↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current research primarily focuses on local robustness evaluations, aggregating results from individual data points. This approach is insufficient as it doesn’t represent the true global robustness, especially when dealing with unknown data distributions. Furthermore, attack-dependent methods can be computationally expensive.

This paper proposes GREAT Score, a novel framework that leverages generative models to efficiently estimate global robustness. GREAT Score offers a certified lower bound on the minimal adversarial perturbation, addresses scalability challenges with large models, and enables remote auditing of black-box models, demonstrating its utility in privacy-sensitive contexts. The paper validates GREAT Score through extensive experiments, showing high correlation with attack-based model rankings while significantly reducing computational costs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in adversarial robustness because it introduces a novel, efficient method for evaluating global robustness. It addresses the limitations of existing local-based approaches and opens up new avenues for auditing black-box models, particularly in privacy-sensitive domains like facial recognition. Its computational efficiency and theoretical guarantees make it highly impactful for large-scale evaluations.

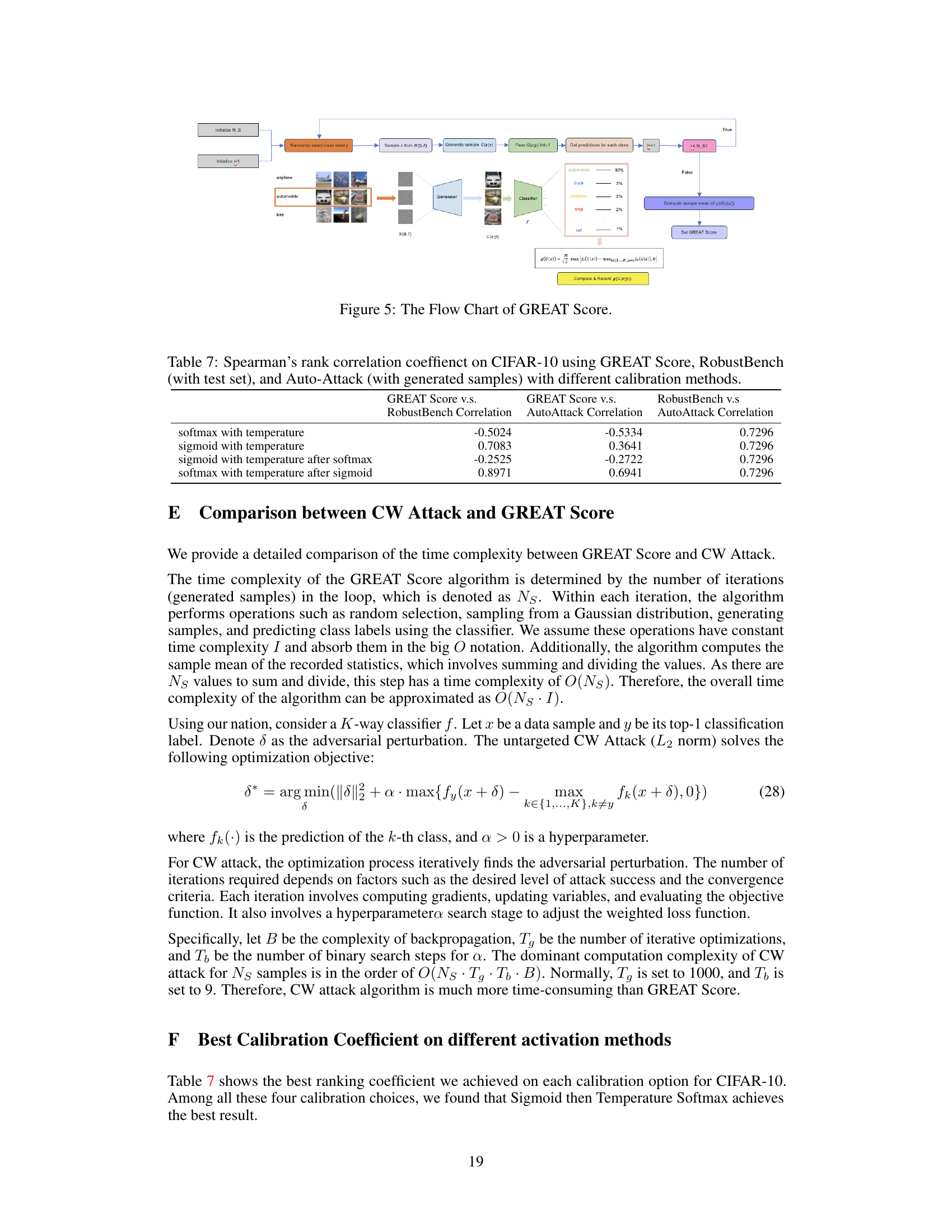

Visual Insights#

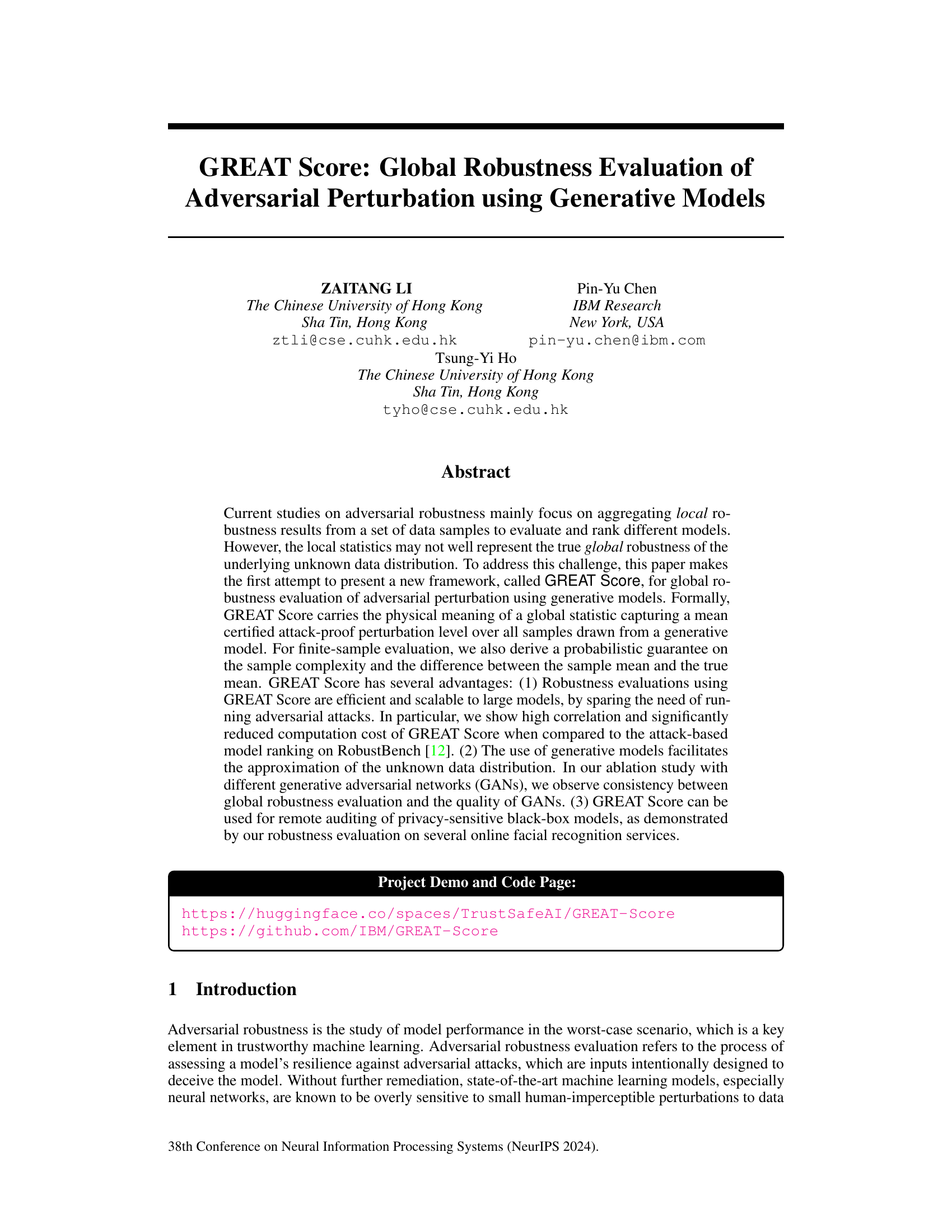

The figure shows a comparison of cumulative robust accuracy (RA) between GREAT Score and Auto-Attack under varying L2 perturbation levels. Both methods were tested on 500 samples. GREAT Score provides a certified lower bound on RA, meaning it guarantees that at a given perturbation level, the model’s accuracy will be at least that value. Conversely, Auto-Attack gives an empirical (measured) RA under the same conditions. The difference highlights that the GREAT Score provides a guaranteed level of robustness while the Auto-Attack reflects the actual performance against a specific attack strategy.

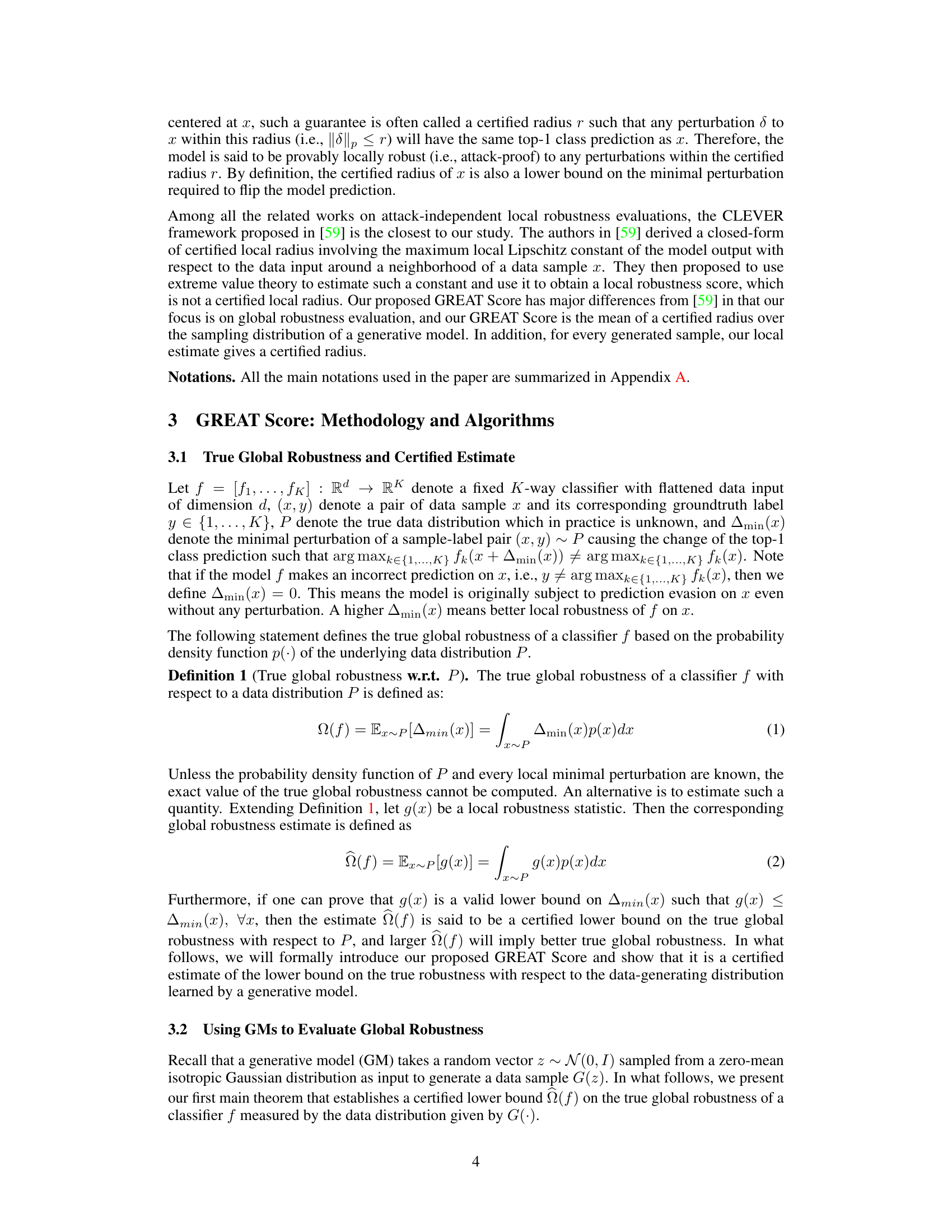

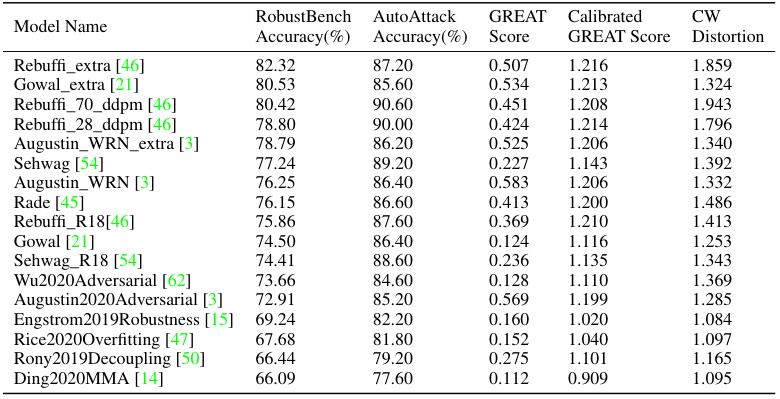

This table compares the performance of GREAT Score and the minimal distortion found by the Carlini-Wagner (CW) attack on the CIFAR-10 dataset. For each of the seventeen models listed, it shows the RobustBench accuracy, AutoAttack accuracy, the uncalibrated GREAT Score, the calibrated GREAT Score, and the average minimal distortion from the CW attack. The results are averaged across 500 samples generated using StyleGAN2. The table demonstrates how well GREAT Score aligns with the CW attack’s findings and its capability to provide calibrated, attack-proof robustness evaluations.

