↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Generative AI heavily relies on diffusion models, which gradually transform random noise into structured outputs. However, adapting pre-trained diffusion models to user-specified objectives (like generating images with specific features) faces challenges. Simply using the gradient of the objective function as guidance often disrupts the inherent structure of the generated samples. This paper addresses these issues.

This work introduces a new optimization framework for guided diffusion, demonstrating that gradient-guided diffusion essentially solves a regularized optimization problem. The authors propose a modified form of gradient guidance, “look-ahead loss,” that preserves the latent structure of generated samples. They also present an iteratively fine-tuned version, showing a guaranteed convergence rate. The key contribution lies in providing a strong theoretical understanding and algorithm guarantees for guided diffusion models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it offers a novel optimization perspective on guided diffusion models, a rapidly advancing area in generative AI. By providing a strong theoretical framework and convergence guarantees, it enhances the reliability and efficiency of these models, opening new avenues for research and applications across various fields.

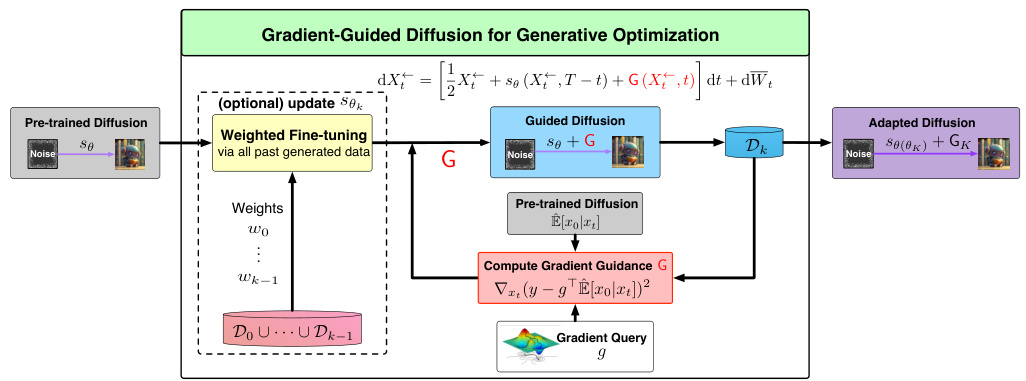

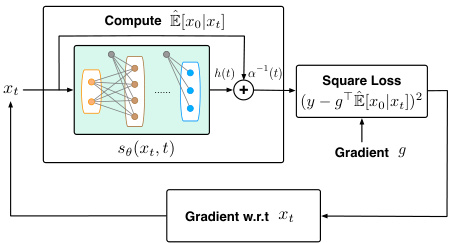

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the architecture of a gradient-guided diffusion model for generative optimization. It shows how a pre-trained diffusion model is adapted to optimize a user-specified objective function by incorporating gradient guidance. The model can optionally include an adaptive fine-tuning step, where the pre-trained score function is updated using newly generated samples. The gradient guidance is computed based on a forward prediction loss that leverages information from the pre-trained score functions, ensuring that the generated samples maintain the latent structure learned from pre-training data. The figure highlights the key components: pre-trained diffusion model, gradient guidance computation, guided diffusion process, optional weighted fine-tuning, and the generation of adapted samples.

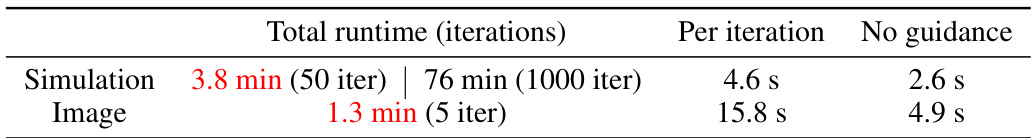

This table summarizes the computational time for Algorithm 1, comparing the total runtime to converge with the time for a single inference of the pre-trained model without guidance. It provides a sense of the additional computational cost introduced by the optimization process.

