↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

LiDAR data suffers from significant domain variations, creating “language barriers” hindering effective model generalization across different sensors and environments. This limits the scalability and applicability of LiDAR perception models in autonomous driving. Existing model-adaptation approaches are resource intensive and not easily scalable.

The LiDAR Translator (LiT) is proposed as a data-driven framework to translate LiDAR data across domains. It uses scene and LiDAR modeling to reconstruct and simulate target-domain LiDAR scans. LiT’s efficient ray-casting engine enables seamless domain adaptation and multi-domain joint learning, significantly improving zero-shot detection performance and facilitating multi-dataset joint training. This data-centric approach overcomes the limitations of model-centric methods, paving a new path for scalable LiDAR perception.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in autonomous driving and LiDAR perception. It directly addresses the critical challenge of domain adaptation in LiDAR data, a significant hurdle to scalability and widespread model deployment. By introducing a data-centric approach rather than model-centric one, the proposed LiDAR Translator (LiT) offers a novel and efficient solution. The findings can inform future research, fostering zero-shot cross-domain learning and multi-domain joint learning strategies. LiT’s impact extends to enhancing perception model robustness and generalization across diverse sensors and environments.

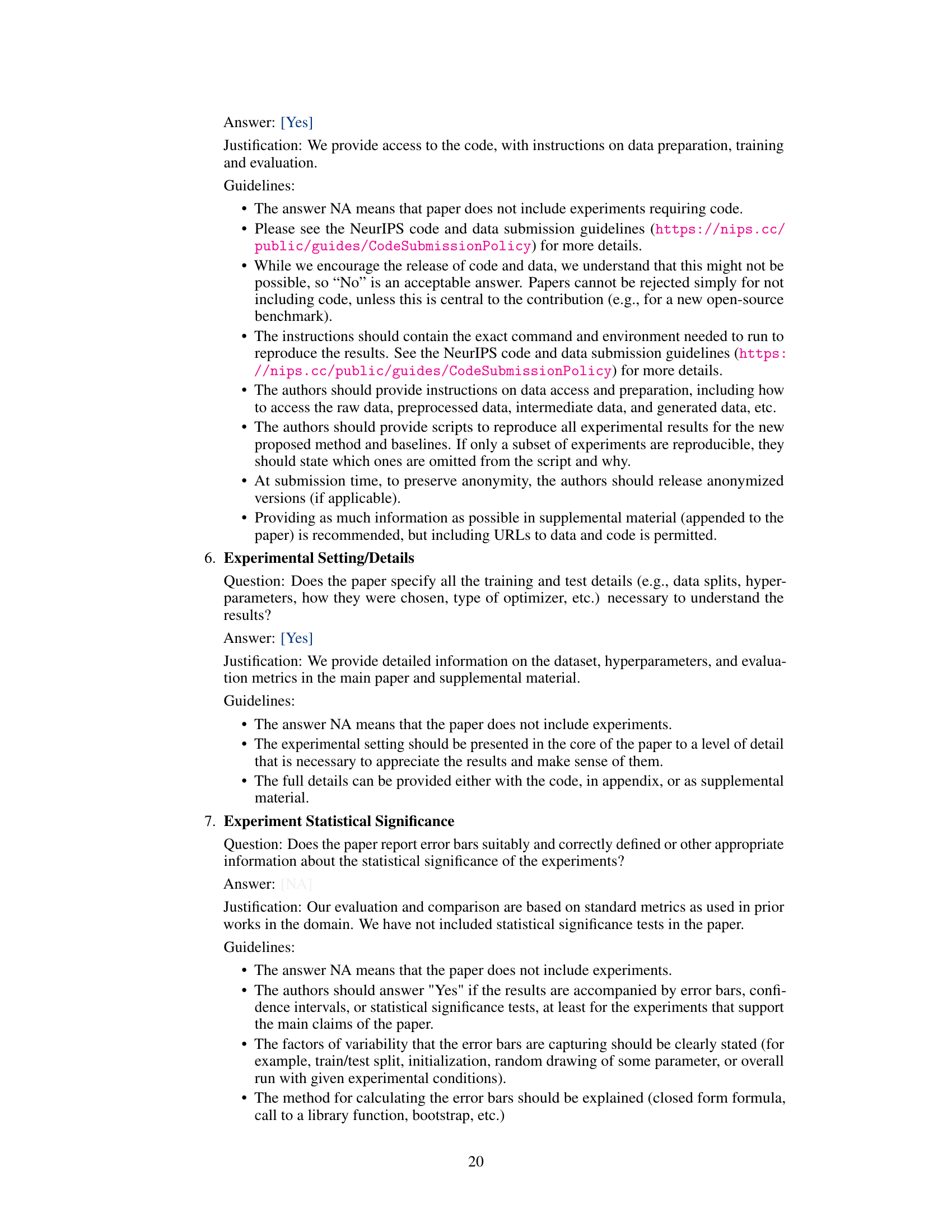

Visual Insights#

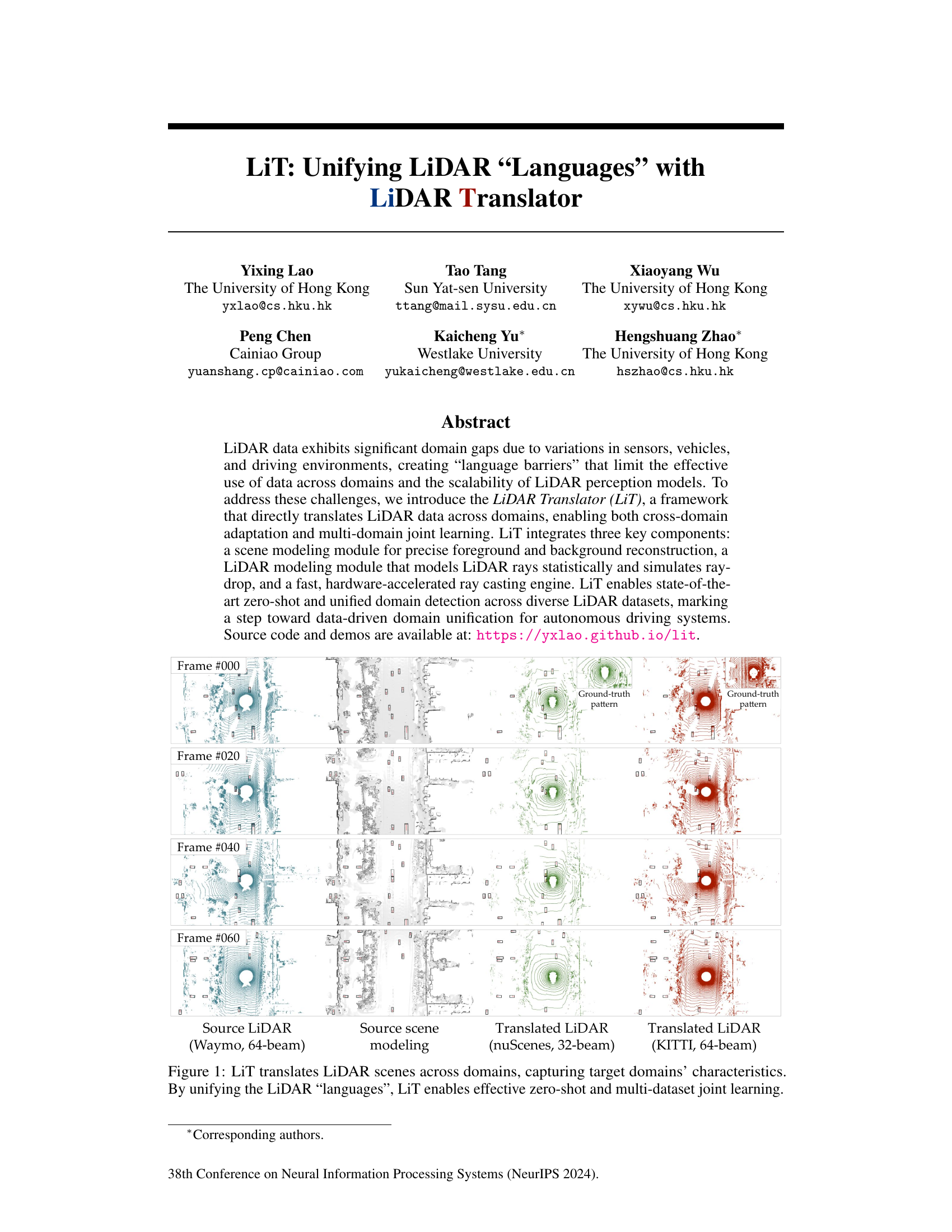

The figure shows how LiT translates LiDAR data from one domain to another. The input is a LiDAR scan from the Waymo dataset (64 beams). LiT processes this scan using a scene modeling module and a LiDAR modeling module. The output is two translated LiDAR scans: one for the nuScenes dataset (32 beams) and another for the KITTI dataset (64 beams). The figure visually demonstrates the ability of LiT to translate between different LiDAR ’languages’ and capture the unique characteristics of each target domain. This capability is crucial for enabling effective zero-shot and multi-dataset joint learning.

