↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

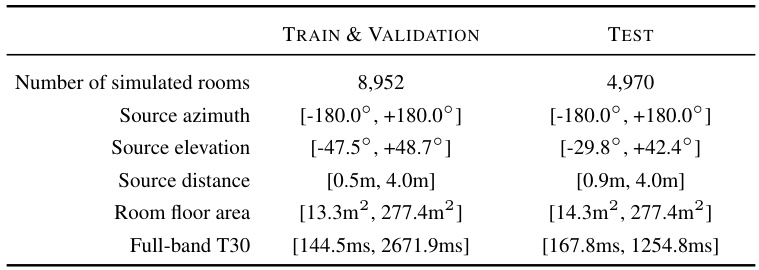

Current audio foundation models lack spatial awareness, while sound localization models are limited to recognizing predefined classes. This paper presents ELSA, a spatially aware model trained using contrastive learning on a new synthetic dataset of 4738.55 hours of spatial audio with captions. This dataset includes simulated rooms with varying properties like reverberation and size, along with source locations described in natural language.

ELSA’s architecture consists of separate encoders for spatial and semantic audio attributes, which are then combined and aligned with text embeddings using contrastive learning. The results show ELSA significantly improves over existing state-of-the-art models in 3D source localization and semantic retrieval tasks, showcasing the effectiveness of combining spatial and semantic audio information with text. The model’s structured representation space is demonstrated through the ability to swap the direction of an audio sound through vector manipulation of text embeddings.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in audio and language processing because it introduces a novel approach to combine spatial and semantic audio information with natural language, addressing a critical gap in current models. The released dataset and model will be valuable resources for the community, fostering further innovations in multimodal learning and applications like language-guided audio editing.

Visual Insights#

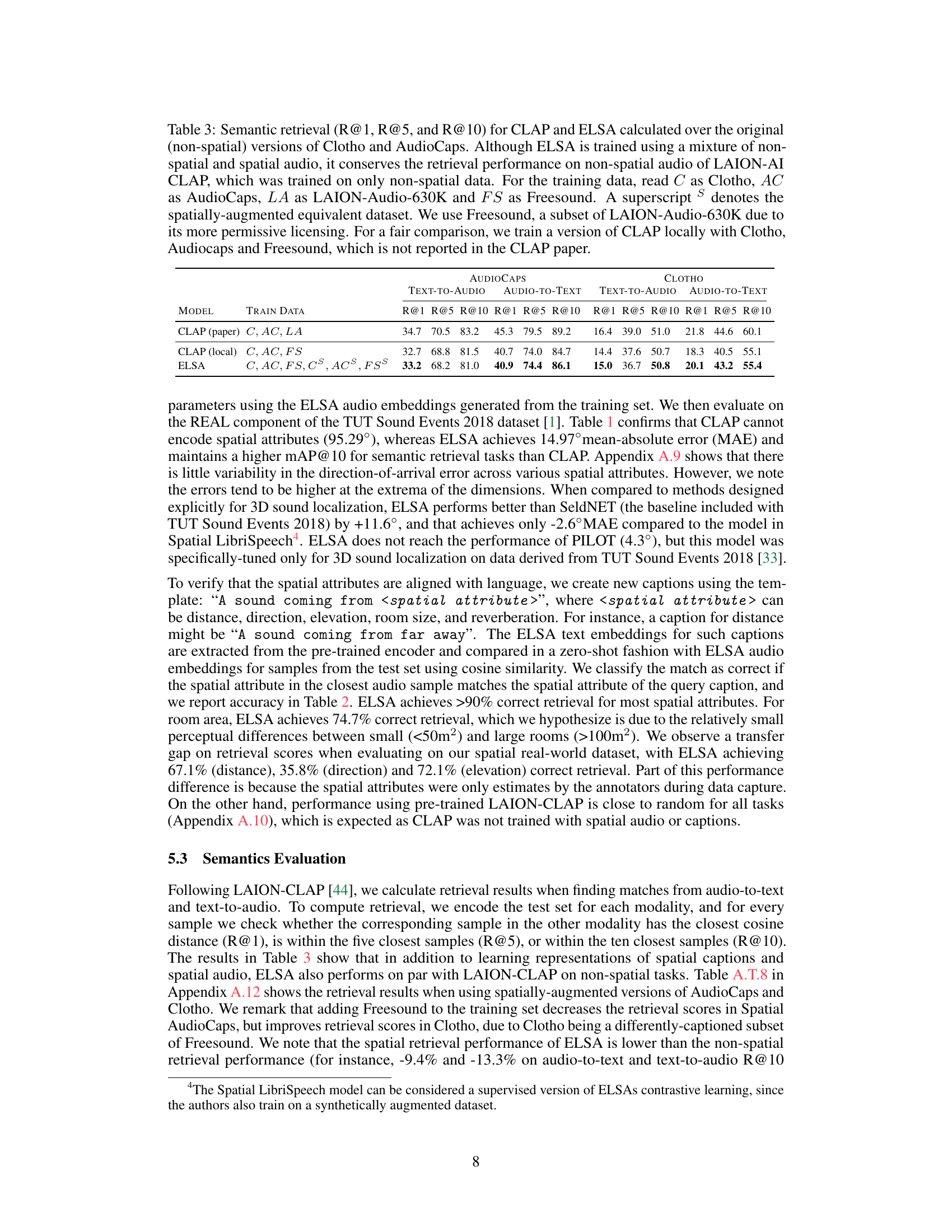

The figure shows the pipeline used for creating a dataset of spatial audio and corresponding natural language captions. First, spatial audio is simulated using different room properties and source locations (a). Then, the original captions are augmented with this spatial information, and a large language model (LLM) rewrites the captions to better align with the spatial attributes of the audio (b). Finally, the augmented captions and audio are encoded and aligned using a contrastive learning objective (c).

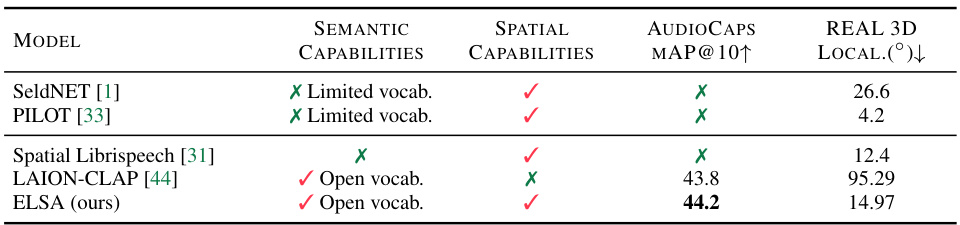

This table compares the performance of several models on two tasks: semantic caption retrieval (using the AudioCaps dataset) and 3D sound localization (using the REAL component of the TUT Sound Events 2018 dataset). It highlights that ELSA, unlike other models, handles both open vocabulary language understanding and spatial localization, achieving competitive results on both tasks.