In-depth insights#

Global Robustness Metric#

A global robustness metric aims to quantify a model’s resilience against adversarial attacks across its entire input distribution, not just on a limited test set. Unlike local metrics that focus on individual data points, a global metric provides a holistic view of robustness. This is crucial because local robustness can be misleading; a model might perform well on some samples but poorly on others, reflecting an uneven robustness landscape. A well-designed global metric should be statistically sound, computationally efficient, and readily interpretable. This might involve leveraging generative models to sample from the underlying data distribution, allowing for a more comprehensive assessment than traditional methods. Ideally, a good global metric facilitates fair model comparison and helps researchers better understand and improve the robustness of machine learning models in real-world scenarios where the input data is diverse and unpredictable. The key challenge lies in finding a balance between accuracy, efficiency, and capturing the true nature of global robustness. This requires careful consideration of statistical properties and computational constraints.

Generative Model Use#

The utilization of generative models in the research paper presents a novel approach to evaluating the global robustness of machine learning models. Instead of relying solely on limited test datasets, which may not fully represent the true data distribution, the authors leverage generative models to synthesize a vast number of data samples. This strategy allows for a more comprehensive and accurate assessment of model robustness, especially crucial in scenarios where the true data distribution remains unknown. The use of generative models provides a statistically sound means to obtain a global robustness metric, enabling a reliable comparison of different models or even remote auditing of sensitive systems. The choice of generative model itself and the quality of the generated samples impact the accuracy of the assessment, making it vital to consider this factor and validate the generation process. The paper’s innovative application of generative models establishes a significant contribution to the field of adversarial robustness evaluation, moving beyond local statistics to obtain a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of model resilience against malicious attacks. The efficiency and scalability of this approach enhance the feasibility of large-scale assessments.

GAN-Based Evaluation#

A GAN-based evaluation approach for assessing the robustness of machine learning models against adversarial attacks offers a compelling alternative to traditional methods. Leveraging generative adversarial networks (GANs) allows for the creation of synthetic datasets that closely mimic the real-world data distribution, mitigating issues of bias and instability inherent in using limited real-world samples. By generating a wide array of diverse examples, a GAN-based system can provide a more comprehensive and reliable measure of model robustness than methods that rely solely on a fixed test set. The core strength lies in its potential to identify global vulnerabilities, not just localized weaknesses, offering a more holistic assessment of model resilience under attack. This is particularly beneficial for evaluating complex models and large datasets where running conventional attack-based evaluations might prove prohibitively expensive and computationally demanding. However, challenges remain concerning the quality of the GAN itself. The effectiveness of the evaluation hinges heavily on the GAN’s ability to accurately reflect the underlying data distribution. If the GAN produces low-quality or unrealistic samples, the robustness assessment will be compromised. Future research is needed to explore robust metrics for assessing GAN quality and to develop techniques for refining GAN-based evaluations.

Certified Robustness#

Certified robustness in machine learning focuses on providing provable guarantees about a model’s resilience against adversarial attacks. Unlike empirical evaluations that rely on testing against a set of attacks, certified robustness methods aim to mathematically prove a model’s resistance to a class of perturbations. This often involves formal verification techniques, such as analyzing the model’s decision boundaries or using abstract interpretation. A key challenge is the computational cost associated with certification, which can be high for complex models and large datasets. Approximation methods, like randomized smoothing, offer a trade-off between computational efficiency and the level of certified robustness achieved. However, the approximation comes at the price of possible underestimation of the model’s true resilience. Further research focuses on developing more efficient and scalable certification techniques, expanding the range of attacks considered, and creating more practical methods for diverse model architectures and data distributions.

Future Work#

Future work could explore extending GREAT Score’s applicability beyond L2-norm perturbations, investigating its performance with other norms (L1, L∞) and different attack models. A key area for improvement is exploring the impact of generative model choice and quality on the accuracy and robustness of GREAT Score, performing a more extensive comparison of various GANs and diffusion models to determine best practices. Furthermore, it would be valuable to investigate ways to calibrate GREAT Score for specific model architectures and datasets. Research could also address the theoretical limitations surrounding the accuracy of the sample mean estimate for finite datasets, developing more sophisticated estimation techniques with stronger guarantees or exploring alternative metrics that better capture the true global robustness. Finally, applying GREAT Score to a wider range of tasks and datasets, including those with high dimensionality or more complex data distributions, would provide further evidence of its generalizability and effectiveness.

