↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Precision matrix estimation is vital for understanding relationships in high-dimensional data, but traditional methods struggle with limited samples. This is particularly problematic in fields like genetics, where datasets often have far fewer samples than variables. Existing meta-learning techniques, while improving sample efficiency, lack computational efficiency. This creates challenges for real-world applications requiring quick, accurate results.

FasMe offers a novel solution. By first extracting “meta-knowledge” from multiple related tasks using multi-task learning, it reduces reliance on large samples for the target task. A maximum determinant matrix completion algorithm, applied using the meta-knowledge, further enhances efficiency. Experiments demonstrate FasMe’s superior performance in speed and accuracy compared to other methods, especially in small sample settings. This makes it a powerful tool for analyzing high-dimensional data with limited samples, advancing various applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers dealing with high-dimensional data and small sample sizes, common in fields like genetics and neuroscience. It offers a novel, efficient solution to precision matrix estimation, a fundamental problem in these areas, significantly advancing the state-of-the-art and opening avenues for improved analysis and predictions in data-scarce scenarios.

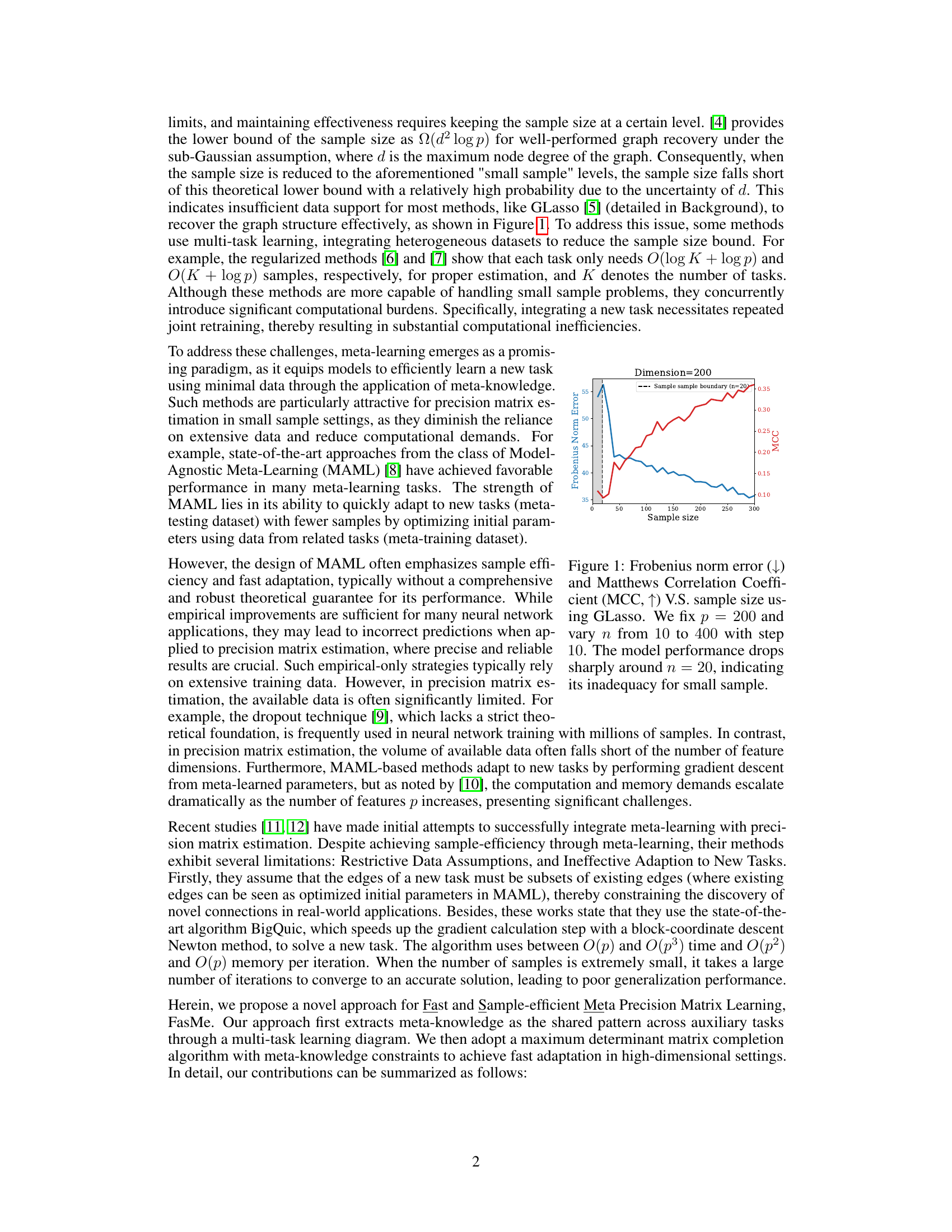

Visual Insights#

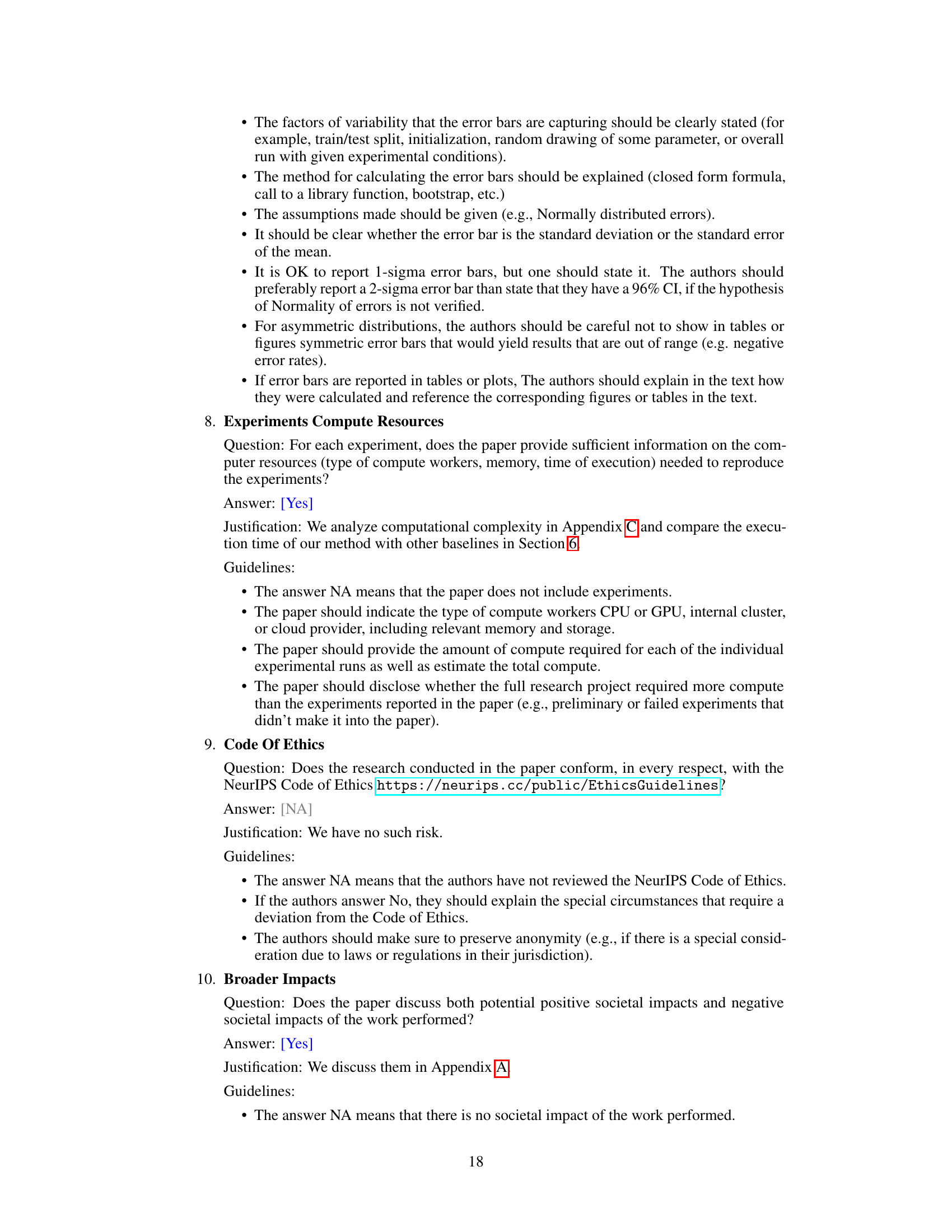

This figure shows the performance of GLasso, a popular method for precision matrix estimation, under different sample sizes. The x-axis represents the sample size (n), and the y-axis shows two metrics: Frobenius norm error (lower is better) and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC, higher is better). The plot demonstrates that GLasso’s performance degrades significantly when the sample size (n) is smaller than 20, which is far less than the number of features (p=200). This highlights the challenges of precision matrix learning in small sample settings.

