↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Bayesian Optimization (BO) efficiently finds the best input for a given function. Traditional BO methods struggle when evaluating multiple inputs simultaneously (batched BO), especially when dealing with complex or noisy data. Existing batched BO approaches often lack fine-grained control over exploration and exploitation, and many require computationally expensive sampling techniques.

This paper introduces a new acquisition function called BEEBO that directly addresses these challenges. BEEBO uses a statistically sound method to handle batches, providing tight control over the explore-exploit trade-off via a single hyperparameter. Furthermore, it efficiently handles noisy data, even when noise levels vary across different inputs. Experiments show that BEEBO outperforms existing methods in many scenarios, proving its effectiveness and efficiency.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces BEEBO, a novel acquisition function for Bayesian Optimization that addresses limitations of existing methods in handling batched acquisitions. It offers improved explore-exploit trade-off control and generalizes well to heteroskedastic noise, opening new avenues for efficient global optimization across diverse applications.

Visual Insights#

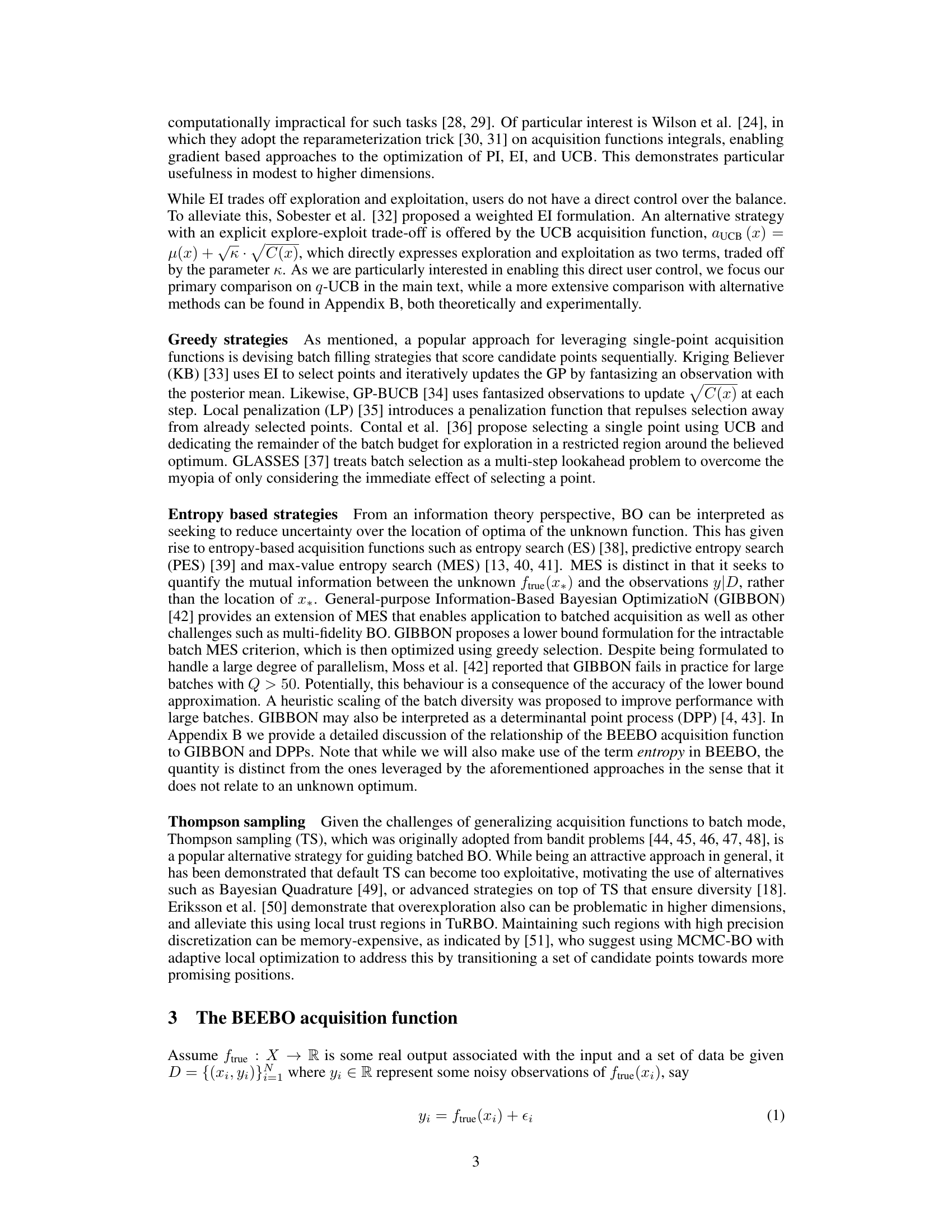

This figure compares the exploration-exploitation behavior of q-UCB and BEEBO in a Bayesian Optimization setting with a batch size of 100. The background shows a heatmap representing the Ackley function’s landscape. The black dots represent initial random points used to initialize the Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model. The redder points indicate the locations selected by each algorithm for further evaluation. The left column shows exploration, and the right column shows exploitation. q-UCB, even when the exploration parameter κ is adjusted, shows inconsistent exploration and exploitation behavior. The top-right plot illustrates how a large value of κ leads to poor exploration, whereas the top-left plot shows how a low value leads to poor exploitation. In contrast, BEEBO, with its temperature parameter T’, enables a much tighter control over the balance between exploration and exploitation. The bottom row demonstrates this, showcasing how BEEBO balances exploration and exploitation in both low and high temperature settings.

