↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are known for their ability to store and retrieve facts. However, this paper reveals a crucial limitation: fact retrieval in LLMs is not robust and can be easily manipulated by changing the context, even without altering the factual meaning. This phenomenon, termed ‘context hijacking’, suggests that LLMs might function more like associative memory models, relying on context clues rather than semantic understanding. This raises important questions about the robustness and reliability of LLMs for various applications.

To investigate this behavior, the authors introduce a new task called ’latent concept association’ and study it using a simplified one-layer transformer model. They demonstrate theoretically and empirically that transformers effectively perform memory retrieval by combining self-attention (for information aggregation) and the value matrix (as associative memory). This work provides insights into the mechanisms underlying fact retrieval in LLMs and offers valuable new theoretical tools for investigating low-rank structure in embedding spaces.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it reveals the fragility of fact retrieval in LLMs, a critical issue for their reliable use. The findings challenge the common assumption that LLMs possess robust memory, paving the way for designing more robust and trustworthy models. Furthermore, the introduction of a new theoretical framework for understanding LLMs as associative memory models opens exciting avenues for future research and model improvements.

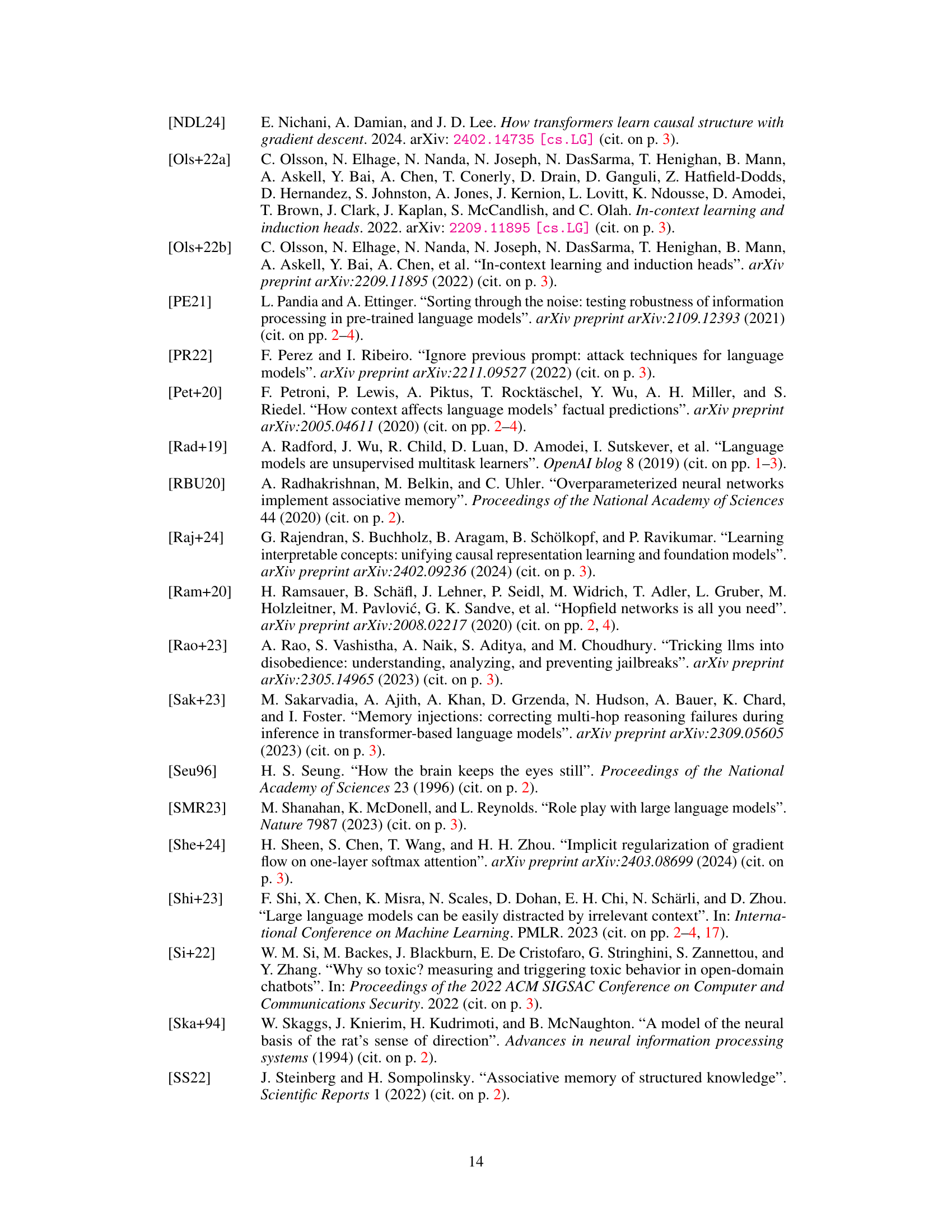

Visual Insights#

This figure displays four examples of how the outputs of various LLMs (GPT-2, Gemma-2B, Gemma-2B-IT, LLaMA-7B) can be manipulated by changing the context, even without altering the factual meaning. The first example shows that all models correctly answer ‘Paris’ when asked where the Eiffel Tower is. However, by adding sentences like ‘The Eiffel Tower is not in Chicago’, the models incorrectly answer ‘Chicago’ in the following examples. This demonstrates the vulnerability of LLMs to context manipulation, highlighting the non-robustness of their fact retrieval abilities.

