↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional Bayesian methods for change point detection in Hawkes processes suffer from low computational efficiency due to non-conjugate inference. This often hinders timely detection of crucial changes in dynamic systems. The non-conjugacy arises from the incompatibility between the likelihood function of the Hawkes process and commonly used priors.

This paper introduces CoBay-CPD, a novel method that solves the computational challenges by employing data augmentation. This technique introduces auxiliary latent variables to create a conditionally conjugate model, allowing for the derivation of an efficient and accurate Gibbs sampler for parameter inference. The proposed method demonstrates superior accuracy and efficiency compared to existing techniques, making it a valuable tool for real-time change point detection in various applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with Hawkes processes and change point detection. It offers a more efficient and accurate method compared to existing techniques, significantly advancing the field of dynamic event modeling. The conjugate Bayesian framework provides a powerful tool for various applications, opening avenues for improved analysis in finance, neuroscience, and social networks.

Visual Insights#

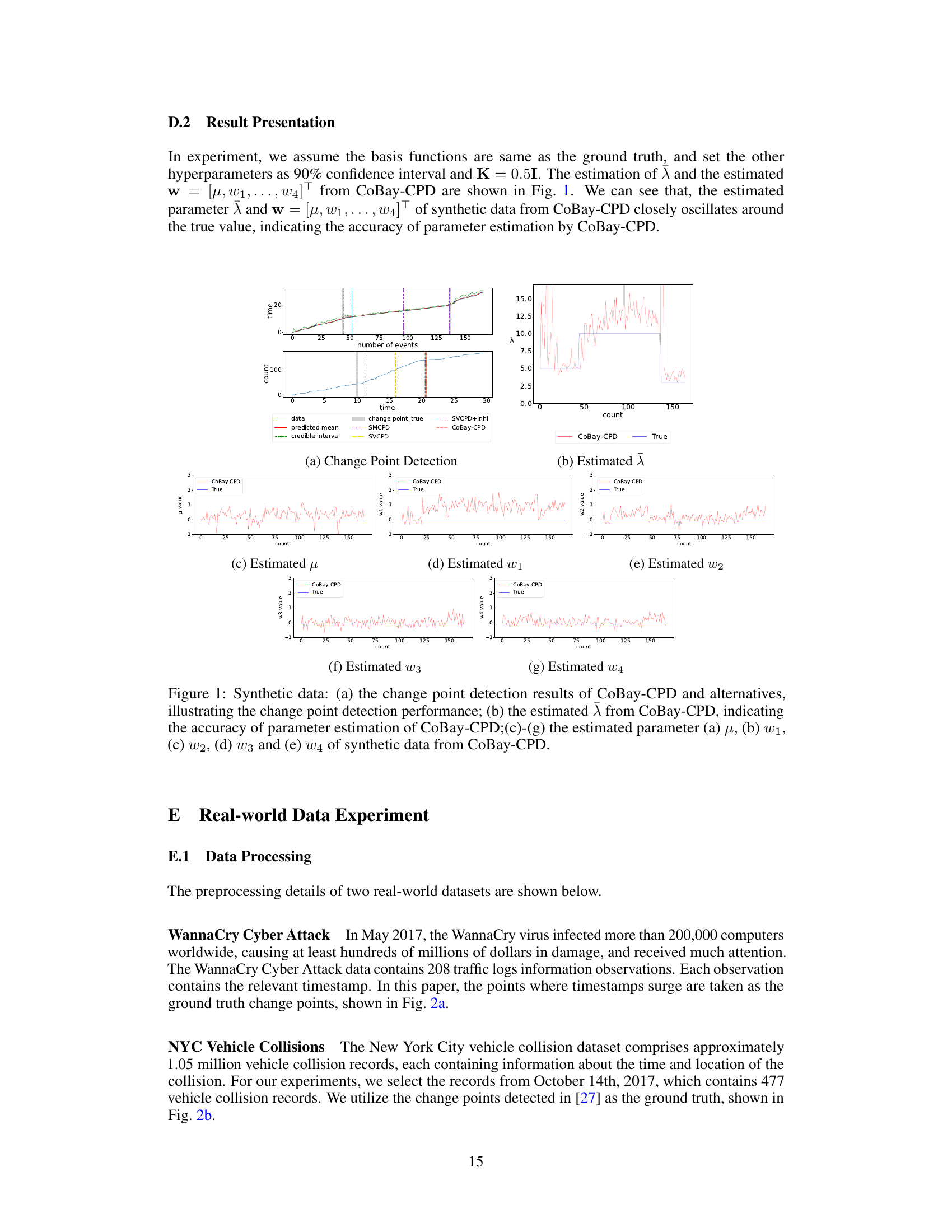

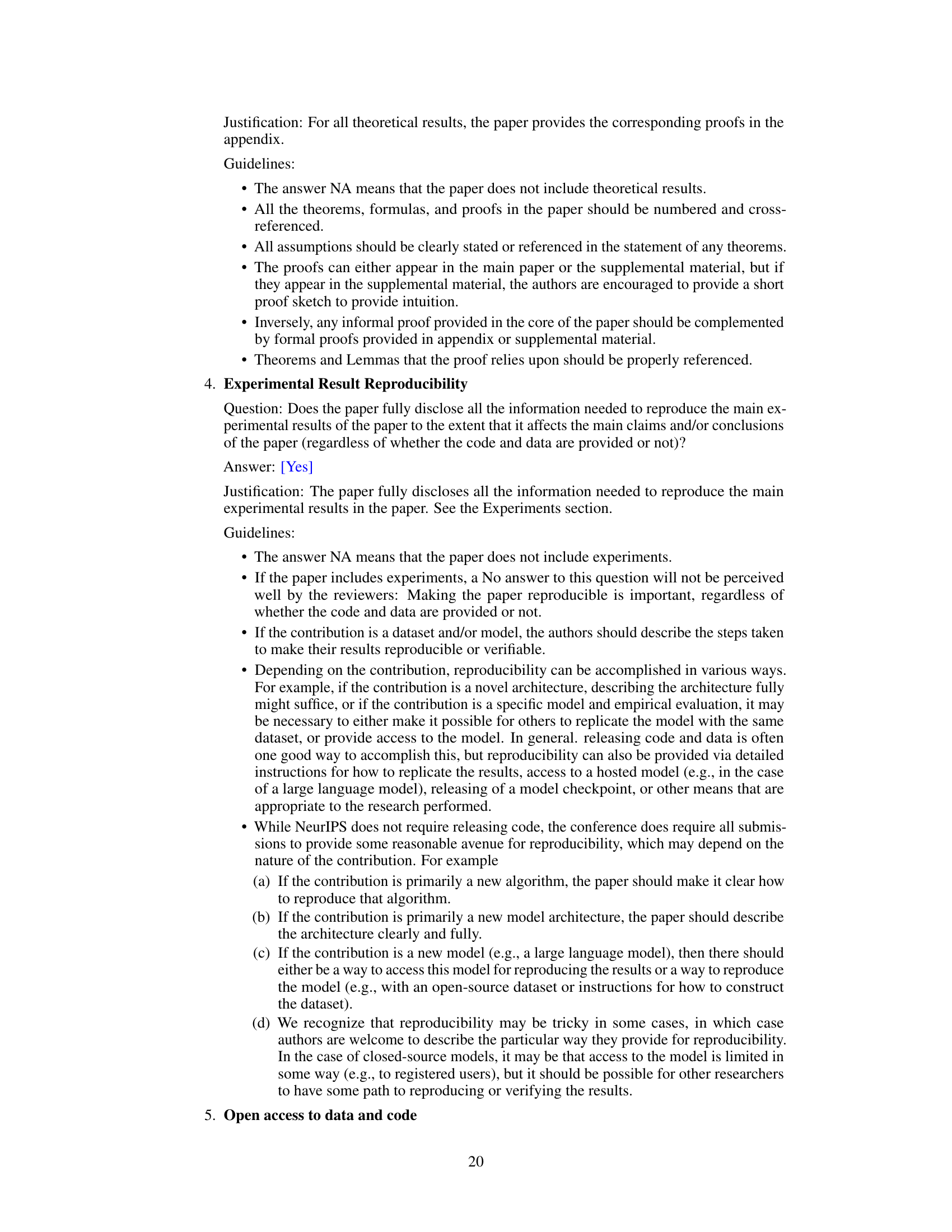

This figure shows the results of the synthetic data experiment. Subfigure (a) compares the change point detection performance of CoBay-CPD against several baseline methods by visualizing the detected change points along with the ground truth. Subfigure (b) displays the estimated intensity parameter (λ) obtained by CoBay-CPD, demonstrating its accuracy by closely matching the true values. Subfigures (c) through (g) illustrate the estimated model parameters (μ, w1, w2, w3, w4) obtained by CoBay-CPD, showing their fluctuations over time and their closeness to the true parameter values.

