↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional speech recognition research often treats auditory, visual, and audiovisual (AV) modalities separately. This leads to multiple models and inference pipelines, increasing computational costs and memory usage. Recent self-supervised methods, while aiming for unified training, typically still result in separate fine-tuning for each modality. This paper addresses these shortcomings.

The proposed method, Unified Speech Recognition (USR), employs a single model trained for all three modalities. This model combines self-supervised pre-training, a novel semi-supervised pseudo-labeling technique, and multi-modal feature extraction to enhance model training and address overfitting issues. This innovative approach achieves state-of-the-art results across multiple benchmarks, demonstrating the efficiency and efficacy of a unified training strategy for improved speech recognition.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in speech recognition as it presents a novel unified training strategy for auditory, visual, and audiovisual speech recognition. It overcomes the limitations of separate models by enhancing performance and reducing memory requirements. The findings challenge the established paradigm and pave the way for efficient and powerful multimodal speech recognition systems. This approach is relevant to current trends in self-supervised and semi-supervised learning, opening new avenues for exploration within the multimodal domain.

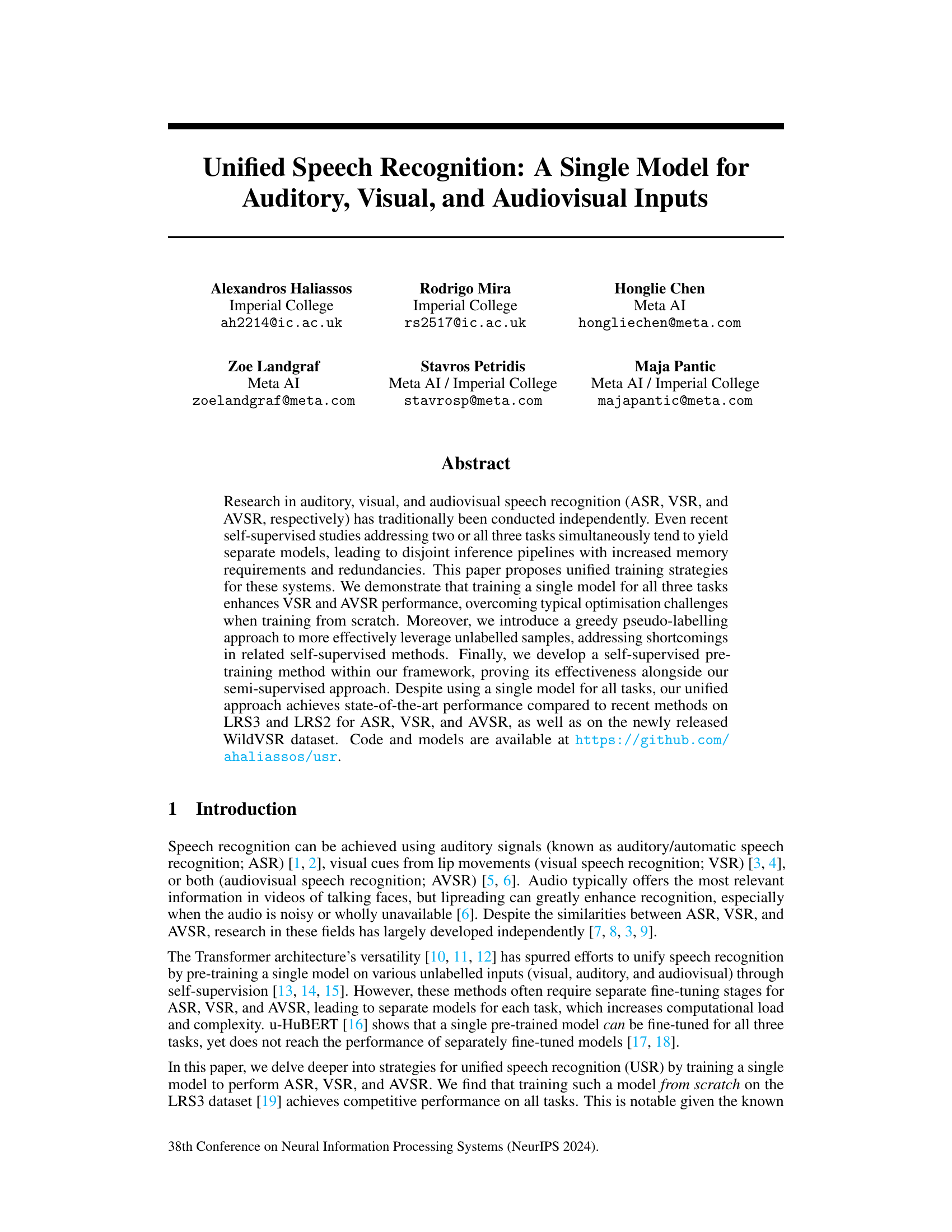

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the unified speech recognition (USR) model architecture. It shows the model’s three main components: self-supervised pre-training, semi-supervised fine-tuning, and multi-modal feature extraction. The self-supervised pre-training stage uses a teacher-student approach with masked inputs to learn representations from unlabeled data. The semi-supervised fine-tuning stage leverages pseudo-labels from the teacher to train on both labeled and unlabeled data. The multi-modal feature extraction component processes auditory, visual, and audiovisual inputs to create a unified representation.

