↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Sparse-reward reinforcement learning (RL) faces challenges due to the difficulty of exploration and the need for long sequences of actions. Existing skill learning methods are often computationally expensive and struggle with generalization. This necessitates efficient skill extraction and inference for solving complex tasks.

The proposed Subwords as Skills (SaS) method addresses these limitations by leveraging a tokenization technique. Inspired by natural language processing, SaS efficiently extracts skills from demonstrations using Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE). The results show significant speedups in both skill extraction (1000x) and policy inference (100x). Furthermore, skills extracted from a small subset of demonstrations are shown to transfer effectively to new tasks, demonstrating the generalizability of SaS.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is significant because it presents a novel and efficient method for skill extraction in sparse-reward reinforcement learning. Its speed and efficiency are substantial improvements over existing methods, opening avenues for research in more complex and realistic environments. The transferability of the extracted skills across tasks further enhances its value.

Visual Insights#

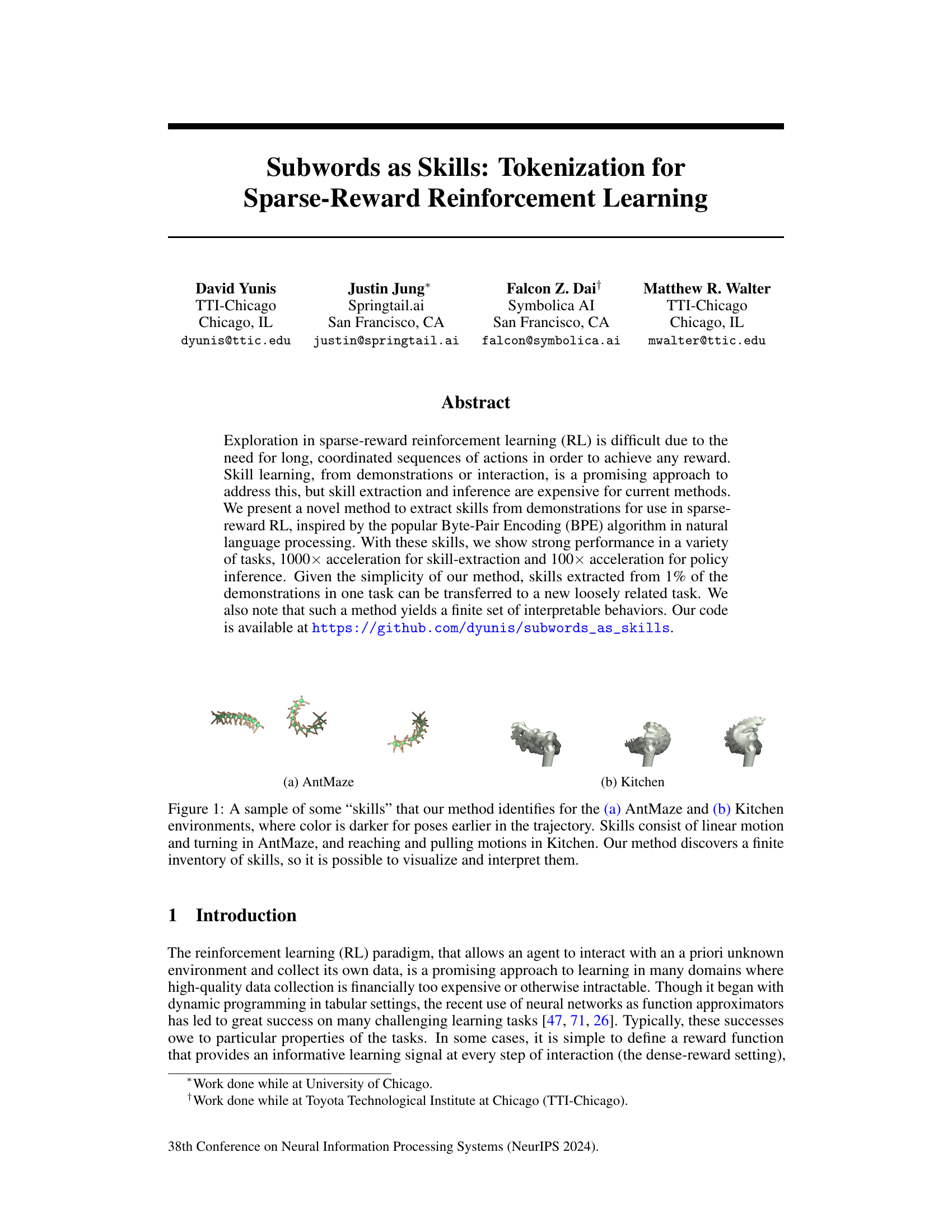

This figure visualizes the skills discovered by the proposed method for the AntMaze-Medium environment. Each skill is represented as a sequence of poses, with darker colors indicating earlier poses in the trajectory. The figure shows a variety of skills, primarily involving linear motion and turning behaviors, demonstrating the ability of the method to extract a diverse set of interpretable skills.