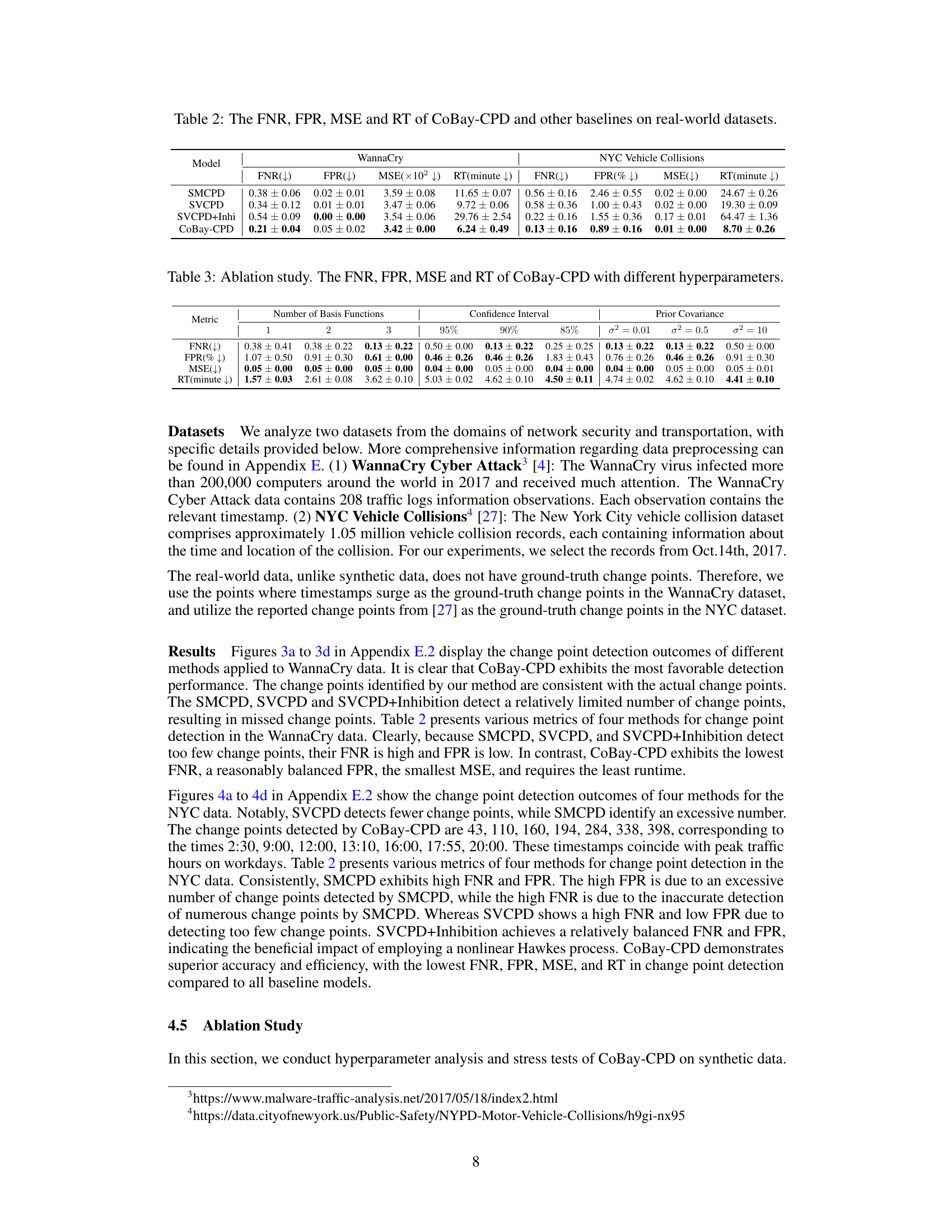

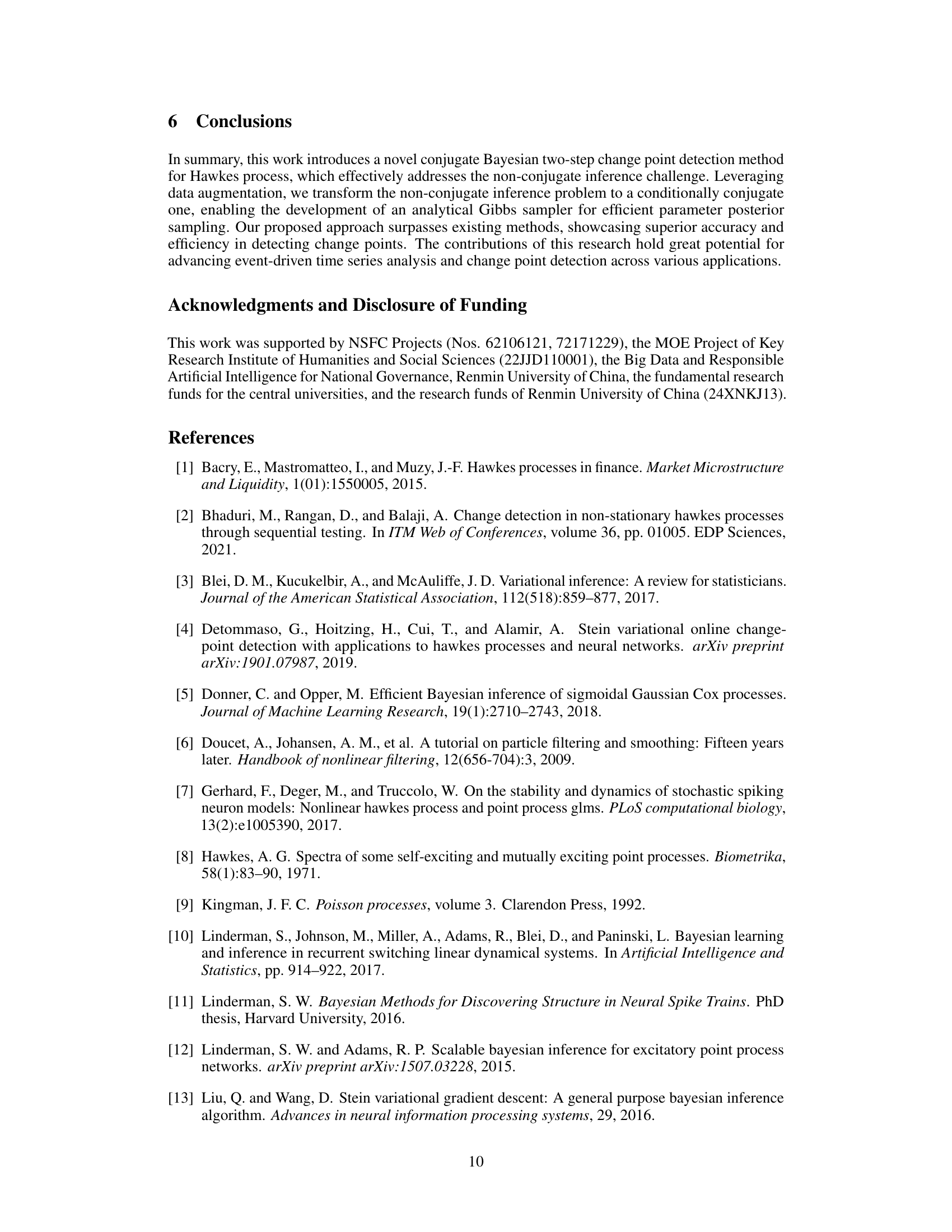

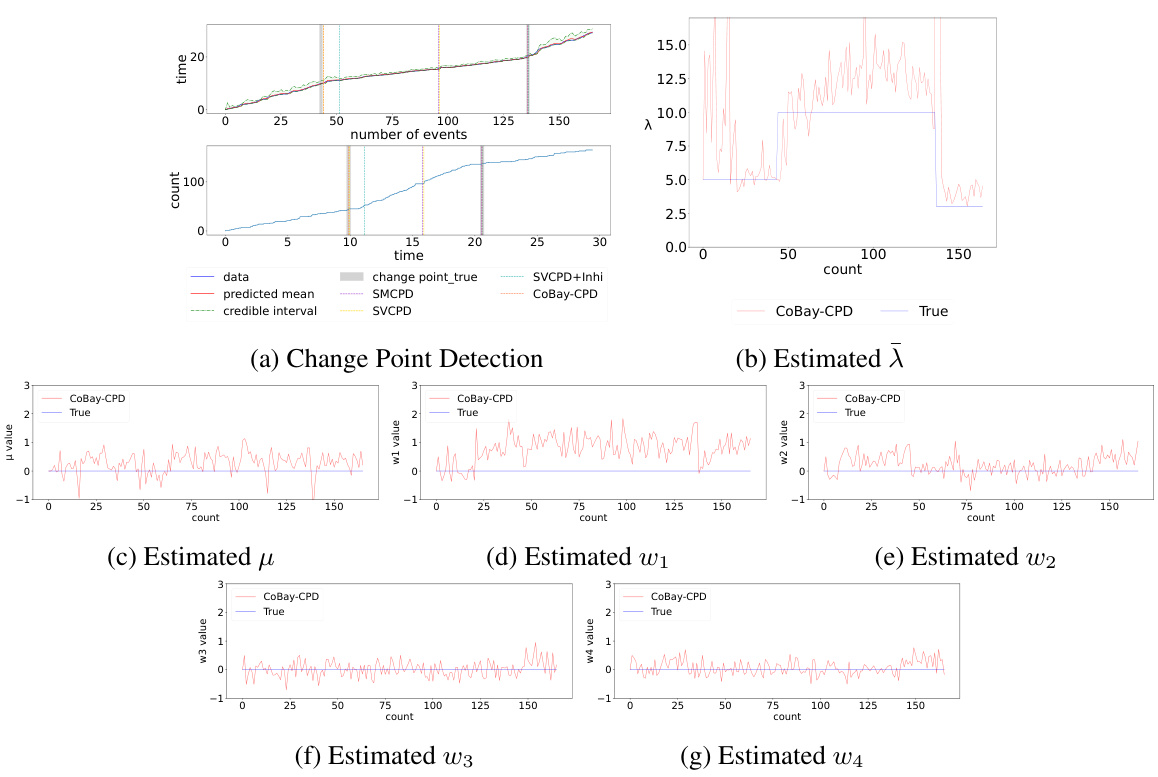

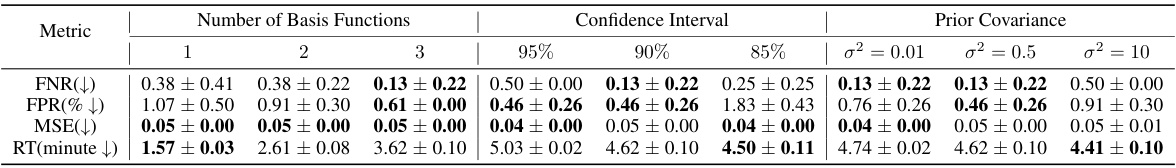

This table presents the results of a comparison between CoBay-CPD and several other baseline methods on a synthetic dataset. The metrics used to evaluate the methods are the False Negative Rate (FNR), which measures the percentage of missed change points; the False Positive Rate (FPR), which measures the percentage of incorrectly identified change points; the Mean Squared Error (MSE), which measures the accuracy of the next timestamp prediction; and the Running Time (RT), which measures the computational efficiency. Lower values are better for FNR, FPR, and MSE, and shorter times are better for RT. The table shows that CoBay-CPD achieves better performance than the other methods across all metrics.

In-depth insights#

Hawkes CPD Methods#

Hawkes process-based change point detection (CPD) methods are crucial for analyzing event data where the underlying dynamics shift over time. Bayesian approaches are particularly attractive due to their ability to incorporate prior knowledge and handle uncertainty, but traditional methods often struggle with the non-conjugacy between the Hawkes likelihood and common priors. This non-conjugacy leads to computationally expensive inference techniques like Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). Recent advancements leverage data augmentation techniques to address this limitation, enabling the derivation of efficient, closed-form solutions such as Gibbs samplers. These methods offer a significant advantage over MCMC-based approaches by substantially improving computational efficiency and accuracy. The choice of prior distributions and hyperparameter tuning remain important considerations for optimal performance in Bayesian Hawkes CPD. Future work may focus on extending these methods to handle multivariate Hawkes processes and incorporate more sophisticated models for the underlying change point process itself, addressing challenges such as multiple change points and varying change point magnitudes.

Bayesian Inference#

Bayesian inference offers a powerful framework for modeling uncertainty in the context of Hawkes processes. Traditional approaches often struggle with the non-conjugacy between the likelihood function and common priors, leading to computationally intensive methods like MCMC. However, the development of data augmentation techniques has significantly improved this situation. By introducing latent variables, we can transform the non-conjugate