↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Solving coupled Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) in multiphysics systems is challenging due to complex geometries, interactions between physical variables, and limited high-resolution training data. Existing neural operator architectures struggle with these issues, limiting their effectiveness in real-world applications. They often require extensive training data and fail to generalize well to new, unseen problems.

This paper introduces Codomain Attention Neural Operator (CoDA-NO), a novel transformer-based neural operator designed to tackle these challenges. CoDA-NO processes functions along the codomain (channel space), enabling self-supervised learning and efficient adaptation to new systems. By using a curriculum learning approach and positional encoding, self-attention, and normalization layers in function spaces, the model can efficiently learn representations from different PDE systems and achieve state-of-the-art performance. Experiments demonstrate that CoDA-NO outperforms existing methods in various multiphysics problems, exhibiting superior generalization capabilities, especially with limited data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with multiphysics PDEs due to its novel approach using codomain attention neural operators. It addresses the limitations of existing methods by enabling self-supervised learning and few-shot learning, paving the way for efficient solutions to complex problems with limited data. The generalizability of the method across diverse physical systems further enhances its significance, opening new avenues for research in various scientific and engineering domains. The improved efficiency and parameter reduction compared to existing models adds to its practical value.

Visual Insights#

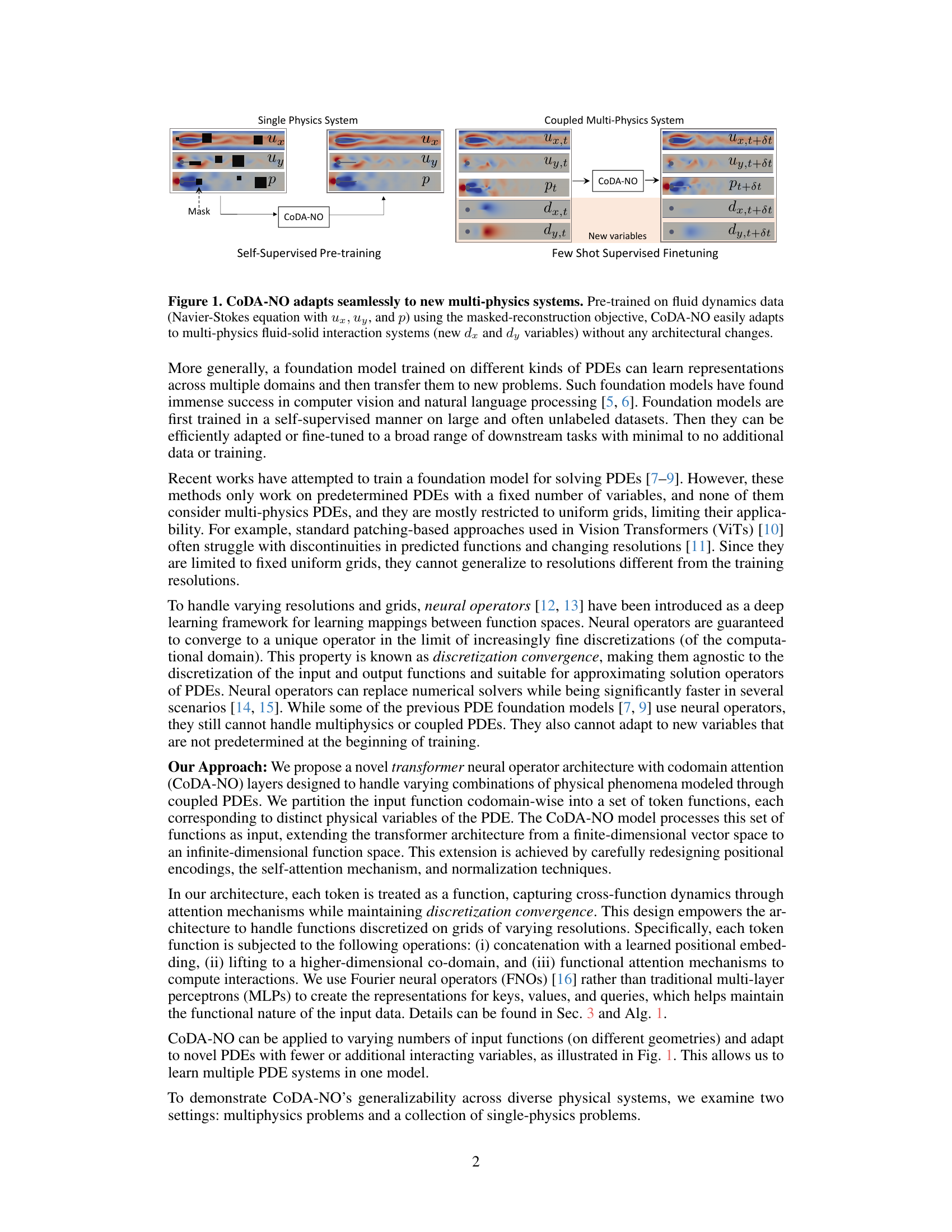

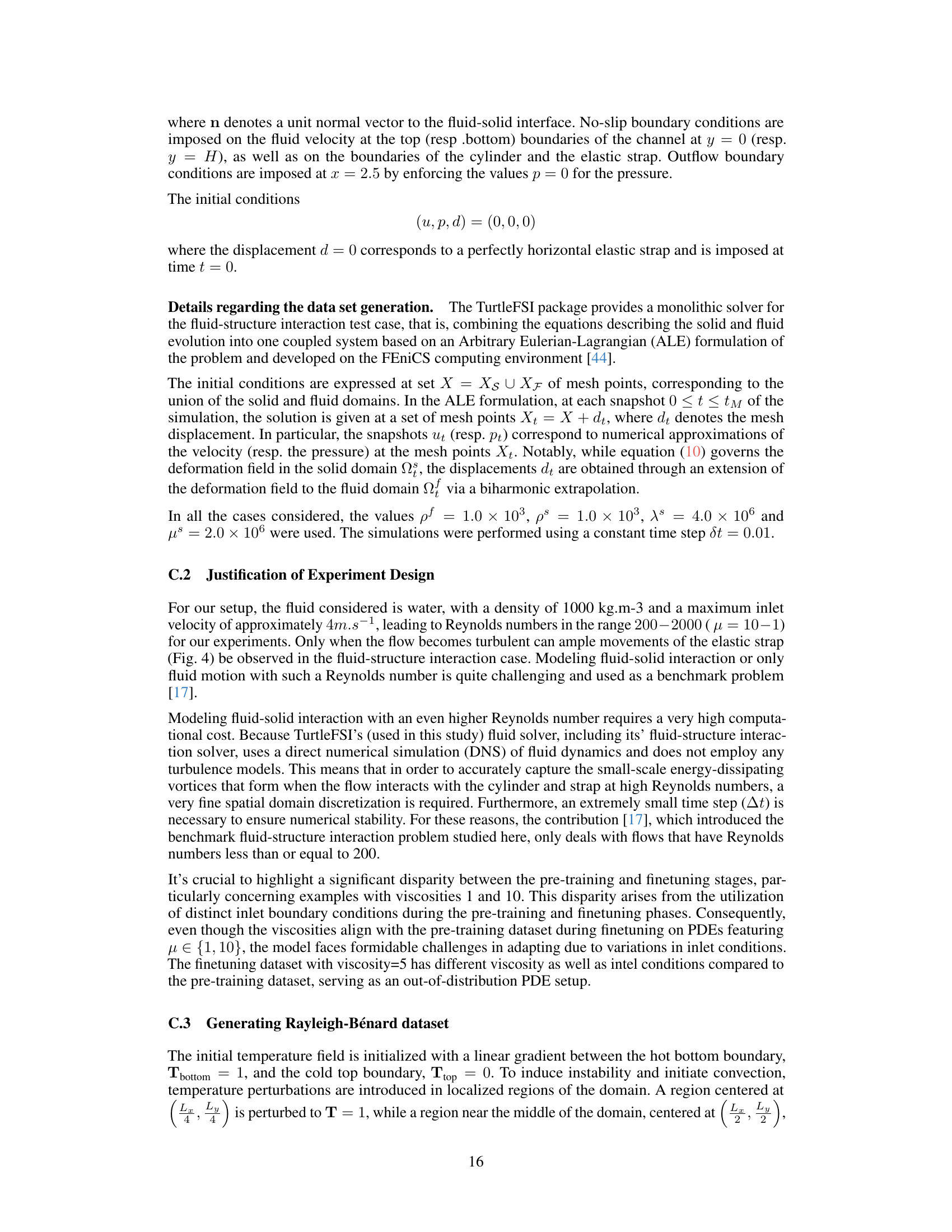

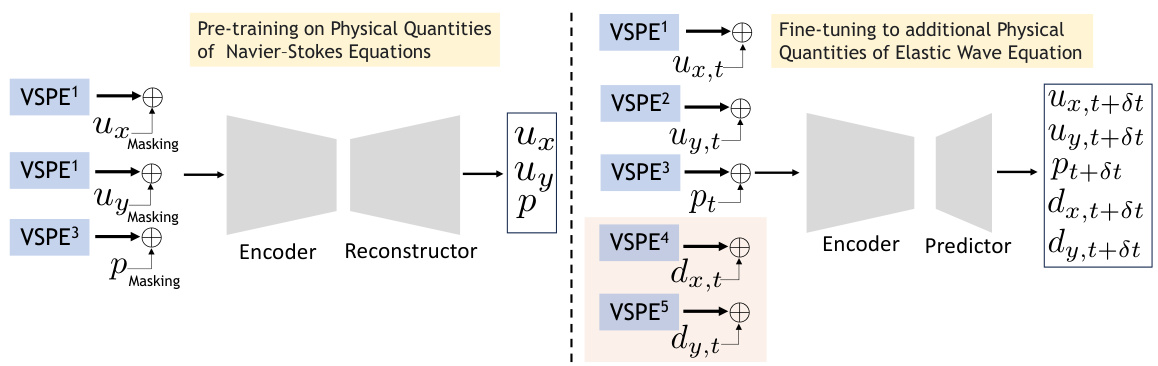

This figure illustrates how the proposed CoDA-NO model can be pre-trained on a single-physics system (fluid dynamics) using self-supervised learning (masked reconstruction) and then easily adapted to a coupled multi-physics system (fluid-structure interaction) by simply adding new variables to the input without requiring any changes to the model architecture. This demonstrates the model’s adaptability and ability to learn representations transferable across different physical systems.

