↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional digital twin creation in healthcare often relies on invasive procedures to obtain comprehensive patient data, limiting its accessibility and practicality. This poses significant challenges for personalized medicine, especially in creating models of dynamic physiological processes. The lack of sufficient labeled data is also a major hurdle for employing supervised machine learning techniques.

The researchers address these issues by introducing Med-Real2Sim, a novel method employing physics-informed self-supervised learning. This technique uses a two-step approach. First, a neural network is pre-trained on synthetic data to learn the dynamics of a physics-based model of the physiological process. Then, this model is fine-tuned using real non-invasive patient data to learn a mapping between the data and the model’s parameters. This method effectively combines data-driven and mechanistic modeling techniques. This method successfully builds digital twins of cardiac hemodynamics from echocardiography data alone, enabling the accurate simulation of pressure-volume loops and leading to improved disease detection and enabling in-silico trials.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents Med-Real2Sim, a novel method for creating personalized, physics-based models of the human body using only non-invasive data. This addresses a critical challenge in healthcare, enabling the creation of digital twins without the need for risky invasive procedures. The framework is highly scalable, applicable to various physiological processes and opens up new avenues for in-silico clinical trials and disease detection. This advances the field of personalized medicine and paves the way for more precise, efficient, and patient-specific healthcare.