In-depth insights#

Diffusion Models#

Diffusion models are a class of generative models that have gained significant traction due to their ability to generate high-quality samples from complex data distributions. They operate by gradually adding noise to data through a forward diffusion process, then learning to reverse this process to generate new data points. A key advantage is their flexibility, allowing for conditional generation and guided sampling. The theoretical underpinnings often involve stochastic differential equations (SDEs), score matching, and analysis of the score functions learned during training. Challenges remain in fully understanding the optimization properties of guided diffusion and the behavior of the models in high-dimensional spaces. However, recent research has made progress in these areas, providing theoretical guarantees and convergence rates under certain conditions. Furthermore, algorithmic innovations such as classifier-free guidance improve the efficiency and flexibility of diffusion models. Future directions include further theoretical analysis, development of more robust and efficient training methods, and investigation of applications beyond image generation.

Gradient Guidance#

The concept of ‘Gradient Guidance’ in the context of diffusion models presents a novel approach to steer the generation process towards user-defined objectives. Instead of retraining the entire model, gradient guidance leverages the pre-trained score function, modifying the sampling process by incorporating gradients from an external objective function. This approach is particularly attractive as it maintains the learned structure of the pre-trained model, preventing over-optimization and preserving sample quality. A key challenge lies in effectively designing the guidance signal: simply using the raw gradient can disrupt the underlying latent structure of the generated samples. The research addresses this by proposing a modified gradient guidance that leverages a prediction loss to ensure structure preservation. Furthermore, an iterative fine-tuning process is introduced to improve convergence and potentially achieve global optima. This is achieved by jointly updating the guidance and score network using newly generated samples. The theoretical analysis establishes a link between gradient-guided diffusion and regularized optimization, demonstrating convergence properties under certain conditions, such as concavity of the objective function. The overall approach allows for more flexible and directed generation of samples optimized for specific tasks while preserving the integrity of the pre-trained model.

Optimization Theory#

The optimization theory section of this research paper would likely delve into the mathematical framework underpinning the gradient-guided diffusion models. It would likely establish a strong link between the process of guided diffusion and the solution of a regularized optimization problem, where pre-training data acts as the regularizer. Convergence rates would be a critical aspect, analyzing how quickly the generated samples approach the optimal solution. The concavity or convexity of the objective function would play a significant role in determining the convergence behavior. Furthermore, the analysis likely explores how the design of the guidance itself impacts optimization; a key consideration is the preservation of the underlying data structure during optimization, preventing over-optimization and ensuring the generated samples maintain their desired quality and fidelity. The theoretical analysis might involve proving convergence guarantees under specific assumptions about the data distribution and objective function. Overall, a rigorous exploration of optimization theory provides essential mathematical justification for the effectiveness and efficiency of the proposed gradient-guided diffusion methods.

Adaptive Tuning#

Adaptive tuning in the context of generative models, particularly diffusion models, is a crucial technique for enhancing their capabilities beyond what is achievable through pre-training alone. It allows the model to adapt to specific tasks or objectives without the need for extensive retraining from scratch. This adaptive process is typically iterative, using the output of the model to refine its parameters. A key aspect is how the adaptation process itself is managed. For instance, some methods use a weighting scheme to blend new data with the pre-trained data, striking a balance between adapting to the new information and preserving the knowledge already acquired. This dynamic adjustment allows the model to refine its internal representation of data and its generation process, leading to improved performance on downstream tasks. The success of adaptive tuning hinges on effectively balancing exploration and exploitation. Too much exploration might lead to overfitting, while insufficient exploration may prevent the model from achieving its full potential. Therefore, carefully designing the update rules and hyperparameters is essential for striking the right balance and enabling meaningful adaptation to novel scenarios. Ultimately, adaptive tuning strategies aim to achieve efficient and targeted improvements on generative models, leveraging the benefits of pre-training while enhancing their capacity to perform specific tasks.

Empirical Results#

An ‘Empirical Results’ section in a research paper would present the findings from experiments designed to test the paper’s hypotheses or claims. A strong section would begin by clearly stating what was measured and how. It should then present the results using appropriate visualizations like graphs, tables, or images, ensuring clarity and avoiding chartjunk. Statistical significance should be rigorously assessed and reported (p-values, confidence intervals, etc.), alongside effect sizes to quantify the magnitude of observed effects. The discussion should directly relate the findings to the paper’s theoretical claims, highlighting any consistencies or discrepancies. Potential confounding variables and limitations of the experimental design should be transparently acknowledged, ensuring the results are interpreted within their appropriate context. A comparison to relevant prior work is crucial, positioning the new results within the existing body of knowledge. Finally, a thoughtful interpretation of the results is needed, explaining their implications and suggesting directions for future research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

