↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computer vision and AI, particularly those working on image retrieval and responsible AI. It directly addresses the significant problem of misalignment between vision models and human aesthetic preferences, a challenge hindering the widespread adoption of AI-powered retrieval systems. By introducing a novel method combining large language models, reinforcement learning, and novel benchmarks, this research opens exciting new avenues for developing more human-centric and responsible AI systems. Its findings will likely influence future retrieval algorithms and inspire related work concerning AI alignment with human values.

Visual Insights#

This figure shows four examples of image retrieval tasks where a model’s output is compared with and without alignment to human aesthetics. In each example, the left image shows results without any alignment, where the model may violate user intent by providing harmful or inappropriate content. The right image shows results with human aesthetic alignment, where the model prioritizes user safety and intent, thus providing more appropriate results. These examples demonstrate the importance of aligning models with human values.

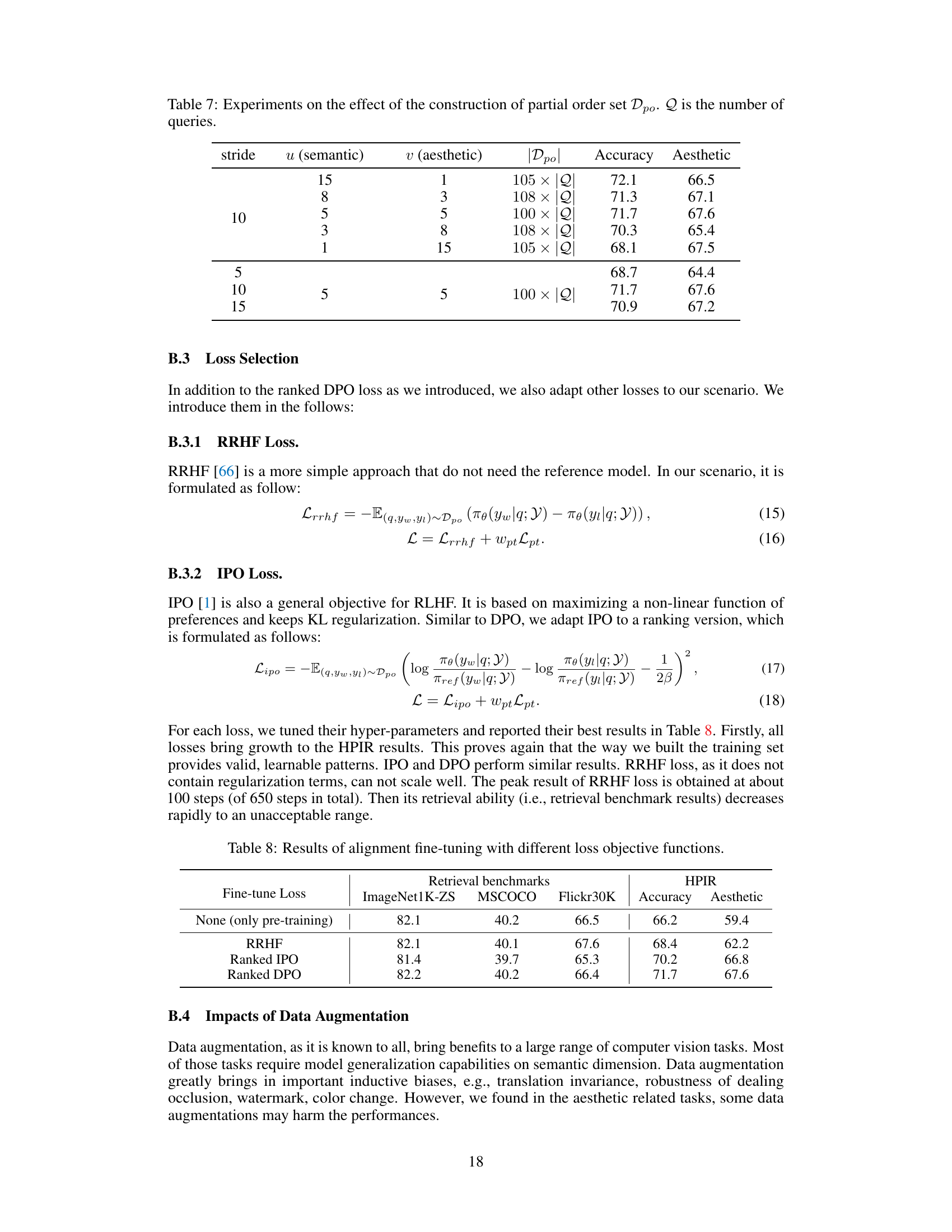

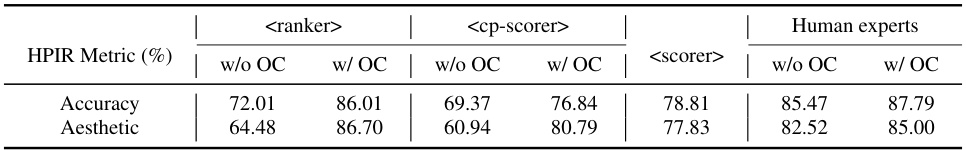

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different models on standard image retrieval benchmarks (ImageNet1K zero-shot classification, MSCOCO T2I retrieval, and Flickr30K T2I retrieval) and a newly proposed aesthetic alignment dataset (HPIR). The models compared are CLIP, DataComp, and the authors’ model, both before (PT) and after (RLFT) the proposed reinforcement learning fine-tuning for aesthetic alignment. The table highlights the impact of the fine-tuning on both traditional retrieval metrics and the aesthetic scores, showing improvements in the latter after the fine-tuning.

In-depth insights#

Aesthetic Alignment#

The concept of ‘Aesthetic Alignment’ in the context of vision models centers on bridging the gap between the output of AI systems and human aesthetic preferences. The paper tackles the inherent challenge of large-scale vision models trained on noisy datasets, often resulting in outputs that deviate from human ideals of beauty or artistic merit. The core idea involves using a preference-based reinforcement learning method to fine-tune vision models, leveraging the reasoning capabilities of large language models (LLMs) to interpret and refine user search queries. This approach surpasses traditional aesthetic models by incorporating high-level context and understanding, leading to more nuanced and human-aligned results in image retrieval tasks. The inclusion of a novel dataset specifically designed for evaluating aesthetic performance further highlights the commitment to rigorous benchmarking and validation of the proposed alignment methodology. This combination of LLMs, reinforcement learning, and a specialized benchmark represents a significant contribution to creating visually appealing and human-centered AI systems.

LLM Query Enhancements#

LLM query enhancements represent a significant advancement in bridging the gap between human aesthetic perception and machine-driven image retrieval. By leveraging the reasoning capabilities of large language models (LLMs), the approach moves beyond simplistic keyword matching. LLMs enrich queries with nuanced descriptions, stylistic preferences, and contextual details, effectively guiding the retrieval system towards more aesthetically pleasing and relevant results. This addresses the inherent limitations of traditional methods, which often struggle with subjective concepts like ‘beauty’ or ‘artistic style’. The effectiveness hinges on carefully crafting prompts that instruct the LLM to expand the initial query appropriately, highlighting the importance of prompt engineering in achieving desired outcomes. Evaluating the impact of LLM query enhancements requires comprehensive benchmarking, comparing retrieval performance against human judgment and traditional methods. This highlights the subjective nature of aesthetics and necessitates a multifaceted evaluation strategy. The use of LLMs in this way holds significant potential for various applications requiring alignment with human preference in retrieval tasks, going beyond simple image search and impacting fields such as product recommendation and content generation.

