↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world problems involve data that’s best represented as functions (images, time series etc.), rather than simple vectors. Current diffusion models, a powerful class of generative models, primarily operate on finite-dimensional data, limiting their effectiveness with functional data. This creates the need to extend diffusion models to function spaces for richer, more natural representations.

This work addresses this gap by developing a novel theory of stochastic optimal control in function spaces. It cleverly leverages Doob’s h-transform, a key tool in building diffusion bridges, to create a framework for generative modeling directly in infinite-dimensional spaces. The researchers show how to solve a specific optimal control problem is equivalent to learning a diffusion model, enabling practical applications such as learning smooth transitions between probability distributions in function spaces and simulation-based Bayesian inference.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it bridges the gap between the theory of stochastic optimal control and the practical application of diffusion models in infinite-dimensional spaces. This opens doors for developing new generative models, especially in fields dealing with complex data like images, time series, and probability density functions, which are often represented more naturally in function spaces. The resolution-free nature of the approach also offers significant computational advantages over traditional methods that rely on resolution-specific parameterizations.

Visual Insights#

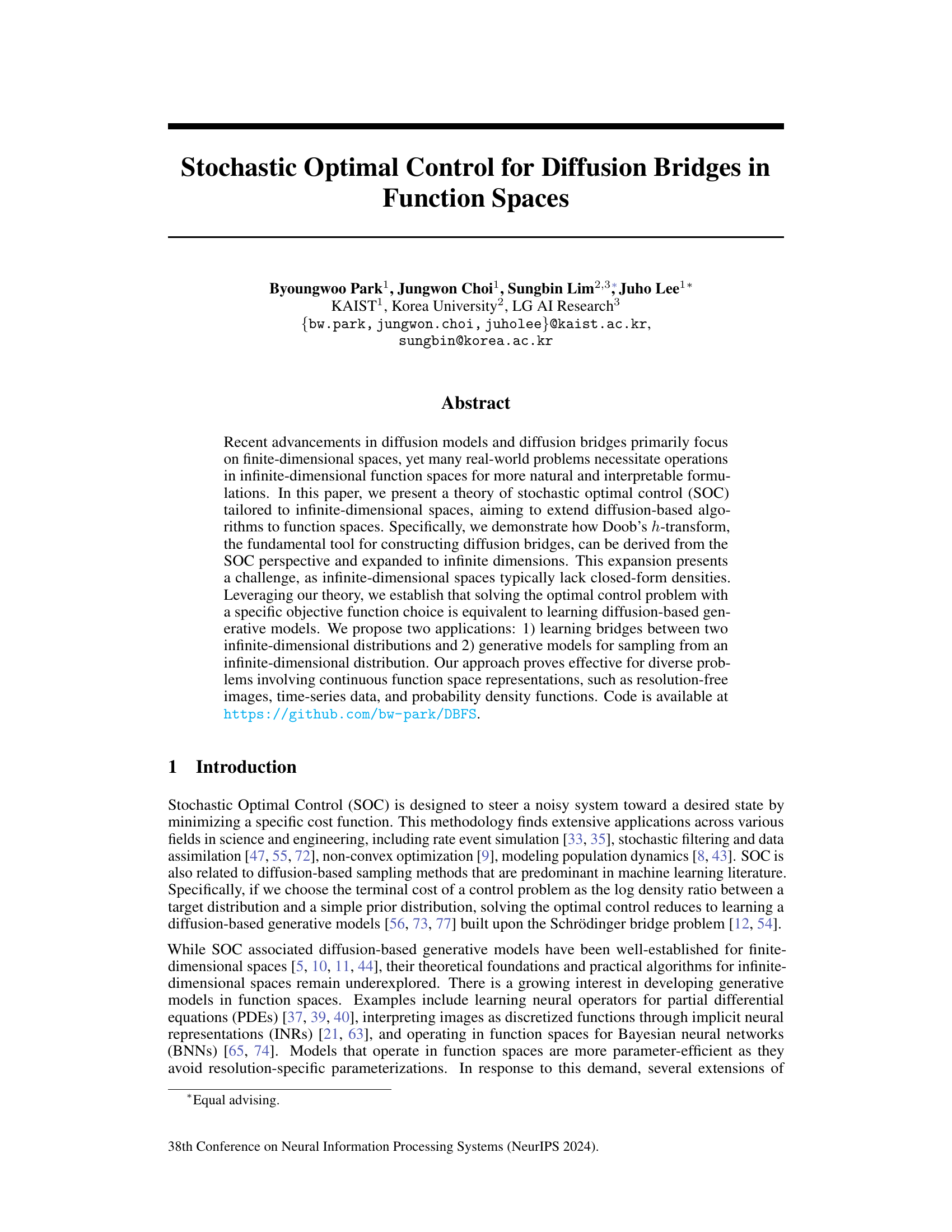

This figure shows the results of a diffusion bridge matching algorithm applied to bridging probability density functions. The top row shows the results when evaluating the learned process on a coarser grid (32x32), while the bottom row shows the results when evaluating on a finer grid (256x256). The figure demonstrates the algorithm’s ability to learn a smooth transition between two probability distributions, even when evaluated at different resolutions. This highlights the algorithm’s resolution-invariance property and its capability of learning continuous functional representations rather than simply memorizing discrete evaluations.