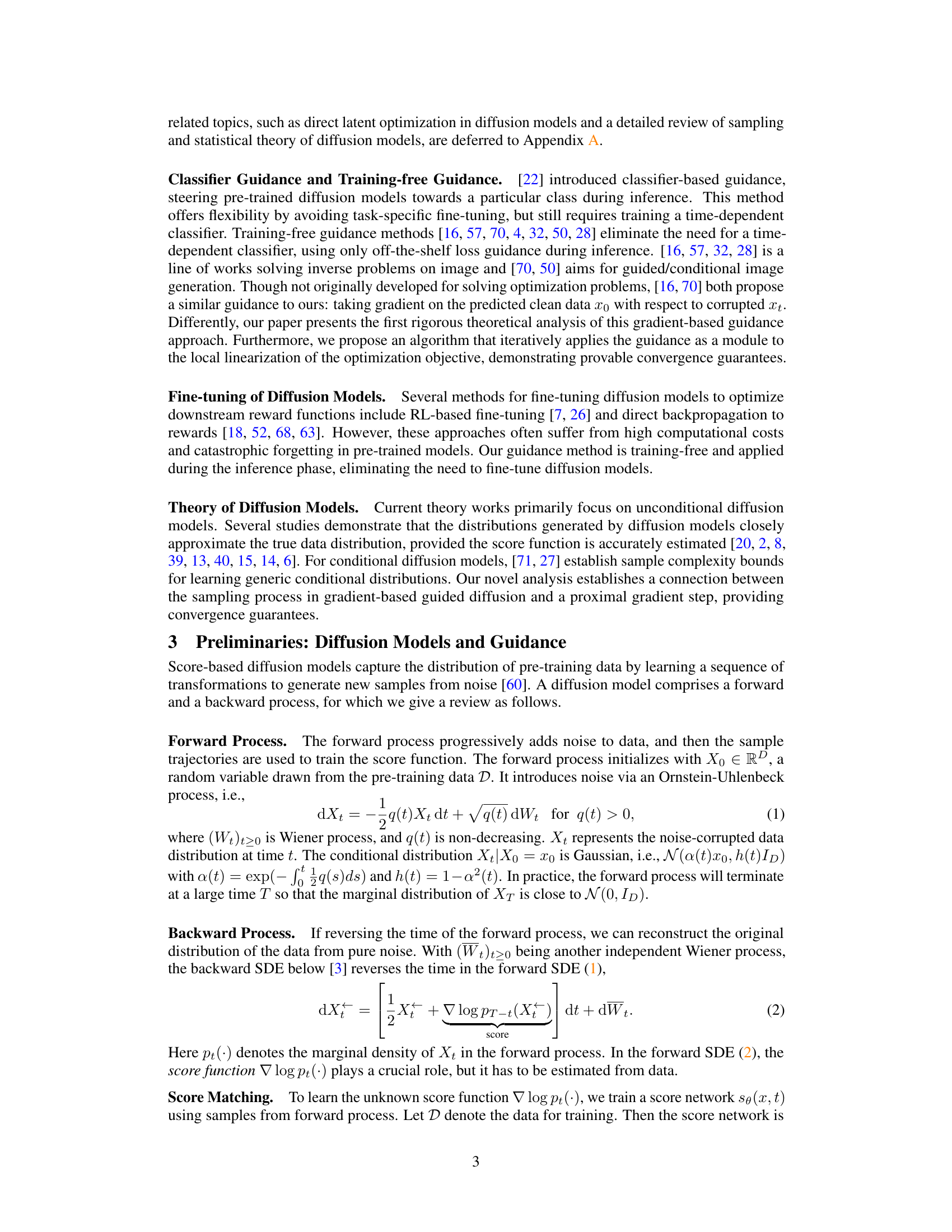

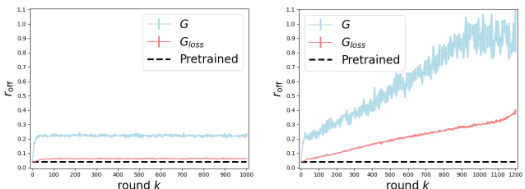

This figure shows that simply applying the gradient of the objective function to the backward process (naive gradient guidance) fails to maintain the data’s latent structure, which is essential for generating high-quality samples. The left panel illustrates how naive gradient guidance can pull samples away from the data’s low-dimensional subspace, while the right panel provides numerical evidence demonstrating that a modified approach (Gloss) significantly reduces the error incurred outside of this subspace.

