↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Most LLM benchmarks use a static, single-turn format, ignoring real-world interactive scenarios. This is problematic for high-stakes applications, where incomplete information is common and follow-up questions are crucial for reliable decision-making. The unreliability stems from LLMs’ training to answer any question, even without sufficient knowledge.

To address this, the paper introduces MEDIQ, an interactive benchmark that simulates clinical interactions. It features a ‘Patient System’ providing partial information and an ‘Expert System’ (LLM) that asks clarifying questions before making a diagnosis. Results show that directly prompting LLMs to ask questions decreases performance, highlighting the difficulty of adapting LLMs to interactive settings. However, using abstention strategies to manage uncertainty improves accuracy, demonstrating the importance of developing LLMs that can proactively seek more information.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with LLMs in high-stakes applications like healthcare. It highlights a critical limitation of current LLMs—their inability to effectively seek information in interactive settings—and proposes a novel benchmark (MEDIQ) to evaluate this. This opens up new avenues for improving LLM reliability and developing more robust, interactive AI systems.

Visual Insights#

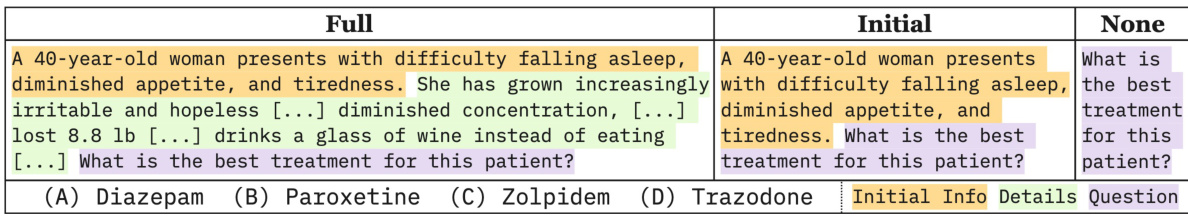

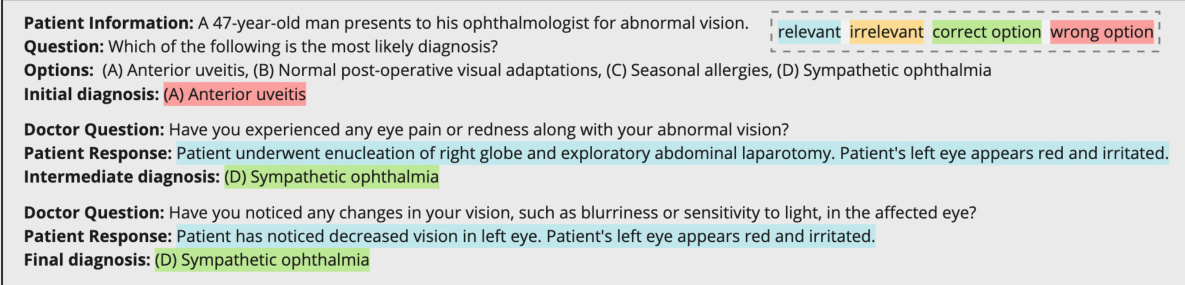

This figure compares three scenarios of medical question answering. The first is a standard setup where all necessary information is given at once. The second scenario shows a realistic scenario where LLMs are given partial information at the start and only provide general responses. Finally, the third scenario illustrates the desired information-seeking behavior where the model proactively asks questions to gather more information before providing a response. This last scenario is the one that MEDIQ is trying to achieve.