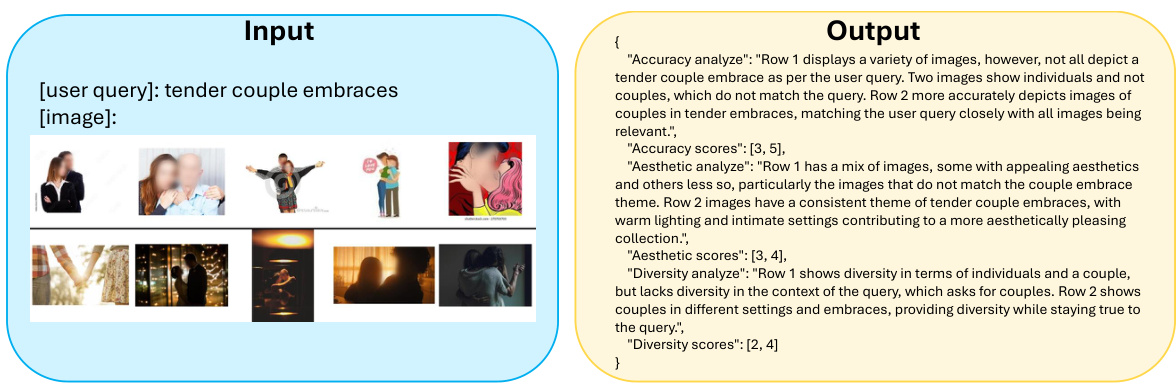

HPIR Benchmark#

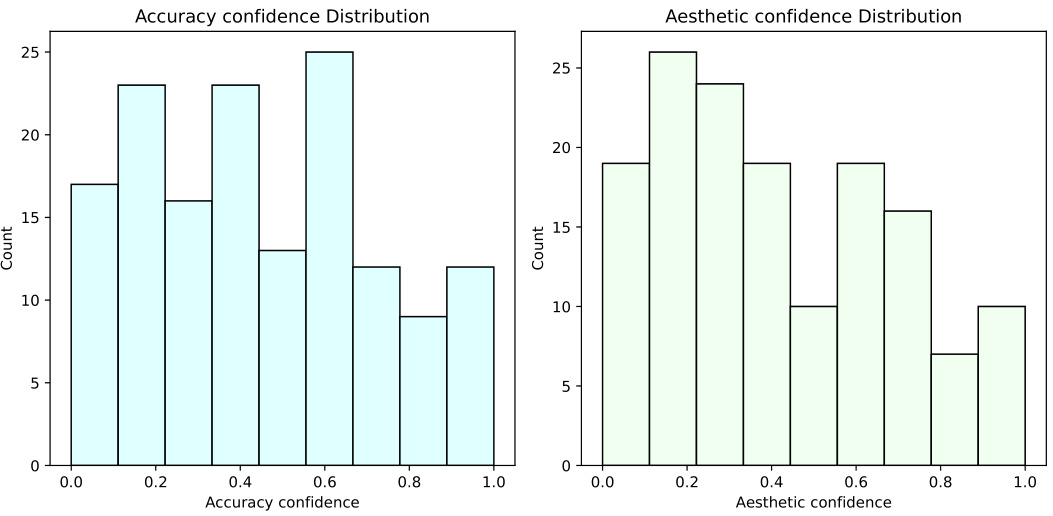

The HPIR benchmark, a novel dataset introduced for evaluating aesthetic alignment in image retrieval systems, is a significant contribution. Its core strength lies in directly assessing the alignment of model outputs with human aesthetic preferences, a critical but often overlooked aspect of visual search. Unlike existing benchmarks focused primarily on semantic accuracy, HPIR uses human judgments of aesthetic appeal to evaluate retrieval performance. This involves comparisons of image sets—allowing for a nuanced assessment of the subtle visual qualities that contribute to overall aesthetic satisfaction. The use of multiple human annotators and a confidence score for each assessment enhances the reliability and robustness of the results. By incorporating human feedback, HPIR helps bridge the gap between objective technical evaluation and subjective user experience. The benchmark’s design facilitates more holistic model evaluation, going beyond simple accuracy metrics and instead emphasizing user-centric quality aspects. This focus is crucial for developing AI systems that genuinely cater to human preferences and expectations in image retrieval.

RLHF Fine-tuning#

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) fine-tuning is a crucial technique to align large language models (LLMs) with human preferences. In the context of visual aesthetic retrieval, RLHF fine-tuning refines a vision model to better reflect human aesthetic judgments. The method typically involves using a reward model, which could incorporate human ratings or preference comparisons, to guide the model’s learning. A preference-based reinforcement learning algorithm, often utilizing techniques like Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) or Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG), is employed to update the vision model’s parameters. The objective function optimizes the model to produce outputs that maximize the reward, effectively aligning the model’s aesthetic choices with human expectations. A crucial challenge in RLHF for visual aesthetics is defining and quantifying the reward signal. Subjective nature of aesthetics necessitates careful design of reward mechanisms, potentially leveraging multiple aesthetic models or human annotation to accurately capture diverse preferences. Furthermore, the efficiency of the RLHF process is important, as training can be computationally expensive. Strategies to accelerate learning, like efficient sampling techniques or carefully curated datasets, are essential for effective application of RLHF in aligning vision models with human aesthetic values.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore expanding the dataset’s scope to encompass diverse cultural aesthetics and investigate the impact of different LLM prompting strategies on aesthetic alignment. A crucial area would be refining the reinforcement learning algorithm to enhance its efficiency and robustness in handling subjective aesthetic judgments. Addressing the inherent biases in LLMs and large-scale datasets used for model training is essential to ensure fairness and prevent the perpetuation of harmful stereotypes. Moreover, future work should investigate the generalization capabilities of the proposed method to other domains and modalities beyond image retrieval, such as video and text. Finally, thorough evaluation of the ethical implications of aesthetic alignment, including potential biases and responsible AI considerations, is paramount.

