↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Multi-modal large language models (MLLMs) struggle with processing long text contexts due to high computational costs. Existing methods for extending context length have limitations in efficiency and effectiveness. This paper introduces Visualized In-Context Text Processing (VisInContext), a novel method that efficiently processes long in-context text using visual tokens.

VisInContext converts long text into images and uses visual encoders to extract textual representations. This significantly reduces GPU memory usage and FLOPs, enabling the processing of much longer texts with nearly the same computational cost as processing shorter texts. Experimental results show that models trained with VisInContext achieve superior performance on various downstream benchmarks. The approach is complementary to existing methods and shows great potential for document QA and sequential document retrieval.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents VisInContext, a novel and efficient method to significantly increase the in-context length in multi-modal large language models. This addresses a key challenge in the field by enabling the processing of longer texts with much lower computational costs. The findings have implications for various downstream tasks including document QA and sequential document retrieval, opening new avenues for research in handling long-context multi-modal data.

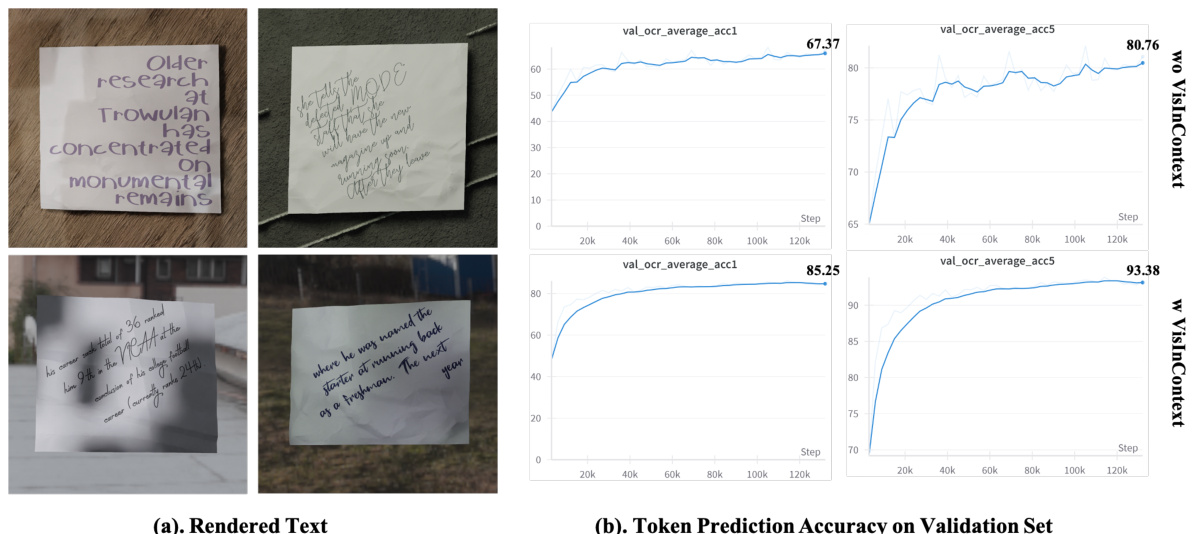

Visual Insights#

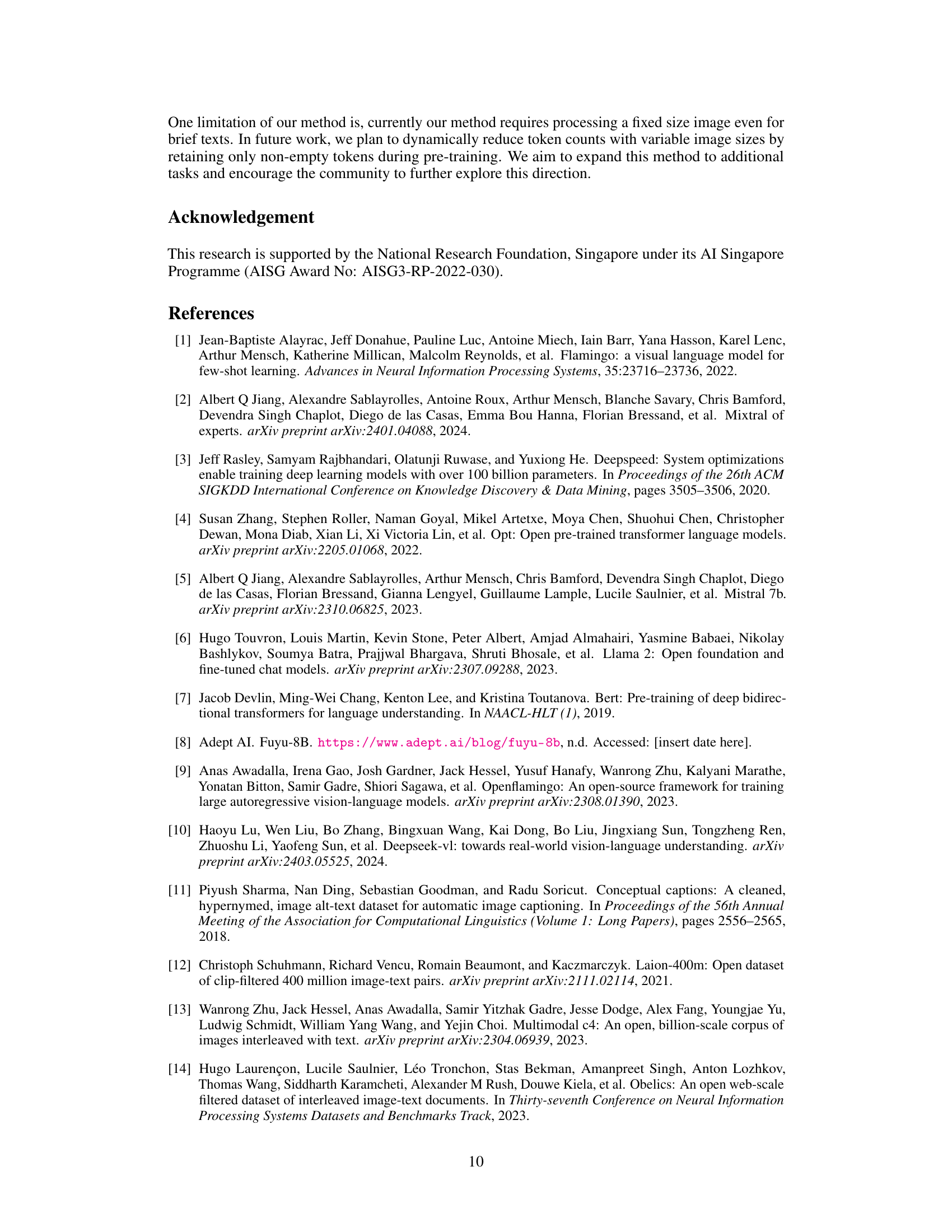

The figure shows two graphs: GPU memory usage vs. in-context text length, and TFlops vs. in-context text length. It compares the performance of the original method with the VisInContext method. VisInContext significantly increases the in-context text length from 256 to 2048 tokens while maintaining a similar level of FLOPs, indicating improved efficiency. The experiments were performed on NVIDIA H100 GPUs using a 56B MOE language model with 4-bit quantization and a batch size of 32 with FP16.

