↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) and Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) are powerful but have limitations. SNNs are energy-efficient but lack the capacity of deep learning models, while MoE enhances capacity but is computationally expensive. This paper aims to combine SNNs’ energy efficiency with MoE’s capacity for conditional computation.

The researchers introduce Spiking Experts Mixture Mechanism (SEMM), which reformulates MoE in the context of SNNs. SEMM’s spike-driven and dynamic sparse nature makes it suitable for SNNs. By integrating SEMM into Spiking Transformers, they develop Experts Mixture Spiking Attention (EMSA) and Experts Mixture Spiking Perceptron (EMSP), which show significant performance improvements over baseline Spiking Transformers on neuromorphic and static datasets. The results suggest SEMM is a promising approach to building more efficient and powerful AI systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is significant as it bridges the gap between Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) and Mixture-of-Experts (MoE), two promising areas of deep learning research. It introduces a novel mechanism that enables efficient and biologically plausible conditional computation, opening new avenues for energy-efficient and powerful AI systems. The findings demonstrate stable performance gains on various datasets, prompting further research into SNN-MoE architectures for neuromorphic computing.

Visual Insights#

This figure compares the architecture of the traditional ANN-MoE (Artificial Neural Network Mixture of Experts) with the proposed SEMM (Spiking Experts Mixture Mechanism). ANN-MoE uses softmax and TopK for routing and sparsification, while SEMM uses a spiking router and element-wise operations. The core difference lies in how experts’ weights are selected. ANN-MoE employs softmax and then TopK for selection, whereas SEMM uses a spiking router that dynamically adapts to the input and performs element-wise addition of spiking sequences from experts.

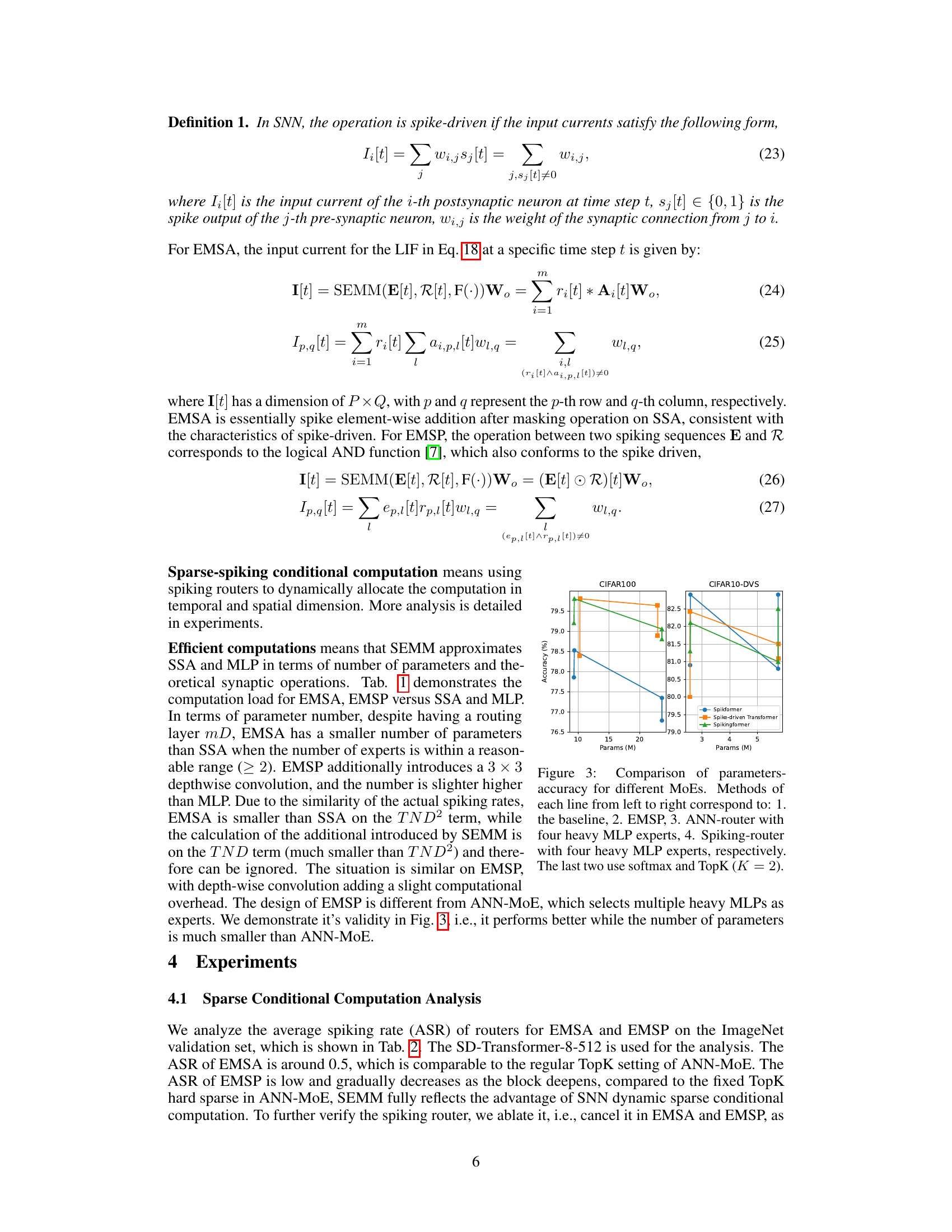

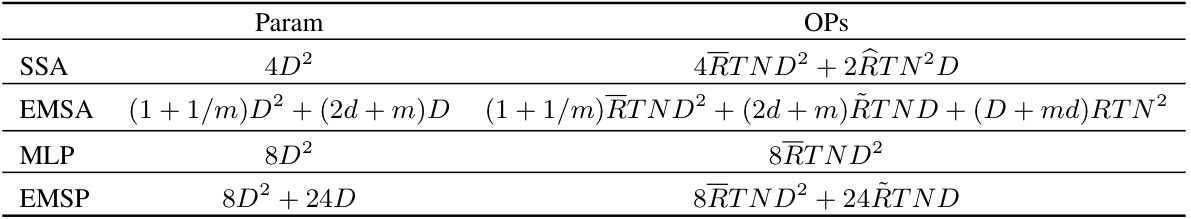

This table compares the number of parameters and theoretical synaptic operations for different components of the Spiking Transformer model, namely SSA (Spiking Self-Attention), EMSA (Experts Mixture Spiking Attention), MLP (Multi-layer Perceptron), and EMSP (Experts Mixture Spiking Perceptron). It also includes the average spike firing rates for various matrices involved in these components. The table aims to demonstrate the computational efficiency of SEMM (Spiking Experts Mixture Mechanism) by comparing it to the baselines.

