↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Vision transformers (ViTs) have become dominant in image processing but lack mathematical interpretability. The CRATE model was designed as an interpretable alternative, but its scalability has been limited. This paper introduces CRATE-a, a modified version of CRATE with minimal architectural adjustments, demonstrating significant improvements in scalability and performance.

CRATE-a addresses the scalability issues through strategic modifications to the sparse coding block, including an overparameterized design and decoupled dictionaries. Furthermore, it incorporates a residual connection to improve performance. These modifications are shown to enhance both the scalability and interpretability of the model, resulting in improved ImageNet accuracy and superior unsupervised object segmentation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers seeking to improve the scalability and interpretability of vision transformers. It demonstrates a novel approach to scaling white-box transformers, achieving state-of-the-art results on ImageNet while maintaining interpretability, thus opening exciting new avenues for future research in both vision and language models. The work challenges existing limitations and provides a practical method for building more efficient and interpretable models.

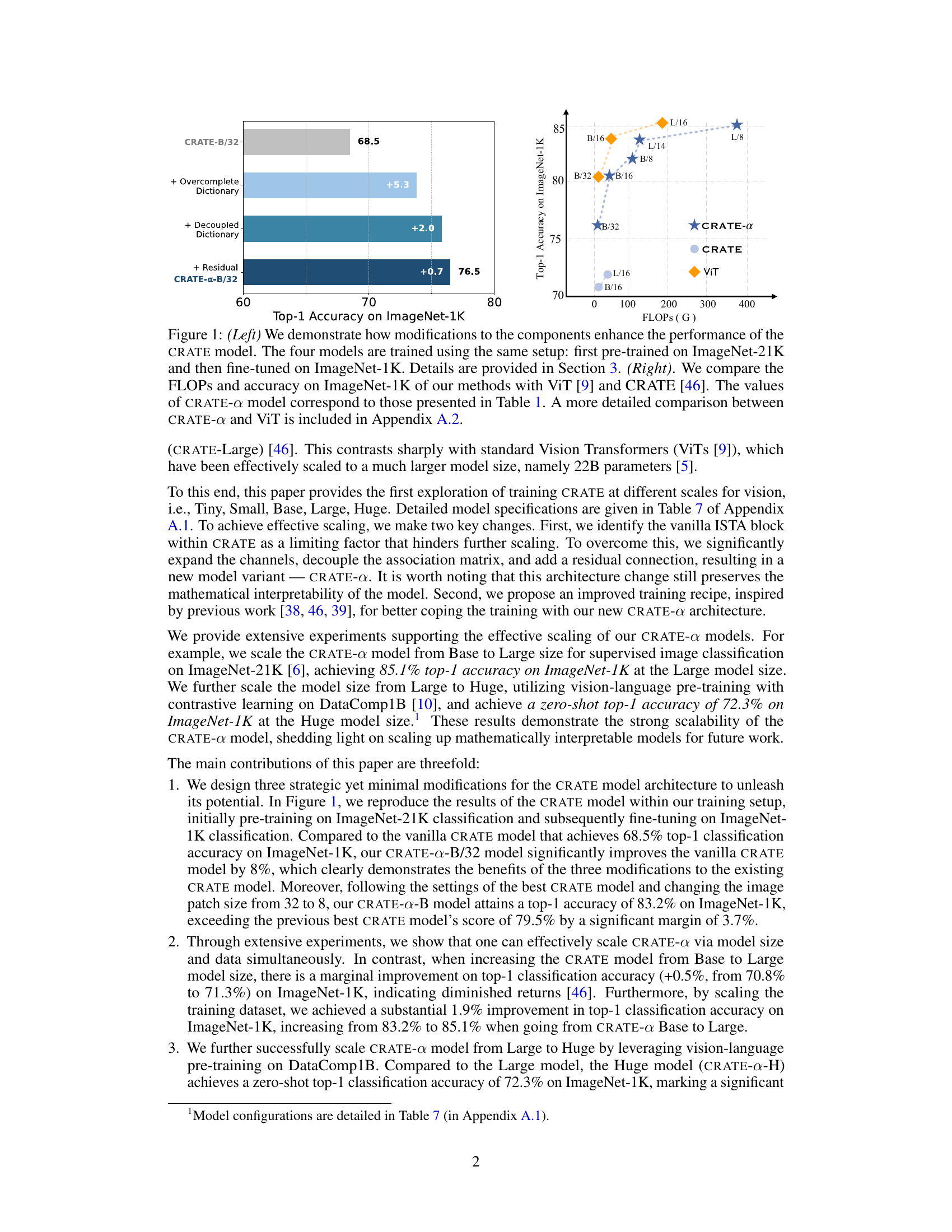

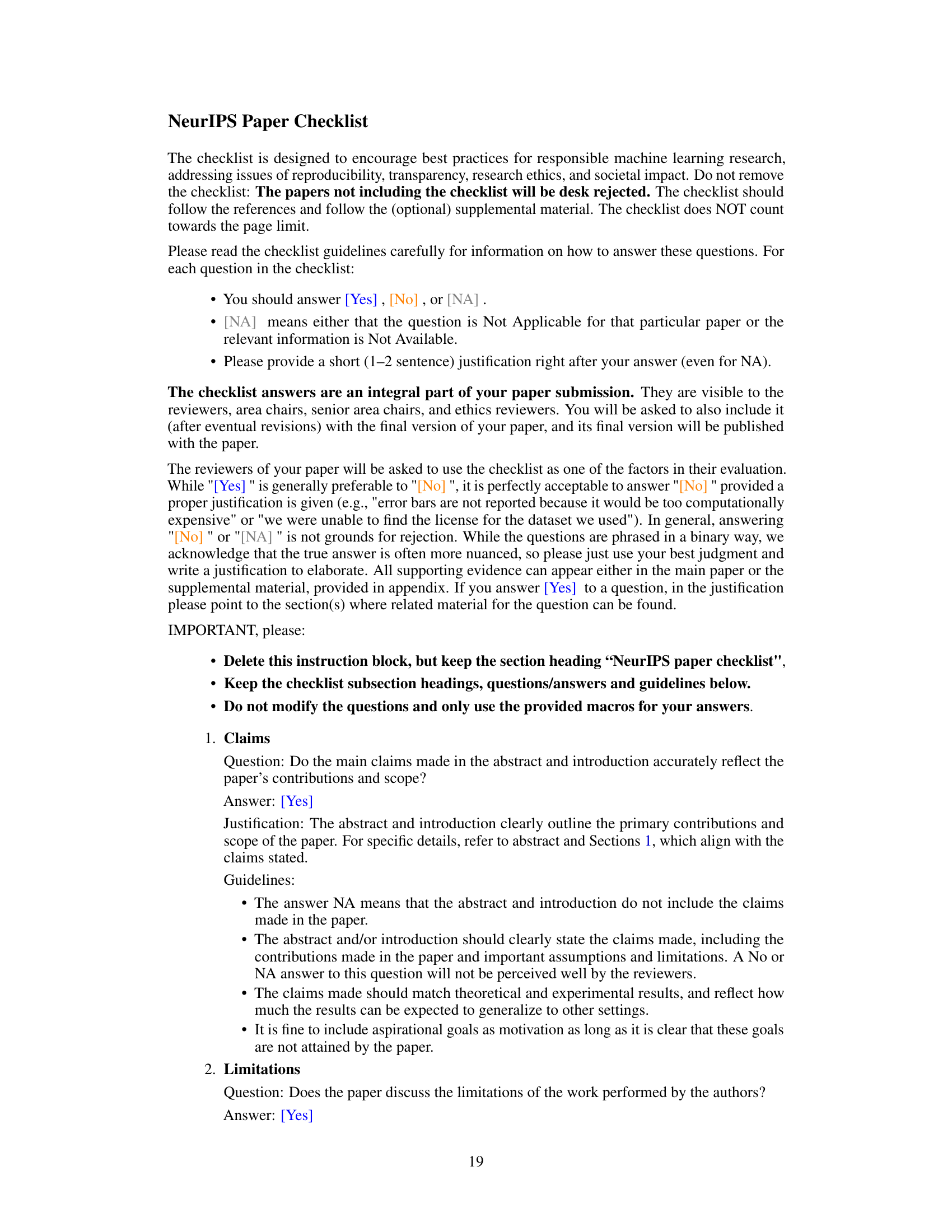

Visual Insights#

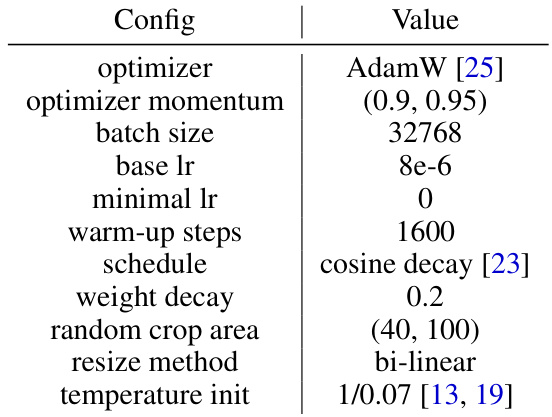

The left panel shows the performance gains obtained by sequentially adding three modifications to the CRATE model (overcomplete dictionary, decoupled dictionary, and residual connection). All models were trained using ImageNet-21K for pre-training and ImageNet-1K for fine-tuning. The right panel compares the computational cost (FLOPs) and ImageNet-1K accuracy of the proposed CRATE-a models against ViT and the original CRATE model. CRATE-a achieves higher accuracy with comparable FLOPs.

