↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current visual imitation learning struggles with high-dimensional visual data, requiring numerous expert demonstrations. This is partly because visual representations are often pretrained on irrelevant data or trained solely via behavior cloning, limiting data efficiency. This inefficiency necessitates innovative solutions that leverage existing data efficiently.

DynaMo tackles this by introducing a novel, in-domain self-supervised method for learning visual representations. It jointly trains a latent inverse and forward dynamics model from image embeddings alone. Unlike previous work, DynaMo requires no augmentations or contrastive sampling and outperforms other self-supervised methods across simulated and real-world robotic environments, significantly improving downstream policy performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is highly relevant to researchers working on visual imitation learning and robotics. It offers a novel, efficient approach for learning visual representations from limited data, overcoming a critical bottleneck in the field. The findings and code release are significant for researchers wanting to improve the data efficiency of their control policies and broaden the scope of applications for imitation learning.

Visual Insights#

This figure shows the architecture of DynaMo and its application to real-world robotics. (a) illustrates the self-supervised learning process of DynaMo: It jointly learns an encoder, inverse dynamics model, and forward dynamics model to predict future frames from current observations, without using any augmentations or contrastive sampling. The learned representation is then used to train a policy. (b) demonstrates the real-world application of DynaMo: using the learned representations to train policies on two multi-task environments (xArm Kitchen and Allegro Manipulation).

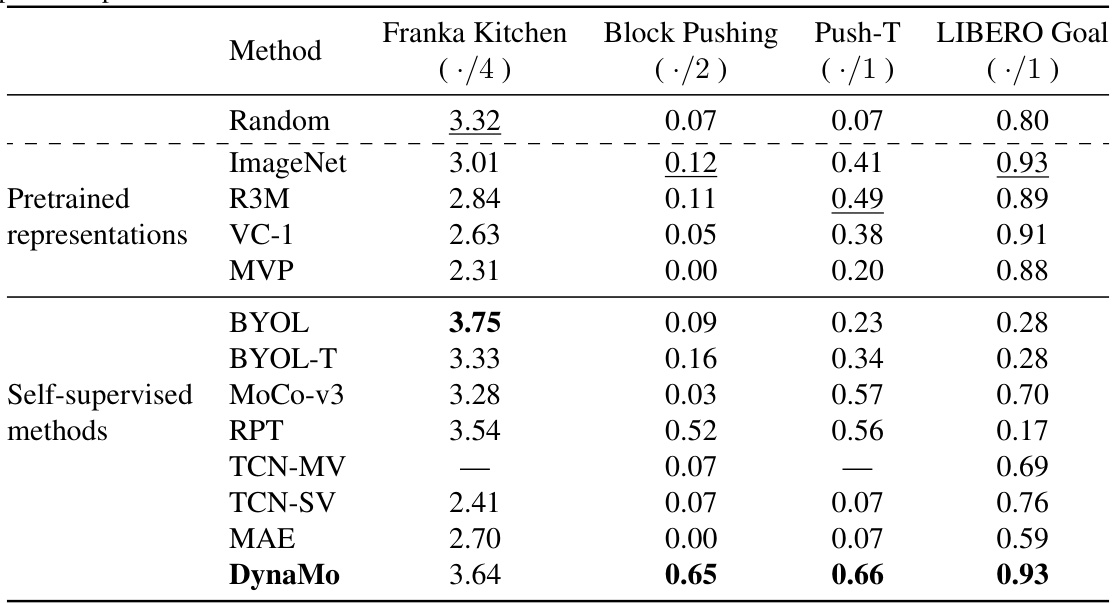

This table presents the results of downstream policy performance using different visual representations on four simulated benchmark tasks: Franka Kitchen, Block Pushing, Push-T, and LIBERO Goal. It compares DynaMo’s performance against various pretrained representations (Random, ImageNet, R3M, VC-1, MVP) and self-supervised methods (BYOL, BYOL-T, MoCo-v3, RPT, TCN-MV, TCN-SV, MAE). The results are presented as the average number of successful task completions, normalized by the maximum possible number of completions for each task. The table shows that DynaMo achieves either the highest or very competitive performance compared to the baselines across all the benchmarks.

In-depth insights#

In-Domain Dynamics#

The concept of “In-Domain Dynamics” in the context of visuomotor control focuses on learning representations directly from the limited data available within the specific task environment. This contrasts with using large, out-of-domain datasets for pretraining, which may not generalize well to downstream tasks due to differences in embodiment and viewpoint. In-domain methods leverage the inherent causal structure within demonstrations, using self-supervision to learn inverse and forward dynamics models. By jointly learning these models, the visual representations implicitly capture the task-relevant dynamics. This approach promises improved data efficiency by extracting more information from the available limited in-domain data, making it particularly suitable for real-world scenarios where obtaining extensive data can be difficult and expensive. A key advantage is that it avoids the need for augmentations, contrastive sampling, or ground truth actions, further simplifying the learning process and enhancing its practical applicability.

Self-Supervised Learning#

Self-supervised learning (SSL) is a crucial paradigm in machine learning, particularly relevant for scenarios with limited labeled data. DynaMo’s approach is innovative because it leverages the inherent causal structure within demonstrations to learn visual representations without requiring labeled actions or data augmentation. This differs significantly from conventional SSL methods like contrastive learning or masked autoencoding, which often rely on large-scale datasets or artificial data perturbations. DynaMo’s in-domain pretraining ensures that learned representations are directly relevant to the downstream visuomotor task, addressing a key limitation of out-of-domain pretraining. The effectiveness of this approach is demonstrated by DynaMo’s improved performance compared to state-of-the-art SSL and pretrained models. The joint learning of inverse and forward dynamics models is a key strength, enabling the extraction of more information from limited data, a feature not often explored in prior SSL control methods. While this method holds promise, future work could explore its scalability and robustness on significantly larger, more diverse datasets and environments.

