↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The prevailing view in linguistics and AI has long held a dichotomy between symbolic and distributed representations of language. This paper challenges that by demonstrating that large language models (LLMs) implicitly learn a geometric representation of syntax, where syntactic relationships between words are encoded as relative distances and directions in a lower dimensional subspace of their internal representations. This raises fundamental questions about the nature of language processing in LLMs and neural networks in general.

To investigate this, the authors introduce a novel ‘Polar Probe’ trained to recognize syntactic relations from both the distance and direction between word embeddings. They show that this ‘Polar Probe’ significantly outperforms the existing ‘Structural Probe’, providing much more accurate and fine-grained information about syntactic relationships. This discovery demonstrates the spontaneous emergence of a polar coordinate system for syntax in LLMs, suggesting that neural networks may intrinsically capture the geometry of language structure. This research offers a major advancement in understanding how LLMs process syntactic information.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it demonstrates that large language models implicitly learn a geometric representation of syntax, challenging the traditional view of a dichotomy between symbolic and distributed representations of language. This opens exciting avenues for understanding the inner workings of LLMs and for bridging the gap between linguistic theory and neural network architectures. It also provides a new framework for probing syntactic information in LLMs, opening new opportunities for model analysis and improvement.

Visual Insights#

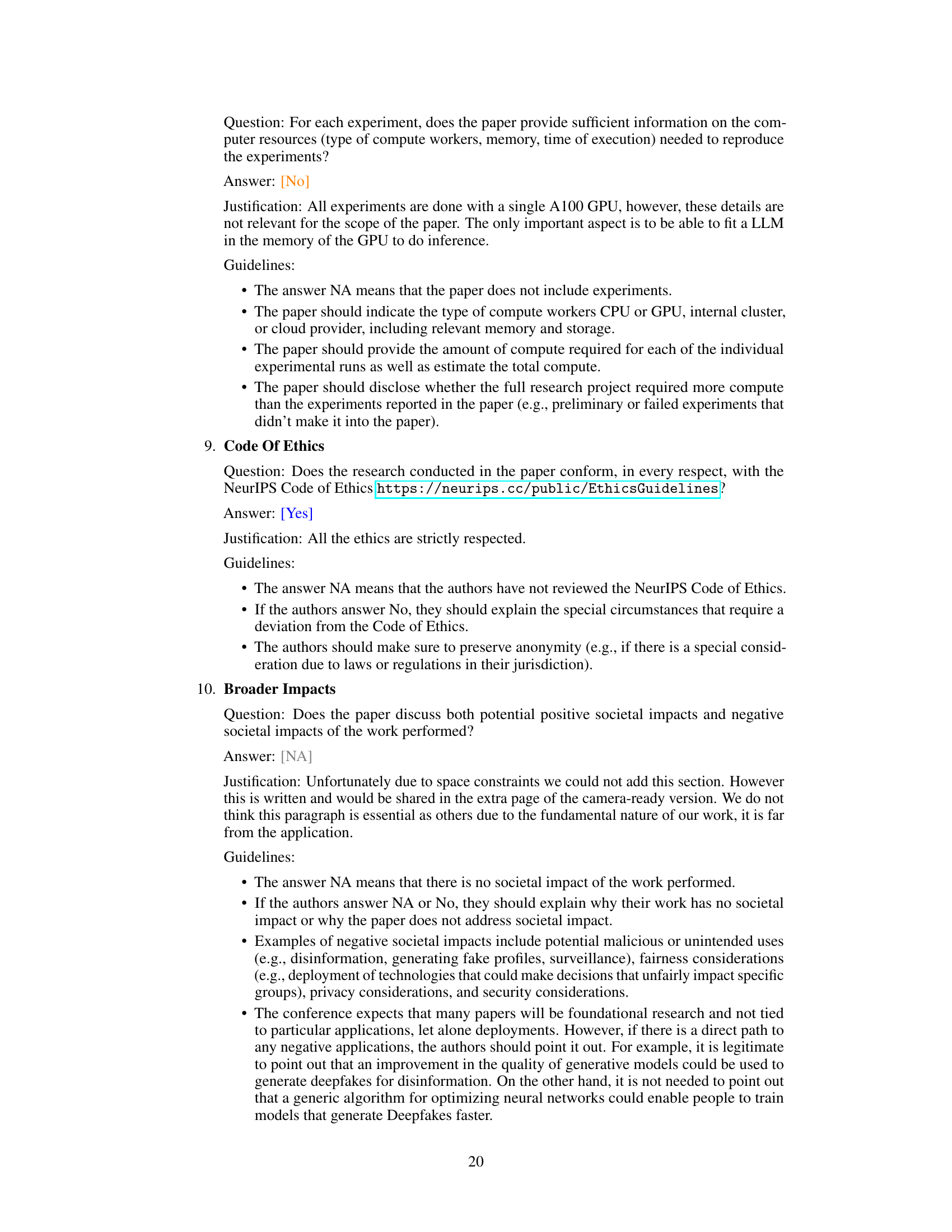

This figure illustrates the difference between dependency trees as represented in linguistics and neural networks. Panel A shows an unlabeled undirected graph. Panel B depicts labeled directed dependency trees. Panel C shows how the Structural Probe represents syntactic relations based on distance between word embeddings. Panel D illustrates the Polar Probe’s novel approach to represent syntactic relations using both distance and direction in a polar coordinate system.

