↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Neural collapse, a phenomenon previously observed in classification, is investigated for its presence in regression tasks. The paper finds that neural networks exhibit “Neural Regression Collapse” (NRC) characterized by specific patterns in the last layer feature vectors and weight vectors. This collapse is shown to occur in a variety of datasets and network architectures, demonstrating its prevalence.

The researchers explain this behavior using the Unconstrained Feature Model (UFM). The UFM allows them to mathematically demonstrate that these observed patterns emerge as solutions under certain regularization conditions in a regression setting. This theoretical analysis contributes to a deeper understanding of the phenomenon, suggesting its universality in deep learning and providing a framework for further investigation into the implications of neural collapse in regression.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it extends the concept of neural collapse (a phenomenon observed in classification tasks) to regression tasks, a common area in machine learning. It provides a theoretical framework for understanding this new form of collapse and suggests that neural collapse might be a universal behavior in deep learning, opening exciting avenues for future research and model improvement.

Visual Insights#

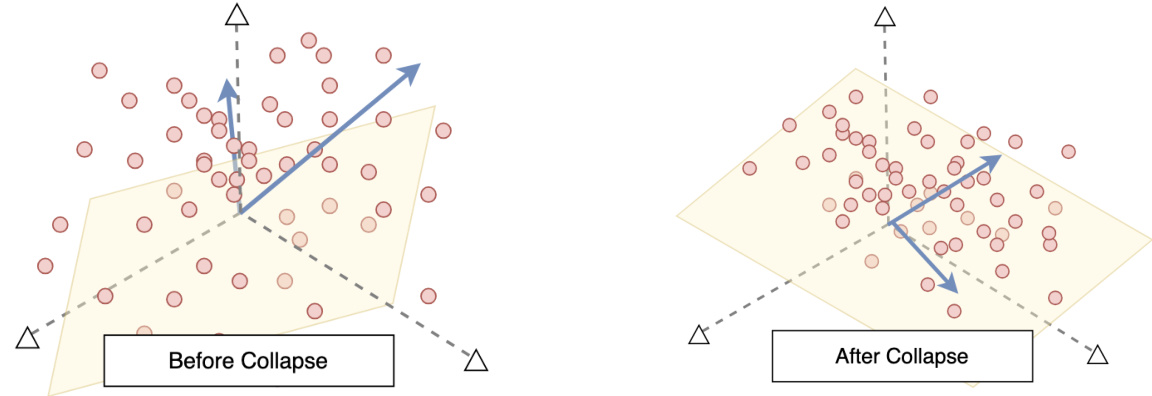

This figure visualizes the neural regression collapse phenomenon. Before the collapse (left panel), the sample features (red dots) are scattered and not aligned with the principal components (yellow plane) or the weight vectors (blue arrows). After training and the collapse (right panel), the feature vectors and the weight vectors have collapsed into the same subspace spanned by the principal components of the feature vectors. This subspace is two-dimensional (n=2) in this example. The angles between the weight vectors are now determined by the covariance matrix of the target variables.

This table summarizes the six datasets used in the neural regression collapse analysis. It shows the dataset name, the size of the dataset (number of data points), the input type (raw state or RGB image), the target dimension (n, which indicates the number of continuous values being predicted), the target correlation (correlation coefficients between the target components for datasets with multiple target dimensions), and the minimum eigenvalue (λmin) of the covariance matrix of the target vectors. The target dimension and target correlations are key indicators for understanding the nature of the multivariate regression problems, and λmin gives insight into the overall distribution of target data and will play a role in the mathematical explanation of neural collapse.

In-depth insights#

Neural Regression Collapse#

The concept of “Neural Regression Collapse” (NRC) extends the phenomenon of “Neural Collapse” (NC) observed in classification tasks to the realm of regression. NRC describes the convergence of last-layer features and weights to low-dimensional subspaces during the final stages of training. This collapse isn’t arbitrary; the subspaces are specifically linked to the principal components of the input features and the target variables’ covariance structure. The authors establish NRC empirically across several datasets and network architectures, highlighting its prevalence. A key contribution is the theoretical explanation using the Unconstrained Feature Model (UFM), which demonstrates how appropriate regularization parameters drive NRC, showing that the phenomenon isn’t merely coincidental but emerges as a solution to the optimization problem under these conditions. The study suggests that NRC might be a universal behavior in deep learning, implying that neural networks inherently simplify internal representations regardless of whether the task is classification or regression. This is a significant finding, potentially paving the way for more efficient and simplified architectures.

UFM in Regression#

The application of the Unconstrained Feature Model (UFM) to regression problems offers a powerful framework for understanding neural collapse in this context. The UFM’s key strength lies in treating last-layer features as free variables, decoupling them from the network’s earlier layers. This simplifies the optimization problem, making it more amenable to theoretical analysis. By analyzing the UFM’s optimization landscape in regression settings, particularly with L2 regularization, we can mathematically explain the observed phenomena of Neural Regression Collapse (NRC). The emergence of NRC is directly linked to the presence of regularization; when regularization parameters are zero, collapse does not occur. This is a significant departure from the typical understanding of neural collapse in classification where regularization plays a crucial, preventative role. The UFM provides a theoretical bridge connecting empirical observations to a mathematical model, thus strengthening our understanding of deep learning’s inherent geometric tendencies. However, future research is needed to understand the implications of NRC on model generalization, a vital aspect not fully addressed by the current UFM analysis.

Empirical Validation#

An empirical validation section in a research paper would systematically test the study’s hypotheses. It would detail the datasets used, clearly describing their characteristics and relevance to the research questions. The methods of data collection and preprocessing would be explicitly stated. The choice of experimental design, including sample sizes and control groups, would be justified. Results would be presented with appropriate statistical analyses, highlighting significance levels and effect sizes. Visualizations, such as graphs and tables, would be used effectively to communicate the findings, and any limitations of the empirical approach would be transparently discussed. The results would be interpreted within the broader theoretical framework of the study, connecting the empirical observations to existing literature and theoretical predictions. Overall, a strong empirical validation section provides readers with the confidence that the study’s claims are well-supported by robust and credible evidence.

