↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Analyzing functional data, such as sensor readings over time, requires methods that balance interpretability and predictive power. Current methods either lack expressiveness or are difficult to interpret. This work focuses on the limitations of existing functional data analysis techniques, especially their inability to capture complex relationships and scale to large datasets.

This paper introduces a new approach called semi-structured functional networks (SSFNNs). SSFNNs improve upon current models by combining a structured, interpretable part with a deep neural network. A novel orthogonalization technique is used to resolve issues with model identifiability. The experimental results demonstrate that SSFNNs provide accurate signal recovery, enhanced predictive performance, and better scalability compared to existing methods, making it highly relevant for researchers dealing with complex functional datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in functional data analysis and machine learning because it bridges the gap between interpretable models and deep learning for complex functional data. It offers a scalable and efficient method, addressing the limitations of existing techniques, opening new avenues for research in various fields dealing with functional data like biomechanics and signal processing. The novel orthogonalization technique ensures interpretability while improving predictive performance, making it highly relevant to current trends in interpretable AI.

Visual Insights#

This figure visualizes an example of a function-on-function regression by showing the weight surface, feature signal and the resulting response signal. The weight surface shows the influence of the input function x(s) on the output function y(t). Three areas are highlighted to illustrate this influence: a) An isolated positive weight multiplied with a positive feature signal produces a spike in the response, b) A negative weight multiplied with positive features produces a bell-shaped negative outcome, and c) a large positive weight region multiplied with positive features produces a slight increase in the response.

