↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are increasingly capable of complex reasoning and planning tasks. However, understanding how LLMs acquire these capabilities is still an open question. This paper focuses on the planning capabilities of LLMs by modeling the planning process as a path-finding task within a directed graph. Existing research on LLM planning offers mixed results, and a comprehensive theoretical understanding of how LLMs learn planning is lacking.

This research investigates the planning capabilities of Transformer-based LLMs by analyzing their internal mechanisms. The authors propose a new mathematical framework to demonstrate that Transformers can encode graph information into their weights. Their theoretical analysis shows that LLMs can learn both adjacency and limited reachability, but they cannot learn transitive reachability. The experiments validate the theoretical findings and show that Transformer architectures do learn adjacency and partial reachability. However, they fail to learn transitive relationships and therefore cannot successfully generate paths when concatenation is required.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it theoretically and empirically investigates the planning capabilities of large language models (LLMs), a critical area of current AI research. It offers new insights into how LLMs learn planning and their limitations, paving the way for developing more advanced planning and reasoning capabilities in future LLMs. The findings are important for researchers working on various LLM applications, including autonomous agents, problem-solving systems, and reasoning tasks. The use of path-finding task as a model for planning opens up new avenues for research.

Visual Insights#

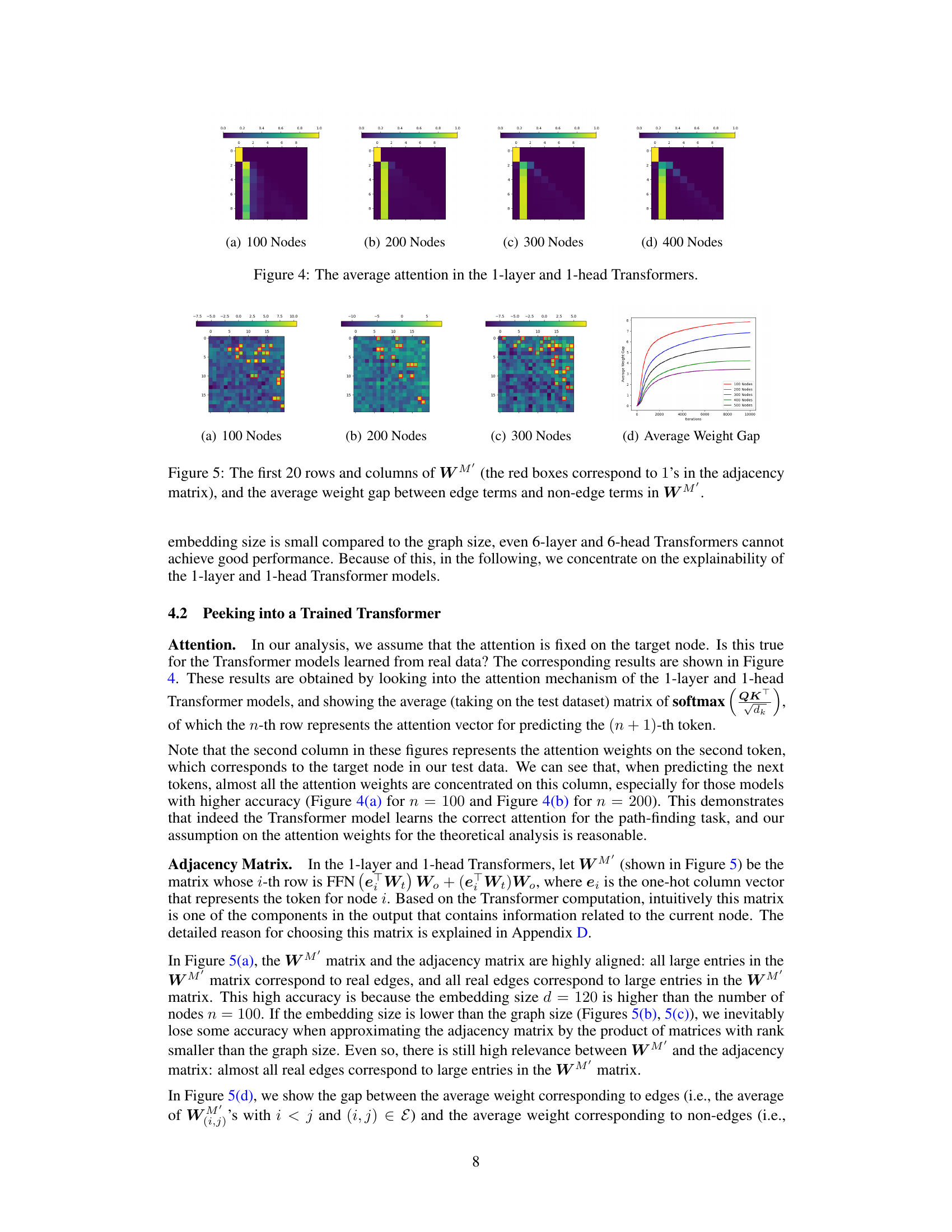

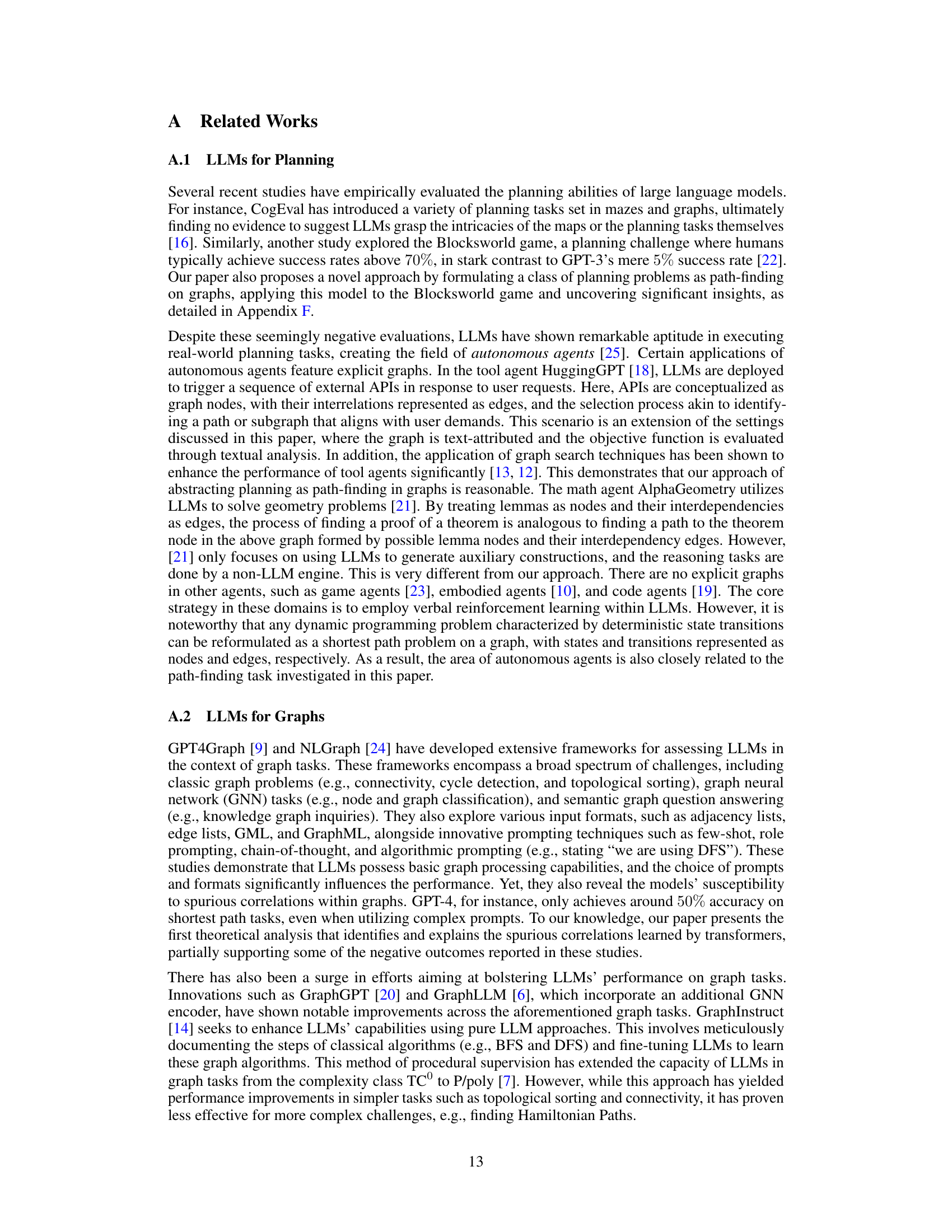

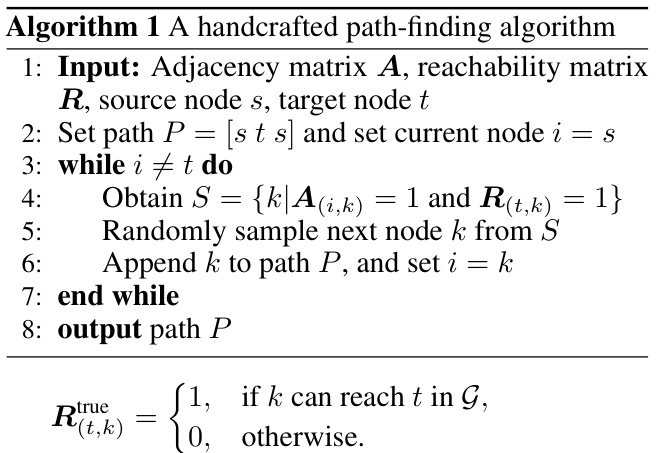

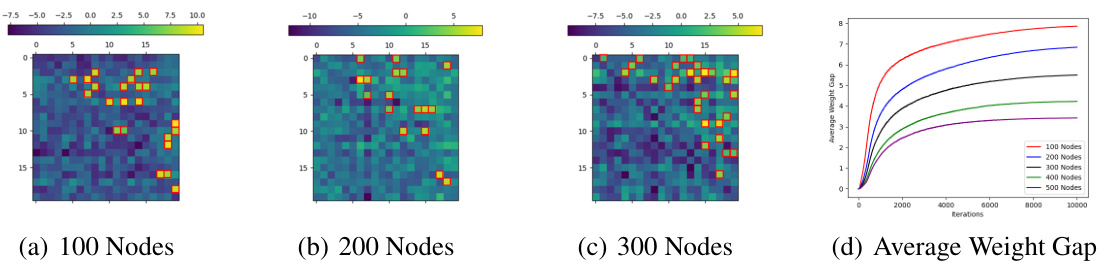

The figure shows the adjacency matrix learned by a simplified Transformer model trained on three different datasets (D1, D2, D3) compared to the true adjacency matrix. Dataset D1 contains paths of length 1; D2 contains paths of length 1 and 20% of paths longer than 1; and D3 contains all possible paths. The results show that the learned adjacency matrices successfully capture the structural information from the true adjacency matrix, demonstrating that the Transformer model can learn the adjacency matrix from training data.

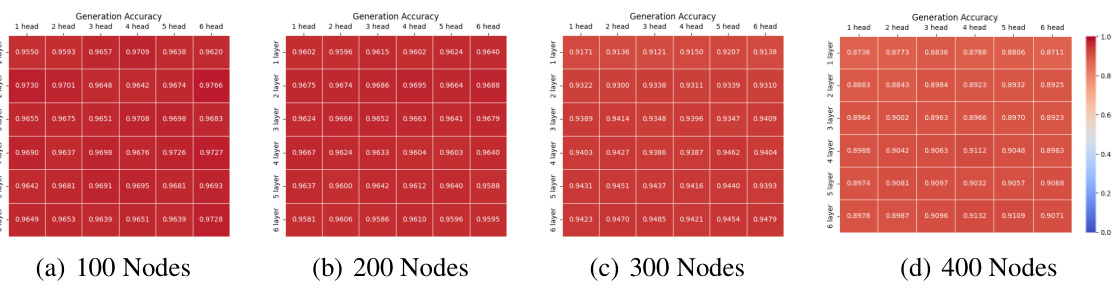

This table shows the cosine similarity between the approximation of FFN (X2WV + Xn)W。 and the sum of FFN (X2WV)W。 and FFN (Xn)W。 for graphs with different numbers of nodes. The approximation is used because FFN (X2WV + Xn)W。 is approximated by the sum of FFN (X2WV)W。 and FFN (Xn)W。. The approximation is surprisingly accurate with cosine similarity ranging from 0.870 to 0.926. This shows the validity of the approximation used in the paper’s theoretical analysis.