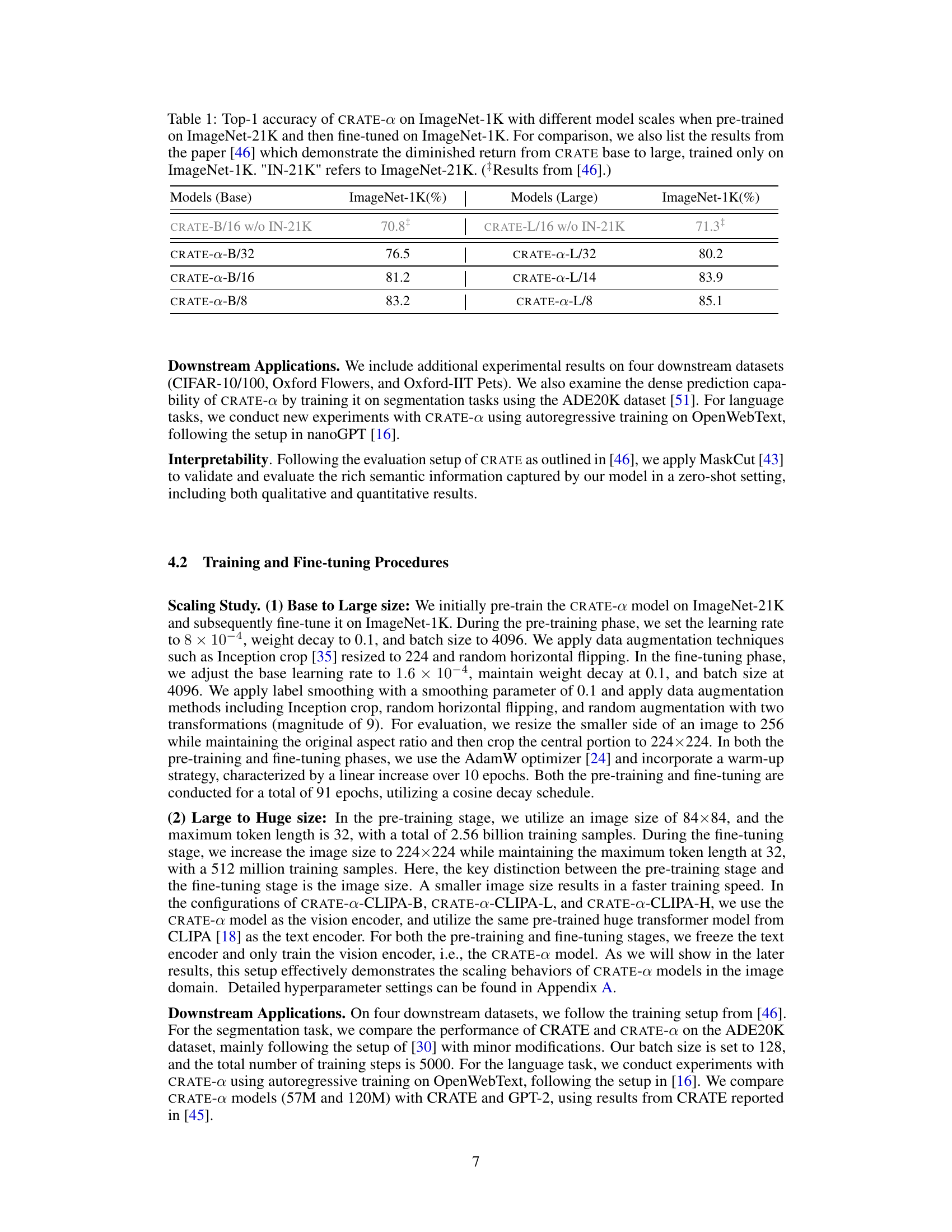

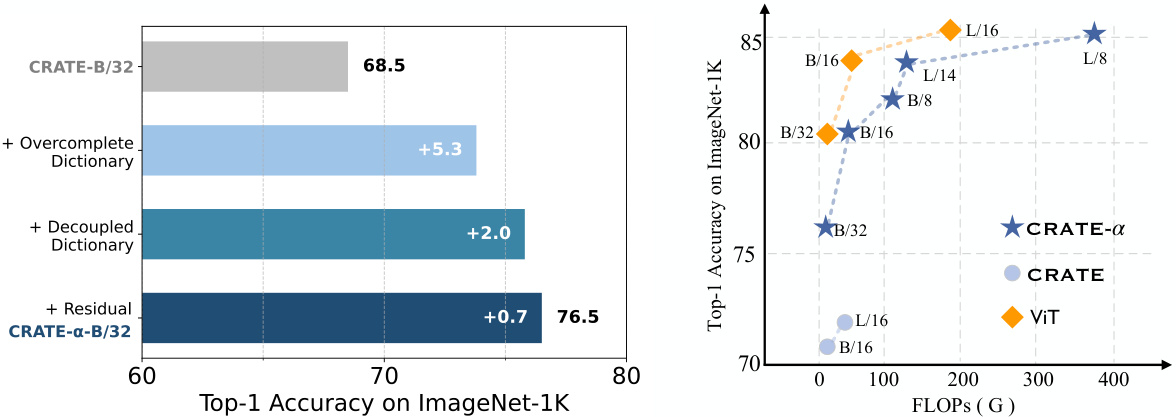

This table presents the top-1 accuracy of the CRATE-a model on the ImageNet-1K dataset for various model sizes (Base and Large). The models were pre-trained on ImageNet-21K before fine-tuning on ImageNet-1K. The table also includes results from the original CRATE paper [46] for comparison, highlighting the improved scalability of CRATE-a.

In-depth insights#

CRATE’s Scalability#

The research explores the scalability of the CRATE (Coding RATE Transformer) model, a white-box transformer architecture known for its interpretability. Initial experiments reveal that scaling vanilla CRATE models is challenging, unlike black-box transformers like ViT. The authors address this limitation by introducing CRATE-a, which incorporates modifications to the sparse coding block and a refined training recipe. CRATE-a demonstrates significantly improved scalability, outperforming previous CRATE models on ImageNet classification by a substantial margin. This is achieved while preserving, and potentially enhancing, the interpretability of the model through improvements in unsupervised object segmentation. The effective scaling of CRATE-a suggests a pathway for future development of mathematically interpretable models, enabling a deeper understanding of the relationships between model size, data size, and performance while maintaining the benefit of explainability. The success of CRATE-a highlights the importance of careful architectural design and training strategies when scaling white-box models, providing a valuable contribution to the field of both explainable and scalable AI.

ISTA Block Enhancements#

The ISTA (Iterative Shrinkage-Thresholding Algorithm) block, a core component of the CRATE (Coding RATE Transformer) architecture, presents a unique opportunity for enhancement. The original CRATE model utilizes a complete dictionary within its ISTA block, limiting its expressive power and potentially hindering scalability. Overparameterizing the sparse coding block by employing an overcomplete dictionary is crucial to enhance its performance. This modification allows the model to learn more expressive and potentially higher-quality sparse representations. Decoupling the dictionary further improves the model’s ability to learn complex relationships between features. Finally, the addition of a residual connection helps to preserve information that might otherwise be lost during the sparsification process, leading to improved performance and robustness. These three key improvements (overparameterization, decoupling, and residual connections) are not merely incremental changes; they address fundamental limitations in the original ISTA block, demonstrating a thoughtful and effective approach to scaling and enhancing the CRATE architecture.

Interpretability Gains#

