↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Manipulating articulated objects in real images is a core challenge in computer vision and robotics. Current methods often fail or generate artifacts, especially when dealing with complex objects or novel views. This paper focuses on addressing the issue of manipulating articulated objects in real images. Existing image editing techniques struggle with this due to their reliance on directly editing 2D images or relying on precise 3D models which are difficult to create for all object types. This leads to weird artifacts and limitations in manipulation capabilities.

The proposed Part-Aware Diffusion Model (PA-Diffusion) tackles this challenge. PA-Diffusion uses Abstract 3D Models to represent articulated objects, allowing for efficient and arbitrary manipulation. Dynamic feature maps are introduced to transfer the appearance of objects accurately from input to edited images, while also generating novel views or parts reasonably. The model’s effectiveness is demonstrated through extensive experiments, surpassing state-of-the-art methods. The integration of the PA-Diffusion model with 3D object understanding tasks for embodied robots further highlights its versatility and strong potential for various applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computer vision and robotics because it presents a novel approach to manipulating articulated objects in real images, a challenging problem with significant implications for applications such as image editing, robot control, and 3D scene understanding. The method’s efficiency and ability to handle novel object categories open avenues for future research in generative models, 3D reconstruction, and human-robot interaction.

Visual Insights#

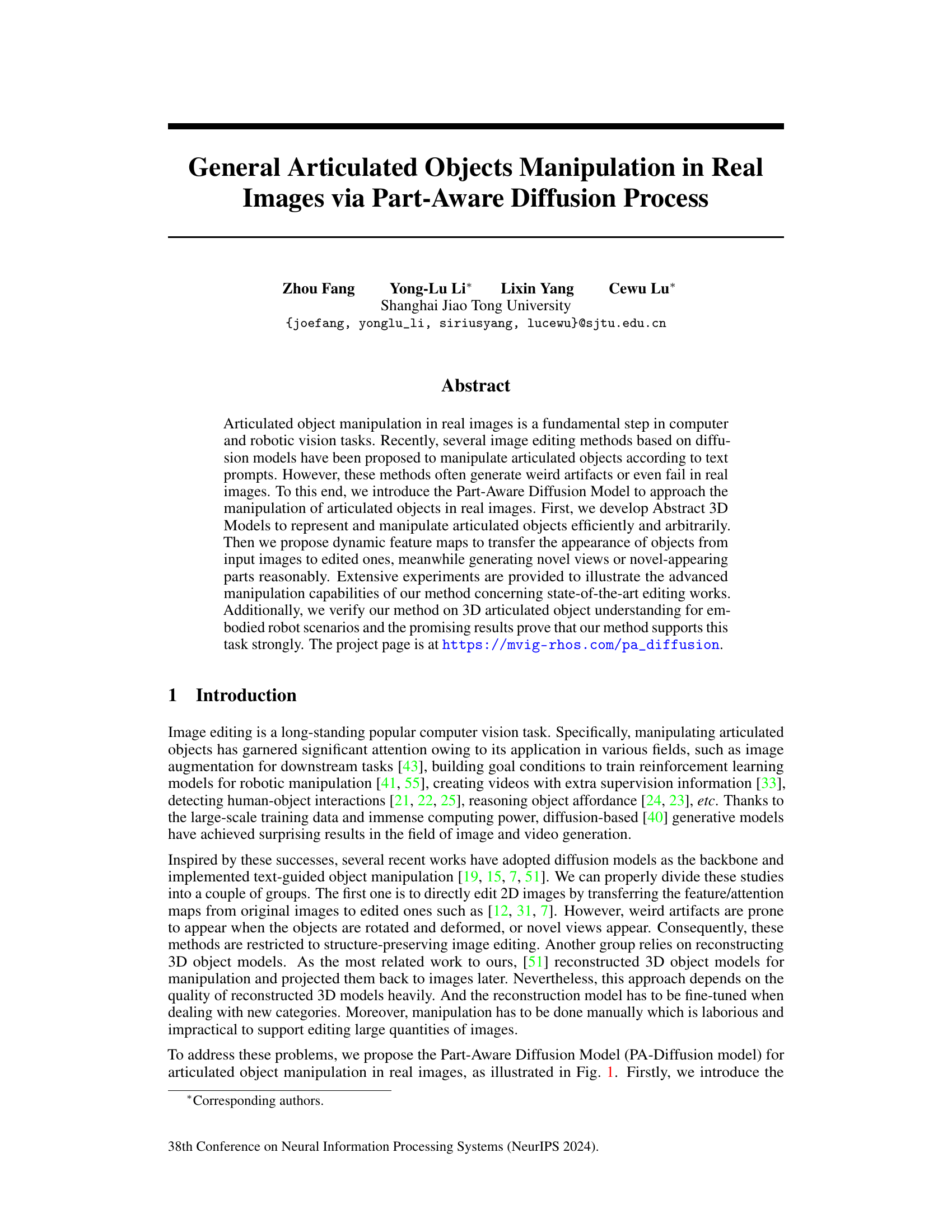

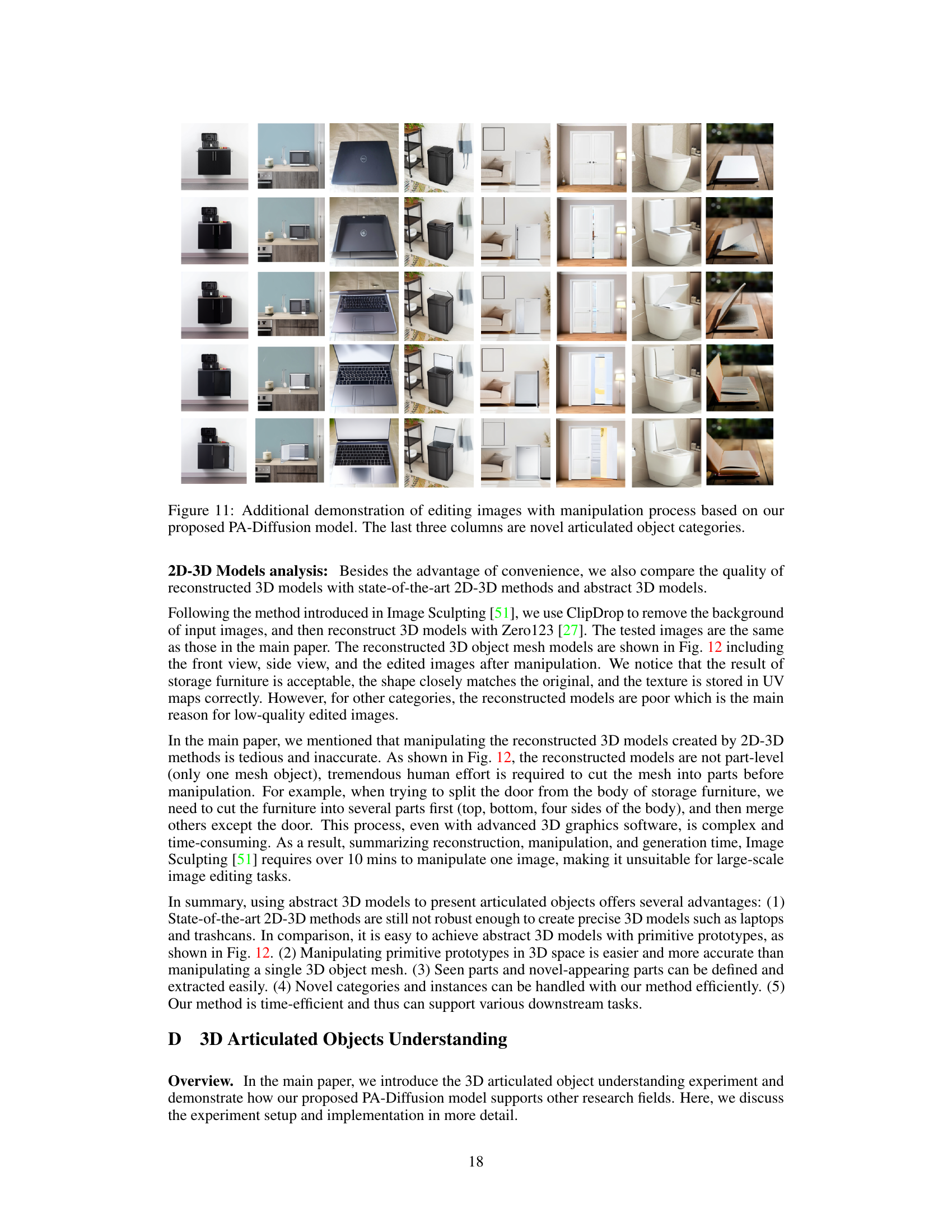

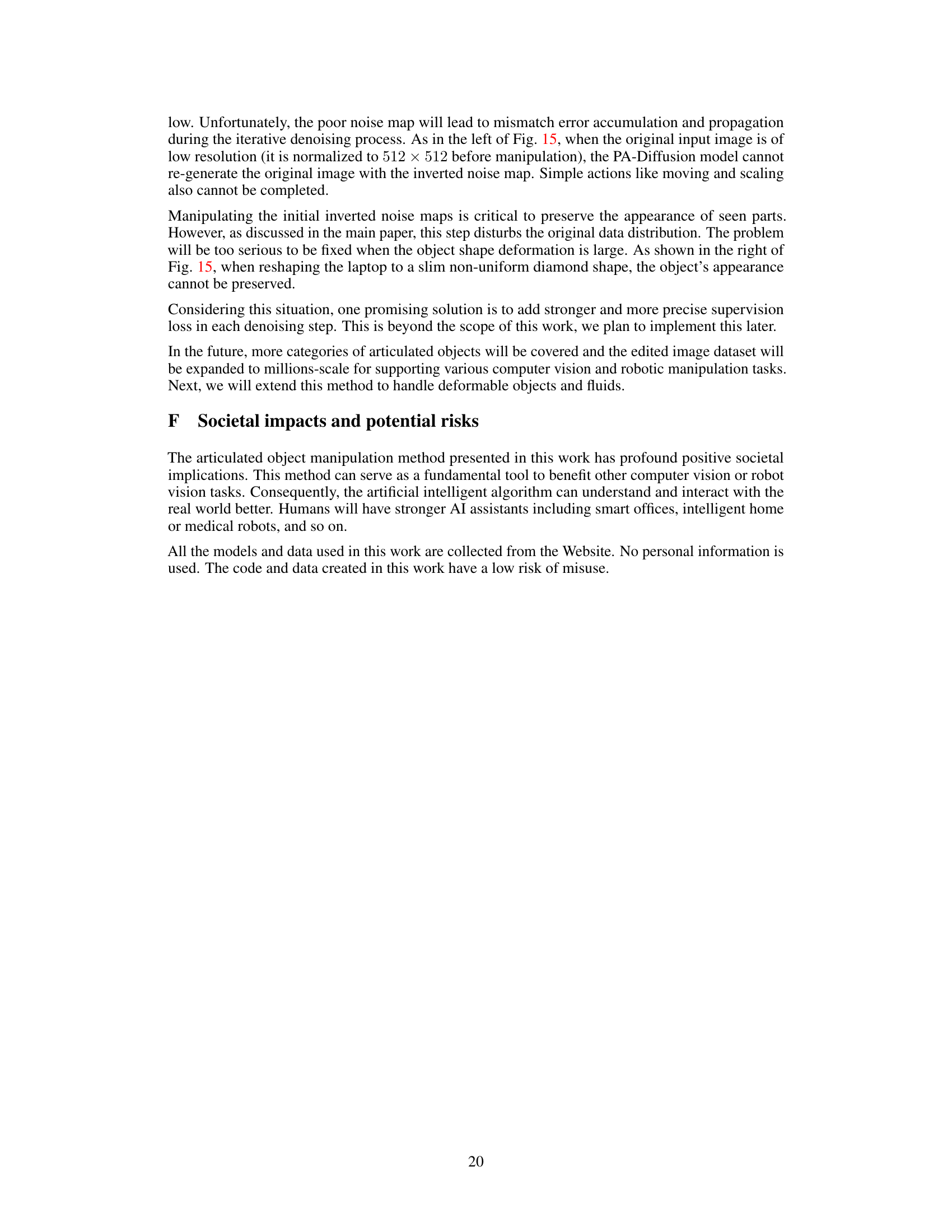

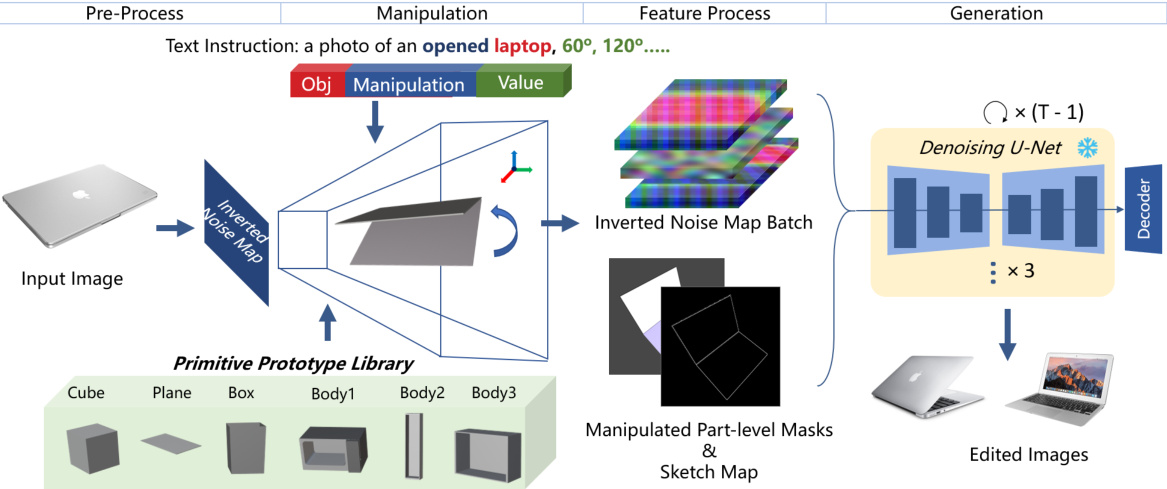

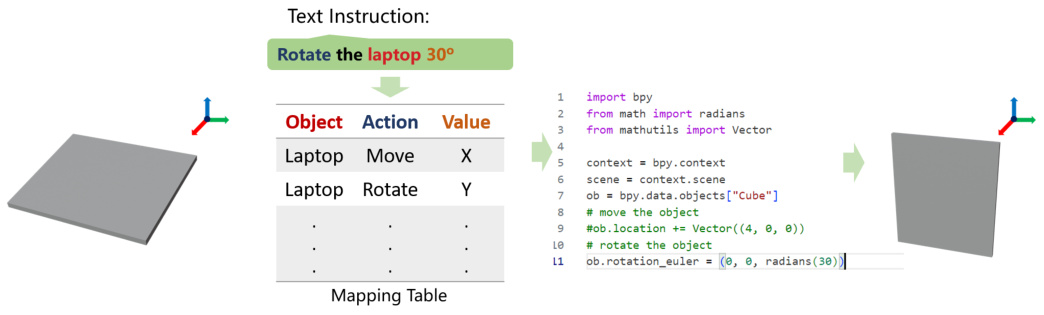

This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the Part-Aware Diffusion Model. It begins with a real 2D image of an object. This 2D image is then mapped to a 3D representation using an abstract 3D model. In the 3D space, manipulations based on text instructions or direct user interaction are performed. Finally, the manipulated 3D model is used to generate a new, edited 2D image reflecting the changes.

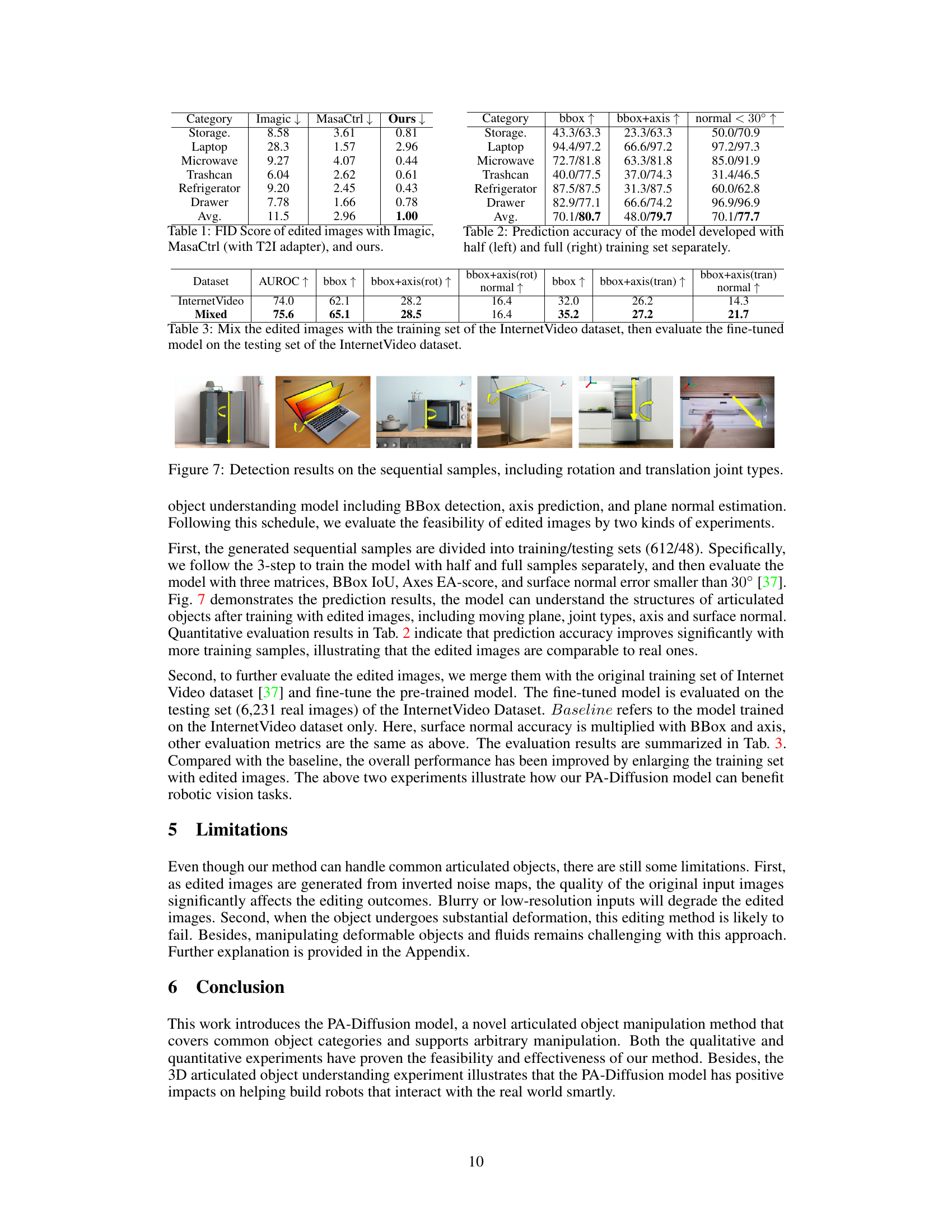

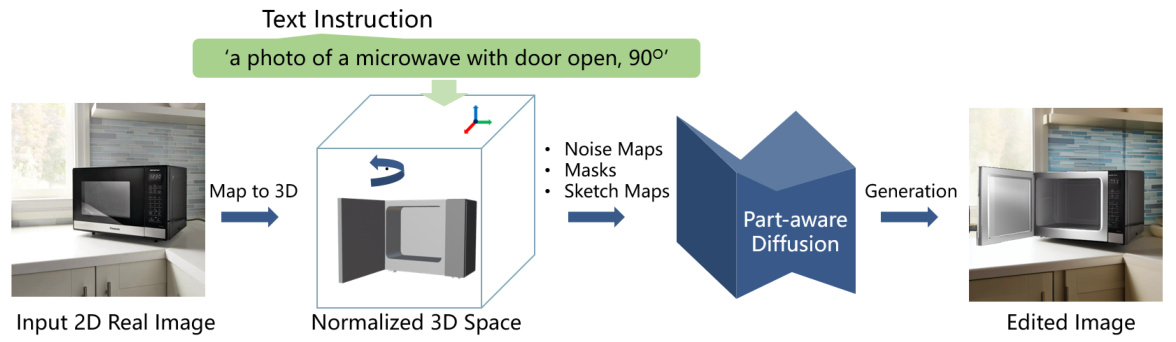