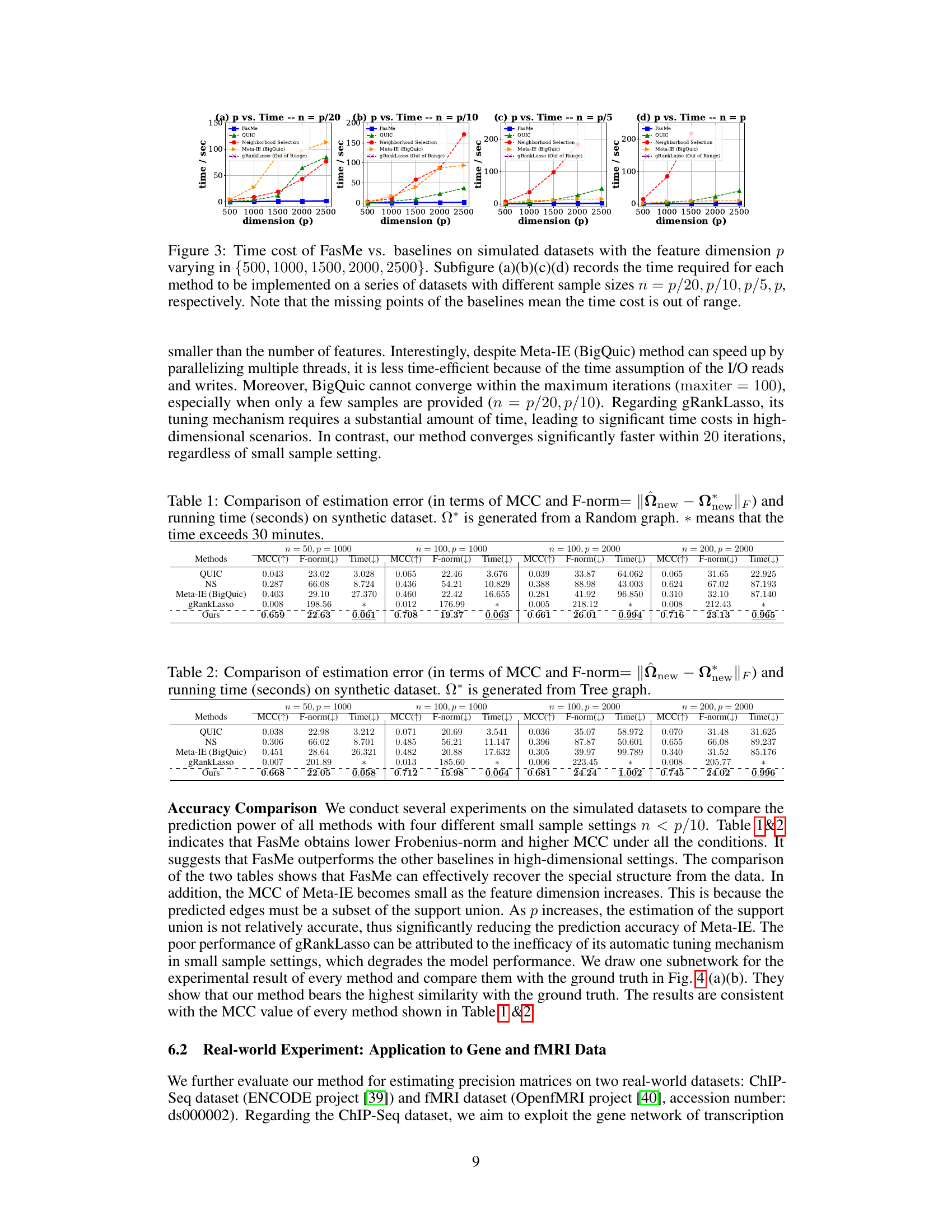

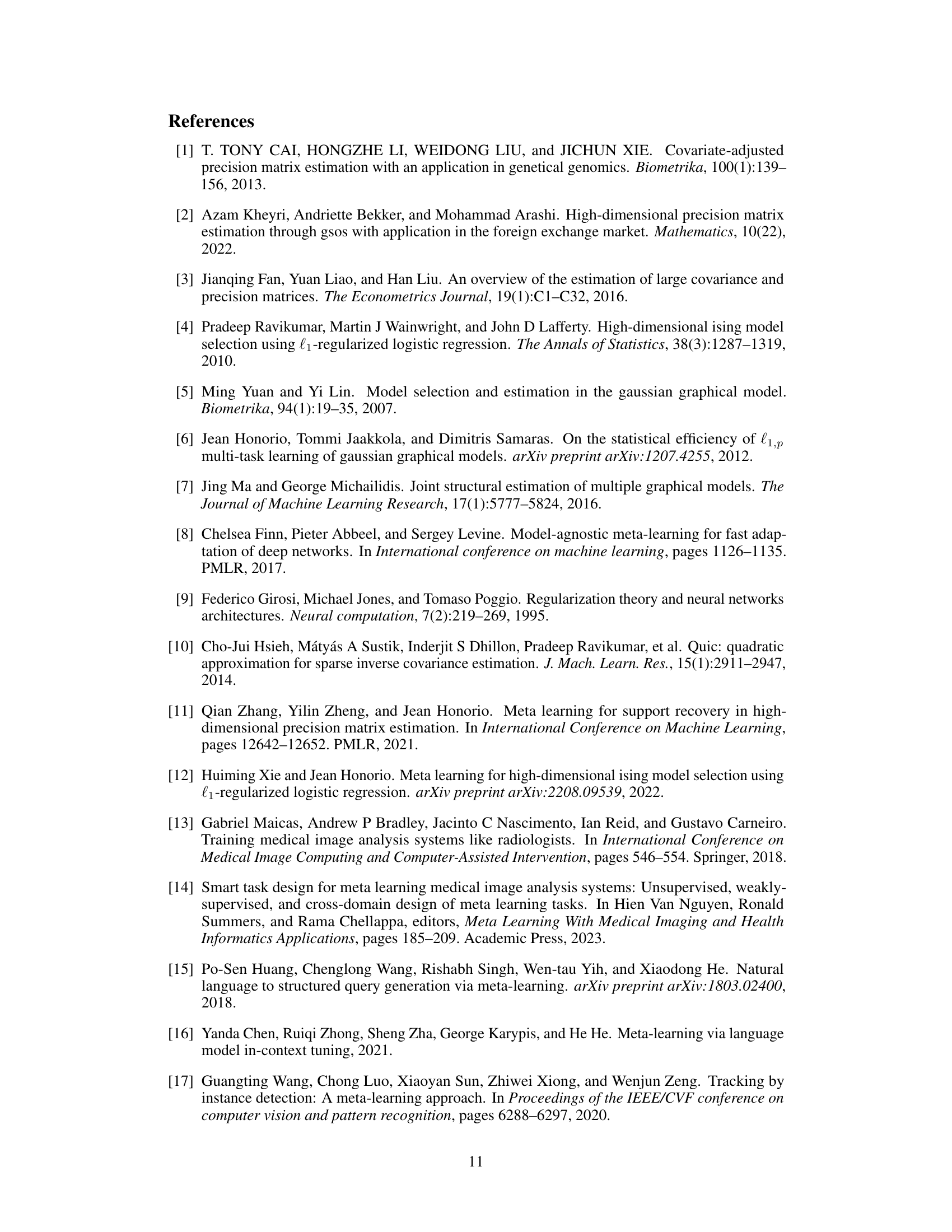

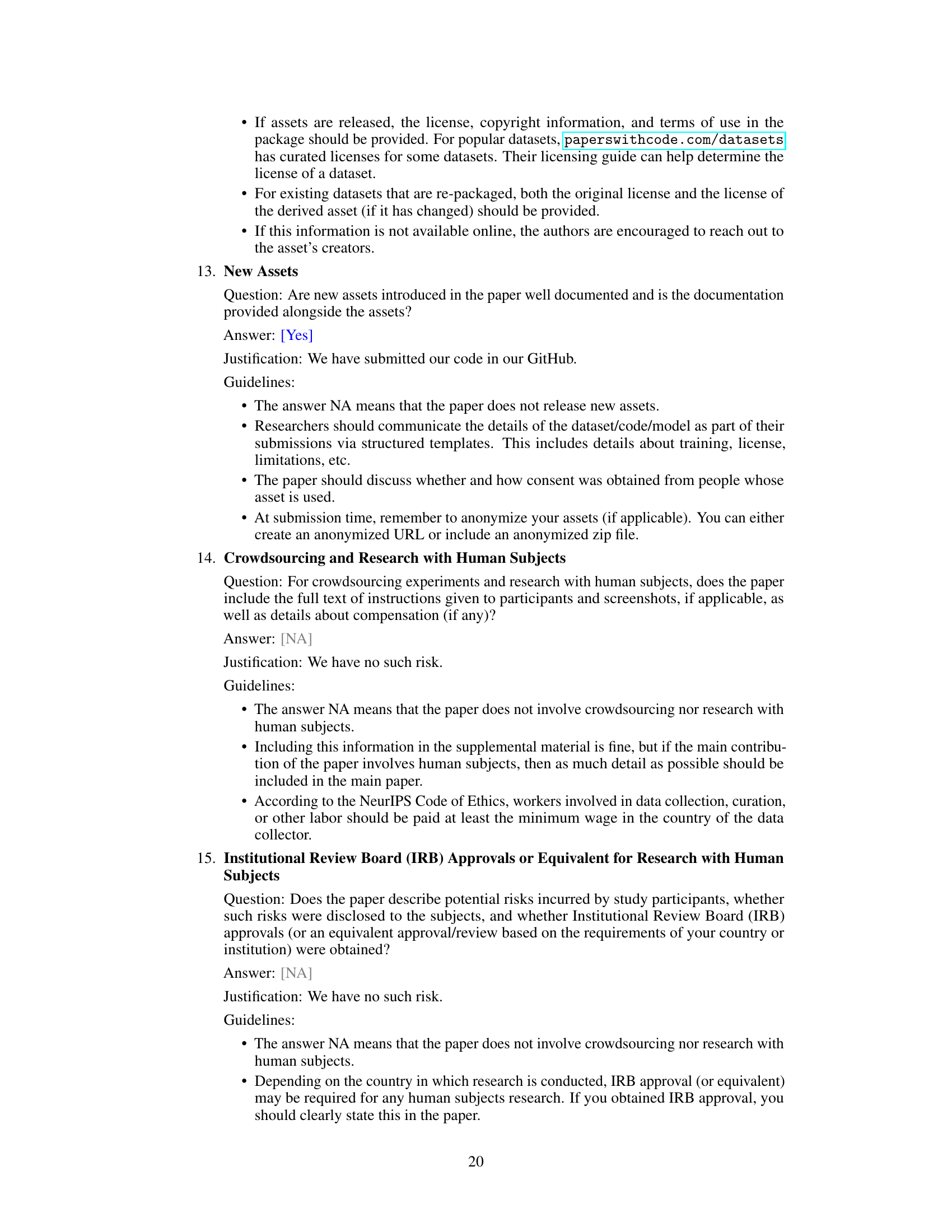

This table presents a comparison of the estimation error and running time of different methods on a synthetic dataset. The estimation error is measured using two metrics: Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) and Frobenius norm (F-norm). The running time is given in seconds. The dataset used for this comparison is a synthetic dataset generated from a random graph. An asterisk (*) indicates that the running time exceeded 30 minutes.

In-depth insights#

Meta-Learning Speedup#

The concept of ‘Meta-Learning Speedup’ in a research paper would likely explore techniques to accelerate the meta-learning process. This could involve optimizing algorithms for faster convergence, reducing computational costs, or leveraging parallel processing. A key aspect would be the trade-off between speed and accuracy. Rushed meta-learning might sacrifice model quality. The discussion might also cover the scalability of the speedup methods. Does the speed increase proportionally with dataset size or problem complexity? Theoretical guarantees of convergence speed and performance bounds would be essential to establish the reliability of any proposed speedups. The paper could further analyze the impact of the speedup on the overall meta-learning framework, particularly regarding the downstream tasks. Finally, empirical evaluations on multiple datasets would showcase the practical speedup and how it compares to existing methods. Benchmarking against state-of-the-art baselines is crucial to demonstrate true improvement.