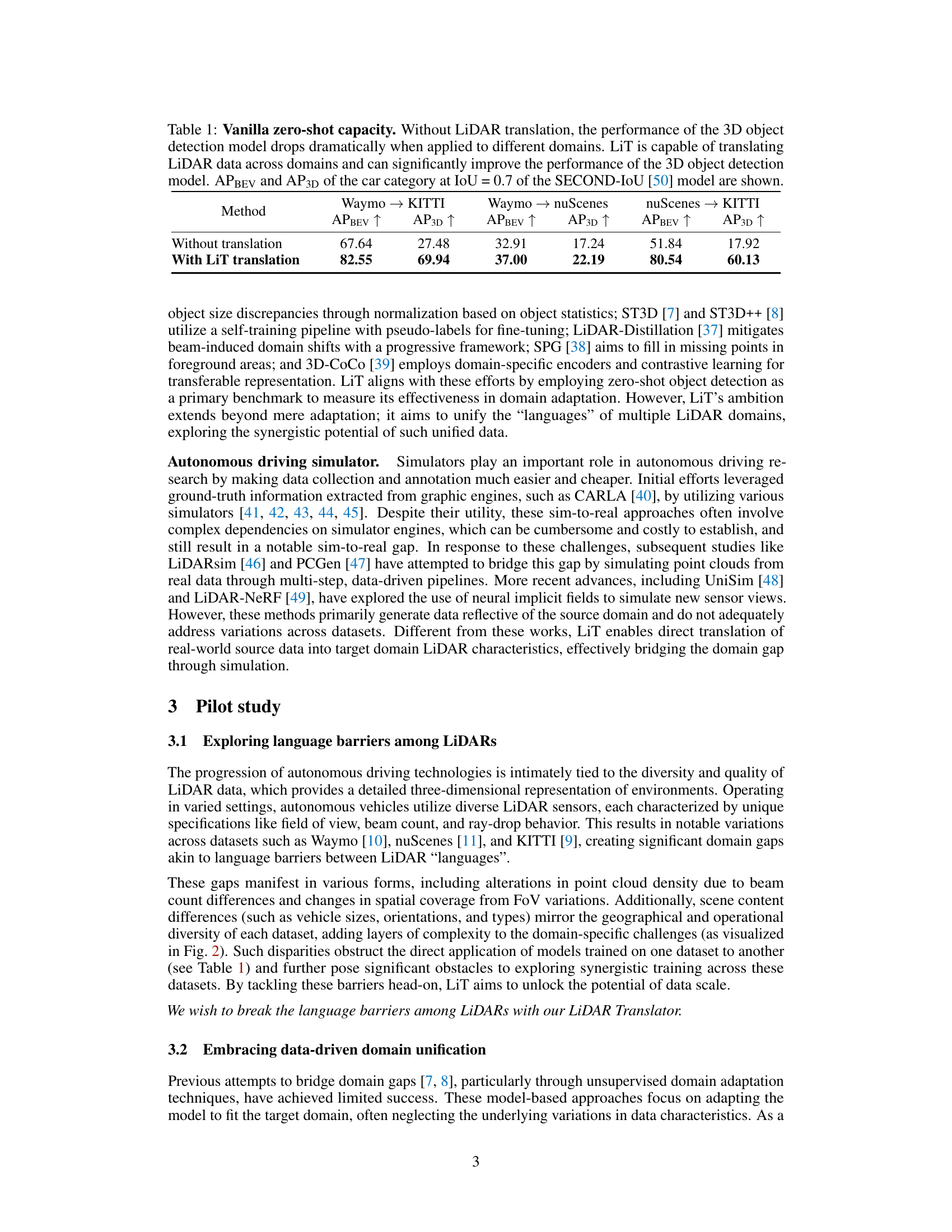

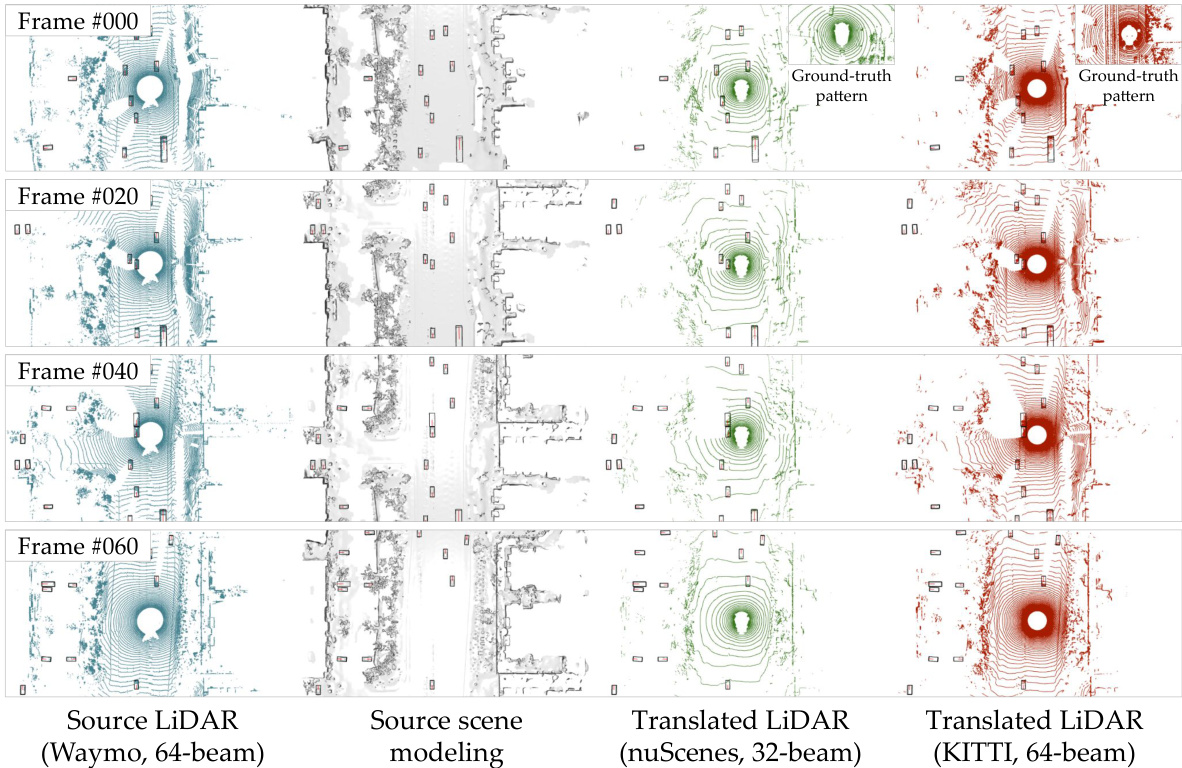

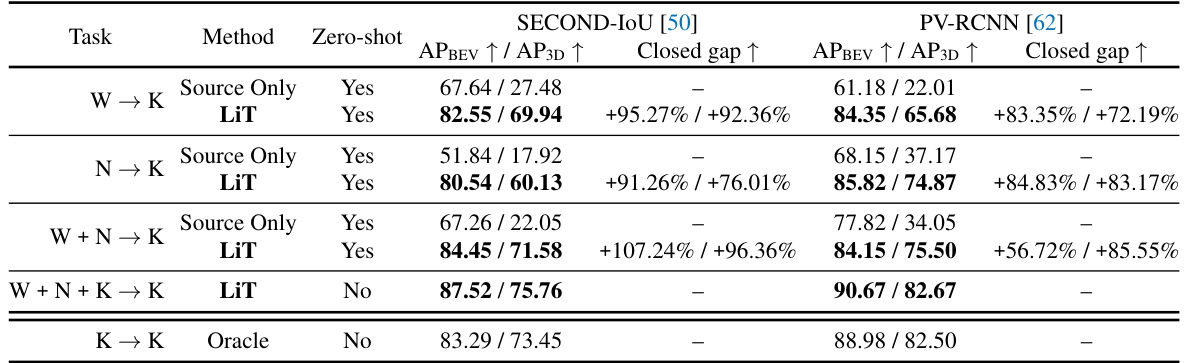

This table presents the results of a zero-shot experiment, comparing the performance of a 3D object detection model on three different LiDAR datasets (Waymo, nuScenes, and KITTI) with and without the LiDAR Translator (LiT). The results demonstrate a significant performance drop when using a model trained on one dataset and directly applied to another (without translation). In contrast, the LiT method substantially improves the performance across domains. The metrics used are Average Precision for Bird’s Eye View (APBEV) and Average Precision for 3D (AP3D), both at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.7. The SECOND-IoU model is used for the experiment.