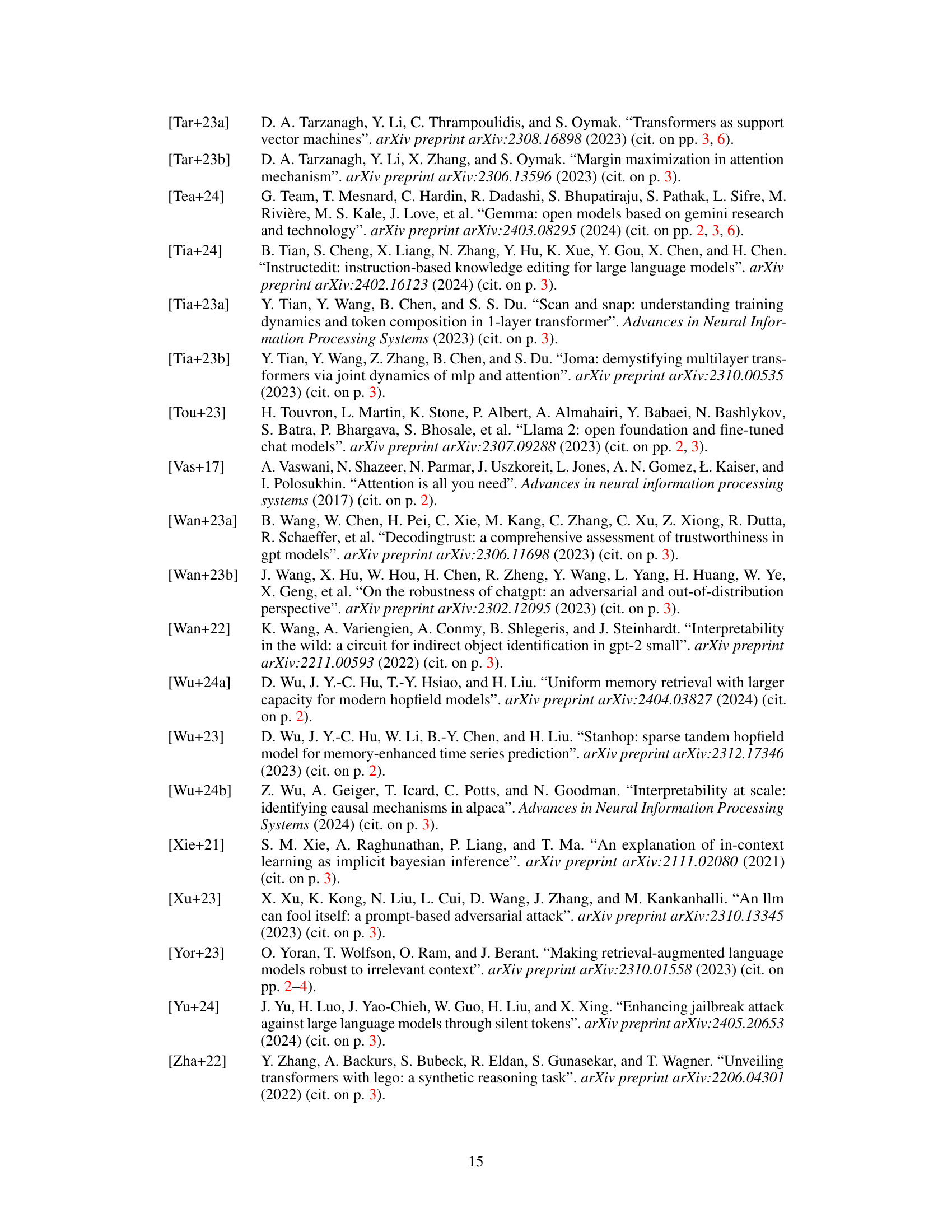

This table lists four examples of contexts from the COUNTERFACT dataset, each associated with a different relation ID. For each example, the table provides the context, the true target token, and a false target token that could be used to mislead a language model.

In-depth insights#

LLM Robustness#

The robustness of Large Language Models (LLMs) is a critical area of research. LLMs are susceptible to context hijacking, where seemingly minor changes in input phrasing can drastically alter the model’s output, even if the factual meaning remains the same. This vulnerability highlights the associative nature of LLM memory, which relies on token relationships rather than semantic understanding. The paper investigates this issue by introducing a synthetic memory retrieval task, exploring how transformers, the building blocks of LLMs, handle this task. This helps shed light on how information is gathered through self-attention and recalled via the value matrix. Furthermore, the research reveals that the embedding space in trained transformers exhibits low-rank structure, which has implications for existing editing and fine-tuning techniques. Ultimately, understanding and improving LLM robustness requires a deeper exploration of their latent semantic representation, moving beyond direct token-based analysis towards a more nuanced understanding of the concepts and relationships LLMs internalize.

