↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Graph generation models have struggled with either order sensitivity (autoregressive models) or inefficiency (diffusion models). Current graph diffusion models also require extra features and numerous steps for optimal performance. This creates a need for models that combine the advantages of both approaches.

PARD (Permutation-invariant AutoRegressive Diffusion) directly addresses this by integrating diffusion and autoregressive methods. It cleverly leverages a unique partial node order within graphs to generate them block-by-block in an autoregressive manner. Each block’s probability is modeled using a shared diffusion model with an equivariant network, ensuring permutation invariance. A higher-order graph transformer further enhances efficiency and expressiveness, leading to state-of-the-art results on various benchmark datasets without needing any extra features. This approach is scalable to large datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents PARD, a novel approach to graph generation that significantly improves upon existing methods. Its permutation-invariant nature addresses a critical limitation in previous autoregressive models and its efficiency opens doors to larger, more complex graph datasets. The proposed higher-order graph transformer offers enhanced expressiveness while improving memory efficiency, providing a valuable contribution to the field of graph neural networks. The results demonstrate state-of-the-art performance across several benchmarks, highlighting the potential of PARD for diverse applications.

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the two main components of the PARD model. The top part shows how the autoregressive method decomposes the joint probability distribution of a graph into a series of conditional distributions, one for each block of nodes. The bottom part shows how a shared discrete diffusion model is used to model each of these conditional distributions. The diffusion model injects noise into the graph, and then a denoising network is used to reconstruct the original graph from the noisy version. The process is repeated until the original graph is reconstructed.