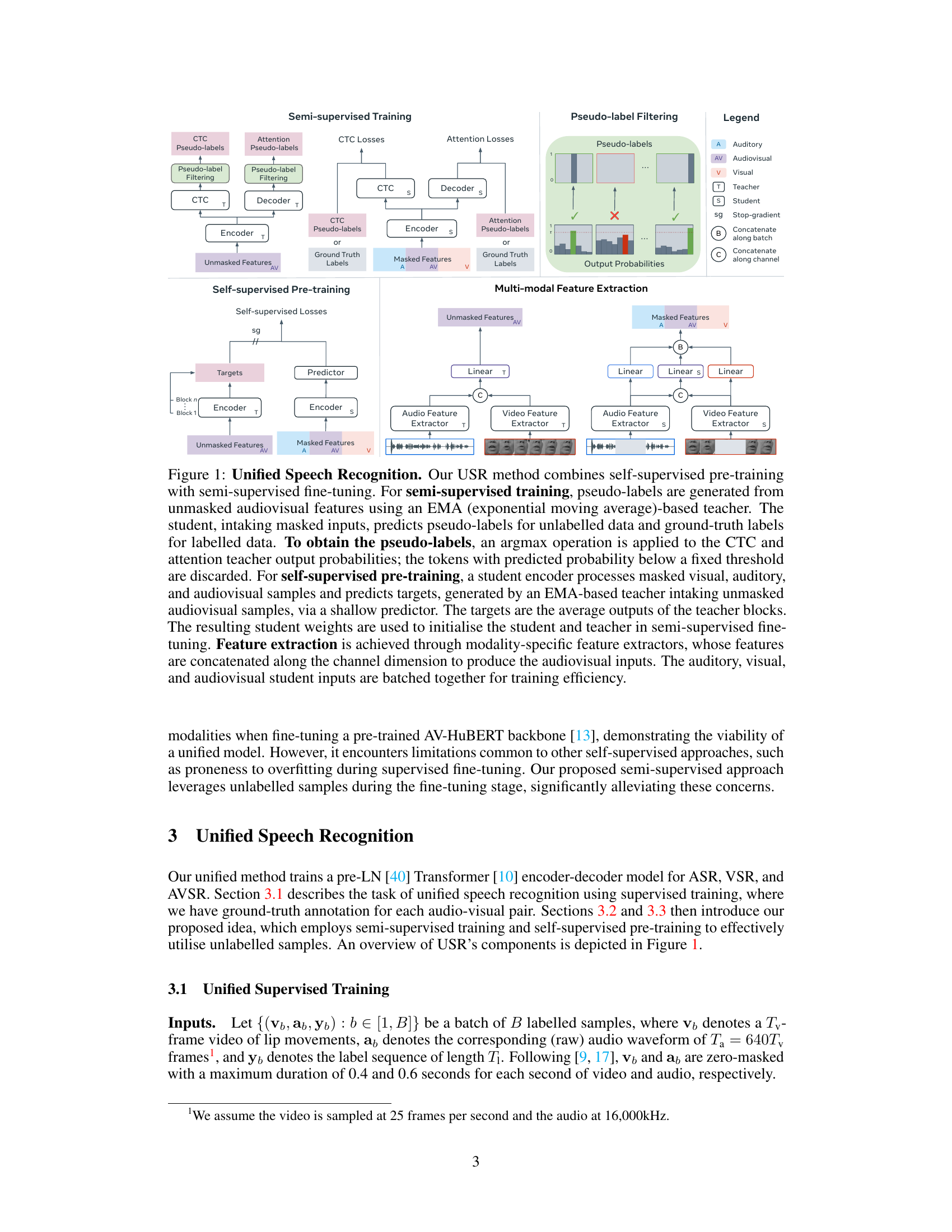

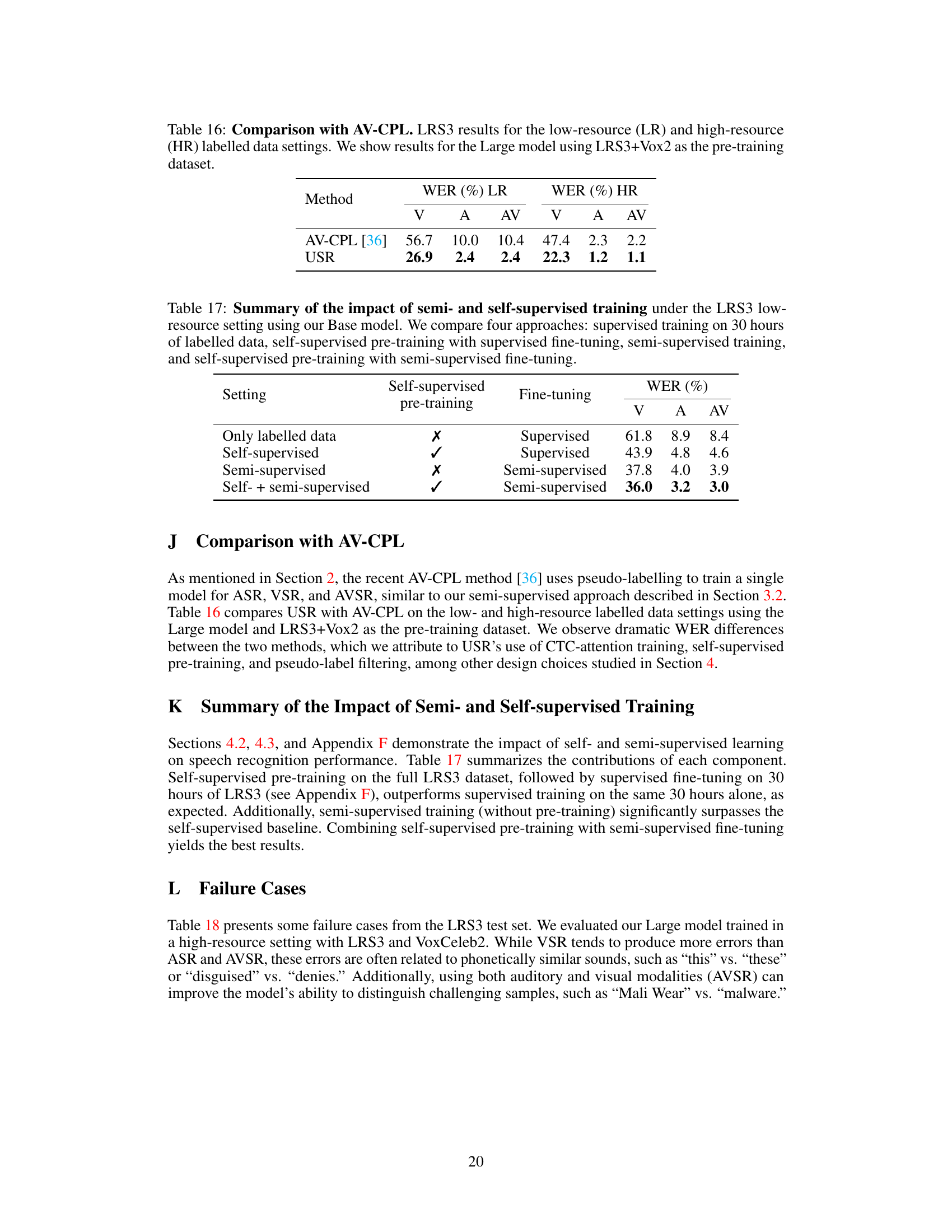

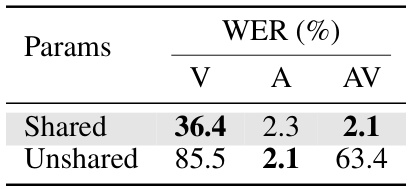

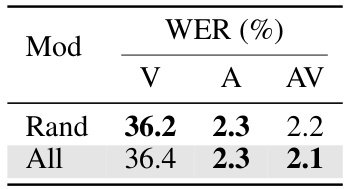

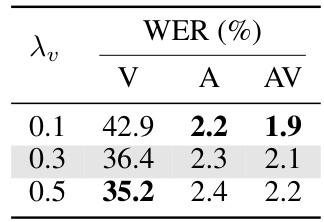

This table presents ablation studies on a supervised training approach using the full LRS3 dataset. It investigates three aspects: (a) whether to share model parameters across different modalities (visual, auditory, and audiovisual) or use separate models for each, (b) different strategies for sampling the modalities during training (random sampling vs. weighted average of losses), and (c) the impact of varying the relative weight given to the video loss in the overall loss function. The results showcase the effectiveness of using a single, shared model and weighted average loss for optimal performance.

In-depth insights#

Unified ASR Model#

A unified ASR model aims to integrate auditory, visual, and audiovisual speech recognition into a single system, overcoming the limitations of independently trained models. This approach offers several advantages: enhanced performance, especially in noisy conditions where visual cues compensate for audio limitations; reduced computational costs by sharing parameters and inference pipelines; and a more robust system due to the complementary information provided by multiple modalities. However, building a truly effective unified ASR model presents considerable challenges, including the need for large, diverse, and accurately labeled datasets that include all three modalities; the development of training strategies that effectively handle the different characteristics of audio and visual data; and addressing potential overfitting due to the increased complexity of the model. The success of a unified ASR model hinges on careful consideration of these factors, which will greatly influence the model’s ability to generalize across diverse acoustic environments and speaker characteristics.

Pseudo-Labeling#

The concept of pseudo-labeling in the context of the research paper centers around leveraging unlabeled data to enhance model performance. It’s a semi-supervised learning technique where a model, initially trained on a limited labeled dataset, generates predictions (pseudo-labels) for unlabeled instances. These pseudo-labels are then incorporated into the training process, augmenting the labeled data and improving the model’s ability to generalize. A crucial aspect is filtering low-confidence predictions to avoid introducing noisy or misleading data that can negatively impact training. The paper highlights the benefits of combining pseudo-labeling with a self-supervised pre-training phase, thereby improving the optimization landscape and mitigating overfitting, particularly crucial in visual speech recognition (VSR) where labeled data is often scarce. The use of an exponential moving average (EMA)-based teacher model adds a layer of stability, providing more reliable pseudo-labels. This approach is shown to significantly improve VSR and audiovisual speech recognition (AVSR) performance, ultimately contributing to a unified speech recognition system.

Self-Supervised#

Self-supervised learning, a crucial aspect of the research, leverages unlabeled data to enhance model performance. The study explores this by pre-training a model on unlabeled audio-visual data. This pre-training phase serves as a foundation for subsequent semi-supervised fine-tuning on a smaller dataset, effectively using both labelled and unlabelled data. The approach addresses challenges of overfitting that frequently arise when directly fine-tuning on limited labelled data, a common problem in speech recognition. A key innovation is a novel greedy pseudo-labelling approach, which efficiently generates high-quality labels for the unlabelled data. The model’s unified architecture, processing auditory, visual and audio-visual inputs simultaneously, also contributes to its effectiveness, avoiding the need for multiple separate models. Results indicate that this self-supervised strategy significantly boosts performance across various speech recognition tasks, particularly in low-resource settings where labelled data is scarce.