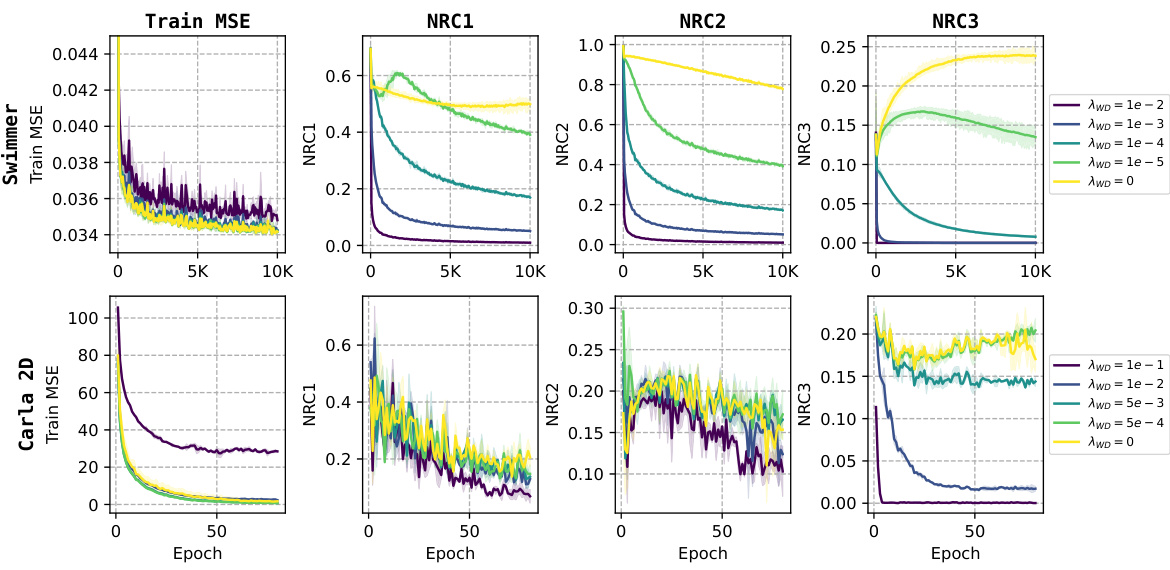

Weight Decay’s Role#

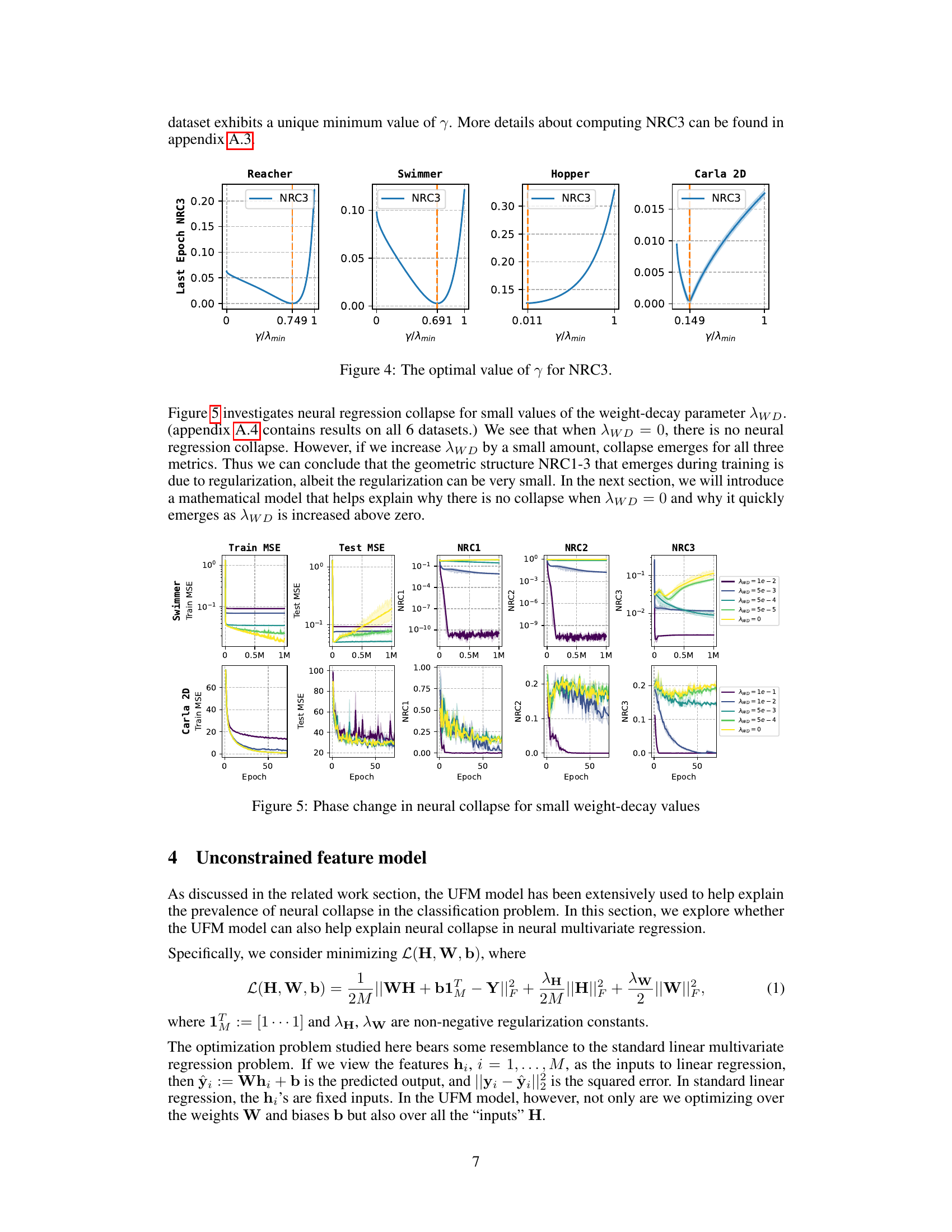

Weight decay, a regularization technique, plays a crucial role in the context of neural regression collapse. Without weight decay (λw = 0), the model exhibits no collapse, meaning feature vectors and weights do not converge to specific subspaces. However, introducing even a small amount of weight decay dramatically changes the model behavior, leading to the emergence of the neural regression collapse (NRC) phenomena. This suggests that the geometric structure of NRC is not an intrinsic property of neural regression alone, but rather a consequence of regularization. The precise nature of the collapse, particularly the relationship between weight vectors and the covariance matrix of the targets (NRC3), is highly sensitive to the magnitude of weight decay and likely reveals fundamental relationships within the optimization landscape of deep learning models. The theoretical framework presented utilizes the Unconstrained Feature Model (UFM) to provide a mathematical justification for these observations. This implies that the impact of weight decay is not merely empirical but also deeply connected to the underlying mathematical structure of the optimization problem itself. A deeper understanding of this weight decay-collapse relationship could lead to improvements in model training and generalization.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this neural regression collapse study could explore generalization capabilities of models exhibiting this phenomenon. Understanding how NRC affects the model’s ability to extrapolate to unseen data is crucial. Further investigation should also focus on different loss functions and their influence on NRC, moving beyond the L2 loss explored here. Analyzing the impact of dataset characteristics, such as noise levels and data distribution, on the prevalence and nature of NRC is also important. Exploring connections between NRC and other regularization techniques, as well as investigating NRC in more complex architectures, could yield valuable insights. Finally, developing methods to mitigate or leverage NRC to improve model performance and efficiency is a significant area for future work. The universal applicability of neural collapse across various deep learning tasks warrants deeper investigation into its fundamental causes and potential benefits.

