↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Global vehicle localization using city-scale maps is a challenging problem due to the inherent ambiguity in urban environments. Existing methods often localize each time point independently, neglecting temporal relationships between observations. This can lead to inaccurate and unreliable estimations, especially in complex scenes with many similar-looking landmarks. Learnable particle filters have shown promise for global localization but have been primarily limited to simulations or simplified real-world scenarios. Additionally, most methods only use past observations.

This paper introduces MDPS, a new differentiable particle smoother that overcomes these limitations. MDPS integrates forward and backward particle streams, leveraging both past and future observations for more accurate state estimation. The method uses stratified resampling to provide low-variance gradient estimates, enabling effective end-to-end training of neural network dynamics and observation models. Experimental results on both synthetic and real-world datasets demonstrate the superior accuracy and efficiency of MDPS compared to state-of-the-art methods and search-based baselines, showcasing its potential for applications in various fields.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in robotics and computer vision because it introduces a novel differentiable particle smoother (MDPS) that significantly improves the accuracy of state estimation in challenging scenarios like city-scale global localization. It addresses limitations of existing particle filters and smoothers by incorporating both past and future data for more robust and accurate results, opening avenues for improved navigation and mapping systems.

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the MDPS (Mixture Density Particle Smoother) method. The left panel shows the forward and backward particle filters, which are combined using neural networks to produce a smoothed posterior. The right panel details the feature extraction and measurement model for global localization, using first-person camera views, BEV feature maps, and map features to calculate particle weights.

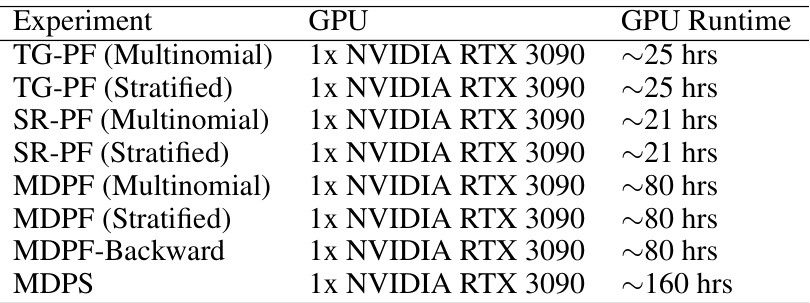

This table shows the computational resources required for training different particle filter and smoother models on a bearings-only tracking task. It details the GPU used (NVIDIA RTX 3090) and the approximate training time for each model, highlighting that training MDPS takes significantly longer than training other models. The note indicates that multiple models were trained concurrently to improve efficiency, and that the reported runtimes are based on sequential training runs.

In-depth insights#

Diff. Particle Smoother#

A differentiable particle smoother offers a significant advance in state estimation, particularly for complex, real-world scenarios. By leveraging the strengths of particle filters (handling multi-modality) and smoothers (incorporating past and future information), a differentiable model allows for end-to-end learning of dynamics and observation models. This eliminates the need for hand-engineered components, which are often error-prone and limit accuracy. The use of techniques like stratified resampling further improves gradient estimation, leading to more stable and efficient training. The resulting smoother surpasses existing particle filters and search-based methods, demonstrating superior accuracy in city-scale global localization tasks, where ambiguous environments pose considerable challenges. While the computational cost might increase compared to simpler filters, the significant improvement in accuracy and robustness makes differentiable particle smoothing a valuable contribution. Future work could focus on addressing the curse of dimensionality, improving scalability, and exploring further applications of this powerful approach to state estimation problems.

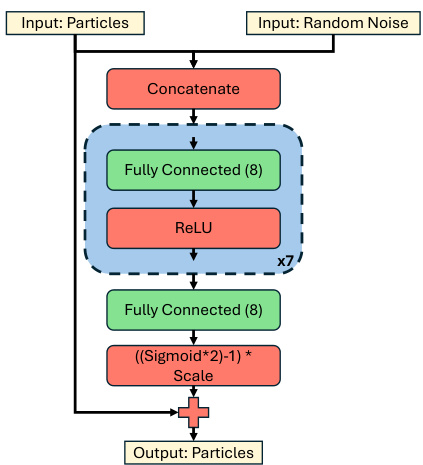

MDPS Architecture#

The MDPS architecture is a novel approach to particle smoothing that leverages two differentiable particle filters, one operating forwards and the other backwards in time. This two-filter design allows the model to integrate information from both past and future observations, leading to more accurate state estimations compared to standard particle filters that only use past information. The key innovation is the differentiable resampling strategy, which ensures gradients can be effectively propagated backward through time during training, unlike traditional discrete resampling techniques. Mixture density networks are used to represent the continuous distributions of the forward and backward filters, facilitating the integration of information from the two streams. The architecture also includes learned neural network components for modelling the dynamics and observation models, enabling end-to-end learning directly from data, without requiring the careful engineering of these components often found in classical approaches. The result is a smoother that is significantly more accurate, scalable, and robust, particularly for complex, multi-modal posterior distributions often found in real-world applications. The integration of the forward and backward filters via an importance weighted sampling method further enhances the accuracy and efficiency of the system.

City-Scale Results#

In the city-scale global localization experiments, the MDPS model demonstrated superior performance compared to other state-of-the-art methods. Its ability to integrate both past and future information, particularly through the novel two-filter smoothing approach, proved crucial for resolving ambiguities in complex urban environments. The incorporation of stratified resampling further enhanced the robustness and accuracy of MDPS, significantly outperforming baselines such as retrieval and dense search methods. The results highlight the model’s ability to successfully handle the challenges of city-scale localization, including multi-modal posterior densities and noisy real-world data. Learned dynamics and measurement models within MDPS were key to this success, enabling accurate and robust state estimation, where the use of a continuous mixture density representation of the state provided a significant advantage in representing complex uncertainty.