problem into a conditionally conjugate one, enabling closed-form solutions and greatly enhanced efficiency. This has significant implications for change point detection, as accurate and timely inference is crucial for successfully identifying shifts in the underlying dynamics of the Hawkes process. The use of conjugate Bayesian methods allows for more efficient parameter estimation and improved change-point detection, overcoming the limitations of frequentist approaches which often suffer from inaccurate parameter estimates due to data limitations or reliance on simplified models. Overall, Bayesian inference offers a compelling path toward robust and efficient modeling of dynamic point process data.

Data Augmentation#

The concept of data augmentation is a powerful technique used to enhance the performance of machine learning models, particularly when dealing with limited datasets. In the context of Bayesian inference for Hawkes processes, data augmentation addresses the challenge of non-conjugacy between the likelihood function and prior distributions. By introducing auxiliary latent variables, the method transforms a non-conjugate problem into a conditionally conjugate one. This clever manipulation enables the derivation of closed-form expressions, leading to computationally efficient and accurate Bayesian inference. The efficiency gains are significant, as traditional non-conjugate inference methods often rely on computationally expensive techniques like Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), which can be time-consuming, particularly for real-time applications like change point detection. The specific augmentation strategies employed may vary, but the core idea is to simplify the posterior inference by creating a more tractable joint distribution involving the latent variables. This allows for the development of efficient algorithms, such as Gibbs sampling, that can accurately estimate model parameters and improve the overall accuracy and efficiency of the change point detection process. Data augmentation is key to the CoBay-CPD method’s superior performance compared to baseline methods, highlighting its value in handling challenging inference problems within the context of dynamic event modeling.

CoBay-CPD Algorithm#