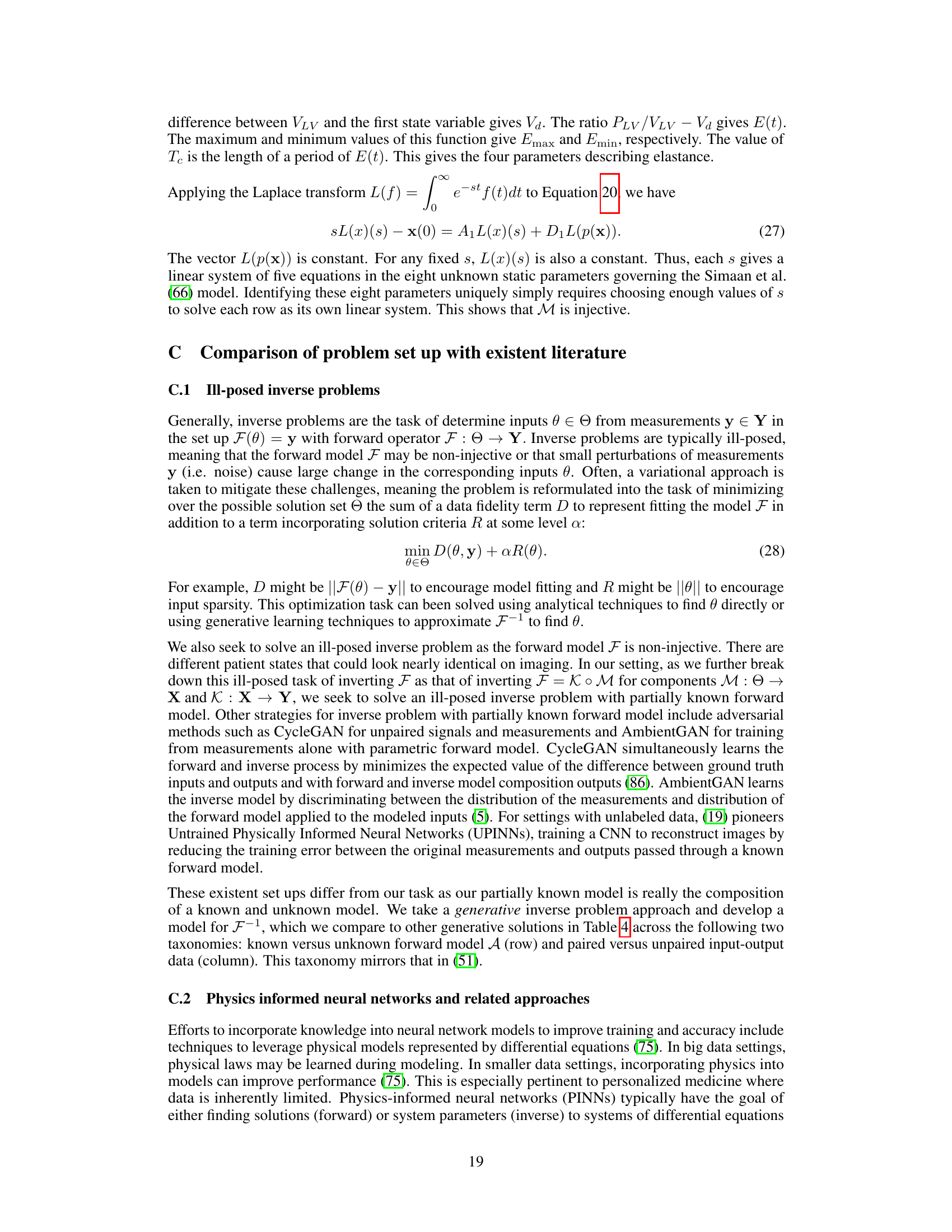

Visual Insights#

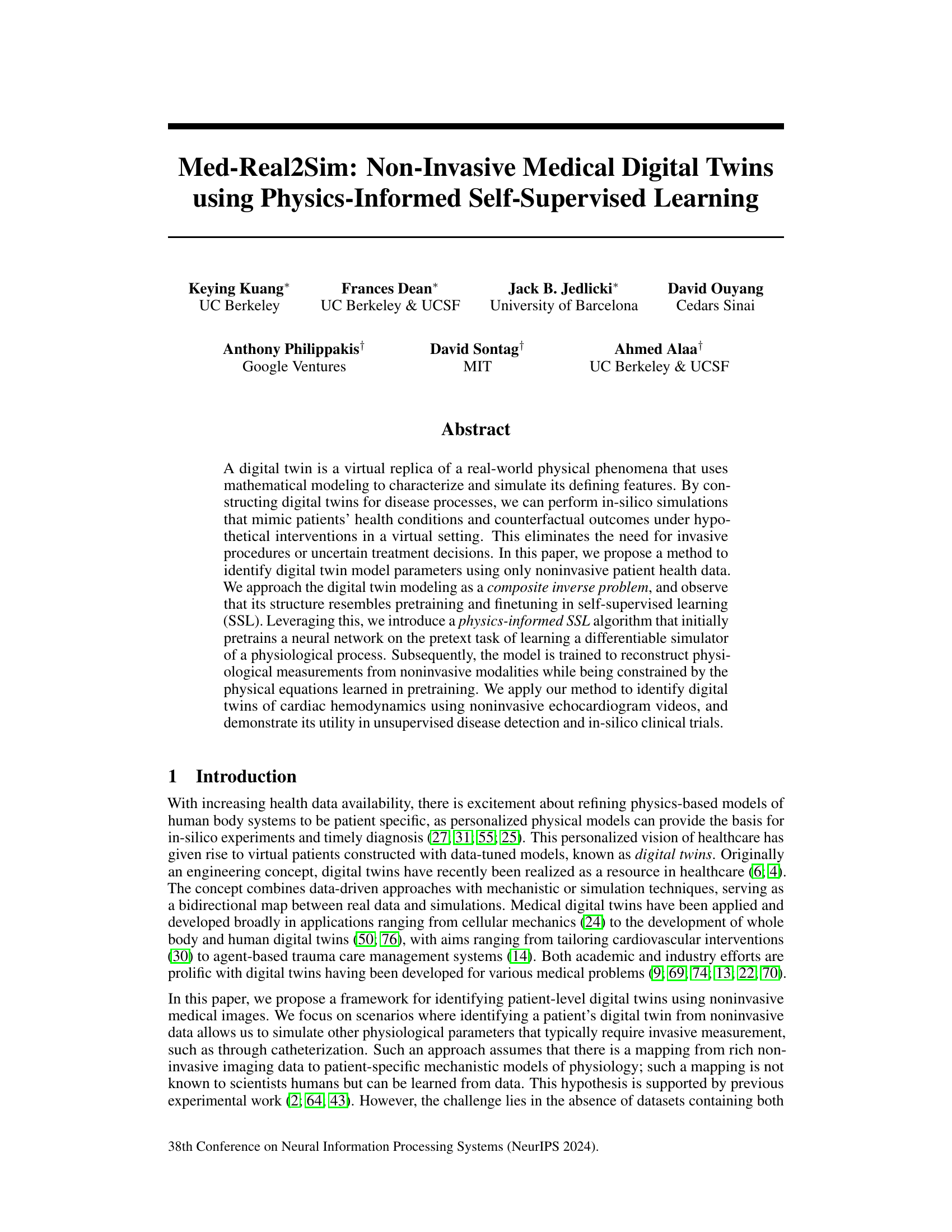

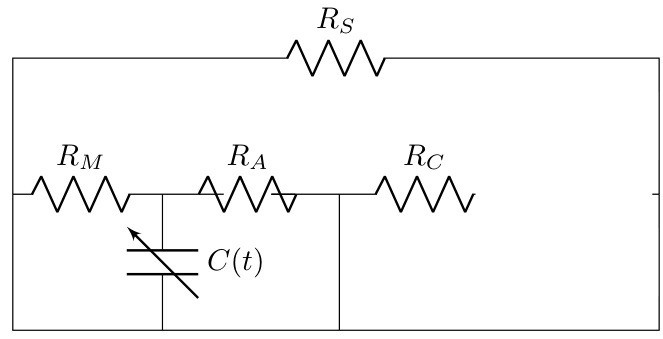

This figure illustrates the concept of digital twins for cardiac hemodynamics. The left panel shows a diagram of the cardiovascular system, highlighting key components like the left ventricle, aorta, and aortic valve. The right panel presents two simplified models representing the cardiovascular system: a hydraulic model (using fluid dynamics) and an electrical analog (Windkessel model). These models are used to create digital twins that mirror real-world physiological processes, enabling non-invasive simulations and analysis.