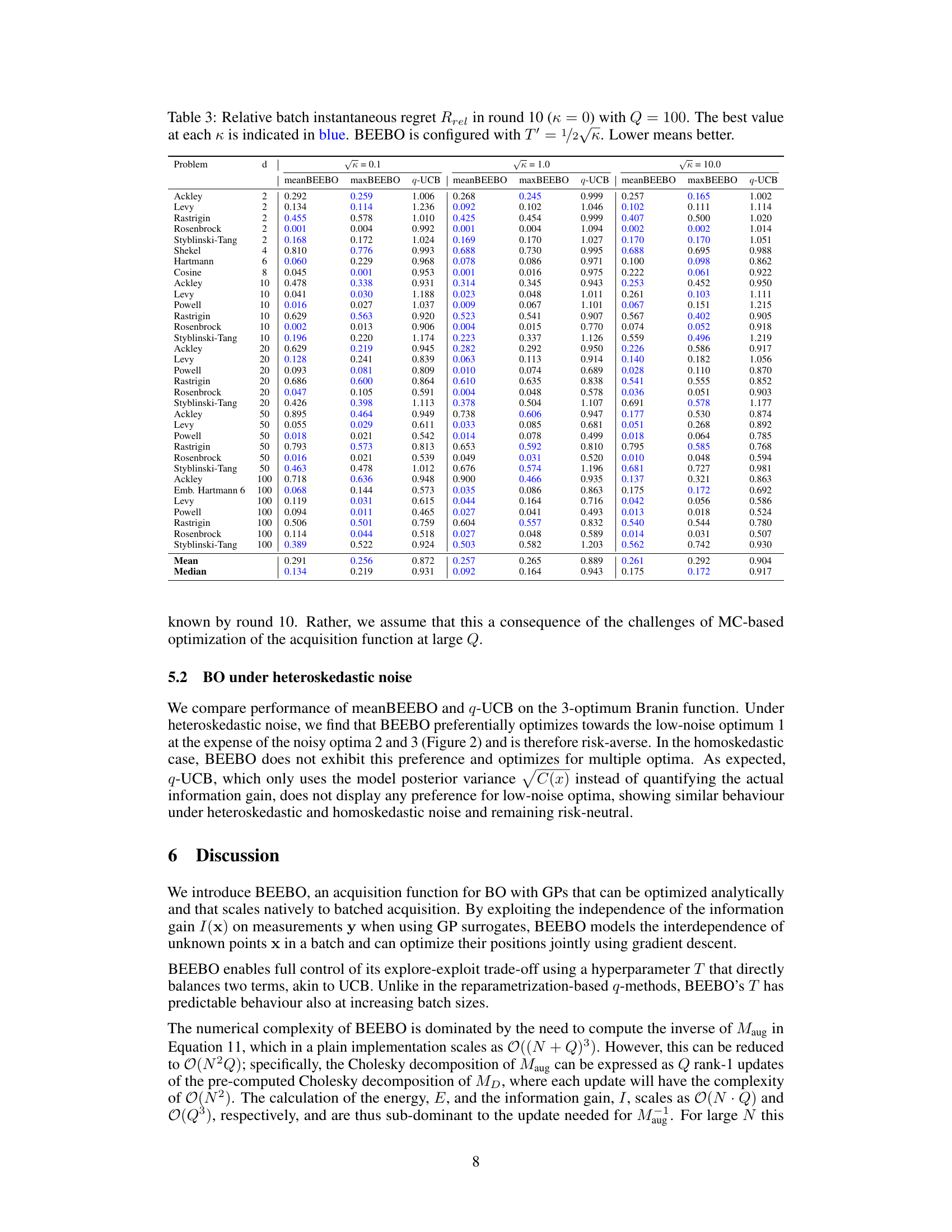

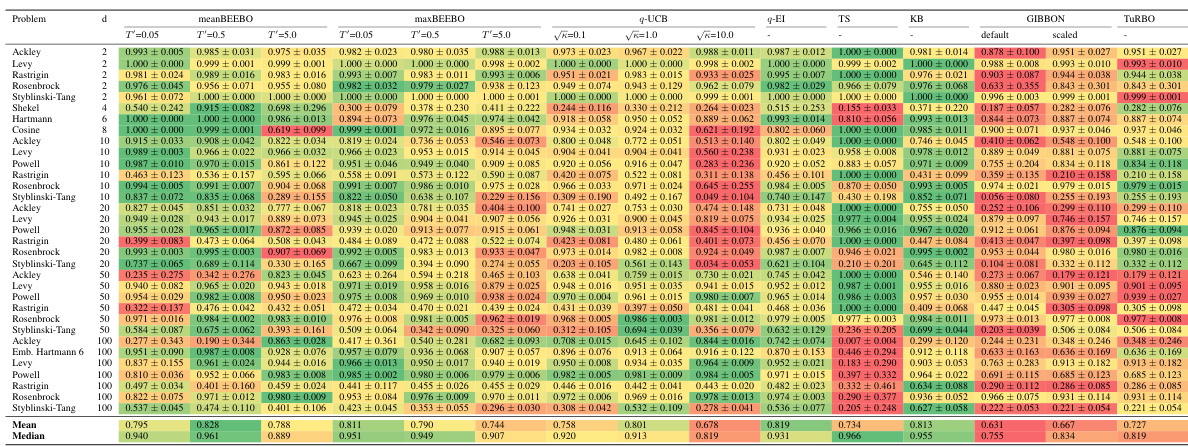

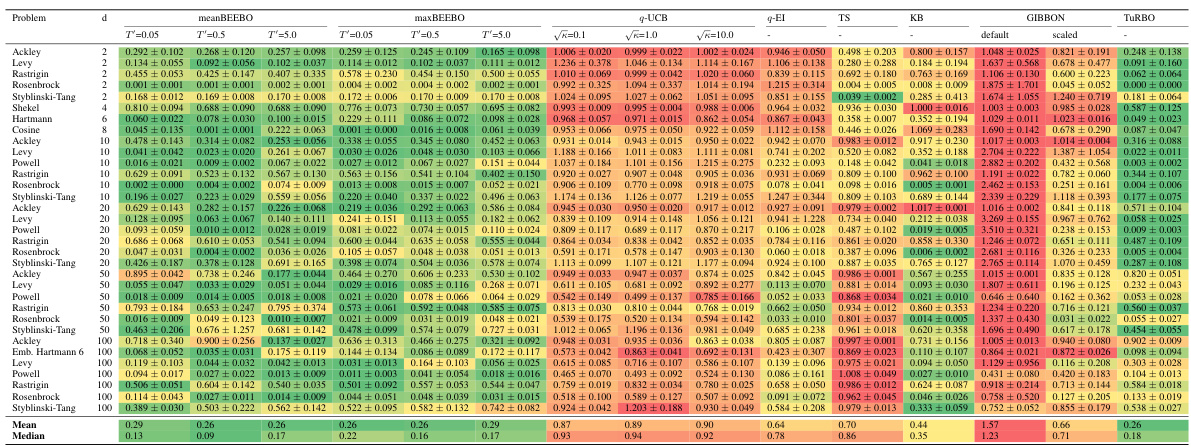

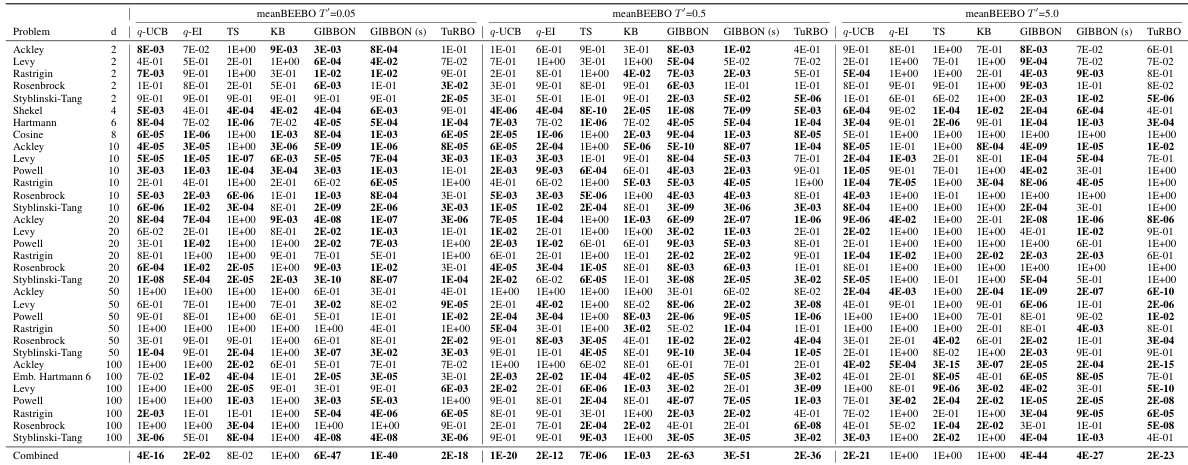

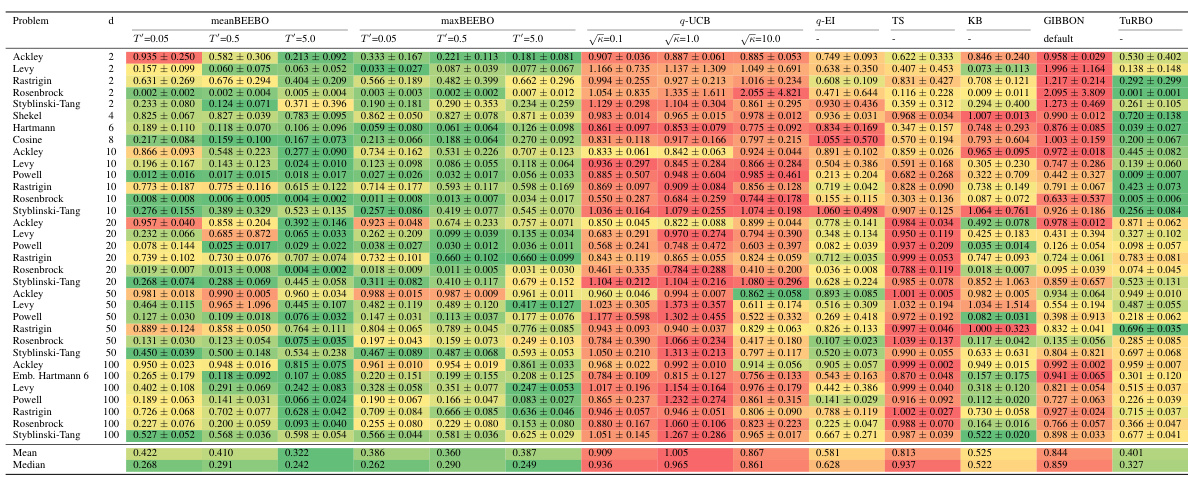

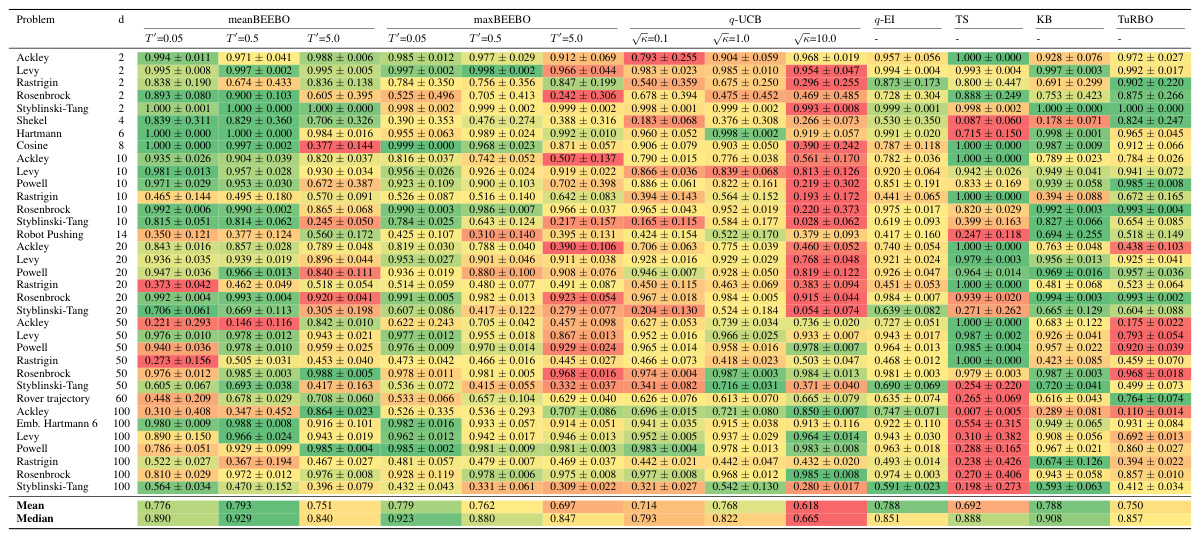

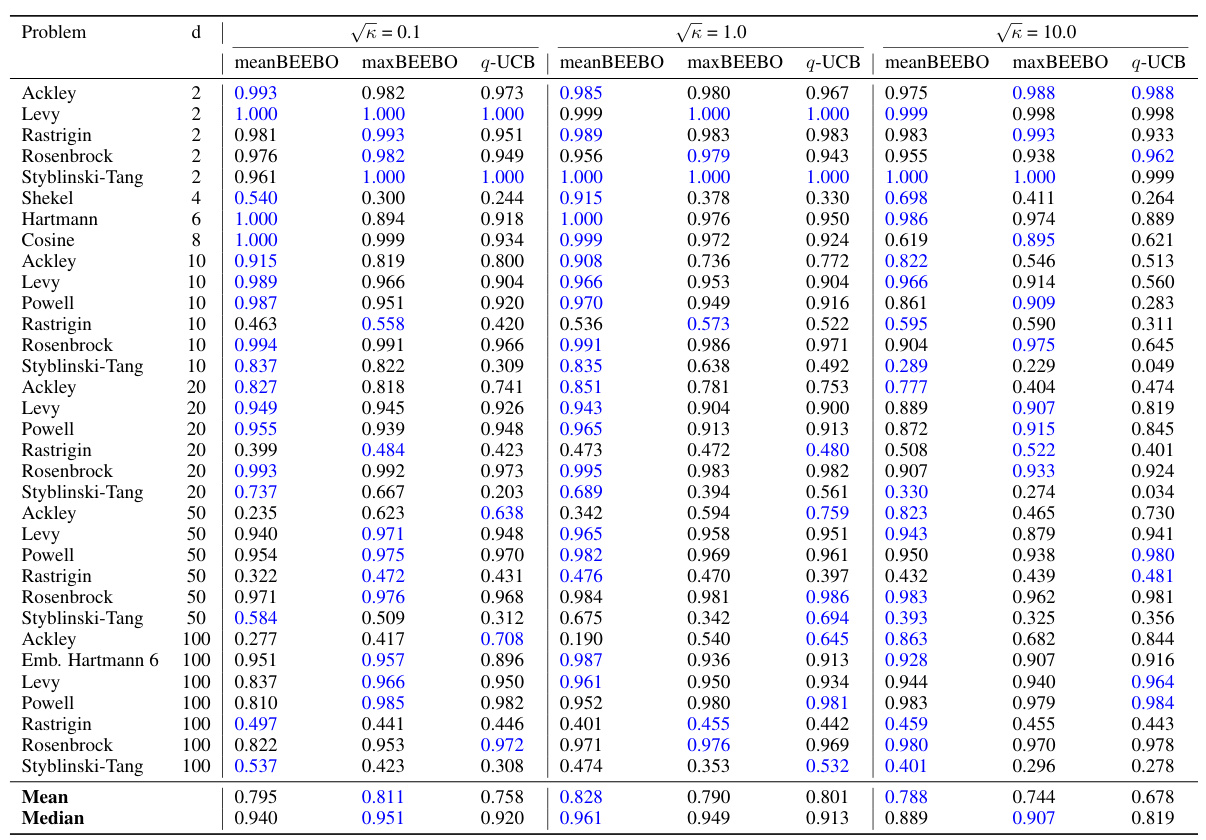

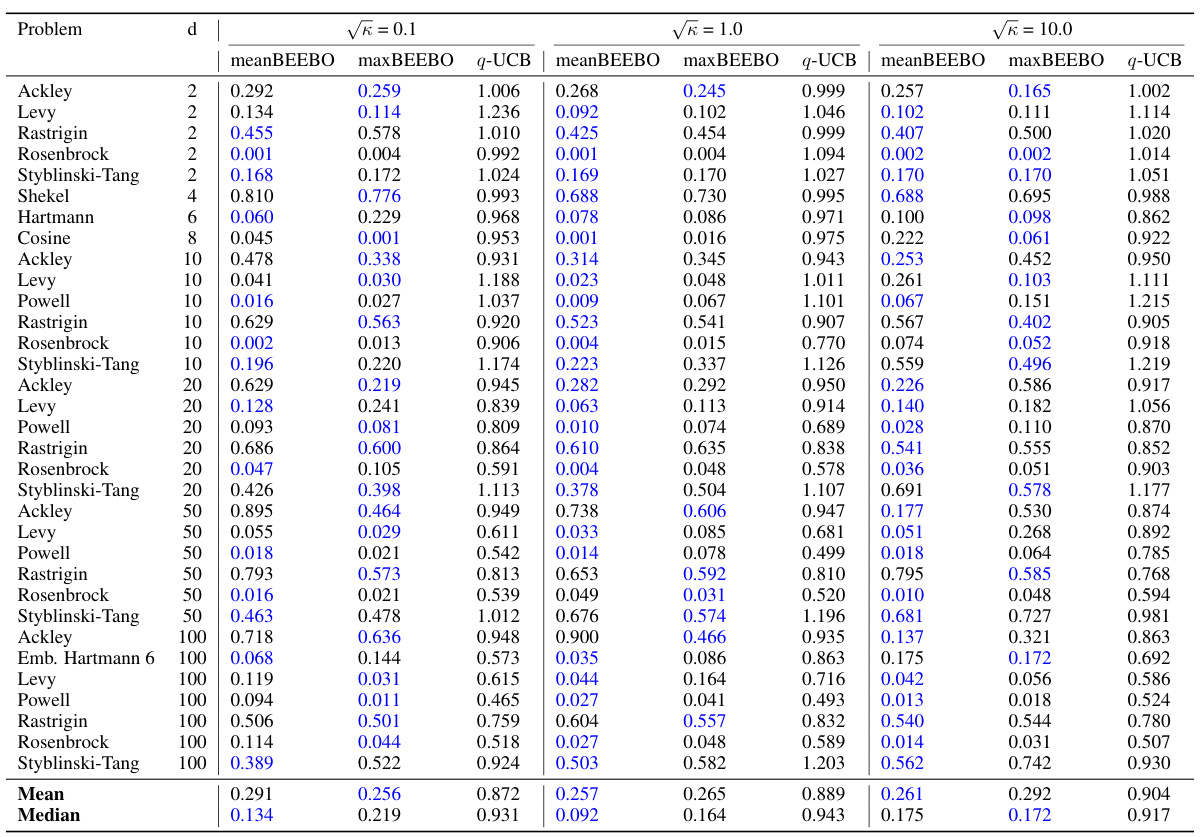

This table shows the highest observed value achieved after 10 rounds of Bayesian Optimization with a batch size of 100. The results are shown for different values of the exploration-exploitation parameter, κ, for both BEEBO and q-UCB. The best performance for each κ value is highlighted in blue. BEEBO’s hyperparameter, T’, is linked to κ (T’ = 1/(2√κ)). More detailed information, including full BO curves and statistical analysis, can be found in the appendix.