The hypothetical “CoBay-CPD Algorithm” likely centers on a conjugate Bayesian approach for change point detection in Hawkes processes. This suggests a significant methodological improvement over existing methods. The core innovation is probably the use of data augmentation, which transforms the non-conjugate likelihood into a conditionally conjugate form, enabling closed-form solutions via Gibbs sampling. This is crucial because traditional Bayesian methods for Hawkes process CPD often rely on computationally expensive techniques like MCMC. CoBay-CPD’s efficiency stems from its analytical Gibbs sampler, allowing for faster and more accurate inference, particularly beneficial for real-time applications. The algorithm’s robustness is likely evaluated through ablation studies, systematically varying hyperparameters to assess the model’s sensitivity. Synthetic and real-world datasets are used for evaluation, demonstrating the algorithm’s accuracy and efficiency compared to frequentist and other Bayesian baselines. The use of Hawkes processes with inhibition is also a likely feature, allowing for modeling both excitatory and inhibitory effects in the event dynamics.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending the proposed conjugate Bayesian two-step change point detection (CoBay-CPD) method to handle multivariate Hawkes processes, a considerably more complex scenario. Addressing the non-conjugacy issue in the multivariate case remains a significant challenge, requiring innovative data augmentation strategies or alternative inference techniques. Another area of focus could be improving the method’s robustness to various hyperparameter choices, potentially through Bayesian optimization or more sophisticated prior distributions. Investigating the impact of different basis functions on the accuracy and efficiency of the method is also warranted, especially considering their influence on model flexibility and computational cost. Furthermore, exploring the method’s adaptability to non-stationary Hawkes processes with time-varying parameters would increase its practical applicability. Finally, evaluating the algorithm’s performance on a broader range of real-world datasets across diverse domains would further solidify its effectiveness and highlight its strengths and limitations. Rigorous comparisons with state-of-the-art methods on these expanded datasets are essential for comprehensive validation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

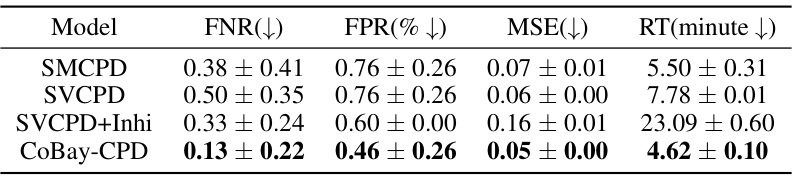

This figure shows the results of the change point detection experiment using synthetic data. Panel (a) compares the change point detection performance of CoBay-CPD against several baseline methods. Panels (b) through (g) illustrate the accuracy of CoBay-CPD in estimating model parameters (λ, μ, w1, w2, w3, w4) by comparing its estimates to the true values used to generate the synthetic data.