In-depth insights#

Spiking MoE#

Spiking MoE, a fascinating concept, merges the energy efficiency of spiking neural networks (SNNs) with the scalability and adaptability of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models. The core challenge lies in reconciling the inherent sparsity and event-driven nature of SNNs with the dense, computationally intensive softmax gating mechanism typically used in MoEs. A key innovation would involve replacing softmax with a spiking-based routing mechanism, potentially leveraging spike timing or frequency to represent expert weights. This would require careful consideration of how to maintain accuracy and efficiency while ensuring the sparse, asynchronous nature of SNNs is preserved. Successfully integrating Spiking MoE could unlock significant advancements in energy-efficient deep learning, enabling larger models with improved performance for resource-constrained applications and neuromorphic hardware. However, significant hurdles remain in developing efficient training algorithms for such architectures and establishing benchmarks to assess their true potential.

SEMM Mechanism#

The Spiking Experts Mixture Mechanism (SEMM) is a novel approach to integrate the advantages of Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) and Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models. SEMM’s core innovation lies in its spike-driven nature, avoiding the computationally expensive softmax function used in traditional MoE. Instead, it leverages the inherent sparsity of SNNs for dynamic, conditional computation. By using spiking sequences for both expert outputs and routing decisions, and employing element-wise operations, SEMM achieves efficient and sparse conditional computation. This avoids multiplication, a significant advantage for neuromorphic hardware implementations. The method’s flexibility shines through its seamless integration within Spiking Transformers, enhancing Spiking Self-Attention (EMSA) and Spiking MLP (EMSP) modules. The resulting model demonstrates improvements on both neuromorphic and static datasets while maintaining computational efficiency, making SEMM a significant contribution to the field of SNNs.

EMSA & EMSP#

The proposed Experts Mixture Spiking Attention (EMSA) and Experts Mixture Spiking Perceptron (EMSP) modules represent a novel approach to integrating the efficiency of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) with the inherent sparsity of Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs). EMSA restructures the Spiking Self-Attention mechanism, replacing individual attention heads with spiking experts, dynamically routing spike-based information via a spiking router. This contrasts with traditional MoE’s reliance on softmax and TopK for routing, making it more biologically plausible and computationally efficient for SNNs. EMSP similarly adapts the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), introducing channel-wise spiking experts to achieve sparse conditional computation within the MLP layer. By replacing standard SSA and MLP with EMSA and EMSP, respectively, within a Spiking Transformer architecture, this approach aims for improved performance and energy efficiency while maintaining the benefits of MoE. The effectiveness of this approach is supported by experimental results which demonstrate a significant improvement over baseline models on various datasets, highlighting the potential of this new paradigm in SNN research.

Sparse Computations#

Sparse computations are a crucial concept in modern machine learning, aiming to reduce computational costs and improve efficiency by leveraging sparsity in data or model parameters. In the context of spiking neural networks (SNNs), sparse computations are particularly relevant due to the inherent sparsity of spike trains. The core idea is to perform computations only where necessary, avoiding unnecessary calculations on zeros or insignificant values. This strategy translates into reduced energy consumption and faster processing, which are significant advantages for resource-constrained environments and large-scale deployments. Successfully implementing sparse computation techniques in SNNs requires careful consideration of the underlying network architecture and learning algorithms. Effective routing mechanisms are vital to selectively activate relevant parts of the network, while maintaining accuracy and performance. Furthermore, hardware acceleration is essential for real-world applications, as specialized neuromorphic chips can provide significant speedups for processing sparse data.

Future of SNNs#

The future of Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) is bright, driven by their biological plausibility and energy efficiency. While challenges remain in training and scaling, advancements in neuromorphic hardware and innovative training algorithms like temporal backpropagation and STBP are paving the way for more powerful and efficient SNNs. Integration with other neural network architectures, such as transformers, holds significant promise, as demonstrated by the rise of Spiking Transformers. The potential applications are vast, ranging from low-power edge computing to neuromorphic AI acceleration, promising a future where SNNs become a dominant force in artificial intelligence.