The paper focuses on scaling white-box transformers, specifically the CRATE architecture, while maintaining or even enhancing interpretability. CRATE’s inherent mathematical interpretability, stemming from its design based on unrolled optimization and sparse rate reduction, is a key advantage. The authors demonstrate that scaling CRATE-a, an improved version of CRATE, to larger models and datasets not only improves accuracy but also preserves and potentially enhances interpretability. This is shown through improved quality of unsupervised object segmentation when using token representations from the larger CRATE-a models. This suggests that the architectural modifications and training techniques used in CRATE-a support larger-scale training without sacrificing the desirable interpretability properties of the original CRATE model. The increased interpretability, coupled with improved accuracy at scale, is a significant contribution, contrasting with many black-box vision transformers which prioritize performance over explainability. The paper highlights this as a key advantage of the white-box approach, particularly regarding the direct visualization of learned features, showcasing a clear path towards more understandable and trustworthy AI models.

Downstream Tasks#

The section on “Downstream Tasks” would ideally delve into the performance of the CRATE-a model on various applications beyond the primary ImageNet classification task. This is crucial to demonstrate the model’s generalizability and practical value. Key aspects would include the specific downstream datasets used (e.g., object detection, segmentation, other image classification benchmarks). The results should be presented in comparison to existing state-of-the-art models on those tasks, highlighting any performance gains or improvements achieved by CRATE-a. A thorough analysis should explore whether CRATE-a’s inherent interpretability translates to improved performance or insights in these downstream applications. Discussions on challenges encountered when applying the model to diverse tasks and any necessary modifications or fine-tuning strategies would further enhance the analysis. Finally, any insights gained about the relationship between model size, interpretability and downstream task performance should be carefully examined and discussed. This comprehensive evaluation will establish the broader applicability and impact of the proposed CRATE-a architecture.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending CRATE-a’s scalability to even larger models and datasets is crucial, potentially through techniques like model parallelism and efficient data augmentation strategies. Investigating the impact of different architectural modifications on the balance between model interpretability and performance is also warranted. Further exploration into downstream applications beyond image classification and segmentation—such as object detection, video understanding, and multimodal tasks—would validate the model’s versatility. Finally, a deep dive into theoretical analysis of CRATE-a’s convergence properties and its relationship to sparse representation learning could provide a stronger mathematical foundation, and ultimately guide future architectural designs for highly interpretable and efficient vision transformers.

