↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning models rely on solving non-convex optimization problems. While gradient descent is widely used, its convergence can be slow, and theoretical guarantees are often lacking, particularly for large-scale problems like matrix factorization. This is a significant challenge because faster training translates directly into improved model performance. Existing research primarily focuses on the simpler gradient descent algorithm, with limited theoretical understanding of more advanced methods.

This paper addresses this gap by providing the first provable analysis of Nesterov’s Accelerated Gradient (NAG) for rectangular matrix factorization and linear neural networks. The researchers demonstrate that NAG significantly outperforms GD, achieving a much faster convergence rate. Importantly, they introduce and successfully utilize a new unbalanced initialization technique which plays a critical role in obtaining the accelerated convergence. Their results offer both theoretical guarantees (convergence rates) and practical improvements to training efficiency.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it provides the first provable acceleration of first-order methods for non-convex optimization problems like matrix factorization and neural network training. This is a significant advancement in understanding and improving the efficiency of training complex machine learning models, impacting various fields that rely on these techniques. The unbalanced initialization strategy is also a novel approach that could prove very useful for improving convergence rates in many applications.

Visual Insights#

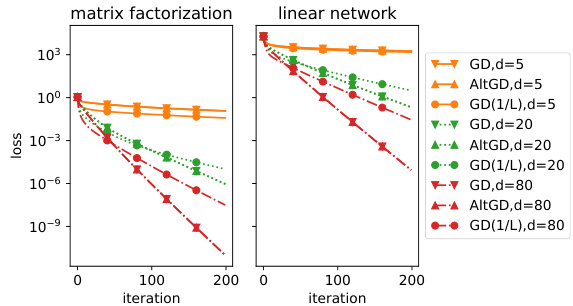

This figure compares the performance of Gradient Descent (GD) and Alternating Gradient Descent (AltGD) on two different tasks: matrix factorization (left plot) and linear neural network training (right plot). The results show that GD and AltGD exhibit similar convergence behaviors across different levels of overparameterization (d=5, d=20, d=80). This suggests that for these tasks, the more complex AltGD algorithm doesn’t offer a significant advantage in terms of convergence rate over the simpler GD.

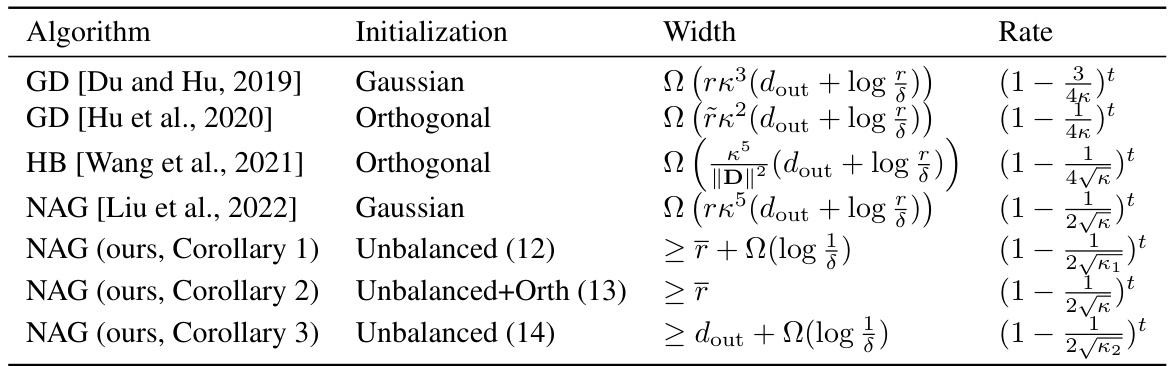

This table summarizes the convergence rates achieved by various algorithms (Gradient Descent, Nesterov’s Accelerated Gradient, Polyak’s Heavy Ball) for training two-layer linear neural networks. It compares different initialization methods (Gaussian, Orthogonal, Unbalanced) and their effect on the convergence rate and required network width. The results highlight the impact of initialization and algorithm choice on convergence speed and network size.