This figure shows the results of change point detection experiments using synthetic data. Panel (a) compares the change point detection performance of CoBay-CPD against three other methods (SMCPD, SVCPD, SVCPD+Inhibition). Panel (b) displays the estimated intensity parameter (λ) from CoBay-CPD, illustrating that the model accurately estimates the true value. Panels (c) through (g) show the estimated model parameters (μ, w1, w2, w3, and w4) from CoBay-CPD, further demonstrating model accuracy.

This figure presents the results of change point detection experiments using synthetic data. Panel (a) compares the performance of CoBay-CPD against several baseline methods, showing the detected change points alongside the ground truth. Panel (b) displays the estimated intensity parameter (λ) obtained from CoBay-CPD, demonstrating its accuracy by showing close alignment with the true parameter values. Panels (c) through (g) visualize the estimated model parameters (μ, w1, w2, w3, w4) from CoBay-CPD, further showcasing its accurate parameter estimation capabilities.

More on tables

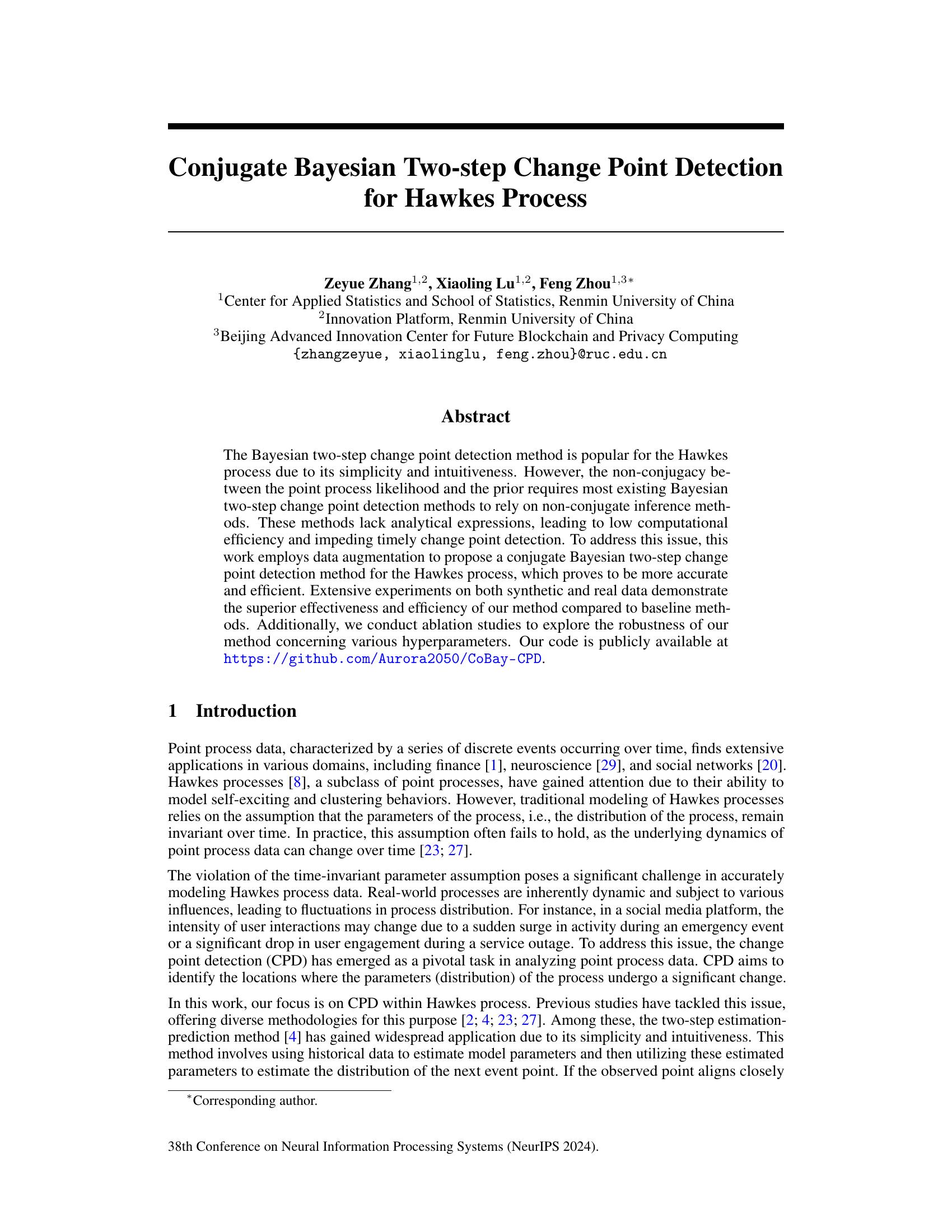

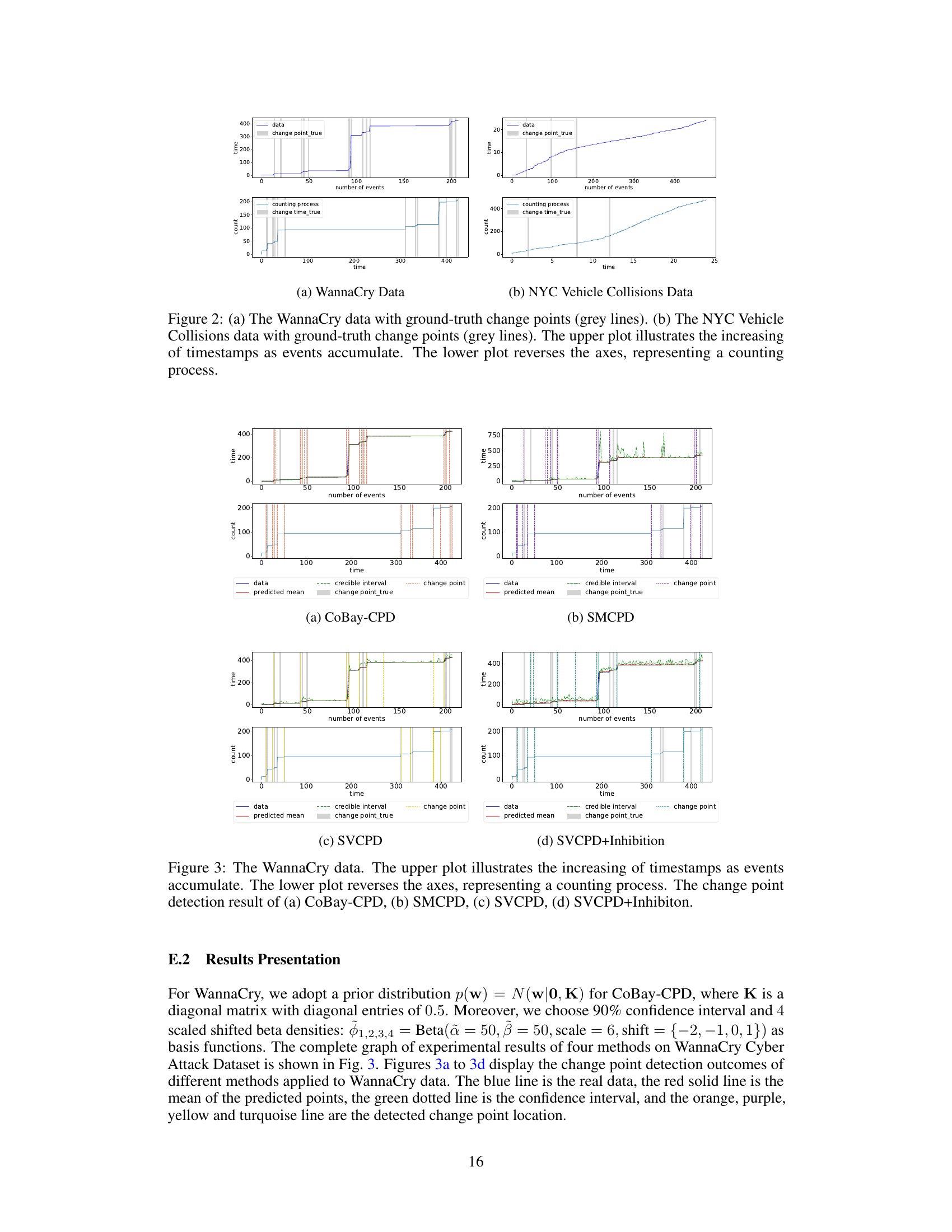

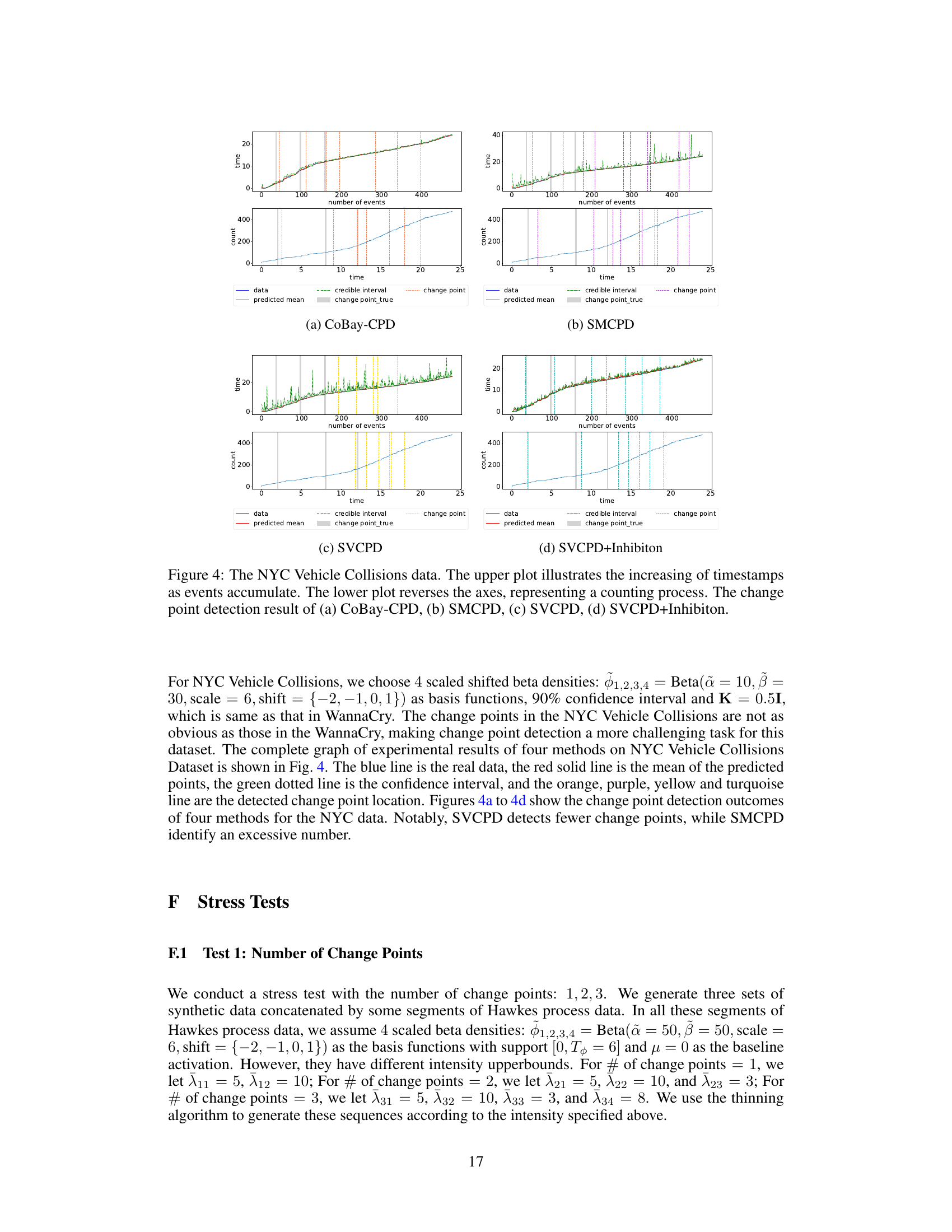

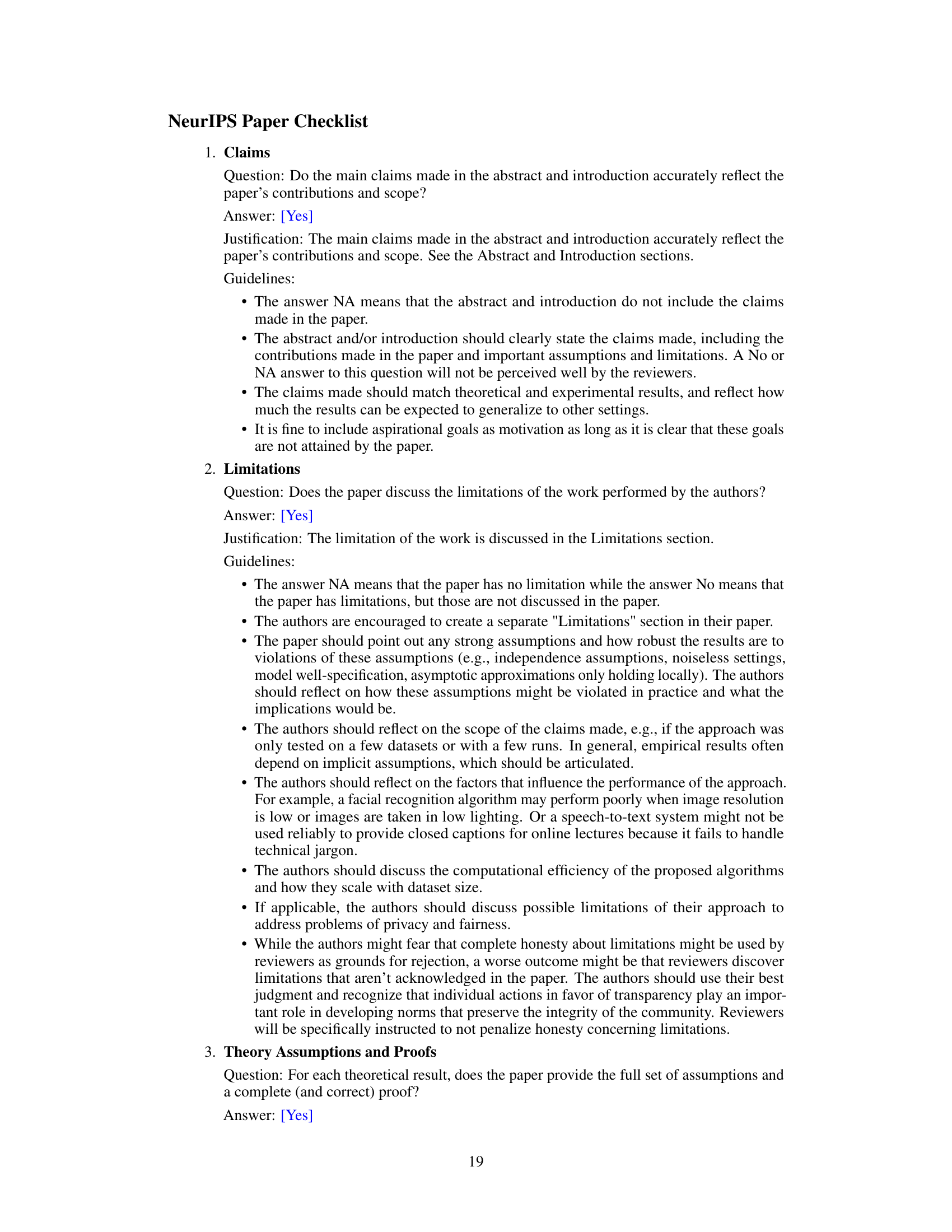

This table presents the results of the four methods (SMCPD, SVCPD, SVCPD+Inhibition, and CoBay-CPD) on two real-world datasets: WannaCry and NYC Vehicle Collisions. For each dataset and method, it shows the False Negative Rate (FNR), False Positive Rate (FPR), Mean Squared Error (MSE), and Running Time (RT). Lower values for FNR and FPR, and MSE indicate better performance, while a lower RT indicates faster computation. The table allows for a comparison of the methods’ performance on real-world data, rather than just synthetic data.

This table presents the performance comparison of CoBay-CPD against several baseline methods on a synthetic dataset. The metrics used are False Negative Rate (FNR), False Positive Rate (FPR), Mean Square Error (MSE), and Running Time (RT). Lower values for FNR and FPR and MSE are better, indicating higher accuracy and efficiency. The table shows that CoBay-CPD achieves significantly better performance than other methods across all metrics.

