↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current language models, while impressive in many tasks, lack the human ability to efficiently skip steps during complex reasoning. This is because they don’t inherently possess the motivation to optimize reasoning steps like humans do. This limitation hinders their ability to generalize and solve problems with increased efficiency. The researchers aimed to investigate whether this human-like step-skipping ability can be learned by language models.

The researchers introduced a controlled training framework to encourage models to generate shorter, accurate reasoning paths. They iteratively refined models by selectively incorporating successful step-skipping paths in training data. Experiments across several datasets demonstrated that the models successfully developed the ability to skip steps. Importantly, the step-skipping behavior improved efficiency without sacrificing accuracy and even enhanced generalization capabilities. The findings provide fresh perspectives on developing human-like cognitive abilities in AI models and offer new avenues for advancing generalization abilities in language model reasoning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it explores a novel aspect of AI—the ability of language models to mimic human-like step-skipping in reasoning. This is significant because it reveals new possibilities for enhancing AI efficiency and generalization capabilities. The findings challenge existing assumptions about model behavior and open avenues for research into more human-like cognitive abilities in AI.

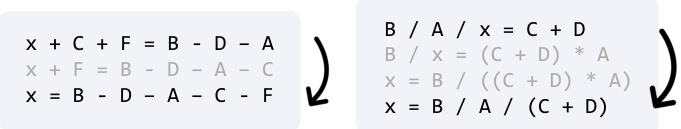

Visual Insights#

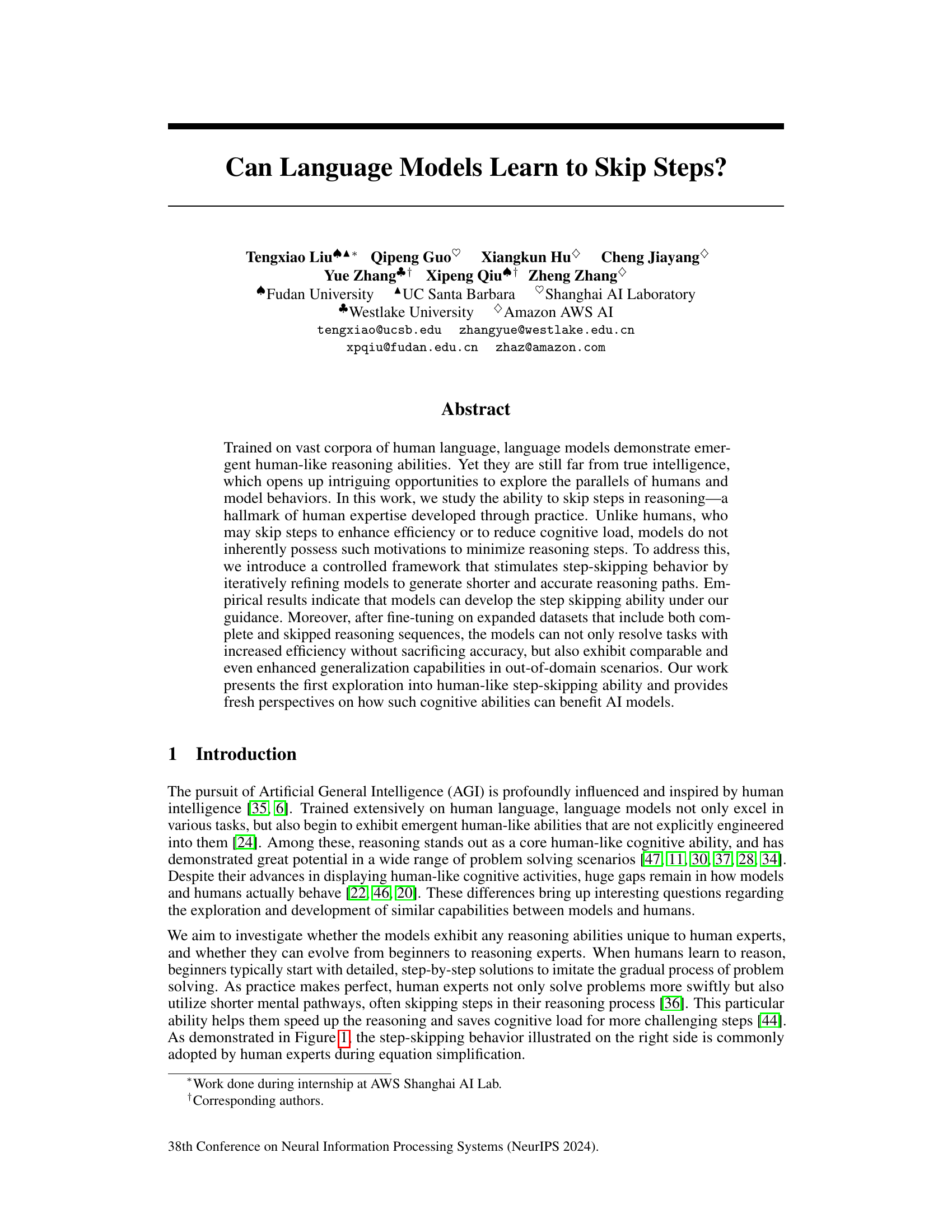

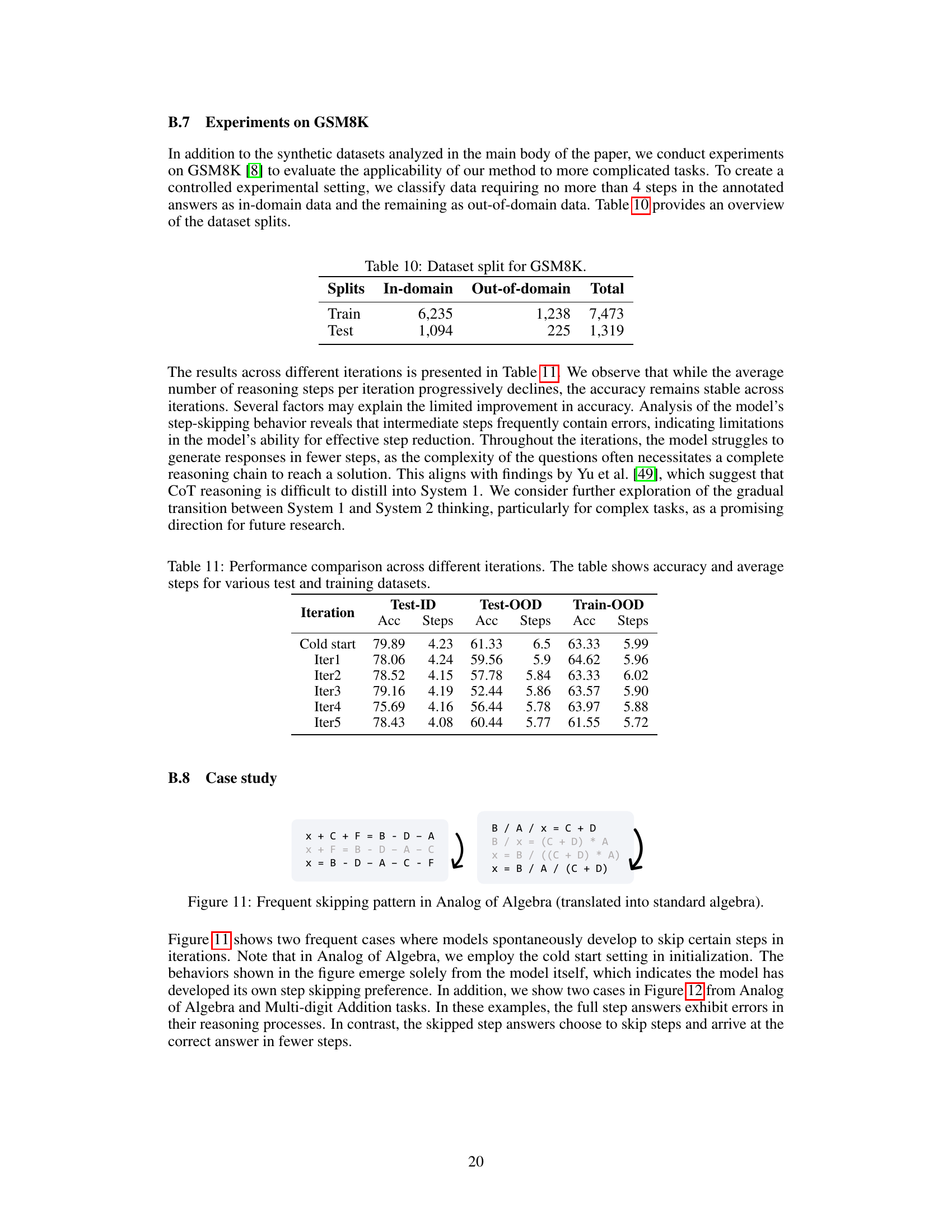

This figure illustrates the concept of step skipping in solving an equation. The left side shows a step-by-step solution with four steps. The right side shows the same equation solved in two steps, skipping two intermediate steps. This highlights human expert behavior where practice enables more efficient problem-solving by omitting intermediate but obvious steps.