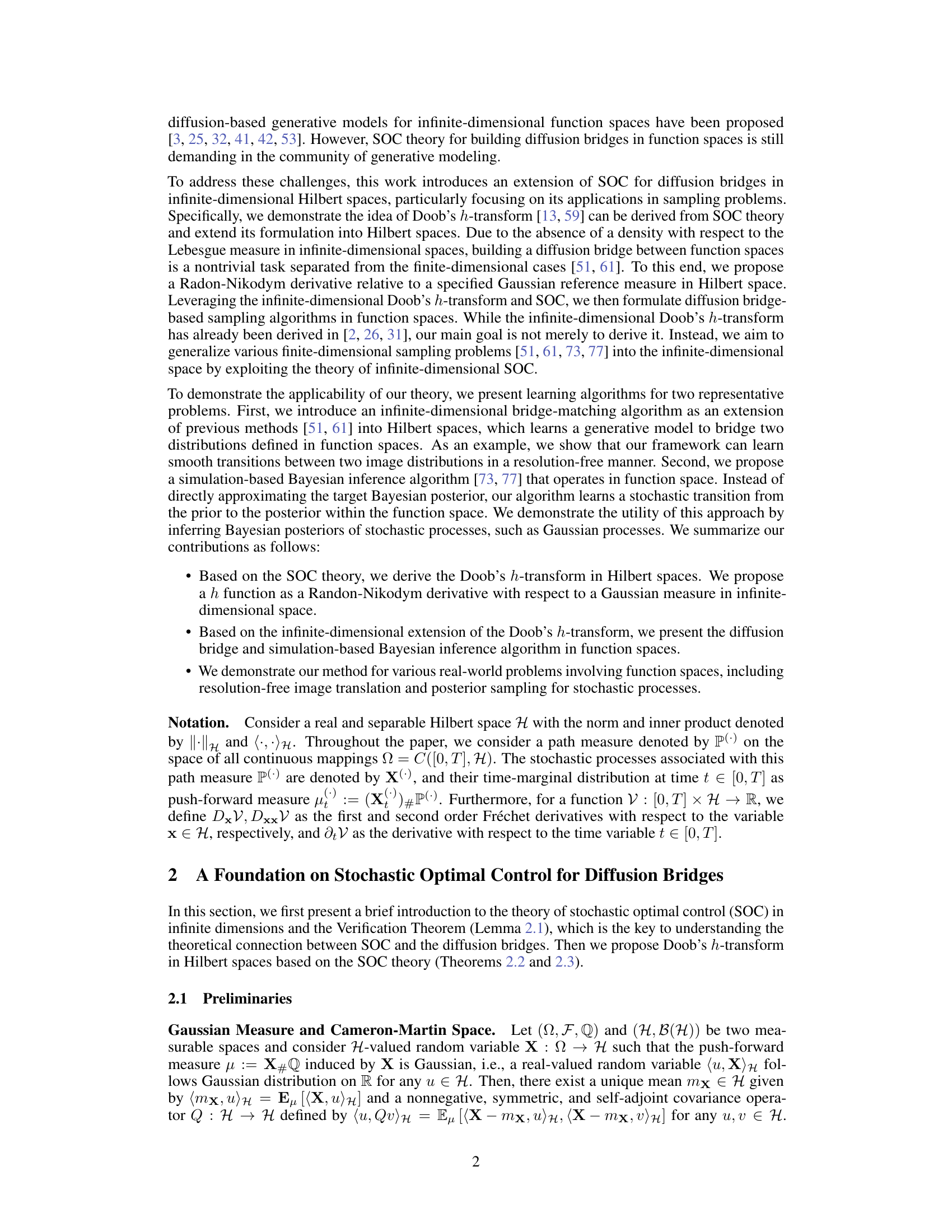

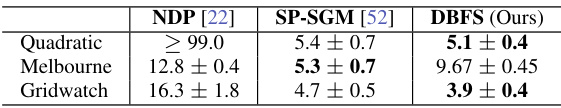

This table presents the results of a kernel two-sample test, a statistical test used to determine whether two samples are drawn from the same distribution. The test was performed on three datasets (Quadratic, Melbourne, and Gridwatch) for 1D function generation, comparing the performance of the proposed DBFS method against two existing baselines, NDP [22] and SP-SGM [52]. The ‘Power’ values represent the probability that the test correctly rejects the null hypothesis (that the samples are from the same distribution) when the alternative hypothesis is true (the samples are from different distributions). Lower power suggests lower performance. The results show DBFS performs comparably or better than existing methods on these datasets.

In-depth insights#

Func Space SOC#

The concept of ‘Func Space SOC,’ or Stochastic Optimal Control in Function Spaces, represents a significant theoretical advancement. It extends the well-established framework of SOC, typically applied to finite-dimensional systems, to the more complex realm of infinite-dimensional function spaces. This is crucial because many real-world phenomena, such as image generation and time series analysis, are inherently high-dimensional and are better modeled as functions rather than finite-dimensional vectors. The core challenge lies in adapting the mathematical tools of SOC to function spaces, where concepts like probability densities and gradients require careful reinterpretation. The paper’s exploration of Doob’s h-transform within this context is particularly noteworthy, as it provides a powerful mechanism for constructing diffusion bridges and generative models. The ability to build bridges between two probability distributions within the function space has wide-ranging applications. By framing the problem from an SOC perspective, the authors successfully link optimal control to the process of learning generative models. This offers a unified theoretical lens, where solving optimal control problems is shown to be equivalent to learning diffusion bridges. This framework then opens pathways for novel algorithm designs, potentially leading to more efficient and expressive methods for applications like image generation and Bayesian inference within function spaces. The presented work could pave the way for broader applications in machine learning and beyond, enabling the creation of generative models tailored to the inherent complexity of infinite-dimensional datasets.