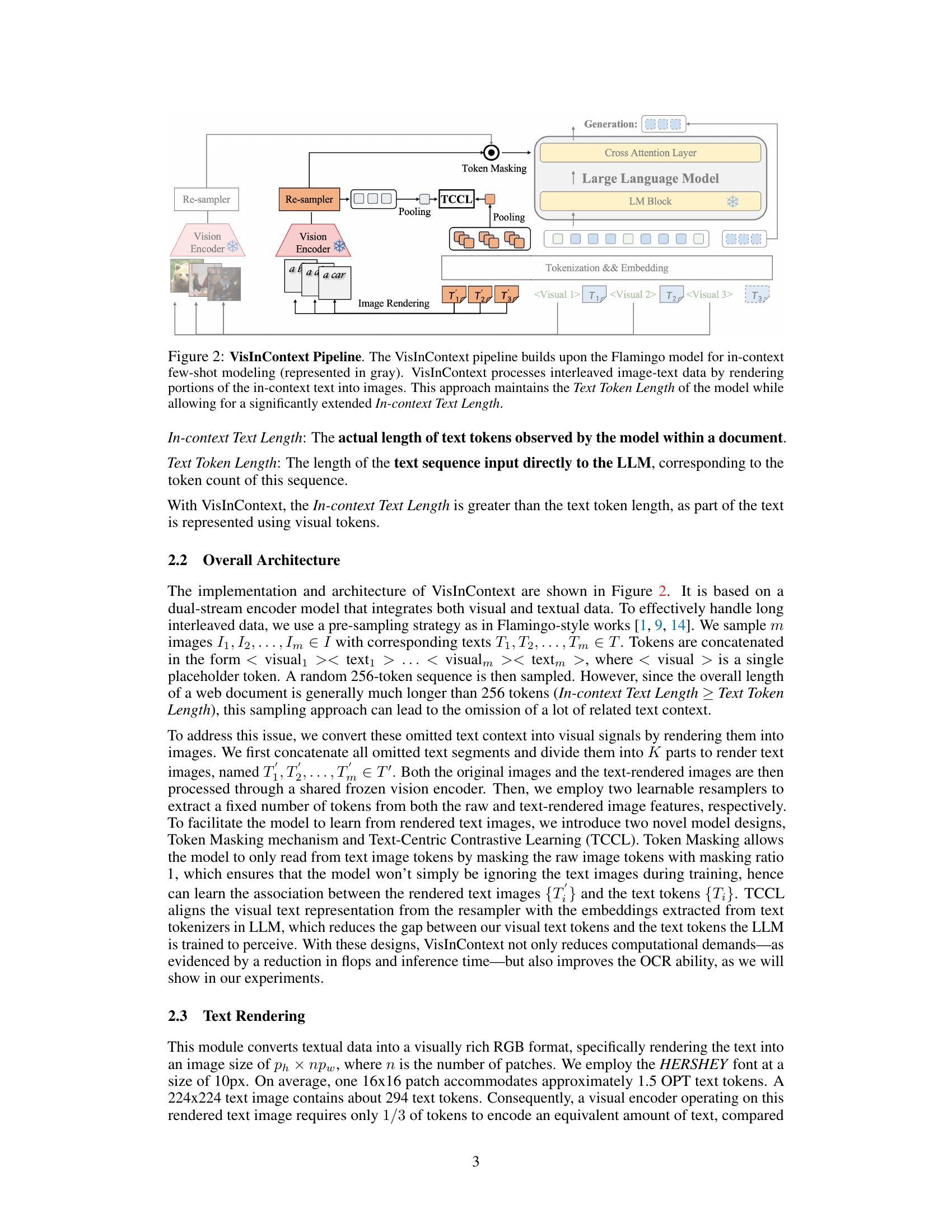

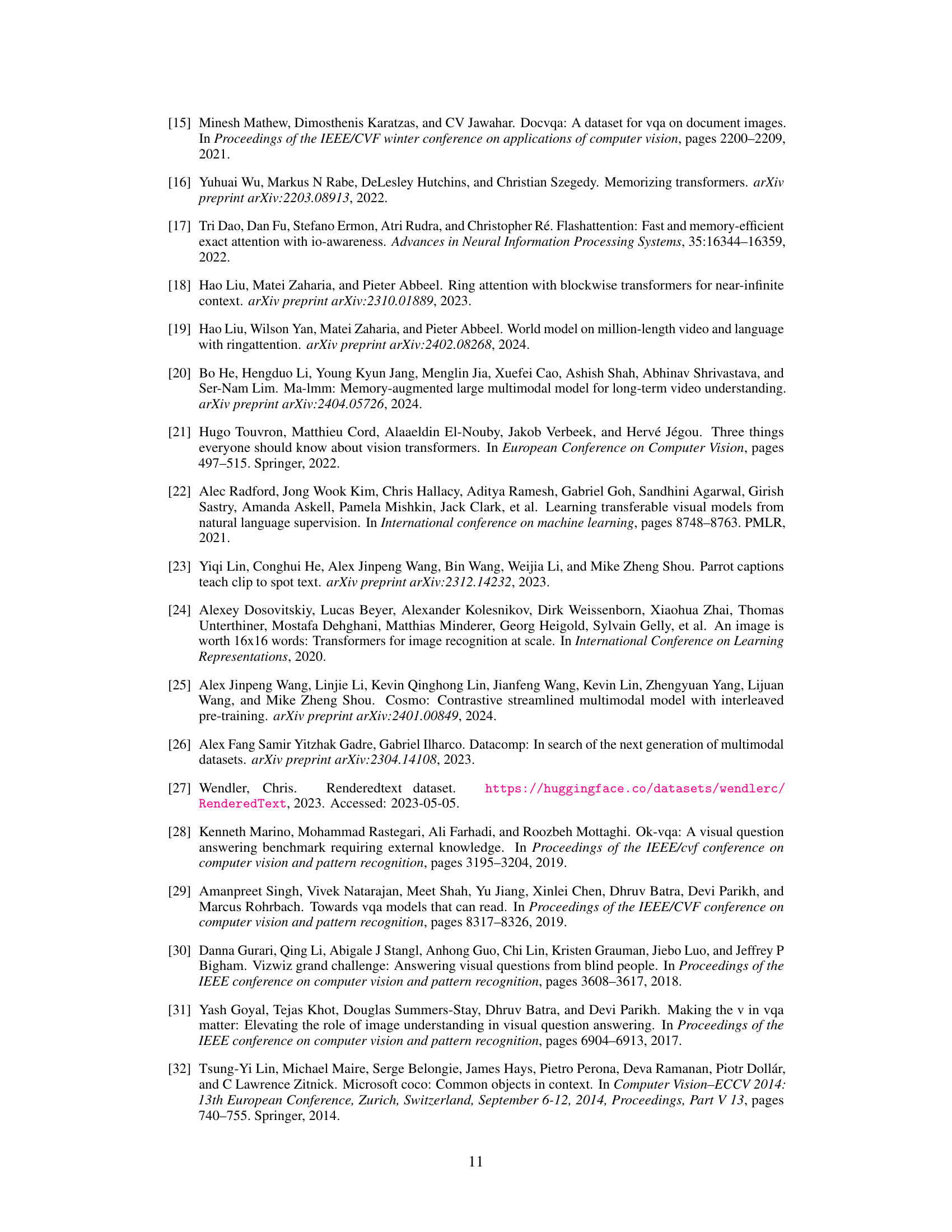

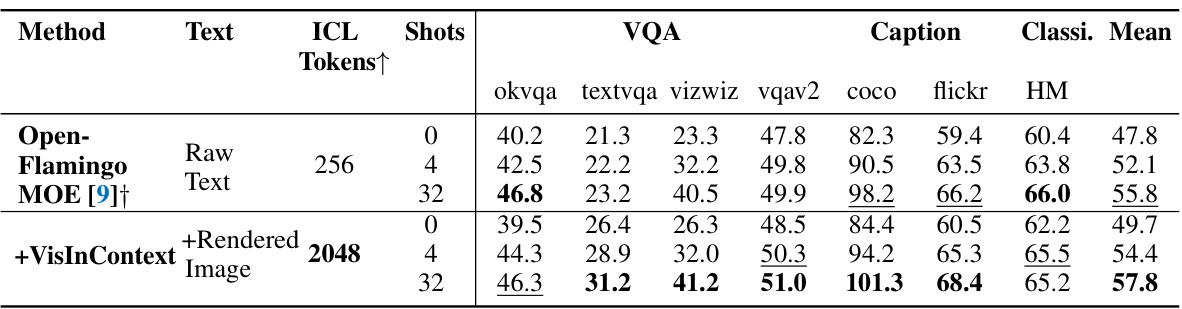

This table presents the results of experiments comparing the performance of a 56B parameter MOE model with and without the VisInContext method on several downstream tasks. The key finding is that increasing the in-context length (ICL) from 256 to 2048 tokens using VisInContext leads to significant improvements in performance across various tasks (VQA, captioning, classification). The table shows improvements, even with a smaller number of shots (few-shot learning setting).

In-depth insights#

Visual ContextBoost#

The hypothetical heading ‘Visual ContextBoost’ suggests a method enhancing the contextual understanding of visual data within a larger system. This could involve several approaches. One possibility is improving the resolution or fidelity of visual input, allowing for more detail to be processed and understood. Another avenue may be incorporating diverse visual data types, such as combining images with videos or incorporating textual descriptions alongside the visual information for richer context. A third potential approach is developing advanced algorithms that can better extract and interpret meaningful relationships and patterns from visual data, essentially boosting the system’s ability to ‘see’ the context more effectively. The success of any Visual ContextBoost method would likely depend on the specific application, requiring careful consideration of the type of visual data, the desired level of contextual understanding, and the computational resources available. A strong Visual ContextBoost strategy would likely involve a synergistic combination of several of these techniques.

Multimodal Efficiency#

Multimodal efficiency in large language models (LLMs) focuses on optimizing the processing of both textual and visual data. Current approaches often face limitations due to the substantial computational resources required. Reducing GPU memory usage is a key aspect, as is minimizing floating point operations (FLOPs) for training and inference. The paper explores the innovative technique of Visualized In-Context Text Processing (VisInContext), which converts long textual content into images, processed efficiently by visual encoders. This significantly reduces memory consumption compared to processing long texts directly within the LLM. The tradeoff involves converting text to images, a potential bottleneck if not carefully optimized. The effectiveness hinges on the efficiency of the visual encoder and the ability of the model to seamlessly integrate visual and textual information. Careful design of text rendering and token masking techniques are crucial to maintain accuracy. The overall impact on downstream tasks is evaluated, assessing the balance between efficiency gains and any potential loss in performance due to the image representation. Further research might explore different image encoding schemes and address potential biases introduced by image-based processing.