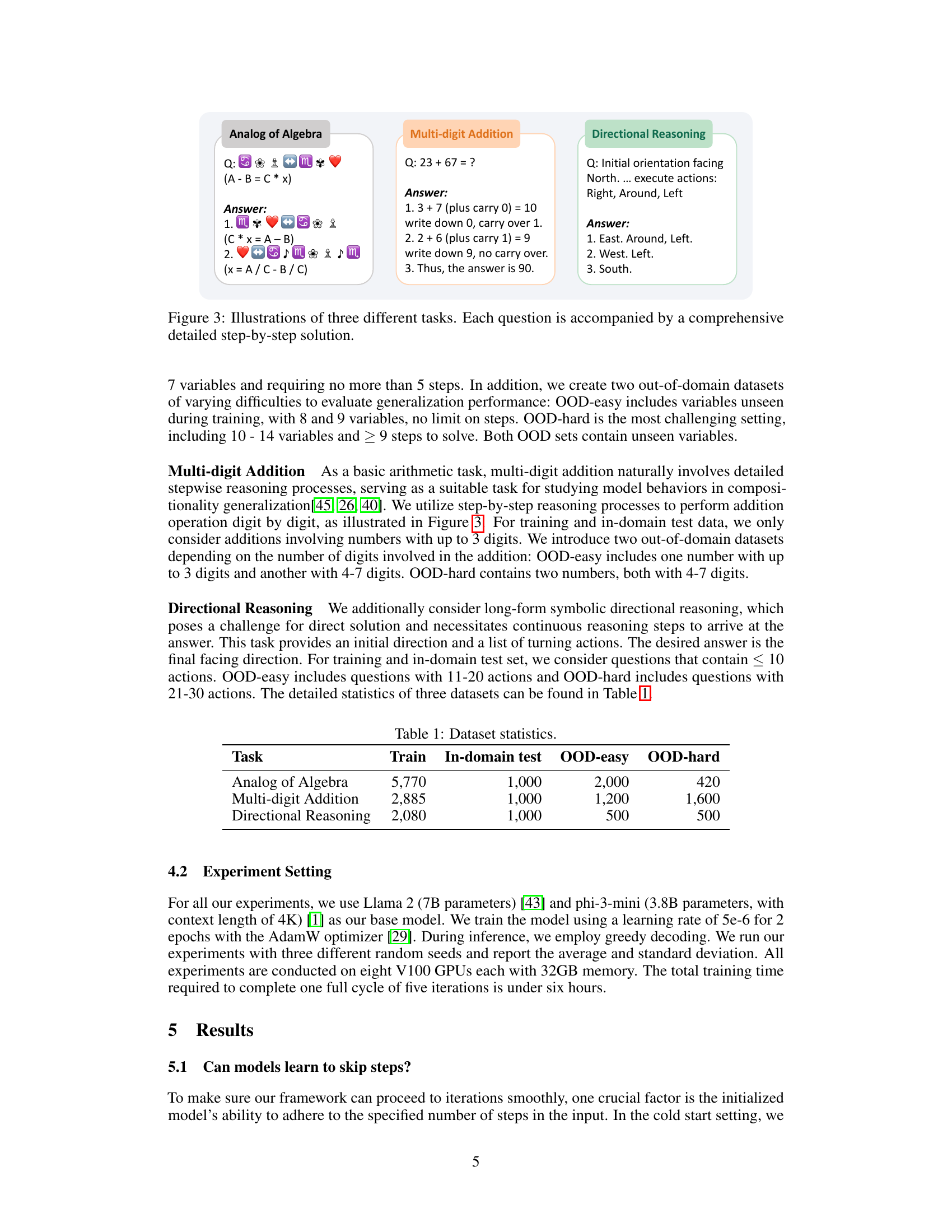

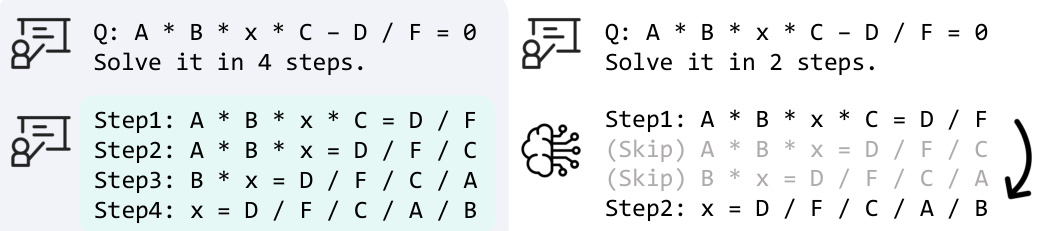

This table presents the number of data samples used for training, in-domain testing, out-of-domain easy testing, and out-of-domain hard testing for each of the three reasoning tasks: Analog of Algebra, Multi-digit Addition, and Directional Reasoning. The sizes reflect the varying difficulty levels incorporated into the experimental design. The ‘in-domain’ sets are used for evaluating the model’s ability to solve problems similar to those seen during training, while the ‘out-of-domain’ sets, categorized as ’easy’ and ‘hard’, assess its generalization capability on unseen and more complex problems, respectively.

In-depth insights#

Step-Skipping Models#

Step-skipping models represent a significant advancement in AI, moving beyond the traditional, meticulous approach to problem-solving. By mimicking human expertise, these models learn to identify and omit unnecessary steps in their reasoning processes, leading to increased efficiency and reduced computational costs. This is achieved through iterative training, where models are initially trained to solve problems comprehensively, then progressively refined to generate shorter, yet accurate, solutions. The key lies in carefully curating training data that includes both complete and skipped reasoning sequences, allowing models to learn the optimal balance between conciseness and correctness. The success of step-skipping models hinges on effective training frameworks that guide this iterative refinement, ensuring that accuracy isn’t sacrificed for efficiency. While still under development, the ability of these models to generalize to new, unseen problems presents exciting possibilities, opening avenues for exploring human-like cognitive abilities within AI. Furthermore, this approach offers a fresh perspective on AI generalization, potentially improving how models adapt and solve complex problems in more efficient and human-like ways.

Iterative Refinement#

Iterative refinement, in the context of a research paper, likely refers to a process of repeatedly improving a model or system through successive cycles. Each cycle involves evaluating the current iteration, identifying weaknesses or areas for improvement, and then making adjustments. This iterative approach is crucial for achieving high-quality results, especially in complex tasks. The key is the feedback loop: the process of evaluation informs the next iteration, leading to continual refinement and better performance. This could manifest in various ways, such as fine-tuning model parameters based on performance metrics on a validation set, modifying training data to correct biases, or adjusting algorithm parameters to optimize efficiency. The iterative nature highlights a learning process: The system (model or algorithm) learns and adapts at each stage, ultimately converging towards a better solution. This method allows for incremental progress, reducing the risk of making large, potentially disruptive changes. A critical aspect is the stopping criterion: Determining when the process has converged sufficiently is crucial and should be clearly defined in the paper. This could be based on achieving a specific performance level, diminishing returns in improvements, or reaching a computational budget limit.

Generalization Gains#

The concept of “Generalization Gains” in the context of a machine learning model’s ability to perform well on unseen data is crucial. A model exhibiting strong generalization capabilities successfully transfers knowledge learned from its training data to novel, unseen inputs. High generalization ability is a hallmark of robust and effective models. In this context, “Generalization Gains” likely refers to improvements in a model’s performance on out-of-distribution (OOD) data, meaning data that significantly differs from the training data. This might be achieved through techniques like data augmentation or by training the model on a wide variety of data to make it more adaptable. The paper likely explores how techniques designed to encourage step-skipping in reasoning improve this generalization ability. The key question is whether encouraging the model to find more efficient reasoning paths, thus reducing cognitive load, inadvertently leads to better generalization. This is because efficient reasoning might involve extracting more abstract and generalizable features from the data, thereby improving performance on unseen inputs. The results section would showcase that the model, after being trained to skip steps, demonstrates improved performance on OOD tasks, providing strong evidence of generalization gains. Quantifying these gains is crucial, and may involve metrics like accuracy or efficiency on both in-distribution and out-of-distribution tasks.

Limitations & Future#

This research makes a significant contribution by exploring the ability of language models to emulate human-like step-skipping in reasoning. A key limitation is the reliance on controlled training environments to induce this behavior, which may not fully reflect the complexities of real-world reasoning. The study also focuses on specific reasoning tasks, leaving the generalizability to diverse and more complex problem domains unclear. Future research could address these limitations by investigating methods for intrinsically motivating step-skipping in models, perhaps through reward mechanisms that prioritize efficiency. Expanding the scope to broader reasoning tasks, including those with ambiguous steps or requiring more nuanced cognitive abilities would strengthen the findings. Exploring potential biases inherent in the generated step-skipping patterns and investigating techniques to mitigate such biases is crucial. Finally, evaluating the impact of step-skipping on real-world applications, such as improved efficiency and resource usage in problem-solving systems, would provide valuable insights into the practical implications of this research.