Infinite Doob’s#

The concept of “Infinite Doob’s” evokes a fascinating extension of Doob’s h-transform, a crucial tool in stochastic processes, to infinite-dimensional spaces. This generalization is non-trivial because the usual approach relies on probability density functions, which are often unavailable in infinite dimensions. The core challenge lies in defining an appropriate Radon-Nikodym derivative—the fundamental element of the h-transform—with respect to a suitable reference measure in an infinite-dimensional setting. Successfully addressing this challenge would have significant implications. For instance, it could potentially unlock powerful new generative models operating directly in function spaces, enabling more efficient and natural representations of complex data such as images, time series, or probability density functions. The potential also exists for advancements in Bayesian inference, providing more efficient methods for estimating posterior distributions in high-dimensional scenarios. However, the theoretical and computational hurdles remain significant, including the selection of appropriate reference measures and the development of efficient algorithms to compute the infinite-dimensional h-transform.

Bridge Matching#

The concept of ‘Bridge Matching’ in the context of this research paper likely refers to a method for learning a generative model that smoothly connects two probability distributions in a high-dimensional space, such as a function space. The core idea is to learn a stochastic transition that maps samples from one distribution to the other, effectively bridging the gap between them. This is achieved by solving a stochastic optimal control (SOC) problem. The SOC formulation provides a principled approach to learning this transition by carefully defining a cost function that penalizes deviations from the desired path. Crucially, the algorithm is designed to operate in infinite-dimensional spaces, a significant advance as most existing diffusion models are limited to finite-dimensional spaces. This extension allows the algorithm to handle complex, high-dimensional data like images or time-series. The authors present experimental results to demonstrate the success of their method in various applications, showing its ability to seamlessly generate samples and handle different resolutions, all while maintaining efficiency and effectiveness. The ‘Bridge Matching’ method offers a powerful tool for generative modeling in function spaces, opening up new possibilities for applications where operating directly in function space provides more natural representations.

Bayesian Learning#

The section on Bayesian Learning presents a novel application of stochastic optimal control in function spaces. It cleverly addresses the challenge of sampling from an unknown target distribution, a common problem in Bayesian inference. Instead of directly approximating the posterior, the method learns a stochastic transition from a known prior to the target posterior within the function space. This is achieved by defining a specific terminal cost function within the stochastic optimal control framework, making the optimal control problem equivalent to the sampling problem. This approach bypasses the need for explicit density calculations, a significant hurdle in infinite-dimensional spaces. The authors demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach through an experiment on inferring Bayesian posteriors of stochastic processes, highlighting the method’s practical utility and its potential for a wider range of applications where direct sampling from complex posterior distributions is intractable.

DBFS Limits#

The heading “DBFS Limits” prompts a thoughtful analysis of the Diffusion Bridges in Function Spaces (DBFS) framework’s shortcomings. A key limitation is the computational cost, particularly for high-dimensional function spaces. Infinite-dimensional spaces lack closed-form densities, necessitating approximations which can impact accuracy and efficiency. The reliance on specific cost function choices for optimal control further restricts applicability, as the selection of the cost function significantly impacts the algorithm’s performance and can be challenging. The framework’s effectiveness might be limited by the choice of the Hilbert space and the associated operators, potentially leading to problems with convergence or stability. Furthermore, the approximation of path measures introduces another layer of uncertainty, potentially compromising the accuracy of the simulation-based methods that rely on them. Finally, the generalizability to different problem domains may be limited, given the framework’s dependence on the specific properties of the Hilbert space chosen. Addressing these limitations could involve exploring more efficient computational techniques, developing more robust approximation methods, and investigating alternative mathematical frameworks for handling infinite-dimensional systems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