In-depth insights#

Batched Bayesian Opt#

Batched Bayesian Optimization (BBO) tackles the challenge of optimizing expensive black-box functions by evaluating multiple points concurrently. This approach contrasts with traditional sequential BO, significantly reducing overall optimization time, particularly valuable for computationally intensive tasks. Key challenges in BBO involve designing acquisition functions that effectively balance exploration and exploitation across multiple points simultaneously. While many existing methods use sampling-based approximations, which can be computationally expensive and might affect the explore-exploit balance, especially with large batch sizes, BBO strives for efficient and controllable methods that natively handle batches, avoiding the need for sampling-based approximations. A well-designed BBO method would allow for tunable exploration-exploitation trade-offs, handle heteroskedastic noise (uneven uncertainty across the input space) robustly, and generalize well across various problem settings and dimensions. The ultimate goal is to achieve a sample-efficient optimization process that leverages parallelism without sacrificing performance or controllability.

BEEBO Acquisition#

The BEEBO (Batched Energy-Entropy acquisition for Bayesian Optimization) acquisition function offers a novel approach to batched Bayesian Optimization. BEEBO inherently handles batches, unlike many existing methods that adapt single-point functions, avoiding approximations and sampling-based alternatives. Its core innovation lies in combining an exploration term (based on information gain, quantifying uncertainty reduction) and an exploitation term (using a softmax-weighted sum over function predictions). This allows for precise control of the explore-exploit trade-off via a single temperature hyperparameter (β). This controllability makes BEEBO adaptable to problems with heteroskedastic noise, which is demonstrated through experimental results. The analytical nature of BEEBO, particularly with Gaussian processes, facilitates efficient gradient-based optimization, avoiding the computational burden of Monte Carlo integration commonly found in other batch acquisition methods. BEEBO shows competitive performance, outperforming or matching other techniques across a variety of test problems and dimensions, suggesting its potential as a robust and scalable method for expensive, parallel optimization tasks.

Explore-Exploit Tradeoff#

The explore-exploit tradeoff is a central challenge in reinforcement learning and optimization algorithms. Exploration involves investigating uncertain areas of the search space to discover potentially better solutions, while exploitation focuses on refining already known good solutions. Finding the right balance is crucial; too much exploration can lead to wasted resources without significant improvements, while excessive exploitation may prevent discovering superior solutions hidden in unexplored regions. Many acquisition functions aim to manage this tradeoff, often through parameters that control the relative weight assigned to exploration versus exploitation. Effective strategies adapt this balance dynamically, giving more weight to exploration early in the process and gradually shifting toward exploitation as more information becomes available. This dynamic adjustment is key to efficiently finding high-quality solutions in complex search spaces. Advanced techniques, such as those incorporating uncertainty or risk aversion, further refine this tradeoff. Ultimately, the optimal balance depends on the specific problem and the available computational resources. Methods using single temperature hyperparameters offer a direct method to control this balance, providing more intuitive and manageable control than other strategies.

Heteroskedastic Noise#

The section on ‘Heteroskedastic Noise’ in this research paper is crucial because it addresses a significant limitation of many existing Bayesian Optimization (BO) methods. Standard BO methods often assume homoscedastic noise, meaning the variance of the noise is constant across the input space. However, real-world black-box functions often exhibit heteroscedasticity, where the noise level varies depending on the input. The paper investigates how the proposed Batched Energy-Entropy acquisition for BO (BEEBO) handles this challenging scenario. The experiments likely focus on a problem where the noise level is high near optima and low far from them. This is important because it demonstrates BEEBO’s robustness and highlights its ability to prioritize exploration in regions with low uncertainty, even when dealing with non-constant noise levels. By showcasing competitive performance on this specific test case, the research provides a stronger argument for the use of BEEBO over traditional BO methods when the noise is heteroskedastic. This is because traditional methods may struggle to reliably identify true optima due to noisy measurements at certain inputs.

BEEBO Limitations#

The BEEBO algorithm, while offering a novel approach to batched Bayesian Optimization, is not without limitations. Computational cost remains a significant concern, especially for high-dimensional problems. The method’s reliance on Gaussian processes, while convenient for analytical tractability, introduces assumptions about the function’s smoothness that may not always hold true in real-world applications. Although BEEBO offers a hyperparameter for controlling explore-exploit trade-off, optimal hyperparameter selection still requires careful consideration and potentially additional tuning effort. Finally, while BEEBO demonstrates robustness to heteroskedastic noise, its performance under extreme noise levels or in scenarios with very few data points may not be competitive with alternative methods.

More visual insights#

More on figures

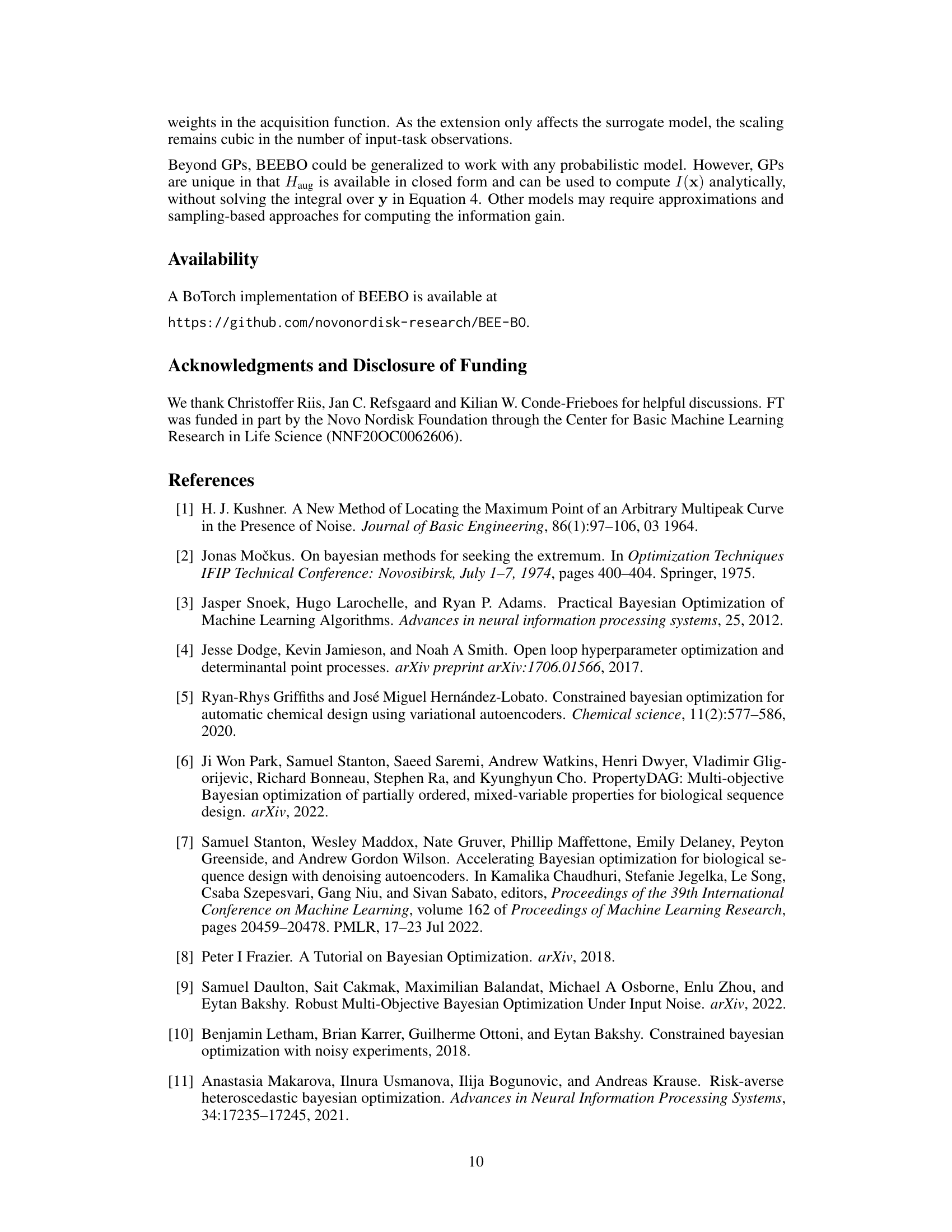

This figure compares the performance of BEEBO and q-UCB on a 2D Branin function with three global optima under both heteroskedastic and homoskedastic noise. The figure shows the mean distance of the acquired points to each of the three optima over ten rounds of Bayesian optimization. The results indicate that BEEBO is risk-averse under heteroskedastic noise, preferring to acquire points near the low-noise optimum, while q-UCB shows no such preference and behaves similarly under both noise conditions.

This figure compares the performance of q-UCB and BEEBO on the Ackley function with a batch size of 100. The background shows a Gaussian process (GP) surrogate model initialized with 100 random data points. The top row displays the acquisition function values for q-UCB with two different exploration parameters (κ = 0.1 and κ = 100). The bottom row shows the acquisition function values for BEEBO with two different temperature parameters (T’ = 0.05 and T’ = 50). The visualization demonstrates that q-UCB’s explore-exploit balance is not easily controlled with large batches, whereas BEEBO provides a mechanism for controlling this tradeoff via the temperature parameter.

This figure compares the performance of two acquisition functions, q-UCB and BEEBO, in a Bayesian Optimization setting with a batch size of 100. The background shows a Gaussian process (GP) surrogate model fitted to 100 initial random points sampled from the Ackley function. The top row displays the acquisition function values for q-UCB using two different exploration parameters (κ = 0.1 and κ = 100). The bottom row shows the same for BEEBO, using two different temperature parameters (T’ = 0.05 and T’ = 50). The figure highlights that q-UCB does not offer direct control of exploration and exploitation with large batches, whereas BEEBO does, allowing for a more nuanced balance between exploration and exploitation by tuning the temperature parameter.

This figure compares the performance of q-UCB and BEEBO acquisition functions in a Bayesian Optimization (BO) setting. Both algorithms aim to find the maximum of the Ackley function. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model fitted to 100 randomly sampled points of the function. The plots demonstrate how q-UCB’s explore-exploit balance is sensitive to the choice of its hyperparameter κ, resulting in very different acquisition point distributions. In contrast, BEEBO offers more stable control over explore-exploit using its hyperparameter T’, allowing for consistent and controllable acquisition strategies even with large batches (Q=100).

This figure compares the performance of two acquisition functions, q-UCB and BEEBO, for batched Bayesian Optimization on the Ackley function. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model fitted to 100 initial random data points. The top row shows the acquisition function values for q-UCB with two different exploration parameters (κ = 0.1 and κ = 100), illustrating its inability to control the explore-exploit trade-off effectively with large batches (Q=100). The bottom row shows the acquisition function values for BEEBO, demonstrating that it maintains control of the explore-exploit balance through a temperature hyperparameter (T’ = 0.05 and T’ = 50). The plots visually represent how the algorithms select new evaluation points in parallel across the input space, emphasizing the difference in explore-exploit trade-offs.