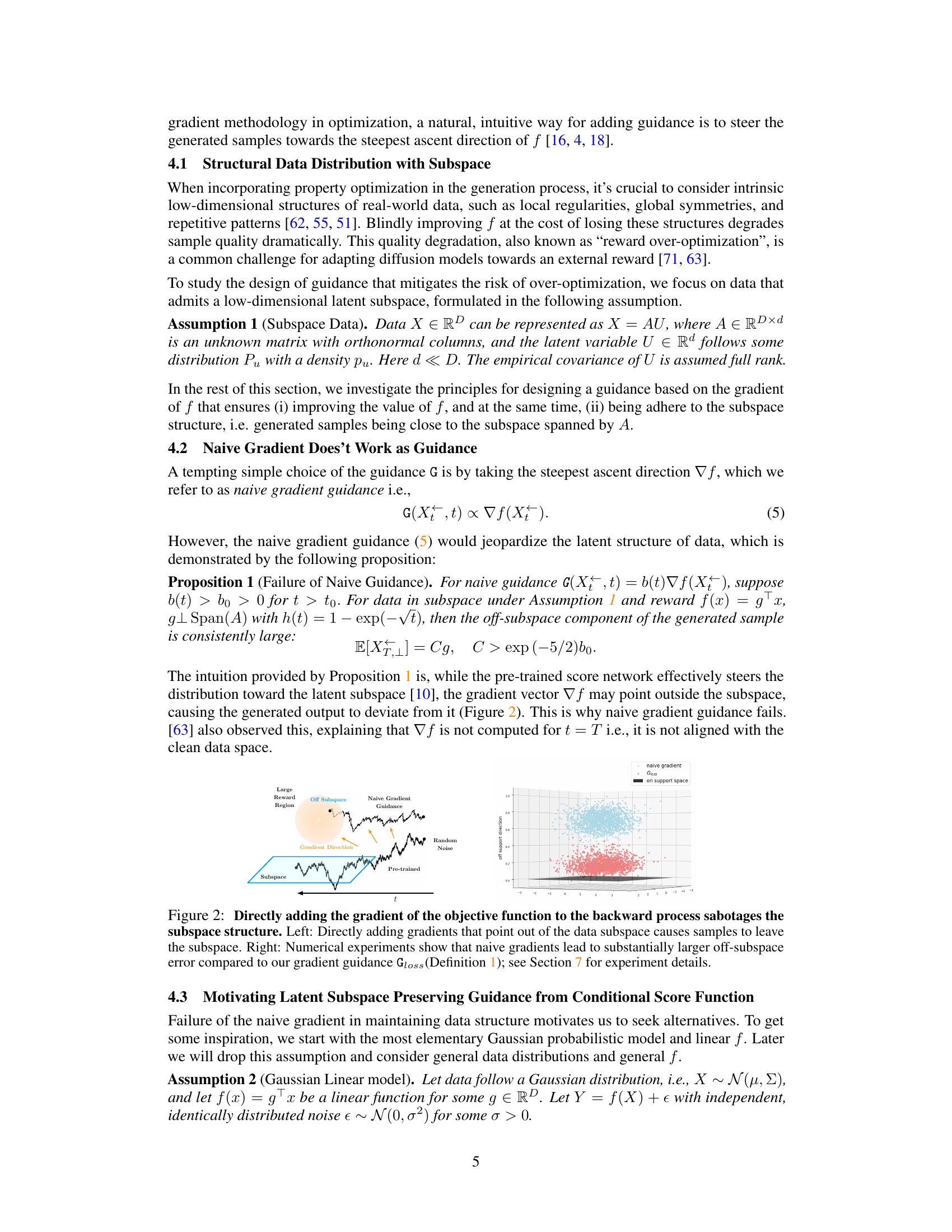

This figure illustrates the computation of the gradient guidance Gloss. It shows the process of taking a noisy sample xₜ, using a pre-trained score network sθ to estimate E[x₀|xₜ], combining this with the gradient g and other parameters via a weighted square loss to compute the gradient w.r.t. xₜ. This gradient is then used as the guidance in the generative optimization process.

