↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

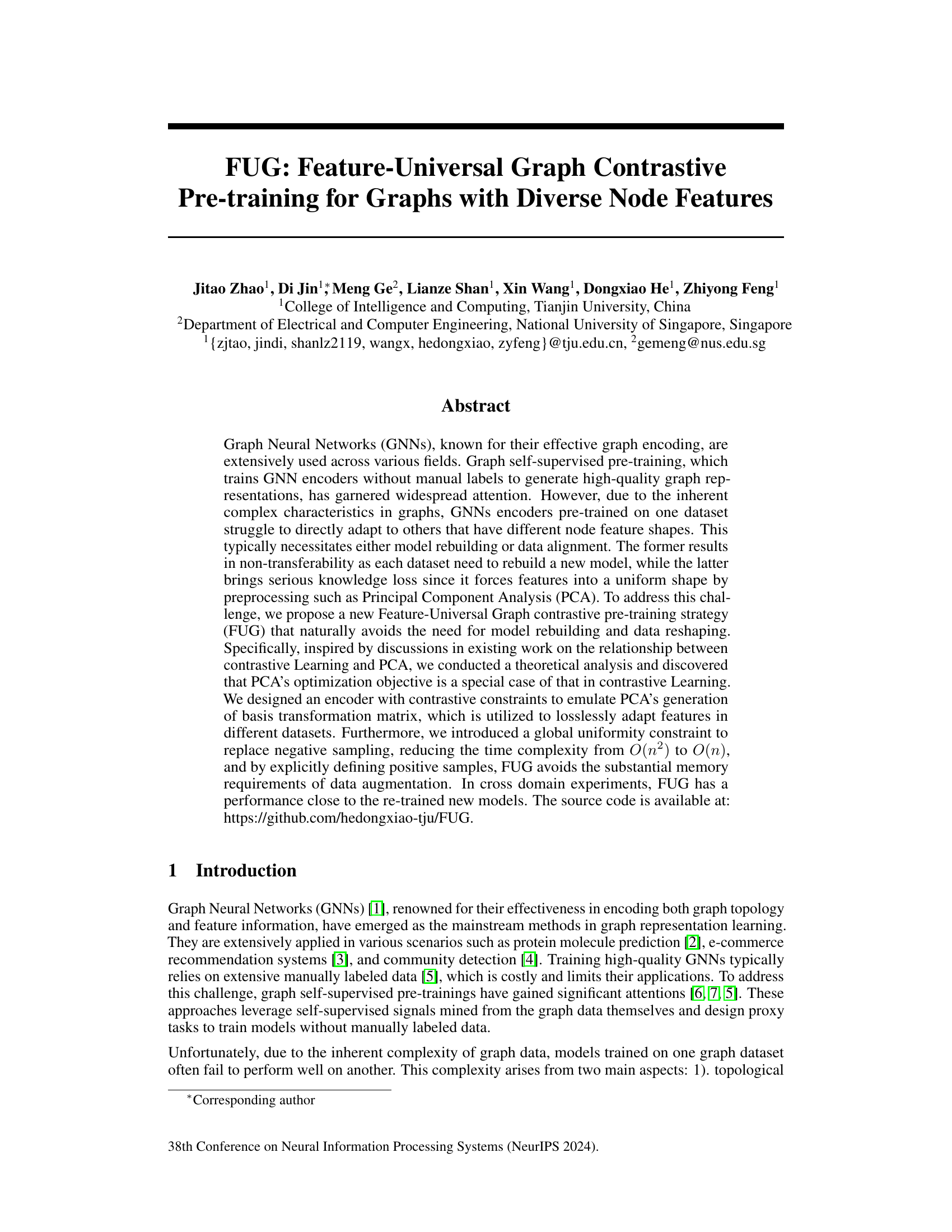

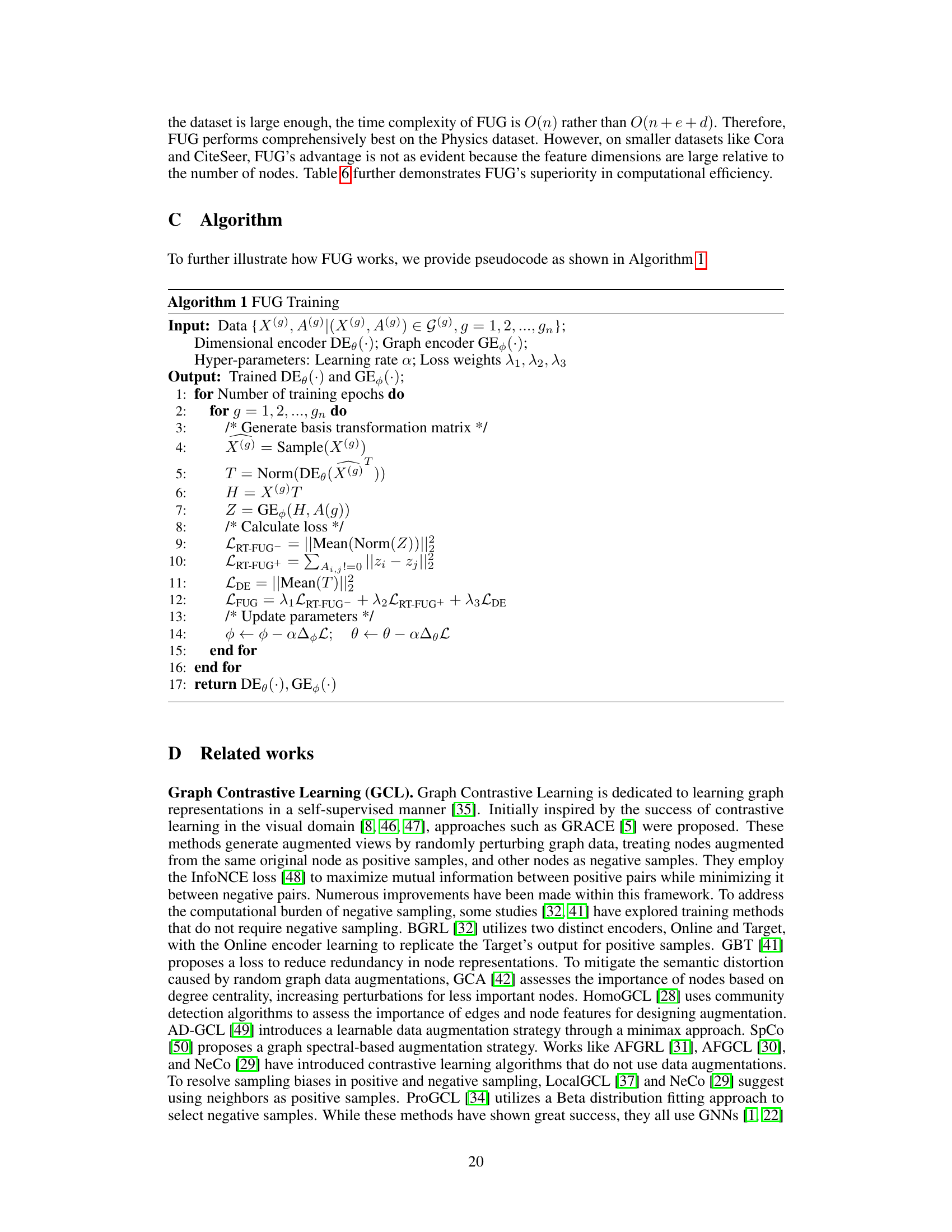

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are powerful tools for graph data analysis, but existing GNN pre-training methods struggle when applied to datasets with different node feature structures. This limits their applicability and necessitates model rebuilding or data preprocessing, both of which can lead to knowledge loss. This paper highlights the challenge of GNN transferability across datasets with diverse node features, a significant issue that limits the applicability of current self-supervised pre-training methods.