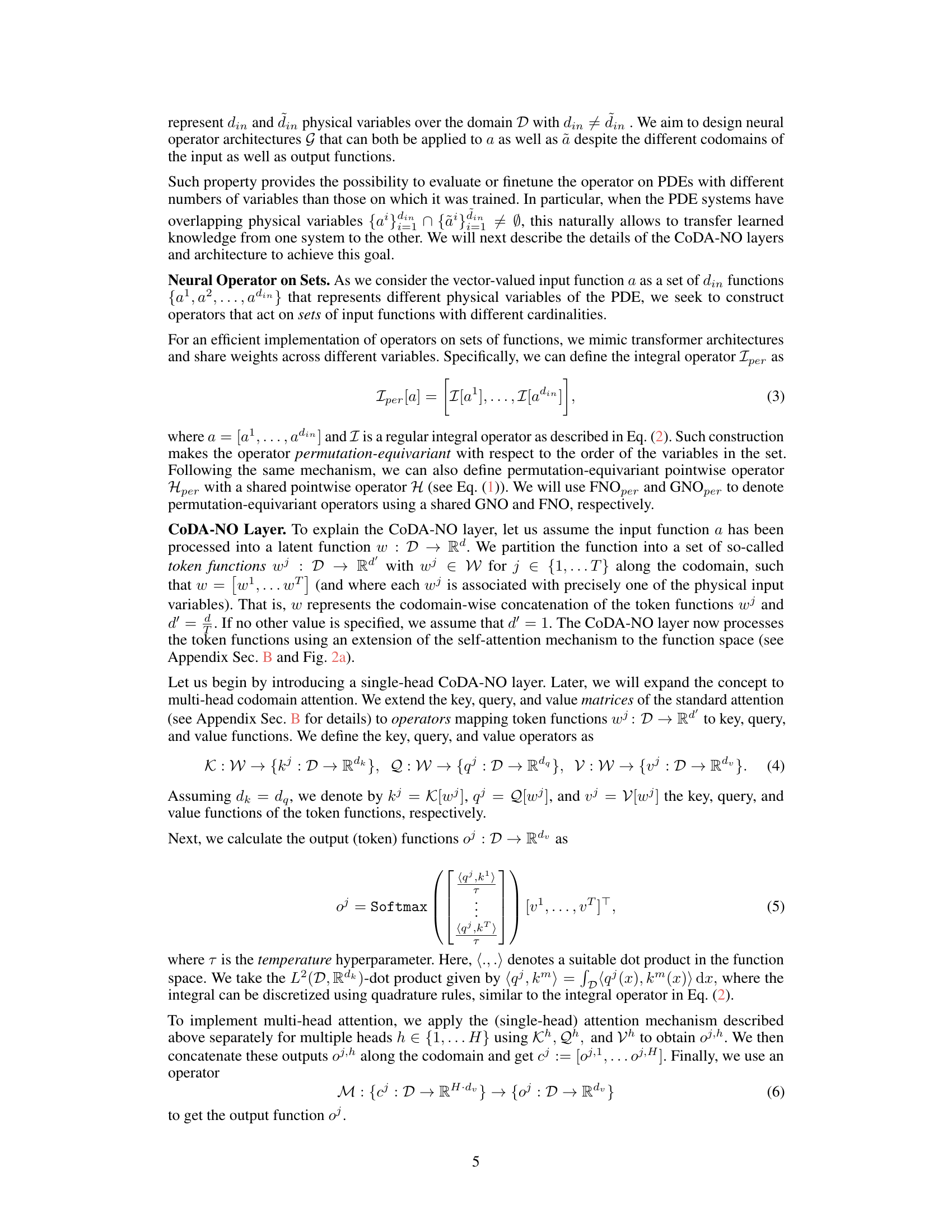

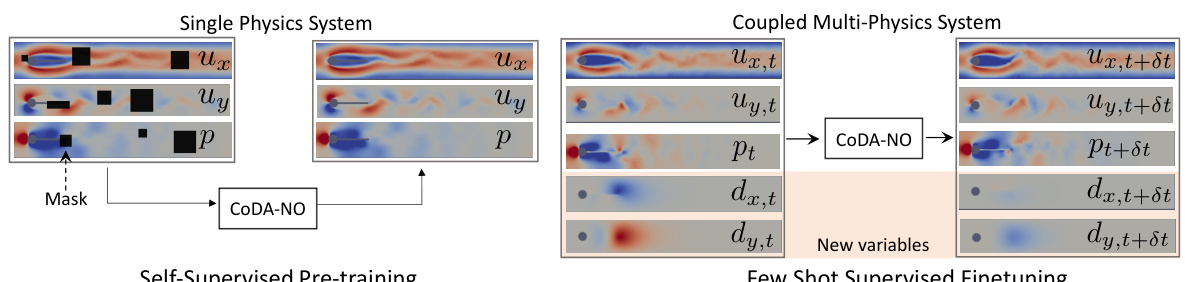

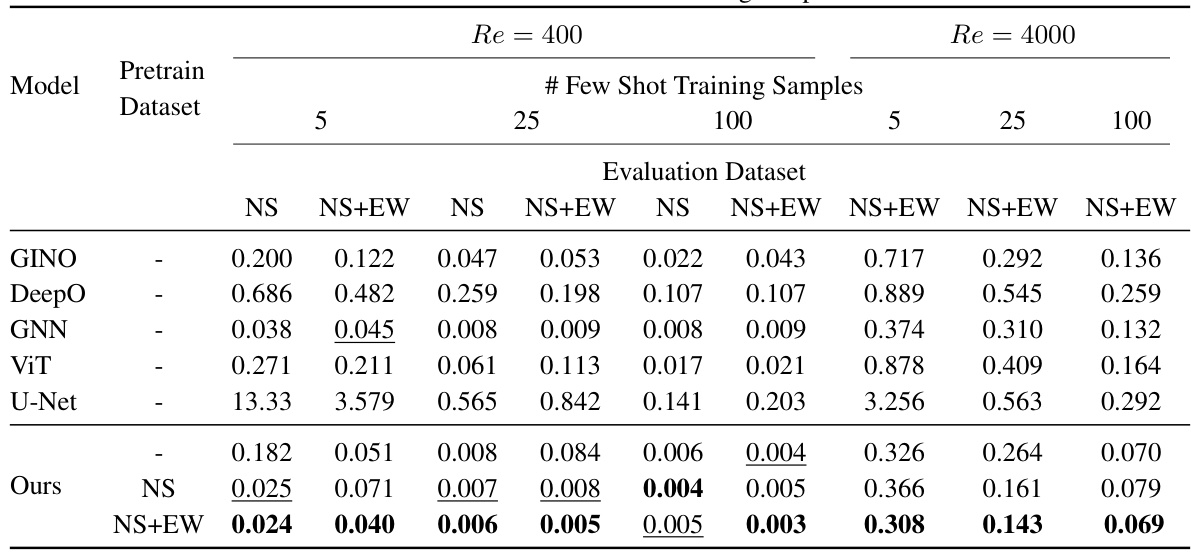

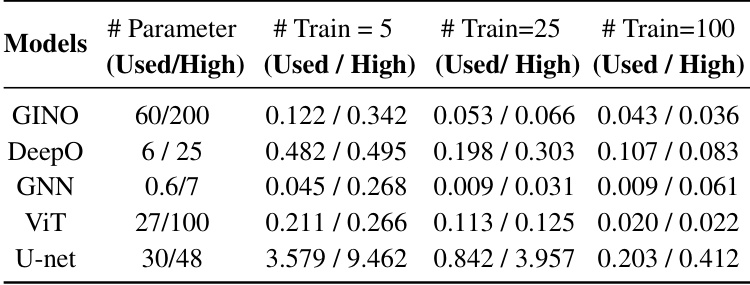

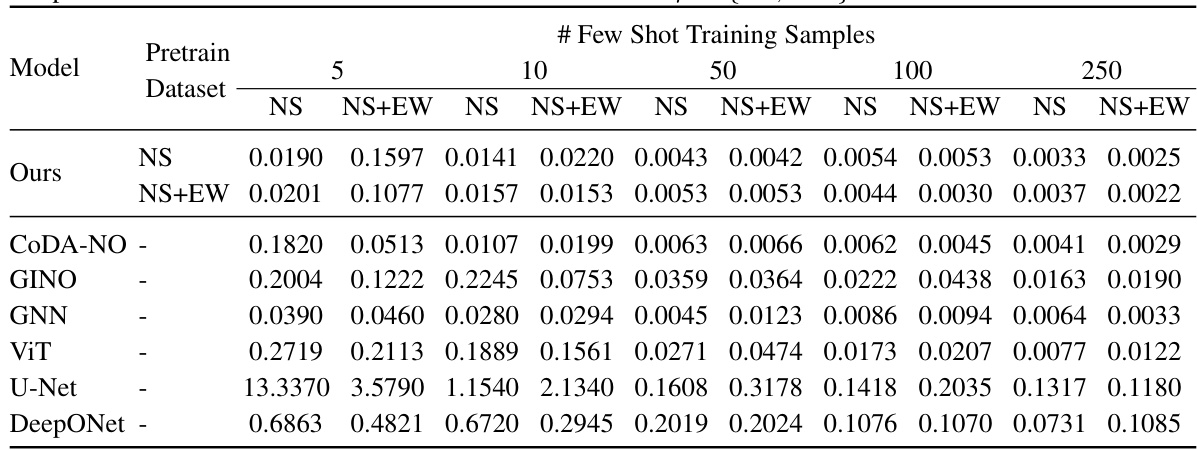

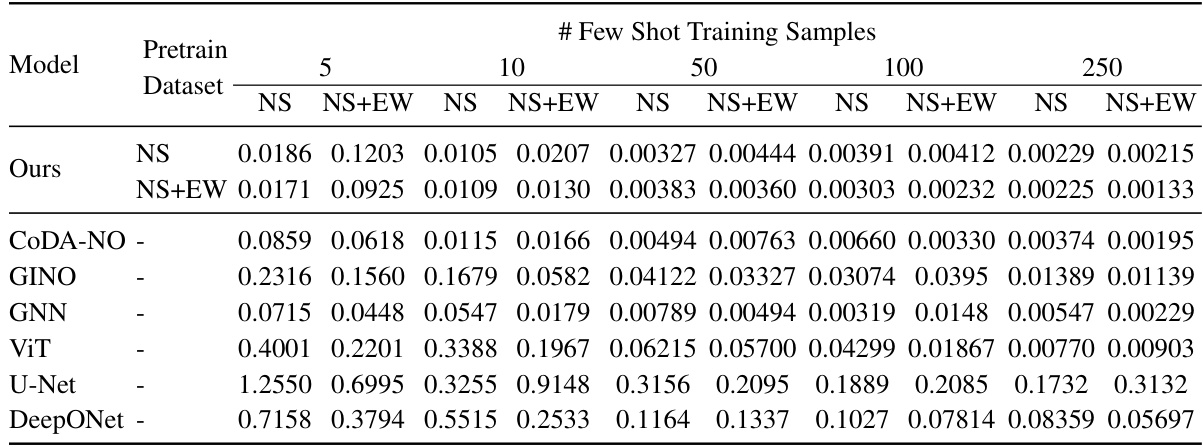

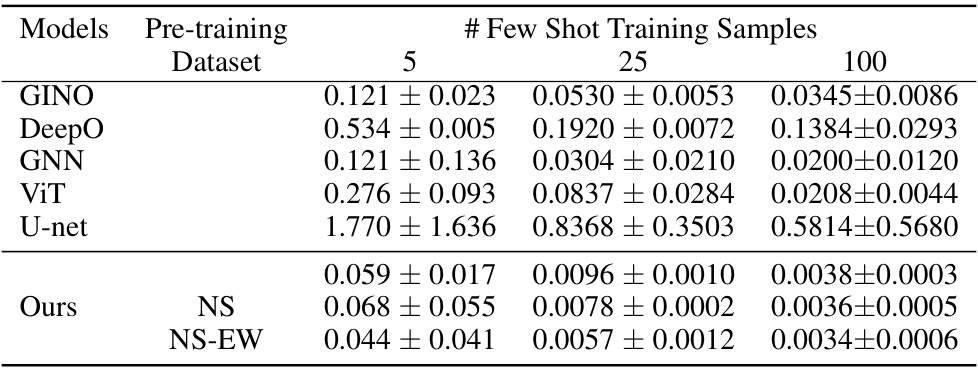

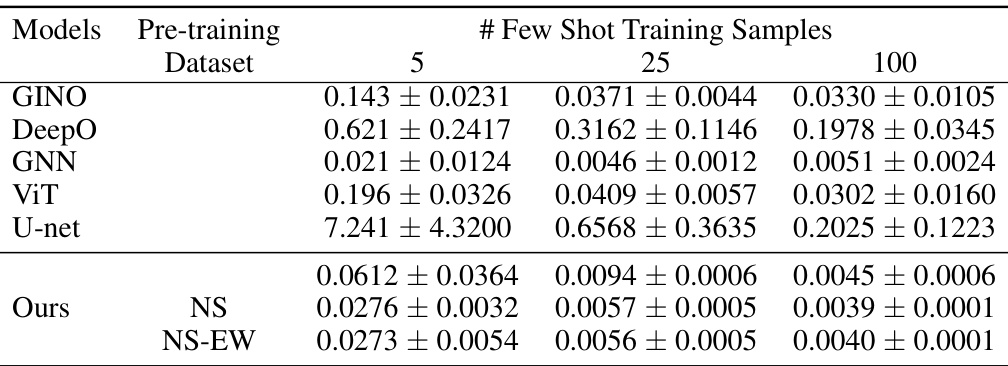

This table presents the test L2 loss for fluid dynamics and fluid-structure interaction datasets. It shows the performance of different models (GINO, DeepO, GNN, ViT, U-Net, and the proposed CoDA-NO) with varying numbers of few-shot training samples (5, 25, 100) and two Reynolds numbers (Re = 400 and Re = 4000). The results are split by evaluation dataset (NS and NS+EW) and whether or not CoDA-NO was pre-trained on either NS or NS+EW datasets. This allows for comparison of the performance of the models when using data from different scenarios (fluid only or fluid-structure interaction) and with varying amounts of training data.

In-depth insights#

Multiphysics PDEs#

Multiphysics PDEs represent a significant challenge in scientific computing due to the complex interplay of various physical phenomena. Traditional numerical methods struggle with the computational cost and convergence issues associated with high-resolution simulations needed to accurately capture these interactions. Deep learning offers a potential avenue for faster and more efficient solutions, but existing neural operator architectures face limitations in handling coupled PDEs with complex geometries and limited training data. Key challenges include managing interactions between physical variables, handling varying resolutions and grids, and adapting to new, unseen PDE systems or variables. Successful approaches require innovative techniques like codomain attention mechanisms to efficiently learn solution operators across multiple coupled PDEs, potentially utilizing self-supervised or few-shot learning strategies to improve generalization capabilities. A foundation model approach that leverages pre-training on simpler PDE systems can substantially benefit downstream multiphysics problem solving, demonstrating improved accuracy and efficiency.

CoDA-NO Model#