In-depth insights#

LiDAR Language Gap#

The concept of a “LiDAR Language Gap” highlights the significant challenges in unifying data from diverse LiDAR sensors. Variations in sensor characteristics (beam count, field of view, etc.) and environmental conditions create inconsistencies in the resulting point cloud data, making it difficult for machine learning models trained on one dataset to generalize effectively to others. This is analogous to a language barrier; models trained on one “dialect” may struggle with another, hindering cross-domain adaptation and limiting the scalability of autonomous driving systems. Bridging this gap requires advanced techniques that address both the sensor-specific differences in data acquisition and the variability inherent in the driving environments. Data-centric approaches, like LiDAR translation, are crucial for creating a unified “language” that enables efficient zero-shot and multi-dataset joint learning, leading to more robust and generalized perception models.

LiT Framework#

The LiDAR Translator (LiT) framework is a novel approach to unify disparate LiDAR data by translating between different sensor modalities and environments. LiT’s core innovation is its data-driven nature, directly translating LiDAR scans, rather than adapting models, to bridge the “language barriers” between datasets. This is accomplished through three key components: a scene modeling module for precise reconstruction, a LiDAR modeling module that simulates ray-drop characteristics, and a hardware-accelerated ray casting engine. LiT enables zero-shot cross-domain adaptation and multi-dataset joint learning, unlocking significant performance gains in downstream tasks like object detection and paving the way for enhanced scalability in autonomous driving systems. The framework’s efficiency, demonstrated by sub-minute translation times, makes it particularly impactful for large-scale training initiatives. The flexibility to translate between various LiDAR configurations without requiring retraining makes it adaptable and efficient.

Zero-Shot Capacity#

Zero-shot capacity, in the context of LiDAR object detection, signifies a model’s ability to accurately identify objects in unseen domains without any prior training on those specific domains. This capability is crucial for enhancing the robustness and generalization of autonomous driving systems, which may encounter diverse environments and LiDAR sensor configurations. LiDAR Translator (LiT) directly addresses this by bridging the ’language barriers’ between different LiDAR datasets. Instead of adapting the model, LiT translates LiDAR data from various sources into a common representation, enabling zero-shot performance across different domains. The effectiveness of this data-centric approach is demonstrated through experiments, showing significant improvements in zero-shot object detection compared to model-based adaptation methods. LiT’s success stems from its meticulous modeling of both scene characteristics and sensor specifics, thus producing realistically translated LiDAR data suitable for training and testing in diverse and unseen environments. This approach showcases the power of data unification for robust autonomous perception.

Multi-Domain Learning#

Multi-domain learning in the context of LiDAR data aims to overcome the limitations of models trained on a single domain by leveraging data from multiple domains. This approach is particularly relevant to LiDAR perception due to significant variations in sensor characteristics and driving environments across different datasets. The core challenge is bridging the “language barriers” between datasets, where differing sensor specifications and environmental conditions create inconsistencies in the data that hinder model generalizability. Successful multi-domain learning strategies should focus on data harmonization techniques, such as LiDAR translation, which aims to convert data from disparate sources into a unified representation. This allows models to learn shared features and improve their ability to generalize to unseen domains. Furthermore, a robust multi-domain learning approach must address challenges like data imbalance and domain shift. Efficient methods are needed to combine data from diverse sources, ensuring that biases from individual domains do not overwhelm the learning process. The ultimate goal is to improve the scalability and robustness of LiDAR perception models, leading to more reliable and safe autonomous driving systems.

LiDAR Simulation#

LiDAR simulation plays a crucial role in autonomous driving research by synthetically generating LiDAR data, which is valuable for training and testing perception models. Simulating LiDAR data offers several advantages, including cost-effectiveness, the ability to control various parameters (weather conditions, object properties, sensor noise), and the potential for data augmentation. However, achieving realism in LiDAR simulation remains a challenge. Effective LiDAR simulation requires accurate scene modeling, precise sensor modeling including ray tracing and drop, and consideration of environmental factors. Different simulation techniques exist (e.g., physics-based, data-driven), each with its strengths and limitations. The choice of simulation method depends on the specific application and available resources. The fidelity of LiDAR simulation is particularly crucial for ensuring the robustness and generalizability of autonomous driving systems trained on simulated data. Therefore, ongoing research is needed to improve the realism and efficiency of LiDAR simulation techniques.

More visual insights#

More on figures

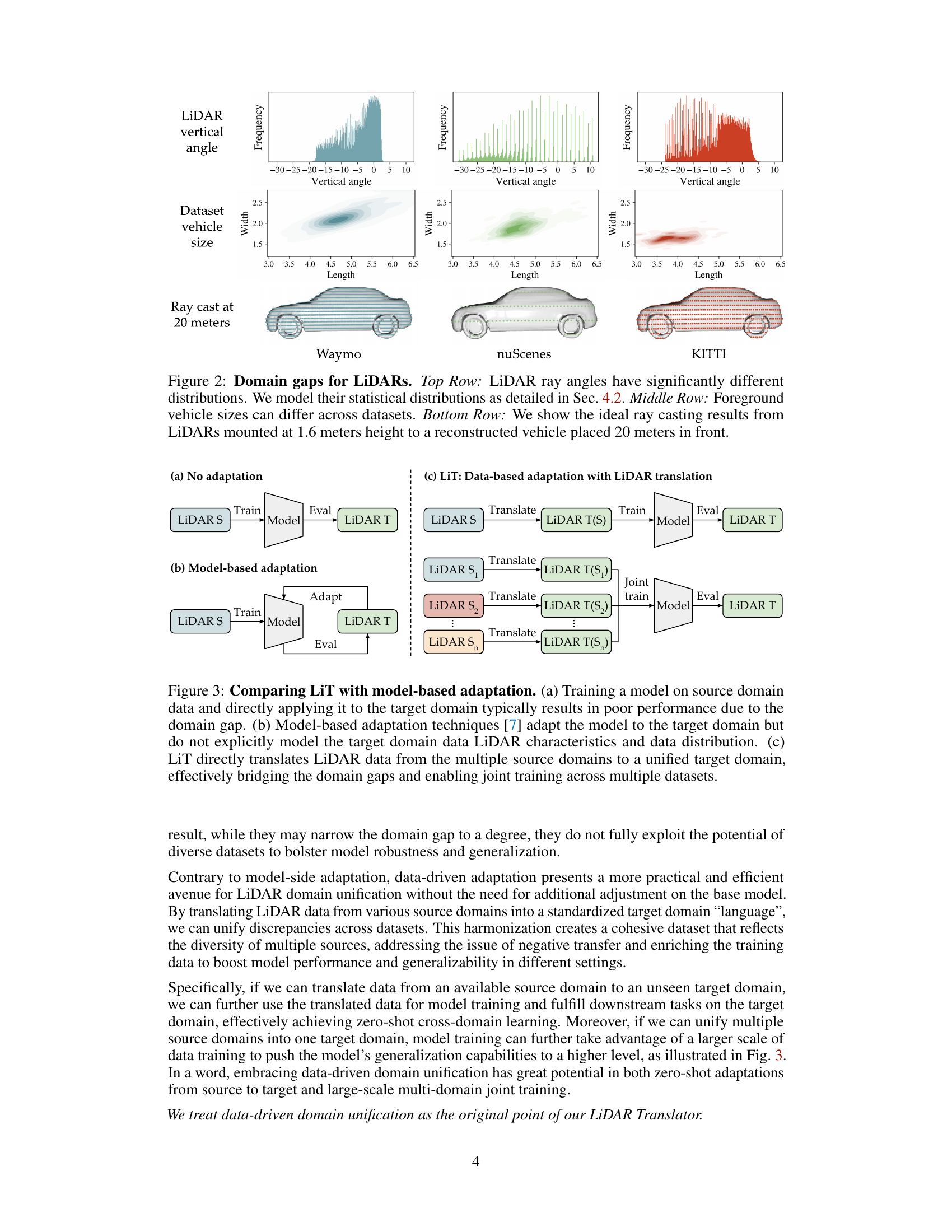

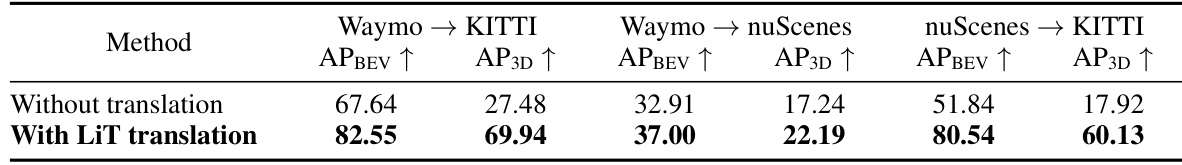

This figure shows the differences in LiDAR data characteristics across different datasets (Waymo, nuScenes, KITTI). The top row illustrates the varying distributions of LiDAR ray angles. The middle row highlights the differences in vehicle size distributions. The bottom row visually depicts how these differences affect the ray casting results when reconstructing a vehicle from 20 meters away, showing variations in point cloud density and coverage.

