↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Fine-tuning large language models (LLMs) is computationally expensive, demanding significant memory and time. Existing parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) techniques only partially address this issue, leaving substantial computational costs and activation memory unresolved. This is particularly problematic when training very large models or working with long sequences.

DropBP, a novel approach, tackles this problem by randomly dropping layers during backward propagation. This clever strategy reduces computational costs and activation memory without sacrificing accuracy. The algorithm also calculates layer sensitivity to assign appropriate drop rates, ensuring stable training. Experimental results demonstrate a 44% reduction in training time with comparable accuracy, while also enabling significantly longer sequences to be processed. DropBP’s ease of integration with existing PEFT methods and its substantial performance improvements makes it a significant advancement in LLM fine-tuning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs) because it introduces a novel and efficient fine-tuning method. DropBP significantly reduces training time and memory costs, enabling faster experimentation and the training of larger models with limited resources. This opens new avenues for research in efficient LLM training, and its easy-to-integrate PyTorch library makes it accessible to a wide range of researchers. The enhanced throughput achieved on different hardware architectures further enhances its practical significance.

Visual Insights#

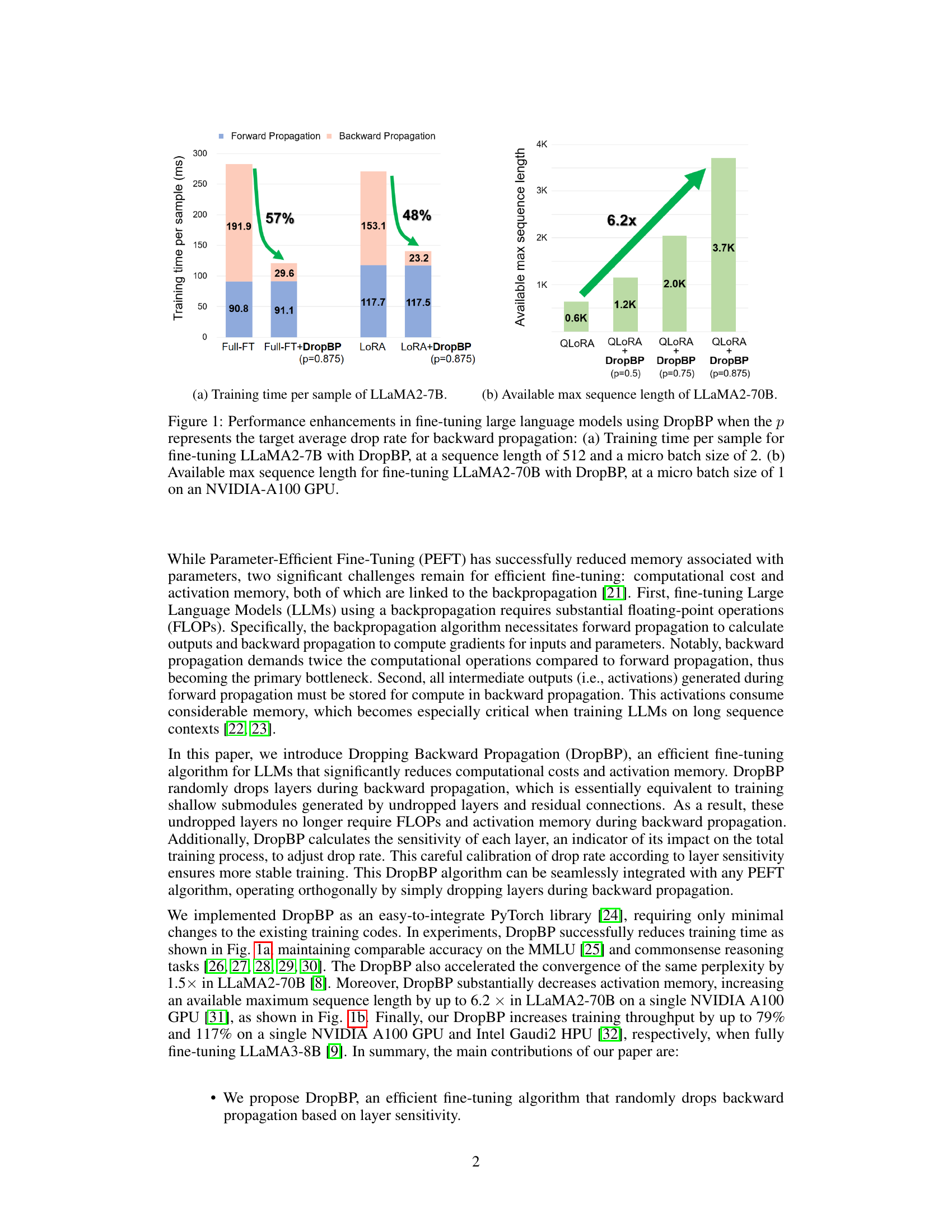

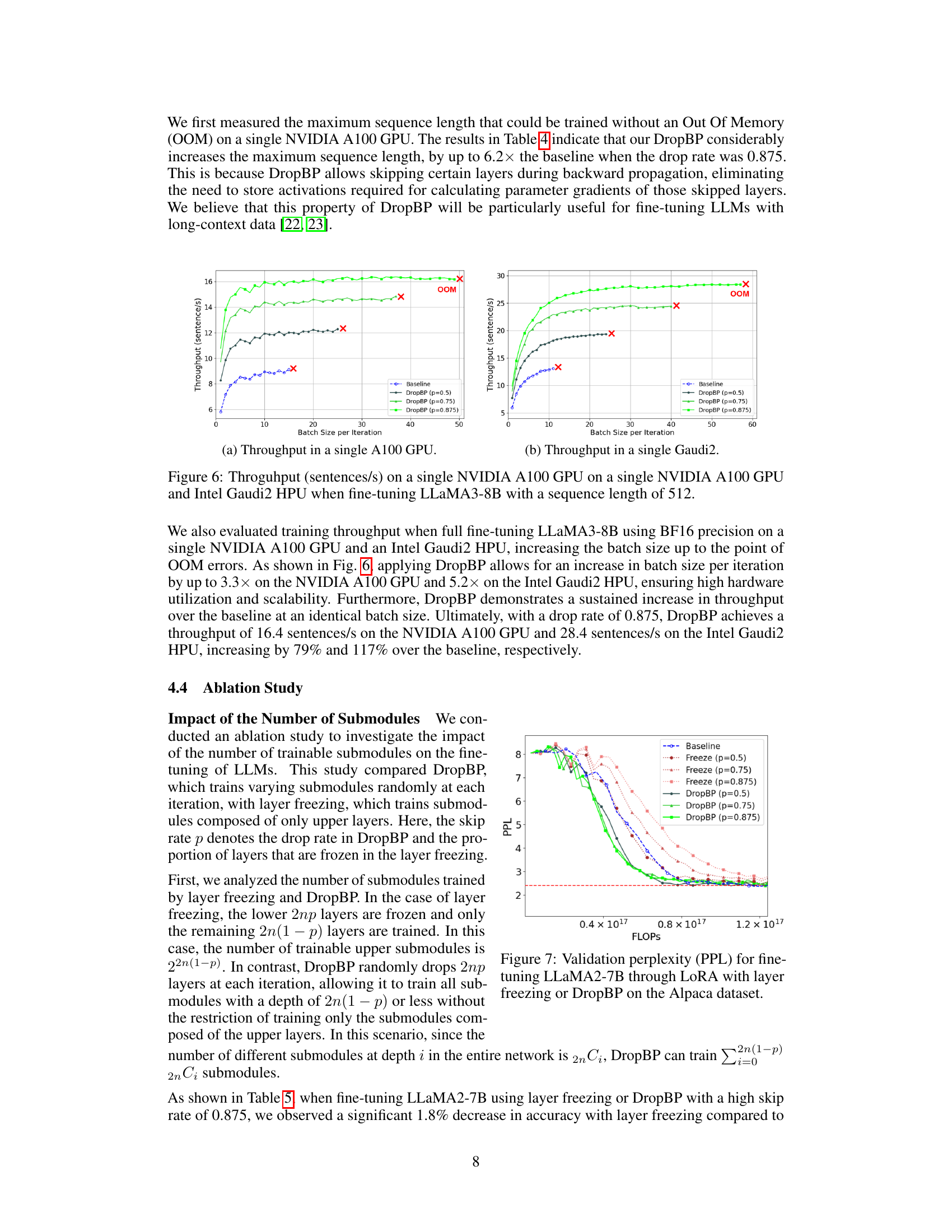

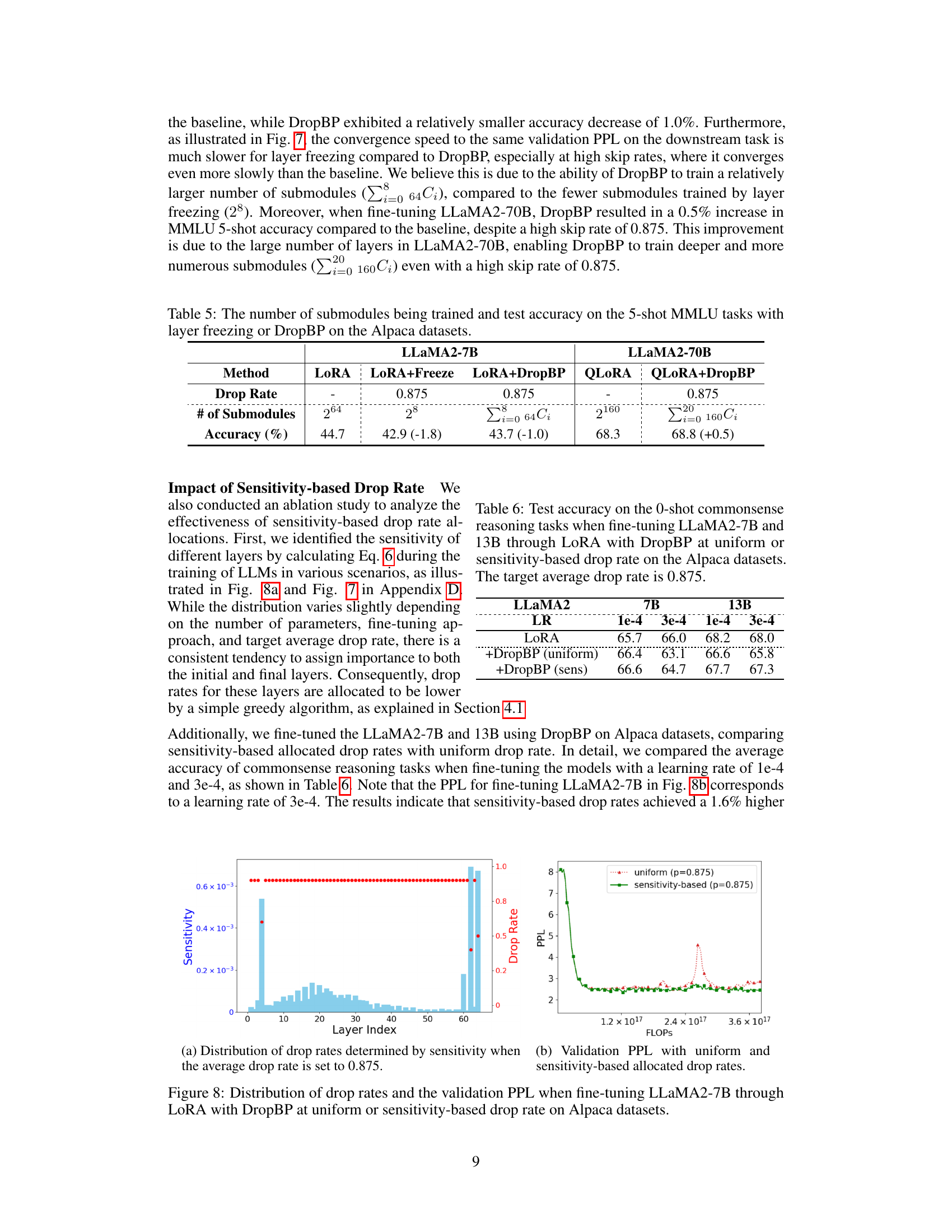

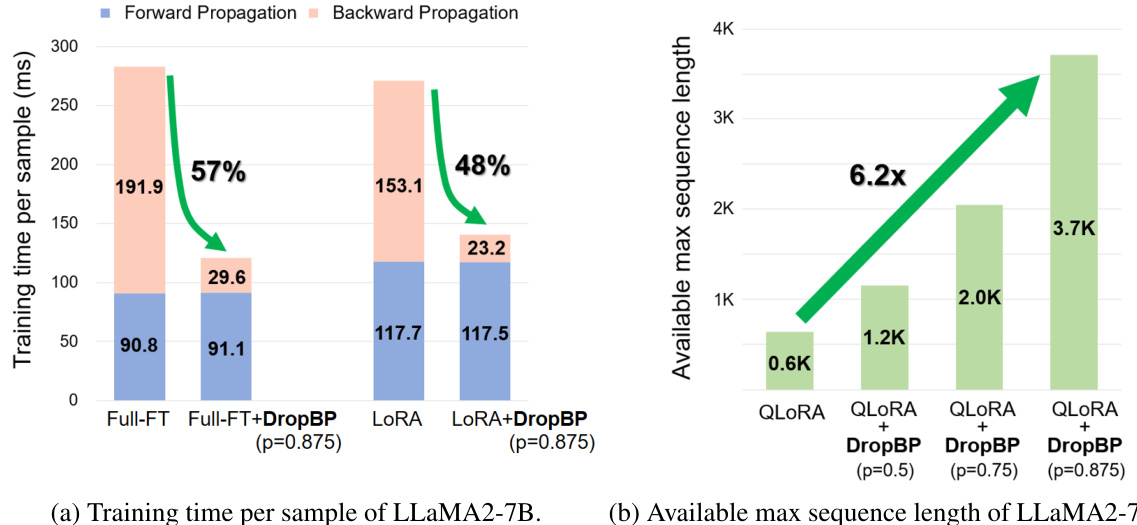

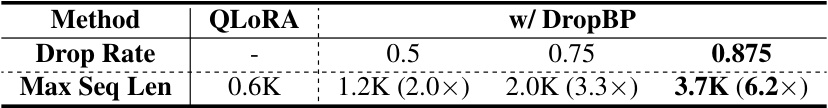

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of DropBP in accelerating the fine-tuning of large language models. Subfigure (a) shows a significant reduction in training time per sample for LLaMA2-7B when using DropBP compared to the baseline, with training time reduced by 57% for full fine-tuning and 48% for LoRA. Subfigure (b) illustrates the increase in the maximum sequence length achievable during fine-tuning of LLaMA2-70B using DropBP. The maximum sequence length increases by up to 6.2x compared to the baseline when using DropBP with a drop rate of 0.875.