Long-Text Encoding#

Long-text encoding in multimodal large language models (MLLMs) presents a significant challenge due to substantial GPU memory and computational costs. Existing methods, such as utilizing memorizing banks or novel self-attention mechanisms, offer partial solutions but often come with trade-offs in efficiency or scalability. Visualized In-Context Text Processing (VisInContext), as presented in the research paper, proposes an innovative approach to efficiently encode extended text contexts. By leveraging the strengths of visual encoders in MLLMs, VisInContext converts long textual content into images, significantly reducing GPU memory usage and FLOPs. This method complements existing techniques, providing a way to increase in-context text length by several times with comparable computational costs. The effectiveness of VisInContext is demonstrated through superior performance on downstream benchmarks for in-context few-shot evaluation and document understanding tasks, showcasing its potential for various document-related applications. However, limitations remain; the approach relies on fixed image sizes, potentially impacting efficiency for variable-length texts and may require further optimization for robust performance across diverse scenarios.

Future Extensions#

The paper’s core contribution is VisInContext, a technique to efficiently process extended text contexts in multimodal large language models (MLLMs) by converting text into images and leveraging visual encoders. A natural extension would be to explore dynamically adjusting the image size based on text length, rather than using a fixed size. This would improve efficiency for shorter text segments. Further research could investigate the application of VisInContext to diverse MLLM architectures beyond Flamingo, evaluating its performance and exploring potential architectural synergies. Another key area is to explore the effect of different image rendering techniques and the choice of visual encoder on the overall performance and computational cost. It is crucial to investigate the robustness of VisInContext across various datasets and downstream tasks, potentially focusing on tasks requiring a deep understanding of complex document structures. Finally, a thorough analysis of the broader societal impacts is necessary, considering potential biases introduced by visual representations of text and mitigating risks associated with efficient text processing for misinformation or malicious applications.