Human-like Reasoning#

The concept of “Human-like Reasoning” in AI research is multifaceted, focusing on the development of AI systems capable of mirroring human cognitive processes. This involves not just achieving high accuracy on reasoning tasks but also understanding the underlying mechanisms and strategies humans employ. Key aspects include the ability to handle incomplete information, to reason with uncertainty, and to adapt strategies based on context or experience. A critical element is the exploration of step-skipping abilities – the capacity to move beyond meticulous step-by-step processes to reach conclusions more efficiently, a hallmark of human expertise. This efficiency is not merely about speed but also about cognitive load management, suggesting that future AI systems must balance speed and resource allocation. Furthermore, true human-like reasoning involves integrating various cognitive skills like planning, task decomposition, and self-correction. The challenge lies in moving beyond the current capabilities of large language models (LLMs) which often exhibit biases or shortcuts, failing to emulate the robustness and adaptability of human reasoning. Ultimately, the development of robust human-like reasoning will require a deeper understanding of human cognition and the design of AI architectures that can capture its complexity and nuance.

More visual insights#

More on figures

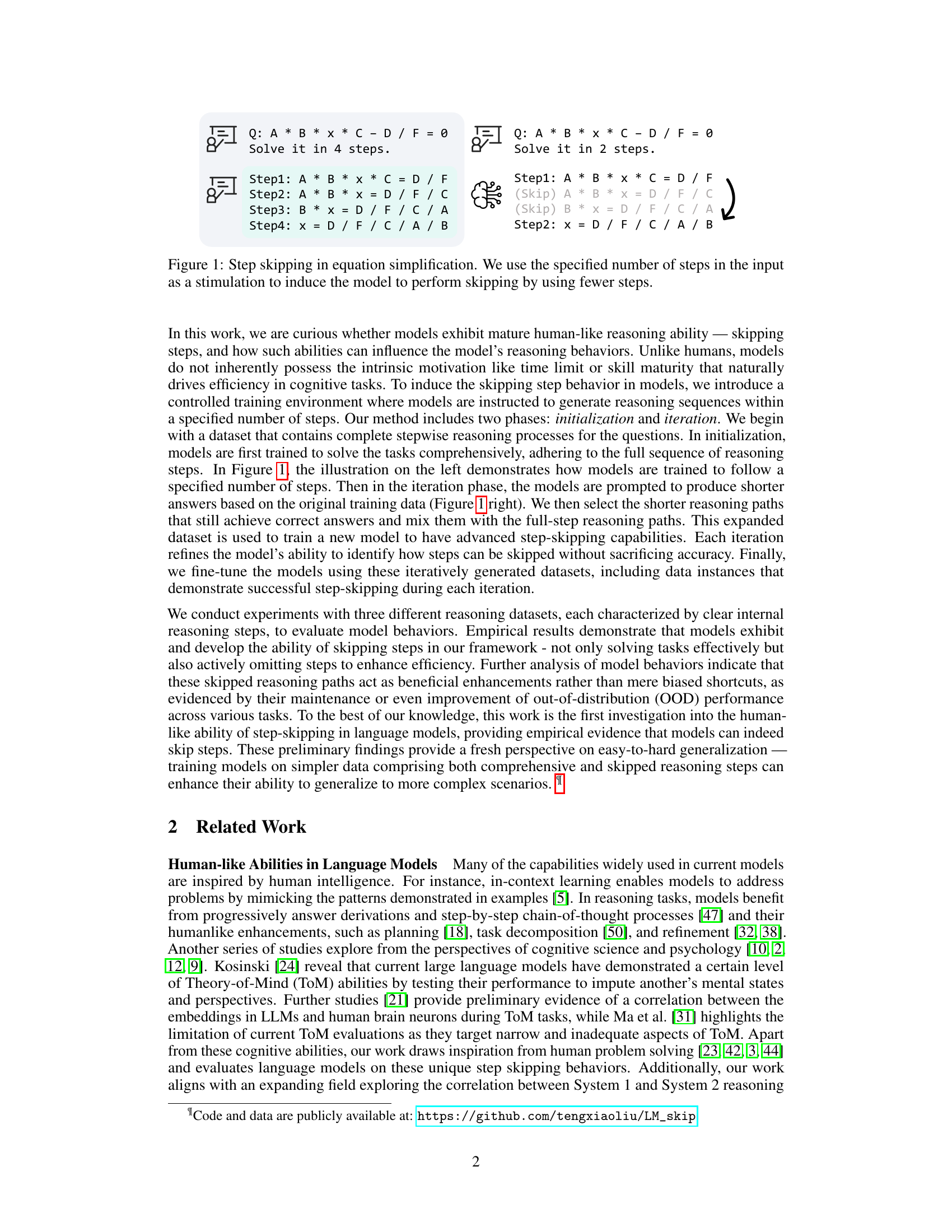

This figure illustrates the overall framework of the proposed method for inducing step-skipping behavior in language models. It consists of two main phases: initialization and iteration. Initialization: A standard model is initially trained on a dataset (Dinit) to solve problems following a specified number of steps. This establishes a baseline reasoning ability. Iteration: The model is iteratively refined. In each iteration, the model is prompted to solve problems using fewer steps than the initial specified number. Correct shorter solutions are added to the training dataset, creating a mixed dataset (Di) containing both full and shorter reasoning sequences. A new standard model (Mi) is then trained on this updated dataset. This process repeats until the model consistently generates efficient, step-skipping reasoning paths. The model’s step-skipping ability is evaluated after each iteration using the standard fine-tuning and inference.