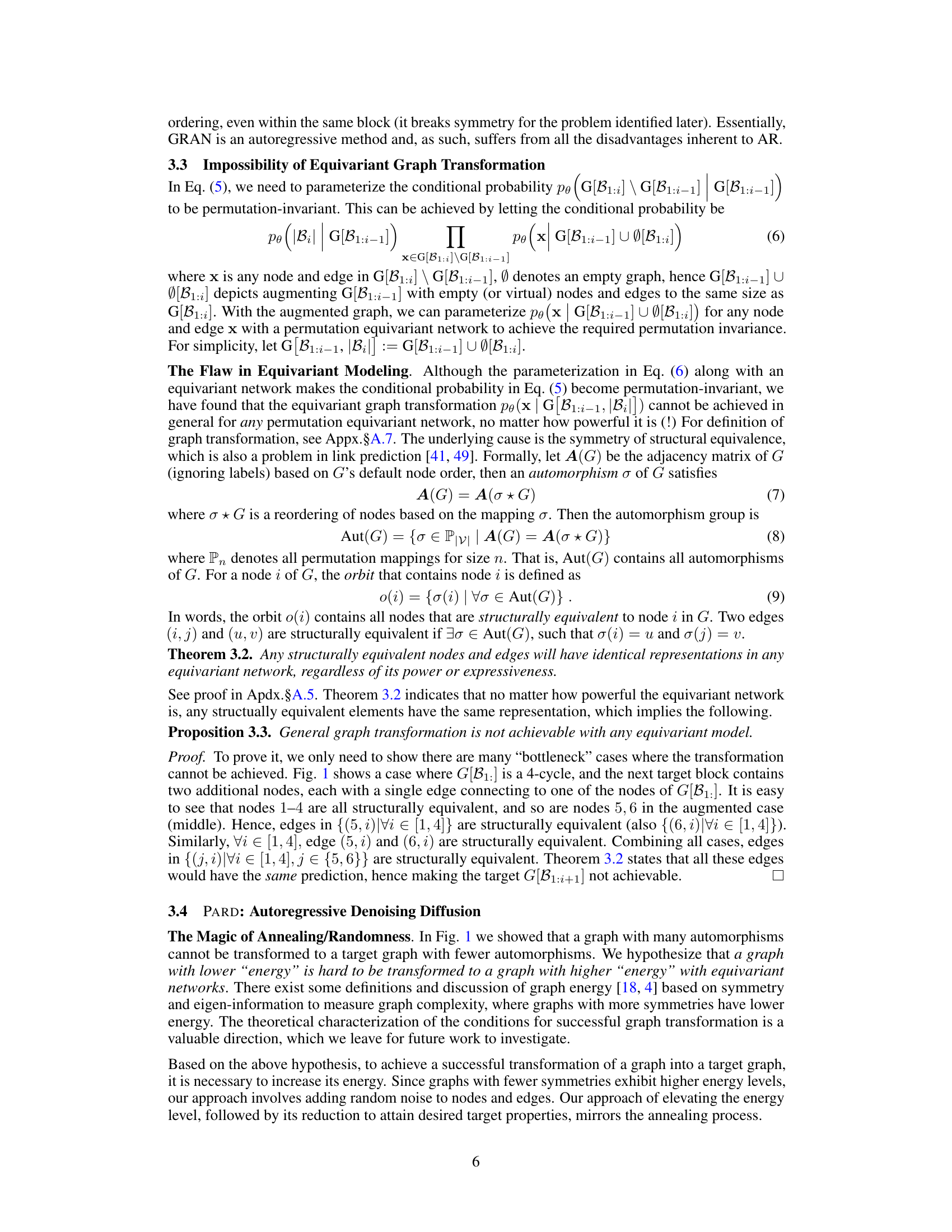

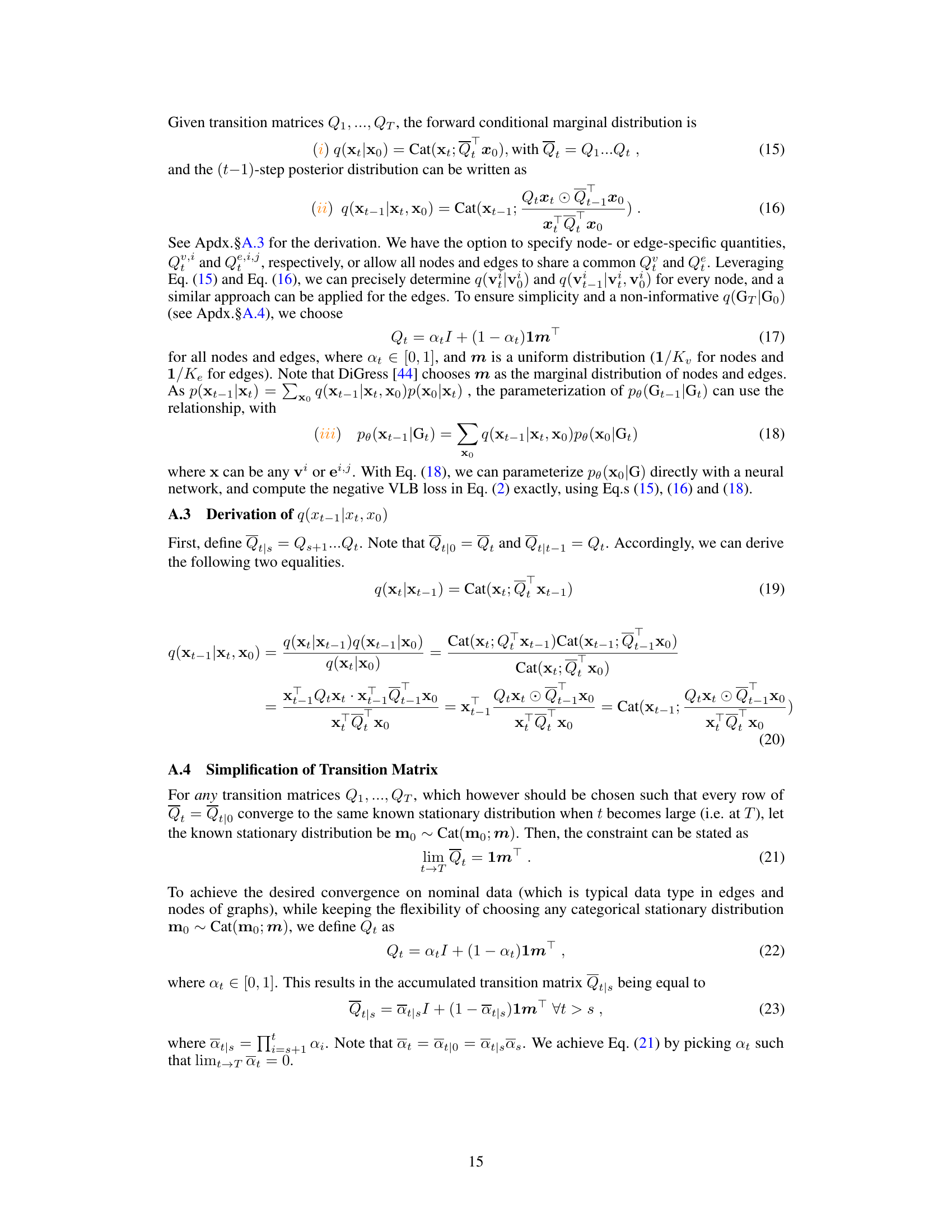

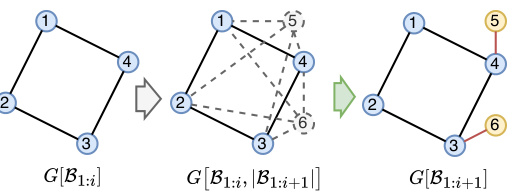

This table presents the performance of various models on the QM9 dataset, specifically focusing on the generation quality of molecules with explicit hydrogens. The metrics used to evaluate the models are Validity, Uniqueness, Atom Stability, and Molecular Stability. The results are compared against an optimal dataset, indicating how well each model achieves the desired properties. The table highlights PARD’s performance compared to other methods, including DiGress with various configurations and ConGress.

In-depth insights#

Permutation Invariance#

Permutation invariance is a crucial concept in graph neural networks (GNNs) and graph generative models. It addresses the inherent unordered nature of graph data, where the same graph can be represented in numerous ways depending on node ordering. Truly permutation-invariant models treat all node orderings as equivalent, ensuring that the model’s output is independent of the input ordering. This is particularly valuable for graph generation, where node ordering is arbitrary and shouldn’t influence the graph’s properties. Achieving permutation invariance poses a significant challenge because most GNNs rely on node ordering in their message-passing schemes, implicitly introducing bias. The paper explores various methods to address this, including diffusion models and autoregressive approaches, highlighting the tradeoffs between permutation invariance, efficiency, and expressive power. A key focus is on combining the strengths of both techniques, leveraging the permutation invariance of diffusion models and the efficiency of autoregressive generation. The effectiveness of the proposed method is demonstrated empirically through state-of-the-art performance on various benchmark datasets. The discussion also includes theoretical analysis to support the claim of permutation invariance and the limitations of various approaches.

Diffusion Model Fusion#