In-depth insights#

Autoregressive Planning#

Autoregressive planning explores the fascinating intersection of autoregressive models, like large language models (LLMs), and planning. Instead of relying on explicit planning algorithms, it investigates how the inherent next-step prediction mechanism of autoregressive models implicitly embodies planning capabilities. This approach views planning as a sequential decision-making process, akin to pathfinding in a graph, where each step is a prediction towards a goal. Theoretical analysis often focuses on how the model’s weights implicitly encode information about the graph structure (adjacency and reachability) and how learning dynamics shape these representations. A key question is whether and to what extent such models can learn to reason about transitive relationships, a crucial aspect of sophisticated planning. Empirical evaluations frequently involve pathfinding tasks on simplified graphs or more complex benchmarks like Blocksworld, comparing the model’s performance against an ideal planner. The findings highlight both the impressive implicit planning abilities of autoregressive models and the limitations, particularly in handling complex relationships that require inferential reasoning beyond the directly observed data.

Transformer Expressiveness#

The capacity of transformer models to capture and utilize complex patterns in data, often referred to as “transformer expressiveness,” is a crucial area of research. Theoretical analyses often demonstrate the ability of transformers to represent intricate functions or relations, particularly through their attention mechanisms and multi-layered architecture. However, empirical evaluations show that actual performance is often limited by factors such as the size of the model, the amount and quality of training data, and the specific task being addressed. The expressive power isn’t unlimited; even large models may fail to capture nuanced relations or generalize to unseen data effectively. Furthermore, understanding the learning dynamics within transformers remains essential to unlock their full potential. Investigating how parameters are tuned during training and how they encode information is key. While the theoretical framework suggests significant expressiveness, practical limitations highlight the gap between theory and practical application. Further research into these aspects is needed to better harness the capabilities of transformers.

Path-Finding Limits#

The heading ‘Path-Finding Limits’ suggests an exploration of the boundaries of what autoregressive language models can achieve in path-finding tasks. A core aspect would likely involve analyzing where and why these models fail. Limitations in handling transitive relationships are a probable focus, as the ability to infer indirect connections is crucial for efficient pathfinding. The analysis may reveal shortcomings in how these models represent and process information about the graph structure itself. Incomplete learning of reachability matrices may be another key finding, highlighting that the models might not fully capture all possible paths between nodes. There could also be a discussion of the impact of training data; limited or biased training data might lead to suboptimal pathfinding, particularly in scenarios with complex or less frequently observed paths. Furthermore, it could delve into the relationship between model architecture and pathfinding capabilities, examining whether specific architectures are inherently better suited for this task than others. The analysis of these limitations helps to delineate the current capabilities and identify areas for improvement in the future development of AI planning and reasoning systems.

Empirical Validation#

An empirical validation section in a research paper serves as a critical bridge between theoretical claims and real-world applicability. It should rigorously test the hypotheses and models presented earlier, using carefully designed experiments and appropriate statistical analysis. Robustness checks are essential, demonstrating the model’s resilience to variations in data, parameters, or experimental setup. The selection of metrics and datasets used for validation should be clearly justified and relevant to the paper’s central arguments. The validation process should be transparent and reproducible, with detailed descriptions of methods, data sources, and code availability. Successfully navigating these aspects is crucial; a poorly designed or under-reported validation section undermines the entire paper’s credibility. Ultimately, a strong empirical validation section offers compelling evidence that supports or refutes the paper’s core claims, demonstrating the practical utility and impact of the research.

Future Directions#

The “Future Directions” section of this hypothetical research paper would likely explore several promising avenues. Extending the path-finding model to handle hyper-graphs and hyper-paths would be crucial, as it would allow for more complex planning scenarios that involve multiple preconditions before the next step. This might involve examining how LLMs handle tasks with simultaneous conditions, making the model’s capabilities more applicable to real-world planning. Another key area is improving the LLM’s capacity to deduce transitive reachability, a limitation identified in the study. This might involve exploring architectural improvements to the transformer or using alternative training objectives that directly incentivize the learning of these relationships. Investigating the connection between abstract path-finding and concrete planning tasks, for instance, through specific benchmarks like Blocksworld, could significantly deepen understanding of how LLMs achieve planning. Exploring in-context path-finding and the integration of chain-of-thought and backtracking into the model are further steps to enhance the model’s capabilities. Ultimately, the “Future Directions” section would highlight the need for integrating theoretical analysis and empirical evaluation to unravel the intelligence mechanisms within autoregressive models.

More visual insights#

More on figures

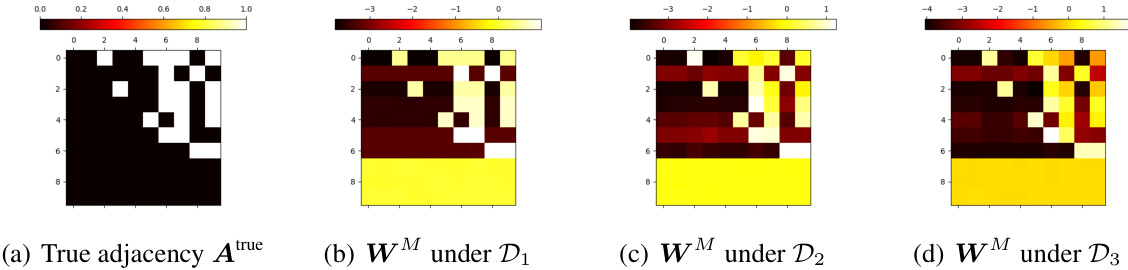

This figure empirically validates the theoretical analysis of how Transformer models learn the observed reachability matrix from training data. It shows a comparison between the true reachability matrix (a), the observed reachability matrices derived from three different training datasets (b-d), and the learned WV weight matrices extracted from trained Transformer models corresponding to those datasets (e-g). The color intensity represents the learned reachability weight, revealing the model’s ability to capture the observed reachability but its limitations in learning transitive reachability.