More visual insights#

More on figures

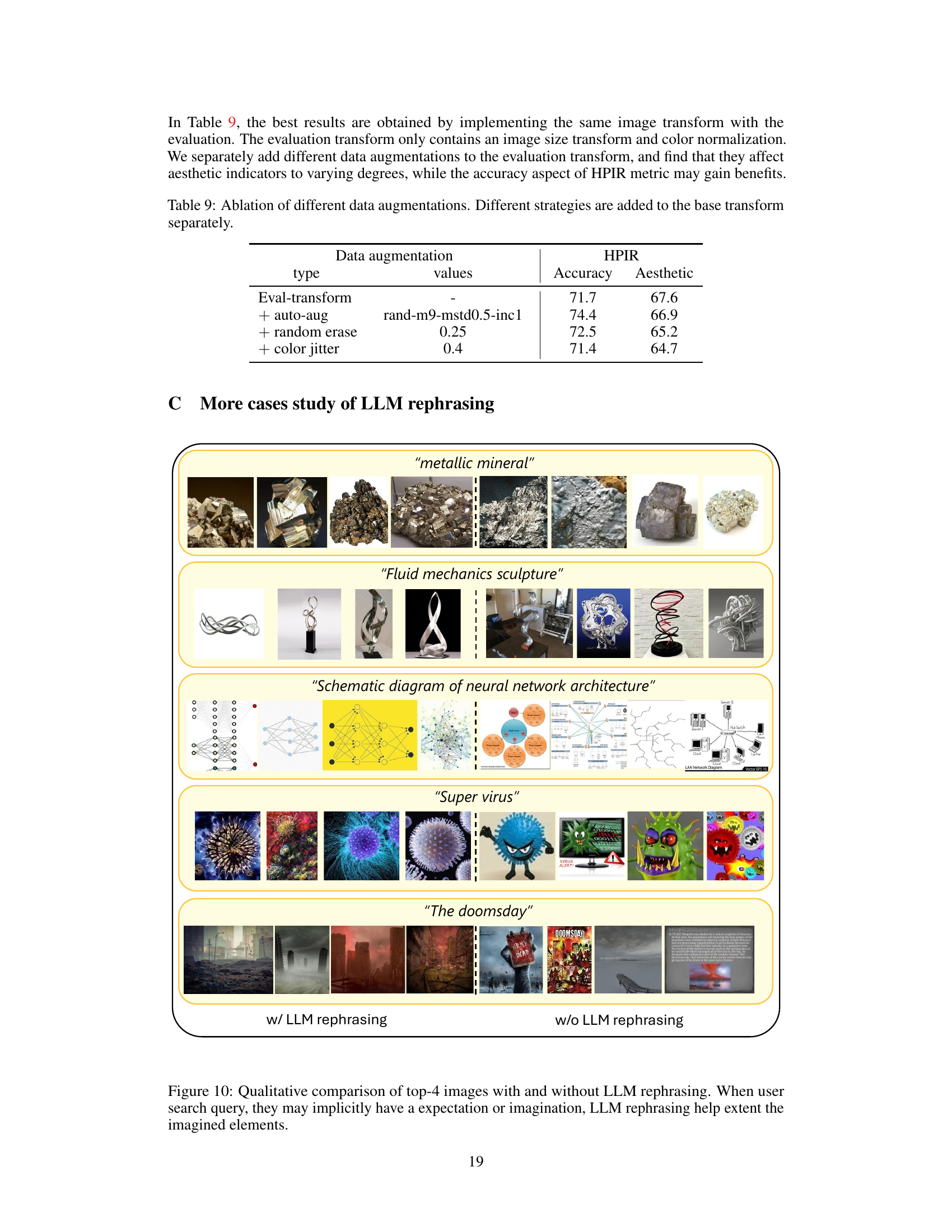

This figure illustrates the concept of aesthetics, which is broken down into two main components: understanding of beauty and image visual appeal. Understanding of beauty encompasses higher-level concepts like composition, symbolism, style, and cultural context, while image visual appeal focuses on lower-level features such as resolution, saturation, symmetry, and exposure. The figure then introduces the authors’ approach, which uses a combination of LLM rephrasing and an aesthetic model to align vision models with human aesthetics. This approach is further detailed in Figure 4.

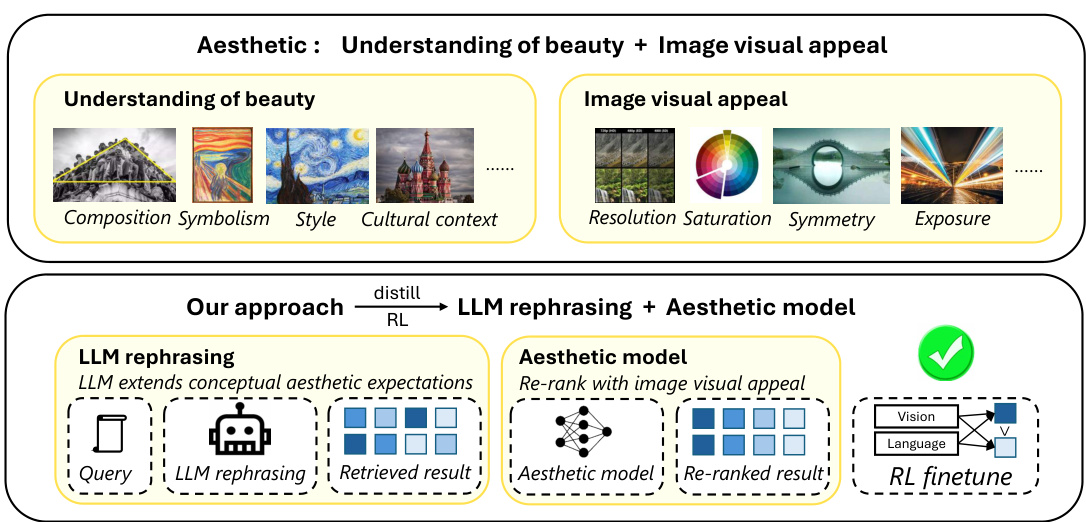

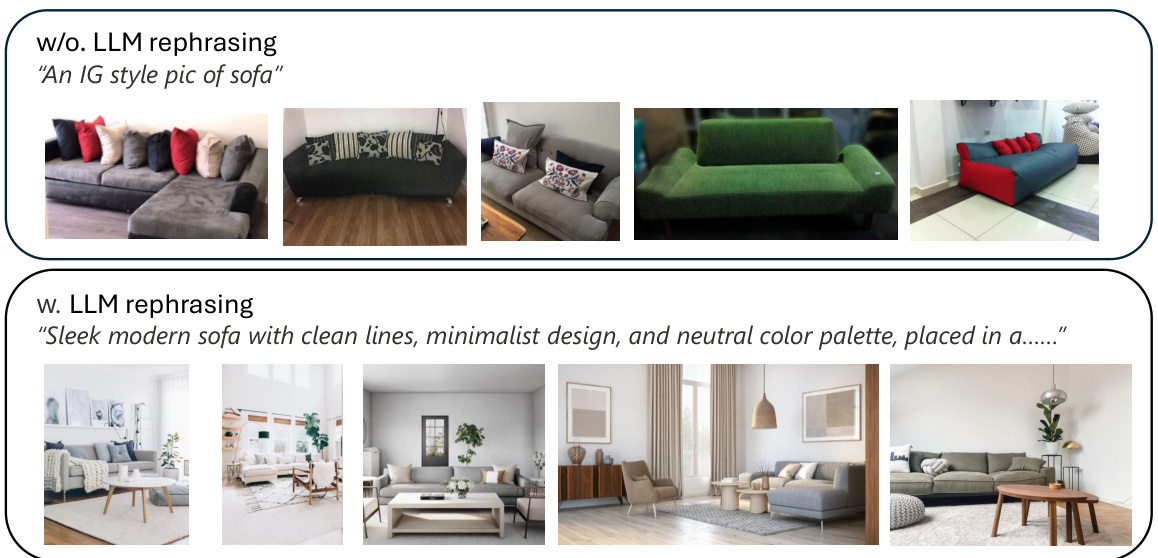

This figure shows a comparison of image retrieval results with and without LLM rephrasing. The top row shows results from a standard query, while the bottom shows results after the query has been enhanced with an LLM. The LLM-enhanced query produces results with noticeably improved aesthetics, showcasing the effectiveness of using LLMs to refine queries for aesthetic image retrieval.