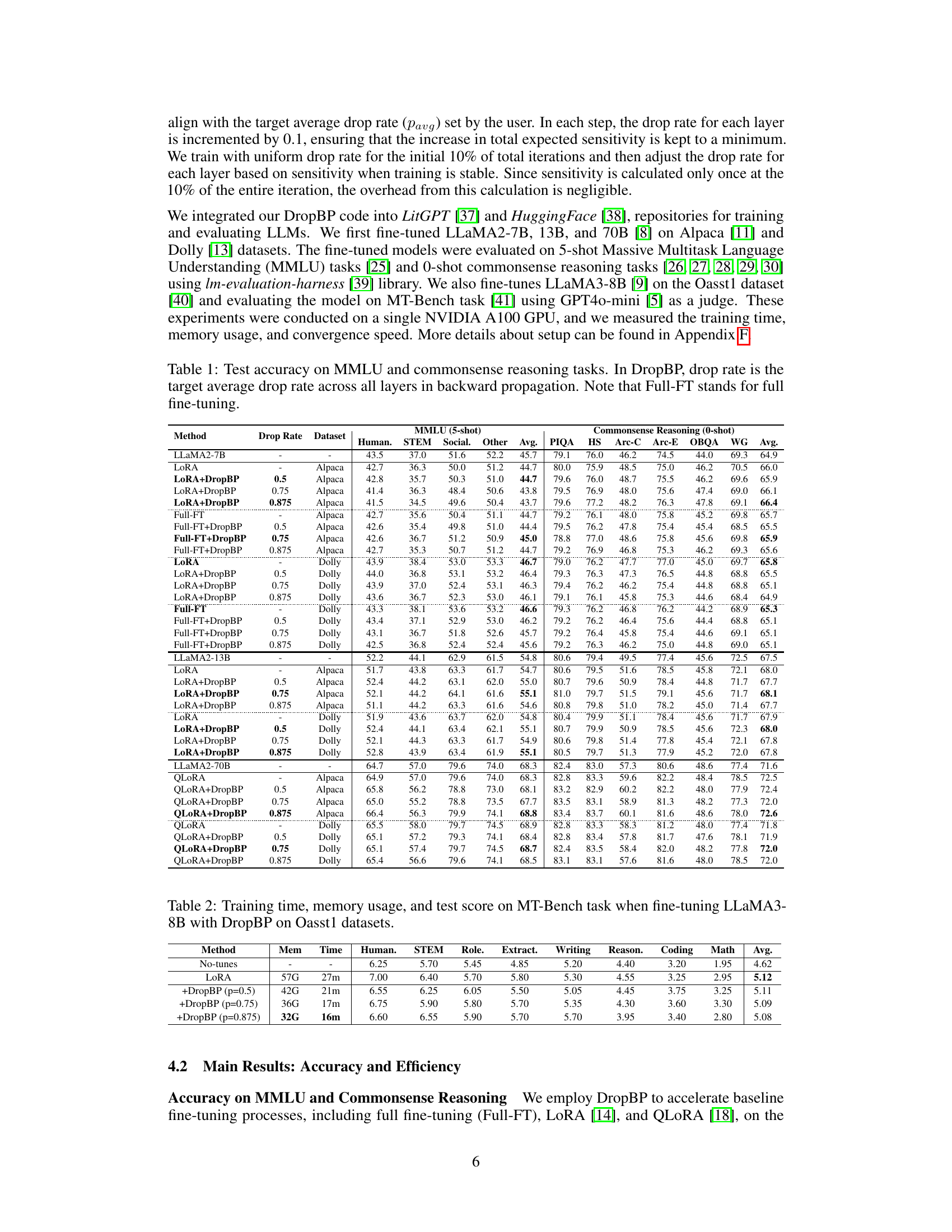

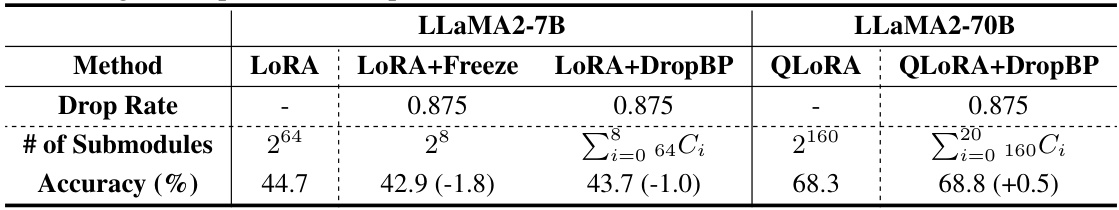

This table presents the results of the experiments conducted to evaluate the accuracy of different fine-tuning methods on two benchmark datasets: the Massive Multitask Language Understanding (MMLU) and a set of commonsense reasoning tasks. The table compares the performance of full fine-tuning (Full-FT), LoRA, and LoRA combined with DropBP (Dropping Backward Propagation) at different drop rates (0.5, 0.75, and 0.875). The results are shown separately for Alpaca and Dolly datasets. The table aims to demonstrate that DropBP can achieve comparable accuracy while significantly reducing the training time and memory consumption.

In-depth insights#

DropBP: Core Idea#

DropBP’s core idea centers on accelerating the fine-tuning of Large Language Models (LLMs) by strategically dropping layers during backward propagation. This isn’t a random process; DropBP calculates the sensitivity of each layer, essentially determining its importance to the overall training. Layers deemed less crucial are dropped with a higher probability, significantly reducing computational cost and activation memory. The algorithm’s cleverness lies in its ability to maintain accuracy despite this targeted layer dropping. Furthermore, DropBP is designed to be orthogonal to existing Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) methods, meaning it can be seamlessly integrated with techniques like LoRA or QLoRA for even greater efficiency gains. The sensitivity-based layer dropping ensures the training process remains stable, effectively making fine-tuning larger models with longer sequences significantly more practical.

DropBP: Experiments#

A hypothetical ‘DropBP: Experiments’ section would detail the empirical evaluation of the DropBP algorithm. This would involve describing the datasets used (likely large language model training datasets), the baselines compared against (e.g., full fine-tuning, LoRA, QLoRA), and the metrics employed to assess performance (accuracy on downstream tasks, training time, memory usage, sequence length). Key results would showcase DropBP’s ability to reduce training time and memory consumption while maintaining comparable accuracy. The experiments should rigorously control variables and analyze the impact of hyperparameters like the target drop rate (p) on performance. Ablation studies would isolate the contributions of DropBP’s key components (random layer dropping and sensitivity-based drop rate allocation). Ideally, the experimental section would include error bars or other measures of statistical significance to enhance the reliability of reported results. Furthermore, discussions of computational resource requirements (GPUs used, training time per epoch) and potential limitations would strengthen the analysis.

Sensitivity-Based Rates#

The concept of ‘Sensitivity-Based Rates’ in the context of a machine learning model, likely a large language model (LLM), suggests a method for adaptively adjusting the training process based on the impact of individual layers. Instead of uniformly applying a dropout rate across all layers during backpropagation, this method assesses each layer’s influence on the overall learning process. This assessment, often referred to as ‘sensitivity’, is calculated by quantifying how much altering the gradient of a specific layer affects the final output gradient. Layers deemed highly sensitive would have a lower dropout probability to preserve their contribution to the learning. Conversely, less sensitive layers could have a higher dropout probability to save computation and memory, potentially without significantly impacting the training outcome. This approach aims to improve training efficiency while maintaining accuracy by intelligently focusing resources on the most impactful layers. The method’s success hinges on accurately estimating the sensitivity of different layers and defining a relationship between sensitivity and appropriate dropout rates; an effective approach could significantly reduce computational costs and activation memory, especially in training massive LLMs. The method might necessitate an iterative procedure for calculating sensitivity and adjusting rates, possibly during training. A significant challenge would be to devise a reliable method for calculating layer sensitivity that’s computationally inexpensive and effectively guides the rate allocation process.

DropBP: Limitations#

DropBP, while effective in accelerating fine-tuning, has limitations. Its random layer dropping might not be optimal for all model architectures or tasks, potentially hindering performance in specific scenarios. The reliance on sensitivity-based drop rate allocation, while improving stability, adds computational overhead. The approach is primarily designed for fine-tuning and may not directly translate to pre-training. Further investigation is needed to determine its generalizability across diverse model sizes and training objectives. Thorough empirical evaluation on a wider range of datasets and tasks is crucial to fully understand its effectiveness and limitations. While DropBP shows promise, further research is warranted to optimize its performance and expand its applicability.

Future of DropBP#

The future of DropBP looks promising, given its demonstrated ability to significantly accelerate fine-tuning of LLMs while maintaining accuracy. Further research could explore adaptive drop rate strategies that dynamically adjust layer-dropping probabilities based on real-time training performance, potentially optimizing for even faster convergence. Integrating DropBP with other PEFT techniques like LoRA and QLoRA could create more powerful and efficient fine-tuning methods. Extending DropBP to other model architectures beyond transformers, and investigating its efficacy on different downstream tasks, would expand its applicability. Exploring the theoretical limits of DropBP, determining the optimal balance between computational savings and accuracy loss, is another avenue for future work. Finally, developing a more sophisticated method for layer sensitivity calculation than current gradient variance approximations, could further enhance the method’s stability and performance. These avenues of research could establish DropBP as a fundamental component in future LLM training pipelines.