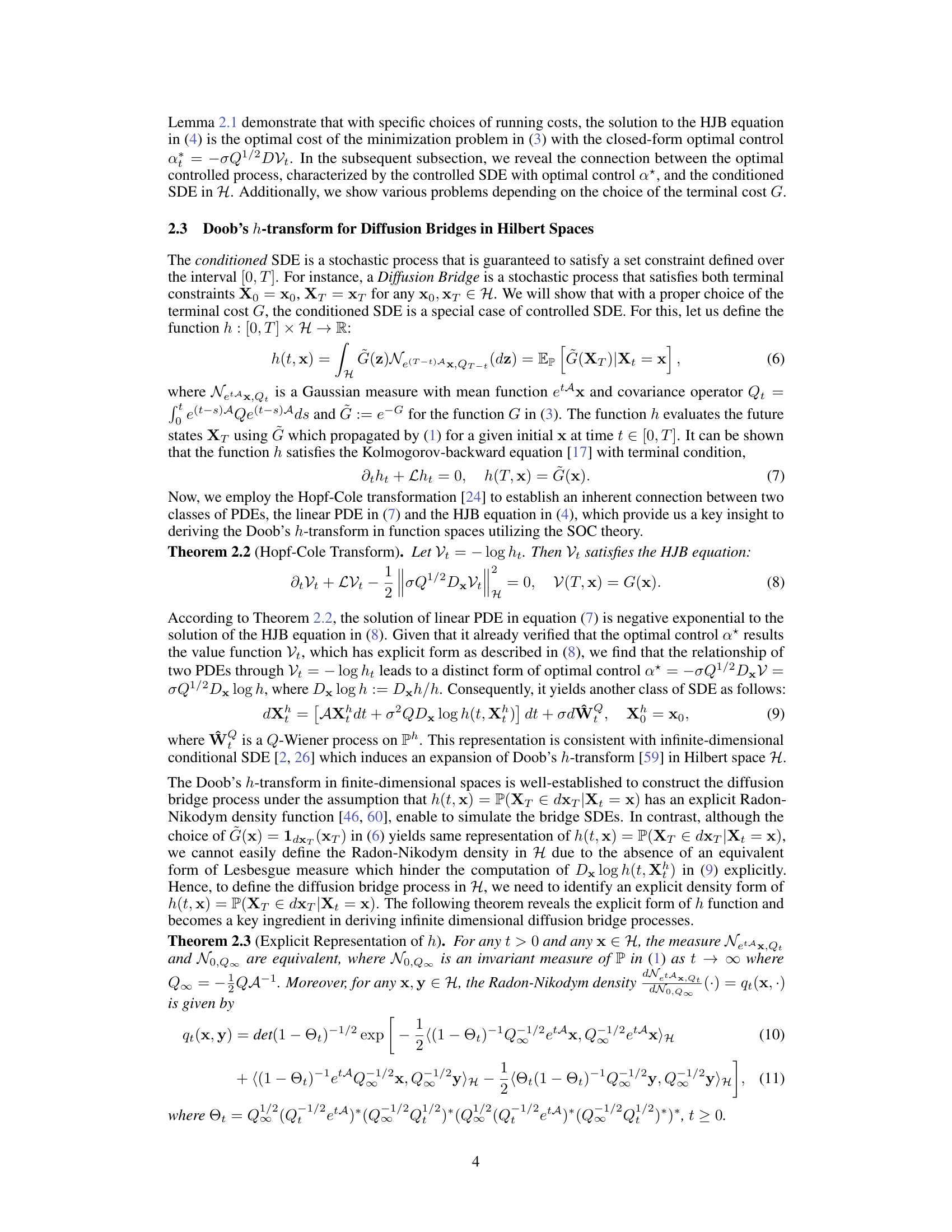

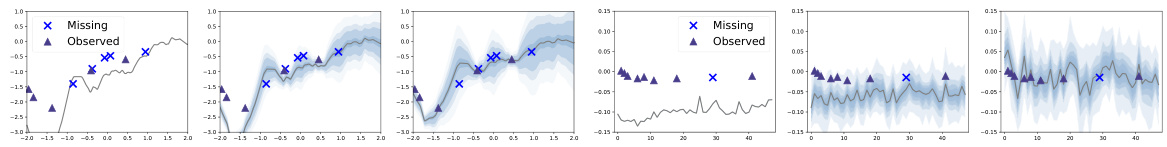

This figure displays the results of 1D function generation experiments using three different datasets: Quadratic, Melbourne, and Gridwatch. The left column shows the real data for each dataset, while the right column shows the samples generated by the proposed model. The plots visually compare the generated samples against the ground truth data, showcasing the model’s ability to generate realistic data that closely resembles the original datasets’ distributions. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed approach in modeling and generating one-dimensional functions.