The paper introduces Feature-Universal Graph (FUG), a novel contrastive pre-training strategy that tackles this challenge head-on. FUG cleverly emulates the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) process using contrastive constraints, enabling lossless feature adaptation across different datasets. It also replaces negative sampling with a global uniformity constraint, drastically reducing computational complexity and memory requirements. Experimental results demonstrate FUG’s competitive performance with re-trained models in both in-domain and cross-domain settings, confirming its strong adaptability and transferability. This makes FUG a valuable contribution to the field of GNNs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with graph neural networks (GNNs). It directly addresses the critical challenge of GNN transferability across datasets with varying node feature shapes, a major limitation hindering broader adoption. The proposed Feature-Universal Graph (FUG) pre-training strategy offers a novel solution with improved efficiency and enhanced generalizability, opening exciting new avenues for research in GNN applications.

Visual Insights#

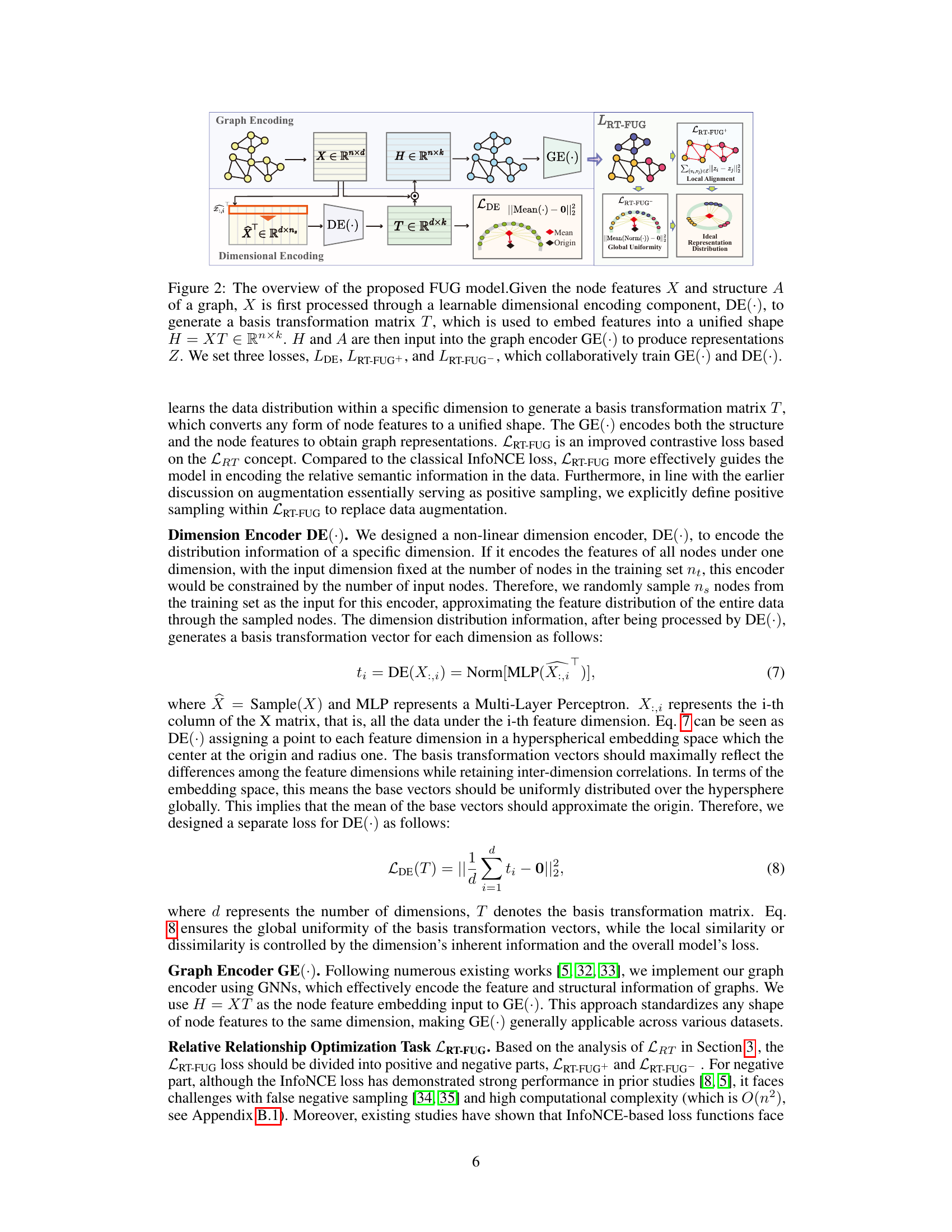

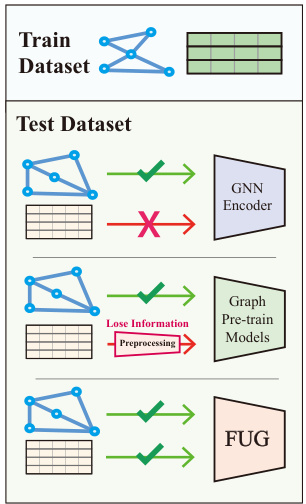

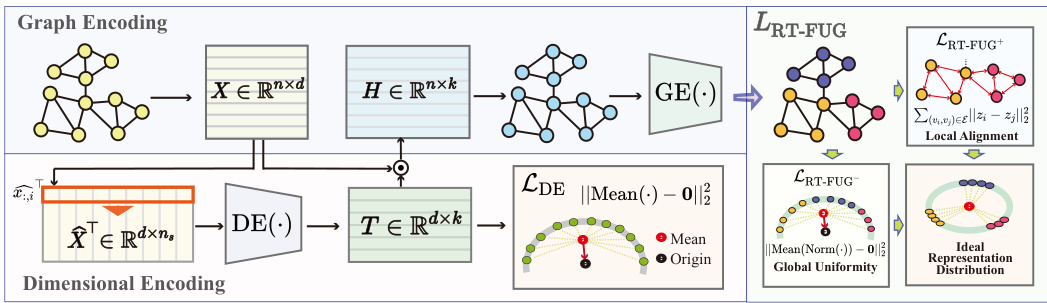

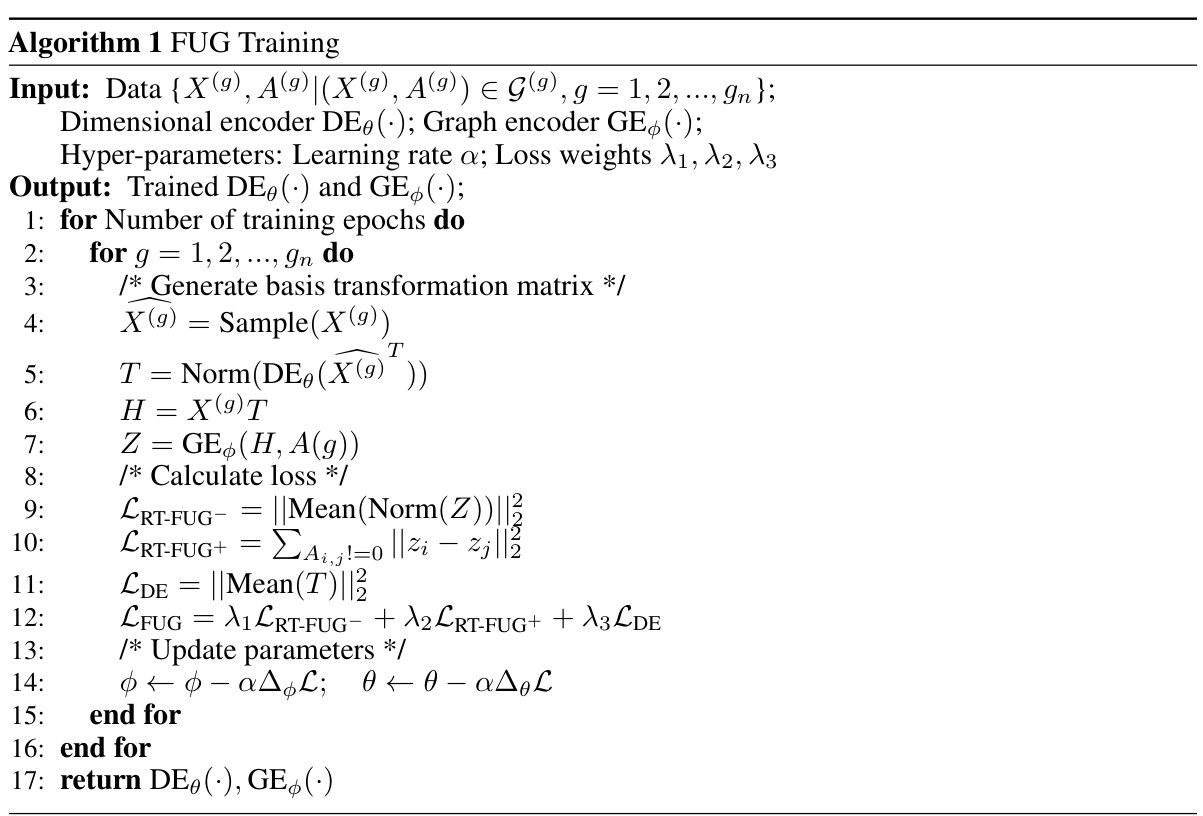

This figure illustrates the FUG model’s architecture and workflow. The model takes node features (X) and graph structure (A) as input. A dimensional encoder (DE) processes the features, producing a basis transformation matrix (T) to unify feature shapes. The transformed features (H) and the graph structure are then fed into a graph encoder (GE), generating final representations (Z). Three loss functions—LDE, LRT-FUG+, and LRT-FUG−—are used for training, ensuring dimensional encoding consistency and optimizing positive and negative sample relations.

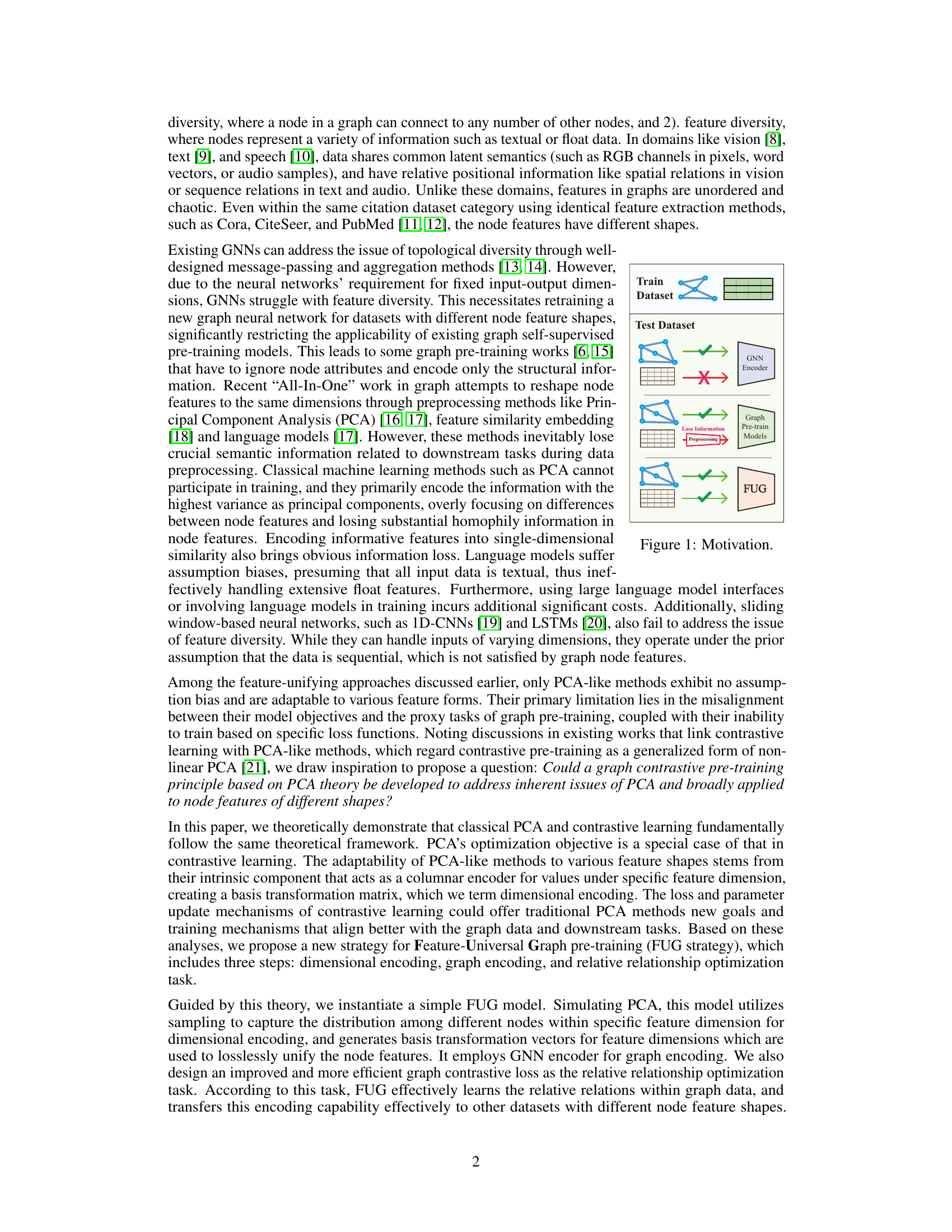

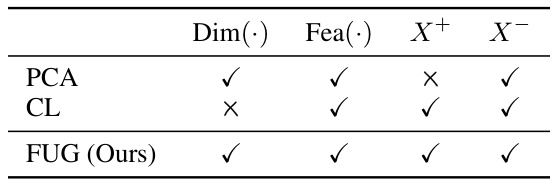

This table compares the components of PCA, contrastive learning models, and the proposed FUG method. It highlights the presence or absence of three key components: Dim(·) (a dimension-specific encoder), Fea(·) (an encoder of relationships between dimensions), positive samples (X+), and negative samples (X-). The table shows that PCA only uses Dim(·) and Fea(·), while traditional contrastive learning uses Fea(·), X+, and X-. The FUG method, however, includes all four components, aiming for a more comprehensive and adaptable approach.