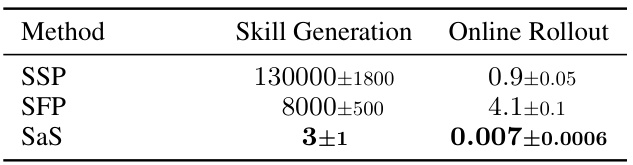

This table compares the time taken for skill generation and online rollout for three different methods: SSP, SFP, and SaS. The results show that SaS is significantly faster than the other two methods for both skill generation and online rollout, highlighting its efficiency.

In-depth insights#

Sparse Reward RL#

Sparse Reward Reinforcement Learning (RL) presents a significant challenge due to the infrequent reward signals, making exploration inefficient. Agents struggle to discover effective action sequences leading to reward because there is little feedback to guide their learning process. This sparsity necessitates innovative solutions beyond standard RL methods. Skill learning emerges as a promising approach, aiming to decompose complex tasks into smaller, more manageable sub-tasks (skills) that yield more frequent, localized rewards. This allows agents to learn effectively within a richer, more informative feedback loop. However, current skill extraction methods often rely on neural networks, resulting in computationally expensive training and inference. Efficient skill representation is crucial; techniques inspired by natural language processing, like tokenization, offer an intriguing direction to extract interpretable and transferable skills from demonstrations with improved efficiency. The goal is to develop methods that enable quick skill extraction and application to various tasks, ideally with transferable skills across different domains. This could revolutionize how we tackle complex, real-world problems that are otherwise intractable using conventional RL techniques.

Subword Skills#

The concept of “Subword Skills” in reinforcement learning presents a novel approach to skill extraction, drawing parallels with subword tokenization in natural language processing. Instead of relying on complex neural networks to extract skills from demonstrations, this method leverages the simplicity and efficiency of byte-pair encoding (BPE). BPE’s iterative merging of frequent action sequences into composite “subword skills” leads to a compact, interpretable representation of behavior. This approach offers significant advantages in terms of speed and scalability, dramatically reducing both skill extraction and policy inference times. Furthermore, the resulting finite set of subword skills facilitates visualization and interpretation, enabling a deeper understanding of the learned behaviors. The ability to transfer skills learned from one task to another, even with limited demonstrations, highlights the potential of this method for tackling sparse reward problems. The approach’s efficiency and generalizability make it a promising direction for advancing skill learning and exploration in reinforcement learning.

BPE for Skills#

The application of Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE), a subword tokenization algorithm from natural language processing, to reinforcement learning’s skill extraction represents a novel and efficient approach. BPE’s capacity to identify recurring action sequences within demonstrations as ‘subword’ skills offers advantages in speed and scalability. Unlike traditional methods reliant on neural networks, BPE’s simplicity translates into significantly faster skill extraction, enabling the creation of a finite set of interpretable skills. This approach is particularly well-suited for sparse-reward environments where exploration is challenging, as it provides a structured action space facilitating more efficient learning. The resulting skills are readily transferable across related tasks, demonstrating the method’s generalizability. Although the assumption that demonstrations contain the elements necessary to reconstruct optimal policies for new tasks needs further investigation, initial results are very promising, highlighting the potential of BPE to revolutionize skill-based reinforcement learning.

Skill Transfer#

The concept of skill transfer in reinforcement learning is crucial for efficient learning and generalization. The paper’s approach, using a tokenization method to identify subword-like skills, offers a unique perspective on this challenge. The method’s strength lies in its independence from observation data, allowing skills learned in one environment to be potentially transferred to another with a shared action space. This is a significant advantage over methods reliant on observation-conditioned skills, which are typically task-specific. Success in transferring skills learned from AntMaze to a different AntMaze task demonstrates the robustness of the approach. However, the degree of success may depend on the similarity between source and target tasks, and further investigation is needed to explore the limits of this transferability. The inherent simplicity and speed of the skill-extraction process are key benefits, enabling rapid experimentation and wider applicability. The method’s reliance on a common action space, rather than observational data, presents both a strength (generalizability) and a potential limitation (contextual understanding).