Concept Association#

The concept of ‘Concept Association’ in the context of LLMs is a crucial one, highlighting the model’s ability to connect and retrieve information based on relationships between concepts rather than direct memorization. This associative memory model contrasts with the ideal of semantic understanding, where LLMs should reason and integrate prior knowledge. The paper investigates how this associative process works in transformers by creating a synthetic task called ’latent concept association’. This task focuses on relationships within a latent semantic space, allowing for more nuanced exploration of how LLMs use associative memory. The authors use a one-layer transformer as a model to understand this process, showcasing the role of self-attention for gathering information and the value matrix as the associative memory component. This provides crucial theoretical and empirical insights into the mechanisms of memory retrieval within LLMs and contributes to the development of more robust models.

Transformer Memory#

The concept of “Transformer Memory” is intriguing, as it probes the mechanisms by which transformer networks, the architecture underlying large language models (LLMs), store and retrieve information. It moves beyond the simple view of LLMs as purely statistical prediction machines and delves into their capacity for a form of associative memory. Crucially, the research explores how context significantly influences retrieval, demonstrating that seemingly robust fact retrieval can be easily manipulated by subtle shifts in wording, a phenomenon termed ‘context hijacking.’ This highlights a key limitation: the lack of robust, semantic understanding. Instead, LLMs appear to associate facts with specific contextual cues, operating more like an associative memory system than a knowledge base with true semantic grounding. This raises critical questions around the interpretability and reliability of LLMs, pushing for further investigation into the underlying representational structures and memory mechanisms of transformer models. The study suggests that the value matrix within the transformer architecture might play a central role in this associative memory, acting as a store of latent representations related to semantic concepts. Future research should focus on strengthening the semantic grounding of information within LLMs to create more reliable and robust systems.

Context Hijacking#

The concept of “context hijacking” reveals a critical vulnerability in Large Language Models (LLMs). LLMs’ responses aren’t solely determined by factual accuracy but are heavily influenced by contextual cues, even when those cues contradict the factual information. This manipulation of LLM outputs through subtle changes in wording or phrasing, without altering the core facts, demonstrates that LLMs operate more like associative memory systems than strictly logical reasoners. The ease with which context can override factual correctness highlights the need for more robust models resistant to contextual manipulation. This phenomenon raises significant concerns about the reliability of LLMs, particularly in high-stakes applications where factual accuracy is paramount. Addressing this vulnerability requires further research into LLM architecture and training methods to ensure context is treated as supportive rather than determinative of the output. The ability to “hijack” the LLM’s output may also have implications for the security and trustworthiness of these models, opening avenues for malicious manipulation that require investigation and countermeasures.

Future of LLMs#

The future of LLMs is brimming with potential, yet fraught with challenges. Improved data efficiency will be crucial, moving beyond massive datasets to more focused, high-quality training. Enhanced interpretability and explainability are essential to build trust and address bias concerns. Robustness to adversarial attacks and hallucination mitigation remain significant hurdles to overcome. We can anticipate more specialized LLMs tailored for specific tasks and domains, potentially collaborating with other AI systems. Ethical considerations surrounding bias, misinformation, and job displacement will continue to shape development. Finally, bridging the gap between LLMs and human-like reasoning remains a long-term objective, potentially requiring a shift towards more general-purpose AI frameworks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