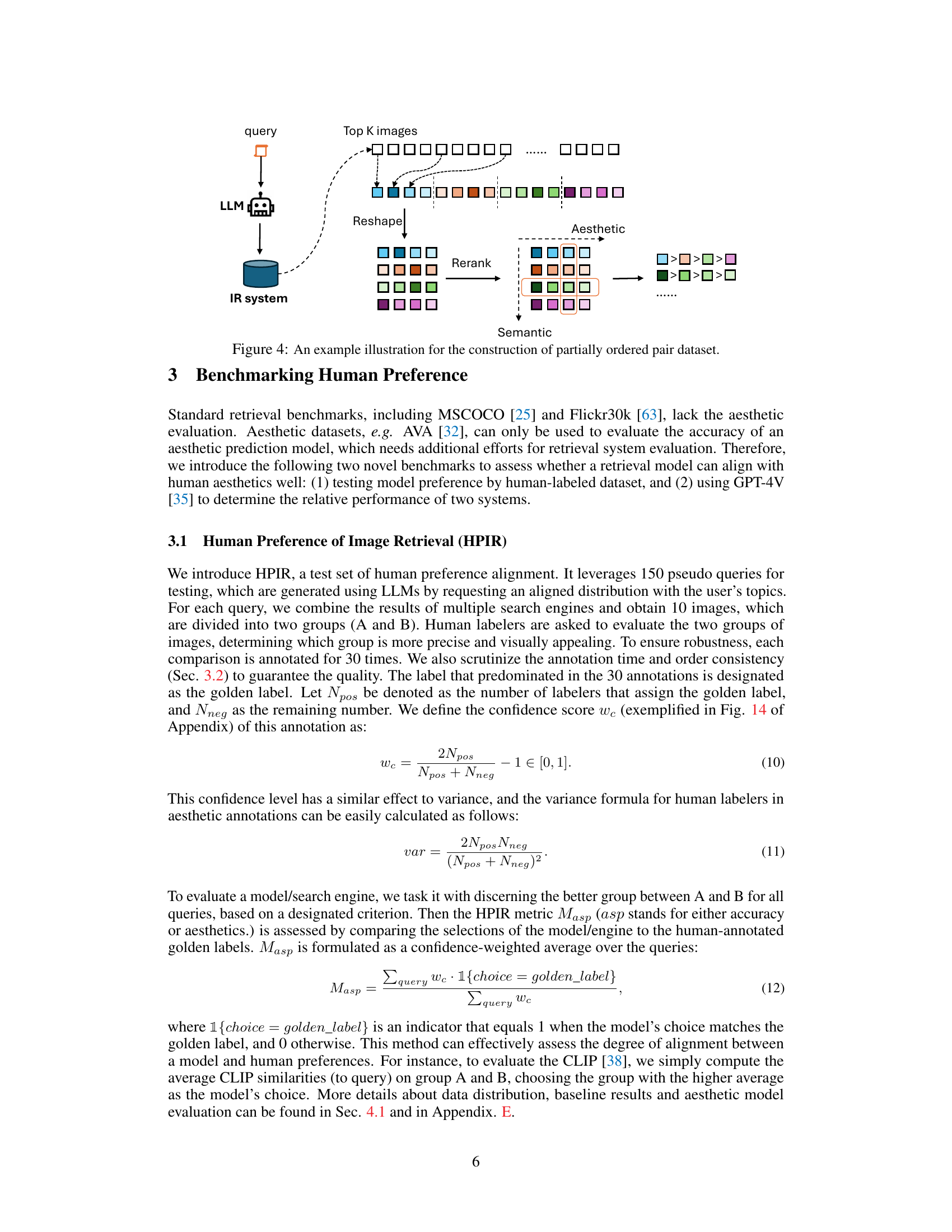

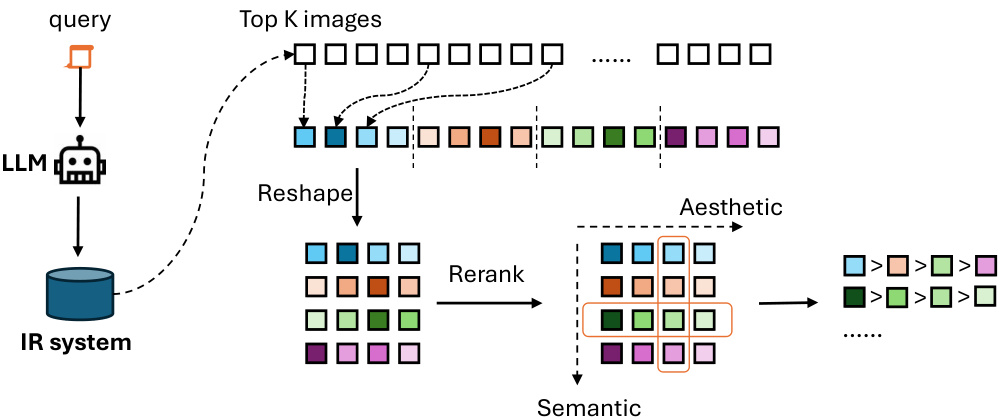

This figure illustrates the process of constructing a partially ordered dataset for training the retrieval model. It starts with a user query that’s fed into an LLM for rephrasing. The rephrased query is used to retrieve the top K images from an image retrieval (IR) system. These images are then re-ranked by both semantic and aesthetic models. Finally, a partially ordered dataset is created by intermittently selecting images from the re-ranked list, arranging them into a matrix, and extracting pairs based on semantic and aesthetic order. This dataset is then used to train the model with a preference-based reinforcement learning algorithm to align its output with human aesthetic preferences.

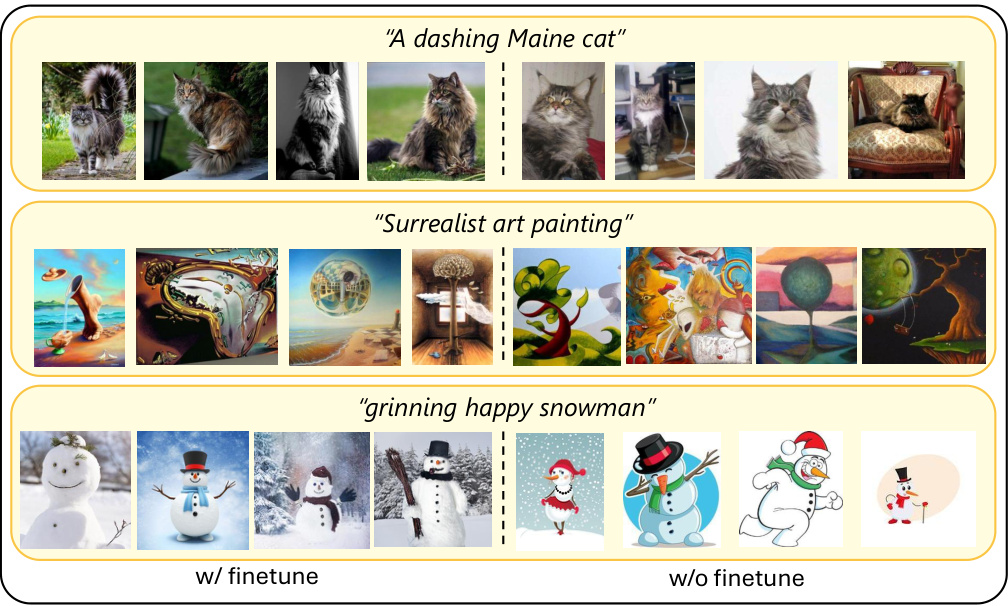

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of the top 4 retrieval results for three different search queries, using both the fine-tuned model and the original pretrained model. The queries are: ‘A dashing Maine cat’, ‘Surrealist art painting’, and ‘Grinning happy snowman’. For each query, the figure displays the top 4 results obtained from both models side-by-side. The visual comparison highlights how the proposed alignment fine-tuning improves the aesthetic quality and relevance of the retrieved images.

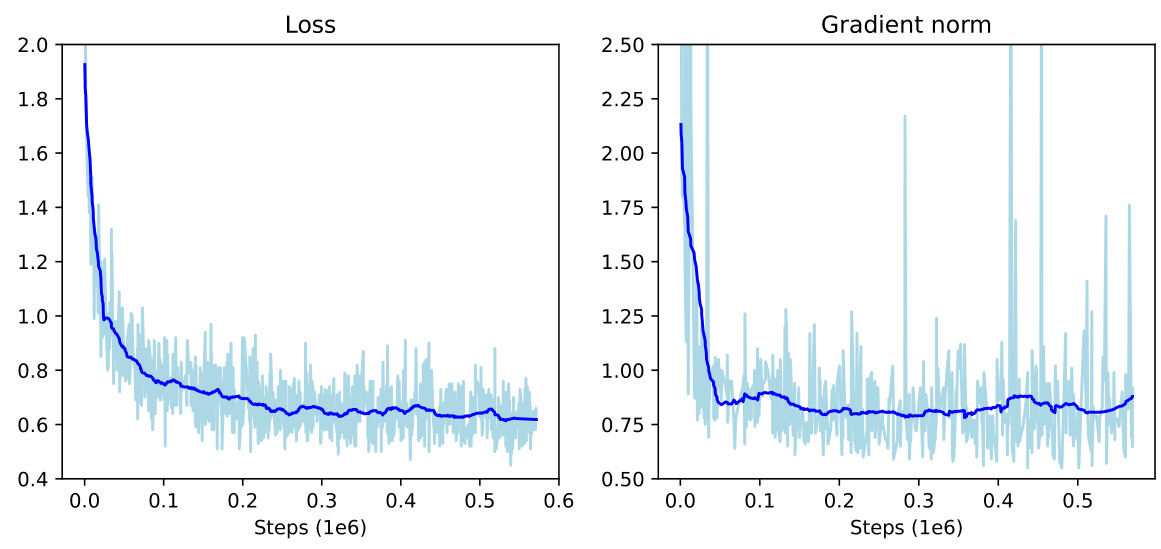

This figure shows the loss and gradient norm curves during the pre-training phase of the vision-language model. The light blue lines represent the loss and gradient norm for each step, while the dark blue lines represent the smoothed averages. The x-axis shows the training steps (in millions), and the y-axis shows the loss and gradient norm values.

This figure displays the performance of the model on three benchmark datasets (ImageNet1K zero-shot accuracy, MSCOCO T2I Recall@1, and Flickr30K T2I Recall@1) during the pre-training phase. Each plot shows the metric’s value across five epochs, illustrating the model’s improvement over time. The x-axis represents the epochs, and the y-axis represents the evaluation metric’s values.

