↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world problems involve sampling from complex probability distributions that are not log-concave, posing significant challenges for existing sampling algorithms. These algorithms often struggle with high-dimensional data, multimodal distributions (distributions with multiple peaks), and scenarios with high energy barriers between modes. This leads to slow convergence and inaccurate results.

This paper introduces Zeroth-Order Diffusion Monte Carlo (ZOD-MC), a novel sampling method designed to address these limitations. ZOD-MC cleverly leverages the denoising diffusion process, a technique used in generative modeling, and approximates the score function using Monte Carlo methods, requiring only zeroth-order queries (function evaluations without gradients). The researchers demonstrate its effectiveness through theoretical analysis and experiments, showing superior performance compared to existing methods particularly for lower-dimensional distributions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on sampling algorithms, particularly those dealing with complex, non-log-concave distributions. It offers a novel, efficient sampling method and valuable theoretical insights, paving the way for advancements in various fields relying on effective sampling techniques. The work addresses the limitations of existing methods, especially in high-dimensional spaces and multimodal distributions, providing a significant step forward in tackling challenging sampling problems.

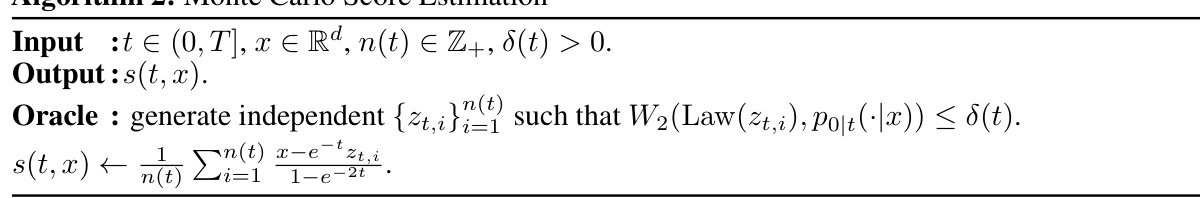

Visual Insights#

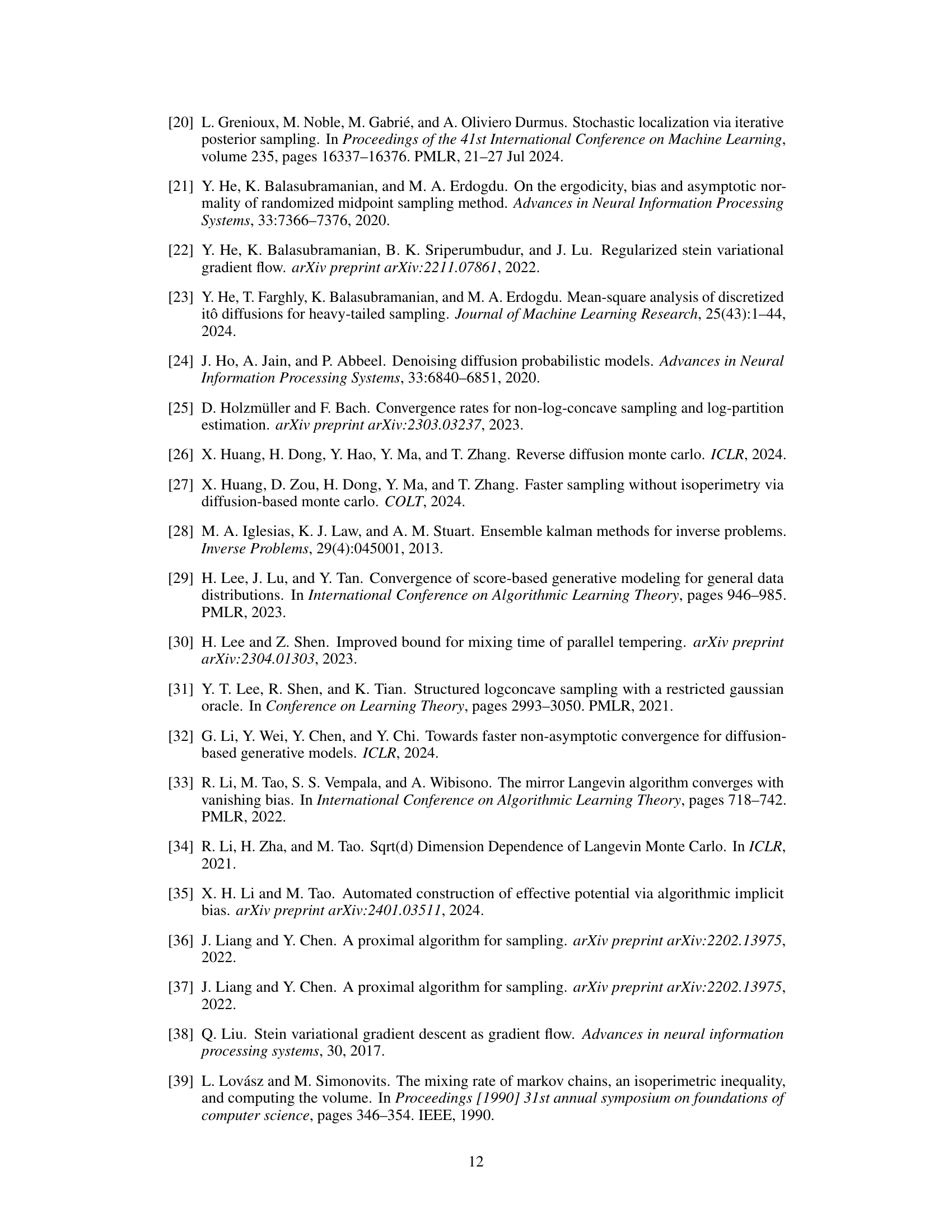

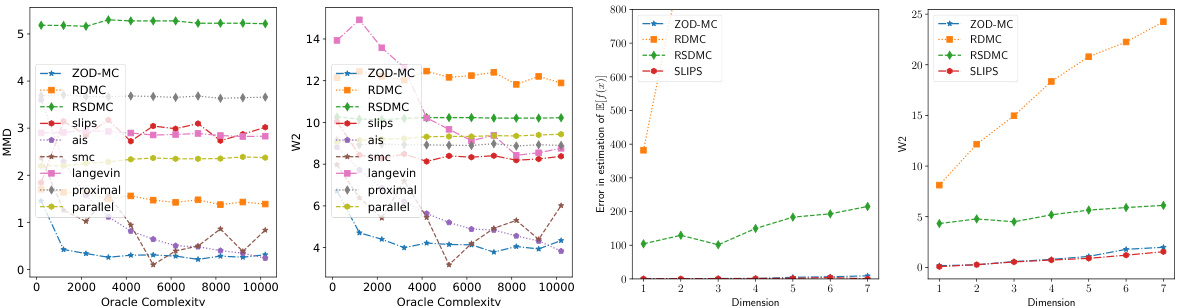

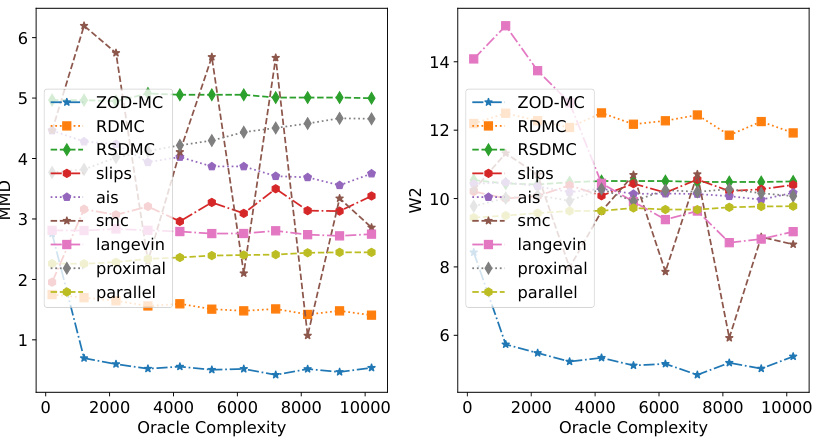

This figure compares the performance of various sampling methods on a Gaussian Mixture model. Specifically, it shows the sampling accuracy (measured by MMD and W2 metrics) against oracle complexity. The left subplot demonstrates the lower error achieved by ZOD-MC compared to other methods, even with less oracle complexity. The right subplot illustrates the scalability of different methods across different dimensions, showing ZOD-MC’s better performance in lower dimensions.