Multimodal Fusion#

In multimodal fusion for speech recognition, the core challenge lies in effectively combining auditory and visual information. Early methods often relied on simple concatenation or weighted averaging, but these approaches fail to capture the complex interplay between modalities. More sophisticated techniques, such as attention mechanisms, have emerged, enabling the model to selectively focus on relevant audio-visual features. Deep learning models have revolutionized multimodal fusion, allowing for the automatic learning of optimal feature representations and fusion strategies. Transformer architectures have shown particular promise, given their ability to model long-range dependencies and effectively integrate diverse data streams. However, optimization challenges remain, especially in addressing the inherent differences in the nature and quality of audio and visual data. Future research should focus on improving robust fusion strategies that are less sensitive to noise, variations in speaker characteristics, and other real-world complexities. Exploration of novel neural network architectures and loss functions may also yield improvements. Finally, rigorous evaluation methods and publicly available datasets are crucial to comparing different multimodal fusion approaches and fostering the development of more accurate and reliable speech recognition systems.

Future Work#

The authors suggest several avenues for future research. Improving pseudo-label quality is paramount; exploring alternative filtering mechanisms beyond simple thresholding could significantly enhance performance. They also propose investigating alternative encoder architectures, potentially yielding more robust and efficient models. Incorporating audio-only data into the training process, expanding beyond the audiovisual datasets already used, presents another promising direction. Finally, they highlight the need for further exploration of the unified model’s robustness across diverse acoustic conditions and varying levels of noise, crucial for real-world applicability. Addressing these points would strengthen the unified speech recognition model and expand its practical utility.

More visual insights#

More on tables

This table presents ablation studies on the supervised training of a unified speech recognition model using the full LRS3 dataset. It explores three key aspects: (a) whether to share model parameters across all modalities (visual, auditory, and audiovisual) or use separate models; (b) the method of modality sampling during training (random sampling vs. using all modalities in each iteration); and (c) the relative weight given to the video loss during training. The table shows Word Error Rates (WER) for each modality under various settings, highlighting the impact of each choice on model performance.

This table presents ablation studies on the supervised training of the unified speech recognition model. It explores three aspects: (a) using a single shared model versus modality-specific models; (b) different data sampling strategies for training (random vs. all modalities); and (c) varying the weight of visual modality loss. The results, expressed as Word Error Rates (WERs), demonstrate the effectiveness of the unified approach in overcoming optimization challenges associated with training from scratch, particularly in visual and audiovisual modalities.