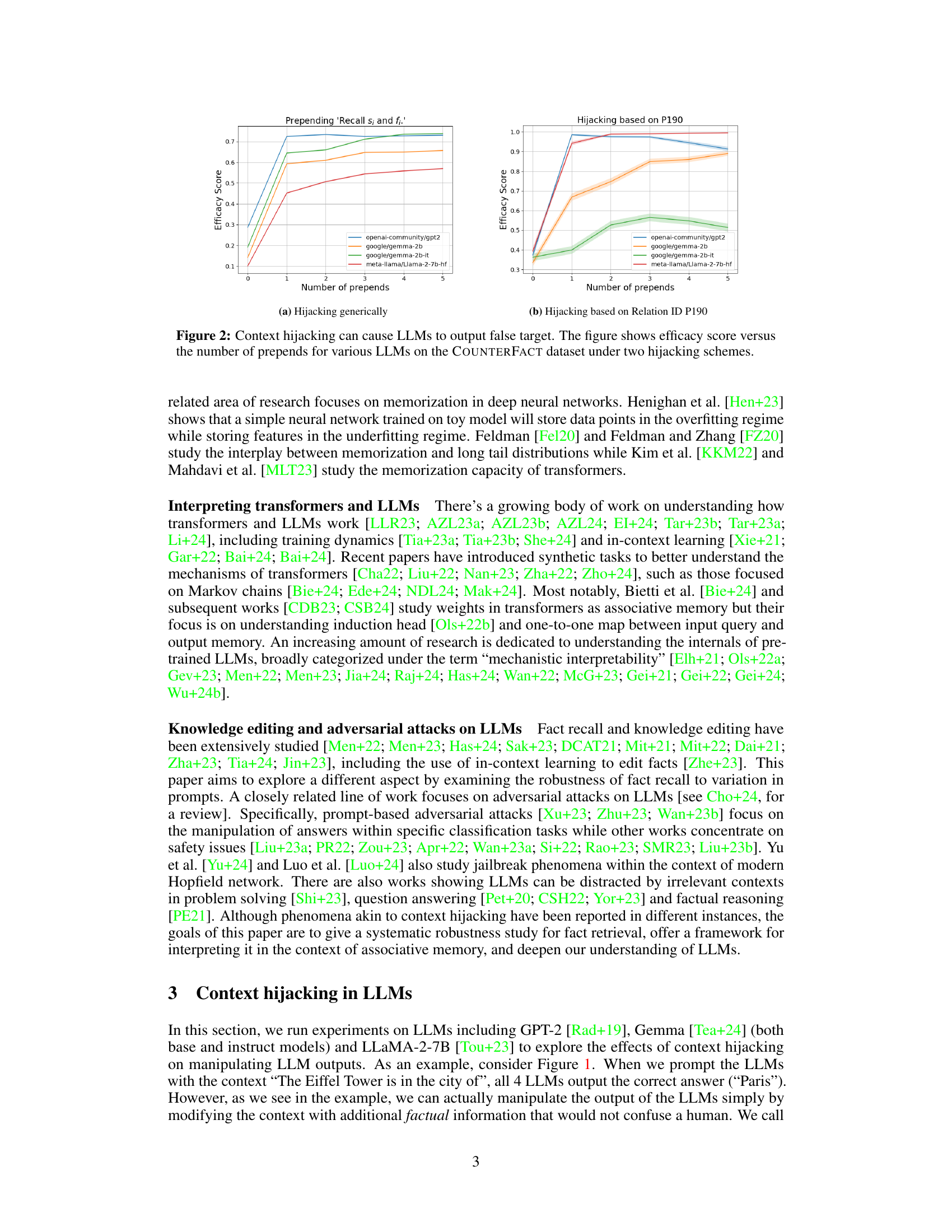

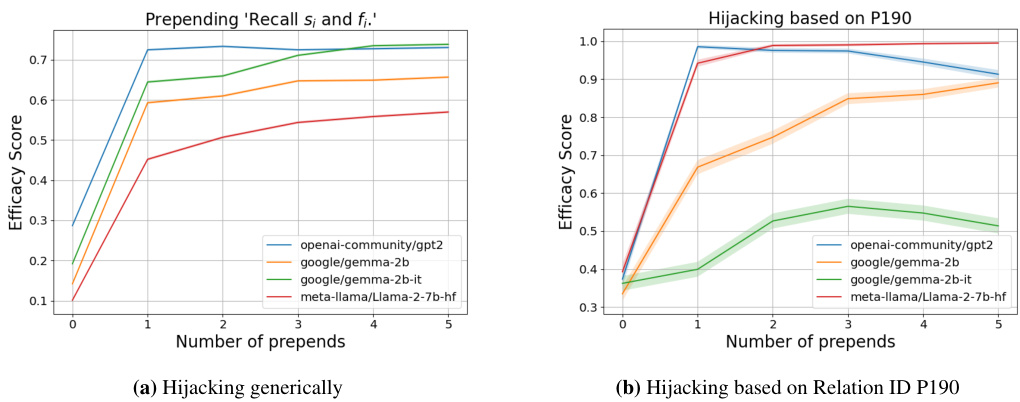

This figure shows the efficacy scores achieved when using different LLMs (openai-community/gpt2, google/gemma-2b, google/gemma-2b-it, meta-llama/Llama-2-7b-hf) on the COUNTERFACT dataset. Two hijacking schemes were used, one that generally hijacks the context and one based on a specific relation ID (P190). The x-axis represents the number of times a hijacking sentence is prepended to the context, and the y-axis represents the efficacy score (higher score indicates more successful hijacking). The results demonstrate the vulnerability of LLMs to context hijacking and how easily their factual outputs can be manipulated by cleverly changing contexts, even without altering the factual meanings of the original context.