In-depth insights#

Spatial Audio Encoding#

Spatial audio encoding is crucial for representing three-dimensional sound in a way that computers can understand. The choice of encoding method significantly impacts computational efficiency, realism, and the types of spatial audio processing that are possible. First-Order Ambisonics (FOA), a popular method, offers a good balance between spatial resolution and computational cost. While FOA excels in its relatively simple representation and the ease of linear transformation into other formats like binaural audio, it has limitations, such as reduced spatial resolution compared to higher-order ambisonics. The selection of the encoding method must consider the application, available computational resources, and the desired level of spatial detail. Therefore, understanding the trade-offs associated with different encoding schemes is vital for successful spatial audio applications. Careful consideration must be given to aspects like the microphone array configuration and the order of the ambisonics representation which significantly influences the spatial accuracy of the encoding. Further research focusing on optimized encoding techniques for specific use cases is warranted to advance the field.

ELSA Architecture#

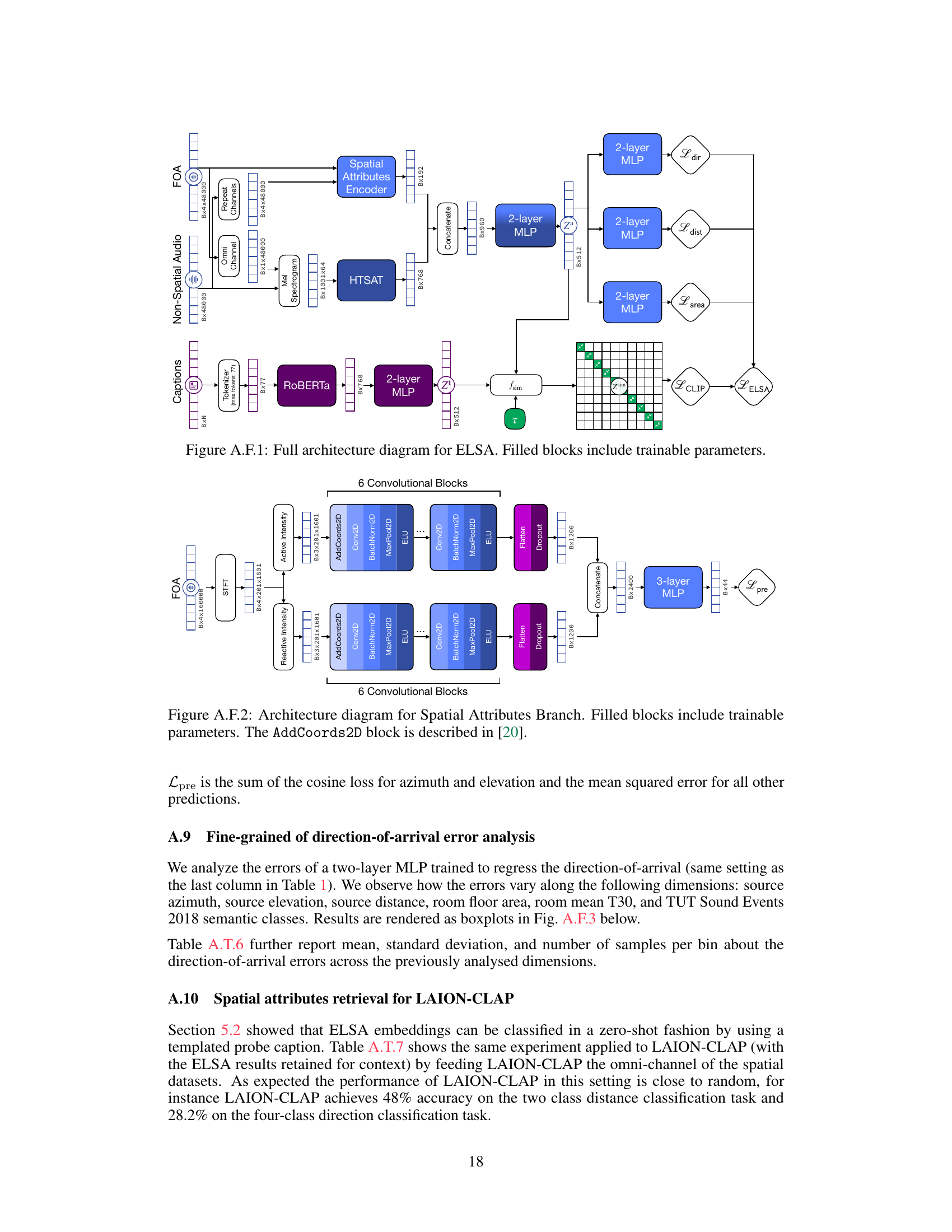

The ELSA architecture is a multimodal model designed for learning spatially-aware language and audio embeddings. It leverages a contrastive learning approach, training on a dataset of spatially augmented audio and corresponding captions. The core of ELSA consists of separate audio and text encoders. The audio encoder is particularly noteworthy, incorporating two distinct branches: one for semantic audio features and another for spatial attributes. This dual-branch design enables ELSA to effectively capture both the meaning of a sound and its location within a soundscape. The model’s innovation lies in its ability to seamlessly integrate spatial information into its audio representation, making it well-suited for tasks such as 3D sound localization and language-guided audio manipulation. The text encoder processes natural language captions that describe both the semantic and spatial characteristics of the sounds. Finally, a joint embedding space facilitates alignment between the representations of both modalities. ELSA’s design thus allows for effective multi-modal tasks, including sound event detection, 3D localization, and the novel ability to manipulate spatial attributes using natural language commands.

Multimodal Contrastive Learning#

Multimodal contrastive learning, a powerful technique in machine learning, excels at aligning representations from different modalities (like text and audio). It leverages contrastive learning, where similar samples from multiple modalities are pushed closer together in embedding space, while dissimilar samples are pushed further apart. This approach is particularly effective in scenarios with limited paired data; it creates strong alignment between modalities, even with noisy or imperfect pairings. The success of multimodal contrastive learning hinges on carefully designed encoders to capture the essential features from each modality, and a well-defined loss function to guide the alignment process. The resulting joint embedding space enables various downstream tasks like cross-modal retrieval, generation, and question answering, showcasing the power of understanding the relationships between different types of information. Applications in areas such as audio-visual understanding and language-guided audio editing demonstrate its potential to create more sophisticated and user-friendly AI systems. A key challenge, however, remains data scarcity: high-quality, multi-modal datasets are difficult to obtain, necessitating careful data augmentation and synthetic data generation techniques to enhance model performance.