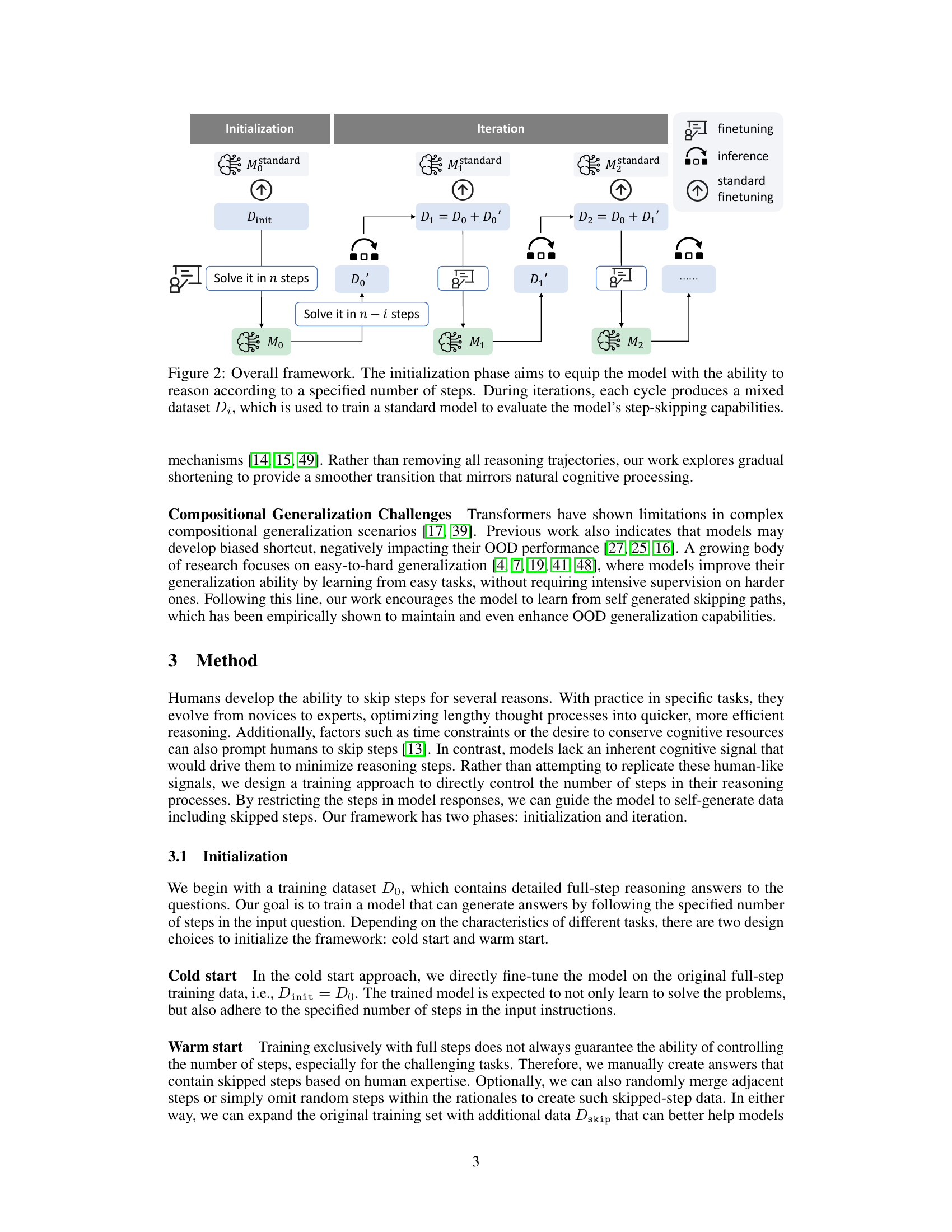

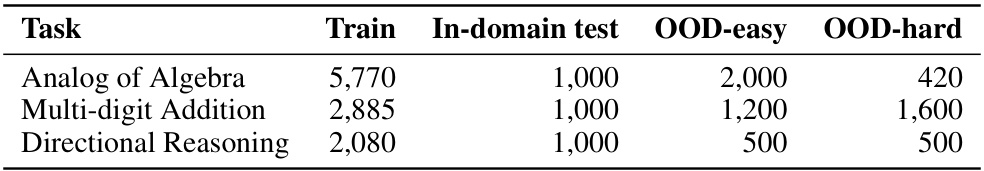

This figure provides example questions and detailed step-by-step solutions for three different reasoning tasks used in the paper’s experiments: Analog of Algebra, Multi-digit Addition, and Directional Reasoning. Each task is designed to have clearly defined intermediate steps, making it suitable for studying the model’s ability to skip steps during reasoning.