More visual insights#

More on figures

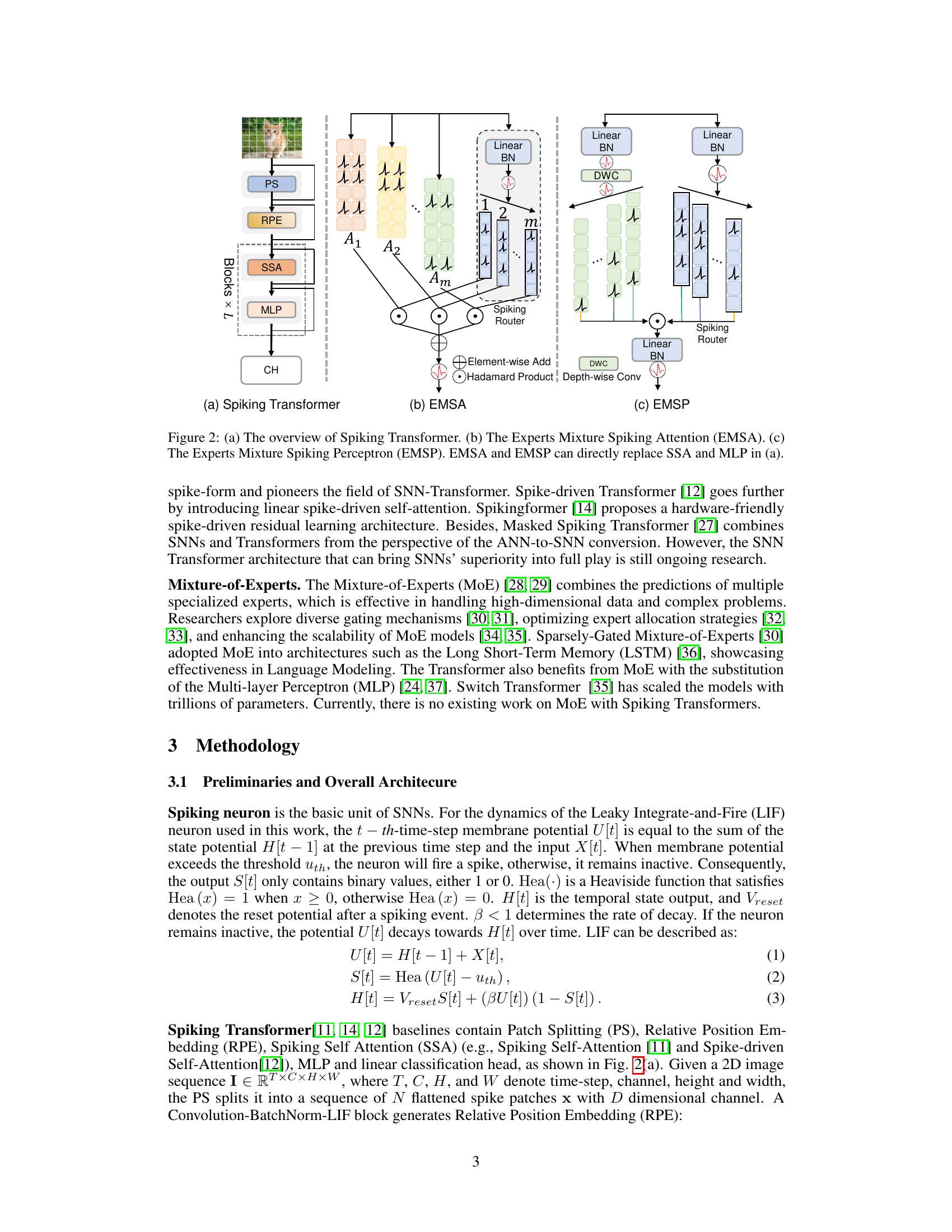

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Spiking Transformer and its components: (a) shows the overall Spiking Transformer architecture, highlighting the Patch Splitting (PS), Relative Position Embedding (RPE), Spiking Self-Attention (SSA), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), and Classification Head (CH). (b) and (c) illustrate the proposed modifications, EMSA and EMSP respectively, which are designed to replace SSA and MLP in the base Spiking Transformer. EMSA uses a Spiking Router and multiple spiking attention experts, while EMSP integrates a channel-wise mixture of experts within the MLP structure. Both utilize the Spiking Experts Mixture Mechanism (SEMM) for spike-driven conditional computation.

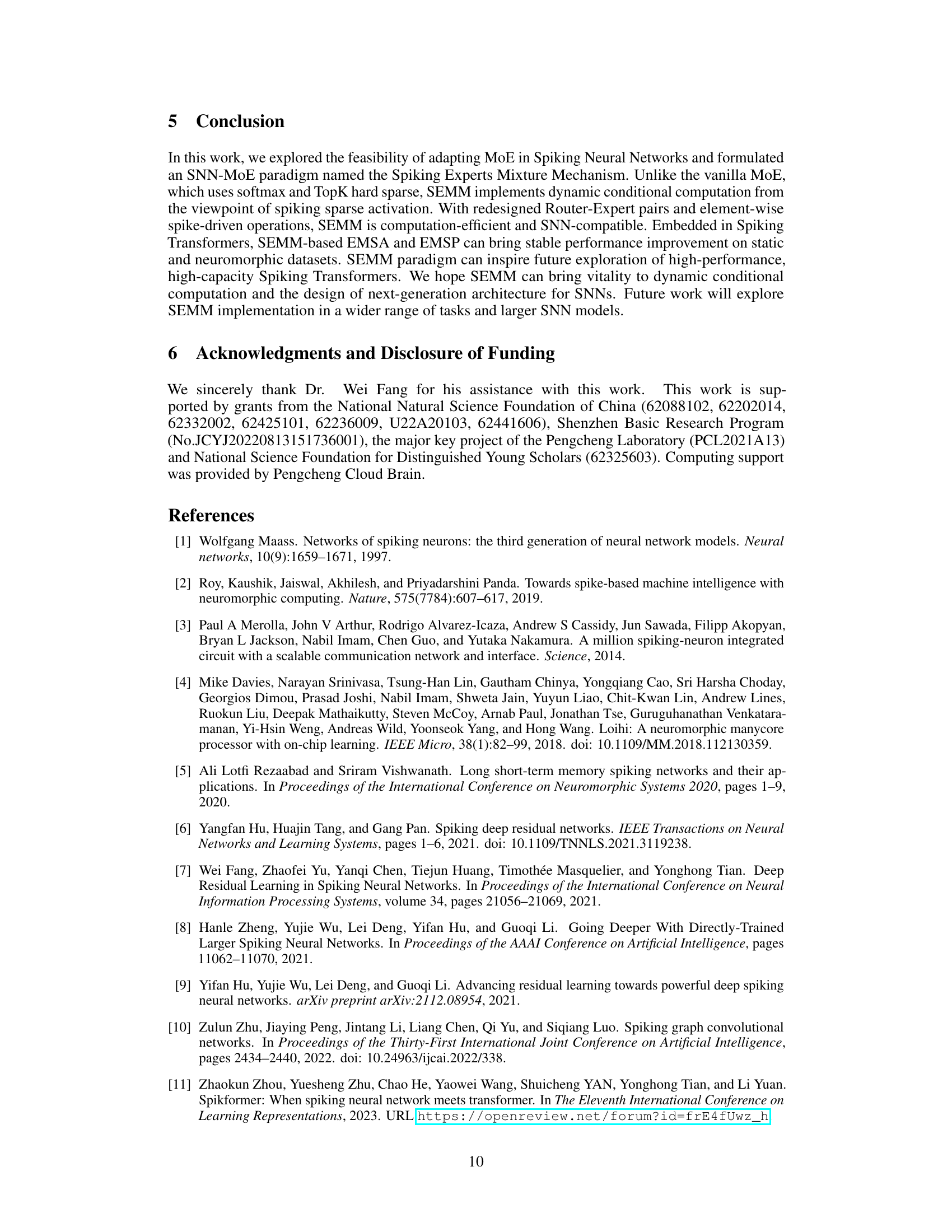

This figure shows the accuracy results for different numbers of experts used in EMSA (Experts Mixture Spiking Attention) and EMSP (Experts Mixture Spiking Perceptron) across CIFAR10 and CIFAR10-DVS datasets. It demonstrates the impact of varying the number of experts on model performance. The baseline and three different spiking transformer models are included in the plot, demonstrating the stable and consistent performance improvements achieved by SEMM (Spiking Experts Mixture Mechanism) across different expert numbers.

