SAC and for RPG.

In-depth insights#

Multimodal Policy#

A multimodal policy, in the context of reinforcement learning, allows an agent to learn and execute multiple distinct behaviors or strategies to achieve a goal. This contrasts with traditional single-mode policies that typically restrict an agent to a single approach. The advantages are significant, enabling adaptability in dynamic or uncertain environments. A key challenge lies in effectively exploring and exploiting these diverse behaviors. The exploration-exploitation dilemma is exacerbated because greediness in RL algorithms might cause the policy to converge prematurely to a single, locally optimal behavior, ignoring potentially superior strategies. Therefore, methods for explicitly discovering and maintaining multiple modes, preventing mode collapse, are crucial. Techniques such as novelty-based exploration and unsupervised clustering can be used to discover modes, while mode-specific Q-learning can help mitigate the greediness of the RL objective. The ability to condition the policy on mode-specific embeddings allows for explicit control over the selection of behaviors. Overall, a multimodal policy offers significant advantages in terms of robustness, flexibility, and efficiency in complex tasks, though requires careful consideration of exploration, exploitation and mode maintenance.

Diffusion Gradient#

The concept of “Diffusion Gradient” in the context of reinforcement learning presents a novel approach to training diffusion models for policy optimization. It directly addresses the challenges of approximating policy likelihood and mitigating the inherent greediness of RL methods that often lead to unimodal policies. By cleverly generating a target action using gradient ascent on the Q-function and training the diffusion model using a behavioral cloning objective, the method avoids the vanishing gradients often encountered in direct backpropagation. This allows for learning multi-modal policies, crucial for adaptability and robustness in complex environments. The effectiveness hinges on the ability to learn multiple behavior modes through off-policy training, avoiding the pitfalls of single mode exploitation. Furthermore, this framework lays a foundation for explicitly controlling learned modes through conditioning, enabling dynamic online replanning. Overall, the “Diffusion Gradient” approach shows promise for improving sample efficiency and enhancing the versatility of RL agents, particularly in scenarios demanding multimodal behaviors and online adaptation.

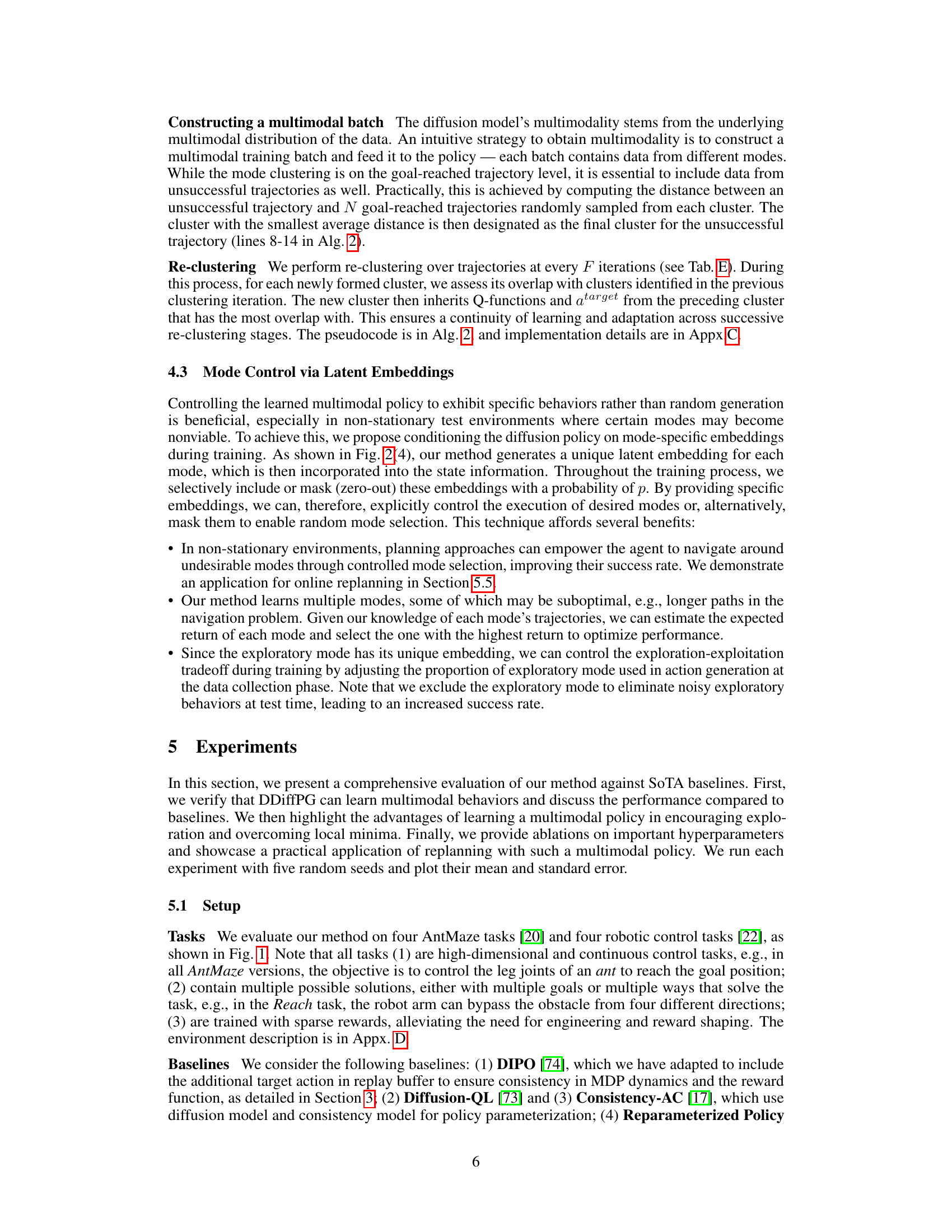

Mode Discovery#

The concept of ‘Mode Discovery’ in this context centers on identifying and leveraging diverse behavioral modes within a multimodal policy. The authors cleverly avoid relying on pre-defined modes, instead opting for an unsupervised approach. This is achieved using a combination of novelty-based intrinsic motivation to encourage exploration and hierarchical trajectory clustering to group similar behaviors. The novelty-based exploration uses a technique that rewards the agent for visiting novel state-space regions. The hierarchical clustering method groups trajectories based on their similarity, using dynamic time warping (DTW) to account for variations in trajectory length. This dynamic and data-driven approach to mode discovery is a key strength, allowing the algorithm to adapt to different tasks and discover the optimal number of modes without human intervention. It contrasts with existing methods that often rely on pre-defined or latent-variable-based mode representations. The resulting mode-specific representations facilitate the training of mode-specific Q-functions and enable explicit mode control through conditional policy embeddings.

Online Replanning#

The concept of ‘Online Replanning’ within the context of a multimodal policy is particularly insightful. It leverages the agent’s ability to learn and maintain multiple behavioral modes to dynamically adapt to unforeseen changes in the environment. The key to success lies in the explicit mode control mechanism, enabling the agent to selectively choose a suitable behavior mode when encountering unexpected obstacles. Instead of getting stuck in suboptimal solutions, the multimodal policy allows for graceful transitions between modes until a successful route is discovered. This contrasts sharply with single-mode approaches, which often fail when encountering unanticipated obstacles. The online replanning demonstrates the robustness and adaptability of a multimodal policy in non-stationary environments, making it a powerful tool for complex real-world applications where pre-planning is infeasible or limited. The ability to seamlessly switch modes based on environmental feedback demonstrates an impressive level of flexibility and adaptability. This approach highlights a fundamental advantage of multimodal learning over traditional unimodal systems, proving to be more efficient and effective in dynamic, challenging scenarios. The success of this approach underscores the importance of incorporating explicit mode control within the framework of multimodal reinforcement learning for achieving enhanced robustness and adaptability.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section suggests several promising avenues. Extending online replanning with more sophisticated long-horizon planners is crucial for complex tasks. The current approach uses a brute-force method, which is inefficient for long-horizon scenarios. Exploring methods to efficiently orchestrate the learned modes is a key area for improvement. Another avenue is bridging offline and online learning, leveraging offline data to improve initial policy performance. The authors point out that offline datasets may contain suboptimal trajectories, so fine-tuning with online RL while preserving previously learned modes is important. Finally, the paper proposes focusing on open-ended learning in large-scale, complex environments. This involves continually acquiring diverse and useful skills beyond simply achieving specific goals. This is a significant challenge, requiring exploration of advanced skill discovery and learning techniques. Overall, the suggested future directions focus on enhancing the efficiency, adaptability, and scalability of the proposed multimodal learning framework for real-world applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