In-depth insights#

Polar Syntax Probe#

A Polar Syntax Probe, as the name suggests, would be a method designed to analyze sentence structure in a more nuanced and comprehensive way than traditional methods. It leverages a polar coordinate system to represent syntactic relationships, capturing both the distance and direction between words in a sentence’s embedding space. This approach addresses limitations of existing probes, which often only capture distance, neglecting crucial directional information inherent in syntactic relations (e.g., subject-verb, verb-object). By using both distance and angle, a Polar Syntax Probe could potentially distinguish between different types of syntactic dependencies more accurately, offering richer insights into a language model’s understanding of syntax. The advantage lies in representing the hierarchical and directional aspects of syntax explicitly. This would enhance our understanding of how LLMs internalize syntax and could lead to improved techniques for analyzing and potentially correcting syntactic errors.

LLM Syntax Geometry#

The concept of “LLM Syntax Geometry” proposes that the syntactic structure of language, traditionally represented by symbolic trees, is encoded geometrically within the high-dimensional activation spaces of large language models (LLMs). This geometry is not explicitly programmed but rather emerges spontaneously from the LLM’s training on vast amounts of text data. The hypothesis suggests that syntactically related words are positioned in close proximity within this activation space, with their relative distances and directions reflecting the hierarchical and directional relationships within the syntactic tree. Investigating this geometry could provide valuable insights into how LLMs process and understand language, moving beyond simple distance metrics to explore a richer, more nuanced representation of syntactic information. This approach offers a potential bridge between symbolic and connectionist views of language processing, revealing how the vector-based representations of LLMs can capture abstract symbolic structures.

Beyond Structural Probes#

The heading ‘Beyond Structural Probes’ suggests an exploration of limitations and extensions to the Structural Probe method in natural language processing. Structural Probes focus on measuring syntactic relationships by analyzing distances between word embeddings, but this approach is limited. It primarily indicates the presence, rather than the type or direction, of syntactic connections. A key area of exploration would be developing methods that capture the rich directional and relational aspects of syntax to create a more comprehensive syntactic representation. This might involve examining vector orientations, angles, or other geometric features to differentiate between various syntactic relationships. Furthermore, research could investigate alternative methods beyond Euclidean distance to better model syntactic structures, such as hyperbolic space or graph neural networks. Finally, ‘Beyond Structural Probes’ could also delve into the application of these advanced methods to improve tasks like syntactic parsing, machine translation, or question answering, demonstrating their practical impact beyond simple distance measures.

Syntactic Dimensionality#

The concept of “Syntactic Dimensionality” in the context of large language models (LLMs) refers to the minimum number of dimensions needed to effectively capture the full complexity of syntactic structures within the model’s internal representations. A lower dimensionality implies that the model efficiently encodes syntactic information in a compact space. This is a crucial question because it speaks to the efficiency and sophistication of LLMs’ syntactic understanding. A high dimensionality might suggest redundant or inefficient encoding, while a low dimensionality could indicate a more elegant and parsimonious representation. Investigating this dimensionality is essential for understanding how LLMs learn and represent syntax and may inform the design of more efficient and powerful models. It also has implications for comparing the syntactic capabilities of different LLMs and could even provide insights into the neural mechanisms underlying human language processing.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on polar coordinate representation of syntax in LLMs are plentiful. Extending the Polar Probe to other languages and linguistic frameworks beyond dependency grammar (e.g., phrase structure grammars) is crucial to assess the universality and limitations of this geometric representation. Investigating the impact of different model architectures and training paradigms on the emergence of this polar coordinate system is important, as is exploring whether similar structures exist in other modalities beyond language. A particularly exciting avenue is exploring the neural basis of syntax in biological brains by relating this model to neuroimaging data. This would provide critical insights into the relationship between computational models and human cognition. Finally, developing unsupervised methods for discovering and analyzing this structure would significantly advance the field and broaden applicability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

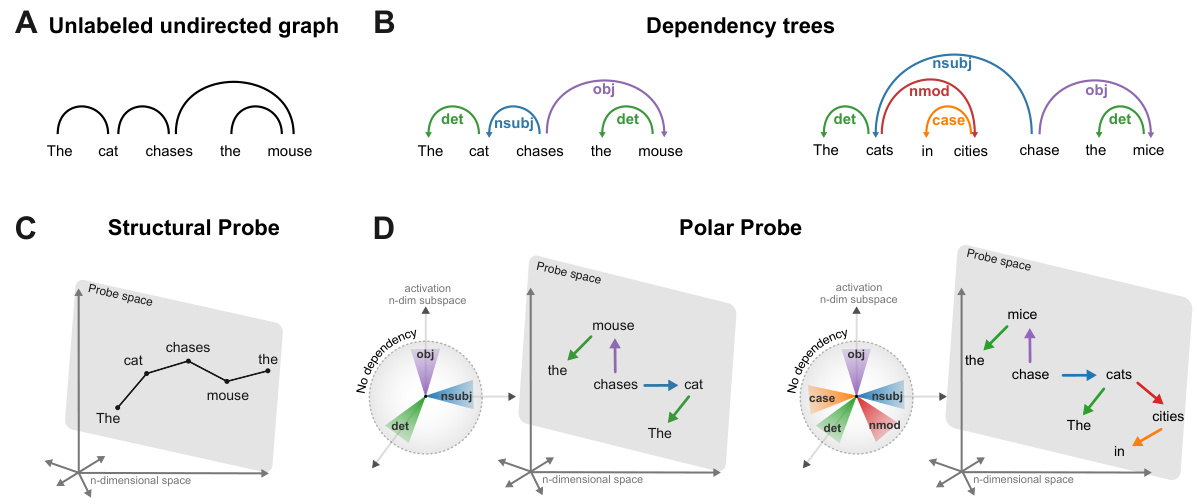

This figure shows that the Polar Probe effectively identifies dependency types. Panel A presents a PCA visualization, where edges (syntactic relations between words) are colored according to their dependency type and exhibit systematic directional patterns in the Polar Probe’s representation space. Panel B displays the AUC (Area Under the Curve) and balanced accuracy scores evaluating the probe’s performance in classifying dependency types. Finally, Panel C depicts pairwise cosine similarity matrices demonstrating that the Polar Probe better distinguishes between dependency types compared to both the Structural Probe and a baseline with no probe.

