↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

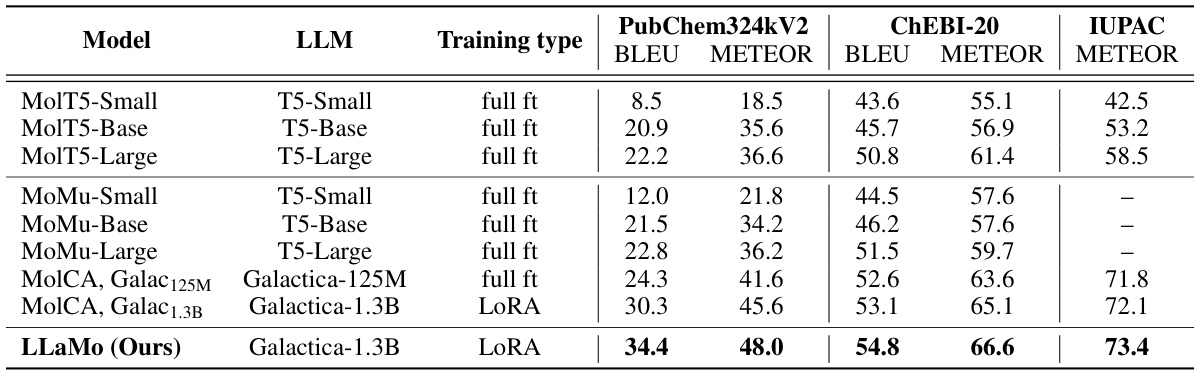

TL;DR#

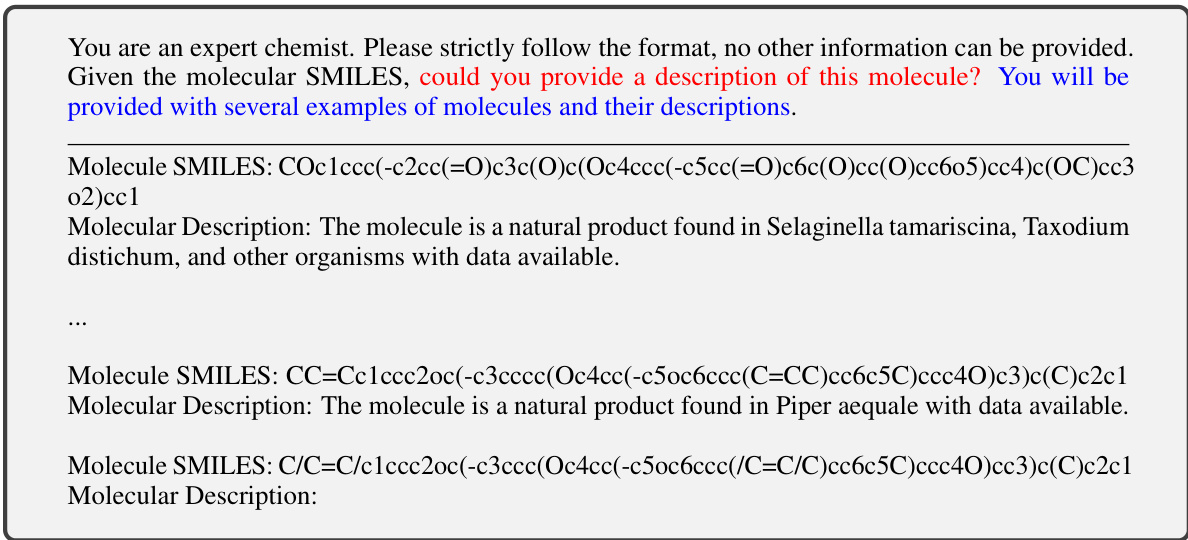

Molecular machine learning often struggles with the interpretability and multi-modality challenges of integrating text and molecular structures. Existing models often fall short in open-ended molecule-to-text generation tasks which limits practical application. Large Language Models (LLMs) have shown impressive progress in instruction-following and text generation, offering a potential solution. However, their application in the molecular domain is underdeveloped.

This work introduces LLaMo, a large molecular graph language model that uses a multi-level graph projector to bridge the gap between language and graph modalities. It incorporates machine-generated molecular graph instruction data to instruction-tune the model for general-purpose molecule and language understanding. The results demonstrate that LLaMo shows state-of-the-art performance in molecular description generation, property prediction, and IUPAC name prediction, outperforming existing LLM-based approaches.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it bridges the gap between language models and molecular graph analysis, paving the way for more advanced and practical applications in drug discovery, material science, and other chemical domains. The introduction of instruction-tuning and multi-level graph projection enhances the model’s capabilities significantly, representing a notable advance in the field of molecular machine learning.