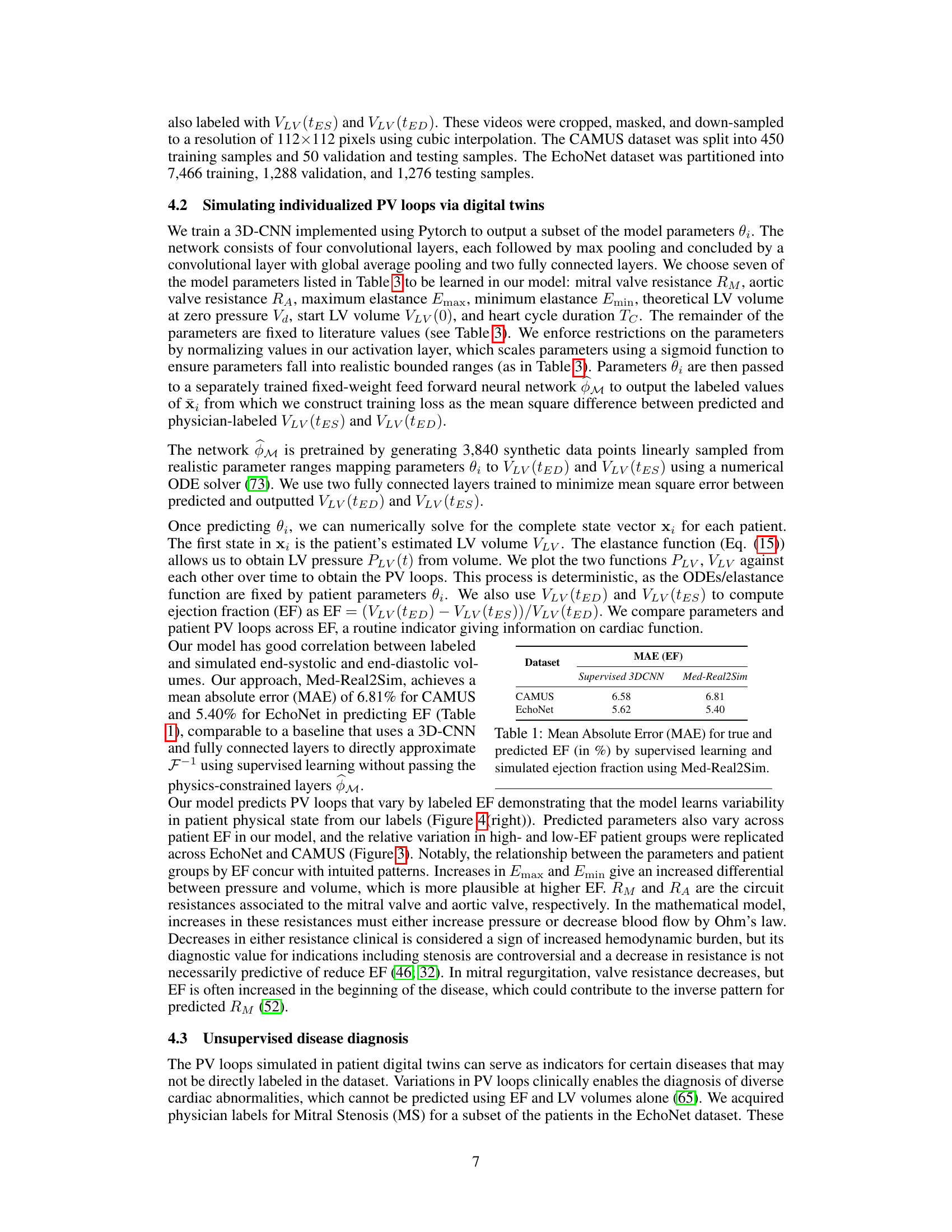

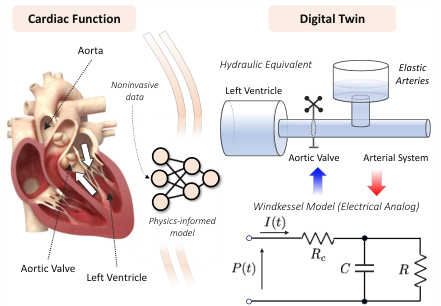

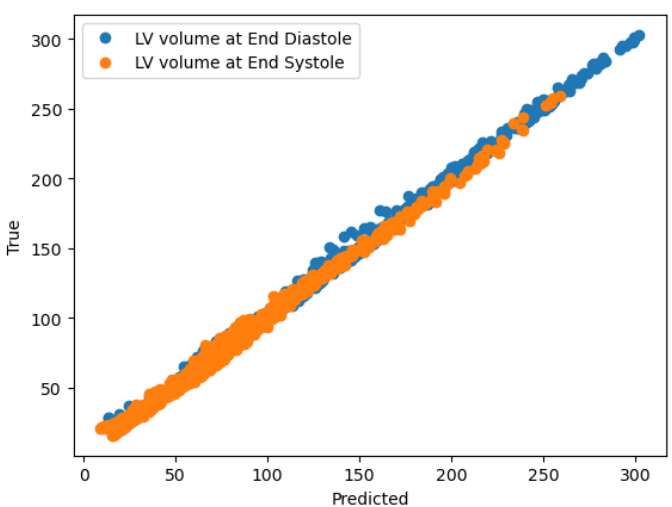

This table compares the mean absolute error (MAE) in predicting the ejection fraction (EF) between a supervised 3D convolutional neural network (3DCNN) and the proposed Med-Real2Sim method. The MAE is a measure of the average absolute difference between the predicted and true EF values. Lower MAE values indicate better performance. The results are presented for two datasets: CAMUS and EchoNet.

In-depth insights#

Physics-Informed SSL#

The proposed “Physics-Informed Self-Supervised Learning (SSL)” approach cleverly combines the strengths of physics-based modeling and self-supervised learning. The core idea is to leverage synthetic data generated from a known physics-based model to pre-train a neural network. This pre-training step acts as a pretext task, teaching the network the underlying physical principles governing the system. Subsequently, the pre-trained network is fine-tuned using real, non-invasive patient data. This two-step process effectively addresses the challenge of limited labeled data in medical applications by first learning the underlying physics and then adapting it to patient-specific information. The physics-informed aspect ensures that the learned model respects the physical constraints of the system, which is crucial for reliability and interpretability. The approach is particularly well-suited for applications where obtaining labeled data is difficult or expensive, such as in medical imaging, and allows for the generation of virtual patient simulators based on non-invasive data, paving the way for personalized medicine and in-silico clinical trials. The success of this methodology hinges on the quality of the physics-based model and the effectiveness of the self-supervised learning strategy in bridging the gap between synthetic and real-world data. The key advantage lies in its ability to learn a virtual simulator from limited real data by leveraging a physics-based model’s prior knowledge.

