↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are computationally expensive to train, mainly due to the computationally intensive feedforward networks (FFNs). This paper addresses this by exploring efficient low-rank and block-diagonal matrix parameterizations for FFNs, aiming to reduce parameters and FLOPs. Previous works often explored these approximations with pre-trained models and focused on specific tasks. This research investigates training LLMs with structured FFNs from scratch, scaling up to 1.3B parameters.

The study introduces a novel training technique called “self-guided training” to overcome the poor training dynamics associated with structured matrices, and compares the performance of these structured models to traditional dense models trained at an optimal scaling trade-off. Results indicate that structured networks can lead to significant computational gains and maintain comparable or superior performance, especially regarding training FLOPs utilization and throughput. These improvements hold across different model sizes and even in the overtraining regime. The proposed method showcases the benefits of these parameterizations, especially when combined with the self-guided training approach.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on efficient large language models (LLMs). It tackles the critical issue of computational cost in LLMs by proposing novel training regimes and structured linear parameterizations for feedforward networks, which significantly impact training efficiency. The findings offer potential for faster and more cost-effective LLM training, especially relevant considering the current trend toward ever-larger models. The work also paves the way for future research on further optimizing LLM architectures and training methods, which may lead to the development of more accessible and powerful LLMs.

Visual Insights#

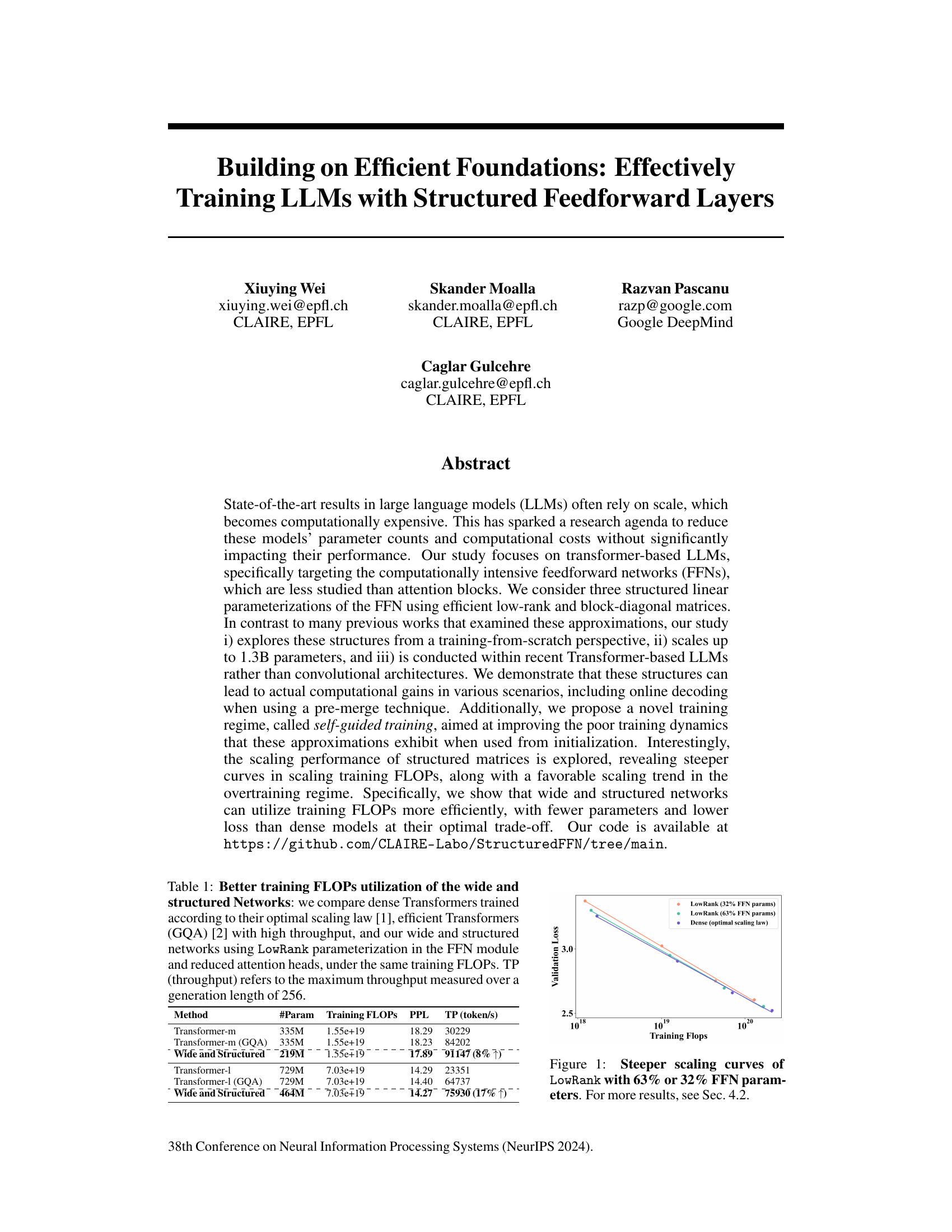

This figure shows the scaling curves for validation loss against training FLOPs for LowRank models with 32% and 63% of the feedforward network (FFN) parameters, compared to a dense model trained with the optimal scaling law. The steeper curves for LowRank indicate that it uses training FLOPs more efficiently than the dense model, achieving a lower validation loss with fewer parameters at the optimal trade-off point. Section 4.2 provides further details and results.

