↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are increasingly used for complex tasks, but their ability to learn compositional structures remains unclear. This study investigates the sample efficiency of LLMs in learning compositional tasks by training LLMs on four carefully designed tasks that demand a composition of discrete sub-tasks. The main challenge addressed is how well LLMs can reuse knowledge acquired during the training of the individual sub-tasks to improve the efficiency of learning compositional tasks.

The researchers found that LLMs are highly sample-inefficient in compositional learning. LLaMA models, for example, required significantly more data samples to learn the compositional tasks than was needed to relearn the individual sub-tasks from scratch. In-context prompting showed similar inefficiencies, with limited success in solving compositional tasks. Furthermore, theoretical analysis supports these findings, highlighting the limitations of gradient descent training for memorizing compositional structures.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs) because it reveals significant limitations in LLMs’ ability to perform compositional tasks. The findings challenge the common assumption of LLMs’ inherent compositional capabilities, prompting a reevaluation of LLM architectures and training methods. This opens new avenues of research towards creating more efficient and truly compositional AI systems. It also provides a theoretical framework for analyzing sample efficiency in compositional learning, advancing our understanding of the limitations of gradient descent training.

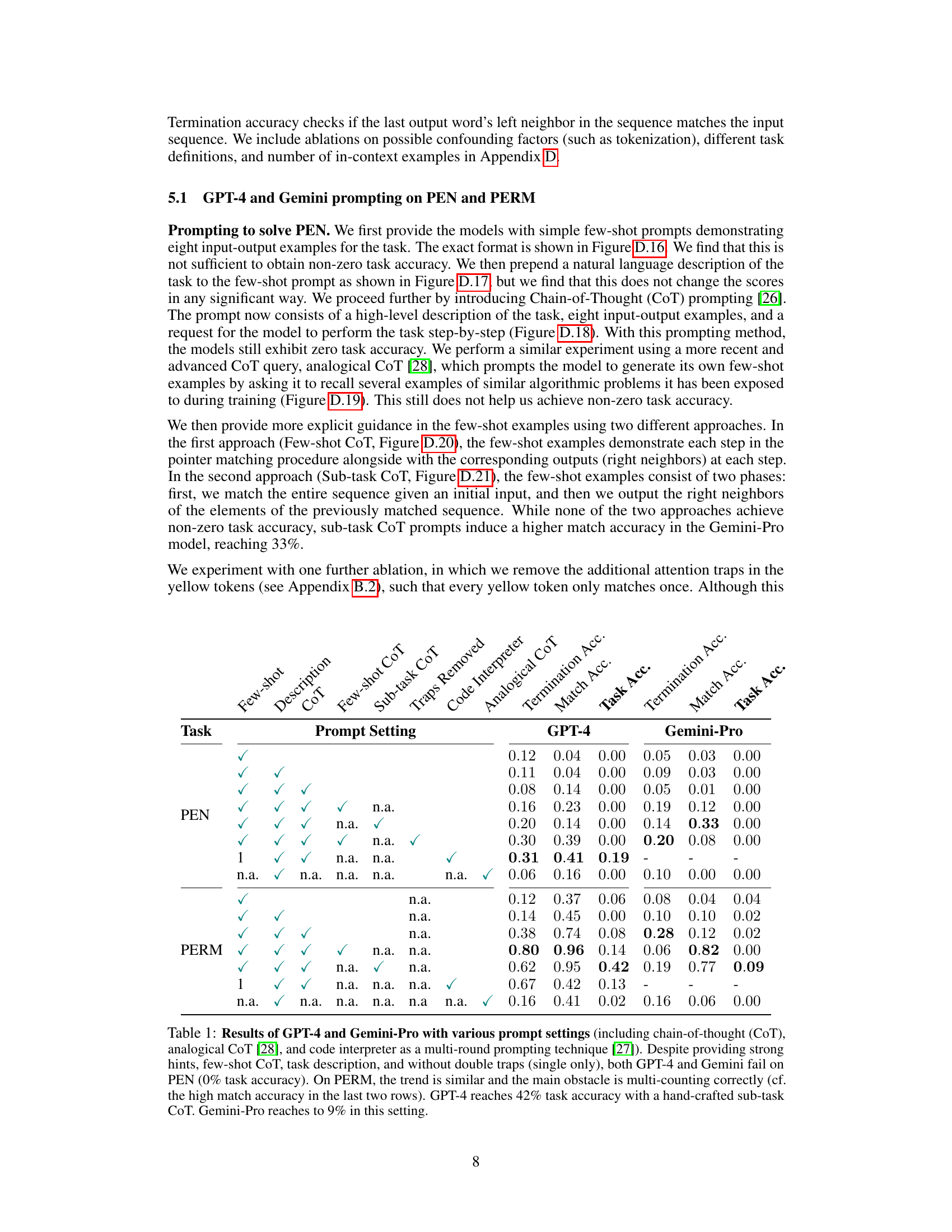

Visual Insights#

This figure shows a visualization of how a compositional algorithmic task, specifically the PEN task, can be represented as a computational graph. The PEN task involves processing a sequence of words by jumping between different words according to a matching criterion and outputting their neighbors. The graph illustrates the task’s structure, where nodes represent intermediate variables and edges represent primitive operations. The color coding helps match the operations in the graph to their corresponding steps in the PEN task’s pseudo-code. It highlights the relationships between primitive operations (left, match, right) and the overall compositional structure of the task.