Resampling Methods#

Resampling in particle filters addresses the degeneracy problem, where particle weights become unevenly distributed over time, leading to poor state estimates. Several resampling techniques exist, each with trade-offs in terms of variance and computational cost. Multinomial resampling is simple but high-variance. Stratified resampling reduces variance by ensuring more uniform sampling across the weight distribution. The choice of resampling method significantly impacts the filter’s performance, particularly in high-dimensional or complex state spaces. Differentiable resampling methods are crucial for end-to-end training of particle filters, enabling gradient-based optimization of the filter parameters. These approaches typically involve relaxing the discrete resampling step to allow for continuous gradient calculations, often introducing approximations that may impact accuracy. Finding the right balance between computational efficiency and accuracy remains a key challenge in developing effective differentiable resampling techniques. Future research should focus on developing new resampling methods that achieve low variance with minimal computational overhead, especially for applications requiring real-time or online operation.

Future Work#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending MDPS to handle more complex observation models (e.g., incorporating multiple sensors or dealing with noisy or incomplete data) is crucial. Investigating the impact of different resampling strategies and kernel functions on performance would be valuable. A thorough analysis of the computational complexity and scalability of MDPS is also needed, particularly for large-scale applications. It’s worth investigating alternative differentiable resampling techniques, aiming to reduce variance and computational cost while maintaining accuracy. Finally, applying MDPS to a wider variety of state estimation problems, such as robotics, autonomous driving, and human motion tracking, would demonstrate its broader utility and reveal new challenges and opportunities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

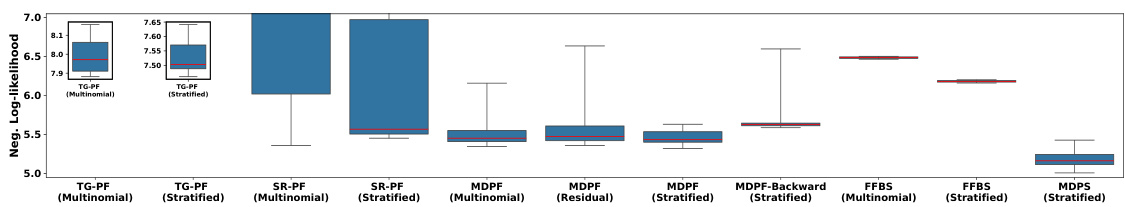

The figure compares the performance of different particle filters and smoothers on a bearings-only tracking task. It shows that stratified resampling improves the performance of several particle filters and that the proposed MDPS significantly outperforms the other methods by incorporating both past and future observations.