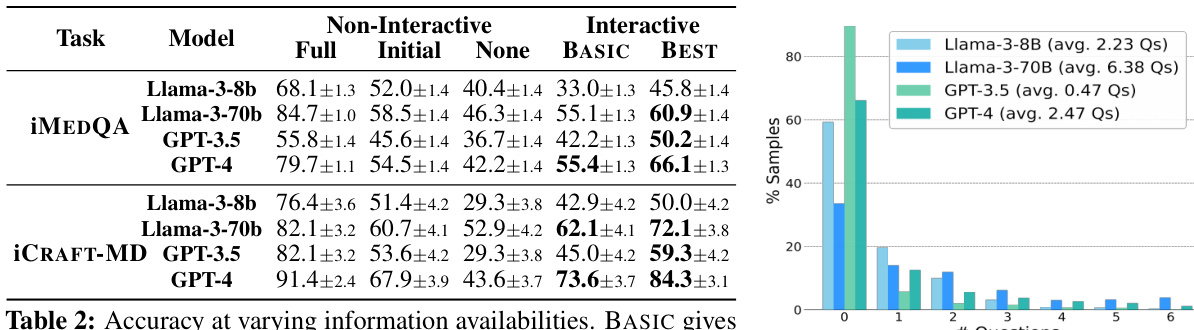

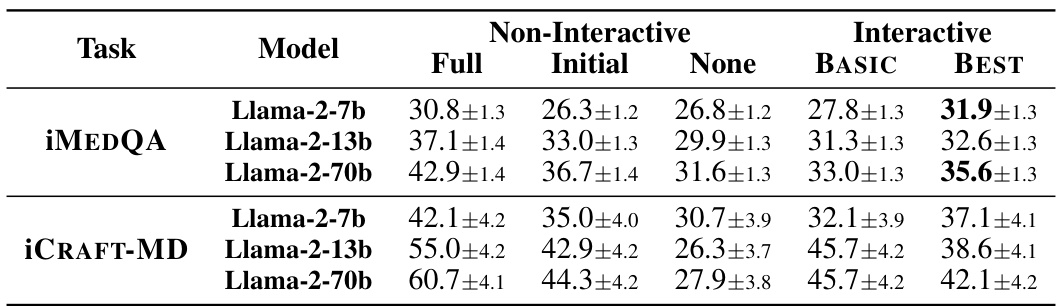

This table presents the accuracy of different LLMs under various information availability conditions (Full, Initial, None) and interactive settings (BASIC, BEST). The results demonstrate that even with the same initial information, interactive settings lead to a decrease in performance compared to the non-interactive setup with initial information. However, improved interactive systems, particularly the ‘BEST’ ones, achieve higher accuracy than the non-interactive model with only initial information, though still falling short of the accuracy achieved when full information is provided.

In-depth insights#

Interactive LLM Eval#

Interactive LLM evaluation presents a significant advancement in assessing large language model capabilities, moving beyond the limitations of static, single-turn benchmarks. The key insight is the recognition that real-world interactions with LLMs are dynamic and iterative, involving a continuous exchange of information. This contrasts sharply with traditional evaluations that provide complete information upfront. Interactive evaluation necessitates the development of new methodologies to assess not only the accuracy of the LLM’s final response but also its ability to strategically ask clarifying questions and process partial or ambiguous input. This requires careful design of simulated interactive environments, often involving a ‘patient’ and ‘doctor’ simulation to mimic real-world scenarios. Metrics should go beyond simple accuracy to include measures of efficiency, such as the number of questions asked, and the quality of questions posed by the LLM. Furthermore, evaluating the ability of LLMs to effectively manage uncertainty, perhaps through strategies like selective abstention, is crucial for robust evaluation of interactive performance. This dynamic evaluation approach opens exciting new avenues for research, allowing for a deeper understanding of how LLMs reason and learn in complex settings. It also fosters the development of more reliable and safe LLMs for critical applications.

MEDIQ Benchmark#

The MEDIQ Benchmark is an interactive evaluation framework designed to assess the reliability of Large Language Models (LLMs) in realistic clinical reasoning scenarios. Unlike traditional single-turn benchmarks, MEDIQ simulates a dynamic clinical consultation involving a Patient System that provides information and an Expert System (LLM) that asks clarifying questions. This interactive setting mirrors actual clinical interactions where initial information is often incomplete, forcing the LLM to actively seek additional data to reach a reliable diagnosis. MEDIQ’s novelty lies in its ability to measure LLM’s proactive information-seeking behavior, which is crucial for high-stakes applications. By converting existing medical QA datasets into an interactive format, MEDIQ offers a more comprehensive and realistic evaluation. The benchmark’s modular design allows for flexibility and extensibility, paving the way for future improvements in LLM reliability and clinical decision support systems.