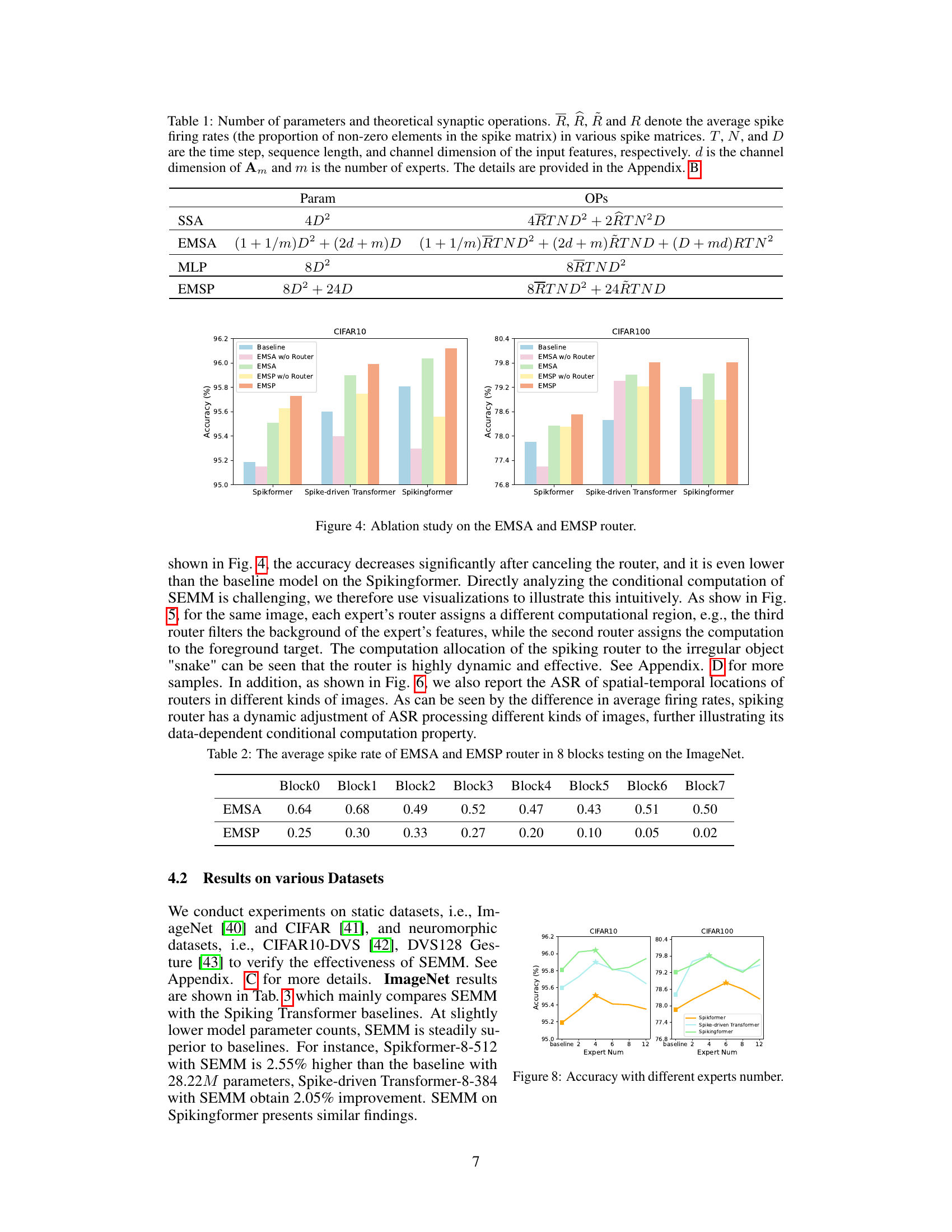

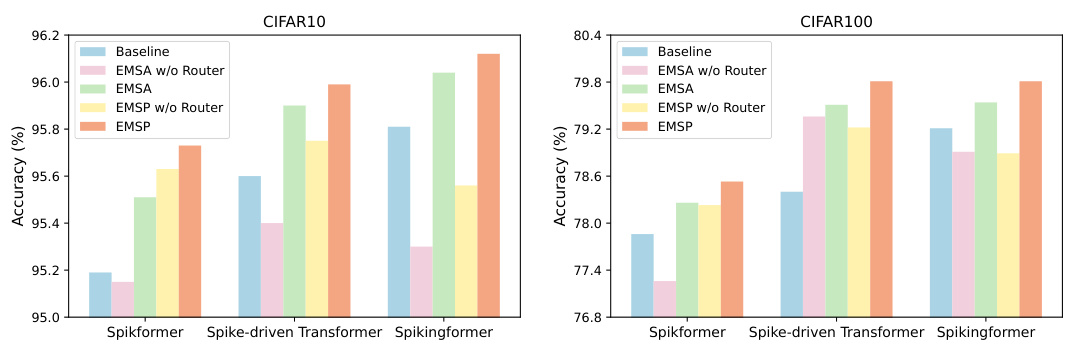

This figure presents an ablation study on the effectiveness of the router components within the Experts Mixture Spiking Attention (EMSA) and Experts Mixture Spiking Perceptron (EMSP) modules. It shows the accuracy results on CIFAR10 and CIFAR100 datasets when comparing the baseline models against versions with the router removed for both EMSA and EMSP, as well as the complete EMSA and EMSP models. The results demonstrate that the router is crucial for achieving high performance in both modules.