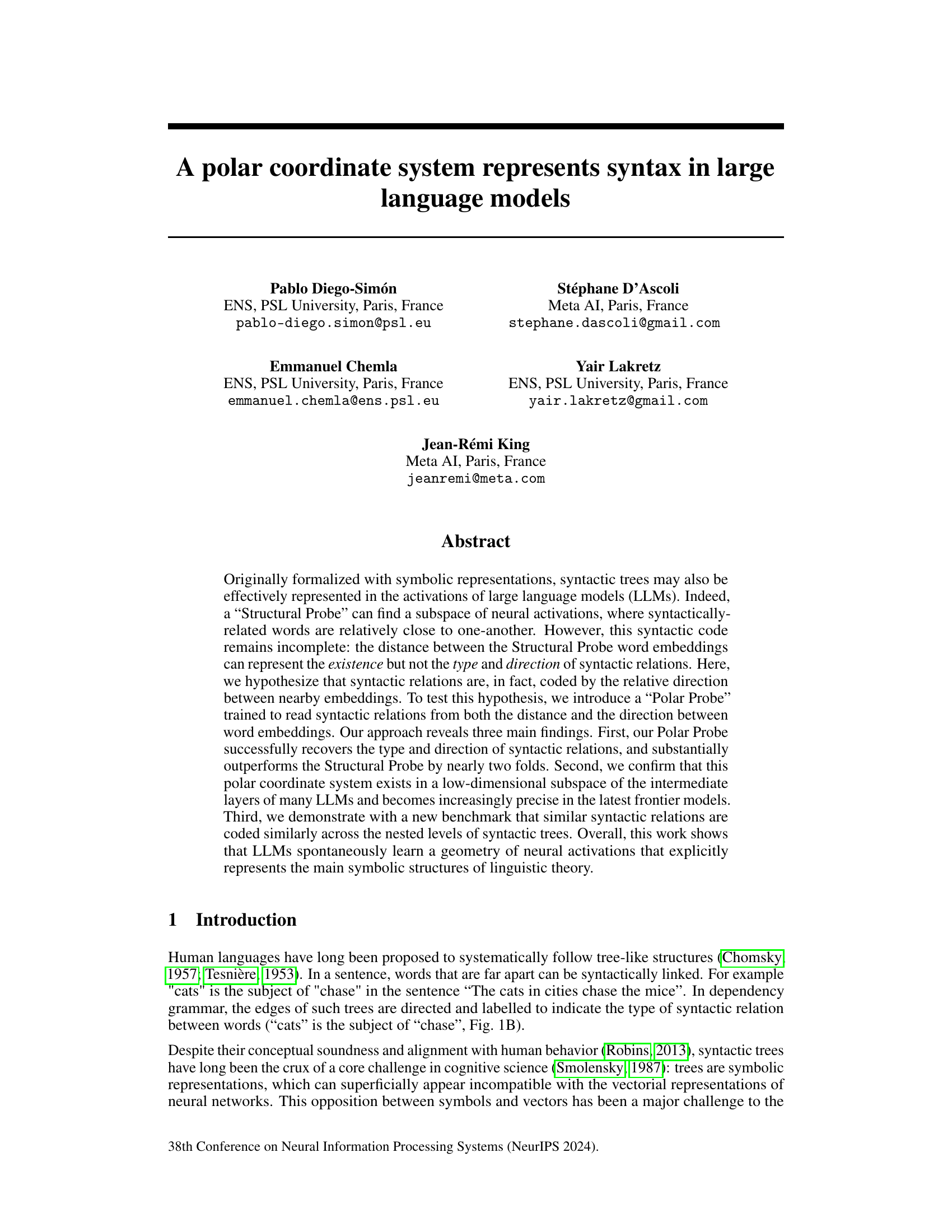

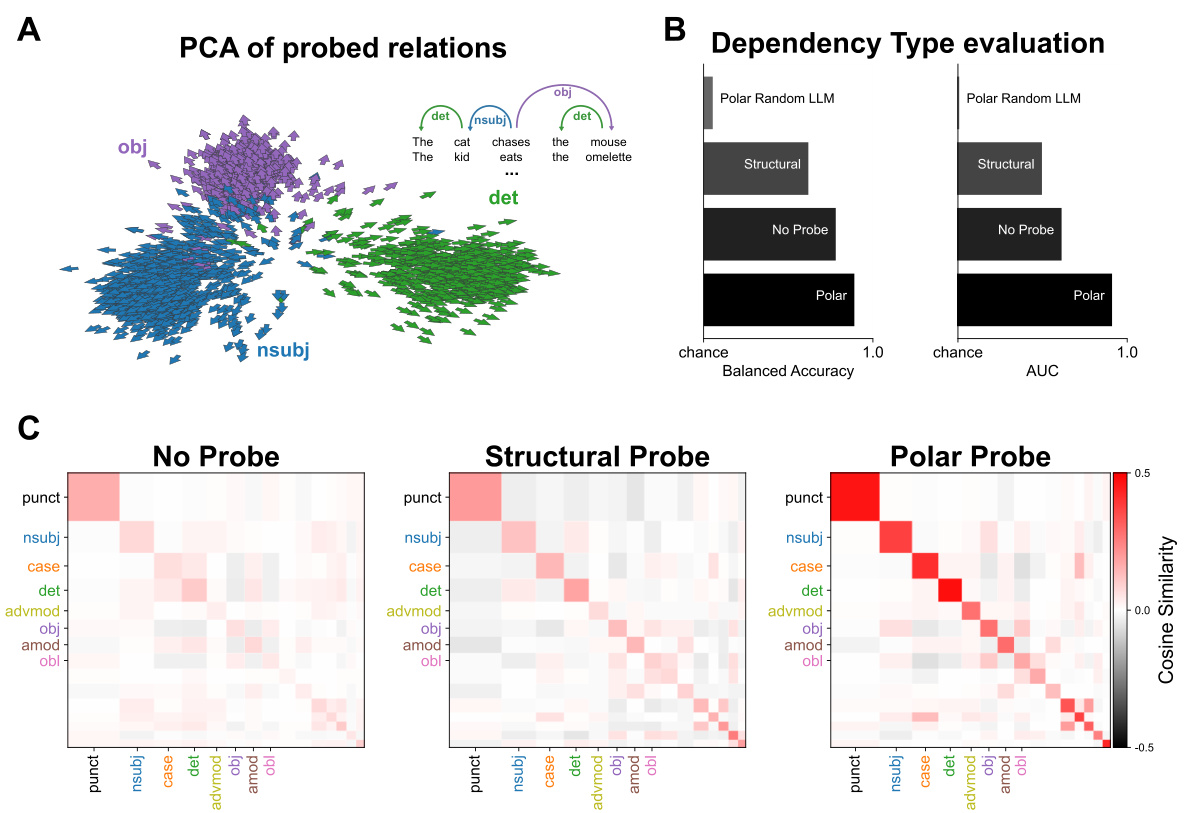

This figure shows a comparison of the performance of three different probes (Polar Probe, Polar Probe with a random language model, and Structural Probe) across different layers of a language model. The three plots show the results for dependency existence (UUAS), dependency type accuracy, and a combined score (LAS). The Polar Probe consistently outperforms the other methods, particularly in predicting the type of dependency relationships. The best performance for all probes is generally observed around layer 16.