Abstention Strategies#

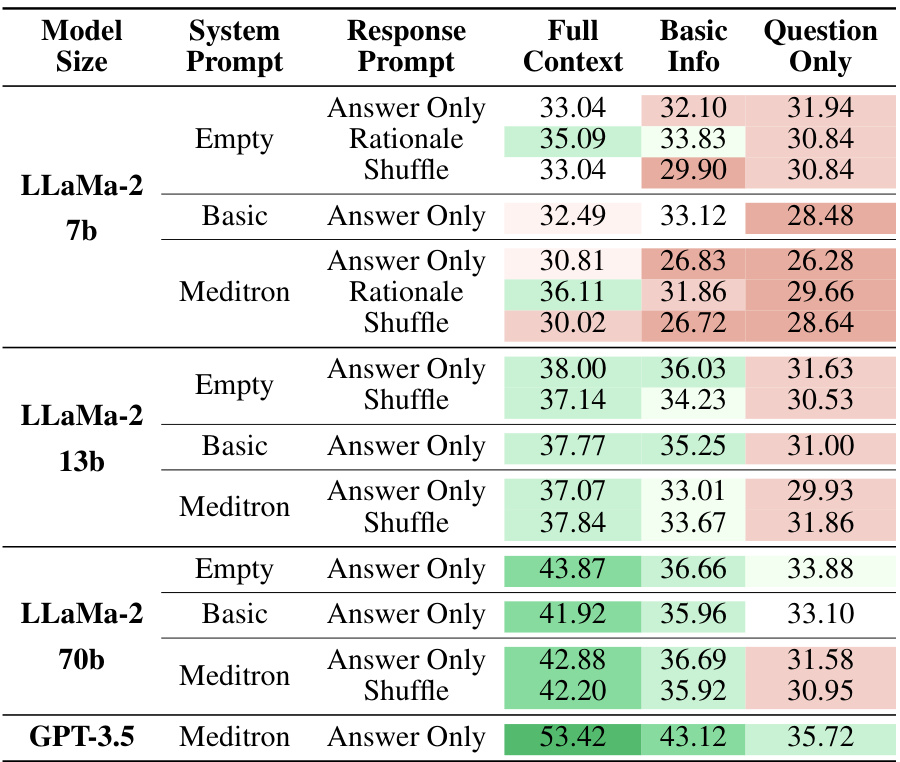

The effectiveness of various abstention strategies in improving the reliability of large language models (LLMs) for complex decision-making tasks is a crucial area of research. The core idea is to have the LLM refrain from answering when its confidence is low, instead prompting for more information. This approach directly addresses the issue of LLMs confidently answering even with incomplete or insufficient knowledge. Different strategies for estimating confidence and determining when to abstain are explored, including numerical scores, binary decisions, and Likert scales. The integration of rationale generation and self-consistency further enhances the performance of these strategies, leading to more accurate confidence estimates and improved decision-making accuracy. These methods demonstrate a promising path towards building more reliable and trustworthy LLMs, particularly in high-stakes applications like medical diagnosis where confidence is critical. Further research should focus on refining these strategies and developing more nuanced approaches to model uncertainty.

LLM Limitations#

Large language models (LLMs), while exhibiting remarkable capabilities, possess inherent limitations that hinder their reliability, especially in high-stakes applications like healthcare. A primary limitation is their tendency to generate plausible-sounding but factually incorrect information, often referred to as hallucinations. This is exacerbated by the models’ training on vast datasets containing inconsistencies and biases, leading to outputs that may be confidently presented but ultimately unreliable. Furthermore, LLMs typically lack the ability to explicitly represent uncertainty or admit to knowledge gaps. They answer confidently even when faced with incomplete or ambiguous information, potentially leading to erroneous decisions. Another critical limitation is the difficulty in controlling the LLM’s reasoning process and ensuring transparency in its decision-making. The black-box nature of these models makes it challenging to understand why a specific output was generated, hindering efforts to debug errors or identify biases. Finally, many LLMs struggle with proactive information seeking, instead relying on information provided upfront. This limits their ability to engage in truly interactive and investigative tasks, especially those requiring iterative clarification and the elicitation of missing details.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving LLM’s ability to identify and request relevant information proactively is crucial; current methods struggle with this. Developing more sophisticated confidence estimation techniques is essential for reliable abstention strategies; current methods don’t perfectly capture uncertainty. The impact of different question-asking strategies on both accuracy and efficiency needs deeper investigation. Expanding the MEDIQ benchmark to include more diverse datasets and clinical scenarios is key to enhancing its generalizability and relevance. Furthermore, research should explore methods to mitigate biases present in LLMs and datasets, including fairness considerations across various demographics and specialties. Finally, incorporating human-in-the-loop elements within the MEDIQ framework might offer additional insights into effective clinical reasoning, providing a richer understanding of the interaction between humans and AI systems in real-world scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