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work on subword tokenization for sparse-reward reinforcement learning could explore several promising avenues. Extending the methodology to continuous action spaces without relying on discretization would significantly enhance the applicability and robustness of the approach. Investigating alternative tokenization techniques beyond BPE, such as WordPiece or Unigram, and their impact on skill learning and transfer is warranted. Furthermore, developing methods to automatically determine optimal hyperparameter values (skill length, vocabulary size, etc.) would improve the ease of use and effectiveness. Finally, exploring the integration of observation data into the skill-extraction process could lead to more context-aware and easily transferable skills, potentially bridging the gap between observation-free and observation-conditioned methods.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the overall process of the proposed method. It starts with demonstrations (sequences of actions) from a similar task. These are tokenized using a method analogous to Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) commonly used in natural language processing. This tokenization process identifies recurring action sequences as ‘skills’. These skills are then used as the new action space for reinforcement learning in a new task, allowing for improved sample efficiency and transferability across domains. Only a common action space between the original demonstrations and the new task is required. The method accelerates skill extraction and policy inference.

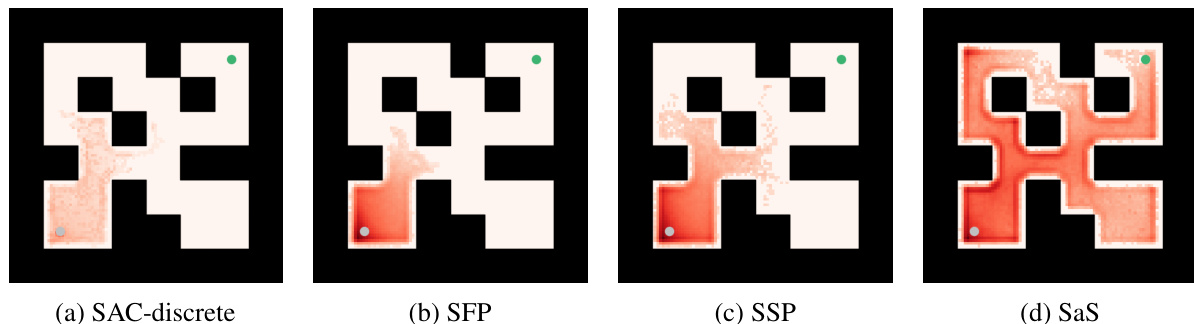

This figure visualizes the state visitation in online RL on AntMaze Medium for four different methods (SAC-discrete, SFP, SSP, and the proposed SaS method) during the first 1 million timesteps. It highlights that SaS explores the maze more extensively than the other methods, demonstrating superior exploration behavior.