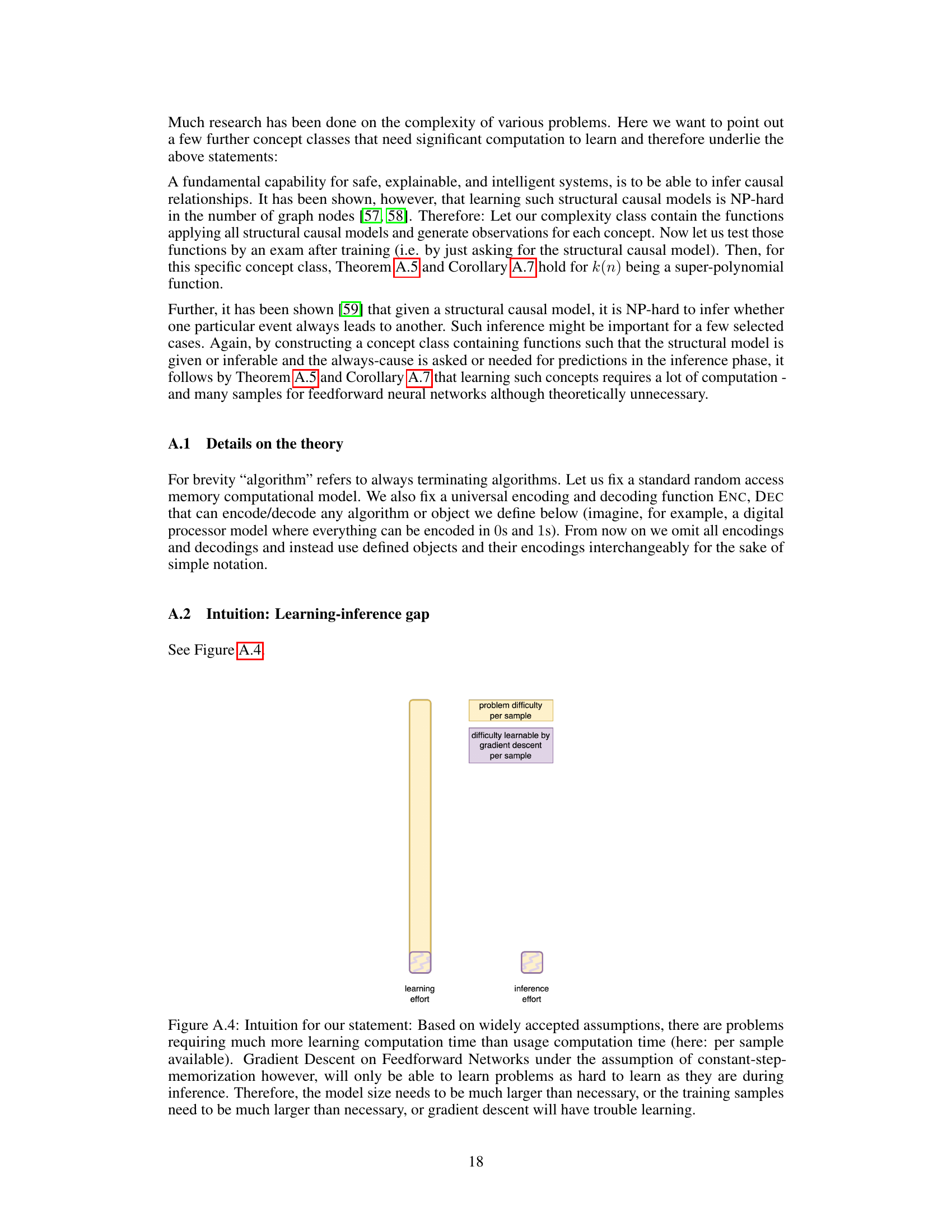

This table summarizes the results of experiments using GPT-4 and Gemini-Pro on two algorithmic tasks, PEN and PERM, with various prompting methods. The results show that even with detailed prompts and chain-of-thought prompting, both models struggle to achieve high accuracy. The main challenge seems to be in composing multiple sub-tasks required for the overall task. Hand-crafted, sub-task-based prompting provides slightly better performance, particularly for GPT-4.