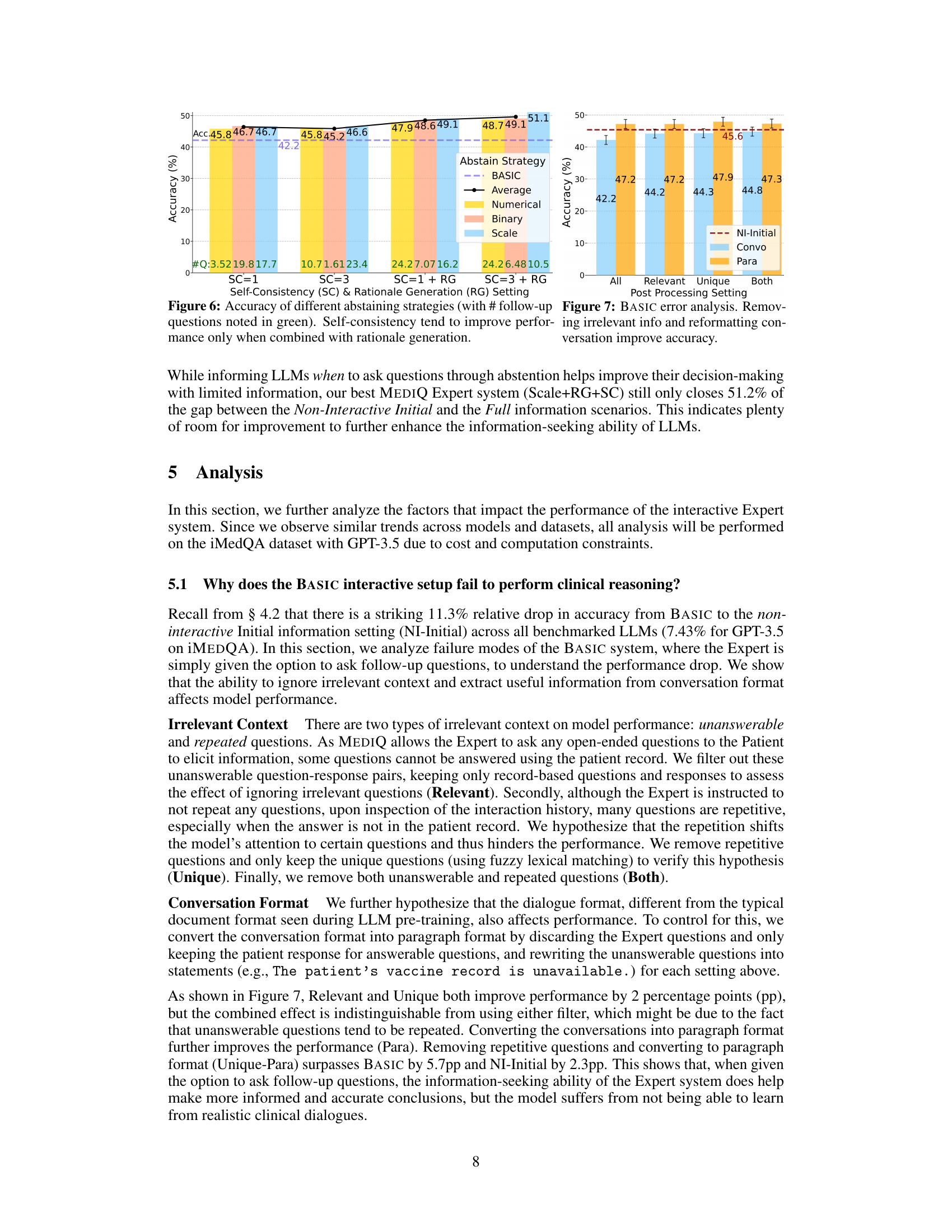

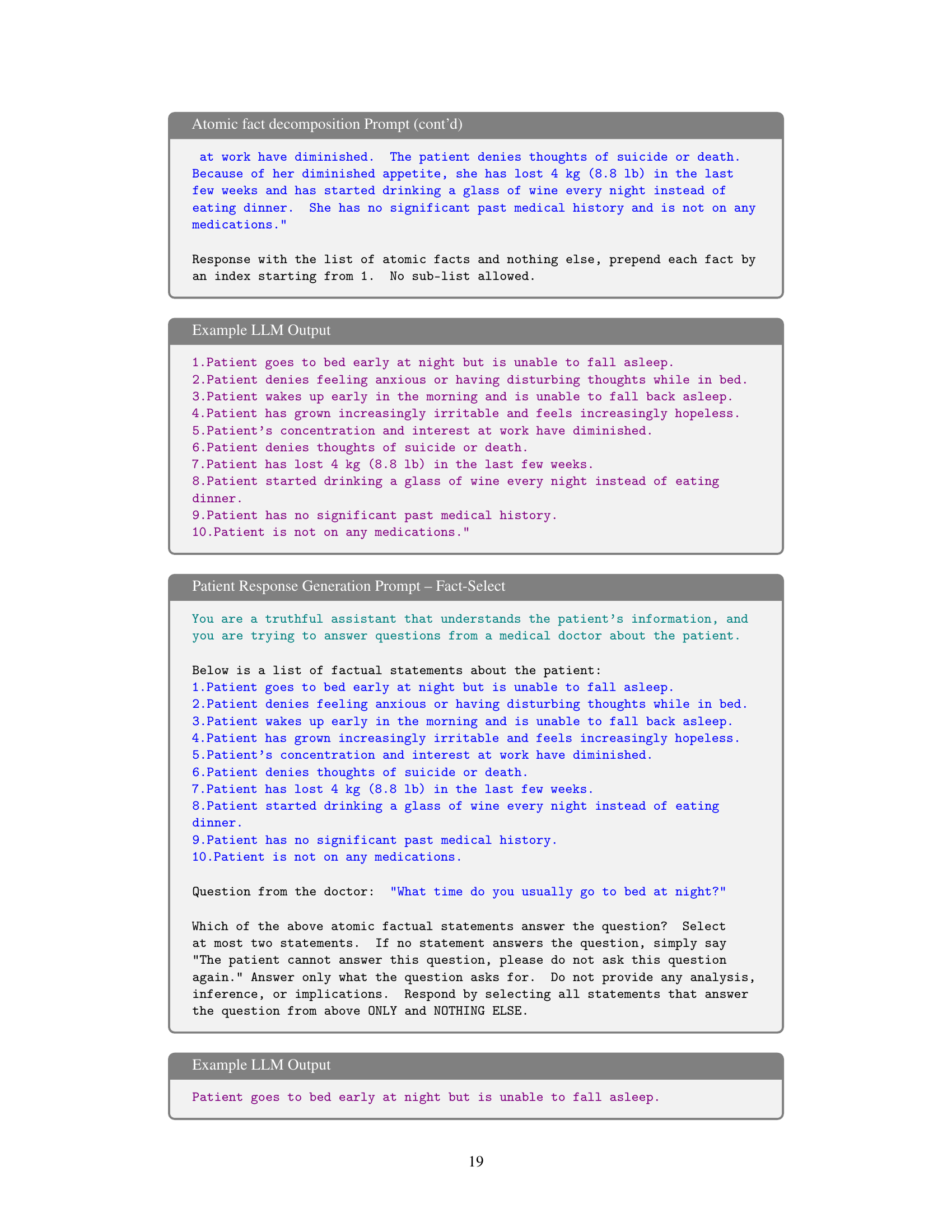

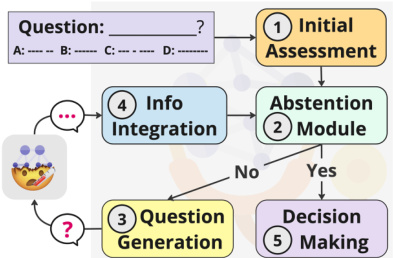

This figure illustrates the MEDIQ benchmark’s framework, which simulates a realistic clinical interaction. The Patient System, possessing the complete patient record, responds to questions from the Expert System. The Expert System, starting with incomplete information, determines if it has sufficient data to answer the medical question; if not, it asks follow-up questions to the Patient System. This process continues iteratively until the Expert System has enough information to answer the question confidently. The figure visually represents the information flow and decision-making process within the MEDIQ framework.

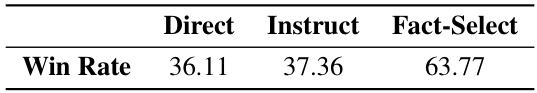

This figure shows the five steps involved in the Expert system: initial assessment, abstention, question generation, information integration, and decision making. Each step is modular, making the system easily modifiable. The Abstention module is key, determining whether the system should answer the question or ask a follow-up question. This decision is based on confidence level. The system proceeds to Question Generation if more information is needed and to Decision Making if confident.

This figure illustrates the difference between standard and realistic medical question-answering (QA) tasks. Standard QA provides all necessary information upfront, while realistic QA mirrors real-world clinical scenarios where information is incomplete initially. The figure emphasizes that effective clinical reasoning often involves a doctor proactively seeking additional details from the patient through follow-up questions, a process that current LLMs struggle to emulate. The MEDIQ framework aims to address this challenge.

