↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Deep learning models often lack transparency, making it hard to understand and trust their decisions. Concept-Based Models (CBMs) try to solve this by incorporating human-interpretable concepts but often fall short because their task predictors remain black boxes. This lack of complete interpretability raises concerns about reliability and prevents formal verification.

To address these challenges, the researchers introduce Concept-Based Memory Reasoning (CMR). CMR models task prediction as a neural selection mechanism over a memory of learnable logic rules, followed by a symbolic evaluation. This approach provides both accuracy and interpretability. CMR demonstrates better accuracy and interpretability trade-offs, discovers logic rules aligned with ground truth, and enables interventions to modify rules and verify properties before deployment, significantly advancing the explainable AI field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the critical need for transparency and verifiability in AI decision-making processes. Concept-Based Memory Reasoning (CMR) offers a novel approach to building explainable AI models, providing significant advancements for both researchers and practitioners in the field. It opens new avenues for research into verifiable AI and enhances the reliability of AI systems, particularly in high-stakes applications. This is directly relevant to the current trend of emphasizing explainability and trustworthiness in AI, which will likely become even more critical in the future. CMR’s unique approach and strong results establish it as a significant contribution to the field.

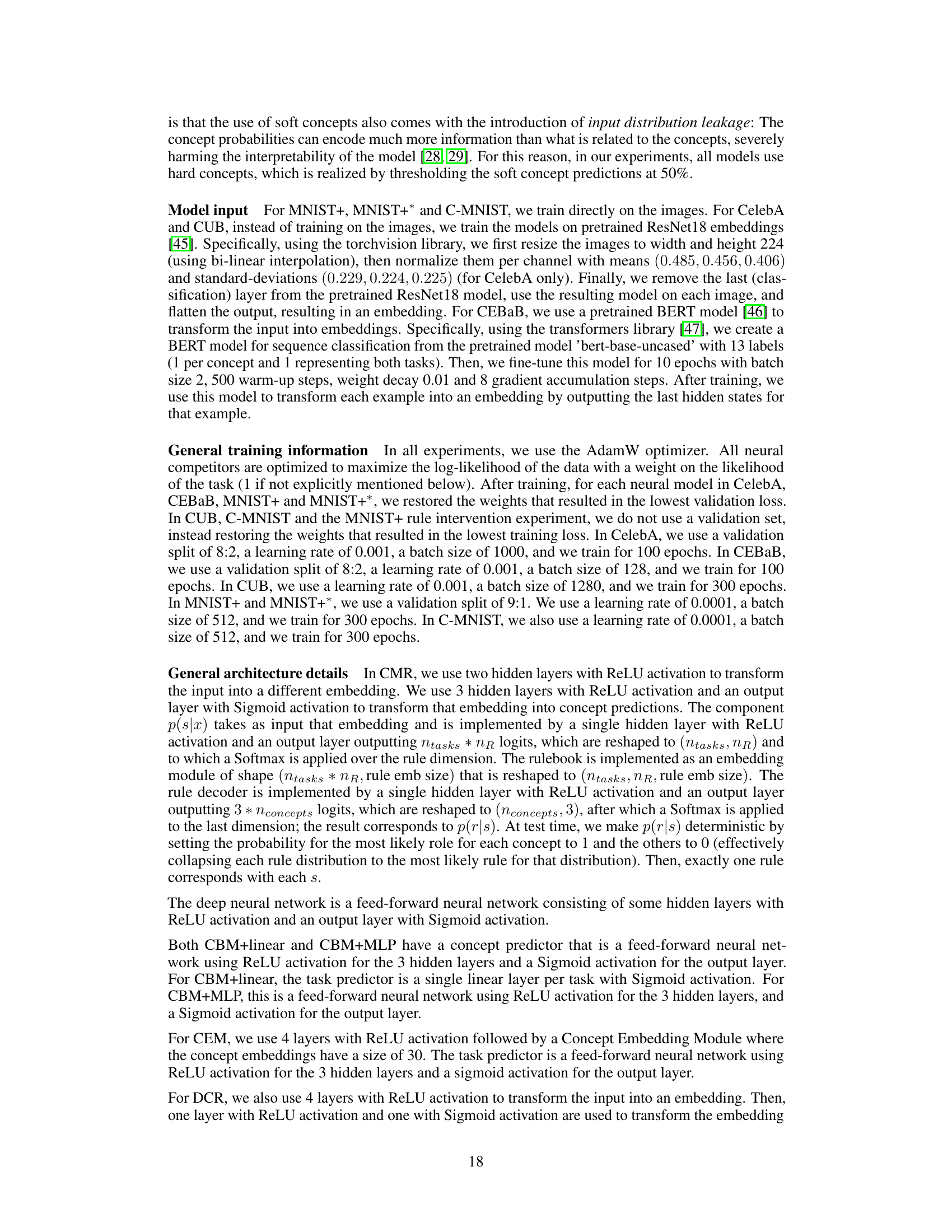

Visual Insights#

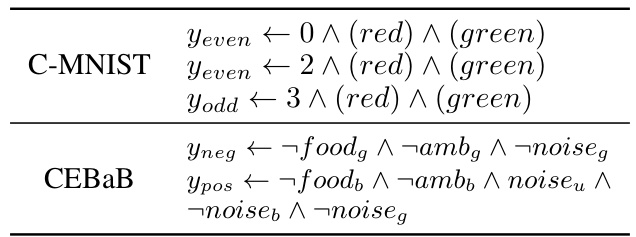

The figure shows the probabilistic graphical model used in CMR. There are four nodes representing four variables: The input data (x), the concept encoding (c), the selected rule (r), and the task prediction (y). Arrows indicate the probabilistic dependencies between the variables. The input x influences both the concept encoding c and the rule selection r. The concept encoding c and the selected rule r together determine the task prediction y. The model shows how the concepts and the selected rule combine to produce a final prediction.