This figure compares three different approaches for LiDAR data adaptation: (a) No adaptation, where a model trained on source domain data is directly applied to the target domain, leading to poor performance due to the domain gap. (b) Model-based adaptation, where techniques like ST3D [7] adapt the model to the target domain but don’t explicitly model its characteristics. (c) LiDAR Translator (LiT), which translates LiDAR data from multiple source domains to a unified target domain, bridging the gap and enabling joint training.

This figure shows the pipeline of LiDAR translator (LiT). The pipeline consists of three main stages. First, scene modeling which uses multi-frame LiDAR scans to reconstruct the foreground and background of the scene. Second, LiDAR modeling which simulates the target domain’s LiDAR sensor model to generate LiDAR scans based on the reconstructed scene from the previous stage. Finally, a GPU-accelerated ray casting engine is used to generate the translated LiDAR scans that are faithful to the target domain’s LiDAR sensor’s characteristics. The whole process is fast and takes less than a minute to translate a multi-frame LiDAR scene.

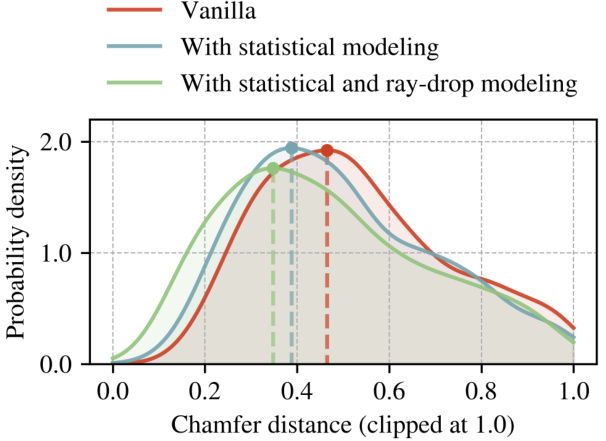

This figure compares the Chamfer distance between real and simulated LiDAR data on the nuScenes dataset. The Chamfer distance measures the difference between point clouds. The results show that incorporating both statistical ray angle modeling and ray-drop modeling into LiDAR simulation significantly improves the accuracy of the simulated data, bringing it closer to the real-world data.

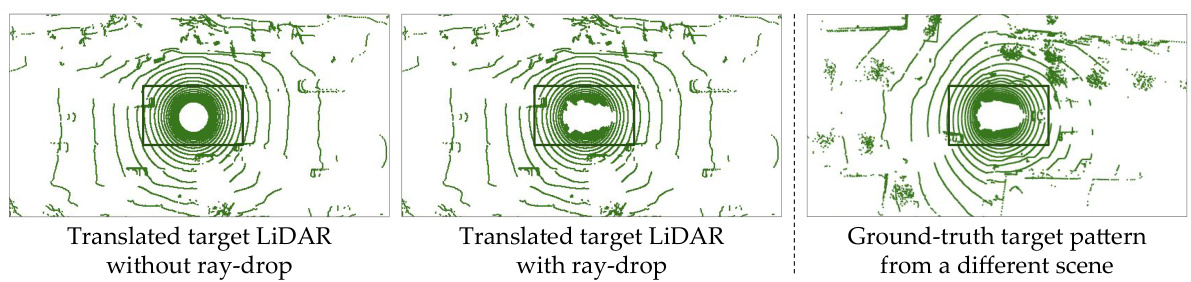

This figure demonstrates the effect of LiDAR ray-drop modeling in LiT. The left panel shows a translated LiDAR scan without ray-drop modeling, exhibiting a dense circular pattern near the vehicle. The center panel displays the same scan but with ray-drop modeling applied; it shows sparser points near the vehicle, closely mimicking the patterns observed in real nuScenes scans. The right panel is a ground truth nuScenes scan from a different scene, providing a comparison to highlight the improved realism with ray-drop modeling.

This figure demonstrates the flexibility of LiT in applying translated LiDAR data to new scenes, even those not explicitly modeled within LiT. It showcases four columns; the first shows a synthetic Mai City scene, while the subsequent three columns illustrate LiT-simulated LiDAR scans (in nuScenes style) tracking a moving vehicle within the same scene. This highlights LiT’s capacity to adapt and integrate with diverse sources of scene reconstruction, highlighting its real-world applicability.

This figure visualizes the foreground modeling process of LiT. It shows how LiT takes multiple LiDAR scans of a vehicle from different viewpoints and fuses them to create a complete 3D mesh of the vehicle. This mesh is then used to generate synthetic LiDAR scans in the target domain. The figure displays three examples of this process, illustrating the input LiDAR point clouds, intermediate steps, and the final reconstructed mesh for each example.