Cardiac PV Loops#

Cardiac pressure-volume (PV) loops are graphical representations of the relationship between left ventricular pressure and volume during a single cardiac cycle. They provide a comprehensive assessment of cardiac function, going beyond simpler metrics like ejection fraction. The shape of the loop reflects various physiological parameters, including preload, afterload, contractility, and relaxation. Non-invasive methods for acquiring data sufficient to accurately generate PV loops are highly sought after in cardiology, as traditional methods rely on invasive catheterization. This paper explores the use of physics-informed self-supervised learning to create accurate, patient-specific digital twins capable of simulating PV loops from non-invasive echocardiogram data. By integrating mechanistic models of cardiac hemodynamics with data-driven approaches, the research aims to bridge the gap between non-invasive imaging and the detailed functional information provided by PV loops. The success of this approach could significantly impact clinical diagnosis and treatment planning, allowing for personalized, risk-stratified care and reducing the reliance on invasive procedures.

Med-Real2Sim Model#

The Med-Real2Sim model, as described in the research paper, presents a novel approach to building non-invasive medical digital twins using physics-informed self-supervised learning. Its core innovation lies in combining two inverse problems: the identification of patient-specific parameters from non-invasive data (like echocardiograms) and the simulation of physiological states from those parameters using a known physics-based model. Instead of relying on scarce and difficult-to-obtain paired data, Med-Real2Sim cleverly leverages a two-step process. First, it pre-trains a neural network on synthetic data generated from the physics-based model, learning to approximate the forward model. Second, it fine-tunes this pre-trained network on real, non-invasive data to learn the mapping between measurements and the latent model parameters. This approach resembles self-supervised learning, enabling effective training even in the absence of fully labeled datasets. The model’s efficacy is showcased through its application to cardiac hemodynamics, accurately predicting pressure-volume loops from echocardiogram data. Importantly, Med-Real2Sim has the potential to improve disease detection and facilitate in-silico clinical trials, enabling personalized medicine without invasive procedures.

In-silico Trials#

The concept of ‘in-silico trials’ in the context of this research paper is particularly insightful. It leverages the creation of patient-specific digital twins to simulate the effects of hypothetical interventions, such as the introduction of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD). This eliminates the need for risky and expensive physical trials, offering a powerful tool for personalized medicine. The computational nature of these trials allows for rapid exploration of various treatment parameters and strategies, enabling the optimization of therapy for each individual patient. This approach is non-invasive; it avoids invasive procedures to obtain necessary information, further enhancing its potential clinical utility. The paper demonstrates how the digital twin model can accurately predict changes in ejection fraction, a crucial cardiac performance indicator, following simulated interventions. The ability to perform in-silico trials opens up new possibilities for clinical research by allowing researchers to study the effects of multiple interventions, dosage levels, and temporal dynamics in a computationally efficient and ethical manner. Further development of such methodologies can accelerate the pace of medical breakthroughs and significantly improve the quality of care.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending Med-Real2Sim to other physiological systems, such as the respiratory or neurological systems, and incorporating more diverse and comprehensive datasets that include a wider range of patient demographics and disease severities. Investigating the robustness of the model to different imaging modalities and exploring techniques for handling noisy or incomplete data are also crucial. Additionally, it will be important to formalize and rigorously evaluate the clinical utility of Med-Real2Sim, potentially through larger-scale clinical trials involving a more diverse patient population. This could involve developing user-friendly interfaces and workflows to seamlessly integrate Med-Real2Sim into clinical practice. Finally, research into developing methods for simulating and optimizing the effects of various interventions in silico will unlock the model’s full potential for personalized medicine and clinical decision support.