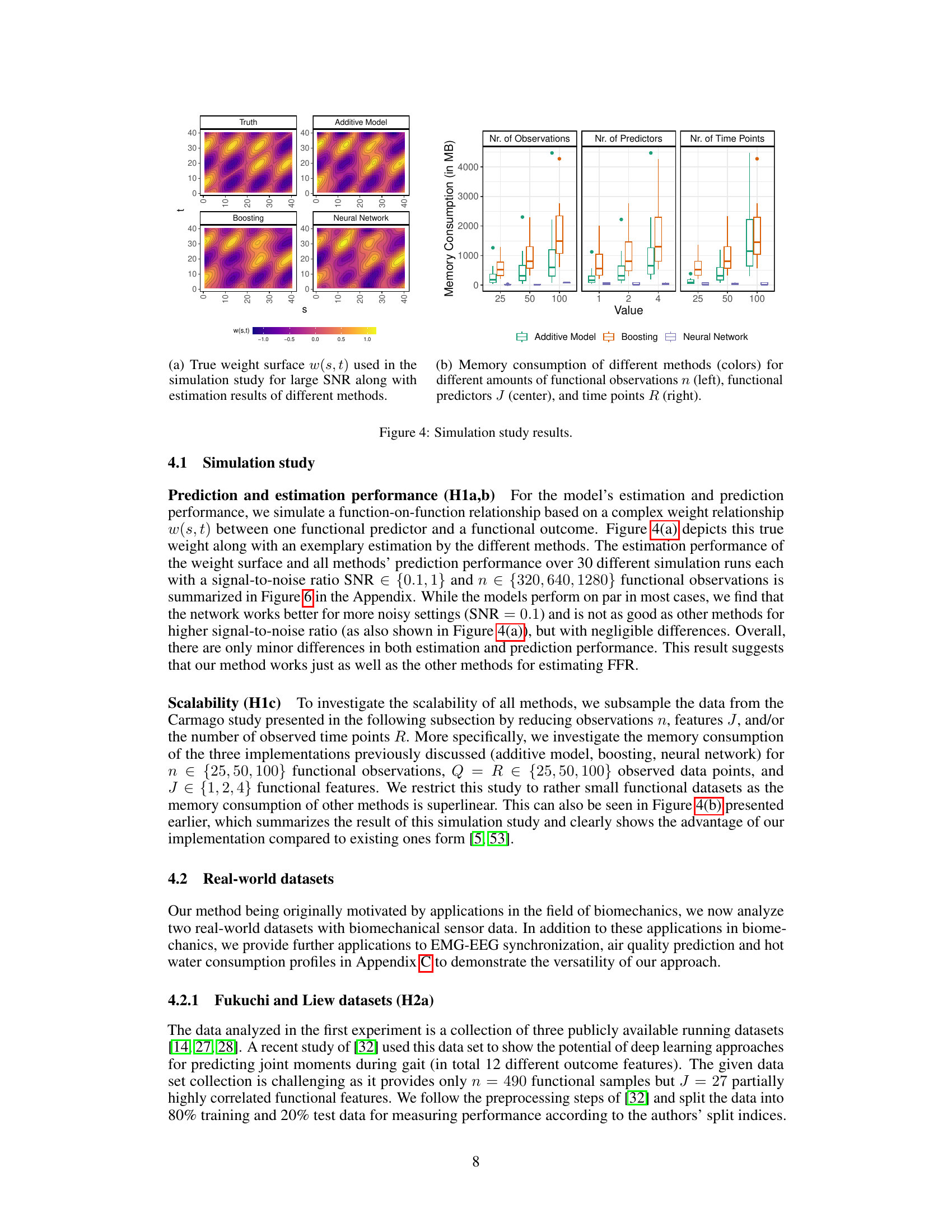

The table presents the relative root mean squared error (RMSE) for different methods in predicting 12 different biomechanical outcomes using two datasets (Fukuchi and Liew). It compares the performance of an additive model, a functional neural network (FNN), a semi-structured functional neural network (SSFNN), and boosting, both using a selected set of features and all features. The lowest relative RMSE indicates better performance.

In-depth insights#

Functional SSN#

The concept of “Functional SSN”, or Functional Semi-Structured Networks, represents a significant advancement in machine learning, particularly within the realm of functional data analysis. It cleverly combines the interpretability of additive models with the expressive power of deep neural networks. This fusion addresses a critical limitation of traditional functional data analysis methods, which often struggle with higher-order interactions and non-linearities, especially in high-dimensional datasets. The key innovation lies in adapting the SSN framework to handle functional data, effectively modeling complex relationships between functional inputs and outputs while maintaining a degree of interpretability. This is achieved by carefully integrating functional regression components into the SSN architecture, allowing for the extraction of interpretable feature effects alongside the ability to capture complex non-linear patterns. The use of tensor-product basis functions further enhances scalability and efficiency. The post-hoc orthogonalization technique is crucial for ensuring the identifiability of the additive model component, a common challenge in SSN approaches, guaranteeing that the model’s interpretability is not compromised by the deep learning part. The authors demonstrate the method’s effectiveness through numerical experiments, including both simulated and real-world biomechanics datasets, showcasing its superior performance and scalability compared to competing methods. This methodology holds significant promise for various applications, particularly those involving large-scale functional data where interpretability and scalability are both essential.

Interpretable FDA#