More visual insights#

More on figures

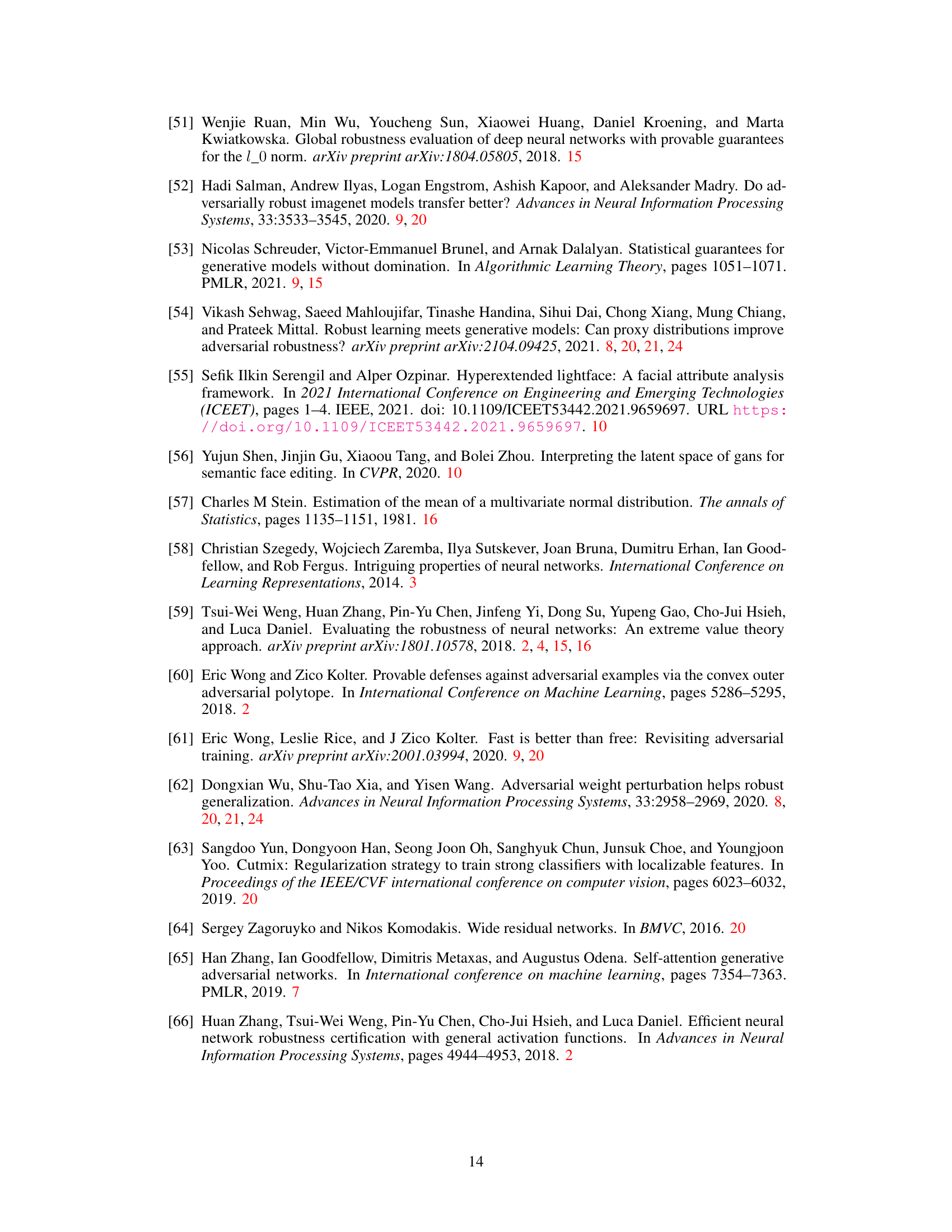

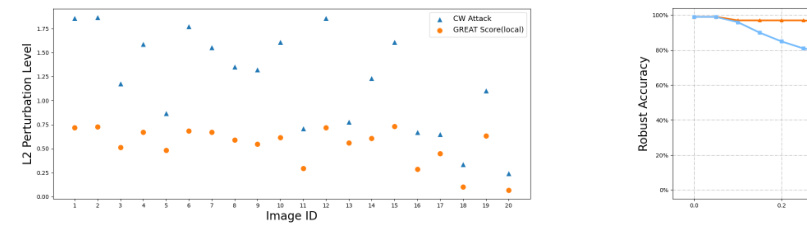

This figure compares the local GREAT Score and the L2 perturbation level found by the CW attack on 20 randomly selected images from the CIFAR-10 dataset using the Rebuffi_extra model. The x-axis represents the image ID, and the y-axis represents the L2 perturbation level. Each point shows the perturbation level for a single image. The blue triangles represent the perturbation level found by the CW attack (a strong adversarial attack method), and the orange circles represent the local GREAT Score (a certified lower bound on the minimal adversarial perturbation). The figure visually demonstrates that the local GREAT Score consistently provides a lower bound for the perturbation level found by the CW attack, validating its theoretical properties.

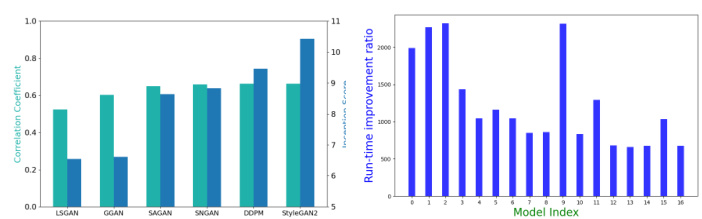

This figure shows the results of an ablation study comparing different generative models used in the GREAT Score framework. The left y-axis shows the Inception Score (IS), a metric evaluating the quality of generated images by GANs. The right y-axis displays the Spearman’s rank correlation between GREAT Score and RobustBench, assessing the consistency of model rankings. Higher IS values generally correlate with higher rank correlation, suggesting that better generative models lead to more reliable global robustness estimates. This demonstrates that the quality of the generative model influences GREAT score performance.

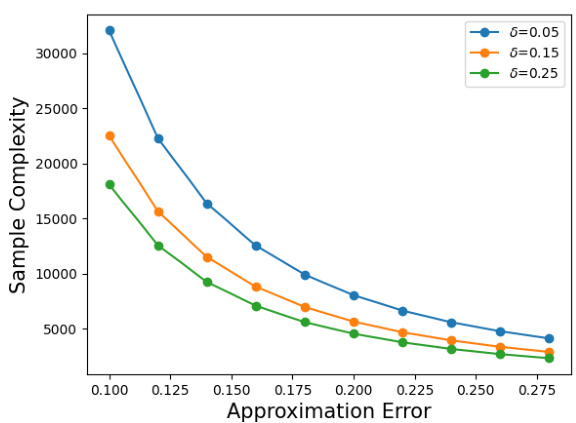

This figure shows the relationship between the approximation error (epsilon) and the sample complexity required to achieve a certain level of confidence (delta) in the estimation of the global robustness metric, GREAT Score. The sample complexity refers to the number of samples needed from the generative model to obtain a reliable estimate. As expected, smaller errors (epsilon) or higher confidence levels (delta) necessitate a larger sample size (sample complexity). The figure showcases three different confidence levels (delta = 0.05, 0.15, and 0.25), each with its corresponding relationship between the approximation error and sample complexity.

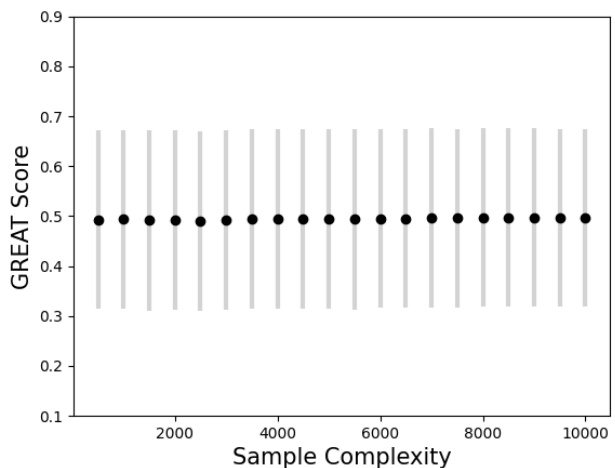

This figure shows the relationship between the GREAT Score and the number of samples used in the evaluation. The x-axis represents the sample complexity, ranging from 500 to 10000. The y-axis represents the GREAT Score. Each data point shows the average GREAT Score obtained across multiple runs with the given sample size, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. The figure demonstrates the stability of the GREAT Score even with a relatively small number of samples.