Visual Representation#

Effective visual representation is crucial for visuomotor control, as it determines the quality of information that downstream policies receive. The choice of visual representation significantly impacts data efficiency, requiring methods to learn effectively from limited expert demonstrations. This often involves a trade-off between using pretrained models, which may not generalize well to in-domain data, and learning representations directly from limited data, which can lead to overfitting. DynaMo stands out by focusing on in-domain self-supervision, leveraging the temporal structure of the data to build a robust and task-relevant representation. It avoids contrastive learning or complex augmentations, instead relying on jointly learning forward and inverse dynamics models, ultimately enhancing performance and generalizability across various visuomotor tasks and policy classes. The core idea is that modeling dynamics inherently captures task-relevant visual features, overcoming limitations of prior approaches that focus on visually salient but less informative elements, and thus producing a more data-efficient and effective visual representation for complex robotic tasks.

Downstream Policy#

The concept of “Downstream Policy” in the context of a research paper focusing on visual representation learning for robotics likely refers to the performance evaluation of various control policies (algorithms that determine robot actions) after training them using the learned visual representations. This is crucial because the quality of learned visual features directly impacts a policy’s ability to effectively map visual observations to appropriate actions. The success of the downstream policy becomes the ultimate test for the quality of the visual representation learning method. A strong visual representation method, such as the one proposed in the research paper, should enable multiple diverse control policies to perform well on downstream tasks. The paper probably investigates the downstream performance of different policy types (e.g., behavior cloning, reinforcement learning agents) on diverse robotics tasks, evaluating their success rate and overall performance using metrics like task completion rates and the number of successful trials. A key takeaway will be the robustness and generalizability of the learned visual representation, as demonstrated by how effectively different downstream policies leverage it to accomplish various tasks.

Real-World Robotics#

Real-world robotics presents significant challenges compared to simulations. Transferring skills learned in simulation to real-world scenarios is a major hurdle, due to discrepancies in sensor noise, actuator limitations, and unanticipated environmental factors. Robustness is paramount: real-world robots must handle unexpected events and uncertainties without catastrophic failure. Data collection in real-world settings is often expensive and time-consuming, impacting the development of data-hungry algorithms. Generalization is key—a successful real-world robot must adapt to various conditions and tasks, not just those seen during training. Ethical considerations regarding safety and human-robot interaction also play a critical role, particularly in collaborative settings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