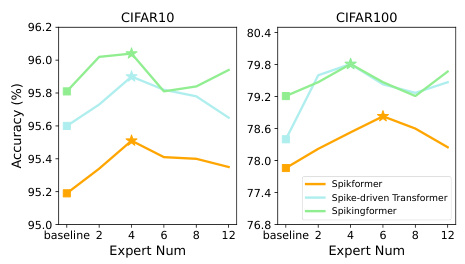

This figure shows the accuracy of three different spiking transformer models (Spikformer, Spike-driven Transformer, and Spikingformer) on CIFAR10 and CIFAR100 datasets with varying numbers of experts in the experts mixture mechanism. The x-axis represents the number of experts (2, 4, 6, 8, 12), and the y-axis represents the accuracy in percentage. The results demonstrate the impact of the number of experts on the overall model performance for each architecture. The figure provides a visual comparison, allowing for easy assessment of the effects of the expert mixture mechanism on classification accuracy.

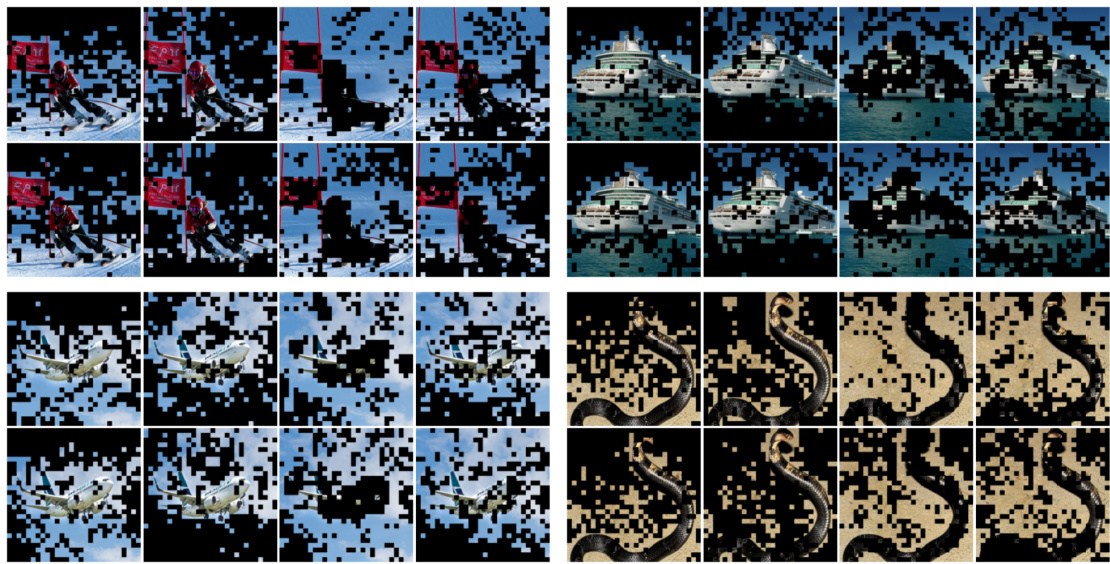

This figure visualizes the dynamic sparsity of the spiking router in SEMM. Each subplot shows a different image patch processed by the model, and the black pixels indicate that the router has a value of 0, effectively masking that portion of the input for that particular expert at that particular time step. The figure demonstrates how the spiking router dynamically allocates computation across experts and timesteps, adapting to the image content.

This figure visualizes the average spiking rate (ASR) of the spiking router in the spatial-temporal dimension for different image categories from ImageNet. It demonstrates the dynamic and data-dependent nature of the router’s conditional computation. The height of each cube represents the time dimension, and the color intensity shows the ASR. The subfigures (a) and (b) show the ASR for different images (Japanese spaniel and volcano respectively). The figure supports the claim that SEMM realizes sparse conditional computation, adapting its resource allocation according to the input data.

The figure shows the accuracy of three different Spiking Transformer models (Spikformer, Spike-driven Transformer, and Spikingformer) on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets with varying numbers of experts (4, 6, 8, 12). It demonstrates the impact of the number of experts within the Experts Mixture Spiking Mechanism (SEMM) on the overall accuracy of the models.

This figure visualizes the dynamic sparsity of the spiking router in SEMM for different experts and time steps. Each subplot shows the router’s mask (black indicates a 0 value) applied to the same image patch. The horizontal direction shows different experts, and the vertical direction displays different time steps, highlighting how the router dynamically allocates computation across experts and time.

More on tables

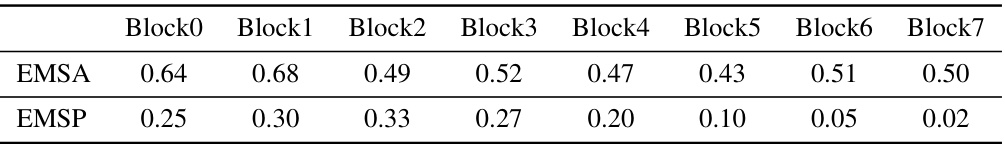

This table shows the average spiking rate (ASR) of the routers for EMSA and EMSP in each of the eight blocks of the Spiking Transformer model tested on the ImageNet dataset. The ASR provides insight into the dynamic sparsity of the routers and their role in conditional computation. Lower ASR values indicate greater sparsity.