In-depth insights#

NAG Acceleration#

The concept of “NAG Acceleration,” referring to the application of Nesterov’s Accelerated Gradient (NAG) method, is a central theme in the provided research paper. The authors demonstrate that NAG offers significant advantages over standard gradient descent (GD) in solving non-convex optimization problems, specifically in rectangular matrix factorization and linear neural networks. Key findings include a proven accelerated convergence rate for NAG, exhibiting a linear dependence on the condition number instead of the quadratic dependence observed with GD. This acceleration is attributed to NAG’s momentum-based updates, which enable it to escape suboptimal local minima more effectively. The paper also highlights the importance of initialization, showing how an unbalanced approach, where one of the factors is initialized to zero, allows for efficient optimization and analysis. Extending these results to linear neural networks validates the broad applicability of NAG’s superior performance across various contexts. Overall, the analysis suggests that NAG represents a powerful tool for handling high-dimensional, non-convex problems in machine learning.

Unbalanced Init#

The concept of “Unbalanced Init,” likely referring to an unbalanced initialization strategy in the context of matrix factorization or neural network training, presents a significant departure from traditional balanced approaches. Instead of initializing parameters with similar scales or distributions, unbalanced initialization intentionally sets certain parameters to larger or smaller values. This approach has several key implications. It can improve convergence speed by guiding the optimization process towards more favorable regions of the parameter space, potentially avoiding saddle points or local minima. Computational efficiency may also be enhanced by requiring fewer iterations to achieve the desired solution accuracy. However, stability becomes a critical concern. An imbalanced initialization could lead to numerical instability or increased sensitivity to hyperparameter choices. Therefore, a robust theoretical analysis of this technique’s convergence properties and a thorough empirical validation assessing its performance across diverse problems and datasets are crucial. Ultimately, the success of unbalanced initialization depends on a delicate balance between accelerating convergence and maintaining numerical stability, highlighting its potential but also its inherent risks.

Linear Networks#

In the context of deep learning, linear networks represent a simplified yet insightful model. Their linearity allows for tractable mathematical analysis, making them ideal for studying fundamental concepts like gradient descent convergence and generalization. Unlike nonlinear networks, the absence of activation functions simplifies the optimization landscape, facilitating theoretical guarantees on the training process. Analyzing linear networks helps researchers understand how network width, initialization, and optimization algorithms impact learning dynamics. Despite their simplicity, linear networks can serve as building blocks for understanding more complex architectures. They reveal insights into the effects of overparameterization, where the network’s capacity surpasses the data’s dimensionality, leading to improved generalization. Furthermore, studying linear networks enables investigation of algorithmic acceleration techniques and the role of momentum in optimization algorithms. By establishing a solid theoretical foundation with linear networks, researchers can eventually extrapolate these findings to more intricate nonlinear architectures, providing a stepping stone towards a more comprehensive understanding of deep learning.

Convergence Rates#

The analysis of convergence rates in optimization algorithms is crucial for understanding their efficiency. This paper focuses on the convergence rates of first-order methods, specifically gradient descent (GD) and Nesterov’s accelerated gradient (NAG), applied to rectangular matrix factorization and linear neural networks. A key contribution is establishing provably accelerated linear convergence for NAG under an unbalanced initialization scheme. The unbalanced initialization, where one matrix is large and the other is zero, simplifies analysis. The results demonstrate how NAG achieves a faster convergence rate than GD, and highlight the impact of overparameterization on the convergence speed. The theoretical findings are supported by empirical results, showing tight bounds and the practical benefits of the proposed method and initialization. The analysis is extended to linear neural networks, offering new insights into training dynamics and width requirements.

Future Work#

The ‘Future Work’ section of this research paper presents exciting avenues for extending the current findings. Relaxing the strict rank-r constraint to encompass approximately low-rank matrices is a crucial next step, enhancing the practical applicability of the proposed methods. Furthermore, extending the analysis to nonlinear activation functions within neural networks is a significant challenge that could unlock broader implications for deep learning. Investigating the impact of different initialization schemes, beyond the unbalanced approach, would provide further insight into the optimization dynamics. Quantifying the impact of unbalanced initialization on the implicit bias of these methods, and comparing this to other initialization strategies, is another important area for future work. Finally, developing a more comprehensive theoretical framework that fully captures the convergence behavior without overly restrictive assumptions is highly desirable.