This figure compares two gradient guidance methods, G and Gloss, in terms of their ability to preserve the subspace structure of the generated samples. The off/on-support ratio (r_off) is used to measure the proximity of generated samples to the data subspace. The results show that Gloss significantly outperforms G in maintaining the subspace structure, particularly as the number of iterations increases. Subplots (a) and (b) demonstrate this for Algorithm 1 (without adaptive score fine-tuning) and Algorithm 2 (with adaptive fine-tuning), respectively. Subplots (c) and (d) provide zoomed-in views of specific iterations to highlight the differences.

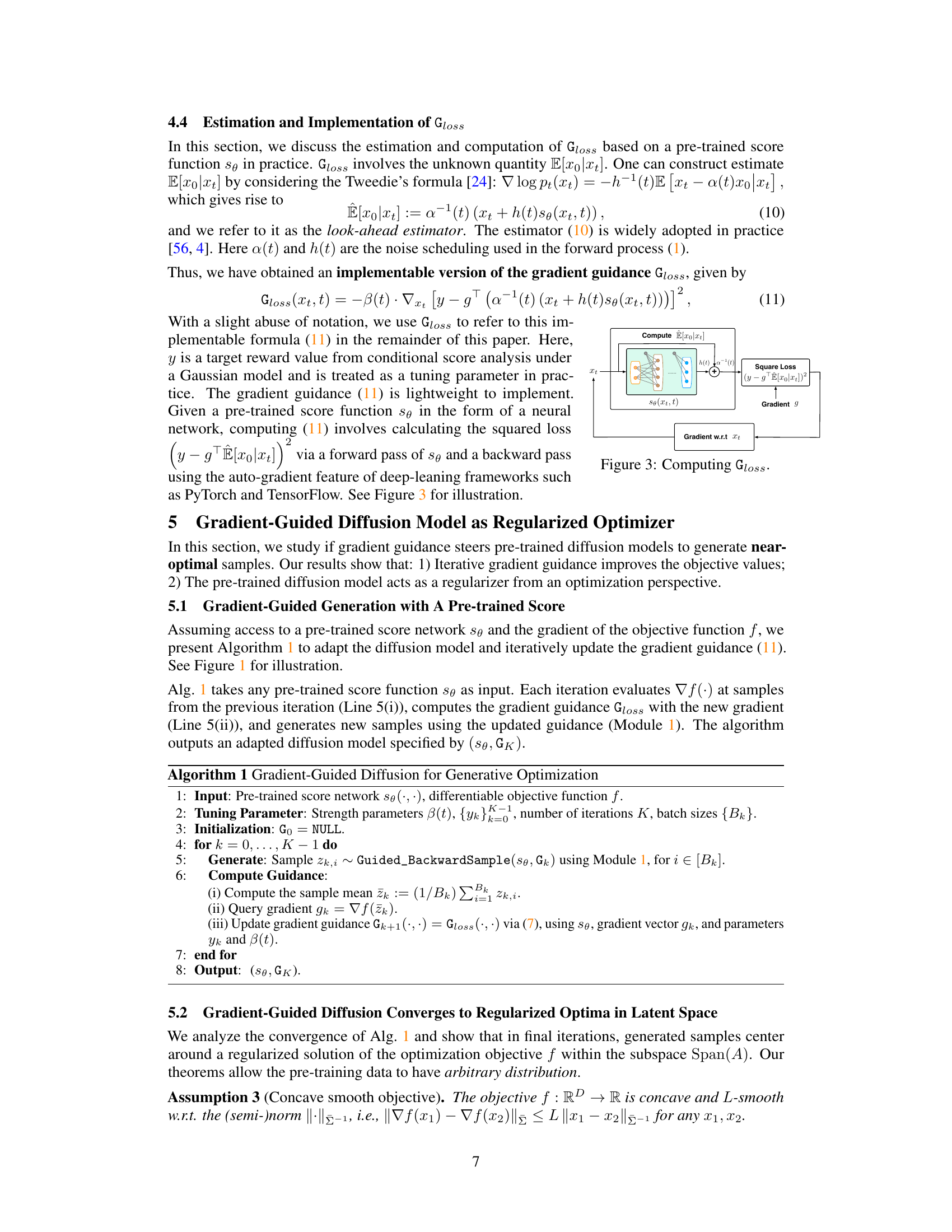

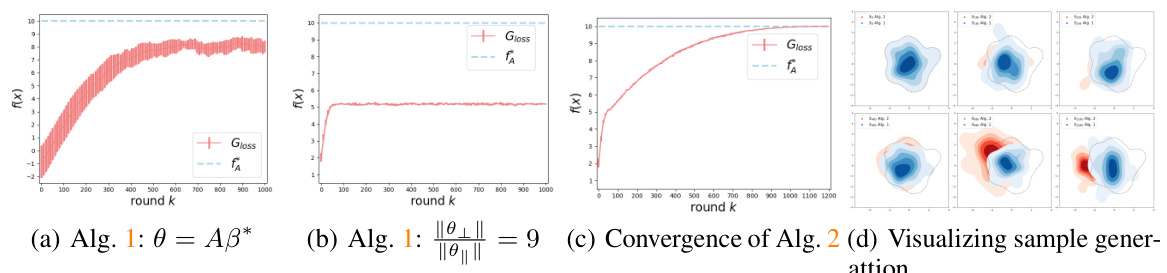