Diffusion models have emerged as powerful generative models, but their application to graph generation faces challenges due to the inherent complexity of graph structures and the need for permutation invariance. Diffusion Model Fusion strategies aim to address these issues by combining the strengths of diffusion models with other techniques, leveraging the permutation invariance of diffusion while mitigating its limitations, such as the computational cost of numerous denoising steps. One promising direction involves incorporating autoregressive methods. Autoregressive models excel at generating sequential data, offering a natural way to construct graphs step-by-step, maintaining permutation invariance and reducing the computational burden. A key advantage is that the fusion approach can potentially lead to higher-quality graph generation by combining both the strengths of efficiency from autoregressive models and the permutation-invariance from diffusion models. Another approach involves fusing diffusion with equivariant neural networks to better capture the structural properties of graphs while preserving permutation invariance. This fusion may help reduce the high dimensional complexity associated with direct graph modeling. The success of diffusion model fusion hinges on careful consideration of the order of operations to ensure the benefits of both methods are fully utilized. Proper design of the fusion architecture and training methodology are crucial for effective graph generation.

Higher-Order Graphs#

Higher-order graph concepts move beyond pairwise relationships to capture richer interactions. Instead of just edges connecting nodes, higher-order structures like triangles or cliques are explicitly considered. This shift is crucial because many real-world systems exhibit complex interactions that cannot be adequately represented by simple graphs. For instance, in social networks, a higher-order structure like a triad (three people mutually connected) might reveal more about group dynamics than individual connections alone. Modeling these higher-order structures can lead to more accurate predictions, improved graph generation, and a deeper understanding of the underlying system. Algorithmic challenges arise in representing and processing such structures efficiently, as the complexity grows rapidly with the order. The benefits, however, include improved accuracy and generalization in tasks like graph classification and link prediction, where higher-order information can be powerful discriminatory factors.