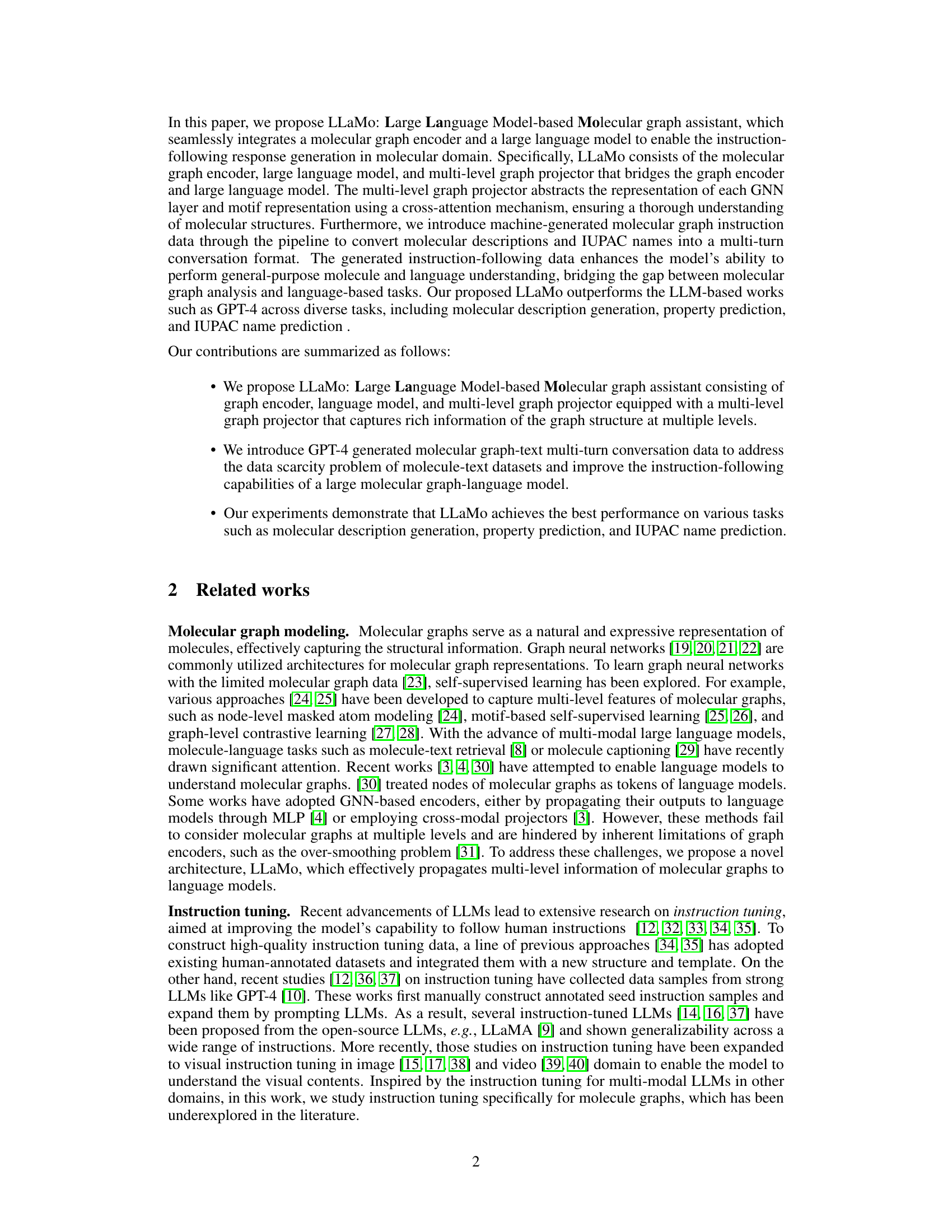

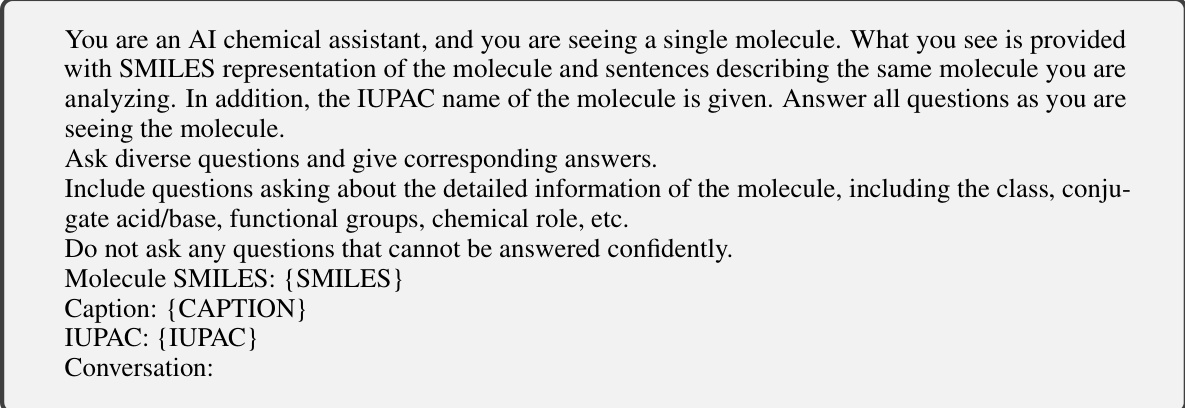

Visual Insights#

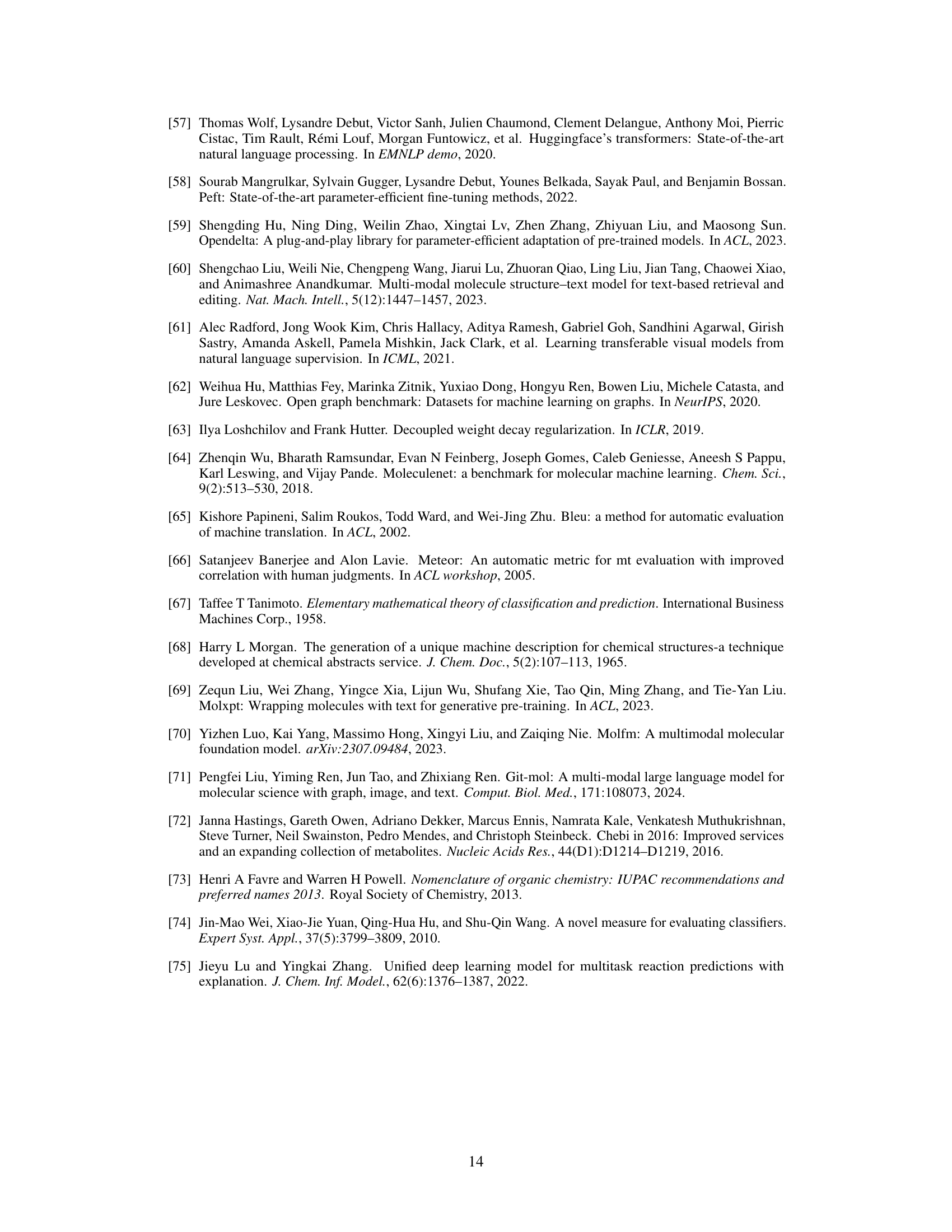

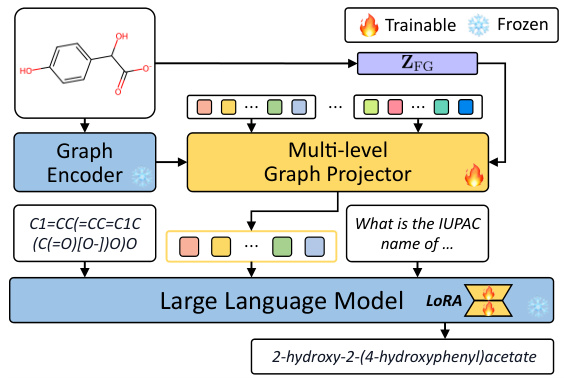

The figure illustrates the architecture of LLaMo, a large language model-based molecular graph assistant. It shows the three main components: a graph neural network (GNN) encoding a 2D molecular graph; a multi-level graph projector transforming the GNN output into molecular graph tokens; and a large language model generating a response based on the tokens, input SMILES notation, and an instruction. The multi-level projector uses cross-attention to integrate information from multiple GNN layers and motif representations, improving the model’s understanding of molecular structure.