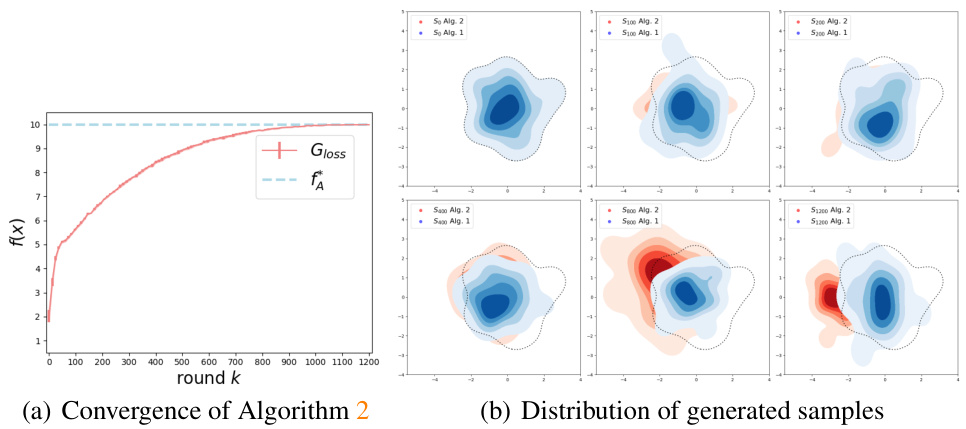

This figure presents the convergence results of Algorithm 1 and Algorithm 2. Panels (a) and (b) demonstrate the convergence behavior of Algorithm 1 under different objective functions, showing that it converges to a sub-optimal value. Panel (c) shows that Algorithm 2 successfully converges to the maximal value of the objective function, indicating its ability to achieve global optima. Finally, panel (d) visualizes the distribution of generated samples for both algorithms, highlighting the differences in their sampling characteristics. Algorithm 2’s samples move beyond the initial data distribution, suggesting its capacity to generate novel samples.