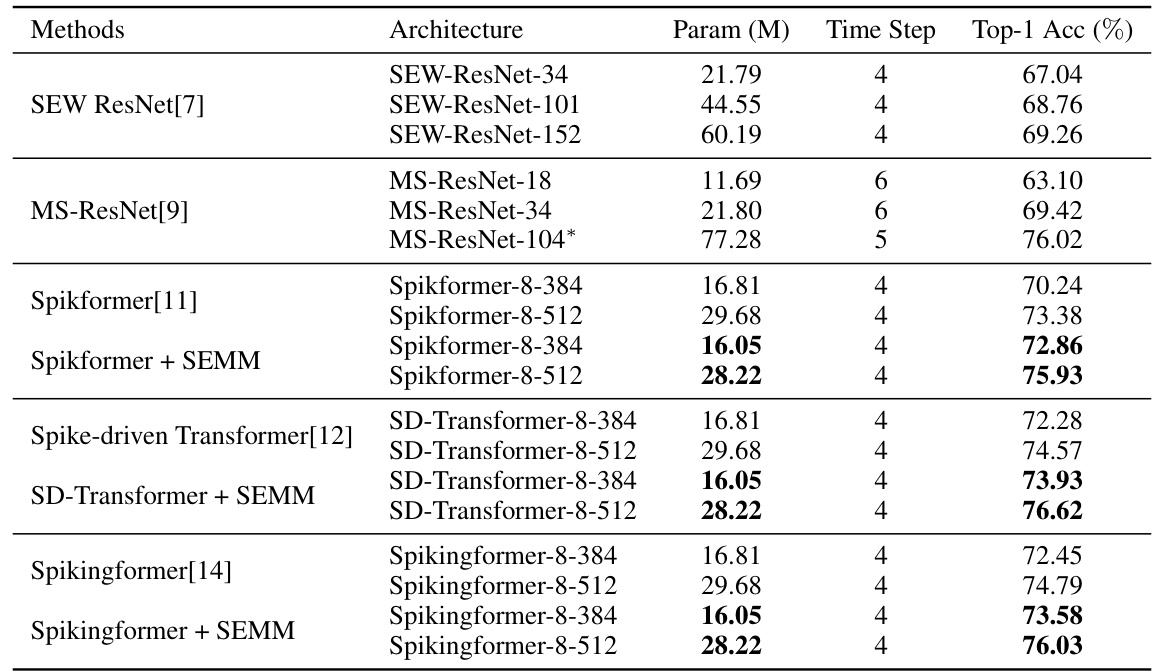

This table presents the results of different Spiking Transformer models on the ImageNet-1k dataset. It compares various architectures (including SEW ResNet, MS-ResNet, Spikformer, Spike-driven Transformer, and Spikingformer) with and without the proposed SEMM method. The table shows the number of parameters (in millions), the number of time steps, and the Top-1 accuracy achieved by each model. This allows for a comparison of model complexity against performance.

This table presents the experimental results of different Spiking Neural Network (SNN) models on three datasets: CIFAR10-DVS, DVS128 Gesture, and CIFAR. It shows the accuracy achieved by each model at different time steps (T). The models include several baseline SNN architectures (tdBN, PLIF, DIET-SNN, Dspike, DSR) and three spiking transformer variants (Spikformer, Spike-Driven Transformer, and Spikingformer) both with and without the proposed Spiking Experts Mixture Mechanism (SEMM). The table highlights the improvement in accuracy obtained by integrating SEMM into the different spiking transformer baselines.