More visual insights#

More on figures

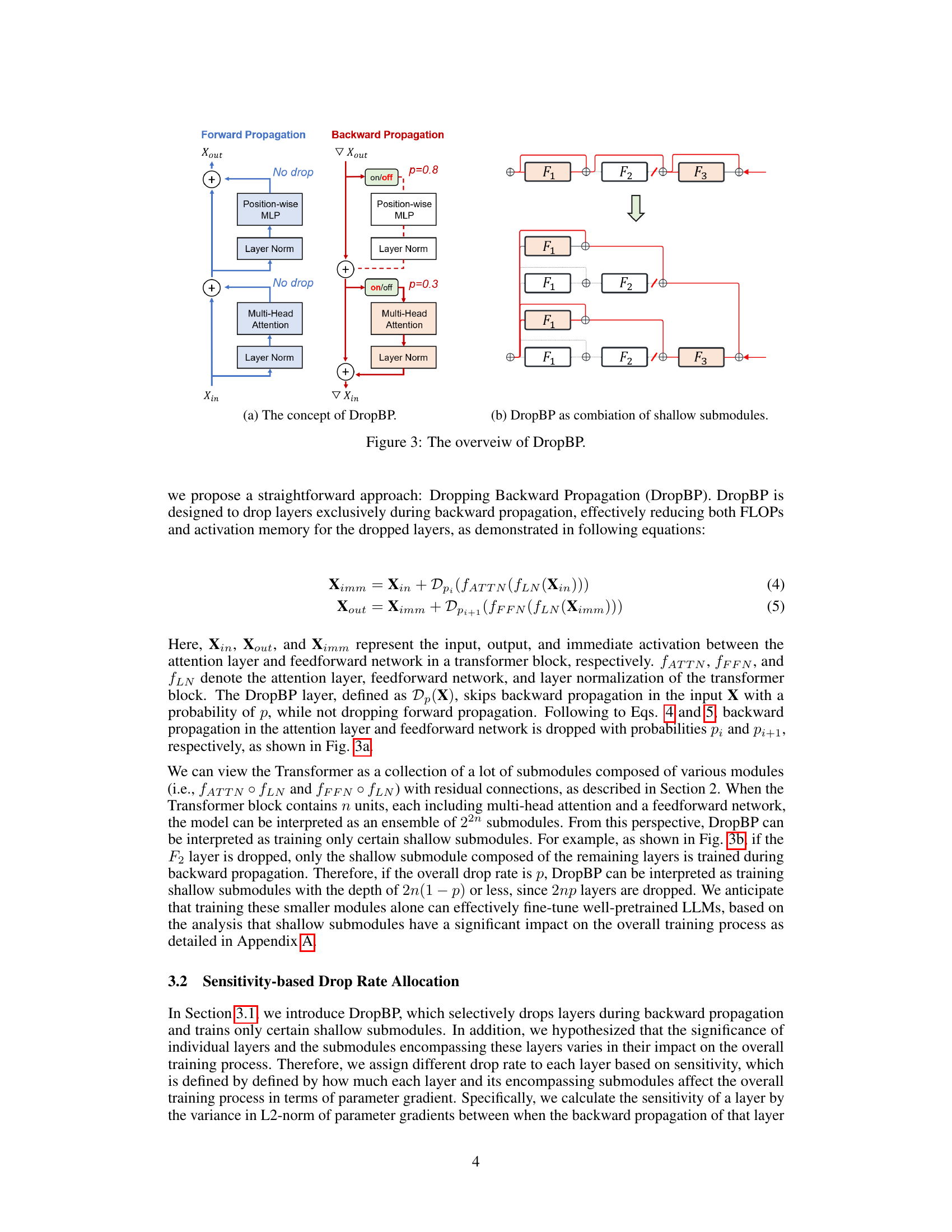

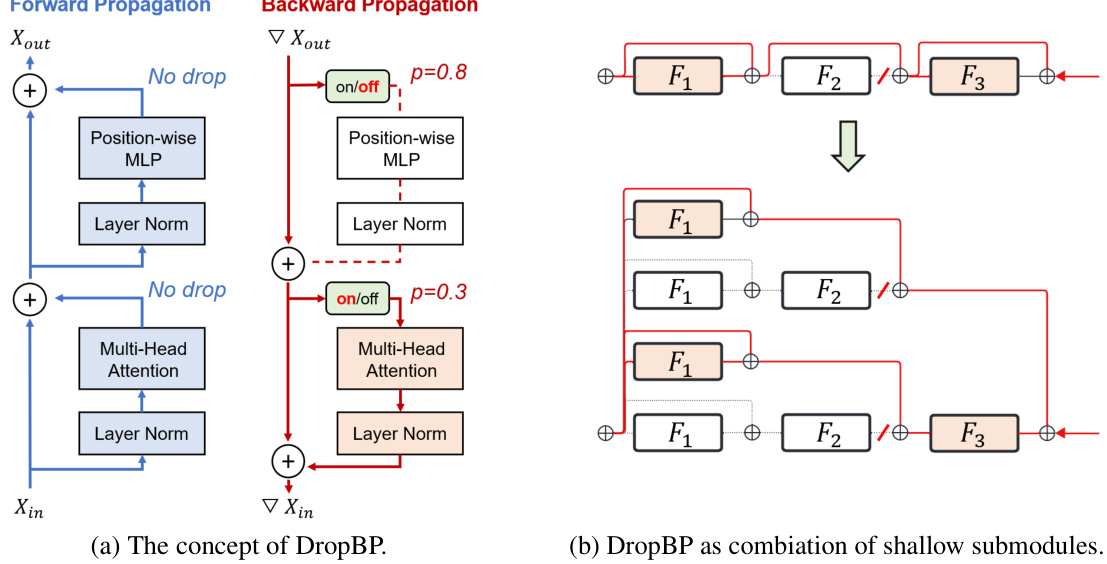

This figure shows the concept of DropBP (Dropping Backward Propagation) in two parts: (a) illustrates how DropBP randomly drops layers during backward propagation, and (b) demonstrates how DropBP can be interpreted as training shallow submodules created by the undropped layers and residual connections. It highlights the mechanism where layers are randomly turned off with probability ‘p’ during backward propagation, significantly reducing computational costs and activation memory.

The figure shows the concept of DropBP (Dropping Backward Propagation) and how it works as a combination of shallow submodules. Panel (a) illustrates the process, highlighting the random dropping of layers during backward propagation with probabilities (p) assigned based on layer sensitivity. Panel (b) visually represents the effect of DropBP, showing that by dropping certain layers, the overall model effectively becomes an ensemble of various shallower submodules, reducing computational cost and activation memory.

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of DropBP in accelerating the fine-tuning of large language models. (a) shows a significant reduction in training time per sample for LLaMA2-7B when using DropBP compared to a baseline without DropBP, across various fine-tuning methods (Full-FT and LoRA). (b) showcases the substantial increase in the maximum sequence length achievable for LLaMA2-70B when using DropBP, highlighting its capacity to handle longer sequences.