In-depth insights#

LLM Composition Limits#

The study of “LLM Composition Limits” reveals crucial insights into the capabilities and constraints of large language models (LLMs) in handling compositional tasks. The research highlights the significant sample inefficiency of current LLMs in learning compositional algorithms, requiring substantially more data than learning individual sub-tasks. This challenges the assumption that LLMs effortlessly generalize to complex tasks. The findings underscore a memorization-based learning behavior in LLMs, as they struggle to reuse previously learned components rather than compositionally constructing solutions. This limited ability to generalize has practical implications for LLM applications, indicating a need for more sophisticated training methods or architectural designs to mitigate this critical limitation. Theoretical analysis using complexity theory strengthens these empirical findings by showing how the sample inefficiency is an inherent characteristic of gradient descent in memorizing feedforward models. This suggests that fundamentally new approaches may be necessary to fully unleash the compositional power of LLMs.

Algorithmic Task Design#

Effective algorithmic task design is crucial for evaluating compositional learning in large language models (LLMs). Well-designed tasks should possess a clear compositional structure, allowing for the decomposition into smaller, independently solvable sub-tasks. This modularity enables a nuanced analysis of the LLM’s ability to reuse learned primitives when tackling the complete task, separating genuine compositional generalization from superficial pattern-matching. Synthetic tasks offer a level of control to minimize confounding factors, but ideally, these tasks should also reflect real-world problem characteristics to ensure practical relevance. The selection of primitive operations used in the sub-tasks needs careful consideration. A balanced choice between simplistic, easily learnable primitives, and more complex primitives that require more substantial learning effort can highlight the model’s ability to generalize beyond simple memorization. The overall design must also consider the sample efficiency of the task. A computationally efficient task may be less demanding of resources, and an efficient task design that reduces sample size is beneficial for both research and practical applications.

Sample Inefficiency#

The research paper reveals a critical limitation of Transformer Language Models (LLMs) in compositional learning: sample inefficiency. This means LLMs require significantly more training data than expected to learn compositional tasks, even when their constituent sub-tasks are already mastered. The inefficiency is striking; models need more examples than those needed to train the sub-tasks from scratch. This challenges the hypothesis that LLMs learn compositionally, suggesting that they primarily memorize individual sequences instead of abstracting and recombining fundamental rules. This inefficiency is further supported by a theoretical analysis, proving that gradient descent in feedforward models suffers from inherent sample inefficiency in memorizing solutions to combinatorial problems. The results highlight a crucial barrier to creating more advanced, generalizable AI systems and underscore the need for developing new training methods to overcome this limitation.

In-context Prompting Fails#

The failure of in-context prompting in compositional algorithmic tasks highlights a critical limitation of current large language models (LLMs). While LLMs excel at pattern recognition and leveraging existing knowledge from massive datasets, they struggle to generalize and compose knowledge in novel, unseen scenarios presented by these tasks. The experiments demonstrate that simply providing a few examples or a detailed task description is insufficient to enable LLMs to effectively break down complex tasks into smaller sub-tasks and recombine their solutions. This failure underscores a lack of true understanding and reasoning abilities and reveals a significant gap between the impressive capabilities of LLMs and the requirements for robust, generalizable AI. The inherent sample inefficiency revealed suggests a need for new learning paradigms beyond simple in-context prompting that encourage generalization and compositionality. This necessitates a shift towards methods that enable models to learn abstract rules and principles, instead of relying heavily on statistical correlations in the training data.

Future Research#

Future research should prioritize developing more effective methods for inducing compositional learning in LLMs. This could involve incorporating stronger inductive biases into model architectures or modifying training procedures to better encourage the reuse of learned sub-tasks. Expanding the range of benchmark tasks beyond the currently used synthetic examples is crucial to ensure broader generalizability and robustness of findings. Investigating the interplay between model size, data efficiency, and training strategies is another vital direction, particularly in the context of limited data scenarios. A deeper theoretical understanding of compositional learning within the framework of gradient descent is needed, perhaps exploring alternative optimization techniques that could mitigate the sample inefficiency observed in this work. Finally, more extensive investigation into the decomposability of existing tasks is needed, exploring whether pre-training on complex tasks aids in the efficient learning of simpler sub-tasks, and how such knowledge is subsequently leveraged for compositional generalization.