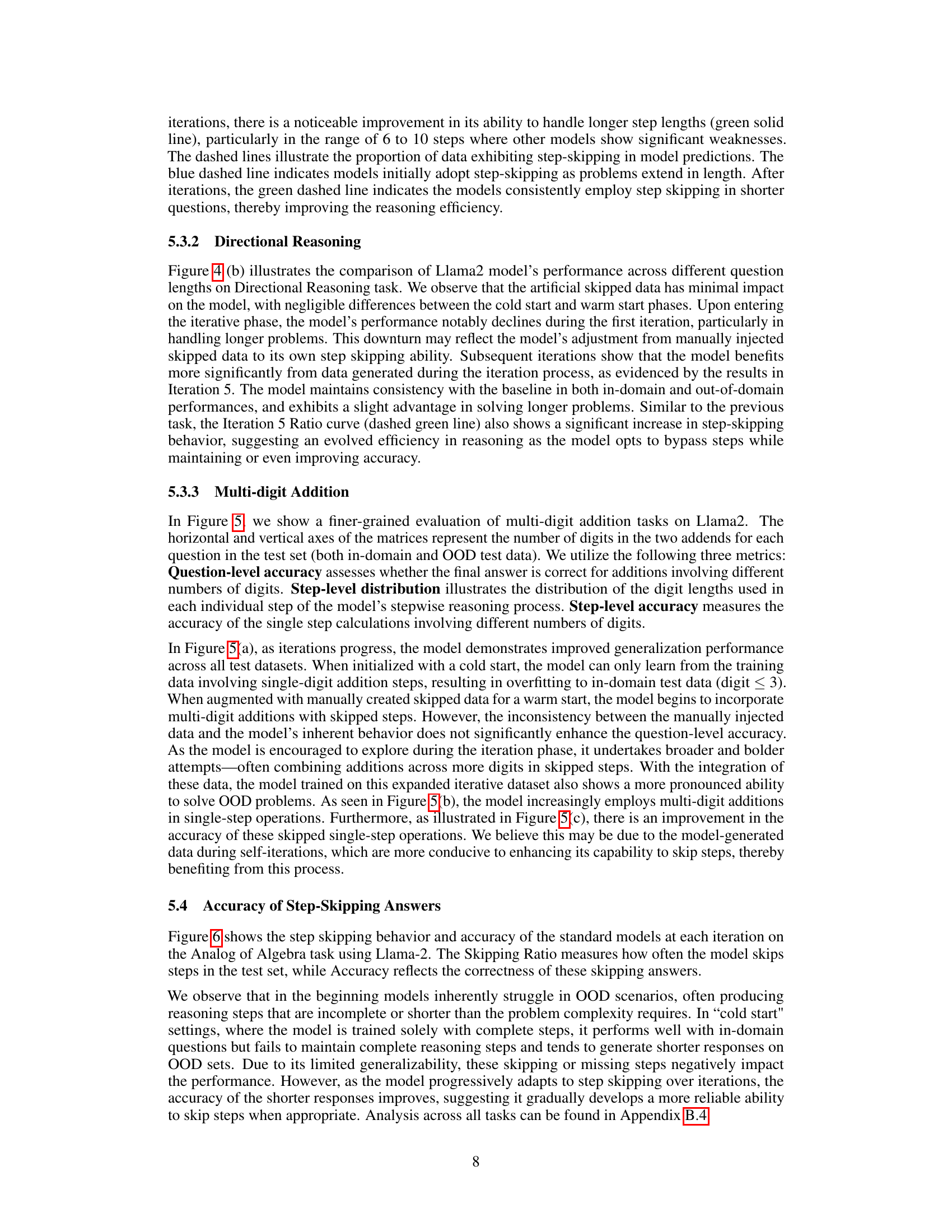

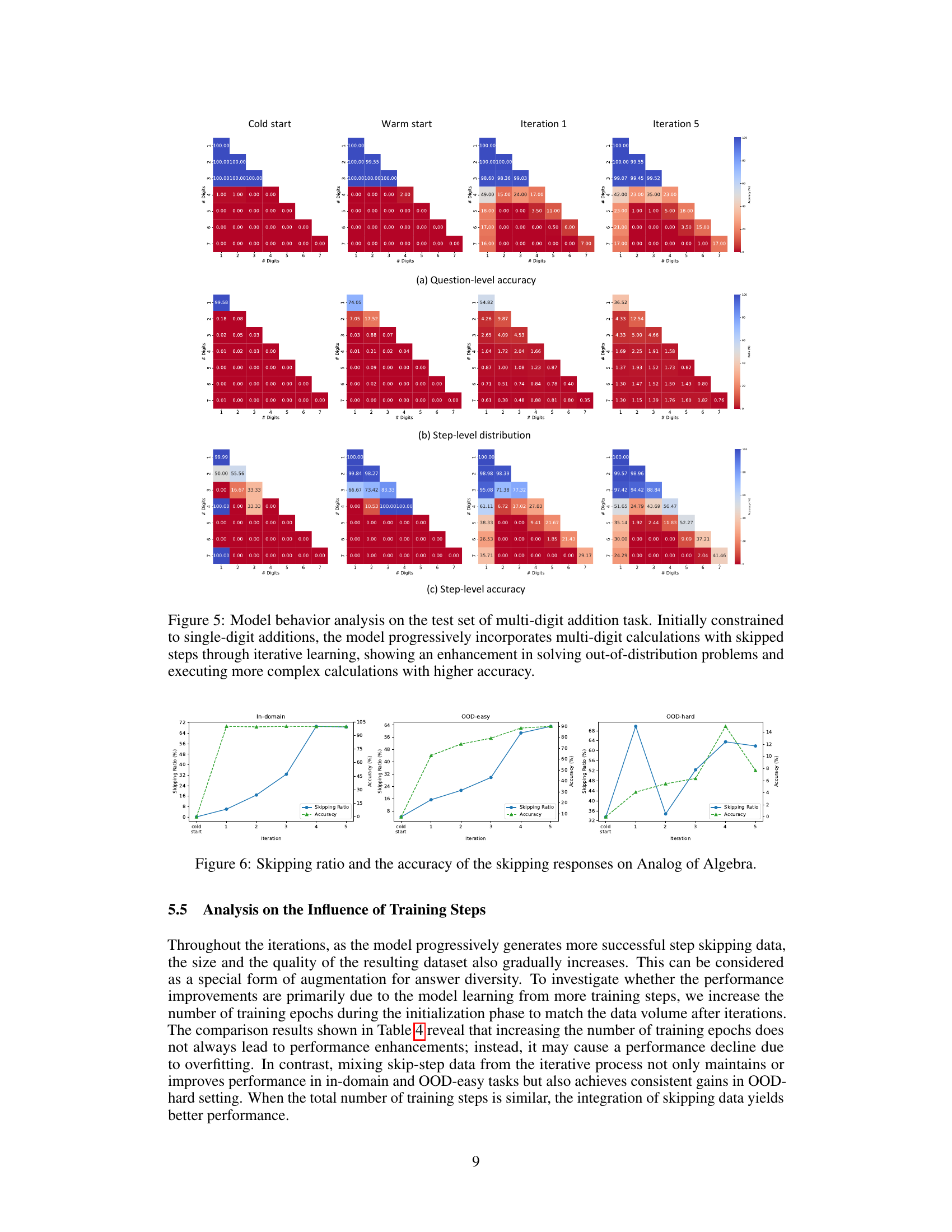

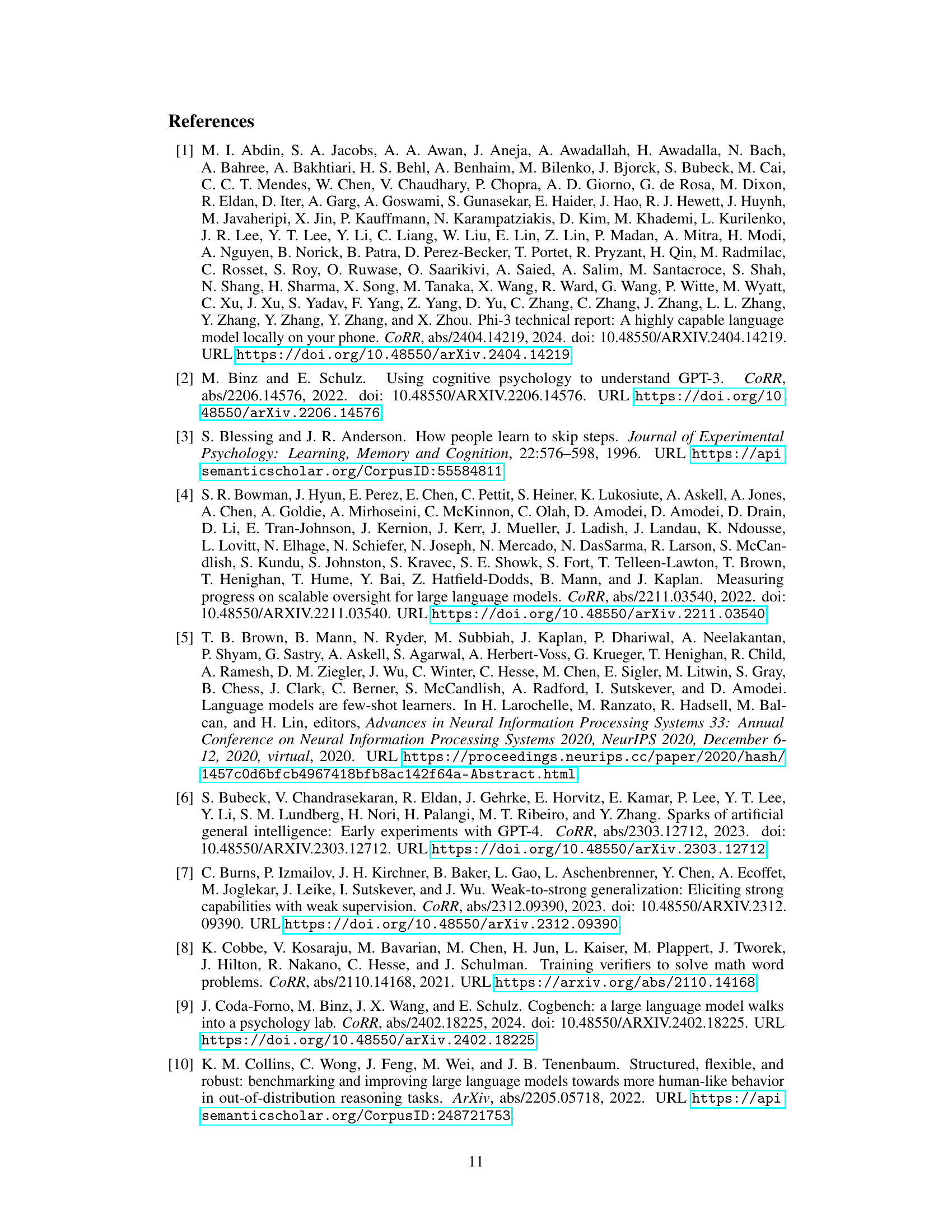

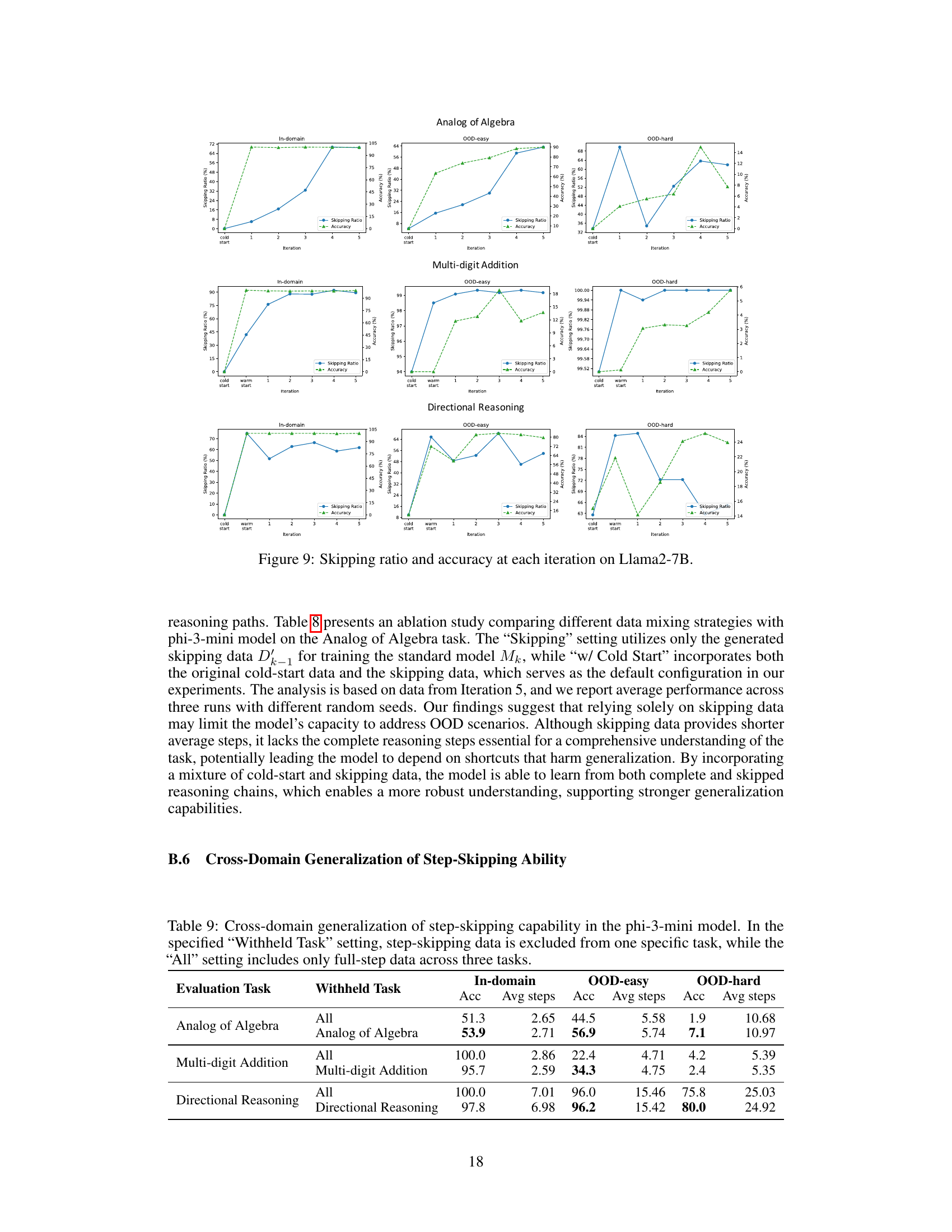

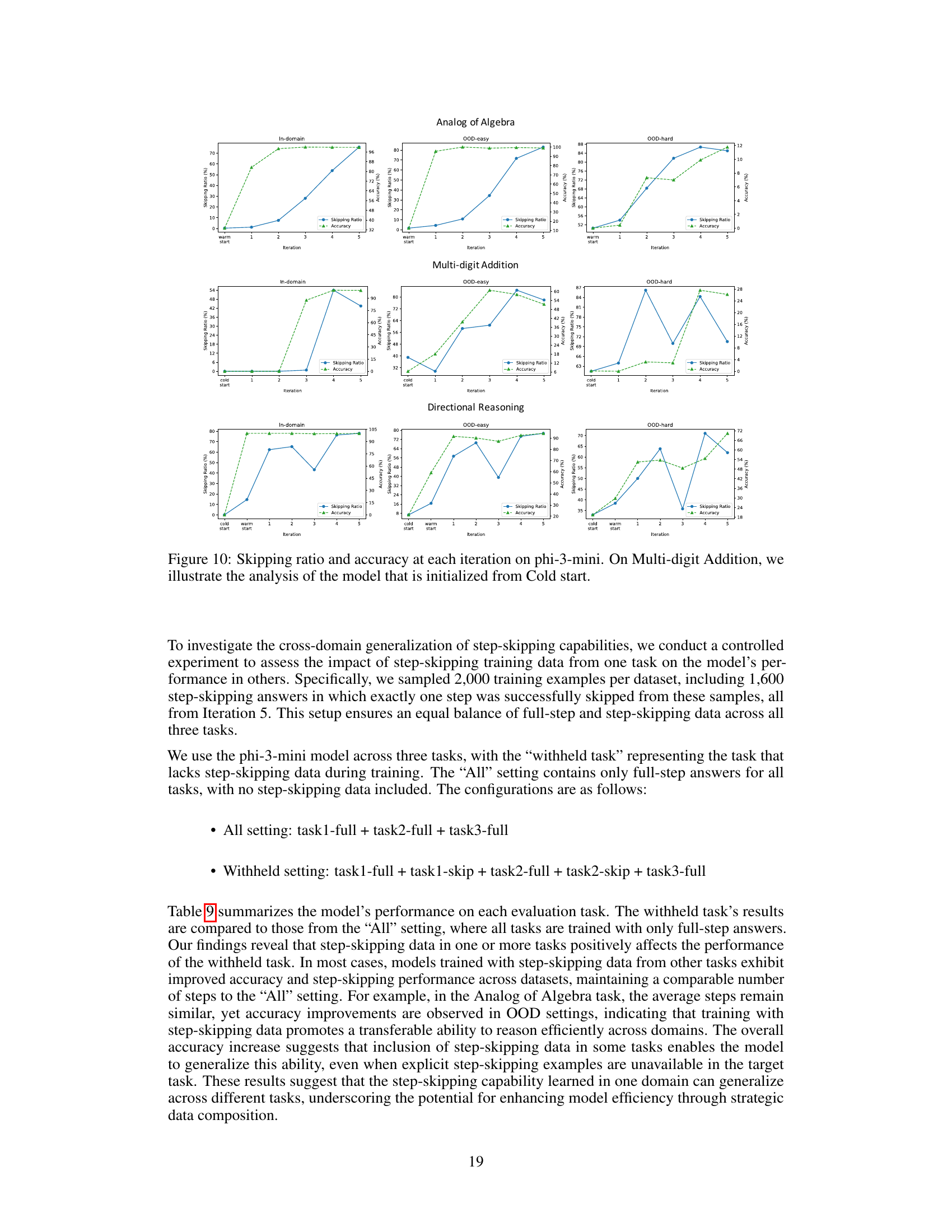

This figure compares the performance of different models (Llama2 and phi-3-mini) across various iterations of training. The models are evaluated on in-domain and out-of-distribution (OOD) datasets with varying lengths and complexities. The plots show that while the models achieve almost perfect accuracy on the in-domain datasets, they perform differently on OOD data; the accuracy decreases as the length and complexity increase. The comparison highlights the impact of incorporating skipped reasoning steps on the models’ ability to generalize to more complex scenarios.

This figure shows three different reasoning tasks used in the paper’s experiments: Analog of Algebra, Multi-digit Addition, and Directional Reasoning. Each task is illustrated with an example question and its corresponding step-by-step solution. The purpose of showing these examples is to highlight the types of problems used to evaluate the models’ ability to skip steps in their reasoning process and to clearly define the intermediate steps required for solving each problem. The detailed, step-by-step solutions provide the baseline against which the model’s ability to generate shorter, accurate solutions is measured.

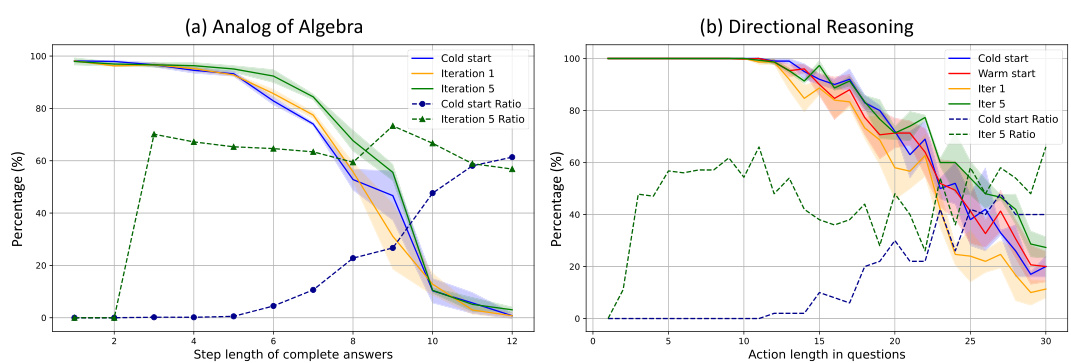

This figure displays the performance comparison of models across different phases in relation to the question length and complexity. The x-axis likely represents the length of questions (or number of steps), and the y-axis likely shows accuracy and/or the number of steps used in the model’s reasoning process. The lines likely represent different training phases (e.g., initial training, iterations). The figure shows that all models perform near perfectly on in-domain data (shorter questions), but their performance diverges significantly on out-of-domain (OOD) data (longer questions). This demonstrates the impact of the step-skipping training on the model’s ability to generalize to more complex problems.

This figure presents a comparison of model performance across different phases of training, specifically focusing on how question length and complexity affect accuracy. The in-domain data shows near-perfect accuracy for all models, regardless of the training phase. However, performance on out-of-distribution (OOD) data, particularly the lengthy OOD data, shows significant differences among various models and training phases. This illustrates how the models’ ability to generalize to complex and less-structured problems varies based on the training method and iterative step-skipping process.