Spatial Attribute Retrieval#

Spatial attribute retrieval, in the context of audio-language models, focuses on retrieving audio based on spatial descriptions. This task requires the model to understand not only the semantic content of the audio (e.g., ‘dog barking’) but also its location relative to a listener (’to the left’, ‘behind’). A successful model needs robust spatial audio encoding and a sophisticated way of linking the audio’s spatial attributes with textual descriptions. Challenges include generating a sufficiently large dataset of paired spatial audio and natural language descriptions and handling various levels of spatial precision in language (e.g., precise coordinates vs. vague terms). Evaluation typically involves tasks like retrieval (given a description, find the matching audio) or classification (classify audio according to pre-defined spatial categories). Advancements in this field have shown promising results and pave the way for more immersive and intuitive human-computer interactions in audio-based applications. However, there is a need for more research on tackling real-world complexities such as noisy environments, reverberations, and overlapping sound sources.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on spatially-aware language and audio embeddings are plentiful. Expanding ELSA to handle more complex acoustic scenes with overlapping sound sources and moving sound sources is crucial. This requires more sophisticated audio processing techniques and potentially new datasets capturing the richness of real-world soundscapes. Improving the robustness of caption augmentation through better handling of LLM hallucinations would enhance data quality. Exploring higher-order ambisonics would allow for higher spatial resolution, but also necessitates a deeper investigation into appropriate encoding techniques. Combining ELSA with other modalities such as video or other sensor data would unlock the potential for richer multimodal applications. Investigating the ethical considerations surrounding generated soundscapes is essential, to prevent misuse in creating realistic deepfakes. Finally, developing more efficient training methods and reducing the reliance on extensive synthetic datasets are paramount to making the model more accessible and scalable for wider application.

More visual insights#

More on figures

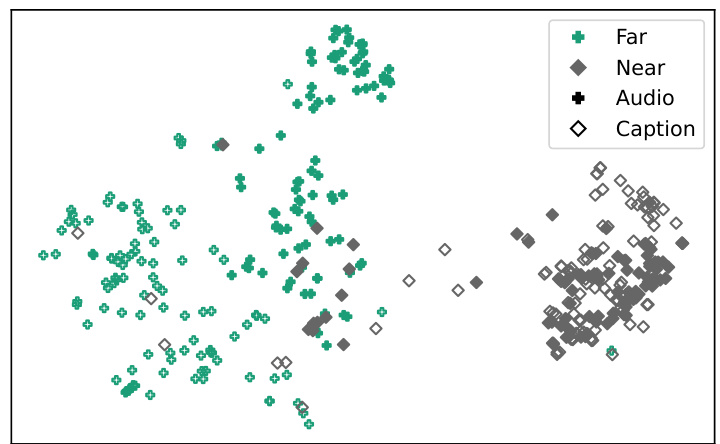

This figure shows a UMAP projection of the ELSA embeddings from the test sets of Spatial-AudioCaps and Spatial-Clotho datasets. The plot visually represents the embeddings in a 2D space, where each point corresponds to an embedding. Filled markers indicate embeddings derived from spatial audio data, while hollow markers represent embeddings derived from spatial captions. The UMAP projection itself is guided by the training set embeddings. The visualization highlights how the embeddings cluster according to the direction of the sound source (left, right, front, back). This demonstrates that the model effectively encodes spatial information in both audio and textual representations.

This figure illustrates the process of creating a dataset for training a spatially aware audio-language model. It shows three stages: (a) Spatial audio pipeline that simulates various room properties and microphone placements, creating spatial audio; (b) Augmentation of original captions with simulated room information, then prompting a large language model (LLM) to rewrite captions to reflect the spatial information; (c) Encoding of the augmented captions and audio using encoders, aligning representations using contrastive learning (CLIP objective). This pipeline helps create training data that links spatial audio attributes with natural language descriptions, enabling the model to learn spatial awareness.