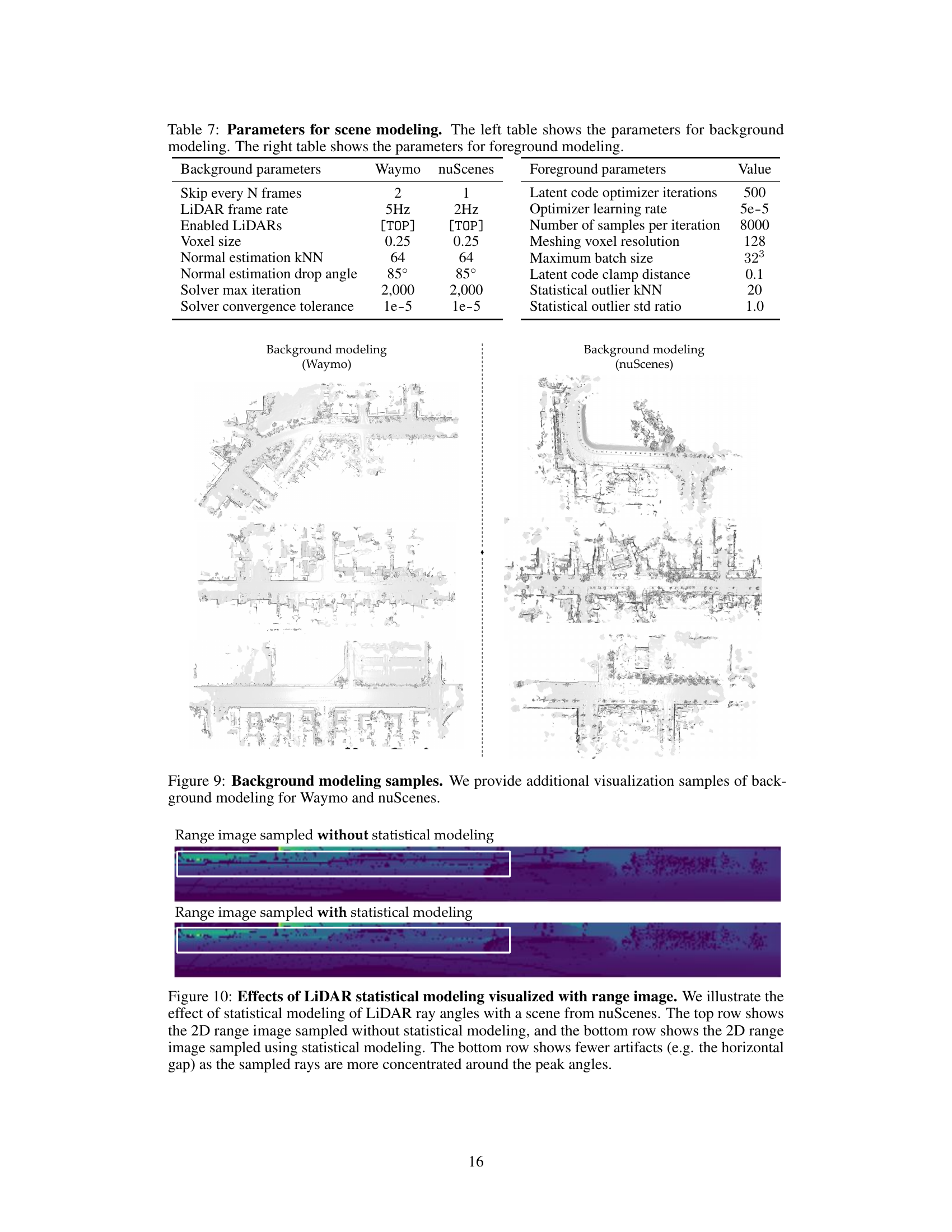

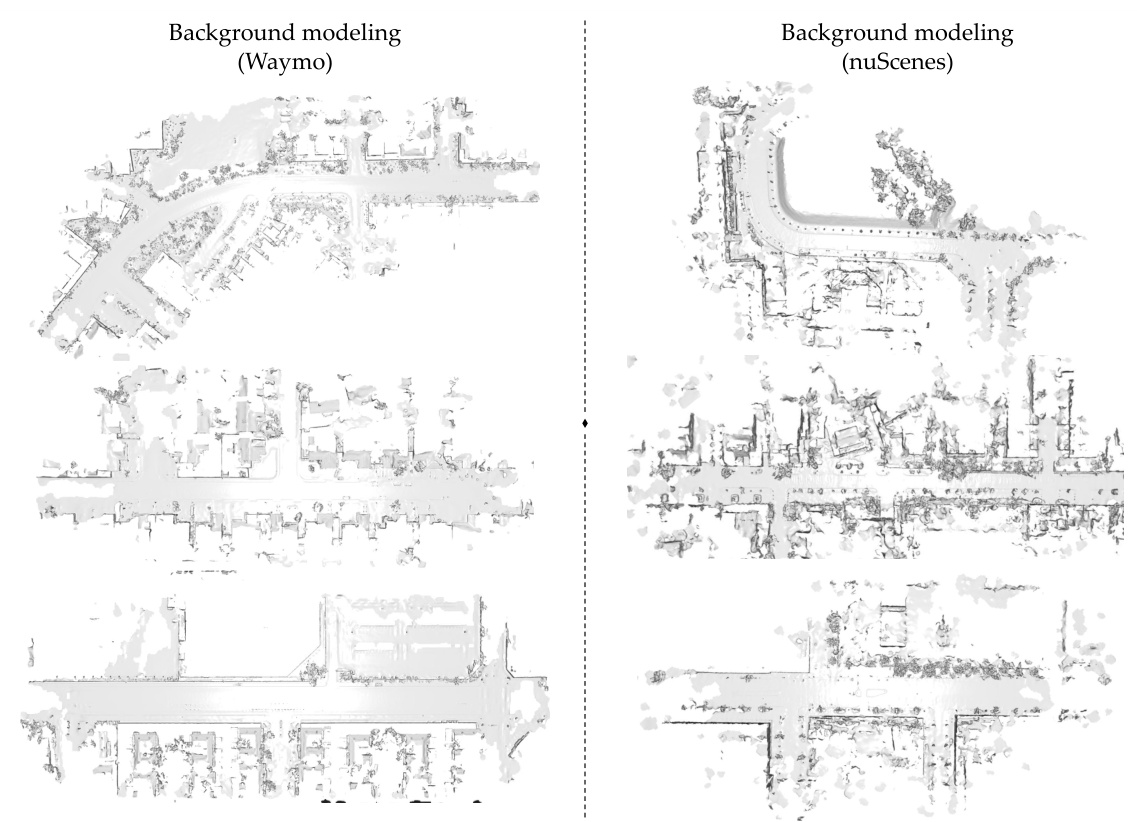

This figure shows visualization samples of background modeling for Waymo and nuScenes datasets. It visually demonstrates the reconstruction of the background scene using LiT’s approach. The top and bottom rows present the reconstructed scenes from two different perspectives for both datasets, allowing for a comparison of the results. The reconstruction quality visually highlights the effectiveness of LiT in capturing background details.

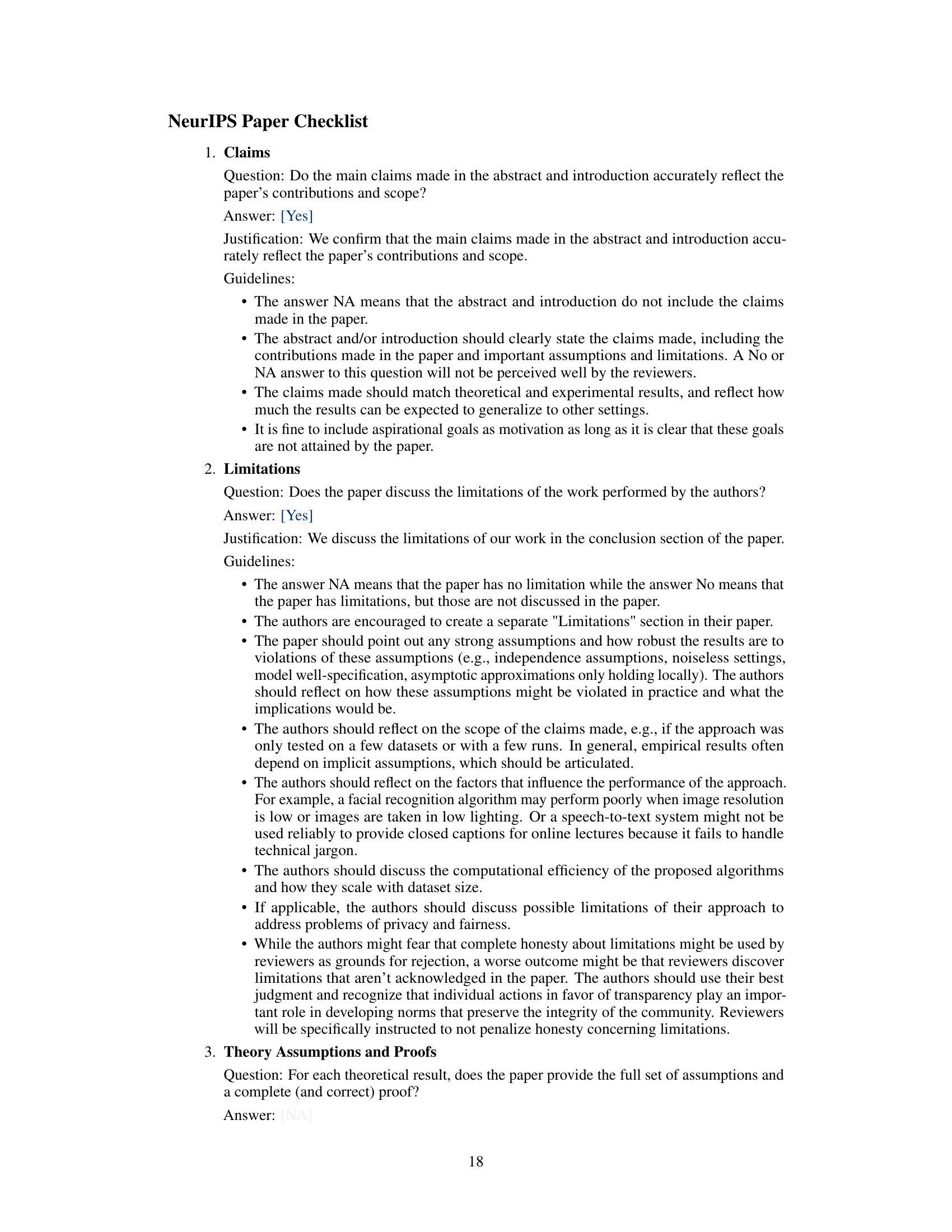

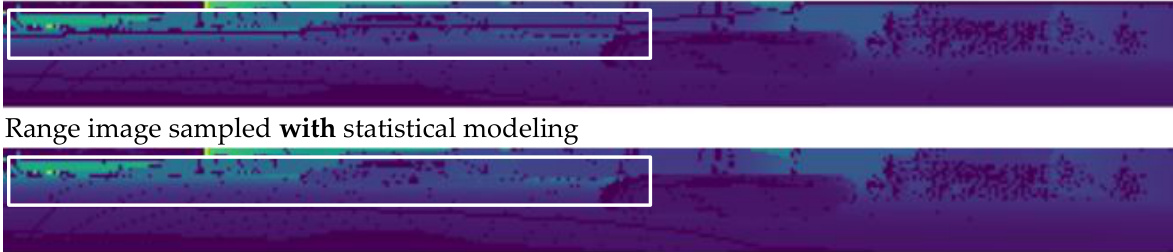

This figure compares 2D range images from the nuScenes dataset. The top image shows the results without LiDAR statistical modeling applied, which shows artifacts like a horizontal gap. The bottom image shows the results with LiDAR statistical modeling applied. The modeling helps to correct artifacts by concentrating the sampled rays around the peak angles.