Interpretable Functional Data Analysis (FDA) is a crucial area bridging the gap between the complex nature of functional data and the need for understandable insights. Current FDA methods often sacrifice interpretability for model complexity and predictive power. The challenge lies in balancing the richness of functional data representations, which capture intricate patterns in data evolving over time or space, with the ability to extract clear, human-interpretable rules and relationships. Developing interpretable FDA requires innovative approaches that move beyond simple visualizations and descriptive statistics. This could involve incorporating techniques from explainable AI (XAI), such as LIME or SHAP values, to highlight the influential aspects of functions in the predictive process. Feature selection and dimensionality reduction methods tailored to functional data are also critical to manage the complexity inherent in functional objects, and in ensuring that resulting models are not overly complex. Ultimately, successful interpretable FDA will require a multi-faceted approach combining innovative algorithms, effective visualization methods, and careful consideration of the domain context to ensure both model accuracy and meaningful insights.

Scalable Methods#

Scalable methods are crucial for handling large datasets, a common challenge in functional data analysis. The paper addresses this by proposing a functional semi-structured network (SSN) approach that improves upon existing functional regression techniques. Key to scalability is a careful implementation of the structured part of the SSN, avoiding the unfavorable scaling found in classical FFR and boosting methods. This is achieved through two main improvements: array computations, which avoid the formation of an explicitly large matrix during forward passes, and basis recycling, reusing pre-computed bases to reduce memory costs. These optimizations, coupled with an efficient implementation of the deep neural network component, allow the model to efficiently handle datasets with high numbers of features, observations, and time points. The result is a method that maintains accuracy while being scalable to larger-scale functional datasets, a significant advance in functional data modeling.