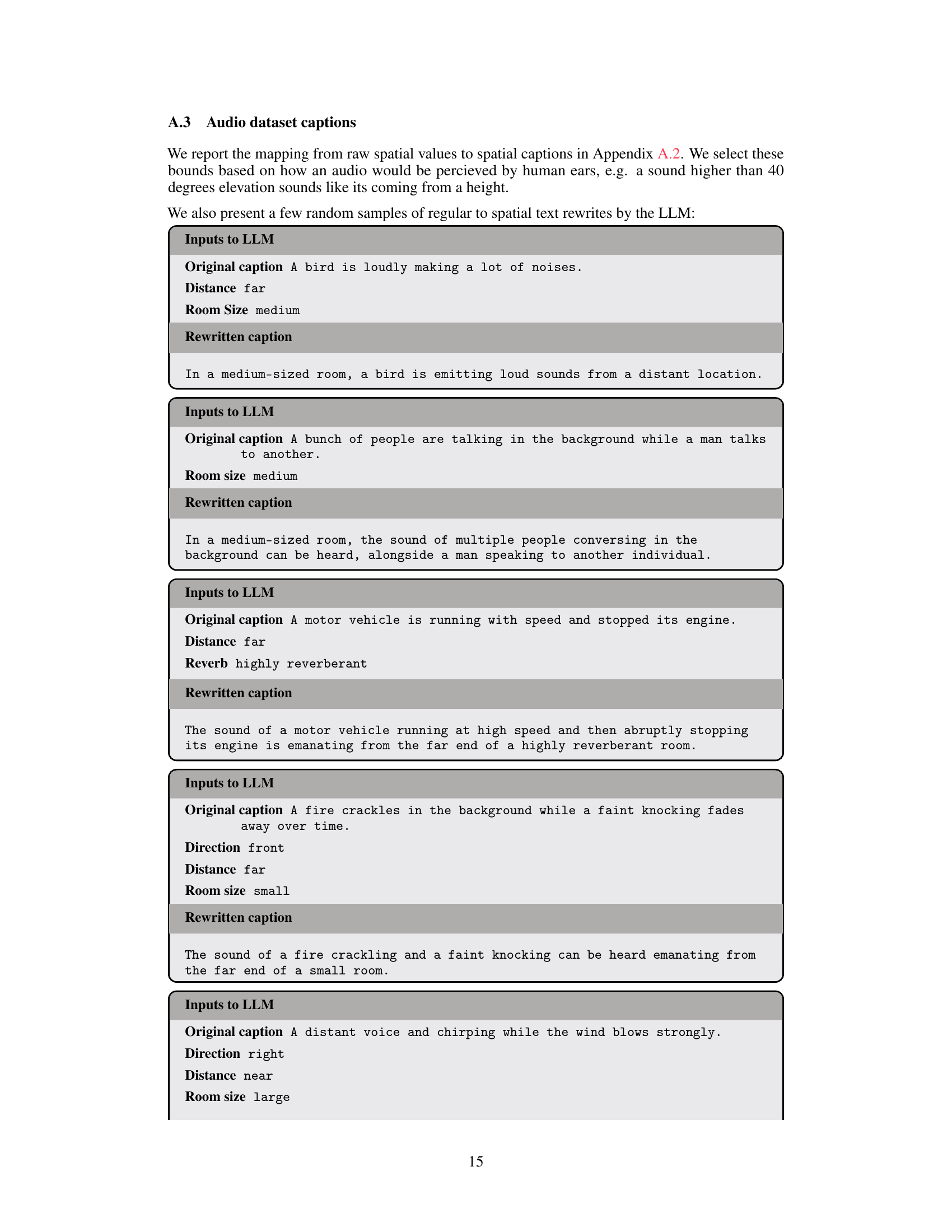

This figure details the architecture of the spatial attributes branch of the audio encoder. It consists of two parallel branches processing active and reactive intensity vectors, each containing six convolutional blocks followed by a flatten layer, a dropout layer, and an ELU activation. The outputs of these two branches are then concatenated and fed into a three-layer multilayer perceptron (MLP) that projects them into a 44-dimensional embedding. This design allows the model to capture both the semantic and spatial attributes of the audio input.

The figure illustrates the pipeline used to create a dataset for training ELSA, a model that learns to map between spatial audio and natural language descriptions. It begins with generating simulated spatial audio using room parameters and microphone/source placement. This simulated audio is then paired with existing audio captions, which are then rephrased by a large language model (LLM) to incorporate the spatial characteristics of the simulated room. These augmented captions and audio are finally encoded and aligned using a contrastive learning method.

The figure illustrates the pipeline used for creating a dataset and training the ELSA model. It begins by simulating spatial audio in various environments with specific parameters (room dimensions, materials, reverberation, source locations). These parameters are then incorporated into captions describing the audio. The captions are then fed to a large language model (LLM) to rephrase them into more natural-sounding sentences that incorporate the spatial attributes. Finally, the spatially augmented captions and audio are encoded and aligned using a contrastive learning objective, resulting in a model that jointly learns semantic and spatial audio representations.

This figure illustrates the pipeline used to generate a dataset for training the ELSA model. It begins with using simulated rooms with varying parameters (dimensions, materials, reverberation) and placing sound sources at different locations within those rooms. The original captions for the audio are then augmented using the room properties, and a large language model (LLM) rewrites these captions to incorporate the spatial characteristics of the generated audio. Finally, these spatially augmented captions and audio are encoded and aligned using a contrastive learning approach.

This figure shows a UMAP projection of the ELSA embeddings from the test sets of Spatial-AudioCaps and Spatial-Clotho datasets. The filled markers represent embeddings from spatial audio data, while the hollow markers represent embeddings from spatial captions. The UMAP projection was created using supervised dimension reduction, which emphasizes the differences in directionality between the embeddings rather than their semantic content. The plot visually demonstrates how ELSA’s representation space clusters embeddings based on spatial direction.

This figure shows the architecture of the spatial audio caption generation system. First, the first-order ambisonics (FOA) audio is fed into the ELSA audio branch, which outputs a 512-dimensional embedding. This embedding is then passed through a 2-layer multi-layer perceptron (MLP), resulting in a 768-dimensional embedding. This embedding is then concatenated with the text embedding, which is obtained by the GPT-2 model. Finally, the combined embedding is used for autoregressive decoding to generate the caption.

More on tables

This table compares ELSA with other state-of-the-art models in terms of semantic and spatial capabilities. It shows each model’s ability to perform semantic caption retrieval (measured by mean Average Precision at 10, or mAP@10) on the AudioCaps dataset and its ability to perform 3D sound localization (measured by mean absolute error in degrees) on the REAL component of the TUT Sound Events 2018 dataset. ELSA is highlighted as uniquely achieving both open vocabulary semantic understanding and spatial localization.

This table presents the zero-shot classification accuracy of ELSA on spatial attributes. It uses cosine similarity between audio embeddings and templated captions (e.g., ‘A sound coming from near’). Accuracy is measured by comparing the spatial attribute of the closest test sample to the attribute in the template. Since this is a novel task, no comparisons to baselines are provided.