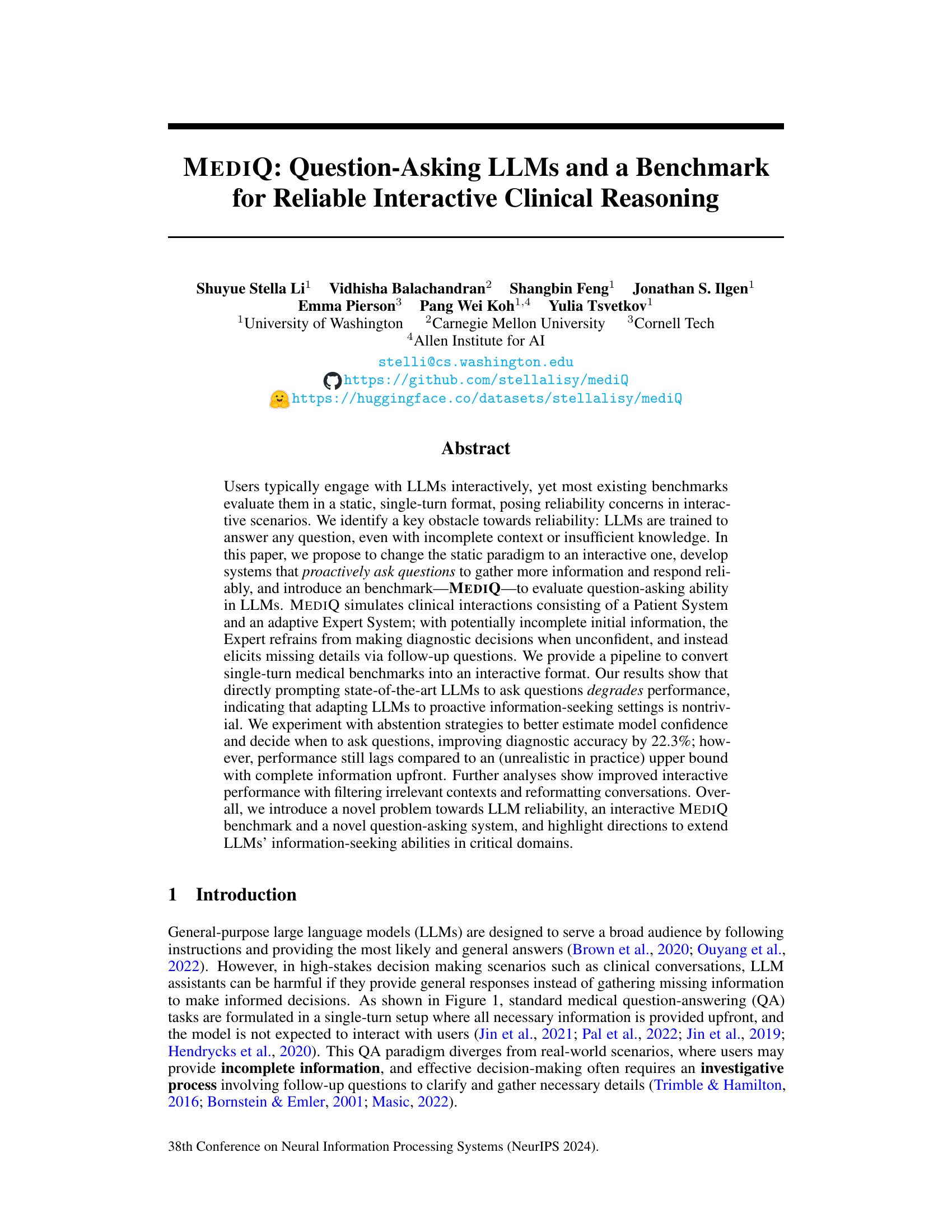

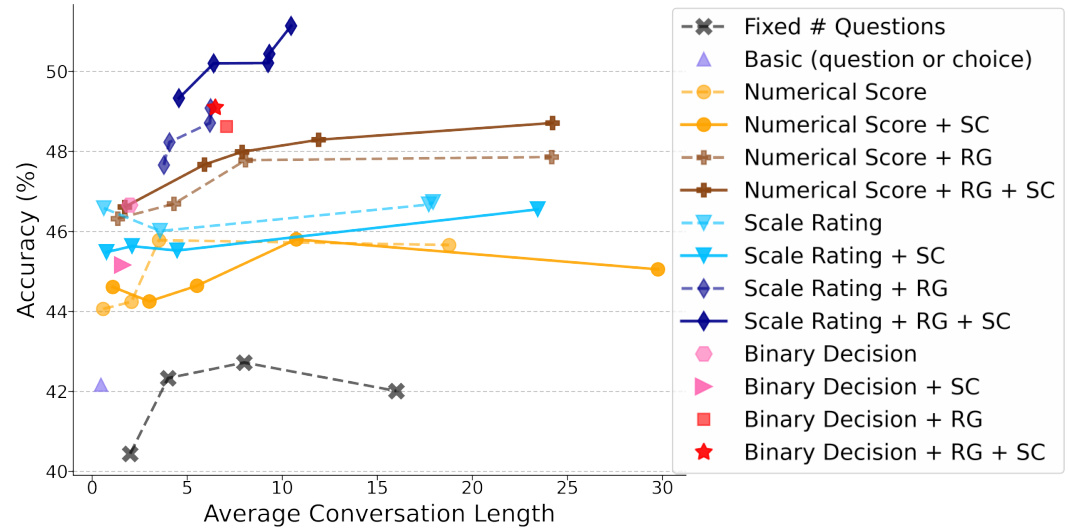

This figure shows the performance of different abstention strategies on the iMEDQA dataset. The x-axis represents the average conversation length (number of questions asked), and the y-axis represents the accuracy. Different lines represent different strategies (BASIC, Average, Numerical, Binary, Scale) with and without self-consistency (SC) and rationale generation (RG). The figure demonstrates that incorporating rationale generation and self-consistency leads to improved accuracy. The best performing strategy (Scale+RG+SC) significantly outperforms the baseline (BASIC).