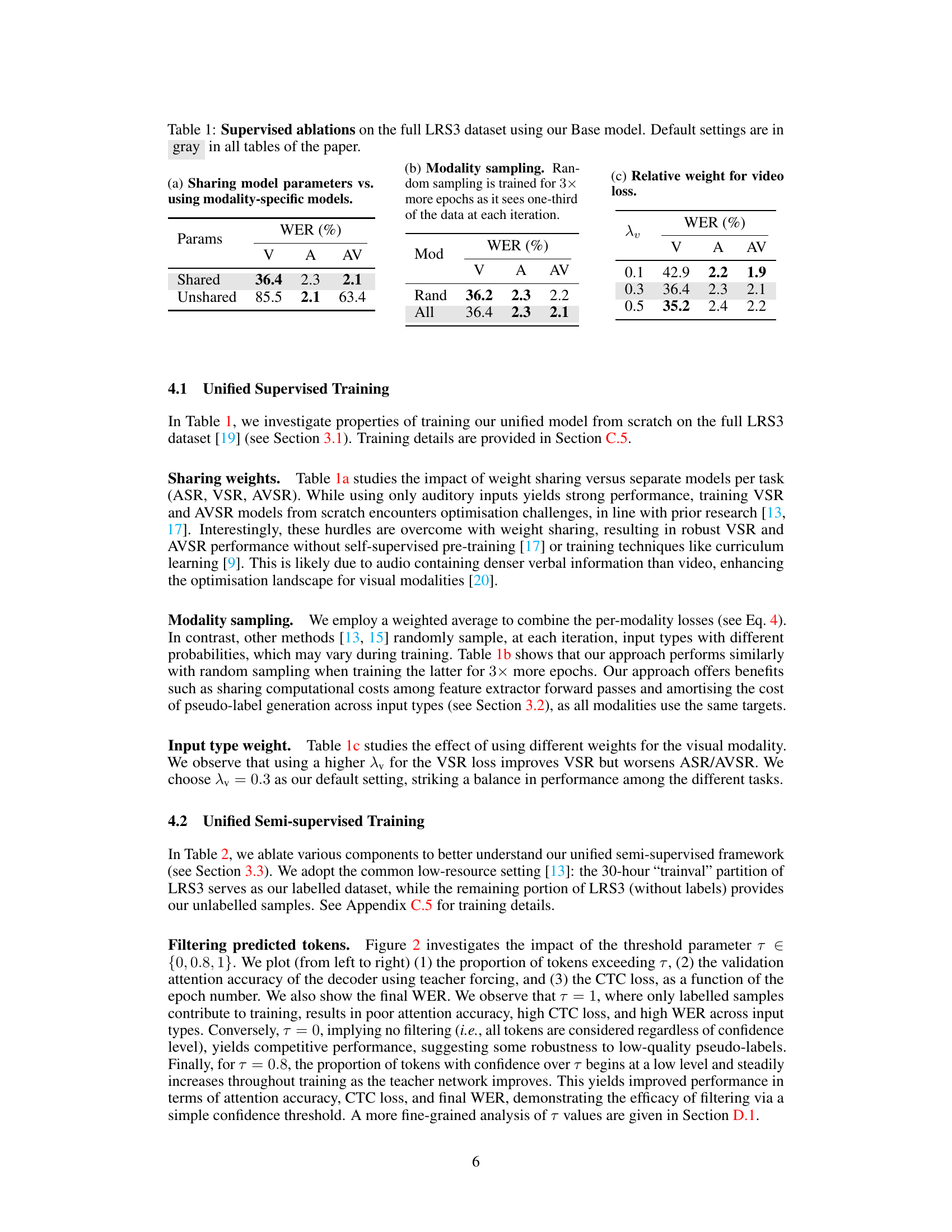

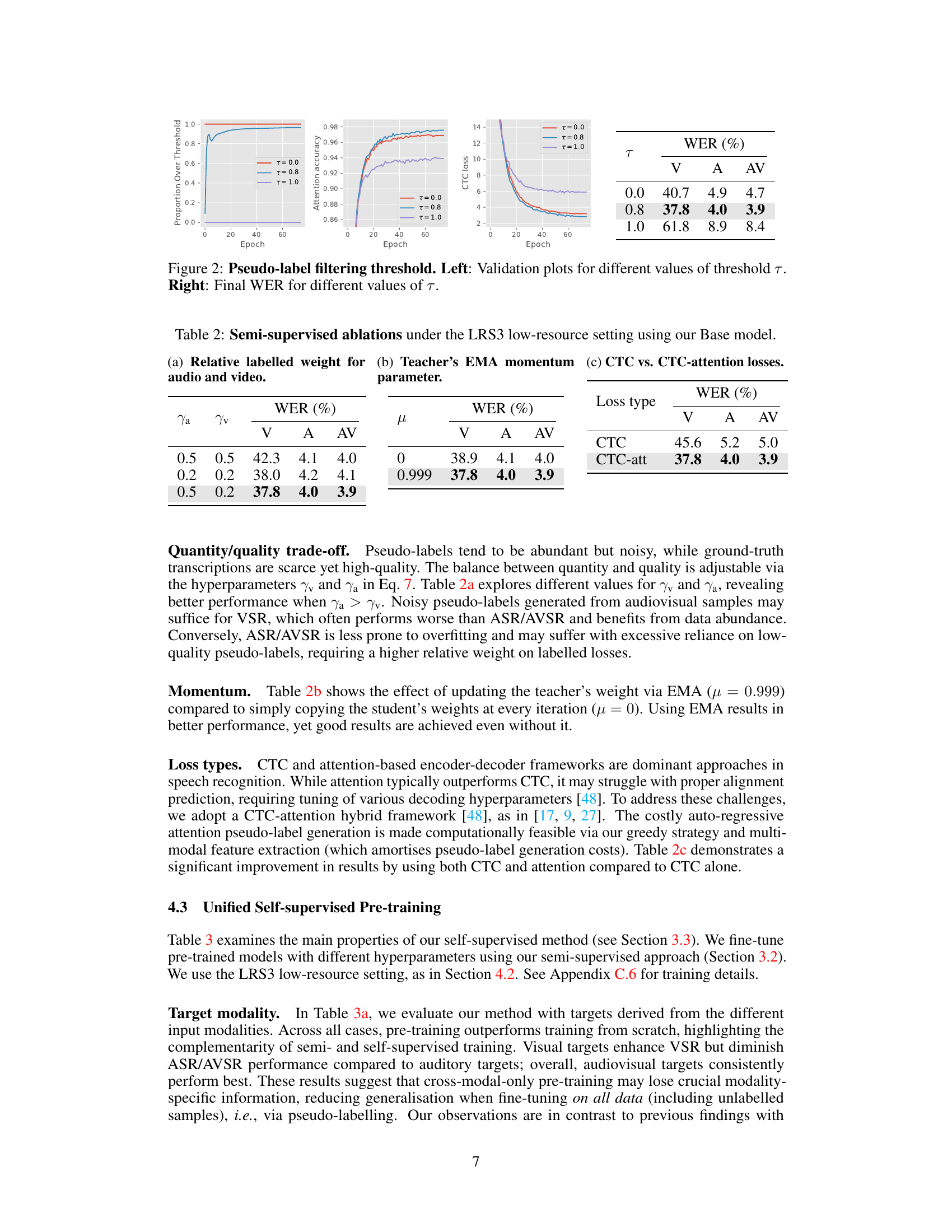

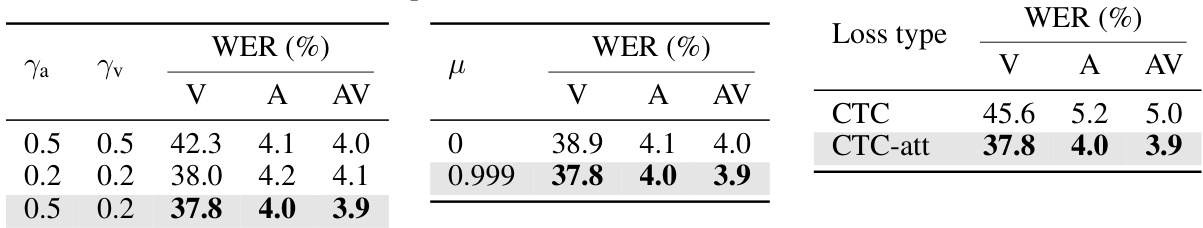

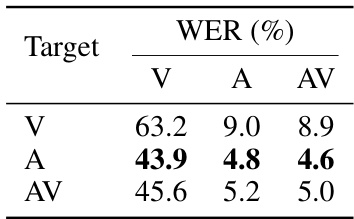

This table shows the results of ablating different components of the semi-supervised training framework proposed in the paper. It investigates the effects of varying the relative weight of labelled data for audio and video, the teacher’s EMA momentum parameter, and the type of loss function (CTC vs. CTC-attention) on the performance of the model in terms of Word Error Rate (WER) for visual (V), auditory (A), and audiovisual (AV) speech recognition tasks. The goal is to understand the contributions of each component to the overall performance and optimize the training process.

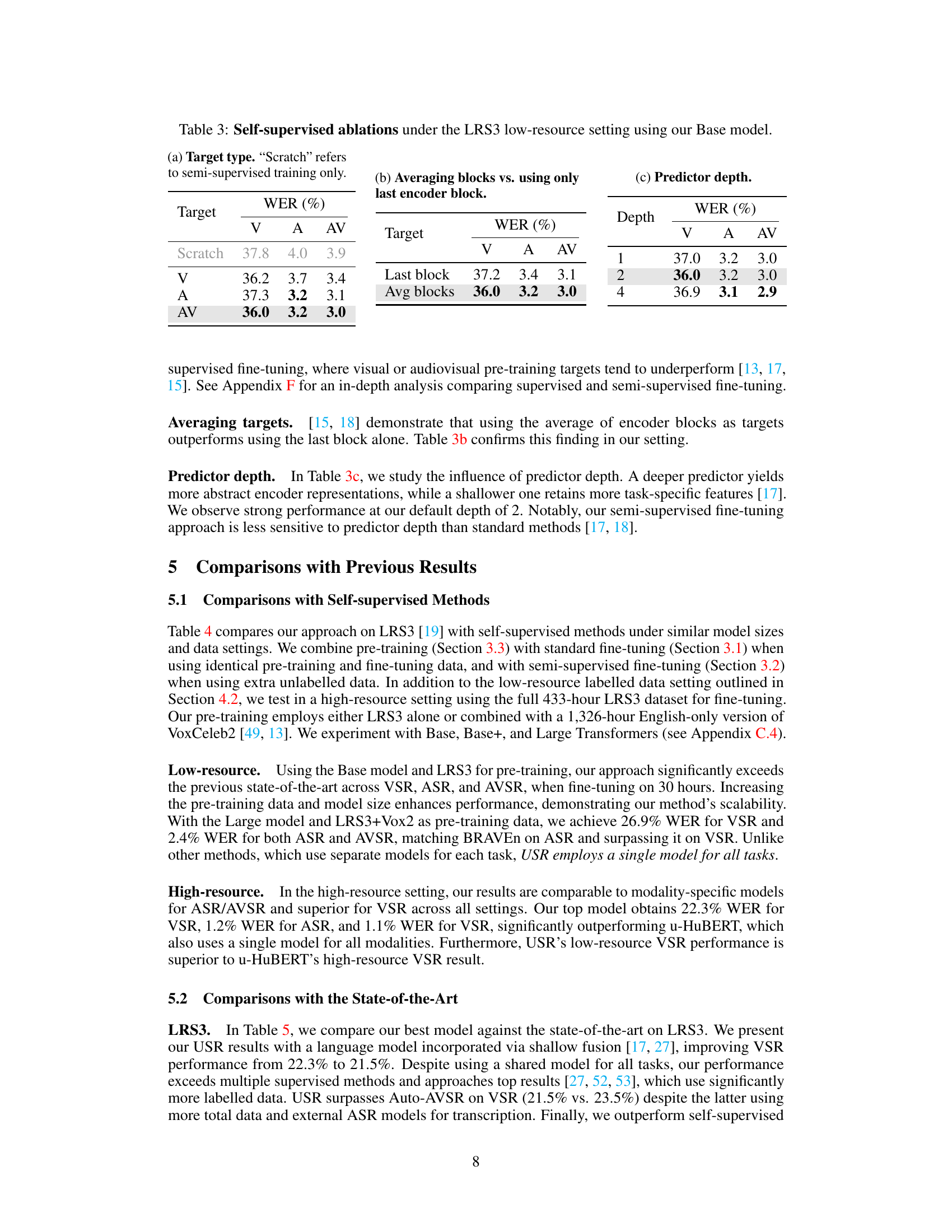

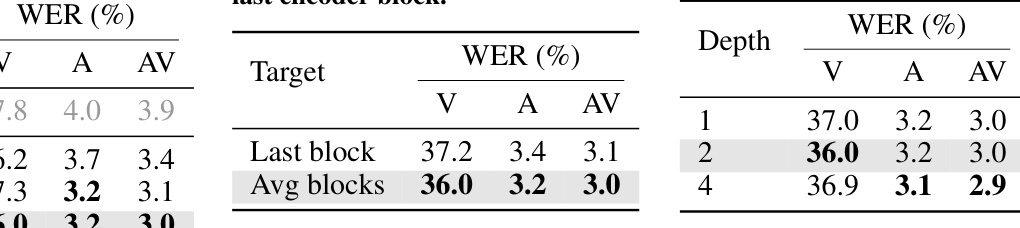

This table shows the ablation study on different components of the self-supervised pre-training method. It demonstrates that using audio-visual targets for pre-training yields the best performance. Averaging the outputs across all encoder blocks outperforms using only the last encoder block, and a deeper predictor improves performance slightly. The table also compares the results with only semi-supervised training, showing the complementary effect of self-supervised pre-training.