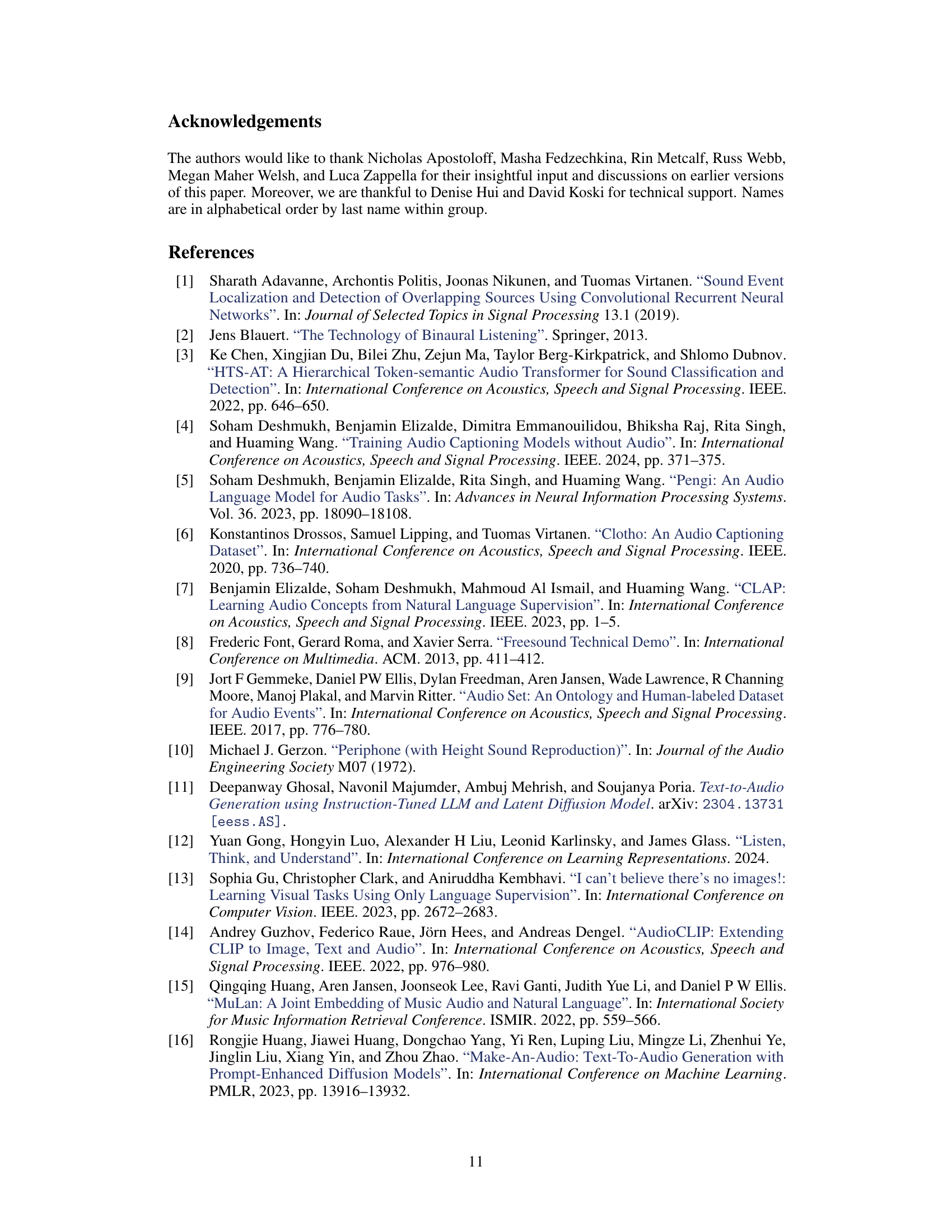

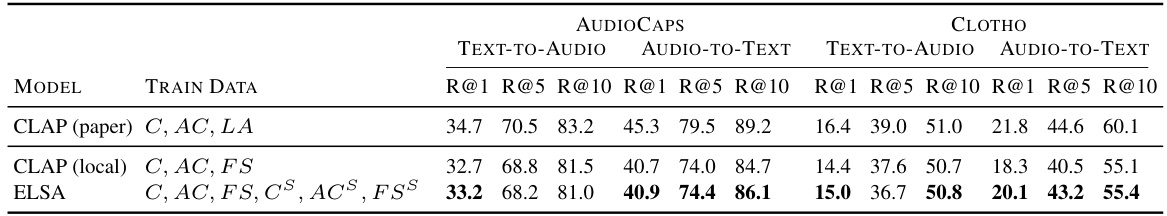

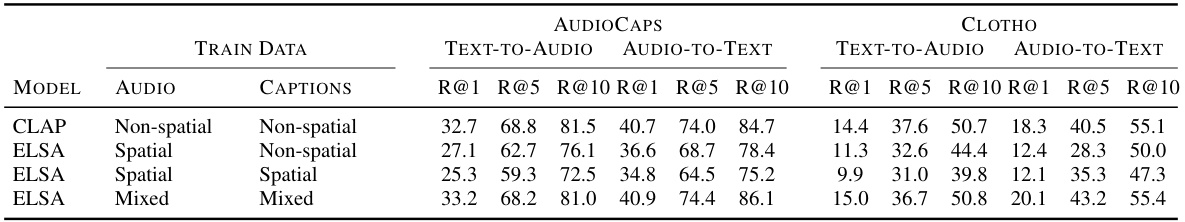

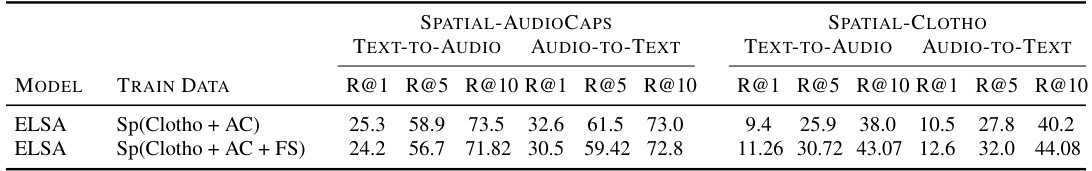

This table compares the performance of ELSA and LAION-CLAP on semantic retrieval tasks using the original (non-spatial) versions of the Clotho and AudioCaps datasets. It shows the recall at ranks 1, 5, and 10 (R@1, R@5, R@10) for both text-to-audio and audio-to-text retrieval. The table highlights that while ELSA is trained on both spatial and non-spatial data, its performance on non-spatial data is comparable to LAION-CLAP, which was trained only on non-spatial data. Different training data combinations are explored for both models (Clotho, AudioCaps, Freesound, and their spatially augmented counterparts).

This table presents the results of evaluating the spatial audio caption generation model. The evaluation used the Audio Captioning task from the DCASE Challenges. It compared generated captions from spatial audio with ground truth captions. The evaluation is done on the test splits of Spatial-AudioCaps (S-AC) and Spatial-Clotho datasets.