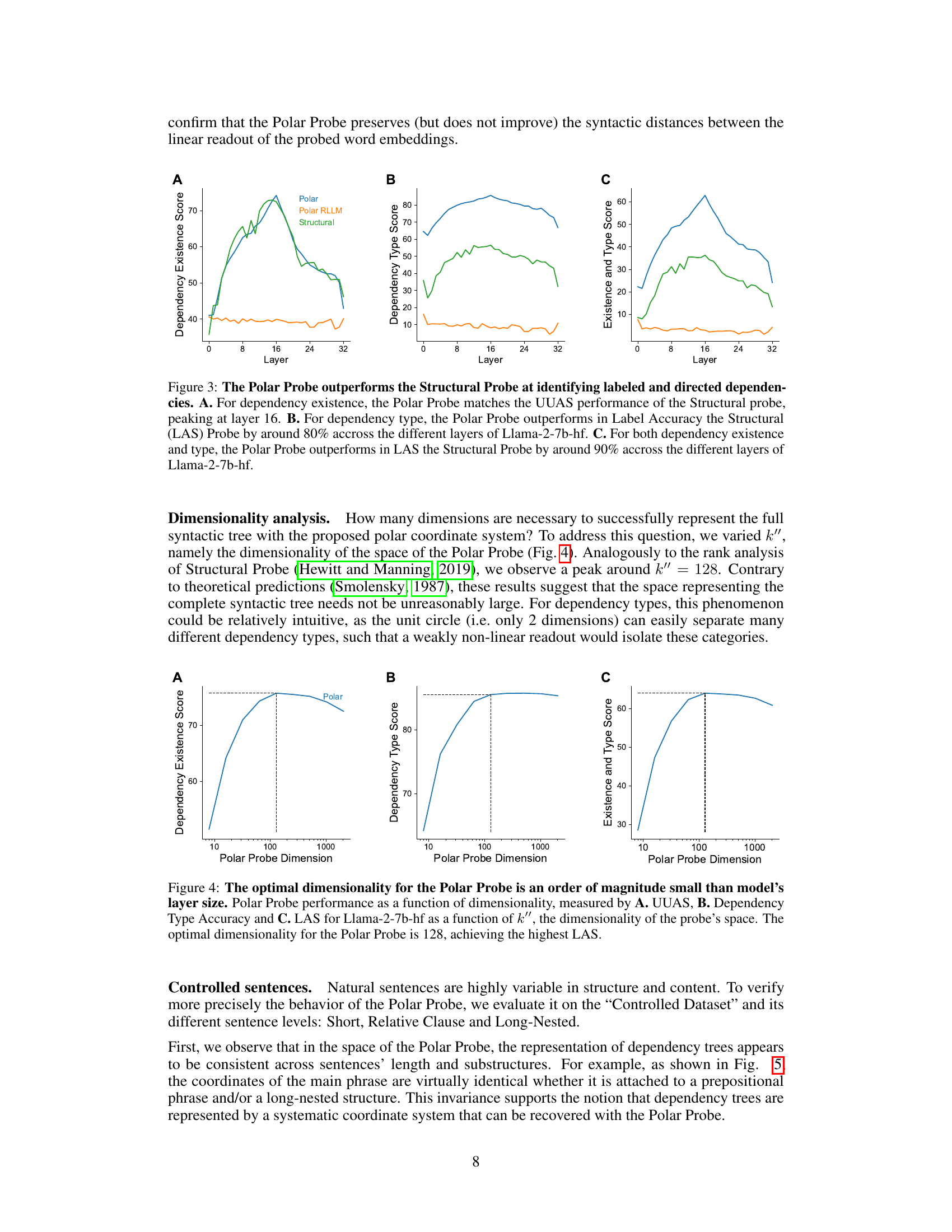

This figure displays the performance of the Polar Probe model in relation to its dimensionality (k’). It shows three subplots: A) Dependency Existence Score (UUAS), B) Dependency Type Score (Accuracy), and C) Combined Existence and Type Score (LAS). Each subplot illustrates how the respective metric changes as the dimensionality (k’) of the Polar Probe increases. The optimal dimensionality for the model appears to be around 128, beyond which performance improvement plateaus.