More visual insights#

More on figures

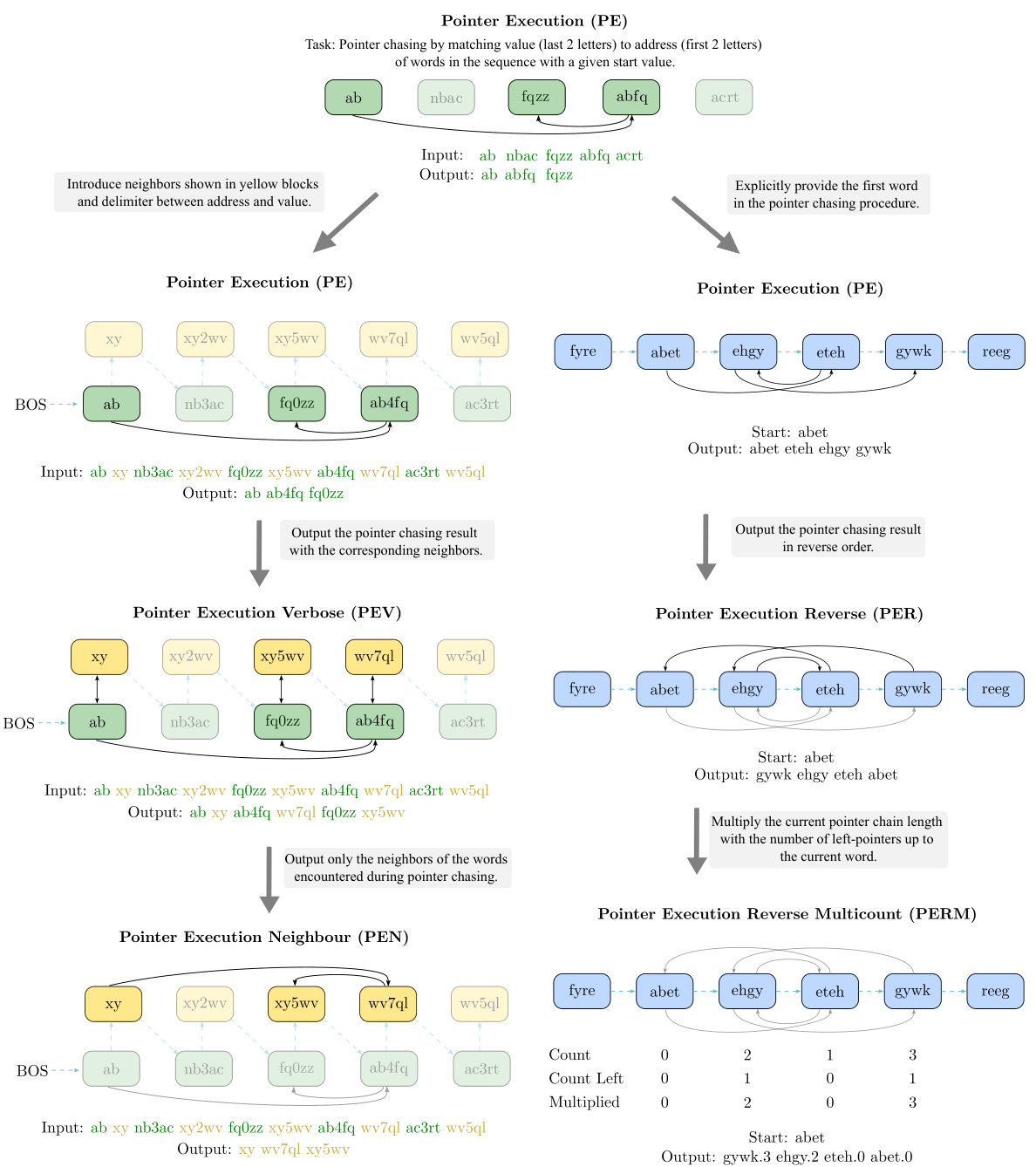

This figure illustrates two new algorithmic tasks introduced in the paper: Pointer Execution’s Neighbor (PEN) and Pointer Execution Reverse Multicount (PERM). The left side shows PEN and its related sub-tasks (PE, PEV, and RCpy), detailing how the algorithm progresses through a sequence of words based on matching criteria and retrieving neighbor words. The right side illustrates PERM and its sub-tasks (PE, PER, and PEM), highlighting how the algorithm matches a sequence, reverses it, and calculates a multicount value for each element based on match and left-match counts. The visual representation aids in understanding the compositional nature of the tasks and the independent observability of their primitive operations.