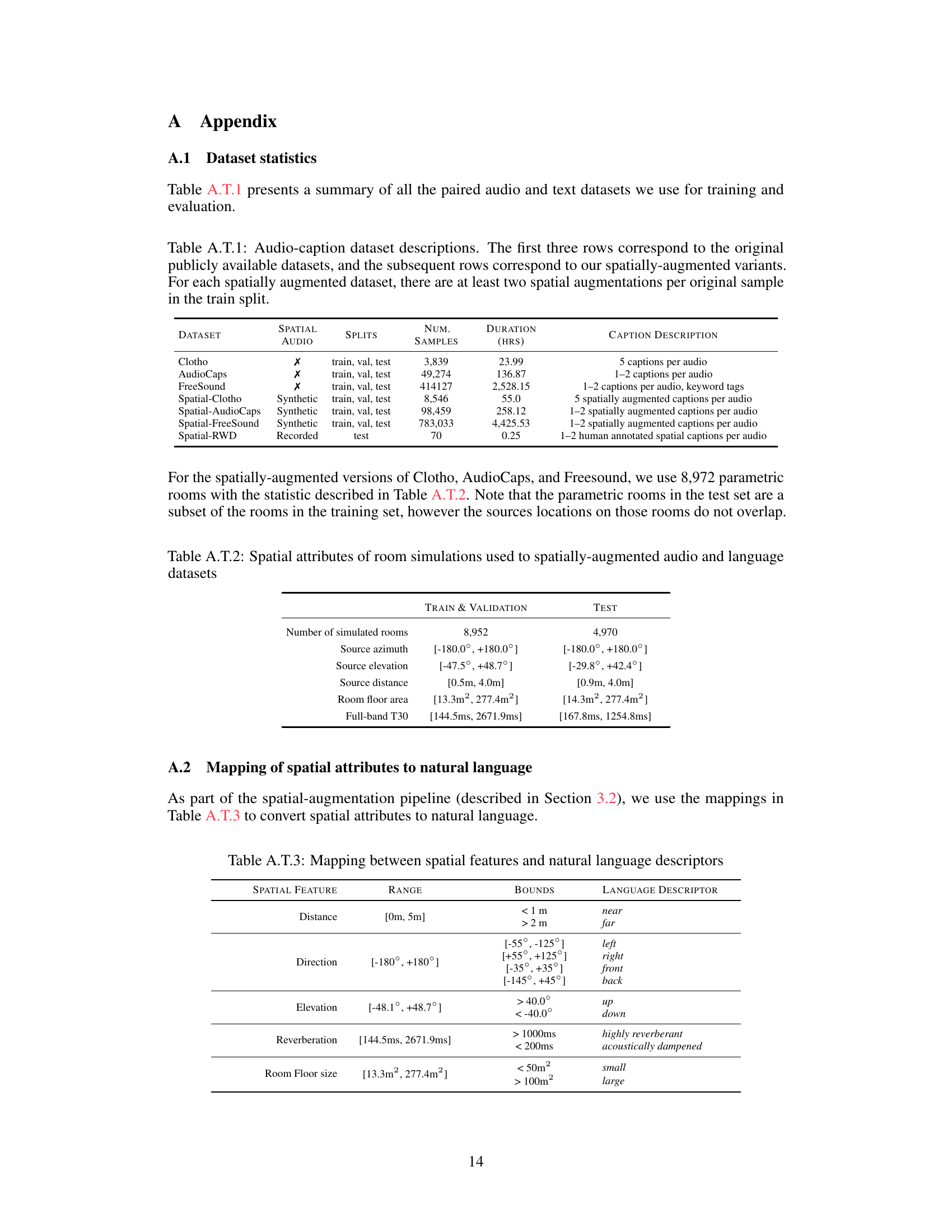

This table presents a summary of the datasets used in the paper. It lists the dataset name, whether it contains spatial audio, the splits (training, validation, testing), the number of samples, the duration in hours, and a description of the captions.

This table compares the capabilities and performance of different models on two tasks: semantic caption retrieval using the AudioCaps dataset and 3D sound localization using the REAL component of the TUT Sound Events 2018 dataset. It highlights that ELSA is unique in handling both open vocabulary language understanding and spatial localization, and it shows that ELSA achieves performance comparable to state-of-the-art models for both tasks. The table includes the models, their semantic and spatial capabilities, and their performance metrics.

This table compares ELSA against other models on two tasks: semantic caption retrieval using the AudioCaps dataset and 3D sound localization using the REAL component of the TUT Sound Events 2018 dataset. The table highlights ELSA’s unique ability to handle both open vocabulary language understanding and spatial localization, unlike other models that excel at only one of these tasks. ELSA’s performance is shown to be competitive with state-of-the-art models in both areas.

This table compares ELSA’s performance against other state-of-the-art models on two tasks: semantic caption retrieval (using the AudioCaps dataset) and 3D sound localization (using the REAL component of the TUT Sound Events 2018 dataset). It highlights that ELSA uniquely combines open vocabulary language understanding with spatial localization capabilities, achieving competitive results on both tasks.

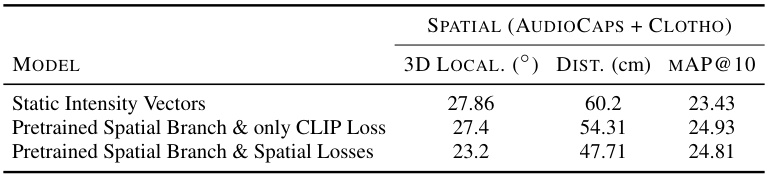

This table presents ablation studies on the ELSA model, comparing its performance with different configurations. Specifically, it shows the impact of using static intensity vectors versus a learned encoder for spatial information, and the effect of including spatial regression losses in addition to the contrastive loss. The results are evaluated using 3D localization error, distance error, and the mean average precision at 10 (mAP@10), a metric reflecting the model’s semantic retrieval ability.

This table compares the performance of ELSA and CLAP on semantic retrieval tasks using the original (non-spatial) versions of the Clotho and AudioCaps datasets. It highlights that although ELSA is trained on both spatial and non-spatial data, its performance on non-spatial data is comparable to LAION-CLAP, which was trained only on non-spatial data. The table also shows the training data used for each model and provides retrieval scores (R@1, R@5, R@10) for both text-to-audio and audio-to-text tasks.