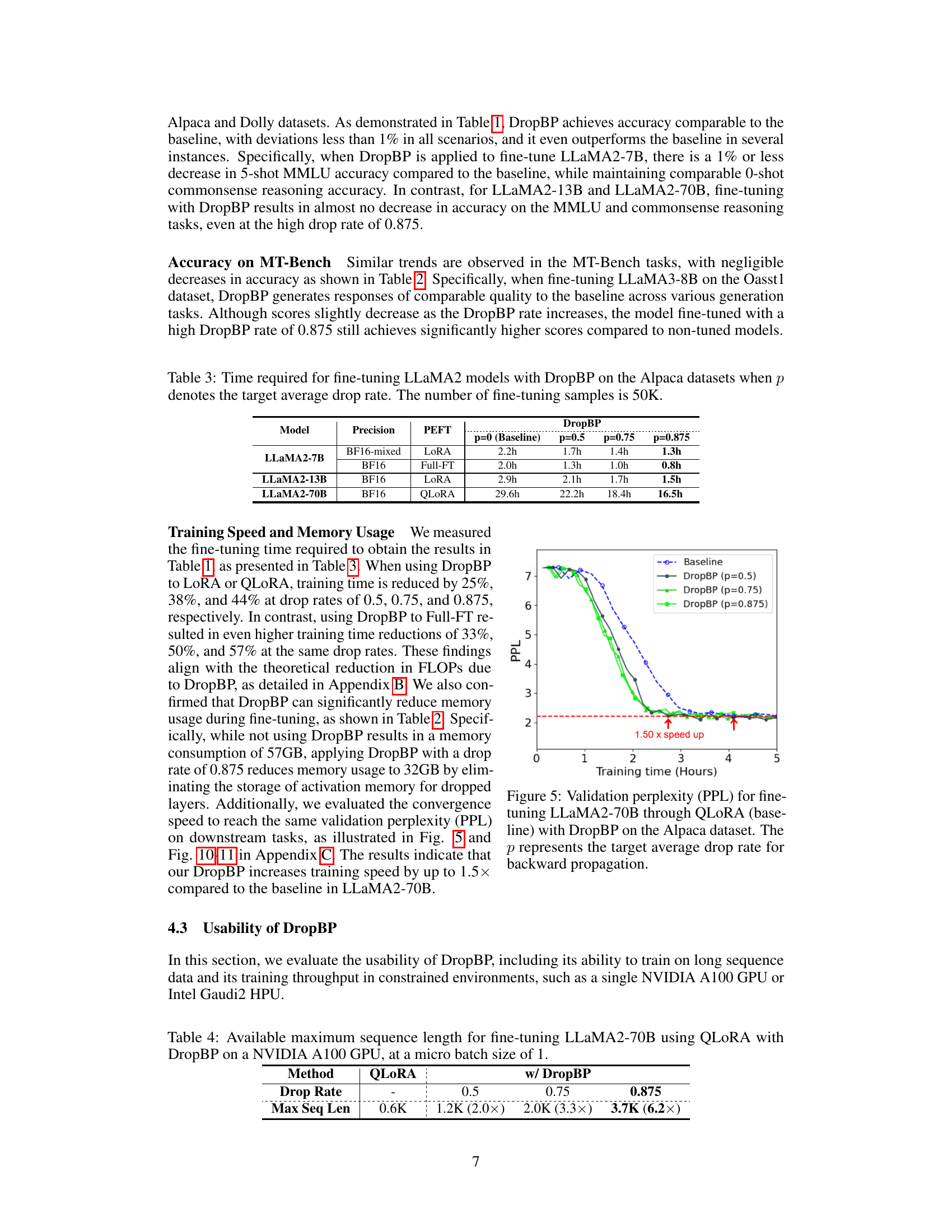

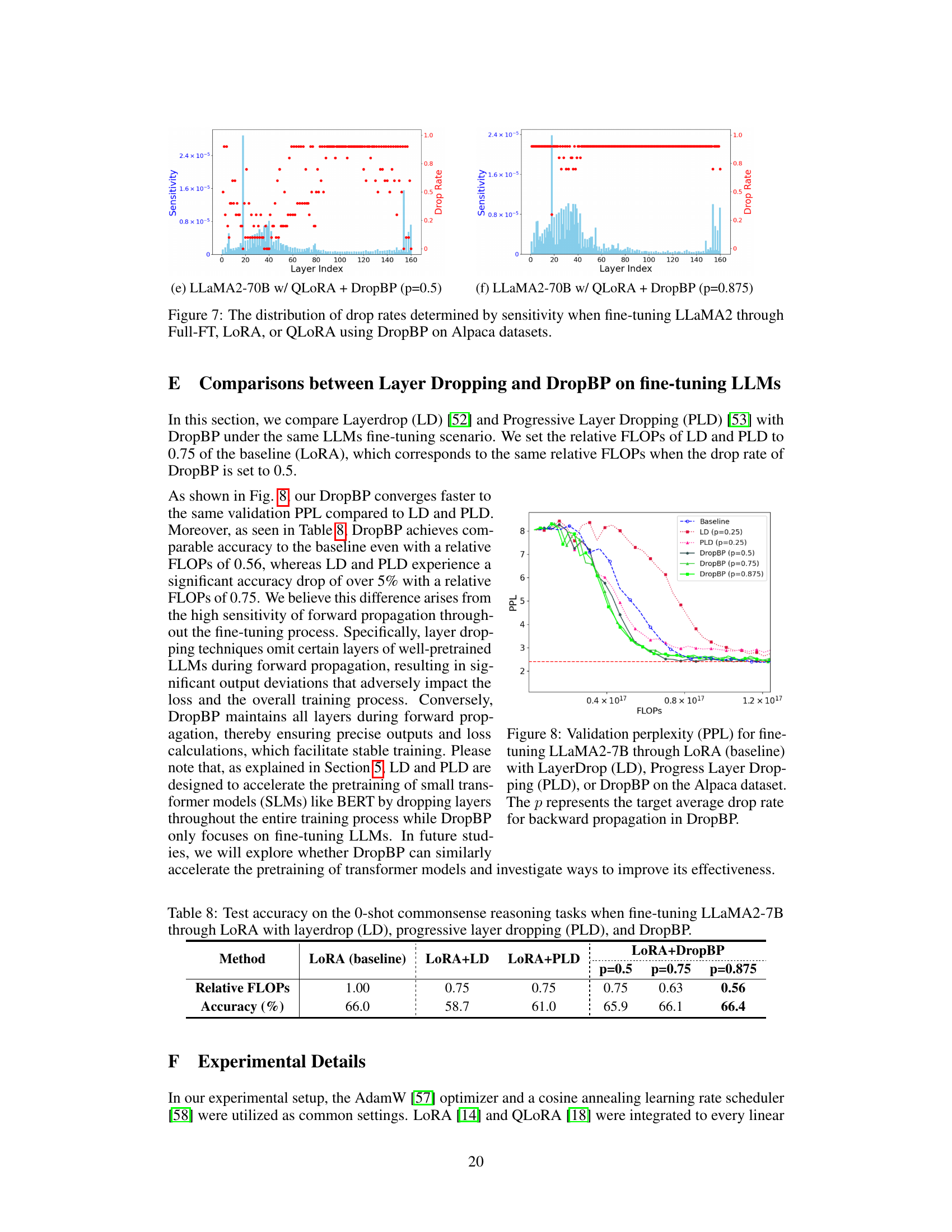

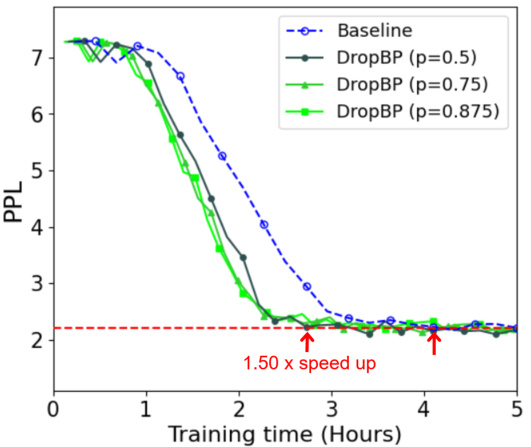

This figure shows the validation perplexity (PPL) over training time (in hours) for fine-tuning the LLaMA2-70B language model using the QLoRA method with and without DropBP. The baseline (no DropBP) is shown for comparison. Multiple lines represent different DropBP configurations with varying target average drop rates (p) for backward propagation. The figure highlights that DropBP accelerates convergence, reaching a similar perplexity in less time than the baseline. The speedup is quantified as 1.5x.

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of DropBP in accelerating the fine-tuning of large language models. Subfigure (a) shows a significant reduction in training time per sample for LLaMA2-7B when using DropBP compared to a baseline. Subfigure (b) showcases a substantial increase in the maximum sequence length achievable for LLaMA2-70B using DropBP, highlighting its capability to handle longer sequences during training.