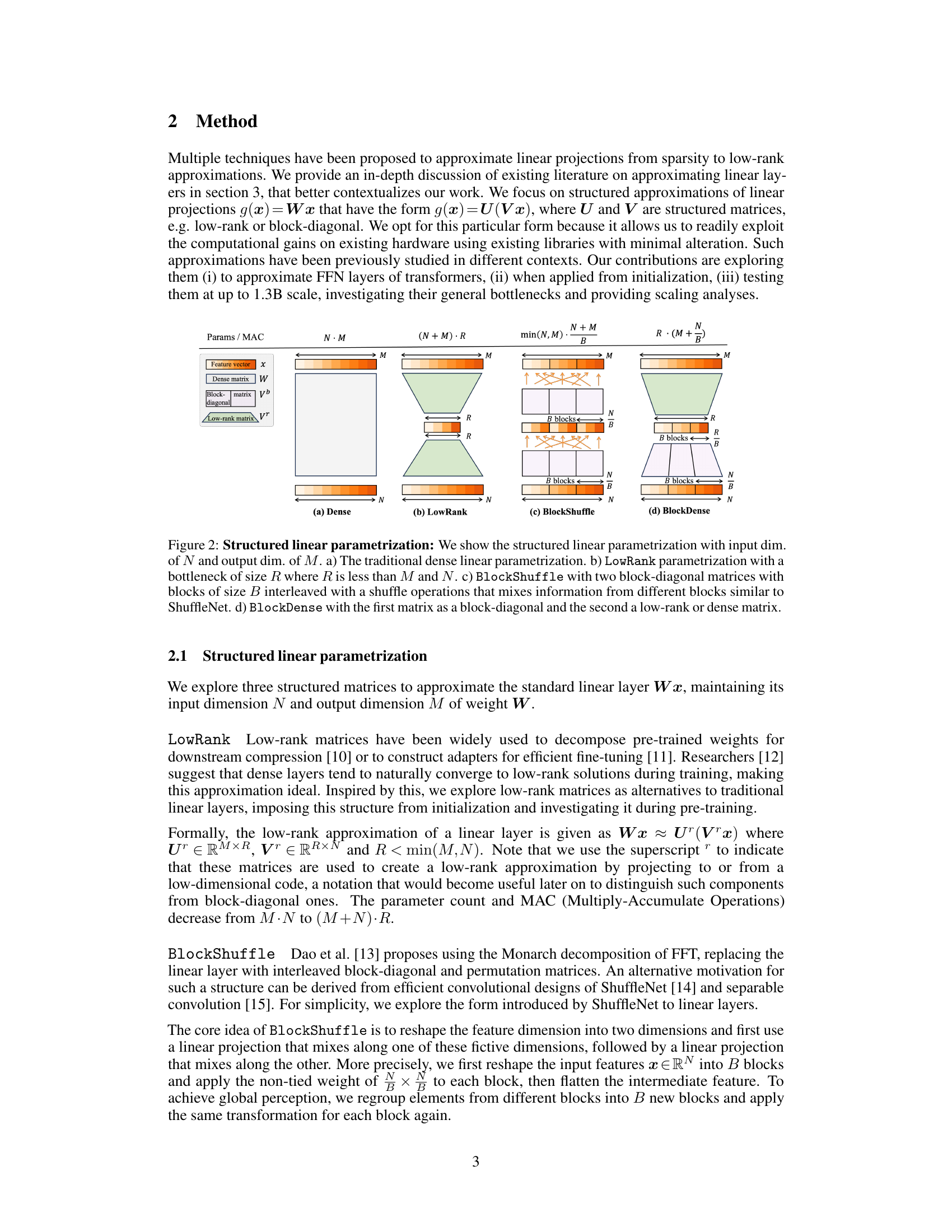

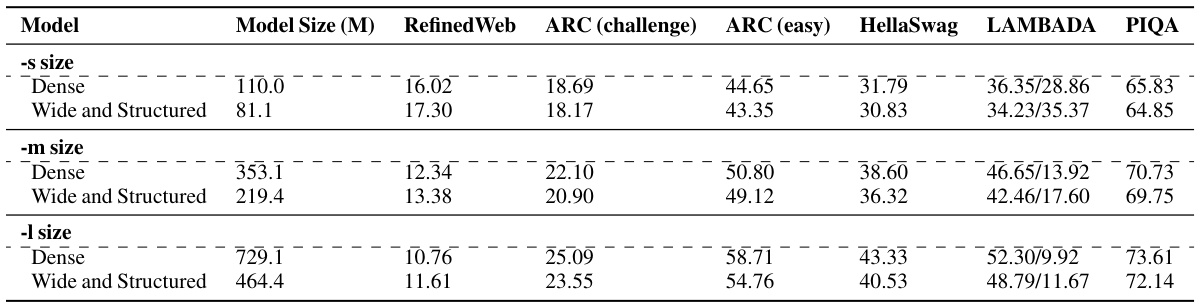

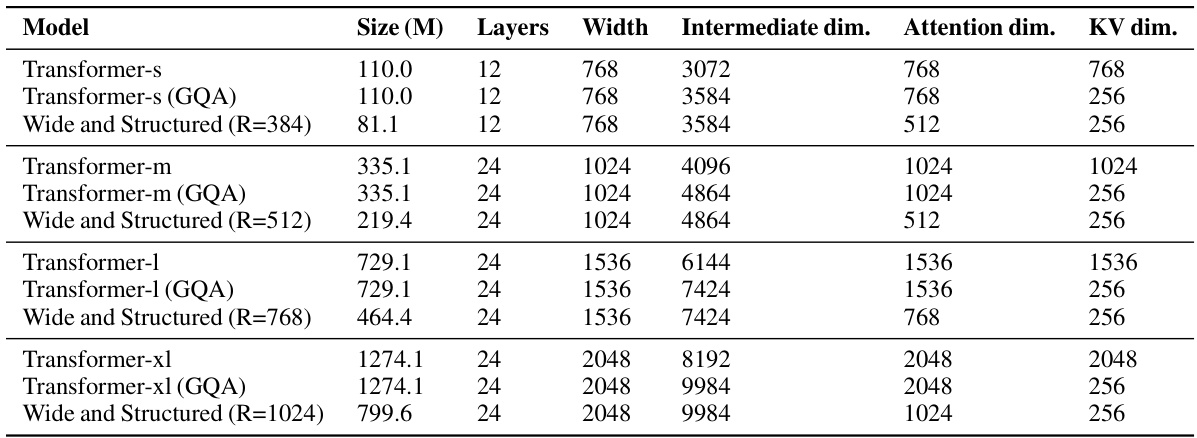

This table compares the training FLOPs utilization of different transformer models. It contrasts dense Transformers, efficient Transformers (using GQA), and wide & structured networks (using LowRank parameterization in the FFN module and reduced attention heads). The comparison is made under the constraint of equal training FLOPs to highlight the efficiency gains of the proposed wide and structured networks. Throughput (TP), representing the maximum tokens generated per second, is also presented.

In-depth insights#

Structured FFNs#

This research explores the use of structured matrices to create more efficient feedforward networks (FFNs) within large language models (LLMs). Three main types of structured matrices are investigated: LowRank, BlockShuffle, and BlockDense. Each offers a unique approach to reducing the computational cost and parameter count of FFNs, which typically constitute a significant portion of LLM training and inference costs. The study contrasts these structured FFNs against traditional dense FFNs, highlighting the trade-offs between efficiency and performance. A novel training regime, ‘self-guided training’, is introduced to address the challenges of training structured FFNs from scratch, overcoming issues such as loss spikes and slow convergence often observed in these models. The results demonstrate that these structured FFNs can achieve computational gains while maintaining competitive performance, especially when scaled to larger models. The findings suggest that wide and structured networks, combining improvements in both attention and FFN modules, offer the most favorable performance versus parameter/FLOP trade-offs. This work provides valuable insights for building more efficient and cost-effective LLMs.

Self-Guided Training#

The proposed ‘Self-Guided Training’ method ingeniously addresses the optimization challenges inherent in training neural networks with structured matrices. It leverages a dense matrix as a temporary guide during the initial training phase, gradually transitioning to the structured representation. This approach mitigates the issues of poor training dynamics, such as loss spikes and slow convergence, often observed when using structured matrices from initialization. By acting as a stabilizing residual component, the dense matrix steers the training away from suboptimal starting points and facilitates the learning of feature specialization within the structured parameters. The method’s flexibility and speed are highlighted; it can be easily integrated into various stages of training and incorporates a stochastic variation to reduce computational overhead. Ultimately, self-guided training demonstrably improves both training dynamics and final model performance with structured matrices, making them more viable for practical large-scale language model applications.

Efficiency Gains#

The research paper explores efficiency gains in training large language models (LLMs) by employing structured feedforward networks (FFNs). Structured FFNs, utilizing low-rank and block-diagonal matrices, reduce computational costs without significantly compromising performance. The study demonstrates that these structures lead to steeper scaling curves when considering training FLOPs. This implies that wide and structured networks achieve better performance with fewer parameters than dense models at their optimal trade-off. Furthermore, the paper introduces a novel training regime called self-guided training to address the optimization challenges associated with structured matrices, resulting in improved training dynamics and ultimately better model performance. Pre-merge techniques are also employed to maintain efficiency during online decoding where computational resources might be limited. The findings highlight the potential of structured matrices for creating computationally efficient and high-performing LLMs, particularly when combined with techniques like self-guided training.

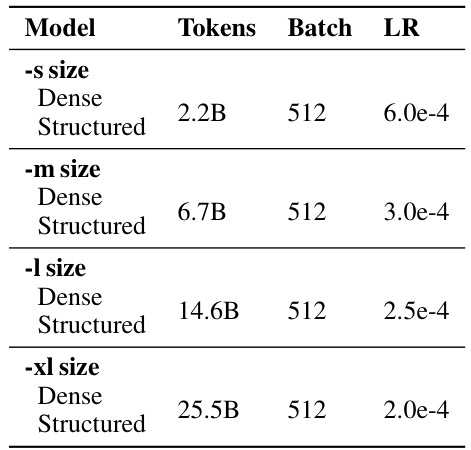

Scaling Behavior#

The scaling behavior analysis in this research is crucial for assessing the practical applicability of structured feedforward networks (FFNs) in large language models (LLMs). The authors meticulously examine scaling performance from two perspectives: training compute scaling and model size scaling. The training compute scaling analysis reveals that structured FFNs exhibit steeper loss curves than traditional transformers, implying greater efficiency in FLOP utilization. This is particularly important at larger model sizes and training FLOP budgets. The model size scaling analysis, conducted in the overtraining regime, further confirms the superiority of structured models, demonstrating favorable scaling trends in terms of both perplexity and downstream task performance. These results strongly suggest that the efficiency gains offered by structured FFNs are not merely artifacts of a specific training regime, but rather reflect a fundamental advantage in how these models leverage computational resources as they grow in scale. Ultimately, these findings have important implications for the design and deployment of computationally efficient LLMs, offering a viable path to achieving state-of-the-art results with reduced computational costs.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the exploration of structured matrices to other LLM components beyond FFNs, such as attention mechanisms, could yield further efficiency gains. Investigating alternative structured matrix types not considered in this study, or novel combinations of existing types, might unlock superior performance. A deeper dive into the optimization challenges associated with structured matrices is warranted, potentially leading to the development of more effective training techniques than self-guided training. Scaling experiments to even larger LLMs, potentially exceeding 100B parameters, would solidify the findings and assess the practical limitations of these methods at extreme scale. Finally, applying these techniques to diverse downstream tasks beyond language modeling could reveal further insights into their generalizability and effectiveness in different application domains.