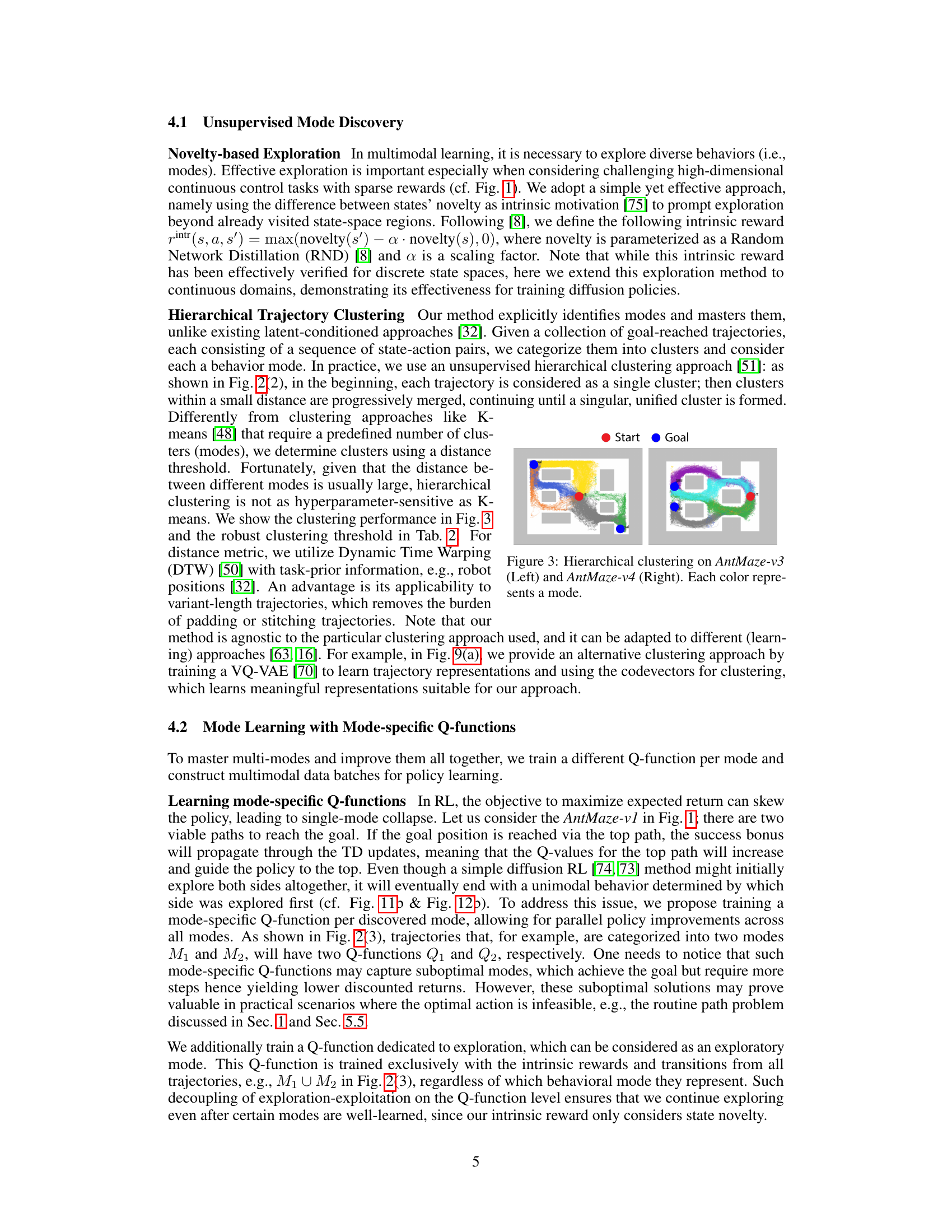

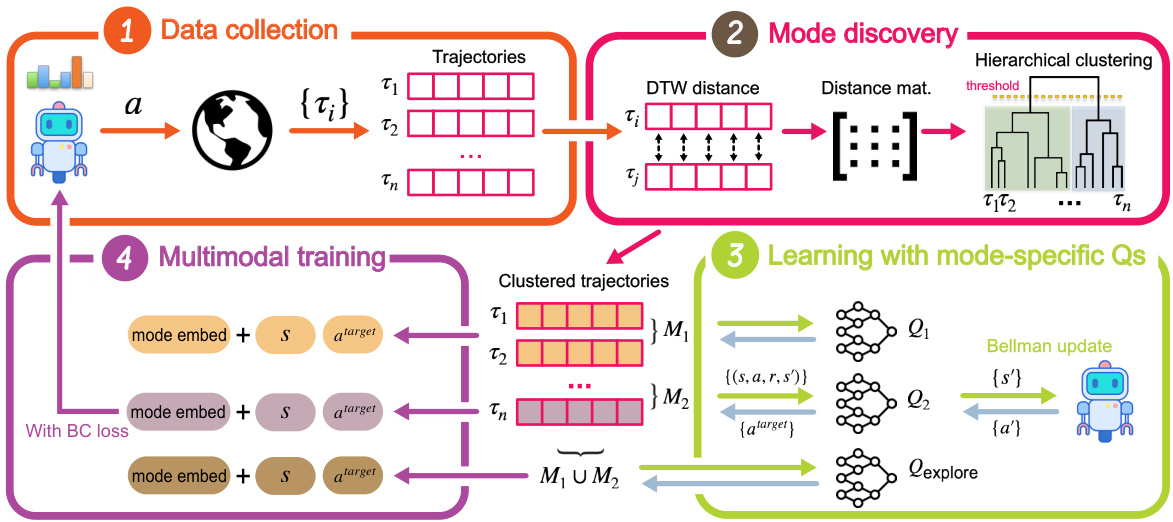

This figure illustrates the Deep Diffusion Policy Gradient (DDiffPG) algorithm’s workflow. It starts with data collection where the agent interacts with the environment. Then, mode discovery is performed using hierarchical clustering on goal-reached trajectories based on dynamic time warping (DTW) distances. Mode-specific Q-functions, including one for exploration, are trained for each identified mode. Finally, multimodal training is performed using batches constructed from all modes to update the diffusion policy.

This figure shows eight different tasks used to evaluate the proposed multimodal reinforcement learning algorithm. The top row displays four variations of the AntMaze environment, each presenting a unique navigational challenge with multiple potential solutions. The bottom row illustrates four robotic manipulation tasks: Reach, Peg-in-hole, Drawer-close, and Cabinet-open. These tasks also involve multiple ways to successfully complete the task, highlighting their multimodality and suitability for evaluating algorithms capable of learning diverse behaviors.