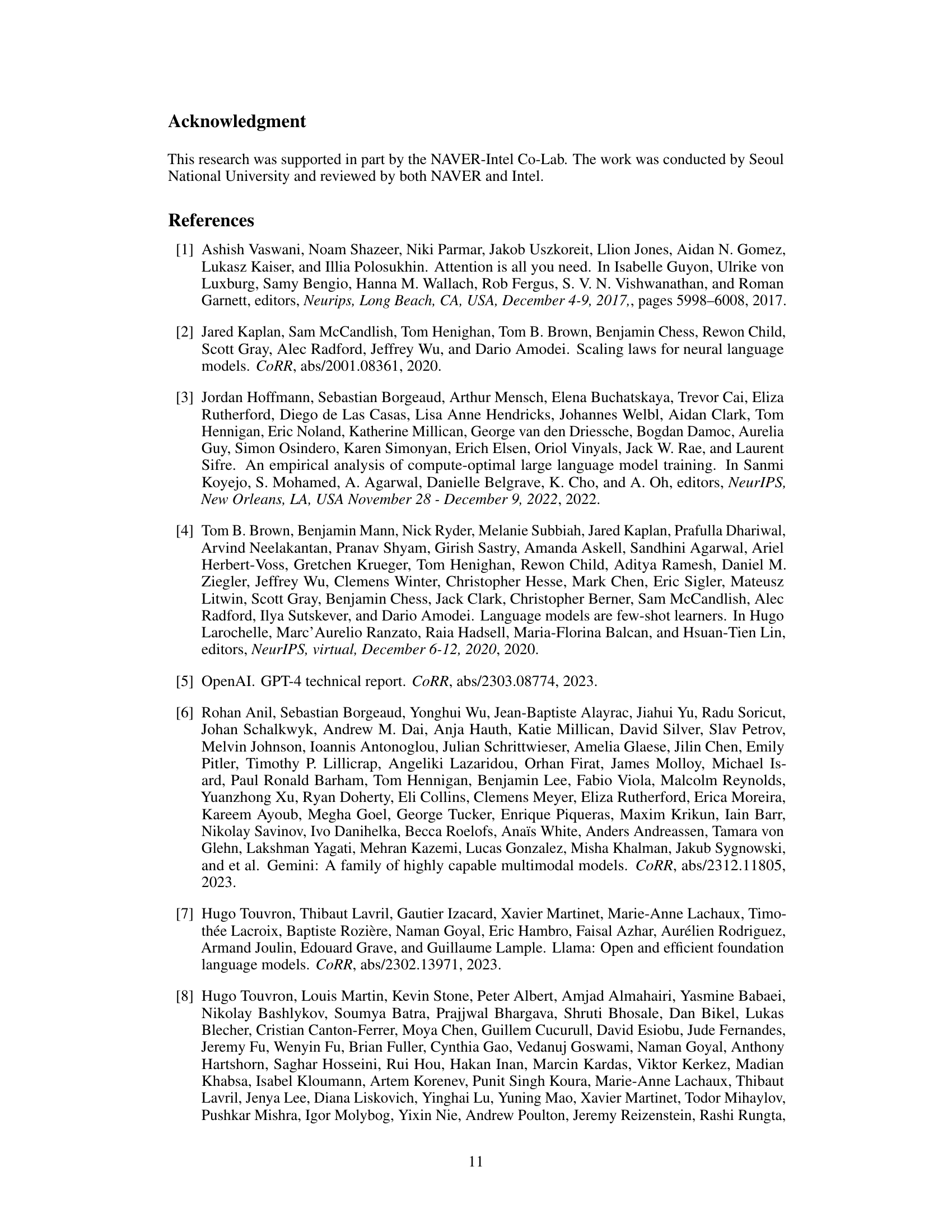

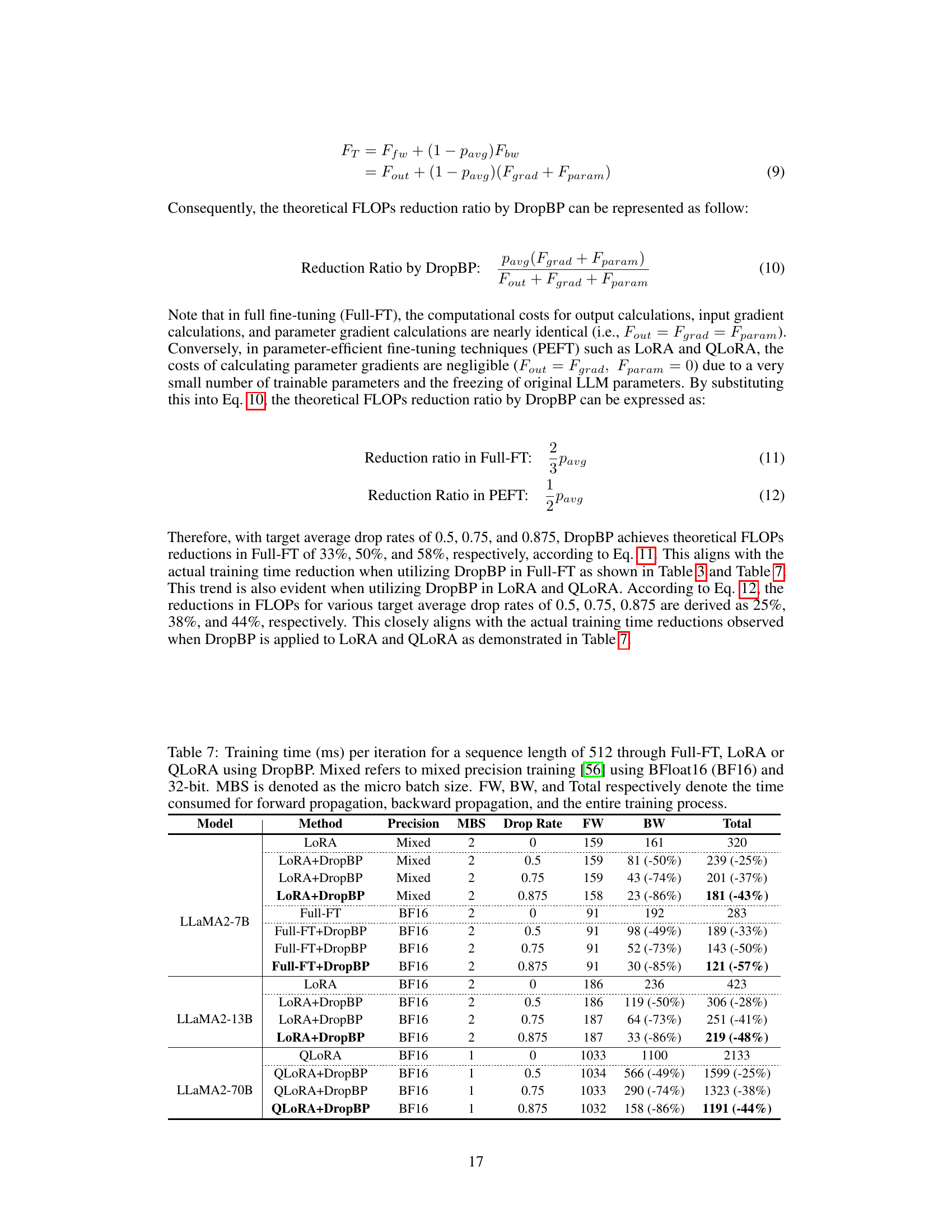

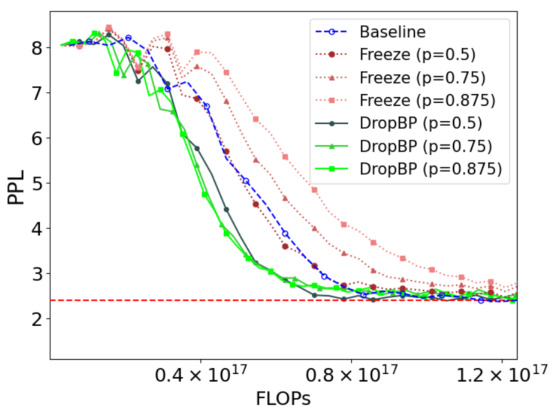

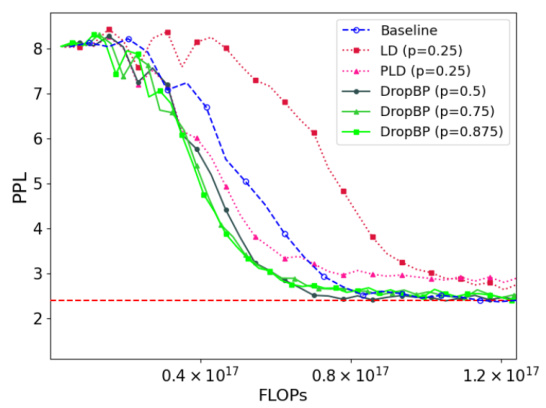

This figure compares the performance of DropBP against baseline LoRA and other layer dropping methods (LayerDrop and Progressive Layer Drop) on the Alpaca dataset. The x-axis represents the FLOPs used, and the y-axis shows the validation perplexity (PPL), a measure of the model’s performance. DropBP demonstrates faster convergence to lower PPL than LD and PLD, while maintaining comparable accuracy.

This figure showcases the performance improvements achieved by using DropBP in fine-tuning large language models. Subfigure (a) compares the training time per sample for LLaMA2-7B with and without DropBP, demonstrating a significant reduction in training time with DropBP. Subfigure (b) illustrates the increase in the maximum available sequence length for LLaMA2-70B when using DropBP, highlighting its ability to handle longer sequences more efficiently. The variable ‘p’ represents the target average drop rate used in the backward propagation process.

This figure shows the impact of path length on gradient magnitude during the fine-tuning of LLaMA2-7B. It consists of three sub-figures. (a) shows the distribution of path lengths, indicating the probability of encountering paths of various lengths within the network. (b) demonstrates the gradient magnitude at the input for each path length. It reveals that shorter paths generally have larger gradient magnitudes compared to longer ones. (c) presents the total gradient magnitude for each path length, showcasing that shorter paths contribute more significantly to the overall gradient. The combined observations indicate the importance of short paths (shallow submodules) for effective training in residual networks, which forms the basis for the DropBP method’s design.