Autoregressive Approach#

Autoregressive models offer a powerful approach to graph generation by sequentially adding nodes and edges, thus leveraging the efficiency of conditional probability modeling. However, a critical limitation is their inherent sensitivity to node ordering, which compromises their ability to generate permutation-invariant graphs. The core challenge lies in defining a consistent, meaningful node ordering that does not bias the resulting graph distribution. Several methods attempt to mitigate this issue by introducing randomized or deterministic ordering strategies, or by explicitly modeling the probability of different orderings. Despite these advances, these approaches often involve approximations or increase computational complexity. Ideally, an autoregressive approach should inherently be permutation-invariant, avoiding the need for order-based heuristics or approximations. This is crucial for ensuring generalizability and accuracy, particularly when dealing with large, complex graph structures. The potential of autoregressive methods remains significant due to their efficiency and interpretability, however overcoming their order sensitivity remains a key research challenge.

Scalability Challenges#

Scalability is a critical concern in graph generation models, particularly for large datasets. Autoregressive models, while effective, often struggle with scalability due to their sequential nature, making parallel processing difficult. Diffusion models, while permutation-invariant, often demand extensive computational resources, involving thousands of denoising steps, which hinder their scalability. The trade-off between expressiveness and computational efficiency is significant, and many models rely on approximations or extra features to balance the two, but these can limit generalization. Therefore, achieving scalability often involves architectural optimizations such as block-wise processing and parallel training mechanisms. Higher-order graph transformers are promising in this respect, offering increased expressivity with relatively lower memory footprint, but their potential for further scalability enhancements warrants further investigation. Ultimately, developing efficient training strategies and leveraging parallel computing are key to building truly scalable graph generation models that can handle increasingly large and complex datasets.