More visual insights#

More on figures

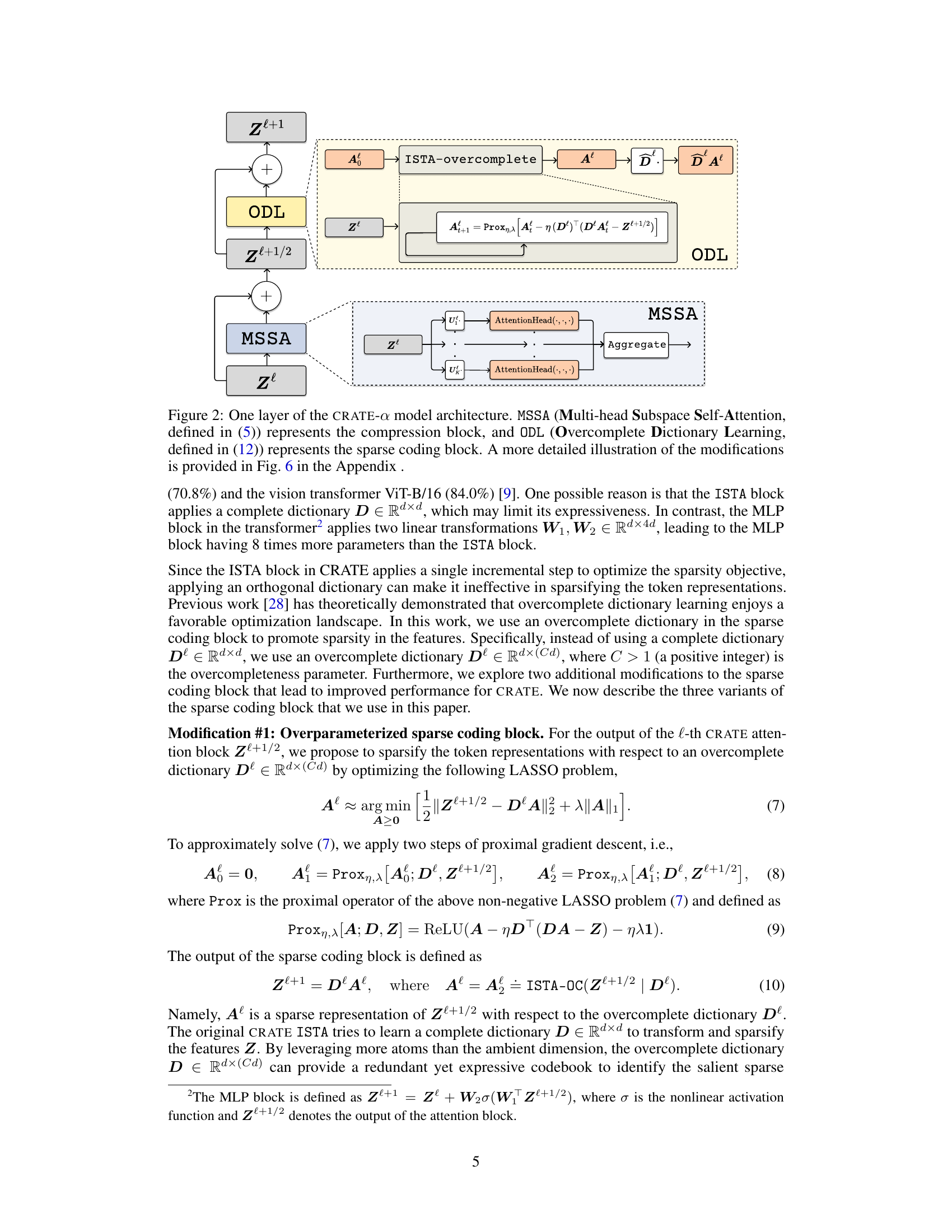

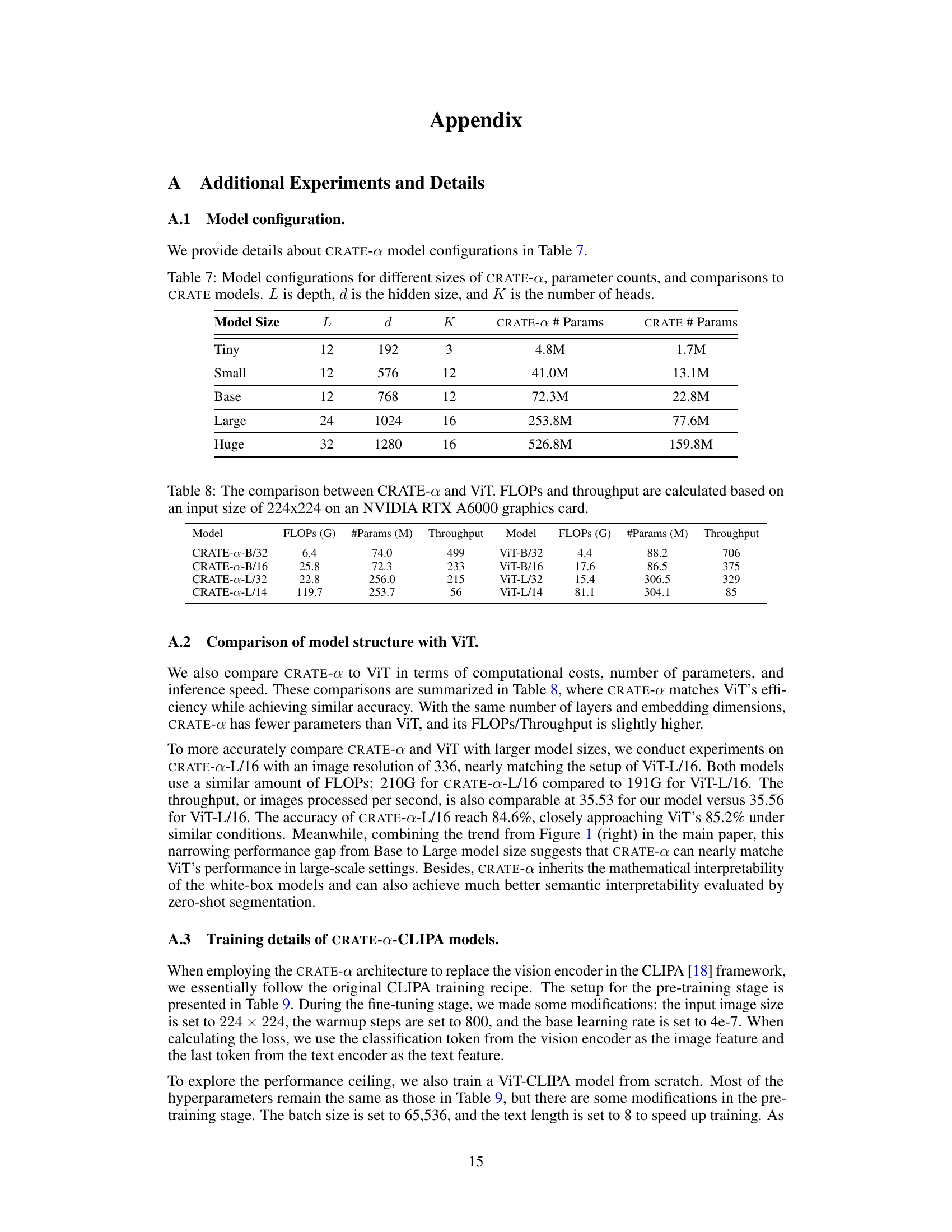

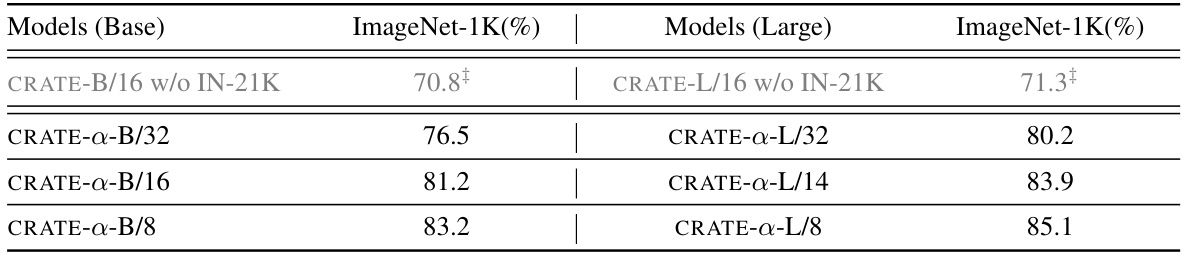

This figure shows a detailed architecture of one layer in the CRATE-a model. It highlights the two main blocks: the Multi-head Subspace Self-Attention (MSSA) block for compression and the Overcomplete Dictionary Learning (ODL) block for sparse coding. The ODL block incorporates three key modifications compared to the original CRATE model: an overparameterized sparse coding block, a decoupled dictionary, and a residual connection. These modifications enhance the scalability and performance of the model.