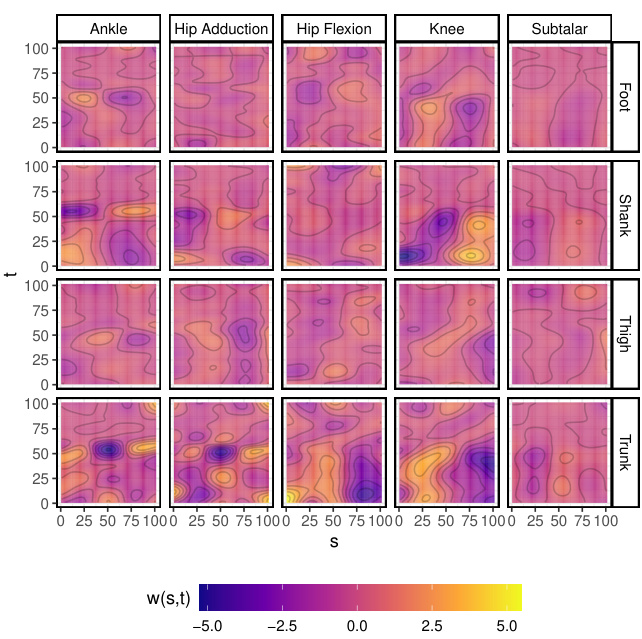

Biomechanics App#

The application of machine learning in biomechanics research, particularly concerning joint moments, offers significant advantages. Analyzing joint moments provides insights into muscular activities, motor control strategies, and injury risks. The use of machine learning allows researchers to predict these ’expensive’ signals using more readily available sensor data from mobile devices, overcoming limitations of traditional laboratory data collection. Existing methods, however, struggle with generalization and lack a clear understanding of the learned relationship. This necessitates more sophisticated methods that can accurately capture all interactions and non-linearities while scaling well for large datasets. The research highlights the potential for improving both scalability and predictive accuracy using innovative approaches that improve the interpretability of functional data analysis.

Future Research#

The paper suggests several promising avenues for future research. Extending the model to handle non-linear functional relationships is crucial for broader applicability. The current model relies on additive structures, limiting its ability to capture complex interactions. Investigating more expressive non-linear models while maintaining interpretability is key. Incorporating sparsity penalties in high-dimensional settings would improve computational efficiency and potentially enhance generalization. The high dimensionality of functional data often necessitates careful regularization, and sparse models could be more robust and interpretable. Finally, exploring the extension of post-hoc orthogonalization techniques to more complex network architectures will help maintain identifiability and interpretability in even more complex functional data models. This is particularly important as larger, more detailed datasets become available.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows two different architectures for semi-structured functional neural networks. (a) shows a shared encoder-decoder approach, where both the interpretable and deep parts share the encoding and decoding steps. (b) shows an architecture with a separate deep functional neural network that takes the functional input directly and combines the output with the interpretable part. Both architectures aim to combine the interpretability of structured models with the flexibility of deep neural networks.

This figure shows the estimated weight surfaces for a single functional predictor (shank gyroscope) before and after applying post-hoc orthogonalization. Each subplot represents a different joint, showing the effect of the predictor on the joint’s movement over time. The top row shows the uncorrected weights, which are mostly flat, indicating that the model isn’t correctly capturing the relationship. The bottom row displays the corrected weights, revealing more interpretable relationships with distinct patterns. For example, in the second plot, a higher gyroscope value early on has a negative effect on hip adduction movement.