More visual insights#

More on figures

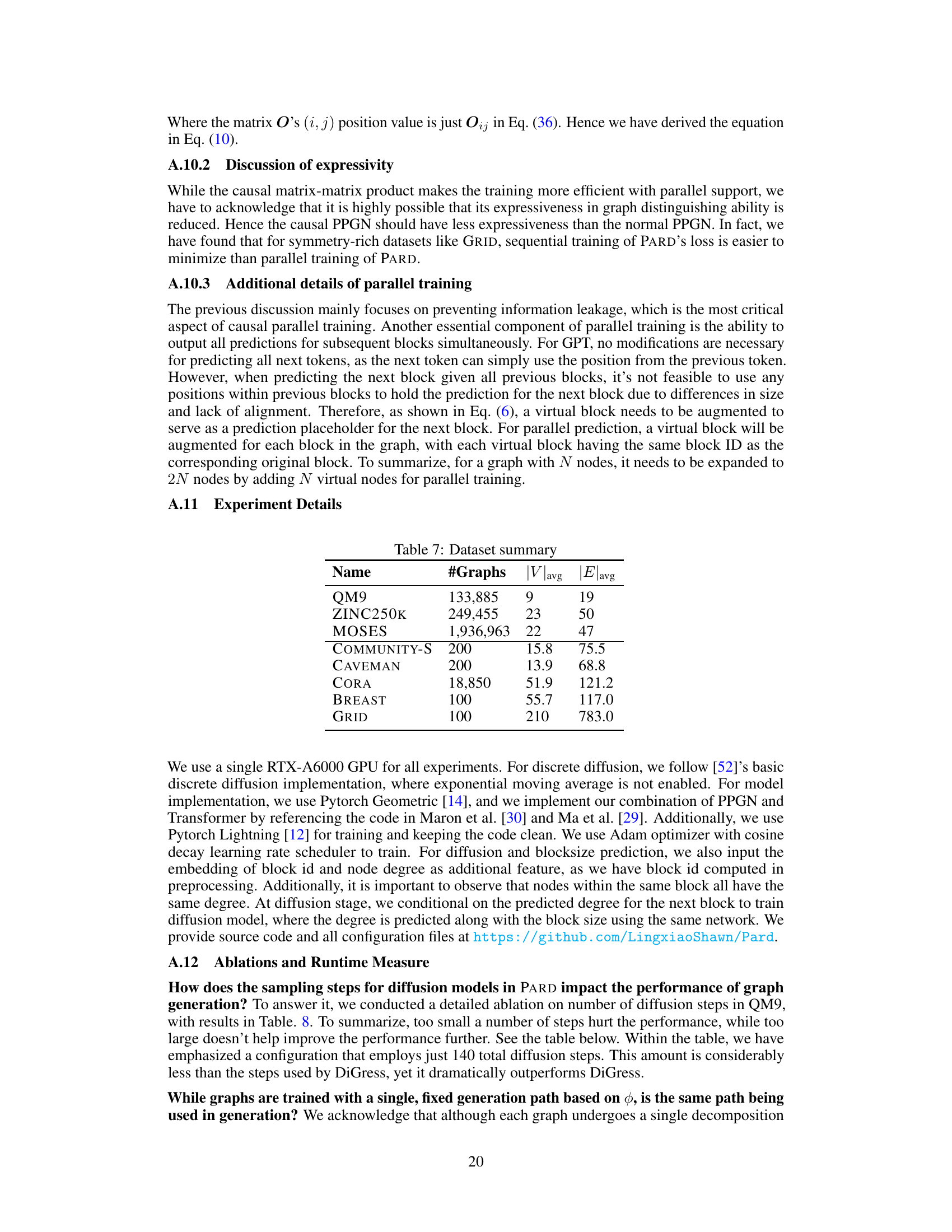

This figure illustrates the PARD model’s two main components: autoregressive block-wise generation and local denoising diffusion. The top part shows how the model generates a graph block by block, adding new nodes and edges in each step. The bottom shows how, within each block, a discrete diffusion model is used to refine the generation, gradually removing noise until a complete block is formed. This combines the efficiency of autoregressive methods with the quality of diffusion models.

This figure illustrates the core idea of PARD, which combines autoregressive and diffusion models for graph generation. The top part shows how PARD decomposes the generation process into sequential blocks, adding nodes and edges one block at a time. The bottom part illustrates that, for each block, a shared discrete diffusion model is used to predict the conditional probability of adding those nodes and edges given the previously generated blocks.

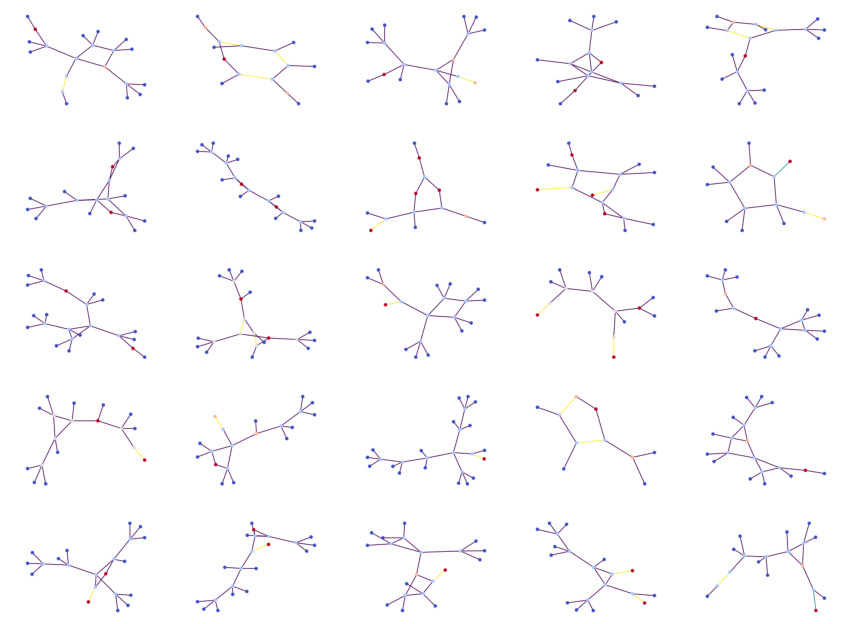

This figure shows 25 examples of molecular graphs generated by the PARD model trained on the QM9 dataset. Each graph represents a molecule, with nodes representing atoms and edges representing bonds between atoms. The color-coding of nodes might represent different types of atoms. The fact that these are ’non-curated’ suggests they are raw outputs of the model, without any post-processing or filtering for chemical validity or plausibility. The caption specifies that the model was trained using 20 denoising steps per block, referring to a parameter of the PARD algorithm’s block-wise graph generation process.

This figure illustrates the two main components of the PARD model. The top part shows how PARD decomposes the generation of a graph into a sequence of blocks, added one by one. The bottom part shows how a shared diffusion model is used to generate each block, conditioned on the previously generated blocks. This combination of autoregressive and diffusion modeling is key to PARD’s permutation invariance and efficiency.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the PARD model, highlighting the integration of autoregressive and diffusion models. The top part shows how the model generates graphs block by block. The bottom part shows how a diffusion model is used to model the conditional distribution of each block, ensuring permutation invariance. The combination of autoregressive and diffusion methods enables PARD to achieve efficient and high-quality graph generation.