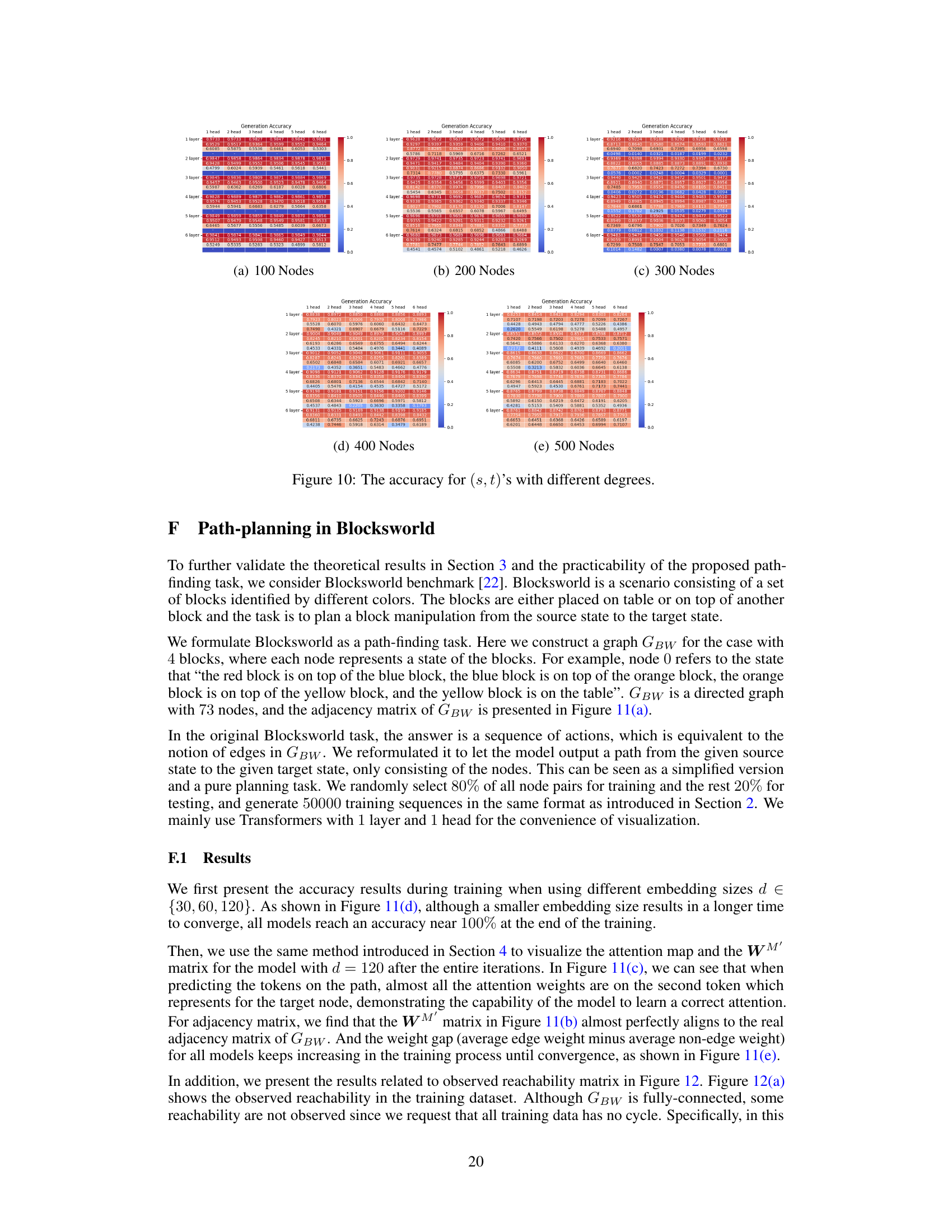

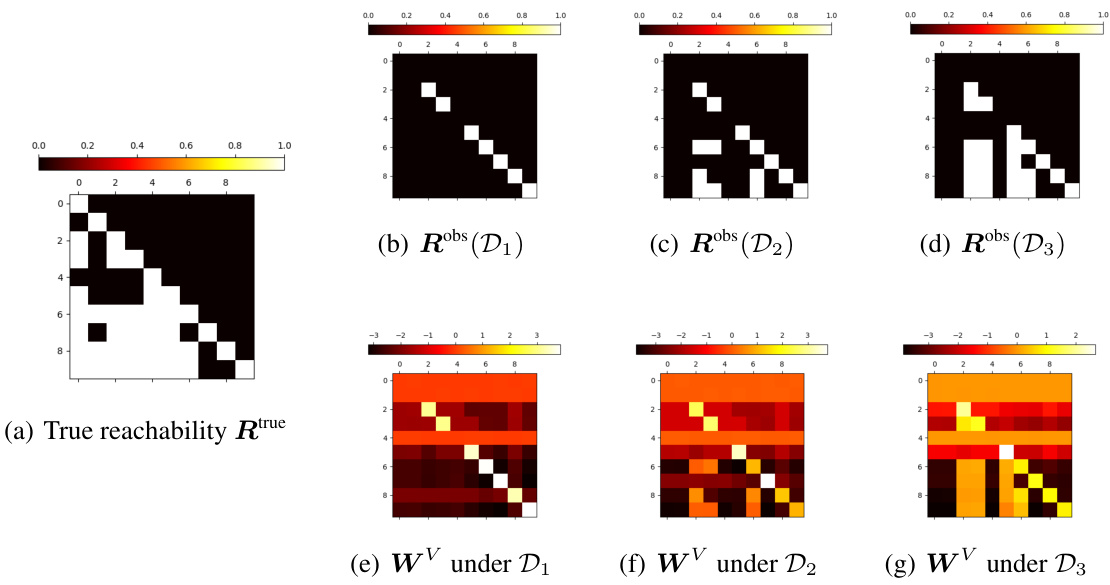

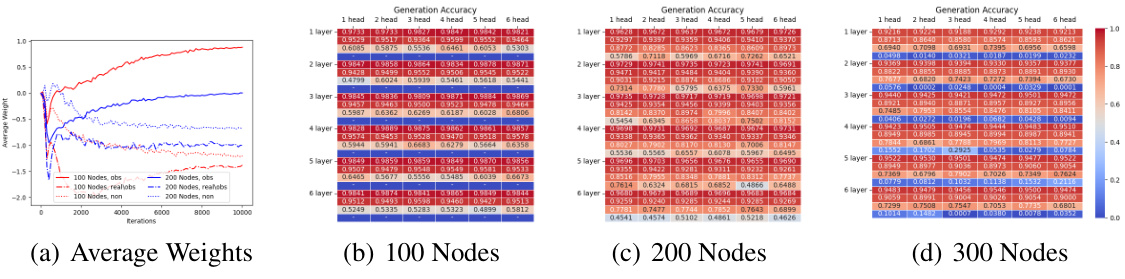

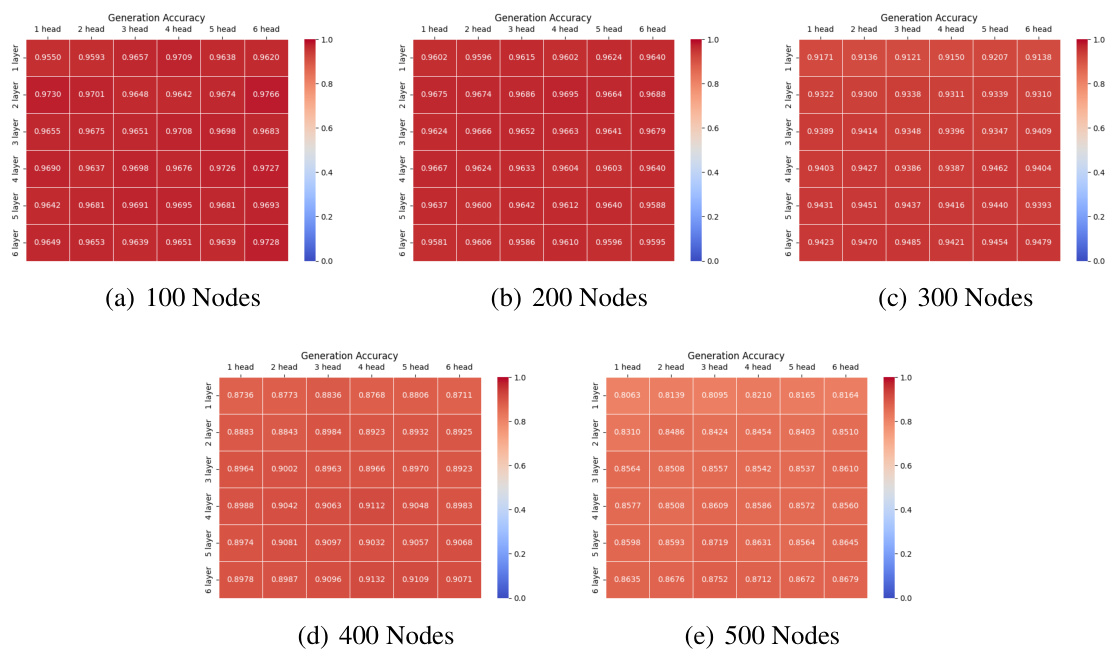

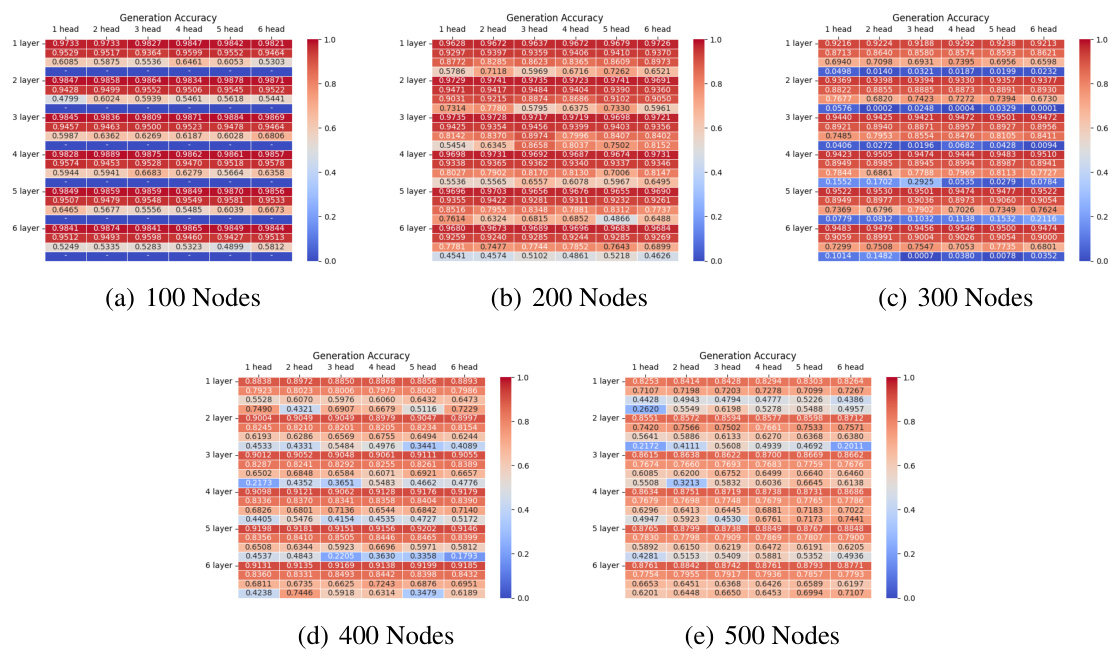

This figure shows the accuracy of the model on test datasets with different numbers of nodes and different numbers of layers and heads. The embedding size is fixed at 120. The accuracy is shown as a heatmap, with each cell representing the accuracy for a specific configuration of the model. The accuracy generally decreases as the number of nodes increases. However, the accuracy remains relatively stable as the number of heads increases, and shows at most a slight improvement as the number of layers increases.