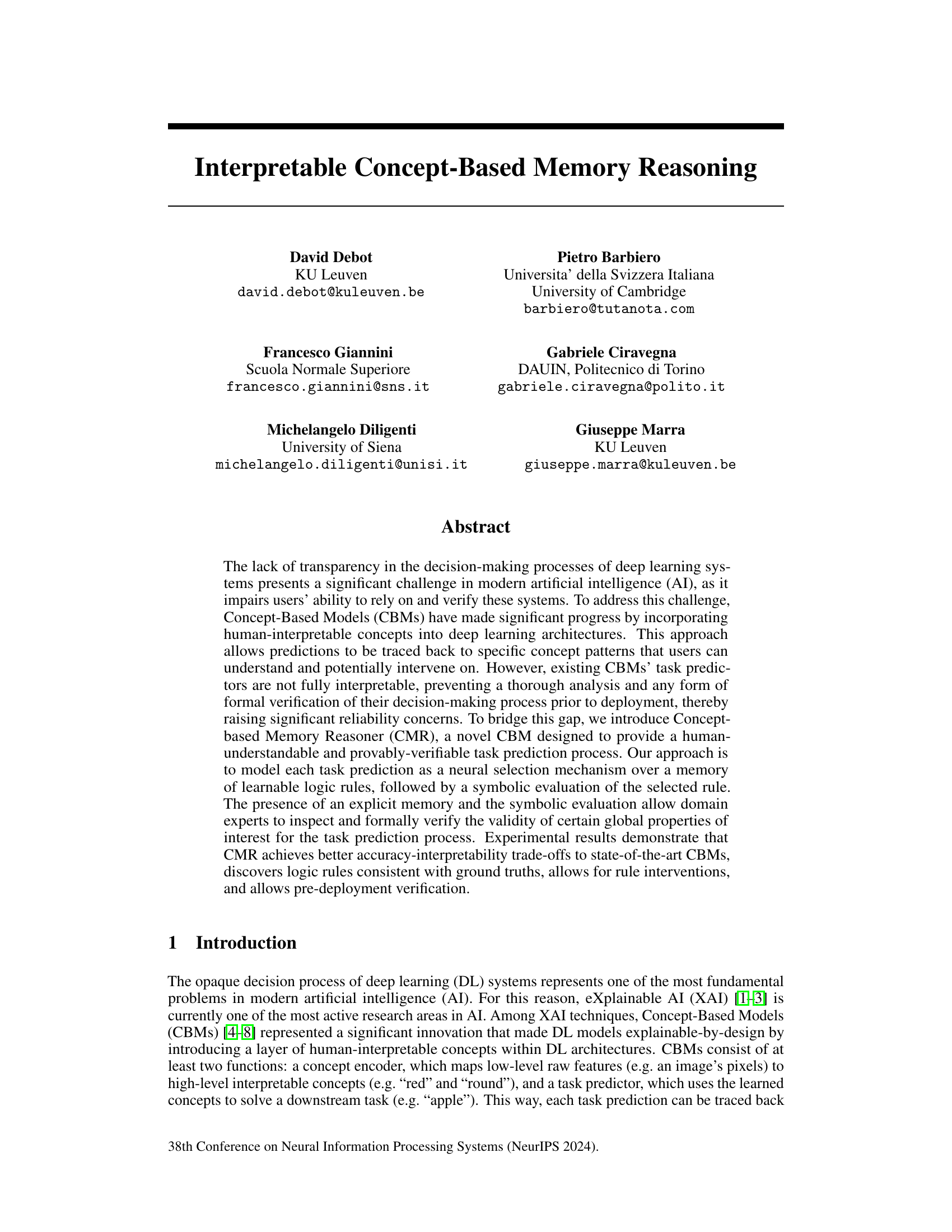

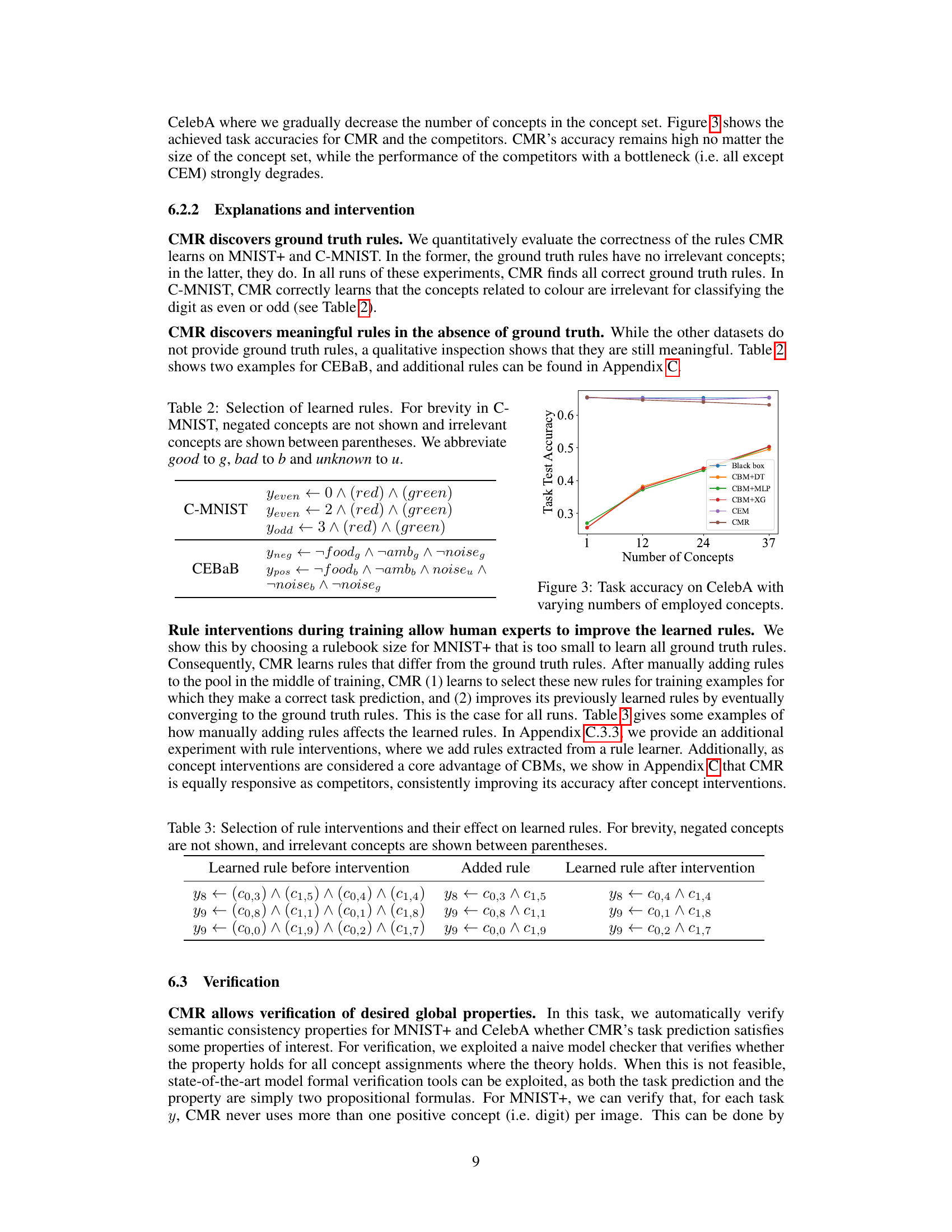

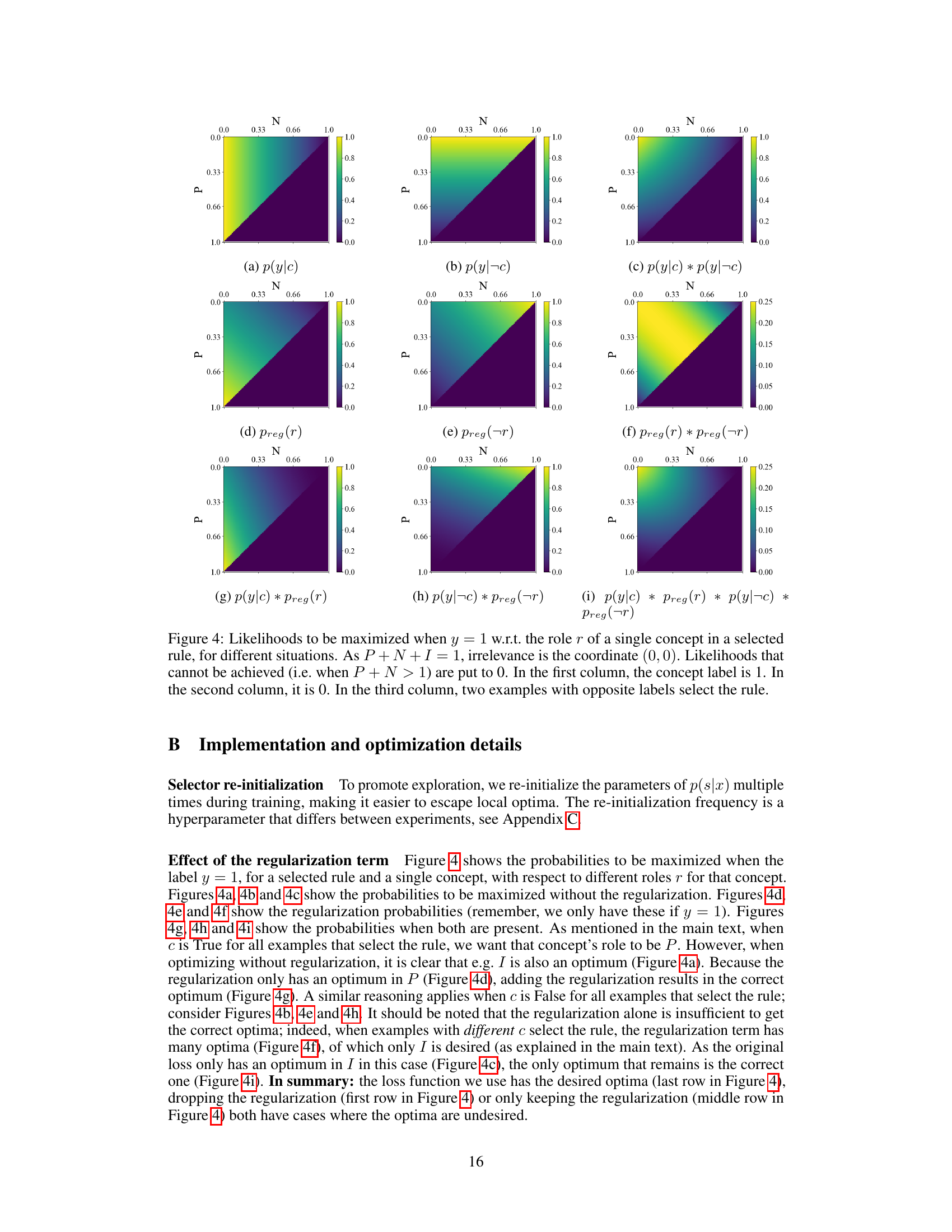

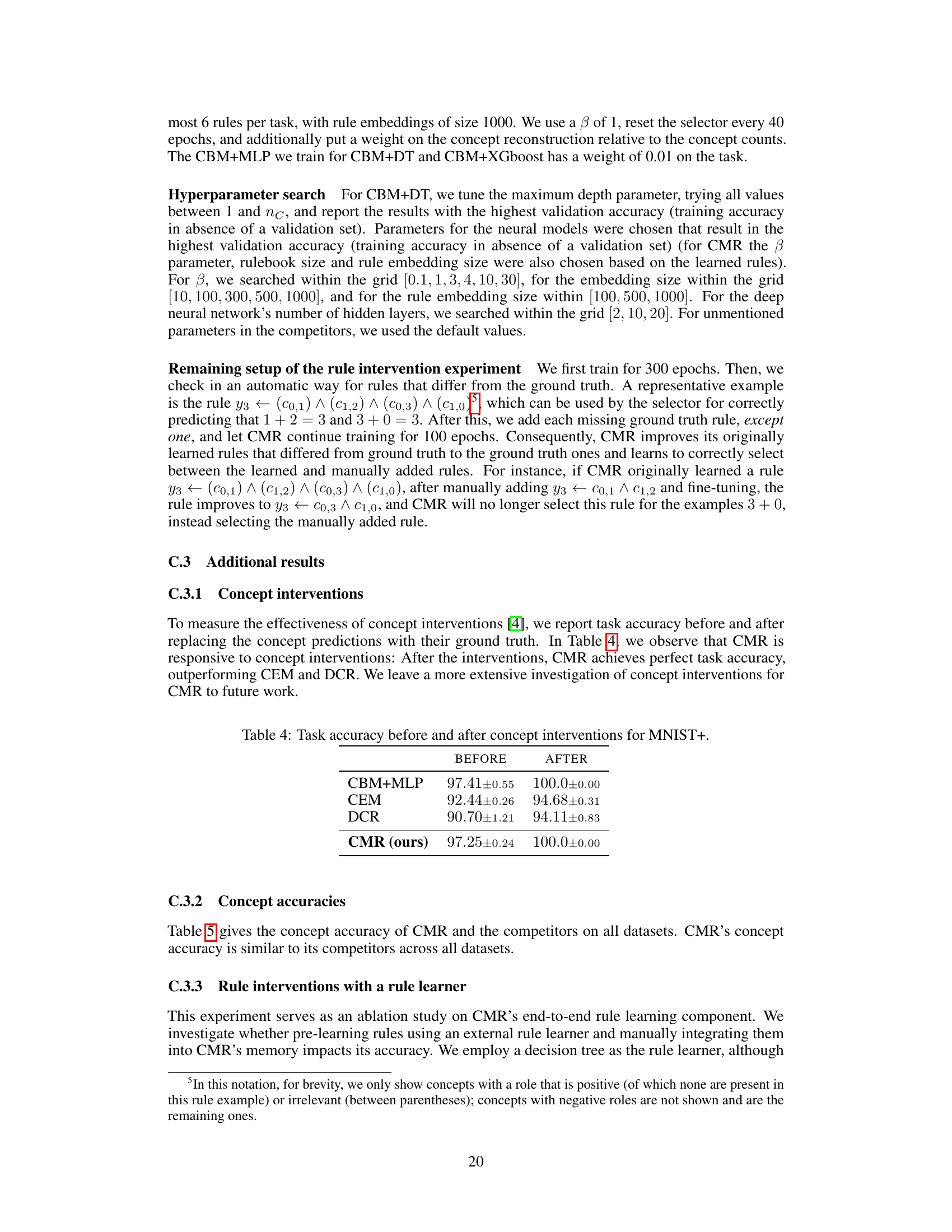

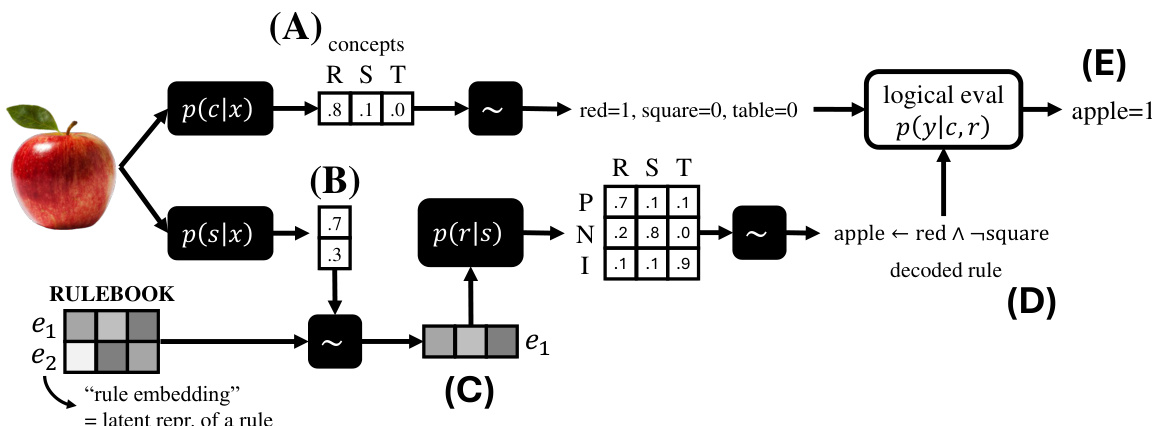

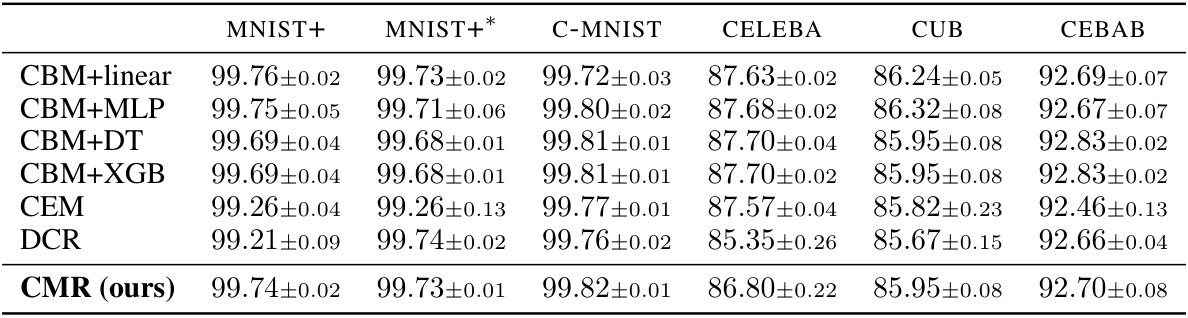

This table presents the task accuracy results achieved by different models on various datasets. The models include several Concept-Based Models (CBMs) with varying task predictors (linear, MLP, decision tree, XGBoost), along with two state-of-the-art CBMs (CEM and DCR). A ‘black box’ model (a non-interpretable model) is included as a baseline for comparison. The table shows the mean accuracy and standard deviation across three runs for each model and dataset. The best and second-best performing CBMs for each dataset are highlighted in bold.

In-depth insights#

CMR: A Novel CBM#

The heading “CMR: A Novel CBM” suggests a research paper introducing a new Concept-Based Model (CBM) called CMR. CMR likely improves upon existing CBMs by addressing their limitations, such as a lack of global