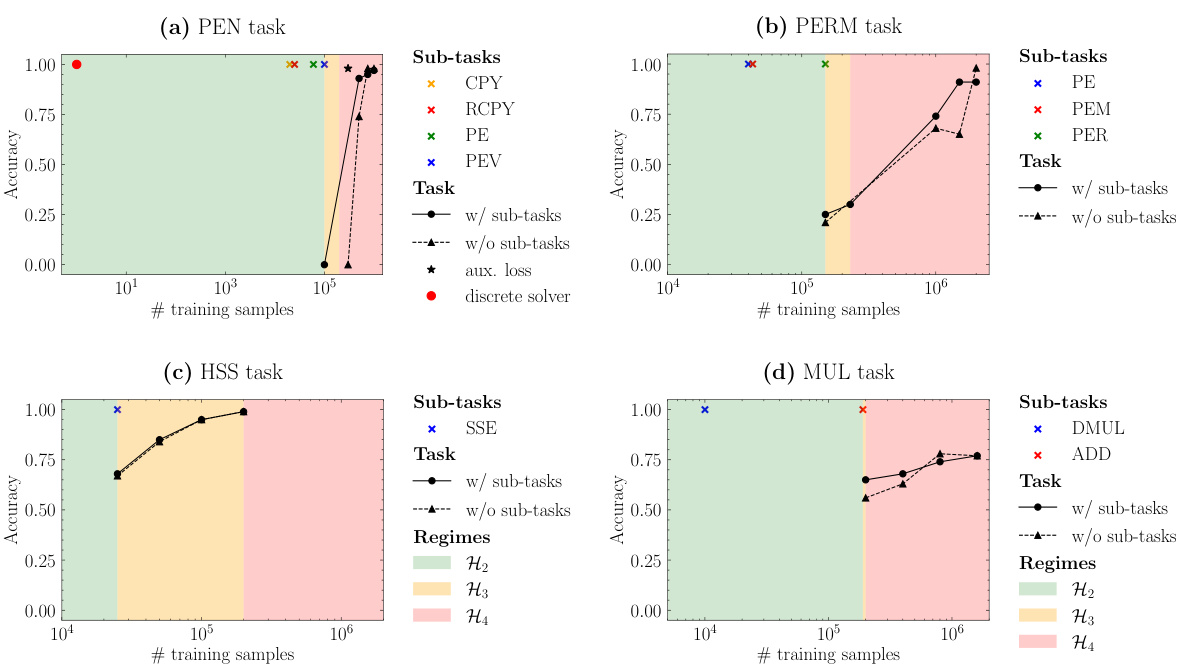

This figure shows the accuracy of LLaMA models on four compositional algorithmic tasks (PEN, PERM, HSS, and MUL) and their respective sub-tasks, plotted against the number of training samples. It demonstrates the sample inefficiency of LLMs in compositional learning, supporting the hypothesis that learning the composition of sub-tasks requires significantly more data than learning the individual sub-tasks. The colored regions represent different hypotheses about sample efficiency, with H4 (requiring more samples than the sum of samples needed for sub-tasks) being the most consistently observed result.

This figure illustrates the learning-inference gap discussed in the paper. It visually represents the difference between the complexity of learning a problem (high learning effort) compared to the complexity of performing the learned task once it’s acquired (low inference effort). The figure highlights that gradient descent on feedforward networks struggles to learn problems that are significantly more complex to learn than to perform (infer). The model’s capacity to memorize the training data limits its ability to generalize.

The figure shows the accuracy of LLaMA models (150M parameters) on four different compositional tasks (PEN, PERM, HSS, MUL) and their corresponding sub-tasks, as a function of training samples. Each task is broken down into multiple sub-tasks, with independently observable primitives, which allows to evaluate the model’s capacity to reuse and compose the sub-tasks’ knowledge. The results indicate that achieving high accuracy on the complete tasks necessitates significantly more training samples than needed to learn the individual sub-tasks, supporting the hypothesis that these models fail to learn compositionally.

This figure presents the results of training LLAMA models on four different tasks (PEN, PERM, HSS, and MUL) and their corresponding subtasks. The x-axis represents the number of training samples, while the y-axis shows the accuracy achieved on each task. The results demonstrate that LLAMA struggles with compositional learning, requiring significantly more data to learn the compositional tasks than to learn the individual subtasks. The figure highlights the significant sample inefficiency of LLAMA in compositional learning and supports hypothesis H4, indicating that learning a compositional task requires more samples than the sum of the samples needed to learn all the individual subtasks.

This figure illustrates two novel compositional algorithmic tasks introduced in the paper: Pointer Execution’s neighbor (PEN) and Pointer Execution Reverse Multicount (PERM). The left side shows PEN, decomposing it into sub-tasks (PE, PEV, Copy, Reverse Copy) to highlight the compositional nature of the task. The right side shows PERM with its sub-tasks (PE, PER, PEM), emphasizing how the task requires not only matching but also reverse ordering and counting operations. The figure uses color-coding and diagrams to visually represent the tasks and their respective sub-tasks.

This figure illustrates two newly introduced algorithmic tasks, PEN and PERM, designed to evaluate the compositionality of LLMs. The left panel depicts PEN, which involves matching words based on a substring criterion and outputting their neighbors, broken down into subtasks to highlight the composition. The right panel shows PERM, requiring matching, reversing, and multicounting steps within a sequence. Both tasks are represented visually as computational graphs, emphasizing the compositional nature of the problems.