This figure compares the performance of two acquisition functions, q-UCB and BEEBO, for Bayesian Optimization (BO) with large batch sizes. The background shows a Gaussian process (GP) surrogate model fitted to 100 randomly sampled points of the Ackley function. The top two panels illustrate q-UCB’s performance with different exploration-exploitation parameters (κ). The bottom two panels show BEEBO’s performance with different temperature parameters (T’). The results highlight BEEBO’s ability to better control the explore-exploit trade-off, even with large batches.

This figure compares the performance of q-UCB and BEEBO on the Ackley function with a batch size of 100. The background shows a Gaussian process (GP) surrogate model initialized with 100 random data points. The top row demonstrates q-UCB’s inability to control the exploration-exploitation trade-off with varying κ values (0.1 and 100). The bottom row illustrates BEEBO’s ability to control this trade-off using a single temperature hyperparameter T’ (0.05 and 50). The visualization highlights how BEEBO achieves a better balance between exploration and exploitation compared to q-UCB, especially with large batch sizes.

This figure compares the performance of the q-UCB algorithm and the proposed BEEBO algorithm in a Bayesian Optimization setting with a large batch size (Q=100). The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model fitted to 100 randomly sampled points from the Ackley function. The top two panels display the acquisition function values for q-UCB with two different exploration-exploitation parameters (κ = 0.1 and κ = 100), demonstrating a lack of fine-grained control over the explore-exploit trade-off. The bottom two panels show the BEEBO acquisition function values with two different temperature parameters (T’=0.05 and T’=50), highlighting BEEBO’s ability to precisely control the explore-exploit balance even with a large batch size.

This figure compares the performance of two acquisition functions, q-UCB and BEEBO, for batched Bayesian Optimization on the Ackley function. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model fitted to 100 randomly sampled points of the Ackley function. Two versions of q-UCB are shown, one with a high exploration parameter (κ = 100) and one with a high exploitation parameter (κ = 0.1). Similarly, BEEBO is run with two different temperature parameters (T’= 0.05 and T’= 50), controlling the explore-exploit balance. The batch size is Q = 100. The figure visually demonstrates that q-UCB’s explore-exploit trade-off is difficult to control with large batches, unlike BEEBO which offers more control via the temperature parameter.

This figure compares the performance of q-UCB and BEEBO on the Ackley function with a batch size of 100. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model initialized with 100 random points. The top row demonstrates q-UCB’s acquisition behavior using two different exploration-exploitation trade-off parameters (κ = 0.1 and κ = 100). The bottom row shows BEEBO’s acquisition behavior, also using two different temperature parameters (T’ = 0.05 and T’ = 50). The figure highlights BEEBO’s ability to better control the explore-exploit trade-off, especially with large batches, unlike q-UCB.

This figure compares the performance of q-UCB and BEEBO on the Ackley function with a batch size of 100. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model initialized with 100 random data points. The top row demonstrates q-UCB’s behavior with two different exploration-exploitation parameters (κ = 0.1 and κ = 100). The bottom row shows BEEBO’s behavior with two different temperature parameters (T’= 0.05 and T’= 50). The figure highlights that q-UCB struggles to control the explore-exploit balance effectively with large batches, while BEEBO offers a more nuanced control.

This figure compares the performance of the q-UCB algorithm and the proposed BEEBO algorithm for batched Bayesian Optimization on the Ackley function. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model trained on 100 randomly sampled points of the Ackley function. The top two panels demonstrate the exploration-exploitation trade-off for q-UCB using two different hyperparameters (κ = 0.1 and κ = 100). The bottom two panels show the performance of BEEBO algorithm with two different hyperparameters (T’= 0.05 and T’= 50). The figure highlights that q-UCB struggles to control the exploration-exploitation trade-off when using large batches (Q=100), while BEEBO effectively manages it. The batch size is 100 for both algorithms in this example.

This figure compares the performance of q-UCB and BEEBO on the Ackley function. It shows that q-UCB’s explore-exploit balance is difficult to control with large batches, while BEEBO provides a better mechanism for controlling this balance using a single temperature hyperparameter. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model, illustrating the uncertainty in the function approximation.

This figure compares the performance of the q-UCB algorithm and the proposed BEEBO algorithm for batched Bayesian Optimization. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model fitted to 100 randomly sampled points of the Ackley function. Two runs of q-UCB are shown, one with a high exploration parameter (κ = 100) and one with a low exploration parameter (κ = 0.1). Similarly, two runs of BEEBO are displayed, using different temperature hyperparameters (T’ = 0.05 and T’ = 50) to control the exploration-exploitation balance. The figure highlights that q-UCB’s explore-exploit behavior is difficult to control with large batch sizes, unlike BEEBO, which demonstrates a better ability to manage exploration and exploitation through its temperature parameter.

This figure compares the performance of q-UCB and BEEBO on the Ackley function with a batch size of 100. The background shows a Gaussian process (GP) surrogate model initialized with 100 randomly sampled points. The top row displays the acquisition function values for q-UCB with two different exploration parameters (κ = 0.1 and κ = 100). The bottom row shows the acquisition function values for BEEBO with two different temperature parameters (T’ = 0.05 and T’ = 50). The figure demonstrates that q-UCB’s explore-exploit balance is not easily controlled with large batches, unlike BEEBO, where the balance can be adjusted via the temperature hyperparameter.

This figure compares the exploration-exploitation trade-off of two acquisition functions: q-UCB and BEEBO. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model fitted to 100 randomly sampled points from the Ackley function. The two acquisition functions are then used to select further points for evaluation. q-UCB, with its parameter κ set to 0.1 (left) and 100 (right), shows poor control over exploration-exploitation for large batches (Q=100). In contrast, BEEBO, with its temperature parameter T’ set to 0.05 (left) and 50 (right), demonstrates tight control of this trade-off, clearly separating exploration and exploitation regions.

This figure compares the performance of q-UCB and BEEBO on the Ackley function with a batch size of 100. The background shows a Gaussian process (GP) surrogate model initialized with 100 random points. The top row shows the acquisition function values for q-UCB with exploration parameters (κ) of 0.1 and 100, demonstrating its inability to control the explore-exploit trade-off with large batches. The bottom row shows BEEBO’s acquisition function values with temperature parameters (T’) of 0.05 and 50, highlighting its ability to tightly control this trade-off. The different colors represent different acquisition function values.

This figure compares the performance of the q-UCB algorithm and the proposed BEEBO algorithm on the Ackley function with a batch size of 100. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model initialized with 100 random data points. The top row demonstrates that q-UCB, a commonly used batched Bayesian Optimization acquisition function, struggles to control the exploration-exploitation trade-off when using large batch sizes. Different values of the exploration parameter (κ) result in vastly different exploration patterns. The bottom row showcases that BEEBO effectively controls this trade-off using a single temperature parameter (T’). Different values of T’ provide a more balanced exploration and exploitation trade-off.

This figure compares the performance of two acquisition functions, q-UCB and BEEBO, in a Bayesian Optimization setting with a batch size of 100. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model fitted to 100 randomly sampled points from the Ackley function. The top row displays the acquisition functions’ suggestions for exploration and exploitation using two different hyperparameter settings (κ for q-UCB and T’ for BEEBO) to highlight the explore-exploit trade-off. q-UCB struggles to control this trade-off effectively with large batches while BEEBO allows for much finer tuning by adjusting the T’ parameter.

This figure compares the performance of q-UCB and BEEBO on the Ackley function with a batch size of 100. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model initialized with 100 random points. The top row demonstrates q-UCB’s behavior with a low exploration rate (κ=0.1, exploiting) and high exploration rate (κ=100, exploring). The bottom row shows BEEBO’s performance with a low temperature (T’=0.05, exploiting) and high temperature (T’=50, exploring). The figure highlights that q-UCB struggles to control the explore-exploit trade-off with large batch sizes, unlike BEEBO.

This figure compares the performance of q-UCB and BEEBO on the Ackley function with a batch size of 100. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model initialized with 100 randomly sampled points. The top panels display the acquisition points selected by q-UCB using two different exploration parameters (κ = 0.1 and κ = 100). The bottom panels show the acquisition points selected by BEEBO using two different temperature parameters (T’ = 0.05 and T’ = 50). The figure demonstrates that, unlike BEEBO, q-UCB does not allow for easy control of the exploration-exploitation trade-off with large batch sizes. The difference in explore-exploit balance between the two methods is clearly illustrated.

This figure compares the performance of q-UCB and BEEBO on the Ackley function with a batch size of 100. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model initialized with 100 random points. The top row displays the acquisition function values for q-UCB with two different exploration parameters (κ = 0.1 and κ = 100), illustrating a lack of explore-exploit control. The bottom row shows BEEBO’s acquisition function values with two temperature parameters (T’ = 0.05 and T’ = 50), highlighting its ability to control the explore-exploit trade-off. The different colors represent different acquisition suggestions.

This figure compares the performance of q-UCB and BEEBO on the Ackley function with a batch size of 100. It illustrates how q-UCB’s explore-exploit balance is difficult to control with large batches, as demonstrated by the vastly different exploration patterns observed using κ=0.1 and κ=100. In contrast, BEEBO demonstrates tight control of explore-exploit trade-off using a single temperature hyperparameter, with similar patterns observed using T’=0.05 and T’=50. The background shows the GP surrogate model of the Ackley function initialized with 100 random points, providing context for the acquisition function’s behaviour.

This figure compares the performance of two batch Bayesian optimization (BO) acquisition functions: q-UCB and BEEBO. It shows how q-UCB struggles to balance exploration and exploitation effectively, particularly with large batches. The background shows a Gaussian process (GP) surrogate model fitted to data. The plots illustrate that q-UCB with a low exploration parameter (κ = 0.1) focuses more on exploitation (finding the maximum), missing a significant area of the search space with high potential values. Conversely, q-UCB with a high exploration parameter (κ = 100) explores more extensively, but inefficiently. In contrast, BEEBO, with its temperature parameter (T’), can smoothly control the balance between exploration and exploitation across a wider range. This allows it to effectively cover promising regions without wasting computational effort on overly broad explorations.

This figure compares the performance of q-UCB and BEEBO on the Ackley function. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model initialized with 100 random data points. Two versions of q-UCB are shown, one with a high exploration parameter (κ=100) and one with low exploration (κ=0.1). Two versions of BEEBO are also shown with different temperature parameters (T’=0.05 and T’=50), which control the exploration-exploitation trade-off. The figure demonstrates that q-UCB’s exploration-exploitation balance is not easily controlled with large batch sizes (Q=100), while BEEBO allows for better control via its temperature parameter.

This figure compares the performance of two Bayesian Optimization (BO) acquisition functions: q-UCB and BEEBO. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model fitted to 100 randomly sampled points of the Ackley function. The top row demonstrates that q-UCB’s exploration-exploitation balance is poorly controlled with large batch sizes (Q=100), resulting in very different acquisition patterns for different values of the hyperparameter κ. The bottom row illustrates that BEEBO provides tight control over exploration-exploitation via its temperature hyperparameter T’, allowing for more consistent results.

This figure compares the performance of two Bayesian Optimization (BO) acquisition functions, q-UCB and BEEBO, on the Ackley test function. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model initialized with 100 random data points. The top row displays the acquisition suggestions from q-UCB with different explore-exploit parameters (κ = 0.1 and κ = 100). The bottom row shows the acquisition suggestions from BEEBO, also with different explore-exploit parameters (T’ = 0.05 and T’ = 50). The batch size (Q) is 100 for all experiments. The figure highlights that BEEBO, unlike q-UCB, allows for explicit control of exploration vs. exploitation, even with large batches. The different colors represent the points acquired in each iteration.

This figure compares the performance of two acquisition functions, q-UCB and BEEBO, in a Bayesian Optimization (BO) scenario with a batch size of 100. The background shows a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model fitted to 100 initial random points of the Ackley function. q-UCB, a commonly used acquisition function for batched BO, is shown with two different exploration parameters (κ = 0.1 and κ = 100). BEEBO, the novel acquisition function proposed in the paper, is shown with two different temperature hyperparameters (T’= 0.05 and T’= 50). The figure demonstrates that q-UCB’s exploration-exploitation trade-off is difficult to control with large batches, whereas BEEBO allows for more precise control of this trade-off through its temperature hyperparameter.