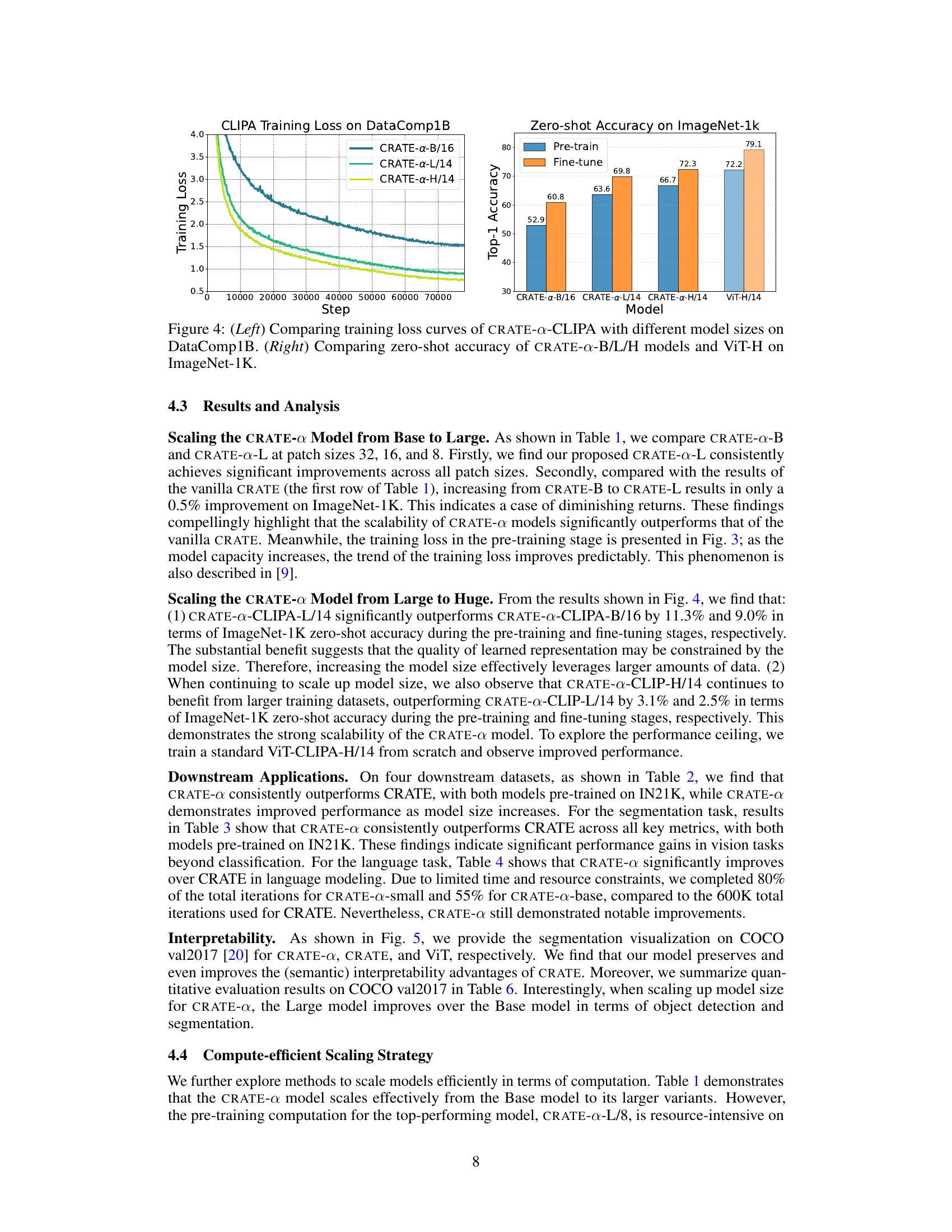

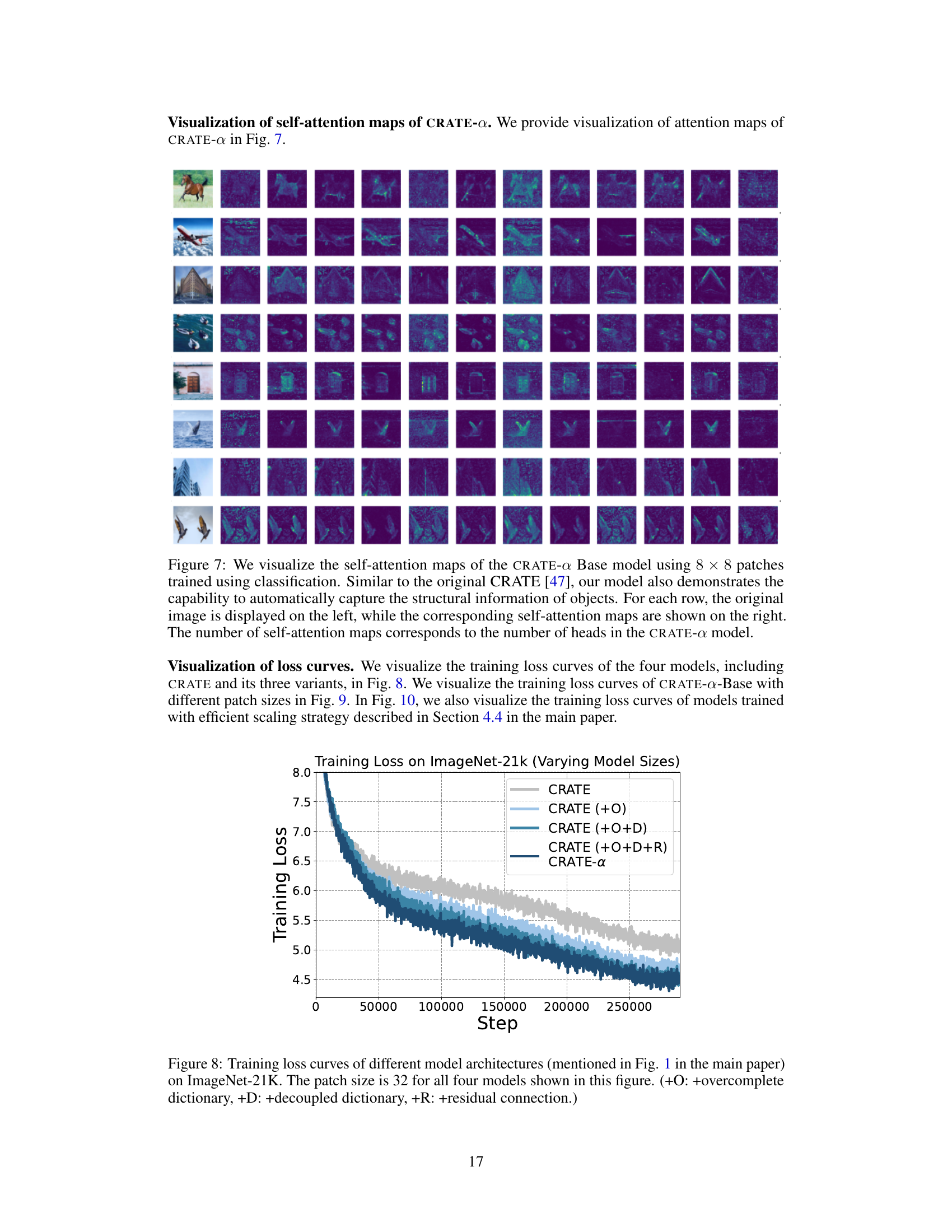

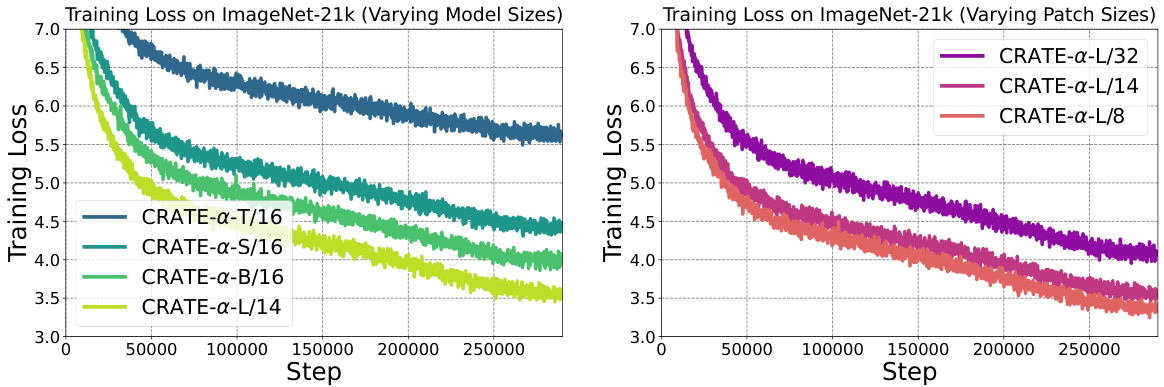

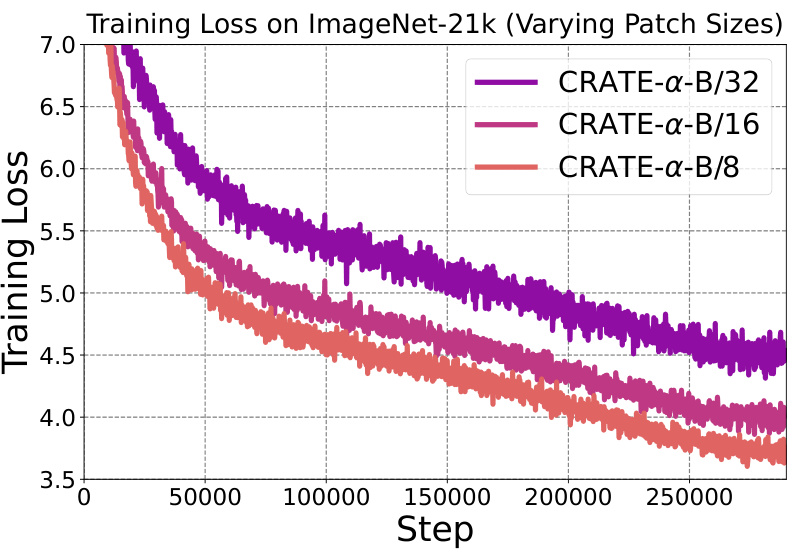

This figure displays the training loss curves for the CRATE-a model across various model sizes (left) and patch sizes (right) during training on the ImageNet-21K dataset. The left panel showcases how training loss changes as the model scales from Tiny to Huge. The right panel shows loss curves for the large CRATE-a model, highlighting the impact of altering patch size. Lower loss values generally indicate better model training progress.

This figure presents two graphs showing the results of scaling experiments of CRATE-a models using the CLIPA framework. The left graph displays the training loss curves for CRATE-a-B/16, CRATE-a-L/14, and CRATE-a-H/14 models trained on the DataComp1B dataset. The right graph shows the zero-shot accuracy on ImageNet-1k for the same CRATE-a models and ViT-H/14, comparing pre-training and fine-tuning results. The figure demonstrates the scalability and effectiveness of the CRATE-a architecture, highlighting the improvements in both training efficiency and zero-shot performance with increased model size.

This figure compares the zero-shot image segmentation performance of three different models: CRATE-a, CRATE, and ViT. The top row shows the results from the CRATE-a model, demonstrating accurate segmentation of objects in various images. The middle row presents the results from the CRATE model, which shows less accurate segmentation, particularly around object boundaries. The bottom row shows that the ViT model struggles to identify the main objects accurately in most of the images. This visualization highlights the superior zero-shot segmentation capabilities of CRATE-a compared to the other two models.

This figure shows a detailed architecture of one layer in the improved CRATE-a model. The architecture is comprised of two main blocks: a Multi-head Subspace Self-Attention (MSSA) block for compression and an Overcomplete Dictionary Learning (ODL) block for sparse coding. The ODL block incorporates three key modifications for improved scalability: overparameterization, decoupling of the dictionary, and the addition of a residual connection. These modifications are described further in Section 3 and Figure 6 of the Appendix.