More visual insights#

More on figures

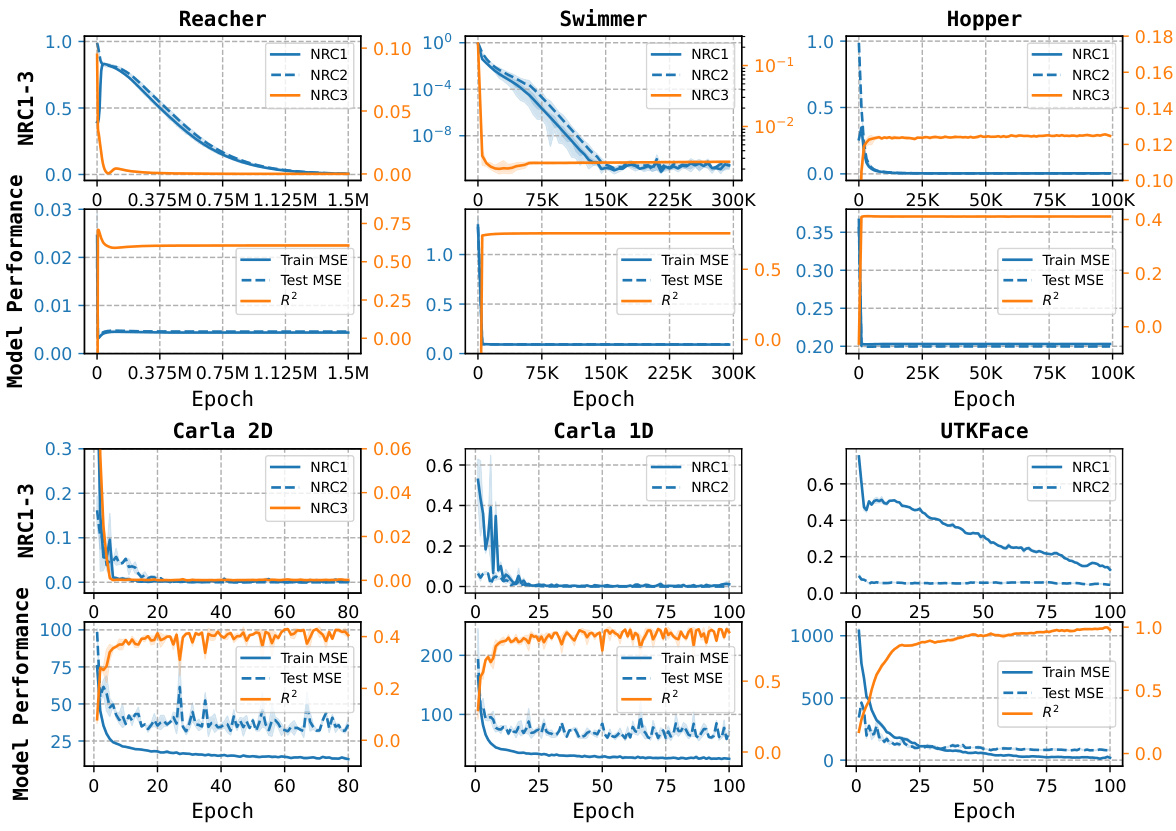

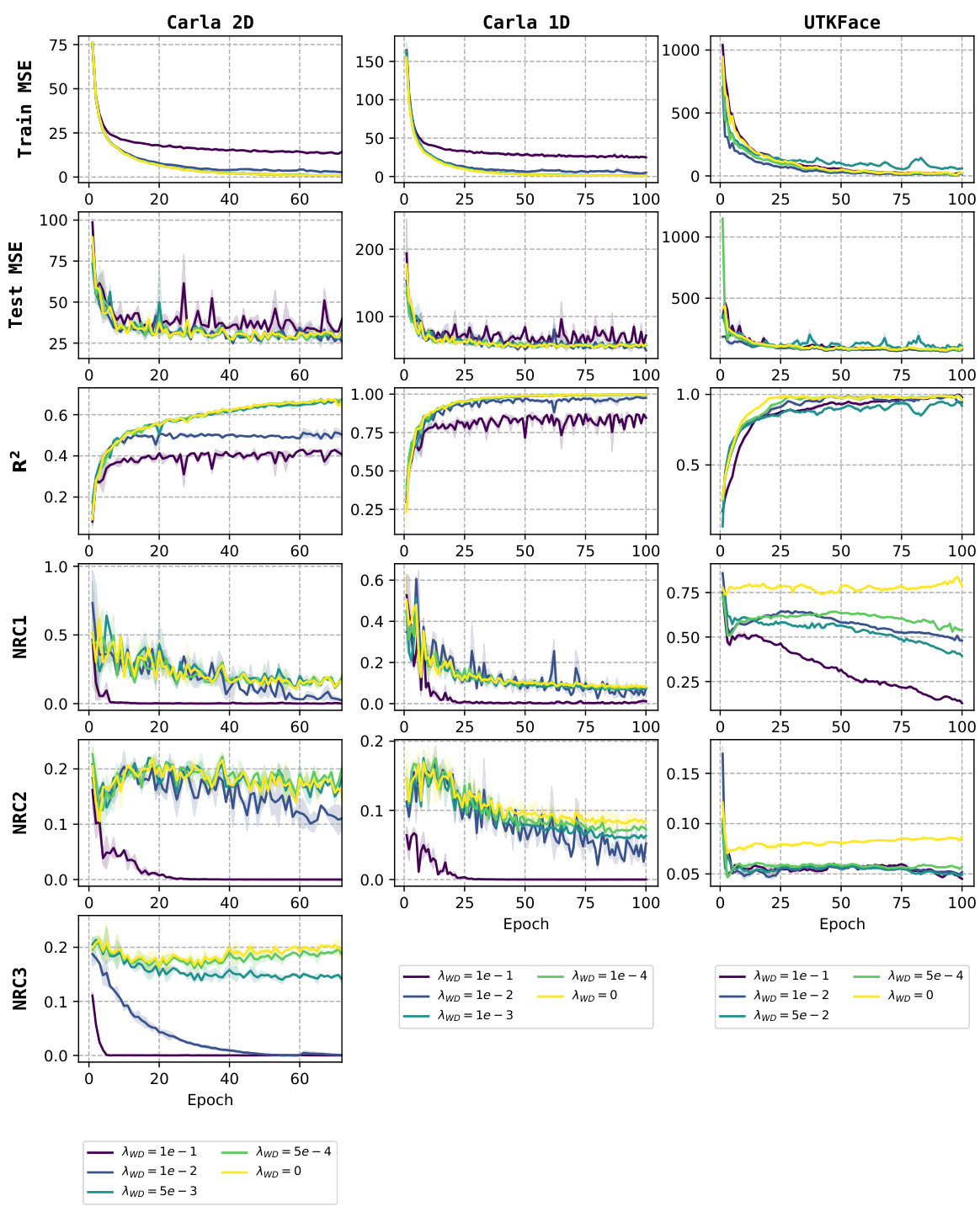

This figure shows the training and testing performance across six different datasets for a neural multivariate regression task. The metrics displayed include training and testing mean squared error (MSE), R-squared (R2), and the three components of Neural Regression Collapse (NRC1, NRC2, NRC3). NRC1-3 values close to zero indicate the presence of neural collapse. The plot shows that as the training progresses, both training and testing errors decrease, while the R-squared increases and approaches 1, suggesting improved model performance. The near-zero NRC1-3 values across all datasets demonstrate a high prevalence of neural regression collapse in the examined scenarios.

This figure displays the Explained Variance Ratio (EVR) for the top 5 principal components (PCs) of the feature matrix H during training, across six different datasets. The EVR represents the proportion of variance in the data explained by each PC. The figure demonstrates that for all datasets, after a short training period, a significant amount of variance is captured by the first n principal components, where n is the target dimension. This observation strongly supports the claim of feature vector collapse to an n-dimensional subspace. In contrast, the variance for other principal components remains very low or zero. This visualization adds strong empirical support to the claim of neural regression collapse (NRC).