MDMC Matrix Solving#

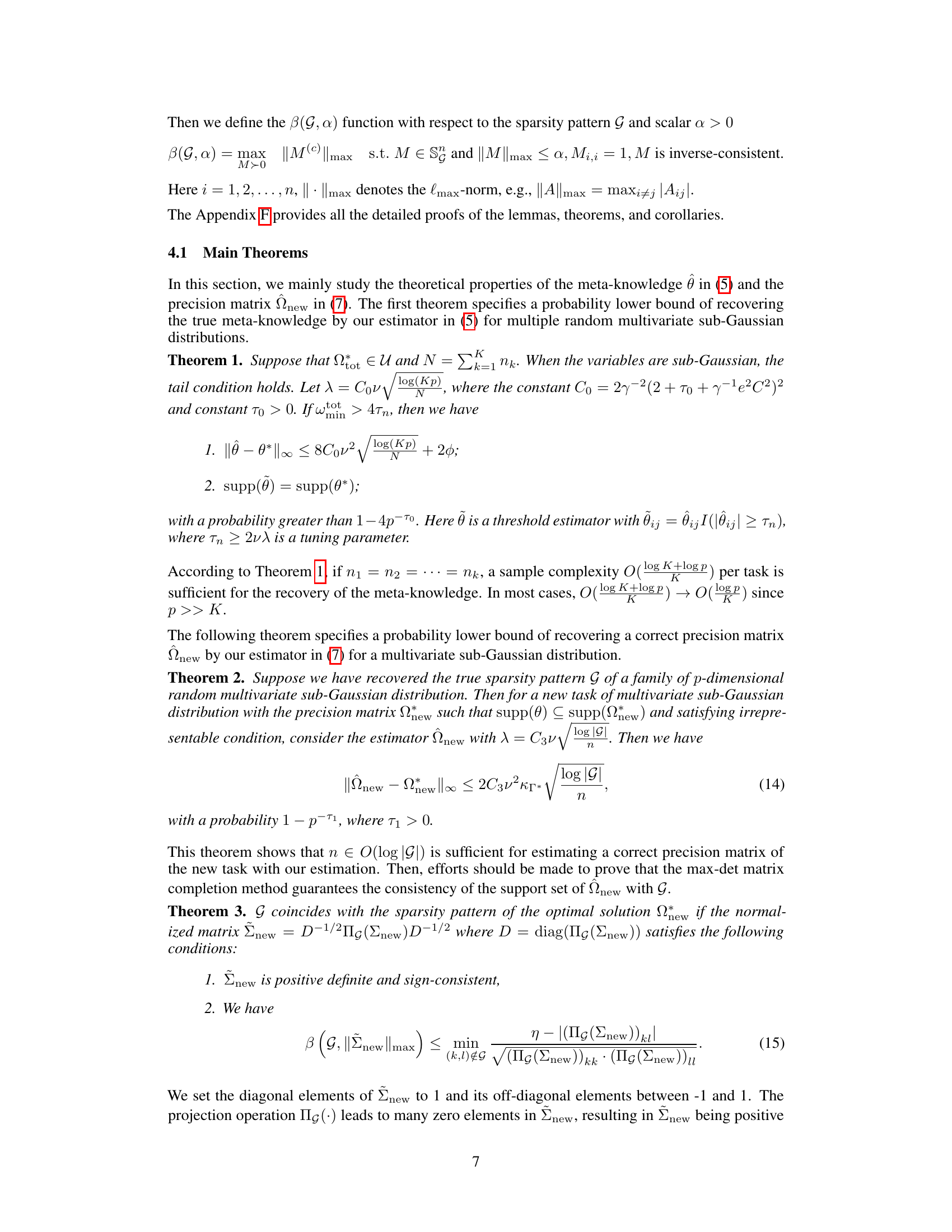

The heading ‘MDMC Matrix Solving’ suggests a focus on solving a matrix completion problem using Maximum Determinant Matrix Completion (MDMC). This method is particularly relevant for scenarios with high-dimensional data and limited samples, which is a common challenge in precision matrix estimation. MDMC aims to recover a complete matrix from a partially observed one by maximizing its determinant, which is directly related to the matrix’s conditioning and invertibility. This is a crucial aspect for precision matrix estimation because the inverse covariance matrix must be well-conditioned for reliable estimations of conditional dependencies. The use of MDMC likely reflects a strategy to overcome the ill-conditioned nature of sample covariance matrices in high-dimensional small sample settings, hence improving the reliability and accuracy of the precision matrix estimation. The approach probably leverages the inherent sparsity structure often present in such datasets, allowing for efficient computation via techniques like graph algorithms or specialized optimization methods. This is important because a straightforward solution without considering sparsity would be computationally infeasible in high dimensions.

Small Sample Theory#

Small sample theory in statistical learning addresses challenges arising when the number of observations is limited relative to the number of variables. Traditional statistical methods often fail in this context due to high variance and bias. This necessitates the development of new theoretical frameworks and estimation procedures. Key research focuses on the establishment of lower bounds for sample complexity, identifying the minimum number of samples required to achieve accurate estimates, and on deriving consistent estimators capable of providing reliable results even with limited data. Regularization techniques, such as LASSO and Ridge regression, are often employed to mitigate overfitting and improve estimation accuracy. Meta-learning approaches leverage insights from related tasks to enhance sample efficiency and improve performance on new tasks with limited data. These methods improve generalization ability by transferring knowledge between tasks, enhancing statistical power in the small sample setting. The theoretical analysis often involves high-dimensional probability theory and concentration inequalities to provide rigorous guarantees on estimation performance and the generalization ability.

Benchmark Superiority#

A ‘Benchmark Superiority’ section in a research paper would systematically demonstrate that a newly proposed method outperforms existing state-of-the-art techniques. This would involve a rigorous comparison across multiple metrics and datasets. A strong benchmark superiority analysis should not only showcase higher accuracy but also highlight improvements in efficiency, such as reduced computational time or memory usage. The selection of benchmarks is crucial; they should represent the current best practices and cover a variety of scenarios. The paper should clearly define the metrics used for comparison, ensuring these metrics are appropriate and relevant to the problem being solved. Furthermore, a discussion of statistical significance is critical to rule out the possibility that any observed performance gains are merely due to chance. The analysis should account for potential confounding factors and clearly articulate any limitations of the benchmark comparisons. Overall, a convincing benchmark superiority analysis strengthens the paper’s argument for the practical significance and overall value of the proposed method.

Future Research#

The ‘Future Research’ section of a research paper on precision matrix estimation using meta-learning could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical analysis to handle non-sub-Gaussian distributions would enhance the model’s applicability to real-world scenarios with more complex data distributions. Improving computational efficiency is crucial, particularly for very high-dimensional datasets; exploring more advanced optimization techniques or specialized hardware acceleration could be beneficial. Investigating different meta-learning paradigms beyond MAML and exploring methods that explicitly model task relationships could further improve the model’s generalization capabilities. A further research direction would be to develop robust methods for handling missing data and to evaluate the performance of the approach in settings with varying levels of missingness. Finally, applying FasMe to a broader range of real-world applications, such as genomics, neuroscience, and finance, to evaluate its performance and demonstrate its practical impact in these domains would be important future work.