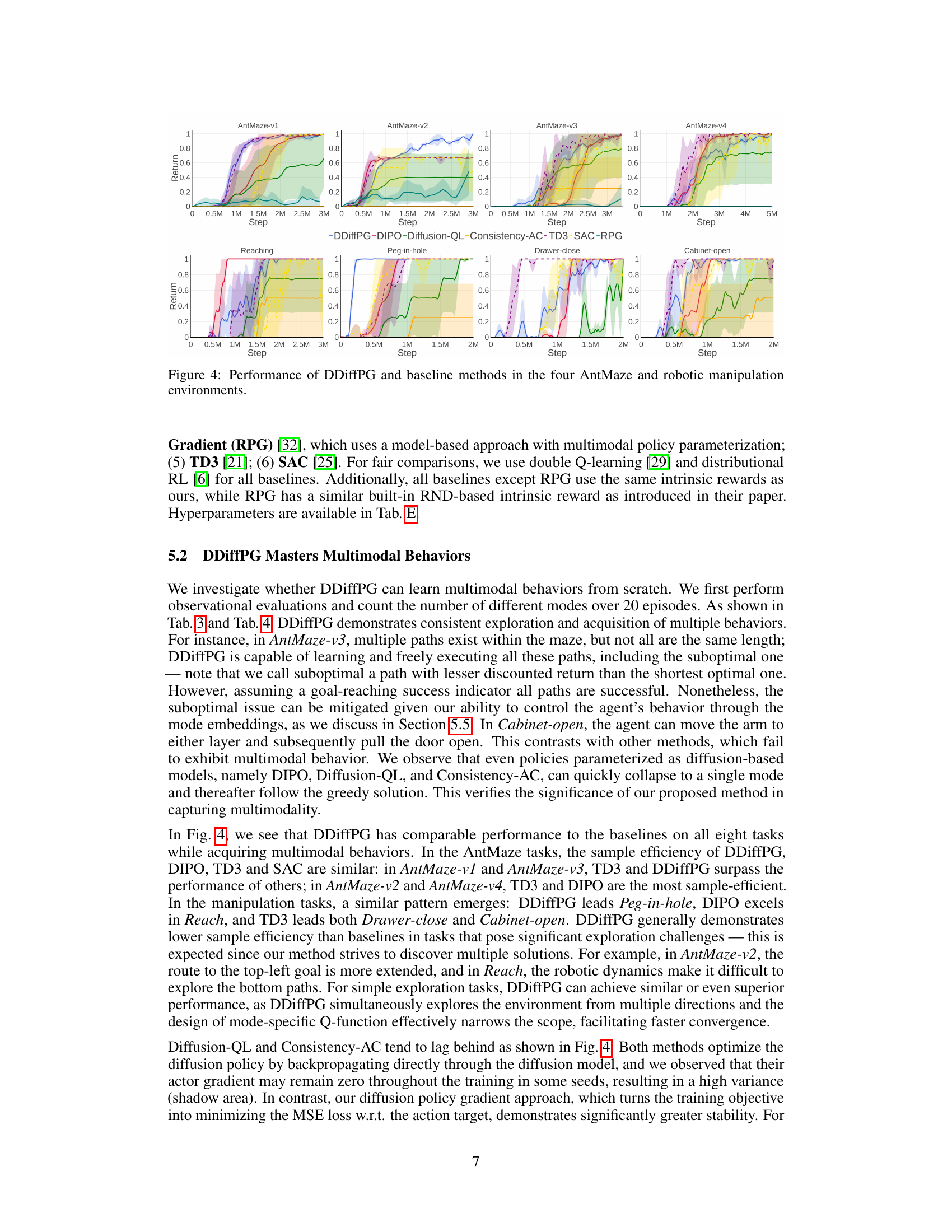

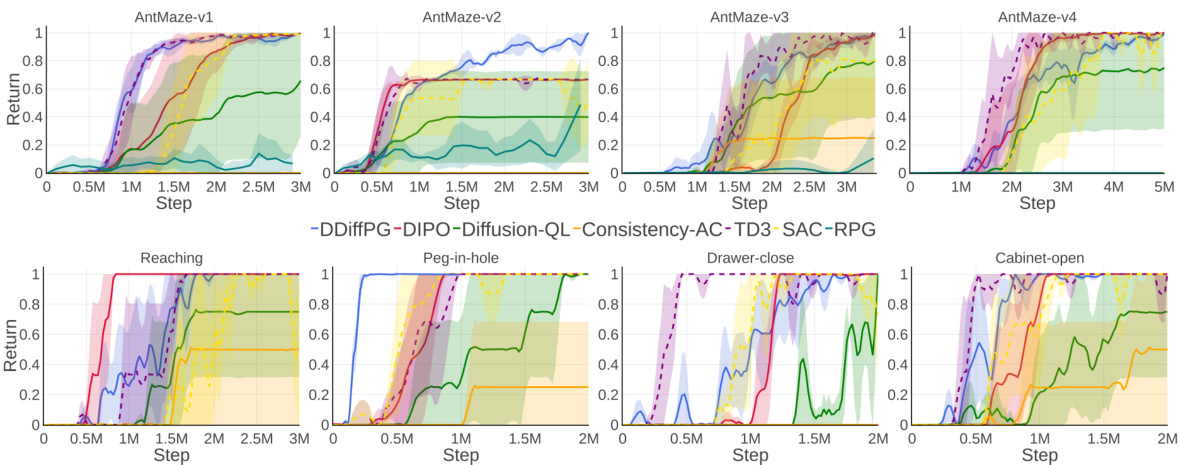

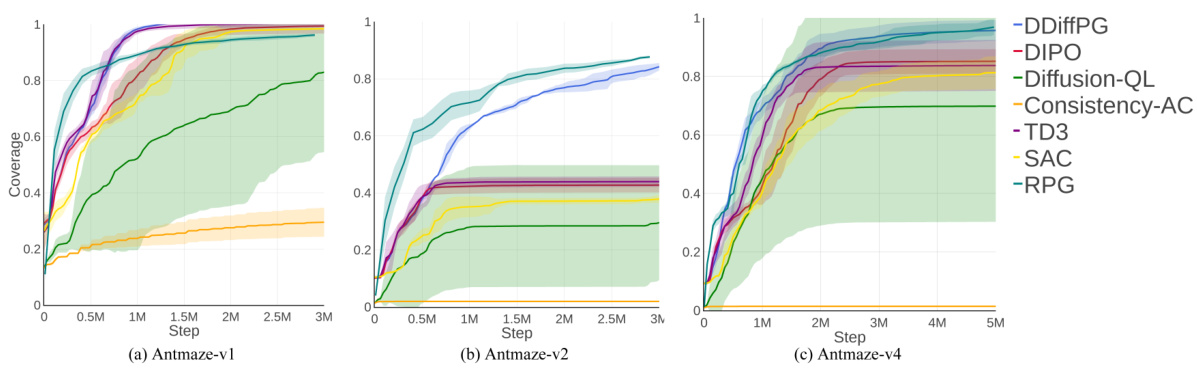

The figure shows the learning curves of DDiffPG and several baseline methods across four AntMaze environments and four robotic manipulation tasks. Each subplot represents a different environment or task, showing the average return (cumulative reward) over training steps. The plot visualizes the relative performance of DDiffPG compared to other state-of-the-art reinforcement learning algorithms. The shaded areas indicate the standard error. This figure helps demonstrate DDiffPG’s ability to learn and achieve good performance in complex control tasks compared to other algorithms.