The figure shows four LiDAR point cloud frames. The top-left frame is the original LiDAR data from Waymo with 64 beams. The other three frames are the translated LiDAR data to nuScenes (32 beams) and KITTI (64 beams), showing how LiT translates LiDAR data between different domains while preserving the essential characteristics of the target domains.

More on tables

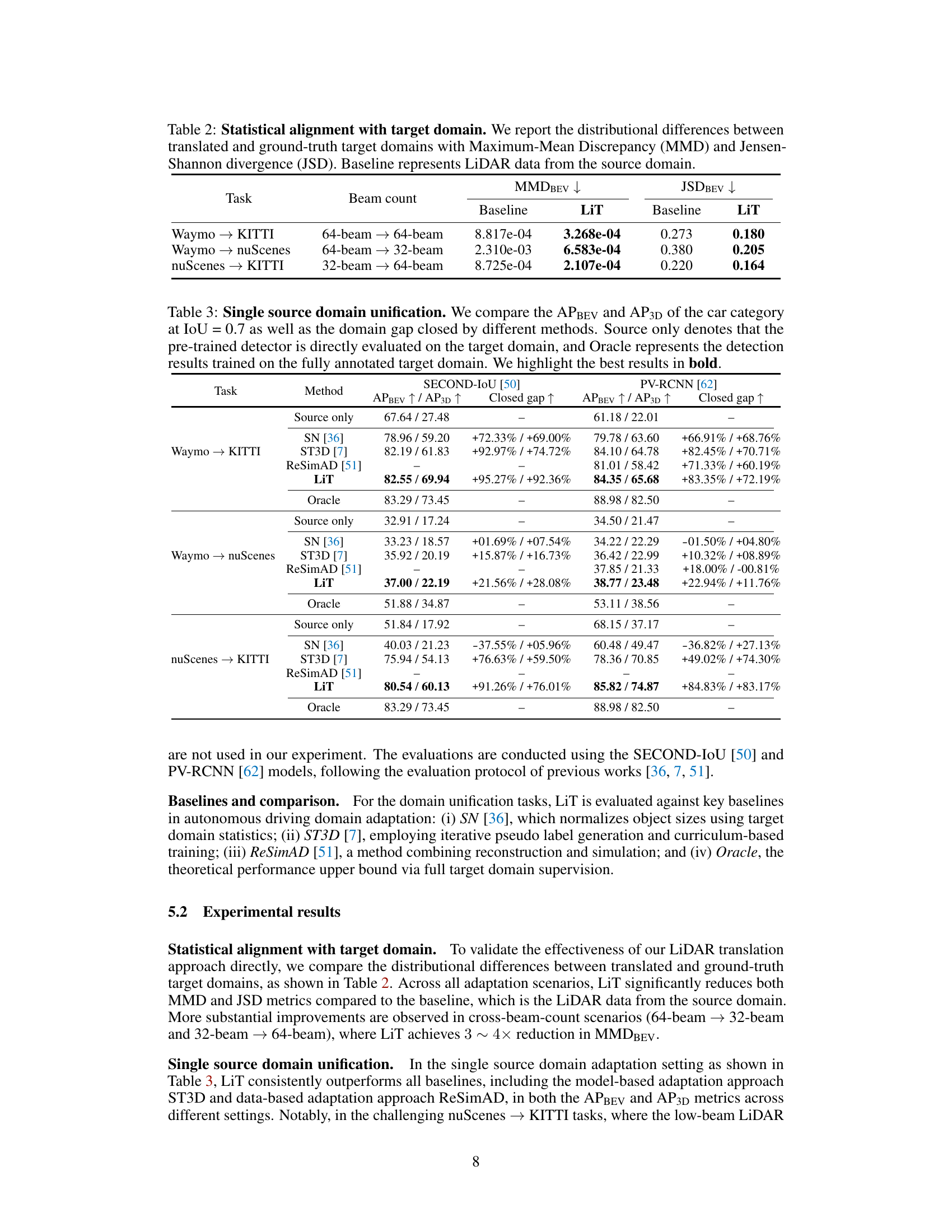

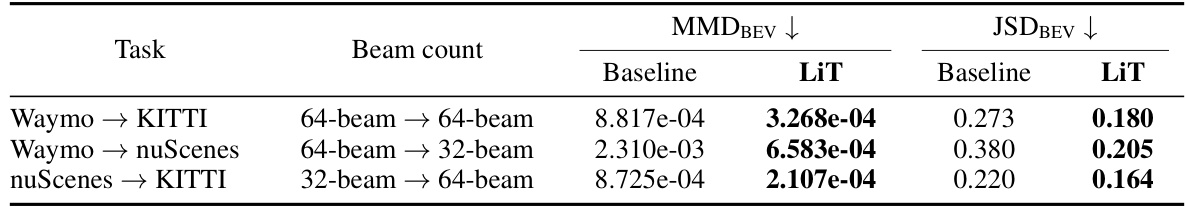

This table presents a quantitative evaluation of how well LiT aligns the statistical distribution of translated LiDAR data with the ground truth target domain. It compares the Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) and Jensen-Shannon Divergence (JSD) for three different LiDAR data translation tasks. The baseline represents the distributional differences using the original source domain LiDAR data without any translation. The lower values for LiT in both MMD and JSD demonstrate that LiT effectively translates the LiDAR data to match the target domain characteristics.

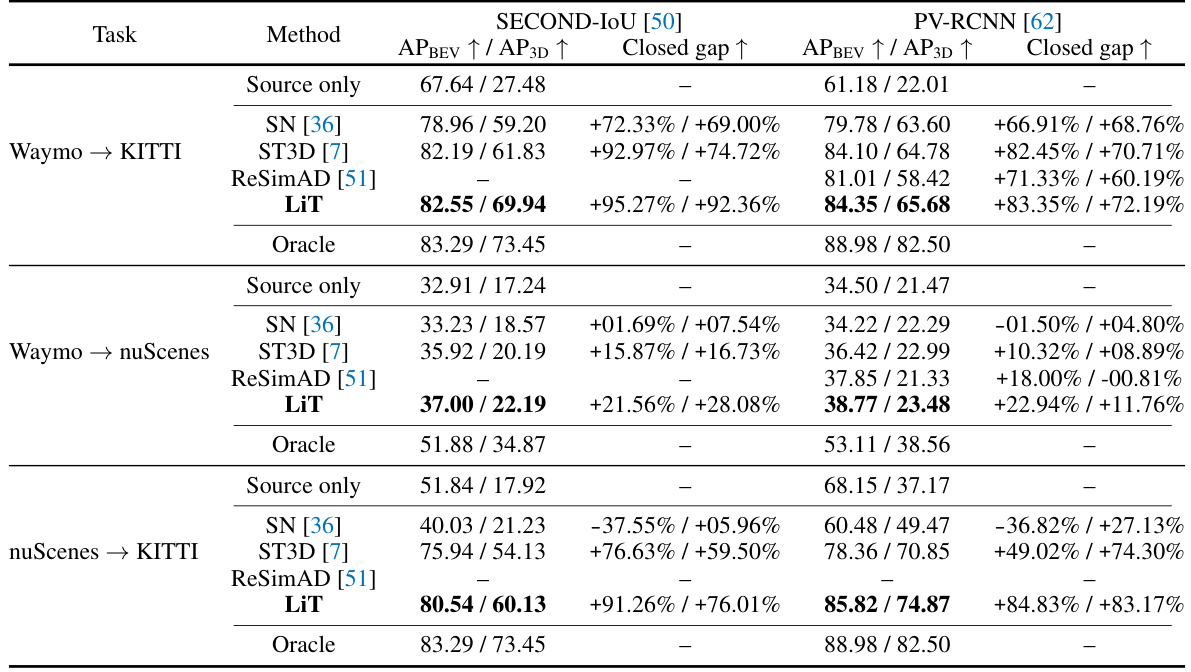

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different methods for single-source domain adaptation in 3D object detection. It compares the Average Precision (AP) in Bird’s Eye View (BEV) and 3D for the ‘car’ category, using an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.7. The methods compared include a baseline of using the source-only trained model on the target domain, SN [36], ST3D [7], ReSimAD [51], and the proposed LiDAR Translator (LiT). An ‘Oracle’ result is also given, representing the performance achievable with a model fully trained on the target domain’s annotated data. The table highlights the best performing methods for each task, indicating the effectiveness of each approach in bridging domain gaps and improving object detection performance. The ‘Closed gap’ column shows the percentage increase in performance compared to the source only method.