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed PA-Diffusion model against two state-of-the-art image editing methods, Imagic and MasaCtrl (using a T2I adapter), in terms of Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) scores. The FID score is a metric used to evaluate the realism and quality of generated images, with lower scores indicating higher quality and similarity to real images. The comparison is performed across six object categories: Storage, Laptop, Microwave, Trashcan, Refrigerator, and Drawer. The results demonstrate that the PA-Diffusion model significantly outperforms the other methods, achieving substantially lower FID scores.

In-depth insights#

Part-Aware Diffusion#

The concept of ‘Part-Aware Diffusion’ suggests a significant advance in image manipulation, particularly for articulated objects. It implies a diffusion model capable of understanding and operating on individual parts of a complex object, rather than treating it as a monolithic entity. This part-awareness allows for more precise and nuanced control over the editing process, avoiding the common issues of generating unrealistic artifacts or distortions when modifying articulated objects. The model likely incorporates a mechanism for identifying and segmenting the distinct parts, enabling independent manipulation while maintaining overall coherence. Successful implementation could mean significantly improved results in applications like image editing, video generation, and robotic manipulation, moving beyond current limitations in handling intricate object details and complex motions.

3D Abstract Models#

The concept of “3D Abstract Models” presents a novel approach to articulated object manipulation in images. Instead of relying on precise, complex 3D models which are difficult to generate and computationally expensive, this method uses simplified, prototypical 3D representations. These prototypes are basic shapes (cubes, planes, boxes) that can be combined to approximate the structure of various articulated objects. This strategy is highly efficient, reducing the computational burden associated with detailed 3D reconstruction. The use of prototypes also offers enhanced generalizability. The approach allows for easy manipulation of the abstract 3D model, making it suitable for various editing tasks based on textual or interactive guidance. The key advantage is the ability to handle novel object categories with minimal additional training, greatly expanding the applicability of the technique compared to methods dependent on category-specific 3D model training. This strategy significantly reduces the difficulty and time cost of 3D modeling and allows the model to efficiently address novel articulated objects and diverse manipulation tasks.