More on tables

This table presents the performance of various graph generation models on the ZINC250K dataset. The metrics used to evaluate the models include Validity (the percentage of generated molecules that are valid chemical structures), Fréchet ChemNet Distance (FCD, a lower score indicates better similarity to real molecules), Uniqueness (the percentage of unique molecules generated), and Model Size (the number of parameters in the model). The table compares PARD’s performance against several baseline models, highlighting PARD’s superior performance in terms of Uniqueness and FCD, while also showing a relatively small model size compared to some competitors.

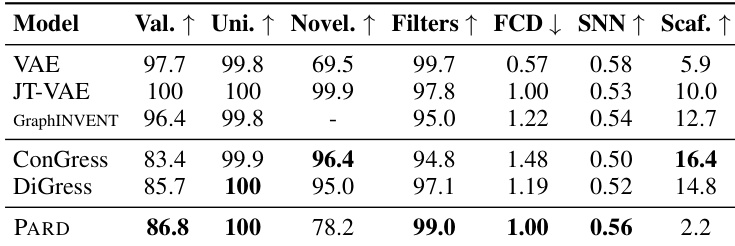

This table presents the performance of various graph generation models on the MOSES dataset. The metrics used to evaluate the models include Validity (the percentage of generated graphs that are valid molecules), Uniqueness (the percentage of valid molecules that are unique), Novelty (the percentage of valid molecules that are novel and not present in the training set), Filters (a metric specific to the MOSES dataset measuring the fraction of generated molecules that pass standard filters used for the test set), Fréchet ChemNet Distance (FCD) (a measure of similarity between generated and training molecules, lower is better), SNN (a measure of nearest neighbor similarity using Tanimoto Distance), and Scaffold (a measure of the frequency of Bemis-Murcko scaffolds in the generated molecules). Note that the top three models, not highlighted in the table, employ hard-coded rules for generation, whereas the remaining models are general-purpose generative models. This allows for a comparison of PARD’s performance against specialized and general-purpose models.