This table compares the performance of different methods for single-source domain adaptation in 3D object detection. It shows the Average Precision (AP) for Bird’s Eye View (BEV) and 3D object detection, along with the percentage improvement achieved by each method compared to a baseline (Source Only) and the performance of a model trained on fully annotated data (Oracle). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the LiDAR Translator (LiT) method in bridging domain gaps across different LiDAR datasets.

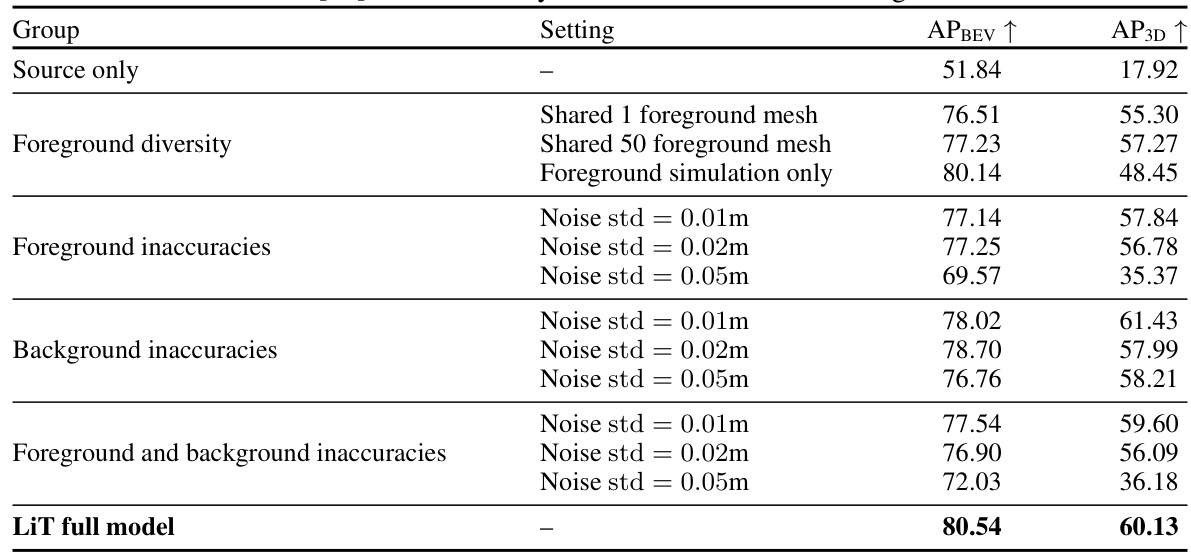

This table presents the ablation study of LiDAR translator (LiT) on the nuScenes to KITTI translation task using the SECOND-IoU model. It systematically investigates the impact of different components and choices within the LiT framework on the final performance. The rows show various configurations, including: using only source data without adaptation, variations in foreground modeling (diversity and noise levels), background noise, and the full LiT model. The columns indicate the Average Precision (AP) for Bird’s Eye View (BEV) and 3D object detection.