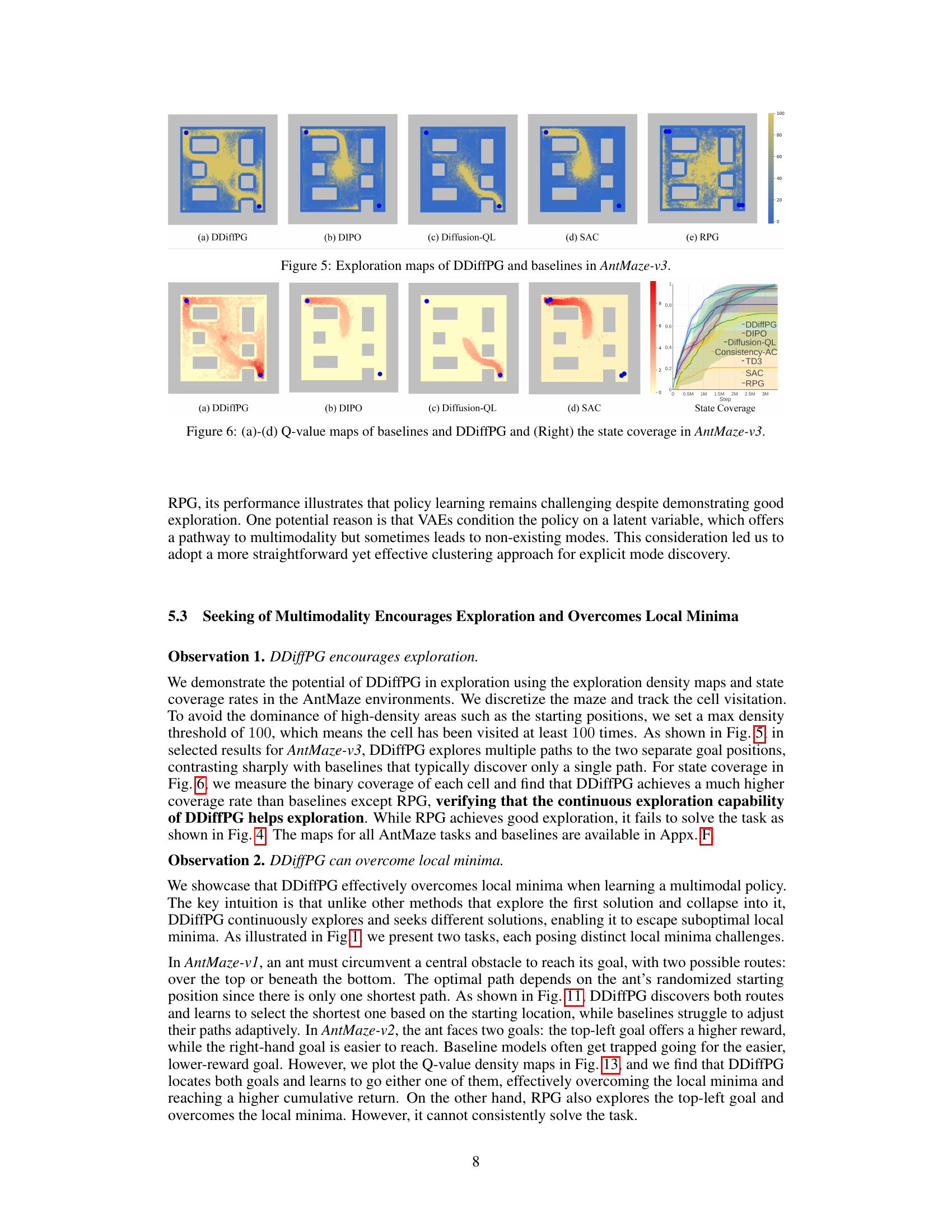

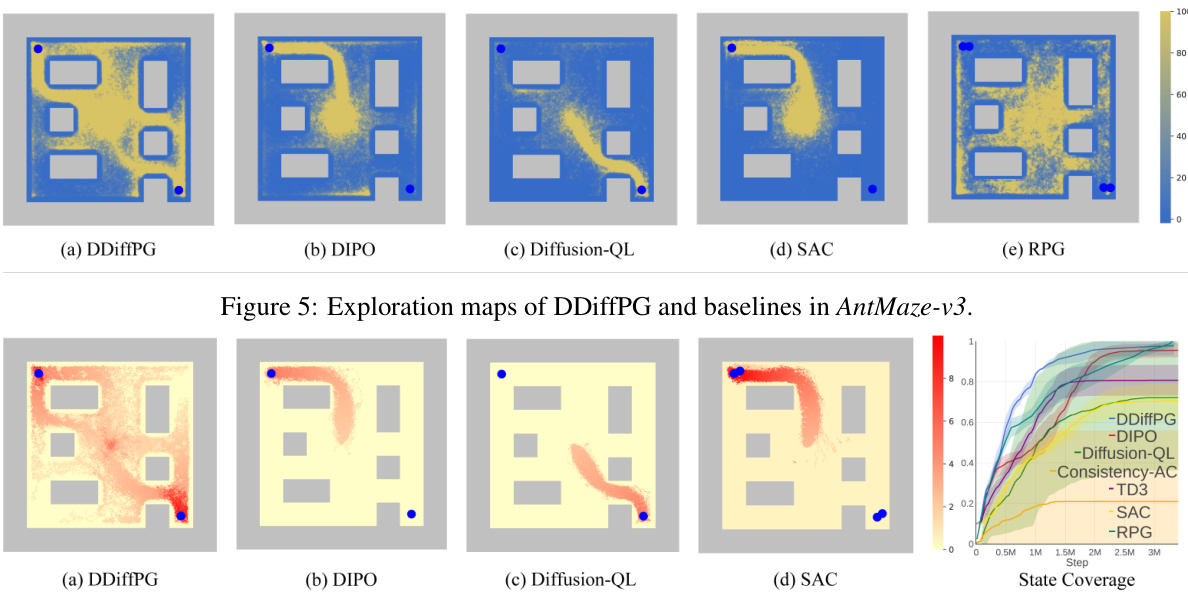

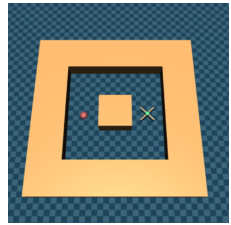

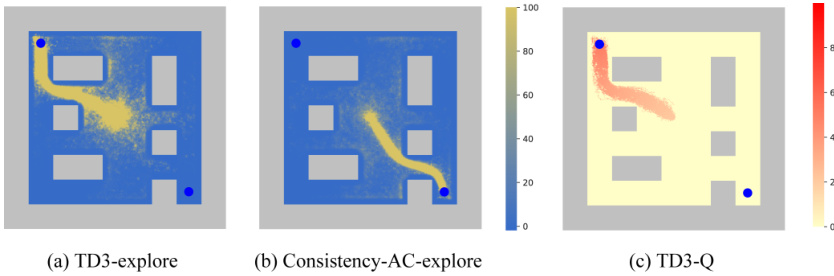

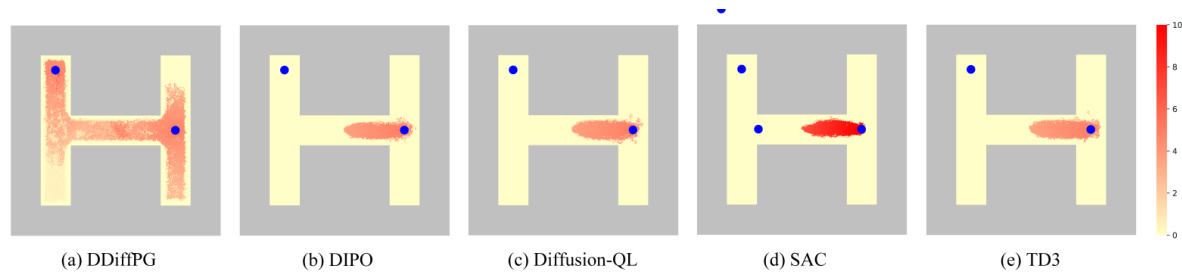

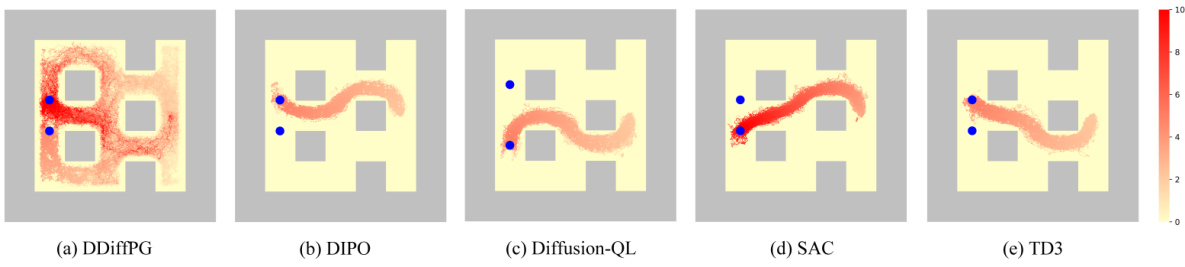

This figure visualizes the exploration patterns of different reinforcement learning algorithms in the AntMaze-v3 environment. Each subfigure shows a heatmap representing the frequency of agent visits to different locations within the maze. The color intensity indicates the number of times each cell was visited, providing insight into the exploration strategy of each algorithm. Comparing the exploration maps helps understand the strengths and weaknesses of each algorithm concerning its ability to explore the environment thoroughly and discover different paths to the goal.