The CoDA-NO (Codomain Attention Neural Operator) model presents a novel approach to solving multiphysics PDEs by extending the transformer architecture to function spaces. Its core innovation lies in tokenizing functions along the codomain, enabling the model to handle varying combinations of physical phenomena. This allows for self-supervised pre-training on single-physics systems, which are then efficiently fine-tuned for multiphysics scenarios using limited data. The use of Fourier neural operators within the CoDA-NO architecture maintains discretization convergence, making the model robust across different resolutions and grid types. Codomain attention mechanisms, specifically designed for function spaces, capture cross-function dynamics, enabling superior performance compared to existing methods. The model’s flexibility in handling different numbers of input functions and geometries contributes to its generalizability and efficiency in multiphysics settings. Pre-training on simpler systems acts as a curriculum, progressively building towards more complex multiphysics problems. The use of GNO (Graph Neural Operators) further enhances its adaptability to irregular meshes and complex geometries often encountered in realistic multiphysics problems. Overall, CoDA-NO offers a powerful and adaptable framework for addressing the challenges of learning complex coupled PDE systems.

Few-Shot Learning#

Few-shot learning, in the context of solving multiphysics PDEs, is a crucial advancement. The limited availability of high-resolution training data for complex multiphysics systems is a major bottleneck. Traditional methods require massive datasets, which are expensive and time-consuming to obtain. This is where few-shot learning shines by drastically reducing the reliance on extensive training data. By leveraging pre-trained models or transfer learning techniques, few-shot learning enables the adaptation of models to new, unseen multiphysics PDEs with minimal additional training examples. This approach significantly lowers the computational cost and time needed for model development, allowing researchers to efficiently explore a wider range of complex systems. A key benefit is the ability to transfer knowledge learned from simpler, single-physics systems to more intricate, coupled multiphysics scenarios, essentially building a foundation model that generalizes across multiple systems. However, the effectiveness of few-shot learning hinges on the quality of the pre-training data and the design of the model architecture; therefore, careful selection of both and appropriate transfer learning strategies are essential. Future research should further investigate the optimal techniques for knowledge transfer and the development of robust, generalizable few-shot learning frameworks for tackling the ever-increasing complexities of multiphysics problems.