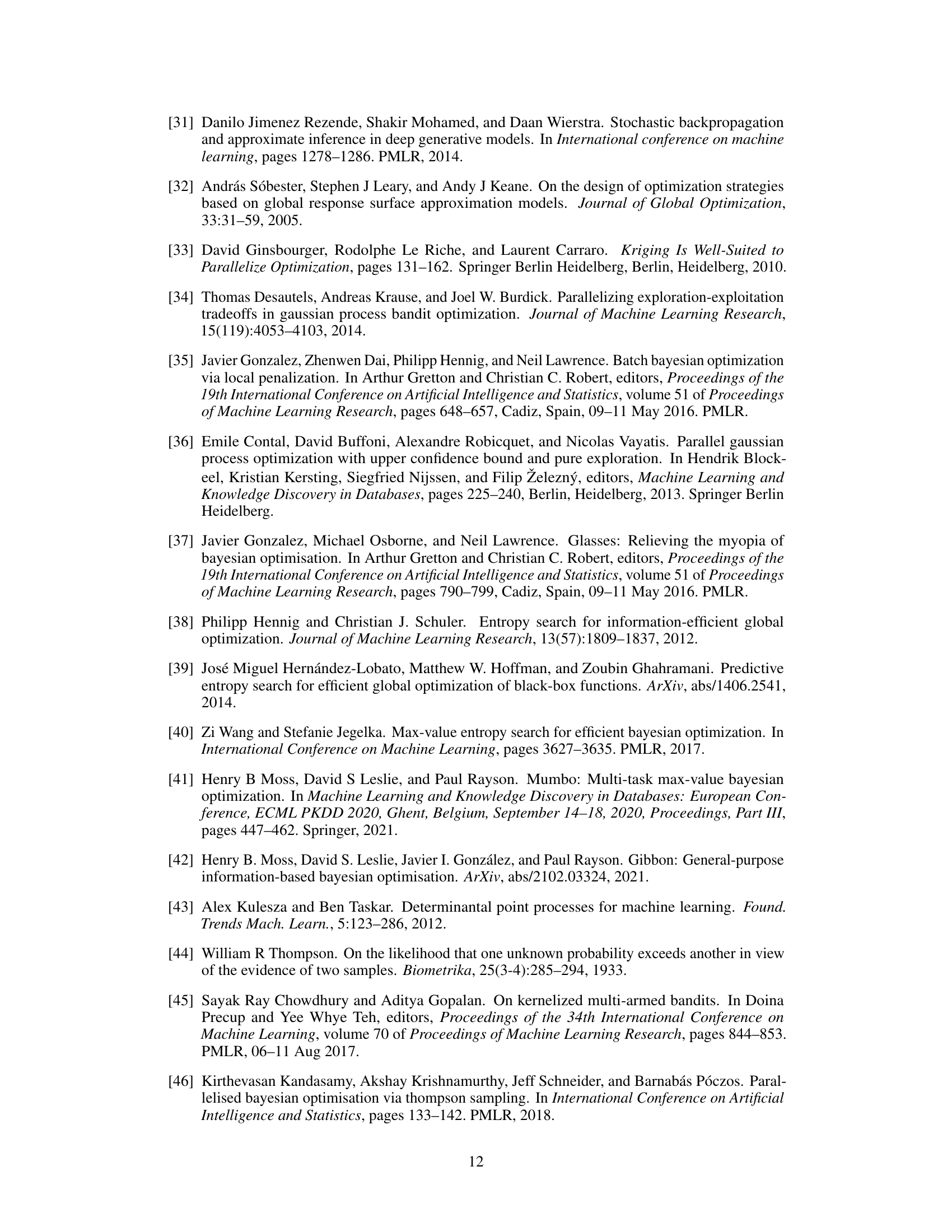

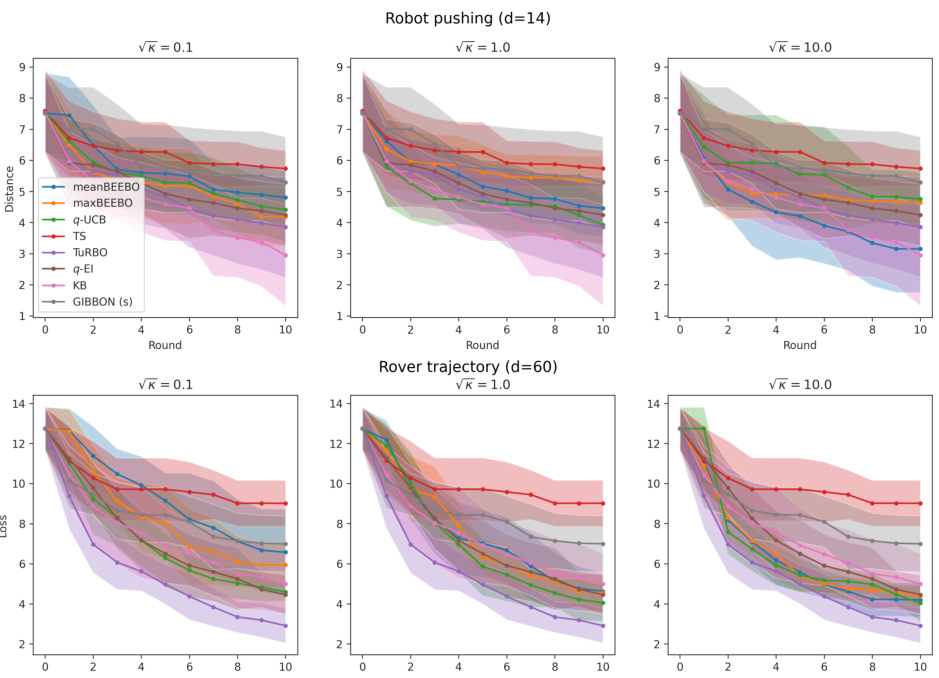

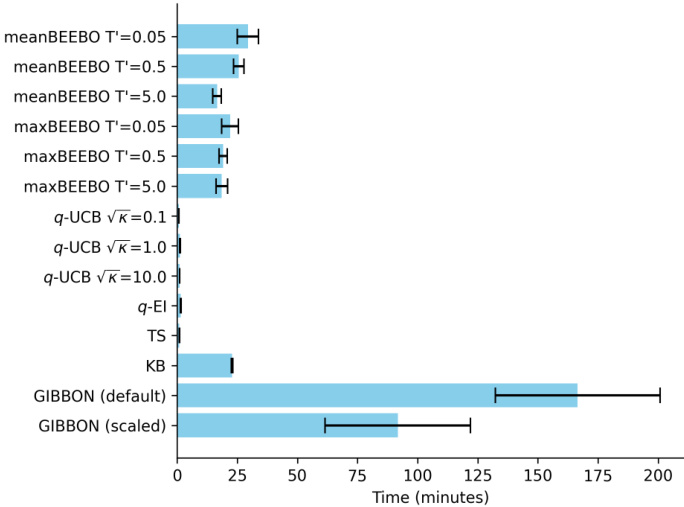

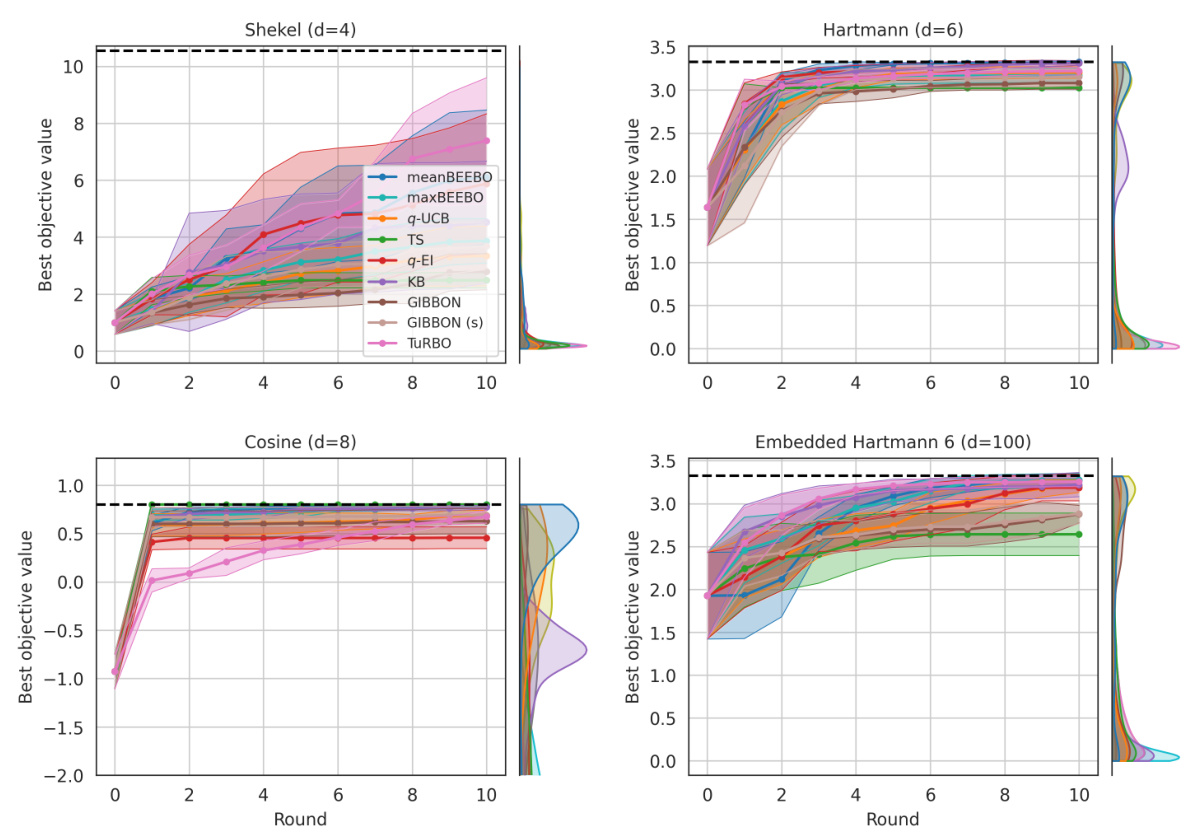

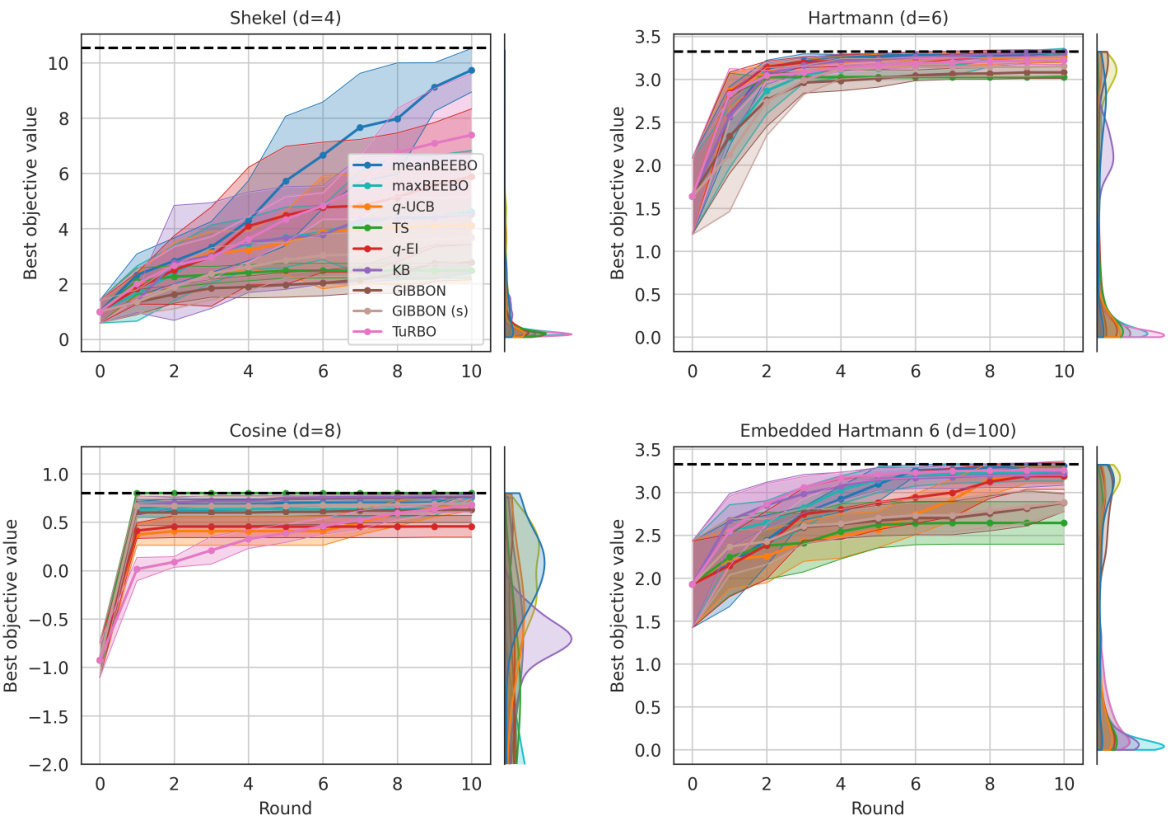

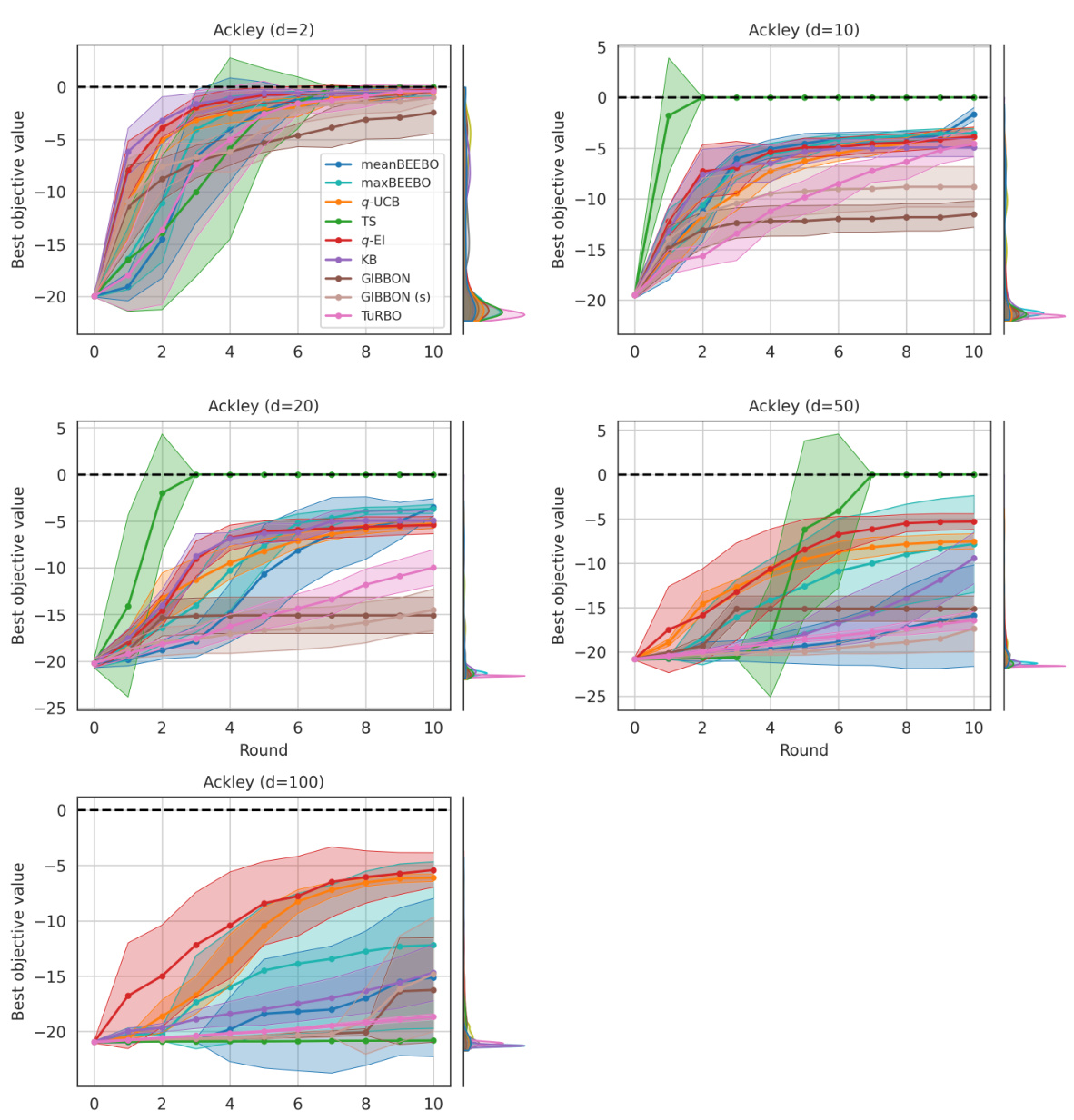

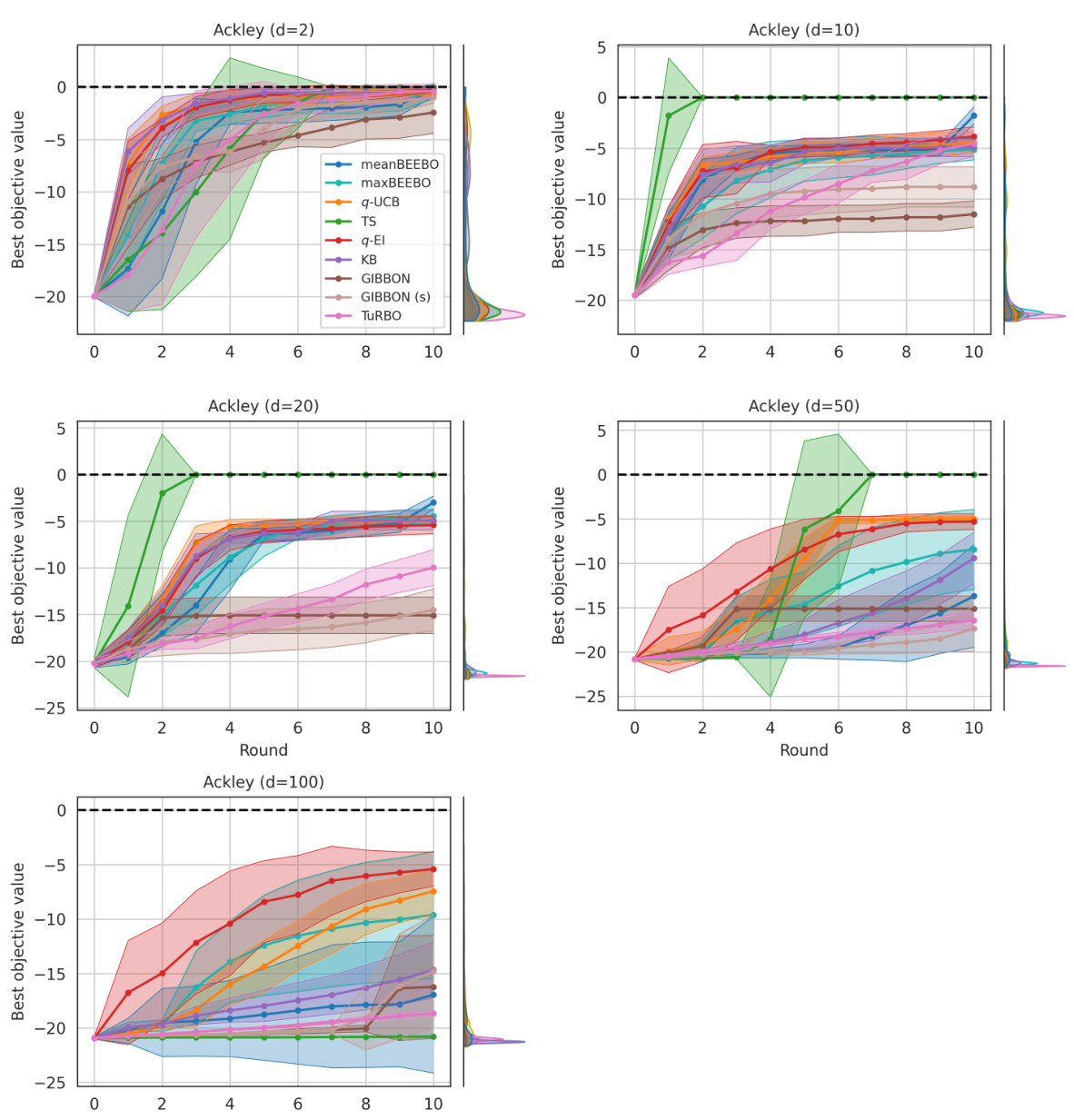

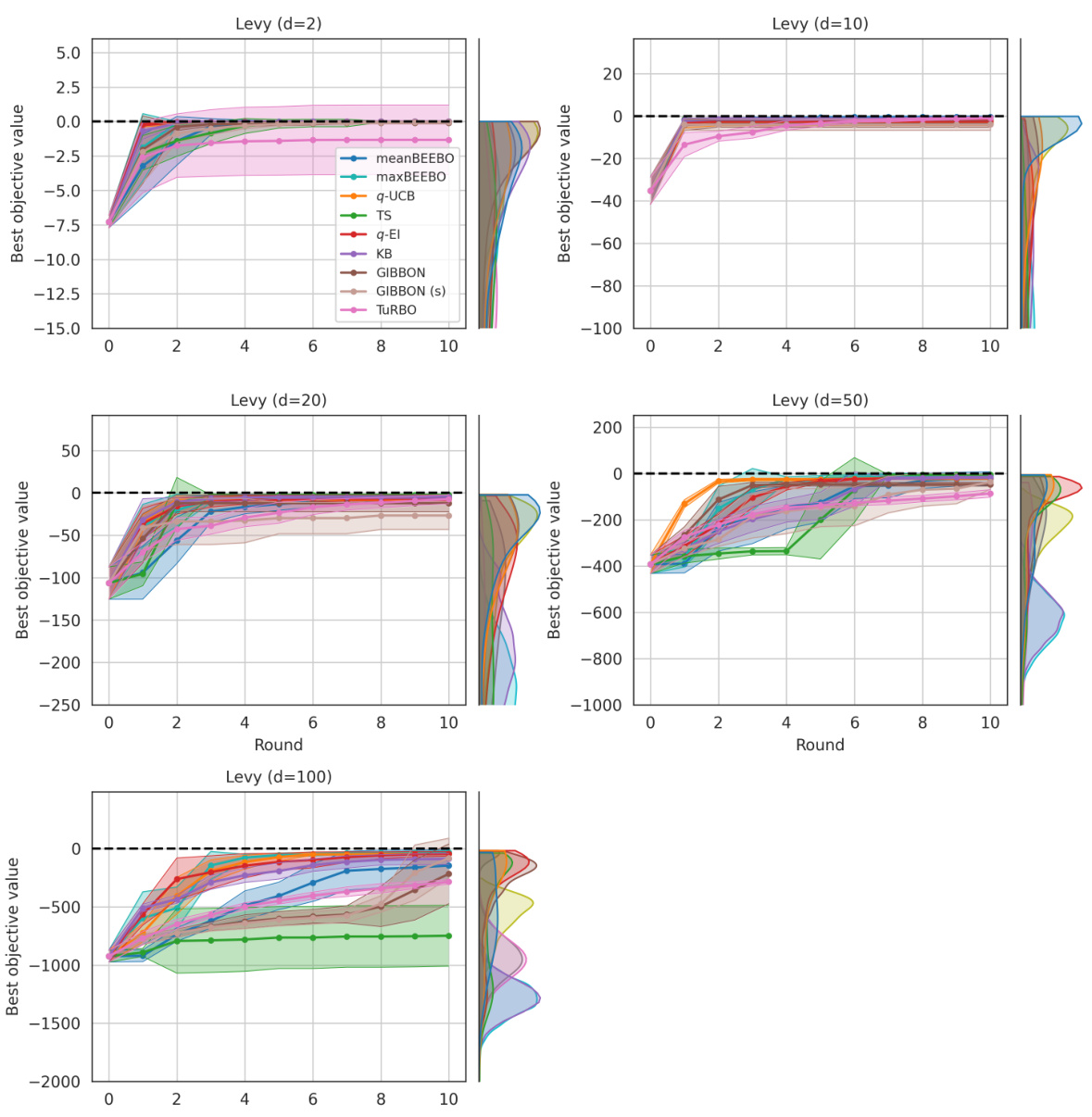

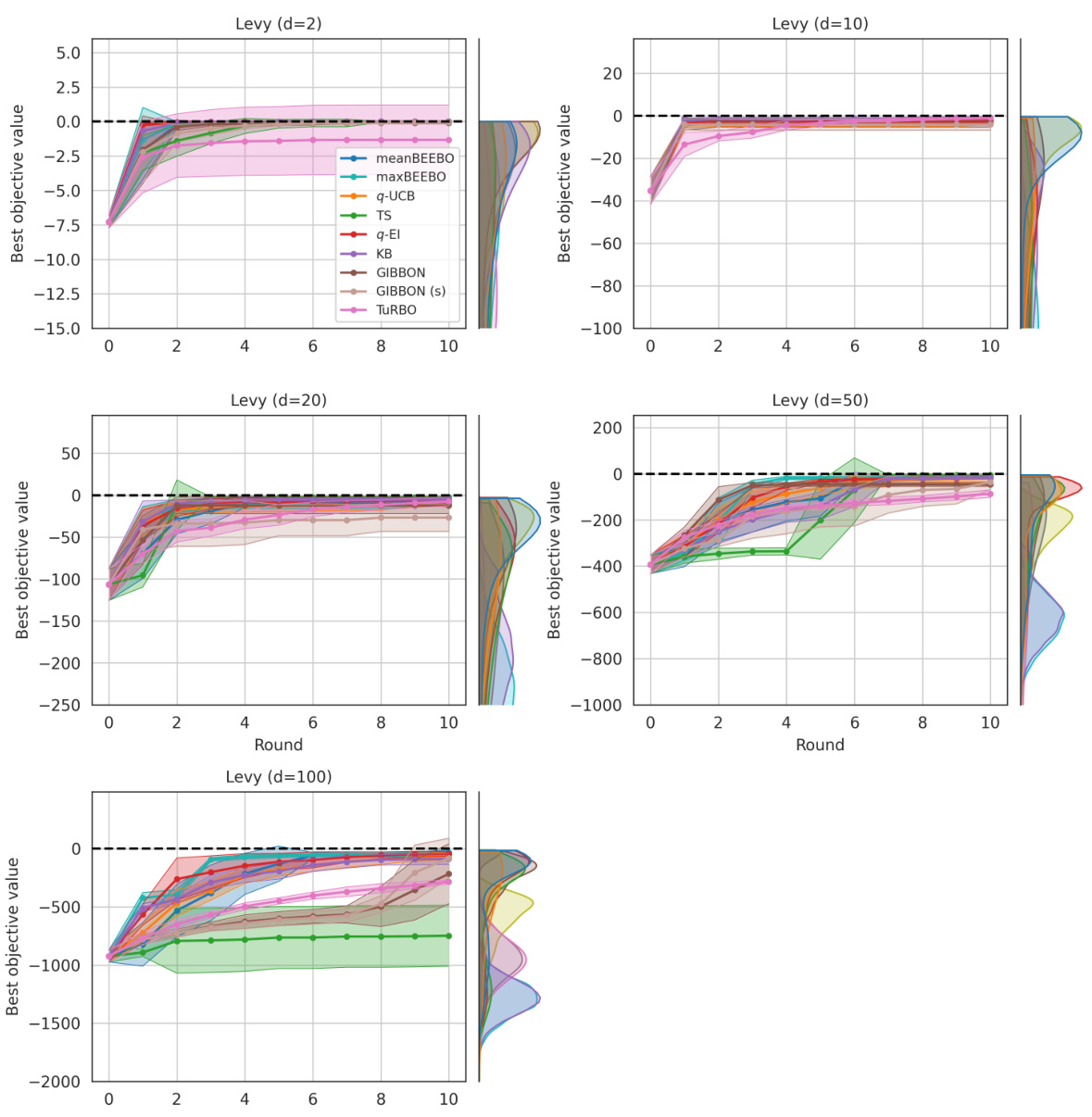

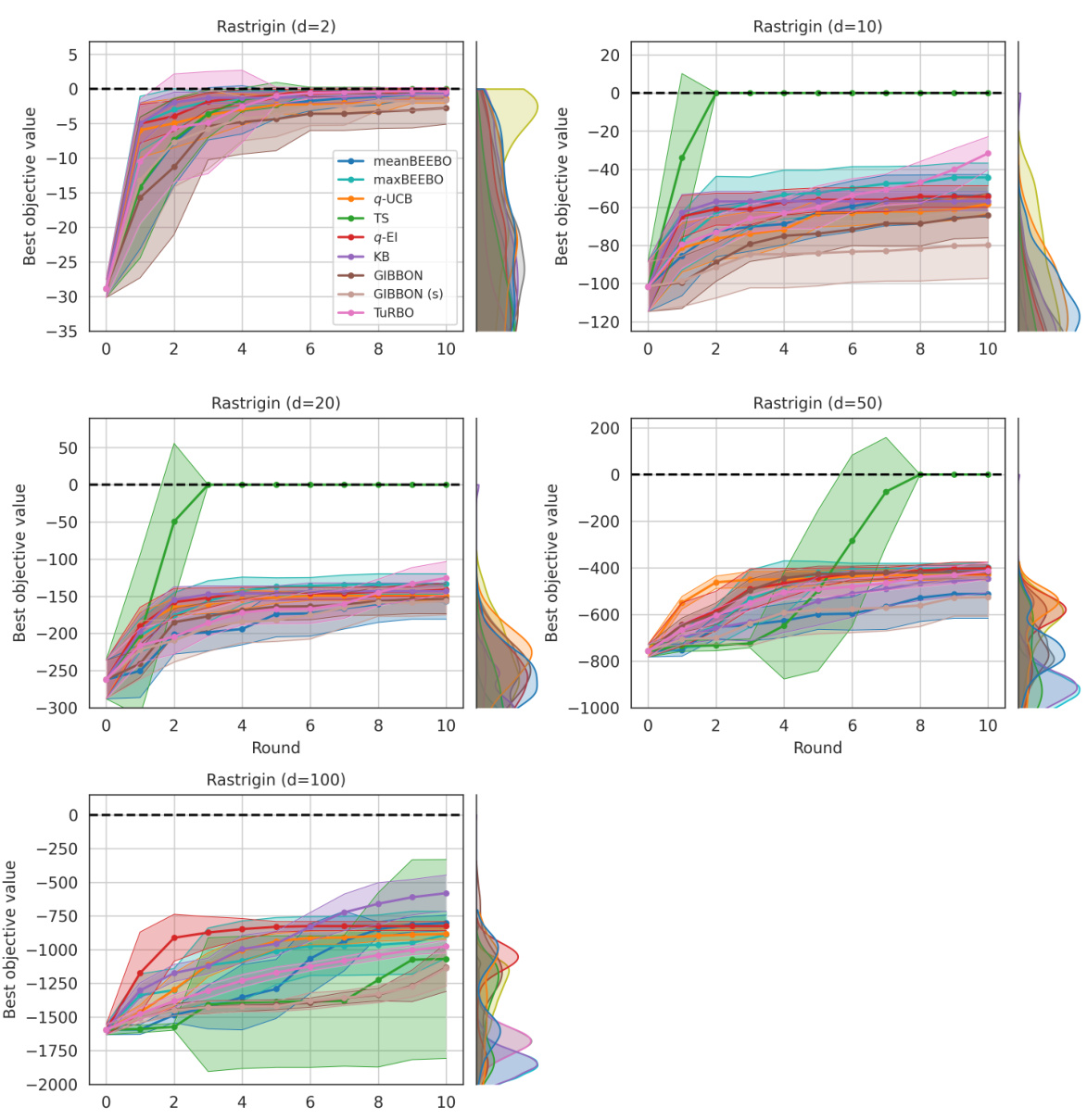

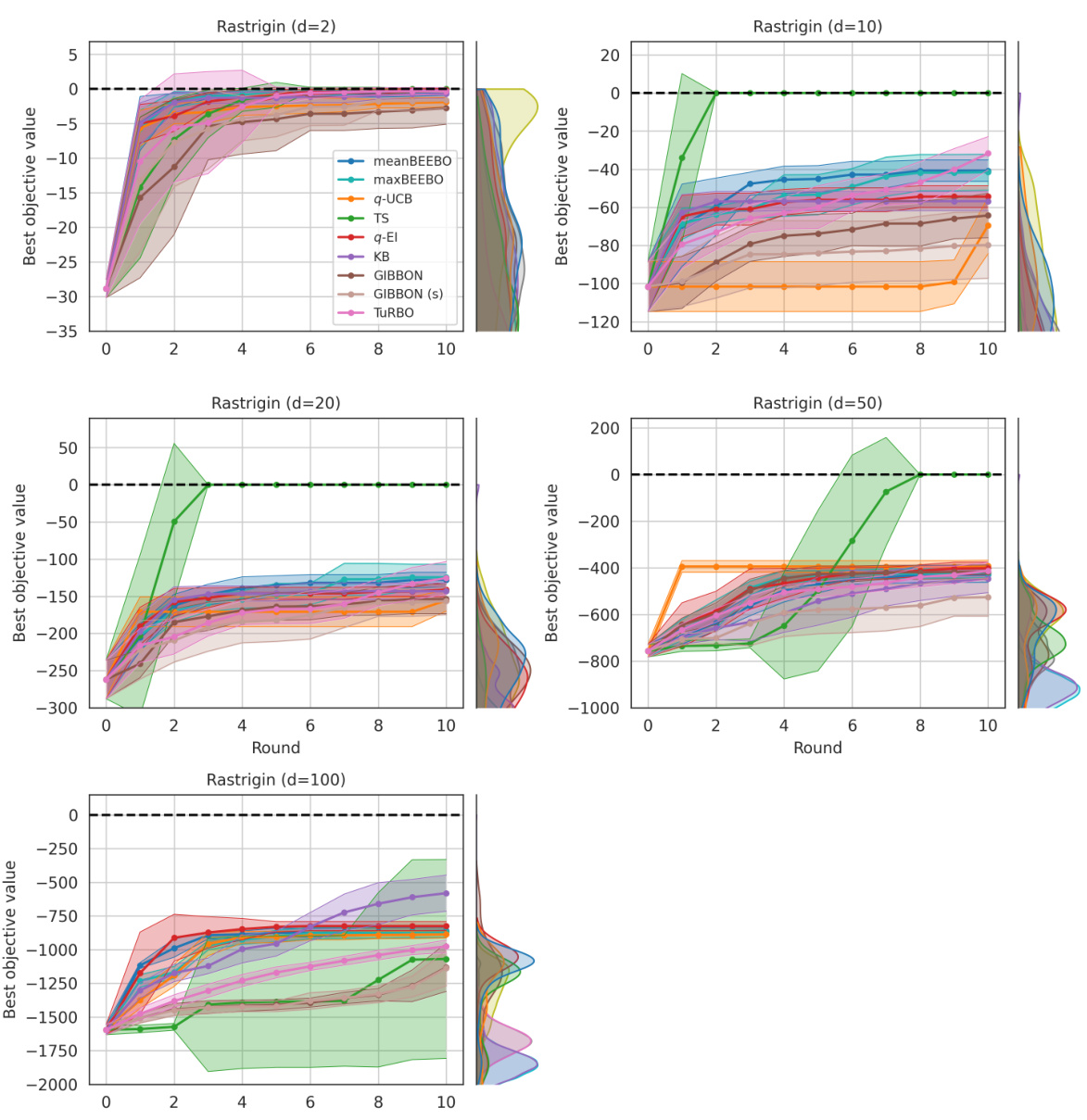

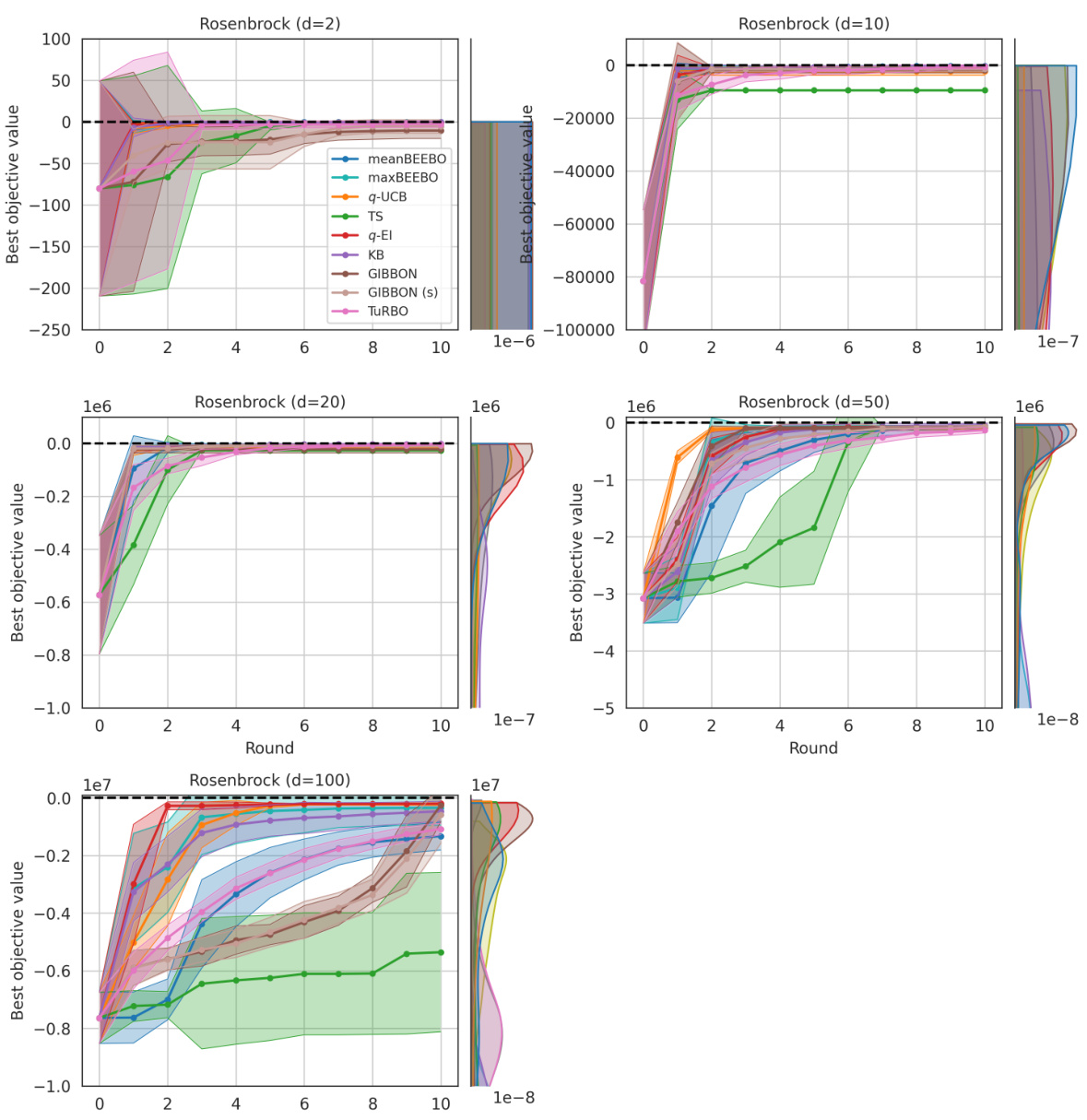

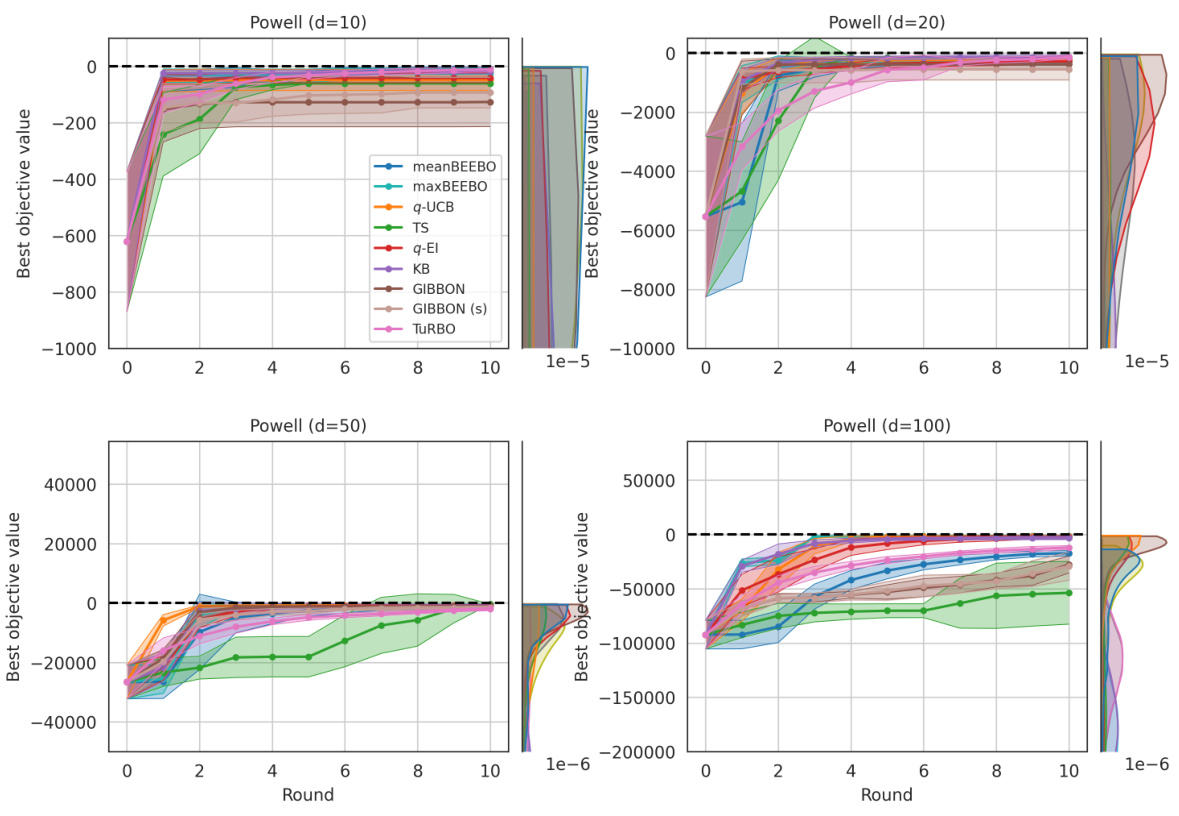

This figure shows the results of Bayesian Optimization experiments on two control problems: 14-dimensional robot arm pushing and 60-dimensional rover trajectory planning. The experiment was conducted 10 times for each method (meanBEEBO, maxBEEBO, q-UCB, TS, q-EI, KB, GIBBON, GIBBON (scaled), and TuRBO). The y-axis represents the performance metric (distance for robot pushing and navigation loss for rover trajectory), while the x-axis represents the optimization round. The shaded area signifies the standard deviation across those 10 runs for each method. This visualization demonstrates the