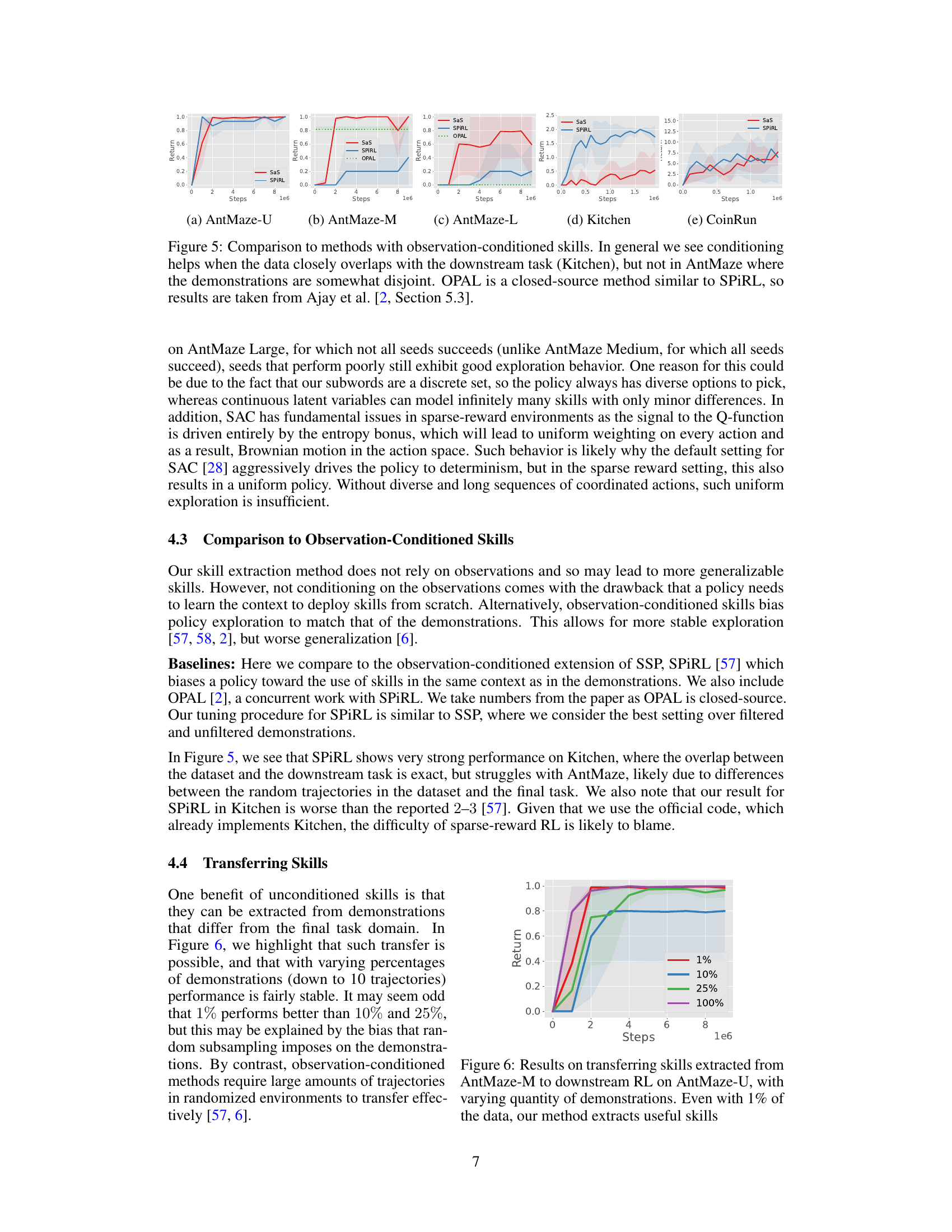

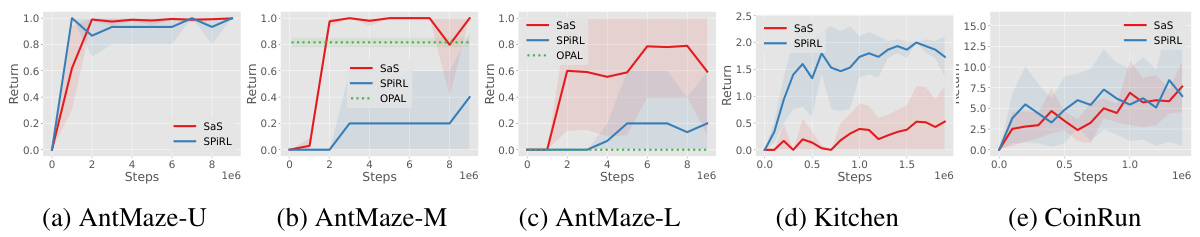

This figure compares the performance of the proposed Subwords as Skills (SaS) method against other methods for online reinforcement learning on AntMaze and Kitchen tasks. It specifically focuses on comparing SaS with methods that use observation-conditioned skills (skills that are conditioned on the observed state). The results indicate that observation conditioning can be beneficial when the training data and the test task are similar (as in the Kitchen environment), but it may not be advantageous when there is a mismatch between the training data and test task (as in the AntMaze environment). OPAL, a closed-source method, is also included in the comparison.