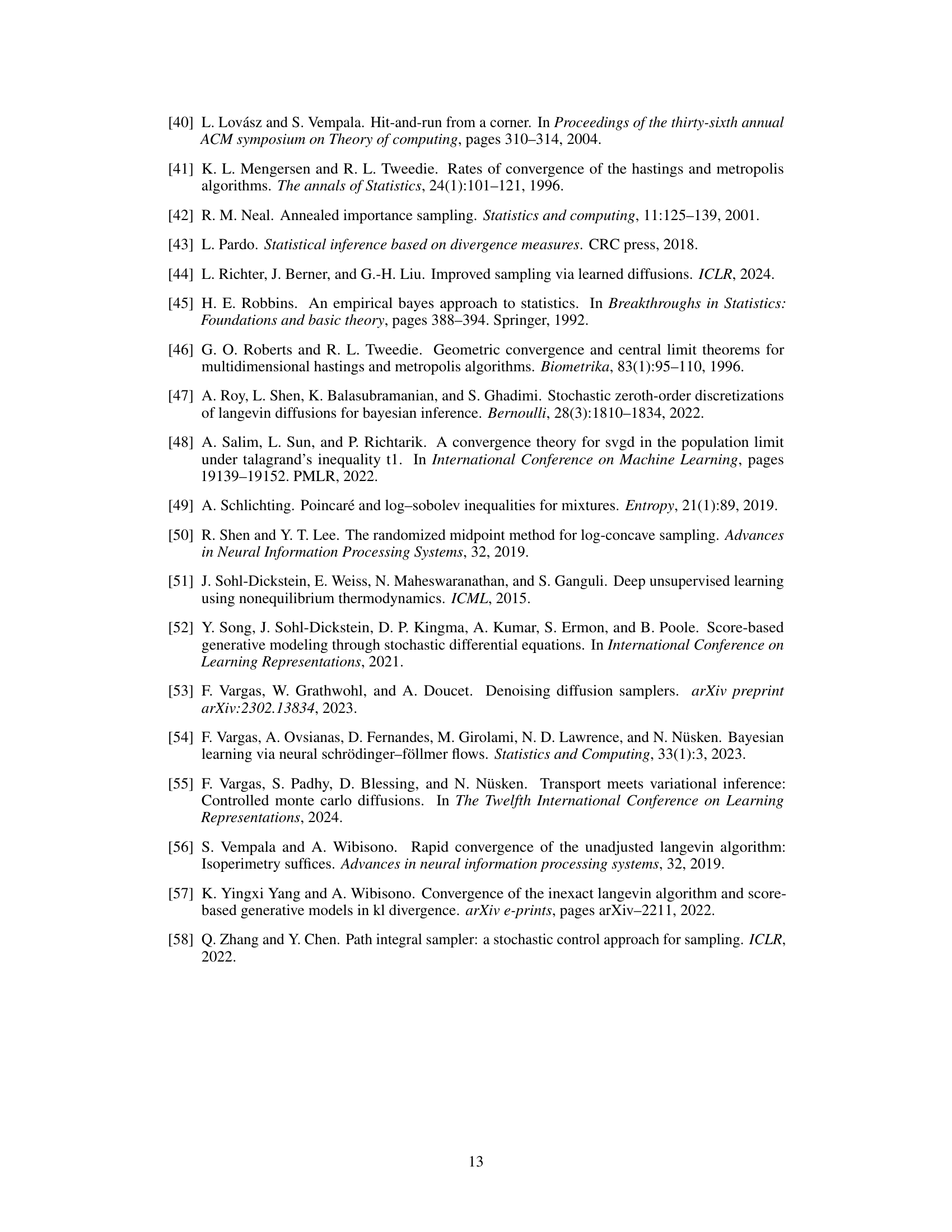

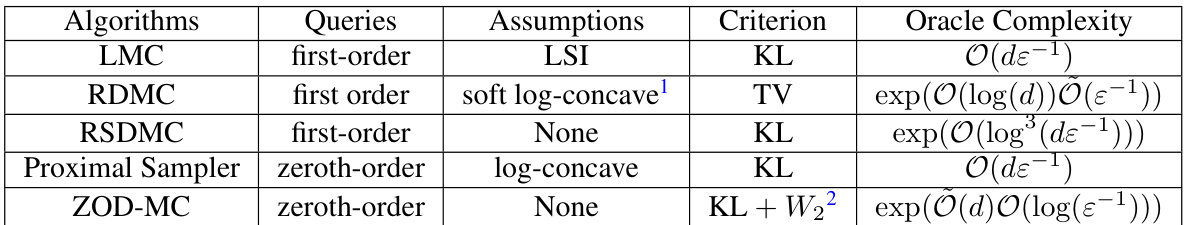

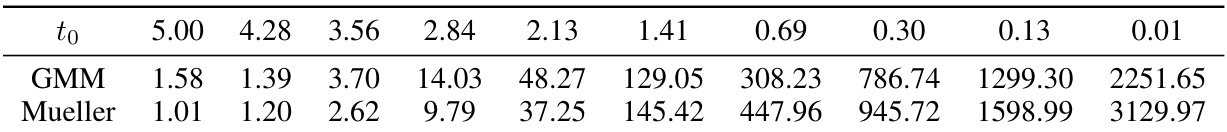

This table compares the zeroth-order sampling algorithm ZOD-MC with several other sampling algorithms (LMC, RDMC, RSDMC, and Proximal Sampler). The comparison is made based on several factors such as the type of queries used (first-order vs. zeroth-order), assumptions on the target distribution (e.g., log-concavity), the criterion for accuracy (KL divergence, Total Variation distance, Wasserstein-2 distance), and the oracle complexity. The results suggest that ZOD-MC is more efficient for low-dimensional distributions when isoperimetric assumptions do not hold.

In-depth insights#

DDMC Framework#

The DDMC framework, as described in the research paper, provides a novel approach to sampling from non-log-concave distributions by simulating a denoising diffusion process. The core idea is to leverage the ability of diffusion models to sample effectively from complex, multi-modal distributions. This is achieved by approximating the score function of the target distribution using a Monte Carlo estimator. DDMC’s strength lies in its ability to handle high barriers between modes and discontinuities in the potential function. Unlike many existing methods, it does not rely on strong assumptions such as log-concavity or isoperimetric inequalities. However, the DDMC framework is an oracle-based meta-algorithm, meaning it relies on an external oracle that provides samples from a specific conditional distribution. Therefore, a key component of the framework is the implementation of this oracle using efficient sampling techniques, which is crucial for practical applications. The paper further explores the implementation of the oracle via rejection sampling and analyses the convergence and query complexity of the resulting algorithm (ZOD-MC). A significant contribution lies in providing non-asymptotic guarantees for the performance of DDMC, demonstrating its efficiency and robustness. Despite some limitations, particularly regarding dimension dependence, DDMC opens up new avenues for tackling challenging sampling problems that have traditionally been difficult to address.