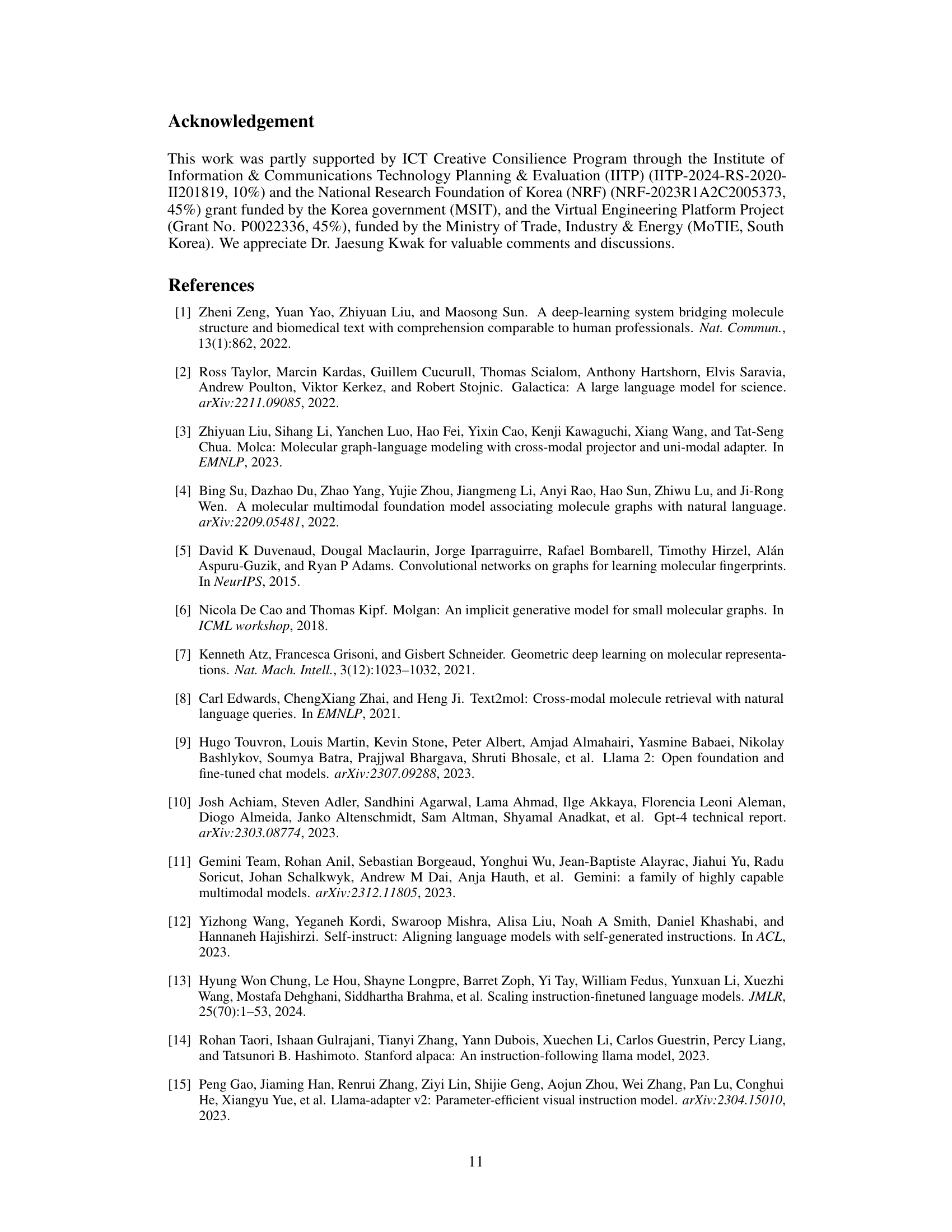

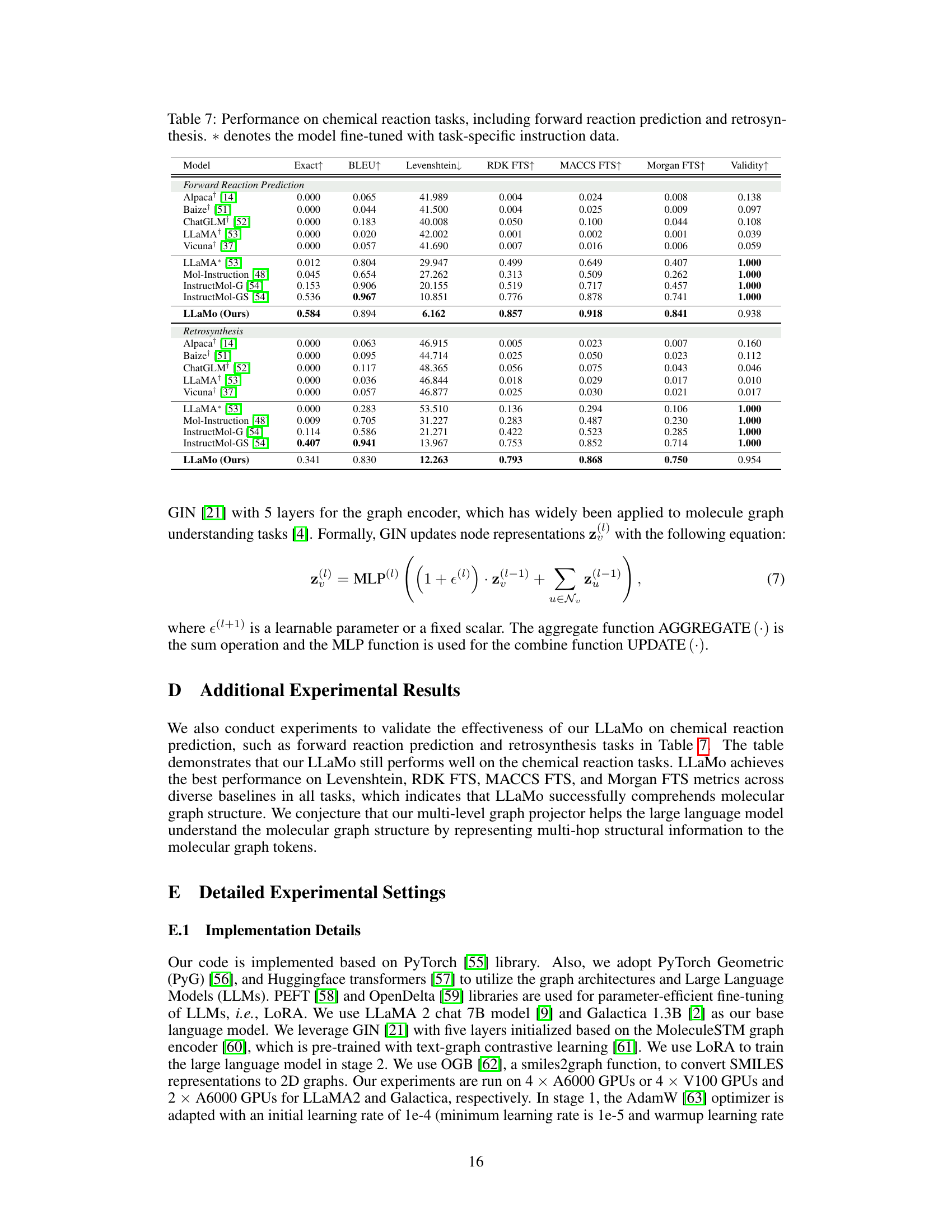

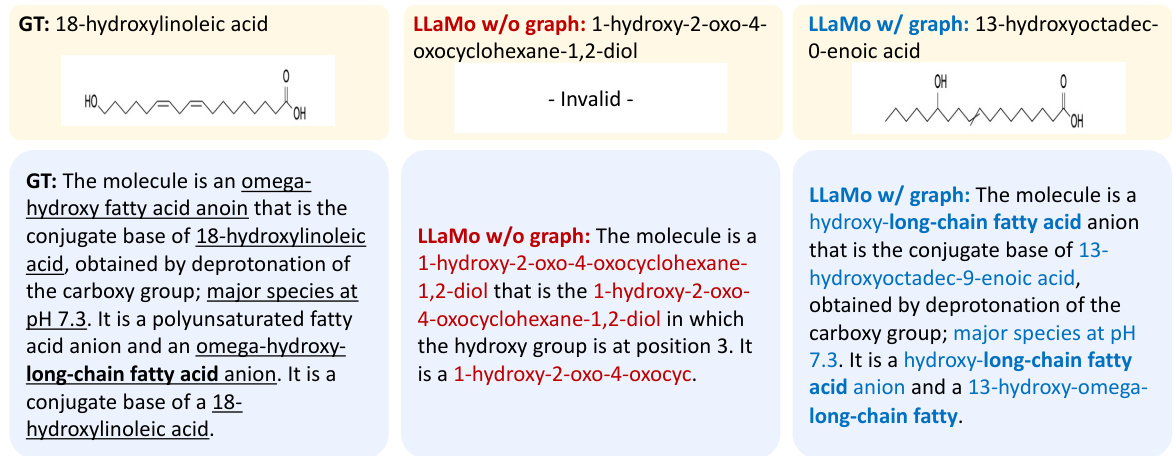

This table presents the performance comparison of various generalist models (including GPT-3.5, GPT-4, Galactica, and LLaMA) on three tasks: molecule description generation, IUPAC name prediction, and property prediction. The metrics used are BLEU, METEOR, and MAE. It shows how the proposed LLaMo model outperforms other models, especially when instruction tuning is applied. The table also notes limitations with some models (LLaMA2 failing to provide numerical output for one metric).