This table presents ablation studies on the self-supervised pre-training stage of the Unified Speech Recognition (USR) model. It investigates the impact of different target types (visual, auditory, audiovisual) during pre-training, comparing the use of averaging encoder block outputs versus only the last encoder block, and varying the depth of the predictor network. The results show how these choices affect the performance of the model on visual, auditory, and audiovisual speech recognition tasks.

This table compares the performance of the proposed USR method with several existing self-supervised methods on the LRS3 dataset for speech recognition. It shows the Word Error Rates (WER) for different modalities (visual, auditory, and audiovisual) under both low-resource and high-resource settings. The table also indicates whether the methods used shared parameters and the pre-training data used. The best and second-best results are highlighted for easier comparison.

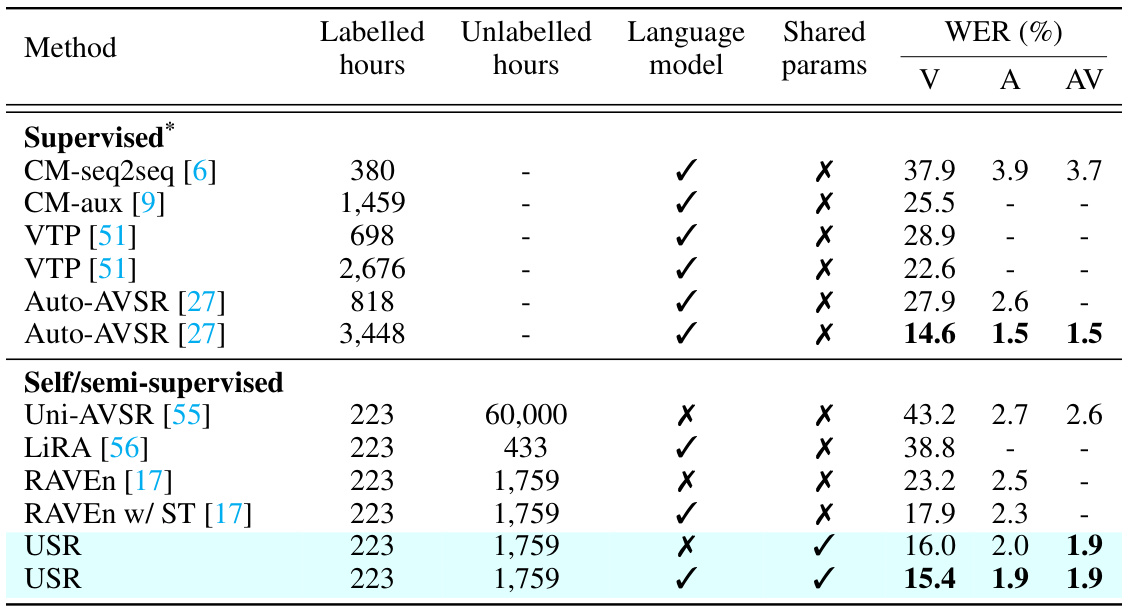

This table compares the proposed USR model’s performance with several state-of-the-art models on the LRS3 dataset. The comparison considers various methods, including both supervised and self-supervised approaches, highlighting the differences in labelled data usage, language model incorporation, and shared parameters. The results are presented in terms of Word Error Rates (WER) for visual (V), auditory (A), and audiovisual (AV) speech recognition tasks. The table demonstrates the USR’s competitive performance, particularly in achieving state-of-the-art results while using a single model for all three tasks.

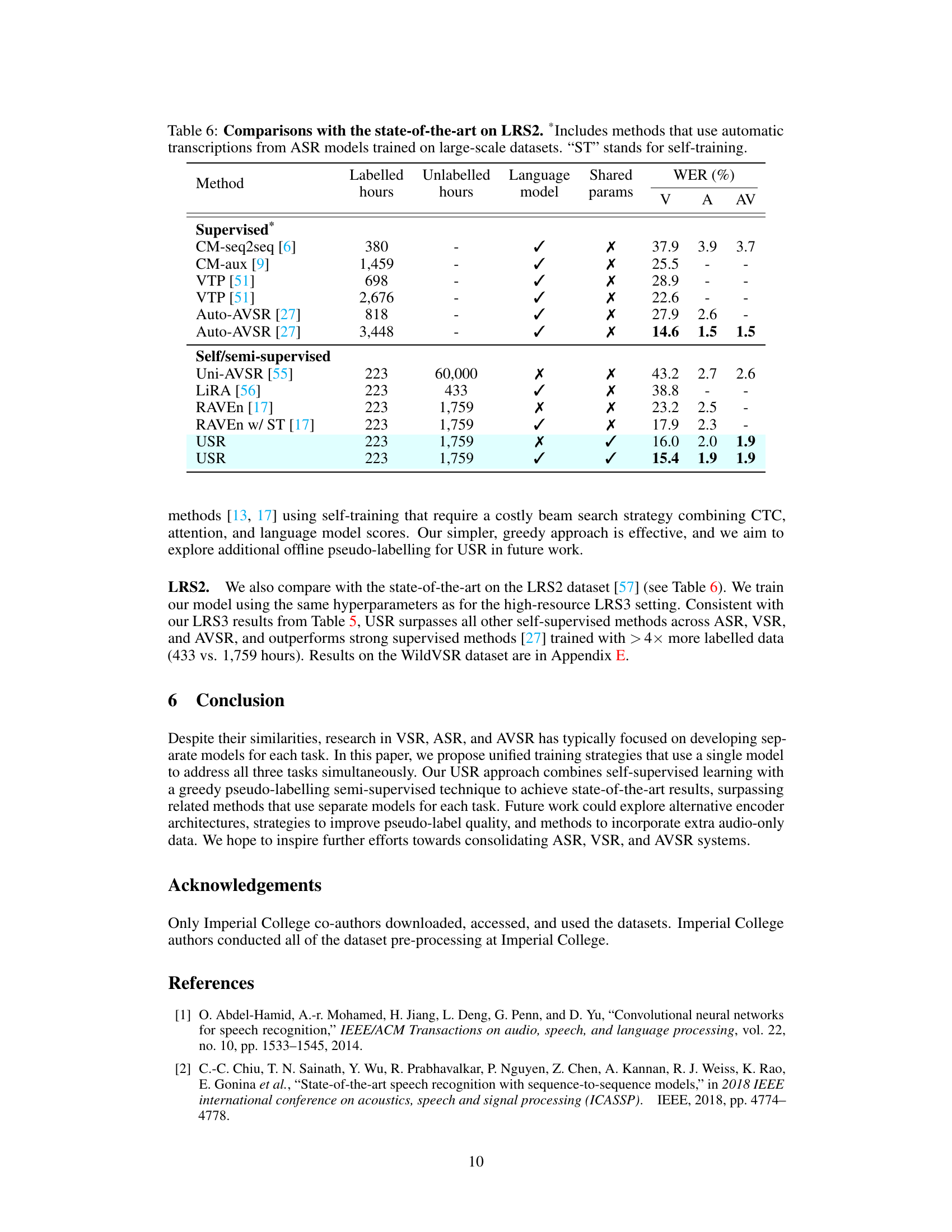

This table compares the proposed USR method with other state-of-the-art methods on the LRS2 dataset for audiovisual speech recognition. It shows the performance (WER) of various methods on visual, audio, and audiovisual speech recognition tasks, considering factors like the amount of labeled and unlabeled data used, whether language models were employed, and if the method used shared parameters or modality-specific ones. The table highlights the superior performance of the unified speech recognition (USR) approach, even when compared to methods that use a significantly higher amount of labeled data.