More visual insights#

More on figures

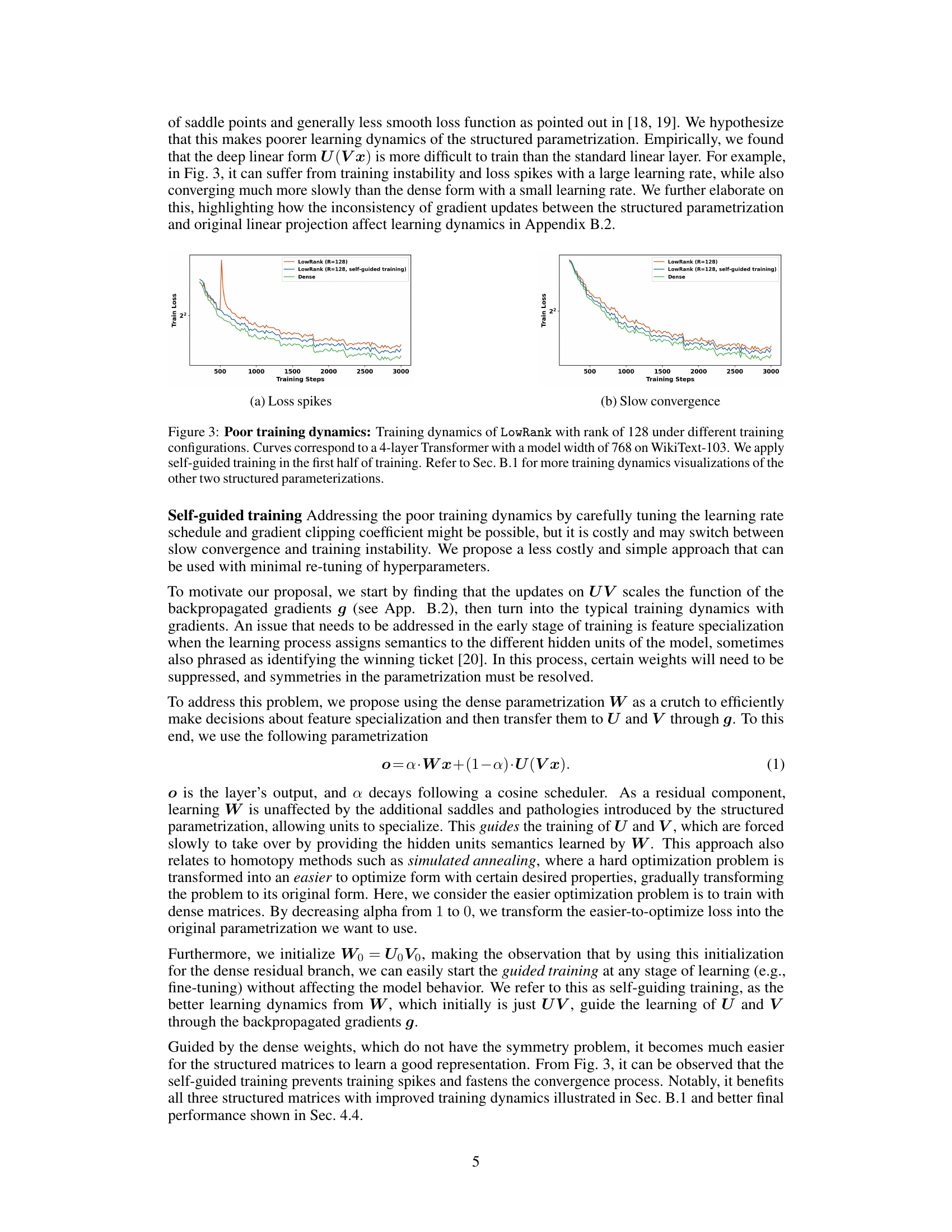

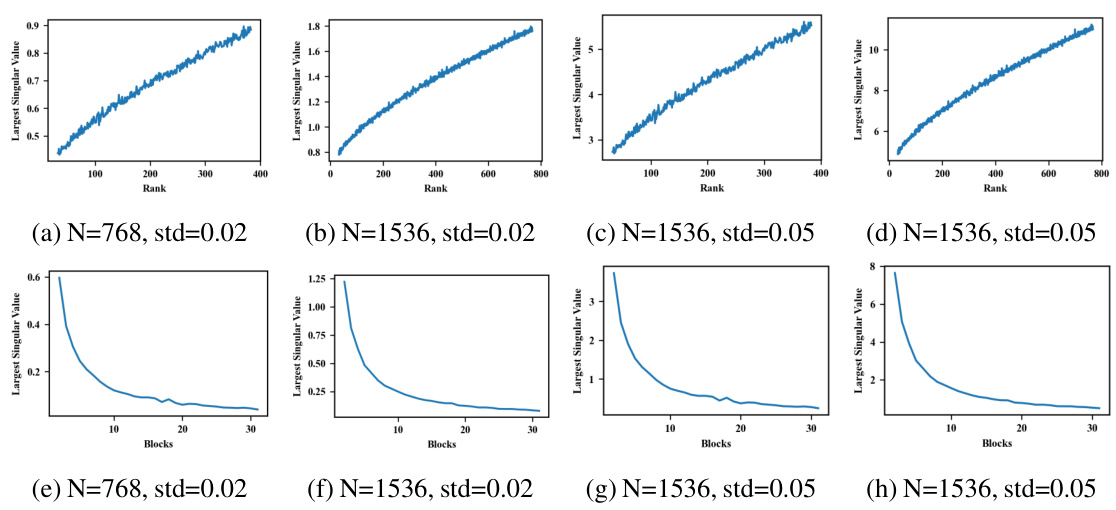

This figure illustrates four different linear parametrizations: dense, LowRank, BlockShuffle, and BlockDense. Each is visually represented to show the transformation of an input feature vector of size N to an output feature vector of size M. The diagrams highlight the differences in matrix structure and computational complexity, showing how LowRank and BlockDense use fewer parameters by employing low-rank and block-diagonal matrices, respectively, while BlockShuffle uses a combination of block-diagonal matrices and shuffle operations.