This figure shows the relationship between the GREAT Score and the number of samples used for its calculation. It uses the CIFAR-10 dataset and the Rebuffi_extra model. The x-axis represents the number of samples (sample complexity), ranging from 500 to 10000. The y-axis shows the GREAT Score. For each sample size, a mean GREAT Score and standard deviation are calculated and plotted. The error bars represent the standard deviation, showing the variability of the GREAT Score across different sample sets of the same size.

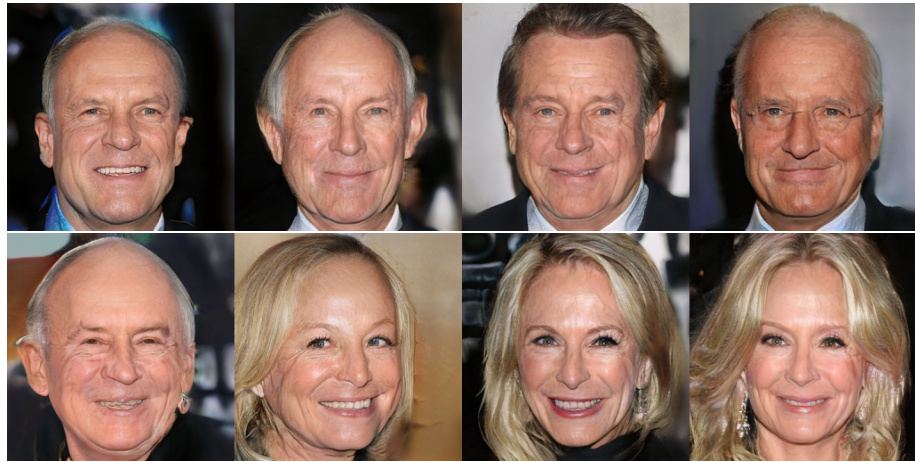

This figure shows a sample of generated images from the InterFaceGAN model, specifically focusing on the ‘old’ subgroup. The images showcase the diversity of faces generated by the model while maintaining characteristics consistent with the label. This helps to visualize the quality and variety of the synthetic data used to evaluate the GREAT Score in a privacy-preserving way.

This figure shows sample images generated by a GAN for the ‘old’ subgroup in a facial recognition robustness evaluation. The images demonstrate the variety of faces produced by the GAN for this particular attribute, showcasing differences in facial features, hair, and other visual characteristics. These images are synthetically generated and used in the evaluation process to assess the robustness of online facial recognition APIs to various types of adversarial attacks.

This figure shows a sample of generated images from a GAN model. The images are all of faces with eyeglasses, demonstrating the model’s ability to control the attributes of the generated faces (in this case, the presence of eyeglasses). This is relevant to the paper because these generated images are used to evaluate the robustness of facial recognition APIs against adversarial attacks.

This figure shows a sample of generated images from the InterFaceGAN model, specifically those categorized as belonging to the ‘old’ subgroup. The images showcase the model’s ability to generate diverse facial features and appearances consistent with the aging process, which were used for evaluating the robustness of online facial recognition APIs in a privacy-preserving way.