This figure shows the loss and gradient norm curves during the pre-training phase of the vision-language model. The x-axis represents the training steps, while the y-axis shows the loss and gradient norm values. The curves illustrate the training process and convergence behavior of the model during pre-training.

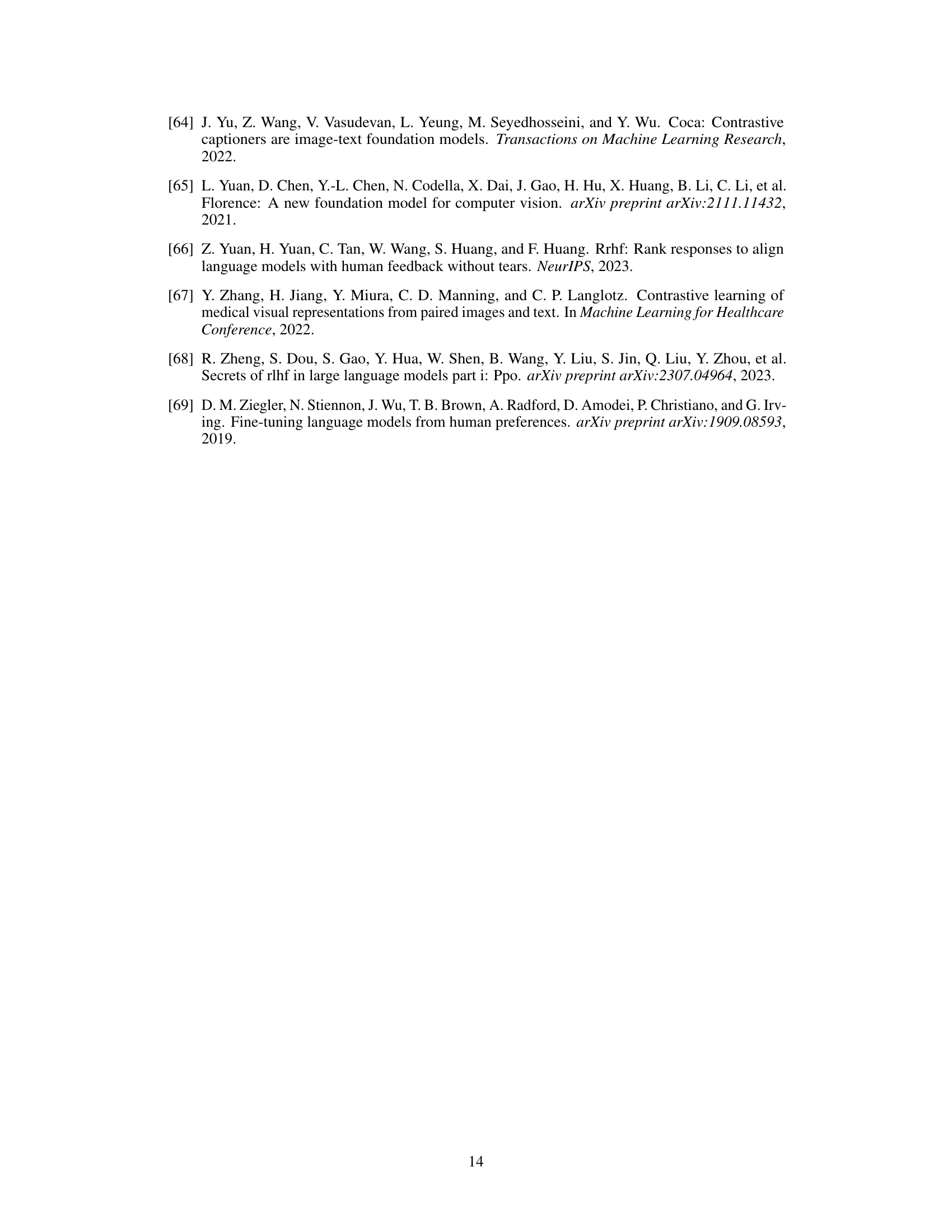

This figure displays the performance of the proposed model on several benchmark datasets (ImageNet1K zero-shot accuracy, MSCOCO T2I Recall@1, Flickr30K T2I Recall@1) and the custom HPIR dataset during the fine-tuning process. It shows the changes in performance metrics (accuracy, aesthetics, and diversity) over several training steps, indicating how the model’s alignment with human aesthetics evolves during fine-tuning. The plots visualize the trends of these metrics during the process, demonstrating the effect of the alignment fine-tuning on the various evaluation aspects.

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of the top 4 image retrieval results for five different queries with and without LLM rephrasing. The queries are designed to elicit abstract or imaginative responses (e.g., ‘metallic mineral’, ‘fluid mechanics sculpture’, ‘super virus’). The figure visually demonstrates that LLM rephrasing enhances the retrieval of images that better match the user’s implied aesthetic preferences and conceptual understanding of the query, extending beyond a literal interpretation of the keywords.

This figure shows a comparison of image retrieval results with and without using Large Language Models (LLMs) for query rephrasing. The top row displays example search queries. The two bottom rows show the top 4 retrieved images, respectively, with and without the LLM rephrasing. The examples highlight how using LLMs to rephrase queries enriched with cultural and knowledge contexts significantly improves the quality and relevance of the results. The results from queries without LLM rephrasing are often less coherent, relevant, or aesthetically pleasing, while those with LLM rephrasing more closely match the user’s intended meaning and aesthetic preferences.

This figure illustrates the order consistency strategy used in evaluating retrieval models with GPT-4V. Two calls to the GPT-4V API are made for each query, with the order of the results from the two systems (R1 and R2) reversed between calls. If both calls agree on which system is better, that result is recorded as a win. If the calls disagree, the results are considered similar. The goal is to mitigate any bias GPT-4V might have toward the order of presentation. The counter keeps track of wins for Result 1. If two calls show that Result 2 wins, the counter for Result 1 loses is incremented.

This figure illustrates the process of using GPT-4V as a judge to compare two retrieval models (R1 and R2). For each query, the model is presented with two sets of results (one from R1 and one from R2), each in a separate row. GPT-4V determines which set is better, and a count is added to the winning model. If both calls result in a win for R2, R1’s loss count increases by one. The ‘Similar’ counter tracks cases where the two calls disagree, indicating the results have minor differences in quality.

This figure illustrates the process of creating a partially ordered dataset for training the aesthetic alignment fine-tuning model. It begins with a query, which is then rephrased using an LLM to include explicit aesthetic expectations. The improved query is used to retrieve top-K images. These images are then re-ranked using both semantic and aesthetic models to produce a high-quality sequence. Finally, a subset of images are selected at intervals from this ranked sequence to create a partially ordered set, where images within a row are ordered by aesthetic quality and images across rows are ordered by semantic relevance. This dataset is then used in the preference-based reinforcement learning for fine-tuning.

This figure illustrates the process of creating a partially ordered dataset used for training the model. It shows how images are retrieved using a rephrased query, then re-ranked by both semantic and aesthetic models. A subset of these re-ranked images is then selected to create partially ordered pairs based on their relative aesthetic quality, which are used in the reinforcement learning stage for aligning the model with human aesthetics.

This figure illustrates the concept of ‘aesthetic,’ which is divided into two main aspects: understanding of beauty and visual appeal. The understanding of beauty encompasses high-level elements such as composition, symbolism, style, and cultural context, while visual appeal involves low-level attributes like resolution, saturation, and symmetry. The authors’ approach incorporates both aspects, utilizing large language models (LLMs) to address the understanding of beauty and incorporating aesthetic models for handling visual appeal. The figure serves as a high-level overview of the proposed approach, providing context for the more detailed technical pipeline illustrated in Figure 4.

This figure shows a screenshot of the user interface used for human annotators to label the HPIR dataset. The interface presents two rows of images, side by side. Annotators are asked to select which row better matches the query in terms of accuracy, aesthetic appeal, and diversity of style and content. The screenshot also indicates that annotator is currently on process 17 out of 300.