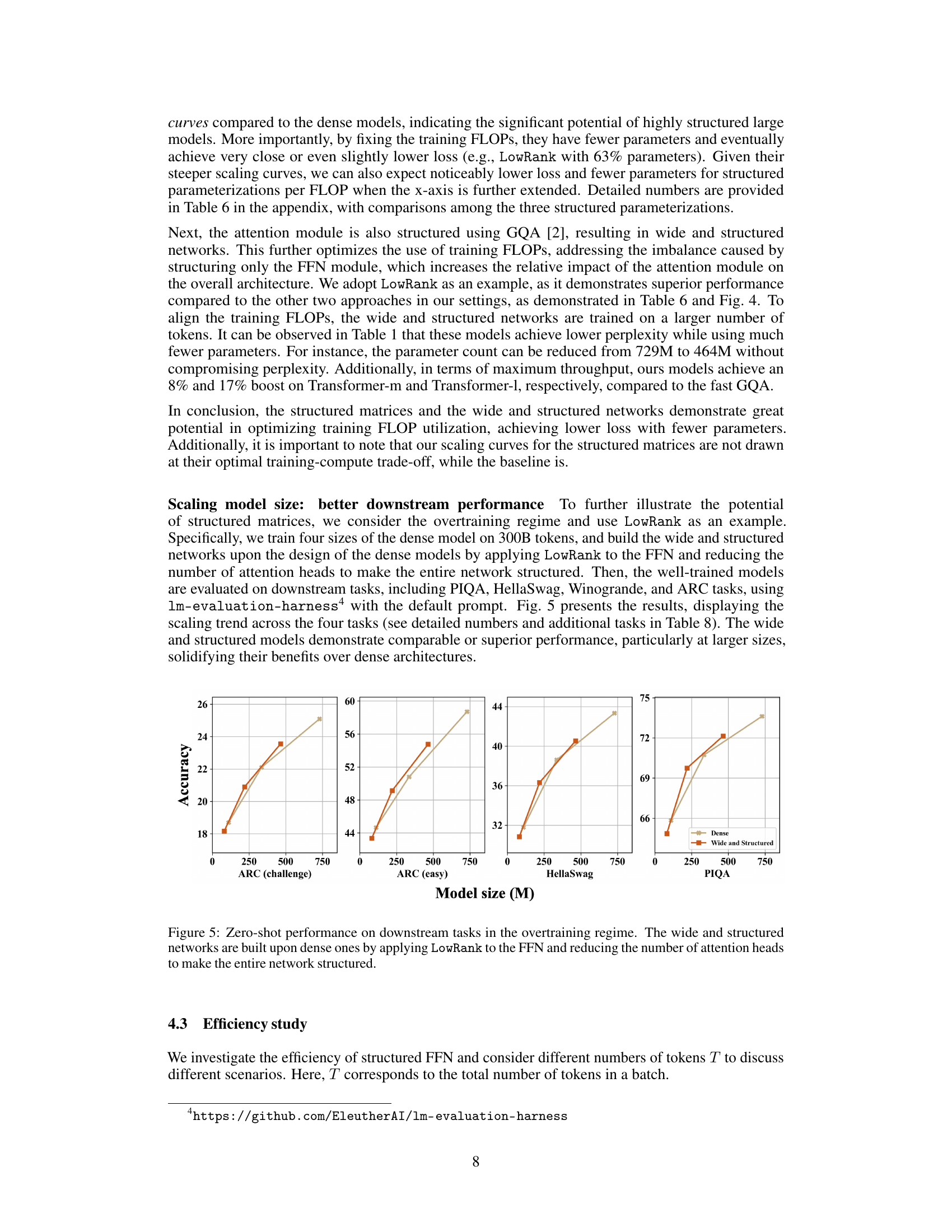

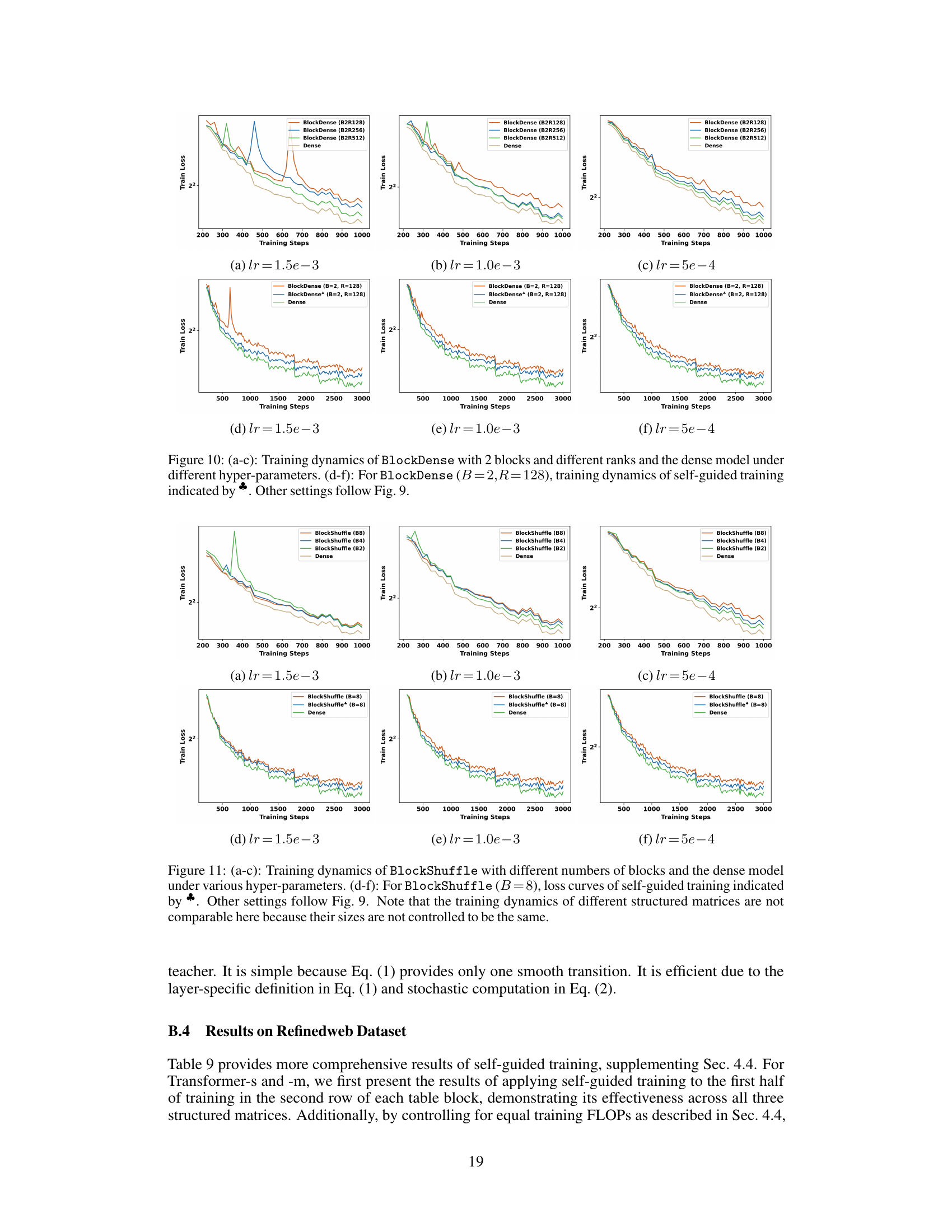

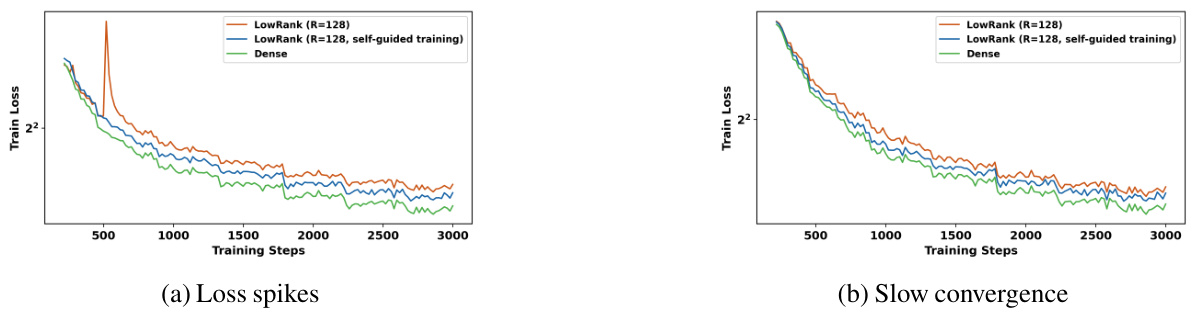

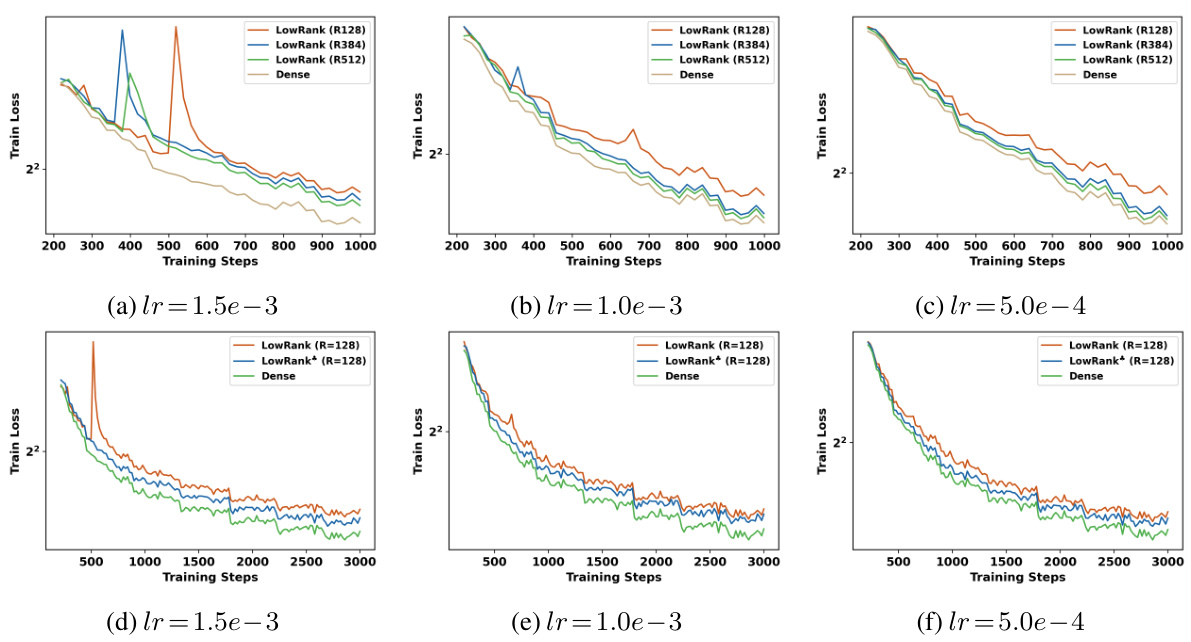

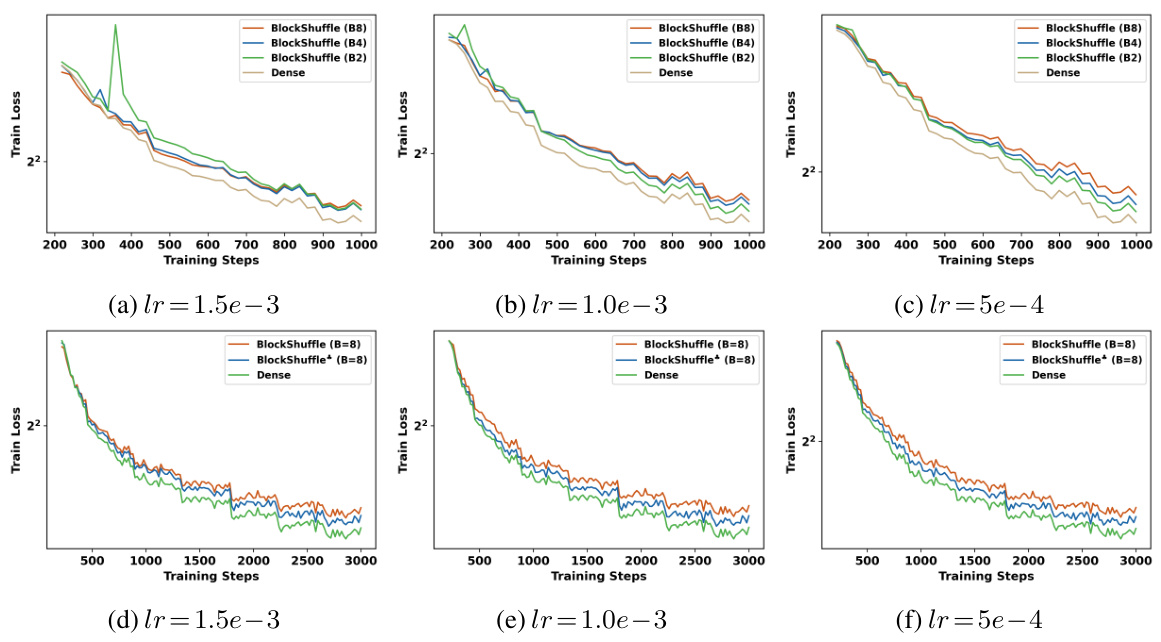

The figure shows the training loss curves for LowRank matrices with and without self-guided training, compared to a dense model. It highlights the issues of loss spikes and slow convergence that occur when using structured matrices without self-guided training, which is then addressed through the proposed training technique.