In-depth insights#

FUG: Universal Graph#

The concept of “FUG: Universal Graph” suggests a novel approach to graph neural network (GNN) pre-training that addresses the limitations of existing methods. Current GNN pre-training struggles with graphs containing diverse node features, often necessitating model rebuilding or data preprocessing that leads to information loss. FUG aims to overcome this by employing a contrastive learning framework, inspired by the relationship between contrastive learning and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). This allows for lossless adaptation of features from different datasets without model rebuilding. A key aspect is the introduction of a ‘dimensional encoding’ component, which learns basis transformation matrices, emulating PCA to unify feature shapes across diverse datasets. This approach is theoretically grounded by showing that PCA’s optimization is a special case of contrastive learning. Additionally, FUG improves efficiency by replacing negative sampling with a global uniformity constraint, reducing complexity. Experimental results show competitive performance in both in-domain and cross-domain scenarios, highlighting FUG’s adaptability and transferability.

Contrastive Learning#

Contrastive learning is a self-supervised learning approach that learns representations by comparing similar and dissimilar data points. It leverages the relative relationships between data points rather than absolute semantics, making it robust and adaptable to various data modalities. The core idea is to pull similar examples closer together and push dissimilar examples apart in the embedding space. InfoNCE loss is a commonly used loss function, measuring the similarity between positive pairs and the dissimilarity between positive and negative pairs. A key challenge is effective negative sampling, as an insufficient or biased selection of negative samples can lead to poor performance. Data augmentation techniques are often used to create multiple views of the same data point, providing more positive pairs and increasing robustness. Recent research has explored contrastive learning across various domains, including images, text, and graphs, showing its broad applicability and effectiveness in various tasks, like representation learning and downstream classification. The field continues to explore novel loss functions, augmentation techniques, and negative sampling strategies to enhance performance and address inherent limitations.