This figure showcases the performance improvements achieved by incorporating DropBP into the fine-tuning process of large language models. Specifically, it demonstrates (a) a significant reduction in training time per sample for LLaMA2-7B when using DropBP (with different drop rates), and (b) a considerable increase in the maximum sequence length achievable for LLaMA2-70B when DropBP is applied. These improvements highlight the efficiency gains offered by the DropBP method, allowing for faster training and the handling of longer sequences.

This figure showcases the performance improvements achieved by using DropBP in fine-tuning large language models. Subfigure (a) compares the training time per sample for LLaMA2-7B with and without DropBP, demonstrating a significant reduction in training time with DropBP. Subfigure (b) illustrates the impact of DropBP on the maximum sequence length achievable during fine-tuning of LLaMA2-70B, showing a considerable increase in sequence length when DropBP is employed.

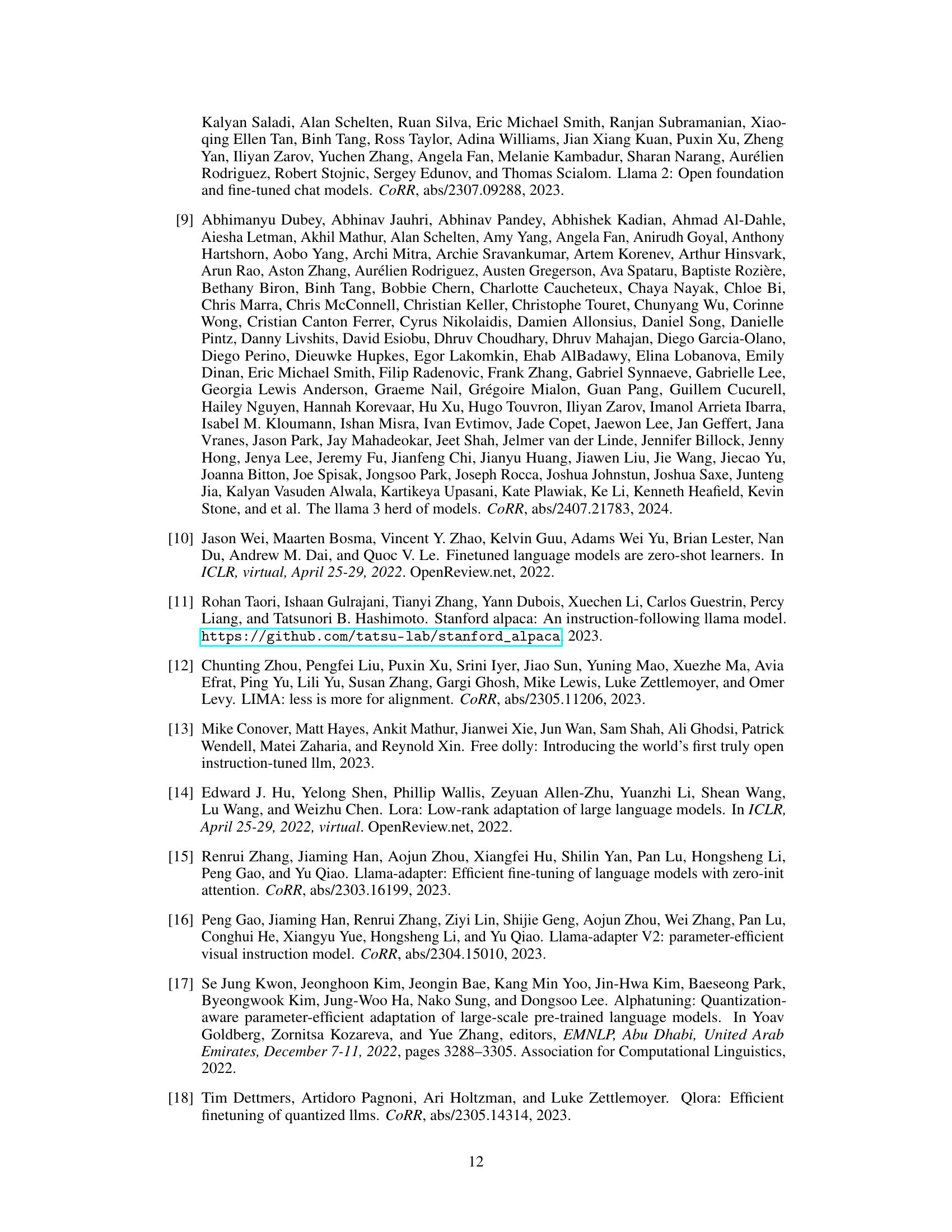

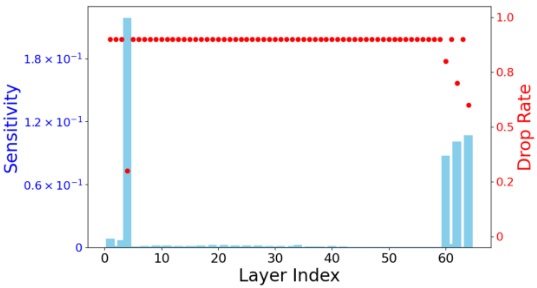

This figure shows two subfigures. The left subfigure (a) is a scatter plot showing the sensitivity of each layer (x-axis) against its assigned drop rate (y-axis). A histogram is overlaid showing the distribution of drop rates determined by sensitivity. The right subfigure (b) shows a line graph comparing the validation perplexity (PPL) against FLOPS (floating point operations) for both uniform and sensitivity-based drop rates. The sensitivity-based allocation leads to better validation perplexity.