Foundation Models#

Foundation models represent a paradigm shift in machine learning, emphasizing the training of large-scale models on massive datasets to acquire broad, generalizable knowledge. Transfer learning becomes central; the pre-trained model, rather than being trained from scratch for each specific task, acts as a powerful initialization for downstream applications. This significantly reduces the need for task-specific data and training time, making it particularly beneficial in data-scarce domains, which is especially important in scientific machine learning applications. Self-supervised learning techniques are often employed to leverage unlabeled data during the pre-training phase, making these models even more efficient and scalable. However, the significant computational resources required for training and the potential for biases present in the large training datasets are important limitations that need to be considered. Furthermore, understanding and mitigating the emergent capabilities that arise from these large-scale models is an ongoing area of research. Despite the challenges, the potential of foundation models in accelerating scientific discovery and technological innovation across various fields is immense.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore improving CoDA-NO’s efficiency by investigating more efficient attention mechanisms or alternative neural operator architectures. Addressing the limitations of few-shot learning is crucial, perhaps by developing novel data augmentation techniques or incorporating prior knowledge about the underlying physics. Extending CoDA-NO to handle more complex multiphysics systems involving different spatial dimensions and variable types, or those with stochastic elements, presents a significant challenge. Finally, a deep dive into the theoretical understanding of CoDA-NO’s convergence properties and generalization abilities would strengthen its foundation and lead to more robust and reliable applications. Integrating physics-informed methods with CoDA-NO could further enhance accuracy and efficiency in solving PDEs, allowing for more accurate and reliable solutions with less data. The development of more sophisticated and interpretable ways to analyze the attention mechanisms and latent features will facilitate a better understanding of the learned relationships between physical variables and improve the model’s trustworthiness.