Method Limitations#

A critical analysis of the limitations inherent in the methodology of a research paper would delve into several key aspects. Firstly, it would examine the generalizability of the methods employed. Do the findings extrapolate to various datasets, contexts, or model architectures? Scalability is another critical point: are the methods computationally feasible for larger datasets or more complex models? Reproducibility is paramount; the paper should clearly articulate steps and parameters to ensure independent researchers can successfully replicate the results. Furthermore, the analysis should consider any potential biases present in the methodology, such as selection bias or algorithmic bias, which could skew the results. Finally, the limitations should acknowledge any unaddressed confounding factors that might affect the validity and interpretation of the results. A thorough exploration of these factors offers valuable insights into the reliability and scope of the research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

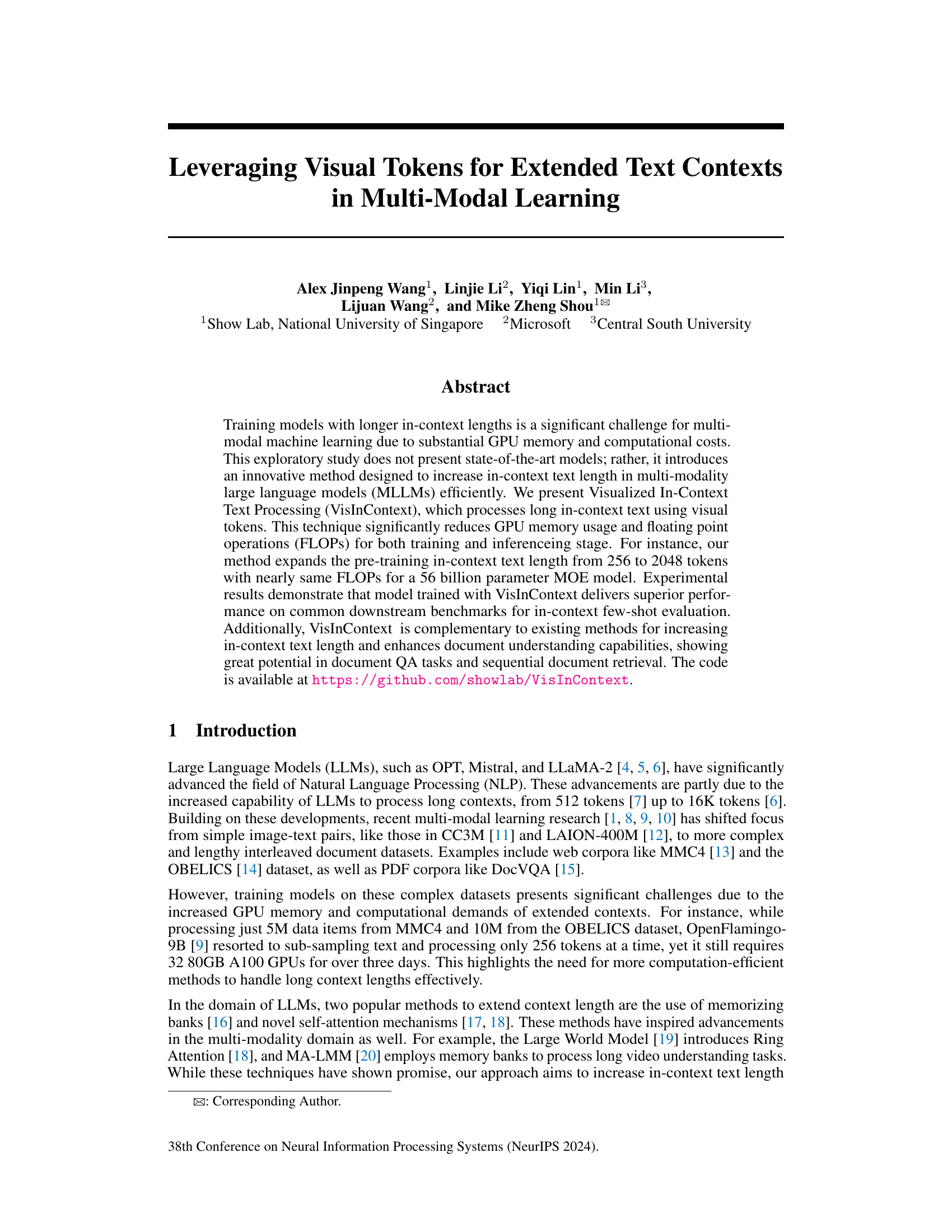

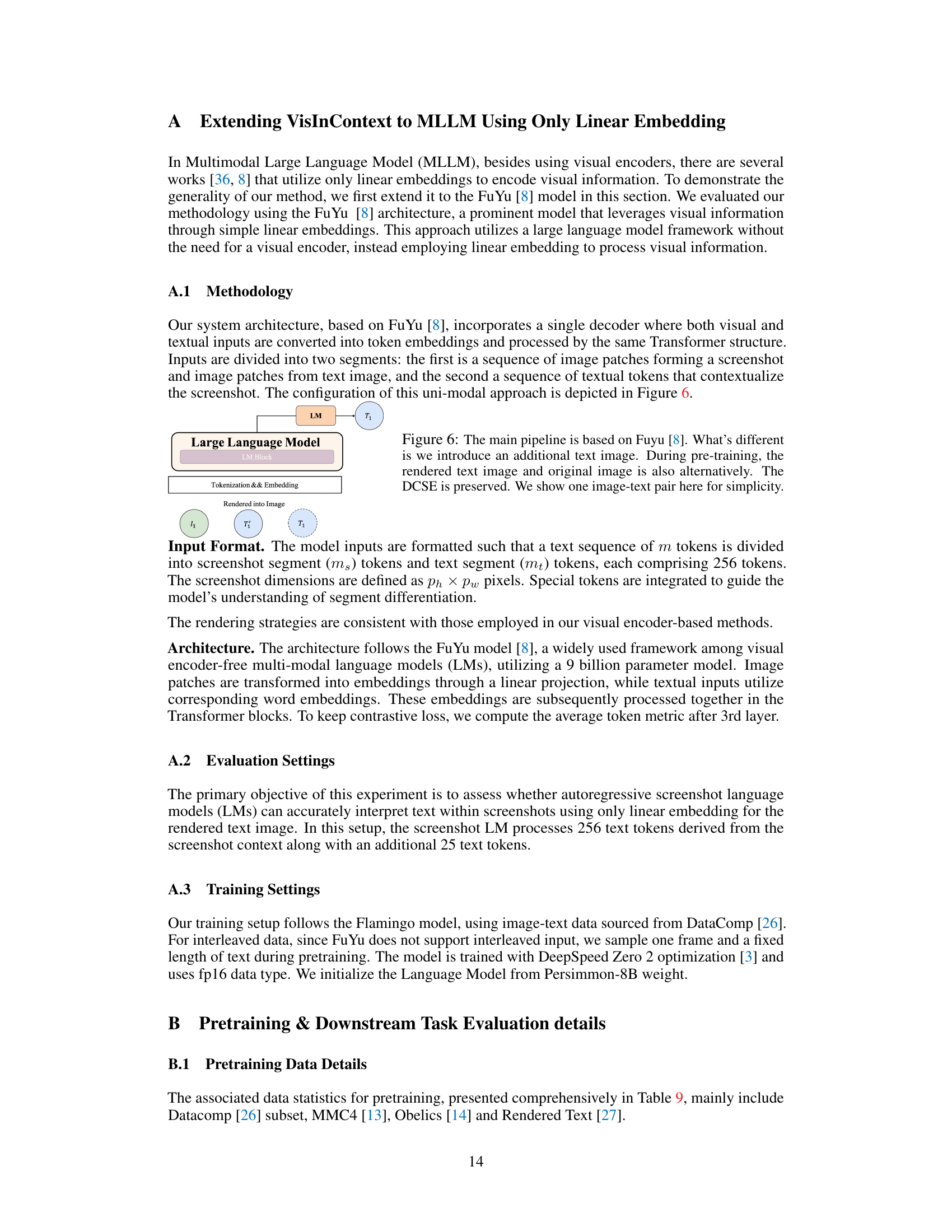

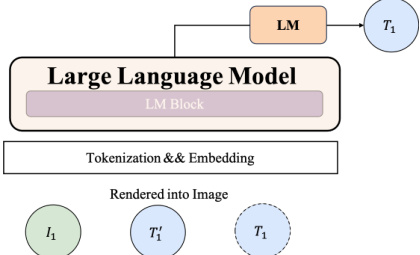

The figure illustrates the VisInContext pipeline, which extends the Flamingo model’s ability to process long in-context text by converting portions of the text into images and feeding these images, along with the remaining text, into the model. This maintains the model’s text token length but significantly increases the in-context text length, allowing for more context in the few-shot learning process.

This figure shows the impact of VisInContext on GPU memory usage and FLOPs during the pre-training of a 56B parameter MOE model. The left graph illustrates how VisInContext significantly reduces GPU memory consumption while increasing in-context text length from 256 to 2048 tokens. The right graph demonstrates that the increase in in-context length using VisInContext does not result in a significant increase in FLOPs.