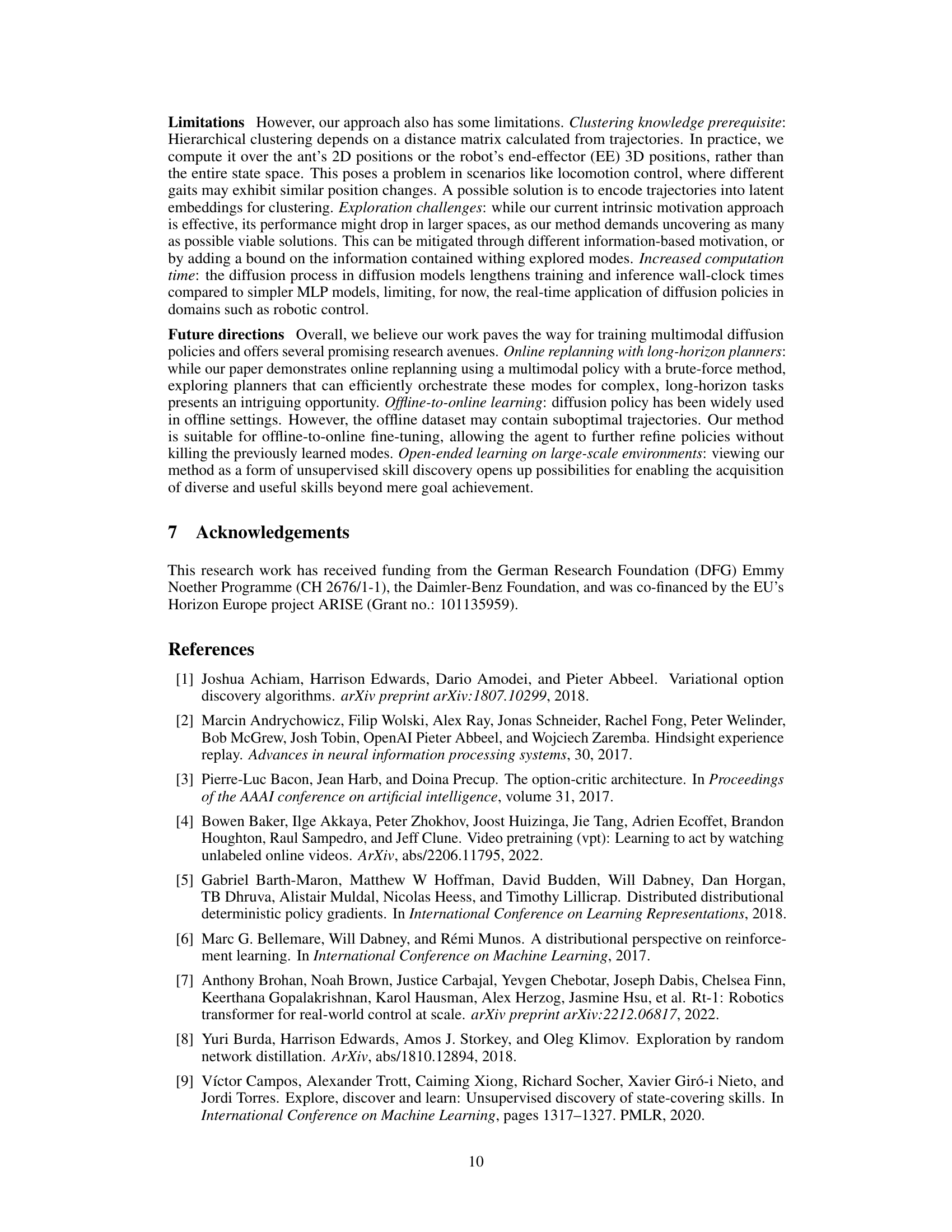

This figure shows the ablation study on the key hyperparameters of the DDiffPG algorithm. Each subfigure shows the effect of varying a single hyperparameter while keeping others constant. (a) Batch size: impact on cumulative reward. (b) Number of diffusion steps: impact on cumulative reward. (c) UTD ratio (updates-to-data): impact on cumulative reward. (d) Action gradient learning rate: impact on cumulative reward. The shaded area represents the standard deviation across multiple runs.

This figure shows eight different tasks used to evaluate the proposed method in the paper. The top row displays four AntMaze environments, each presenting a maze with varying complexities and multiple potential solution paths for an ant agent to reach a goal. The bottom row depicts four robotic manipulation tasks: Reach (reaching a target object), Peg-in-hole (inserting a peg into a hole), Drawer-close (closing a drawer), and Cabinet-open (opening a cabinet). These tasks all share a characteristic of having multiple ways to successfully complete them, thus demanding multimodal behavior from the learning agent. The variety in task types (navigation and manipulation) and the complexity within each task create a rigorous benchmark for evaluating multimodal policy learning algorithms.

This figure shows eight different tasks used to evaluate the proposed multimodal Deep Diffusion Policy Gradient (DDiffPG) algorithm. The top row displays four AntMaze environments with varying levels of complexity, each requiring the agent to navigate a maze to reach a goal. The bottom row shows four robotic manipulation tasks: Reach (reaching a target object), Peg-in-hole (inserting a peg into a hole), Drawer-close (closing a drawer), and Cabinet-open (opening a cabinet). These tasks are designed to be multimodal, meaning there are multiple ways to successfully complete each task, which tests the algorithm’s ability to learn and utilize diverse strategies.

This figure shows eight different tasks used to evaluate the proposed multimodal policy learning algorithm, DDiffPG. The top row presents four variations of the AntMaze environment, each with a different maze layout designed to encourage the discovery of multiple solution paths. The bottom row depicts four robotic manipulation tasks: Reach (reaching a target), Peg-in-hole (inserting a peg into a hole), Drawer-close (closing a drawer), and Cabinet-open (opening a cabinet). All these tasks are characterized by high multimodality, meaning there are multiple ways to successfully complete each task.

This figure shows eight different tasks used to evaluate the performance of the proposed multimodal reinforcement learning algorithm. The top row displays four variations of the AntMaze environment, each with a different layout and level of complexity. The bottom row illustrates four robotic manipulation tasks: Reach, Peg-in-hole, Drawer-close, and Cabinet-open. These tasks are designed to be multimodal, meaning that there are multiple ways to successfully complete them. This multimodality makes them suitable for testing the algorithm’s ability to learn and utilize diverse strategies.

This figure shows eight different tasks used to evaluate the proposed multimodal policy learning algorithm. The top row displays four AntMaze environments with varying maze layouts, while the bottom row shows four robotic manipulation tasks: reaching for an object, inserting a peg into a hole, closing a drawer, and opening a cabinet. These tasks were chosen because they each present multiple ways to solve them, providing a challenging test bed for a multimodal learning algorithm. Each task’s high degree of multimodality makes them particularly useful for evaluating the ability of an agent to learn and utilize a variety of strategies for a given task. The multimodal nature of the tasks is key to demonstrating the strength of the proposed method in contrast to traditional RL methods that typically learn single-mode policies.

This figure shows eight different tasks used to evaluate the performance of the proposed multimodal reinforcement learning algorithm. The top row displays four AntMaze environments, each with a unique maze structure and varying difficulty. The bottom row illustrates four robotic manipulation tasks: Reach (reaching a target), Peg-in-hole (inserting a peg), Drawer-close (closing a drawer), and Cabinet-open (opening a cabinet). These tasks were specifically chosen due to their high degree of multimodality; meaning that each task can be solved through multiple distinct strategies or paths.

This figure showcases the eight different tasks used in the paper to evaluate the proposed multimodal policy learning algorithm. The top row shows four variations of the AntMaze environment, which involves navigating a maze with an ant-like robot. Each version presents unique challenges in terms of path complexity and obstacle placement. The bottom row displays four robotic manipulation tasks: Reach (reaching for a target), Peg-in-hole (inserting a peg into a hole), Drawer-close (closing a drawer), and Cabinet-open (opening a cabinet). These tasks were specifically designed to demonstrate the capability of the algorithm to learn diverse strategies for achieving the same goal. They all offer a high degree of multimodality, meaning that there are multiple ways to successfully complete each task.

This figure shows eight different tasks used to evaluate the performance of the proposed multimodal reinforcement learning algorithm. The top row displays four variations of the AntMaze environment, each presenting a different level of complexity in terms of path finding and obstacle avoidance. The bottom row illustrates four robotic manipulation tasks: Reach (reaching a target point), Peg-in-hole (inserting a peg into a hole), Drawer-close (closing a drawer), and Cabinet-open (opening a cabinet). All eight tasks are designed to have multiple solutions, making them ideal for testing the algorithm’s ability to learn and utilize diverse strategies.