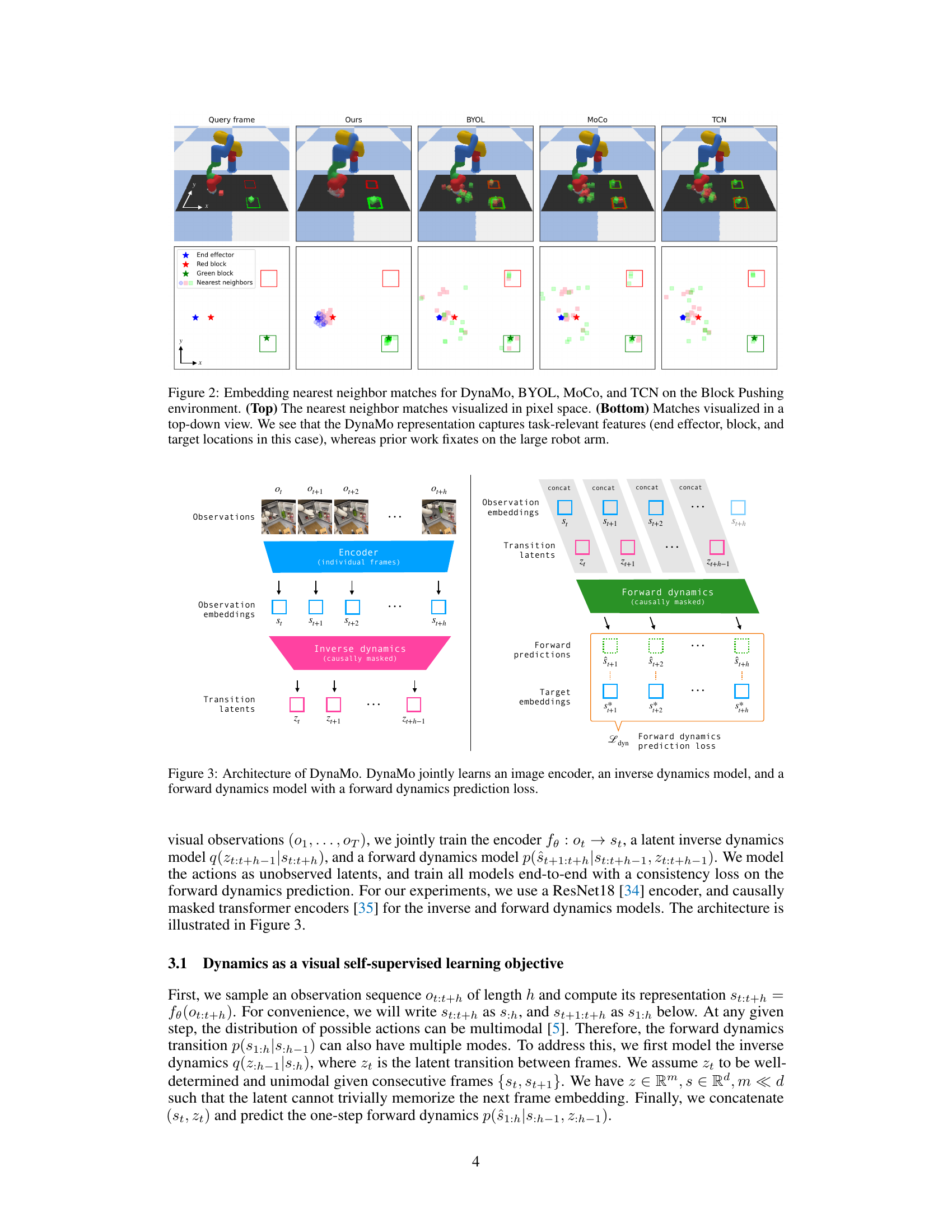

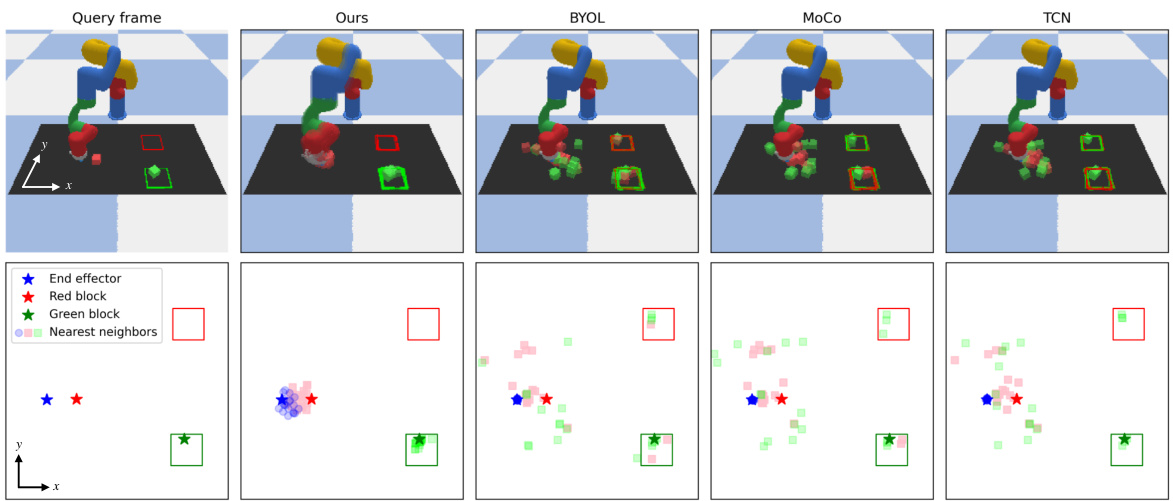

This figure compares the nearest neighbor embedding matches obtained by four different self-supervised methods (DynaMo, BYOL, MoCo, TCN) for the Block Pushing task. It shows that DynaMo’s learned representations focus on task-relevant features like the end-effector position, block positions, and target locations, while other methods primarily focus on the visually dominant robot arm, ignoring smaller, crucial features. This illustrates DynaMo’s ability to learn more task-relevant features even in the presence of visually distracting elements.

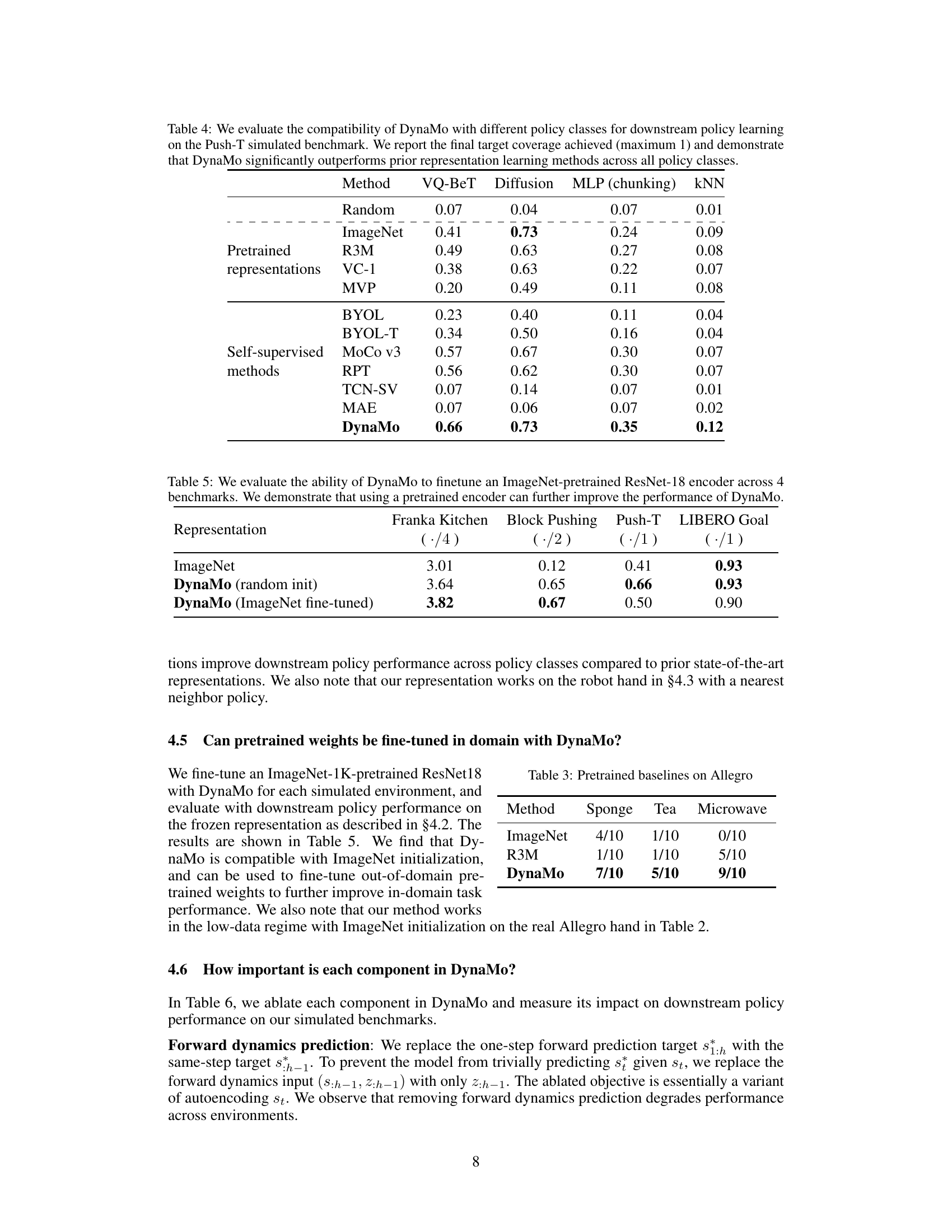

This figure illustrates the architecture of DynaMo, a self-supervised method for learning visual representations for visuomotor control. It shows three key components working together: an image encoder that converts raw visual observations into embeddings; an inverse dynamics model that predicts latent transition states given a sequence of observation embeddings; and a forward dynamics model that predicts future observation embeddings based on past embeddings and latent transitions. The forward dynamics model is trained with a prediction loss, comparing its predictions to actual future observation embeddings. This architecture allows DynaMo to learn rich representations from just image sequences without needing ground truth actions or data augmentation.