ZOD-MC Algorithm#

The ZOD-MC algorithm, a novel zeroth-order sampling method, tackles the challenge of sampling from non-log-concave distributions using only unnormalized density queries. Unlike first-order methods requiring gradient calculations, ZOD-MC leverages denoising diffusion processes, approximating the score function via Monte Carlo estimation based on rejection sampling. This clever approach makes ZOD-MC computationally efficient, especially in lower dimensions, and robust to multimodality and discontinuities often hindering other samplers. The theoretical analysis establishes an inverse polynomial dependence on sampling accuracy, despite still facing the curse of dimensionality. ZOD-MC’s performance surpasses state-of-the-art samplers, particularly in low-dimensional scenarios with complex potential landscapes, demonstrating the practical advantages of its zeroth-order approach.

Convergence Analysis#

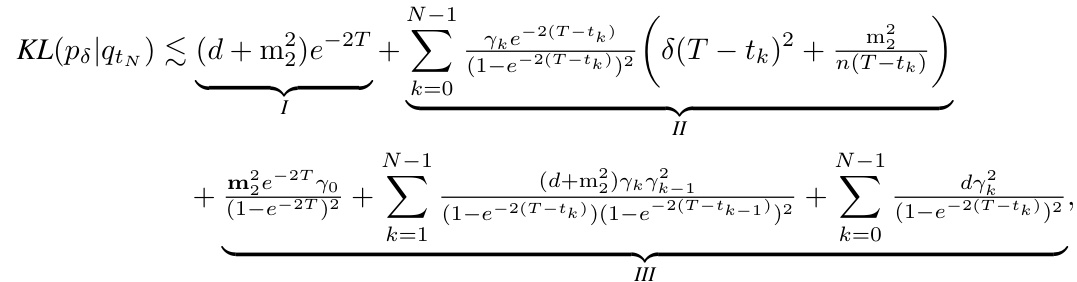

A rigorous convergence analysis is crucial for establishing the reliability and efficiency of any sampling algorithm. This analysis typically involves proving bounds on the distance between the algorithm’s output distribution and the target distribution, often using metrics like Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence or Wasserstein distance. The convergence rate, typically expressed as a function of the number of iterations or computational resources, is a key indicator of the algorithm’s performance. For high-dimensional problems, demonstrating polynomial dependence on the dimension is highly desirable, avoiding the “curse of dimensionality.” The analysis might also consider the impact of noise or approximation in the algorithm, providing bounds that reflect such inaccuracies. Establishing a framework for convergence analysis, which handles general target distributions (not necessarily log-concave or satisfying isoperimetric inequalities), would be a significant contribution. Such a framework could reveal the algorithm’s behavior in diverse scenarios and provide insights into the optimal parameter choices and trade-offs between accuracy and computational efficiency. The convergence analysis could also explore the algorithm’s robustness to higher barriers between modes or discontinuities in non-convex potential, demonstrating its practical applicability to complex, real-world problems.

Complexity Bounds#

Analyzing complexity bounds in a research paper requires a nuanced understanding of the problem’s characteristics and the chosen algorithm. Tight bounds are ideal, providing precise estimations of resource consumption, but are often difficult to achieve. Loose bounds, while less precise, can still offer valuable insights, especially when tight bounds are intractable. The type of complexity considered (time, space, query) is crucial, as different algorithms may exhibit diverse performance across these metrics. Dimensionality frequently plays a significant role, with many algorithms suffering from the ‘curse of dimensionality,’ where complexity increases exponentially with the number of dimensions. The accuracy of the desired output is also a key factor; higher accuracy generally requires more resources. Assumptions made during analysis (e.g., log-concavity, smoothness) heavily impact the derived bounds. Finally, a thorough comparison of the obtained bounds to those of existing methods is essential, placing the results within the broader context of the field and highlighting unique contributions or limitations.

Experimental Results#

The experimental results section of a research paper is crucial for validating the claims and hypotheses presented. A strong results section will include a clear presentation of the data, appropriate visualizations such as graphs and tables, and a comprehensive discussion of the findings. Statistical significance should be explicitly stated and any limitations or potential biases should be acknowledged. The results should be compared to those of previous studies or relevant baselines to show improvement or novelty. A thoughtful analysis of the findings is necessary to interpret the results within the broader context of the research field. The discussion should connect back to the paper’s introduction and clearly demonstrate whether the hypotheses were supported. Reproducibility of the experiments is vital. The methods section should provide enough detail for another researcher to replicate the study. The paper should also provide information about the computational resources used. Overall, the experimental results section should leave a reader convinced of the study’s findings and provide new knowledge or insights within the research domain.