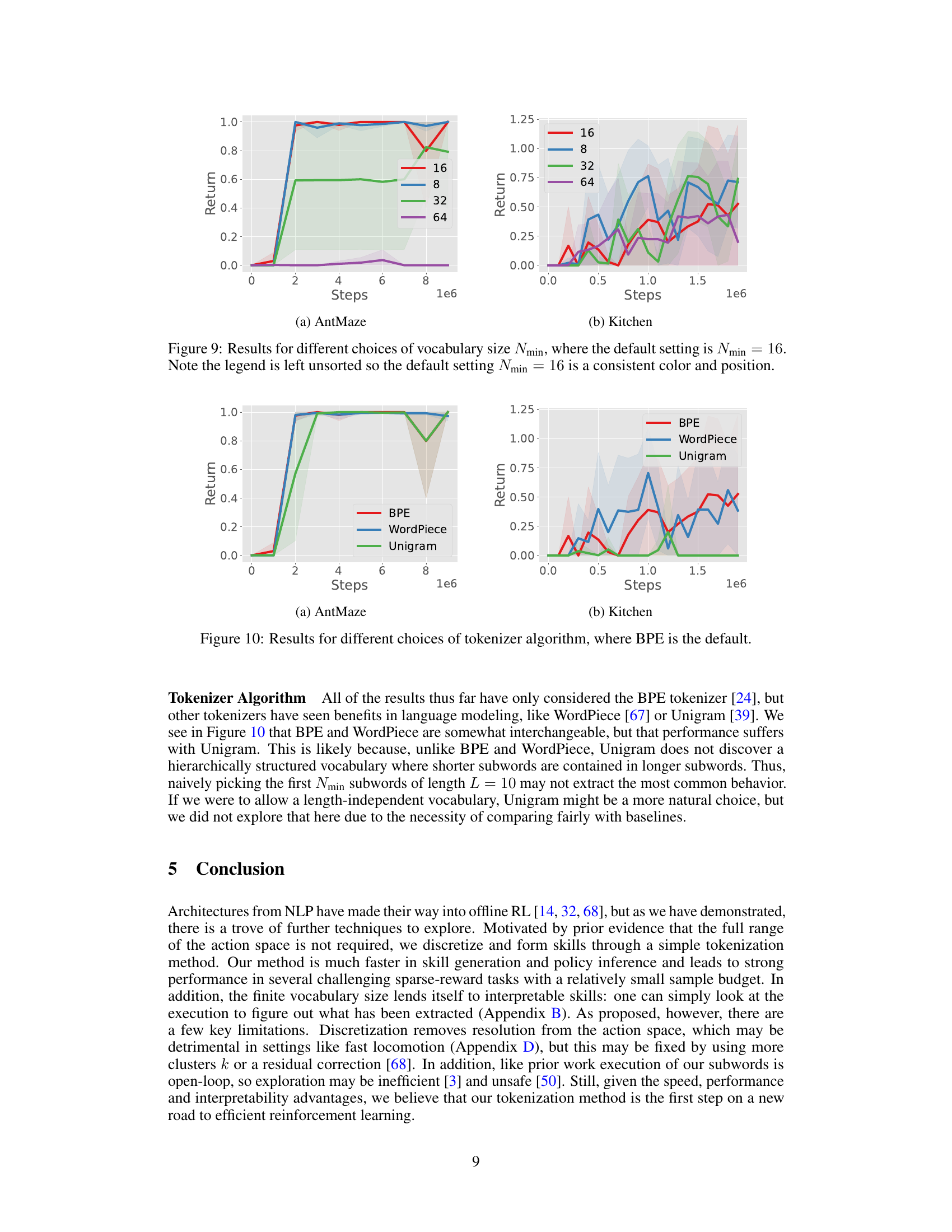

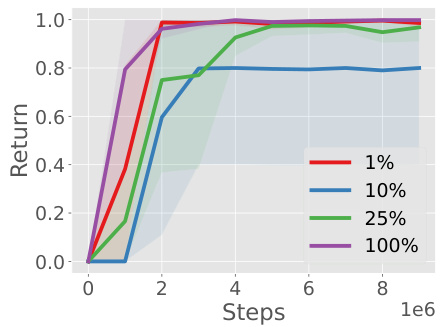

This figure displays the results of an experiment on transferring skills learned from one AntMaze environment (AntMaze-M) to a different but related AntMaze environment (AntMaze-U). The experiment varied the percentage of demonstrations used to extract skills (1%, 10%, 25%, and 100%). The x-axis represents the number of training steps, and the y-axis shows the return (reward) achieved by the RL agent. The results show that even with a small percentage of demonstrations (as low as 1%), the method is still able to extract useful skills that enable good performance in the new environment.