This figure shows the impact of using VisInContext on GPU memory usage and FLOPs during pre-training of a large language model. It compares the original method’s memory usage and FLOPs to the VisInContext method across different in-context text lengths. VisInContext significantly reduces the memory usage and FLOPs needed to process long in-context text, allowing for a much greater in-context length with similar computational cost. The experiment was performed on a 56B parameter MOE model using NVIDIA H100 GPUs.

The figure illustrates the VisInContext pipeline, which enhances the Flamingo model’s ability to handle long text contexts. It shows how long text segments are converted into images using an image rendering module, processed by a vision encoder, and integrated with the main text processing stream. This approach effectively increases the ‘in-context text length’ without substantially increasing the number of ’text tokens’, reducing computational costs. The process also involves token masking and text-centric contrastive learning to help the model learn effectively from the image-based textual representations.

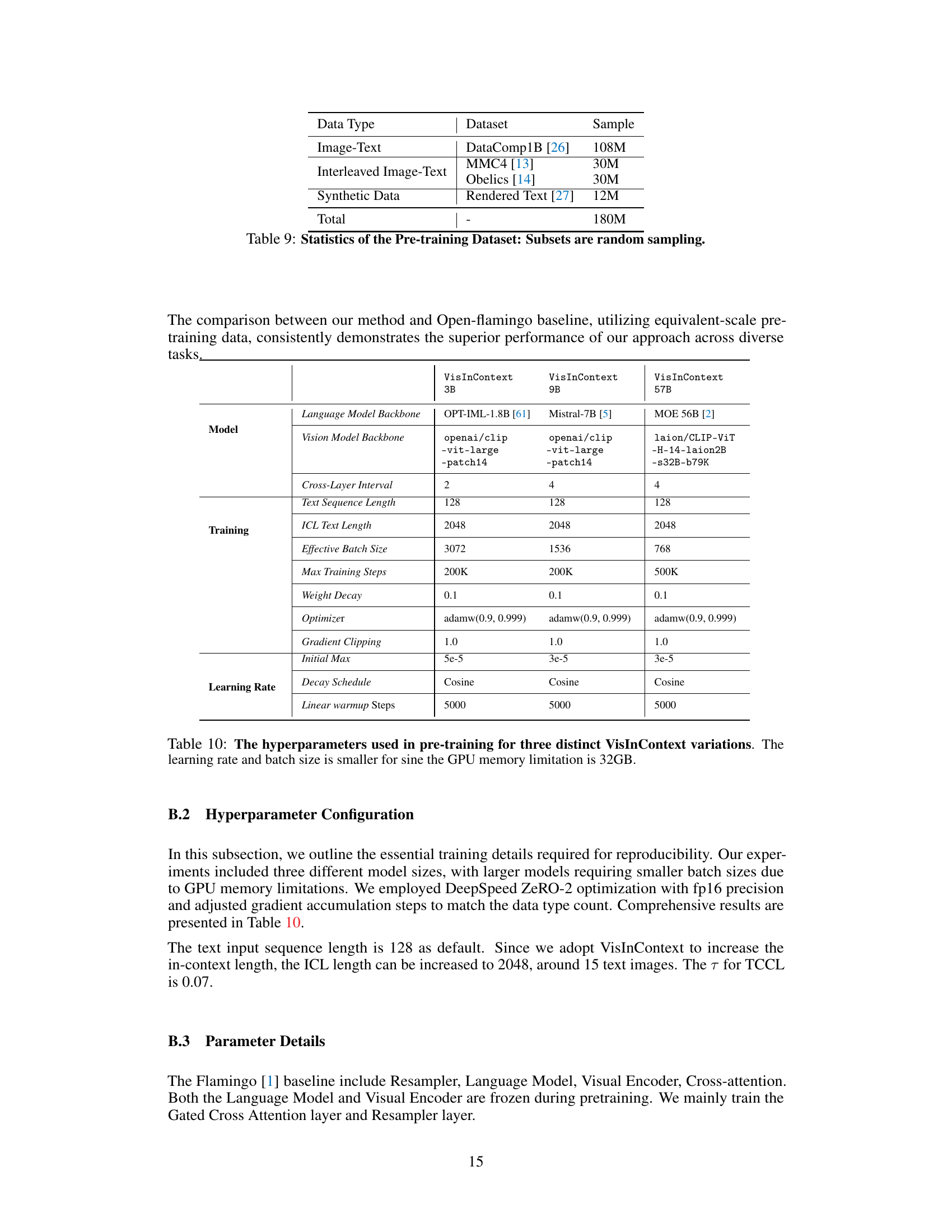

This figure illustrates the architecture of the VisInContext method adapted for the FuYu model, which uses linear embeddings instead of a visual encoder. The key modification is the inclusion of an additional rendered text image, processed alongside the original image. The overall process remains similar to FuYu’s single-stream decoder approach, but now incorporates this additional visual input to improve context understanding.

This figure shows the impact of VisInContext on GPU memory usage and FLOPs during the pre-training of a 56-billion parameter MOE model. The left panel demonstrates that VisInContext significantly reduces GPU memory consumption while allowing for a substantial increase in the in-context length (from 256 to 2048 tokens). The right panel shows that the FLOPs remain relatively constant despite the increased in-context length. This highlights VisInContext’s efficiency in handling longer texts.