This figure shows the six different environments used to evaluate the DynaMo model. These environments range from simulated robotic manipulation tasks (Franka Kitchen, Block Pushing, Push-T, LIBERO Goal) to real-world robotic manipulation tasks (Allegro Manipulation, xArm Kitchen). The images provide a visual representation of the complexity and diversity of the tasks involved.

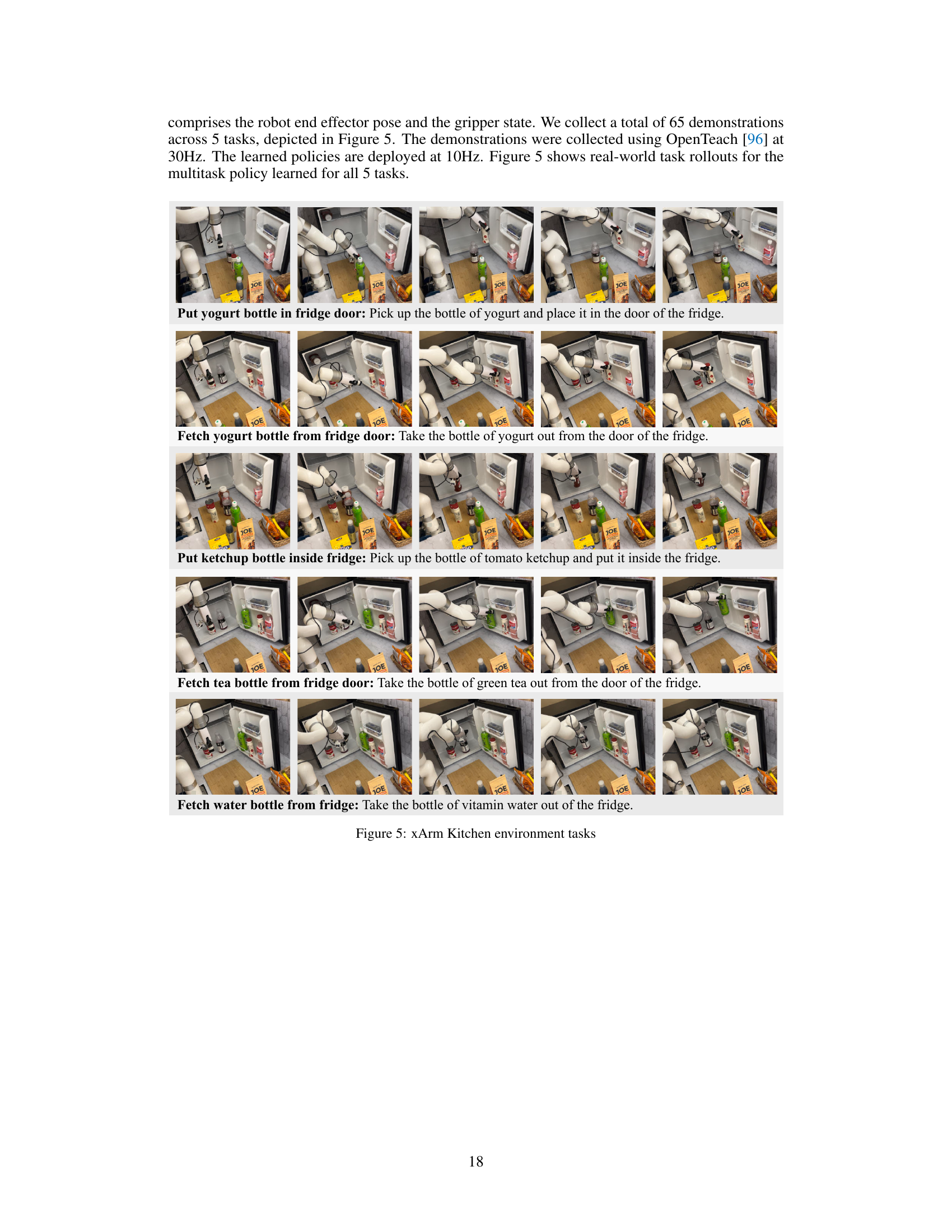

This figure shows the five different tasks in the xArm Kitchen environment. Each row displays a sequence of images showing the steps involved in completing a specific task. The tasks include putting a yogurt bottle in the fridge door, fetching a yogurt bottle from the fridge door, putting a ketchup bottle inside the fridge, fetching a tea bottle from the fridge door, and fetching a water bottle from the fridge.

This figure shows the results of applying the DynaMo model on the Allegro Manipulation environment. It showcases a series of images depicting a robotic hand performing three different tasks: lifting a sponge, lifting a teabag, and opening a microwave door. For each task, both successful and unsuccessful attempts are shown to illustrate the model’s performance variability.

This figure shows a series of images depicting the xArm robot performing various kitchen tasks, such as putting and fetching bottles from the fridge. Each row shows a sequence of images for a specific task, with some rollouts showing successful completion and others indicating failure. The success or failure of each attempt is indicated in parentheses below each task description. The overall goal is to demonstrate the capability of the DynaMo-pretrained encoder to effectively enable the robot to perform these complex manipulation tasks.

More on tables

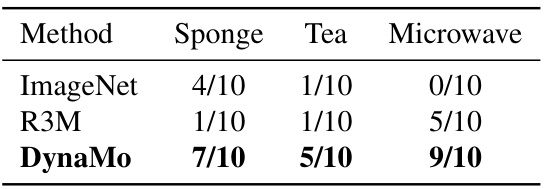

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on two real-world robotic manipulation tasks using DynaMo, BYOL, BYOL-T, and MoCo-v3. The tasks involve using robot hands to perform actions such as picking up objects or placing them in specific locations. The success rate for each task is presented as a fraction (successes/total attempts). DynaMo significantly outperforms the other methods across all tasks, demonstrating its superior performance in real-world scenarios.