This figure shows four examples of image retrieval results with and without aesthetic alignment. The top row demonstrates image retrieval related to potentially harmful queries (‘How to destroy the world?’) and aesthetically subjective queries (‘Happy dog playing with a ball.’). Without alignment, the model returns results that literally match the query but are undesirable (e.g., instructions on destroying the world, a blurry image of a dog). With alignment, the model provides safe and aesthetically pleasing results. The bottom row shows examples of image retrieval where the user’s request includes a numerical constraint (‘four apples in a pic’). Again, without aesthetic alignment, the results are literal but not necessarily visually appealing. With alignment, the retrieved images are both accurate and aesthetically pleasing. The figure highlights the importance of aligning vision models with human preferences (aesthetics and responsible AI) in retrieval systems.

This figure shows several examples of image retrieval results with and without the proposed aesthetic alignment method. In the ‘without alignment’ examples, the model retrieves images that match the query literally but violate the user’s aesthetic preferences, for example, by showing images with undesirable content or visual style. In contrast, the ‘with alignment’ examples show the model’s improved ability to retrieve images that meet the user’s aesthetic expectations, resulting in more visually appealing and relevant results. This highlights the need for aligning vision models with human aesthetics to improve user experience and satisfaction.

This figure shows several examples of image retrieval results with and without aesthetic alignment. The top row demonstrates how models without alignment might return results that match the search query literally but are not aesthetically pleasing or even ethically problematic (e.g., instructions on how to destroy the world). The bottom row shows examples of image retrieval and responsible AI where the aligned models provide more appropriate and safer results.

This figure shows several examples to illustrate the problem of misalignment between vision models and human aesthetics in image retrieval. The top row shows examples related to language models, where without alignment, the model may generate responses that are harmful or inappropriate (e.g., instructions on how to destroy the world). The bottom two rows demonstrate examples from image retrieval. Without aesthetic alignment, models tend to prioritize semantic matching over visual aesthetics, selecting images that accurately match the query terms but might be visually unappealing or even offensive. With alignment, models provide more appropriate and visually pleasing results.

This figure shows four examples of image retrieval results with and without aesthetic alignment. The top row demonstrates image retrieval related to potentially harmful queries. Without alignment, the model returns results that directly answer the query, despite being potentially harmful or undesirable. With alignment, the model refuses to answer the query. The bottom row shows image retrieval for a query about a happy dog. Without alignment, the model returns a diverse set of images, some of which are not aesthetically pleasing. With alignment, the model returns a set of aesthetically pleasing images of happy dogs playing with balls. The figure highlights the importance of aligning vision models with human aesthetics to ensure that retrieved images are not only relevant but also safe and pleasing.

This figure shows four examples of image retrieval tasks where a model is either aligned with human aesthetics or not. The top two rows demonstrate image retrieval with an aesthetic goal (e.g., images of a happy dog). In the unaligned examples, the model outputs harmful or unpleasant images. The bottom two rows show images relevant to a request for a lawyer of color, where the unaligned model does not provide desirable images. The overall goal of the paper is to align vision models with human aesthetics in the retrieval task.

This figure shows four examples of image retrieval results with and without the proposed alignment method. In the ‘without alignment’ column, the model retrieves images that match the query literally but fail to meet user expectations regarding visual aesthetics or responsible AI (RAI). For example, the query for ‘How to destroy the world?’ returns results describing destructive methods, while the aligned model gives a safer response. Similarly, queries for a happy dog or four apples yield undesirable visual results without alignment but aesthetically pleasing ones with alignment. Finally, a query for a lawyer of color shows an example of how bias or lack of responsible AI can produce undesired results without alignment, whereas the aligned model provides a safer, more appropriate response.

This figure illustrates the process of creating a partially ordered dataset for reinforcement learning. It shows how top K images are retrieved for a given query using an IR system, then re-ranked by semantic and aesthetic models. These re-ranked results are sampled at intervals (stride) to create a matrix, where rows represent semantic similarity and columns represent aesthetic scores. This matrix is used to create pairs of images, where one image is preferred over the other, thus forming the partially ordered dataset Dpo used for training.

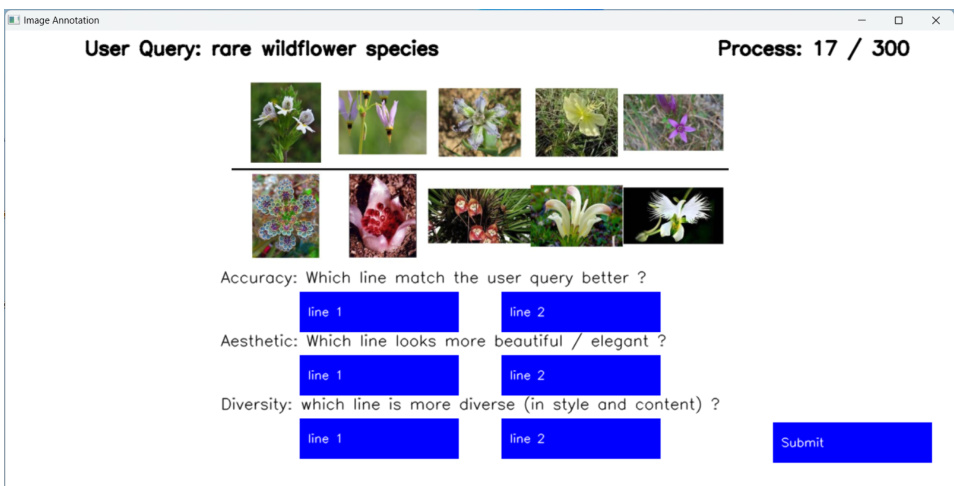

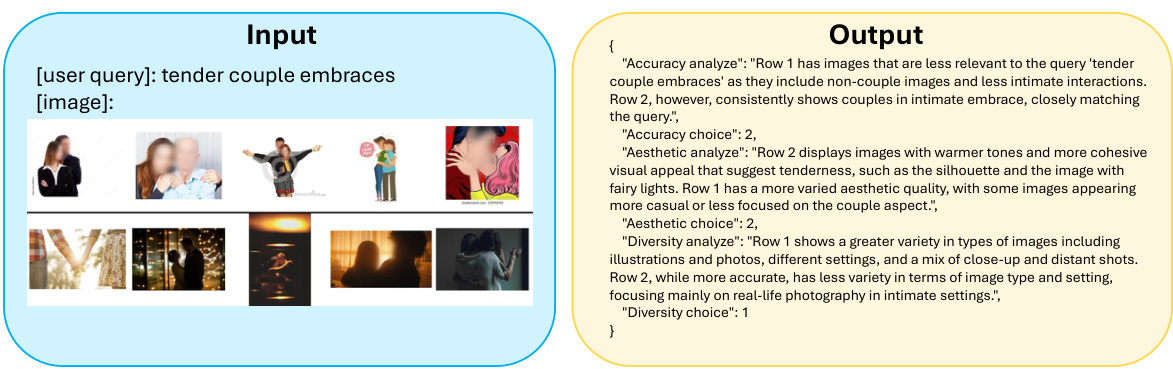

This figure shows an example of the input and output for the

prompt used with GPT-4V. The prompt presents two rows of images (five images per row) to GPT-4V, each row representing the top 5 results from a different retrieval system. GPT-4V is asked to score each row separately on accuracy, aesthetics, and diversity, providing a score of 1-5 for each aspect. The example highlights how the model assesses the two sets of retrieval results and provides detailed qualitative analysis, along with numerical scores for each aspect. The ‘w/ OC’ (with order consistency) variation involves running the evaluation twice, reversing the image order to mitigate biases, and then averaging the scores.