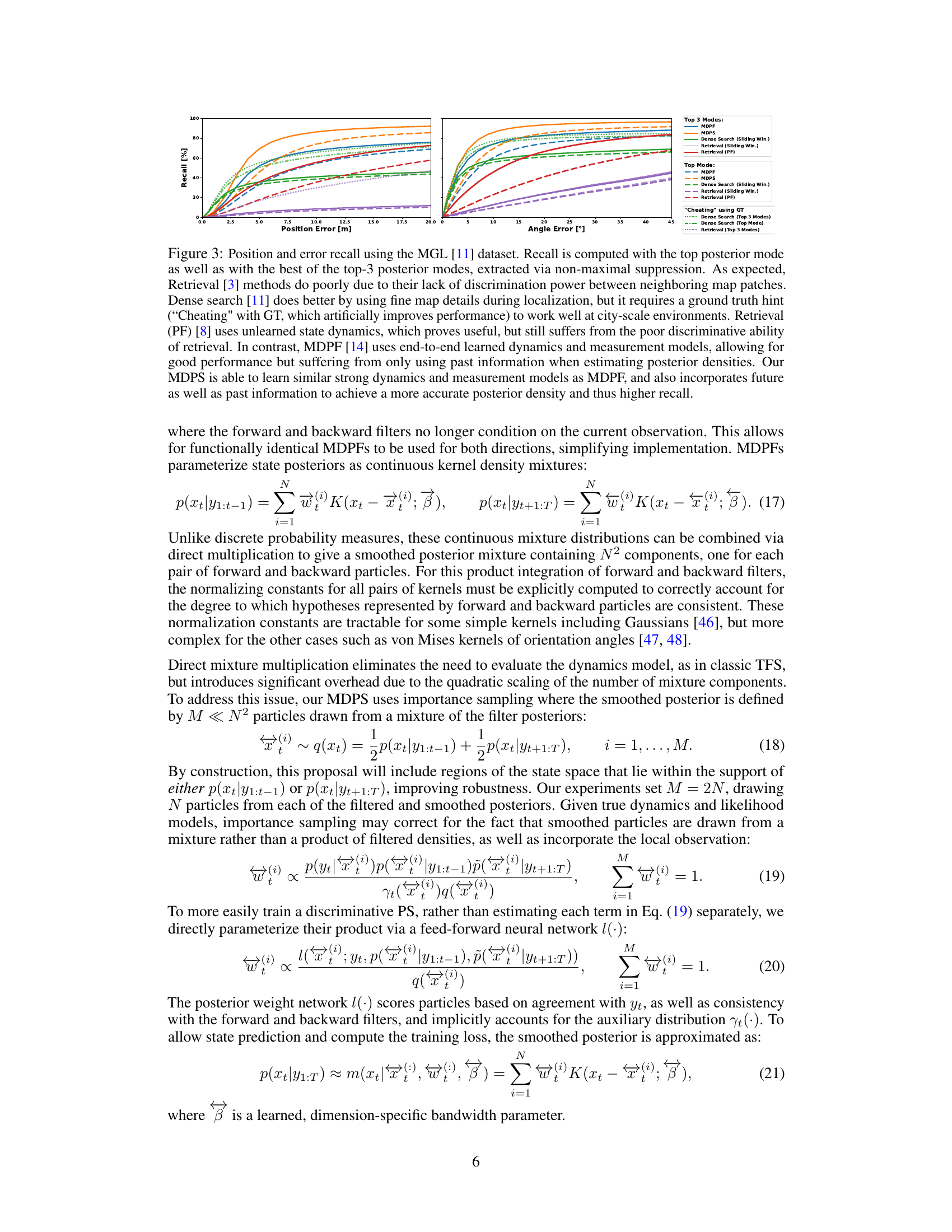

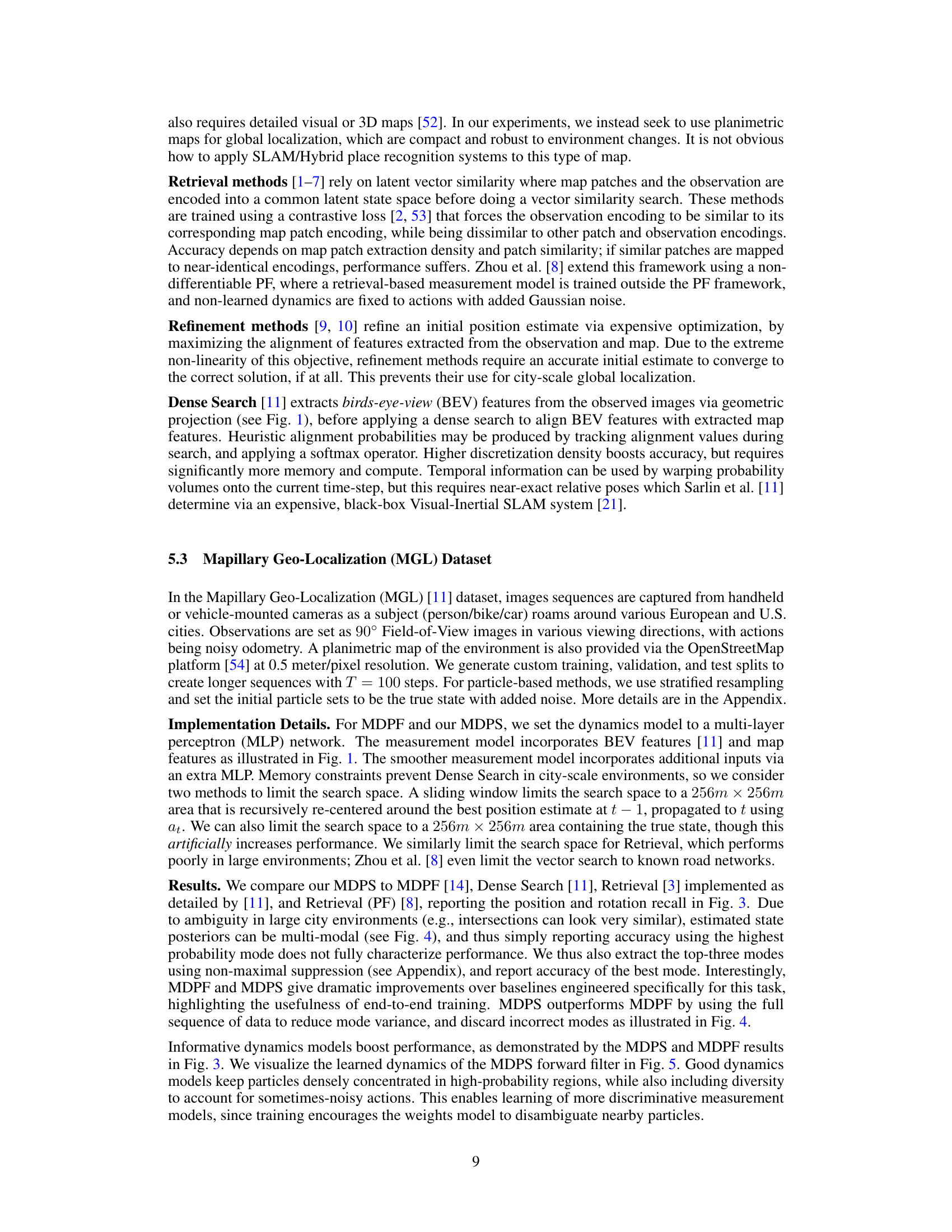

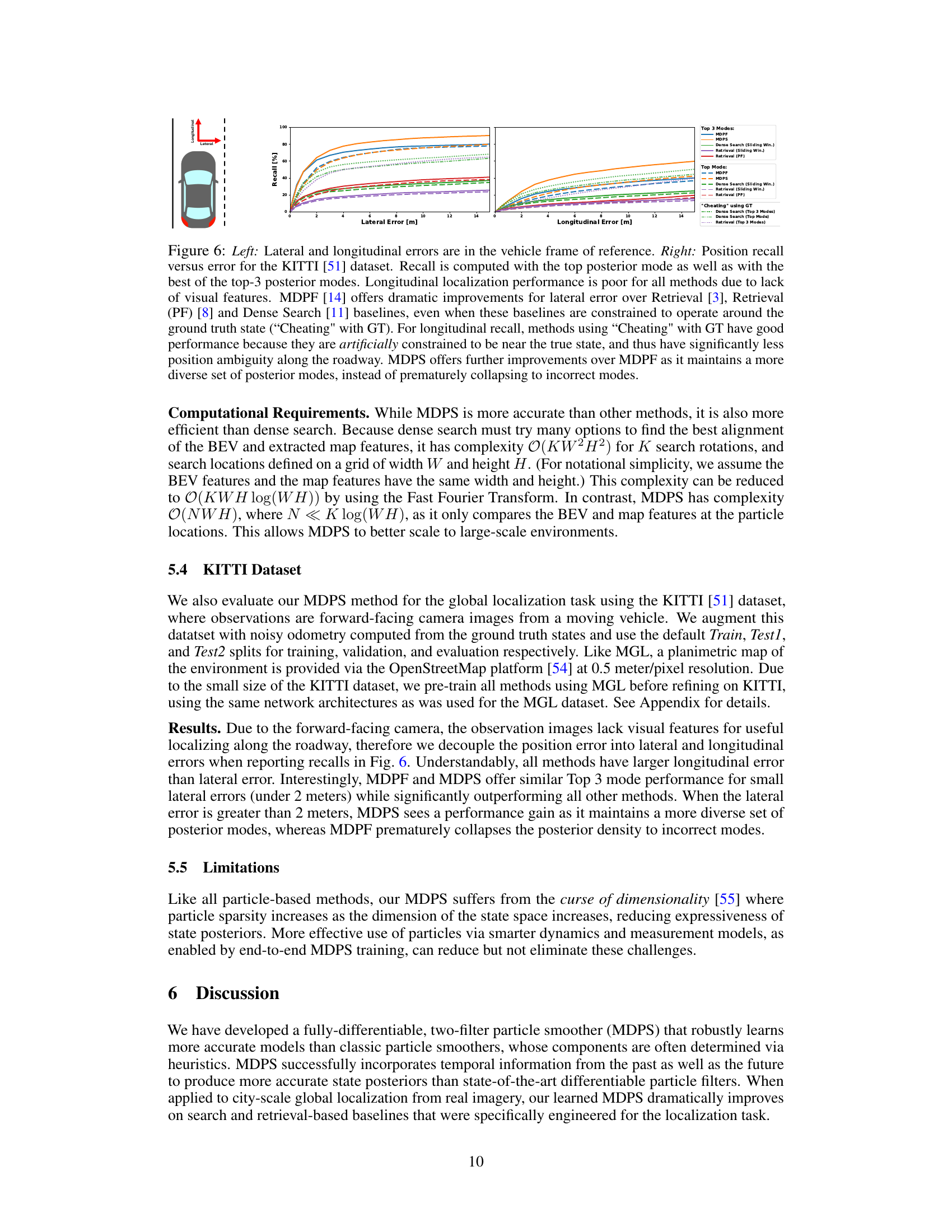

This figure compares the performance of different global localization methods on the Mapillary Geo-Localization (MGL) dataset. The methods are evaluated based on position error and recall, considering both the top predicted mode and the best of the top three modes. The results show that MDPS outperforms other methods, especially at higher accuracy levels, demonstrating the benefit of using both past and future information for more accurate localization.