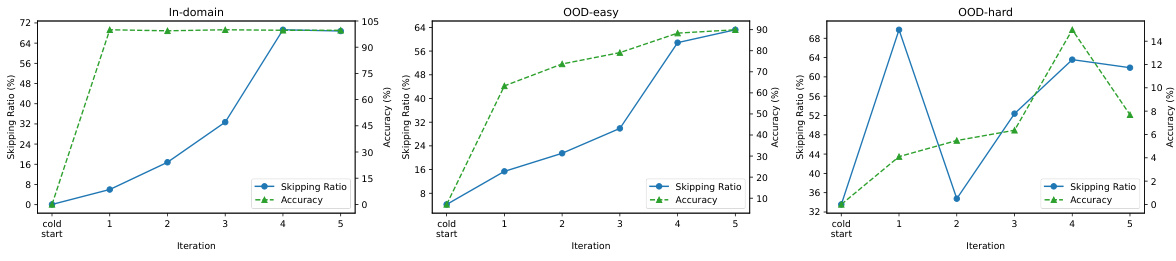

This figure shows how the accuracy of the model’s ability to skip steps improves over the iterations during the training process with cold start. The x-axis represents the iteration number, and the y-axis represents the percentage accuracy of correctly skipped steps. Two lines are shown, one for skipping one step (i=1) and one for skipping two steps (i=2). The plot illustrates that the accuracy increases with each iteration, demonstrating the model’s learning and improvement in its step-skipping capabilities.

This figure shows three different reasoning tasks used in the paper’s experiments: Analog of Algebra, Multi-digit Addition, and Directional Reasoning. Each task presents a problem with a detailed step-by-step solution to guide the model’s reasoning process. The complexity of steps varies across tasks, making it suitable for evaluating models’ ability to perform step-skipping behaviors during reasoning.

This figure shows three example tasks used in the paper’s experiments to evaluate the model’s step-skipping abilities. Each task (Analog of Algebra, Multi-digit Addition, and Directional Reasoning) is illustrated with a sample question and its corresponding solution, which is broken down into a series of detailed steps. This helps demonstrate the type of reasoning problems the model is trained and tested on, highlighting the complexity that step-skipping can simplify.

This figure illustrates the concept of step-skipping in equation solving. The left side shows a problem solved step-by-step, following a complete and detailed solution process. The right side demonstrates the same problem solved by an expert, skipping some intermediate steps to reach the solution more efficiently. This difference highlights the ability of human experts to streamline their reasoning by omitting redundant or obvious steps. The figure serves as a visual example used to guide language models to learn and adopt this step-skipping behavior.

More on tables

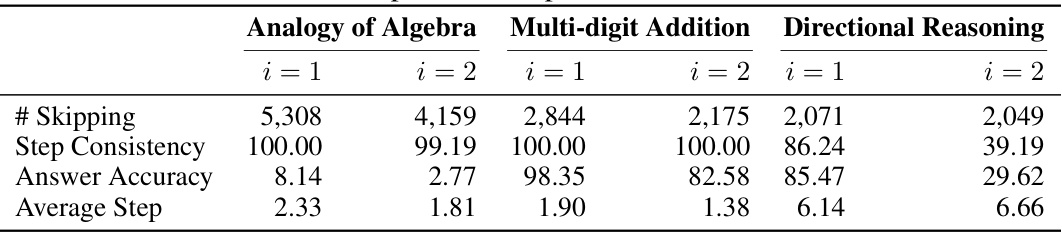

This table presents the results of the step-number-following ability test on the initialized Llama2 model across three different reasoning tasks. It shows the number of times the model skipped steps, how consistently the model followed the requested number of steps, the accuracy of the answers when the model skipped steps, and the average number of steps used in each task. These metrics offer insights into the model’s ability to adhere to instructions regarding the number of reasoning steps to be included in its answers.