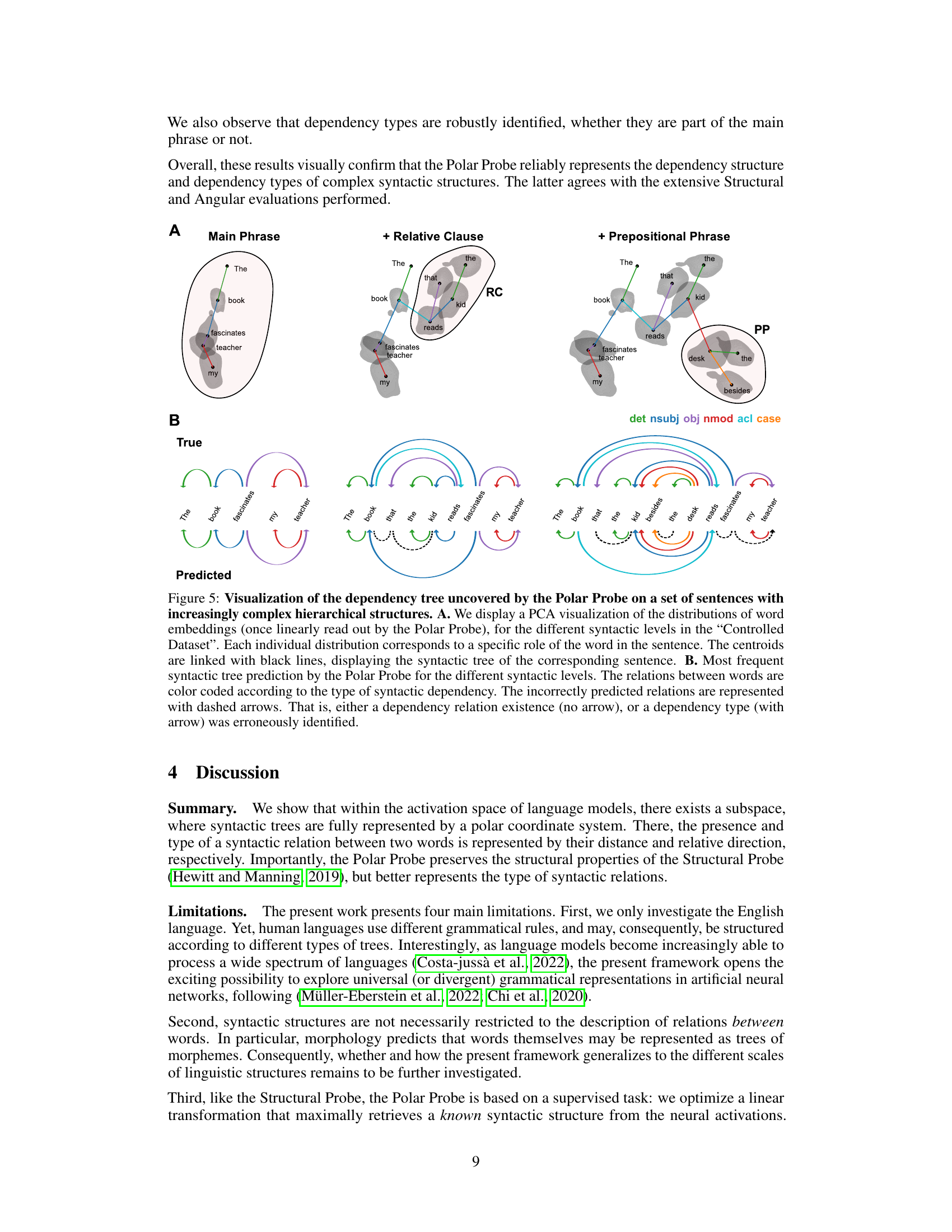

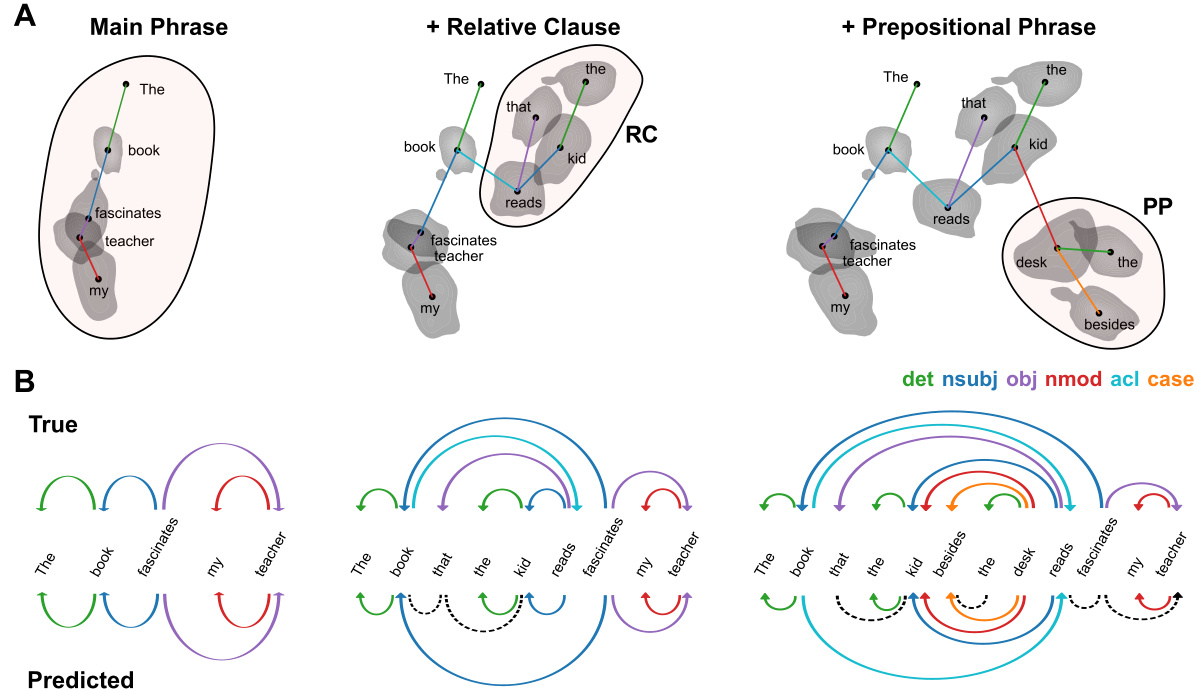

This figure visualizes how the Polar Probe represents dependency trees in sentences with varying complexity (short, relative clause, and long-nested structures). Panel A shows PCA visualizations of word embeddings, grouped by their syntactic role within each sentence type, highlighting how similar roles cluster together. Panel B compares the true dependency trees against those predicted by the Polar Probe, color-coding relationships by type and using dashed lines to indicate incorrect predictions.