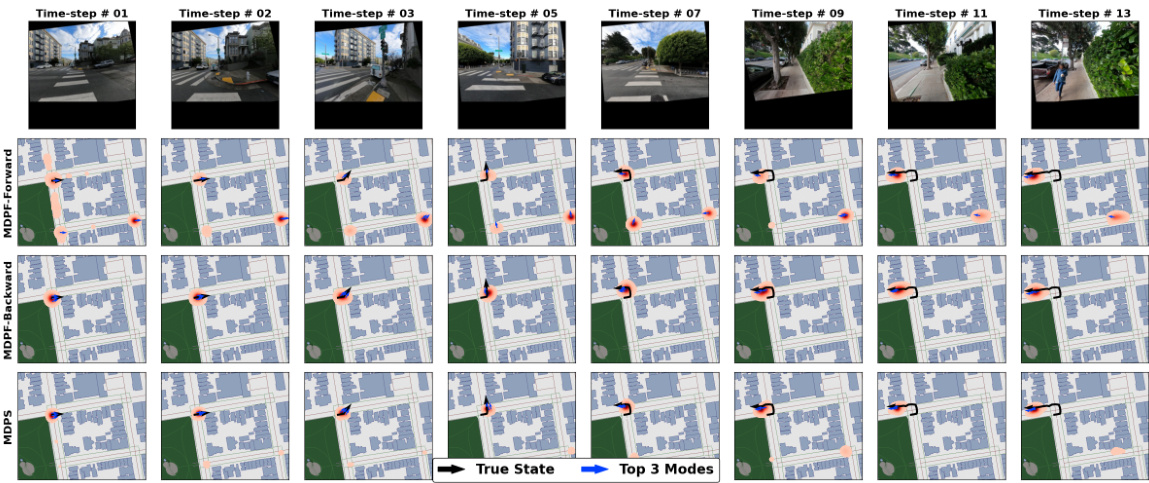

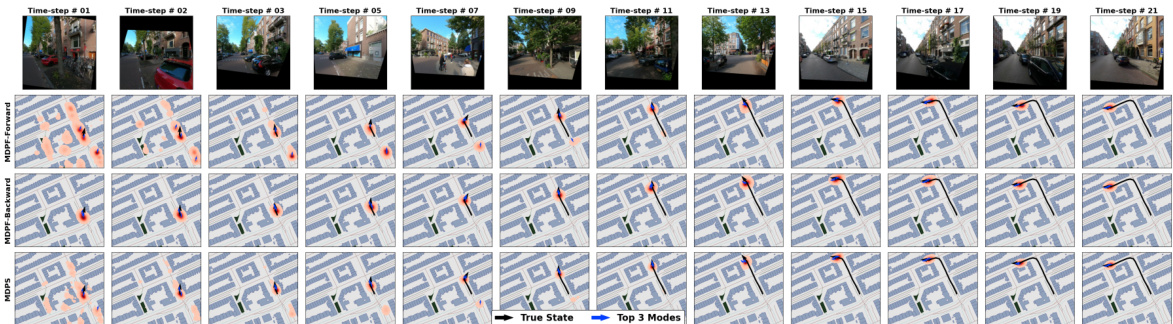

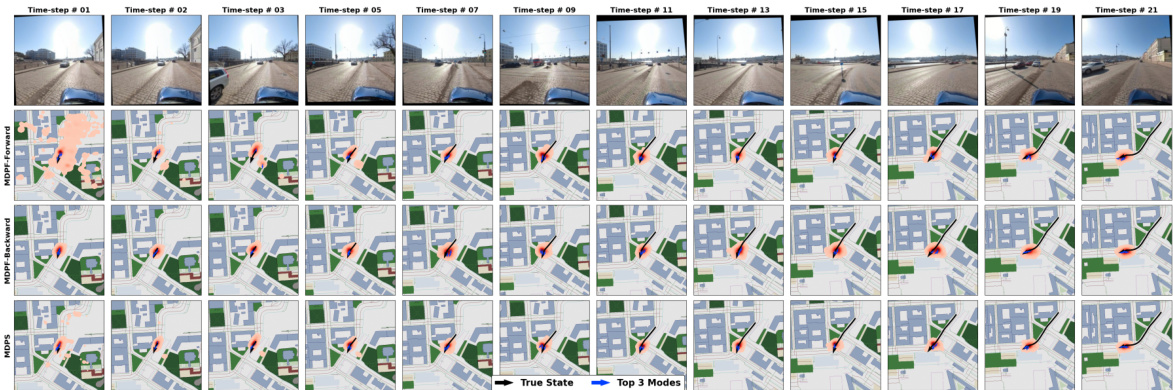

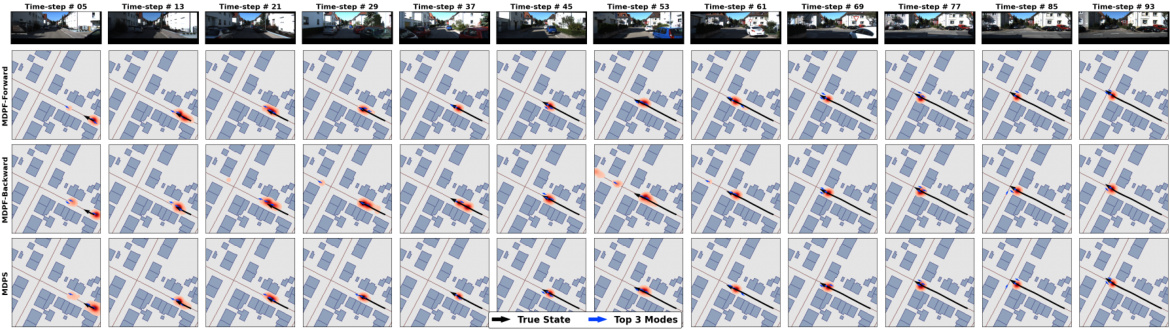

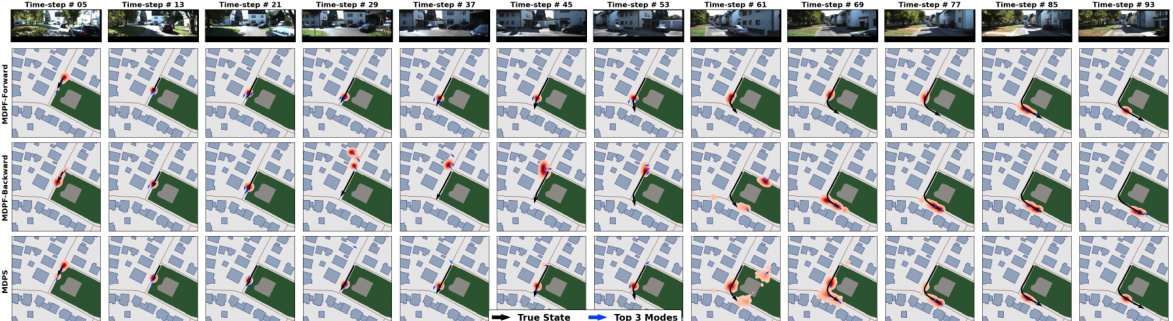

This figure shows example trajectories from the Mapillary Geo-Localization (MGL) dataset. It compares the performance of MDPS, MDPF-Forward, and MDPF-Backward in estimating the vehicle’s location over time. The top row displays the observations. The subsequent rows show the true state (black arrow and line), the estimated posterior density (red cloud), and the top three most likely states (blue arrows) for each method. The figure highlights how MDPS, by integrating forward and backward information, resolves ambiguities and provides a more accurate and precise posterior than the other two methods.

The figure shows the position error and recall for different global localization methods on the Mapillary Geo-Localization (MGL) dataset. MDPS significantly outperforms other methods, including retrieval-based methods, search-based methods, and even a particle filter using past information only (MDPF). The improved performance of MDPS is attributed to its use of both past and future information for state estimation.

This figure displays example trajectories from the Mapillary Geo-Localization (MGL) dataset. It compares the performance of the proposed MDPS method to the forward and backward MDPFs. The top row shows the observations (images from a camera). Subsequent rows show the true vehicle trajectory (black arrow and line), the estimated posterior density (red cloud), and the three most likely positions (blue arrows) for each method. The example highlights that MDPS, by incorporating both forward and backward information, can resolve ambiguities that are challenging for individual filters and achieve a tighter, more accurate posterior density.

This figure shows example trajectories from the Mapillary Geo-Localization (MGL) dataset. It compares the performance of MDPS, MDPF-Forward, and MDPF-Backward in estimating the vehicle’s location over time. The top row displays the observations (camera images). The rows below show the true state trajectory (black line and arrow), the estimated posterior density (red cloud), and the top 3 most likely poses (blue arrows) for each method. The figure demonstrates how MDPS leverages information from both forward and backward passes to improve localization accuracy and reduce uncertainty, especially in ambiguous situations.