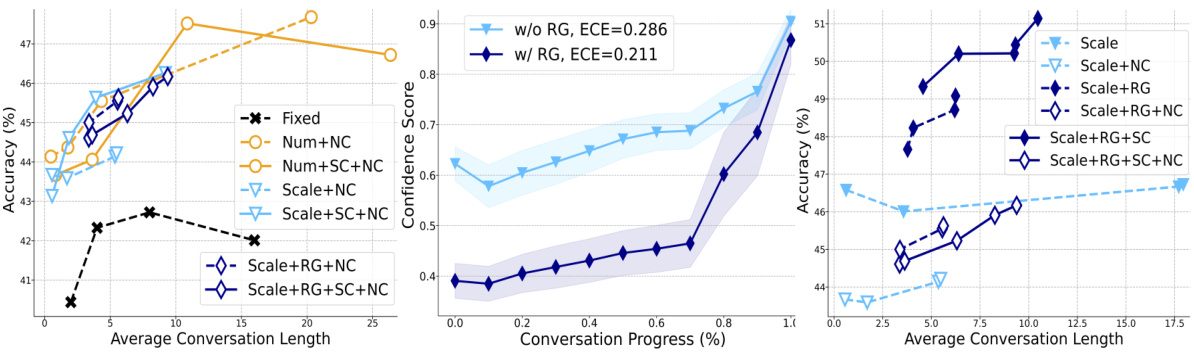

This figure analyzes how the abstention module in the MEDIQ Expert system affects its performance. Panel (a) shows the relationship between accuracy and the number of questions asked, varying the confidence threshold and whether the abstention response was included in the question generation process. Panel (b) illustrates how rationale generation impacts the accuracy of confidence estimates over the course of the interaction. Panel (c) demonstrates how including the abstention response in the question generation process improves the model’s accuracy, especially when combined with rationale generation and self-consistency.

This figure compares three scenarios of medical question answering. The first shows a standard setup where all information is provided at once. The second shows a realistic scenario where only partial information is initially available, and current LLMs fail to adequately seek additional information. The third, representing the proposed MEDIQ framework, depicts the ideal scenario where the LLM proactively seeks further information through a conversational interaction.

This figure shows the performance of different abstention strategies in the MEDIQ benchmark on the iMEDQA dataset. The x-axis represents the average conversation length (number of questions asked), and the y-axis represents the accuracy of the model. Different lines represent different abstention strategies (e.g., using a numerical confidence score, a Likert scale, or a binary decision), with and without rationale generation and self-consistency. The results demonstrate that incorporating rationale generation and self-consistency significantly improves accuracy, especially when using a Likert scale for confidence assessment. The best-performing strategy (Scale+RG+SC) substantially surpasses the basic approach.

This figure shows the impact of interactive information-seeking on diagnostic accuracy across various medical specialties and difficulty levels of questions. It highlights that interactive systems improve accuracy in some specialties, like ophthalmology, but not all. The improvement is also more significant for more complex, clinically focused questions.

This figure compares three different scenarios of medical question answering. The standard setup (left) provides all necessary information at once, while the realistic setup (middle and right) only provides partial information initially. Current LLMs struggle in the realistic scenario, giving only general responses (middle), while the desired behavior (right) would involve a doctor actively eliciting the necessary information through follow-up questions, which is the behavior that the MEDIQ benchmark aims to evaluate.

More on tables

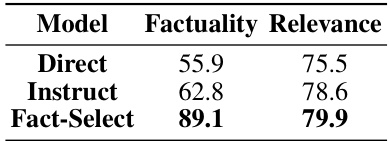

This table presents the results of evaluating the reliability of three different Patient System variants: Direct, Instruct, and Fact-Select. The evaluation metrics used are Factuality and Relevance. Factuality measures the percentage of statements in the Patient System’s response that are supported by the information in the patient record. Relevance measures the average embedding semantic similarity between the generated response and the ground truth statement. The Fact-Select system significantly outperforms the other two systems in terms of factuality, while all three show relatively similar performance on relevance.

This table presents the results of a manual evaluation comparing three different variants of the Patient System: Direct, Instruct, and Fact-Select. The ‘Win Rate’ column indicates the percentage of times each variant’s response was judged as higher quality than the other variant’s response in a pairwise comparison. Fact-Select demonstrates a significantly higher win rate, suggesting it produces more factually accurate and complete responses compared to the Direct and Instruct variants.