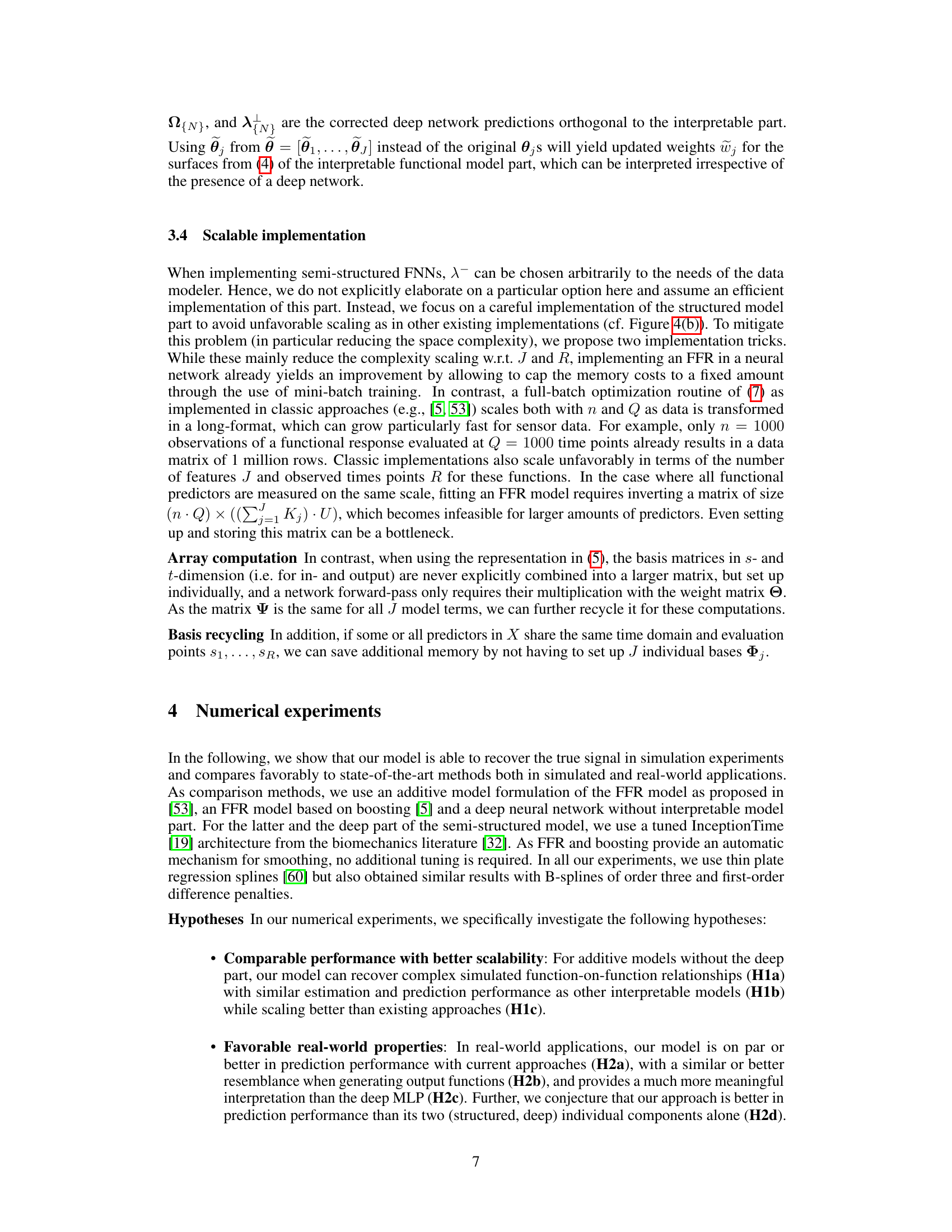

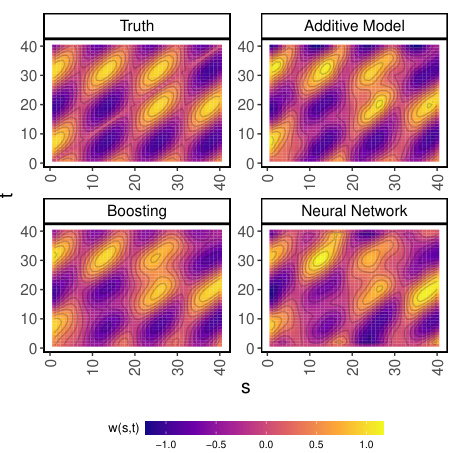

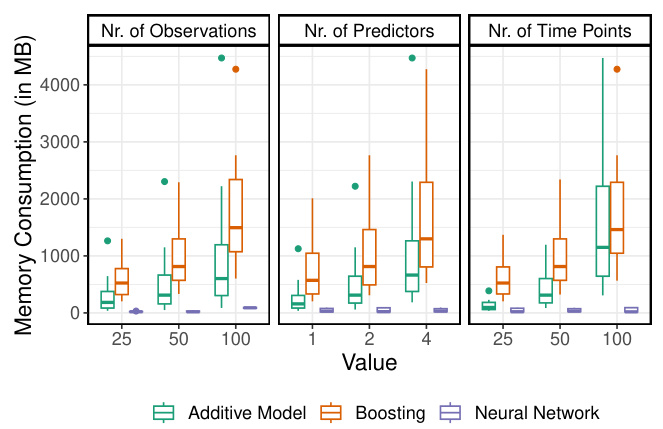

This figure presents results from a simulation study designed to evaluate the performance of different methods for estimating and predicting functional relationships. Panel (a) displays a comparison of the true weight surface used in the simulation (ground truth) against estimated weight surfaces generated by different methods. It shows that the methods perform reasonably well, with minor differences primarily evident in the noisier setting (SNR = 0.1). Panel (b) illustrates the memory consumption of various methods across different scales of data (number of observations, predictors, time points). This clearly demonstrates the scalability advantages of the proposed approach compared to existing methods, particularly as the size of the data increases.

This figure presents the results from a simulation study. Panel (a) shows the true weight surface (w(s,t)) used in the simulation along with estimation results from different methods (additive model, boosting, and neural network). It demonstrates how accurately each method estimates the true weight surface, which represents the relationship between input and output signals. Panel (b) displays the memory consumption of the different methods under varying conditions: changing the number of functional observations (n), functional predictors (J), and time points (R). It illustrates the scalability and efficiency of the different approaches for handling functional data of different sizes and complexities.