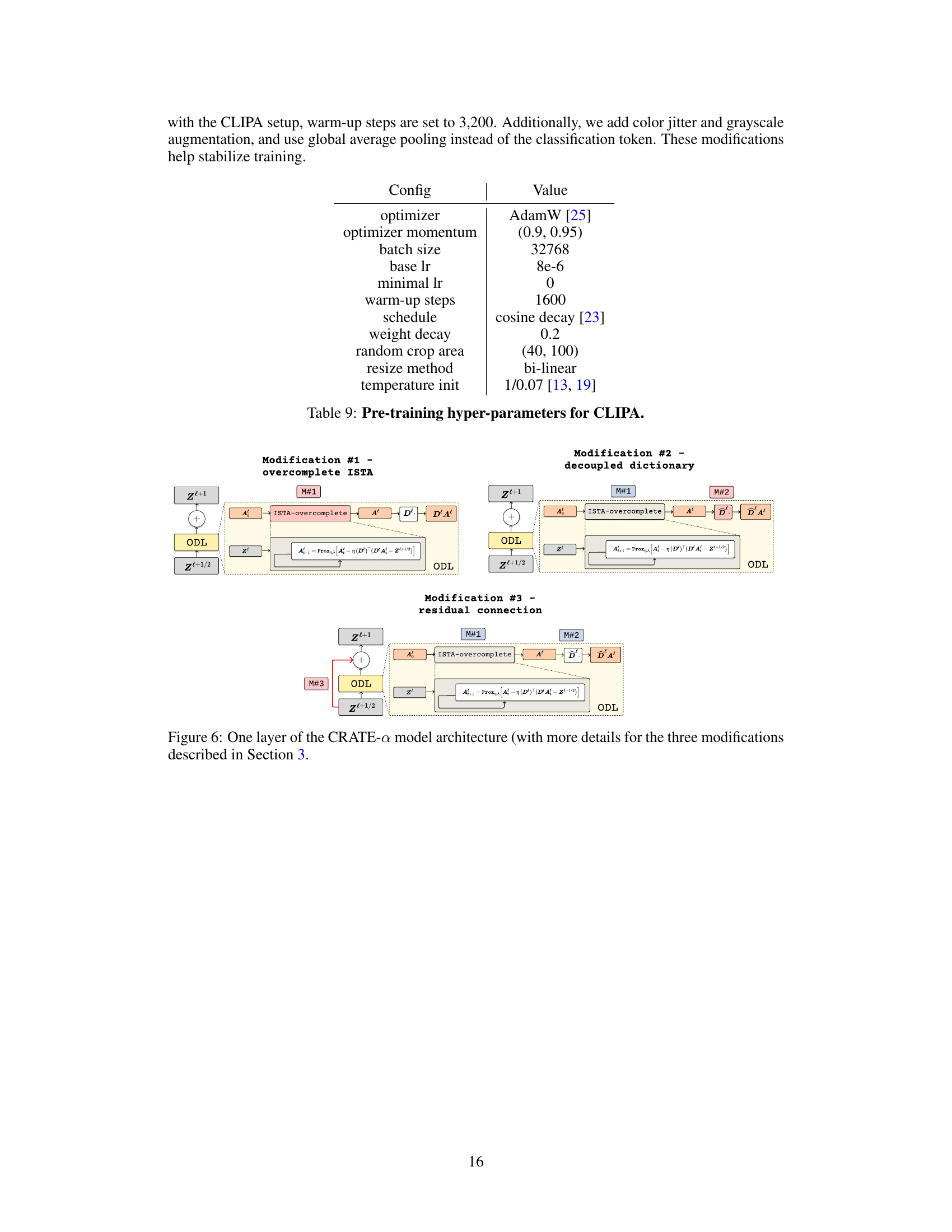

This figure visualizes the self-attention maps of the CRATE-a Base model. Each row shows an input image (left) and its corresponding self-attention maps (right). The number of self-attention maps equals the number of heads in the CRATE-a model. The figure highlights that the model successfully captures the structural information within the images, similarly to what was observed in the original CRATE model.

This figure shows the training loss curves for the CRATE-a model trained on the ImageNet-21K dataset. The left panel compares the training loss for different model sizes (Tiny, Small, Base, Large), while the right panel compares the training loss for different patch sizes (8, 14, 32) using the large CRATE-a model. The figure illustrates how training loss changes over steps for various configurations of the model, which impacts the model’s performance and scalability.

This figure displays training loss curves for the CRATE-a model trained on the ImageNet-21K dataset. The left panel shows how the training loss changes with different model sizes (Tiny, Small, Base, Large), demonstrating the model’s ability to scale effectively. The right panel illustrates how the training loss is impacted by changes in the image patch size used in the CRATE-a-Large model, offering insights into the model’s sensitivity to patch size.

This figure shows the training loss curves for three different model configurations using an efficient scaling strategy. Initially, a large CRATE-α model (L/32) is pre-trained. Then, this model’s weights are used to initialize smaller models (L/14 and L/8) that are fine-tuned. The graph illustrates how the training loss progresses for each of these three models, highlighting the efficiency of using this transfer learning approach for scaling.

More on tables

This table compares the performance of the original CRATE model and the improved CRATE-α model on four different datasets: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, Oxford Flowers-102, and Oxford-IIIT-Pets. It shows the top-1 accuracy achieved by each model variant (different model sizes and patch sizes) on each dataset, highlighting the performance improvement of CRATE-α over the original CRATE model.

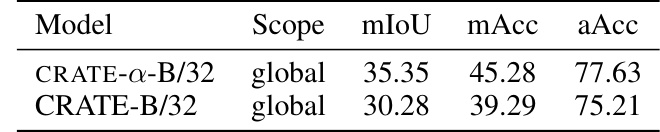

This table compares the performance of different CRATE models on a segmentation task. The models vary in their configurations, and the table shows the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), mean Accuracy (mAcc), and average Accuracy (aAcc) achieved by each model. It highlights the impact of model configuration on performance.

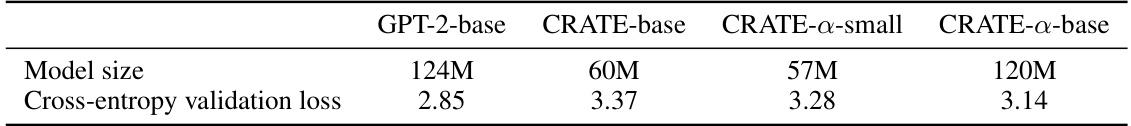

This table compares the performance of GPT-2-base, CRATE-base, CRATE-a-small, and CRATE-a-base models on the NLP task using the OpenWebText dataset. The comparison is based on the cross-entropy validation loss, which is a measure of how well the model predicts the next word in a sequence. Lower cross-entropy loss indicates better performance.

This table presents a comparison of the Top-1 accuracy achieved by different sized CRATE-a models on the ImageNet-1K dataset. The models were pre-trained on ImageNet-21K and then fine-tuned on ImageNet-1K. Results from the original CRATE paper are also included for comparison, highlighting the improved scalability of the CRATE-a architecture.