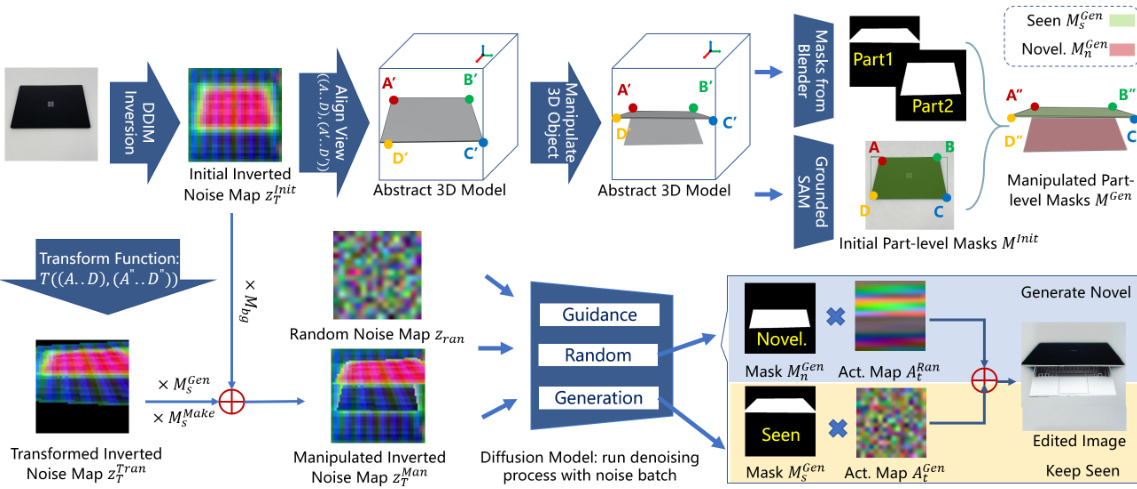

Dynamic Feature Map#

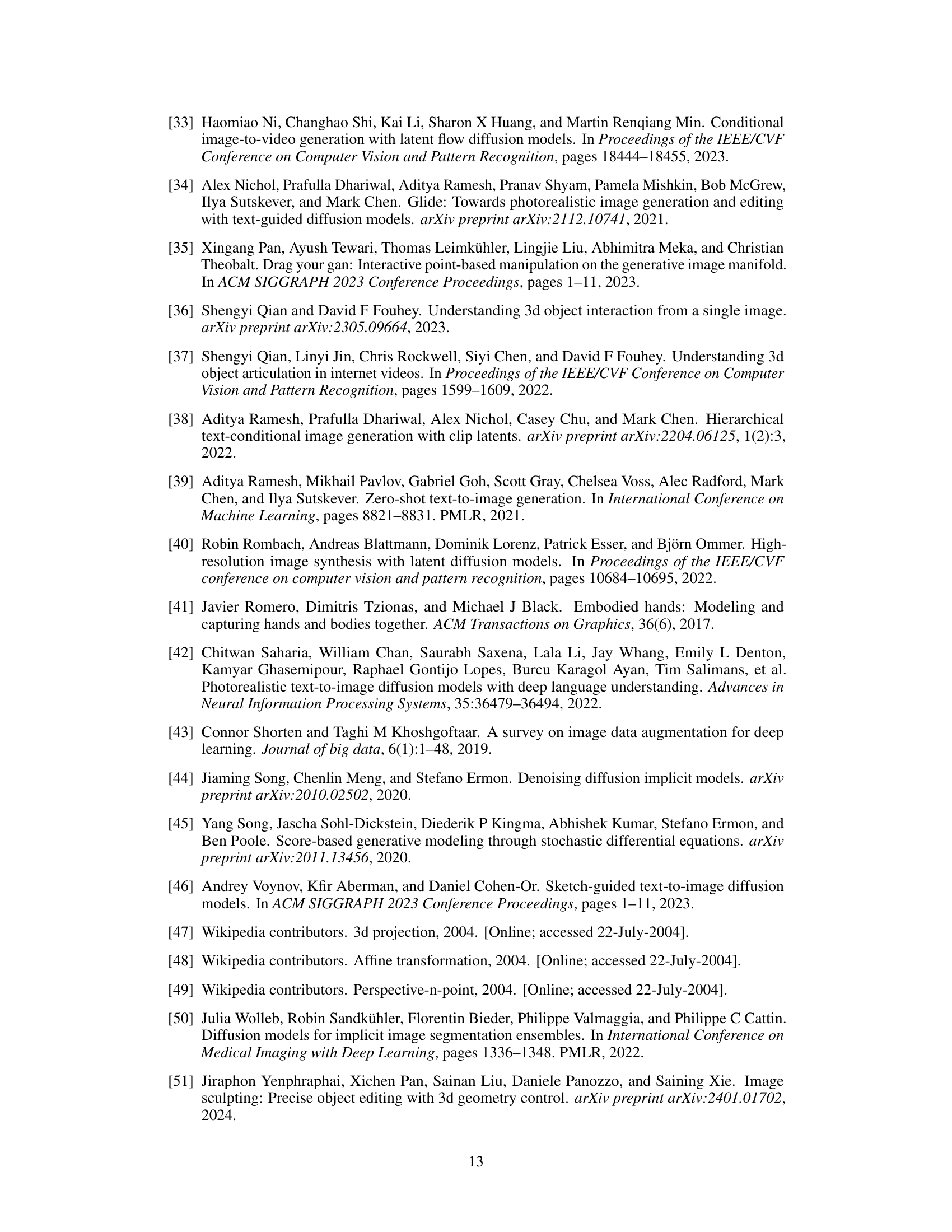

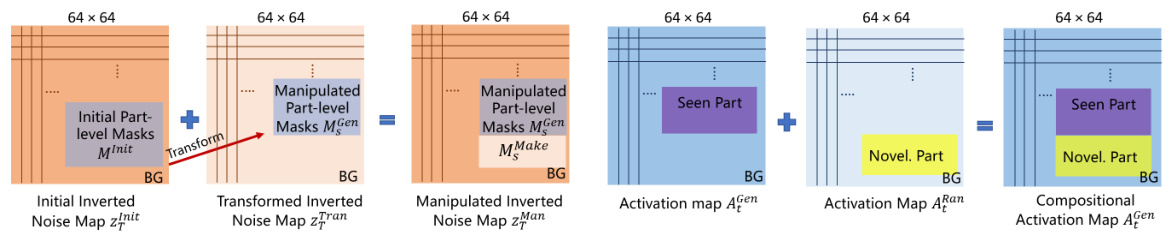

The concept of “Dynamic Feature Maps” in the context of image editing using diffusion models addresses a critical limitation of prior methods: effectively transferring appearance information during object manipulation while simultaneously handling novel views or parts. Static feature maps, common in previous approaches, fail to adapt when objects undergo transformations, resulting in artifacts. The innovation lies in separating appearance transfer into two components: manipulated inverted noise maps and compositional activation maps. The former accurately preserves the appearance of seen parts by leveraging the initial image’s features and transferring them to the manipulated object’s location. Meanwhile, compositional activation maps dynamically generate novel parts and views using random noise as input, ensuring consistency with the manipulated object’s overall style. This two-pronged approach cleverly separates appearance preservation from novel element generation, thus overcoming the limitations of static feature mapping and leading to more realistic and coherent image editing results. This strategy is particularly valuable for editing articulated objects where parts might be obscured or newly revealed during manipulation.