More visual insights#

More on figures

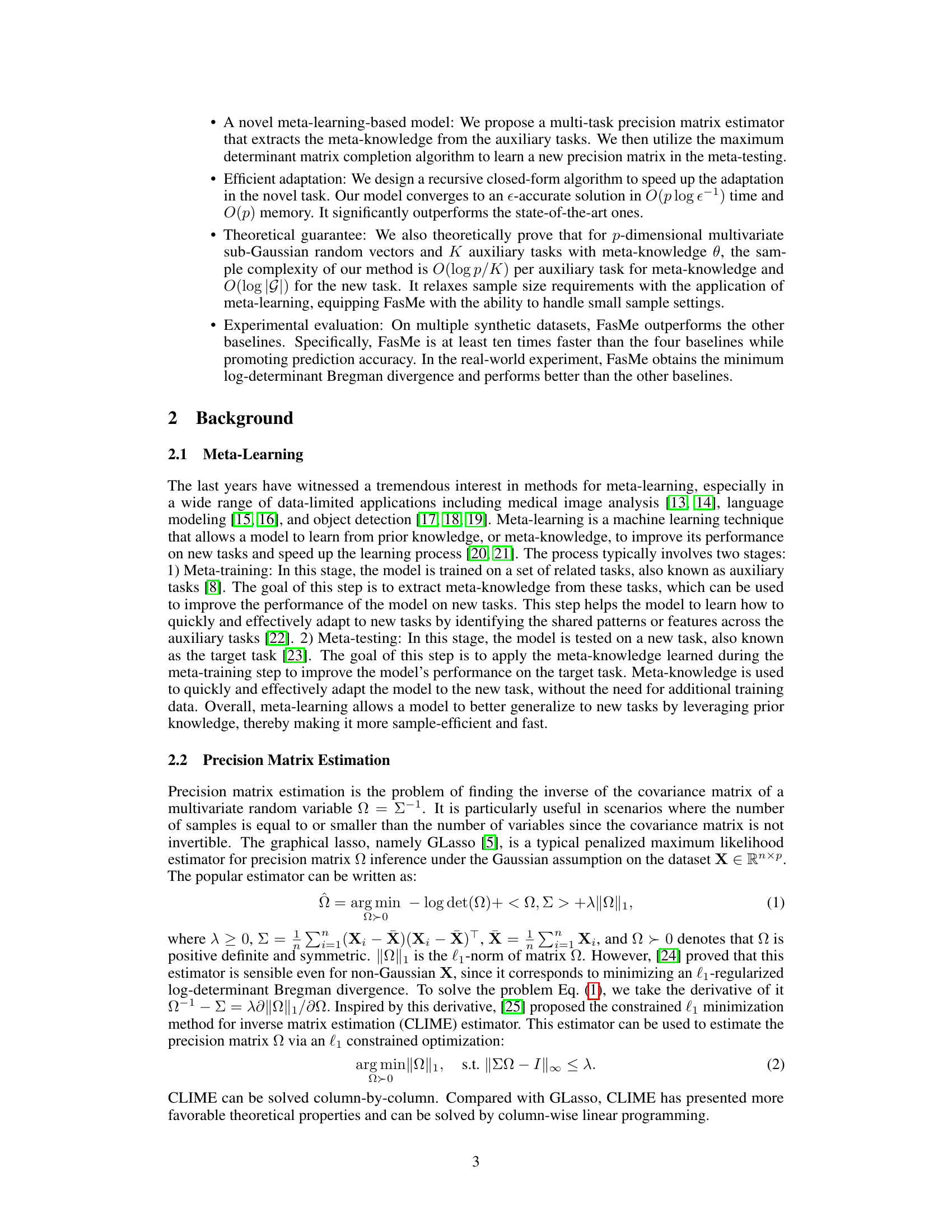

This figure illustrates the two-stage pipeline of the proposed meta-learning framework for precision matrix estimation. Stage 1 (Meta-knowledge Extraction) involves extracting shared structure (meta-knowledge) from auxiliary tasks using a meta-teacher. Stage 2 (Efficient Adaptation) uses this meta-knowledge and a small number of samples from the target task to efficiently estimate the precision matrix via matrix completion using a meta-student.