This figure shows two subfigures. The left subfigure is a histogram showing the distribution of drop rates determined by the sensitivity of each layer when the average drop rate is set to 0.875. The right subfigure is a line graph showing the validation perplexity (PPL) for fine-tuning LLaMA2-7B through LORA with DropBP, comparing uniform and sensitivity-based drop rates. The x-axis represents the FLOPs, and the y-axis represents the PPL. The results show that sensitivity-based drop rates achieve a 1.6% higher accuracy compared to uniform drop rates with a relatively high learning rate of 3e-4.

This figure visualizes the distribution of drop rates assigned to different layers of a LLaMA2-7B model during fine-tuning using the DropBP algorithm. The left panel shows the sensitivity of each layer, calculated based on how much changes in the gradient that layer produces, impacting the overall loss. The right panel displays the resulting drop rates based on two allocation methods: a uniform approach assigning same drop rate to all layers, and a sensitivity-based approach where rates are tailored to each layer’s sensitivity. The graph also shows how the validation perplexity (PPL), a metric to evaluate the model’s performance, changes depending on the chosen drop rate allocation method.

This figure shows two sub-figures. The left sub-figure shows the distribution of drop rates determined by sensitivity when the average drop rate is set to 0.875 for fine-tuning LLaMA2-7B through LORA with DropBP on Alpaca datasets. The right sub-figure shows the validation perplexity (PPL) with uniform and sensitivity-based allocated drop rates for fine-tuning LLaMA2-7B through LORA with DropBP on Alpaca datasets. The x-axis represents the FLOPs and y-axis represents the validation PPL. The sensitivity-based drop rate allocation achieves a lower validation perplexity than uniform drop rate allocation.

This figure demonstrates the performance improvements achieved by using DropBP in fine-tuning large language models. Subfigure (a) shows a comparison of training time per sample for LLaMA2-7B with and without DropBP, highlighting the significant reduction in training time. Subfigure (b) showcases the increase in the maximum sequence length achievable when fine-tuning LLaMA2-70B using DropBP, indicating its effectiveness in handling longer sequences on a single GPU. Different values of p (target average drop rate for backward propagation) are used in the experiments.

This figure compares the performance of DropBP against baseline LoRA, Layerdrop (LD), and Progressive Layer Dropping (PLD) in terms of validation perplexity (PPL) achieved on the Alpaca dataset while varying the FLOPs (floating-point operations). It shows that DropBP achieves comparable PPL to the baseline with significantly fewer FLOPs, outperforming LD and PLD which suffer from accuracy drops when reducing FLOPs.

More on tables

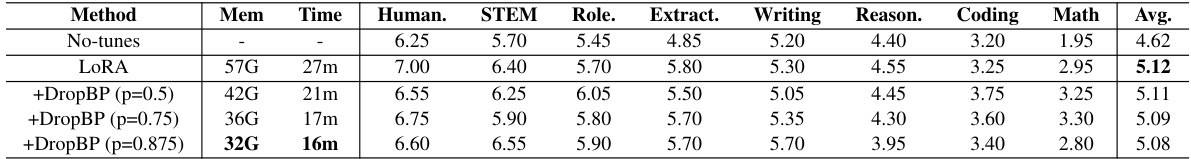

This table presents the results of fine-tuning the LLaMA3-8B language model on the Oasst1 dataset using different methods: no fine-tuning (No-tunes), LoRA, and LoRA combined with DropBP at various drop rates (0.5, 0.75, and 0.875). For each method, it shows the memory usage (Mem), training time (Time), and test scores on the MT-Bench task, broken down by different sub-tasks (Human, STEM, Role, Extract, Writing, Reason, Coding, Math). The average score across all sub-tasks is also provided (Avg.). The table demonstrates DropBP’s impact on reducing both memory usage and training time while maintaining comparable performance to the baseline (LoRA).

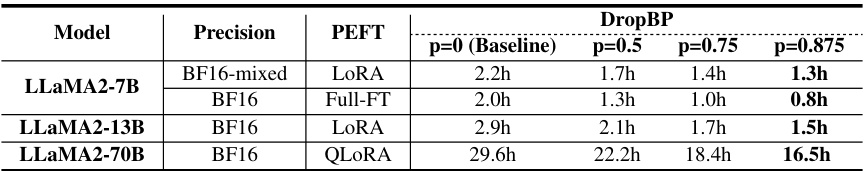

This table shows the time taken to fine-tune three different sizes of LLaMA2 models (7B, 13B, and 70B parameters) using different parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods (LoRA and Full-FT) with various DropBP drop rates (p=0, 0.5, 0.75, 0.875). The baseline (p=0) represents the training time without DropBP. The table highlights the significant reduction in training time achieved by DropBP, particularly at higher drop rates.

This table shows the maximum sequence length achievable when fine-tuning the LLaMA2-70B model using QLoRA with DropBP on a single NVIDIA A100 GPU. The experiment was conducted with a micro-batch size of 1. The results demonstrate a significant increase in maximum sequence length as the DropBP rate increases, highlighting the memory efficiency gains from employing DropBP.

This table compares the number of submodules trained and the accuracy achieved on the 5-shot Massive Multitask Language Understanding (MMLU) benchmark when using Layer Freezing and DropBP for fine-tuning LLAMA2-7B and LLAMA2-70B models on the Alpaca dataset. It shows that DropBP, despite dropping layers during backward propagation, maintains comparable accuracy to the baseline while training a significantly larger number of submodules compared to the layer freezing method. This is particularly evident in the larger LLAMA2-70B model.

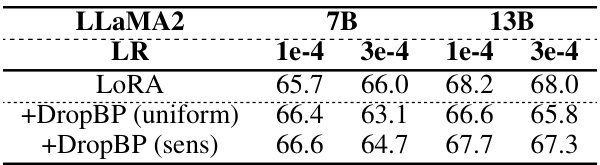

This table presents the results of 0-shot commonsense reasoning tasks using LLaMA2-7B and 13B models fine-tuned with LoRA and DropBP. It compares the accuracy achieved with uniform versus sensitivity-based drop rate allocation in DropBP at a target average drop rate of 0.875 on the Alpaca dataset. Different learning rates (LR) are also tested to assess performance variation.