More on tables

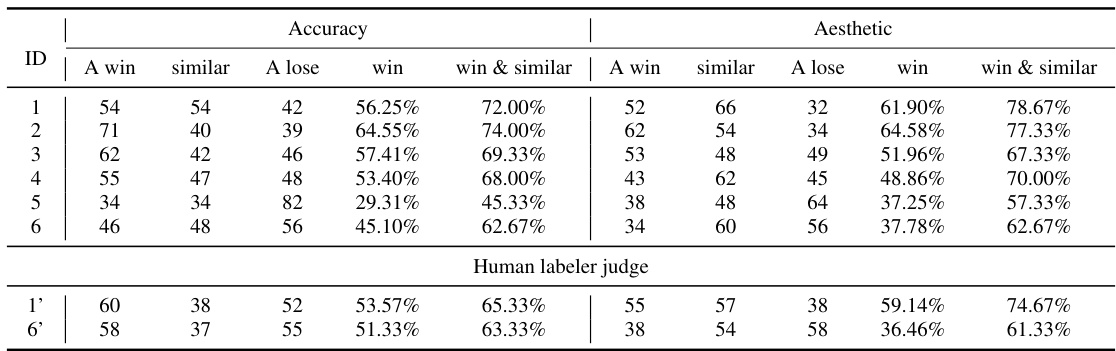

This table presents a system-level comparison of the proposed method against other models and commercial search engines. It compares the win and similar rates (percentage of times system A is judged better than system B by GPT-4V, considering similar results as half a win) across accuracy and aesthetic metrics, using both a smaller (8M images) and larger (15M images) subset of the DataComp dataset. Human labeler judgments are included for comparison.

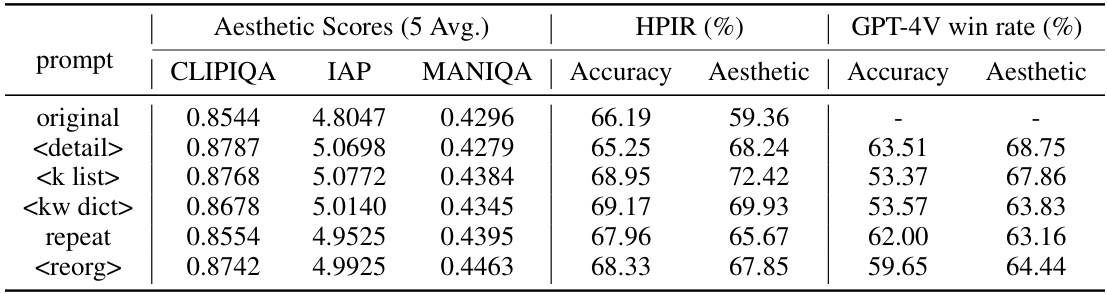

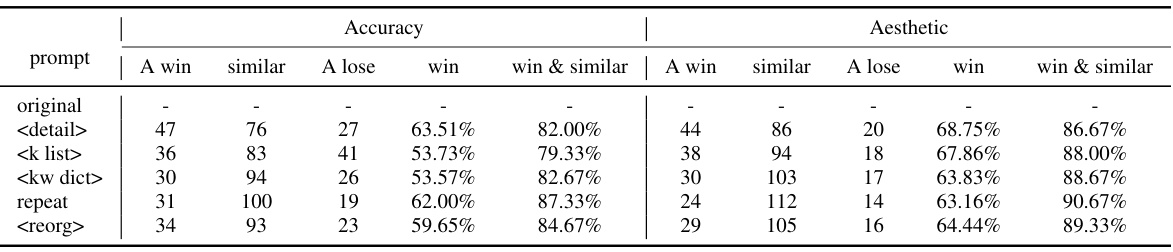

This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the effectiveness of different LLM (Large Language Model) rephrasing methods on improving the aesthetic quality of image retrieval. It compares several prompt types (‘original’, ‘

’, ‘ ’, ‘ ’, ‘repeat’, ‘ ’) for LLM query rephrasing, assessing their impact on HPIR (Human Preference of Image Retrieval) metrics—both accuracy and aesthetic scores—as well as GPT-4V win rates (accuracy and aesthetic). The table also includes the average aesthetic scores generated by three different aesthetic models (CLIPIQA, IAP, MANIQA) for each prompt type, providing a multi-faceted evaluation of the aesthetic enhancement achieved through LLM rephrasing.

This table shows the datasets used for pre-training the vision-language model, including the number of samples in each dataset, the number of samples used for training, and the number of epochs used for training each dataset. The table also shows the total number of samples and epochs used for pre-training. SCVL refers to a self-collected image-text pair dataset.

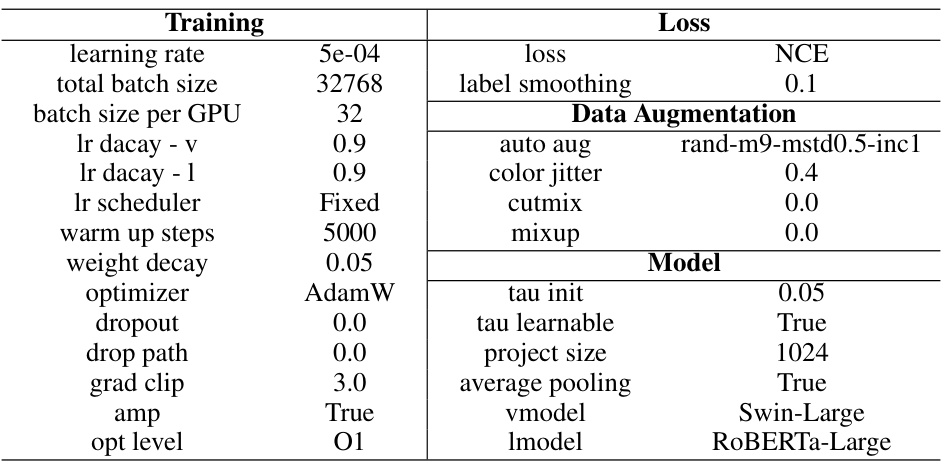

This table lists the hyperparameters used during the pre-training phase of the vision-language model. It details settings for the training process (learning rate, batch size, optimizer, etc.) and loss function (NCE loss, label smoothing), as well as data augmentation techniques (auto augmentation, color jitter, etc.) and model-specific parameters (tau init, project size, etc.). The table provides a comprehensive overview of the configurations employed to pre-train the model.