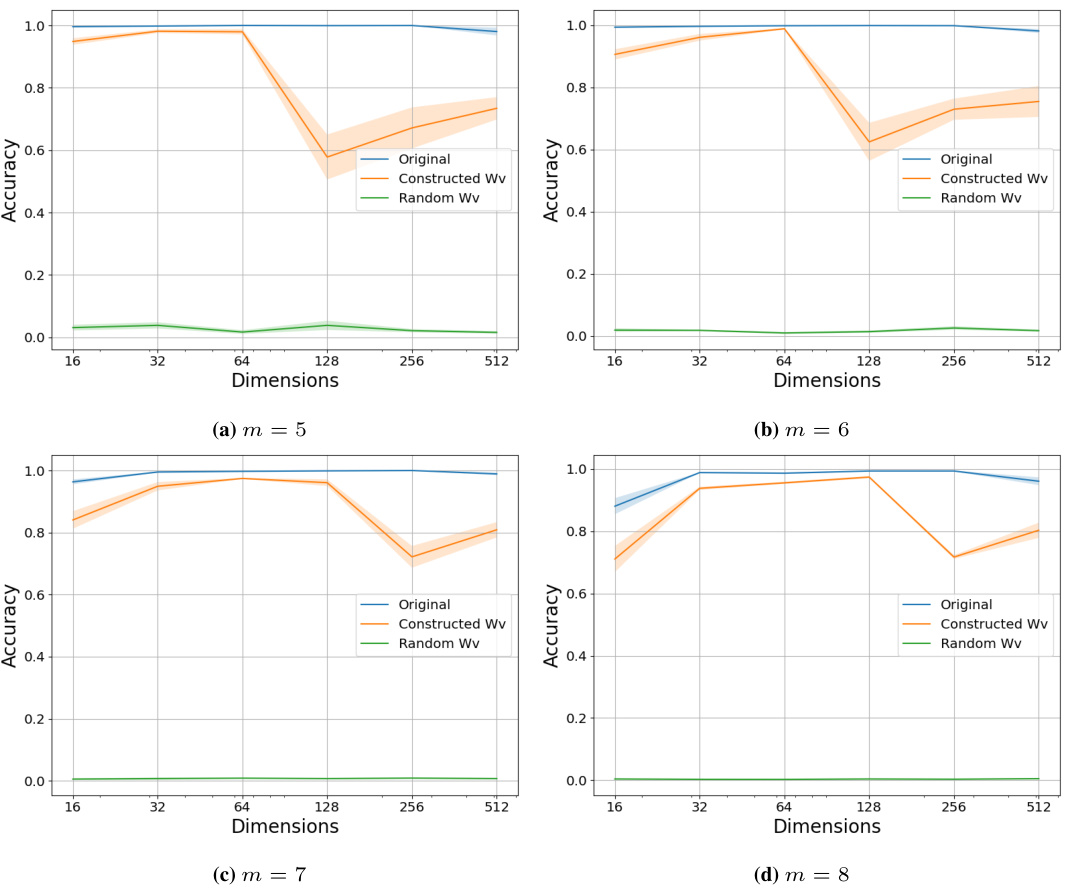

This figure shows three plots that illustrate the key components of a single-layer transformer that solves the latent concept association problem. The first plot shows that training the value matrix (Wv) leads to higher accuracy than using a fixed identity matrix. The second plot demonstrates that the embedding structure, when trained in an underparameterized regime, closely approximates the theoretical relationship described by equation (5.2). The final plot displays the self-attention pattern in the network, illustrating its ability to select tokens within the same cluster based on the structure defined in section 5.4. The results illustrate the collaborative role of the value matrix, embeddings, and attention mechanism in achieving high accuracy.

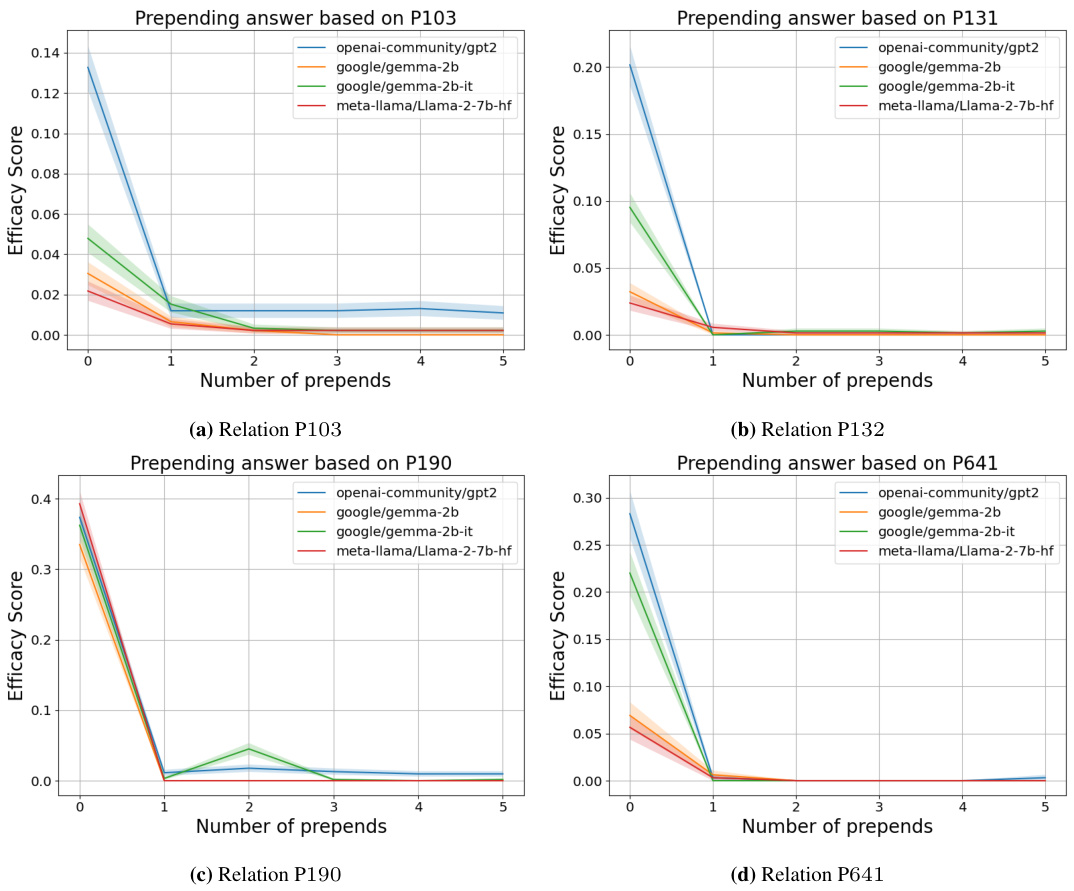

This figure shows the efficacy score for several LLMs (openai-community/gpt2, google/gemma-2b, google/gemma-2b-it, meta-llama/Llama-2-7b-hf) as a function of the number of times the phrase “Do not think of {target_true}” is prepended to the prompt. The efficacy score measures the proportion of times the model outputs the correct token after modifying the context. The results indicate that the reverse context hijacking strategy, in which the true target is mentioned in a negative context, surprisingly leads to an increase in efficacy score. This implies a more nuanced relationship between context and fact retrieval in LLMs than a simple semantic understanding might suggest.