In-depth insights#

LLaMo: Graph Assistant#

LLaMo, a Large Language Model-based Molecular Graph Assistant, presents a novel approach to molecular understanding by integrating graph neural networks (GNNs) with LLMs. The core innovation lies in a multi-level graph projector that effectively bridges the gap between graph and language modalities, translating complex molecular graph representations into tokens readily processed by the LLM. This design allows for a richer understanding of molecular structures by considering information at multiple levels, overcoming limitations of simpler graph-to-text methods. Furthermore, the use of instruction-tuned LLMs and machine-generated molecular graph instruction data enhances LLaMo’s ability to perform a wider range of tasks, including property prediction, description generation, and IUPAC name prediction. This innovative framework promises to significantly advance the field of molecular machine learning, offering a more interpretable and versatile approach compared to existing models. The ability of LLaMo to perform well in several tasks indicates a strong level of generalizability, suggesting broader applications in drug discovery and materials science.

Multi-Level Projection#

The concept of “Multi-Level Projection” in the context of a molecular graph-based language model is a powerful technique to bridge the gap between graph and language modalities. It leverages the hierarchical nature of molecular graphs, capturing information at multiple levels of abstraction (e.g., atoms, functional groups, whole molecules). Instead of relying solely on high-level representations from a graph neural network, which can suffer from over-smoothing, a multi-level approach aggregates features from various GNN layers. This preserves fine-grained local information alongside the broader context, improving the model’s ability to learn nuanced relationships between molecular structure and properties. By incorporating motif representations (such as functional groups) via cross-attention, the projector enriches the graph tokens fed to the language model with domain-specific knowledge. This sophisticated method significantly improves the model’s performance on various tasks such as molecular description generation and property prediction. The integration of multiple levels of detail leads to a more comprehensive understanding of the molecular graph and enables the generation of more accurate and informative descriptions.

Instruction Tuning#

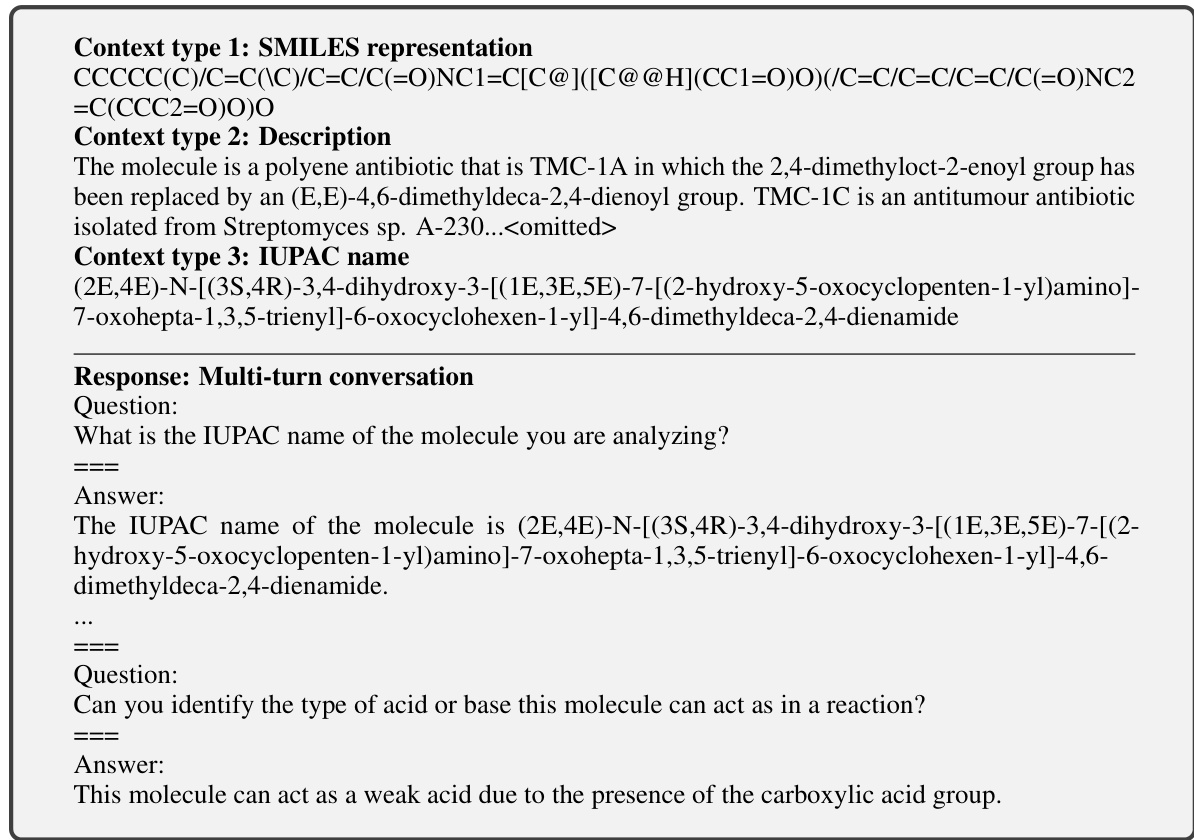

Instruction tuning, a crucial advancement in large language models (LLMs), involves fine-tuning pre-trained models on a dataset of instruction-following examples. This technique significantly enhances the models’ ability to understand and respond to diverse instructions, bridging the gap between human intent and machine execution. The success of instruction tuning hinges on the quality and diversity of the instruction dataset. High-quality datasets, often created semi-automatically by leveraging powerful LLMs, enable the development of general-purpose models capable of handling a wide range of tasks. However, data scarcity remains a challenge, particularly in specialized domains such as molecular graph analysis, limiting the effectiveness of instruction tuning in these areas. Moreover, instruction tuning presents the risk of overfitting to the specific instructions in the training data, potentially hindering the model’s ability to generalize to novel instructions. The development of robust methods for creating and utilizing instruction data, along with careful consideration of potential biases and limitations, are critical for realizing the full potential of this promising technique.

Ablation Experiments#

Ablation experiments systematically remove components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In a research paper, this section would typically present results showing the effects of removing specific model elements, such as layers in a neural network or specific data augmentation techniques. A well-designed ablation study isolates the impact of each component, allowing researchers to understand which parts are most crucial for achieving good performance and which ones are less important or even detrimental. The results would usually be presented in tables or graphs showing the model’s performance with and without each element, providing a quantitative measure of the component’s impact. Analyzing these results reveals the model’s architecture and the importance of specific design choices. A thorough ablation study strengthens the paper’s claims by providing compelling evidence for design decisions and justifying the final model’s architecture. It also helps to identify areas for future improvements or potential limitations.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore enhanced multi-modality by integrating additional data types beyond molecules and text, such as images (e.g., microscopy data) or spectra. A promising area lies in improving the interpretability of LLaMo’s predictions, providing insights into the reasoning process. This could involve developing methods to visualize attention mechanisms or exploring explainable AI (XAI) techniques. Scaling up LLaMo to handle larger and more complex molecules will be essential for tackling real-world problems in drug discovery and materials science. Finally, extending LLaMo’s capabilities to encompass a wider range of tasks is crucial, including retrosynthesis prediction and reaction optimization. Exploring different architectures and training paradigms could lead to significant advancements in the performance and efficiency of large molecular graph language models. The development of more sophisticated datasets containing diverse and comprehensive molecular information will be key to achieving these goals. Ultimately, improving the instruction-following capabilities of LLMs in the context of molecular data is a fundamental direction for future research.