More visual insights#

More on figures

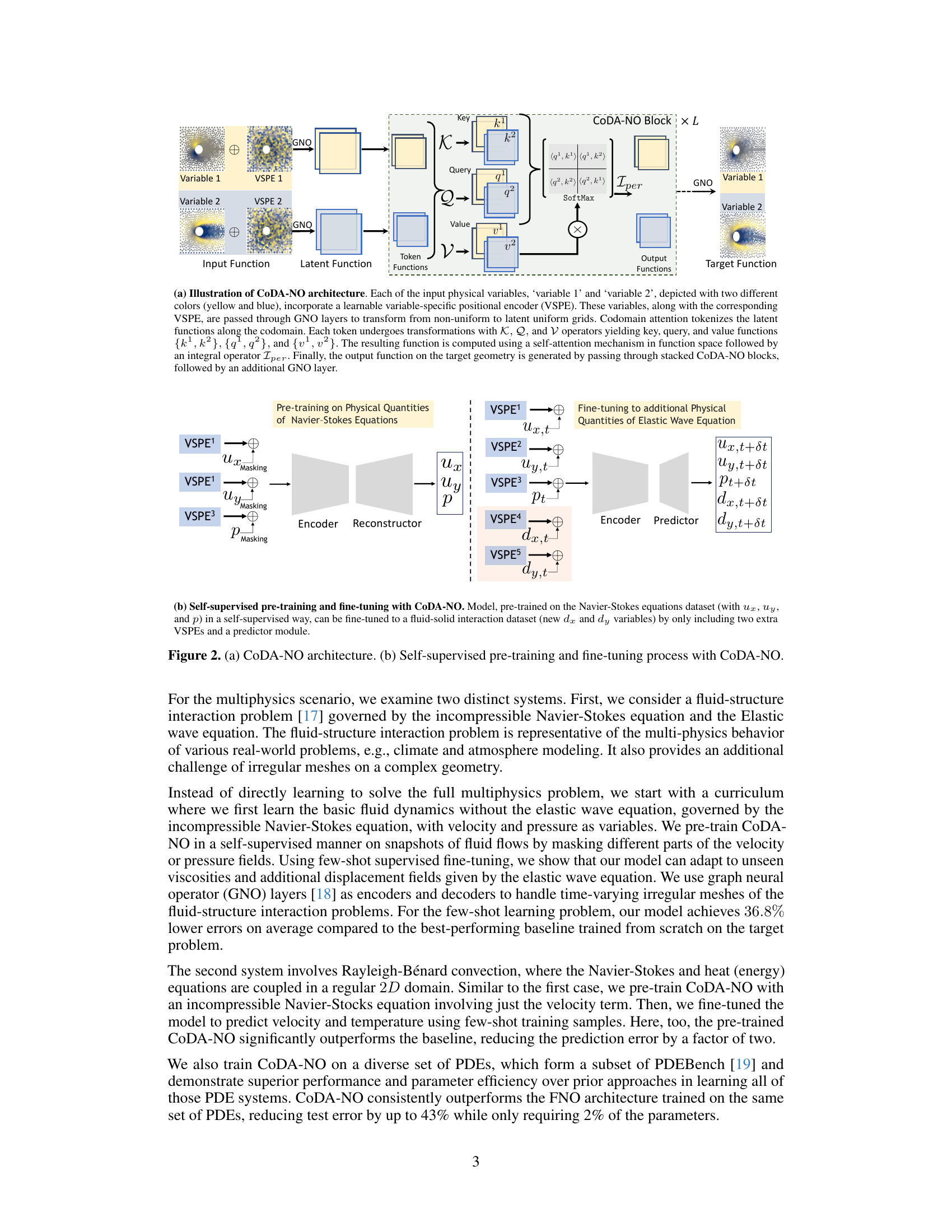

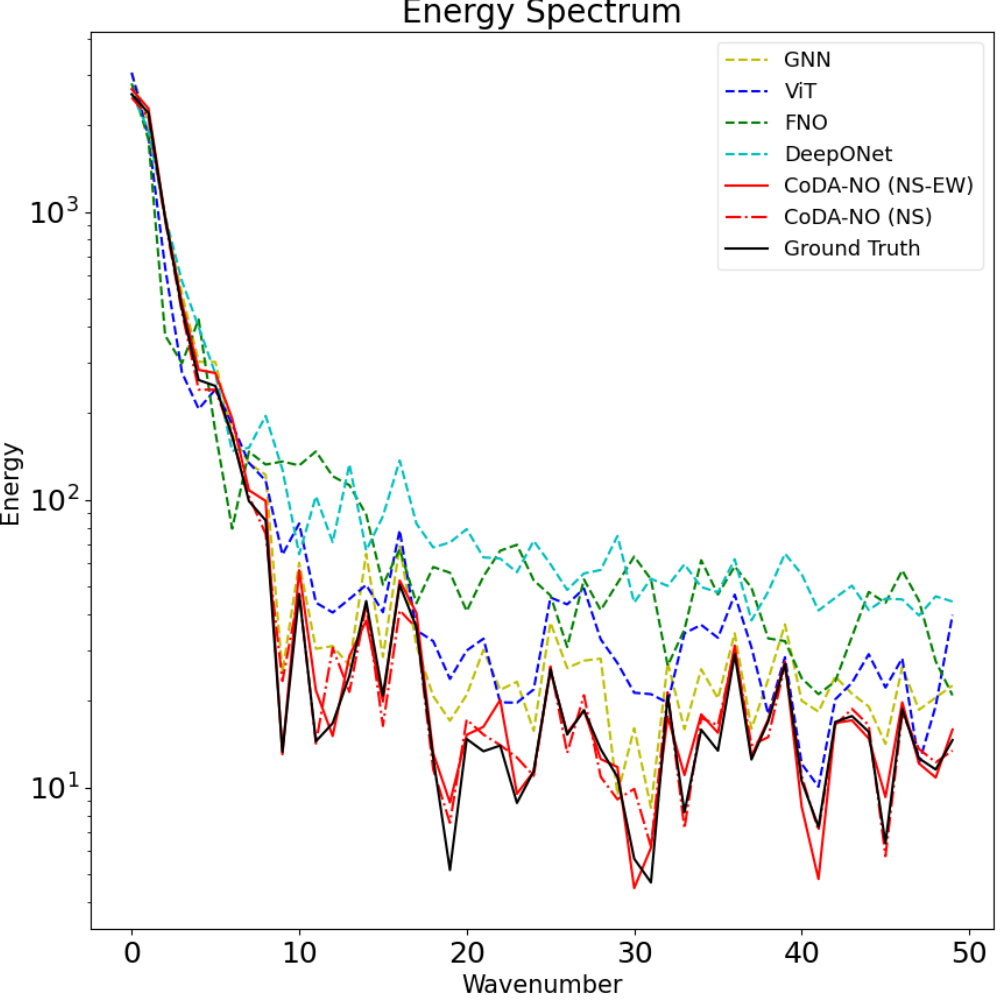

Figure 2(a) shows the detailed architecture of the CoDA-NO model, illustrating the processing of input functions through variable-specific positional encoders (VSPEs), graph neural operators (GNOs), and codomain attention blocks. The figure highlights the tokenization of functions, attention mechanisms in function space, and the final generation of output functions. Figure 2(b) depicts the two-stage training process: self-supervised pre-training on a single-physics system (Navier-Stokes) and subsequent fine-tuning on a multi-physics system (fluid-structure interaction), showing how the model adapts to new variables without major architectural changes.

This figure illustrates how the proposed CoDA-NO model can be pre-trained on a single-physics system (fluid dynamics governed by the Navier-Stokes equations) and then easily adapted to a multi-physics system (fluid-structure interaction) by simply adding new variables without changing the architecture. This demonstrates the model’s ability to generalize to new systems with minimal additional training.