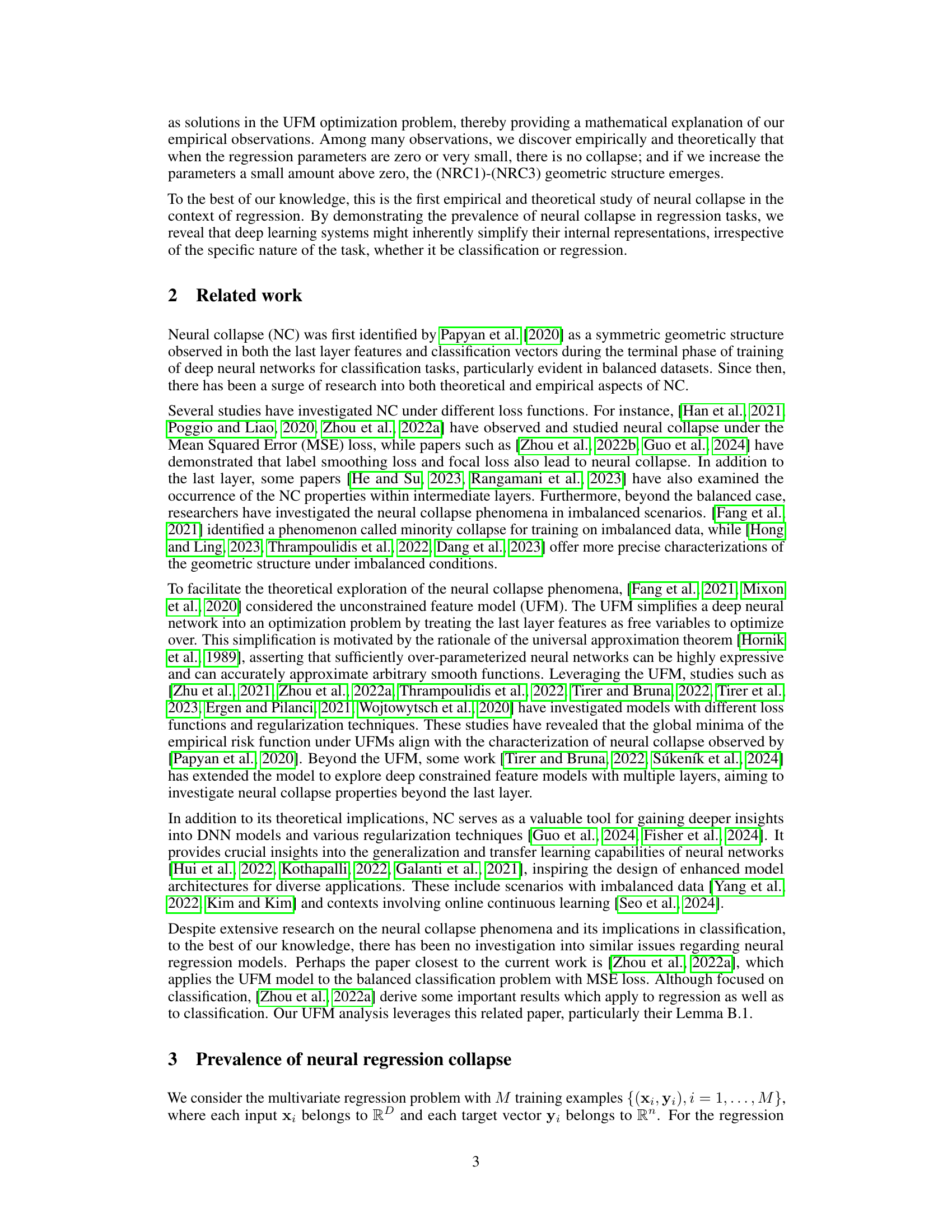

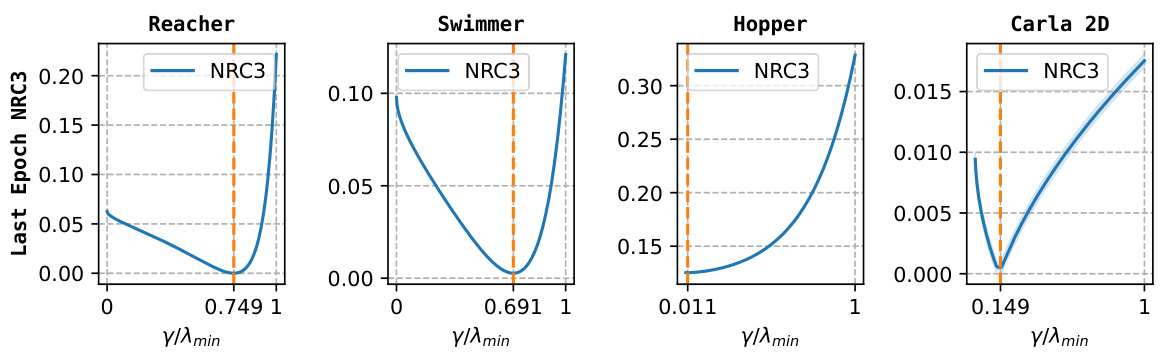

This figure shows the optimal value of γ for NRC3 (Neural Regression Collapse 3) across four different datasets: Reacher, Swimmer, Hopper, and Carla 2D. NRC3 is a measure of the alignment between the last-layer weight vectors and the target covariance matrix, and its optimal value indicates the degree of collapse observed. The x-axis represents γ/λmin, where γ is a constant and λmin is the minimum eigenvalue of the target covariance matrix. The y-axis shows the value of NRC3. The plots reveal dataset-specific optimal values for γ, demonstrating the diverse nature of neural collapse in regression tasks.