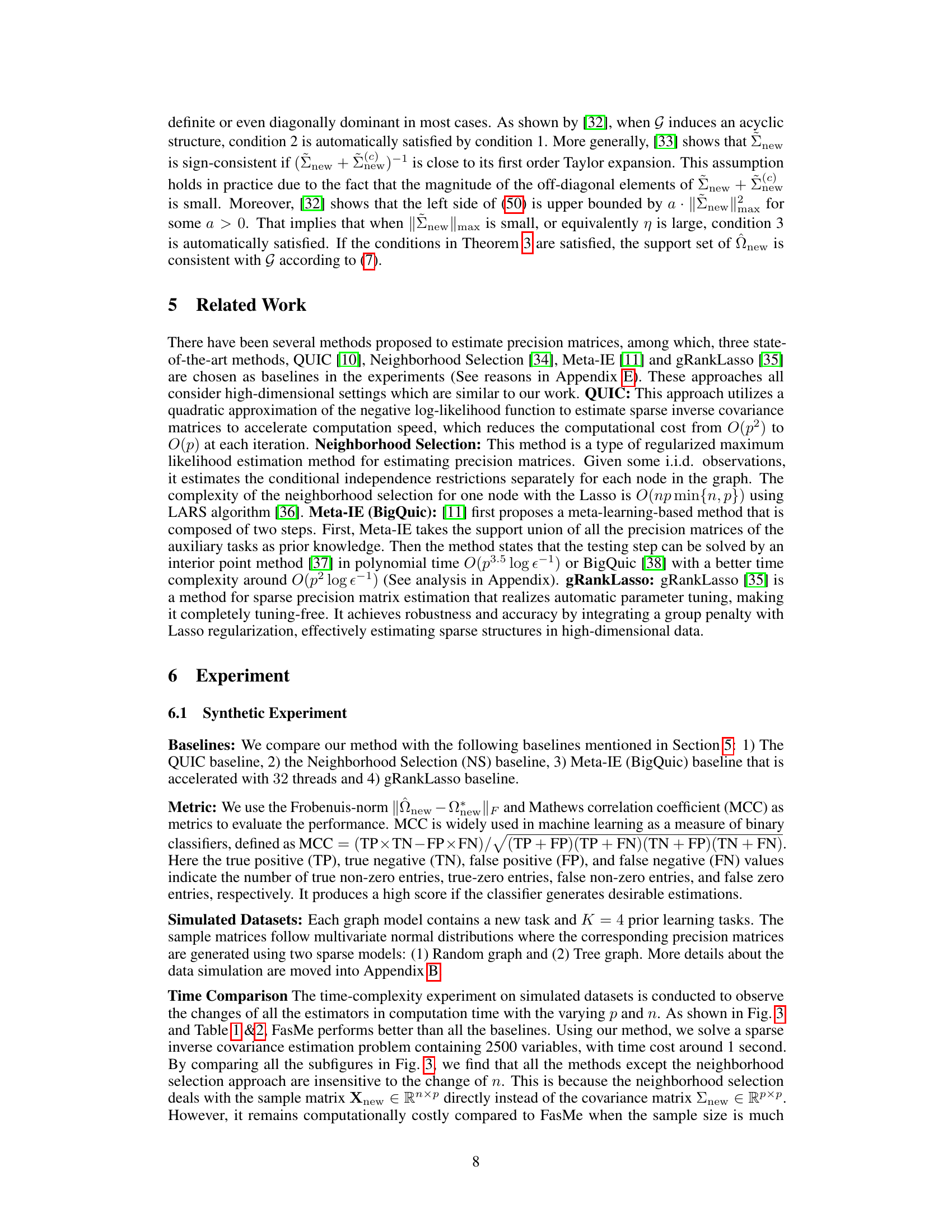

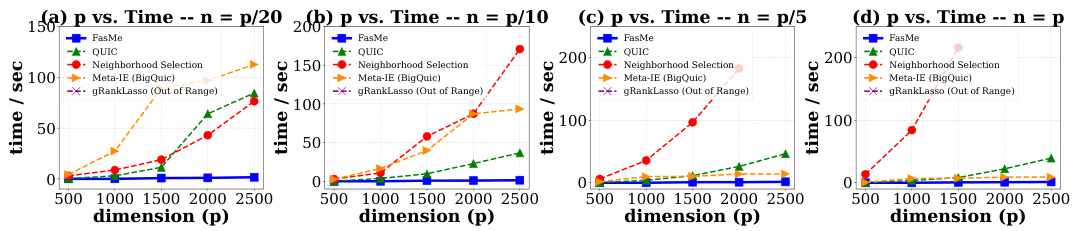

This figure compares the computation time of FasMe against four baseline methods (QUIC, Neighborhood Selection, Meta-IE, gRankLasso) across different problem sizes (p) and sample sizes (n). The results demonstrate FasMe’s significantly faster performance, especially for larger problem dimensions. The missing data points for the baselines indicate that their computation times exceeded the set limit.