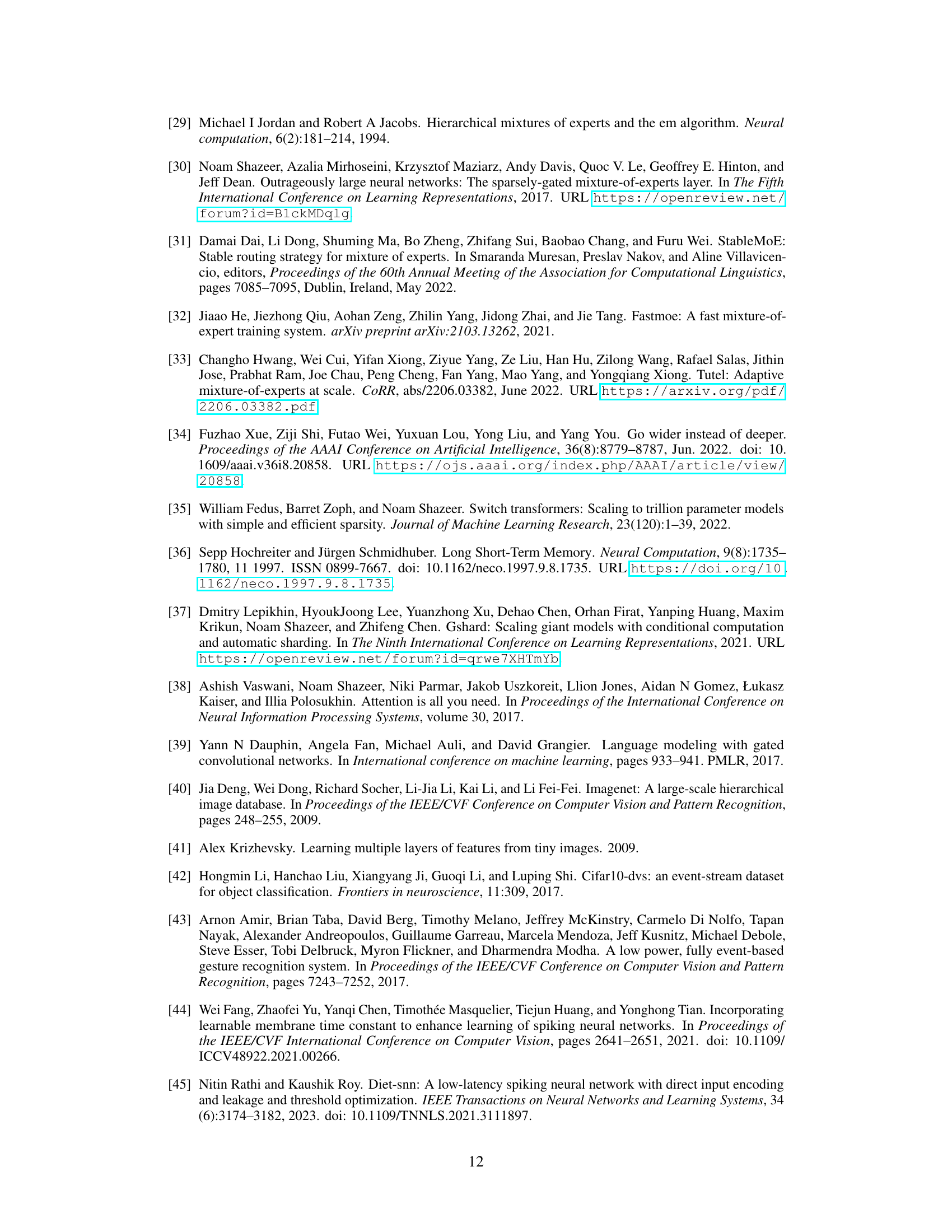

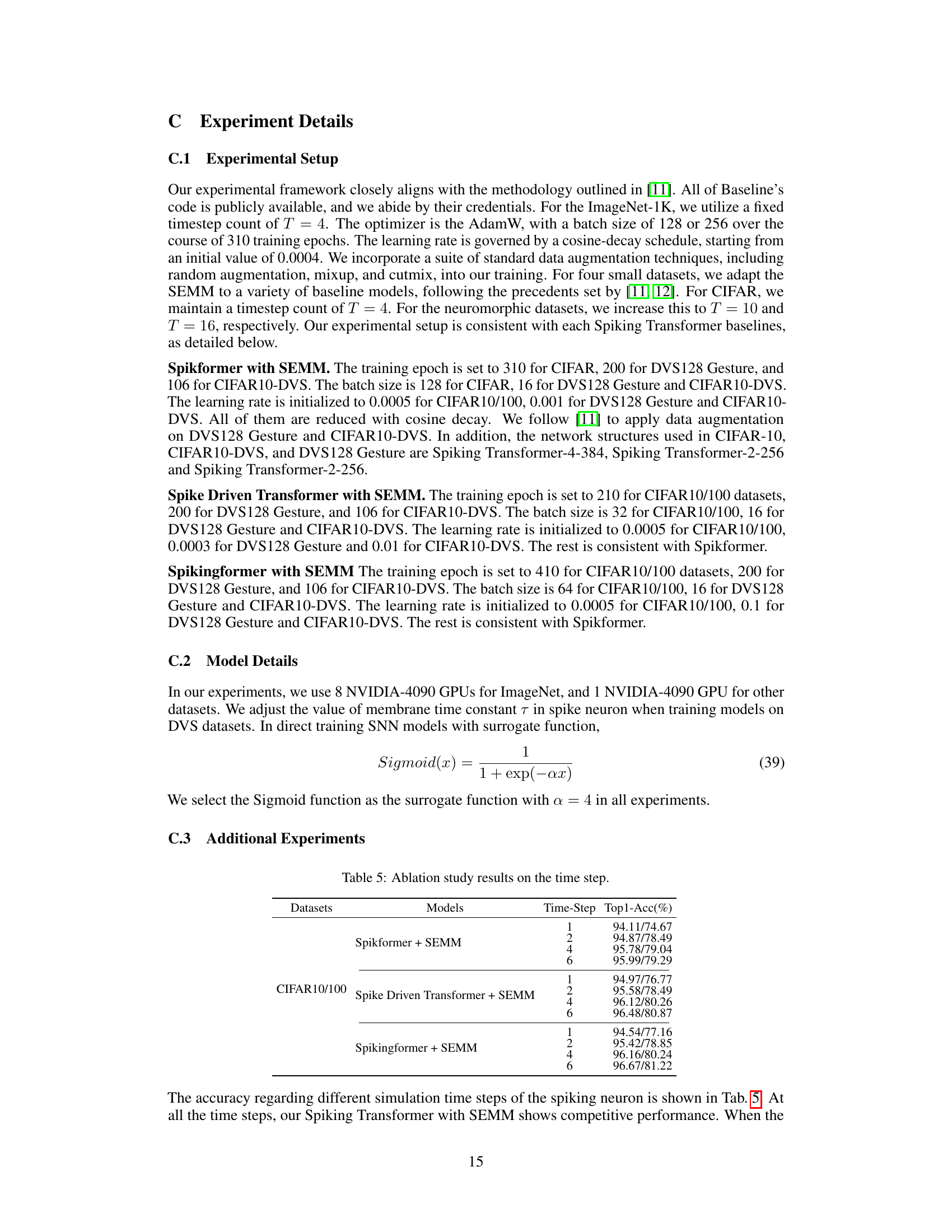

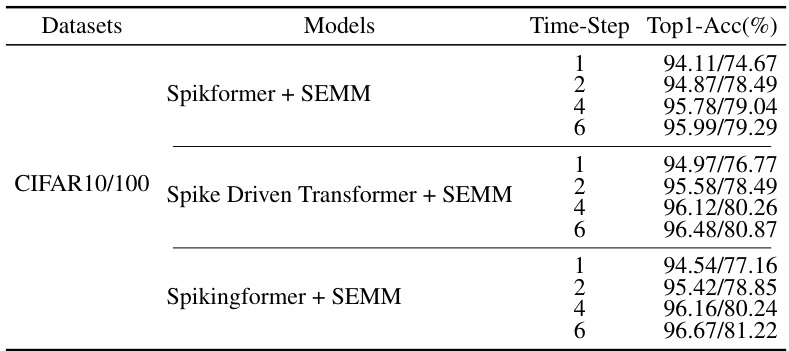

This table shows the ablation study results on the time step for three different models: Spikformer + SEMM, Spike Driven Transformer + SEMM, and Spikingformer + SEMM. It demonstrates the Top-1 accuracy achieved on the CIFAR10/100 dataset at different time steps (1, 2, 4, and 6). This helps to analyze the impact of the time step parameter on the performance of the proposed models.