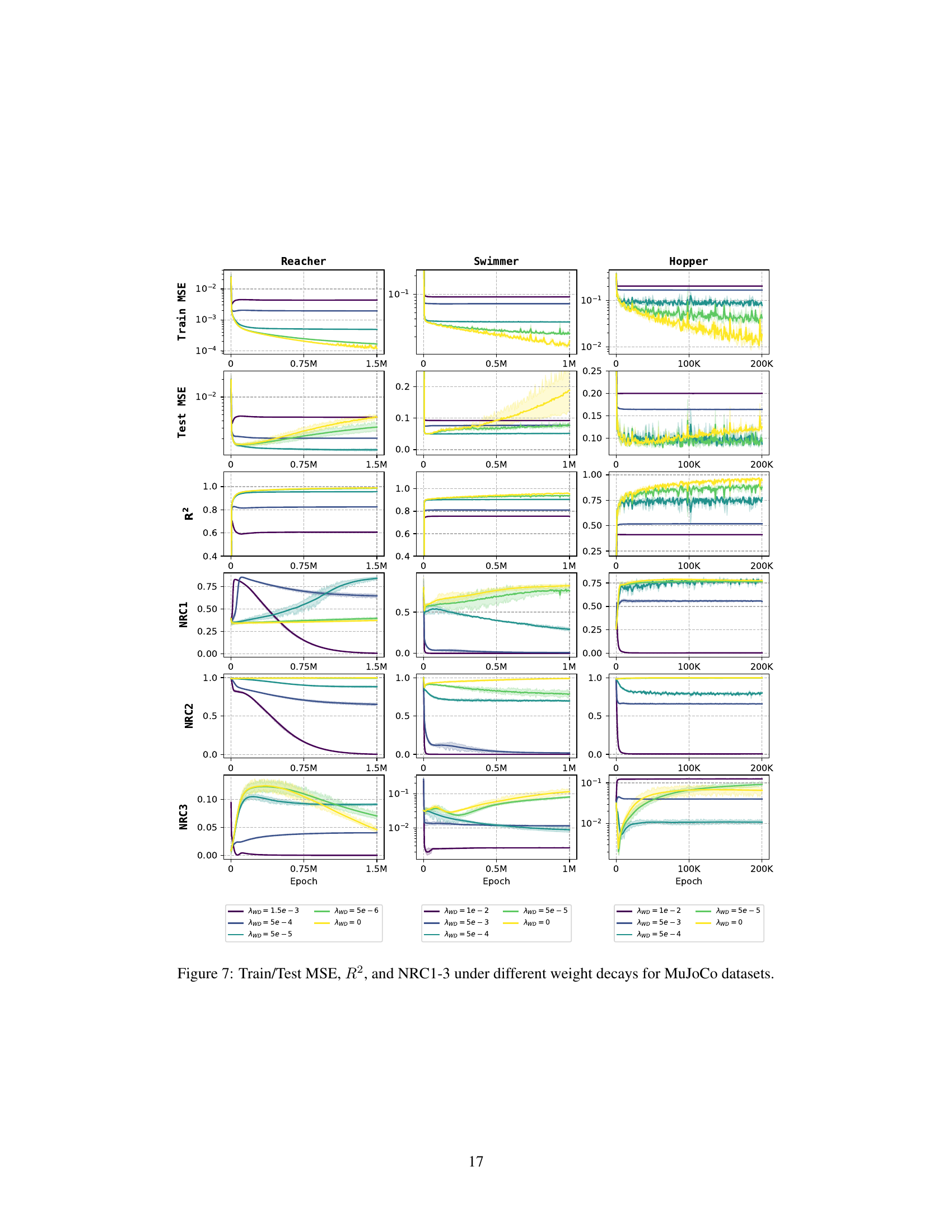

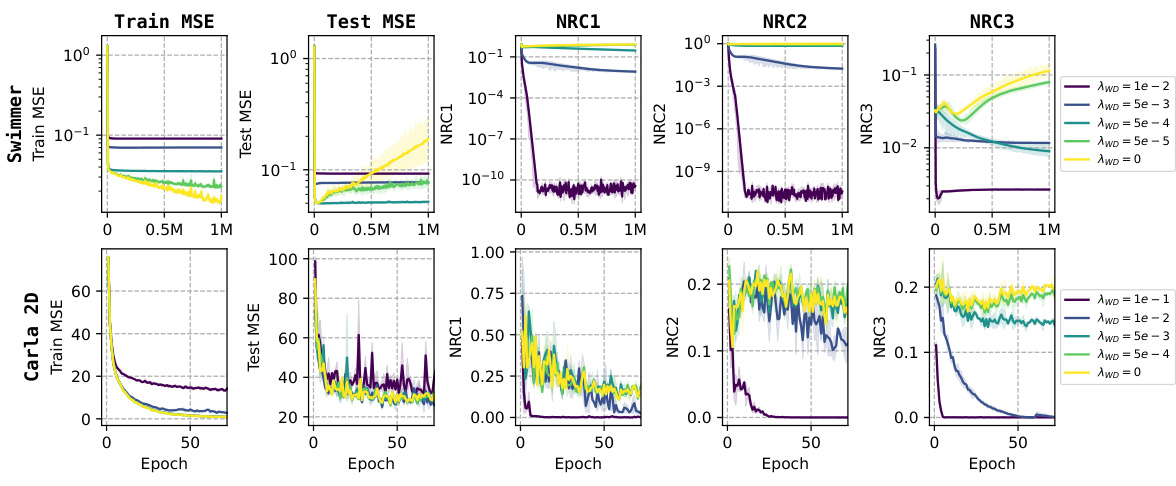

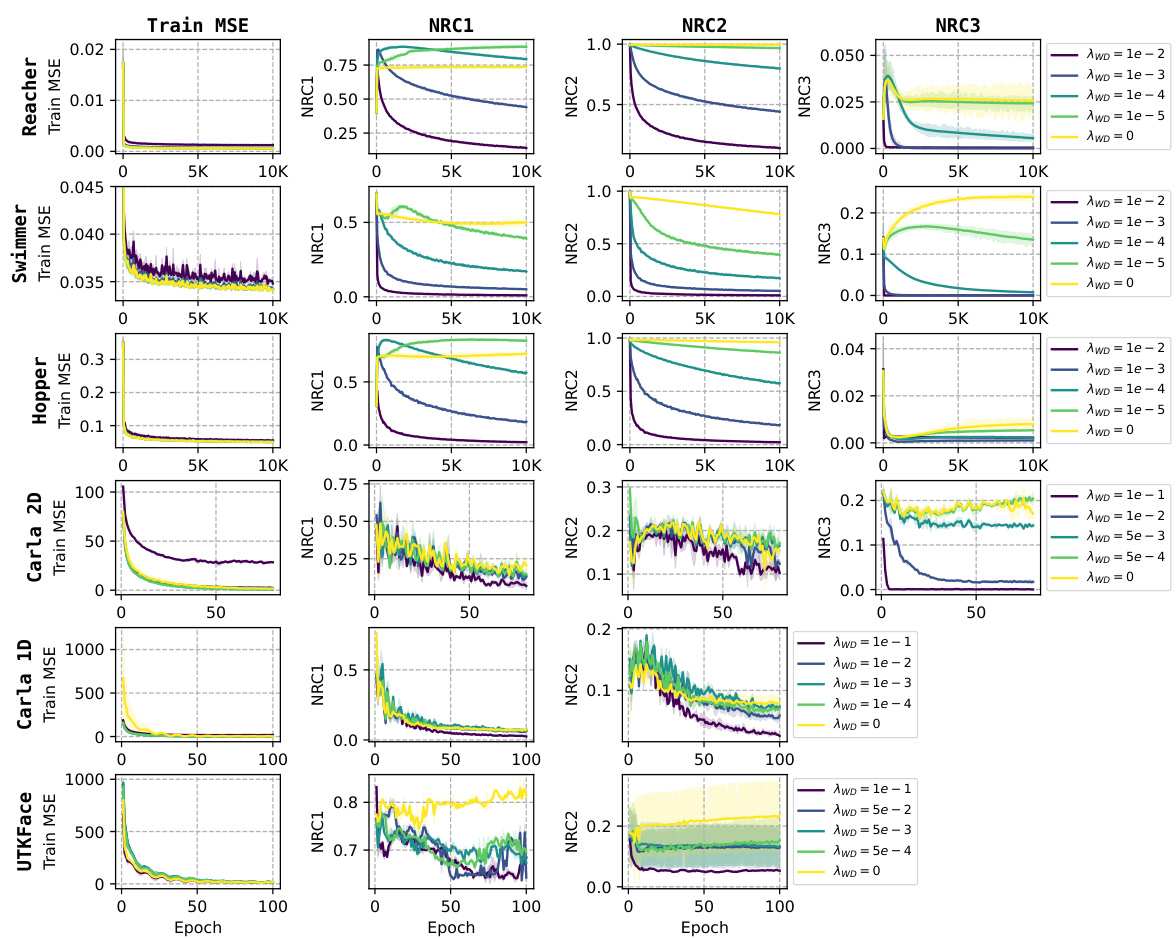

This figure presents the training and testing Mean Squared Errors (MSE), the coefficient of determination (R2), and the three metrics for Neural Regression Collapse (NRC1-3) across three MuJoCo datasets (Reacher, Swimmer, Hopper) under varying weight decay values (AWD). Each dataset is displayed as a column of subplots, showing how the training and testing performance, as well as the extent of neural collapse (NRC1-3), changes with different levels of weight decay. The results demonstrate that the extent of neural collapse is influenced by the weight decay parameter. With larger weight decay values, the collapse (NRC1-3) is generally more pronounced, while smaller values or no weight decay lead to less pronounced collapse.