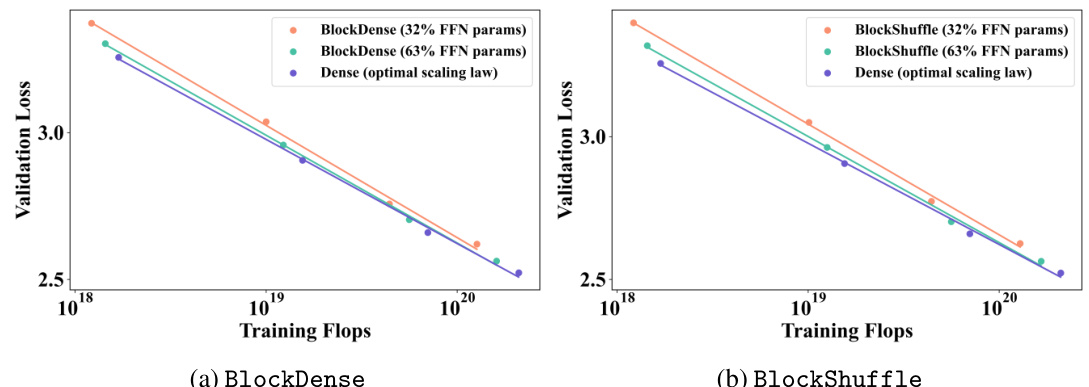

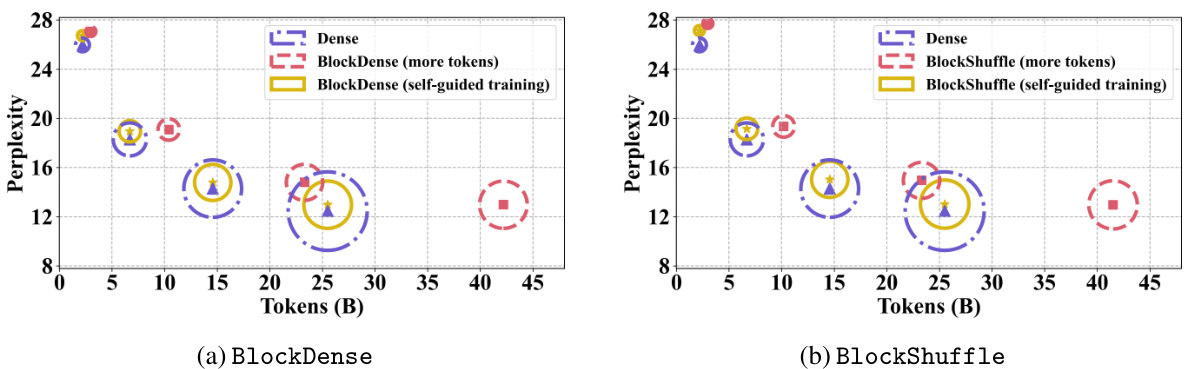

This figure shows the scaling curves for BlockDense and BlockShuffle with 32% and 63% of the original FFN parameters compared to a dense model trained at its optimal trade-off. The curves illustrate that structured matrices exhibit steeper scaling behavior, achieving lower validation loss with fewer parameters at higher training FLOPs.