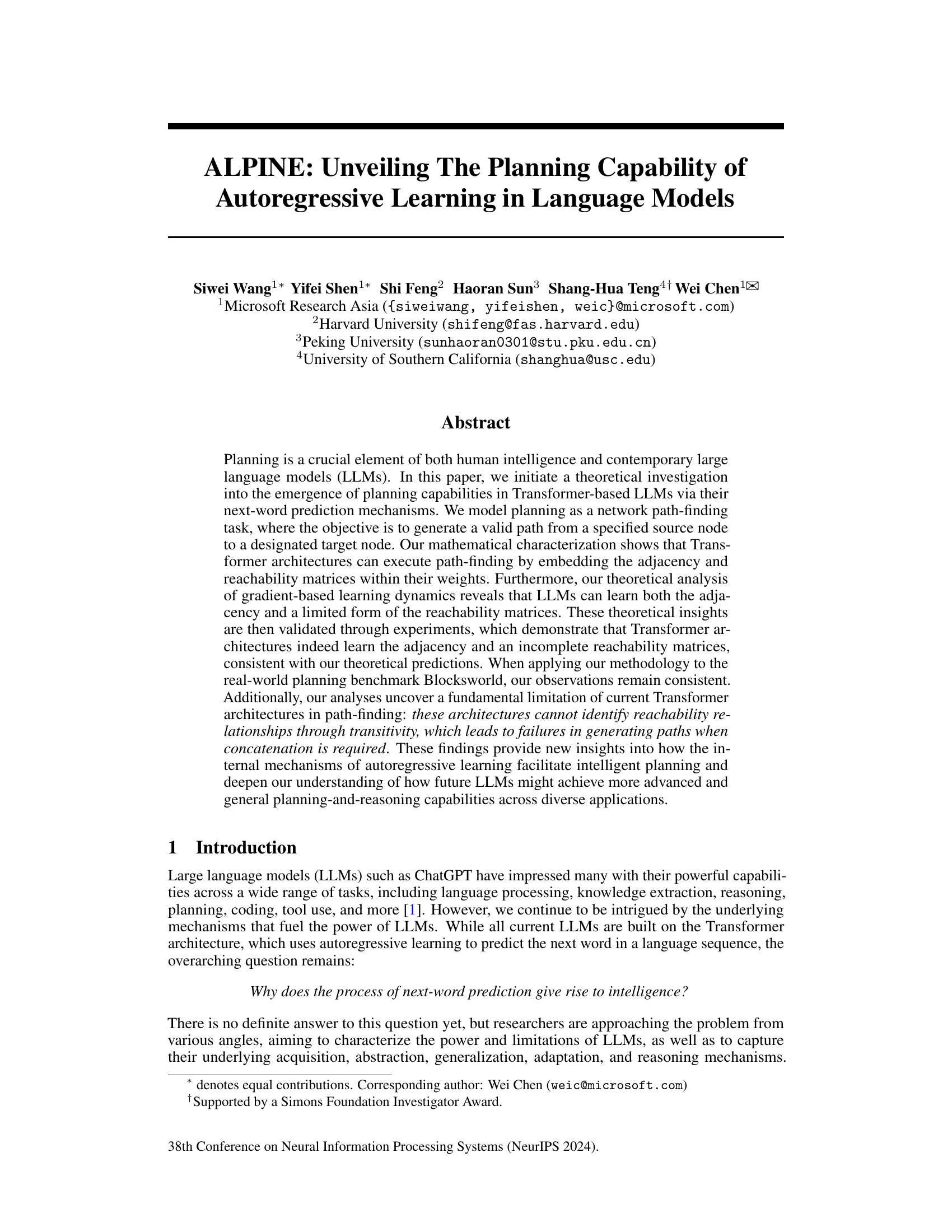

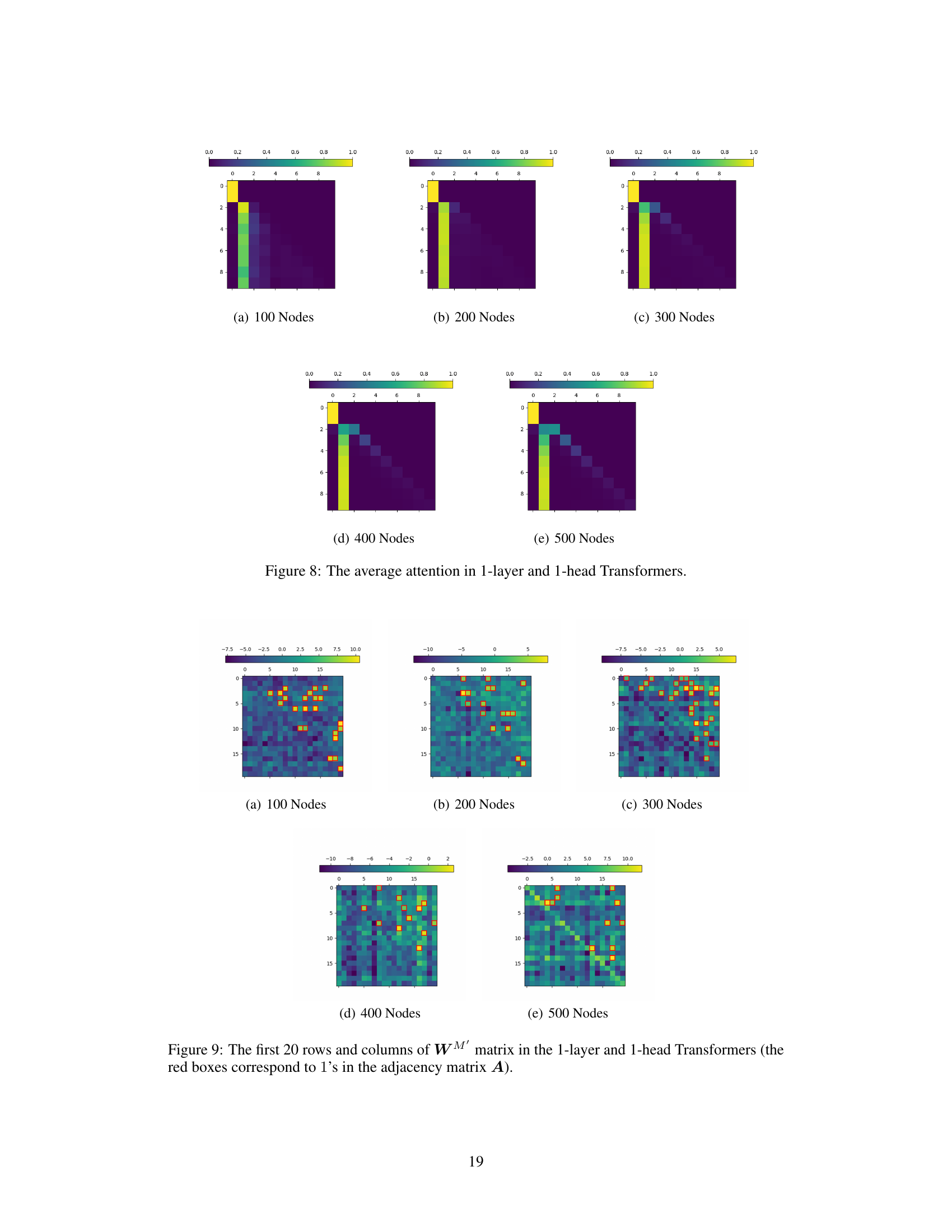

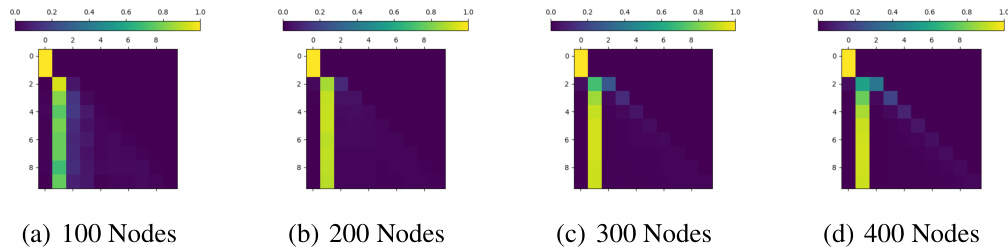

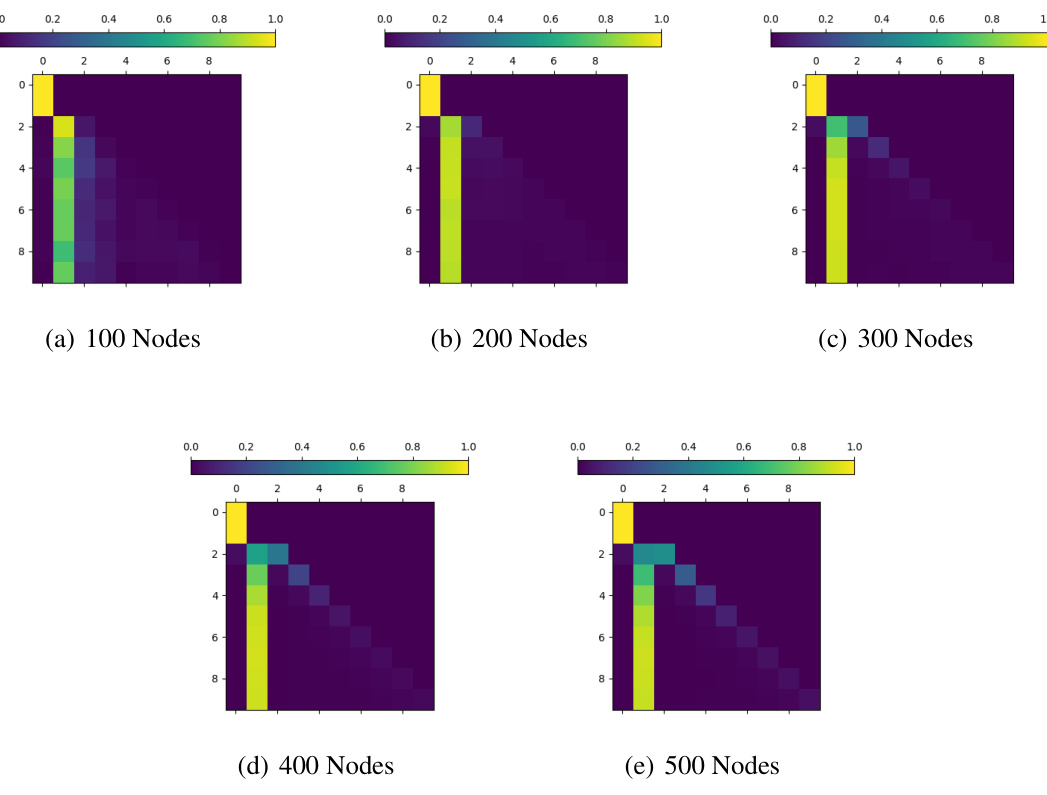

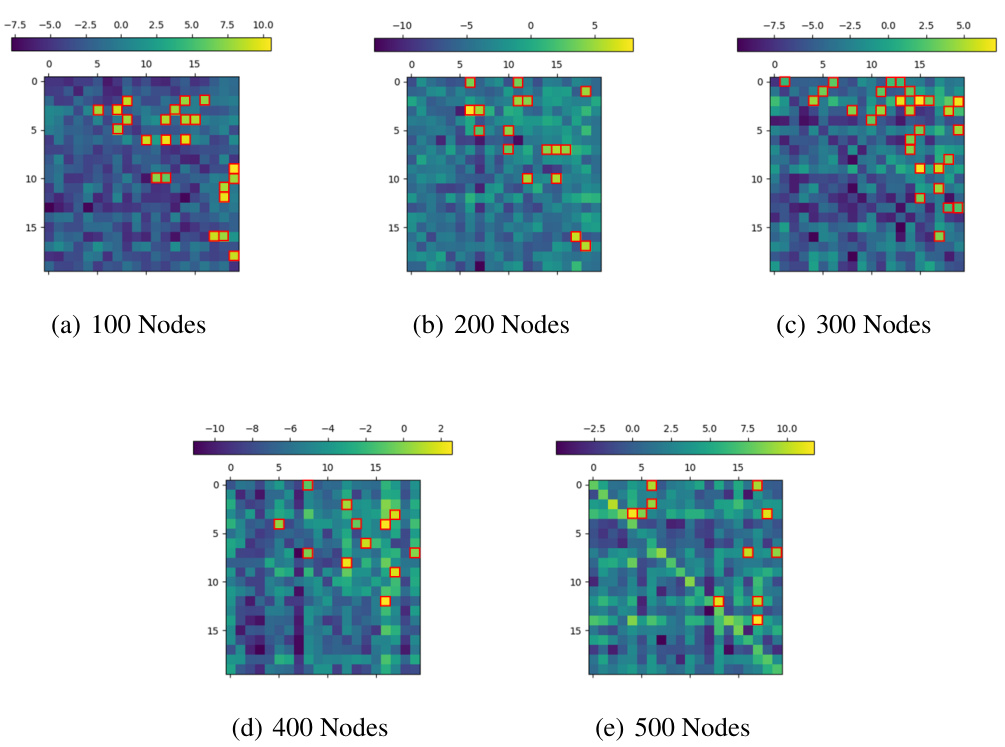

This figure visualizes the average attention weights in one-layer, one-head Transformer models across various graph sizes (100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 nodes). Each heatmap represents the average attention weights when predicting the next token in a path, with the rows corresponding to the current node’s position and the columns indicating the potential next nodes. Darker colors represent higher attention weights, highlighting the nodes most strongly considered when selecting the subsequent node in the path. The results suggest that the attention mechanisms strongly focus on the target node while predicting the next node in the path.

This figure shows the accuracy of the model on test datasets with different numbers of nodes (100, 200, 300, 400, 500) and various Transformer architectures (different numbers of layers and heads). It demonstrates how the model’s performance varies with the size and complexity of the graph and the model’s architecture.

This figure shows the accuracy of the model on test datasets with different numbers of nodes (100, 200, 300, 400) and different numbers of layers and heads in the Transformer architecture. The embedding size is fixed at 120. Each cell in the heatmap represents the accuracy for a specific configuration.

This figure shows the accuracy of the autoregressive Transformer models on test datasets with different numbers of nodes (100, 200, 300, 400) and embedding size d=120. Each sub-figure represents a different number of nodes in the graph, showing the accuracy for different numbers of layers (1-6) and heads (1-6) in the Transformer model. The color scale represents the accuracy, with darker shades indicating higher accuracy. The figure illustrates the performance of various Transformer model configurations in the path-finding task.