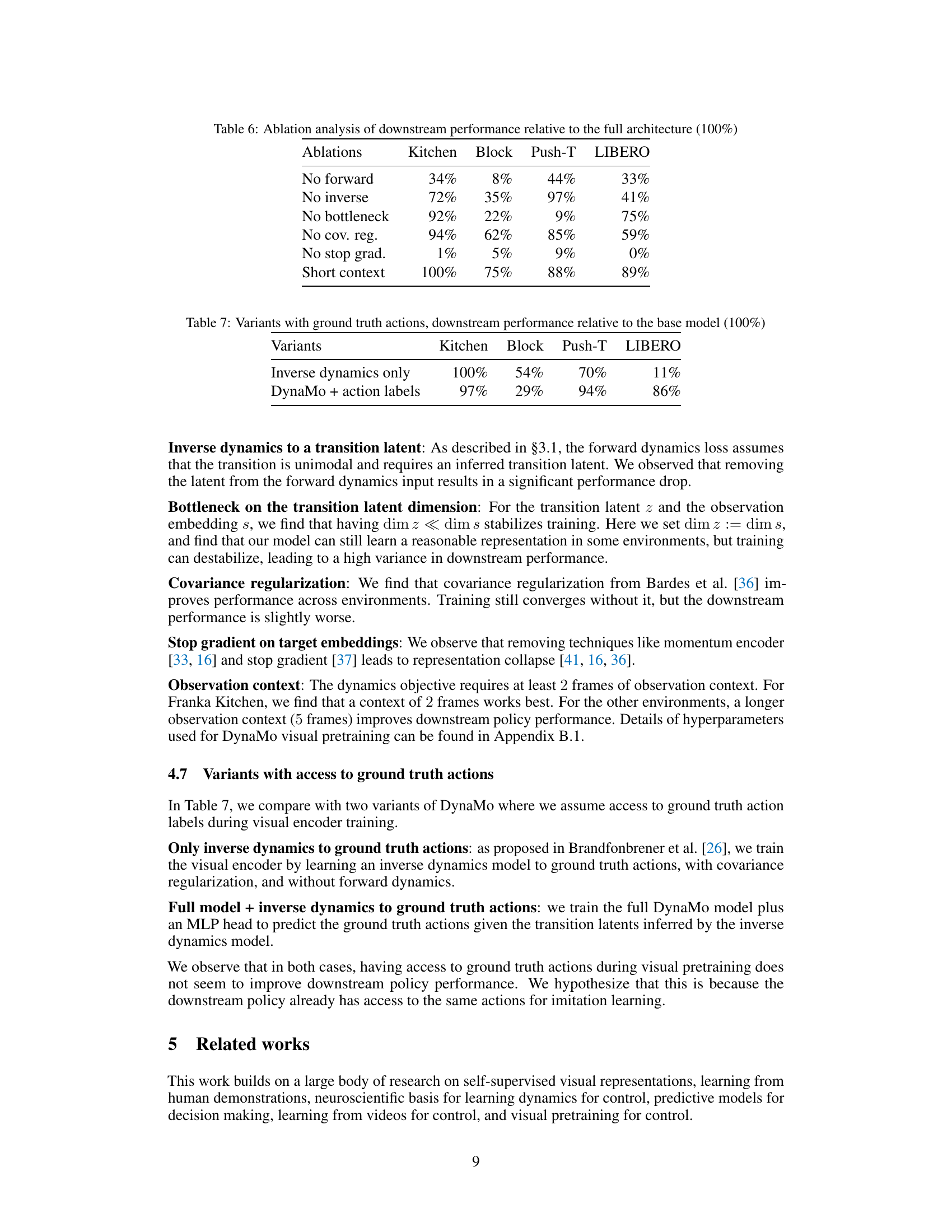

This table presents the results of downstream policy performance tests on four simulated benchmark environments using different visual representation learning methods. The methods include pretrained representations (Random, ImageNet, R3M, VC-1, MVP), self-supervised methods (BYOL, BYOL-T, MoCo v3, RPT, TCN-SV, MAE), and the proposed method, DynaMo. The performance is measured by the average success rate for each task (Franka Kitchen, Block Pushing, Push-T, and LIBERO Goal). DynaMo significantly outperforms all other methods across all four benchmarks, showcasing its effectiveness in improving downstream policy performance.

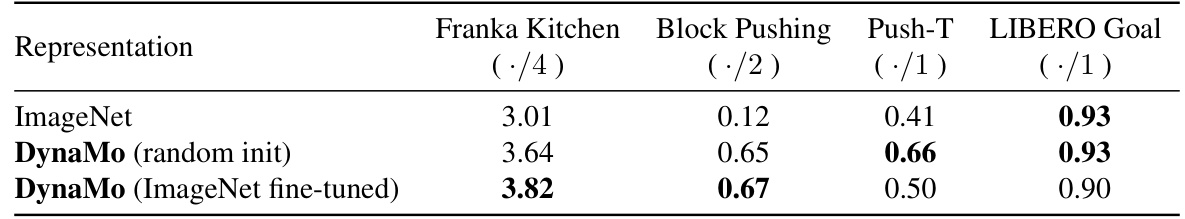

This table presents a comparison of the downstream policy performance using different visual representation methods on four simulated benchmark environments: Franka Kitchen, Block Pushing, Push-T, and LIBERO Goal. The results show the average number of tasks completed for each environment, normalized to the maximum possible value (e.g., ./4 for Franka Kitchen, where the maximum number of tasks is 4). The table compares DynaMo’s performance against various pretrained and self-supervised visual representation methods, demonstrating DynaMo’s significant improvement in downstream policy performance.