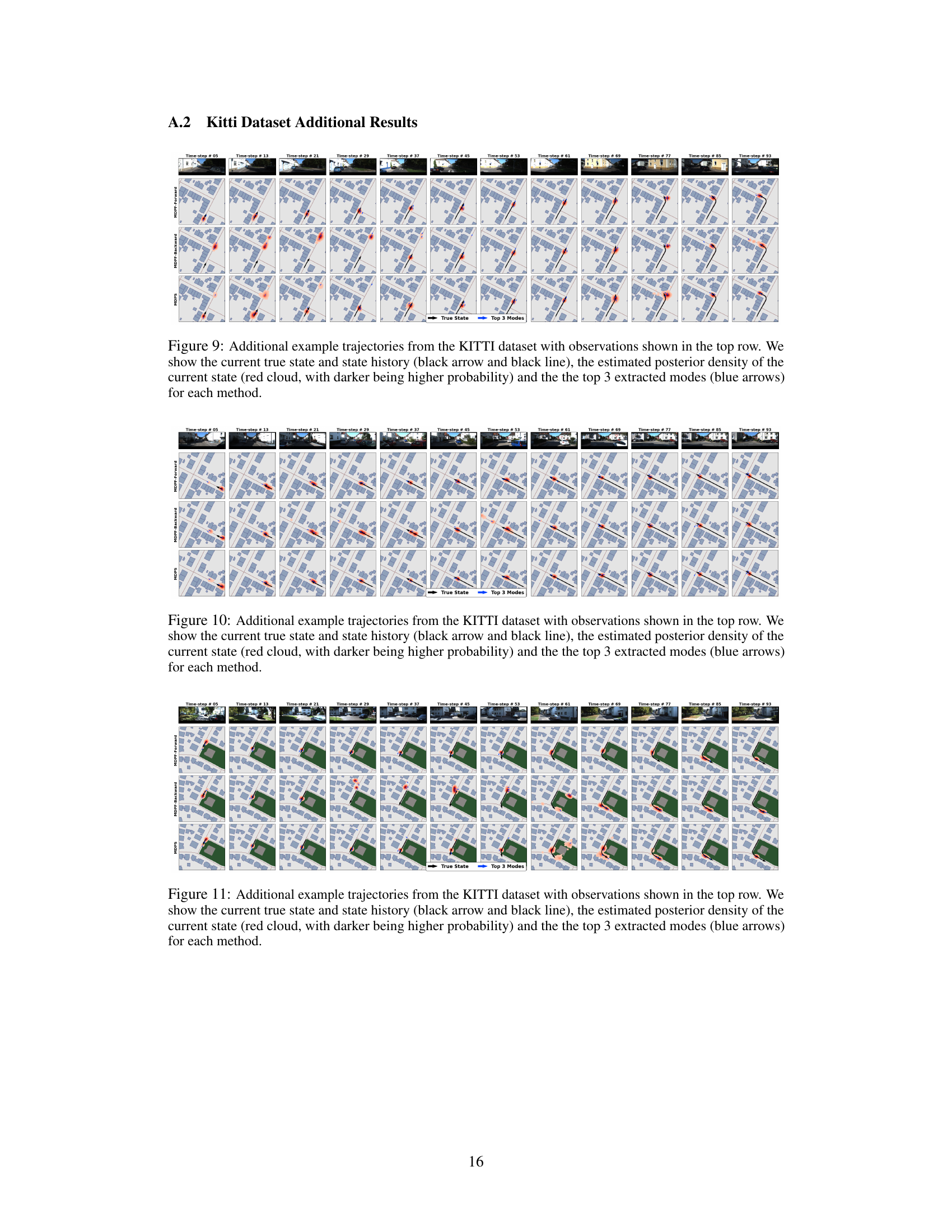

This figure shows example trajectories from the Mapillary Geo-Localization (MGL) dataset. For each time step, it visualizes the ground truth location (black arrow and line), the estimated posterior density of the current state (red cloud with darker areas indicating higher probability), and the top three most likely modes (blue arrows) predicted by MDPS, MDPF-Forward, and MDPF-Backward. The figure highlights how MDPS, by integrating both forward and backward particle filters, is better able to resolve ambiguities (like similar-looking intersections) and provides a more focused and accurate estimate of the vehicle’s location than the forward and backward filters alone.

This figure shows example trajectories from the Mapillary Geo-Localization (MGL) dataset. For each time step, it displays the true vehicle trajectory, the estimated posterior density by MDPS, MDPF-Forward, and MDPF-Backward, and the top three most probable states. It highlights MDPS’s ability to resolve ambiguities in the data by incorporating information from both forward and backward particle filters, resulting in a more accurate and focused posterior density than MDPF alone.

This figure shows example trajectories from the Mapillary Geo-Localization (MGL) dataset. It compares the performance of the proposed Mixture Density Particle Smoother (MDPS) with its forward and backward components (MDPF-Forward and MDPF-Backward) in resolving location ambiguity in a city-scale environment. The top row displays the camera observations, while the subsequent rows illustrate the true trajectory, the posterior density of states (red clouds), and the top 3 most probable modes (blue arrows) for each method. The visualization highlights MDPS’s superior ability to resolve ambiguity and provide a more accurate and concentrated posterior density compared to the individual filter components.