More visual insights#

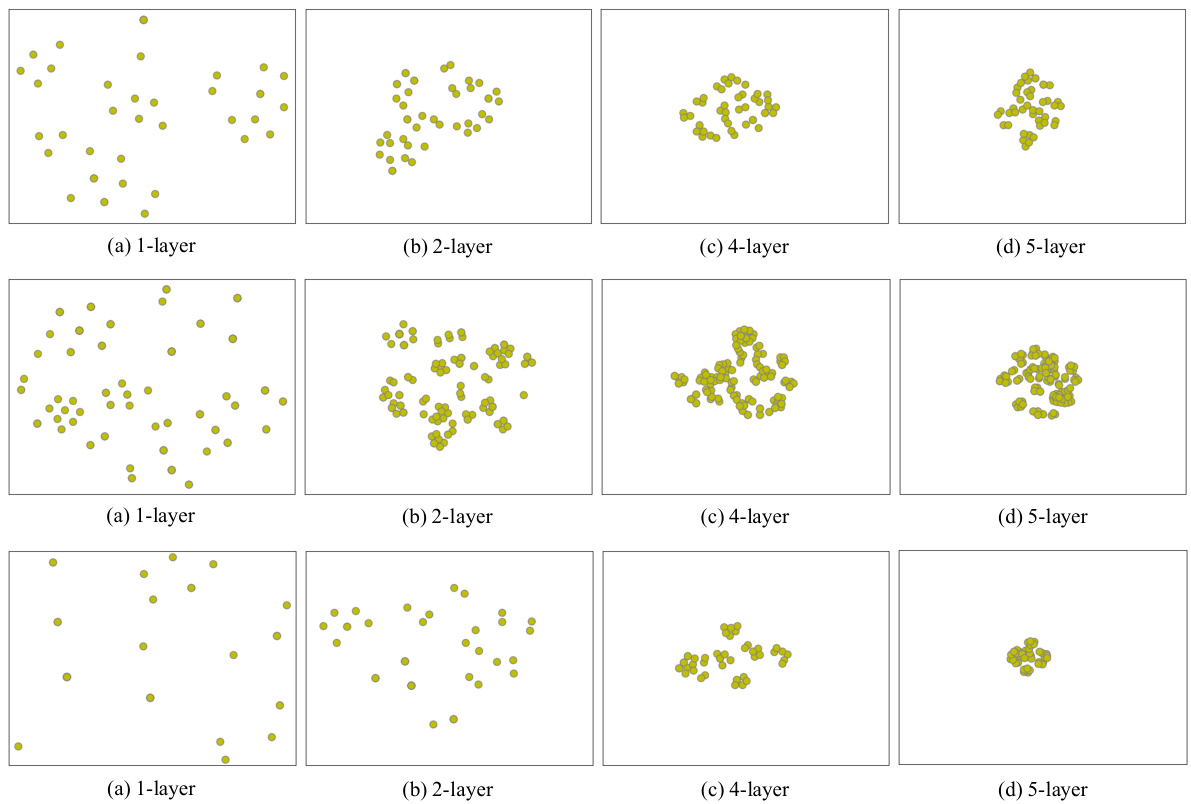

More on figures

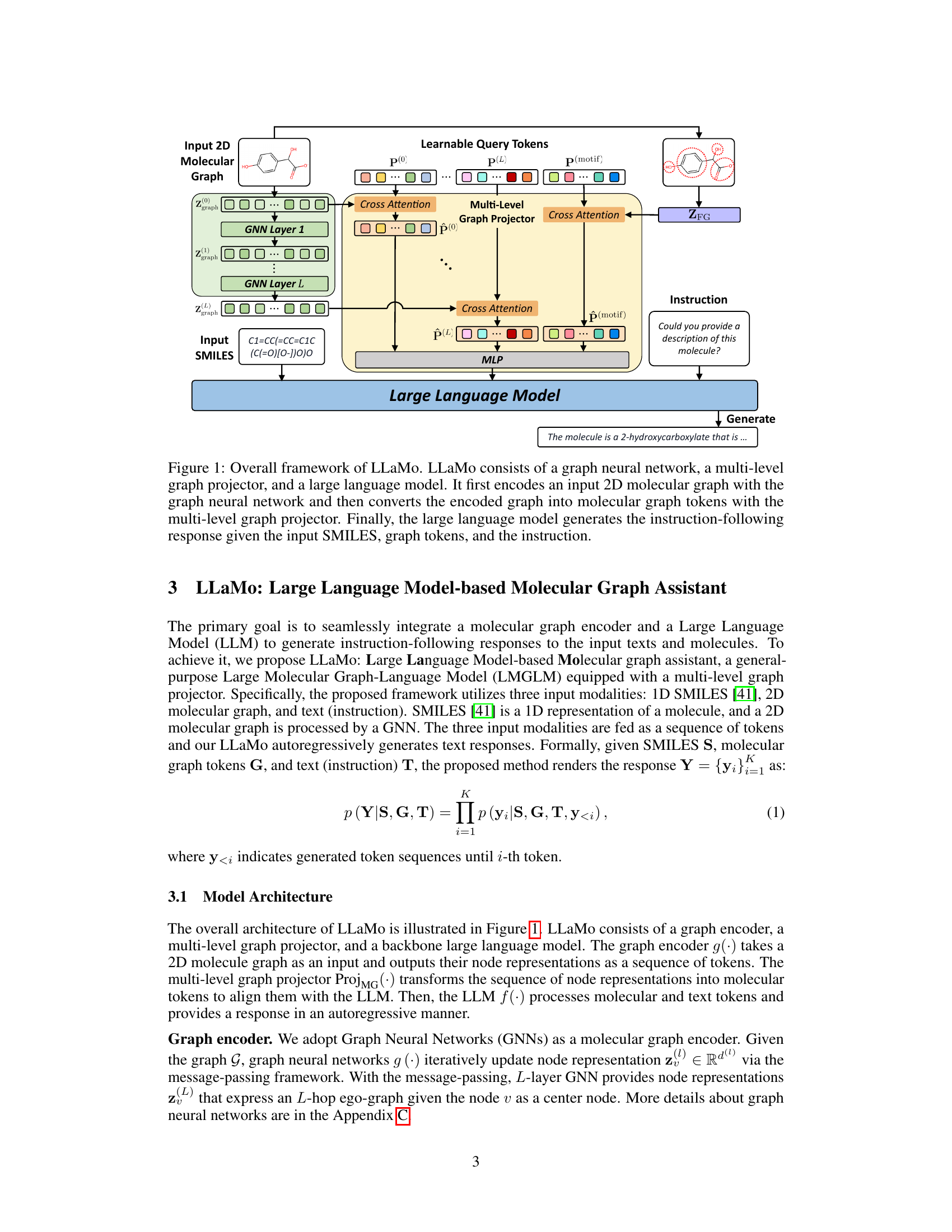

This figure visualizes the impact of the number of layers in a graph neural network (GNN) on node representations. It shows four subfigures (a, b, c, d), each representing the node representations (yellow dots) from a GNN with 1, 2, 4, and 5 layers, respectively, applied to the same molecular graph. As the number of layers increases, the node representations become indistinguishable (they collapse). This phenomenon, known as over-smoothing, highlights a limitation of using only high-level features from deep GNNs for tasks involving local graph information, motivating the use of a multi-level graph projector.

LLaMo’s architecture is shown. It uses a graph neural network to encode a 2D molecular graph, converting the graph representation into tokens. These are fed, along with SMILES notation and an instruction, into a multi-level graph projector and then a large language model. This generates a response based on the instruction.

This figure shows the architecture of LLaMo. LLaMo uses a three-stage process to answer questions about molecules. First, a graph neural network encodes a 2D molecular graph (input). Second, a multi-level graph projector transforms the encoded graph into tokens understandable by the large language model. Third, the large language model generates an instruction-following response based on the input SMILES string, graph tokens, and the input question.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the LLaMo model, showing the three main components: a graph neural network (GNN) that encodes the 2D molecular graph, a multi-level graph projector that transforms the GNN output into tokens understandable by the language model, and a large language model that generates the final instruction-following response. The input includes SMILES notation, graph tokens and an instruction, and the output is the generated text.