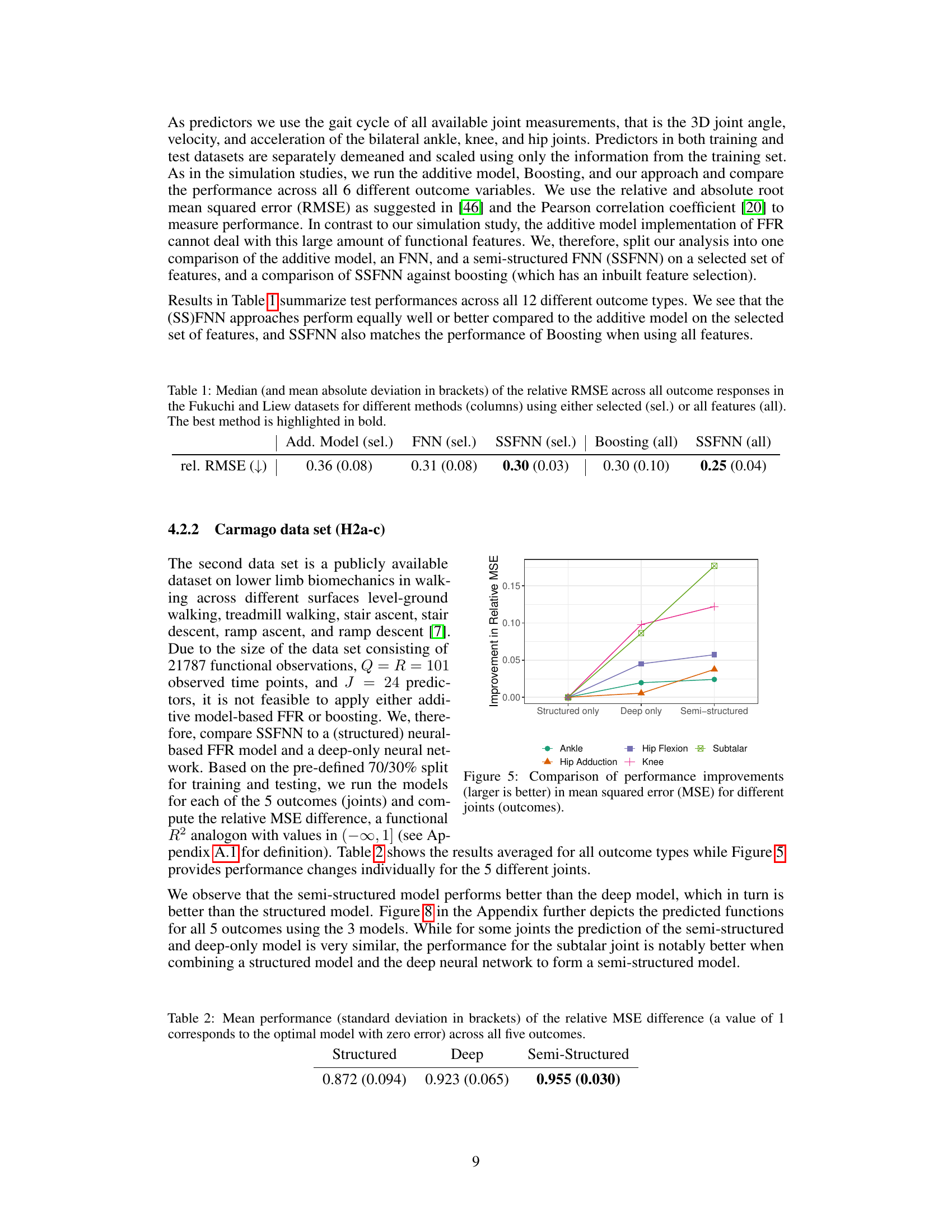

This figure compares the improvement in mean squared error (MSE) achieved by three different modeling approaches for predicting five different joint outcomes (ankle, hip adduction, hip flexion, knee, and subtalar). The x-axis represents the three approaches: a structured model (FFR), a deep-only model (InceptionTime network), and the proposed semi-structured model. The y-axis shows the relative improvement in MSE, indicating how much better each model performs compared to a baseline. The figure suggests the semi-structured model, which combines the interpretable properties of the structured model with the flexibility of the deep model, significantly improves prediction performance across all joints.

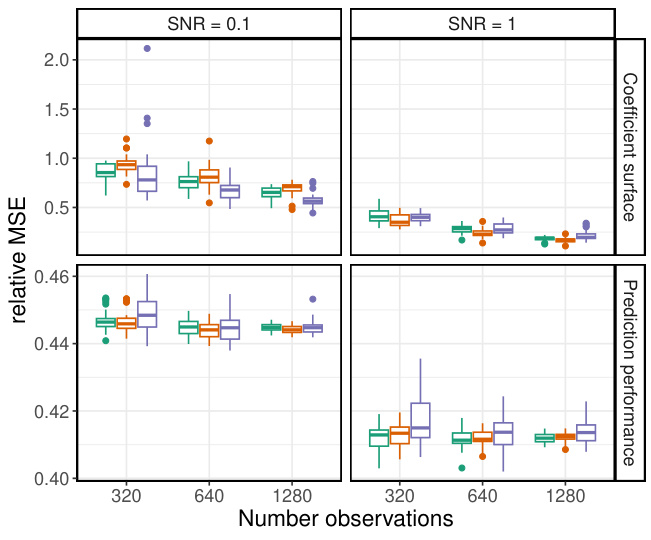

This figure shows the results of a simulation study comparing the performance of different methods in estimating and predicting a function-on-function relationship. The top panels display the relative mean squared error (MSE) of the estimated weight surface, while the bottom panels show the relative MSE of the predictions. The results are shown for different numbers of observations (n) and signal-to-noise ratios (SNR). Different colors represent different methods: Additive Model, Boosting, and Neural Network. The figure demonstrates that the methods perform similarly in terms of estimation and prediction, but the neural network performs slightly better for lower SNR.

This figure shows the estimated weight surfaces for a single functional predictor (shank gyroscope) before and after applying post-hoc orthogonalization. The effect of the predictor on different joint moments (Ankle, Hip Adduction, Hip Flexion, Knee, Subtalar) is visualized. Before correction, the interpretable model part shows little to no effect; after correction, distinct patterns appear, indicating the predictor’s influence on specific joint moments at different times.