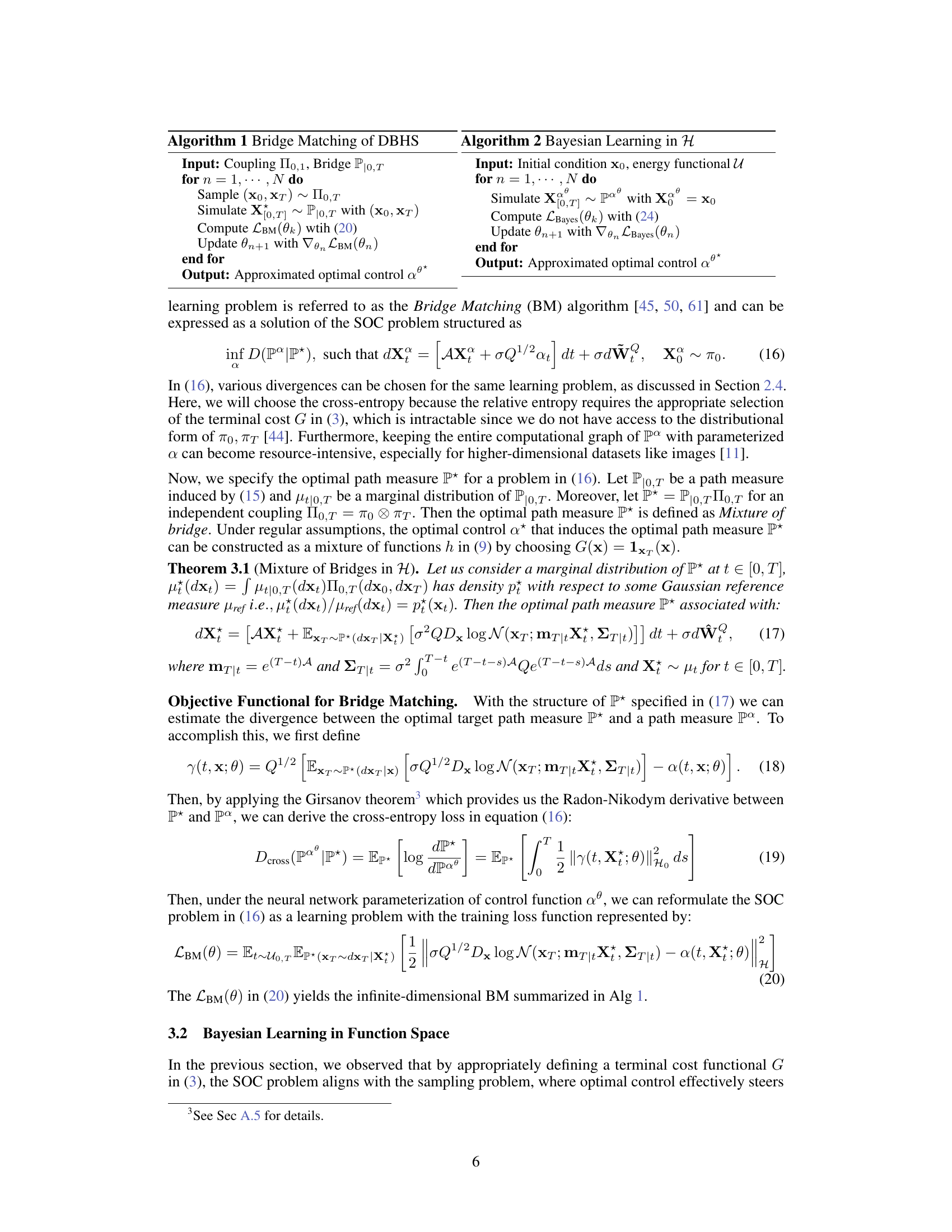

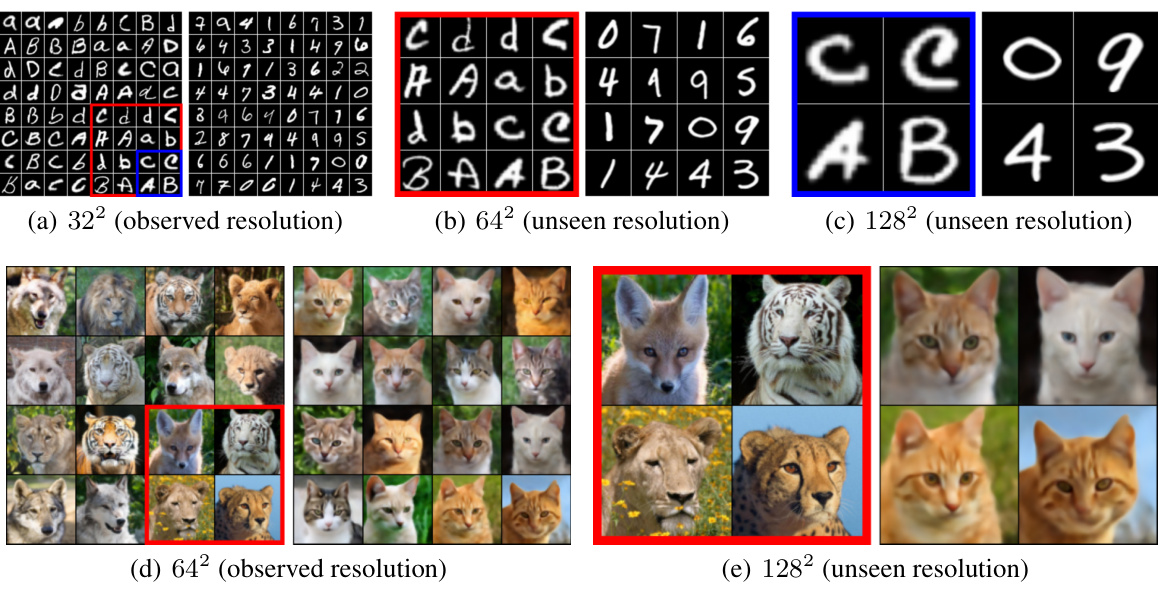

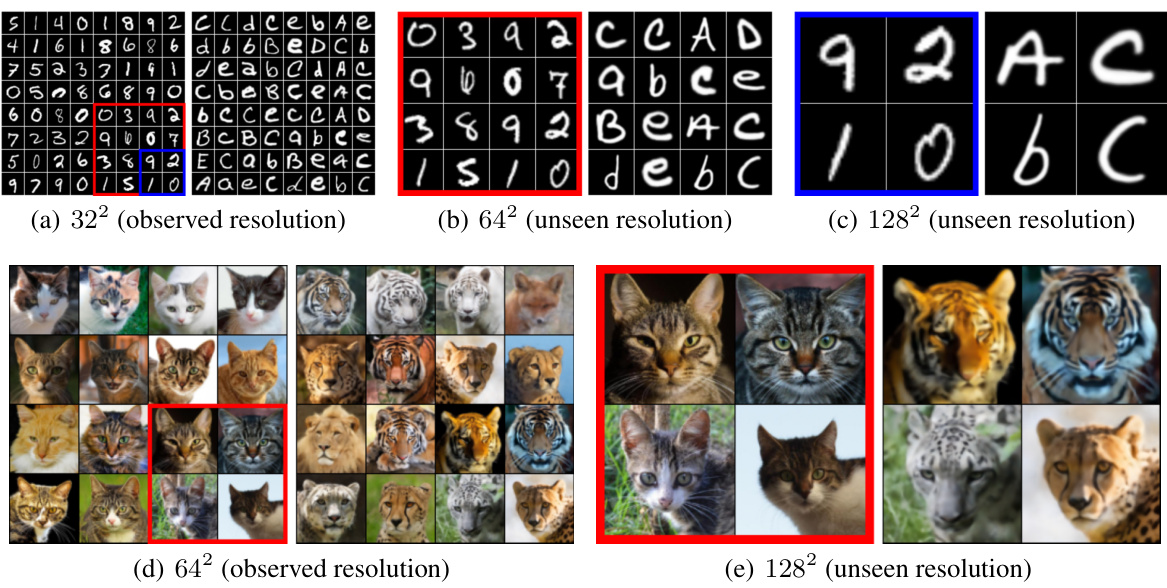

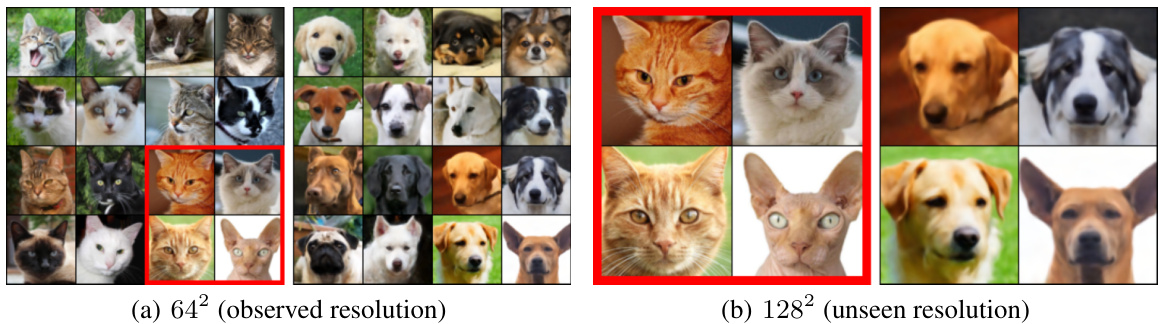

This figure shows the results of an unpaired image transfer experiment using the proposed method. Two datasets are used: EMNIST to MNIST (top) and AFHQ-64 Wild to Cat (bottom). The left side displays real images from the target datasets, and the right shows the images generated by the model. The experiment demonstrates the model’s ability to transfer images even at higher resolutions than those it was trained on (unseen resolutions). Images in the red and blue boxes were upsampled before being passed through the model. This highlights the model’s capacity to learn continuous functional representations rather than simply memorizing discrete evaluations.

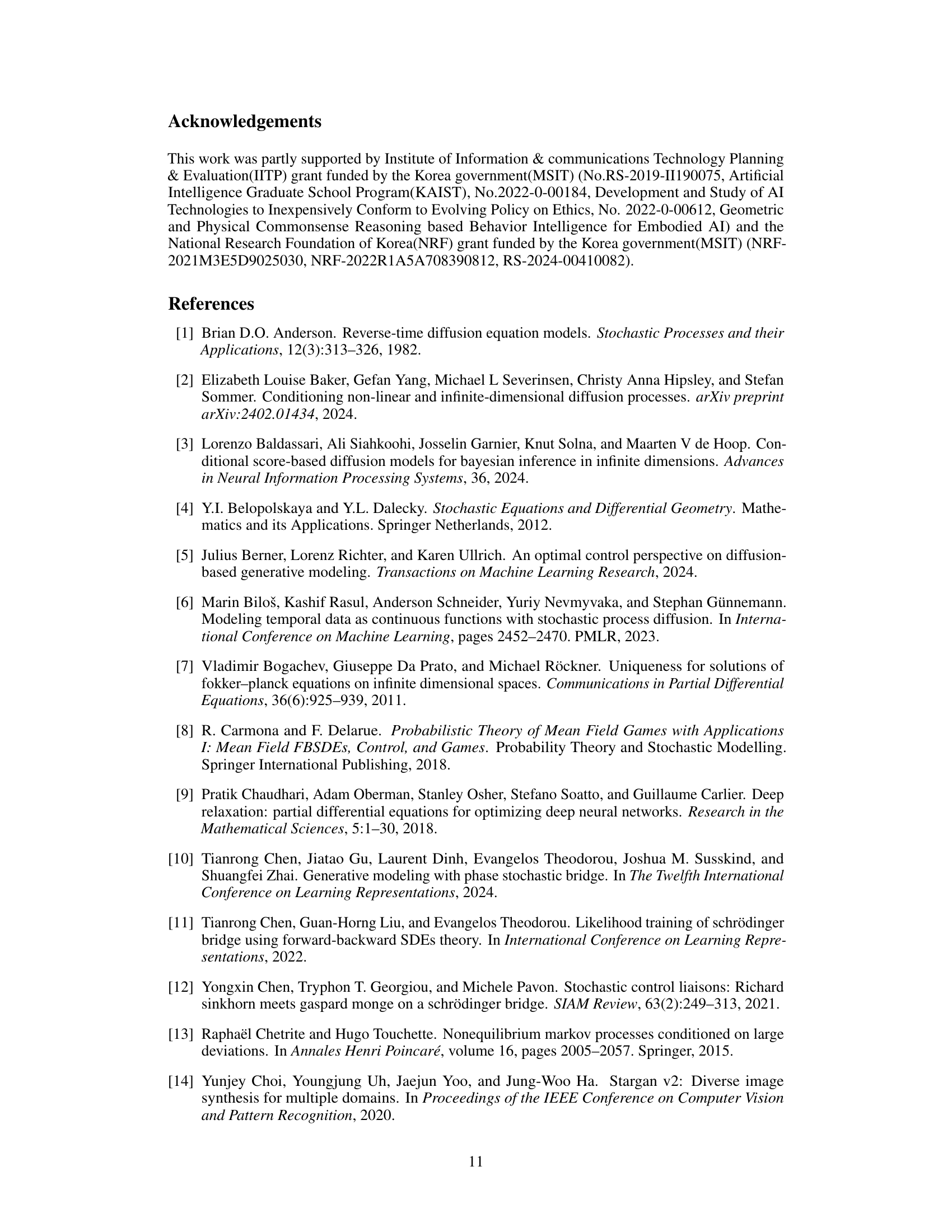

This figure shows the results of applying the Bayesian learning algorithm to generate functions from a learned stochastic process. The left panel displays results using a Gaussian Process with a radial basis function kernel, while the right panel shows results using the Physionet dataset. Each panel shows several sampled functions with the mean and confidence interval. The goal is to illustrate the algorithm’s ability to accurately reconstruct functions from partial observations.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the transformer-based network used in the paper’s experiments. The input is a latent array representing the data (e.g., an image). This is then processed by an encoder, which consists of cross-attention and self-attention blocks. The output from the encoder is further transformed, (e.g., using a projection or GFFT), and fed into a decoder consisting of additional cross-attention and self-attention blocks. Finally, the output of the decoder is transformed into the desired output, such as a generated image.