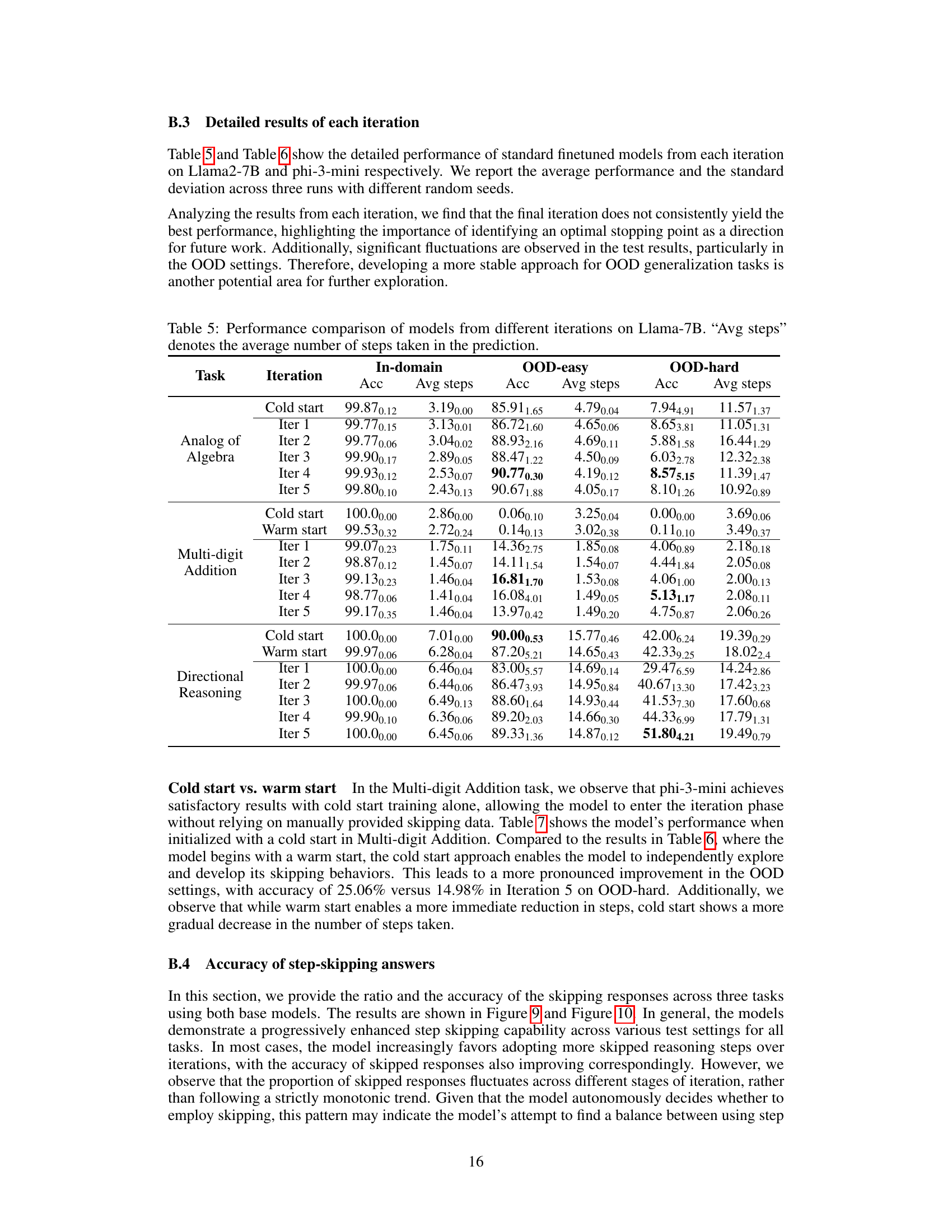

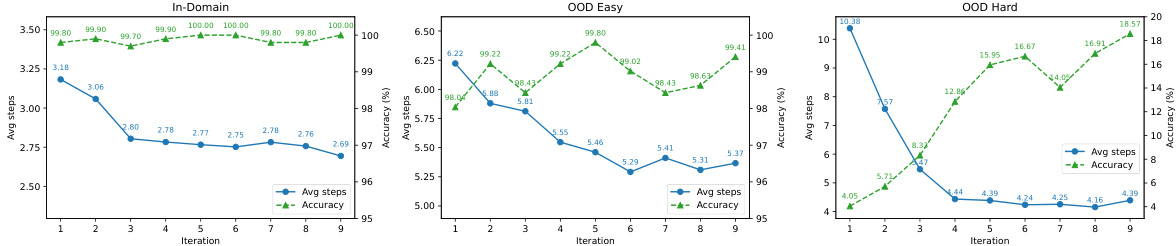

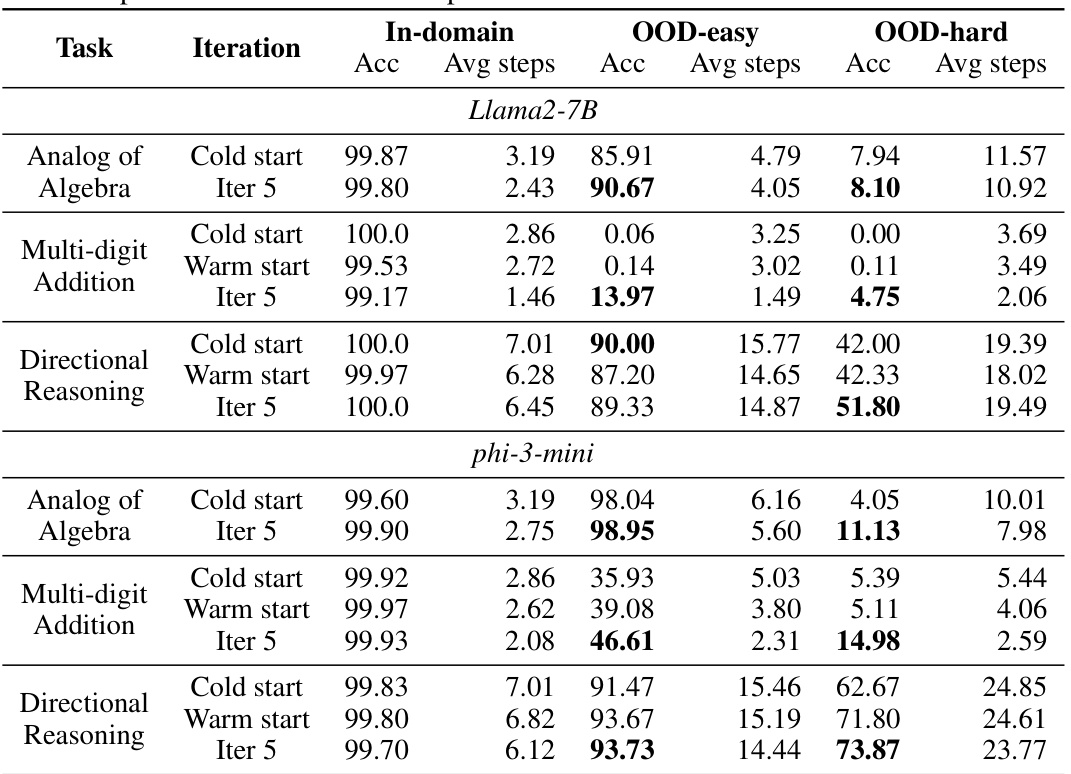

This table compares the performance of language models trained with different data across various iterations. It shows the accuracy and average number of steps taken by the models on in-domain and out-of-domain datasets. The in-domain data is the original data used for training, while the out-of-domain data represents new data with varying difficulty levels. The table highlights the impact of including skipped reasoning steps within the dataset, demonstrating improved efficiency and often better generalization performance.