Cross-Domain Transfer#

Cross-domain transfer, the ability of a model trained on one dataset to generalize to another, is a crucial aspect of robust machine learning. In the context of graph neural networks (GNNs), this is particularly challenging due to the inherent variability in graph structures and node features across different domains. This paper tackles this challenge by proposing a novel Feature-Universal Graph contrastive pre-training strategy (FUG). FUG cleverly avoids the need for model rebuilding or data reshaping, which are common but suboptimal approaches that hinder transferability and lose valuable information. Instead, FUG employs a contrastive learning framework inspired by Principal Component Analysis (PCA), theoretically demonstrating that PCA is a special case of contrastive learning. This insight allows FUG to learn a feature-universal representation, adapting effortlessly to diverse node feature shapes without significant information loss. The experimental results highlight FUG’s success in cross-domain transfer, achieving performance close to that of models retrained on new datasets. This demonstrates the effectiveness of FUG’s approach in promoting generalizability and reducing the need for domain-specific model training, ultimately enhancing the efficiency and scalability of GNNs in real-world applications.

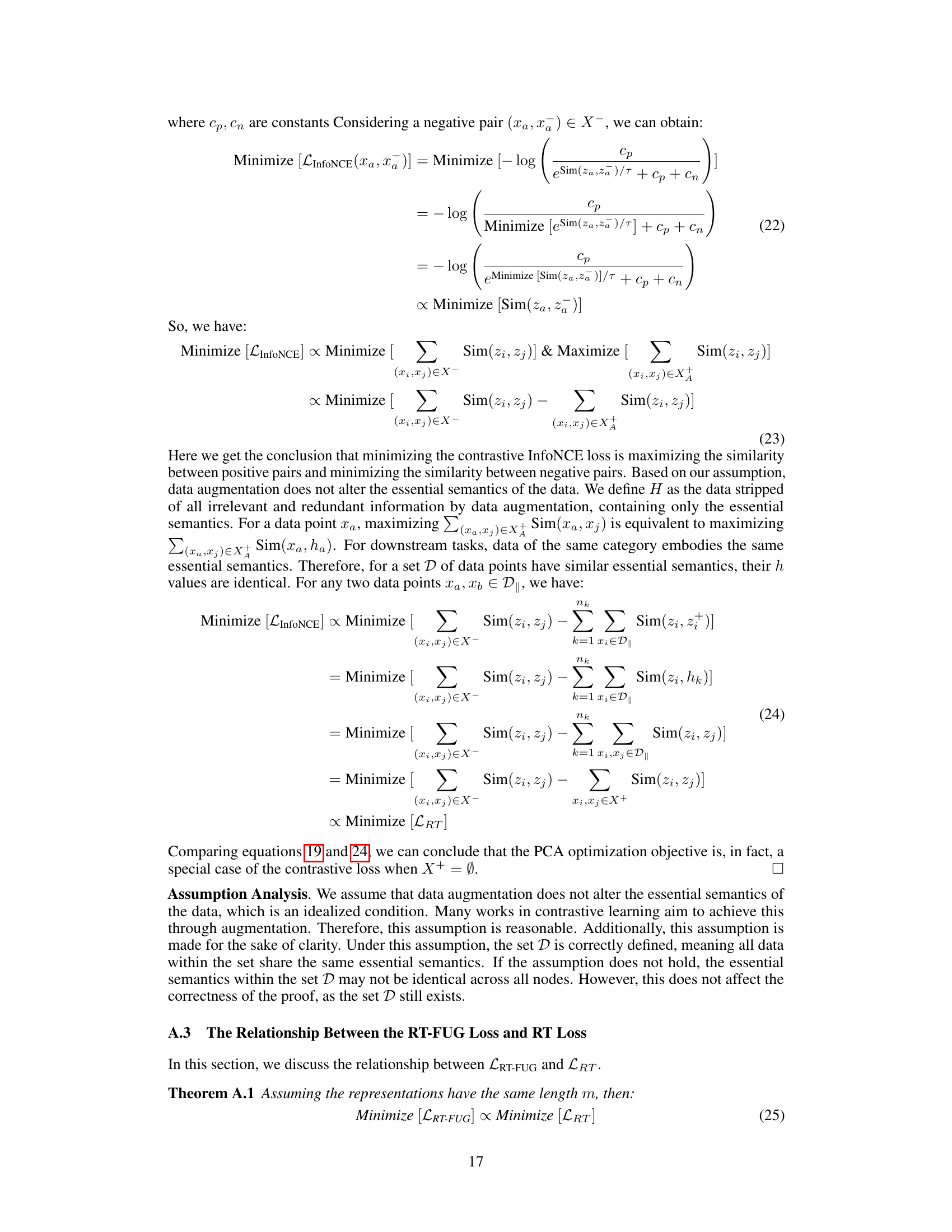

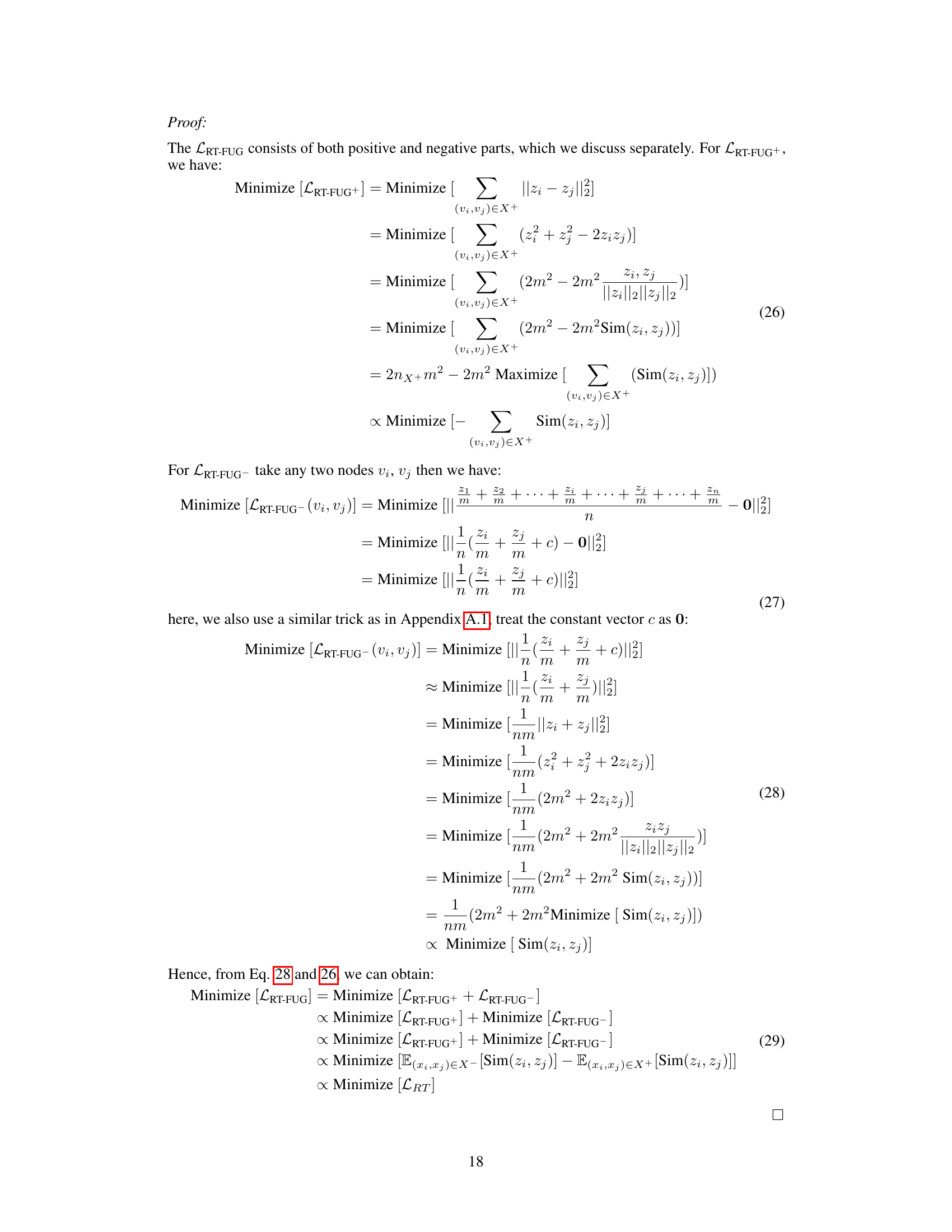

PCA-CL Link#

The PCA-CL Link section would explore the theoretical connections between Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and contrastive learning (CL). A key insight would be demonstrating that PCA’s optimization objective is a special case of the contrastive learning objective. This would involve a mathematical proof showing the equivalence under specific conditions. The analysis would likely highlight that both methods aim to encode relative relationships between data points rather than their absolute values. This relationship offers valuable insights for understanding the strengths and limitations of each approach. PCA’s ability to handle varied feature shapes effectively because of its focus on relative relationships, while contrastive learning’s flexibility in architecture and loss functions offer potential advantages for improved performance. The discussion might then explore why PCA often underperforms CL in downstream tasks, possibly attributing it to CL’s ability to incorporate non-linearity and capture complex interactions through neural networks and advanced loss functions. The section would be crucial for justifying the proposed methodology, explaining how the insights from this theoretical link informed the design of a feature-universal graph contrastive learning method.