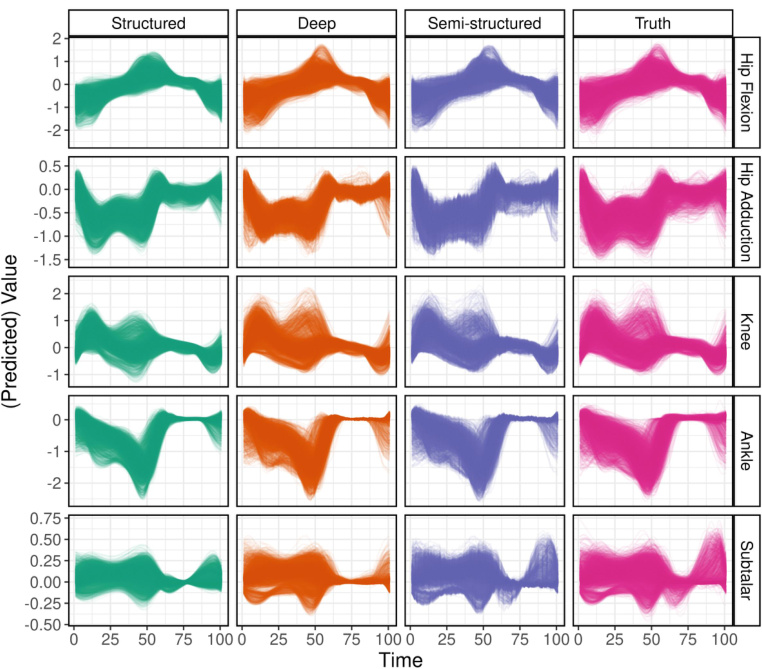

This figure compares the predictions of three different models (structured, deep, and semi-structured) with the true sensor data for five different joints (hip flexion, hip adduction, knee, ankle, and subtalar). Each row represents a different joint, and each column represents a different model or the true data. The plot shows the predicted values and their variation over time for each model and joint. This visual comparison helps to assess the accuracy and performance of each model in capturing the true patterns of joint movements.