This figure demonstrates how easily LLMs can be manipulated to give incorrect answers simply by changing the context, even without altering the factual meaning of the original prompt. It highlights that LLMs are heavily influenced by the tokens (words) in the prompt, and these tokens may serve as cues that lead LLMs to retrieve the wrong factual information from memory, rather than relying solely on the semantic meaning of the text. The examples show how different models (GPT-2, Gemma, LLaMA) respond differently to subtly altered prompts related to the Eiffel Tower’s location.

This figure shows the efficacy score for various LLMs across different numbers of prepends when using a reverse context hijacking scheme. The reverse scheme involves prepending sentences that contain the true target answer to the original context. The results demonstrate that the efficacy score decreases as more sentences are prepended, indicating that the model becomes less susceptible to manipulation by misleading contextual information.

This figure shows the efficacy score for four different LLMs (openai-community/gpt2, google/gemma-2b, google/gemma-2b-it, meta-llama/Llama-2-7b-hf) when performing context hijacking and reverse context hijacking experiments on relation P1412 of the COUNTERFACT dataset. In context hijacking, additional sentences are added to the prompt to mislead the LLM into providing an incorrect answer, while in reverse context hijacking, sentences that reinforce the correct answer are added. The x-axis represents the number of sentences added (prepends), while the y-axis shows the efficacy score, indicating the percentage of times the LLM was successfully manipulated. This experiment demonstrates that even without using the exact target words in the additional sentences, the manipulation is still effective. The results show that with more added sentences, the efficacy score improves for hijacking and declines for reverse hijacking.

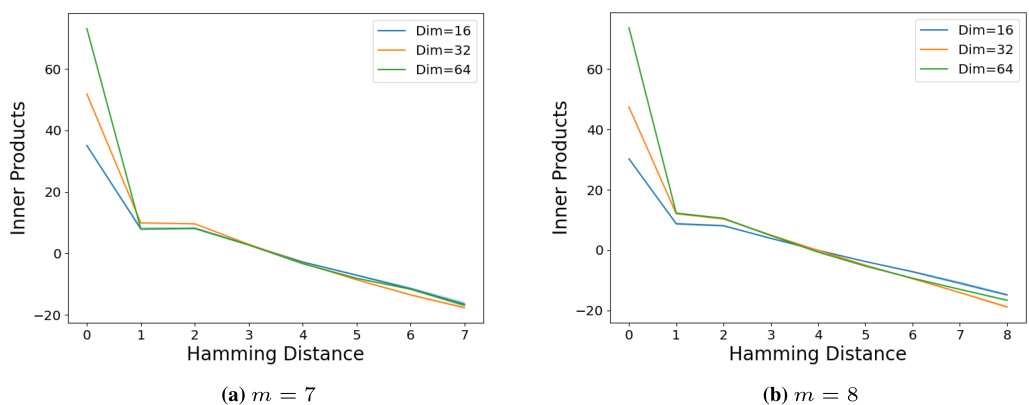

This figure demonstrates the importance of training the value matrix and the embedding structure for achieving high accuracy in latent concept association tasks. It also shows how attention mechanisms are used to select relevant tokens for the task, and highlights the relationship between the inner product of embeddings and Hamming distance.

This figure shows the results of experiments on a single-layer transformer model trained on the latent concept association task. Panel (a) demonstrates the importance of training the value matrix (Wv) for high accuracy, as opposed to using a fixed identity matrix. Panel (b) illustrates the relationship between the inner product of word embeddings and their Hamming distance, showing an approximation to equation 5.2 in the paper. Panel (c) visualizes the attention mechanism and shows that it tends to select tokens from the same semantic cluster, supporting the theoretical analysis.

This figure demonstrates the interplay of different components of a single-layer transformer network in solving the latent concept association problem. Panel (a) shows that training the value matrix (Wv) leads to higher accuracy than using a fixed identity matrix. Panel (b) illustrates the relationship between the inner product of word embeddings and their Hamming distance, showing an approximation to the theoretical formula (5.2). Finally, panel (c) visualizes the self-attention mechanism’s ability to select relevant tokens within the same cluster, highlighting its role in information aggregation.

This figure shows three plots that illustrate the key components of a single-layer transformer network solving the latent concept association problem. Plot (a) compares the accuracy of models with a fixed identity value matrix and those with a trained value matrix, demonstrating the importance of training the value matrix. Plot (b) shows the relationship between the inner product of embeddings and Hamming distance in the underparameterized regime, indicating that the embedding structure approximates a specific mathematical form. Plot (c) depicts the attention pattern within the network, highlighting the ability of the self-attention layer to select tokens from the same cluster, a key mechanism for solving the task.