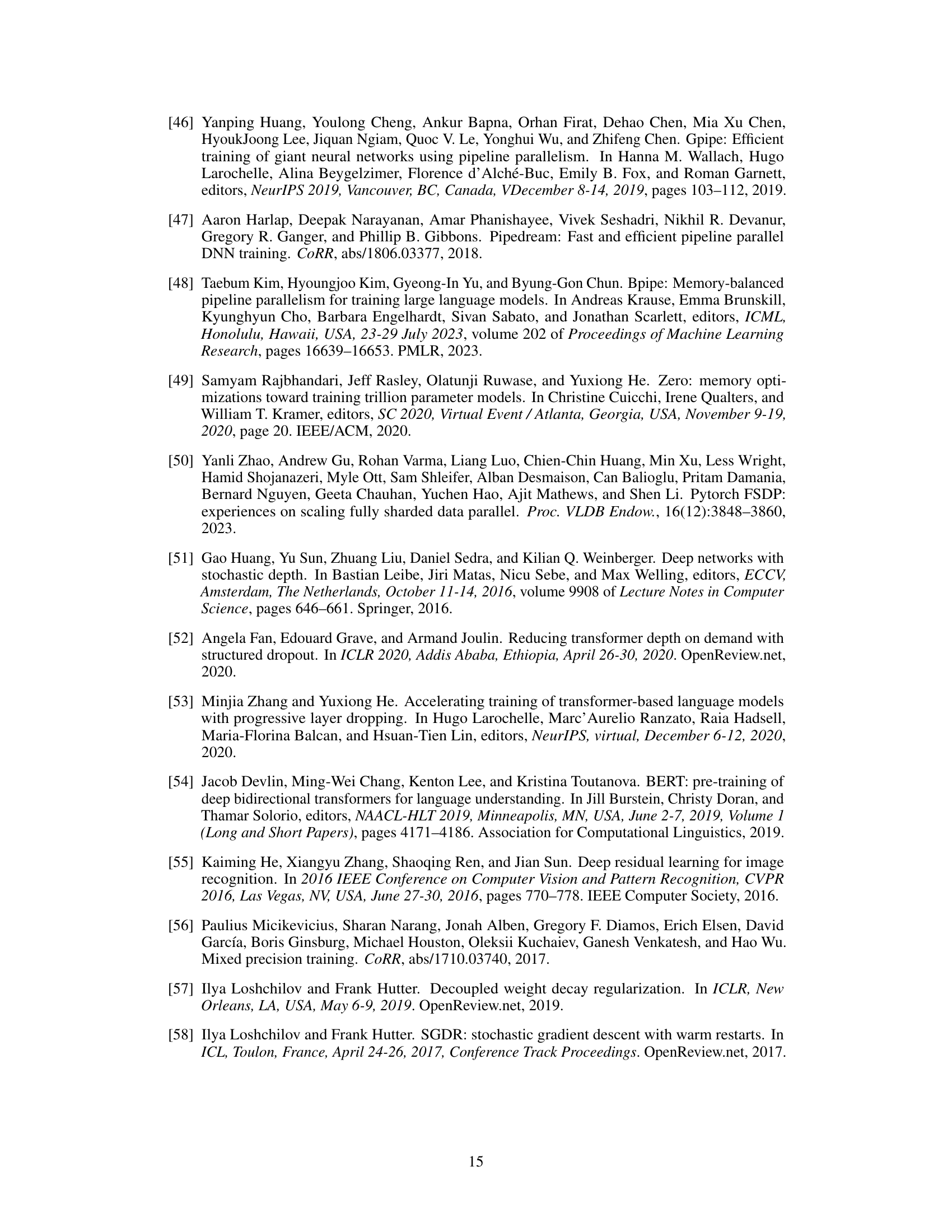

This table presents the training time per iteration in milliseconds (ms) for different model sizes (LLaMA2-7B, LLaMA2-13B, LLaMA2-70B) and fine-tuning methods (Full-FT, LORA, QLORA). It shows the impact of DropBP on training time by comparing the time taken with different drop rates (0, 0.5, 0.75, 0.875). The columns specify whether mixed precision training was used, micro batch size, forward propagation time, backward propagation time, and total time. The percentage reduction in backward propagation (BW) and total training time is indicated in parenthesis for each drop rate.

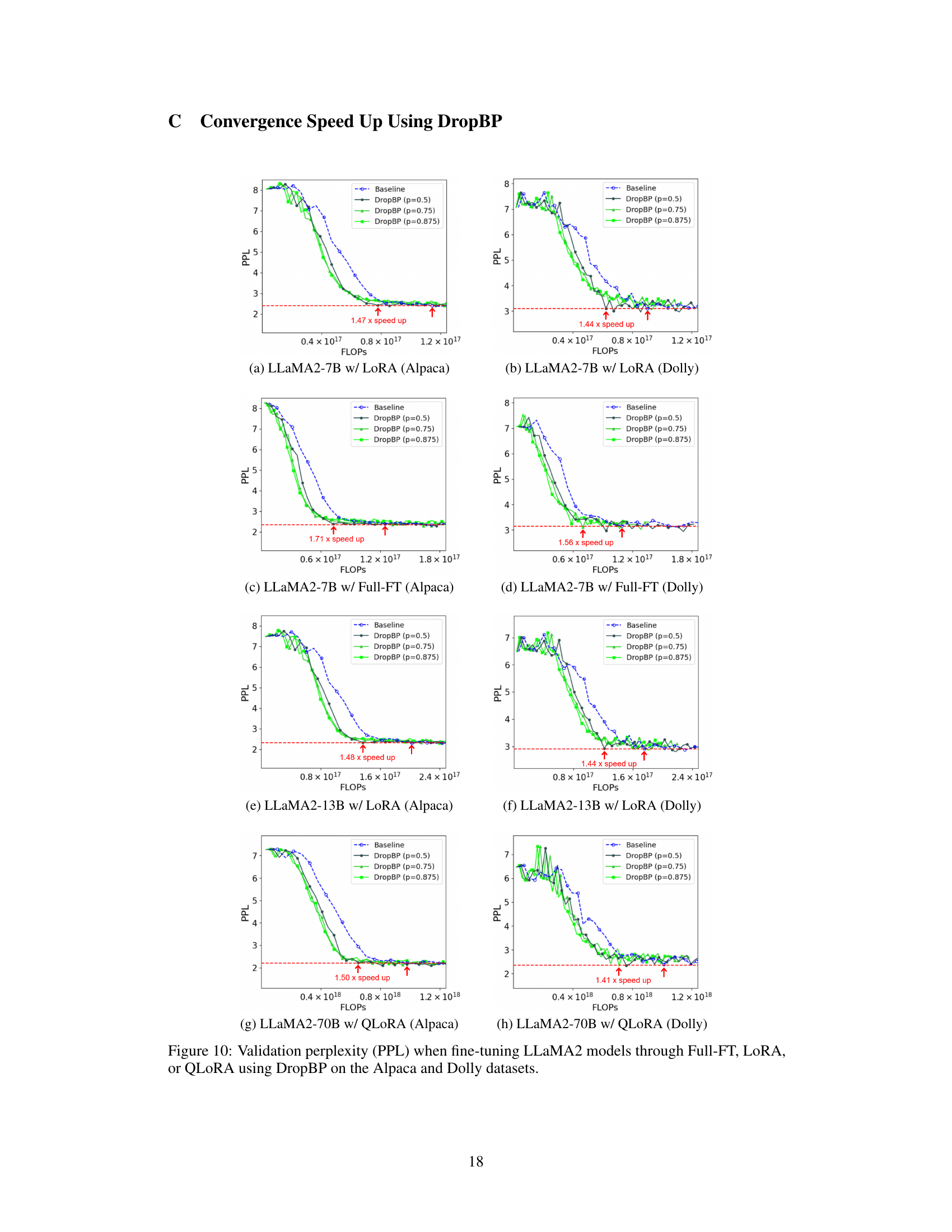

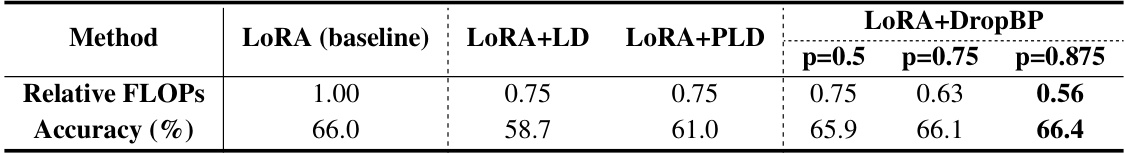

This table compares the performance of three different layer dropping methods (LayerDrop, Progressive Layer Drop, and DropBP) against a baseline LoRA model on a 0-shot commonsense reasoning task. It shows the relative FLOPs (floating point operations) and accuracy for each method, highlighting DropBP’s ability to maintain high accuracy even with significantly reduced FLOPs compared to the other layer dropping methods.

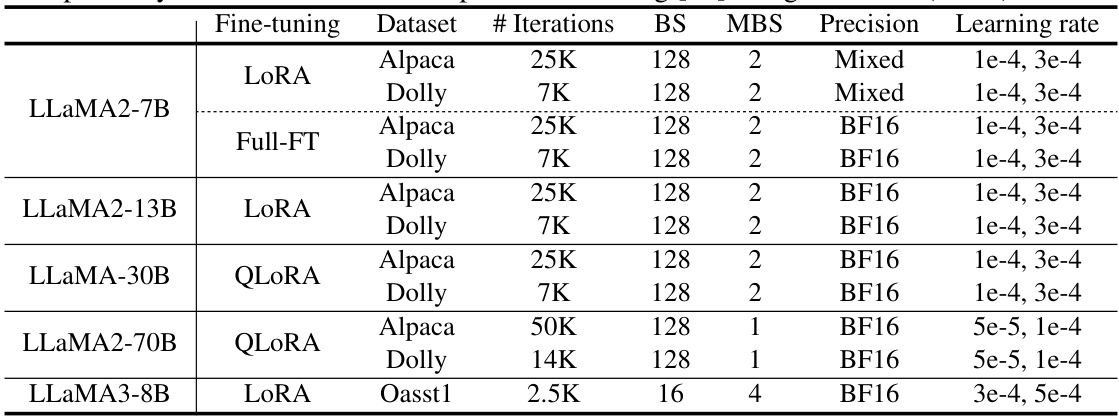

This table shows the detailed hyperparameter settings used for the experiments reported in Table 1 and 2 of the paper. It lists the fine-tuning method (LoRA, Full-FT, QLoRA), the dataset used (Alpaca, Dolly, Oasst1), the number of training iterations, batch size (BS), micro-batch size (MBS), precision (Mixed or BF16), and the learning rate range used for each experiment.

Full paper#