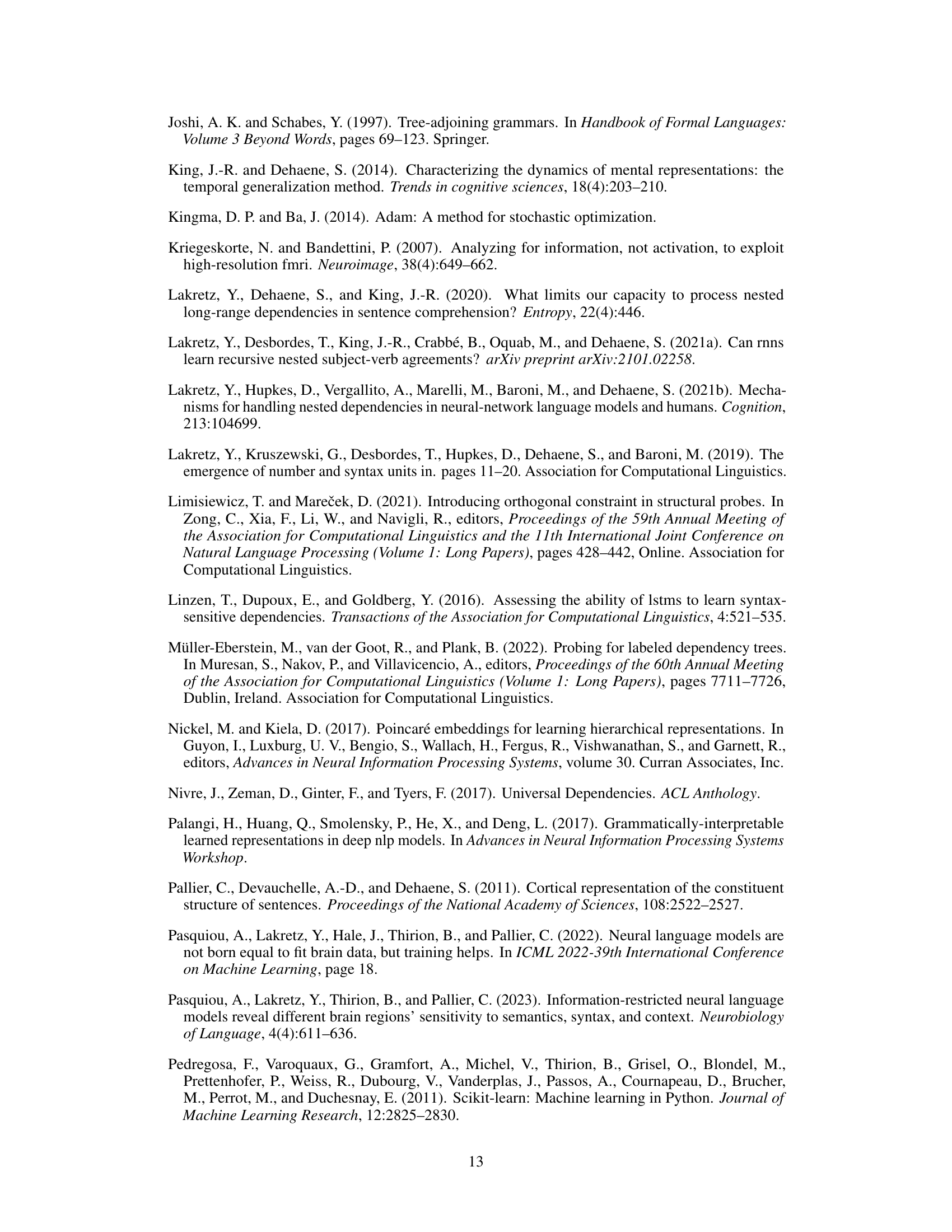

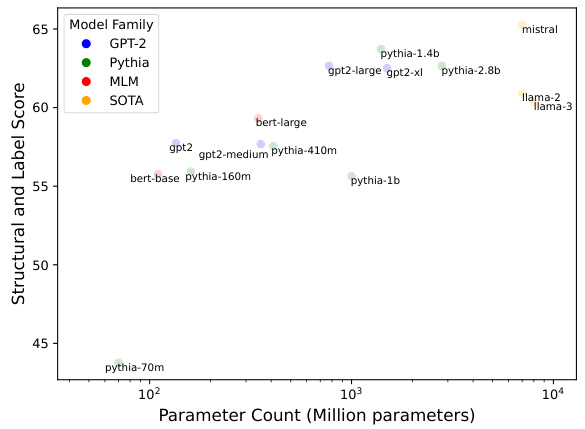

This figure displays a scatter plot showing the relationship between the performance of the Polar Probe (measured by the Structural and Label Score) and the number of parameters in various Language Models. Different colors represent different families of Language Models (GPT-2, Pythia, MLM, Llama, and Mistral). The plot shows that as the parameter count increases, the Structural and Label Score tends to increase. The plot visually demonstrates that within families, larger language models perform better on average. It helps to compare the performance across different Language Model architectures.