This figure shows the results of the experiments on six different datasets (Swimmer, Reacher, Hopper, Carla 1D, Carla 2D, UTKFace). For each dataset, it displays the training and testing mean squared error (MSE), the coefficient of determination (R2), and the three metrics of Neural Regression Collapse (NRC1, NRC2, NRC3) over the training epochs. The figure demonstrates that as training progresses, the training and testing errors decrease, and the R2 values increase, indicating that model performance stabilizes. More importantly, this figure shows the convergence of NRC1, NRC2, and NRC3 towards zero for all six datasets, confirming the prevalence of neural regression collapse across various datasets and tasks.

This figure shows the results of six different experiments on six different datasets. Each experiment trained a deep neural network model for a multivariate regression task. The plots show how training and testing mean squared error (MSE) and the R-squared (R2) value change as the number of training epochs increases. It also shows how three metrics related to neural regression collapse (NRC1, NRC2, and NRC3) change with increasing epochs. The three NRC metrics measure aspects of the collapse of the last layer feature vectors and weight vectors. The results are consistent across all six datasets.

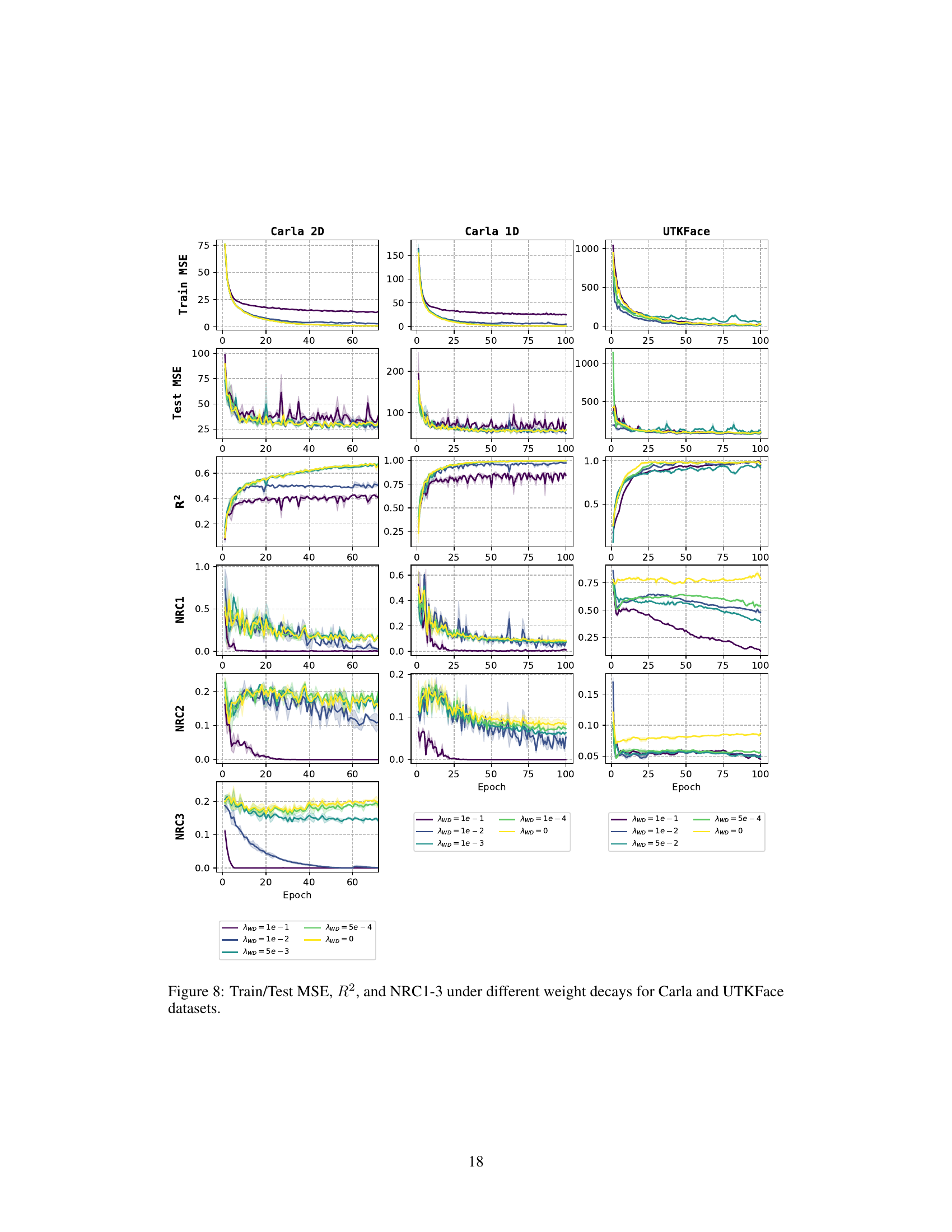

This figure presents the training and testing mean squared errors (MSE), the coefficient of determination (R2), and the three Neural Regression Collapse (NRC) metrics (NRC1, NRC2, NRC3) for the CARLA (2D and 1D versions) and UTKFace datasets. Different lines represent different values for the weight decay parameter (AWD), ranging from 0 to 1e-1. The results show the effect of varying the weight decay hyperparameter on the convergence speed and the extent of neural collapse observed during training. The goal is to demonstrate that neural regression collapse is still observed across various datasets even when the weight decay is small.

This figure displays the results of the neural regression collapse experiment conducted on six different datasets. For each dataset, it shows the training and testing mean squared error (MSE), the R-squared (R2) value which represents the goodness of fit, and three metrics (NRC1, NRC2, NRC3) that quantify the degree of neural regression collapse. The x-axis represents the number of epochs (training iterations), while the y-axis shows the values of the metrics. The figure demonstrates that across all six datasets, neural regression collapse (NRC) occurs, as evidenced by the convergence of NRC1, NRC2, and NRC3 to zero during training.