This figure visualizes the performance of the proposed method and four baseline methods in recovering the graph structure from simulated and real-world datasets. Subfigures (a) and (b) compare the results on random and tree graph datasets, respectively. Subfigures (c) and (d) show the gene network (ChIP-Seq data) and brain connectome (fMRI data) recovered by the proposed method, along with the ground truth.

This figure shows a comparison of graph recovery results between the proposed method and other baselines on synthetic and real-world datasets. Subfigures (a) and (b) compare the ground truth graph structure with those recovered by various methods on two different types of synthetic graphs (random and tree). Subfigure (c) visualizes the gene network discovered by the proposed method using the ChIP-Seq dataset, illustrating gene interactions. Finally, subfigure (d) shows the brain connectome generated from fMRI data, depicting brain regions and their connections.

This figure presents a comparison of graph recovery results using different methods on synthetic datasets and real-world datasets (gene network and brain connectome). Subfigures (a) and (b) show comparisons on synthetic data generated from random graphs and tree graphs respectively. Subfigures (c) and (d) showcase the results obtained using the proposed method on real-world data, illustrating gene networks (ChIP-Seq) and brain connectomes (fMRI). Positive and negative correlations are visually represented using different colors.

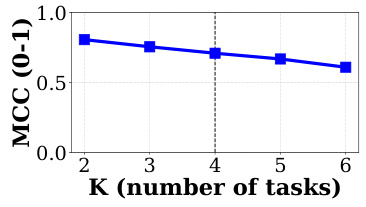

This figure shows the performance (measured by Matthews Correlation Coefficient or MCC) of the proposed method against different numbers of auxiliary tasks (K). The results suggest that the performance is relatively stable, showing a slight decrease as the number of tasks increases. This indicates that the model’s ability to learn from auxiliary tasks might plateau after a certain point.

More on tables

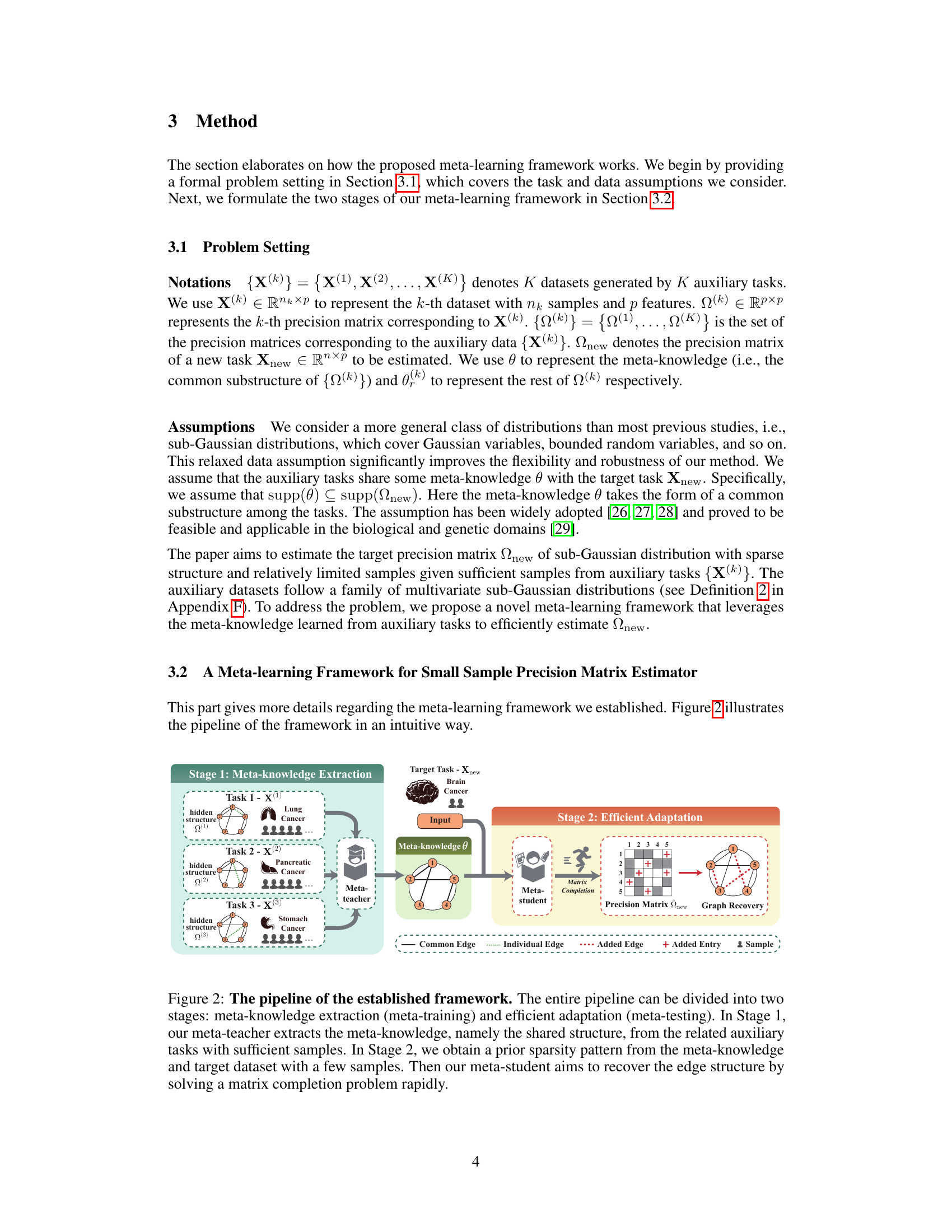

This table presents a comparison of the estimation error (measured by Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) and Frobenius norm) and running time of different methods for estimating precision matrices on synthetic datasets where the true precision matrix is generated from a random graph model. The results are shown for different sample sizes (n) and numbers of features (p). The asterisk (*) indicates that the running time exceeded 30 minutes.