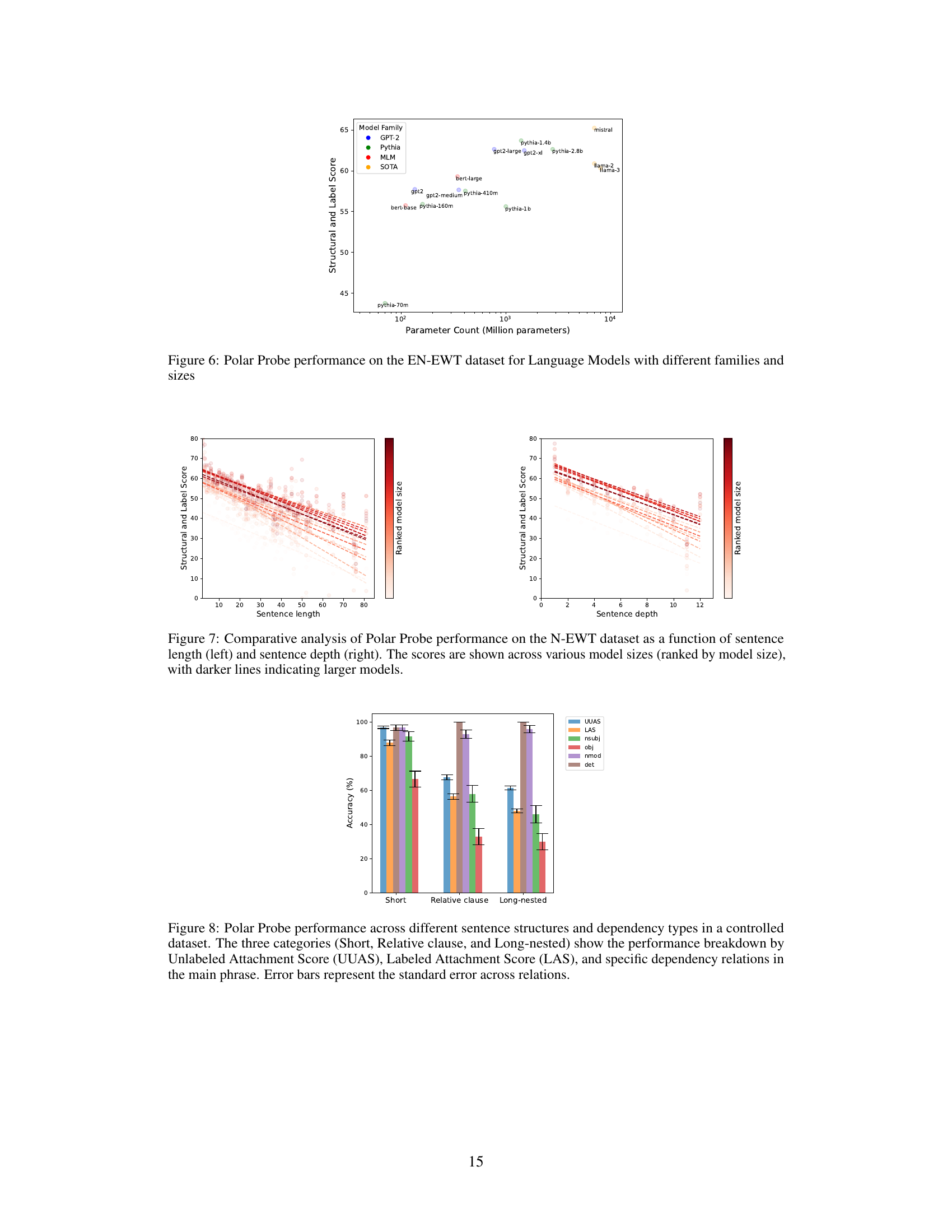

This figure shows a comparative analysis of the Polar Probe’s performance on the English Web Treebank (EWT) dataset. The left panel displays the relationship between sentence length and the Polar Probe’s performance, while the right panel shows the relationship between sentence depth and the probe’s performance. In both panels, the scores are shown across different model sizes, with larger models shown as darker lines. The results show that the Polar Probe’s performance is affected by both sentence length and depth, with longer and deeper sentences resulting in lower scores. The performance also improves with larger model sizes.