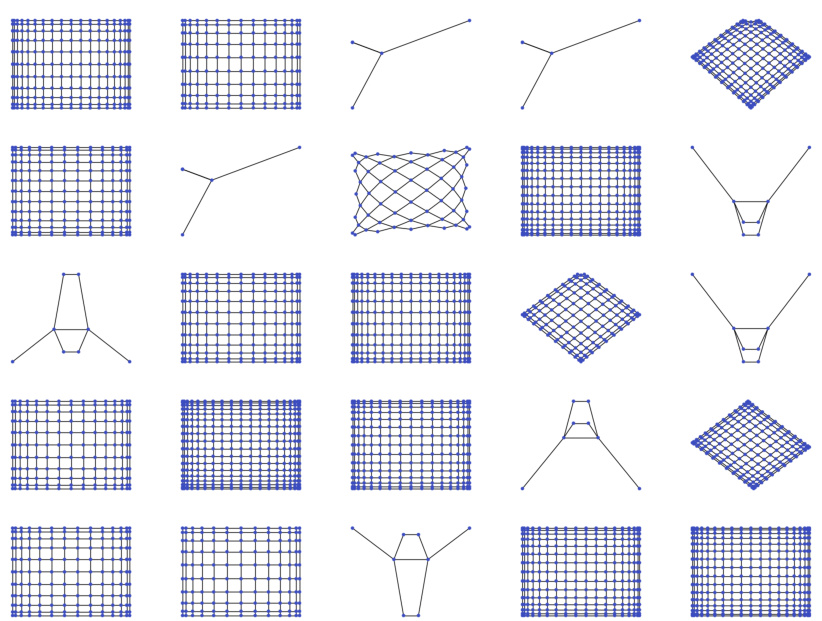

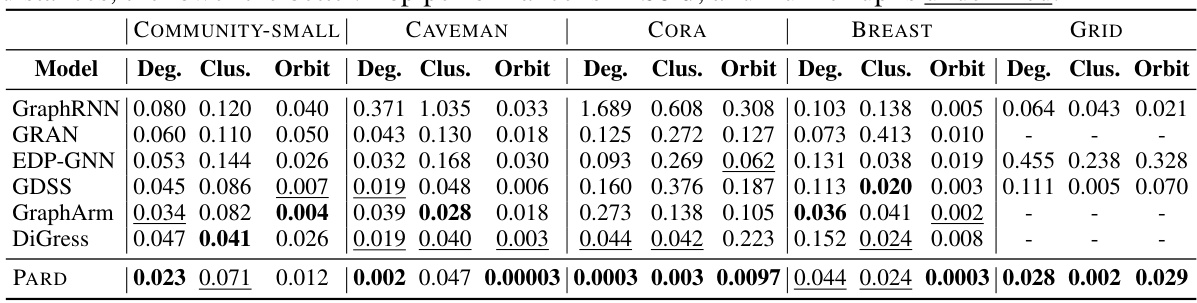

This table presents the performance of different graph generation models on five generic graph datasets: COMMUNITY-SMALL, CAVEMAN, CORA, BREAST, and GRID. The models are evaluated using three metrics: Degree, Clustering, and Orbit, each calculated as the Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) between the generated graphs and the test graphs. Lower MMD scores indicate better performance, with the best scores shown in bold and the second-best underlined. The table shows that PARD generally outperforms the other methods across the datasets and metrics.