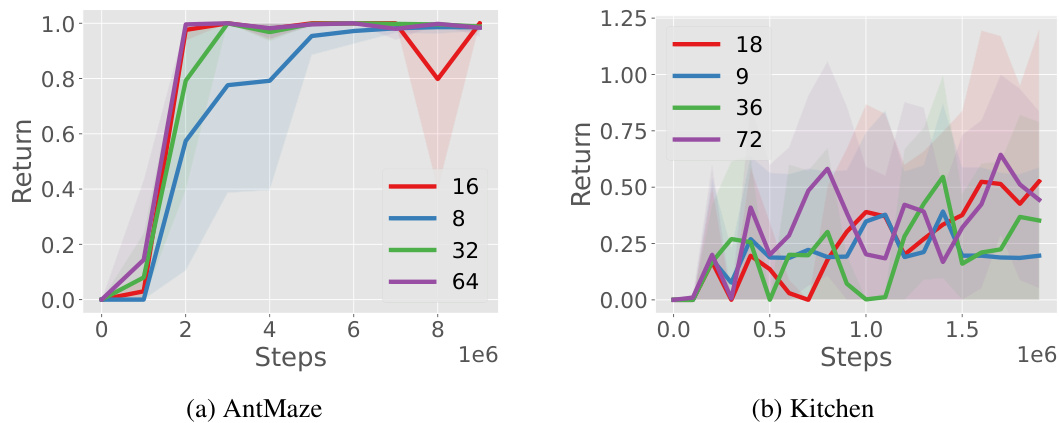

This figure shows the ablation study on the hyperparameter k (number of clusters for k-means) in the proposed method. Subplots (a) and (b) present the results for AntMaze and Kitchen environments, respectively. The x-axis represents the training steps, and the y-axis represents the return. Different lines represent different values of k. The default value used in the paper is k=2*dact, where dact is the number of degrees of freedom in the action space. The figure demonstrates the impact of varying k on the performance of the reinforcement learning agent. The results show that the default setting of k performs well across both environments.

This figure shows the ablation study on the hyperparameter k, which represents the number of clusters used for discretizing the action space before applying the Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) algorithm. The plots show the return achieved in the AntMaze and Kitchen environments for different values of k, keeping other hyperparameters constant. The default setting, k=2*dact (where dact is the degrees of freedom of the action space), is highlighted. The results indicate that the default setting works well; however, significantly larger values of k lead to shorter skills as fewer common subwords are found.

This figure shows the ablation study on the hyperparameter k (number of clusters for k-means). The left plot shows AntMaze results and the right plot shows Kitchen results. The default value used in the paper is k=2dact, where dact is the number of degrees of freedom in the action space (8 for AntMaze, 9 for Kitchen). The plots show the return over training steps for different values of k. It indicates that the choice k=2dact is reasonable.