More on tables

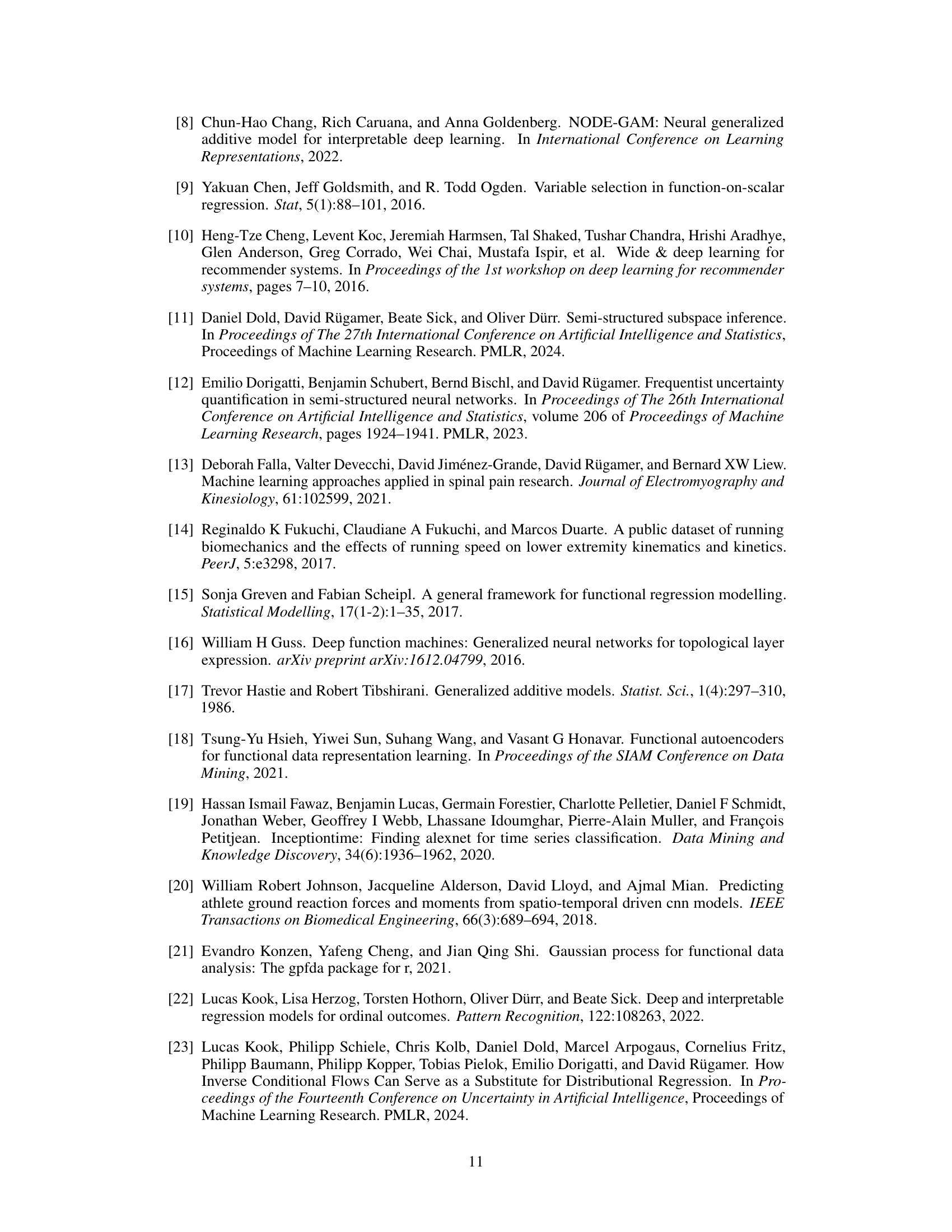

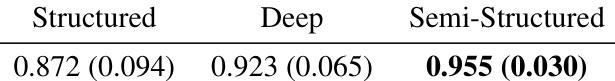

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the relative Mean Squared Error (MSE) difference for three different models: Structured, Deep, and Semi-Structured. The relative MSE difference is a measure of prediction performance, where a value of 1 indicates a perfect fit, and lower values suggest poorer fits. The table summarizes the performance across five different outcome variables (joints). The Semi-Structured model shows the best performance overall.

This table compares the performance of a deep-only neural network model (from reference [32]) and the proposed semi-structured functional network (SSFNN) model. The comparison is done across multiple joints and dimensions of movement data (ankle, com, hip, knee, each with three dimensions). The values represent a performance metric (likely relative MSE difference, based on context of paper), with lower values indicating better model performance. The table demonstrates that the semi-structured model generally achieves either similar or improved performance compared to the deep-only model.

The table presents a comparison of the performance of four different models: Boosting, FNN, SSFNN (a), and SSFNN (b) on a dataset used in cognitive affective neuroscience research. The performance is evaluated using two metrics: Relative RMSE (lower is better) and Correlation (higher is better). The table shows that the FNN model performs competitively with Boosting, while the semi-structured FNN models (SSFNN) display varying levels of performance, with SSFNN (a) showing higher correlation and SSFNN (b) demonstrating lower relative RMSE but similar correlation to the FNN.

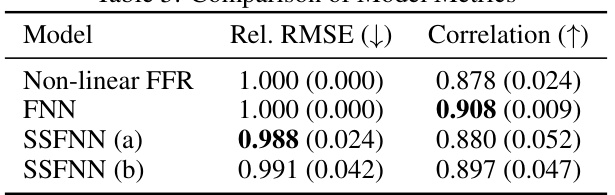

This table presents a comparison of model metrics, specifically focusing on the relative root mean squared error (Rel. RMSE) and correlation, for four different models used in predicting air quality: a non-linear functional additive model (FFR), a functional neural network (FNN), and two versions of a semi-structured functional neural network (SSFNN). The lower the Rel. RMSE value, the better the model’s predictive performance. A higher correlation indicates a stronger relationship between the predicted and actual values.

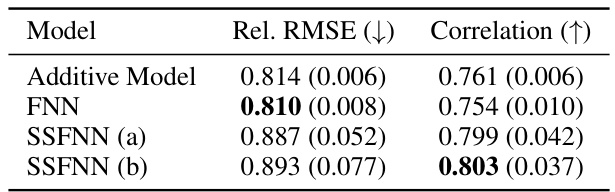

This table presents the results of comparing four different models (Additive Model, FNN, SSFNN (a), and SSFNN (b)) for predicting hot water consumption. The metrics used for comparison are Relative RMSE (lower is better) and Correlation (higher is better). The results show that the FNN and the semi-structured models (SSFNN) achieve similar or better prediction accuracy compared to the simpler Additive Model.

Full paper#