This figure shows the results of an unpaired image transfer task using the proposed method. The top row demonstrates the transfer from the EMNIST dataset to the MNIST dataset, while the bottom row shows the transfer from the AFHQ-64 Wild dataset to the AFHQ-64 Cat dataset. The left column displays the real data, while the right column displays samples generated using the proposed method. The experiment also tests the model’s ability to generate images at higher resolutions than it was trained on (unseen resolutions), showing the results at 32x32, 64x64, and 128x128 pixel resolutions.

This figure shows the results of an unpaired image translation experiment using the proposed method. The top row demonstrates translation from EMNIST to MNIST, and the bottom row shows translation from wild cat images (AFHQ) to domestic cat images (AFHQ). The left columns show real images, and the right columns show images generated by the model. Notably, the model also generates images at higher resolutions (128x128) than the training resolution (32x32 and 64x64), demonstrating resolution invariance.

More on tables

This table presents the results of a kernel two-sample test, comparing the performance of three different methods (NDP, SP-SGM, and DBFS) in generating 1D functions on three datasets (Quadratic, Melbourne, and Gridwatch). The power of the test represents the probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis that the generated samples and the real data come from the same distribution. Lower power indicates that the generated samples are more similar to the real data. DBFS demonstrates comparable performance to the baselines.

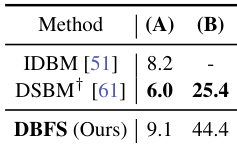

This table shows the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) scores for unpaired image transfer tasks using different methods. Lower FID scores indicate better performance. The table compares the proposed DBFS model against two existing methods, IDBM and DSBM, on two distinct image transfer tasks: EMNIST to MNIST and AFHQ Wild to Cat. The results demonstrate the comparative performance of the DBFS model.