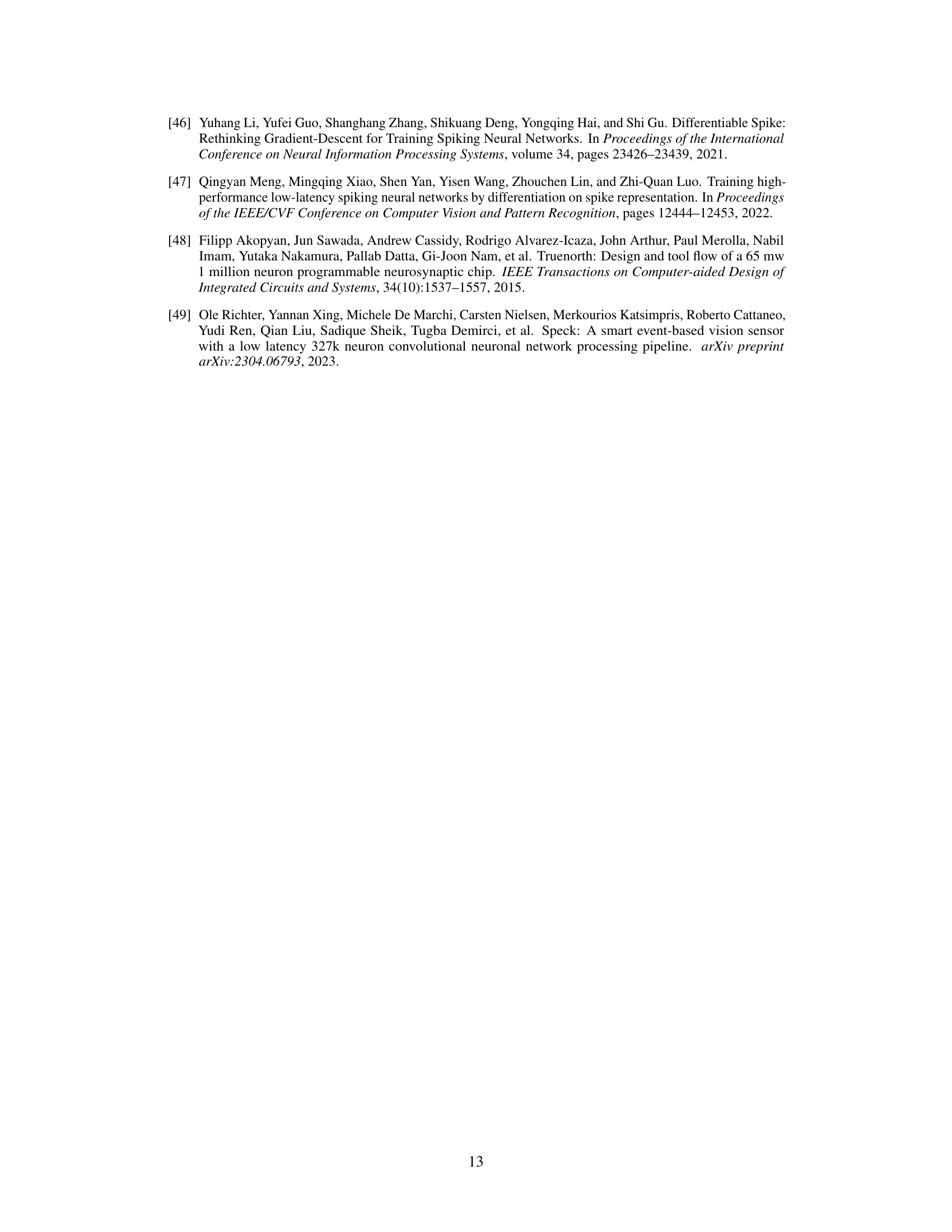

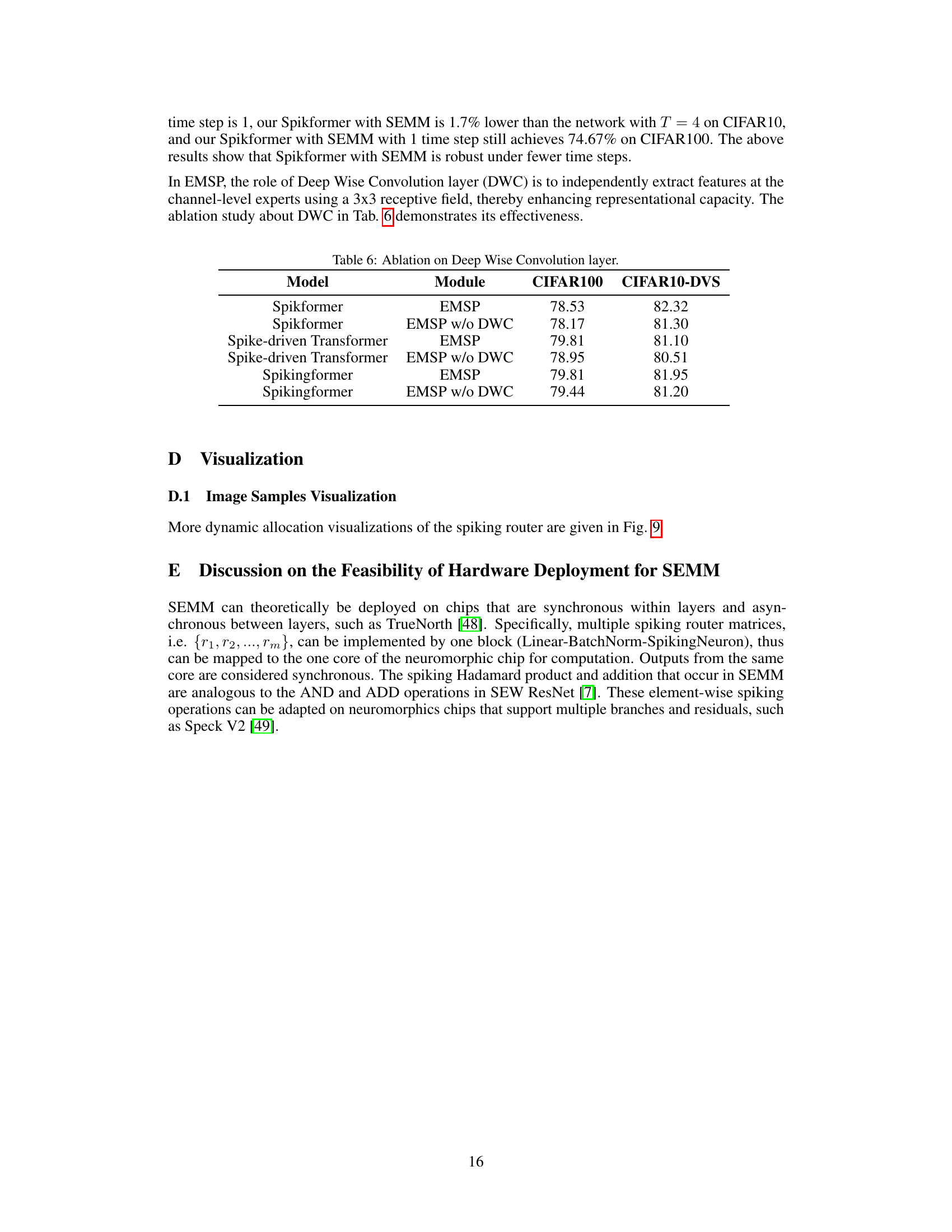

This table presents the ablation study results on the Deep Wise Convolution (DWC) layer within the Experts Mixture Spiking Perceptron (EMSP) module. It compares the performance of EMSP with and without the DWC layer across different Spiking Transformer baselines (Spikformer, Spike-driven Transformer, and Spikingformer) on CIFAR100 and CIFAR10-DVS datasets. The results show the impact of the DWC layer on the overall accuracy of the models.

Full paper#