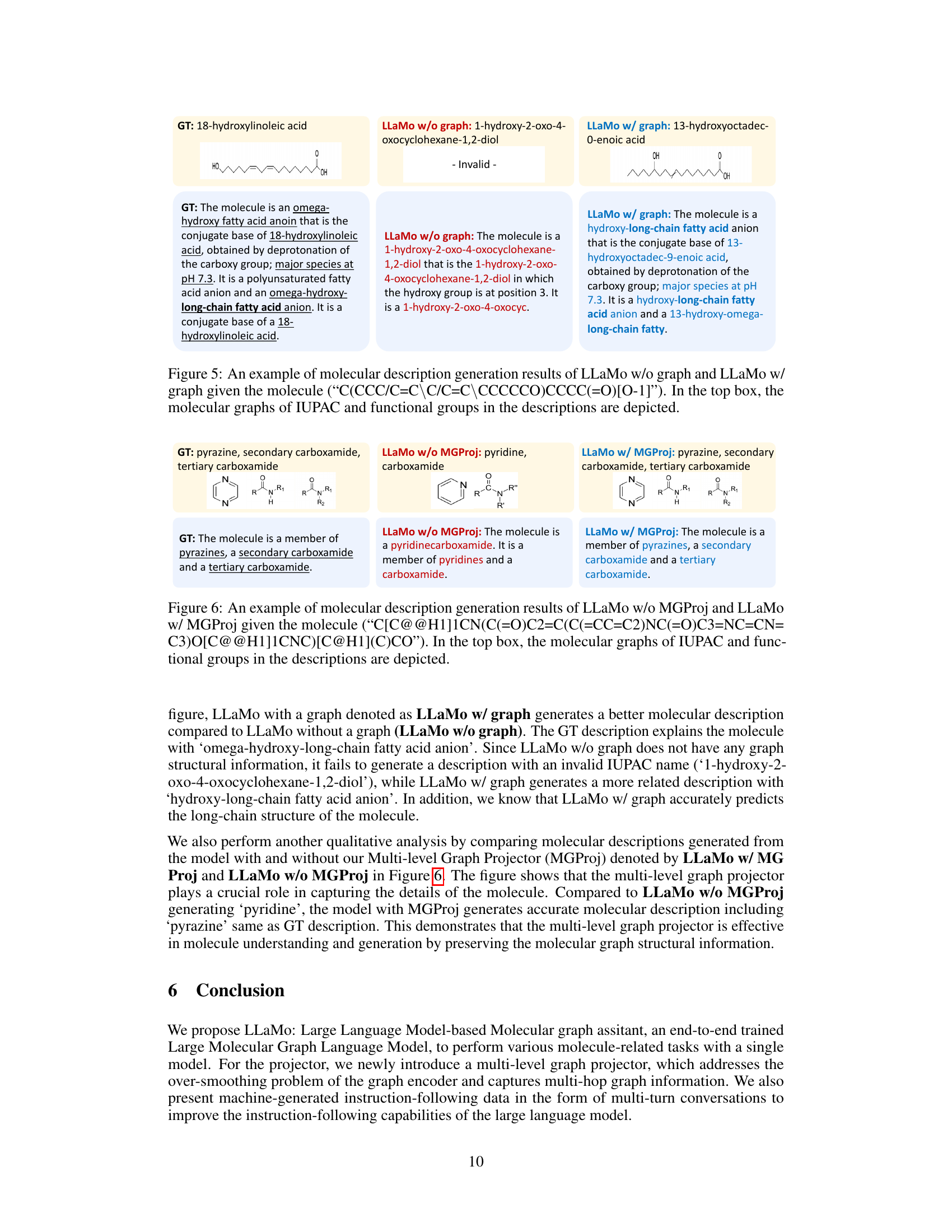

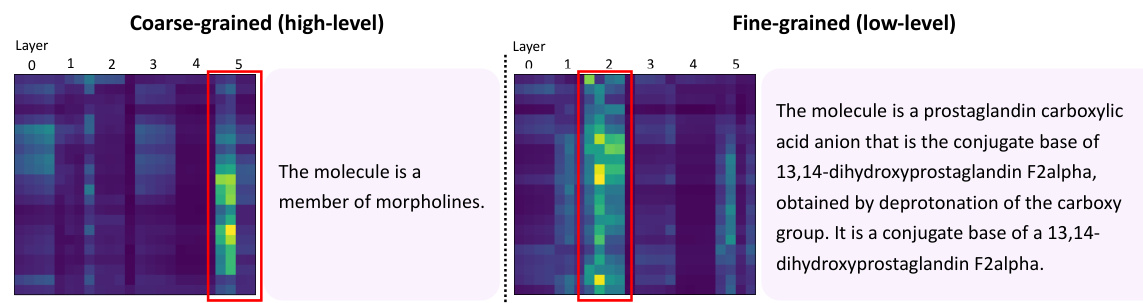

This figure visualizes the attention maps generated by the model when producing different types of captions (coarse-grained and fine-grained). The heatmaps show which parts of the molecular graph representation the model focuses on when generating each caption type. The left panel shows the attention for coarse-grained captions (high-level features), and the right panel for fine-grained captions (low-level features). The visualization demonstrates that the model uses different parts of the graph depending on the desired level of detail in the caption.

This figure illustrates the architecture of LLaMo, a large language model-based molecular graph assistant. It shows the three main components: a graph neural network (GNN) that encodes a 2D molecular graph into node representations; a multi-level graph projector that transforms these representations into graph tokens usable by the language model; and a large language model that generates a response based on the graph tokens, SMILES input, and the given instruction. The multi-level projector is key to bridging the gap between graph and language modalities.

The figure shows the architecture of LLaMo, a large language model-based molecular graph assistant. It consists of three main components: a graph neural network (GNN) that encodes a 2D molecular graph as input, a multi-level graph projector that transforms the GNN’s output into a sequence of molecular graph tokens suitable for the language model, and a large language model (LLM) that generates the final instruction-following response. The input to the system is a combination of the 2D molecular graph, its SMILES representation (a 1D string representation of the molecule), and an instruction (text).

LLaMo is composed of three main components: a graph neural network (GNN) that encodes the input molecular graph, a multi-level graph projector that transforms the graph representation into tokens understandable by the language model, and a large language model (LLM) that generates the final response based on the graph tokens and the input instruction (e.g., a SMILES string and a question about the molecule). The multi-level graph projector is a crucial component that bridges the gap between the graph and language modalities.

LLaMo’s architecture is shown, illustrating the flow of information. A 2D molecular graph and its SMILES representation are input to a graph neural network (GNN). The multi-level graph projector transforms the GNN’s output into molecular graph tokens, which are then fed into a large language model along with an instruction. The language model generates a response based on this combined input.

This figure visualizes the node representations learned by a graph neural network (GNN) with varying numbers of layers (1, 2, 4, and 5). Each subfigure shows the node representations of the same molecular graph. The key observation is that as the number of layers in the GNN increases, the node representations tend to become more similar, eventually collapsing into almost identical representations in the higher-layer GNNs. This phenomenon, known as over-smoothing, is a significant challenge in graph neural networks, limiting their ability to capture fine-grained information. This illustrates the limitations of simply using the output of the final GNN layer for downstream tasks.

The figure illustrates the architecture of LLaMo, a large language model-based molecular graph assistant. LLaMo takes three types of input: a 2D molecular graph, a SMILES string (a linear representation of the molecule), and an instruction (a natural language query). The molecular graph is processed by a graph neural network (GNN) that outputs node representations. These are then transformed into graph tokens via a multi-level graph projector that incorporates information from multiple layers of the GNN. These tokens, along with the SMILES and instruction, are provided to a large language model, which then generates a response. The multi-level graph projector is key to bridging the gap between the graph and language modalities.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of LLaMo, which seamlessly integrates a molecular graph encoder, a multi-level graph projector, and a large language model to generate instruction-following responses. The process begins by encoding a 2D molecular graph using a graph neural network. The multi-level graph projector then transforms the encoded graph into graph tokens, which are compatible with the large language model. Finally, the large language model generates a response based on the input SMILES string, graph tokens, and instruction.