This figure presents the accuracy of the test datasets with embedding size d=120, for different graph sizes (number of nodes) and different Transformer configurations (number of layers and number of heads). Each bar represents the average accuracy over multiple trials. The figure demonstrates how the accuracy varies with different network sizes and architecture choices, providing insights into the performance trade-offs.

This figure presents the accuracy of the Transformer models on test datasets with different numbers of nodes (100, 200, 300, 400) and varying numbers of layers and attention heads. The embedding size is fixed at 120. The results showcase the impact of model architecture complexity on path-finding accuracy across different graph sizes.

This figure shows the accuracy of the Transformer models on test datasets with different numbers of nodes (100, 200, 300, 400). The accuracy is shown for various configurations of the Transformer, with different numbers of layers (1-6) and heads (1-6). The heatmap visualizes how accuracy changes across different model architectures and dataset sizes. This helps to understand how model parameters and dataset complexity affect the accuracy in path-finding tasks.

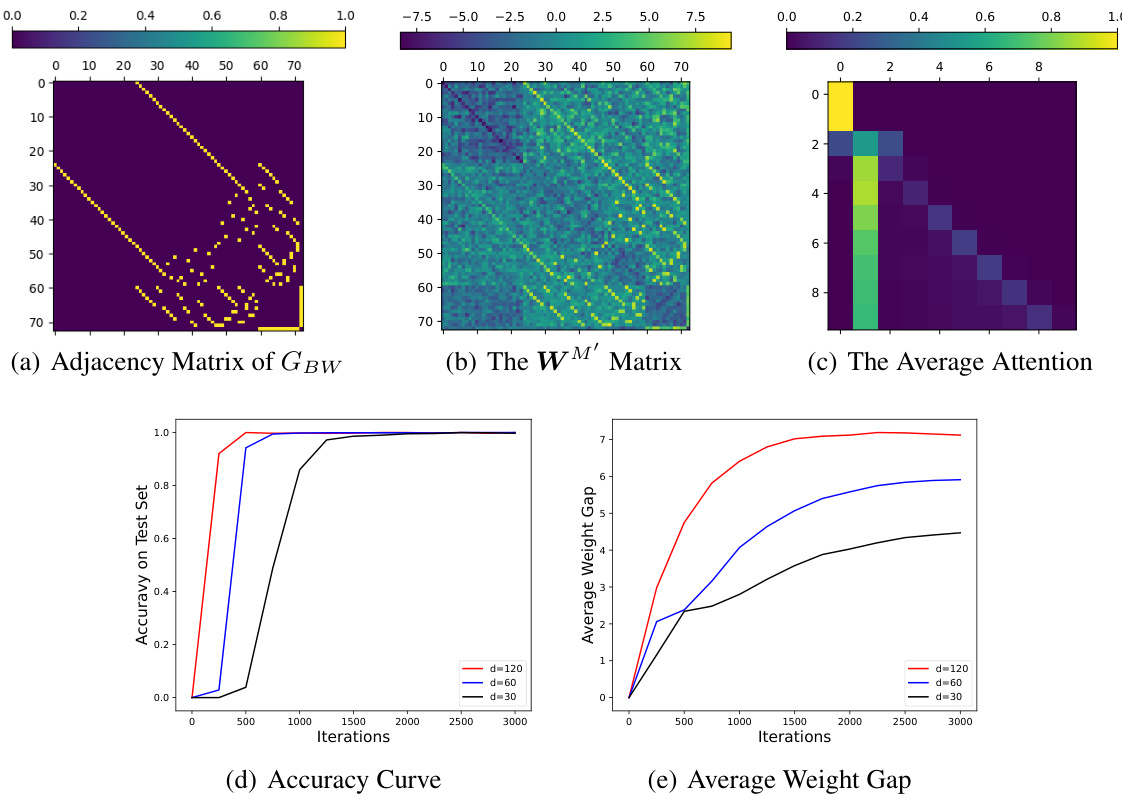

This figure presents the results of an experiment on the Blocksworld benchmark, which is a classic planning task. It shows the adjacency matrix of the graph representing the Blocksworld states and actions, the WM’ matrix learned by a 1-layer, 1-head Transformer model, and the average attention weights during the task. The accuracy curve and average weight gap over training iterations are also shown, demonstrating the model’s learning dynamics and how well it captures the underlying graph structure. The results illustrate the Transformer’s ability to learn the adjacency matrix and its use of attention for planning.

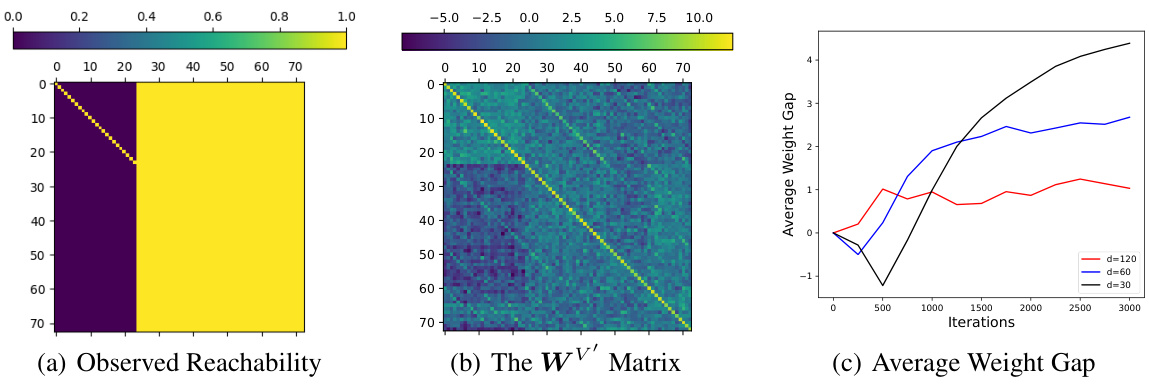

This figure visualizes the observed reachability matrix from the training data and the learned reachability matrix (WV’) from a trained 1-layer, 1-head Transformer on the Blocksworld dataset. It also shows the average weight gap between observed and unobserved reachabilities over training iterations. The results demonstrate the model’s ability to learn observed reachability but its limitation in capturing unobserved or transitive reachability relationships. The heatmap shows the weight matrix, with darker colors indicating stronger reachability relationships learned by the model. The graph displays the gap between the average weights of observed and unobserved reachability relationships over training iterations for different embedding sizes. The consistent increase in this gap signifies the model’s increasing ability to distinguish between observed and unobserved relationships.

Full paper#