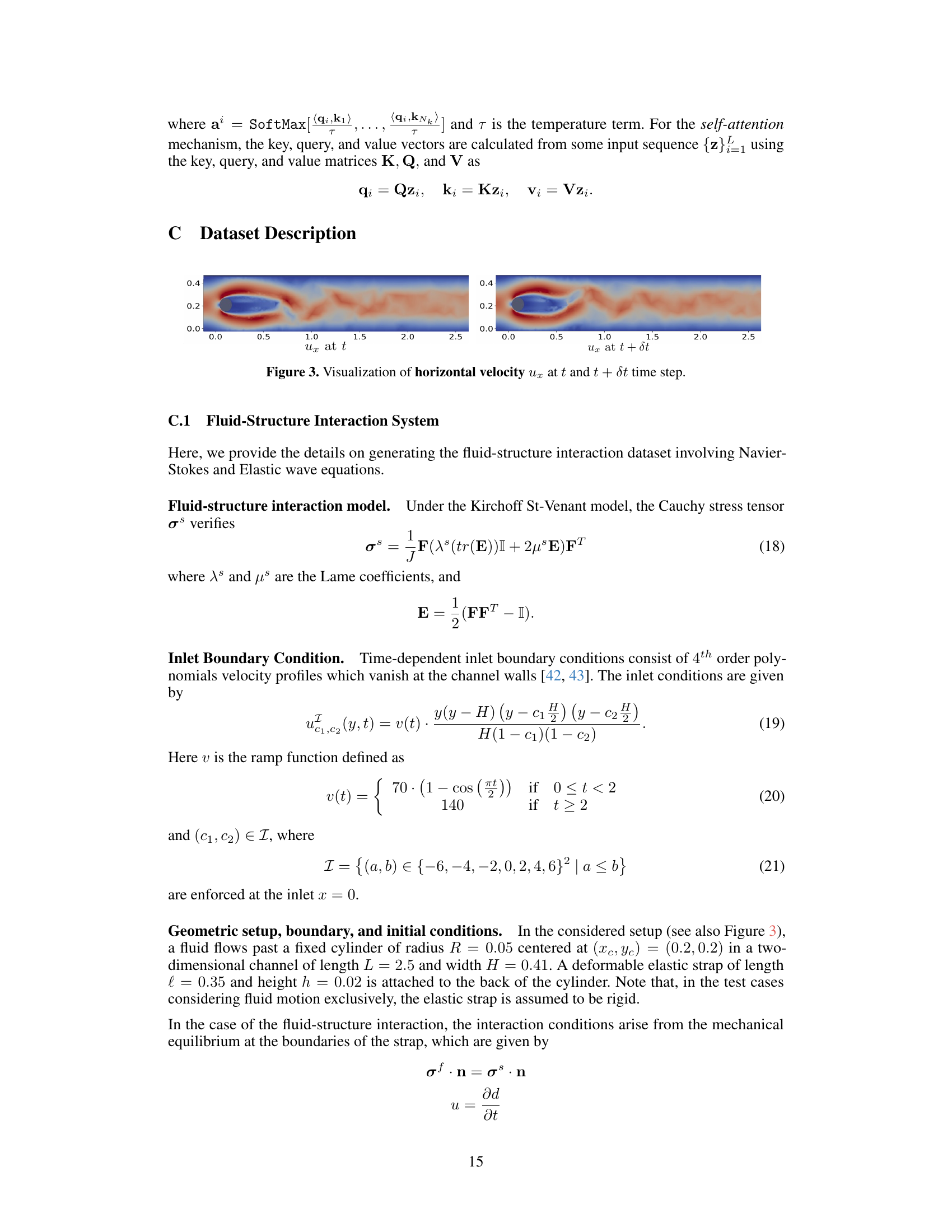

This figure shows the horizontal velocity (ux) at two different time steps, t and t + δt, for the fluid-structure interaction system. The visualization helps illustrate the change in the velocity field over a short time interval, highlighting the dynamic nature of the fluid flow around the cylinder and elastic strap.

This figure illustrates the adaptability of the CoDA-NO model to new multi-physics systems. The model, pre-trained on a single-physics system (fluid dynamics), is shown to easily adapt to a coupled multi-physics system (fluid-structure interaction) without requiring architectural changes. This highlights the model’s ability to learn representations across different PDE systems and transfer that knowledge to new, unseen problems, mimicking the success of foundation models in other domains like computer vision and natural language processing.

This figure visualizes the horizontal velocity (ux) predicted by the CoDA-NO model for a fluid-structure interaction problem. It shows a comparison of the ground truth velocity (a), the CoDA-NO’s prediction (b), and the error between the prediction and the ground truth (c). The visualization helps to assess the accuracy of the CoDA-NO model in predicting the fluid dynamics in this complex scenario.