More on tables

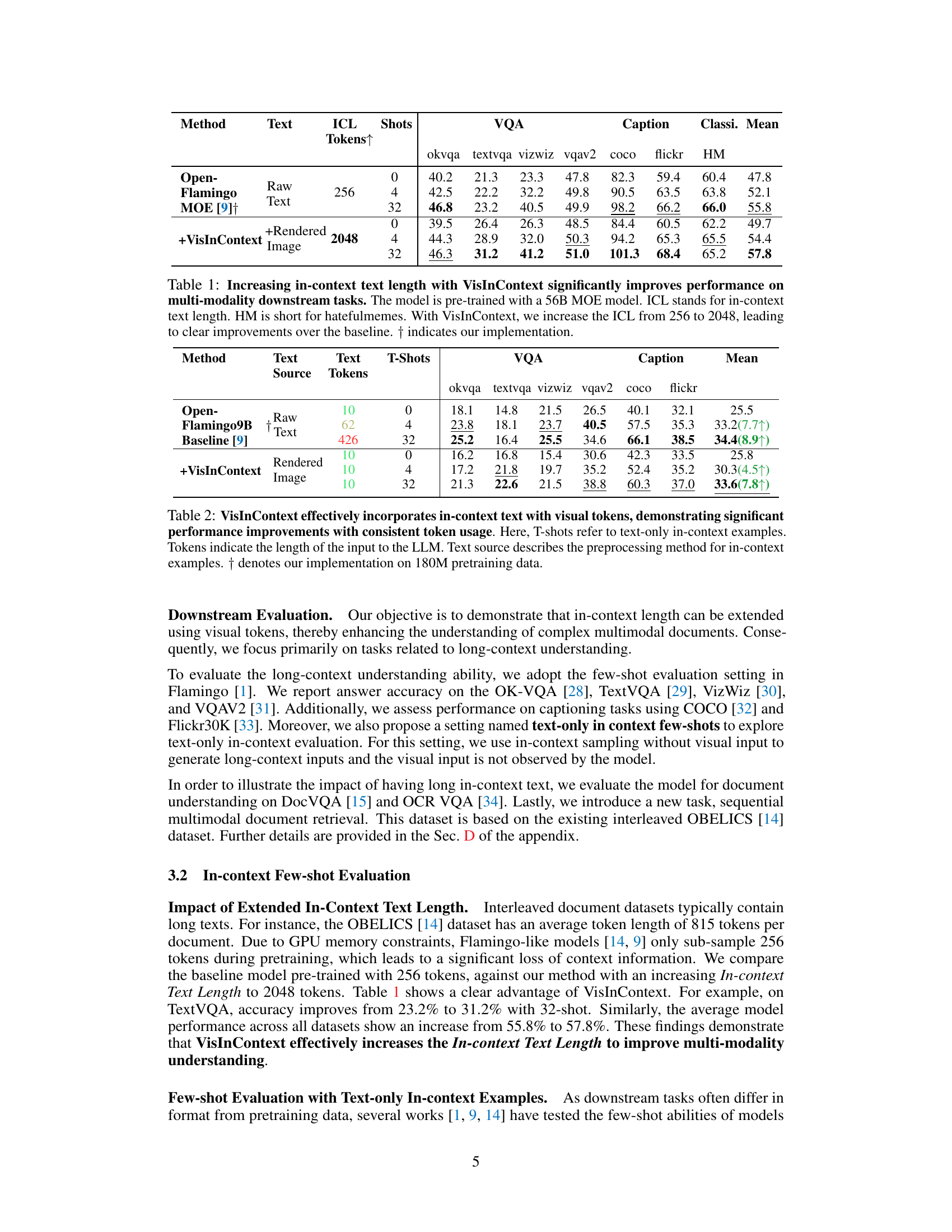

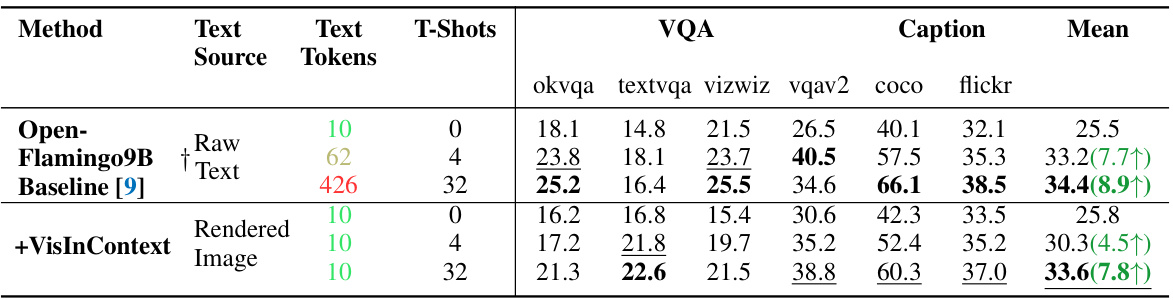

This table compares the performance of VisInContext against a baseline model on various downstream tasks. It shows the impact of using visual tokens to represent part of the in-context text. The table highlights improved performance with VisInContext while maintaining a similar number of text tokens provided as input to the language model. This demonstrates the effectiveness of using visual tokens to extend the effective context length.

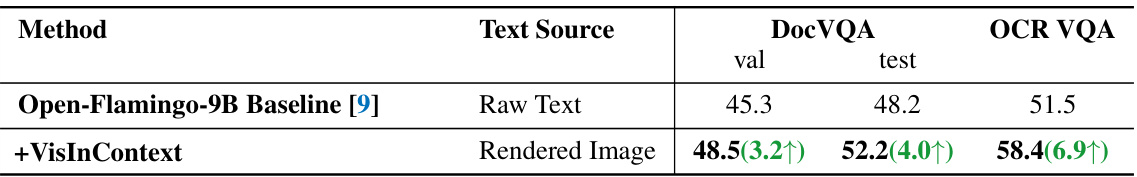

This table shows the performance of VisInContext and the baseline model (Open-Flamingo-9B) on document understanding tasks (DocVQA and OCR VQA). It demonstrates the improvement achieved by using VisInContext, which converts text into images, leading to better understanding of document content. The results are presented for both validation and test sets, showing a consistent performance boost.

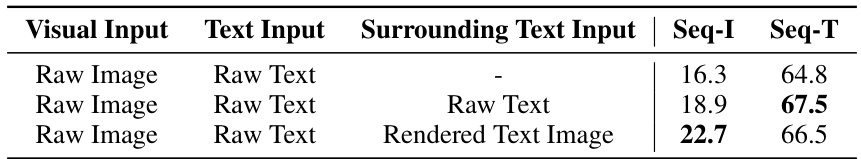

This table presents the results of a sequential multi-modal retrieval task on the OBELICS-Hybrid6 dataset. The task involves predicting the next image and text in a sequence of interleaved image-text data. The table shows the performance of a model pre-trained using the VisInContext method, comparing different input types: raw images and text, or raw images with rendered text images replacing surrounding text. The results demonstrate the improved sequence understanding ability achieved through incorporating VisInContext.