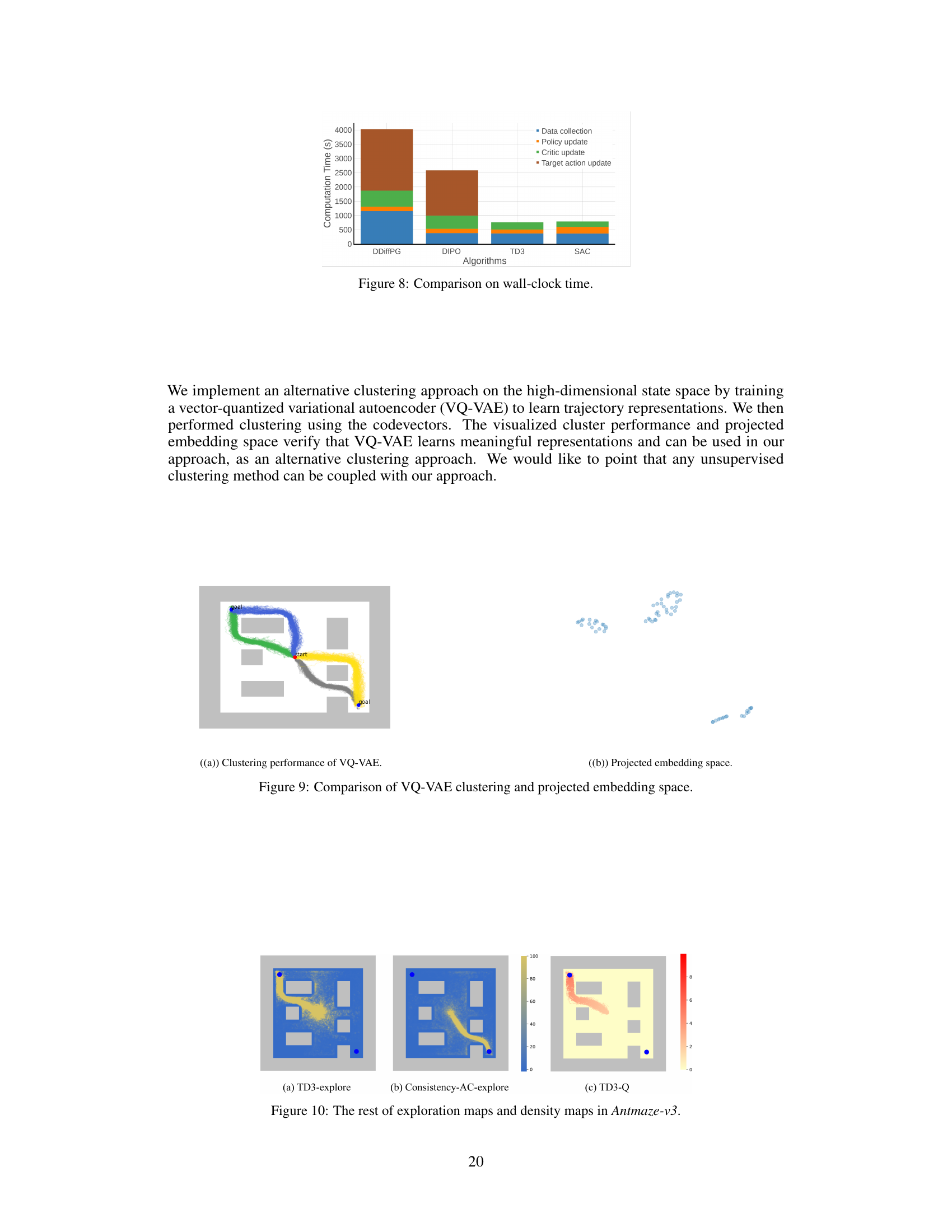

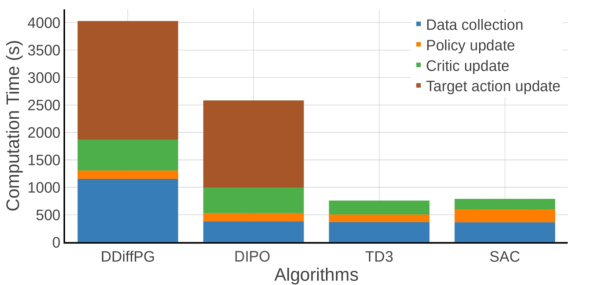

This figure compares the computation time of DDiffPG and other baseline algorithms (DIPO, TD3, SAC) across four key stages of the algorithm: data collection, policy update, critic update, and target action update. It shows that DDiffPG requires significantly more time for data collection compared to the baselines, while the policy update time is comparable. Notably, DDiffPG has a higher critic update time due to the use of multiple Q-functions, and it also requires more time for target action updates because of the use of multimodal batches.

This figure shows the result of using VQ-VAE for trajectory clustering. Panel (a) displays the clustering results in the AntMaze environment, with different colors representing different clusters. Panel (b) shows the projected embedding space of the trajectories, illustrating how the VQ-VAE captures the distinct modes in the data. The figure highlights the effectiveness of VQ-VAE as an alternative approach to hierarchical clustering for identifying behavioral modes.

This figure compares the exploration maps of DDiffPG and several baseline algorithms (DIPO, Diffusion-QL, SAC, and RPG) in the AntMaze-v3 environment. The maps visually represent the frequency with which the agent visits different areas of the environment during the learning process. A darker color indicates more frequent visits, suggesting a preference for certain paths or strategies. The visual comparison aims to highlight the exploration capabilities of different algorithms and demonstrate whether they tend to focus on a specific region or explore the entire environment more uniformly. DDiffPG is expected to show more diverse exploration due to its multimodal nature.

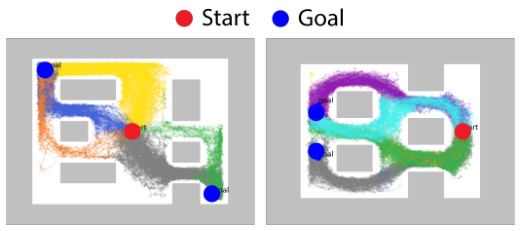

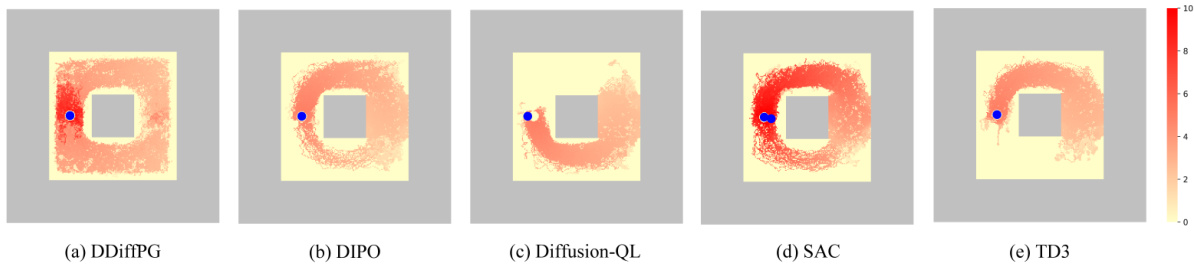

This figure compares the exploration maps of DDiffPG with four baseline algorithms (DIPO, Diffusion-QL, SAC, and TD3) in the AntMaze-v3 environment. The maps visualize the frequency with which the agent visits different areas of the maze during exploration. DDiffPG demonstrates broader exploration compared to other methods which tend to focus on a single, potentially optimal path, highlighting DDiffPG’s ability to discover multiple behavioral modes.

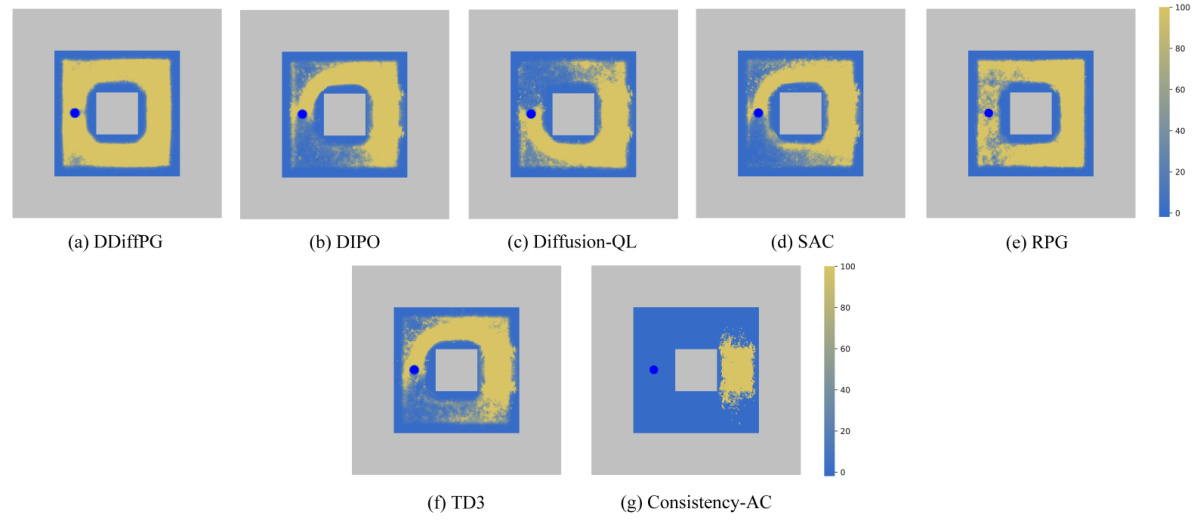

This figure shows the exploration maps for AntMaze-v3 environment, comparing DDiffPG with several baseline algorithms including DIPO, Diffusion-QL, SAC, RPG, TD3, and Consistency-AC. Each subfigure visualizes the density of visits to different states within the environment for each algorithm. DDiffPG demonstrates a wider and more thorough exploration compared to most baselines, suggesting its superior ability to avoid local minima and discover various solutions to the navigation problem.

This figure compares the exploration patterns of DDiffPG against four other reinforcement learning algorithms (DIPO, Diffusion-QL, SAC, and TD3) in the AntMaze-v3 environment. Each subfigure shows a heatmap representing the density of visits to different states (grid cells) in the maze during training. The heatmaps visualize how extensively the algorithms explore various paths and areas within the maze during learning. Differences in exploration patterns indicate the algorithms’ exploration strategies and their effectiveness in covering the state space.