More on tables

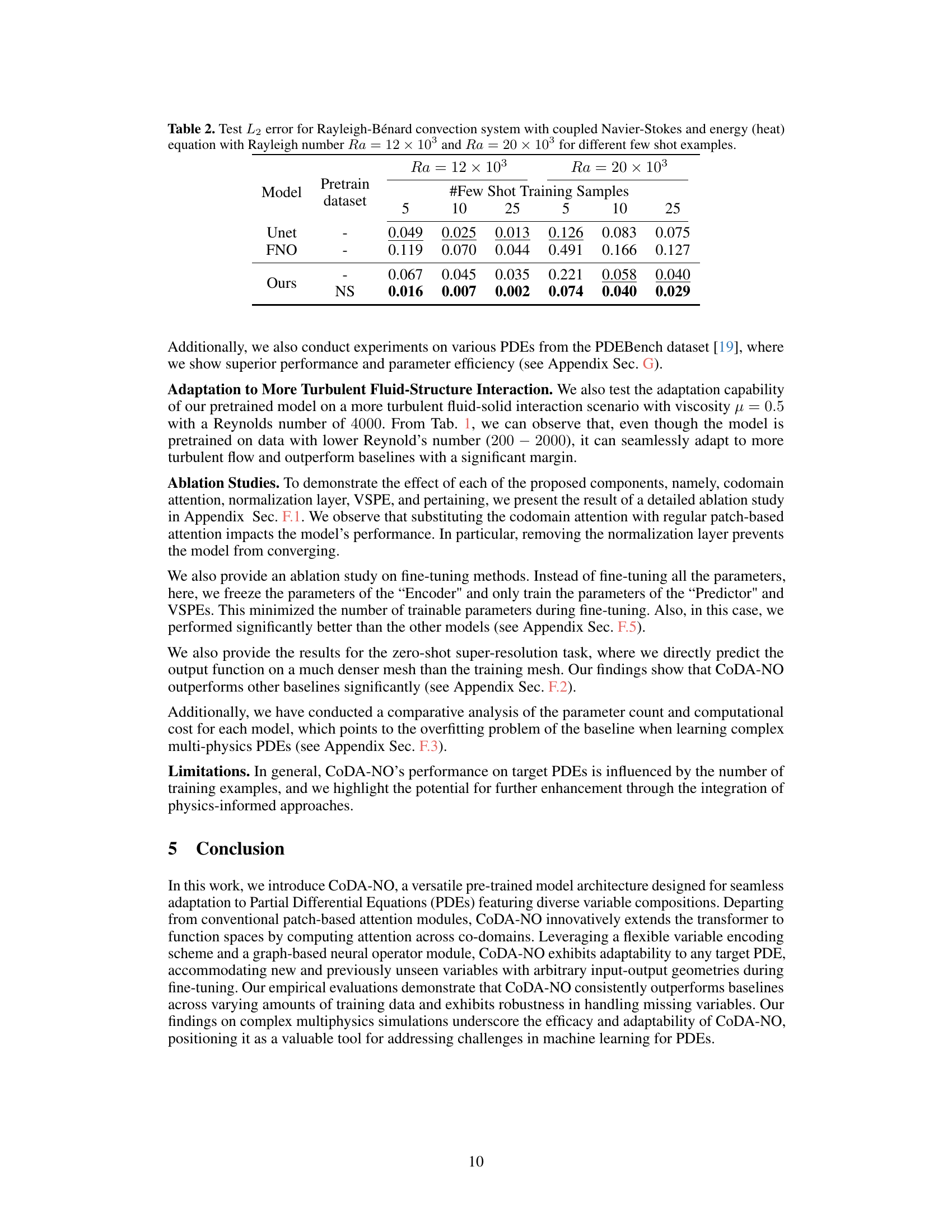

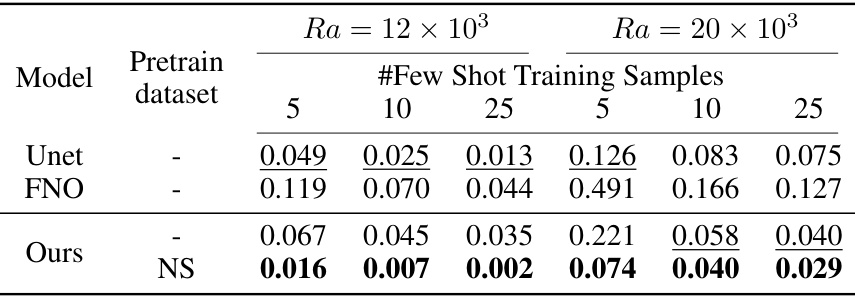

This table presents the test L2 error results for the Rayleigh-Bénard convection system, comparing the performance of Unet, FNO, and the proposed CoDA-NO model across different Rayleigh numbers (Ra = 12 × 10^3 and Ra = 20 × 10^3) and varying numbers of few-shot training samples (5, 10, 25). It highlights the performance improvement of CoDA-NO, especially when limited training data is available.

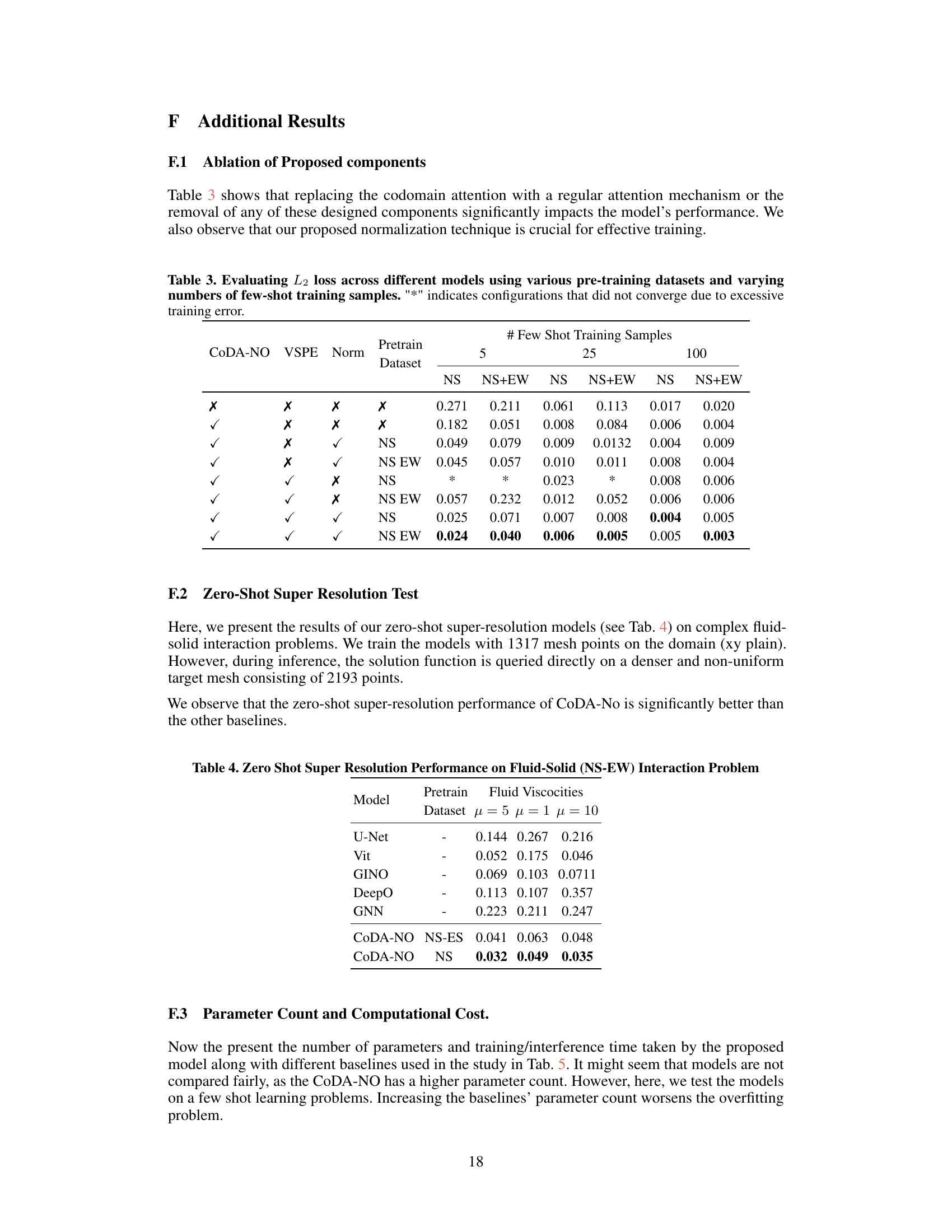

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the CoDA-NO model. It shows the impact of removing or changing different components of the model (codomain attention, VSPE, normalization) on its performance. Different pre-training datasets (NS, NS+EW) and varying numbers of few-shot training samples (5, 25, 100) are used. The ‘*’ indicates that the model did not converge during training for those configurations.