interpretability or limited ability to handle complex tasks. The “novelty” implies that CMR incorporates a unique architecture or methodology. This likely involves improvements in how human-interpretable concepts are integrated within a deep learning framework, potentially leading to better accuracy-interpretability trade-offs and enabling more thorough analysis of the model’s decision-making process. The focus on both accuracy and interpretability highlights a central challenge in Explainable AI (XAI): balancing performance with understandability. A key aspect of the innovation might be CMR’s ability to provide provably verifiable predictions, which is a significant advance in trust and reliability for AI systems. The success of CMR would depend on its ability to achieve improved accuracy while maintaining the crucial element of human-interpretable explanations, representing a substantial contribution to the field of XAI.

NIR Paradigm#

The Neural Interpretable Reasoning (NIR) paradigm, as introduced in the research paper, represents a significant advancement in explainable AI. It addresses the limitations of existing Concept-Based Models (CBMs) by focusing on global interpretability and provability. NIR achieves this through a novel architecture that involves neurally generating an interpretable model (a logical rule) and then symbolically executing it. This two-step process offers a compelling blend of accuracy and explainability, enabling human experts to understand and potentially verify the decision-making process of AI systems. The use of a differentiable memory of learnable logic rules provides human-understandable decision-making processes. Moreover, the capacity for pre-deployment verification is a crucial aspect of NIR, ensuring reliable and trustworthy AI systems. The paradigm also highlights the potential for human interventions, allowing for rule interventions and concept interventions, thus promoting more controlled and responsible AI development. Overall, NIR stands out as a powerful framework for developing high-performing and interpretable AI systems.