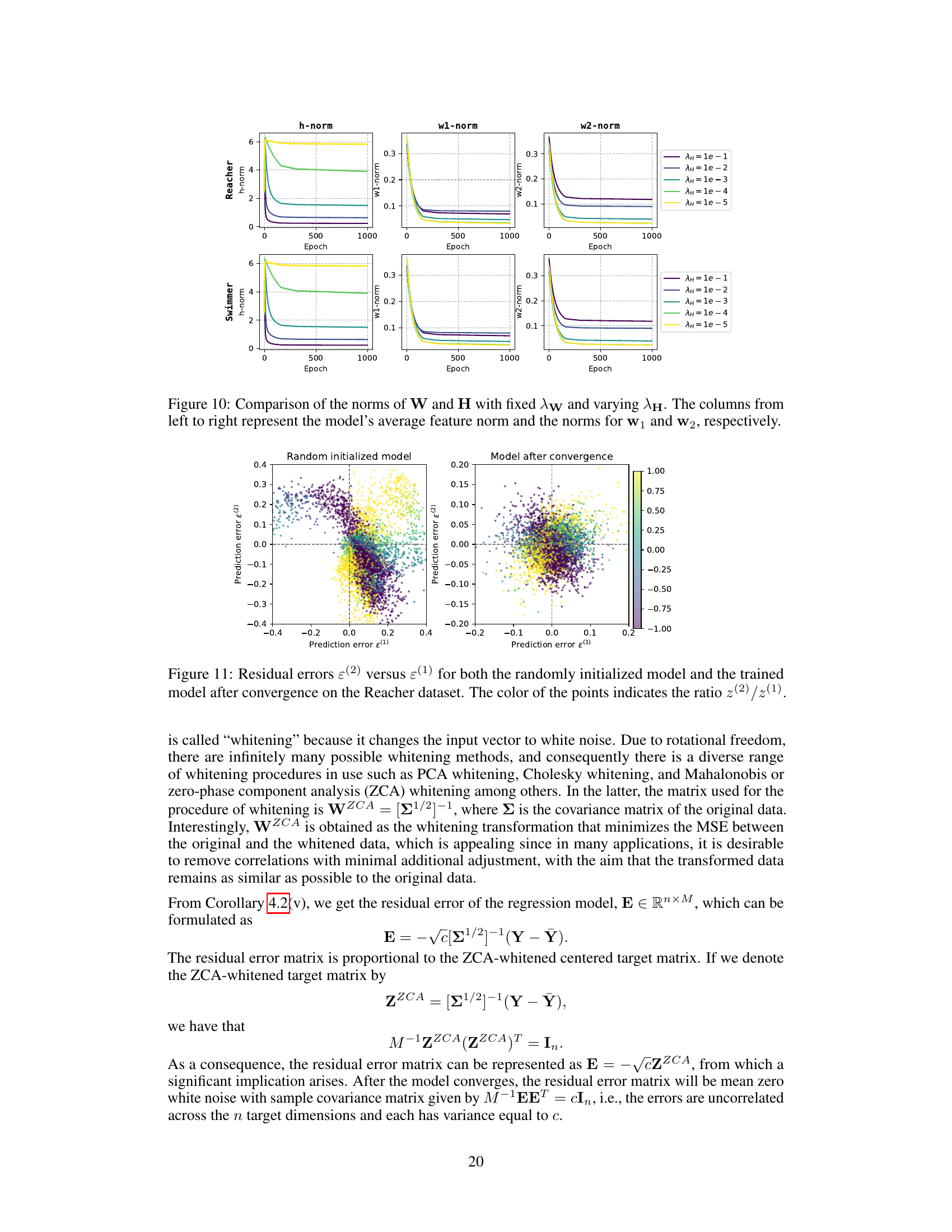

This figure shows the impact of varying the regularization parameter λH on the norms of the weight matrix W and the feature matrix H, while keeping λw constant. The norms are plotted against the number of training epochs for the Reacher and Swimmer datasets. Each subfigure shows the norm of the feature vectors (H) and the norms of the weight vectors (w1 and w2). The plots demonstrate how changing λH affects the final norms of the features and weights after training.

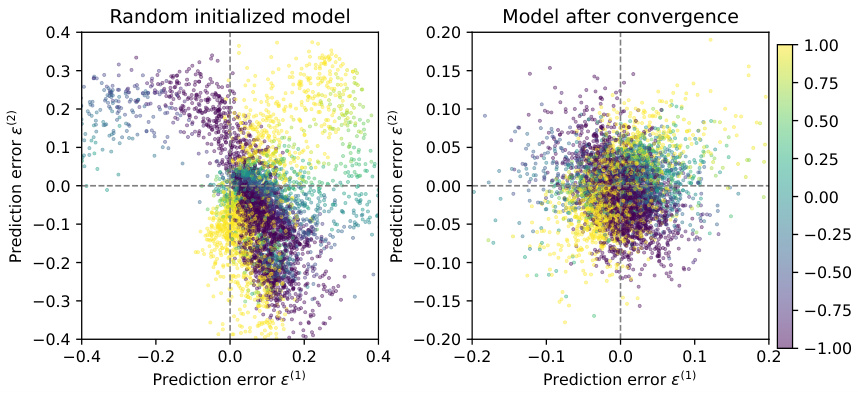

This figure visualizes the residual errors of a 2-dimensional regression task on the Reacher dataset. The left panel shows the residual errors for a randomly initialized model, while the right panel shows the errors after the model has converged through training. Each point represents a data sample, with its color indicating the ratio of the second and first standardized target components (z(2)/z(1)). The plot demonstrates that after training, the residual errors become uncorrelated and resemble white noise, aligning with the theoretical predictions made earlier in the paper.