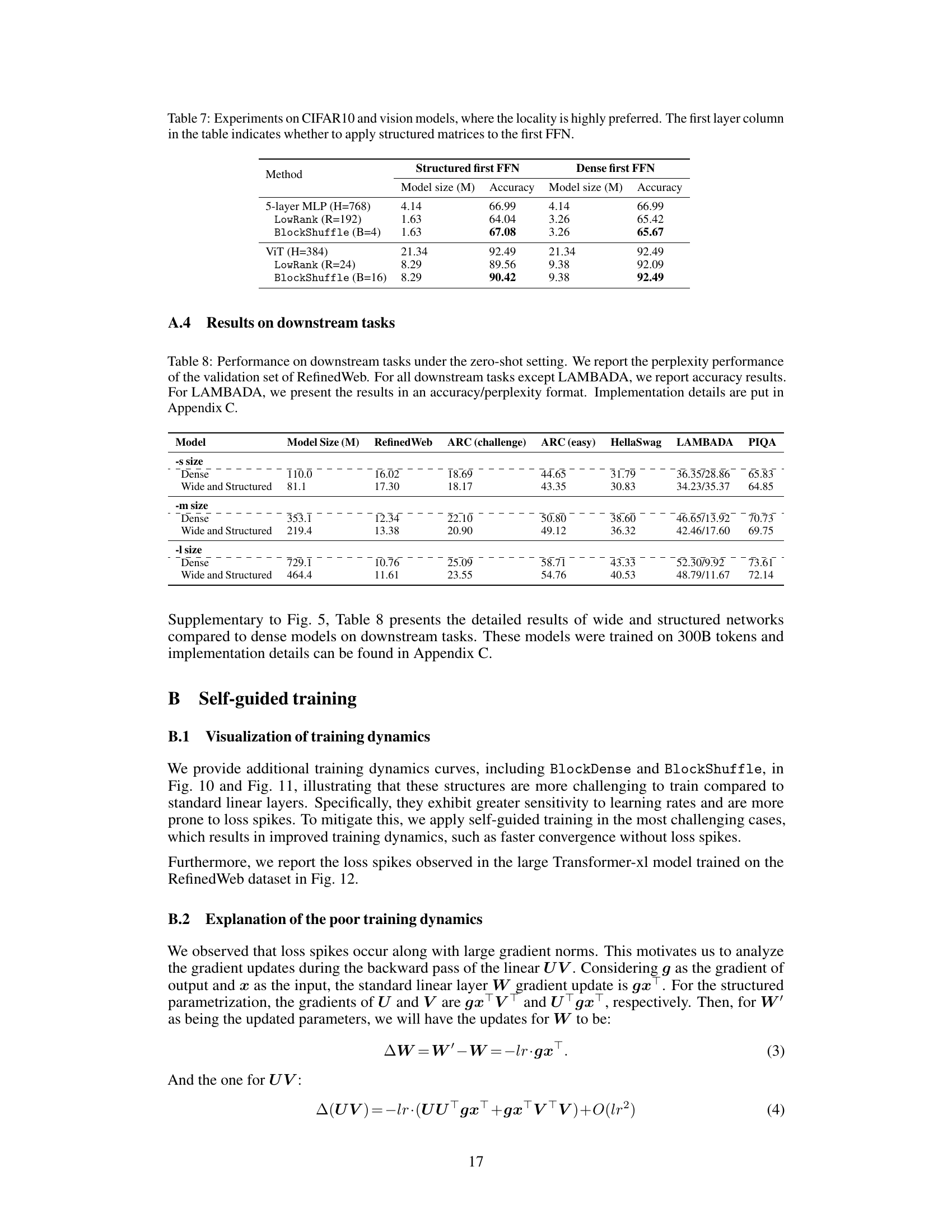

This figure displays the zero-shot performance of various model architectures (Dense, Wide and Structured) on four downstream tasks (ARC-challenge, ARC-easy, HellaSwag, PIQA) when trained in the overtraining regime with 300 billion tokens. The Wide and Structured models utilize LowRank parameterization in the feed-forward network (FFN) and reduced attention heads, demonstrating comparable or superior performance to the dense models, particularly at larger sizes. This illustrates the efficiency gains of the structured matrices in the overtraining regime.

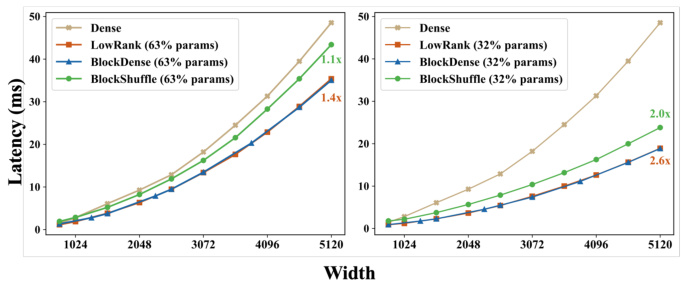

This figure compares the latency of different FFN (feed-forward network) architectures with varying widths. It shows the latency performance of dense FFNs against three different structured FFNs (LowRank, BlockDense, and BlockShuffle) each with 63% and 32% of the parameters of the dense FFN. The results are based on processing 30,000 tokens and the intermediate FFN size is four times the FFN width. The figure demonstrates how the structured FFNs achieve latency improvements compared to the dense FFN across different FFN widths.

This figure shows the decoding latency of dense FFNs and structured FFNs with 32% of the parameters, across various widths and batch sizes. The sequence length is 1, so the batch size equals T (number of tokens). It illustrates how the latency changes as batch size increases for different FFN widths, highlighting the performance improvement achieved by using structured FFNs, particularly with larger widths and batch sizes. It demonstrates how the pre-merge technique helps maintain efficiency even with small batches.

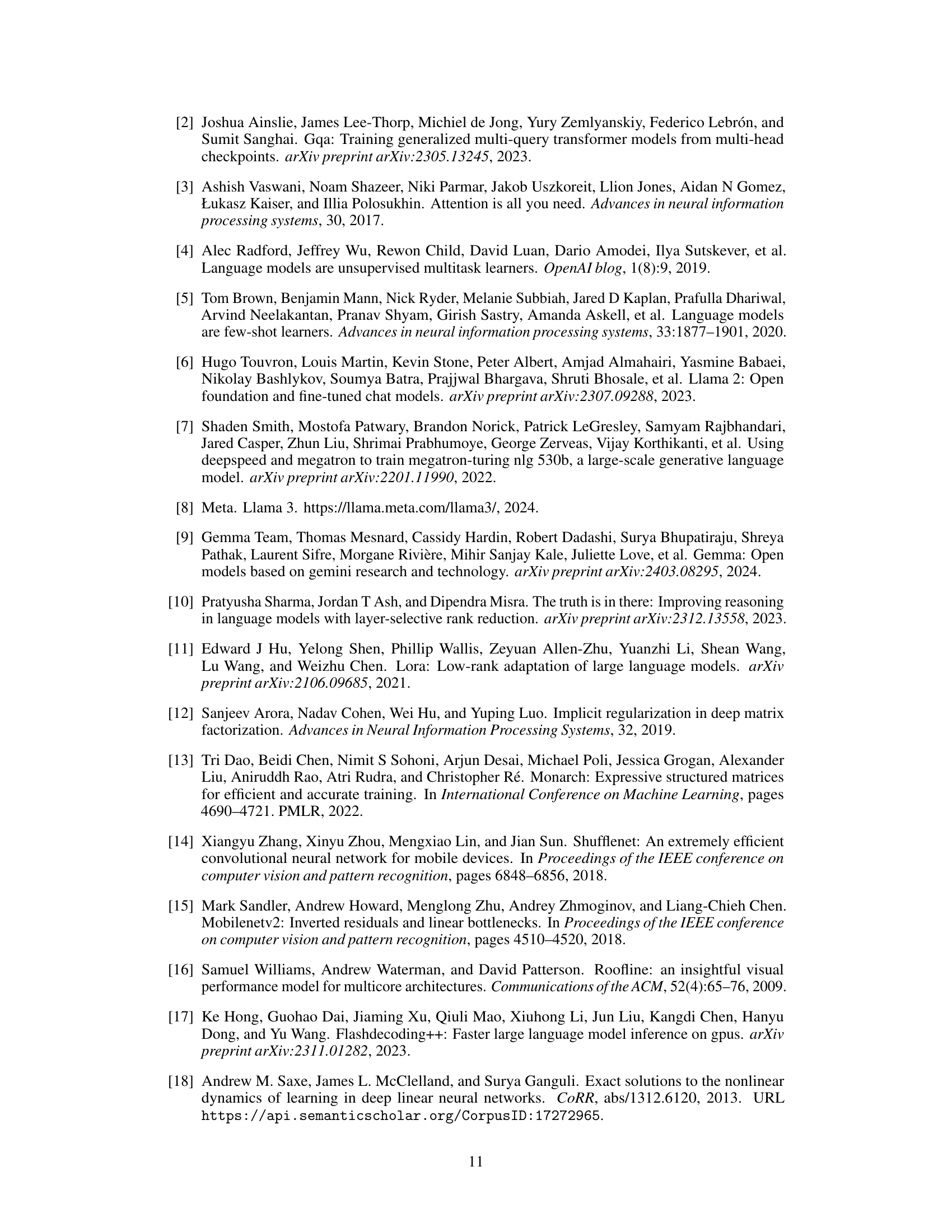

This figure compares the performance of dense and structured feedforward neural networks (FFNs) in large language models (LLMs). The FFNs utilize 32% of the parameters found in the dense models. Two training strategies are compared for the structured FFNs: using more training tokens or employing a self-guided training method. The goal is to achieve comparable training FLOPS (floating point operations per second) across the models. The size of the circles in the plot corresponds to the FLOPs of each model.

This figure shows the training FLOPs (floating point operations) versus validation loss for different models. The steeper curves for LowRank models (with 63% and 32% of the feedforward network parameters) compared to the dense model indicate that LowRank models achieve lower validation loss with fewer training FLOPs, showcasing their improved efficiency. Section 4.2 of the paper provides more detailed results and analysis.

This figure compares the scaling curves of dense and structured feedforward networks (FFNs) in transformer models. The results show that structured FFNs (LowRank and BlockDense with 32% and 63% of the original parameters) exhibit steeper curves and achieve comparable or even lower loss with significantly fewer parameters at the optimal tradeoff than dense FFNs when training FLOPs are controlled. This suggests that structured FFNs scale more efficiently with model size.

This figure compares the scaling curves of training FLOPs for dense and structured FFNs (LowRank and BlockShuffle) with 63% or 32% of the original parameters. The plots show that structured matrices exhibit steeper curves, requiring fewer parameters to achieve a similar validation loss as compared to dense models at the same training FLOP. This indicates greater efficiency in FLOP utilization for the structured models.

This figure displays the scaling curves for BlockDense and BlockShuffle structured matrices compared to a dense model. The models were trained with the same number of tokens, but the structured models used either 63% or 32% of the parameters of the dense model. The plots demonstrate that the structured models exhibit steeper curves, indicating that they achieve similar or better performance with fewer parameters and training FLOPs. The authors highlight that, with the same training FLOPs, these curves suggest even better performance for structured models at larger scales.