relative performance of various Bayesian Optimization strategies in high-dimensional settings over multiple repetitions, offering a comparison of their convergence and stability.

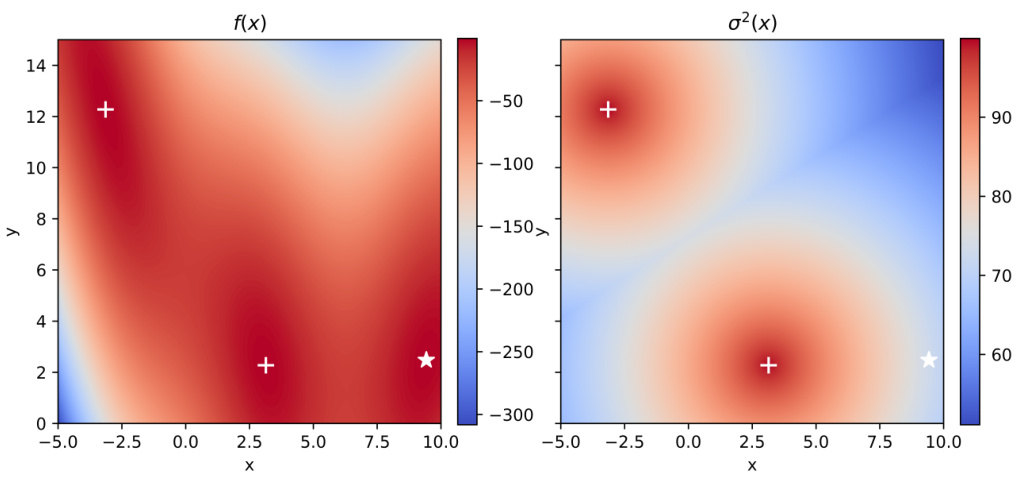

This figure shows the Branin function with added heteroskedastic noise. The left panel displays the Branin function’s surface, while the right panel shows the noise level (σ²(x)). The noise level is maximal at optima 2 and 3, decreasing exponentially with the distance from any of these optima. Optimum 1 has no added noise maximum.

This figure shows the results of Bayesian optimization experiments on two control problems: a 14-dimensional robot arm pushing task and a 60-dimensional rover trajectory planning task. The performance of several Bayesian optimization methods, including meanBEEBO, maxBEEBO, q-UCB, Thompson Sampling, q-EI, Kriging Believer, GIBBON (default), GIBBON (scaled), and TuRBO, are compared across 10 optimization rounds. The plot visually demonstrates the optimization progress over rounds, allowing a comparison of the efficiency and exploration-exploitation balance of different algorithms. The version of GIBBON with scaled batches is labeled as GIBBON(s).