More on tables

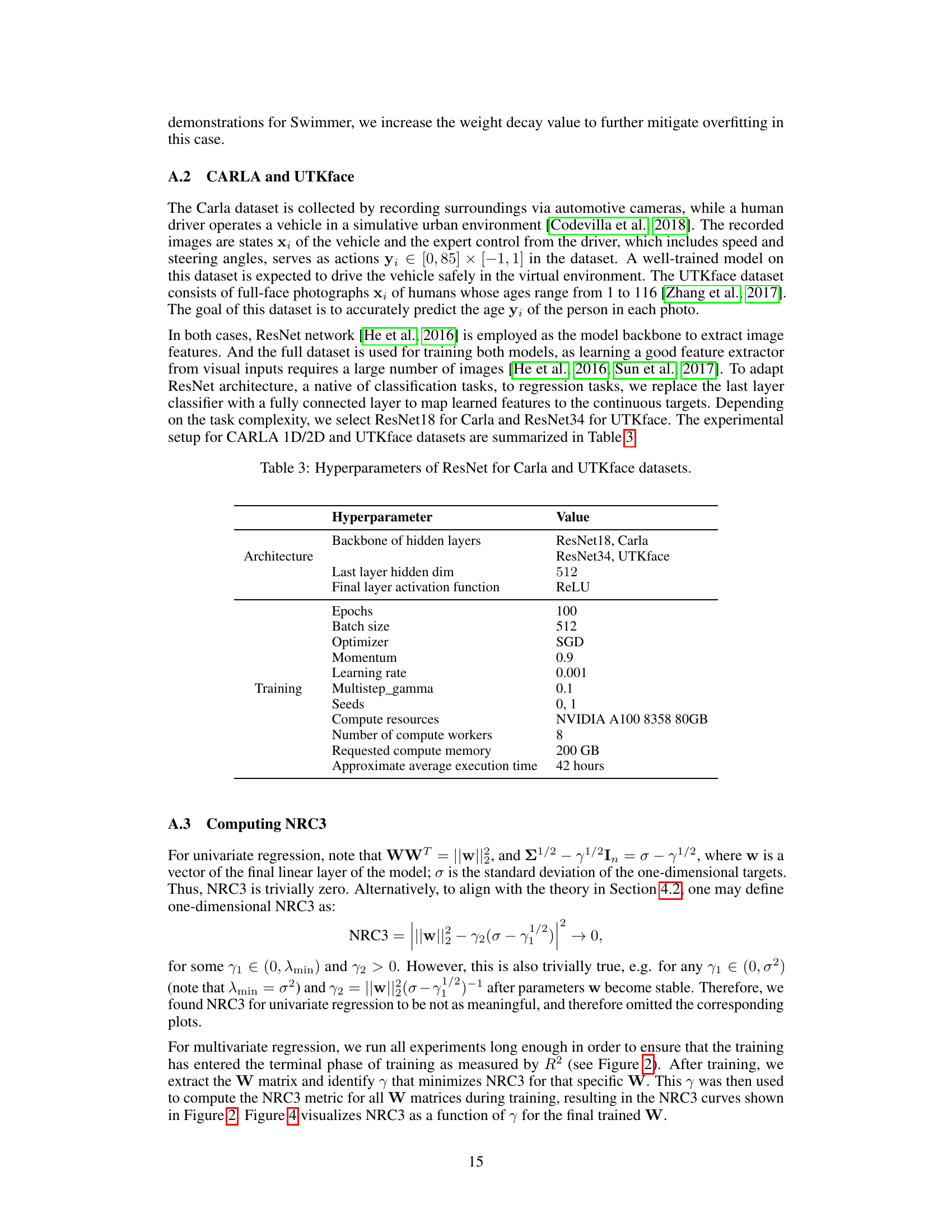

This table details the hyperparameters used in the experiments conducted on the MuJoCo datasets (Swimmer, Reacher, and Hopper). It specifies settings for the model architecture (number of hidden layers, hidden layer dimension, activation function, number of linear projection layers), training process (epochs, batch size, optimizer, learning rate, weight decay), experimental setup (seeds), and compute resources (CPU, number of workers, memory, approximate execution time). The values given are specific to each dataset for optimal performance.

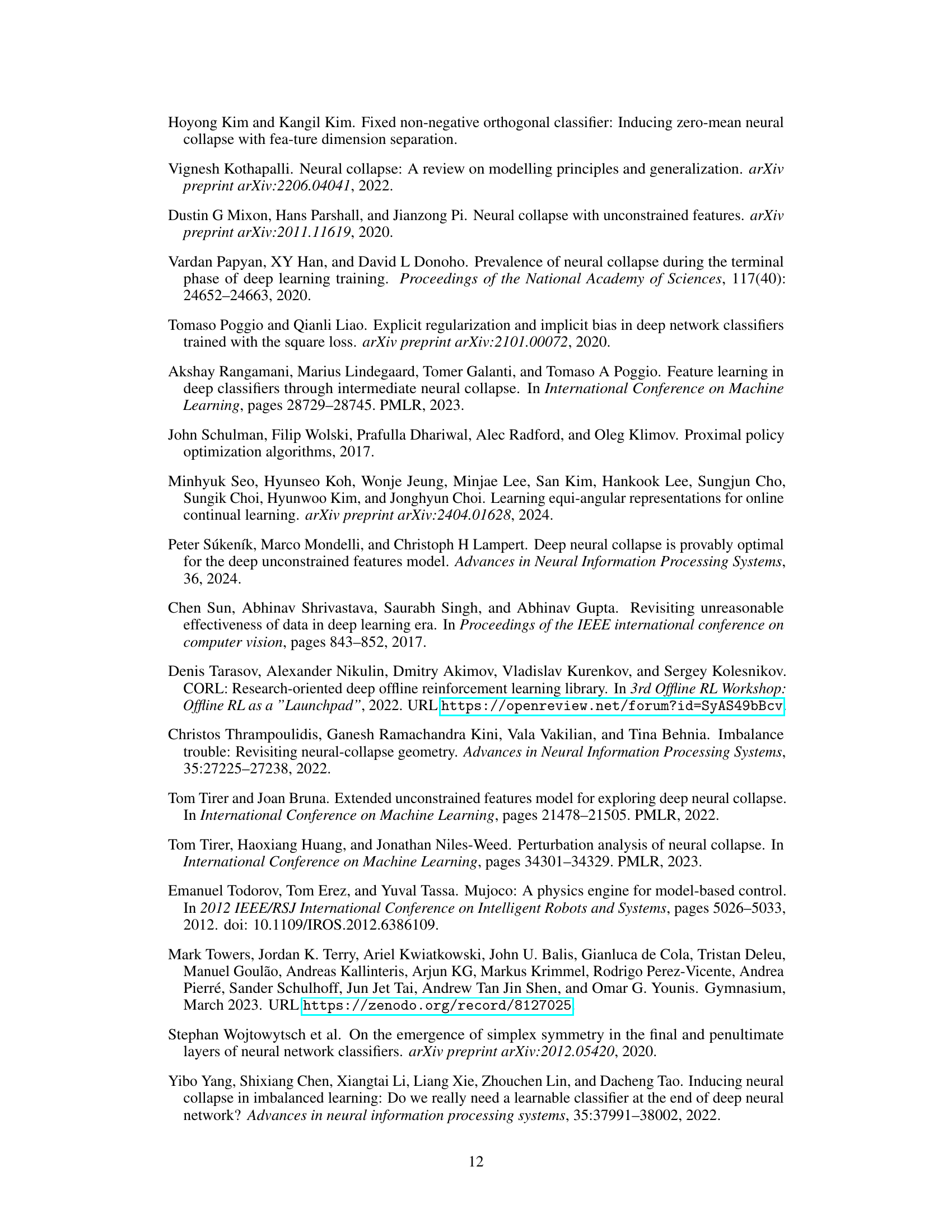

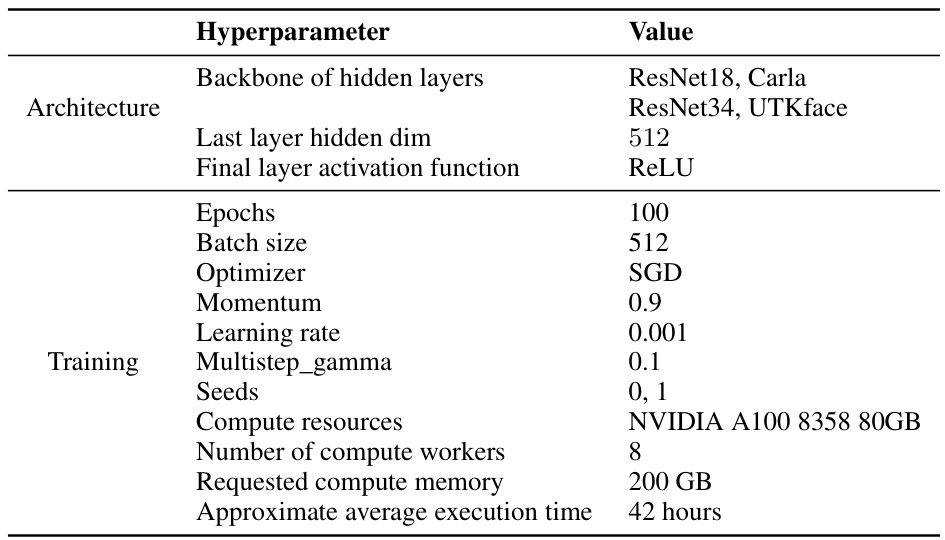

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the ResNet models on the CARLA and UTKFace datasets. It shows the architecture details, training settings, computational resources used, and the approximate execution time. This information is essential for understanding the experimental setup and reproducing the results. The architecture section includes the backbone of hidden layers, last layer dimension, and final layer activation function. The training section includes epochs, batch size, optimizer, momentum, learning rate, multistep gamma, seeds, compute resources, number of compute workers, requested memory and approximate average execution time.

Full paper#