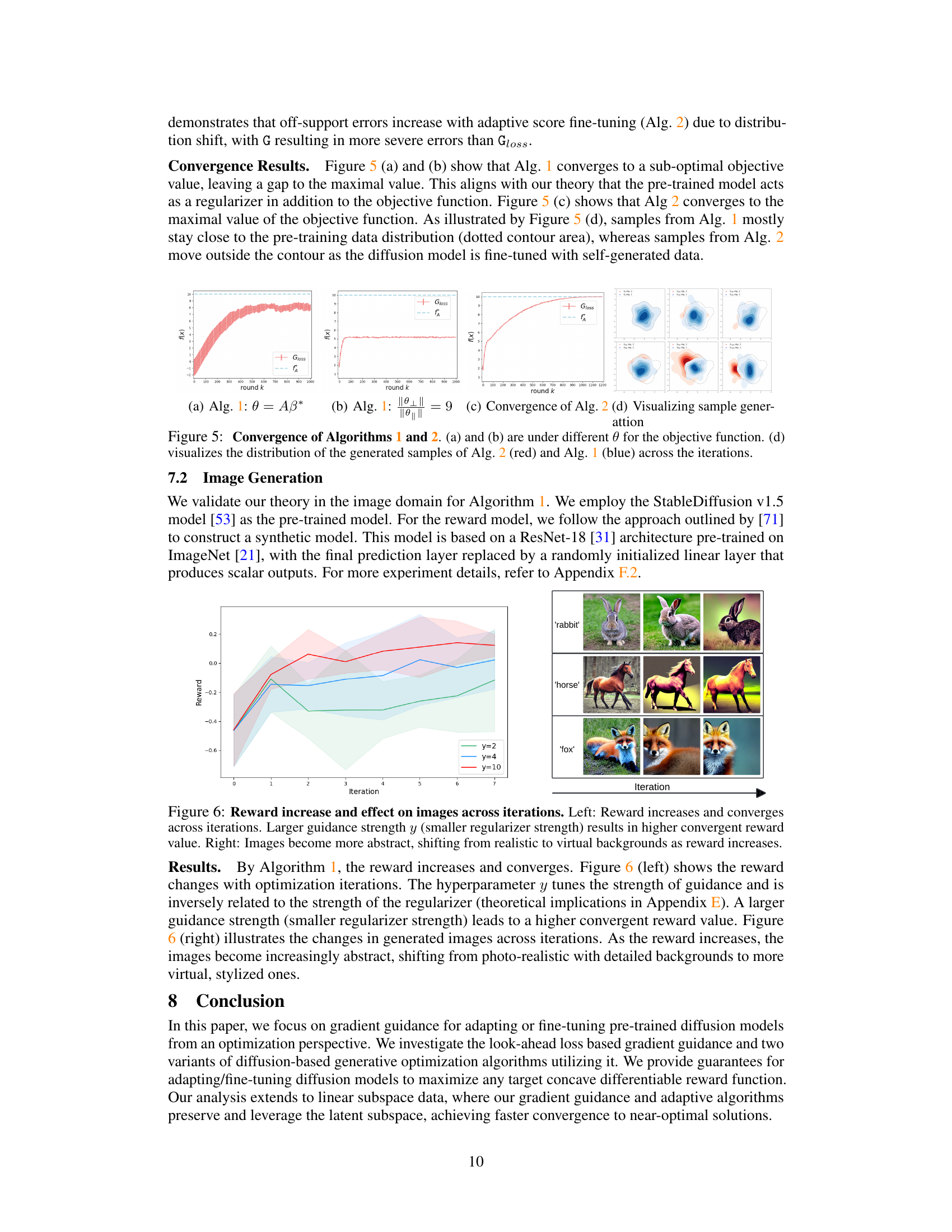

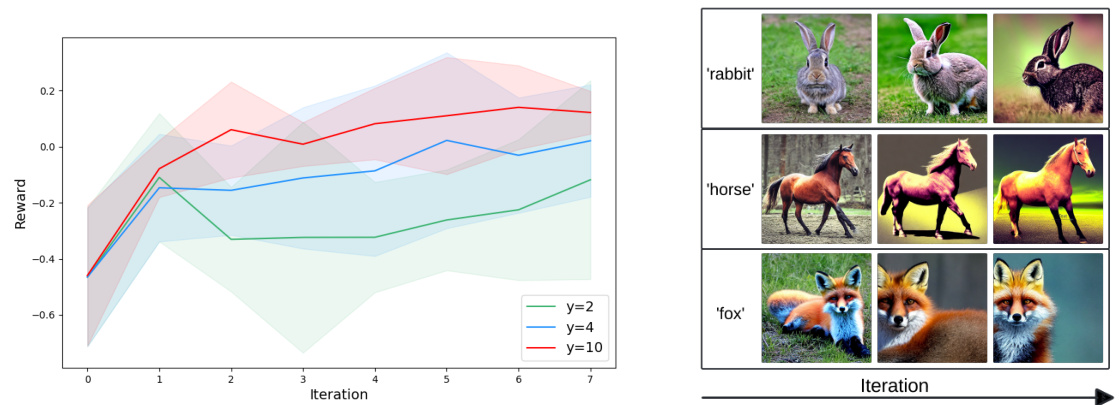

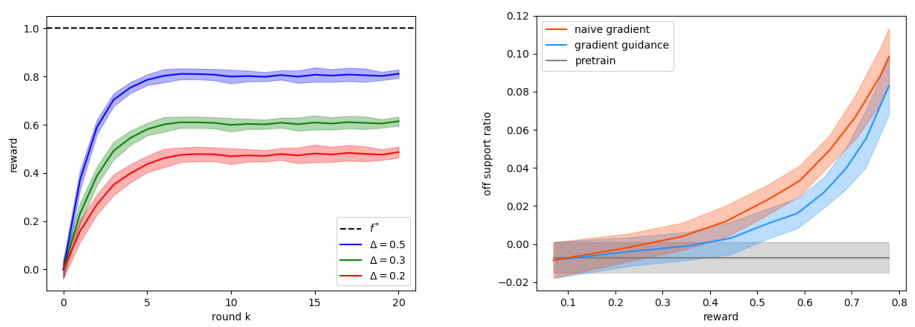

The left panel shows how the reward increases and converges as the number of iterations increases, with larger guidance strength leading to higher rewards. The right panel shows generated images across iterations for different guidance strengths. The generated images transition from photorealistic to more abstract and stylized as the reward (and guidance strength) increases.

This figure shows the plot of the functions f(t), a(t), and h(t) for t ranging from 0 to 10, given that the covariance matrix ∑ is equal to the identity matrix I. These functions are related to the forward diffusion process in the paper. Specifically: * f(t) Represents the noise scheduling function used in the forward process (Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process) to progressively add noise to the data. * a(t) Represents the scaling factor that determines how much of the original signal remains at time t in the forward process. * h(t) Represents the variance of the noise added at time t in the forward process.

This figure compares the performance of two gradient guidance methods, G and Gloss, in preserving the subspace structure learned from a pre-trained model. The off/on-support ratio (roff) is used to measure how well the generated samples adhere to the subspace. The left two panels show that Gloss significantly outperforms G in this respect, maintaining samples much closer to the subspace over many iterations, for both Algorithm 1 and Algorithm 2. The right two panels provide 3D visualizations of the sample distributions, clearly showing that Gloss’s samples remain concentrated in the subspace compared to G’s samples which stray significantly outside of it.

This figure displays the convergence results of Algorithm 1 under various objective functions and parameter settings. Panels (a) and (b) show results for the quadratic objective function f1(x), with different choices for the parameter θ. Panels (c) and (d) show results for the linear objective function f2(x), with different choices for the parameter b. Across all experiments, the gradient guidance Gloss is used.