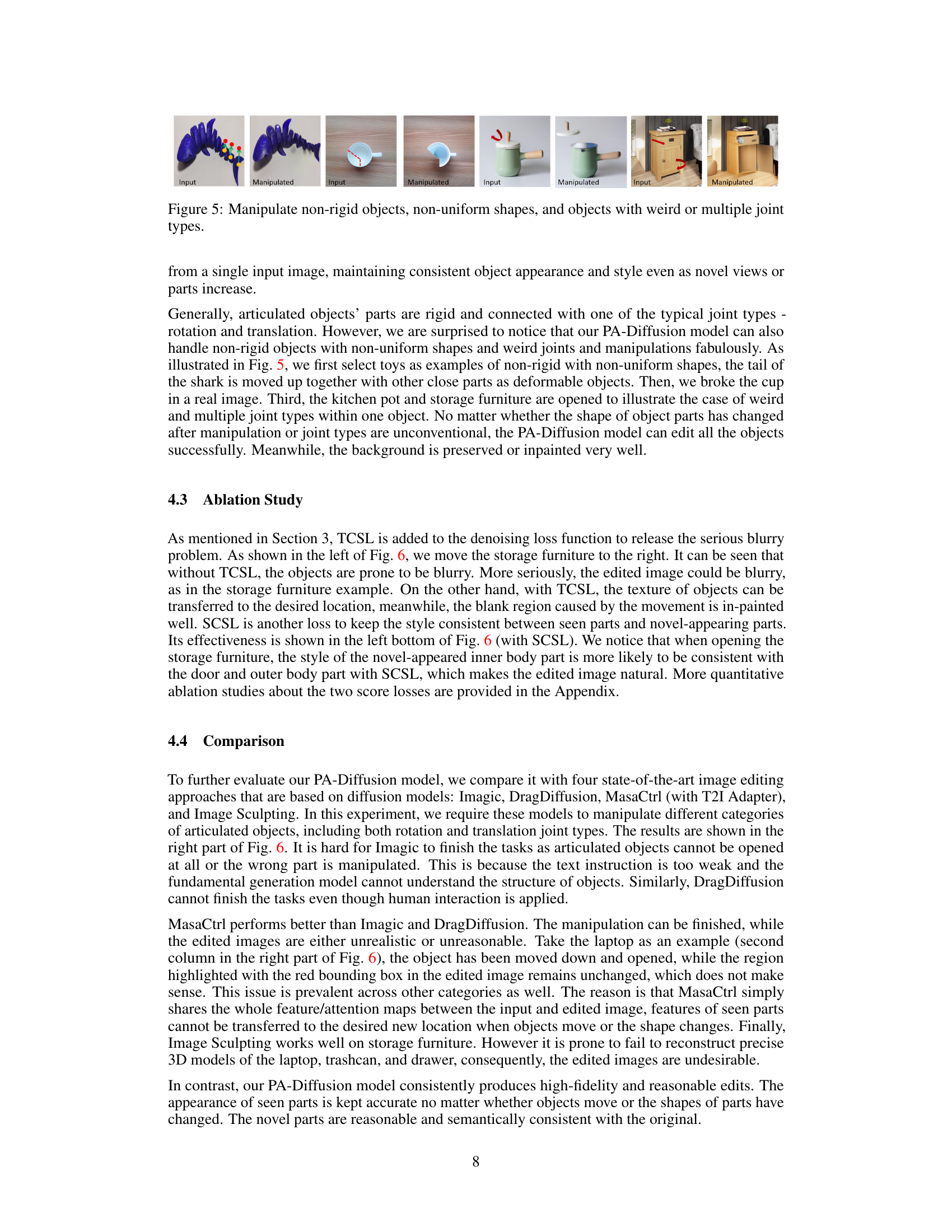

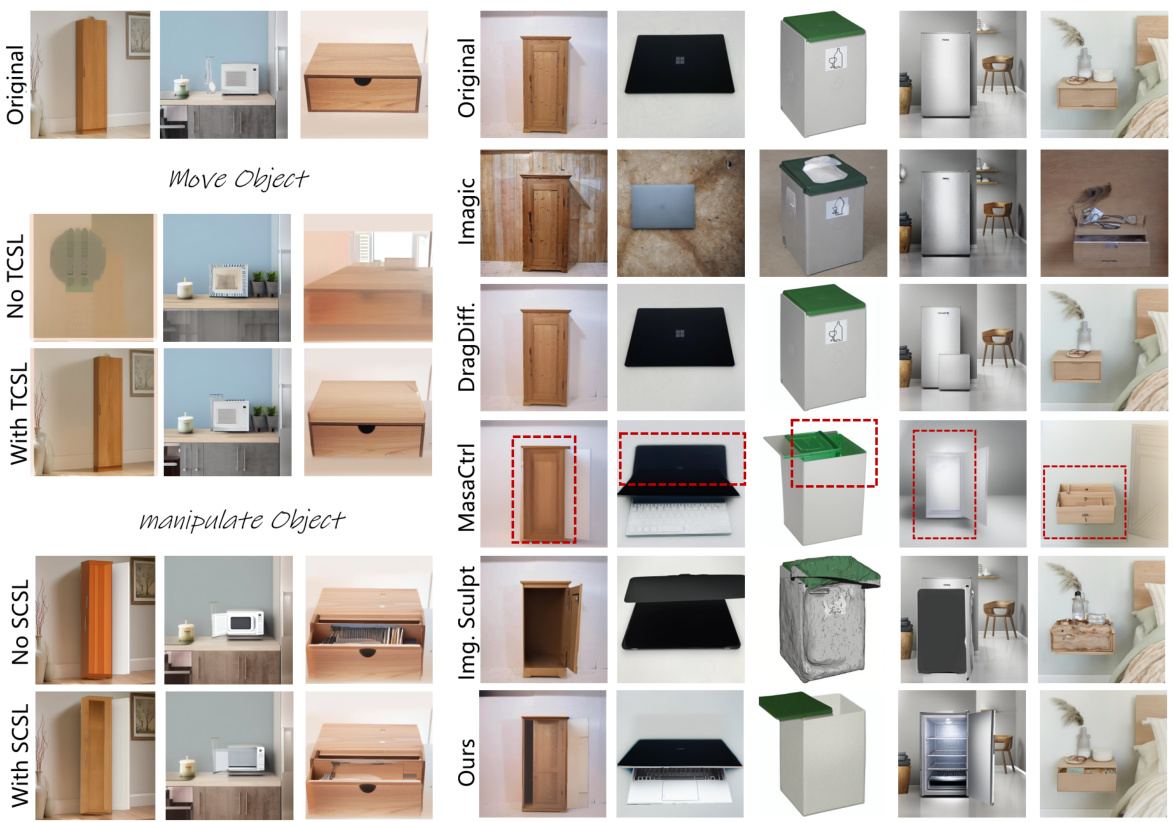

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically evaluates the contributions of individual components within a machine learning model. In the context of image editing, this would involve removing or deactivating parts of the model (e.g., specific loss functions, modules, or data augmentations) to assess their impact on the overall performance. A well-designed ablation study helps to isolate the effects of each component, clarifying their individual importance and functionality. For example, in an image editing model, removing a texture consistency loss might lead to blurry or unrealistic outputs. Observing this decline helps to confirm the importance of this loss function. By methodically removing elements and analyzing changes, researchers can identify essential components and refine the model’s architecture. It also helps in making more informed design choices in future iterations and provides a deeper understanding of how each element contributes to the final result. The results of an ablation study should be quantitatively presented, offering valuable insights to the reader. They should show, in a clear and concise way, that the proposed method’s improvements are directly attributed to specific features and components. Finally, ablation studies contribute to the broader understanding of the field, by sharing valuable insights that help to advance the current techniques and guide future research.

Future Directions#

Future research directions for articulated object manipulation in real images could focus on several key areas. Improving robustness to low-resolution or blurry input images is crucial, as current methods struggle with such conditions. Addressing the challenges posed by deformable objects and fluids would significantly broaden the applicability of these techniques. Exploring more advanced manipulation paradigms beyond simple rotations and translations, such as complex deformations and interactions, would be highly valuable. Developing a more efficient and scalable method for generating and manipulating abstract 3D models is also necessary. Further research should investigate the use of multimodal inputs, such as combining image data with other sensory information (e.g., depth, tactile feedback). Finally, significant progress in this field would be facilitated by the development of larger, more diverse datasets annotated with detailed 3D object information and scene context to support robust and generalized model training.

More visual insights#

More on figures

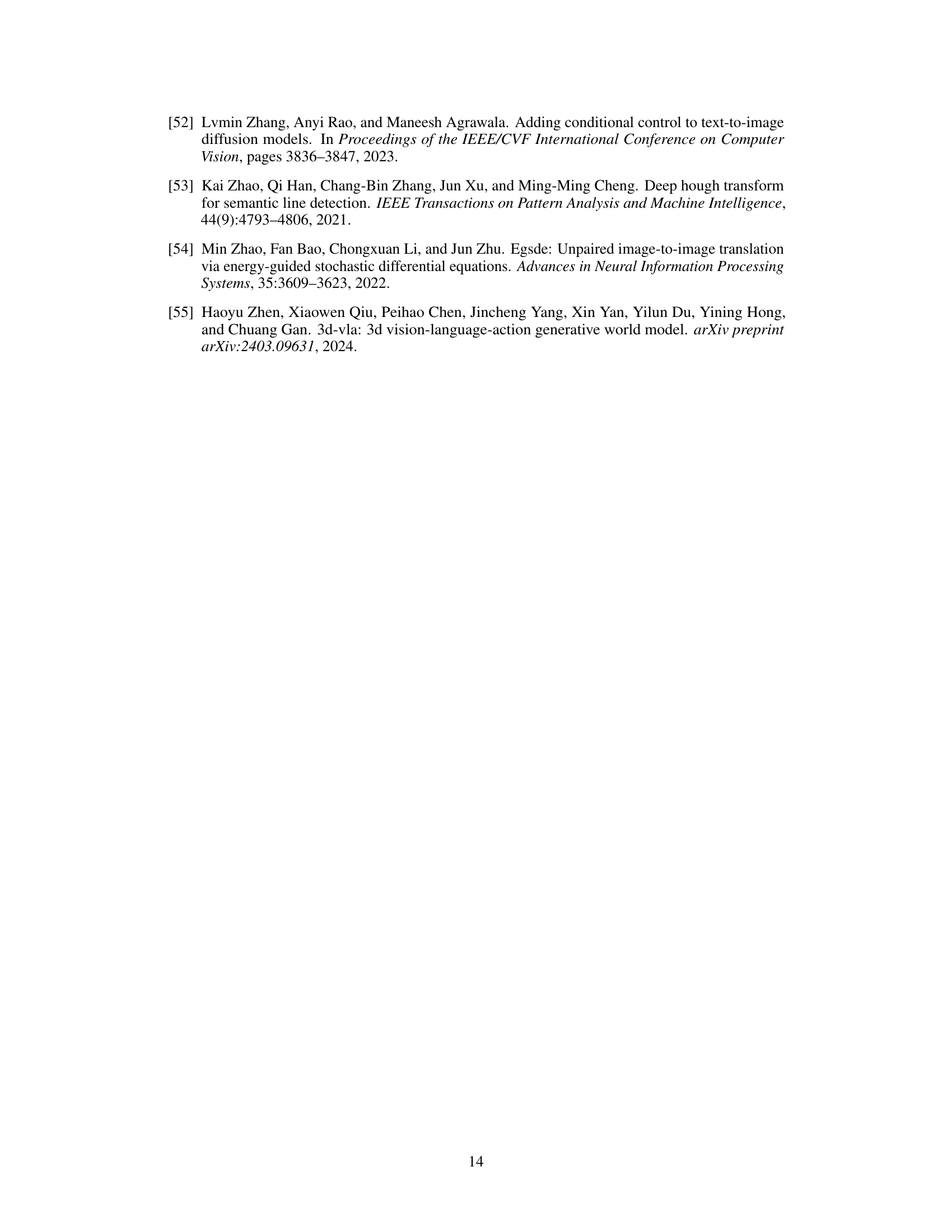

This figure illustrates the four main stages of the PA-Diffusion model’s image editing process: Pre-process, Manipulation, Feature Process, and Generation. The pre-process stage involves segmenting the articulated object from the input image, creating a 3D model using the Primitive Prototype Library, and inverting the noise map of the input image using DDIM. The manipulation stage involves manipulating the 3D model based on text or interactive input. The feature process then transforms the inverted noise map and creates compositional activation maps, while the generation stage uses a denoising U-Net to create the final edited image.

This figure illustrates the pipeline of the PA-Diffusion model for image editing. It starts with preprocessing the input image to generate 3D models and inverted noise maps. Then, the manipulation stage involves using text or interactive means to adjust the 3D object. Finally, the edited image is generated using the transformed noise maps, sketch maps and part-level masks. Each stage is clearly shown with different components and their interactions.