More on tables

This table presents the highest observed objective function values after 10 rounds of Bayesian Optimization with a batch size of 100. It compares the performance of meanBEEBO and maxBEEBO against q-UCB across three different exploration-exploitation trade-off settings (controlled by the hyperparameter κ). The best result for each κ value is highlighted. The table also notes where to find more detailed results (full BO curves, confidence intervals, and statistical tests).

This table presents the highest observed objective function values after 10 rounds of Bayesian Optimization (BO) using different methods. The batch size (Q) is fixed at 100. The table compares the performance of the proposed BEEBO algorithm against the q-UCB algorithm for three different exploration-exploitation trade-off settings represented by the parameter κ (kappa). BEEBO’s hyperparameter T’ is adjusted to maintain a consistent trade-off with q-UCB across different values of κ. The best observed values for each setting are highlighted in blue. Additional details, including full BO curves, confidence intervals, and statistical tests, can be found in the appendix.

This table presents the results of Bayesian Optimization (BO) experiments comparing the performance of BEEBO and q-UCB on various test problems. It shows the highest observed objective function value achieved after 10 rounds of BO for different values of the exploration-exploitation hyperparameter (κ for q-UCB, T’ for BEEBO). The best performance for each κ value is highlighted in blue. Additional details, including complete BO curves, confidence intervals and statistical test results, are referenced.

This table presents the highest observed objective function values after 10 rounds of Bayesian Optimization (BO) for different algorithms and configurations. The results are shown for various test functions with different dimensions, and different exploration-exploitation parameters (κ for q-UCB, T’ for BEEBO). The best-performing method for each parameter setting is highlighted in blue. The table also references additional details provided in the appendix (full BO curves, confidence intervals, and statistical tests).

Full paper#