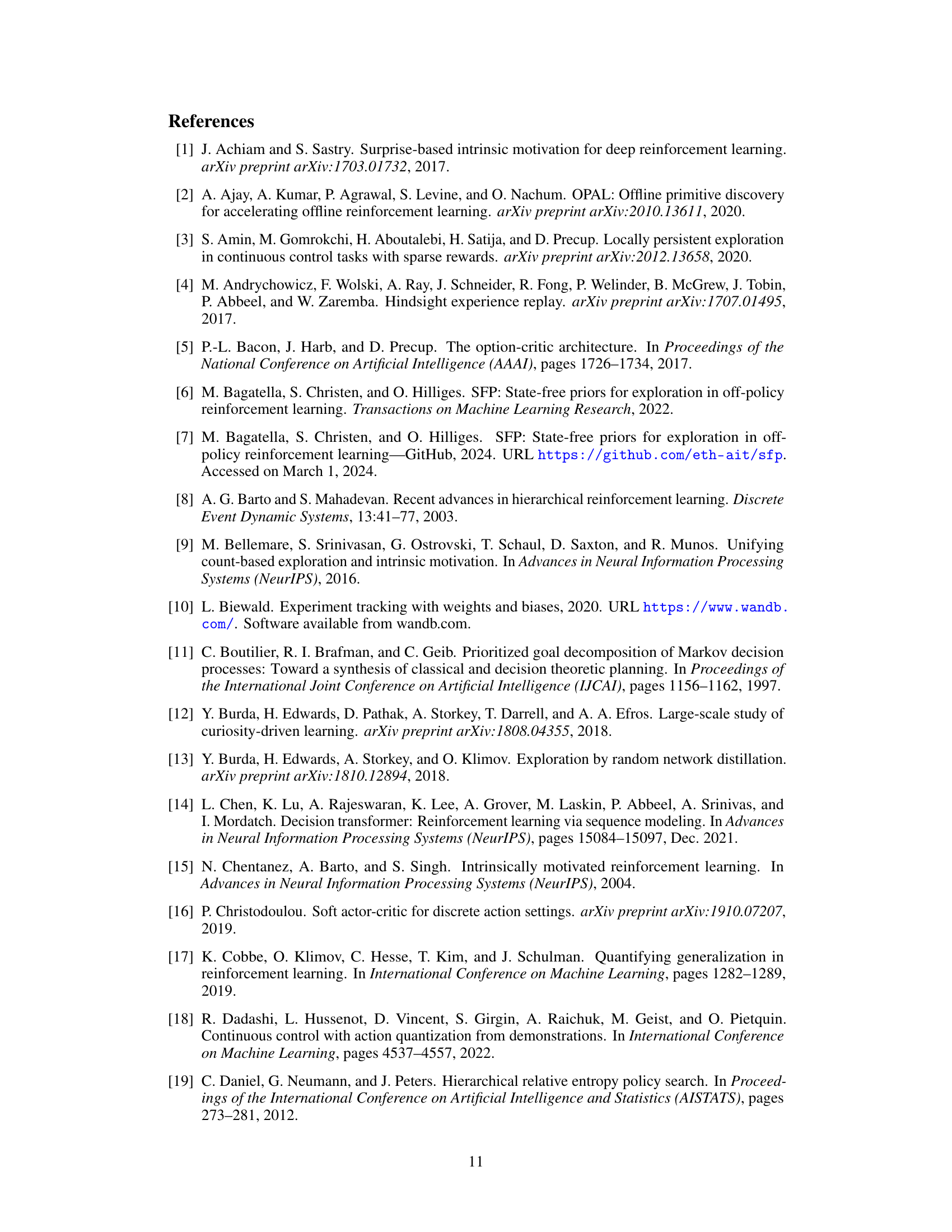

This figure compares the performance of three different subword tokenization algorithms (BPE, WordPiece, and Unigram) on two reinforcement learning tasks (AntMaze and Kitchen). The y-axis shows the cumulative reward obtained, and the x-axis shows the number of training steps. The shaded areas represent the standard deviation across multiple runs. The results demonstrate that BPE and WordPiece perform similarly, while Unigram yields substantially lower returns.