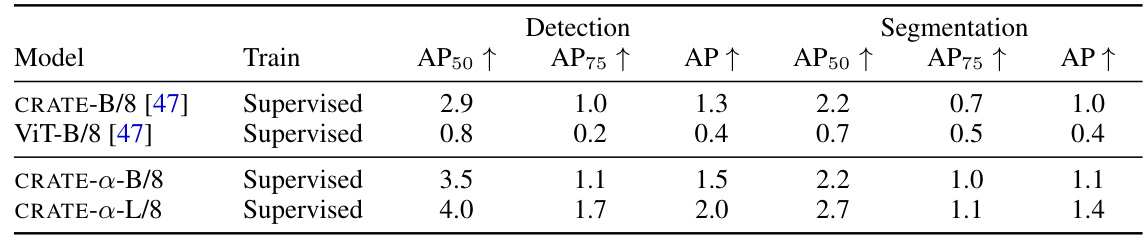

This table presents the results of object detection and fine-grained segmentation using MaskCut on the COCO val2017 dataset. It compares the performance of CRATE-a models of different sizes (base and large) against CRATE and ViT models, showcasing CRATE-a’s superior performance and scalability in both detection and segmentation tasks. The metrics used are average precision (AP) at different IoU thresholds (AP50 and AP75) and overall AP.

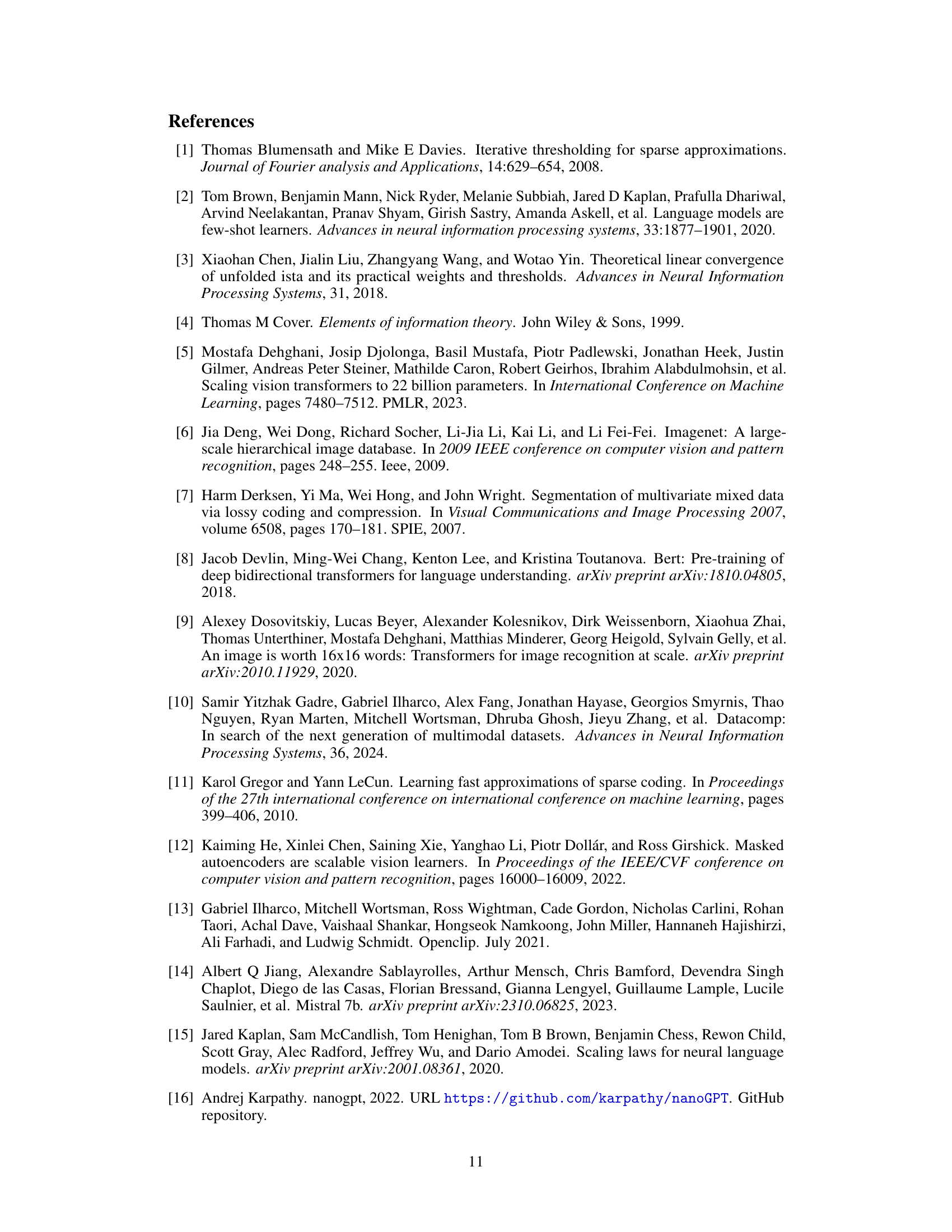

This table details the configurations of CRATE-a models of varying sizes (Tiny, Small, Base, Large, Huge). For each model size, it lists the depth (L), hidden size (d), number of heads (K), the number of parameters in the CRATE-α model, and the number of parameters in the original CRATE model for comparison. This allows for a direct comparison of the model complexity between the improved CRATE-α architecture and the original CRATE architecture across different scales.

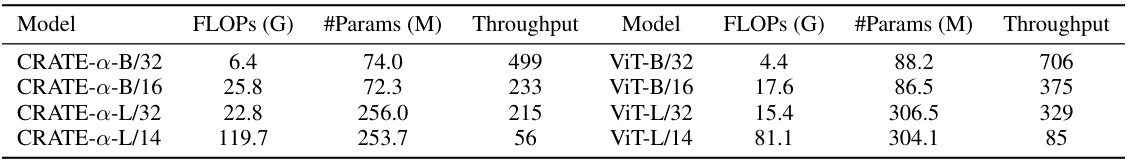

This table compares the performance of CRATE-a and ViT models with different sizes. It shows the FLOPs (floating point operations), the number of parameters, and the throughput (images processed per second) for each model. The comparison helps to illustrate the computational efficiency and speed of CRATE-a relative to ViT.

This table presents the ImageNet-1K Top-1 accuracy for various CRATE-a models with different sizes (Base and Large), trained using two different training strategies: pre-training on ImageNet-21K then fine-tuning on ImageNet-1K, and only training on ImageNet-1K (results from a previous study [46]). It demonstrates that CRATE-a models trained with ImageNet-21K pre-training significantly outperform those trained solely on ImageNet-1K, highlighting the improved scalability and performance of the CRATE-a architecture.

Full paper#