Future Work#

The “Future Work” section of a research paper on Feature-Universal Graph Contrastive Pre-training (FUG) would naturally focus on extending the model’s capabilities and addressing its limitations. Extending FUG to handle heterophilic graphs is crucial, as the current model relies on the homophily assumption. This requires exploring alternative loss functions or incorporating graph structures that better capture the relationships in heterophilic data. Investigating the use of different graph neural network (GNN) architectures beyond the GCN used in FUG could improve performance and adaptability. Another area of potential exploration is developing a pre-trained FUG model for broader use. This would enable researchers to directly leverage the model’s powerful feature encoding capabilities, accelerating downstream task performance and promoting easier accessibility within the research community. Finally, a thorough analysis of FUG’s scalability to extremely large graphs and exploring methods for efficient training on such datasets would be a valuable contribution.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the Feature-Universal Graph (FUG) model’s architecture and training process. It consists of two main components: a dimensional encoder (DE) and a graph encoder (GE). The DE processes node features (X) to produce a basis transformation matrix (T) for unifying feature shapes across different datasets, resulting in a unified feature representation (H). The GE then takes H and the graph structure (A) as input and produces the final graph representation (Z). The training involves three losses: LDE to enforce global uniformity in the learned transformations, LRT-FUG+ to optimize relationships between positive node pairs, and LRT-FUG- to optimize the global uniformity of the graph representations. The figure visually depicts these steps and the effects of each loss.

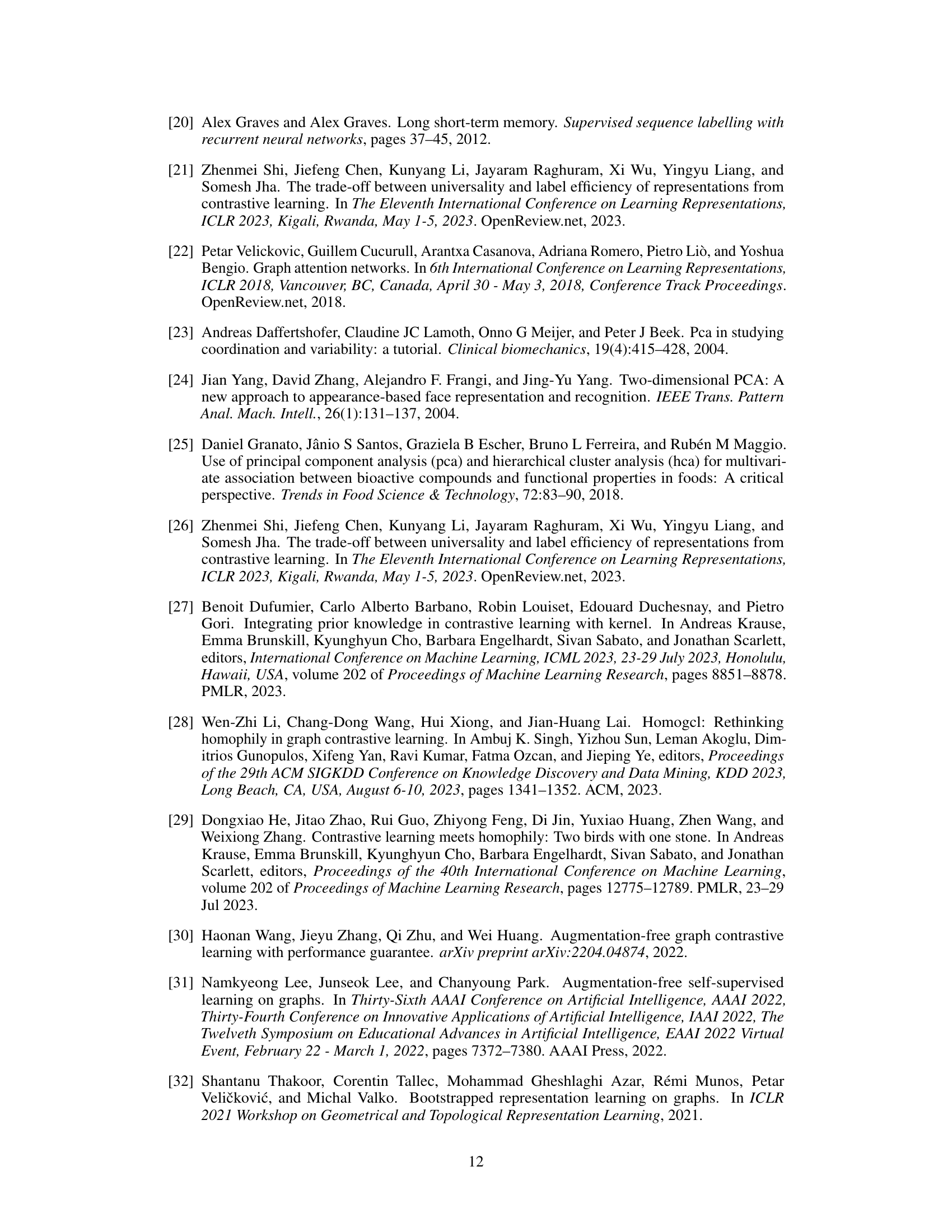

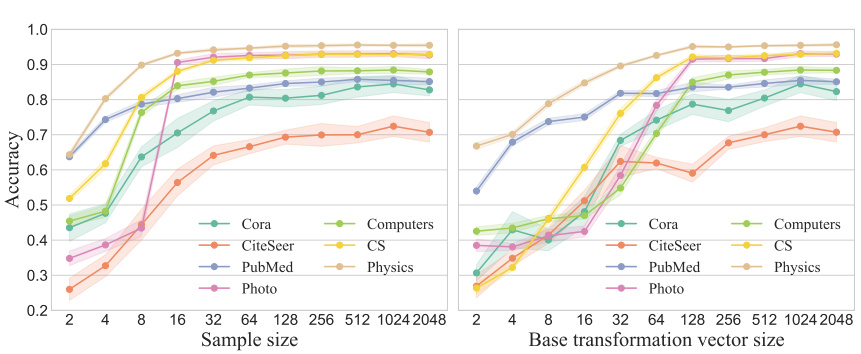

This figure shows the impact of different hyperparameters on the performance of the FUG model. The left panel displays how varying the sample size affects accuracy across multiple datasets. The right panel illustrates the effect of changing the base transformation vector size on the accuracy of the model on different datasets. The shaded areas around the lines represent confidence intervals, showing the variability in model performance.