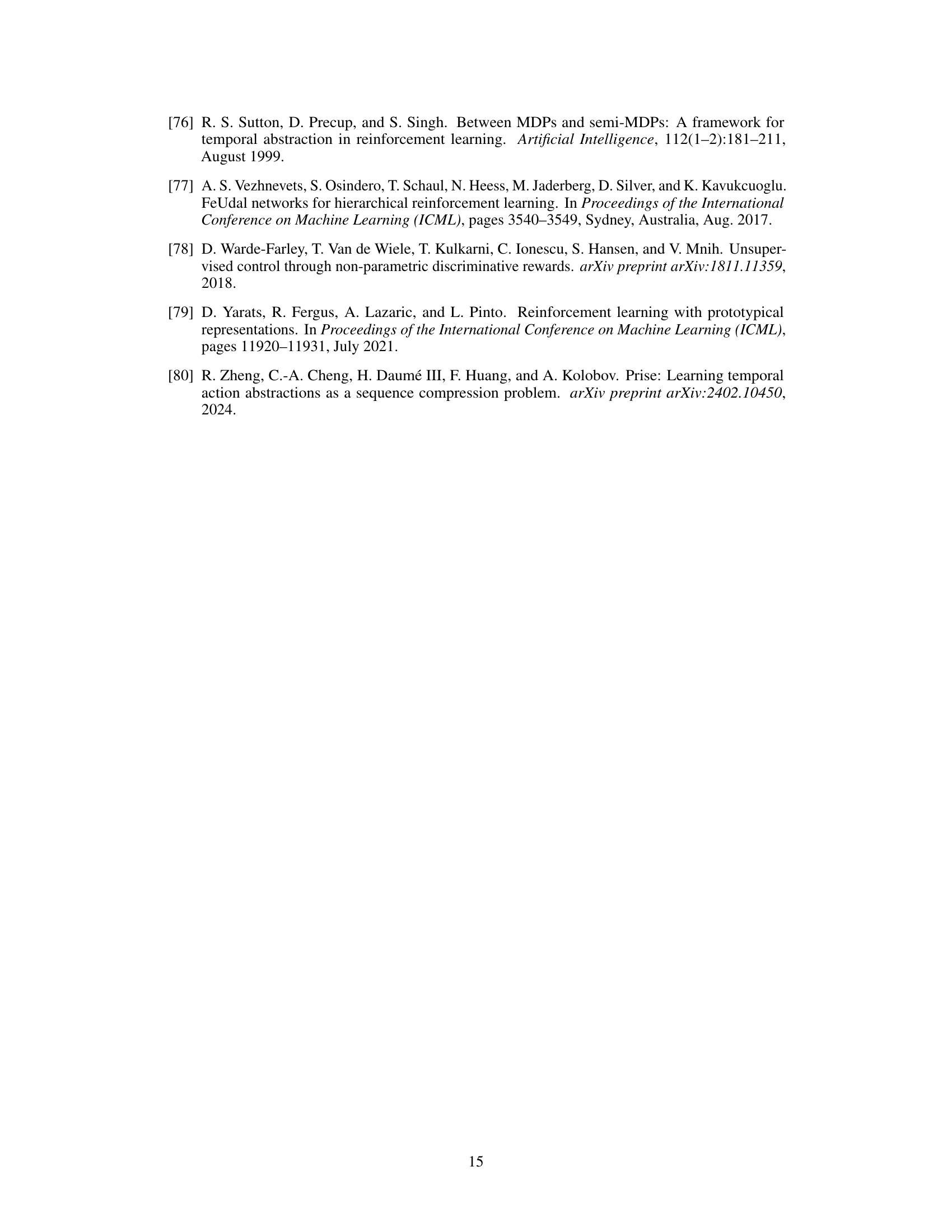

This figure shows the five offline reinforcement learning environments used in the paper’s experiments: AntMaze (small, medium, and large versions), Kitchen, and CoinRun. The figure highlights the visual appearance of each environment and provides clarifying information about the starting location and goal position for the AntMaze environments. These environments vary in complexity, from the relatively simple AntMaze Umaze to the more challenging Kitchen and CoinRun.

This figure visualizes the skills discovered by the Subwords as Skills (SaS) method in the AntMaze-M environment. Each skill is represented as a sequence of poses, with darker colors indicating earlier poses in the trajectory. The visualization shows that the learned skills consist primarily of linear movements and turns, showcasing the SaS method’s ability to extract interpretable and meaningful behaviors.

This figure visualizes the skills learned by the Subwords as Skills (SaS) method in the AntMaze-Medium environment. Each image represents a single skill, a temporally extended action identified by SaS. The color gradient within each image shows the sequence of poses within the skill, darker colors corresponding to earlier poses in the sequence. The skills shown consist mainly of combinations of linear movements and turns, illustrating the method’s ability to capture distinct movement primitives from the demonstration data.

This figure visualizes the state visitation of different RL methods on AntMaze Medium environment for the first 1 million timesteps. It compares SAC-discrete, SFP, SSP, and the proposed SaS method, showing that SaS explores the maze more extensively and consistently across different seeds.

This figure shows the results of experiments conducted on the Hopper locomotion environment from D4RL. The experiments varied the number of clusters (k) used for discretizing the action space in the skill extraction method. The x-axis represents the number of training steps, and the y-axis represents the cumulative return achieved by the agent. The different colored lines represent different values of k (12, 6, 24, and 48). The shaded regions represent the standard deviation across multiple runs. The results indicate that finer discretization helps up to a certain point, after which it hurts performance. One hypothesis is that finer levels of discretization naturally result in shorter skills, as there are fewer repeated subwords. This can make reinforcement learning in a dense reward environment easier, but not necessarily in a sparse-reward environment.

This figure shows the performance of the proposed method on the Hopper environment using demonstration data of varying quality. The three lines represent results using demonstrations from a random policy (‘Random’), a policy midway through training (‘Medium’), and a policy at the end of training (‘Expert’). The x-axis represents the number of training steps, and the y-axis represents the average return. The figure demonstrates that demonstrations from a well-trained policy (‘Expert’) lead to the best performance, but even the ‘Random’ demonstrations achieve reasonably competitive results.

Full paper#