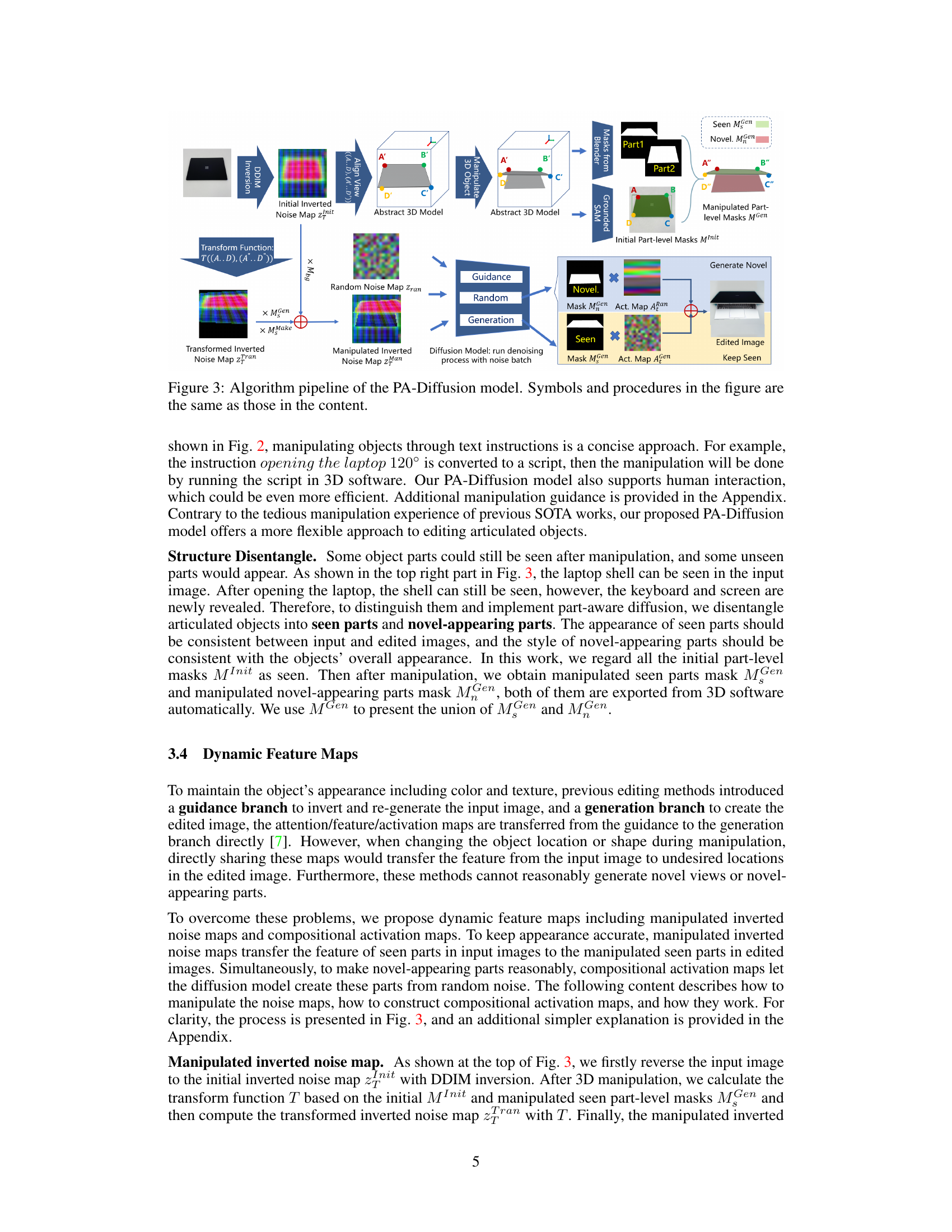

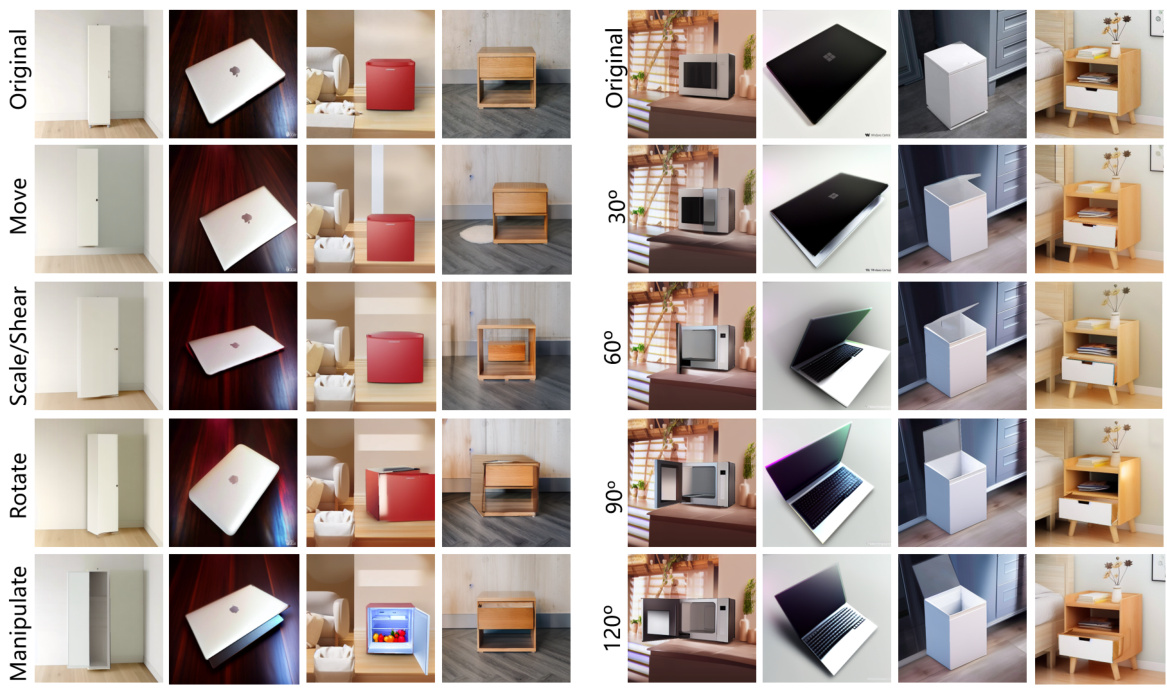

This figure demonstrates the results of basic manipulations (move, scale/shear, rotate) and a sequential manipulation process on articulated objects using the proposed PA-Diffusion model. The left side shows how the model handles basic manipulations, seamlessly integrating edited objects with their backgrounds and automatically in-painting blank areas. The right side showcases a sequential opening of an object (from 0° to 120°), highlighting the model’s ability to maintain consistent style and appearance even as new parts of the object become visible.

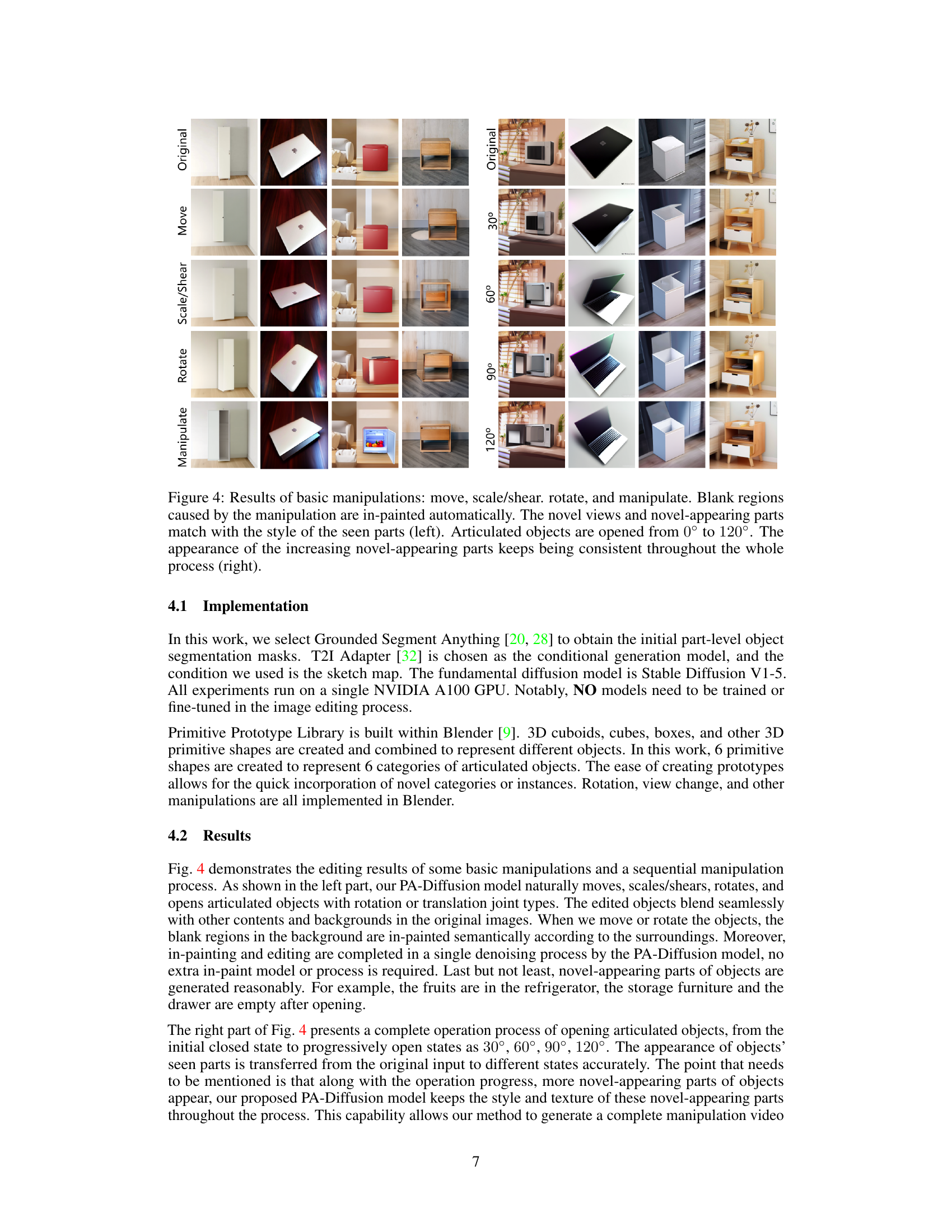

This figure showcases the PA-Diffusion model’s ability to manipulate a variety of objects, demonstrating its versatility in handling different types of objects. It highlights the model’s capacity to handle non-rigid objects (like toys), objects with non-uniform shapes (the toy shark), and those with unusual or multiple joint types (the broken cup, kitchen pot, and storage furniture). The results show the model’s robustness in generating realistic and coherent edits, even for complex objects and manipulations.