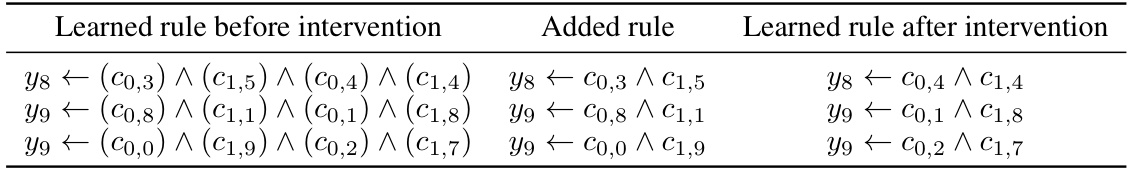

Rule Interventions#

The concept of ‘Rule Interventions’ presents a powerful paradigm shift in enhancing the explainability and controllability of machine learning models. Unlike traditional concept-based models that only allow interventions at the prediction level, rule interventions enable direct manipulation of the learned decision-making logic itself. This offers significant advantages for domain experts, empowering them to inspect, modify, and potentially verify individual rules before deployment. This level of control opens exciting possibilities for debugging, improving performance and ensuring alignment with predefined constraints, or even injecting domain knowledge directly into the model. The capacity to modify or add rules in response to observed biases or limitations greatly enhances the system’s trustworthiness and adaptability. However, careful design is crucial to ensure that rule interventions do not unintentionally introduce vulnerabilities or unexpected behavior. Therefore, developing robust mechanisms for managing and verifying the updated rule set, whilst maintaining model performance, represents a key challenge for future research.

Global Interpretability#

Global interpretability, in the context of machine learning models, signifies the ability to understand a model’s behavior not just for individual inputs but across the entire input space. Unlike local interpretability, which focuses on explaining individual predictions, global interpretability aims for a holistic understanding of the model’s decision-making logic. This is crucial for building trust and ensuring the reliability of AI systems, especially in high-stakes applications. Achieving global interpretability often involves developing models with inherently transparent architectures, such as those based on symbolic reasoning or rule-based systems. The challenge lies in balancing this global understanding with the model’s predictive accuracy. Approaches such as those described in the paper strive to create models with both high predictive power and comprehensive, human-understandable explanations of their decision-making processes. This is an active area of research, and further advancements will be necessary to develop more robust and reliable globally interpretable models for a wider range of applications.

Future Works#

The research paper’s ‘Future Works’ section would ideally delve into several crucial areas. Extending CMR’s capabilities to handle negative reasoning would enhance the model’s explanatory power, going beyond explanations for positive predictions alone. Exploring alternative rule selection mechanisms beyond the current attention mechanism could improve efficiency and accuracy. Given the emphasis on interpretability, a thorough investigation of CMR’s robustness to adversarial attacks and noisy data is vital. The study should also analyze the scalability of CMR to massive datasets and more complex tasks. Finally, a comprehensive comparative analysis with other prototype-based models and neurosymbolic approaches needs to be done, highlighting the unique benefits and limitations of CMR. This multifaceted approach would establish CMR as a more robust and comprehensive concept-based memory reasoning system.