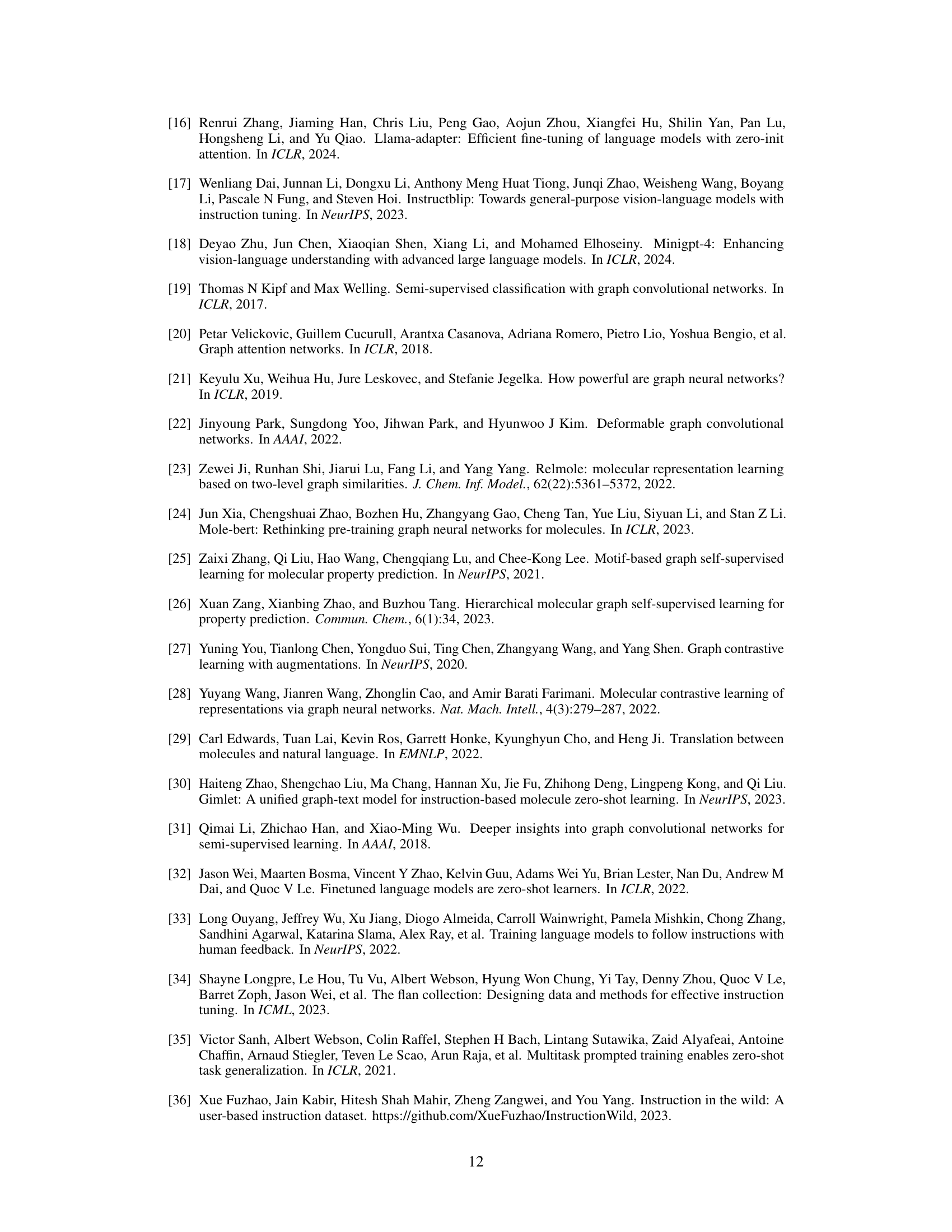

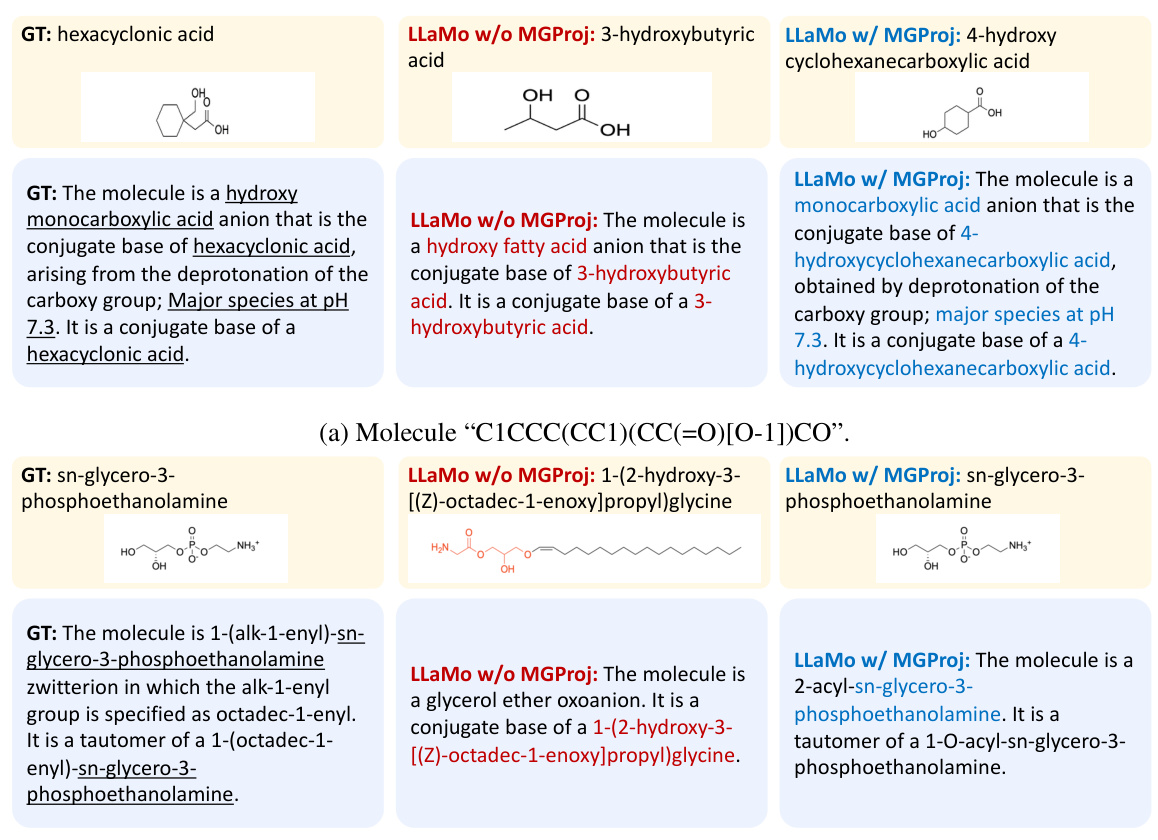

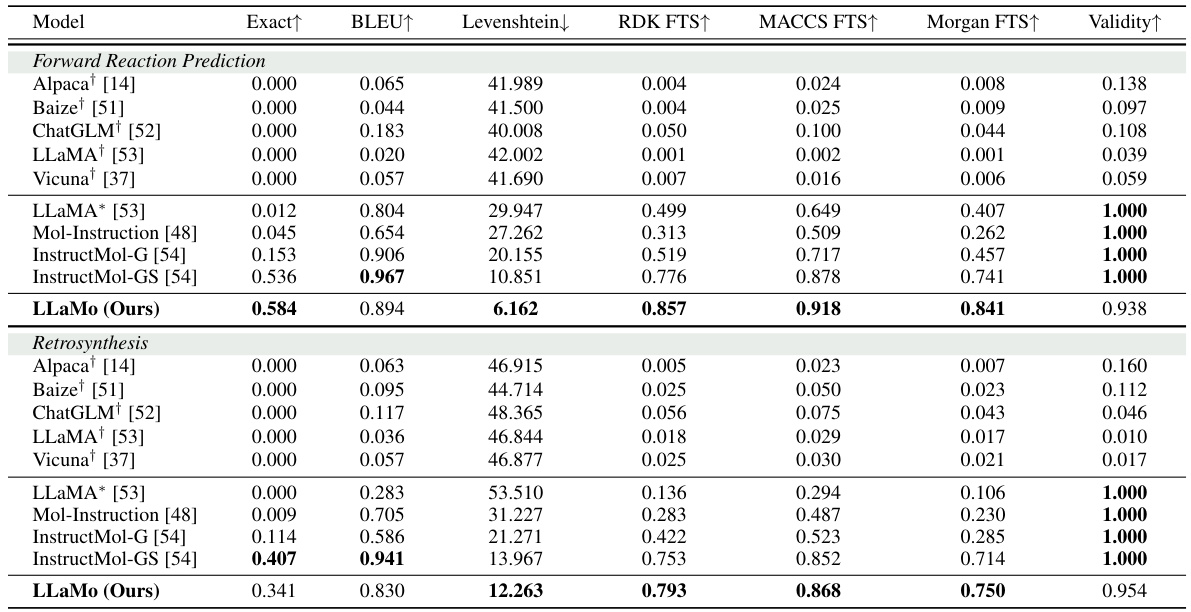

More on tables

This table presents the performance of various specialist models on two molecule captioning datasets (PubChem324k and ChEBI-20) and IUPAC name prediction. The models are evaluated using BLEU and METEOR scores for captioning and METEOR for IUPAC name prediction. The ‘Training type’ column indicates whether full fine-tuning or a low-rank adaptation (LORA) was used. The table allows for comparison of different models’ performance across different datasets and training methods. It highlights the performance of LLaMo in comparison to other state-of-the-art models.

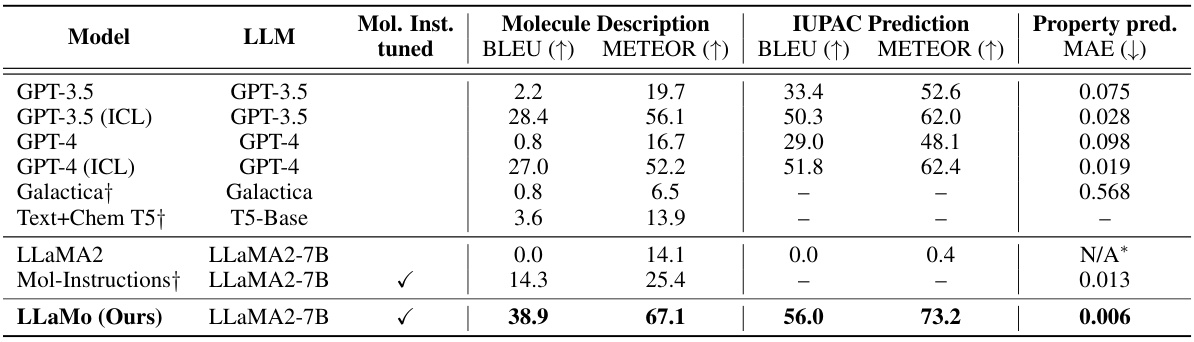

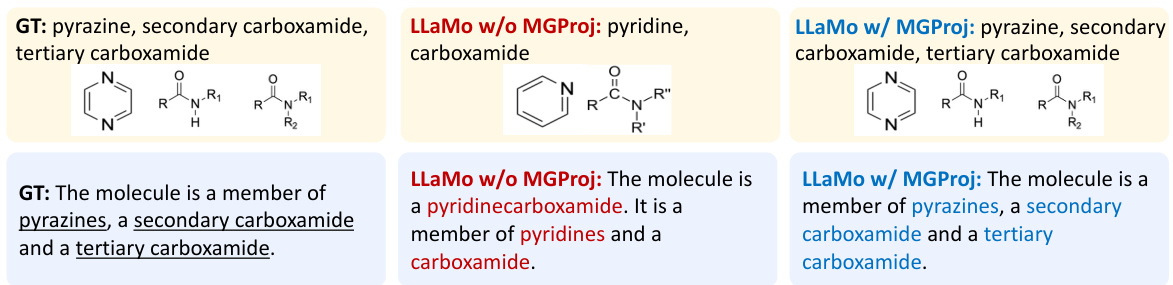

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different graph projectors used in the LLaMo model. It shows the BLEU and METEOR scores for molecule description and IUPAC prediction tasks, along with the MAE for property prediction. The projectors compared include a baseline with no graph, MLPs using different levels of node representation, a resampler, and the proposed multi-level graph projector (MGProj) with and without motif information. The results demonstrate the superiority of the MGProj in capturing multi-level graph structure, leading to improved performance.

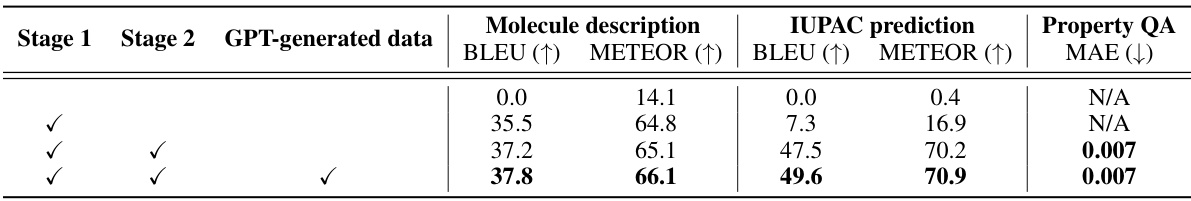

This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to evaluate the impact of different training stages and the use of GPT-generated instruction tuning data on the performance of the LLaMo model. It shows the BLEU and METEOR scores for molecule description generation, IUPAC prediction, and the MAE for property prediction. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the two-stage training pipeline and the inclusion of GPT-generated data in improving the model’s performance across various tasks.

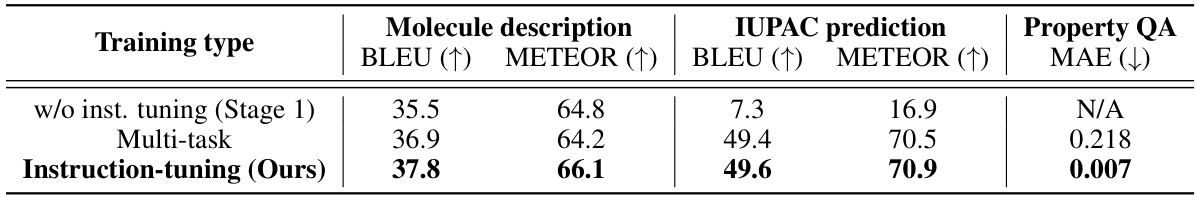

This table compares the performance of three different training methods on three tasks: molecule description generation, IUPAC prediction, and property prediction. The methods are: training without instruction tuning (only Stage 1), multi-task learning, and the authors’ proposed instruction-tuning method. The results show that the instruction-tuning method achieves the best performance across all three tasks, demonstrating the effectiveness of instruction tuning for these molecular tasks.