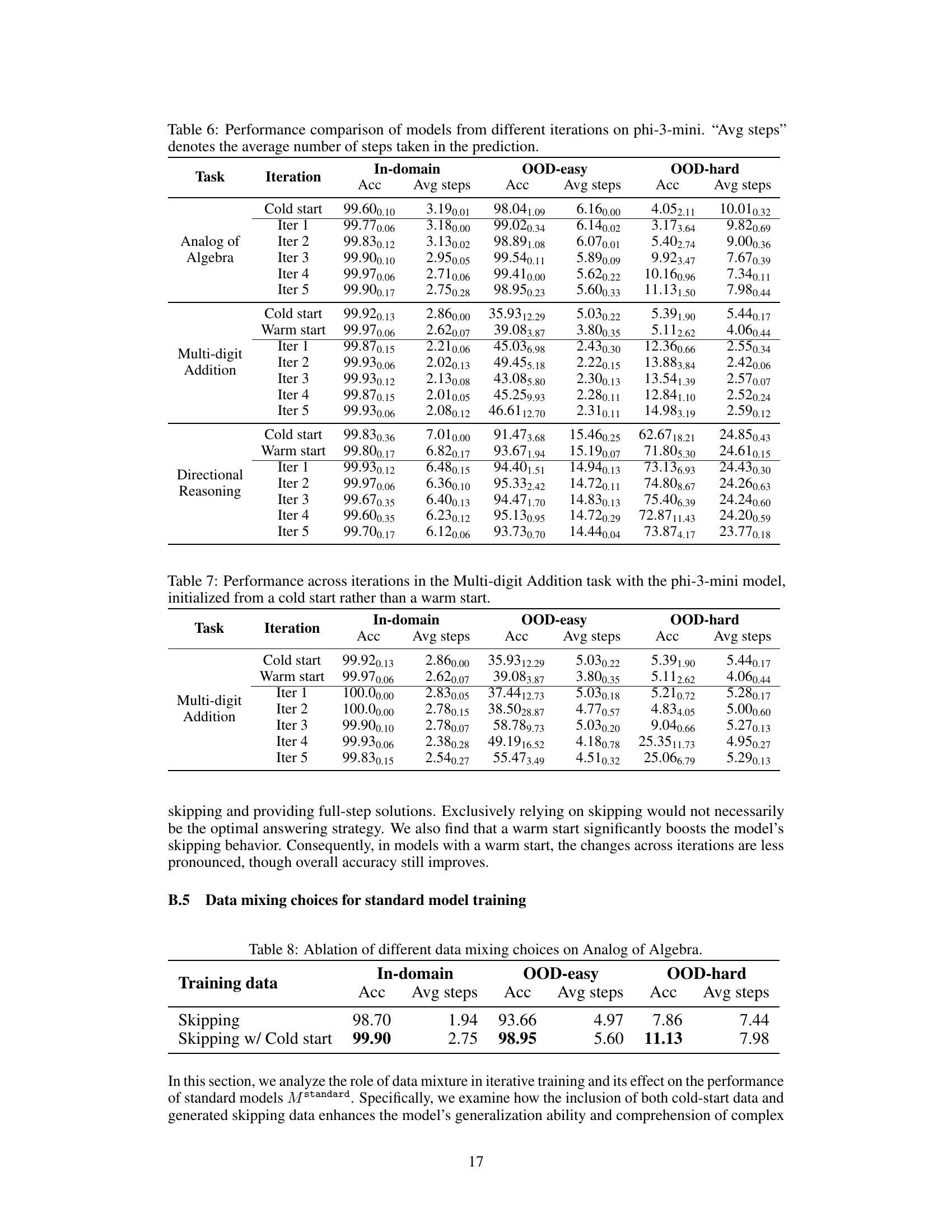

This table compares the performance of language models trained with different methods (cold start, warm start, and iterative training with skipped steps) across three reasoning tasks. It shows the accuracy and average number of reasoning steps used by the models on in-domain and out-of-domain datasets. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of incorporating skipped steps into the training data, leading to improved generalization and efficiency in solving problems.

This table compares the performance of language models across different phases (iterations) of training. It shows the accuracy and average number of steps taken by the models to solve problems in three different scenarios: in-domain (standard test set), OOD-easy (out-of-distribution, easier), and OOD-hard (out-of-distribution, harder). The comparison highlights the impact of incorporating step-skipping data during training on the model’s efficiency and generalization ability.

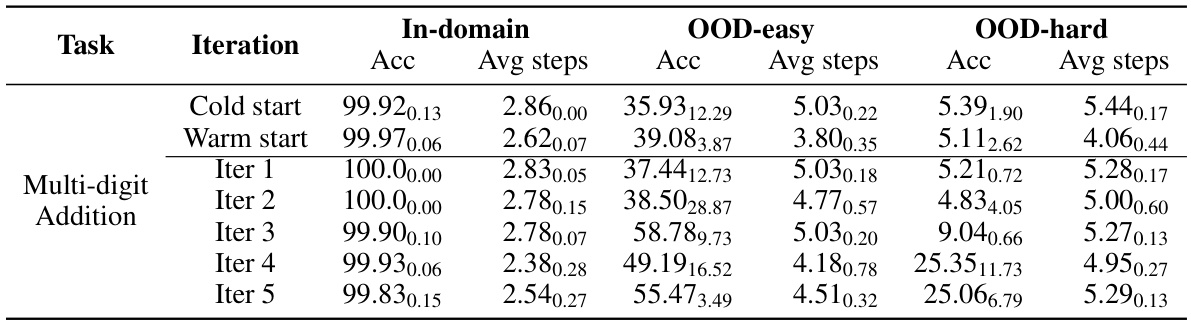

This table compares the performance of language models across different training phases (iterations) and dataset types (in-domain and out-of-domain). It shows that incorporating skipped reasoning steps into the training data leads to improved accuracy and efficiency (fewer steps) in both in-domain and out-of-domain tasks, highlighting the models’ ability to generalize well and solve problems more effectively. The table specifically indicates the average number of steps used in predictions across the various phases and dataset types.

This table compares the performance of language models across different training phases (cold start, warm start, and iterations) for three different tasks (Analog of Algebra, Multi-digit Addition, and Directional Reasoning). It shows the accuracy and average number of steps used by the model in both in-domain and out-of-domain (OOD-easy and OOD-hard) settings. The results demonstrate how the introduction of skipped reasoning steps, generated through the iterative training process, affects the models’ performance, showing an improvement in both efficiency (fewer steps) and generalization capabilities.

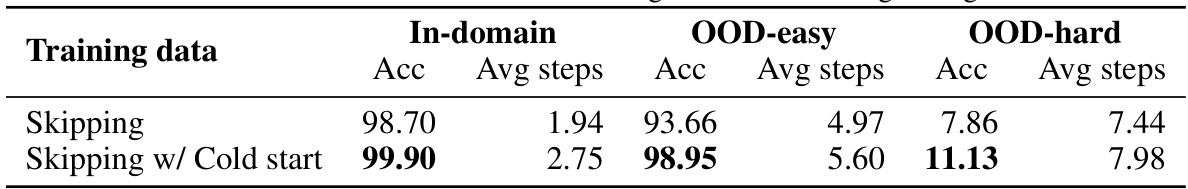

This table presents the results of an ablation study that investigates the impact of different data mixing strategies on the performance of a model trained on the Analog of Algebra task. Specifically, it compares the performance of models trained using only generated skipping data (Skipping) versus models trained using a combination of cold-start data and generated skipping data (Skipping w/ Cold start). The results are presented in terms of accuracy and average number of steps for in-domain, OOD-easy, and OOD-hard datasets, illustrating the effect of different data combinations on model performance and generalization ability.

This table presents the results of an experiment designed to evaluate the cross-domain generalization of the step-skipping ability learned by the model. The experiment withheld step-skipping data from one task at a time, while training on full-step data and step-skipping data from the other two tasks. The ‘All’ setting serves as a baseline, using only full-step data for training across all three tasks. The table compares the in-domain, OOD-easy, and OOD-hard performance of the model across different evaluation tasks (Analog of Algebra, Multi-digit Addition, and Directional Reasoning), showing how the absence of step-skipping data in a specific task impacts overall performance.

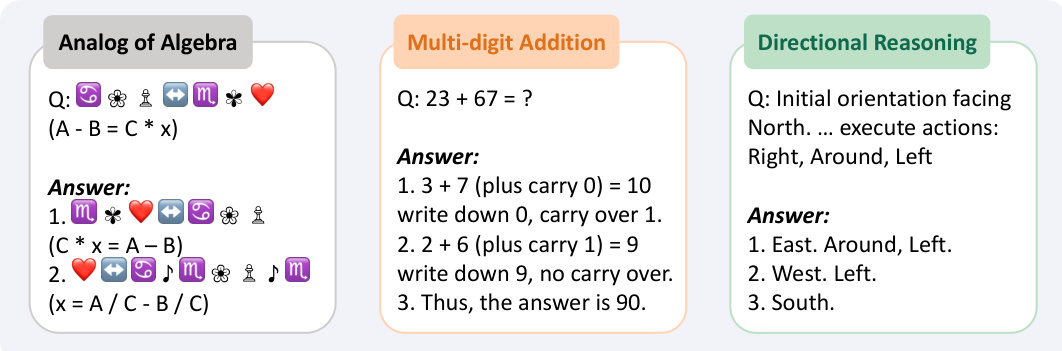

This table shows the dataset split used for GSM8K experiments in the paper. The GSM8K dataset was split into in-domain and out-of-domain sets based on the number of steps required to solve the problems. The in-domain set contained problems requiring no more than 4 steps, while the out-of-domain set contained the rest. The table shows the number of examples in the training and testing sets for both in-domain and out-of-domain problems.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on the GSM8K dataset across five iterations (including a cold start). The accuracy and average number of steps are shown for in-domain (Test-ID) and out-of-domain (Test-OOD and Train-OOD) data. The results demonstrate how the model’s step-skipping behavior evolves over iterations and how it performs on different data conditions.

Full paper#