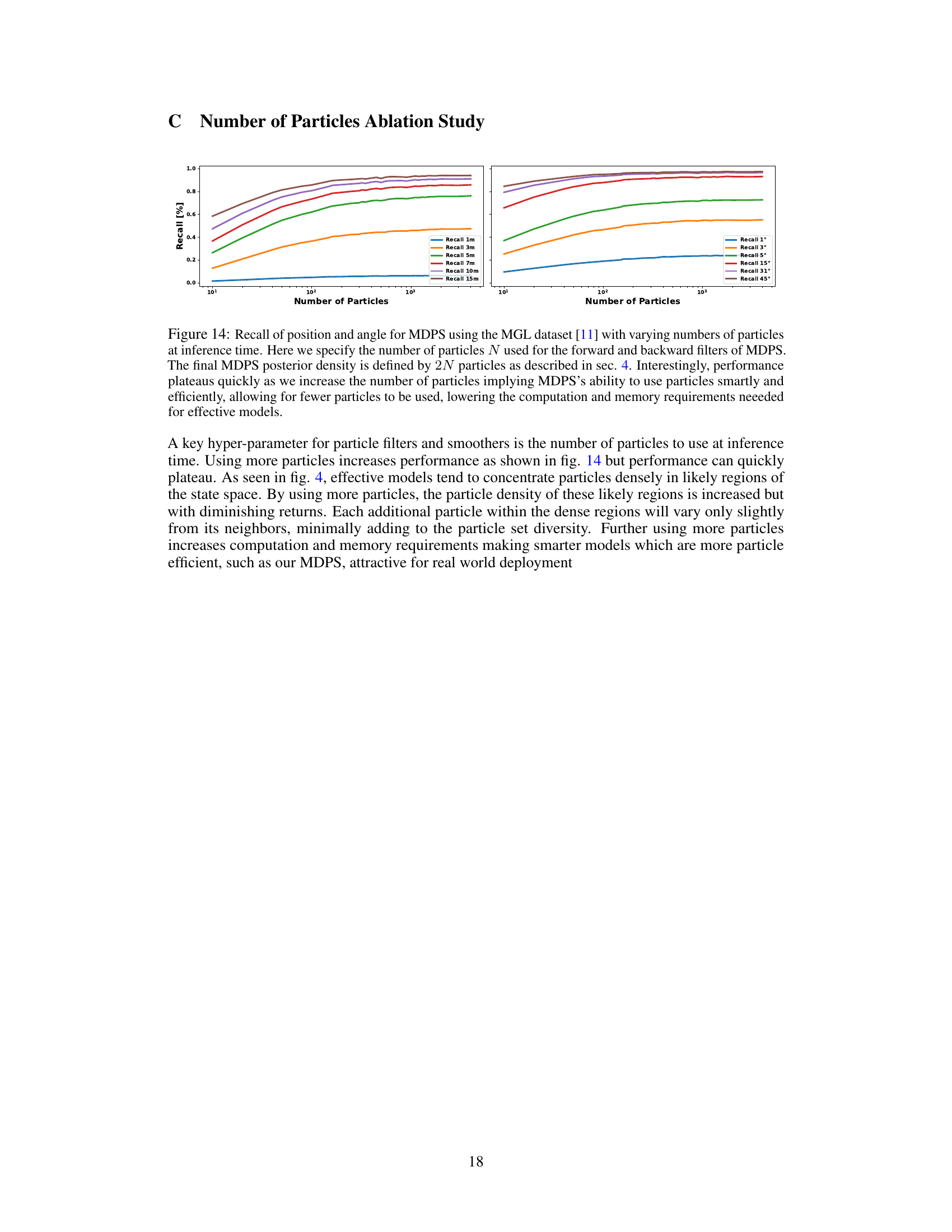

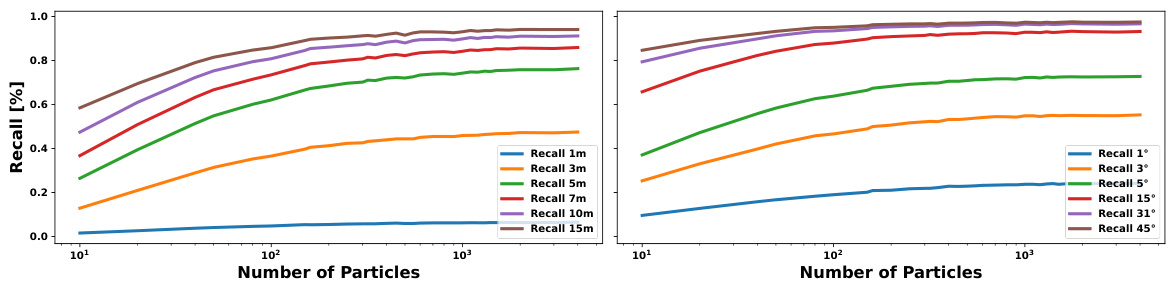

This figure shows the result of an ablation study on the number of particles used in the MDPS model for the MGL dataset. The left panel shows recall for different position errors (1m, 3m, 5m, 7m, 10m, 15m), while the right panel shows recall for different angular errors (1°, 3°, 5°, 15°, 31°, 45°). The x-axis represents the number of particles used in each filter (forward and backward), with the final MDPS using twice that number. The plots demonstrate that performance plateaus relatively quickly as the number of particles increases, suggesting that MDPS efficiently uses particles, leading to computational and memory savings.