More visual insights#

More on figures

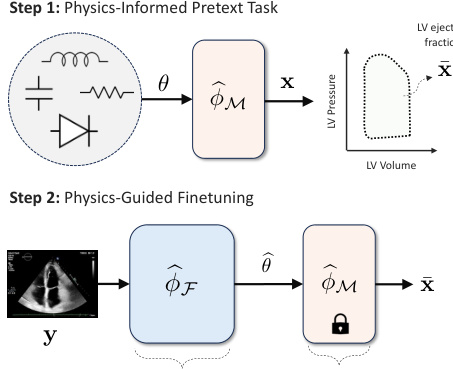

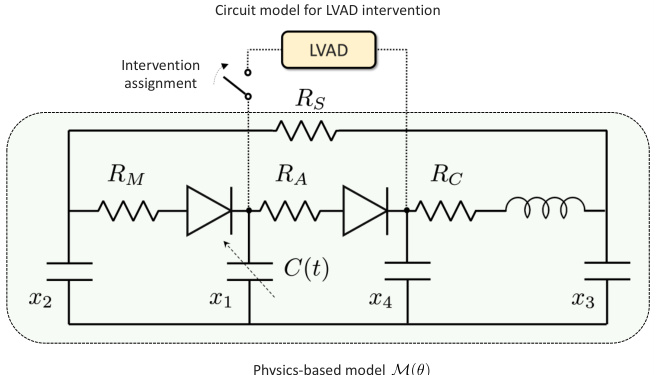

This figure illustrates the Med-Real2Sim framework. Panel (a) shows a flowchart of the two-step physics-informed self-supervised learning process: first, a physics-informed pretext task pre-trains a neural network on synthetic data; then, physics-guided finetuning fine-tunes another model using real data. Panel (b) shows a five-state lumped-parameter electric circuit model of cardiac hemodynamics, representing the digital twin. The model includes parameters representing the left ventricle, left atrium, arteries, and aorta, and an optional left ventricular assist device (LVAD).

This figure illustrates the Med-Real2Sim framework. Panel (a) shows a flowchart of the two-step physics-informed self-supervised learning process: a pretext task using synthetic data to learn the forward dynamics of a physics-based model, followed by finetuning on real data to learn the inverse mapping from non-invasive measurements to model parameters. Panel (b) shows the five-state lumped-parameter electric circuit model of cardiac hemodynamics used in the study, which includes a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) for simulating interventions.

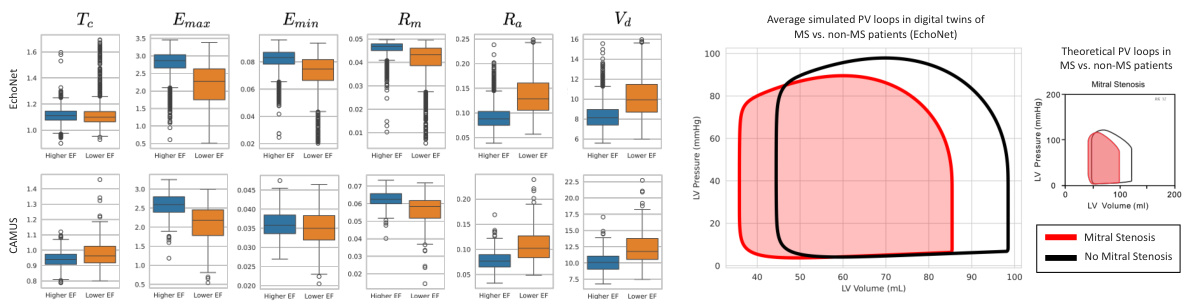

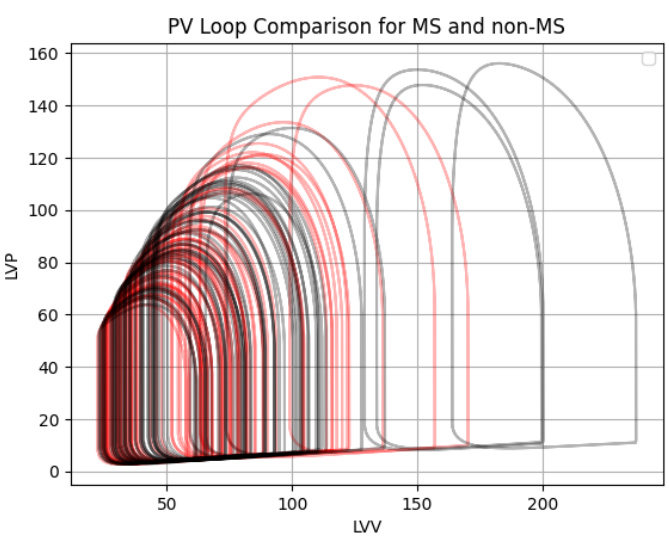

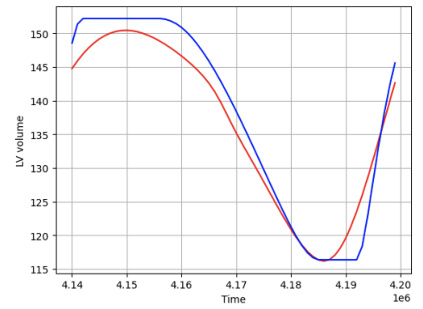

This figure shows the results of applying the Med-Real2Sim method to two datasets, EchoNet and CAMUS. Panel (a) presents box plots illustrating the distribution of learned parameters (mitral valve resistance, aortic valve resistance, maximum elastance, minimum elastance, theoretical LV volume at zero pressure, start LV volume, and heart cycle duration) for high and low ejection fraction (EF) groups within each dataset. Panel (b) compares the average simulated pressure-volume (PV) loops for patients with and without mitral stenosis (MS), highlighting differences in hemodynamics between these groups. The theoretical PV loop for MS patients is shown for comparison.