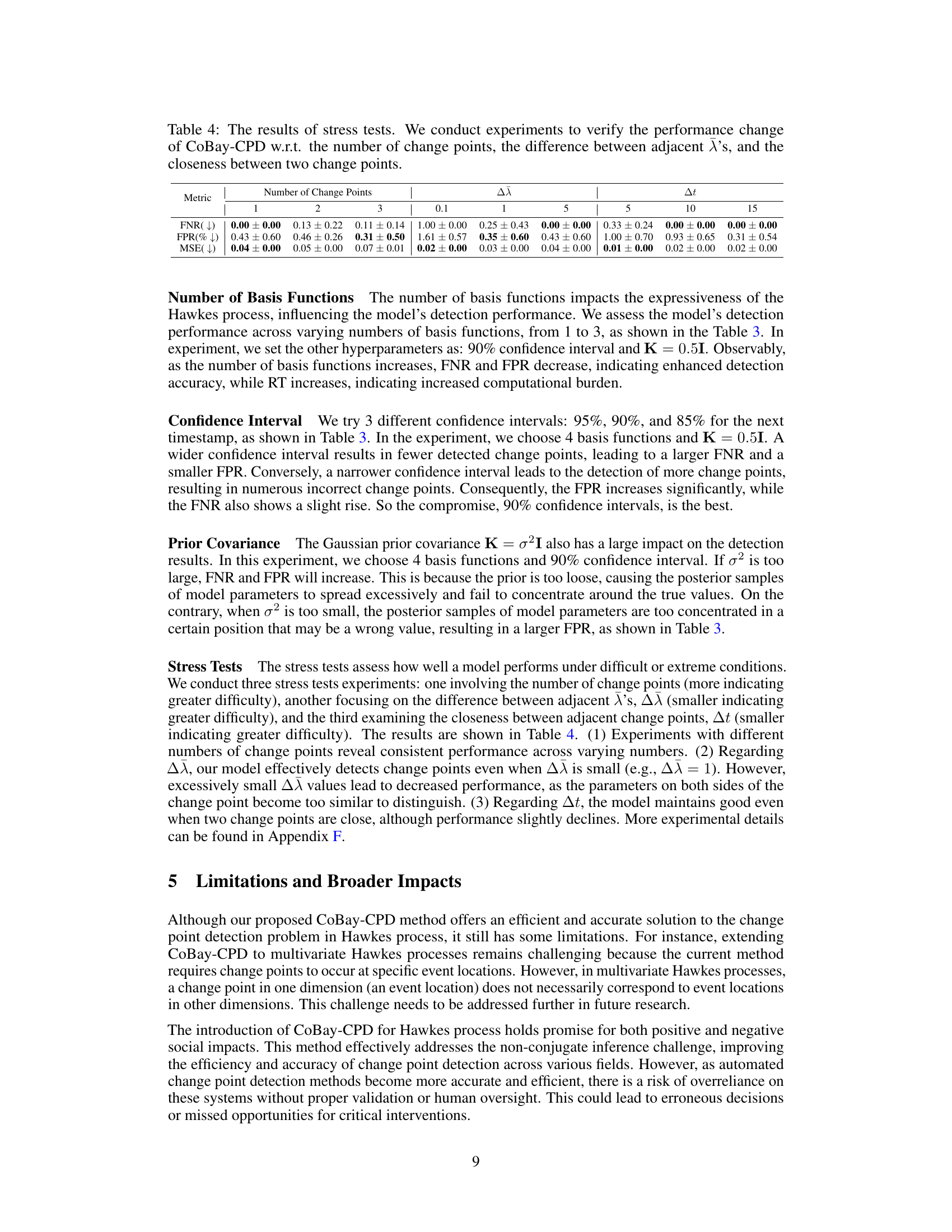

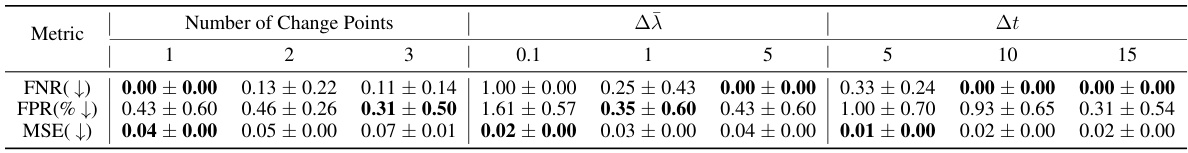

This table presents the results of stress tests performed on the CoBay-CPD model to evaluate its robustness under various conditions. The tests varied the number of change points, the difference in intensity (λ) between adjacent segments, and the proximity of change points. The FNR (False Negative Rate), FPR (False Positive Rate), and MSE (Mean Squared Error) were measured for each condition to assess the model’s accuracy and efficiency.

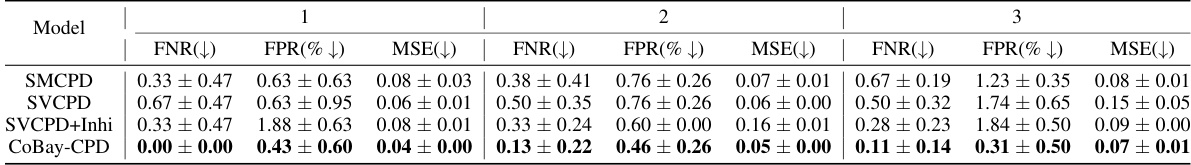

This table presents the False Negative Rate (FNR), False Positive Rate (FPR), and Mean Squared Error (MSE) for four different change point detection methods (SMCPD, SVCPD, SVCPD+Inhibition, and CoBay-CPD) across three different scenarios with varying numbers of change points (1, 2, and 3). The metrics evaluate the accuracy and efficiency of each method in detecting change points within a Hawkes process. Lower FNR and FPR values indicate better performance, while lower MSE signifies greater accuracy in predicting the timing of change points. This data helps illustrate the relative strengths and weaknesses of each algorithm in terms of robustness and precision when handling datasets with different complexities.

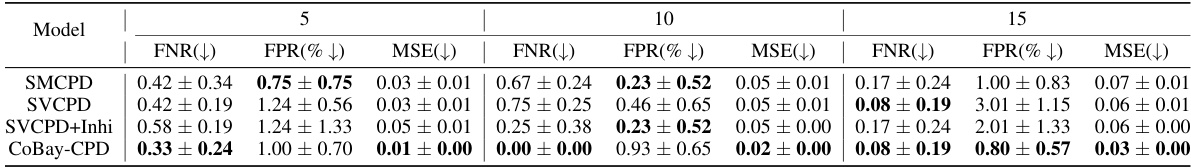

This table presents the False Negative Rate (FNR), False Positive Rate (FPR), and Mean Squared Error (MSE) for four different change point detection methods (SMCPD, SVCPD, SVCPD+Inhibition, and CoBay-CPD) on synthetic datasets. The experiment varied the difference (Δλ) between the intensity parameters (λ) of adjacent segments of the Hawkes process. Lower values of FNR and FPR indicate better performance, and lower MSE indicates more accurate prediction of change points.

This table presents the results of a comparative study on synthetic data, evaluating four different change point detection methods: SMCPD, SVCPD, SVCPD+Inhibition, and the proposed CoBay-CPD. The metrics used are False Negative Rate (FNR), False Positive Rate (FPR), Mean Squared Error (MSE), and Running Time (RT). Lower values of FNR and FPR, and MSE, and RT are preferable. The table helps to show the relative performance of CoBay-CPD against existing methods on a controlled, synthetic dataset.

Full paper#