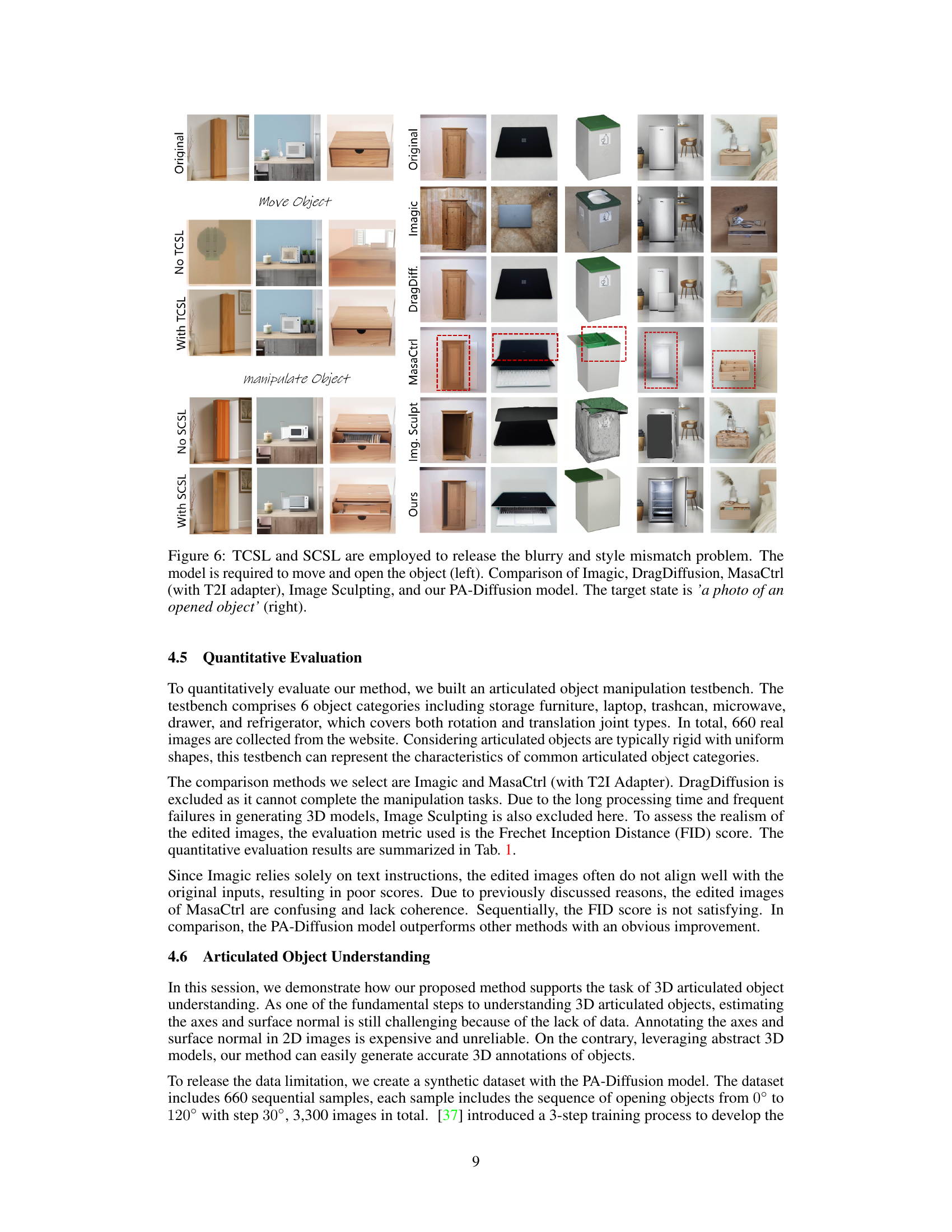

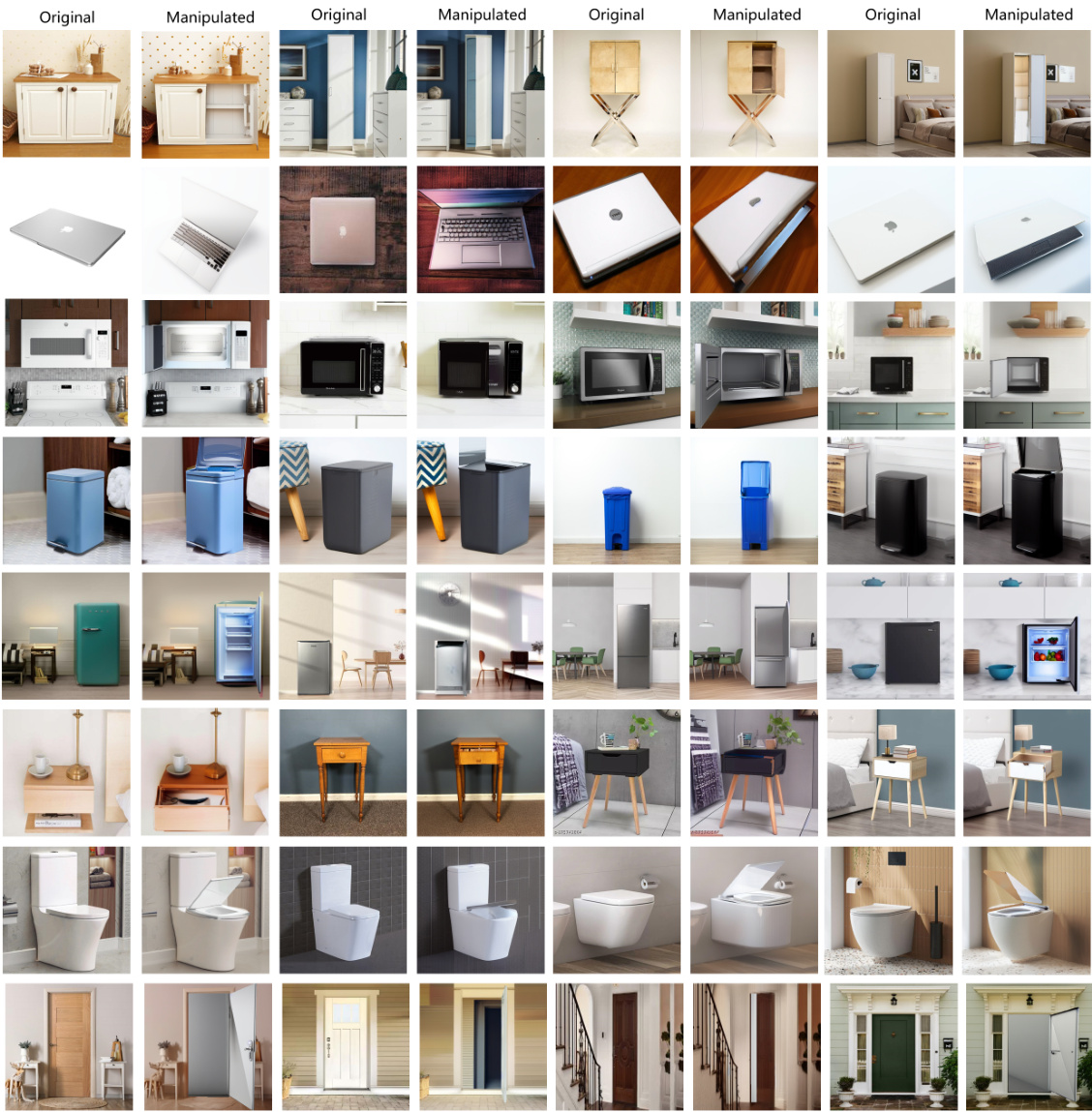

The figure demonstrates a comparison of different image editing models’ ability to manipulate articulated objects. The left side shows the effect of using TCSL and SCSL loss functions in the PA-Diffusion model to reduce blurriness and style inconsistencies. The right side compares the PA-Diffusion model with several state-of-the-art methods (Imagic, DragDiffusion, MasaCtrl, Image Sculpting), highlighting its superior performance in generating realistic and coherent edits of various objects (storage furniture, laptop, trashcan, microwave, etc.).

This figure illustrates the pipeline of the proposed Part-Aware Diffusion Model (PA-Diffusion). It shows the process from pre-processing the input image (2D articulated object reconstruction and noise map inversion), to manipulating the objects in the 3D space (text or interaction-based), and finally generating the edited image using transformed noise maps, sketch maps, and part-level masks.

This figure illustrates the four stages of the image editing process using the Part-Aware Diffusion Model. First, the input image is pre-processed, segmenting articulated objects and creating their abstract 3D models and inverted noise maps. Second, these 3D models are manipulated using text or human interaction. Third, masks and sketches based on the manipulation are generated. Finally, these masks, sketches, and transformed inverted noise maps are used in a generation model to create the final edited image.

This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the proposed PA-Diffusion model for image editing. It shows four stages: 1) Pre-processing, where input images are processed and 3D models created; 2) Manipulation, allowing for arbitrary changes to the 3D model based on text or user interaction; 3) Feature Processing, where masks and sketches are generated for use in the next stage; and 4) Generation, the final image generation step using a diffusion model.

This figure shows the results of basic manipulations (move, scale/shear, rotate) and a sequential manipulation process using the PA-Diffusion model. The left side demonstrates the model’s ability to seamlessly integrate manipulations into the scene, with in-painting automatically handling blank regions. The right side showcases the consistency in appearance of novel parts created during a sequential process (opening an object from 0° to 120°).

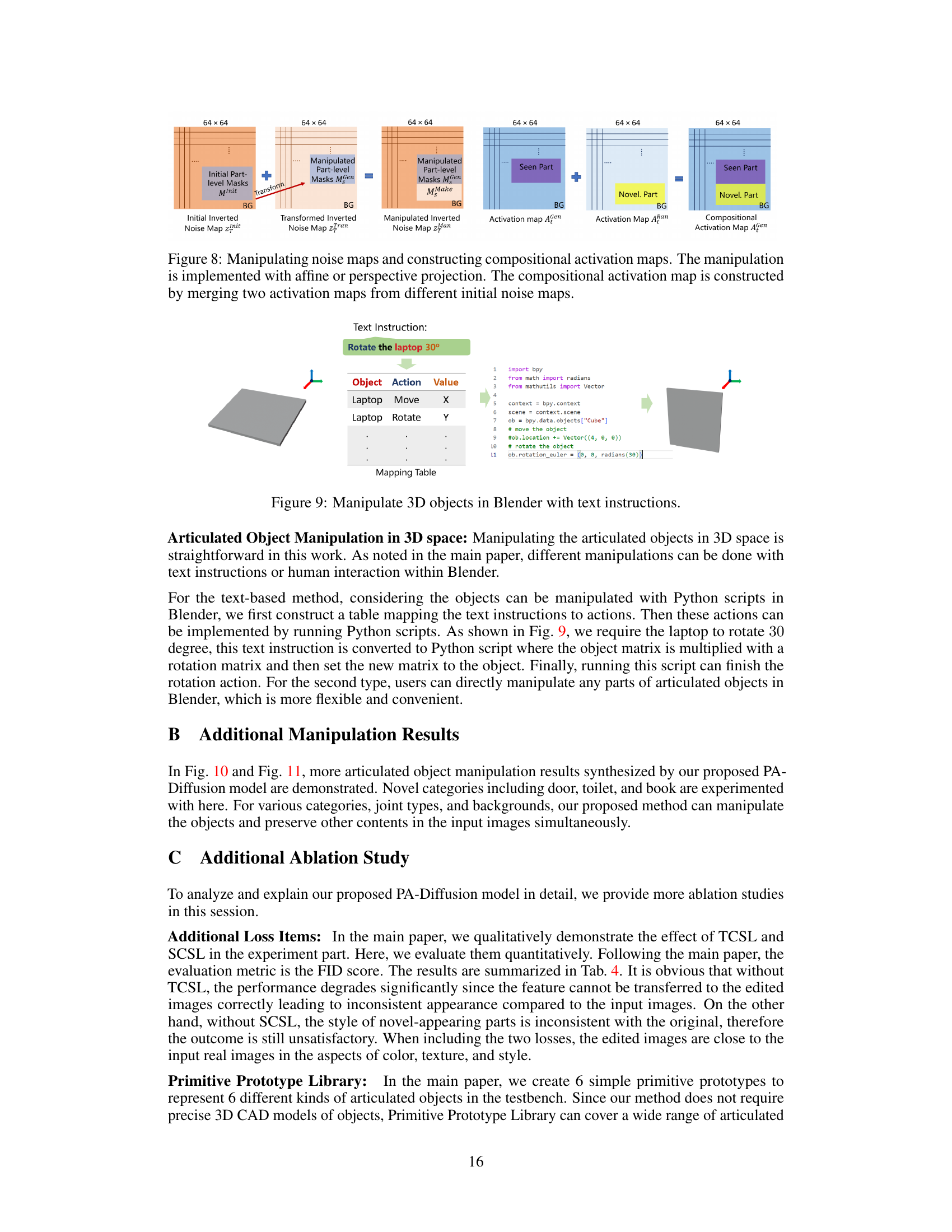

This figure shows additional examples of images edited using the proposed PA-Diffusion model. The results demonstrate the model’s ability to manipulate various articulated objects across different categories (storage furniture, laptop, microwave, trashcan, door, drawer, refrigerator, and toilet) while maintaining realistic image quality and consistency. Each row shows the original image and then the manipulated image, highlighting the successful application of the model to a wider range of objects and manipulation tasks.