More visual insights#

More on figures

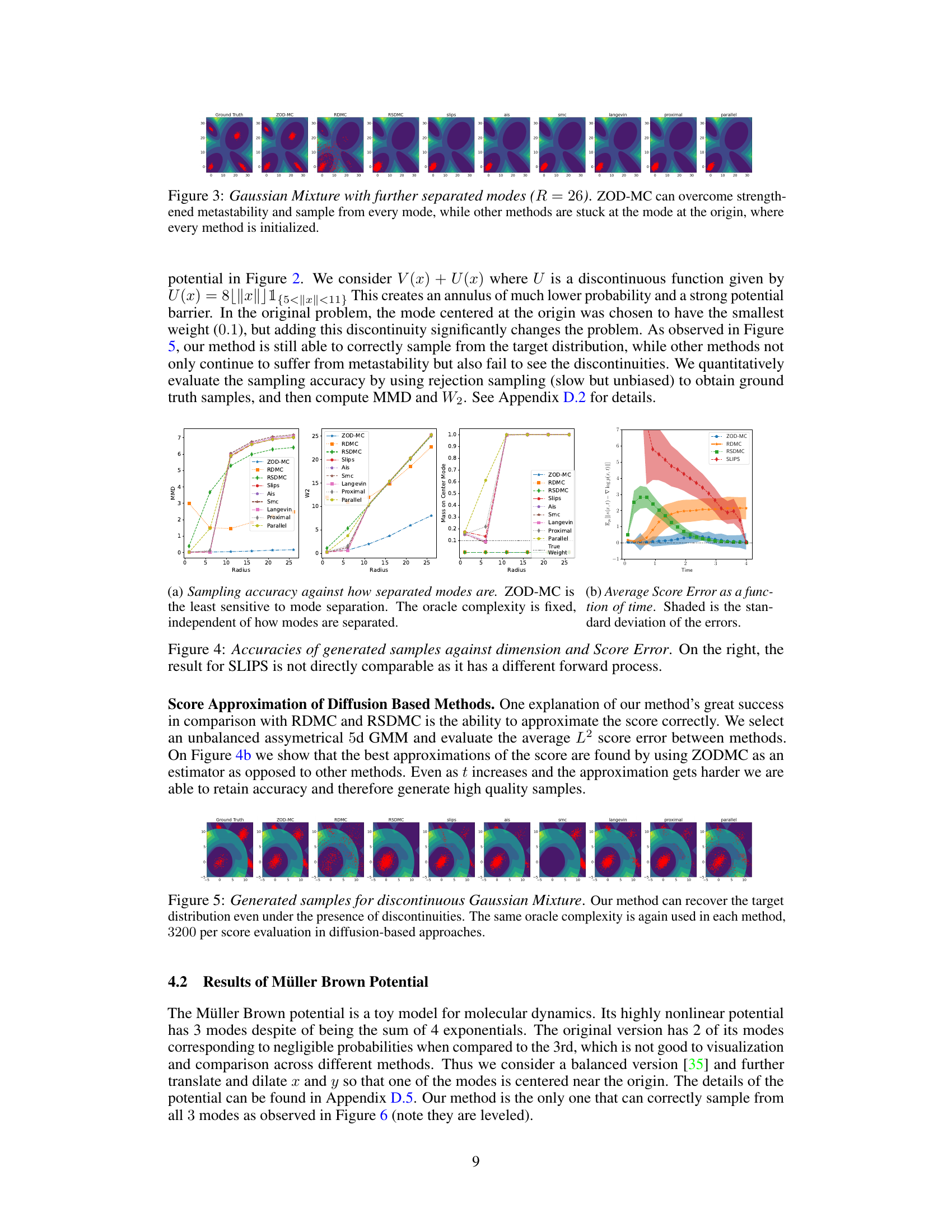

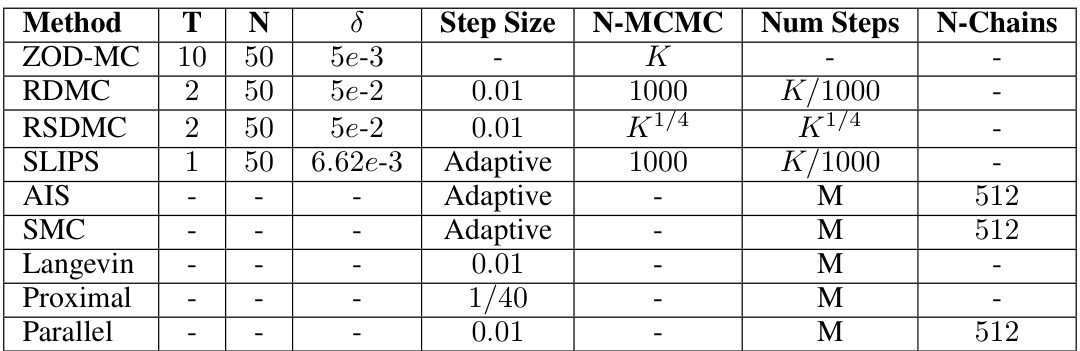

This figure presents the results of Gaussian Mixture experiments, comparing various sampling methods’ accuracies. Subfigure (a) shows sampling accuracy against oracle complexity, demonstrating ZOD-MC’s superior performance with lower errors in both MMD and W2 metrics. Subfigure (b) illustrates sampling accuracy against dimension, highlighting ZOD-MC’s better scalability compared to other diffusion-based methods.