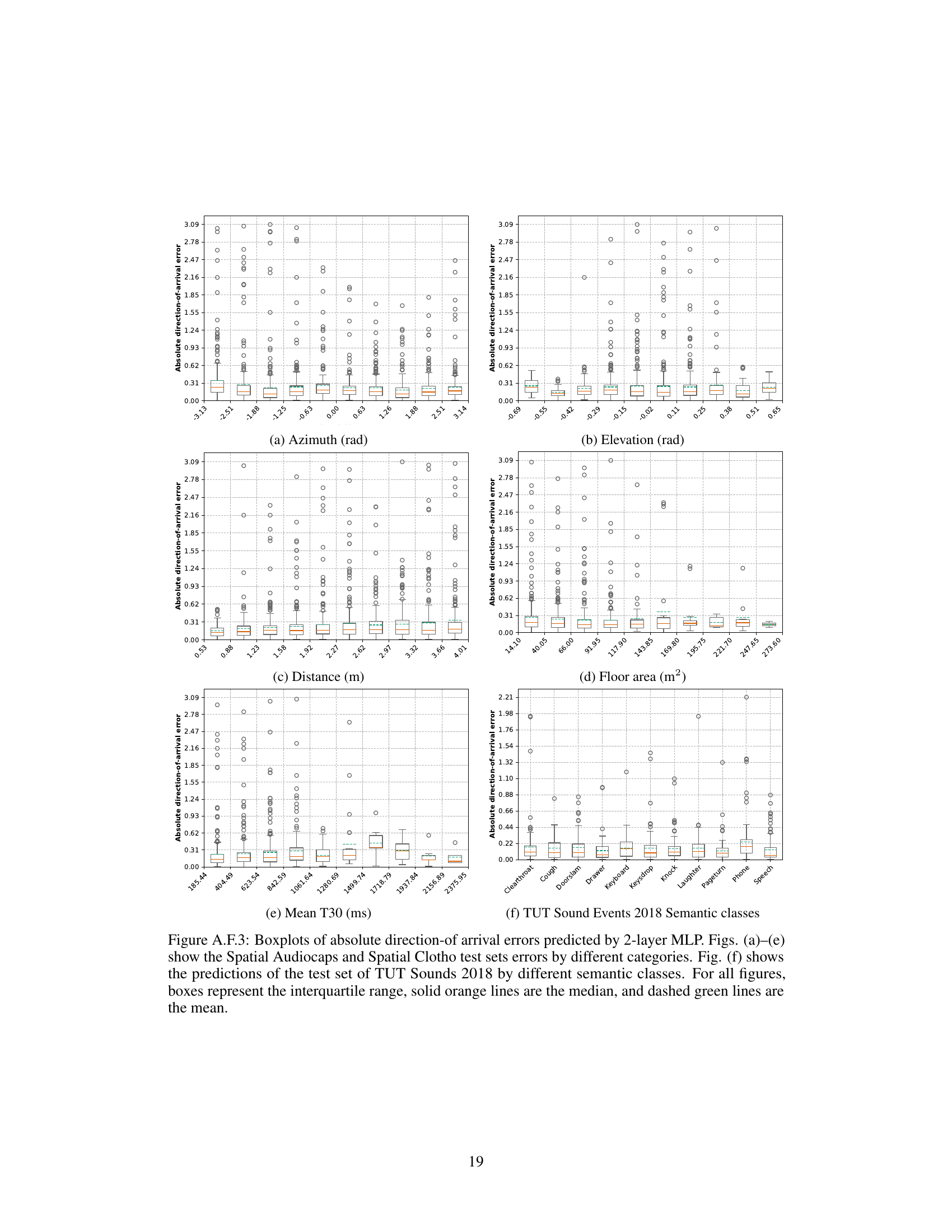

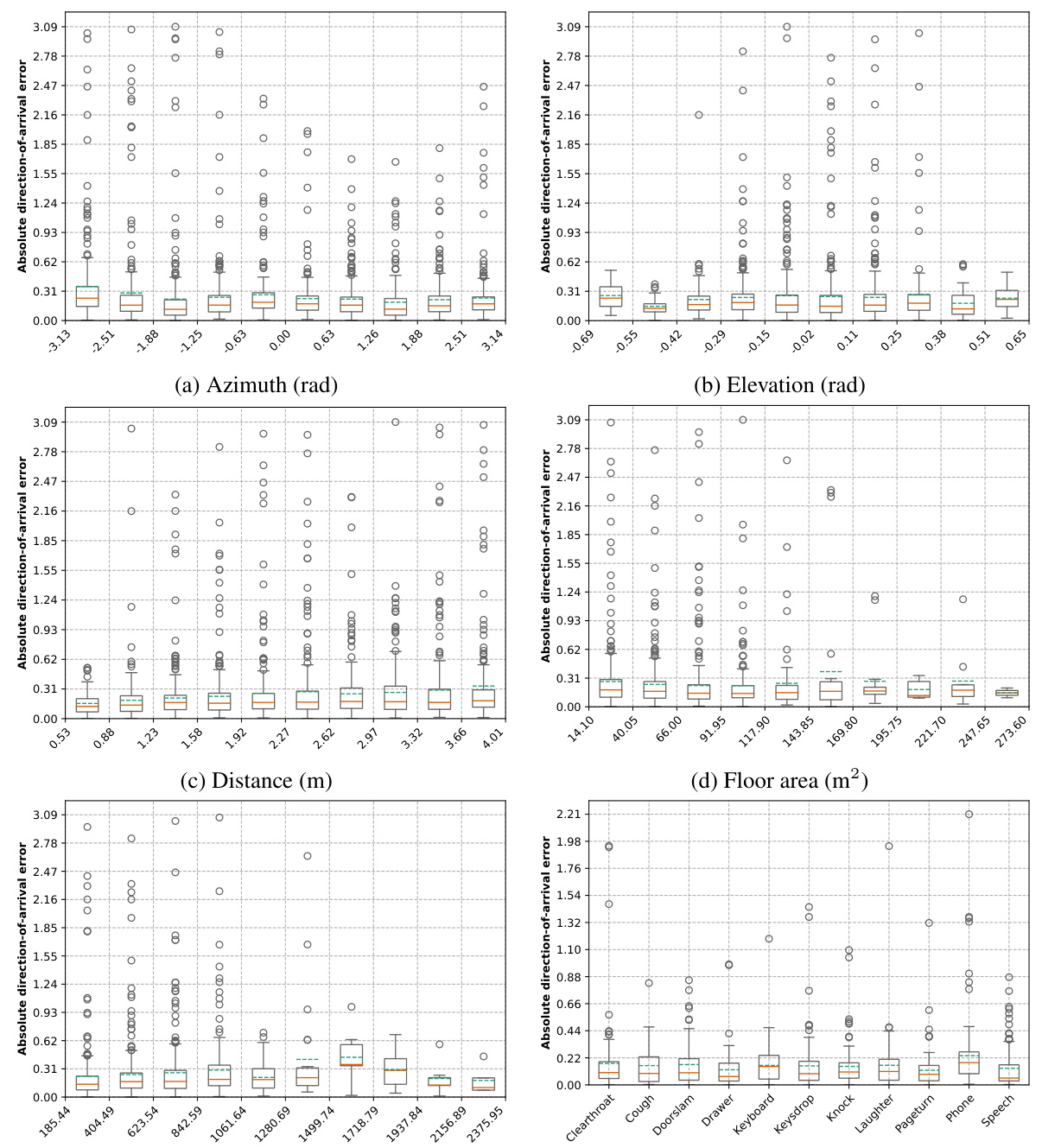

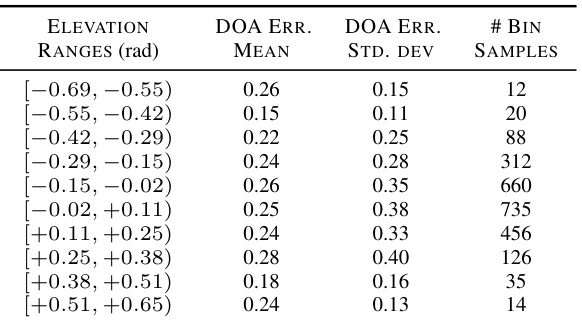

This table presents a detailed breakdown of the errors in direction-of-arrival predictions made by a two-layer Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) model. The analysis is categorized by several factors to understand the sources of error. These factors include azimuth, elevation, distance, room floor area, reverberation time (T30), and semantic class from the TUT Sound Events 2018 dataset. For each category, the table provides the mean and standard deviation of the prediction errors, along with the number of samples used in the calculation. This level of detail helps assess the model’s performance across different conditions and identify areas for potential improvement.