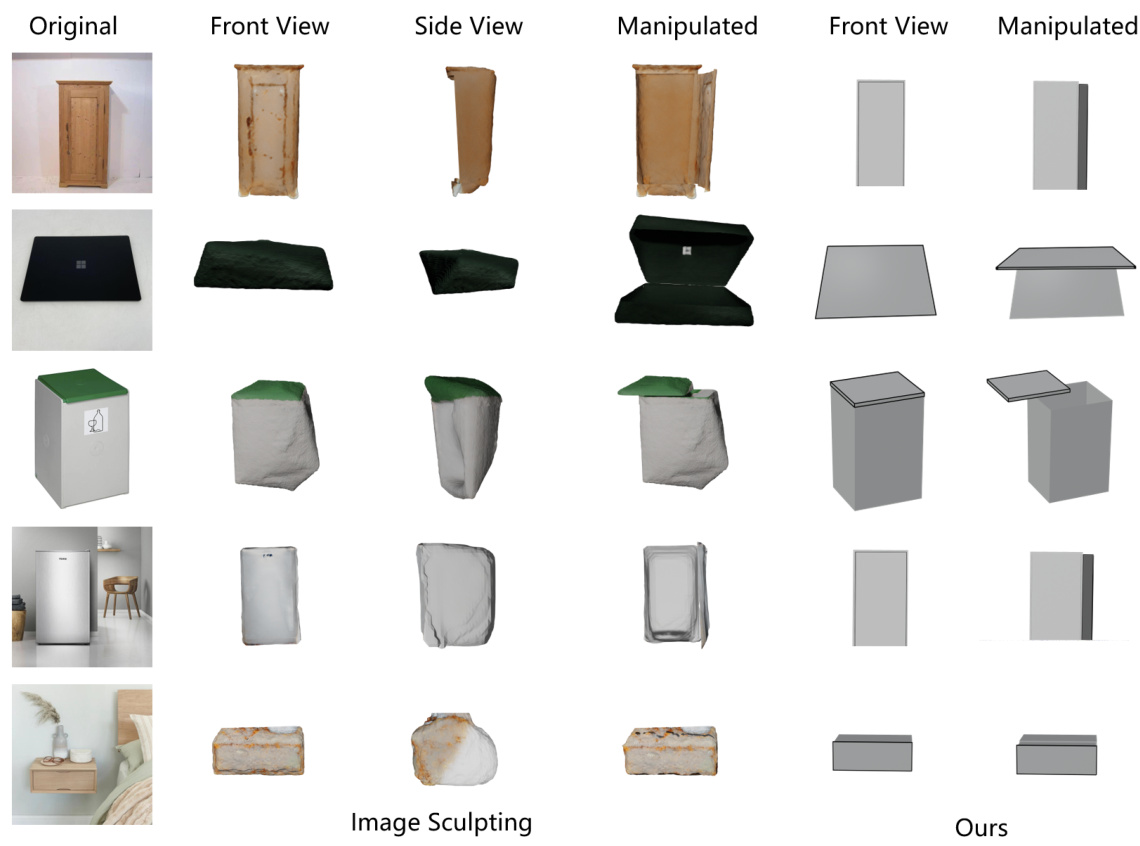

This figure compares the 3D models reconstructed by the Image Sculpting method and the proposed method. Image Sculpting uses a 2D-to-3D reconstruction technique to create detailed 3D models, while the proposed method uses a simpler, abstract 3D model based on primitive prototypes (like cubes and planes). The figure shows the original images, front and side views of the reconstructed 3D models from Image Sculpting, the manipulated 3D models from Image Sculpting, the front and side views of the abstract 3D models generated by the proposed method, and the manipulated abstract 3D models. This visual comparison highlights the differences in model complexity and the efficiency of the proposed method, which uses simpler primitives for faster and more efficient manipulation.

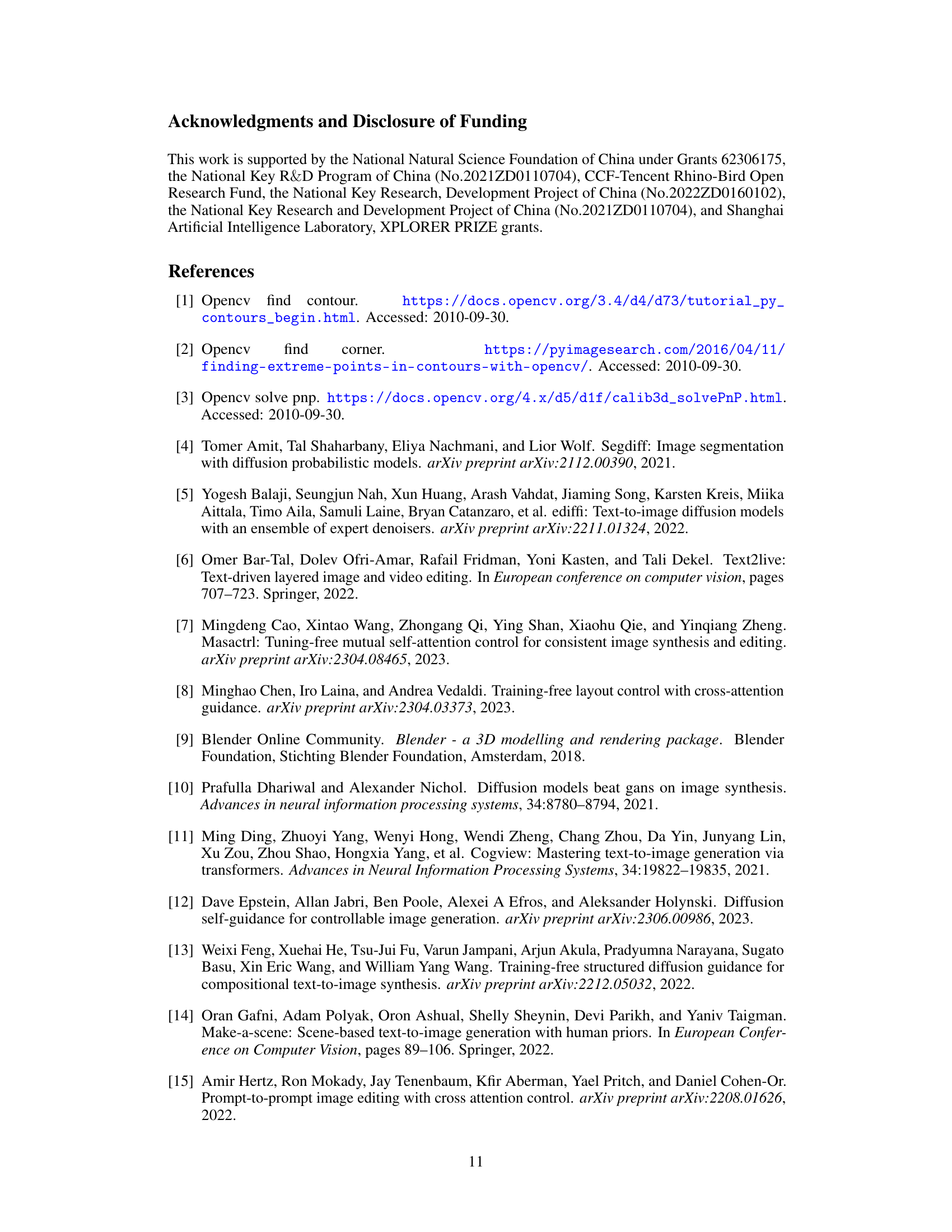

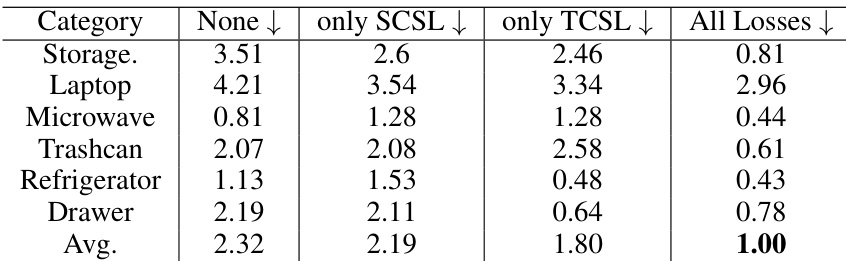

This figure demonstrates the process of obtaining bounding box and rotation/translation axis annotations from part-level masks. It visually shows how these annotations are derived from the segmented parts of objects. Each row represents a different object, displaying the segmented parts (Part1 and Part2), the corresponding RGB image section and the extracted annotations overlaid on the RGB image. The annotations are crucial for the 3D manipulation and understanding stages of the PA-Diffusion model.

This figure compares the 3D object models reconstructed by the Image Sculpting method and the proposed method. Image Sculpting uses a 2D-to-3D reconstruction pipeline, while the proposed method uses abstract 3D models built from a primitive prototype library. The comparison shows that the proposed method’s abstract 3D models are simpler, more easily manipulated, and more suitable for generating high-fidelity edited images than the complex and often inaccurate 3D models produced by Image Sculpting. This highlights the efficiency and effectiveness of the proposed approach for articulated object manipulation in real images.