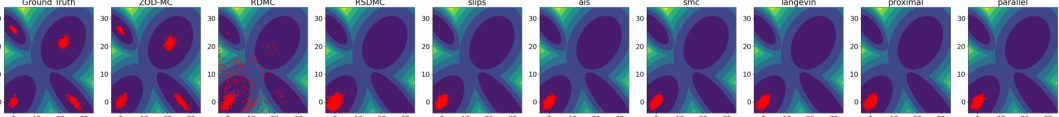

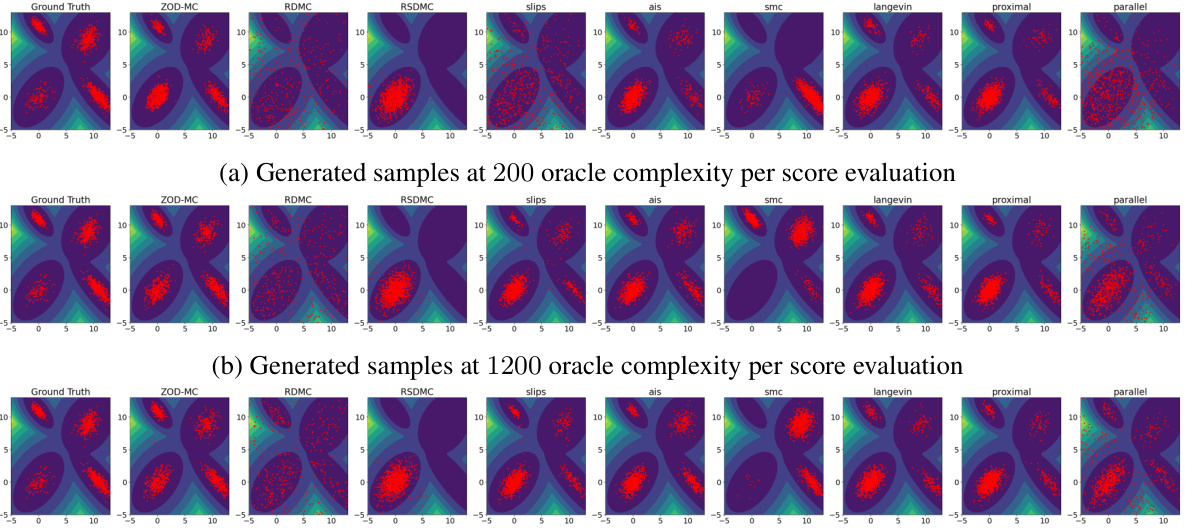

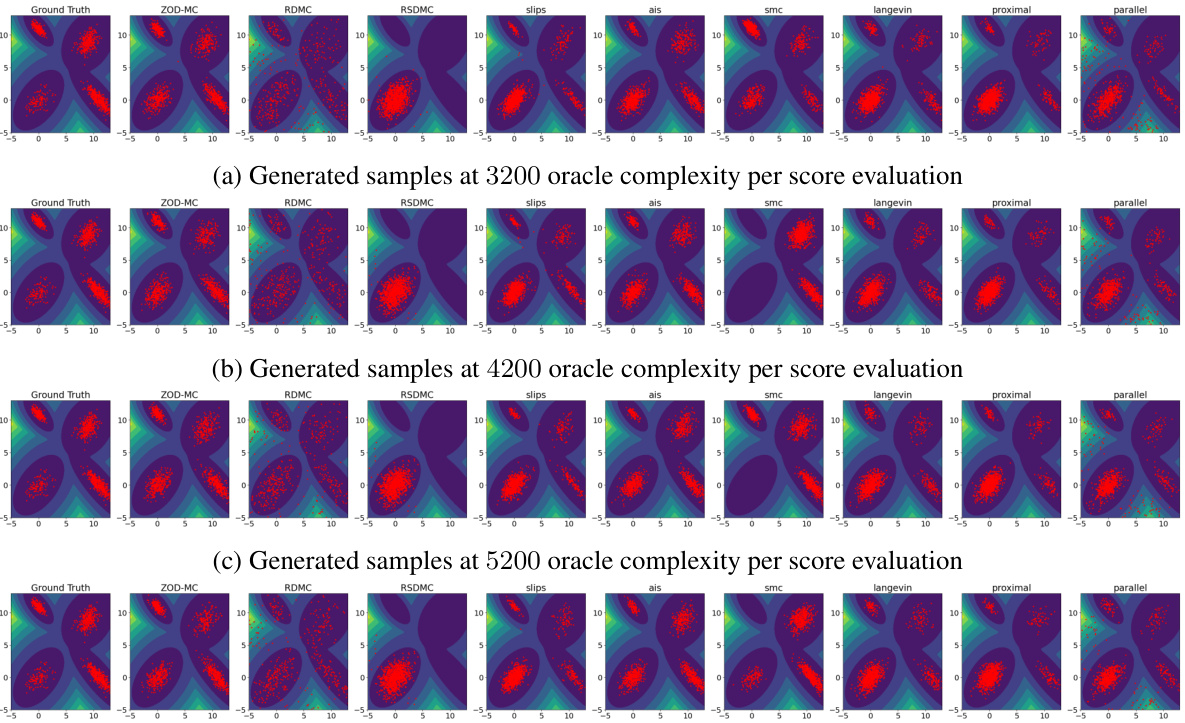

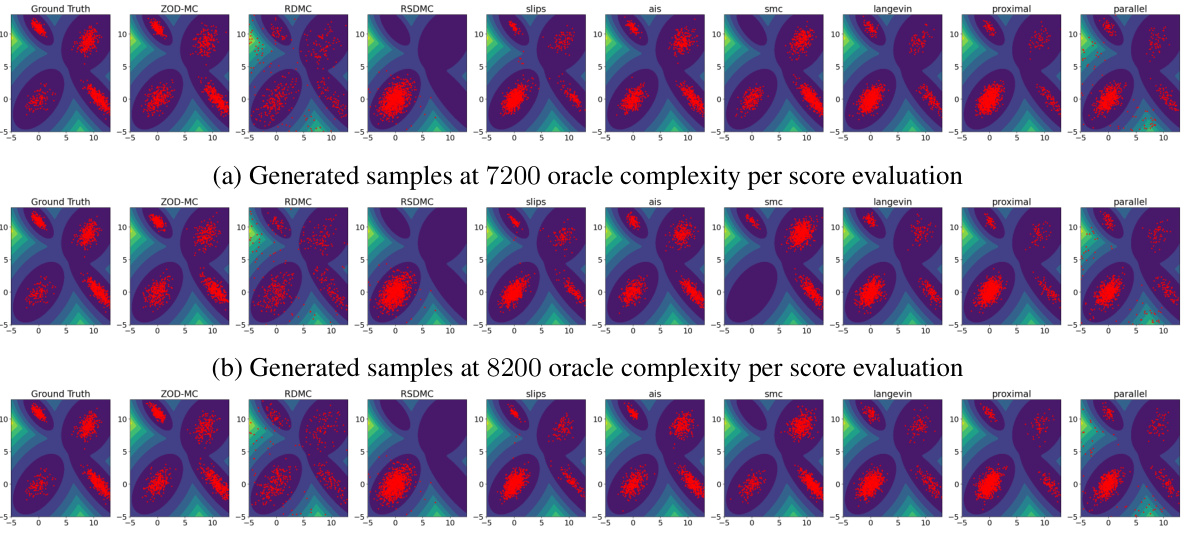

This figure compares the performance of various sampling methods on the Müller Brown potential, a challenging non-convex distribution with three modes. The plot shows the generated samples overlaid on a contour plot of the potential function. The goal is to assess each method’s ability to accurately capture the multi-modal nature of the distribution, with 1100 oracle calls used per method. ZOD-MC, the proposed method, demonstrates improved sampling performance compared to the baselines.