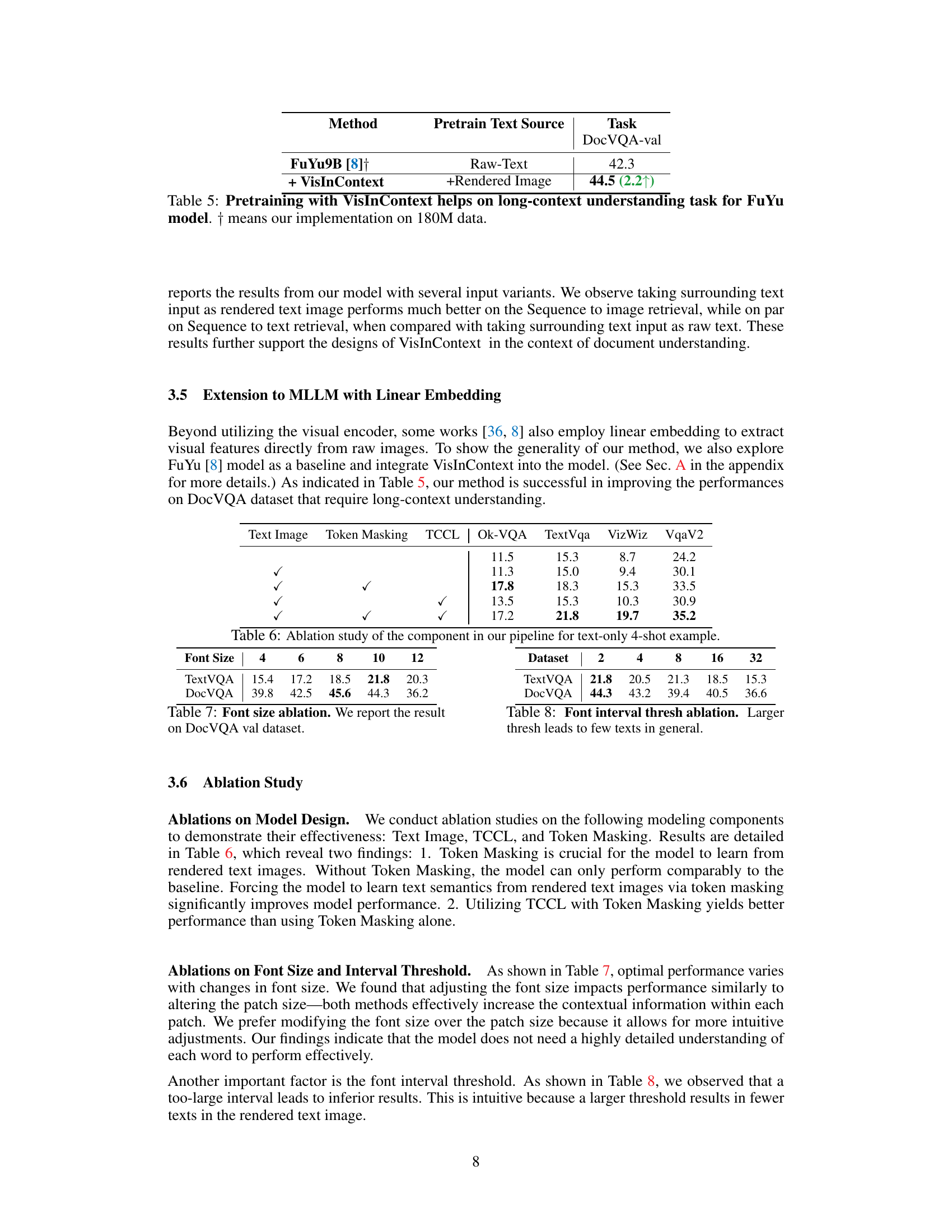

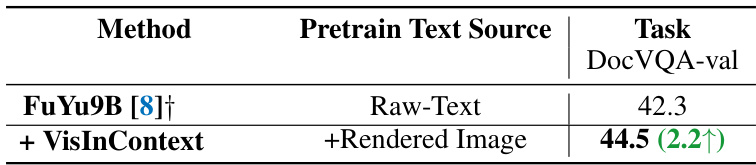

This table presents the results of using VisInContext with the FuYu9B model. The baseline uses raw text for pretraining, while the VisInContext method uses rendered images in addition to raw text. The results show an improvement in performance on the DocVQA-val task when using VisInContext. The improvement is quantified as +2.2 percentage points.

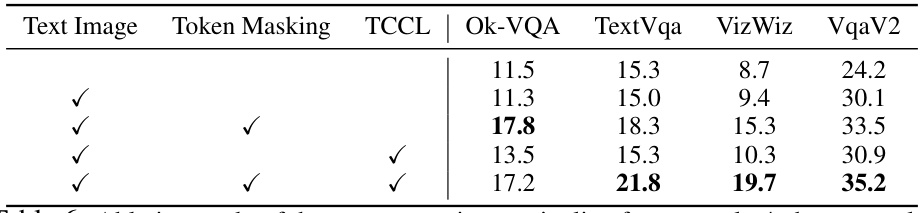

This table presents the ablation study results for a text-only, 4-shot evaluation setup. It shows the impact of different components of the VisInContext method on the performance of the model across various VQA datasets (Ok-VQA, TextVqa, VizWiz, VqaV2). The components evaluated are the use of text images, token masking, and text-centric contrastive learning (TCCL). Each row represents a different combination of these components, with a checkmark indicating that the component was included. The numbers in the table are the average performance scores for each dataset and component combination.

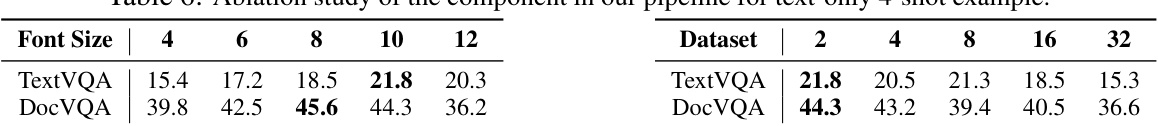

This table presents the ablation study of different components of the VisInContext pipeline, focusing on the text-only setting with 4-shot examples. It shows how performance varies on TextVQA and DocVQA benchmarks when altering the font size (4, 6, 8, 10, 12) and the dataset size (2, 4, 8, 16, 32). The goal is to determine the optimal configuration for text rendering within the VisInContext framework.

This table presents the results of experiments comparing the performance of a model trained with and without VisInContext on several downstream tasks. The model uses a 56-billion parameter Mixture of Experts (MOE) architecture. The key finding is that increasing the in-context length (ICL) from 256 to 2048 tokens using VisInContext significantly boosts performance across all tasks (VQA, Caption, Classification). This demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed VisInContext method for handling longer text contexts in multi-modal learning.