More on tables

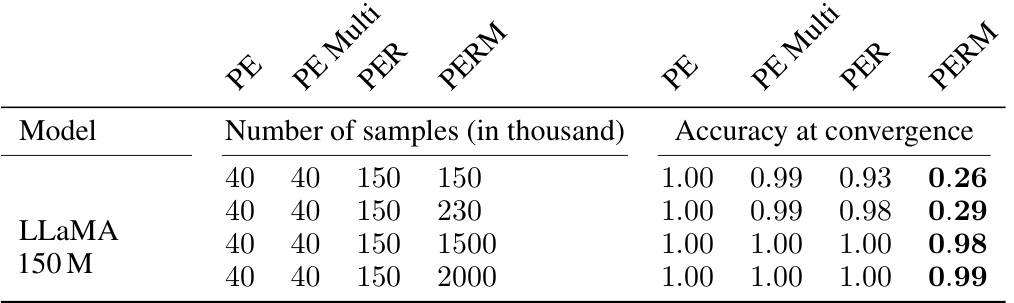

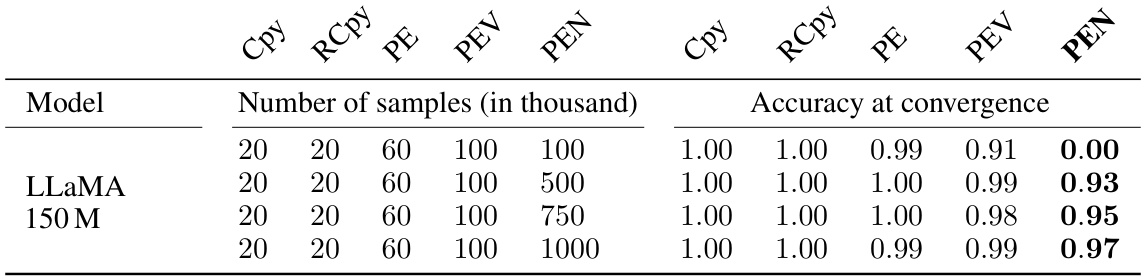

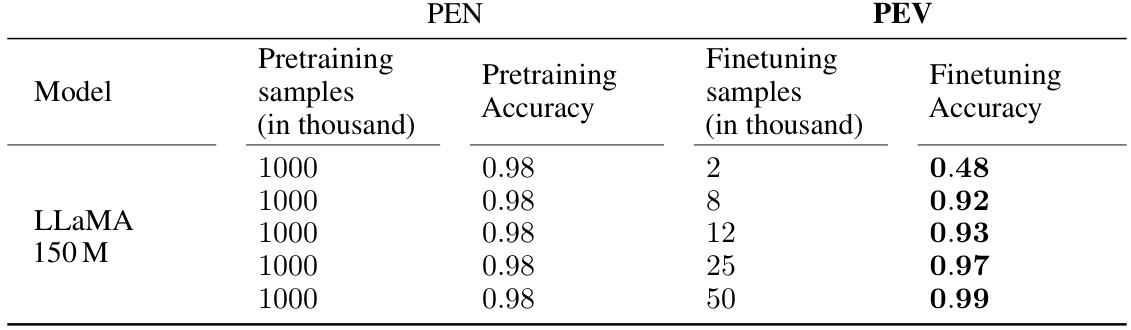

This table presents the results of training a 150M parameter LLaMA model on the PEN task and its subtasks (Cpy, RCpy, PE, PEV). It shows the accuracy achieved at convergence for each task given different numbers of training samples. The key observation is that while the model achieves near-perfect accuracy on the individual subtasks, it requires significantly more data to learn the compositional PEN task. This finding supports the hypothesis H4 which states that LLMs are highly sample inefficient when learning compositional tasks.

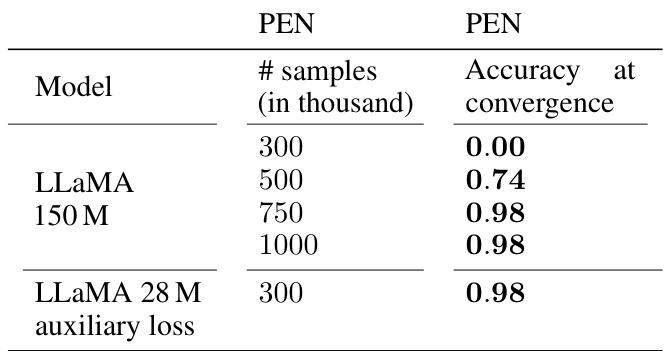

This table presents the results of training LLAMA models only on the PEN task, without training on the sub-tasks. It compares the accuracy at convergence for different numbers of training samples to the results from Table C.2, where LLAMA was trained on both the PEN task and its constituent subtasks. The comparison highlights whether pre-training on sub-tasks provides any benefit for learning the main task, addressing the question of compositional learning efficiency.