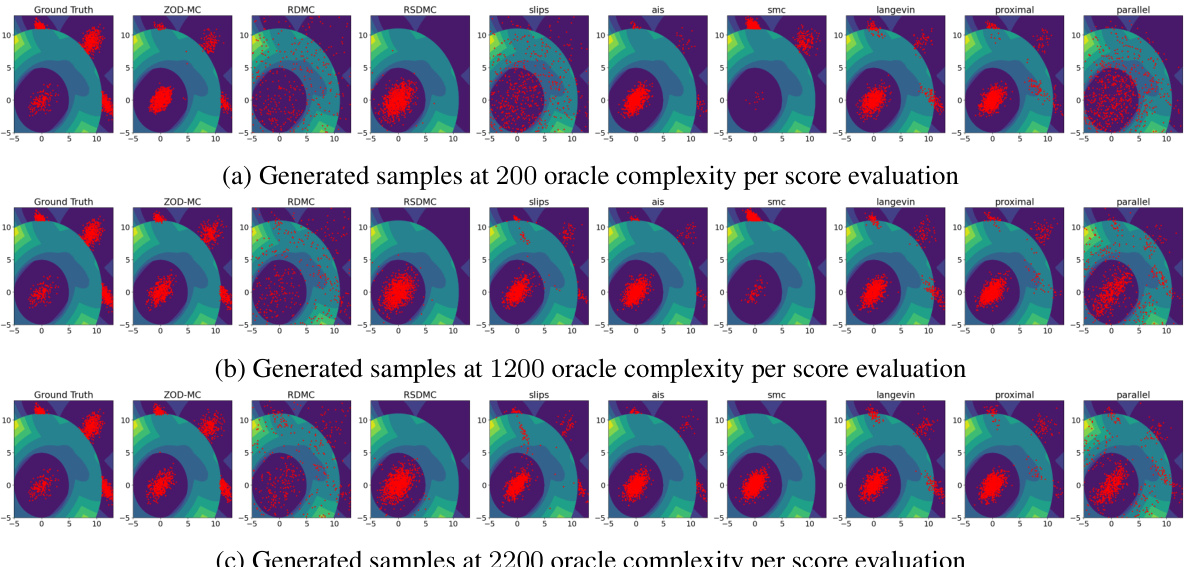

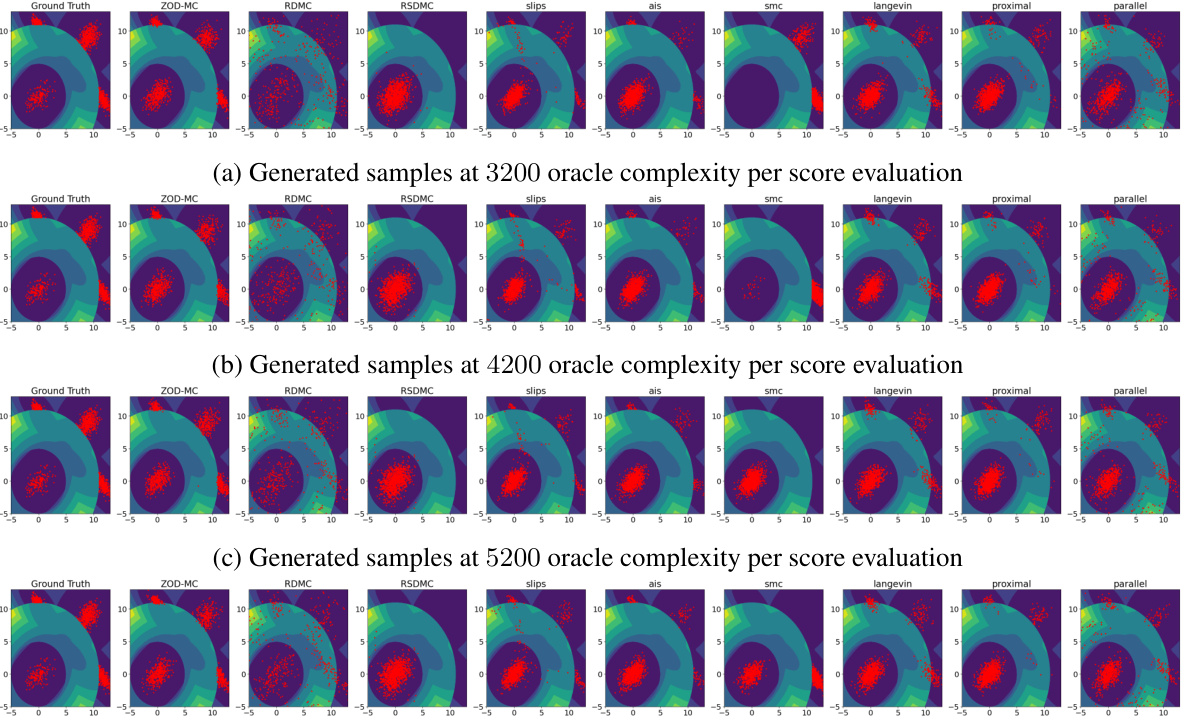

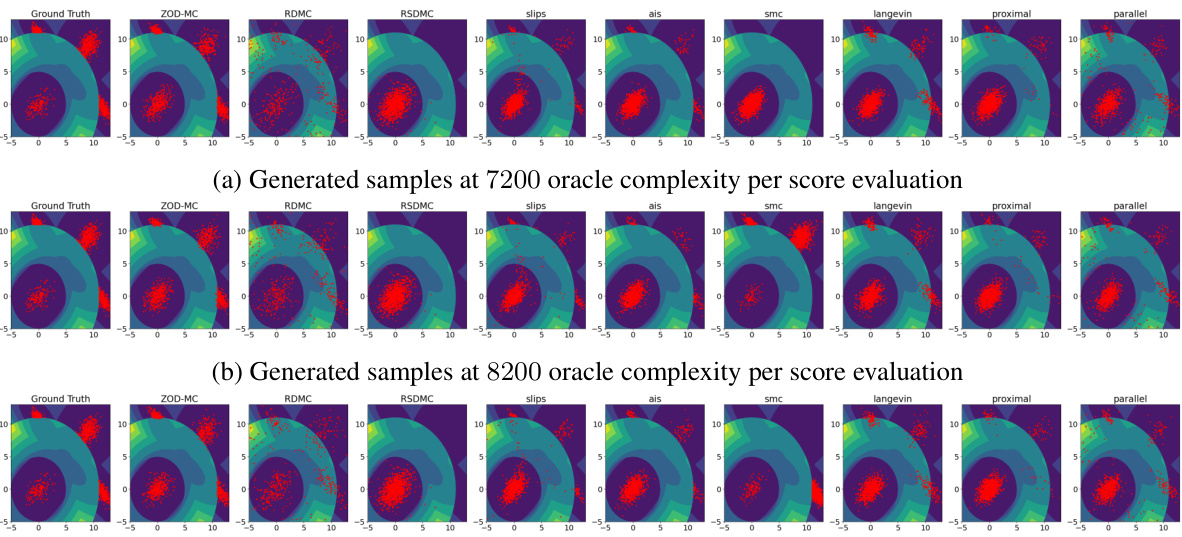

This figure compares the performance of various sampling algorithms on the Müller Brown potential, a highly non-linear and non-convex function with three modes. The generated samples are overlaid on the contour plot of the potential function. The figure visually demonstrates the ability of ZOD-MC to effectively sample from all three modes of the Müller-Brown potential, in contrast to other methods which struggle to escape local minima, showcasing its effectiveness in sampling from challenging non-convex distributions.

This figure displays the performance comparison of various sampling methods on a Gaussian Mixture model. The left panel shows sampling accuracy (MMD and W2 error) against oracle complexity. The right panel illustrates how accuracy changes with dimension. ZOD-MC excels in terms of accuracy and scalability.

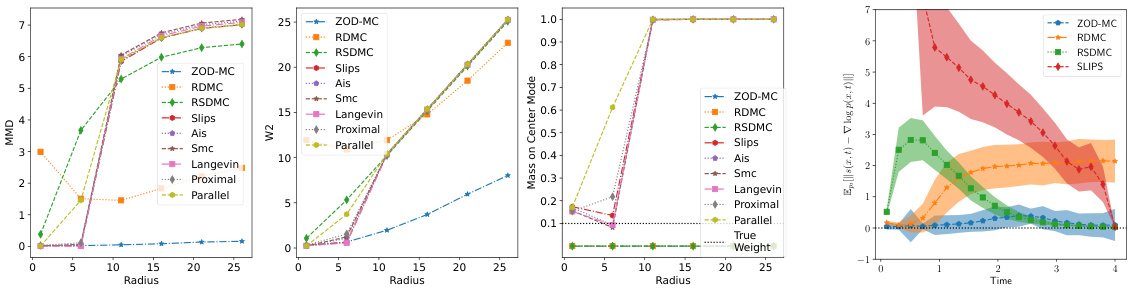

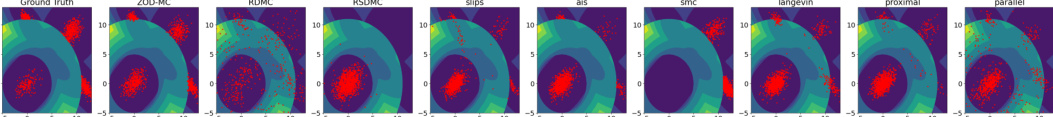

This figure compares the sampling performance of different methods (ZOD-MC, RDMC, RSDMC, SLIPS, AIS, SMC, Langevin, proximal, parallel) on an asymmetric, unbalanced Gaussian Mixture. All diffusion methods used 2200 oracles for score evaluation, while Langevin and Proximal used the same total oracle count. The figure shows that ZOD-MC successfully samples from all modes of the mixture, unlike the others which suffer from metastability (struggle to escape local minima and explore all modes).

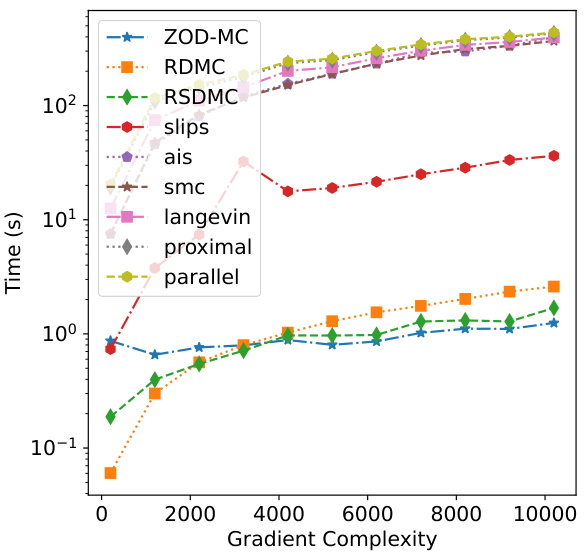

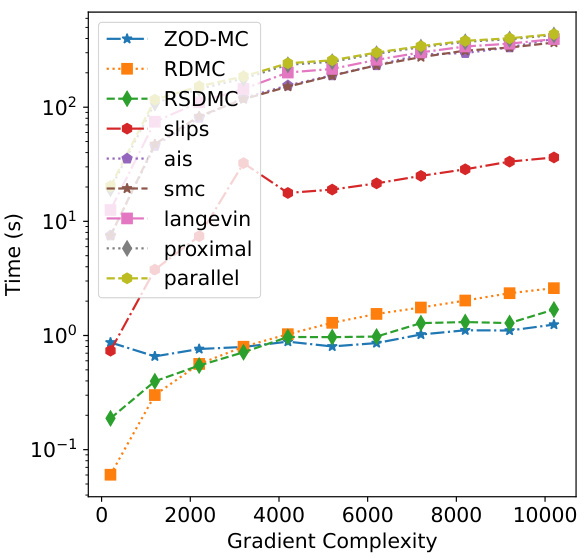

This figure compares the wall-clock time of different sampling algorithms against their oracle complexities. The oracle complexity measures the number of zeroth-order or first-order queries made to estimate the target distribution. ZOD-MC shows relatively less sensitivity to increasing complexities. The figure highlights the computational efficiency of ZOD-MC compared to other sampling methods, particularly at higher oracle complexities.

This figure compares the performance of various sampling methods on a 2D Gaussian mixture distribution. Subfigure (a) shows the sampling accuracy (measured by MMD and W2) against the oracle complexity (total number of zeroth and first order queries). ZOD-MC demonstrates the lowest error for a given oracle complexity. Subfigure (b) illustrates the performance against the dimensionality of the distribution, indicating that other diffusion-based methods struggle as the dimension increases. ZOD-MC is shown to be more robust in higher dimensions.