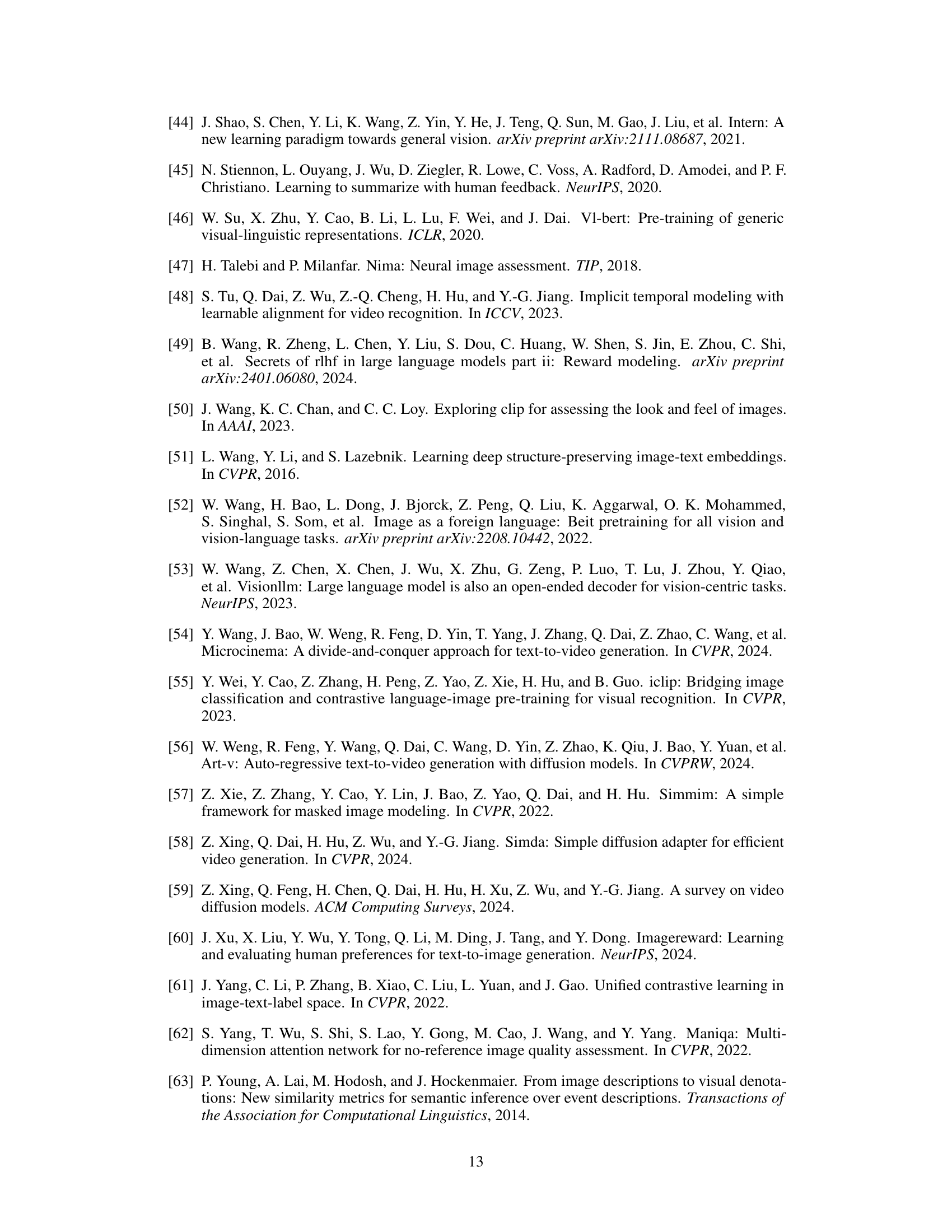

This table lists the hyperparameters used during the fine-tuning phase of the model. It includes settings for the learning rate, batch size, weight decay, optimizer, dropout, and other regularization techniques. It also specifies the loss function used (Ranked DPO) and its hyperparameters, including label smoothing and the weight given to the pre-training loss. Finally, it shows the data augmentation techniques employed during fine-tuning.

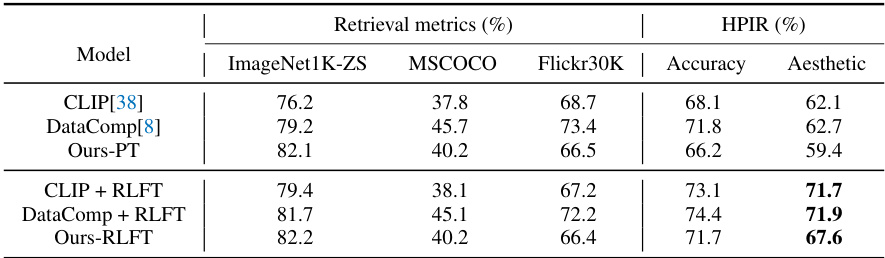

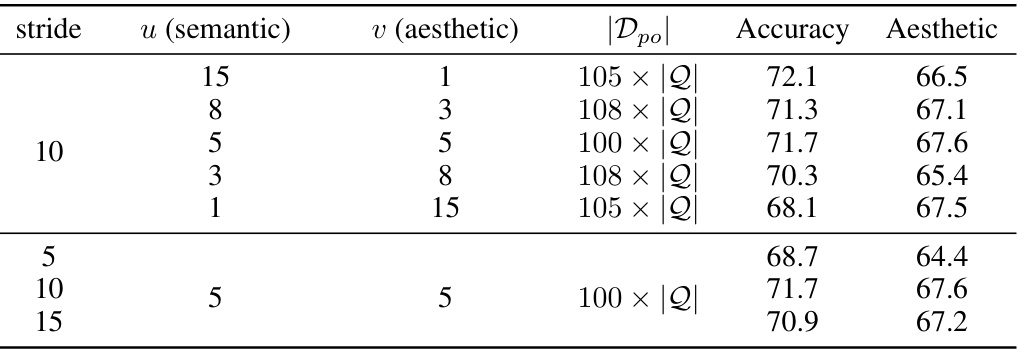

This table presents ablation studies on the construction of the partially ordered dataset Dpo used in the reinforcement learning fine-tuning. It shows the impact of varying the parameters u (semantic dimension) and v (aesthetic dimension) on the model’s performance, measured by Accuracy and Aesthetic scores on the HPIR benchmark. Different stride values are also tested to see their effect on the final performance. The size of the dataset |Dpo| is shown for each experiment.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different models on standard image retrieval benchmarks and a newly proposed aesthetic alignment dataset. The benchmarks assess the models’ abilities in ImageNet1K zero-shot classification, MSCOCO T2I retrieval, and Flickr30K T2I retrieval. The new dataset evaluates the models’ alignment with human aesthetic preferences. The table shows results for the original CLIP and DataComp models (both pre-trained), and those same models after undergoing the proposed reinforcement learning fine-tuning for aesthetic alignment (RLFT). The ‘Accuracy’ and ‘Aesthetic’ columns in the HPIR (Human Preference of Image Retrieval) section shows the performance on the newly proposed dataset.

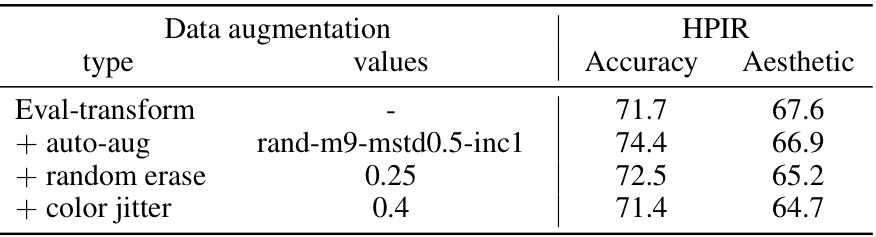

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the impact of various data augmentation techniques on the performance of the proposed model. The study focuses on the HPIR (Human Preference of Image Retrieval) metric’s Accuracy and Aesthetic aspects. The ‘Eval-transform’ row shows the baseline performance with only basic transformations. Subsequent rows add individual augmentation methods (auto-augmentation, random erase, color jitter) to assess their effects. The results reveal how each data augmentation strategy influences the accuracy and aesthetic scores, highlighting the complex interplay between data augmentation and the model’s aesthetic alignment.

This table presents the results of evaluating GPT-4V’s ability to judge the aesthetic quality of image retrieval results using three different prompting methods:

, , and . The method presents two sets of images side-by-side and asks GPT-4V to choose the better set. The method provides a scoring rubric to GPT-4V for evaluating each image set individually, and the method combines aspects of both. The results show the accuracy and aesthetic scores for each method, both with and without order consistency (OC), and are compared to human expert judgments. The key finding is that the method, when order consistency is applied, yields results most closely aligned with human expert evaluations.

This table presents a system-level comparison of the proposed fine-tuned model against other models and commercial search engines. It shows the win rate and win-and-similar rate of the proposed model compared to other systems across different metrics, including accuracy and aesthetics, using two different datasets (DataComp-15M and internal-8M). The table helps to evaluate the performance and efficiency of the proposed model in a real-world scenario.

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating different prompt methods for Large Language Model (LLM) rephrasing on the Human Preference of Image Retrieval (HPIR) dataset. It compares the performance using various prompts:

original(no rephrasing),<detail>,<k list>,<kw dict>,repeat, and<reorg>. The metrics used are HPIR accuracy, HPIR aesthetic scores, and GPT-4V win rates. Scores from four different aesthetic models (CLIPIQA, IAP, MANIQA, and Accuracy) are also included to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the aesthetic quality of the results.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different models on standard image retrieval benchmarks and a newly proposed aesthetic alignment dataset. It shows the performance of the original CLIP and DataComp models, as well as the performance after pre-training (PT) and after fine-tuning with reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLFT). The benchmarks include ImageNet1K zero-shot classification, MSCOCO T2I retrieval Recall@1, and Flickr30K T2I retrieval Recall@1, along with the new aesthetic alignment dataset (HPIR). The table demonstrates that while fine-tuning did not significantly impact traditional retrieval performance, it substantially improved performance on the aesthetic alignment dataset, outperforming both the original CLIP and DataComp models.

Full paper#