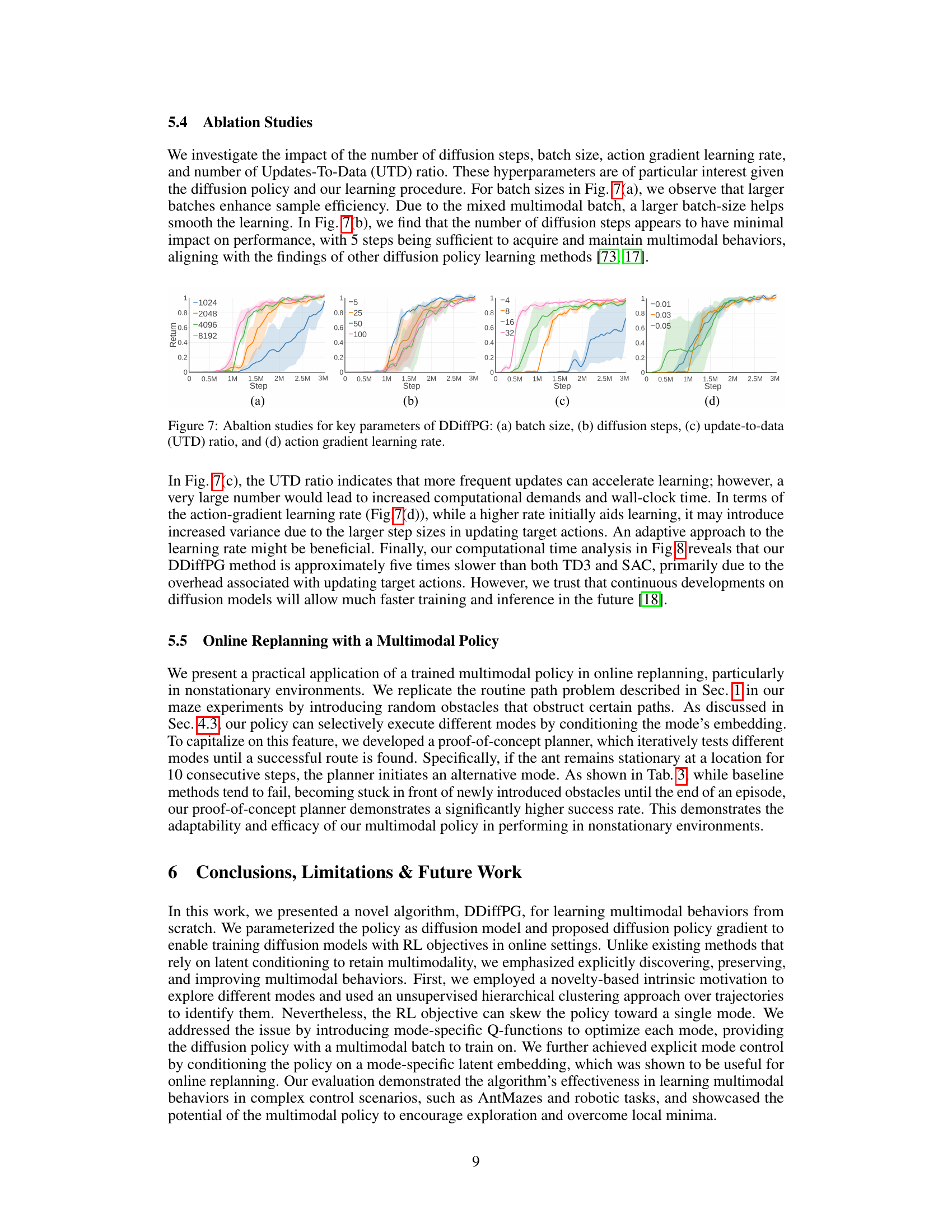

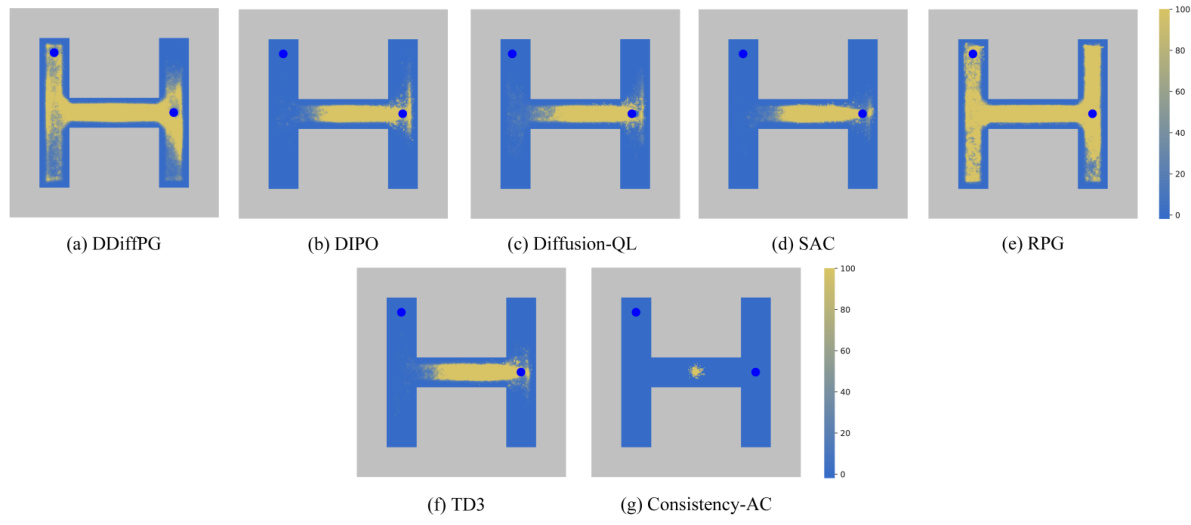

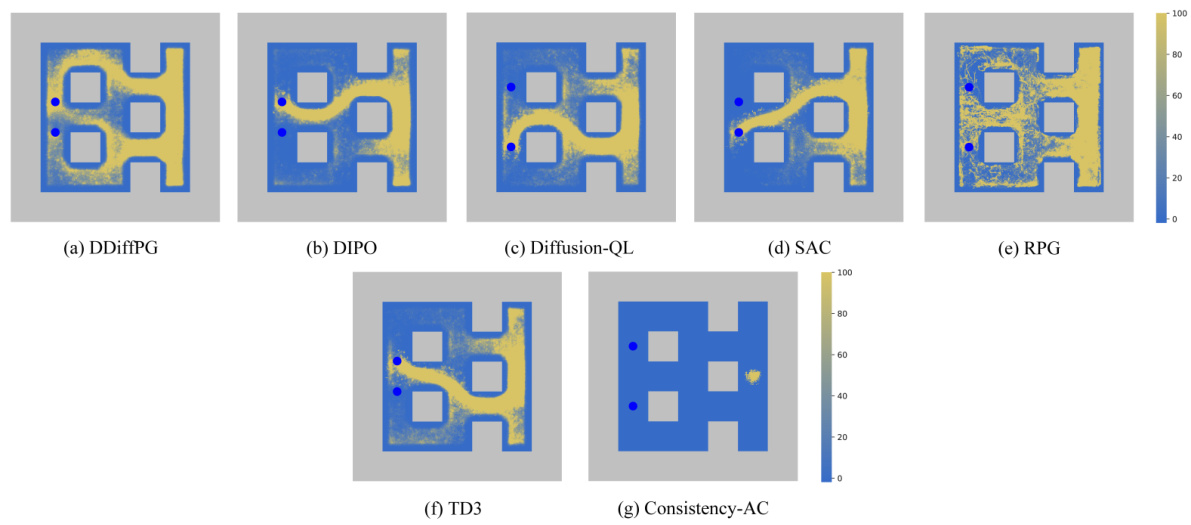

This figure displays heatmaps visualizing Q-values for different baselines and the proposed DDiffPG method within the AntMaze-v2 environment. Each subfigure represents a different algorithm (DDiffPG, DIPO, Diffusion-QL, SAC, TD3, Consistency-AC, and RPG) and shows the Q-values across the state space, providing a visual representation of how each algorithm evaluates different states in terms of expected future rewards. Warmer colors (yellow/red) indicate higher Q-values, suggesting more promising states, while cooler colors (blue) indicate lower Q-values.

The figure shows exploration maps of five different reinforcement learning algorithms on the AntMaze-v3 environment. The algorithms are DDiffPG, DIPO, Diffusion-QL, SAC, and TD3. Each map visualizes the density of visits to each cell in the maze during exploration. DDiffPG explores multiple paths more effectively, demonstrating its superior exploration capability compared to the other baselines. This highlights DDiffPG’s ability to discover multiple solutions for solving the same task in a complex environment.

This figure compares the exploration patterns of different reinforcement learning algorithms in the AntMaze-v3 environment. The maps visually represent the density of visits to different cells in the maze during exploration. DDiffPG is shown to explore multiple paths to reach the goals, indicating multimodal behavior. In contrast, other baselines tend to focus on a single path, demonstrating a lack of multimodality.