This figure showcases the generated samples for the Müller Brown potential using different sampling methods. The samples are overlaid on a contour plot of the potential energy surface. The figure visually demonstrates the effectiveness of each method in exploring the multi-modal potential energy landscape. All methods used the same number of oracles (1100).

This figure compares the performance of various sampling methods (ZOD-MC, RDMC, RSDMC, SLIPS, AIS, SMC, Langevin, Proximal, Parallel) on a Gaussian Mixture model. Subfigure (a) shows sampling accuracy (measured by MMD and W2 errors) against oracle complexity. ZOD-MC demonstrates the lowest error across different complexities. Subfigure (b) shows sampling accuracy against dimensionality (3D and 5D), highlighting that ZOD-MC scales more favorably with higher dimensions compared to other diffusion-based methods.

This figure compares the performance of ZOD-MC with other sampling methods (RDMC, RSDMC, SLIPS, AIS, SMC, Langevin, Proximal, Parallel) on a Gaussian Mixture model. It showcases the sampling accuracy (measured by MMD and W2) against oracle complexity and dimension. The results demonstrate ZOD-MC’s superior performance in low dimensions, achieving the lowest error with the least number of oracle queries, even when compared to other diffusion-based methods.

This figure shows the accuracy of different sampling methods for a Gaussian Mixture model. Subfigure (a) compares the sampling accuracy (measured by MMD and W2) against the oracle complexity. It demonstrates that ZOD-MC achieves the lowest error with the least number of oracle queries. Subfigure (b) shows how the sampling accuracy changes with increasing dimensionality. It indicates that diffusion based methods (including ZOD-MC) scale poorly with increasing dimensions, even if other methods are used.

This figure compares the accuracy of various sampling methods (ZOD-MC, RDMC, RSDMC, SLIPS, AIS, SMC, Langevin, Proximal, Parallel) for sampling from a Gaussian Mixture distribution. Subfigure (a) shows the sampling accuracy against oracle complexity (total number of queries), demonstrating that ZOD-MC achieves the lowest error (both in MMD and W2) using the least number of queries. Subfigure (b) shows sampling accuracy against the dimension, highlighting that ZOD-MC scales better than other diffusion-based methods in higher dimensions.

This figure compares the performance of various sampling methods (ZOD-MC, RDMC, RSDMC, SLIPS, AIS, SMC, Langevin, Proximal, Parallel) on a Gaussian Mixture model. Subfigure (a) shows the sampling accuracy (measured by MMD and W2 error) against the oracle complexity. Subfigure (b) shows the sampling accuracy against the dimension of the Gaussian Mixture. The results indicate ZOD-MC’s superior performance, especially in low dimensions, and its robustness to different complexities.

This figure shows the wall-clock time taken by different sampling algorithms (ZOD-MC, RDMC, RSDMC, SLIPS, AIS, SMC, Langevin, proximal, and parallel) as a function of the gradient complexity. The plot demonstrates the relative efficiency of each method in terms of computational time required to achieve a certain level of sampling accuracy, as measured by gradient complexity.

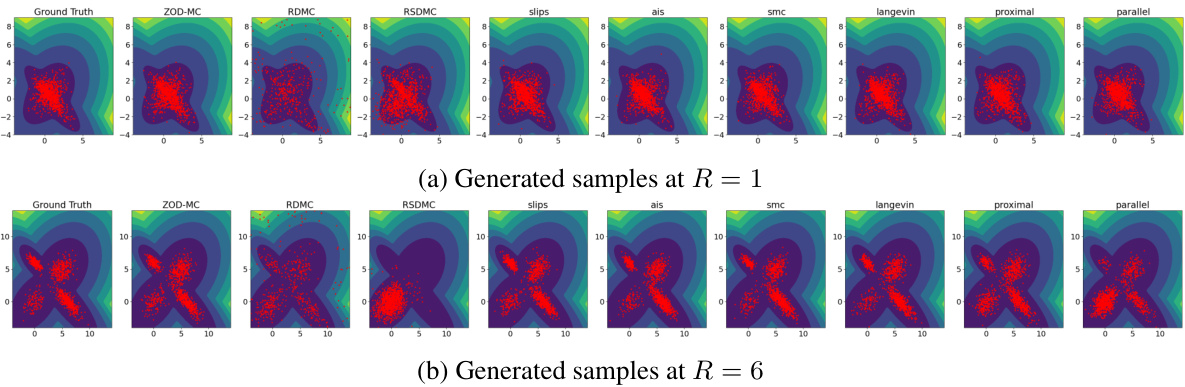

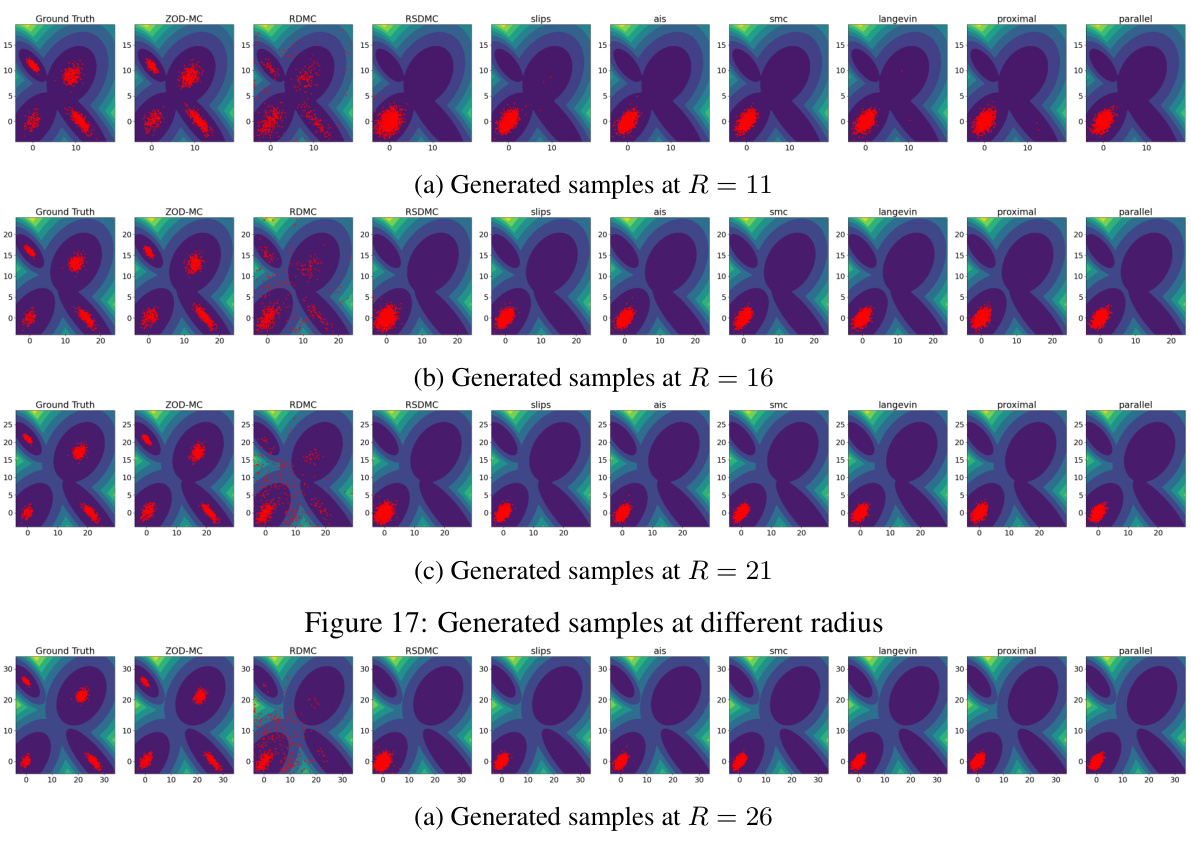

This figure presents the generated samples from different sampling methods (ZOD-MC, RDMC, RSDMC, SLIPS, AIS, SMC, Langevin, Proximal, Parallel) for a Gaussian Mixture model with different distances between modes (R = 1 and R = 6). For each method, the generated samples are shown as red points overlaid on the contour plot of the target distribution’s density. The figure visually demonstrates the performance of each sampling method in navigating multimodal distributions with varying degrees of separation between modes.