This table compares the performance of various generalist language models on three molecular tasks: generating descriptions of molecules, predicting IUPAC names, and predicting properties. The models are evaluated using metrics such as BLEU, METEOR, and MAE. The table includes both models fine-tuned with molecular instructions and those without, highlighting the impact of instruction tuning on performance.

This table presents the performance comparison of various generalist models (including the proposed LLaMo) across three tasks: molecule description generation, IUPAC name prediction, and property prediction. The performance is measured using BLEU, METEOR, and MAE metrics, reflecting the model’s ability to generate descriptions, predict IUPAC names, and predict molecular properties, respectively. The table also highlights whether the models were fine-tuned using molecular instruction data and notes the limitations of LLaMA2 in certain tasks.

This table compares the performance of various large language models (LLMs) on three tasks related to molecular understanding: molecule description generation, IUPAC name prediction, and property prediction. It shows the BLEU and METEOR scores (higher is better) for description and IUPAC prediction, and MAE (lower is better) for property prediction. The models are categorized as either generalist (handling all three tasks) or molecular instruction-tuned (specifically trained for molecular tasks). The table helps to demonstrate LLaMo’s improved performance compared to other LLMs.

This table compares the performance of various large language models (LLMs) on three tasks related to molecular understanding: molecule description generation, IUPAC name prediction, and property prediction. It contrasts the performance of generalist models (trained on multiple tasks) and those that were specifically fine-tuned for molecular instruction tasks, showing BLEU, METEOR, and MAE scores for each model.

Full paper#