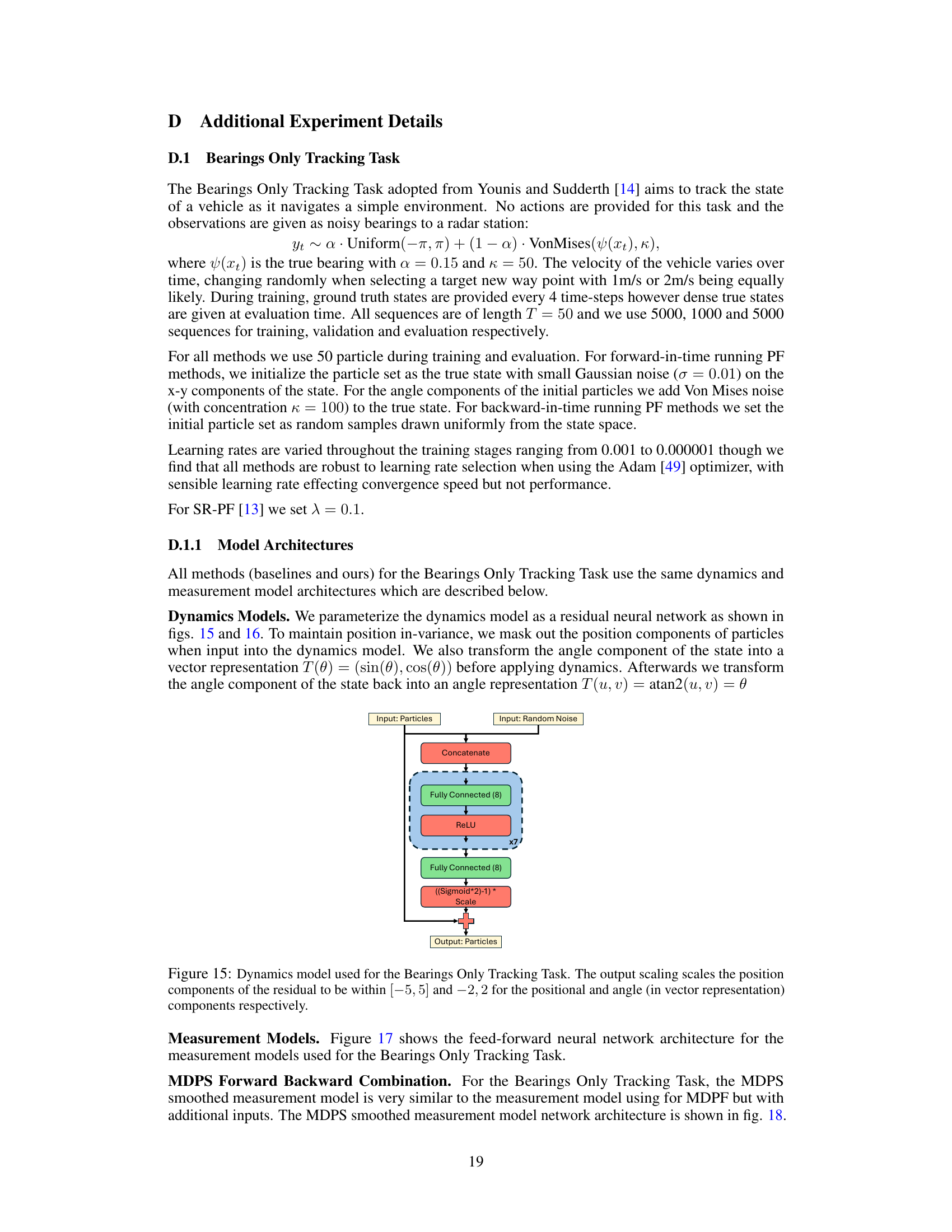

This figure shows the architecture of the Mixture Density Particle Smoother (MDPS). The left side illustrates the two-filter approach, with forward and backward particle filters integrated via neural networks to generate a smoothed posterior. The right side details the feature extraction and measurement model used in the global localization task. It shows how first-person camera views are processed into a BEV feature map and then compared to map features to obtain particle weights.

This figure illustrates the MDPS method, showing forward and backward particle filters integrated to produce a smoothed mixture posterior. The right side shows the feature encoders and measurement model for global localization, using first-person camera views encoded into a BEV feature map. Map features are extracted and particle weights computed via inner product.

This figure illustrates the Mixture Density Particle Smoother (MDPS) architecture. The left panel shows the forward and backward particle filters, which are combined to produce a smoothed posterior. The right panel details the feature encoders and measurement model used for global localization, showing how first-person camera views are processed into a BEV feature map and combined with map features to compute particle weights.

This figure shows the architecture of the Mixture Density Particle Smoother (MDPS). The left side illustrates the two-filter approach, where forward and backward particle filters are integrated using neural networks to generate a smoothed posterior distribution. The right side details the feature extraction and measurement model used for global localization, explaining how first-person camera views and map features are processed to estimate particle weights.

This figure illustrates the Mixture Density Particle Smoother (MDPS) architecture. The left panel shows the forward and backward particle filters, which are integrated using neural networks to produce a smoothed mixture posterior. The right panel details the feature extraction and measurement model used in the global localization task. First-person camera views are processed into a bird’s-eye-view (BEV) feature map, and map features are extracted using a feed-forward encoder. Finally, particle weights are calculated using the dot product of BEV and local map features.

This figure shows the architecture of the Mixture Density Particle Smoother (MDPS). The left panel illustrates the two-filter approach, where forward and backward particle filters are integrated using learned neural networks to produce a smoothed mixture posterior. The right panel details the feature encoders and measurement model used for global vehicle localization. It shows how first-person camera views are processed into a BEV feature map, map features are extracted, and particle weights are calculated using inner products between BEV features and local map features.

More on tables

This table presents the computational resources required for training different models for the global localization task using the Mapillary Geo-Localization (MGL) dataset. It shows the number of GPUs used, and the training time for each method. Note that Retrieval (PF) and MDPF do not require separate training because their models are reused or integrated within other models.

This table presents the computational resources required for the global localization experiments on the KITTI dataset. It details the number of GPUs used and the approximate training time for each method, noting that Retrieval (PF) did not require additional training as its models were taken from a pre-existing baseline. MDPF training times are also reported but note that this includes a refinement stage after initial pre-training with the MGL dataset.

Full paper#