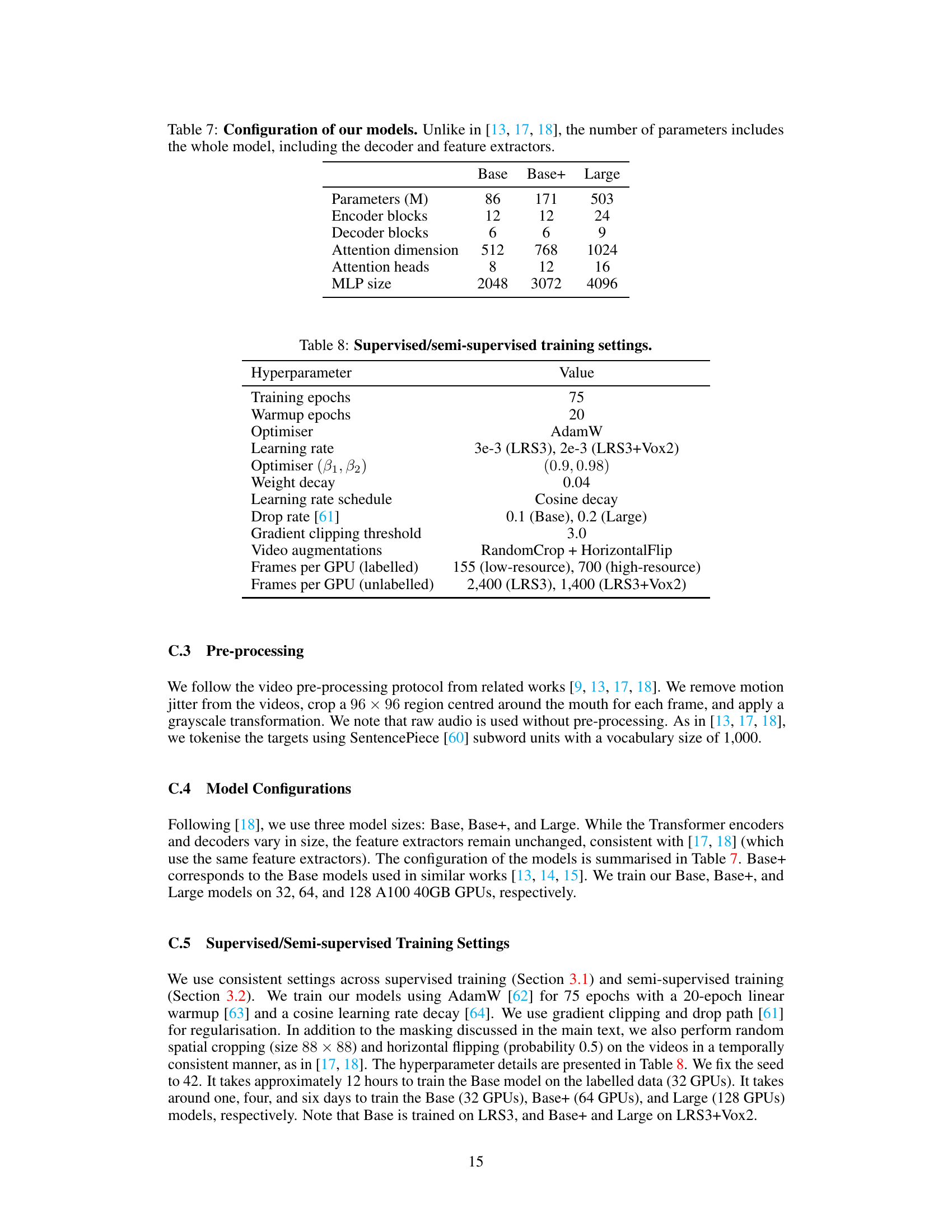

This table details the configurations of three different models used in the paper: Base, Base+, and Large. It shows the number of parameters (in millions), encoder blocks, decoder blocks, attention dimension, attention heads, and MLP size for each model. Note that unlike previous related works, the parameter count includes those of the decoder and feature extractors.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for both supervised and semi-supervised training in the paper. It includes details such as the number of training epochs, the optimizer used (AdamW), the learning rate, weight decay, and other settings specific to the training process. The values are given separately for low-resource and high-resource settings, as well as for different model sizes (Base and Large).

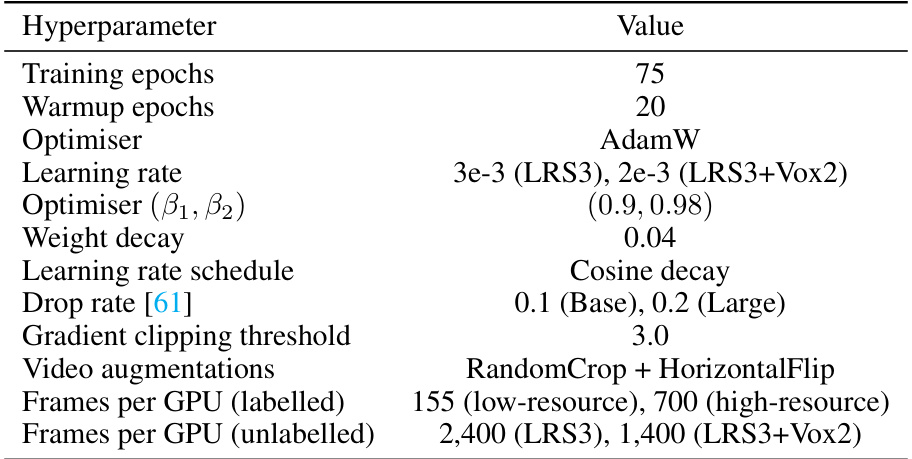

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the self-supervised pre-training stage of the Unified Speech Recognition (USR) model. The hyperparameters include details on the number of training epochs, the warmup epochs for the optimizer, the optimizer used (AdamW), the learning rate, the optimizer’s beta1 and beta2 parameters, the weight decay, the learning rate schedule, the drop rate (dropout), the gradient clipping threshold, the video augmentations applied, and the number of frames processed per GPU. Different values are provided for the LRS3 and LRS3+VoxCeleb2 datasets, and for Base, Base+, and Large model sizes.

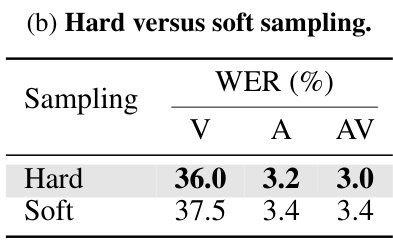

This table presents ablation studies on the semi-supervised training of the proposed Unified Speech Recognition (USR) model. It explores the impact of different filtering thresholds (τctc, τatt) on the CTC and attention losses, comparing various values to determine the optimal balance between precision and recall. Additionally, it investigates the difference between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ sampling methods for pseudo-label generation during semi-supervised training and assesses which method achieves better performance. The results are presented as Word Error Rates (WER) for visual (V), audio (A), and audiovisual (AV) modalities.

This table shows the results of ablations on semi-supervised training of the unified model under the LRS3 low-resource setting. It explores two main aspects: (a) the effect of different filtering thresholds (τctc and τatt) applied to CTC and attention probabilities during pseudo-label generation and (b) a comparison between a hard sampling method and a soft sampling method for pseudo-label generation. The WER (word error rate) for visual (V), auditory (A), and audiovisual (AV) modalities is reported to evaluate the performance impact of these hyperparameters.