This figure shows the architecture of the Feature-Universal Graph contrastive pre-training (FUG) model. The model consists of three main components: a learnable dimensional encoding component (DE), a graph encoder (GE), and a relative relationship optimization task (LRT-FUG). The DE component learns a basis transformation matrix T that converts node features into a unified shape. The GE component encodes both the transformed node features and the graph structure to produce graph representations. The LRT-FUG loss function guides the model to learn relative relationships between nodes, improving performance and generalization. Three losses, LDE, LRT-FUG+, and LRT-FUG-, are used to collaboratively train the DE and GE components.

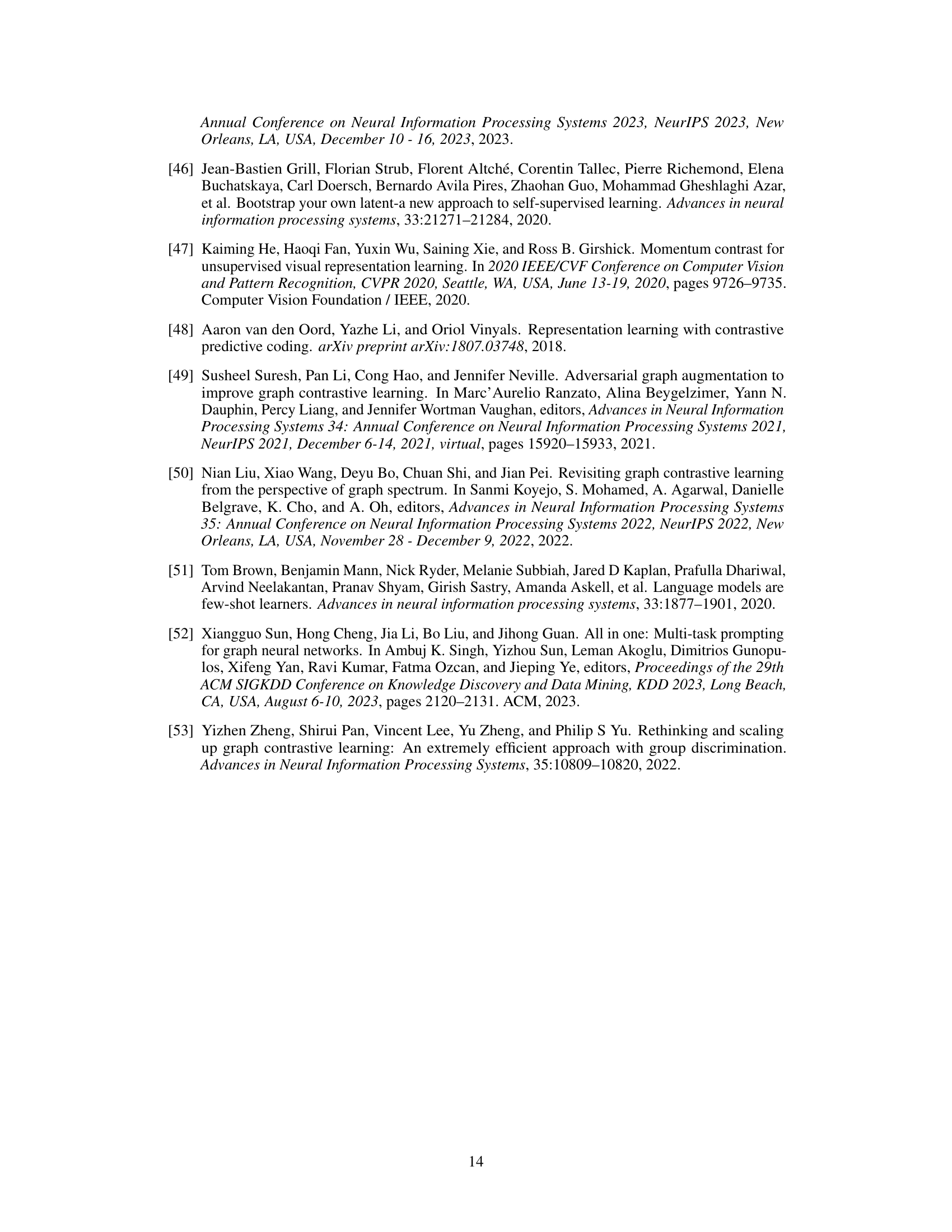

More on tables

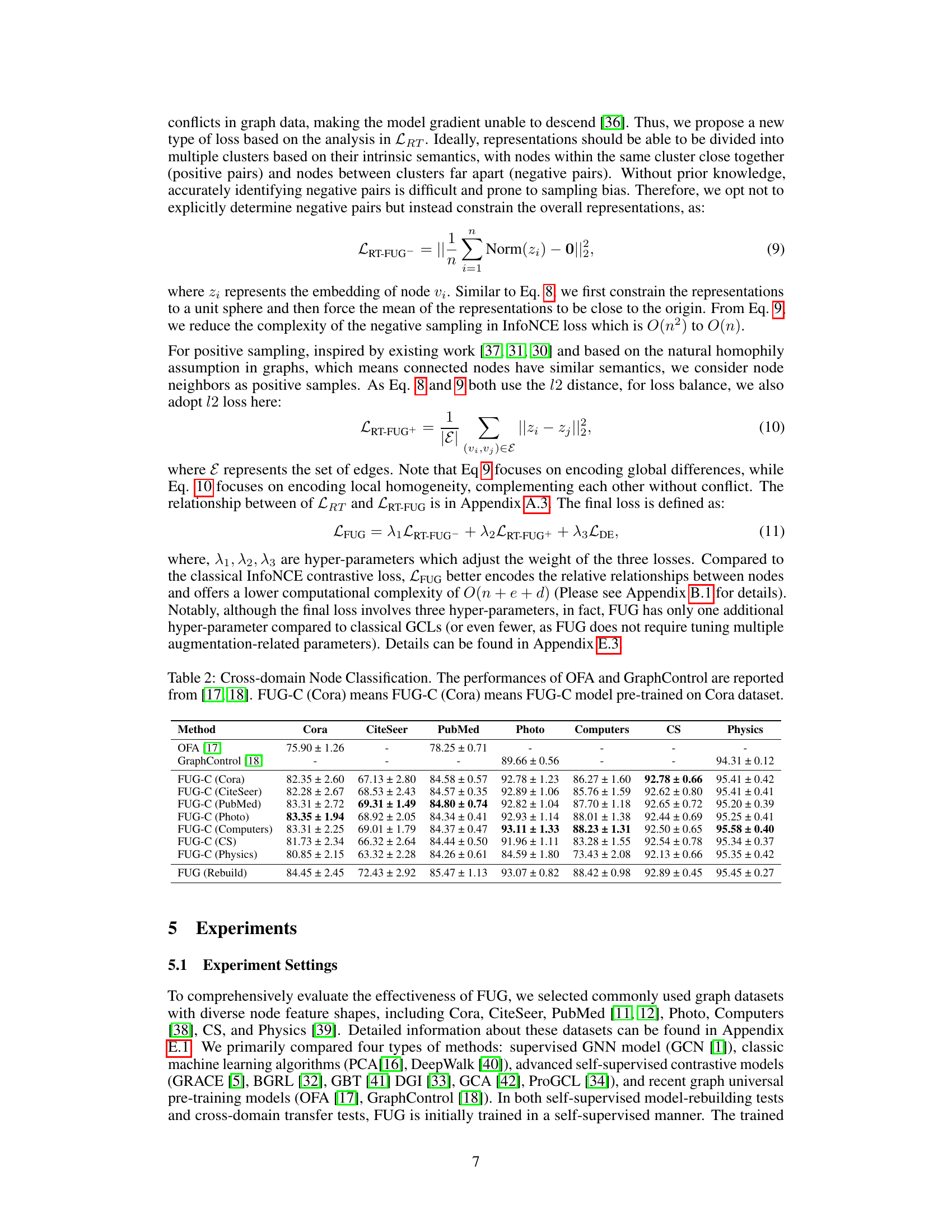

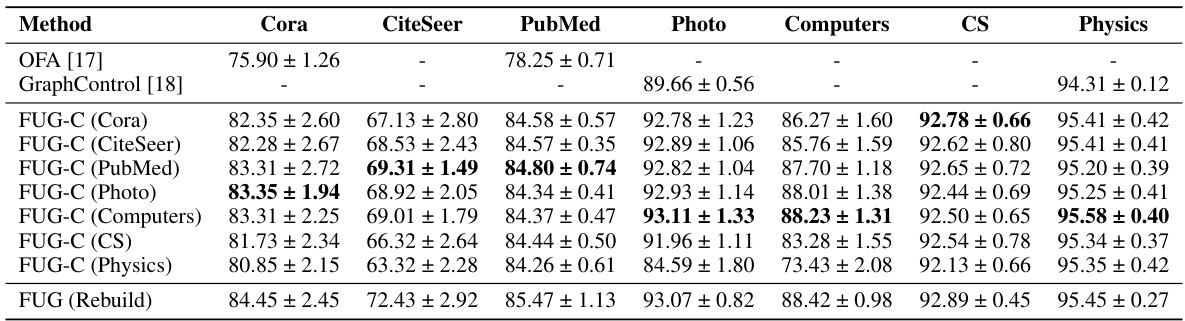

This table presents the results of cross-domain node classification experiments. It compares the performance of the proposed FUG model (trained on different datasets) against state-of-the-art models (OFA and GraphControl). The results demonstrate FUG’s ability to adapt to datasets with different node feature shapes and its competitive performance compared to models that either reshape features or ignore node attributes.

This table presents the results of node classification experiments conducted within the same dataset (intra-domain). It compares the performance of various methods, including FUG, against state-of-the-art self-supervised and supervised methods on several benchmark datasets. The table highlights the best and second-best performing methods for each dataset, indicating FUG’s competitiveness in this setting. ‘OOM’ signifies that the model ran out of memory on the specified hardware.

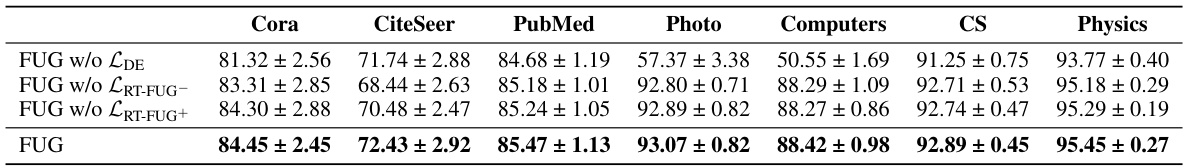

This table presents the ablation study results for the FUG model, evaluating the impact of removing each loss function (LDE, LRT-FUG-, LRT-FUG+) individually and comparing the results to the full FUG model. The results are shown in terms of node classification accuracy for several datasets (Cora, CiteSeer, PubMed, Photo, Computers, CS, Physics). The study demonstrates the contribution of each loss function to the overall performance of the FUG model.