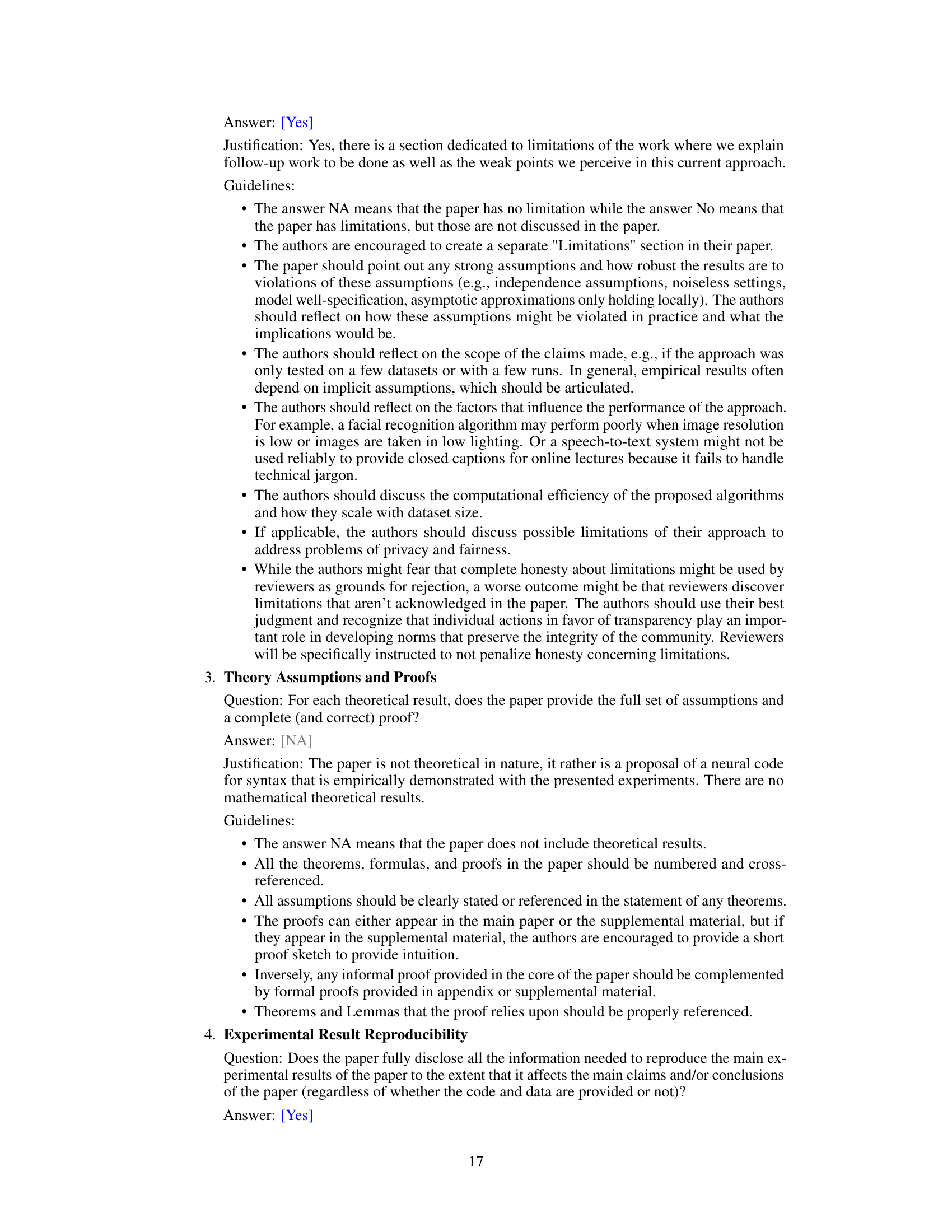

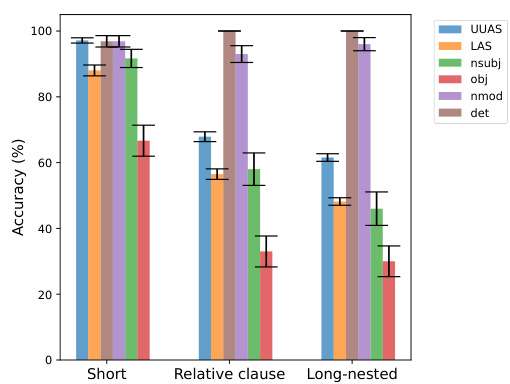

This figure displays the Polar Probe’s performance on a controlled dataset with varying sentence complexity (short, relative clause, long-nested). It shows the accuracy (with error bars) of predicting dependency tree structures (UUAS, LAS) and specific dependency types (nsubj, obj, nmod, det) for each sentence type. The results highlight the probe’s ability to handle increasingly complex syntactic structures.

Full paper#