This figure shows the convergence results and the generated sample distributions of Algorithm 2 (adaptive fine-tuning) and Algorithm 1 (no adaptive fine-tuning). Panel (a) shows that Algorithm 2 successfully converges to the global optimal objective value, whereas Algorithm 1 only converges to a sub-optimal value due to regularization imposed by the pre-trained diffusion model. Panel (b) visualizes the sample distributions. As Algorithm 2 iterates, the samples spread out beyond the pre-trained data distribution, while the samples generated by Algorithm 1 stay concentrated around the data distribution.

This figure compares the performance of two gradient guidance methods, G (naive gradient) and Gloss (proposed gradient guidance), in terms of maintaining the latent structure of generated samples. The left panel shows the reward (objective function value) over training iterations for both methods, demonstrating Gloss’s superior convergence to the optimal reward. The right panel shows the off-support ratio (a measure of how much the generated samples deviate from the subspace) versus the reward. It illustrates that Gloss significantly outperforms G in preserving the subspace structure throughout the optimization process. The pre-trained model’s baseline off-support ratio is also shown for reference.

More on tables

This table shows the runtime efficiency of Algorithm 1, comparing the time to converge with and without guidance. The ’total runtime’ column provides the total time taken for the algorithm to converge, while ‘per iteration’ shows the time for a single iteration. The ’no guidance’ column provides a baseline by showing the runtime for a single inference run of the pre-trained model without applying the algorithm’s guidance.

This table shows the runtime efficiency of Algorithm 1, breaking down the total runtime into iterations and showing the per-iteration time. It also compares the total runtime to the time it takes to perform a single inference with the pre-trained model (i.e., without guidance). The ‘Simulation’ rows shows data from the numerical simulation experiments, and the ‘Image’ row represents the results from image generation experiments.

Full paper#