This figure demonstrates the importance of the value matrix in the transformer model. It also shows the relationship between embedding structure, Hamming distance and the ability of the self-attention layer to select relevant tokens.

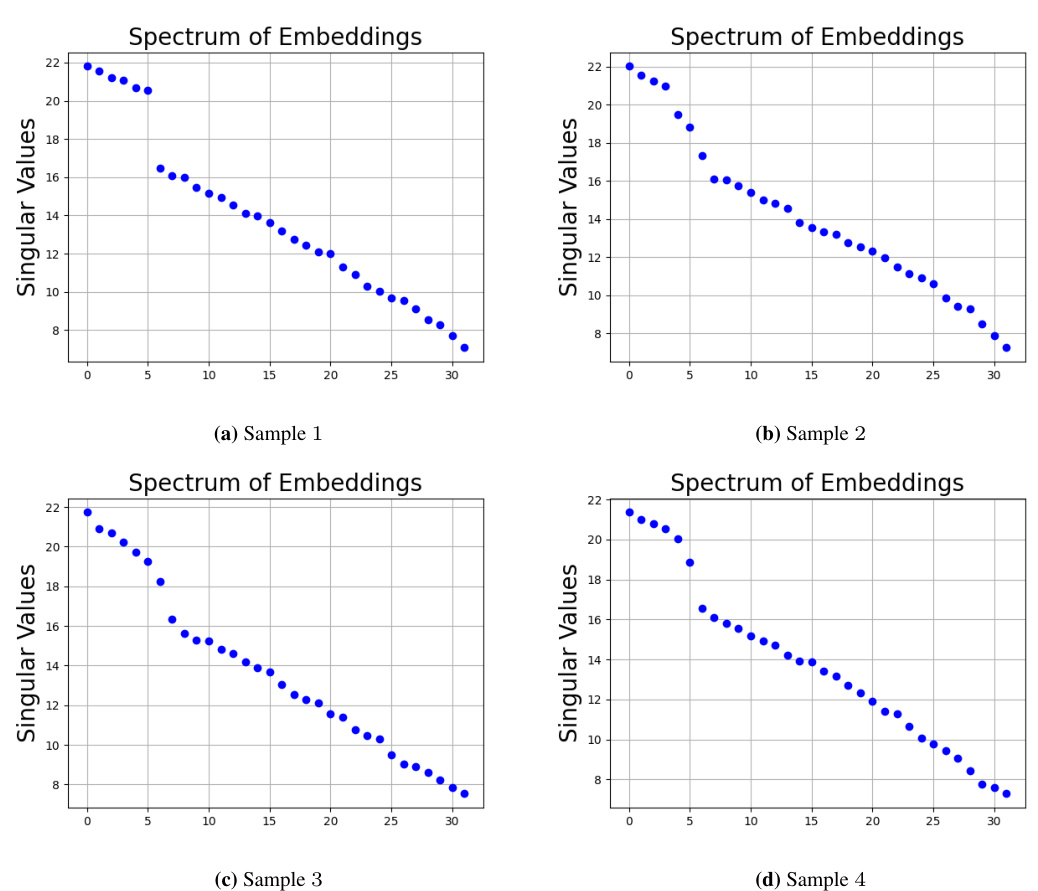

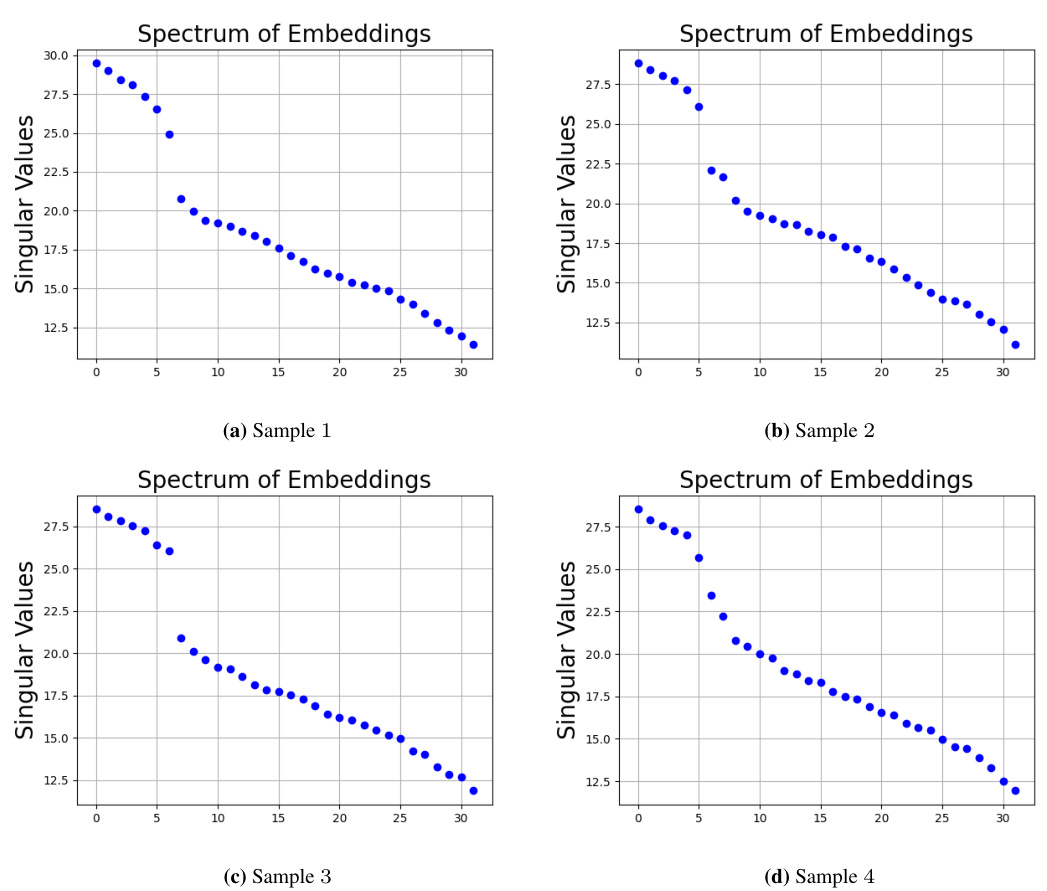

This figure visualizes three key aspects of the single-layer transformer model’s performance on the latent concept association task. Panel (a) compares the accuracy of models with a fixed identity value matrix versus a trained value matrix, showing that training significantly improves accuracy. Panel (b) illustrates the relationship between the inner product of word embeddings and their Hamming distance, which aligns with the theoretical prediction (5.2) in the paper, indicating low-rank structure in the embeddings. Finally, panel (c) presents the average attention scores, demonstrating the model’s ability to focus attention on tokens within the same semantic cluster.

This figure demonstrates the importance of the value matrix in achieving high accuracy in the latent concept association task. It also shows how the trained transformer learns an embedding space that captures the latent relationship between tokens (approximated by equation 5.2), and that the self-attention mechanism helps to select relevant tokens within the same cluster. The results support the paper’s theoretical analysis of the single-layer transformer’s behavior.

This figure shows three plots that demonstrate the importance of the value matrix, the embedding structure, and the self-attention mechanism in the single-layer transformer model for solving the latent concept association problem. Plot (a) compares the accuracy of using a fixed identity value matrix and a trained value matrix, showing that training leads to better performance. Plot (b) illustrates the relationship between the inner product of trained embeddings and their Hamming distances, indicating that the embedding structure approximates the relationship defined in equation (5.2). Plot (c) visualizes the attention pattern of the model, revealing its ability to select tokens within the same cluster which reflects the underlying cluster structure of the data generation process.

This figure shows several examples of how different LLMs (GPT-2, Gemma-2B, Gemma-2B-IT, and LLaMA-7B) respond differently when prompted with slightly different phrasing of the same question. It highlights how easily LLMs’ factual responses can be manipulated through minor contextual changes, which is referred to as ‘context hijacking’. The examples demonstrate that LLMs may not retrieve facts robustly based on semantic meaning alone, but rather rely on specific tokens within the context.