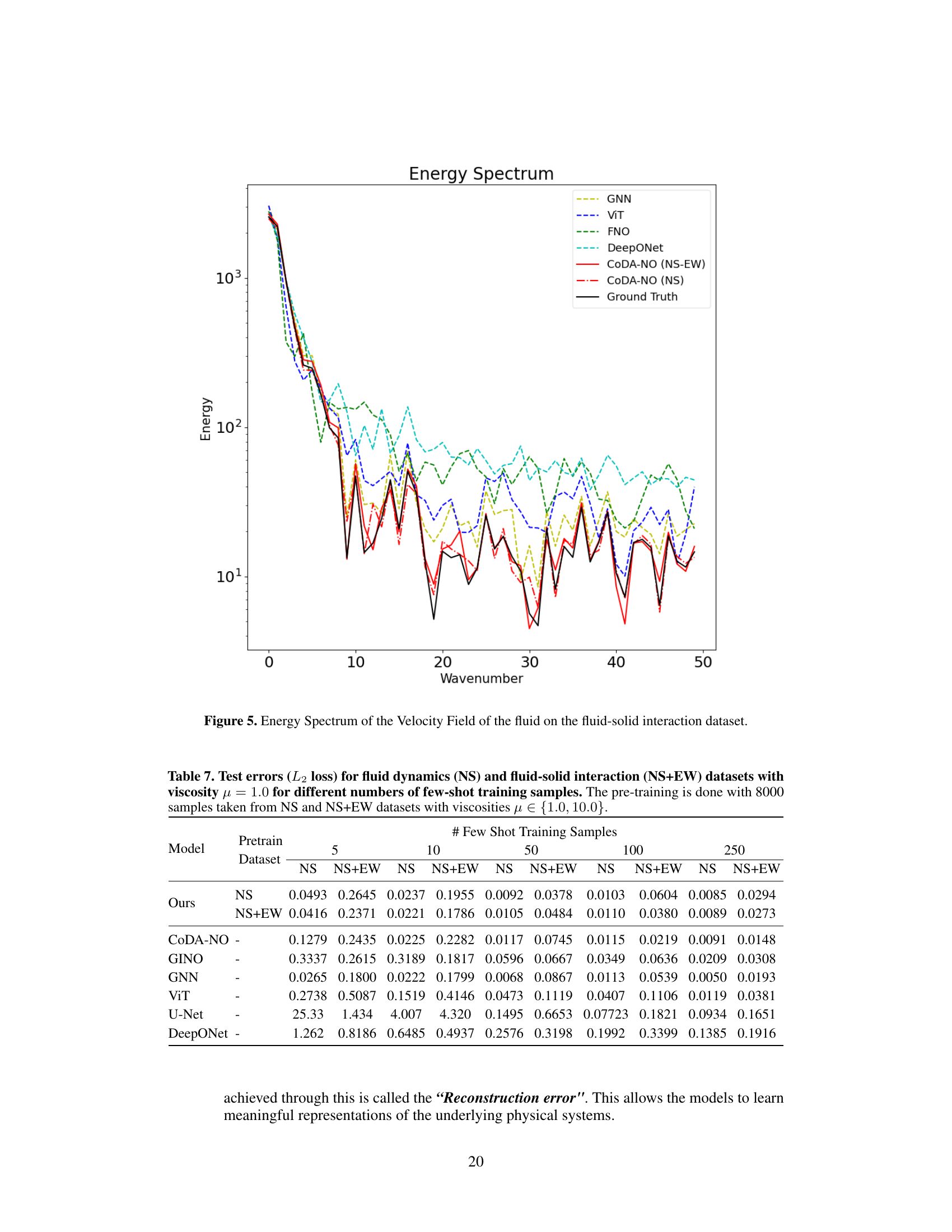

This table compares the zero-shot super-resolution performance of different models on the fluid-solid interaction problem. The models are tested on unseen fluid viscosities (μ = 5, μ = 1, μ = 10) after being pretrained on different datasets (NS-ES and NS). The results show the L2 error for each model and viscosity, highlighting the superior performance of CoDA-NO in this zero-shot setting.

This table compares the performance of different models (GNN, GINO, DeepO, ViT, Unet, and CoDA-NO) in terms of inference time, training time per sample, and the number of parameters. The data allows for a comparison of efficiency and computational resource requirements across these models.

This table presents the L2 loss (a measure of error) for two different datasets: fluid dynamics (NS) and fluid-structure interaction (NS+EW). The experiments were conducted with two different Reynolds numbers (Re=400 and Re=4000) representing different fluid viscosities and varying numbers of few-shot training samples (5, 25, and 100). The table compares the performance of different models in handling these datasets with limited data.

This table presents the test L2 loss for fluid dynamics and fluid-solid interaction datasets using different numbers of few-shot training samples. The results are broken down by model (GINO, DeepO, GNN, ViT, U-Net, Ours), pretraining dataset (NS, NS+EW), and the number of few-shot training samples (5, 25, 100). It allows for comparison of different models’ performance on different datasets under varying data scarcity conditions.

This table shows the test L2 loss for two datasets, fluid dynamics (NS) and fluid-solid interaction (NS+EW), with two different Reynolds numbers (400 and 4000). The table compares the performance of several models (GINO, DeepO, GNN, ViT, U-Net, and Ours) under different numbers of few-shot training samples (5, 25, 100). The ‘Ours’ model refers to the CoDA-NO model proposed in the paper. The results show how well each model generalizes to unseen data with limited training examples.

This table presents the test L2 loss for fluid dynamics (NS) and fluid-solid interaction (NS+EW) datasets. The results are shown for two Reynolds numbers (Re = 400 and Re = 4000) and different numbers of few-shot training samples (5, 25, 100). It allows comparison of the performance of various models (GINO, DeepONet, GNN, ViT, U-Net, and the proposed CoDA-NO) under different data regimes.

This table presents the test L2 loss for two datasets, fluid dynamics (NS) and fluid-solid interaction (NS+EW), across different models and varying numbers of few-shot training samples. The results are shown for two Reynolds numbers (Re = 400 and Re = 4000) to demonstrate the model’s performance under different flow conditions. The models tested include several baselines (GINO, DeepO, GNN, ViT, U-Net) and the proposed CoDA-NO model with and without pretraining on different datasets. The table allows comparison of model performance given limited data for both single-physics and multi-physics scenarios.

The table presents the test L2 loss for fluid dynamics (NS) and fluid-solid interaction (NS+EW) datasets. The results are shown for two different viscosities (μ = 400 and μ = 4000) and varying numbers of few-shot training samples (5, 25, 100). It compares the performance of the proposed CoDA-NO model against several baseline methods (GINO, DeepO, GNN, ViT, U-Net). The table helps to evaluate the generalization ability and sample efficiency of the CoDA-NO model in handling multiphysics problems with limited data.

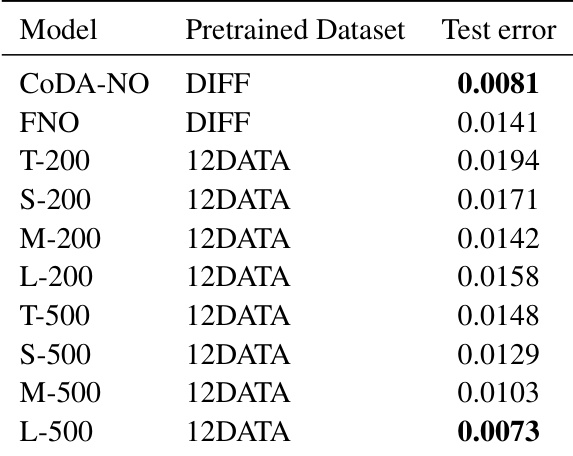

This table compares the performance of CoDA-NO and FNO on three single-physics PDE datasets from PDEBench: Shallow Water Equations (SWE), Diffusion Equations (DIFF), and a combined dataset of Navier-Stokes, Diffusion, and Shallow Water Equations (NS+DIFF+SWE). It shows the prediction error and reconstruction error for each model and dataset.

This table compares the number of parameters of the CoDA-NO model with several baselines: FNO and DPOT. The table shows that CoDA-NO has significantly fewer parameters than FNO, and is comparable to the smaller versions of DPOT.

This table compares the performance of CoDA-NO and FNO on three single-physics PDE datasets from PDEBench. It shows the prediction error for each model when pretrained on the SWE dataset and a dataset comprised of 12 different PDEs, with different finetuning epochs. The results highlight CoDA-NO’s superior generalization abilities, particularly when pretrained on a broader dataset.

This table compares the performance of CoDA-NO and FNO on three single-physics datasets from the PDEBench dataset. It shows the test error (L2 error) for both models on the Shallow Water Equation (SWE) and Diffusion Equation (DIFF) datasets. Additionally, it includes results where both models were pre-trained on a combined dataset of 12 PDEs (12DATA) and then fine-tuned on the SWE and DIFF datasets separately for 200 and 500 epochs.

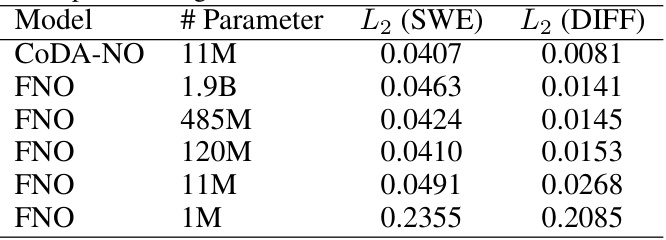

This table compares the performance of CoDA-NO and FNO models with varying numbers of parameters on two different PDE datasets: Shallow Water Equation (SWE) and Diffusion-Reaction (DIFF). It shows the L2 error for each model on both datasets. The table highlights the relationship between model size (# parameters) and prediction accuracy (L2 error).

Full paper#