More visual insights#

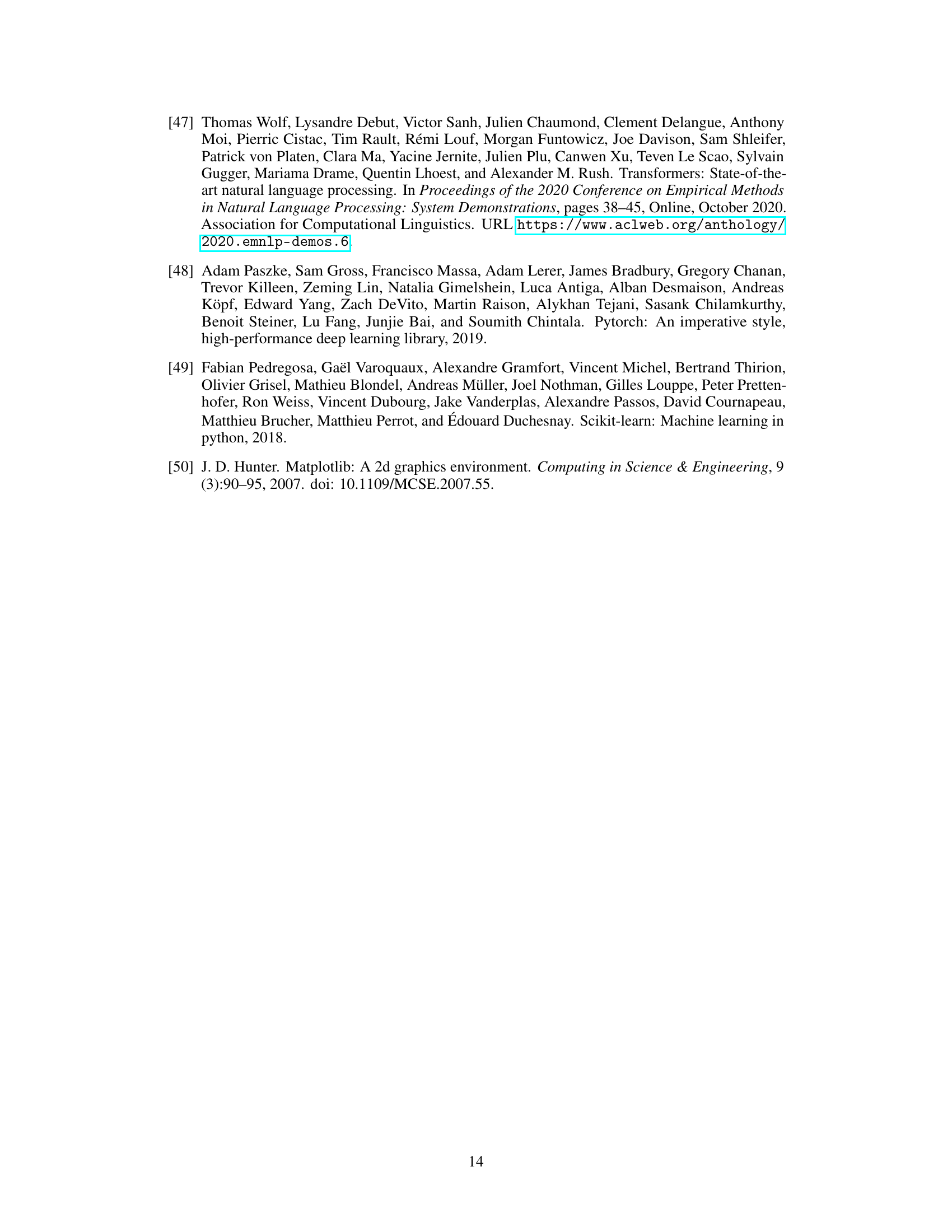

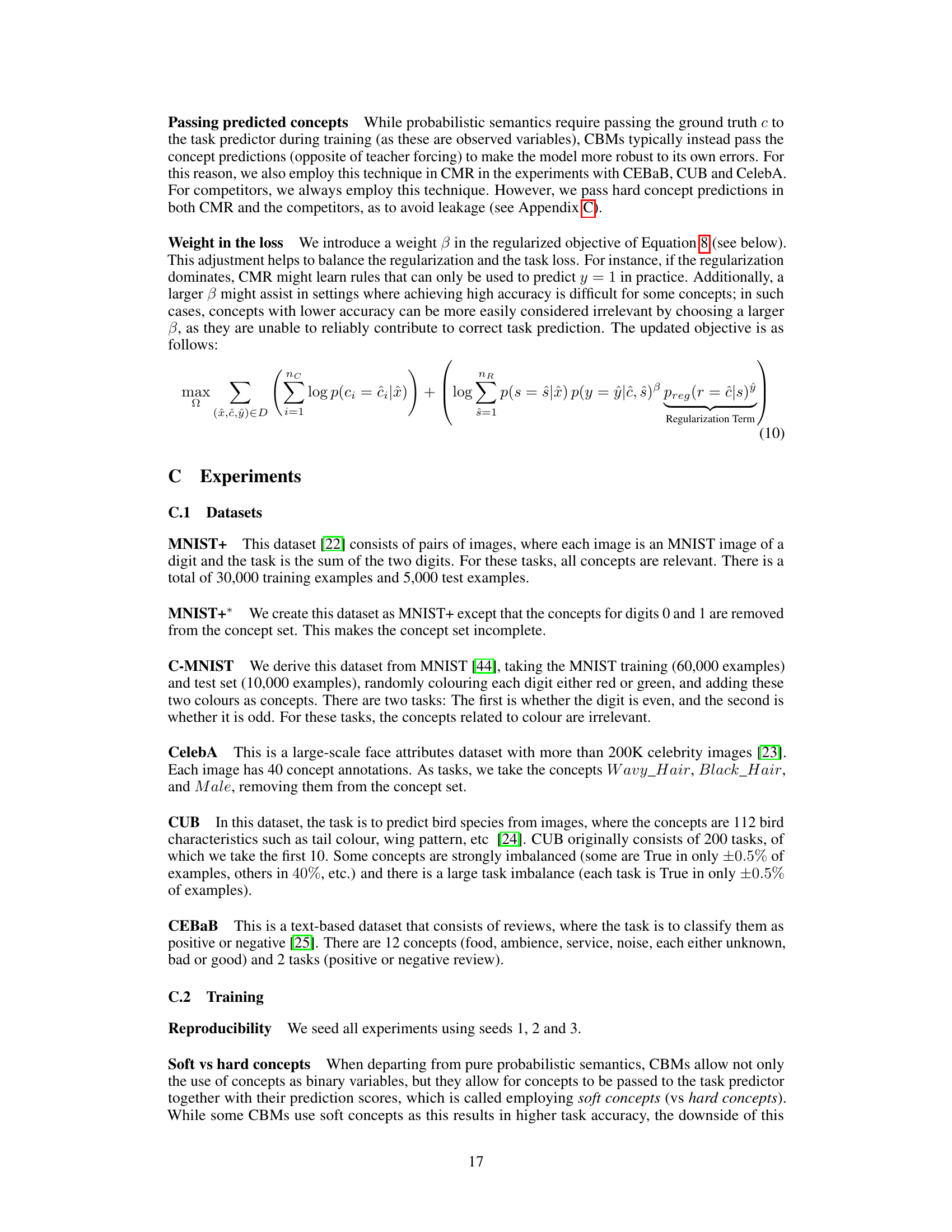

More on figures

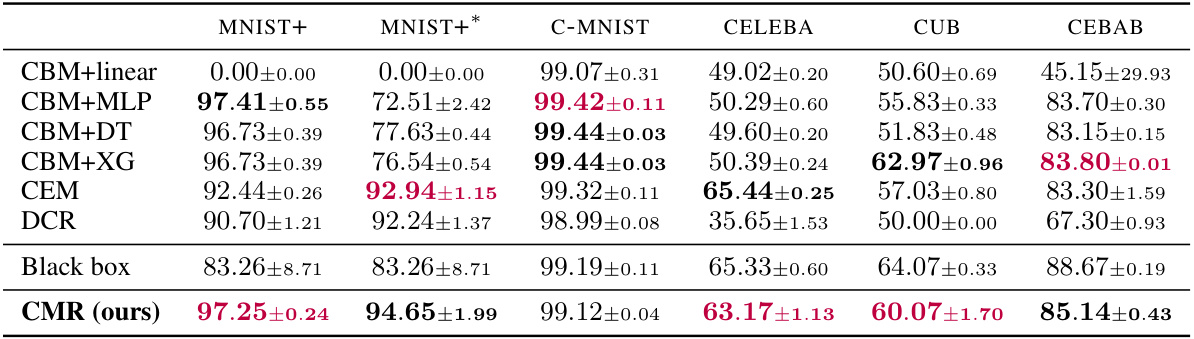

This figure illustrates the process of making a prediction using the Concept-based Memory Reasoner (CMR) model. The image is input (A) and converted into concept predictions. These predictions are then used by the rule selector (B) to determine a probability distribution over the rules in the rulebook. A rule embedding is then selected (C) based on this distribution, decoded (D) to obtain a logical rule, and finally the task prediction is made (E) using the concept predictions and the decoded rule. The black boxes in the figure represent neural network components, and the white box indicates a symbolic logic operation.