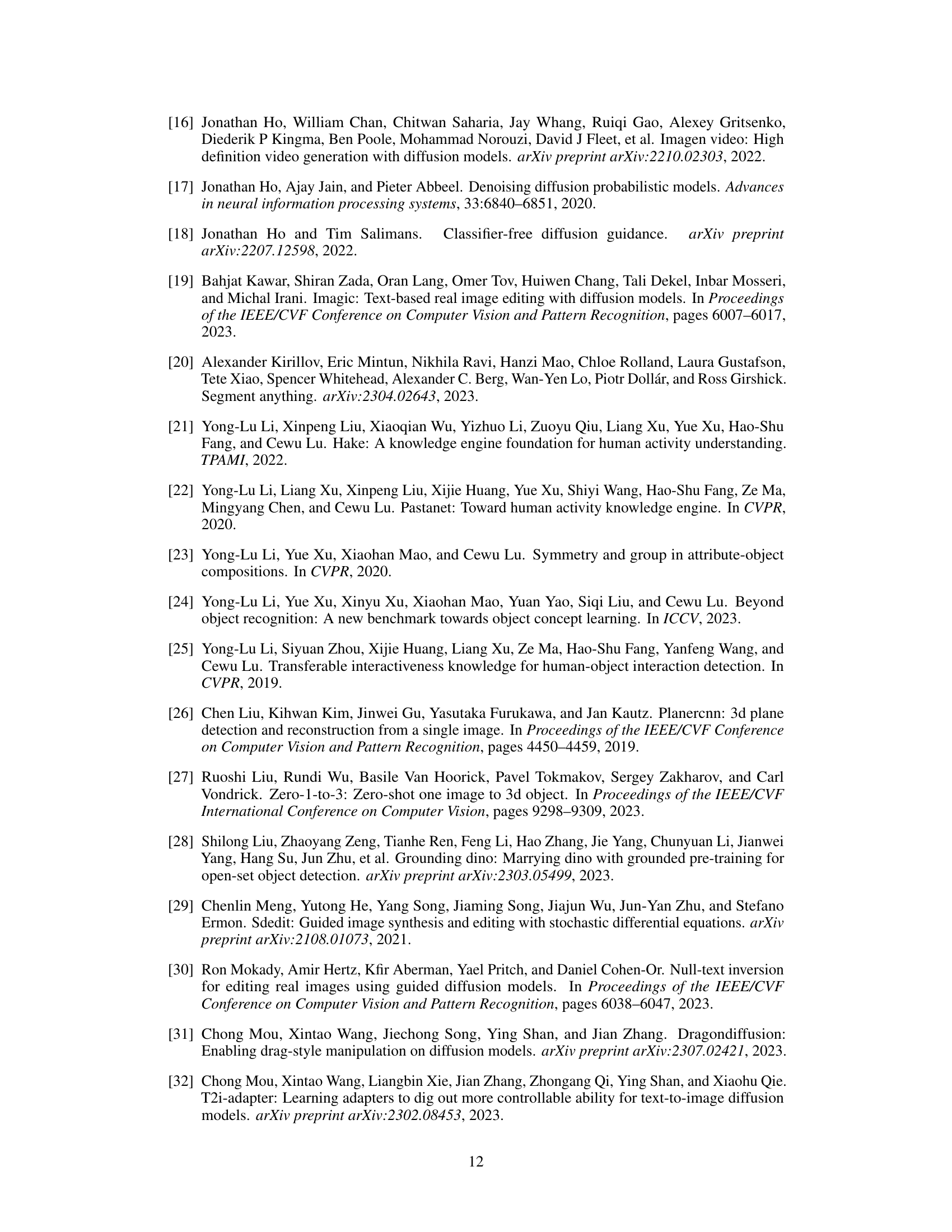

This figure demonstrates limitations of the PA-Diffusion model. The left side shows that when the input image quality is low (low resolution), the model fails to regenerate the original image or perform simple manipulations like moving and scaling. The right side illustrates that when the object undergoes significant shape deformation, the model struggles to maintain the object’s appearance and the output image is not preserved well. These limitations highlight scenarios where the model’s performance is impacted by the input image quality and the extent of object shape changes.

More on tables

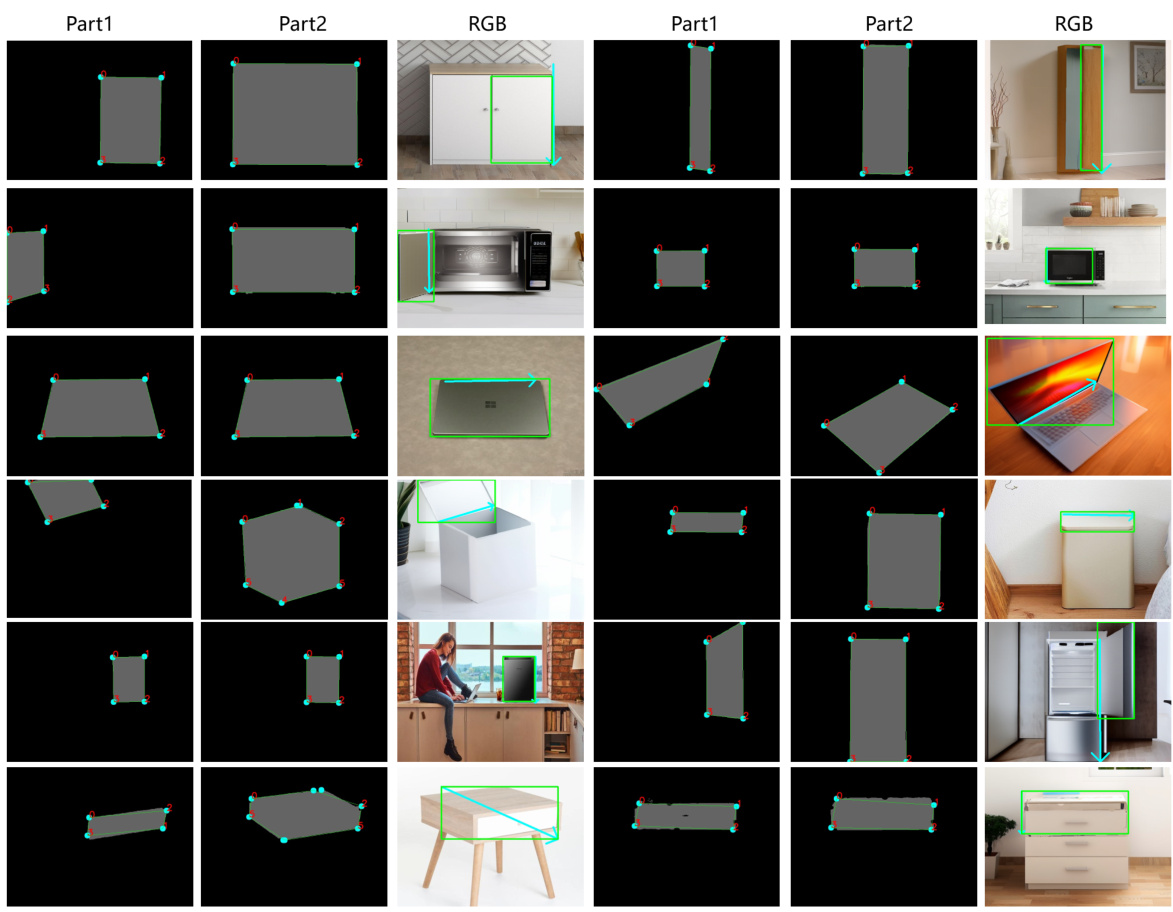

This table presents the quantitative evaluation results of a model trained using two different training sets. The results are split to show the performance when half of the training set is used (left), versus the full training set (right). The model’s performance is evaluated across six different object categories using three distinct metrics: bounding box (bbox) accuracy, bounding box plus axis (bbox+axis) accuracy (for both rotation and translation), and normal vector accuracy (within a 30° error margin). The table demonstrates the effect of training data size on the model’s ability to accurately predict these aspects of the articulated objects.

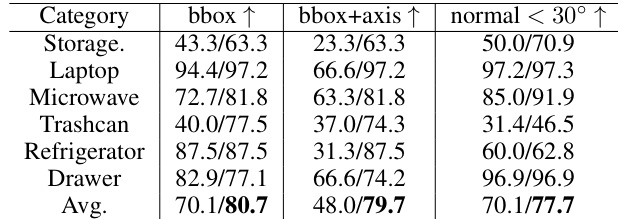

This table presents the quantitative results of the experiment on articulated object understanding. The model is trained on either half or the full training dataset, and then evaluated on the test set. The metrics reported include AUROC (Area Under the ROC Curve), bounding box accuracy (bbox), bounding box plus axis prediction accuracy (bbox+axis), and surface normal prediction accuracy (normal). The table is separated into two parts: (1) a dataset containing only the Internet Video Dataset and (2) a dataset combining Internet Video with other images. Rotation (rot) and Translation (tran) joint types are evaluated separately. Higher scores generally indicate better performance.

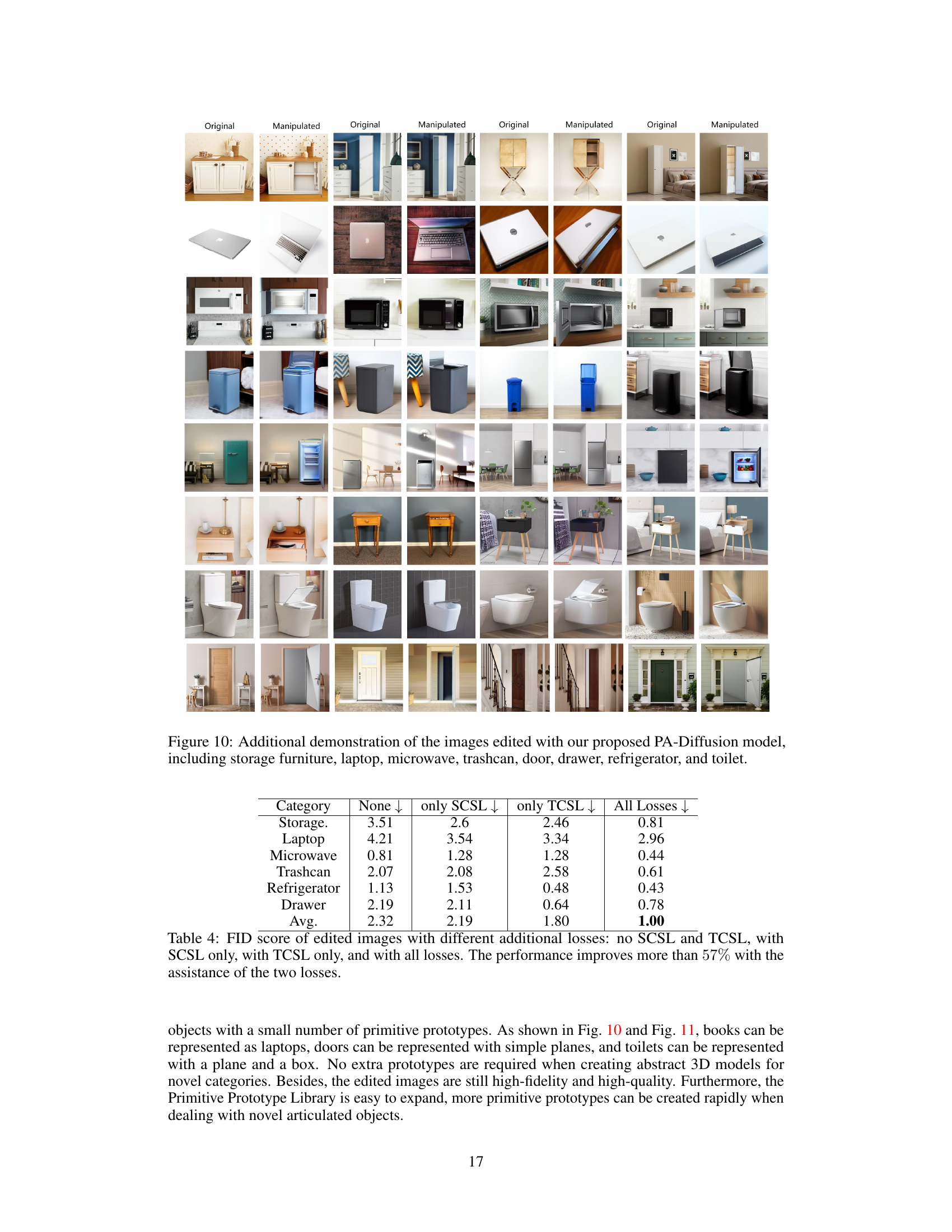

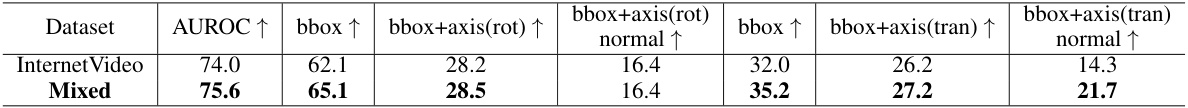

This table presents the FID (Frechet Inception Distance) scores for image editing results using different combinations of loss functions: Texture Consistency Score Loss (TCSL) and Style Consistency Score Loss (SCSL). It shows that using both TCSL and SCSL significantly improves the quality of the edited images (as measured by FID score), resulting in a more than 57% improvement compared to using neither loss function.

Full paper#