More visual insights#

More on figures

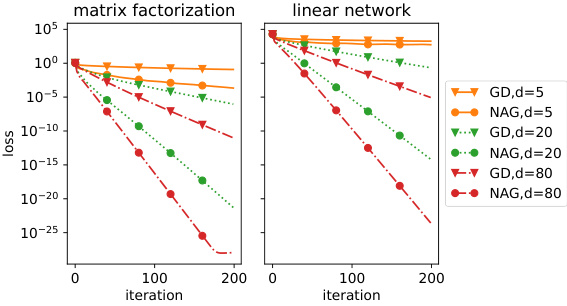

This figure compares the convergence speed of Gradient Descent (GD) and Nesterov’s Accelerated Gradient (NAG) for both matrix factorization (equation 1) and linear neural networks (equation 10). The plots show the loss function value against the number of iterations. Different lines represent different levels of overparameterization (d=5, 20, 80). In both cases, NAG demonstrates significantly faster convergence than GD, and increased overparameterization further accelerates the convergence for NAG. The results visually support the theoretical findings presented in the paper that NAG achieves a faster convergence rate than GD.

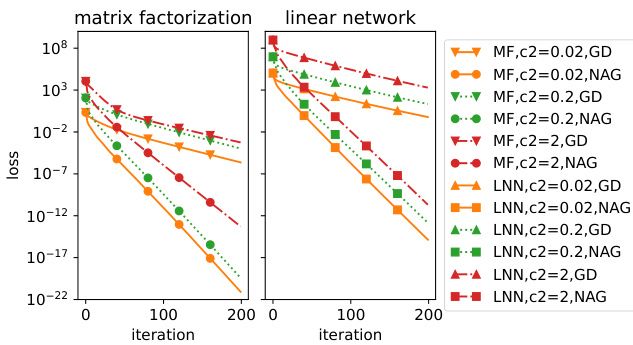

This figure compares the theoretical predictions of the loss functions with the actual loss values obtained from numerical experiments for both gradient descent (GD) and Nesterov’s Accelerated Gradient (NAG) methods in the context of matrix factorization. The experiments were conducted with two different condition numbers (κ = 10 and κ = 100), and the results are shown for three different levels of overparameterization (d = 5, 20, and 80). The theoretical predictions align closely with the actual loss values, especially for GD, which indicates that the theoretical analysis provides a tight bound on the convergence rate.

This figure compares the convergence speed of Gradient Descent (GD) and Nesterov’s Accelerated Gradient (NAG) for both matrix factorization problem (1) and linear neural networks (10). The plots show that NAG consistently converges faster than GD across different levels of overparameterization (width, d = 5, 20, 80). This supports the paper’s claim of NAG’s superior convergence rate.

This figure compares the performance of Gradient Descent (GD) and Nesterov’s Accelerated Gradient (NAG) on larger-sized matrices and linear neural networks. The left panel shows matrix factorization with dimensions m=1200 and n=1000, while the right panel shows a linear neural network with m=500, n=400, and N=600. It demonstrates that the trends observed in Figure 2 (faster convergence of NAG compared to GD) hold even for larger problem sizes. The consistent behavior across different scales confirms the robustness and generalizability of the findings.

This figure compares the theoretical predictions of the loss function at each iteration with the actual loss obtained during experiments for both GD and NAG methods in matrix factorization. Two different condition numbers (κ=10 and κ=100) are used to assess the accuracy of the theoretical predictions over various levels of overparametrization (d=5, 20, 80). The theoretical curves are generated using the formulas derived in Theorems 1 and 2. The close match between the theoretical and experimental curves indicates the tightness of the theoretical bounds, particularly for the GD method.

Full paper#