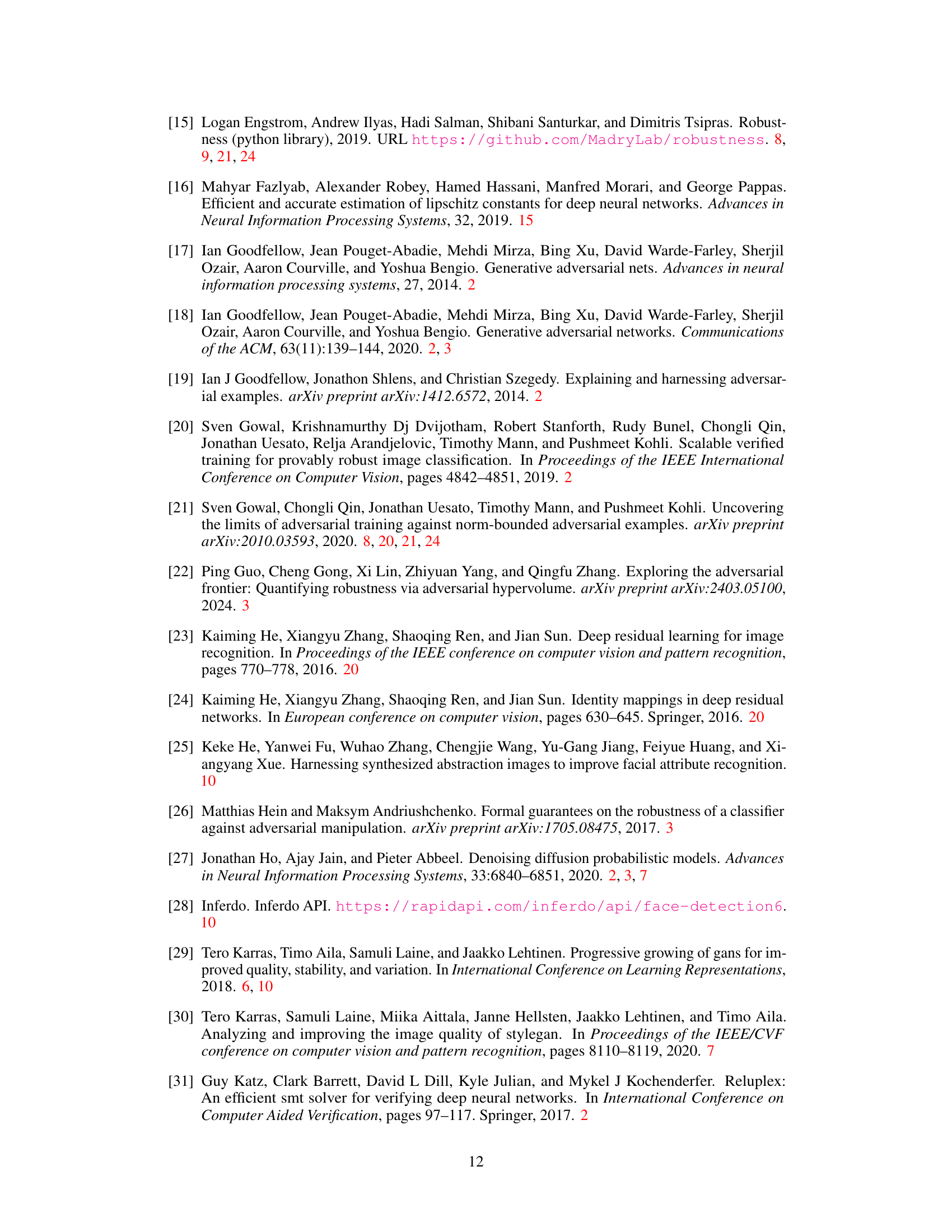

More on tables

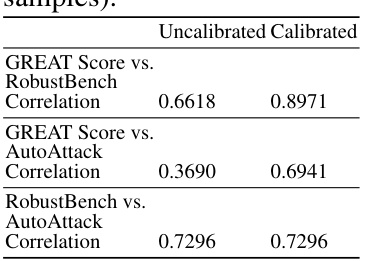

This table presents the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients between different model ranking methods on the CIFAR-10 dataset. It compares the rankings produced by GREAT Score, RobustBench (using its standard test set and AutoAttack), and Auto-Attack (using generated samples). The table shows the correlation between the rankings of these methods, both before and after calibration of the GREAT Score. High correlation indicates that the different methods agree on the relative robustness of the models. The calibration improves the correlation of GREAT Score with both RobustBench and AutoAttack.

This table presents the global robustness statistics for three different methods on the ImageNet dataset. It shows the RobustBench Accuracy (%), AutoAttack Accuracy (%), and GREAT Score for five different models. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients between GREAT Score and RobustBench, and AutoAttack and RobustBench are provided, demonstrating a strong alignment in ranking between GREAT Score and RobustBench.

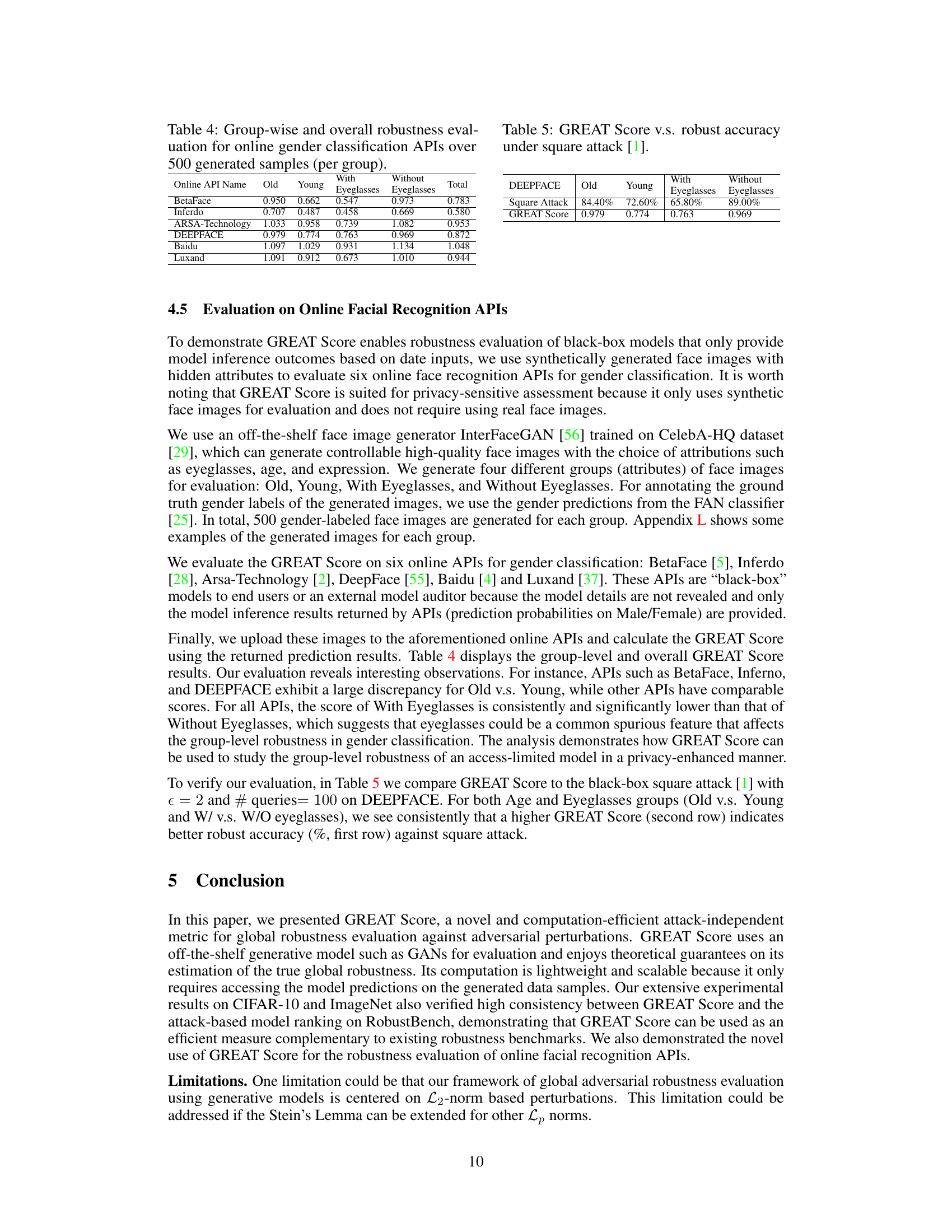

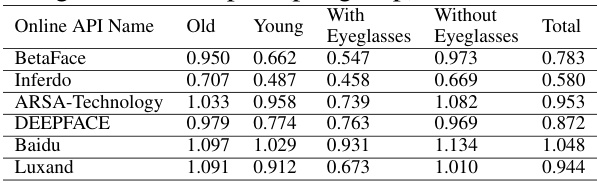

This table presents the GREAT Score results for six online gender classification APIs, evaluated using 500 synthetically generated face images for each of four groups: Old, Young, With Eyeglasses, and Without Eyeglasses. The GREAT Score, a metric for evaluating adversarial robustness, is calculated for each group and overall. The results demonstrate how GREAT Score can be used to analyze group-level robustness in access-limited systems, highlighting potential vulnerabilities or biases related to specific attributes (like age or eyeglasses).