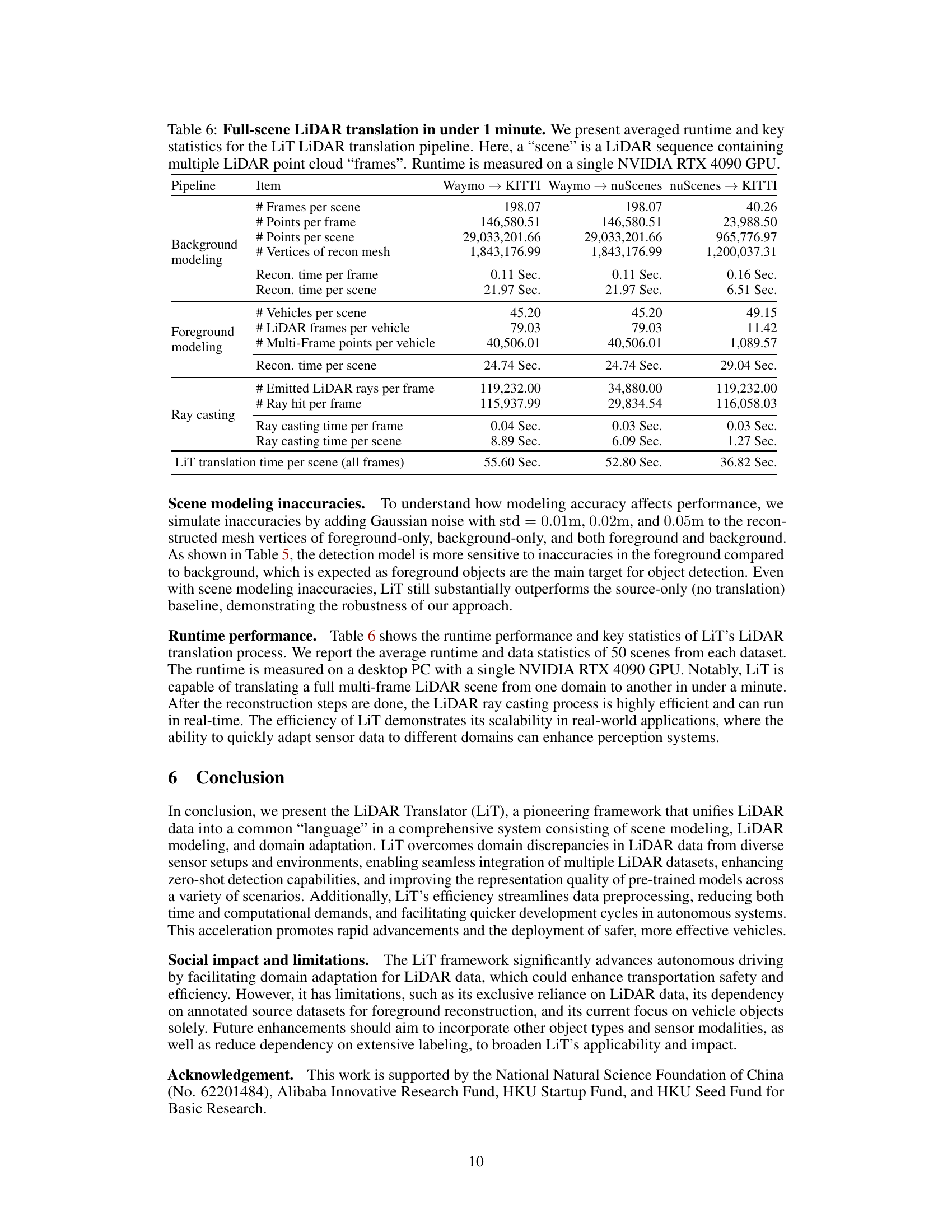

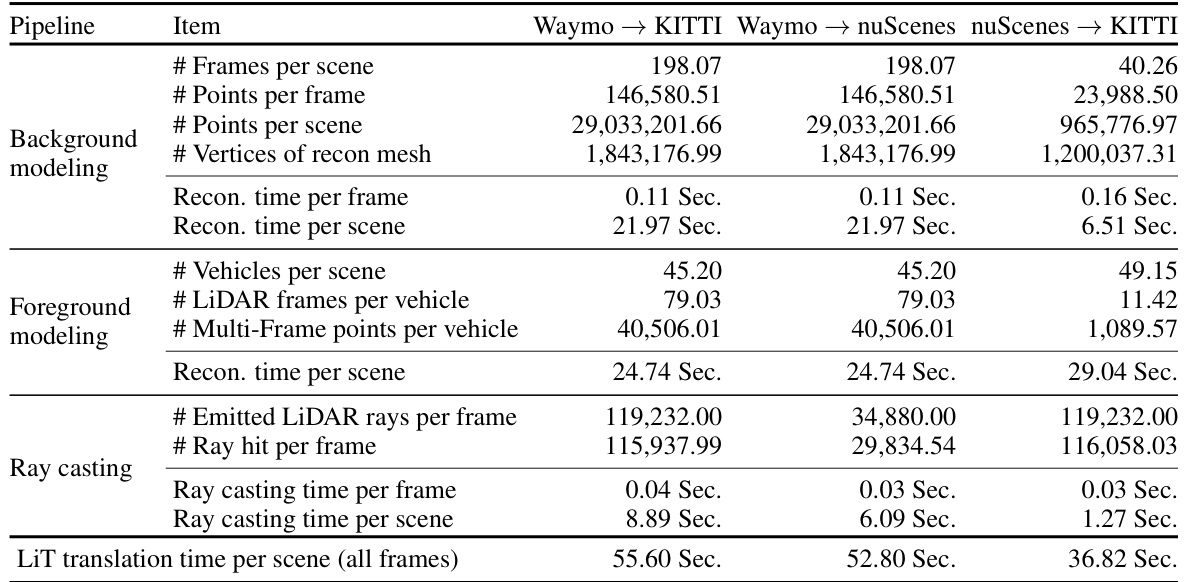

This table presents the runtime statistics and key metrics of the LiT LiDAR translation pipeline for three different domain translation tasks (Waymo → KITTI, Waymo → nuScenes, and nuScenes → KITTI). It breaks down the time spent on different stages of the pipeline (background modeling, foreground modeling, and ray casting) and provides metrics like the number of frames, points, vertices, and rays involved in each process. The table shows LiT’s efficiency in translating a full multi-frame LiDAR scene (around 200 frames) in under a minute.

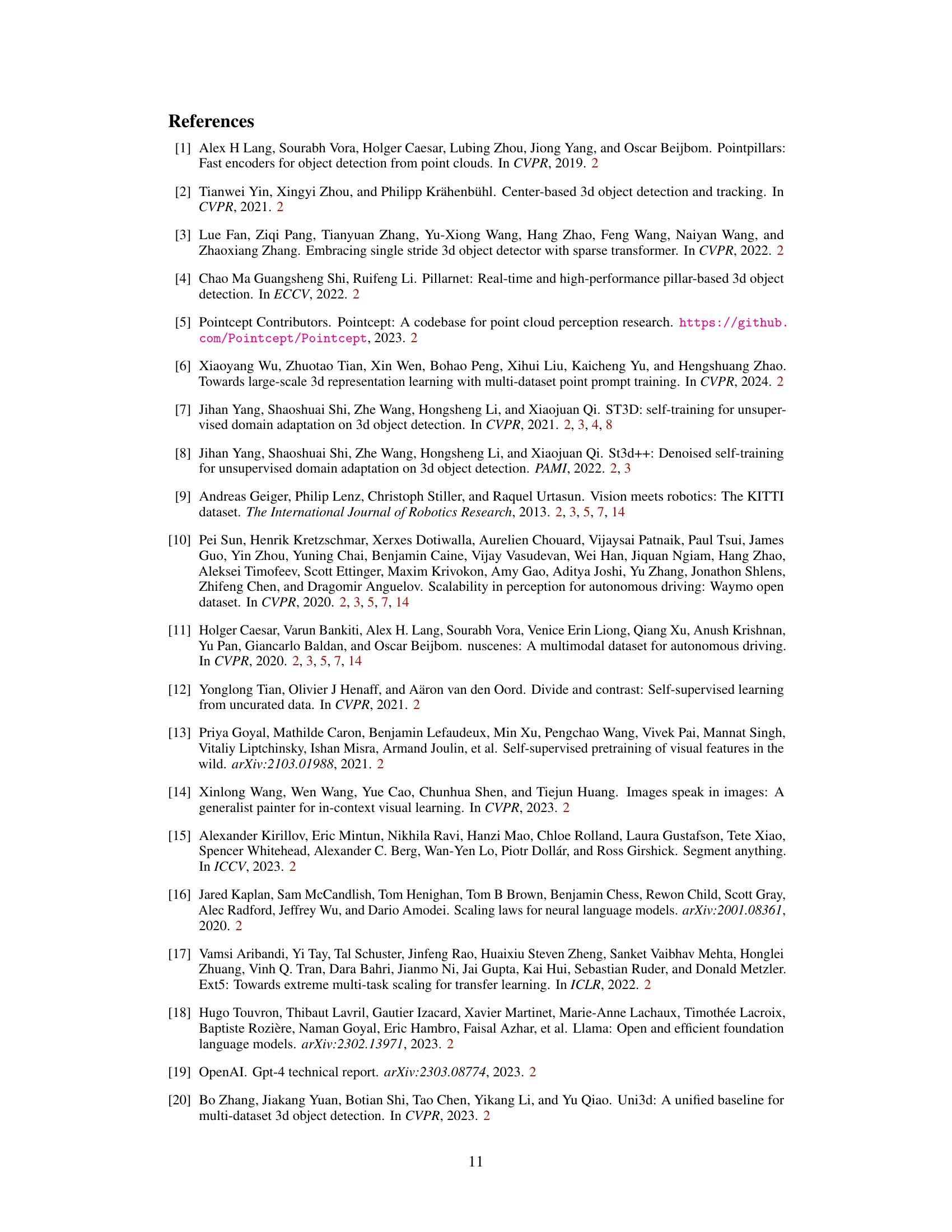

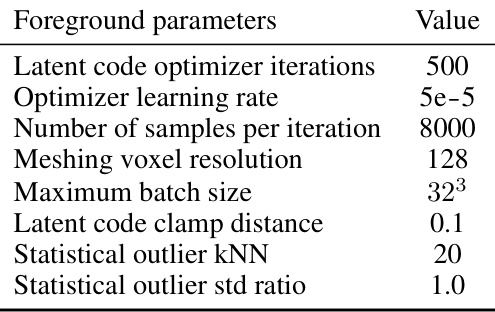

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the scene modeling part of the LiDAR translator. It shows separate parameters for the background and foreground modeling components, including settings relevant to voxel size, normal estimation, solver iterations, and convergence tolerance, for both Waymo and nuScenes datasets. These parameters control how accurately the scene is reconstructed. The difference in parameters between Waymo and nuScenes reflects the different characteristics of the datasets.

This table presents a quantitative evaluation of LiDAR Translator’s (LiT) ability to statistically align translated LiDAR data with the ground truth target domain. It uses two metrics: Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) and Jensen-Shannon Divergence (JSD), computed in the Bird’s Eye View (BEV) voxel occupancy. The comparison is made between LiT’s translated data and the actual target domain LiDAR data for three different scenarios: Waymo to KITTI, Waymo to nuScenes, and nuScenes to KITTI. Lower MMD and JSD values indicate better alignment.

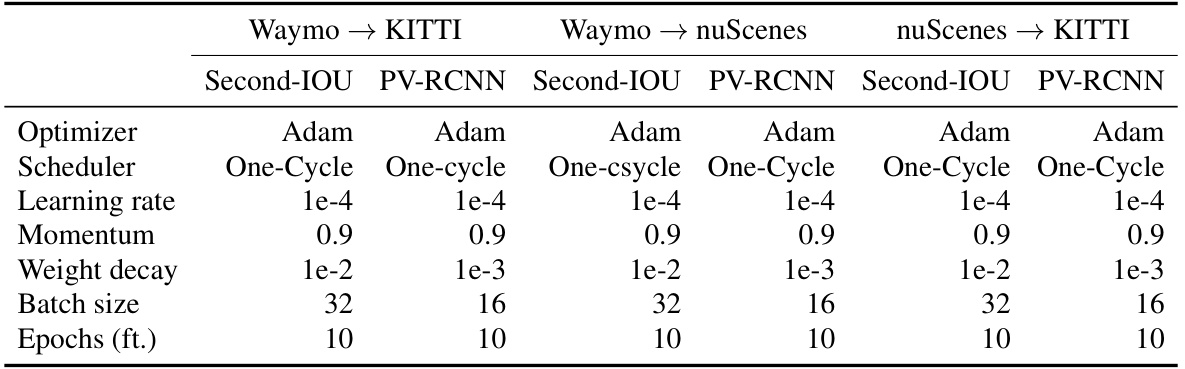

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training object detection models in single-source domain adaptation experiments using the LiDAR Translator (LiT). It covers two different models (Second-IOU and PV-RCNN) across three different domain adaptation scenarios: Waymo to KITTI, Waymo to nuScenes, and nuScenes to KITTI. For each scenario and model, the table specifies the optimizer, scheduler, learning rate, momentum, weight decay, batch size, and number of training epochs.

Full paper#