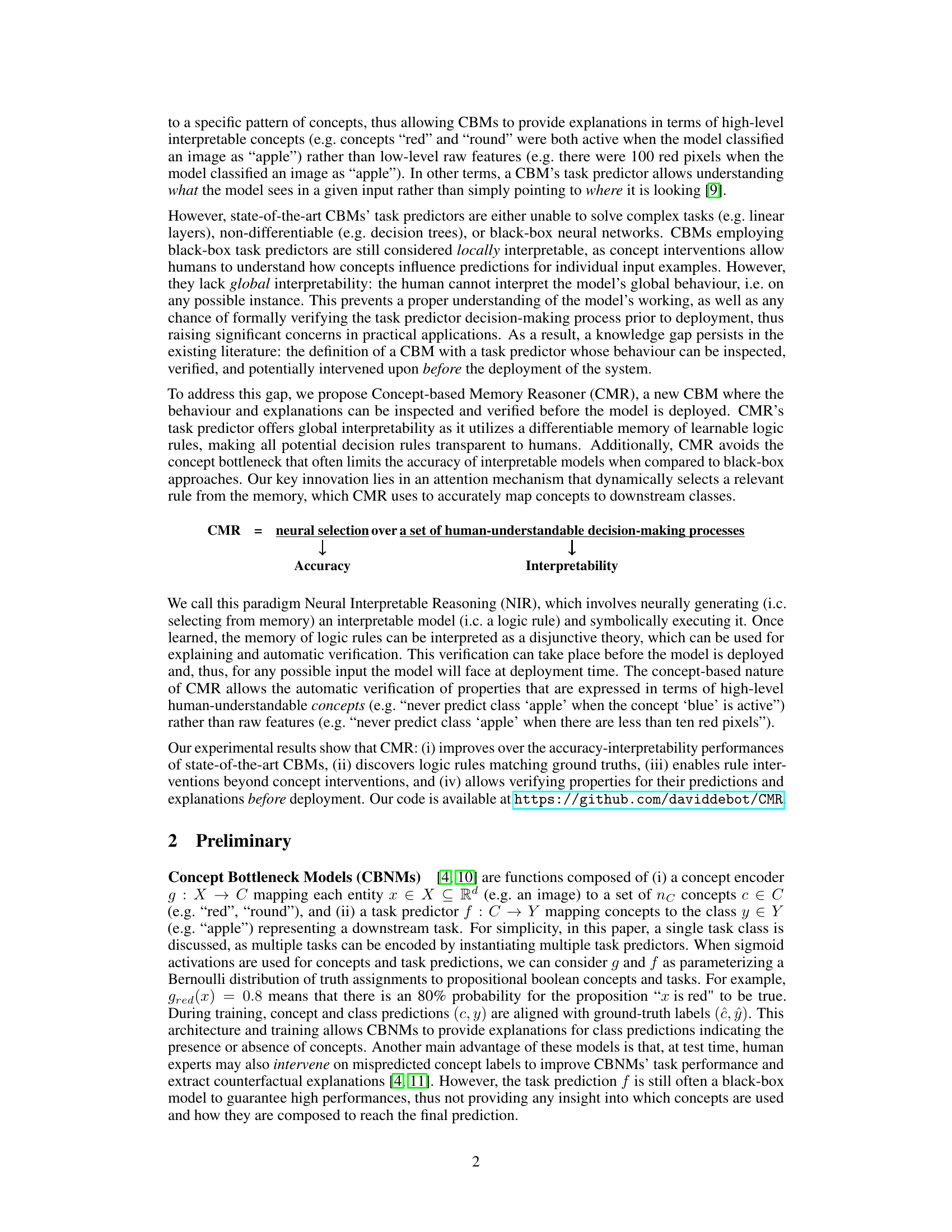

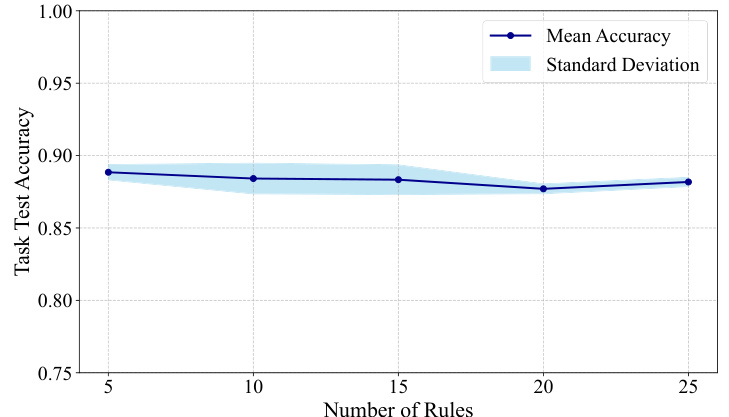

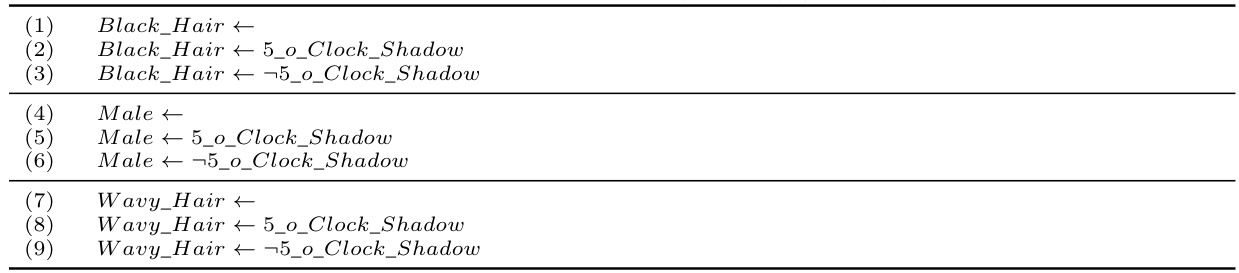

This figure shows the task accuracy on the CelebA dataset when varying the number of concepts used. It compares the performance of CMR against other concept-based models (CBM+DT, CBM+MLP, CBM+XG, CEM) and a black-box model. The results demonstrate that CMR maintains high accuracy even with a reduced number of concepts, while the accuracy of other concept-based models significantly degrades due to the concept bottleneck.

This figure illustrates the process of CMR’s task prediction using an example with two rules and three concepts. It visually breaks down the process into five steps, each represented by a block. The image is input, and each neural network block (black) performs a transformation, culminating in the final symbolic (white) evaluation block determining the prediction (apple). It highlights the selection of a logical rule from the rulebook and its subsequent symbolic evaluation on concept predictions.