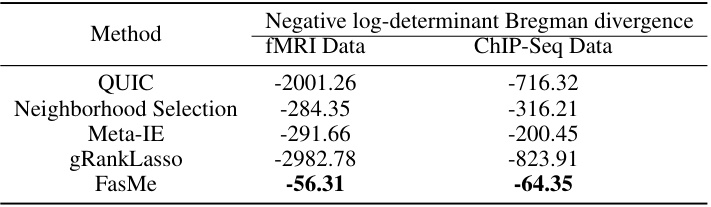

This table compares the performance of FasMe against other baseline methods on two real-world datasets: fMRI and ChIP-Seq. The metric used is the negative log-determinant Bregman divergence, where a larger value indicates better performance. The table shows that FasMe significantly outperforms the other methods on both datasets.

This table compares the standard Maximum Determinant Matrix Completion (MDMC) method with the improved MDMC method proposed in the paper. It highlights the differences in terms of the type of matrices they handle (partially observed matrices with chordality vs. partially observed matrices) and their time complexity (O(p²OINV) vs. O(plogε⁻¹)). The improved MDMC method offers significantly lower time complexity.

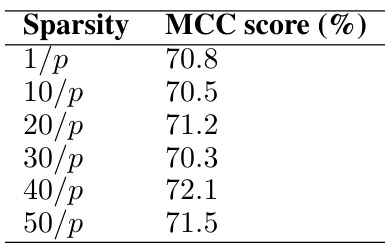

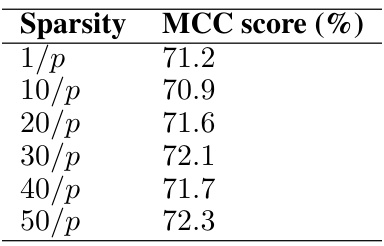

This table presents the MCC scores (%) achieved by the proposed FasMe model on a random graph with varying sparsity levels (1/p, 10/p, 20/p, 30/p, 40/p, 50/p), where n (sample size) = 100 and p (feature dimension) = 1000. The MCC (Matthews Correlation Coefficient) is a measure of the quality of a binary classification. Higher MCC scores indicate better performance of the model.

This table presents the MCC scores achieved by the FasMe model on a simulated dataset using a Tree graph structure with 100 samples and 1000 features. The MCC (Matthews Correlation Coefficient) is a measure of the quality of binary classification; higher values indicate better performance. The different rows represent different levels of sparsity in the generated graph (1/p, 10/p, 20/p, 30/p, 40/p, 50/p), where p is the number of features.

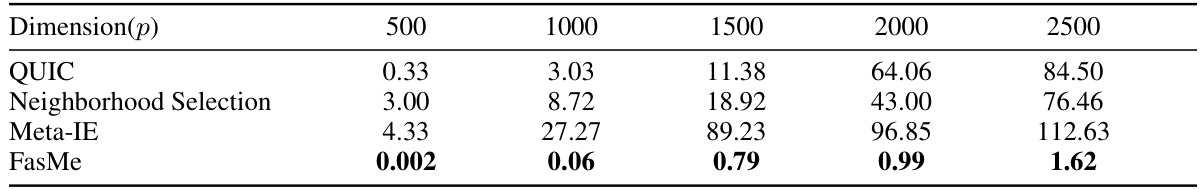

This table compares the computational time (in seconds) required by FasMe and four baseline methods (QUIC, Neighborhood Selection, Meta-IE, and gRankLasso) to estimate precision matrices on simulated datasets with varying feature dimensions (p) and a fixed sample size (n = p/20). The results show that FasMe is significantly faster than all the baseline methods, particularly as the dimension p increases.

This table presents a comparison of the computational time (in seconds) required by FasMe and four baseline methods (QUIC, Neighborhood Selection, Meta-IE, and gRankLasso) for estimating precision matrices on simulated datasets. The comparison is made across different feature dimensions (p), keeping the sample size (n) constant at one-tenth of the feature dimension (n = p/10). The results highlight the significant speed advantage of FasMe over the other methods, especially as the dimensionality (p) increases.

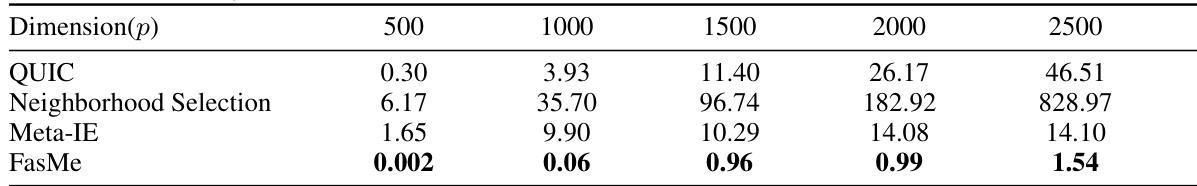

This table compares the computation time (in seconds) required by FasMe and four baseline methods (QUIC, Neighborhood Selection, Meta-IE, and gRankLasso) for estimating precision matrices on simulated datasets. The feature dimension (p) varies from 500 to 2500, and the sample size (n) is set to p/5. FasMe demonstrates significantly faster computation times compared to the baselines.

This table compares the computation time (in seconds) of FasMe against four baseline methods (QUIC, Neighborhood Selection, Meta-IE, and gRankLasso) across five different feature dimensions (p = 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, 2500). The sample size (n) is set to be equal to the feature dimension (n=p) for each experiment. The table shows that FasMe is significantly faster than all baseline methods, especially as the dimensionality increases.

Full paper#