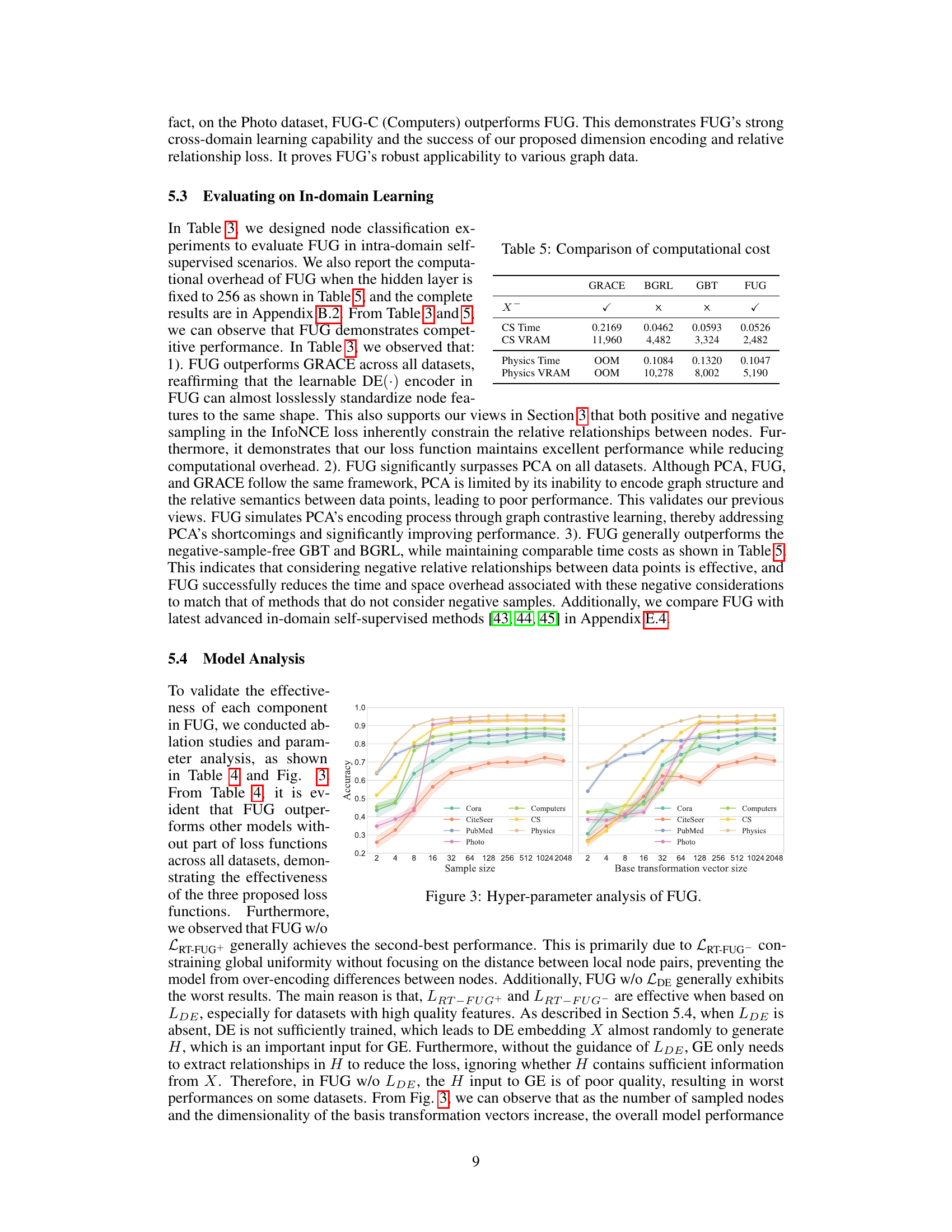

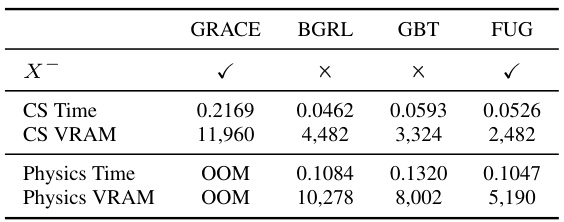

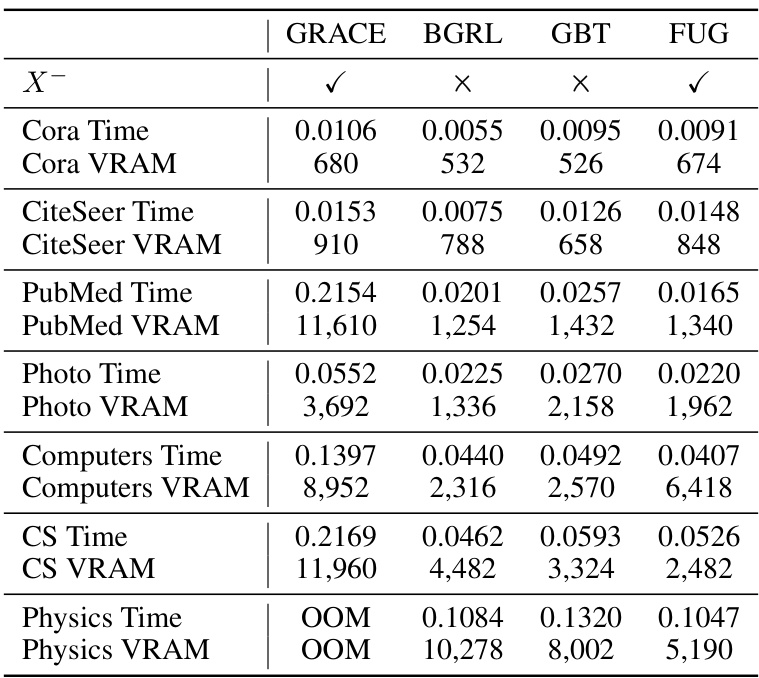

This table compares the computational cost (time and VRAM) of four different methods: GRACE, BGRL, GBT, and FUG, on two datasets: CS and Physics. It shows that FUG has a lower computational cost than GRACE, particularly on the larger Physics dataset where GRACE runs out of memory (OOM). The table highlights FUG’s efficiency in terms of resource utilization.

This table presents the results of cross-domain node classification experiments. It compares the performance of the proposed FUG model (trained on various datasets) against state-of-the-art models like OFA and GraphControl. The results highlight FUG’s ability to adapt to datasets with different node feature shapes, showcasing its transferability across domains.

This table presents the results of cross-domain node classification experiments. It compares the performance of the proposed Feature-Universal Graph (FUG) model against state-of-the-art methods (OFA and GraphControl) on several datasets. The FUG model is pre-trained on one dataset and then tested on others, demonstrating its ability to transfer knowledge across domains. The results show FUG’s performance is competitive with models that have the advantage of being trained and tested on the same datasets.