This figure demonstrates how changing the context in prompts can easily manipulate the outputs of LLMs in a fact retrieval task, even without altering the factual meaning. It shows examples for different LLMs (GPT-2, Gemma-2B, Gemma-2B-IT, LLaMA-7B) where providing additional, seemingly unrelated, information in the prompt leads to incorrect answers. This highlights that LLMs are susceptible to context hijacking and suggests that their fact retrieval mechanism is based on associations rather than semantic understanding.

This figure visualizes the interplay of key components (value matrix, embeddings, attention) in a single-layer transformer trained for the latent concept association task. Panel (a) compares the accuracy of using a trained value matrix versus a fixed identity matrix, demonstrating the importance of learning the value matrix. Panel (b) shows the relationship between the inner product of embeddings and their Hamming distance, confirming the embedding structure derived in the theory. Panel (c) illustrates the attention mechanism’s ability to select tokens within the same cluster, enhancing the understanding of information aggregation in the task.

This figure shows the results of experiments on a synthetic latent concept association task using a single-layer transformer model. It demonstrates the importance of training the value matrix (a), the low-rank structure of the learned embedding space (b), and the role of the self-attention mechanism in selecting relevant information based on latent clusters (c) for successful task completion.

This figure shows the efficacy score (a measure of how well the context hijacking worked) plotted against the number of times a certain phrase was prepended to the original prompt. Two different hijacking schemes are compared: one where a generic phrase is added (‘Do not think of {target_false}’) and another using a relation-specific sentence. The graph demonstrates how the success of context hijacking increases as more phrases are prepended to the prompt, for four different large language models (LLMs). This illustrates the lack of robustness of fact retrieval in LLMs and how easily their outputs can be manipulated by changing the context.

This figure shows the efficacy score of two different context hijacking methods on four different LLMs. The x-axis represents the number of times a hijacking sentence was prepended to the prompt. The y-axis shows the efficacy score, representing how often the LLM was successfully tricked into giving a wrong answer. The two hijacking schemes are: generic hijacking (prepending ‘Do not think of {target_false}’) and relation ID-based hijacking (prepending factually correct sentences related to the false target). The figure demonstrates that increasing the number of prepended sentences generally increases the efficacy score, indicating that LLMs’ outputs can be easily manipulated by modifying the context.

Full paper#