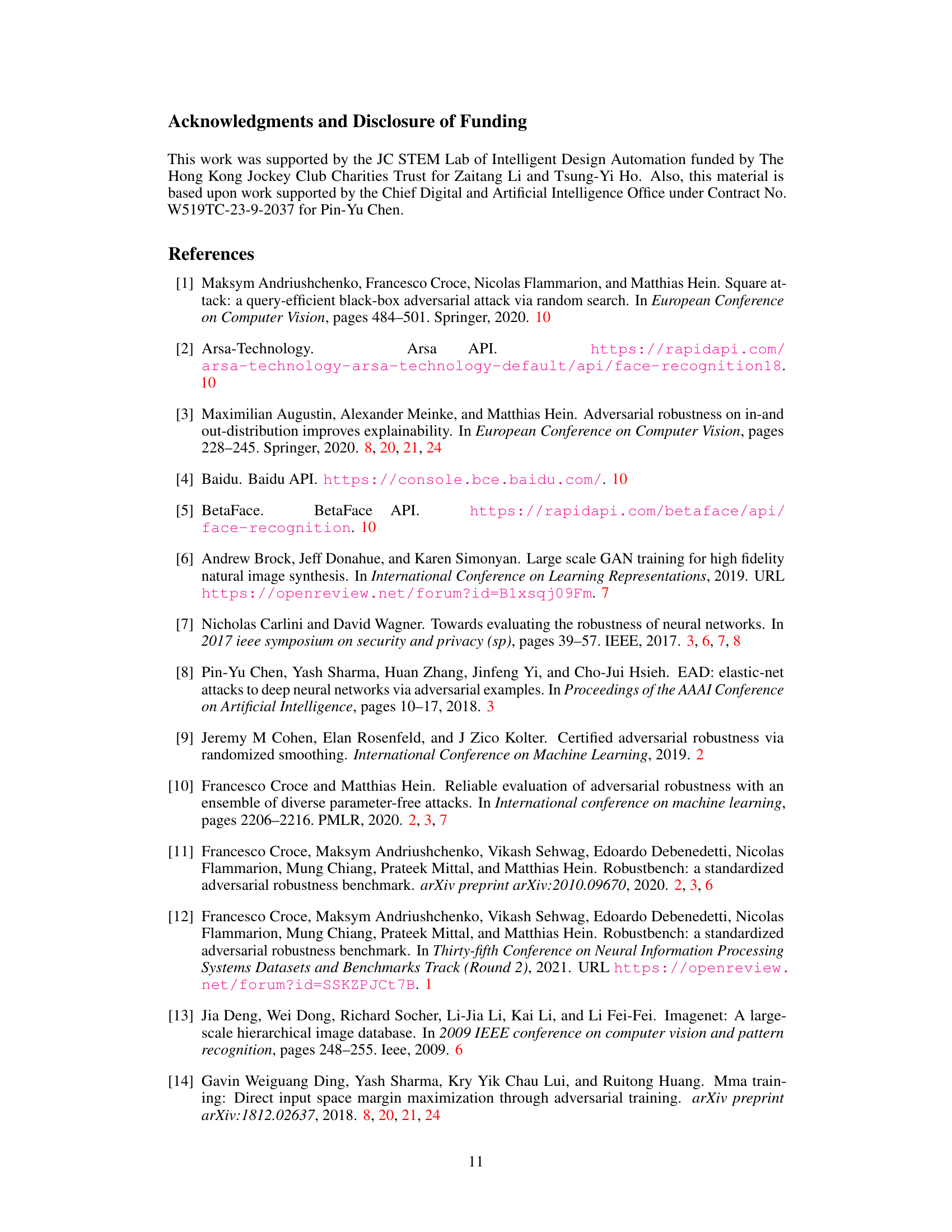

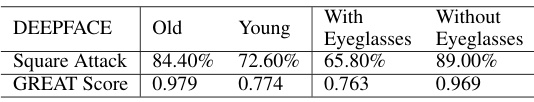

This table presents the results of a robustness evaluation performed on six online gender classification APIs. The evaluation used 500 synthetically generated face images per group, categorized by age (Old, Young) and the presence of eyeglasses (With, Without). Two metrics are reported: the success rate of a square attack (a type of adversarial attack) and the GREAT Score (a new metric for global robustness introduced in the paper). The table shows how the robustness of each API varies depending on the image characteristics (age and presence of eyeglasses).