This table presents the results of applying DynaMo to eight real-world robotic manipulation tasks. Two environments are used: Allegro Manipulation (three tasks) and xArm Kitchen (five tasks). The performance of DynaMo is compared to BYOL, BYOL-T, and MoCo-v3, showing a significant improvement in success rates for DynaMo.

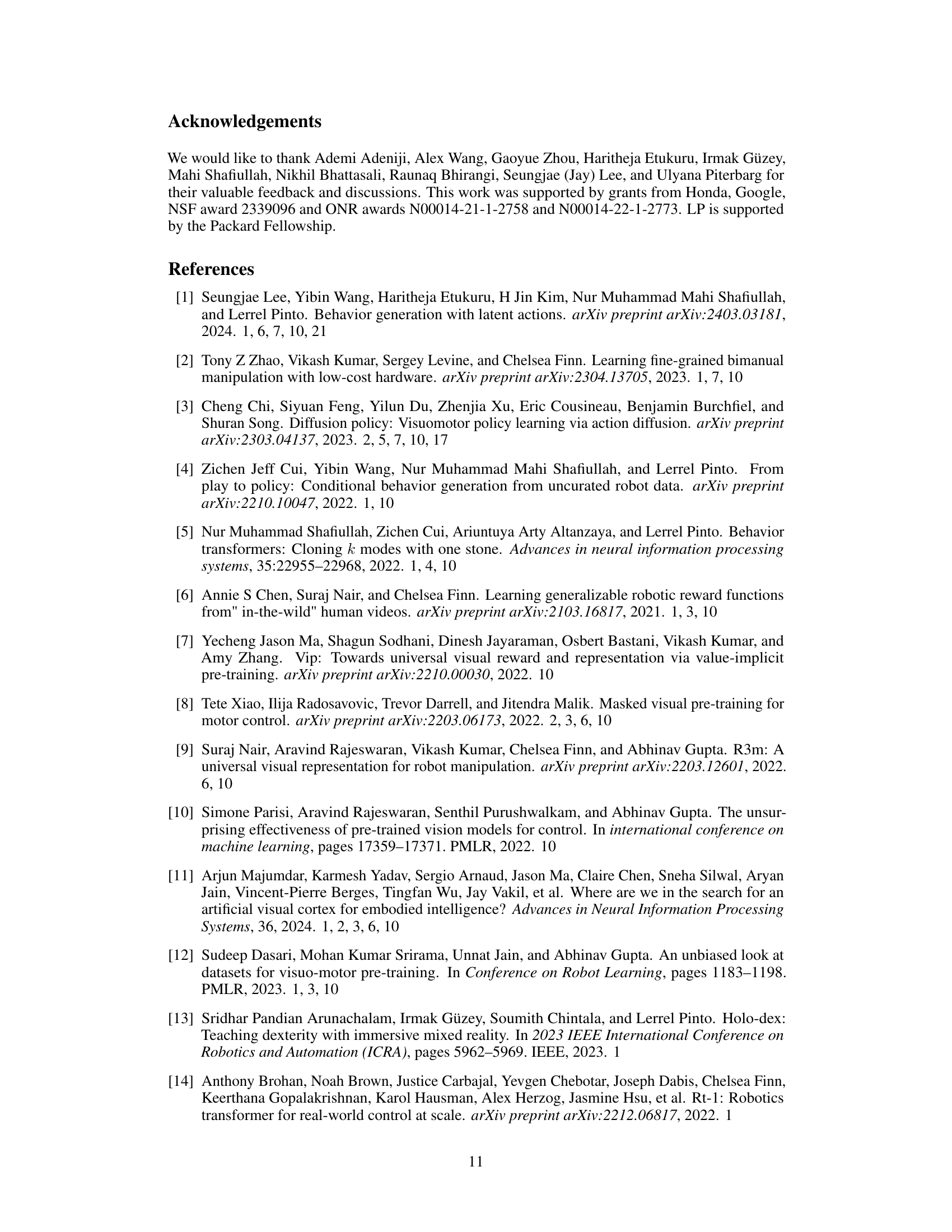

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the DynaMo model. It shows the impact of removing different components of the model (no forward, no inverse, no bottleneck, no covariance regularization, no stop gradient, short context) on the downstream policy performance across four simulated environments: Franka Kitchen, Block Pushing, Push-T, and LIBERO Goal. The performance is reported as a percentage relative to the full DynaMo model (100%). The table helps to understand the relative importance of each component in the model’s overall effectiveness.

This table presents the results of ablative studies where ground truth action labels were provided during the training of the visual encoder. Two variants are compared against the base DynaMo model: one using only inverse dynamics with ground truth actions and another including the full DynaMo model with the addition of ground truth action labels. The downstream policy performance (relative to the base DynaMo model’s performance) is shown for each variant and across four different simulated robotics environments.