This figure compares the scaling curves of dense and structured feedforward networks (FFNs) in transformer models. The results show that structured FFNs, using either 32% or 63% of the parameters of a dense FFN, exhibit steeper scaling curves than the dense FFN baseline. This implies that structured FFNs can achieve comparable or better performance with fewer parameters and lower validation loss, especially when scaled to larger model sizes.

This figure compares the scaling curves of dense and structured feedforward networks (FFNs) in transformer models. The x-axis represents training FLOPs, and the y-axis shows the validation loss. The figure shows that structured FFNs (with 63% or 32% of the parameters of a dense FFN) exhibit steeper curves, achieving lower loss with fewer parameters at various training FLOP levels. This illustrates the potential efficiency gains of using structured FFNs in large language models.

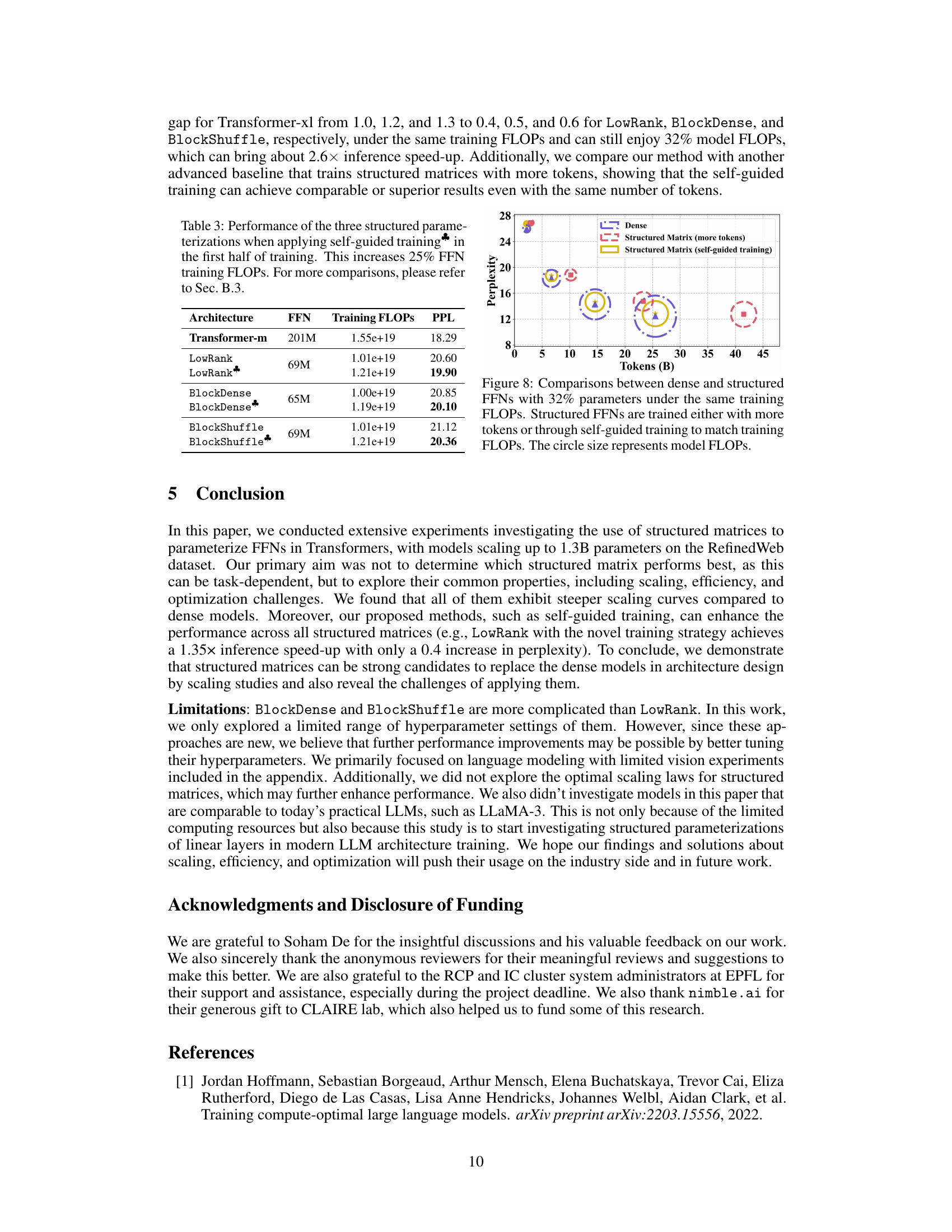

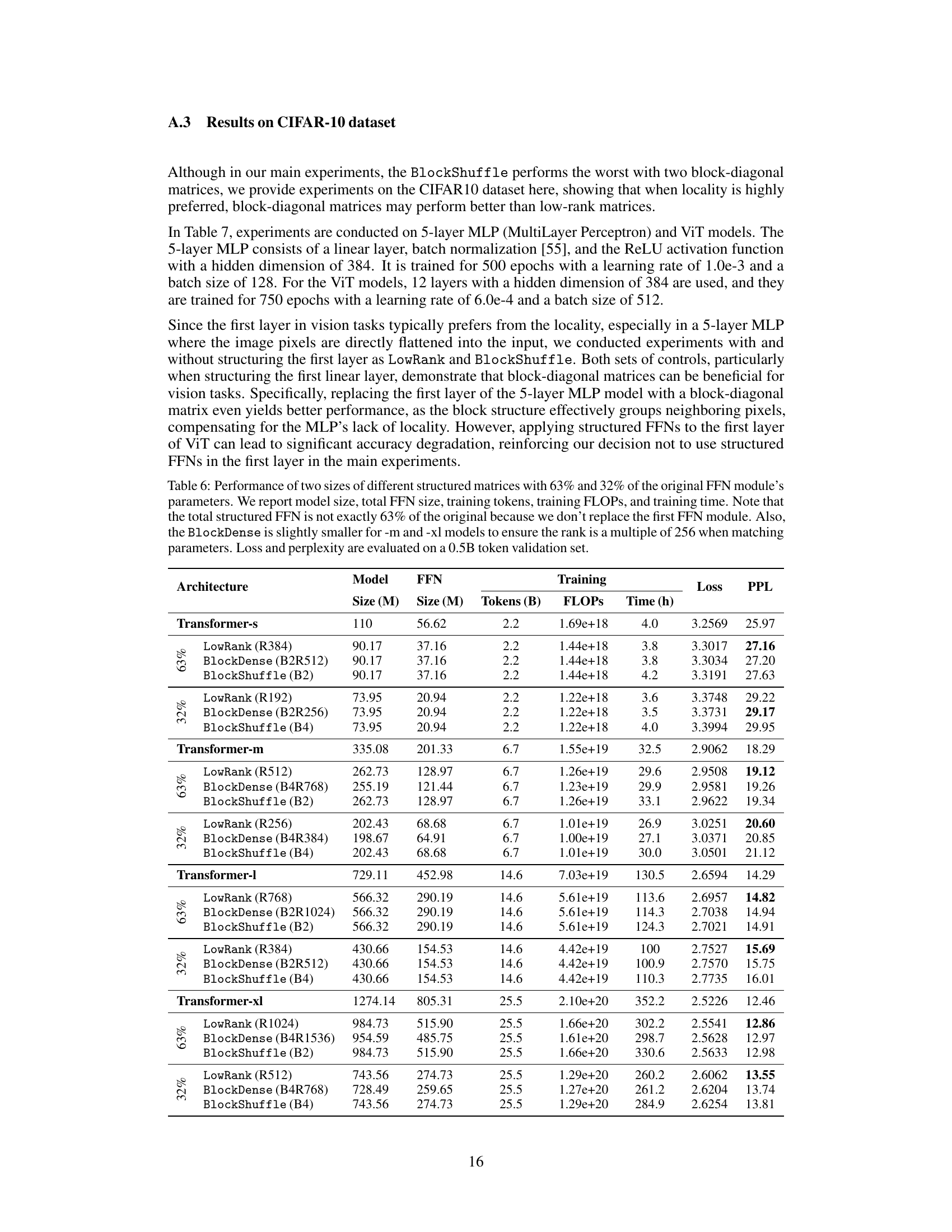

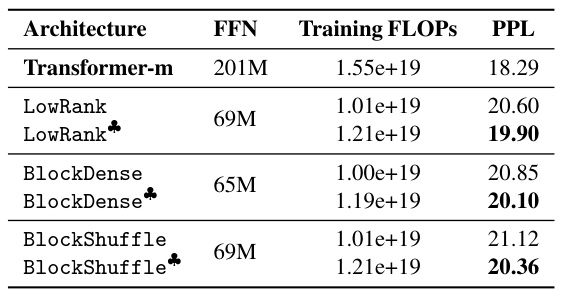

More on tables

This table compares the training time (in hours) and the per-plexity (PPL) achieved by the Transformer-xl model and its variants using structured matrices for the feedforward network (FFN). It presents results for models with 63% and 32% of the original FFN parameters, demonstrating the effect of structured FFNs on training efficiency.