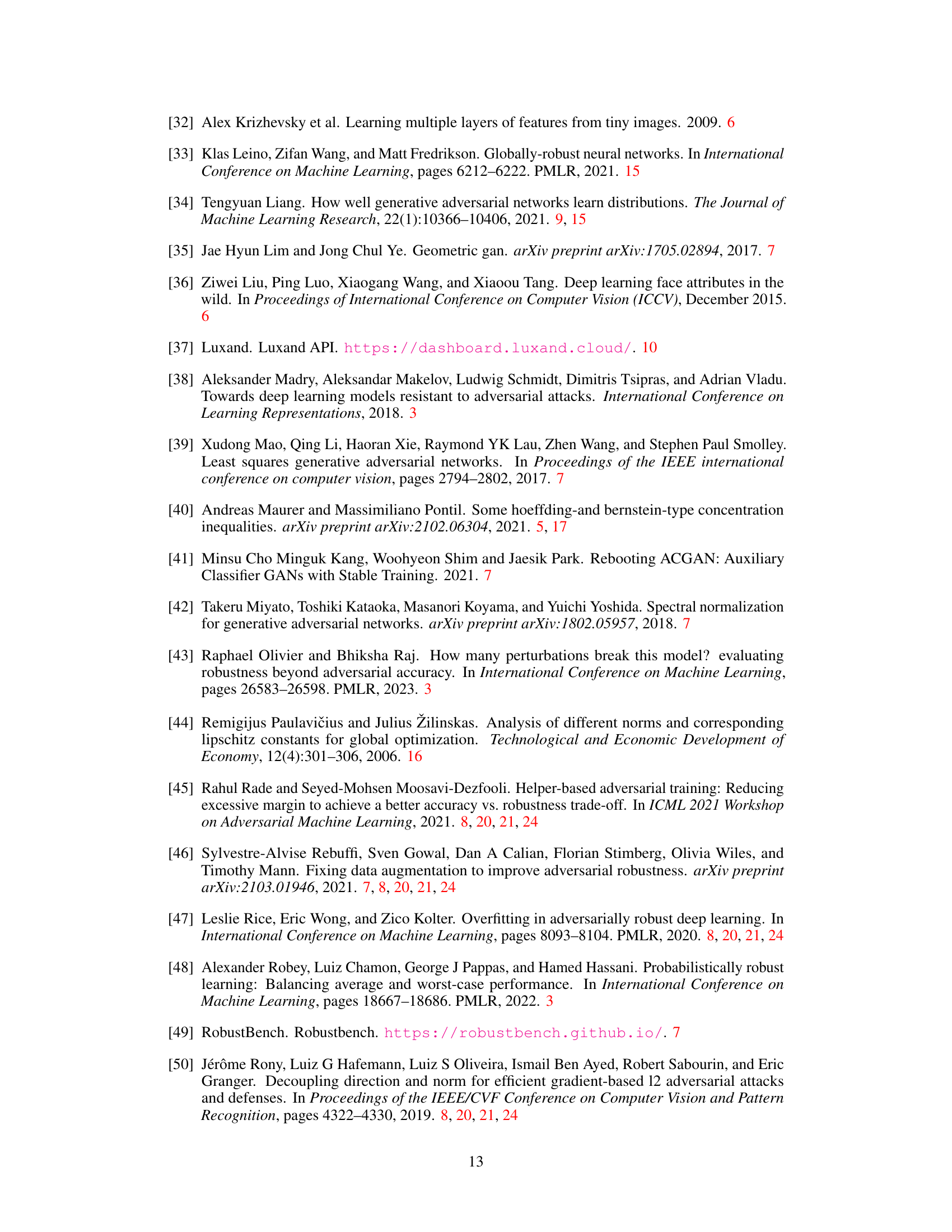

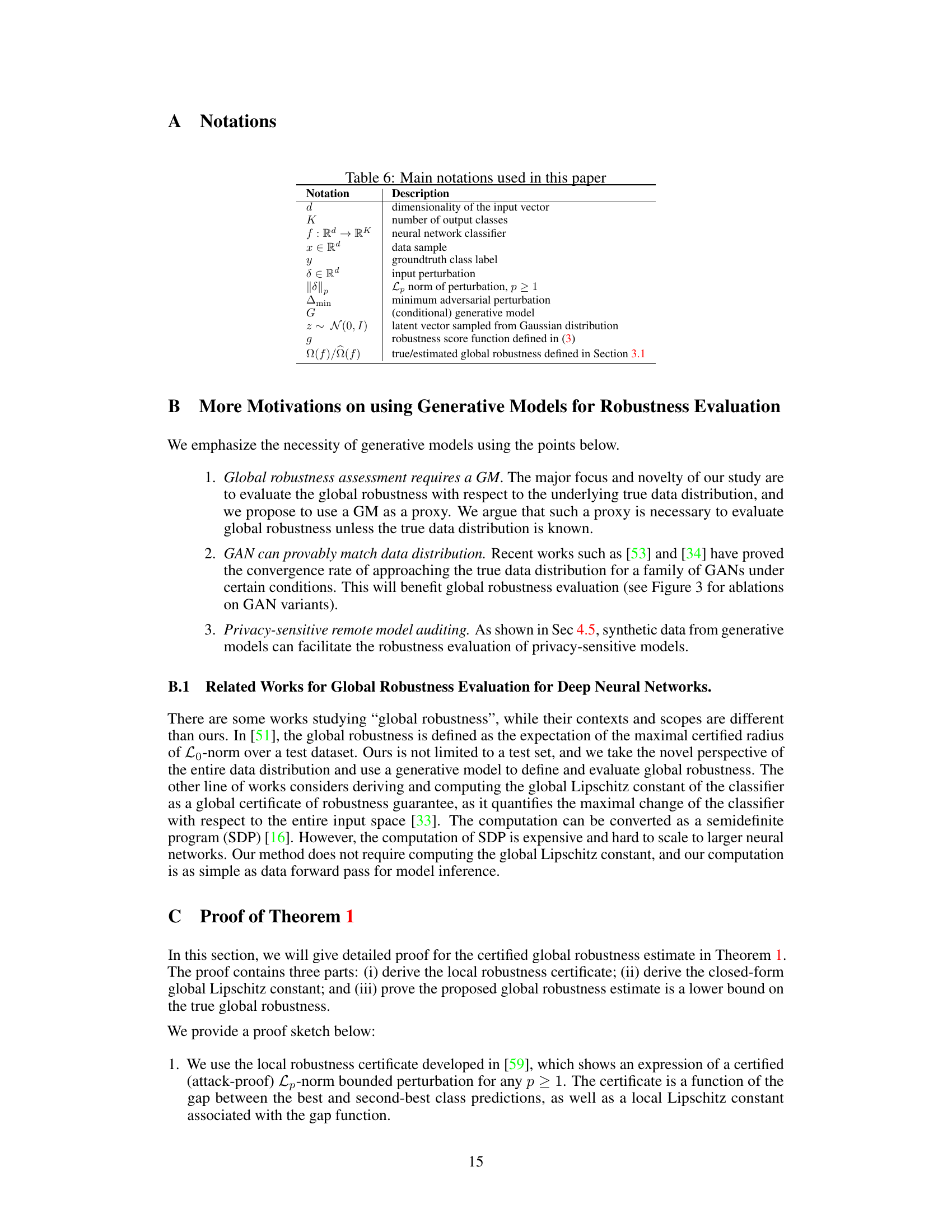

This table lists the notations used throughout the paper, providing a concise reference for readers. Each notation is paired with its description, clarifying its meaning within the context of the paper’s framework for evaluating global adversarial robustness. The descriptions cover variable types (e.g., dimensionality, classifier), data properties (e.g., sample, perturbation), and key concepts (e.g., minimum adversarial perturbation, generative model). Understanding this table is essential for interpreting the mathematical formulations and algorithms presented in the paper.

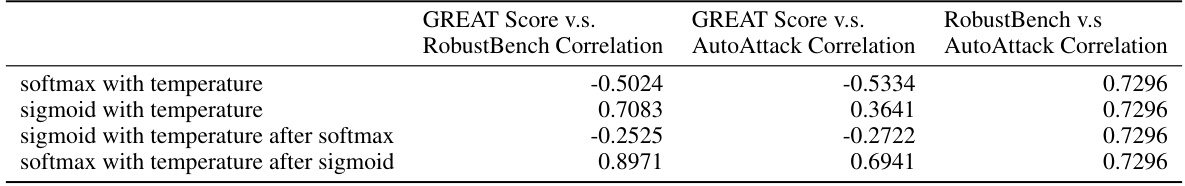

This table presents the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients obtained by comparing the model rankings from GREAT Score against RobustBench and AutoAttack on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The comparison is performed using four different calibration methods applied to the model outputs (softmax with temperature, sigmoid with temperature, sigmoid with temperature after softmax, and softmax with temperature after sigmoid). The table shows that the choice of calibration method significantly affects the consistency of model ranking between GREAT Score and the other methods.

This table presents a comparison of the per-sample computation time for GREAT Score and Auto-Attack on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The results are based on 500 generated samples and showcase a significant difference in computational efficiency between the two methods. Each row represents a different model from the RobustBench benchmark, and the columns show the average computation time required for each method per sample. The table highlights the efficiency of GREAT Score in comparison to the attack-based AutoAttack method.

This table presents a comparison of the GREAT Score, RobustBench Accuracy, and AutoAttack Accuracy for 17 different models on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The GREAT Score is a novel metric for evaluating the global robustness of a model against adversarial attacks. RobustBench Accuracy represents the accuracy of the model against the AutoAttack method, a strong adversarial attack. AutoAttack Accuracy is also assessed using AutoAttack but on generated samples. The table shows the GREAT Score values calculated using 500 original test samples and compares those scores to the RobustBench and AutoAttack accuracies, demonstrating a level of agreement between the new GREAT Score metric and existing benchmark metrics.

Full paper#