This figure illustrates the prediction process of the Concept-based Memory Reasoner (CMR) model. It shows how an input image is processed through the three main components: concept encoder, rule selector, and task predictor. The concept encoder maps the image to concept predictions (e.g., ‘red’, ‘square’, ’table’). The rule selector probabilistically selects a rule from the rulebook (memory of logic rules). This selected rule is then symbolically evaluated based on the concept predictions to produce a final prediction (e.g., ‘apple = 1’). The figure highlights the interplay between neural (black boxes) and symbolic (white box) components in CMR’s reasoning process.

This figure illustrates the prediction process of the Concept-Based Memory Reasoner (CMR) model. It shows how an input image is processed through different components of the CMR model: concept encoder, rule selector, and task predictor. The concept encoder maps the image to concept predictions. The rule selector probabilistically selects a rule from a rulebook. The rule embedding is decoded into a logical rule, and this rule is symbolically evaluated on the concept predictions to give the final task prediction.

This figure illustrates the process of CMR’s prediction. It shows how an input image is first processed by a concept encoder to obtain concept predictions. Then, a rule selector chooses a rule from a learned rulebook. This selected rule is symbolically evaluated using the concept predictions to generate a final task prediction (e.g., classifying an image as an apple). The figure uses a simplified example with two rules and three concepts for clarity.

This figure shows an example prediction process of the Concept-based Memory Reasoning (CMR) model. It illustrates the model’s three main components: a concept encoder, a rule selector, and a task predictor. The process begins with an image (an apple in this example) that is fed into the concept encoder (A). The encoder outputs a probability distribution over concepts representing the image’s features (e.g., ‘red’, ‘square’, ’table’). The rule selector (B) takes the image as input and selects a rule from the rulebook, which is a set of human-understandable logical rules. A probability distribution over the possible rules is shown. Based on the probability distribution over rules, a rule embedding is chosen from the rulebook (C). This rule embedding is then decoded (D) to provide a logical rule such as ‘apple is red and not square’. The task predictor (E) then applies this logical rule to the concept probabilities to arrive at a final prediction for the image (apple=1). The diagram visually separates the neural network components (black boxes) from the symbolic logic evaluation (white box).

This figure shows an example prediction process of the Concept-based Memory Reasoner (CMR) model. The process is broken down into five steps, each represented by a block in the figure. It illustrates how CMR uses a concept encoder, rule selector, and task predictor to make a prediction, highlighting the interplay between neural networks (black boxes) and symbolic logic evaluation (white box). The figure helps visualize how an input image is converted to a concept prediction, then how a rule is selected and evaluated, resulting in the final classification prediction (apple, in this case).

More on tables

This table presents the task accuracy results achieved by various models on six different datasets. The models are compared to assess their performance on tasks ranging in complexity and concept set completeness. CBMs (Concept-Based Models) are compared against standard black-box models, and the best-performing CBMs are highlighted.

This table presents the task accuracy results for various models on several datasets. The models include different Concept-Based Models (CBMs) using various task predictors (linear, MLP, decision tree, XGBoost), two state-of-the-art CBMs (CEM and DCR), and a black-box model as a baseline. Datasets encompass various complexities and concept set qualities (complete or incomplete). The best and second-best performing CBMs are highlighted for each dataset.

This table presents the task accuracy results for different models on several datasets. The models include various Concept-Based Models (CBMs) using different task predictors (linear, MLP, decision tree, XGBoost), state-of-the-art CBMs (CEM and DCR), and a standard black-box model for comparison. The datasets used are MNIST+, MNIST+*, C-MNIST, CelebA, CUB, and CEBaB, each representing different levels of complexity and concept set completeness. The best and second-best performing CBMs for each dataset are highlighted in bold.

This table presents the task accuracy results achieved by various models on several datasets. The models include different Concept-Based Models (CBMs) using various task predictors (linear, MLP, decision tree, XGBoost), along with state-of-the-art CBMs (CEM and DCR), and a black-box model for comparison. The datasets vary in complexity and concept set completeness (complete vs. incomplete). The best and second-best performances among the CBMs are highlighted in bold.

This table presents the task accuracy results on six different datasets for various models, including different Concept-Based Models (CBMs) and a black-box model. The table compares the performance of CMR (the proposed model) against state-of-the-art CBMs (CBM+linear, CBM+MLP, CBM+DT, CBM+XG, CEM, DCR) and a standard black-box neural network. The datasets vary in complexity and concept set completeness. The best and second-best performing CBMs are highlighted in bold for comparison.

This table presents the task accuracy results for various models on multiple datasets. The models include different Concept-Based Models (CBMs) using various task predictors (linear, MLP, decision tree, XGBoost), state-of-the-art CBMs (CEM and DCR), and a black-box model as a baseline. The datasets represent varying levels of complexity and concept set completeness. The best and second-best performing CBMs are highlighted for each dataset.

This table presents the task accuracy results achieved by different models on six datasets. The models include various Concept-Based Models (CBMs) using different task predictors (linear, MLP, decision tree, XGBoost), two state-of-the-art CBMs (CEM and DCR), and a black-box model for comparison. The datasets represent different tasks and complexities, including complete and incomplete concept sets. The best and second-best performances among the CBMs are highlighted in bold to show the relative performance of the proposed model (CMR) against existing methods.

This table presents the task accuracy results achieved by various models on several datasets. The models include different Concept-Based Models (CBMs) using various task predictors (linear, MLP, decision tree, XGBoost), along with state-of-the-art CBMs like CEM and DCR. A black-box model is included for comparison. The datasets are diverse, representing different task complexities and concept set completeness. The best and second-best performing CBMs are highlighted for each dataset.

This table presents the task accuracy results achieved by different models on various datasets. The models include Concept-Based Models (CBMs) with different task predictors (linear, MLP, decision tree, XGBoost), state-of-the-art CBMs (CEM and DCR), and a black-box model for comparison. The datasets represent diverse tasks and complexities. The best and second-best performing CBMs are highlighted for each dataset, showcasing the relative performance of CMR (the proposed model) compared to existing methods.

This table presents the task accuracy achieved by various models on several datasets. The models include different Concept-Based Models (CBMs) using various types of task predictors (linear, MLP, decision tree, XGBoost), as well as a state-of-the-art CBM (CEM), a Deep Concept Reasoner (DCR), and a black-box model for comparison. The datasets encompass different complexity levels and concept set completeness. The best and second-best performances among CBMs are highlighted for each dataset. The table serves to compare the accuracy of CMR against existing approaches on various tasks.

Full paper#