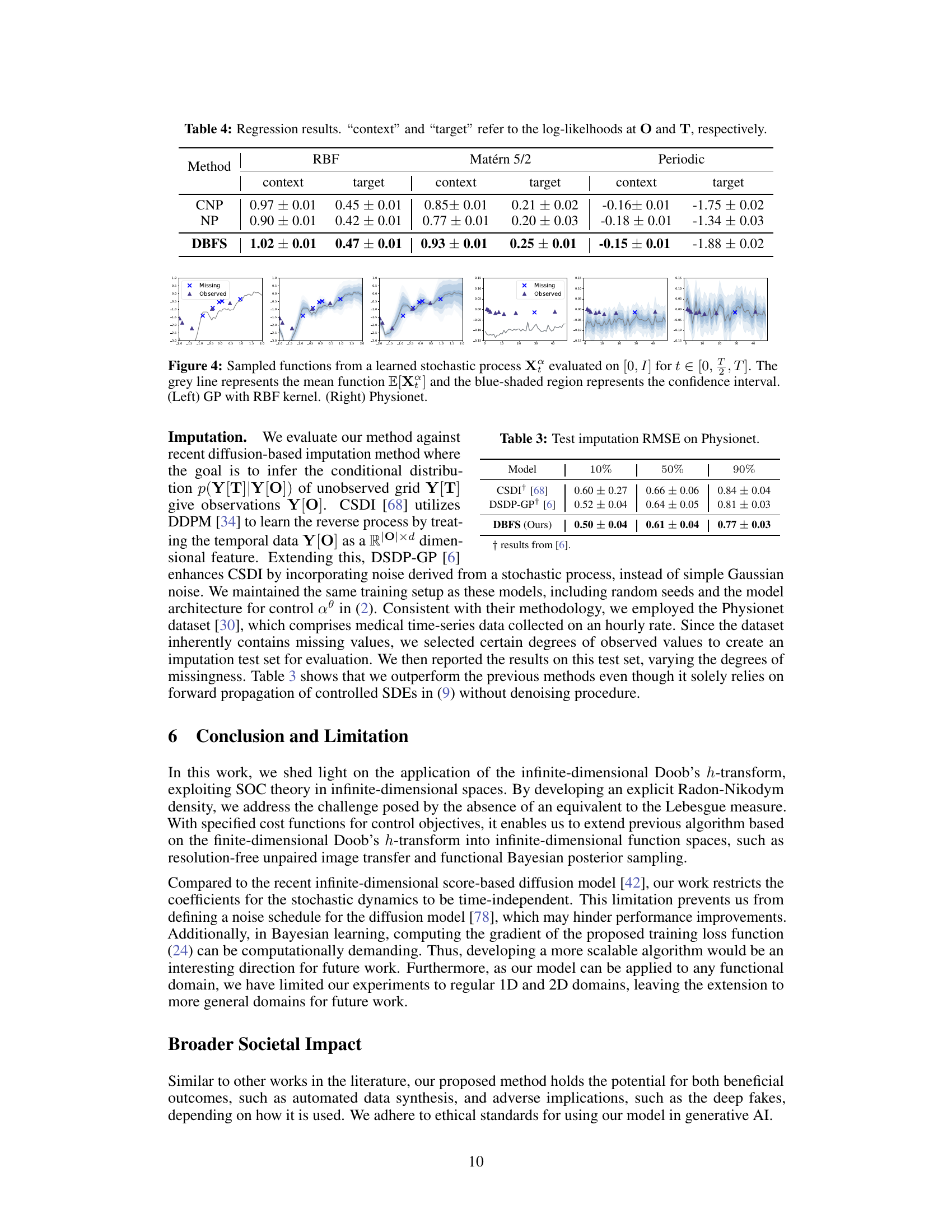

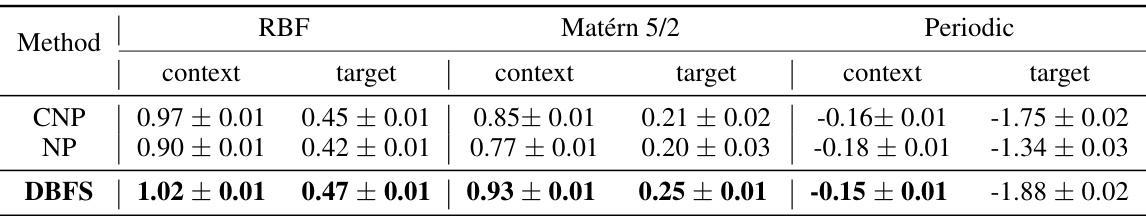

This table presents the results of a regression experiment comparing three different methods: CNP, NP, and DBFS. The methods were evaluated on three different kernel types: RBF, Matérn 5/2, and Periodic. For each method and kernel type, the table shows the context and target log-likelihoods. The context log-likelihood is a measure of how well the model predicts the observed data points (O), while the target log-likelihood measures how well the model predicts the unobserved data points (T). Higher log-likelihood values indicate better performance.

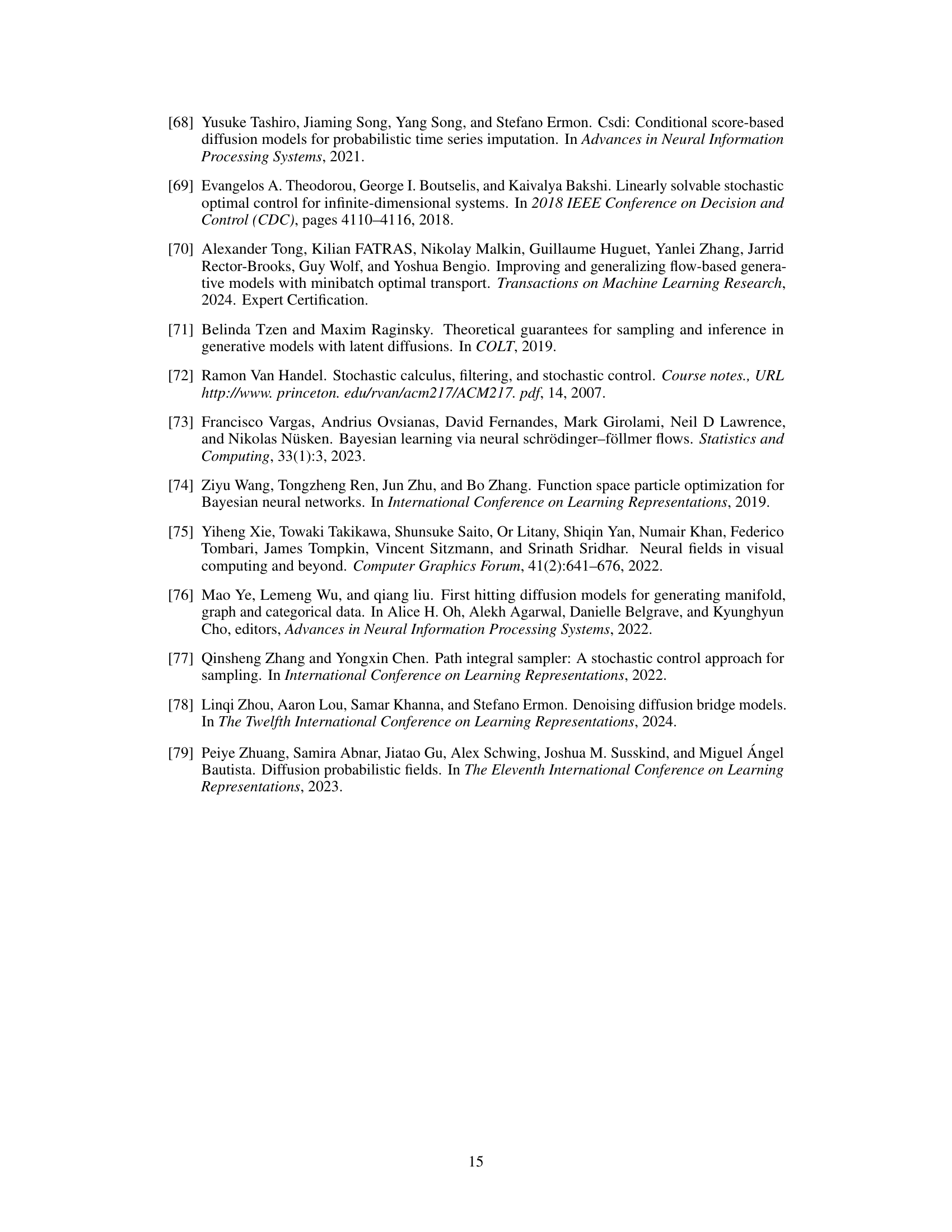

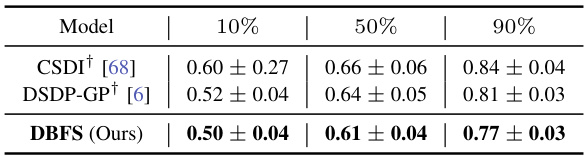

This table presents the root mean squared error (RMSE) for imputation tasks on the Physionet dataset. Three methods, CSDI, DSDP-GP, and DBFS (the authors’ method), are compared across three levels of data missingness (10%, 50%, and 90%). Lower RMSE values indicate better performance.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the Transformer-based network architecture in the experiments. It shows the latent dimension, position dimension, number of heads, number of encoder blocks, number of decoder blocks, number of self-attention layers per block, and the total number of parameters for both the MNIST and AFHQ datasets.

Full paper#