This table details the hyperparameters employed during the pre-training phase of the VisInContext model. It showcases three variations of the model, each with varying language model backbones (OPT-IML-1.8B, Mistral-7B, and MOE 56B). The hyperparameters listed include cross-layer interval, text sequence length, in-context length (ICL), effective batch size, maximum training steps, weight decay, optimizer, gradient clipping, initial learning rate, learning rate decay schedule, and linear warmup steps. Note that the learning rate and batch size are adjusted to account for the 32GB GPU memory limitation.

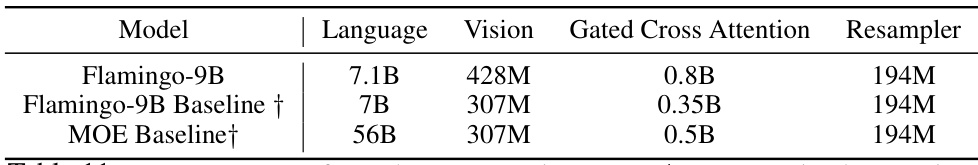

This table shows the number of parameters for each component of three different multimodal large language models (MLLMs). The models are Flamingo-9B, Flamingo-9B Baseline (the authors’ implementation), and MOE Baseline (the authors’ implementation). The components listed are the language model, vision model, gated cross-attention, and resampler. The table highlights differences in parameter counts between the original Flamingo model and the authors’ modified versions.

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the impact of VisInContext on several downstream multi-modal tasks. A 56-billion parameter Mixture of Experts (MOE) model was used. The table shows a significant performance improvement when using VisInContext to extend the in-context length from 256 to 2048 tokens, indicating the effectiveness of the proposed method in handling longer text sequences. Results are shown for various metrics across different datasets (OK-VQA, TextVQA, VizWiz, VQAv2, COCO, Flickr, and HatefulMemes).

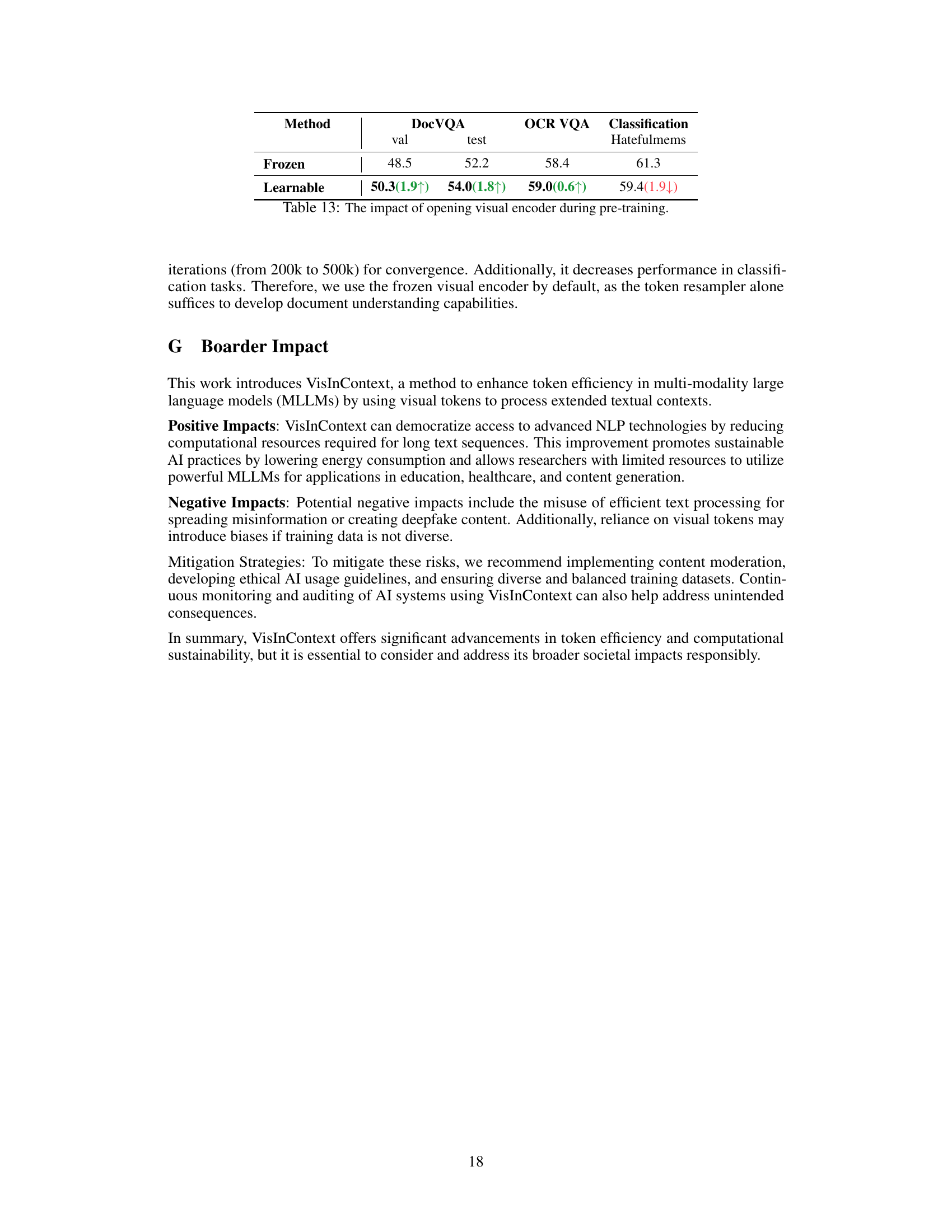

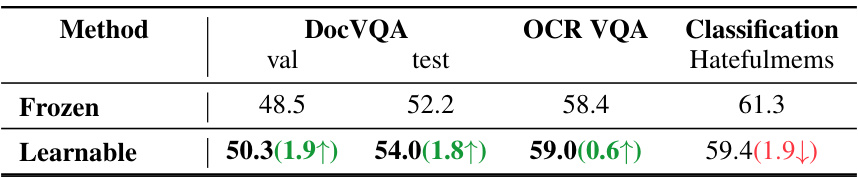

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing two approaches to using the visual encoder in the model during pre-training: a frozen visual encoder and a learnable visual encoder. The performance of the model is evaluated on three downstream tasks: DocVQA (validation and test sets), OCR VQA, and Hatefulmems classification. The numbers in parentheses indicate the improvement compared to the frozen visual encoder approach. A positive number shows an increase in performance (green) and a negative number shows a decrease in performance (red). The table highlights a trade-off: while enabling the visual encoder during training improves some downstream tasks, particularly the document understanding tasks, it also introduces instability and slightly harms performance on the classification task.

Full paper#