This table presents the statistics of seven graph datasets used in the paper’s experiments. Each dataset is described by the number of nodes, edges, features per node, and number of classes.

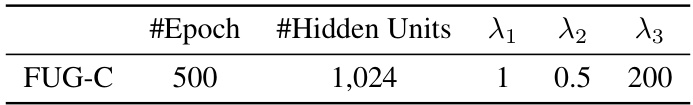

This table presents the hyperparameters used for the FUG-C model during cross-domain learning experiments. It shows the number of training epochs, the size of the hidden units in the model, and the weighting factors (lambda values) applied to the three loss functions (LRT-FUG+, LRT-FUG-, and LDE) within the FUG model. These hyperparameters were kept constant across different datasets during the cross-domain learning experiments to test the model’s adaptability.

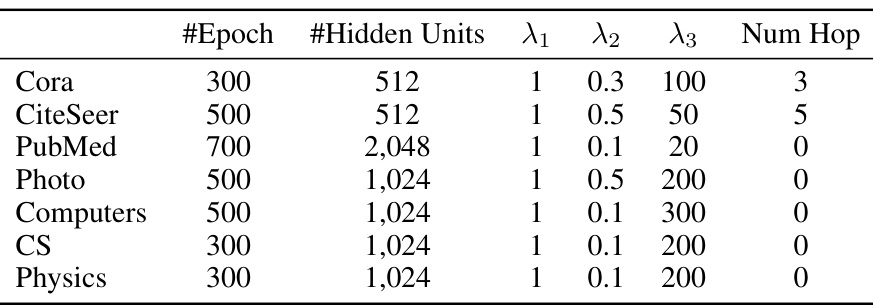

This table shows the hyper-parameters used for the FUG model during in-domain learning experiments on different datasets. The parameters include the number of training epochs, the number of hidden units in the model, and the weights assigned to each of the three loss functions used in the FUG training process (LDE, LRT-FUG+, and LRT-FUG-). The number of hop for topological propagation during embedding is also listed.

This table presents the results of cross-domain node classification experiments. It compares the performance of the proposed FUG model (pre-trained on various datasets) against state-of-the-art methods, OFA and GraphControl, demonstrating FUG’s ability to adapt to datasets with different node feature shapes.

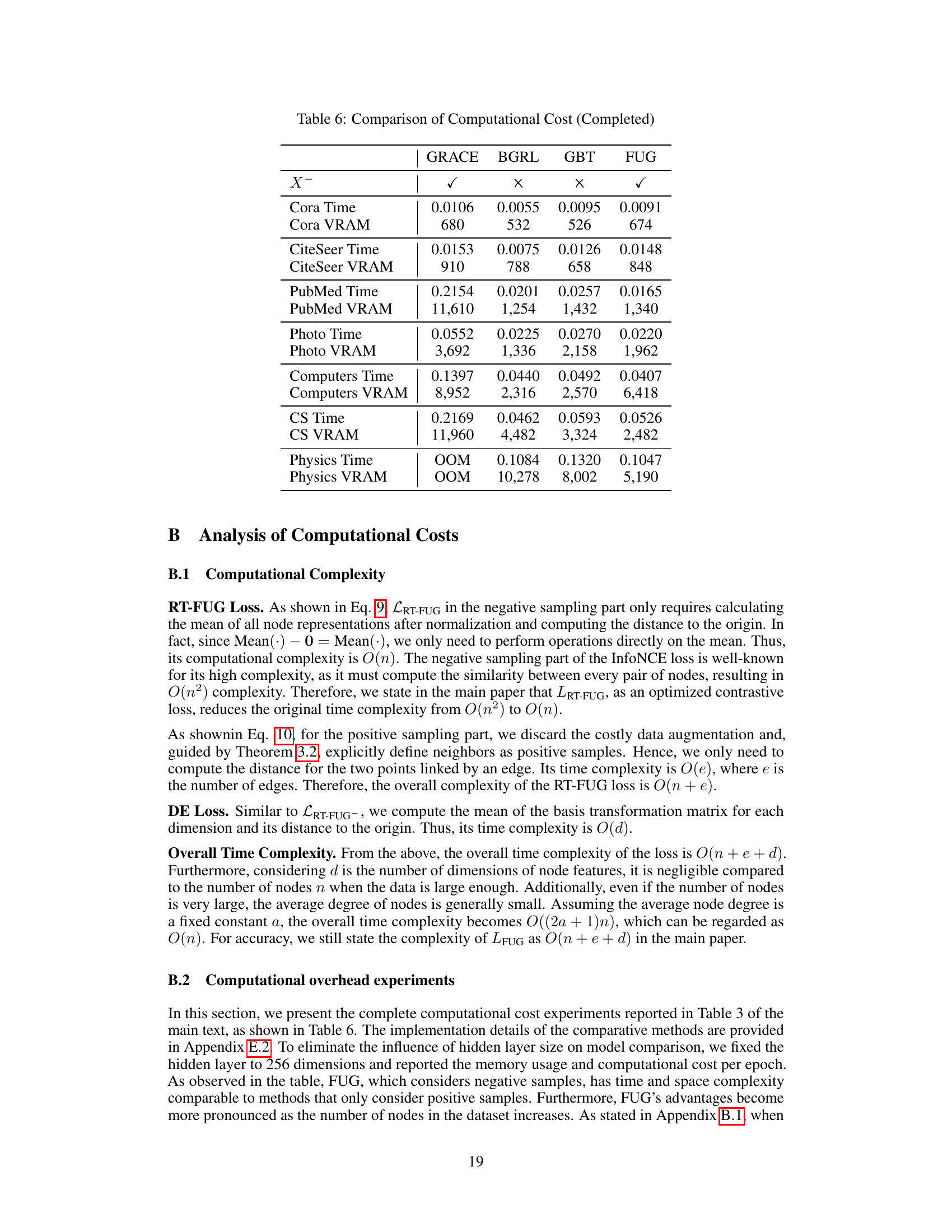

Full paper#