This table compares the training FLOPs utilization of different transformer models. It contrasts dense transformers, efficient transformers (GQA), and wide and structured networks (using LowRank parameterization and reduced attention heads). The comparison is made while maintaining the same training FLOPs across all models. The table includes the number of parameters, perplexity (PPL), and throughput (TP) for each model. Throughput is calculated as tokens per second for a generation length of 256 tokens.

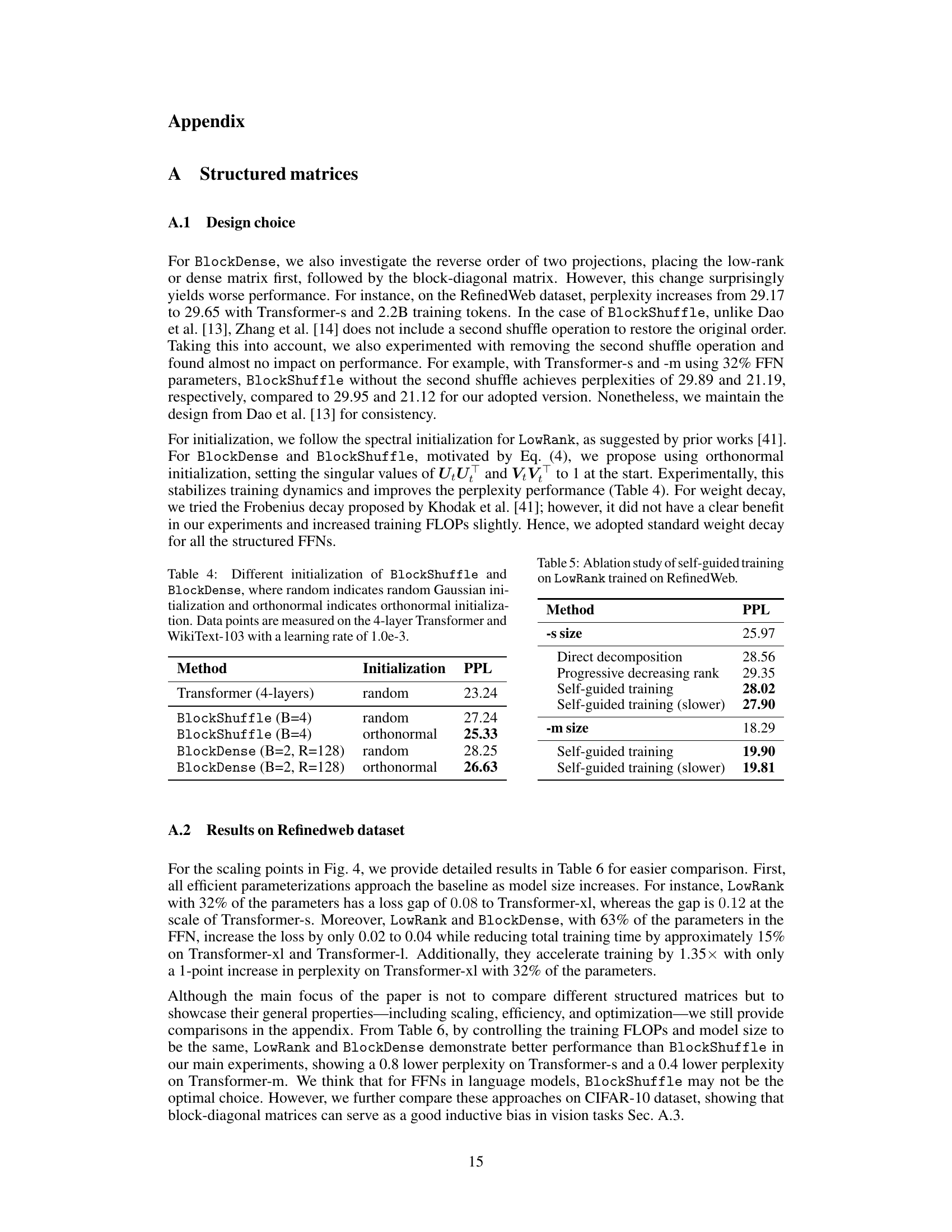

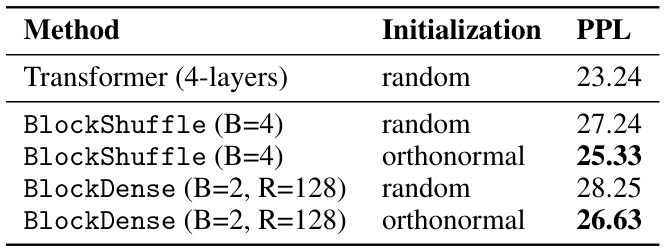

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the initialization methods used for BlockShuffle and BlockDense. It compares the perplexity (PPL) achieved using random Gaussian initialization versus orthonormal initialization for these two structured matrix types in a 4-layer Transformer model trained on the WikiText-103 dataset. The results show that orthonormal initialization leads to lower perplexity scores for both BlockShuffle and BlockDense, indicating that this initialization strategy is beneficial for training these models.

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the effectiveness of self-guided training for LowRank matrices on the RefinedWeb dataset. It compares the perplexity (PPL) achieved by different training methods: direct decomposition, progressive decreasing rank, self-guided training (with a faster and slower annealing schedule). The perplexity scores provide a measure of the language model’s performance on the task, with lower scores indicating better performance.

This table compares the training FLOPs utilization of different transformer models. It contrasts dense transformers, efficient transformers (GQA), and wide/structured networks with low-rank FFN parameterization. The models are trained using the same training FLOPs, and the table shows the number of parameters, perplexity (PPL), and throughput (TP) for each model. It highlights the improved efficiency of wide/structured networks in terms of using fewer parameters and achieving higher throughput while maintaining comparable perplexity.

This table compares the training FLOPs utilization of different Transformer models. It contrasts dense Transformers, efficient Transformers (GQA), and the authors’ wide and structured networks. The comparison is done under the constraint of equal training FLOPs, focusing on model parameters, perplexity (PPL), and throughput (TP). The wide and structured networks use LowRank parameterization in their feedforward networks (FFNs) and have a reduced number of attention heads. The table highlights how the authors’ approach achieves better throughput with fewer parameters while maintaining comparable perplexity.

This table compares the training FLOPs utilization of different transformer models. It shows the trade-off between the number of parameters, perplexity (PPL), and throughput (TP) for dense, efficient (GQA), and wide & structured networks. All models were trained using the same training FLOPs to highlight the efficiency gains from using structured FFN layers with reduced attention heads.

This table compares the training FLOPs utilization of different Transformer models with the same training FLOPs budget. It contrasts standard dense Transformers, efficient Transformers (GQA), and the authors’ proposed wide and structured networks (using LowRank parameterization in the FFN and reduced attention heads). The comparison includes the number of parameters, perplexity (PPL), and throughput (TP). The results demonstrate the superior training FLOPs efficiency of the wide and structured networks.

This table compares the training FLOPs utilization of different Transformer models. It contrasts dense Transformers (trained optimally), efficient GQA Transformers, and the authors’ wide and structured networks. The authors’ models use a LowRank parameterization in the Feedforward Network (FFN) and reduce the number of attention heads. The comparison is performed under the constraint of equal training FLOPs, highlighting the efficiency gains of the proposed approach in terms of parameters and throughput.

This table compares the training FLOPs utilization of different transformer models. It contrasts dense transformers, efficient transformers (GQA), and wide & structured networks with LowRank parameterization in the FFN module and reduced attention heads. The comparison is made under the same training FLOPs, highlighting the efficiency gains of the proposed wide & structured networks in terms of parameters and throughput.

This table compares the training FLOPs utilization of different transformer models with the same training FLOPs budget. It contrasts dense transformers, efficient transformers (GQA), and the authors’ wide and structured networks. The wide and structured models use LowRank parameterization in the feedforward network (FFN) and have reduced attention heads. The table shows that the wide and structured networks achieve better throughput (TP) with fewer parameters and lower perplexity (PPL) compared to the other models.

Full paper#