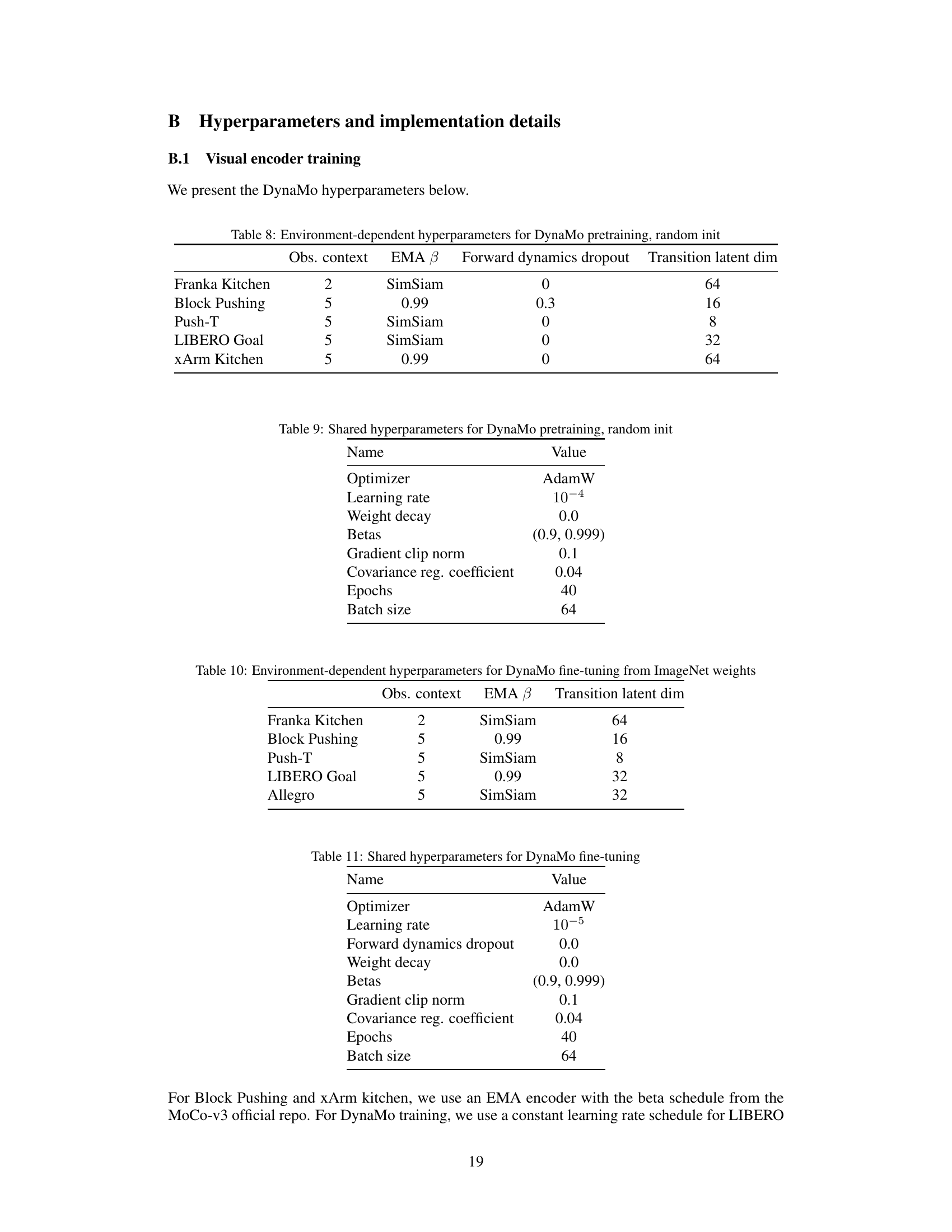

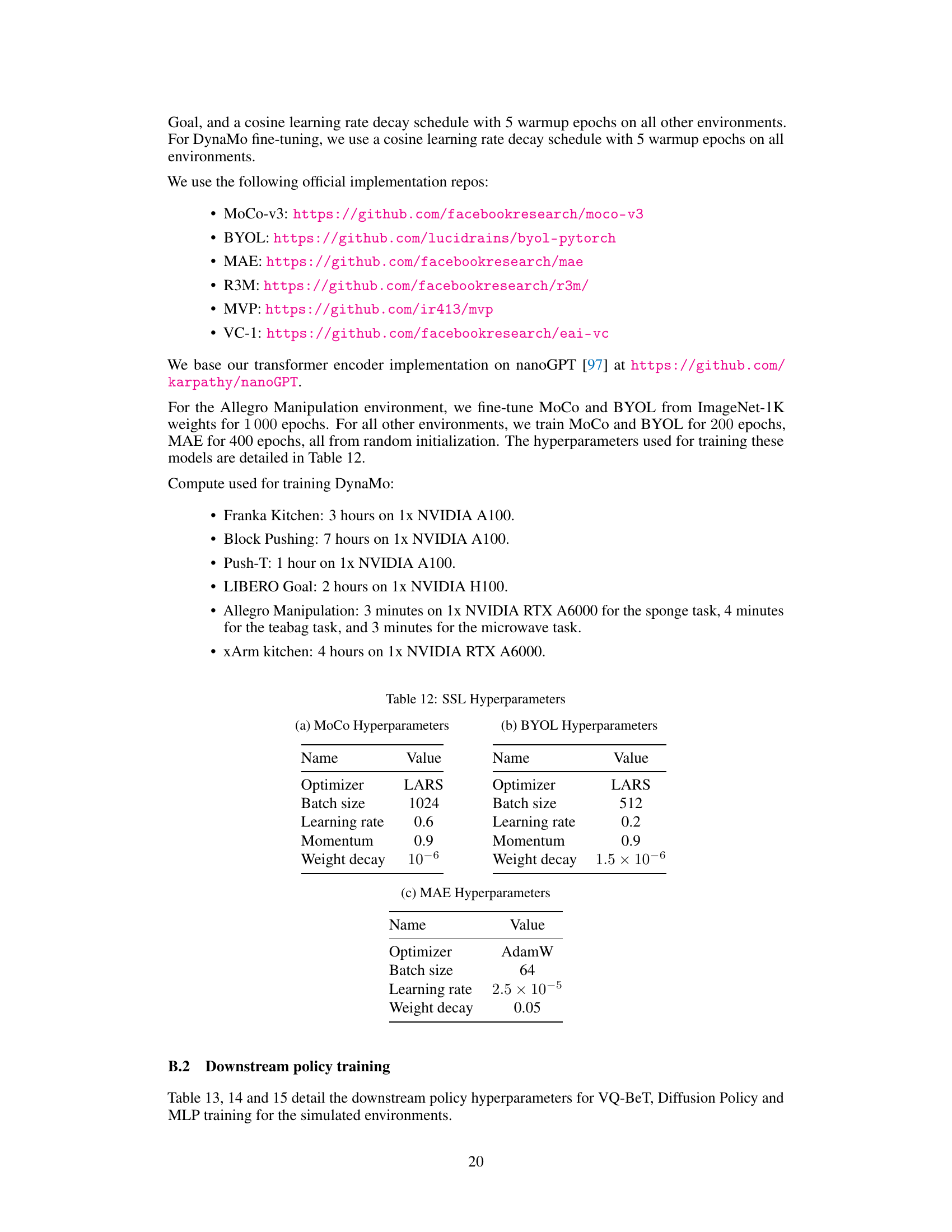

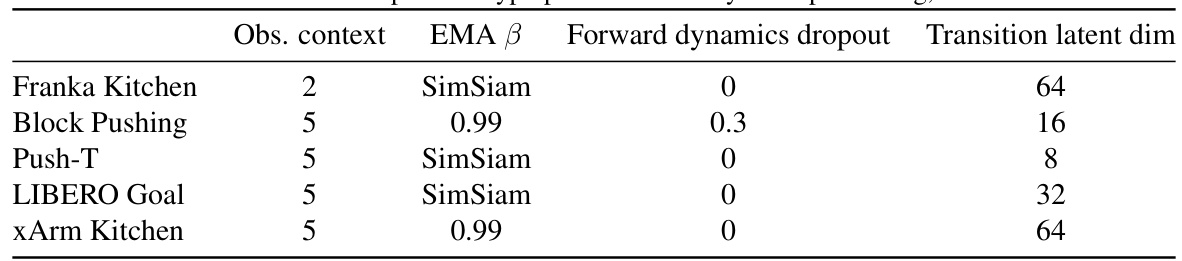

This table lists the hyperparameters used for pretraining the DynaMo model with random initialization. It shows how different hyperparameters were set for each of the five environments: Franka Kitchen, Block Pushing, Push-T, LIBERO Goal, and xArm Kitchen. The hyperparameters listed are: the observation context (number of frames considered), the EMA beta value (used for exponential moving average in the encoder), forward dynamics dropout rate, and the transition latent dimensionality. The table illustrates that the hyperparameter settings were customized for each environment to optimize performance.

This table compares the performance of different methods for training downstream visual imitation policies. The methods are compared based on their performance on four simulated benchmark tasks: Franka Kitchen, Block Pushing, Push-T, and LIBERO Goal. The table shows that DynaMo significantly outperforms other methods, especially on more challenging closed-loop tasks.

This table presents the hyperparameters used for pretraining the DynaMo model with random initialization. It shows the observation context, EMA beta value, and transition latent dimension used for each of the five environments: Franka Kitchen, Block Pushing, Push-T, LIBERO Goal, and xArm Kitchen. The hyperparameters were chosen based on empirical results and are specific to each environment due to differences in task complexity and data characteristics.

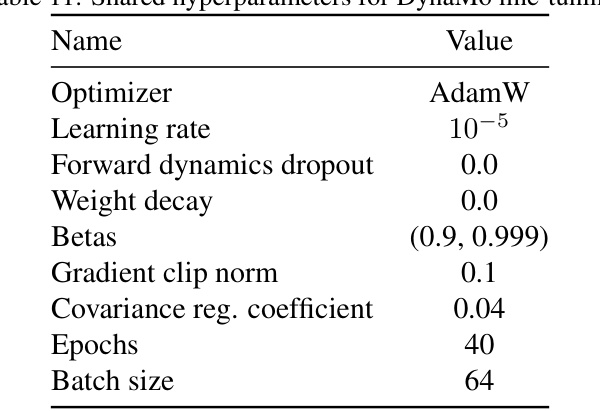

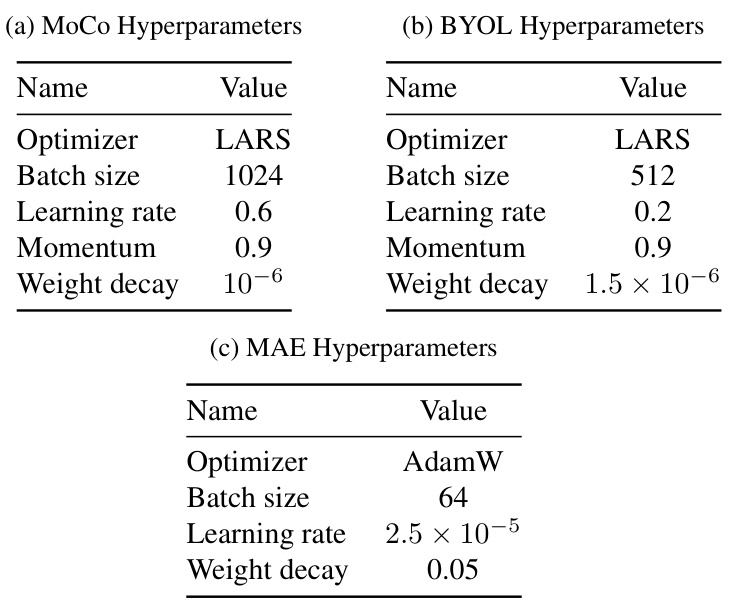