This figure compares the sampling performance of various algorithms on a Gaussian mixture model with modes increasingly separated. The separation is controlled by the parameter R, which scales the mean of each mode. The figure visually demonstrates the ability of ZOD-MC to effectively sample from all modes even when the modes are far apart and the distribution is highly multi-modal, a situation where many other methods fail due to metastability.

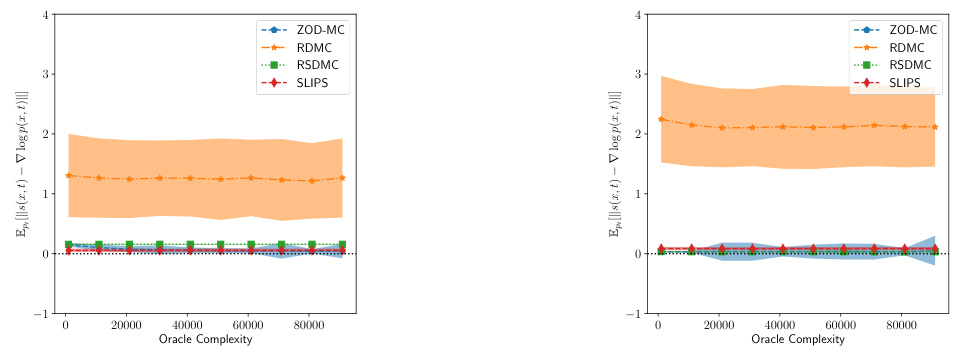

This figure compares the score error at the final time step (t=T) for different sampling methods across two different target distributions: a 2D Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) and a 5D GMM. The score error is a measure of how well the estimated score function approximates the true score function. The plot shows that ZOD-MC consistently achieves the lowest score error across various oracle complexities. This highlights the accuracy of ZOD-MC’s score estimation, which is crucial for its effectiveness in sampling from complex distributions. The results for SLIPS are also presented, but are not directly comparable due to differences in the forward diffusion process used.

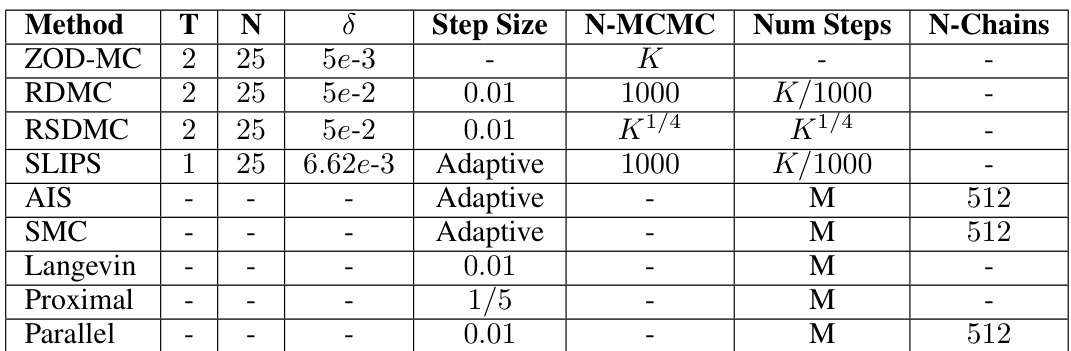

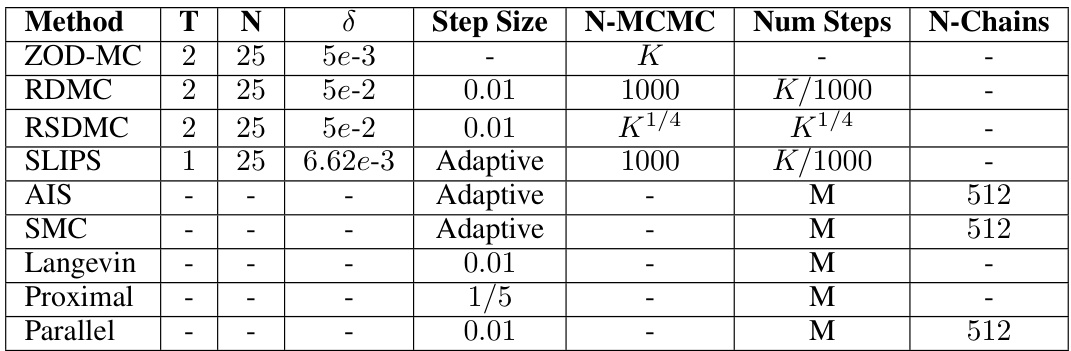

More on tables

This table compares the ZOD-MC algorithm to several other sampling algorithms (LMC, RDMC, RSDMC, and Proximal Sampler) across several criteria. These criteria include the type of query used (first-order or zeroth-order), assumptions made about the target distribution (e.g., log-concavity, soft log-concavity), the convergence criterion used (KL divergence, Total Variation distance, Wasserstein-2 distance), and the oracle complexity (the number of queries to an oracle needed to obtain an epsilon-accurate sample). The table highlights that ZOD-MC excels in low dimensions when isoperimetric assumptions are not made.

This table compares the performance of the proposed ZOD-MC algorithm to several existing sampling algorithms (LMC, RDMC, RSDMC, and Proximal Sampler). The comparison focuses on the isoperimetric assumptions made by each algorithm and their oracle complexities (the computational cost of accessing information about the target distribution) to achieve a specified level of sampling accuracy (ε). The table highlights that ZOD-MC excels in low dimensions when isoperimetric assumptions are not made, offering a competitive zeroth-order query complexity.

This table compares ZOD-MC with four other sampling algorithms (LMC, RDMC, RSDMC, and Proximal Sampler) based on several factors. It shows the type of queries used (first-order or zeroth-order), the assumptions made about the target distribution (e.g., log-concavity, soft log-concavity, or no assumptions), the convergence criterion used (KL divergence, total variation distance, or a combination), and the oracle complexity. Oracle complexity refers to the number of queries to the target distribution required to achieve a certain level of sampling accuracy. The table highlights ZOD-MC’s advantage in low-dimensional settings when isoperimetric assumptions do not hold.

This table compares the zeroth-order sampling algorithm ZOD-MC with other first-order algorithms including LMC, RDMC, RSDMC, and Proximal sampler. It summarizes the assumptions (isoperimetric or not), the criteria used for accuracy (KL-divergence or total variation), and the oracle complexity (number of queries to the oracle, which can be a gradient or zeroth-order query). The table highlights that ZOD-MC’s zeroth-order complexity has a better dependence on the accuracy parameter compared to the first order methods in the absence of isoperimetric assumption, making it more efficient in lower dimensions.

This table compares the ZOD-MC algorithm to other sampling methods (LMC, RDMC, RSDMC, and Proximal Sampler) based on several criteria, including the type of query used (first-order or zeroth-order), assumptions about the target distribution (log-concave or none), the error criterion used (KL-divergence, total variation distance, etc.), and the oracle complexity. The table highlights ZOD-MC’s advantage when there are no isoperimetric assumptions, particularly in low dimensions.

Full paper#