This figure shows the learning curves for DDiffPG and several baseline reinforcement learning algorithms across four AntMaze environments and four robotic manipulation tasks. The y-axis represents the average return (reward) achieved by the agents, and the x-axis represents the number of training steps. The plot visualizes the performance of each algorithm over time, allowing for a comparison of their learning efficiency and final performance on these challenging control tasks. Each line represents a different algorithm, and shaded regions indicate standard error across multiple runs. This provides a quantitative evaluation of DDiffPG’s ability to learn multimodal behaviors compared to established RL methods.

More on tables

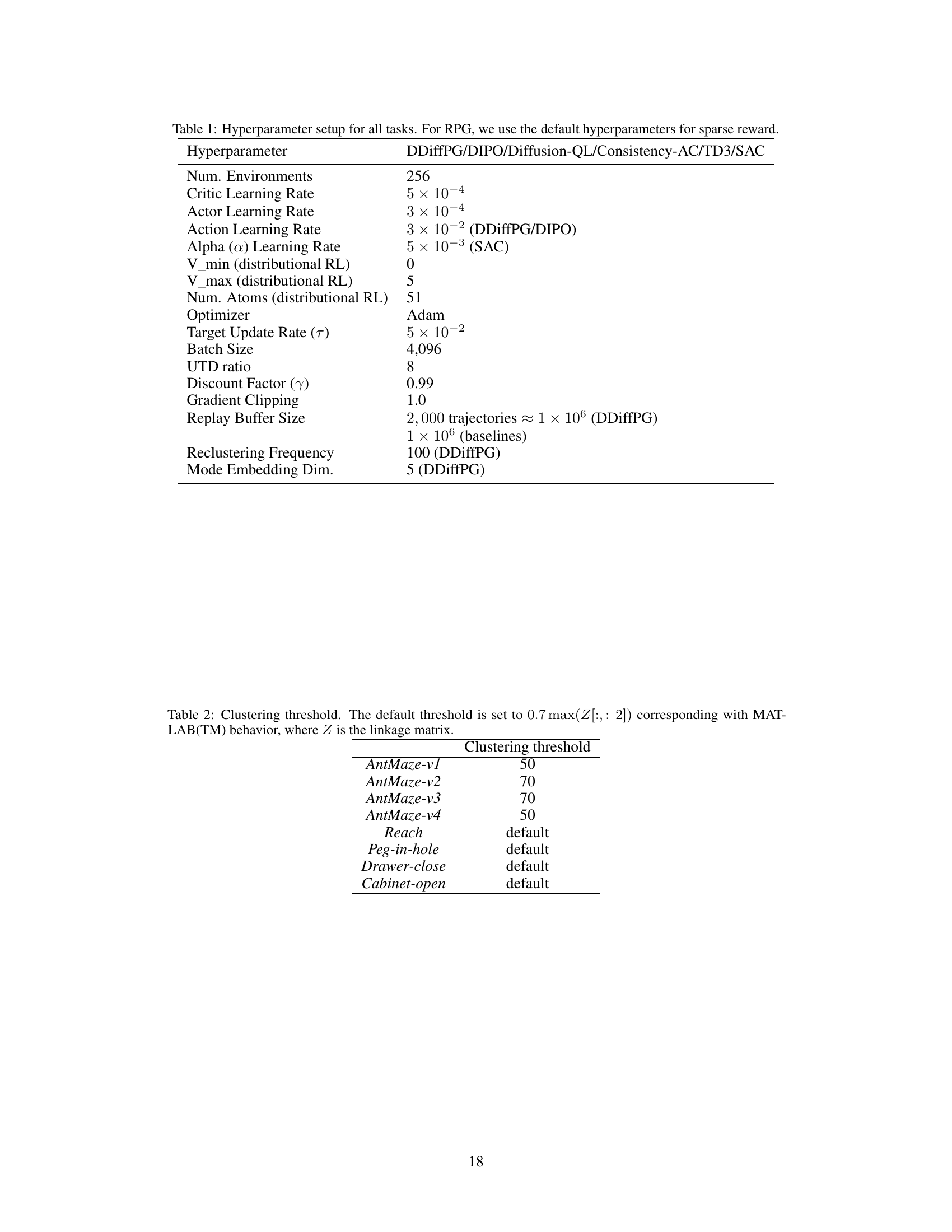

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the performance of DDiffPG against several baselines across four AntMaze environments and a randomized AntMaze environment with obstacles. The metrics include the number of distinct behavioral modes learned, the success rate (percentage of episodes successfully completed), and the average episode length. This data demonstrates the multimodal capabilities of DDiffPG and how it compares to single-mode approaches in terms of exploration, solution diversity, and efficiency.

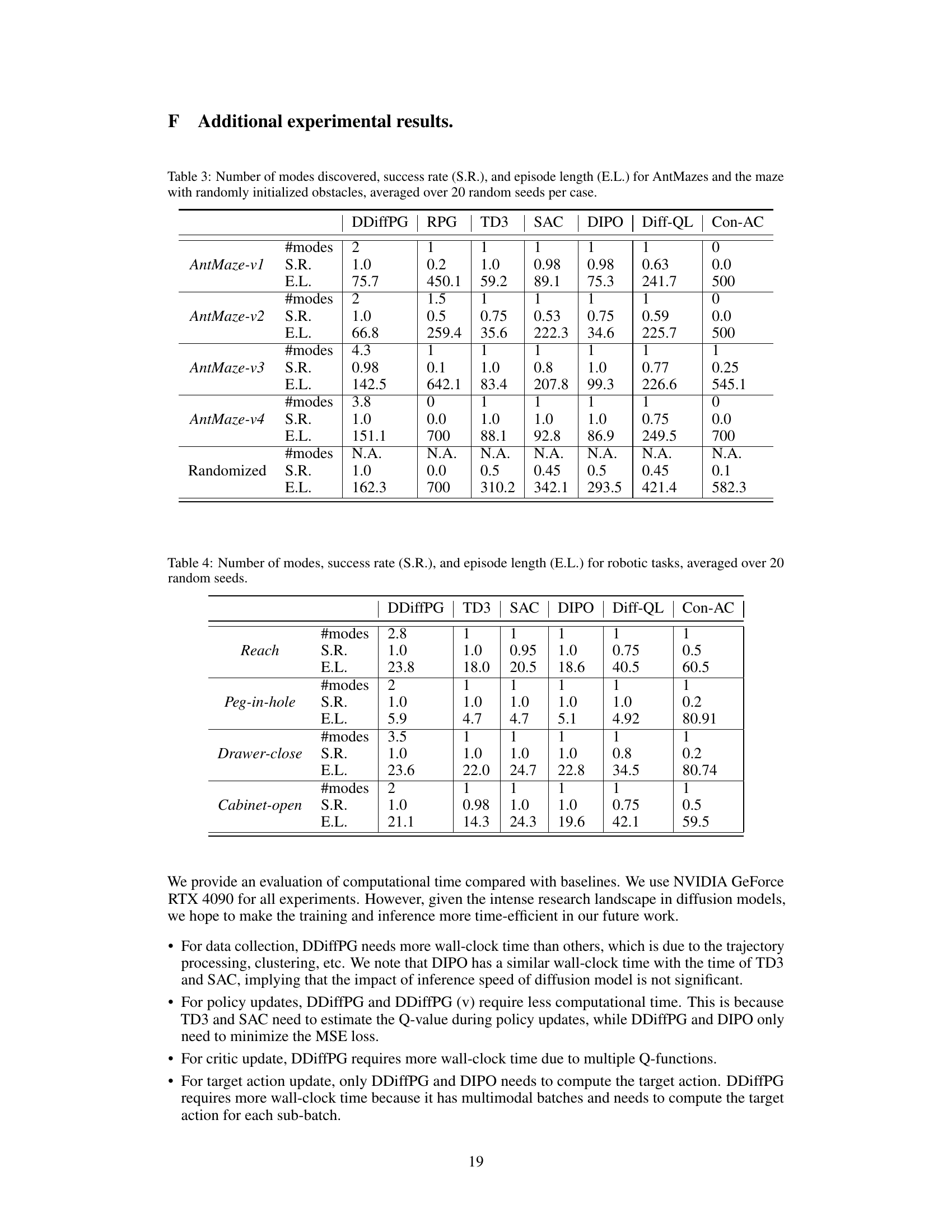

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on four robotic manipulation tasks: Reach, Peg-in-hole, Drawer-close, and Cabinet-open. For each task, it shows the number of distinct behavioral modes learned by DDiffPG and several baseline algorithms (TD3, SAC, DIPO, Diffusion-QL, Con-AC). The success rate (S.R.) indicates the percentage of successful task completions, and the episode length (E.L.) represents the average number of steps taken to complete the task. The data is averaged over 20 trials with different random seeds to provide a statistical measure of the algorithm’s performance.

Full paper#