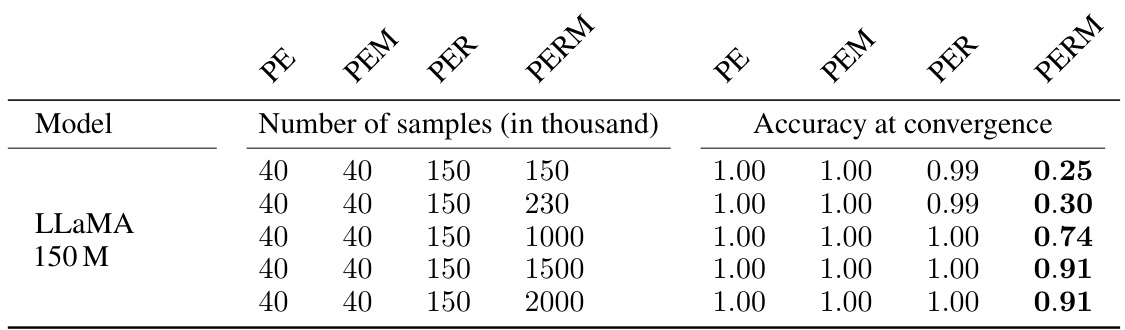

This table presents the results of training LLAMA models on the PERM task and its subtasks (PE, PEM, PER). It shows the accuracy achieved at convergence for each task at different sample sizes. The results demonstrate that while the model learns individual sub-tasks effectively, it struggles to learn the composition of these subtasks efficiently. A significantly larger dataset is required to successfully learn the full PERM task compared to the sum of samples needed to train its individual sub-tasks.

This table shows the performance of LLAMA models trained only on the PERM task. It compares the accuracy achieved at convergence for different numbers of training samples (500, 1000, 1500, and 2000 thousand). The results are compared to the results in Table C.4, where the model was trained on both the PERM task and its sub-tasks. The comparison highlights that there’s no significant improvement in performance by including sub-tasks during training, further demonstrating the inefficiency of compositional learning in LLAMAs.

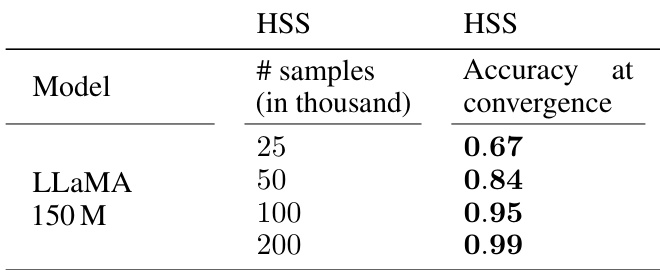

This table presents the results of training 150M parameter LLaMA models on two tasks: Highest Subsequence Sum (HSS) and Highest Subsequence Execution (SSE). The table shows the accuracy achieved at convergence for different numbers of training samples. It demonstrates that the model needs significantly more samples to learn the compositional task (HSS) than to learn the subtask (SSE), supporting hypothesis H4, which states that a Transformer language model requires more samples for compositional tasks than the sum of samples needed for each subtask. The results are consistent across different sample sizes.

This table presents the accuracy of the 150M parameter LLaMA model on the Highest Subsequence Sum (HSS) task, trained only on this task and without the use of subtasks, at different training sample sizes (in thousands). The results demonstrate that the model’s accuracy improves with increasing training data. This table is part of a larger analysis examining the sample efficiency of LLaMA on compositional algorithmic tasks.

This table presents the results of training LLaMA models on four different tasks: Digit Multiplication (DMUL), addition (ADD), multiplication (MUL), and a composite task that combines the three. The table shows the accuracy achieved by the models at convergence for each task and various training sample sizes. The results support hypothesis H4, stating that the models need more training samples to learn the composite task than the sum of samples needed for each subtask.

This table shows the accuracy of the 150M parameter LLaMA model on the multiplication task (MUL) at convergence for various training dataset sizes (200k, 400k, 800k, and 1600k samples). It highlights the model’s performance on this single task without the benefit of training on related sub-tasks, showing how sample efficiency varies with dataset size.

This table shows the results of pre-training LLAMA models on the PEN task and then fine-tuning them on the PEV task. It demonstrates that while pre-training improves sample efficiency for fine-tuning, a substantial number of samples (at least 50,000) are still needed to achieve high accuracy, suggesting that hypothesis H1 (constant number of samples for compositional learning) is unlikely to hold.