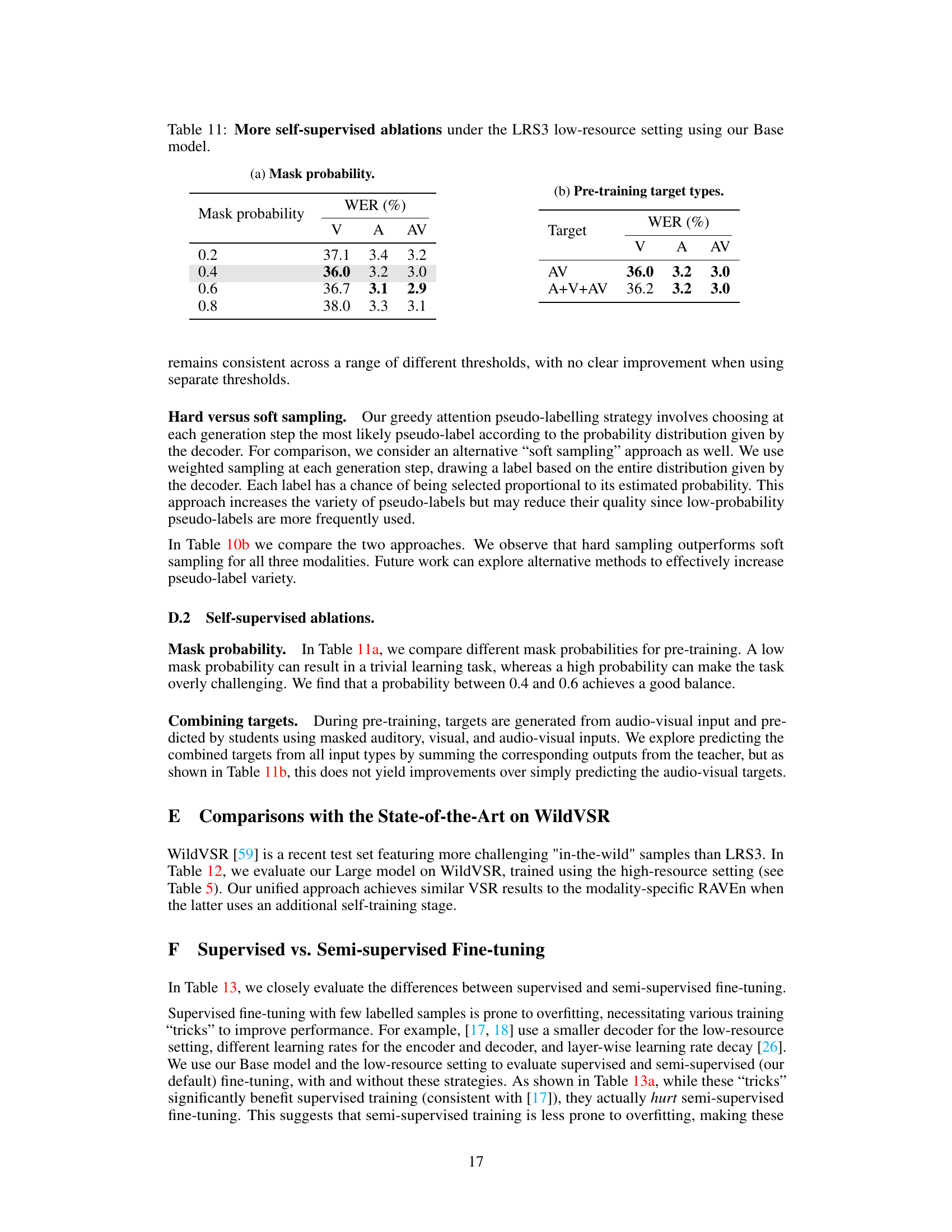

This table shows the ablation study of the self-supervised pre-training stage. The first part shows the effect of different mask probabilities on the final WER, while the second part demonstrates how the choice of pre-training target types (visual, auditory, or audiovisual) affects the performance of the model. The results highlight the impact of the hyperparameter and the choice of targets on the final accuracy of the model.

This table presents ablation studies on the self-supervised pre-training stage of the USR model. It investigates two hyperparameters: the mask probability during pre-training and the type of targets used for pre-training. The results show the impact of these hyperparameters on the final word error rates (WER) for Visual (V), Auditory (A), and Audiovisual (AV) speech recognition tasks.

This table compares the proposed USR method with other state-of-the-art methods on the LRS2 dataset for visual, audio, and audio-visual speech recognition. It shows the performance (WER) of various methods, indicating whether they used shared parameters, language models, and self-training techniques, along with the amount of labeled and unlabeled data used. The table highlights the superior performance of the USR method compared to other techniques.

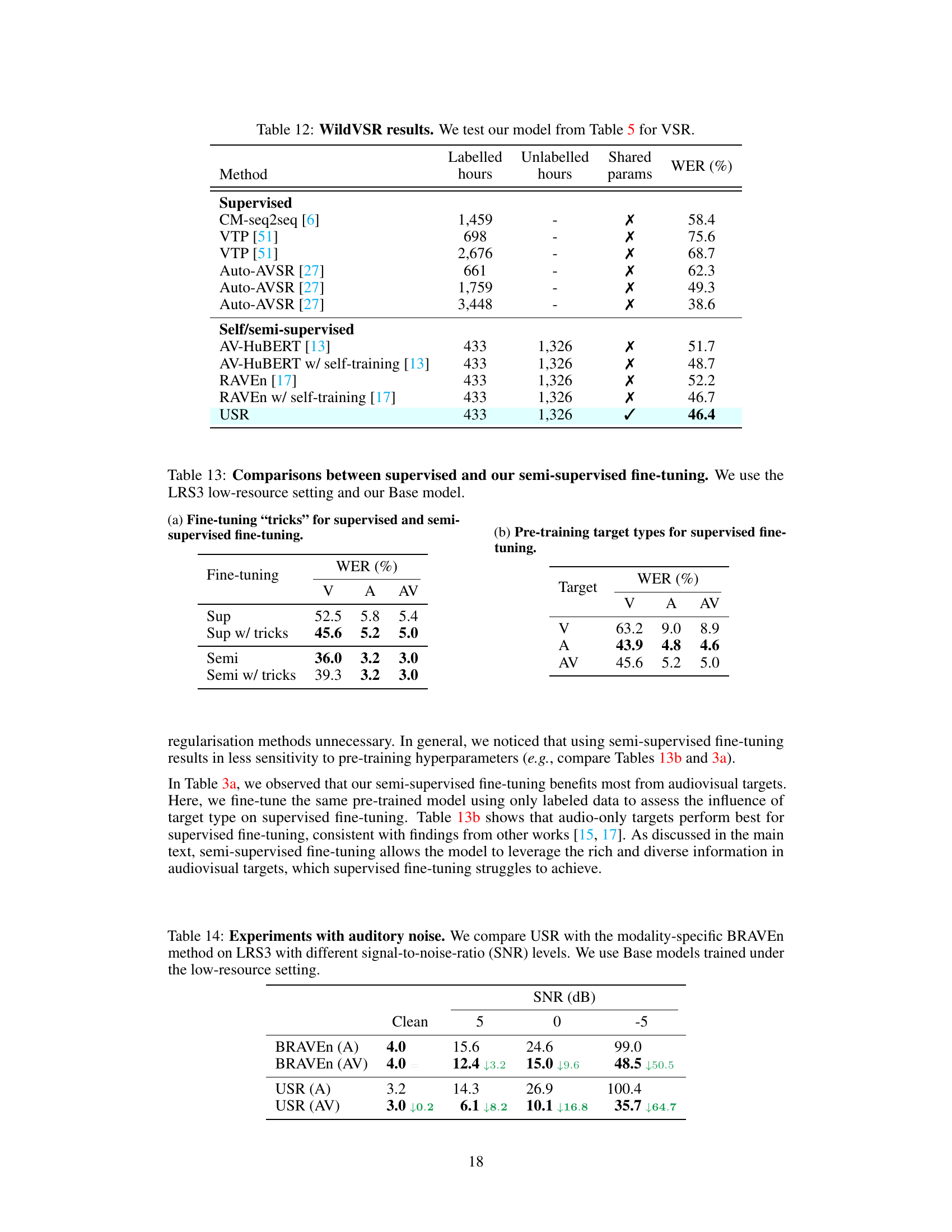

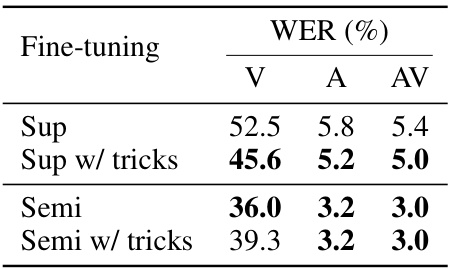

This table compares the performance of supervised and semi-supervised fine-tuning methods using the LRS3 low-resource dataset and the Base model. It shows Word Error Rates (WER) for Visual (V), Audio (A), and Audiovisual (AV) speech recognition across four different fine-tuning scenarios: supervised training, supervised training with additional training ’tricks’ to mitigate overfitting, semi-supervised training, and semi-supervised training with the same ’tricks’. The results highlight the effectiveness of the semi-supervised approach, especially when compared to the supervised approach with or without the use of overfitting mitigation techniques.