This table shows the hyperparameters used for fine-tuning the DynaMo model from ImageNet weights. It includes settings for the optimizer (AdamW), learning rate, dropout rates, weight decay, betas, gradient clipping, covariance regularization, number of epochs, and batch size.

This table presents a comparison of the downstream policy performance using different visual representation methods on four simulated robotic manipulation tasks. The performance is measured using several metrics for each task. The results show that DynaMo generally outperforms existing methods, particularly on more complex tasks.

This table shows the hyperparameters used for training the Vector-Quantized Behavior Transformer (VQ-BeT) policy on four different simulated benchmark environments: Franka Kitchen, Block Pushing, Push-T, and LIBERO Goal. The hyperparameters listed include batch size, number of epochs, window size, prediction window size, learning rate, and weight decay. These settings were specific to each environment and reflect the choices made to achieve optimal performance on each task.

This table shows the hyperparameters used for training the Diffusion Policy model on the Push-T simulated environment. The hyperparameters include the batch size, number of epochs, learning rate, weight decay, observation horizon, prediction horizon, and action horizon.

This table presents the hyperparameters used for training Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) policies in the Push-T environment. It lists the batch size, number of epochs, learning rate, weight decay, hidden layer dimensions, hidden layer depth, observation context, and prediction context. These settings were used for the downstream policy training experiment to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed DynaMo method.

Full paper#