This table shows the results of pre-training a LLAMA model on the PERM task and then fine-tuning it on the PE task. It compares the accuracy achieved at different numbers of fine-tuning samples, highlighting the impact of pre-training on sample efficiency for decompositional learning.

This table summarizes the performance of GPT-4 and Gemini-Pro on the PEN and PERM tasks using various prompting techniques. It shows that even with strong hints and advanced prompting methods, both models struggle to achieve high accuracy, particularly on the PEN task. The results highlight the challenges in compositional learning for LLMs even with in-context learning.

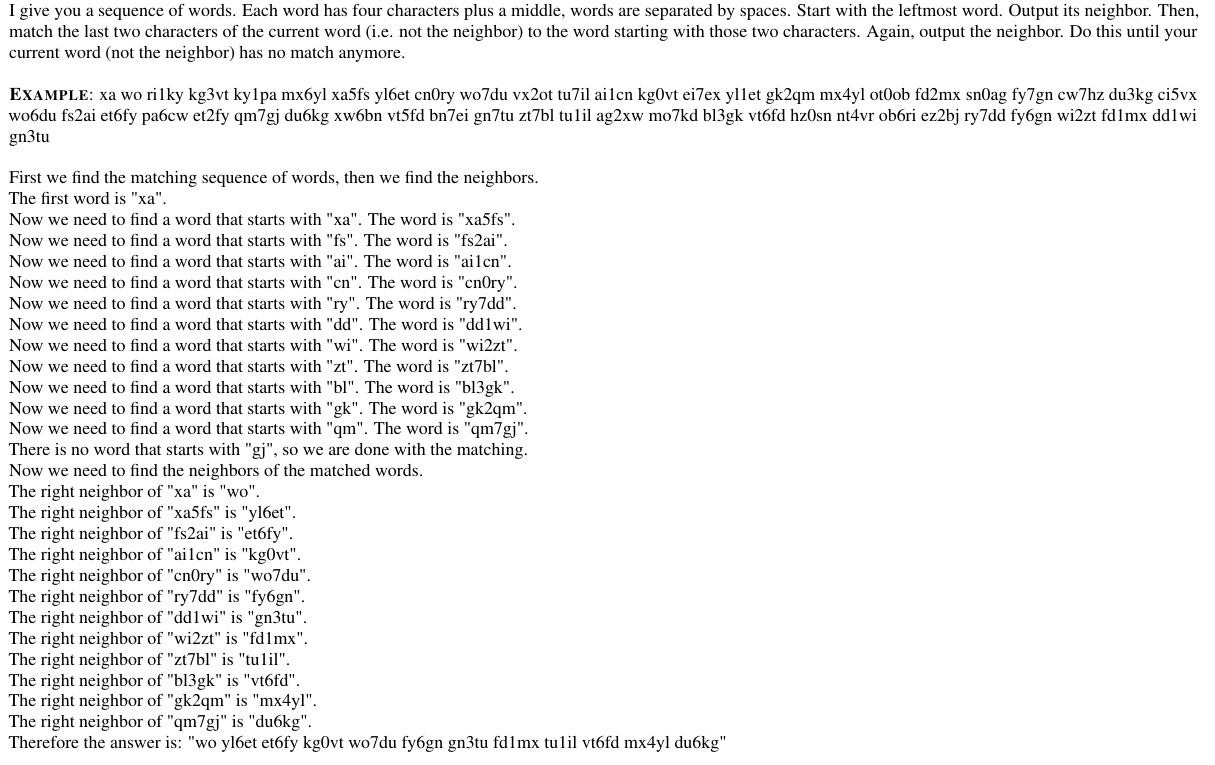

This table presents the results of using various prompting methods (few-shot, chain-of-thought, analogical chain-of-thought, code interpreter) with GPT-4 and Gemini-Pro on two algorithmic tasks, PEN and PERM. The table shows the task accuracy, match accuracy, and termination accuracy achieved by each model under different prompting techniques. Notably, even with detailed prompts, both models struggled significantly on PEN, achieving 0% task accuracy, while performance on PERM was somewhat better but still limited, highlighting challenges in compositional learning and multi-round reasoning.

This table presents the results of experiments using GPT-4 and Gemini-Pro on two tasks, PEN and PERM, with various prompting methods. The results are broken down by prompting technique (few-shot, CoT, analogical CoT, code interpreter) and indicate the task accuracy, match accuracy, and termination accuracy achieved. The table highlights the difficulties both models face in achieving high accuracy, particularly on the PEN task, even with sophisticated prompting strategies. The results suggest that simple few-shot prompting or even detailed descriptions are insufficient, and more complex, multi-step reasoning methods are needed for successful performance.

Full paper#