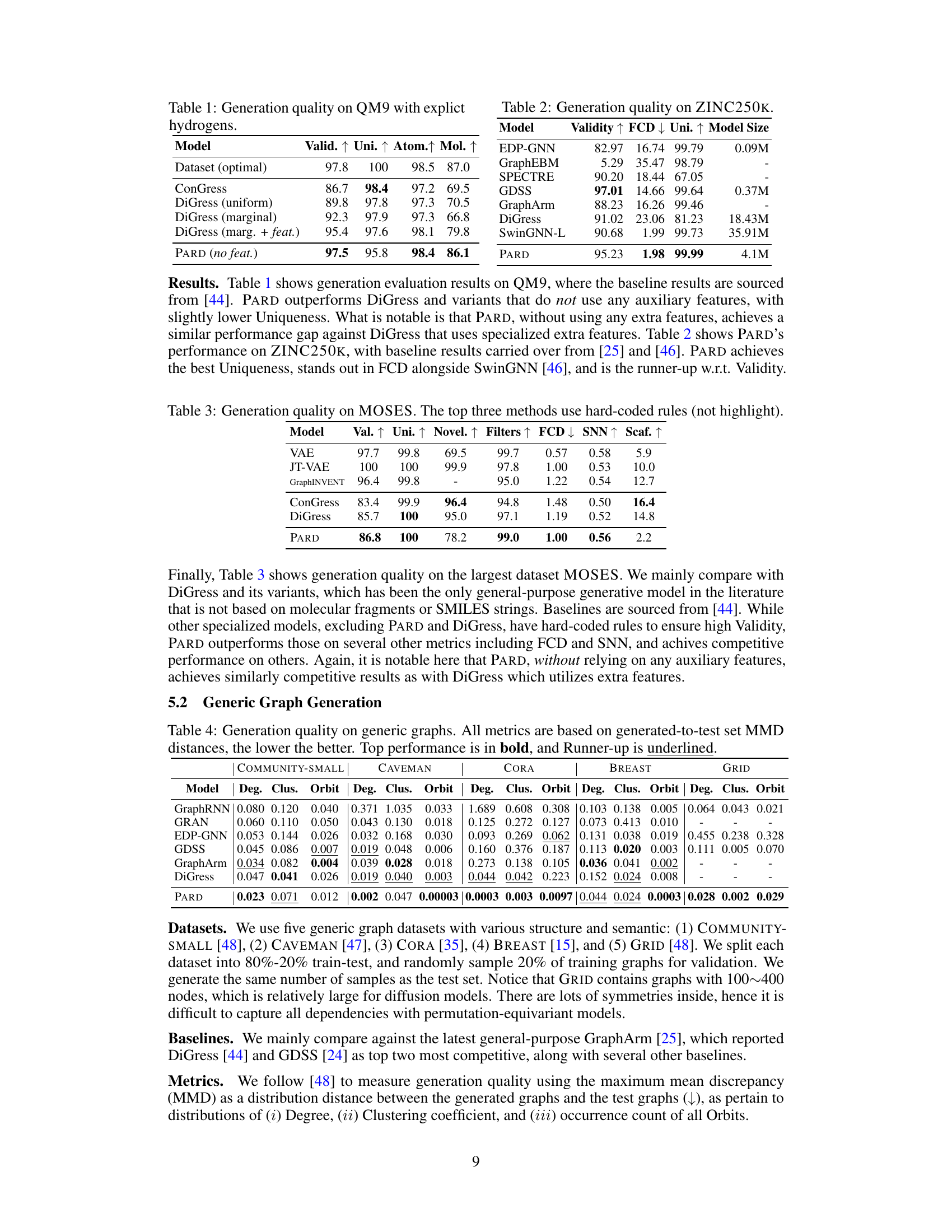

This ablation study investigates the impact of autoregressive (AR) components on the performance of the diffusion model. It compares three settings: no AR (pure diffusion), AR with varying maximum hops (controlling the number of blocks), and no AR with increased diffusion steps. The results show the effect of AR on validity, uniqueness, molecular stability, and atom stability metrics on the QM9 dataset. The increase in performance with AR demonstrates its effectiveness in improving graph generation.

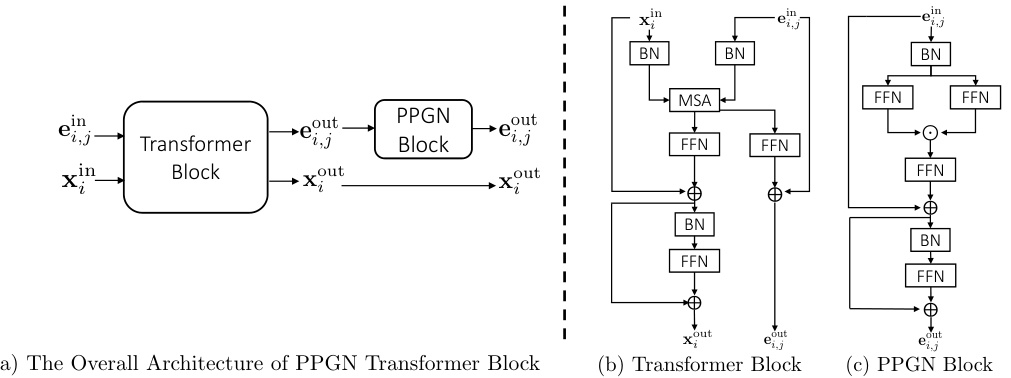

This table presents the ablation study results on the QM9 dataset using different model architectures: Transformer, PPGN, and PPGNTransformer. Kh (maximum hops) is set to 3, and the total number of diffusion steps is 140. The table compares the performance of these architectures across four metrics: Validity, Uniqueness, Molecular Stability, and Atomic Stability. The results demonstrate the impact of architectural choices on the performance of the graph generation model.

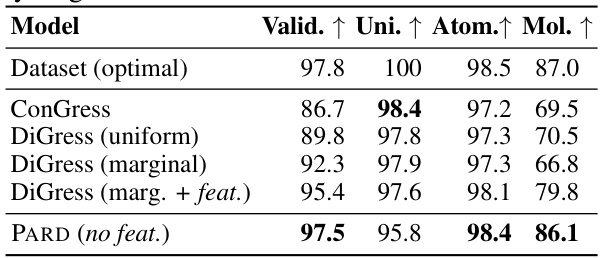

This table summarizes the eight benchmark datasets used in the paper’s experiments. For each dataset, it provides the number of graphs, the average number of nodes (|V|avg), and the average number of edges (|E|avg). The datasets include both molecular datasets (QM9, ZINC250K, MOSES) and generic graph datasets (COMMUNITY-S, CAVEMAN, CORA, BREAST, GRID).

This ablation study on the QM9 dataset investigates the impact of varying the number of diffusion steps per block and the total number of diffusion steps on the model’s performance. The results show that increasing the total number of diffusion steps generally improves performance, but only up to a certain point. The best performance is achieved with a total of 140 diffusion steps, which is far less than the 500 steps used by DiGress. The table compares the performance of PARD across different configurations with DiGress’s results.

This table presents an ablation study on the QM9 dataset, comparing the performance of PARD with different numbers of diffusion steps per block and total diffusion steps. It demonstrates the effect of varying the number of autoregressive steps on the overall model performance, highlighting the trade-off between autoregression and diffusion. The results show that increasing the number of steps, up to a point, generally improves model performance across several metrics.

This table compares the performance of different diffusion models (EDP-GNN, GDSS, PARD, and PARD with EigenVec.) on the GRID dataset, in terms of three metrics: Degree, Clustering, and Orbit. Lower values are better, indicating better model performance.

Full paper#