This table compares the performance of supervised and semi-supervised fine-tuning methods on the LRS3 low-resource dataset using the Base model. It shows the Word Error Rates (WER) for visual (V), audio (A), and audio-visual (AV) speech recognition tasks under different fine-tuning approaches. Specifically, it contrasts supervised fine-tuning with and without additional training techniques (referred to as ’tricks’) against semi-supervised fine-tuning with and without those same techniques. The pre-training target types (V, A, or AV) used for supervised fine-tuning are also shown.

This table compares the performance of the Unified Speech Recognition (USR) model and the BRAVEn model on the LRS3 dataset under various levels of auditory noise. It shows Word Error Rates (WERs) for both auditory-only (A) and audio-visual (AV) speech recognition for different signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs), including a clean condition. The table allows for comparison of how the performance of each model changes with different levels of noise.

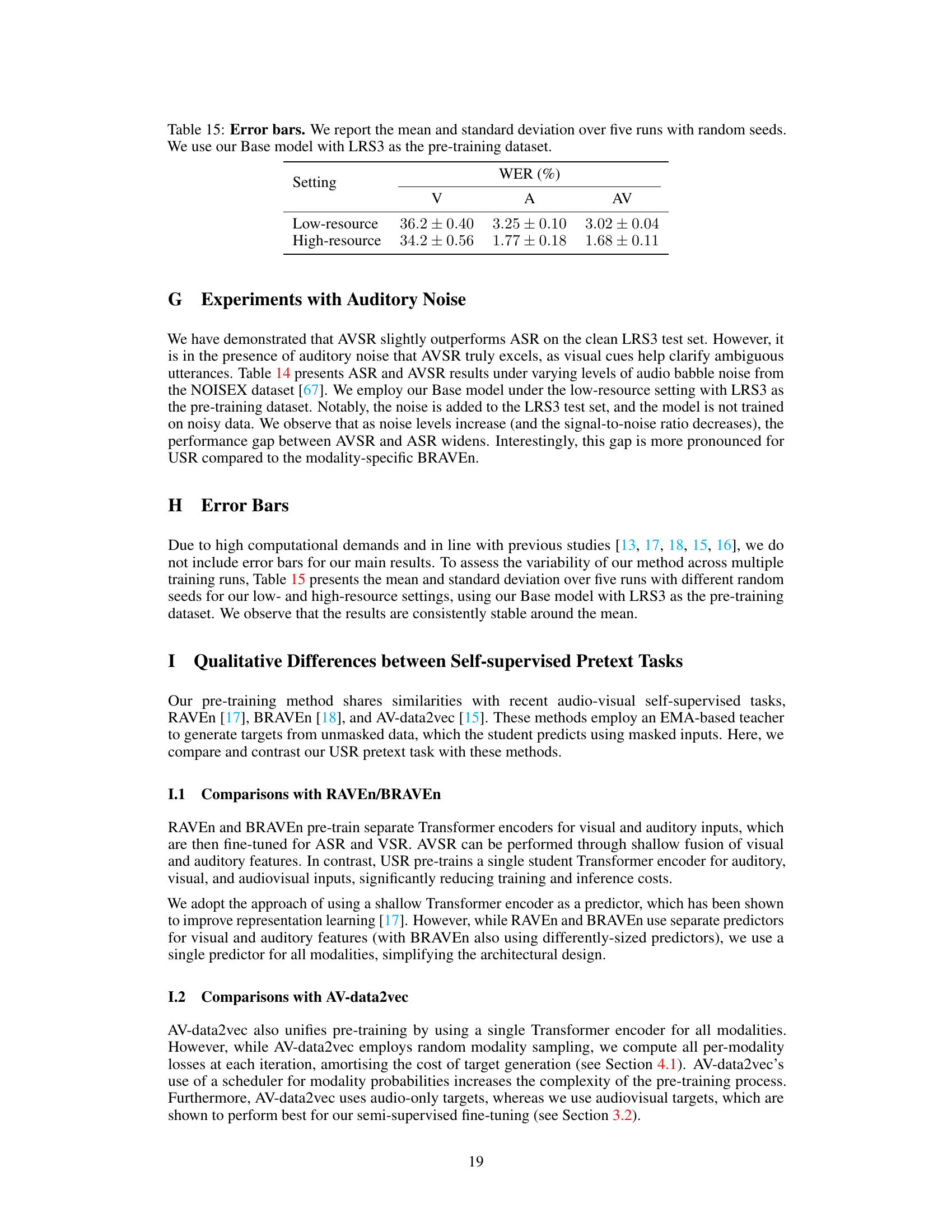

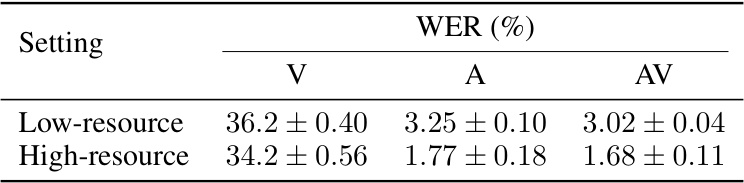

This table shows the mean and standard deviation of Word Error Rates (WER) for visual (V), audio (A), and audiovisual (AV) speech recognition tasks across five independent runs with different random seeds. The results are reported for both low-resource and high-resource data settings, using the ‘Base’ model and LRS3 dataset for pre-training. The error bars represent the variability in the model’s performance across multiple runs, giving an indication of the model’s stability.

This table compares the performance of the proposed USR method against the AV-CPL method [36] on the LRS3 dataset under both low-resource and high-resource conditions. It specifically shows the Word Error Rate (WER) achieved by each method for visual (V), auditory (A), and audiovisual (AV) speech recognition. The results highlight the significant performance improvement of USR over AV-CPL, especially in the low-resource setting.

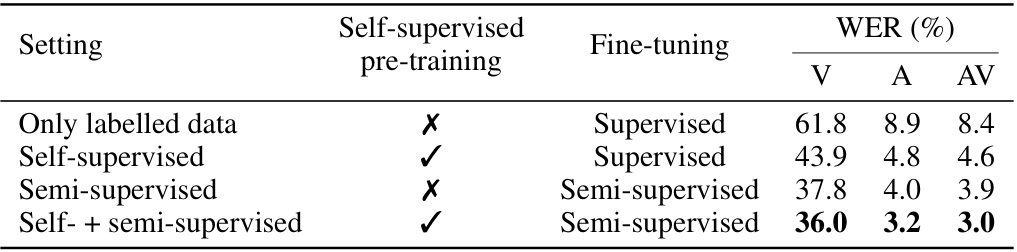

This table summarizes the results of four different training approaches on the LRS3 low-resource dataset using the base model. The four approaches compared are: only supervised training, self-supervised pre-training followed by supervised fine-tuning, semi-supervised training, and a combination of self-supervised pre-training and semi-supervised fine-tuning. The table presents word error rates (WER) for visual (V), auditory (A), and audiovisual (AV) speech recognition tasks for each approach.

This table showcases examples from the LRS3 test set where the Large model (trained with high-resource settings using LRS3 and VoxCeleb2) made errors in transcription. The table compares the ground truth transcription with the ASR, VSR, and AVSR outputs for each example, highlighting the types of errors made. The examples illustrate instances where the model struggled with phonetically similar sounds or where visual information could help disambiguate.

Full paper#