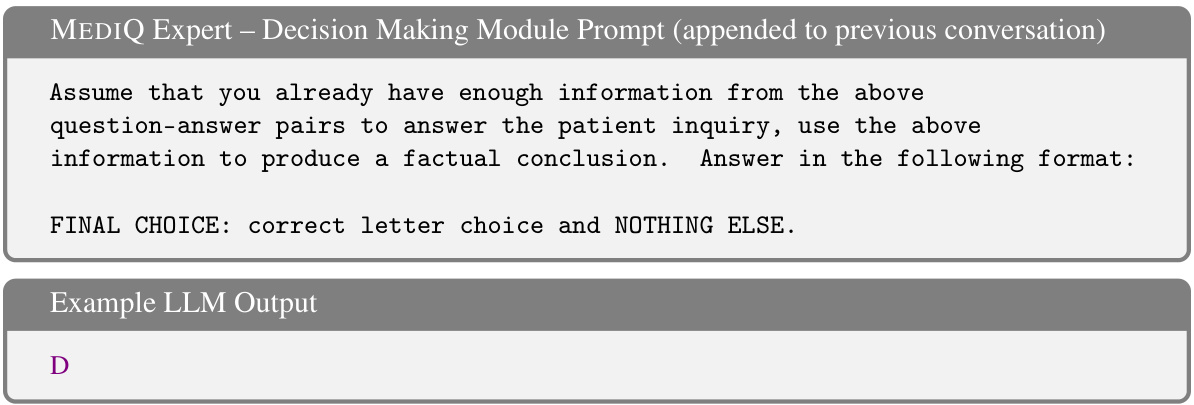

This table presents the accuracy of different LLMs under various information availability levels. It compares non-interactive settings (Full, Initial, None) with the interactive BASIC setting, where the LLM has the option to ask questions. The results show that providing less information degrades accuracy. While the BASIC interactive setting sometimes outperforms the non-interactive Initial setting, it still lags behind the non-interactive Full setting (where complete information is available).

This table compares the accuracy of different LLMs (Llama-3-8b, Llama-3-70b, GPT-3.5, GPT-4) under three different information availability levels (Full, Initial, None) and two interaction settings (Non-interactive, Interactive). The ‘Full’ setup represents standard QA tasks where complete information is provided, while the ‘Initial’ and ‘None’ setups reflect realistic scenarios with incomplete or missing information. The ‘BASIC’ interactive setting allows LLMs to ask follow-up questions, highlighting their information-seeking ability. The ‘BEST’ interactive setting shows the improved accuracy after using additional techniques to address the challenges. The table demonstrates that LLM performance degrades significantly when starting with limited information, even with the ability to ask questions. While advanced techniques can close the performance gap partially, there remains a considerable difference between ideal (full information) and realistic (limited information) scenarios.

This table presents the accuracy of different LLMs (Llama-3-8b, Llama-3-70b, GPT-3.5, GPT-4) under various information availability levels (Full, Initial, None) for two medical question answering tasks (iMEDQA, iCRAFT-MD). It compares the performance of non-interactive models with an interactive model (BASIC) that allows the LLM to ask questions. The results demonstrate that while LLMs perform well with complete information, their accuracy significantly decreases in realistic scenarios with limited initial information and the ability to ask follow-up questions does not naturally improve their performance. The best performing interactive model (BEST) still lags behind the performance with complete information, showcasing a gap between idealized and real-world scenarios.

This table presents the accuracy of different LLMs across various information availability levels (Full, Initial, None) in both non-interactive and interactive settings. The non-interactive setting serves as a baseline, while the interactive setting (BASIC) allows the LLM to ask questions. The results show that while LLMs perform well with complete information, their accuracy decreases significantly when information is incomplete, even when they have the ability to ask clarifying questions. The ‘BEST’ column demonstrates improved performance, representing an optimized interactive system.

This table presents the accuracy of different LLMs (Llama-3-8b, Llama-3-70b, GPT-3.5, GPT-4) on two tasks (iMEDQA and iCRAFT-MD) under different information availability scenarios. The ‘Full’ condition provides complete information, ‘Initial’ provides limited initial information, and ‘None’ provides no initial information. The ‘BASIC’ setting allows the LLMs to ask questions interactively, while the ‘BEST’ setting represents the best performance achieved with improved question-asking strategies. The table highlights the performance gap between models given complete information versus those only given partial information, even when allowed to ask clarifying questions.

This table presents the accuracy of different LLMs (Llama-3, GPT-3.5, GPT-4) under various information availability settings (Full, Initial, None). The ‘Full’ setup provides complete information, the ‘Initial’ setup provides partial information (only age, gender, and chief complaint), and the ‘None’ setup provides no information. The ‘BASIC’ setting allows the LLMs to ask questions interactively. The table shows how the accuracy changes across these conditions, highlighting the impact of interactive questioning. Bold values indicate where interactive performance exceeds the performance when only initial information was provided.

Full paper#