This table presents a detailed breakdown of the errors in predicting the direction of arrival of sounds. It shows how these errors vary depending on different factors such as azimuth, elevation, distance, room size, reverberation time, and semantic class of the sound. The table is divided into six parts, each showing the mean and standard deviation of the errors for specific ranges of values for each of the factors.

This table presents a detailed breakdown of the errors in predicting the direction of arrival of sounds, as determined by a two-layer Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) model. The errors are analyzed across various factors: azimuth, elevation, distance, floor area of the room, reverberation time (T30), and semantic classes from the TUT Sound Events 2018 dataset. For each factor, the table shows the mean and standard deviation of the errors, along with the number of samples used in the analysis. This level of detail helps to understand the performance of the model under different conditions and identify potential areas for improvement.

This table shows a detailed breakdown of the errors in direction-of-arrival prediction made by a two-layer Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) model. It analyzes the errors across various factors: azimuth, elevation, distance, room floor area, reverberation time (T30), and semantic classes from the TUT Sound Events 2018 dataset. For each factor, it provides the mean and standard deviation of the errors, along with the number of samples in each bin.

This table presents a detailed breakdown of the errors in direction-of-arrival predictions made by a two-layer multi-layer perceptron (MLP) model. It categorizes these errors based on several factors: azimuth, elevation, distance, room floor area, reverberation time (T30), and semantic classes from the TUT Sound Events 2018 dataset. For each category, the table provides the mean and standard deviation of the errors, along with the number of samples used in the calculation.

This table compares ELSA against other state-of-the-art models in terms of semantic retrieval (using AudioCaps) and 3D sound localization (using TUT Sound Events 2018). It highlights ELSA’s unique ability to handle both open vocabulary language understanding and spatial localization, demonstrating competitive performance on both tasks. The table clearly shows ELSA’s advantages over models which only address semantic understanding or spatial awareness.

This table presents the zero-shot classification accuracy of ELSA on spatial attributes. It uses cosine similarity between audio embeddings and captions templated with spatial attributes (e.g., ’near’, ‘far’, ’left’, ‘right’). Accuracy is determined by comparing the closest test sample’s attribute to the template attribute. No baseline comparisons are provided as this is a novel task.

This table compares the performance of ELSA and CLAP models on semantic retrieval tasks using the original (non-spatial) versions of Clotho and AudioCaps datasets. It highlights that while ELSA was trained on both spatial and non-spatial data, it maintains competitive performance with CLAP, which was trained only on non-spatial data. The table specifies the training datasets used for both models (Clotho, AudioCaps, Freesound, and their spatially augmented counterparts) and provides Recall@1, Recall@5, and Recall@10 scores for both text-to-audio and audio-to-text retrieval tasks. A locally trained version of CLAP is also included for comparison.

This table compares the performance of ELSA and CLAP on semantic retrieval tasks using the original (non-spatial) versions of Clotho and AudioCaps datasets. It shows Recall@1, Recall@5, and Recall@10 for both audio-to-text and text-to-audio retrieval. The key finding is that ELSA, despite being trained on a mixture of spatial and non-spatial audio, maintains comparable performance to LAION-CLAP on non-spatial audio retrieval tasks. The table also details the training data used for both models, highlighting the different datasets and their spatial augmentation.

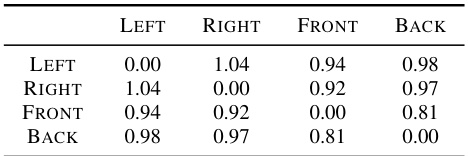

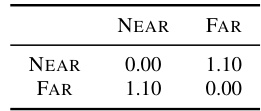

This table presents the Wasserstein distances between different clusters of ELSA embeddings in a 512-dimensional space. The clusters are formed based on spatial attributes: direction (left, right, front, back) in part (a) and distance (near, far) in part (b). Lower Wasserstein distances indicate higher similarity between the clusters. This helps to demonstrate how well the ELSA embeddings capture and separate spatial information.

This table presents the Wasserstein distances calculated between clusters of ELSA embeddings in a 512-dimensional space. The clusters are formed based on either direction (left, right, front, back) or distance (near, far) attributes. Lower Wasserstein distances indicate higher similarity between the clusters. The table provides quantitative support for the qualitative observation from Figure 2 that ELSA embeddings capture spatial attributes effectively.

This table presents the results of an experiment where the spatial direction encoded in ELSA audio embeddings was swapped using text prototypes. The original direction was removed, and a new direction was added. The table shows the number of samples, recall@10 (a measure of semantic retrieval), the accuracy of the direction classification after the swap, and the change in recall@10 after the swap for each original and new direction combination. This experiment demonstrates the ability to manipulate the spatial attributes of audio in the ELSA embedding space using text.

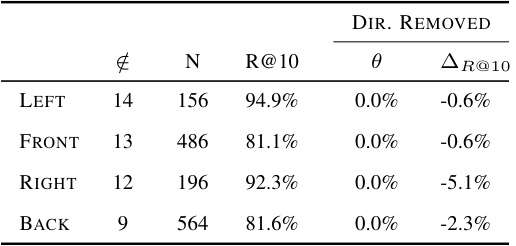

This table presents ablation study results on swapping spatial direction of ELSA embeddings. It shows the number of samples misclassified by the direction classifier (ξ), the number of samples used for transposition (N), the recall@10 score (R@10) before and after transposition, the classification accuracy (θ) after transposition, and the change in recall@10 (ΔR@10) after transposition, for each of the four original directions (left, front, right, and back). The study removes the original direction but does not add a new direction.

This table compares the performance of several models on two tasks: semantic caption retrieval using the AudioCaps dataset and 3D sound localization using the REAL component of the TUT Sound Events 2018 dataset. It highlights ELSA’s unique ability to handle both open vocabulary language and spatial information, showing competitive results compared to models specialized in either semantic or spatial tasks.

This table compares the performance of different models on two tasks: semantic caption retrieval and 3D sound localization. It shows that ELSA, the model introduced in the paper, performs comparably to state-of-the-art models on both tasks, despite being the only model to handle both open vocabulary language and spatial audio. The table highlights ELSA’s unique ability to combine semantic and spatial understanding.

This table compares the capabilities of different models in semantic caption retrieval and 3D sound localization. It highlights that ELSA, unlike other models, handles both open vocabulary language understanding and spatial localization, achieving comparable performance to state-of-the-art models in both tasks.

Full paper#