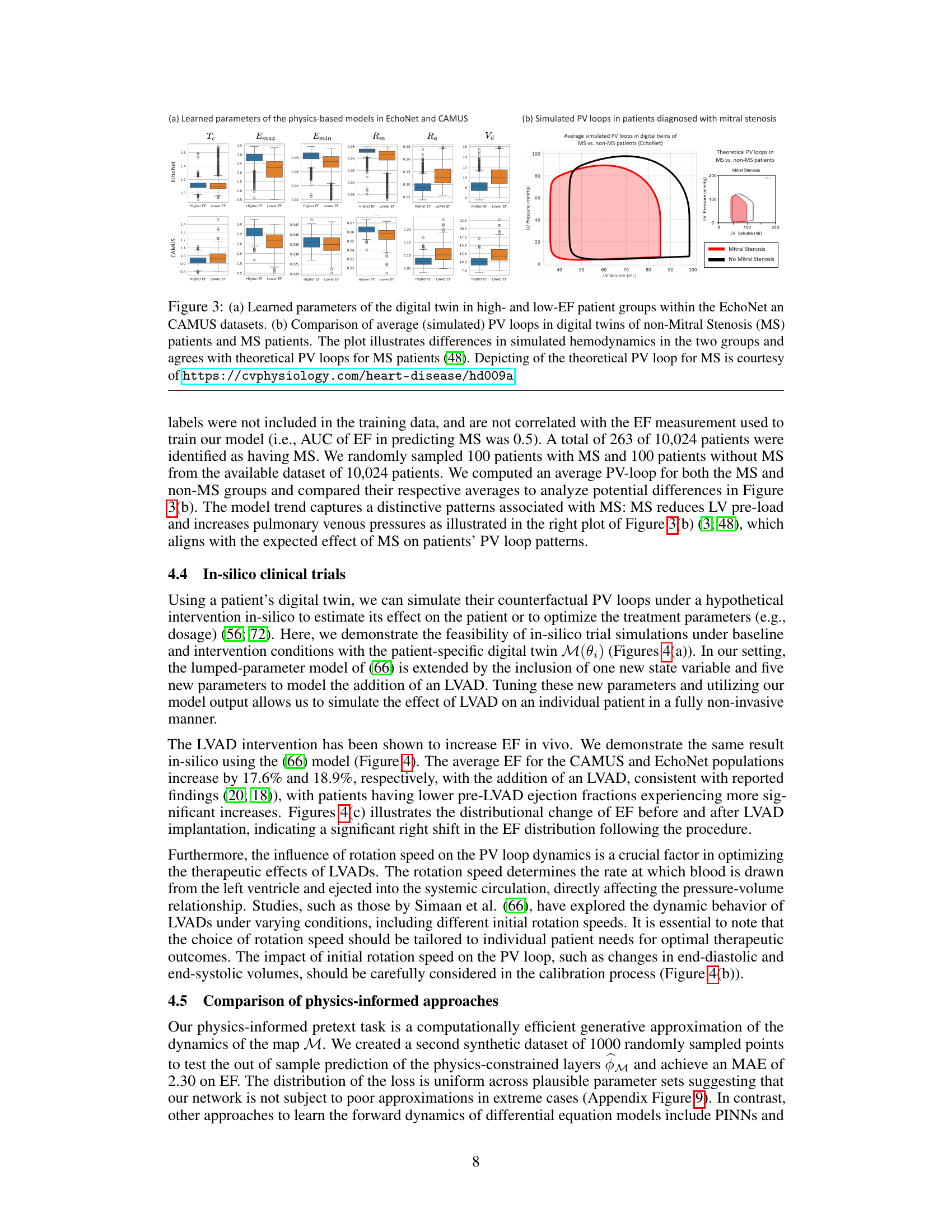

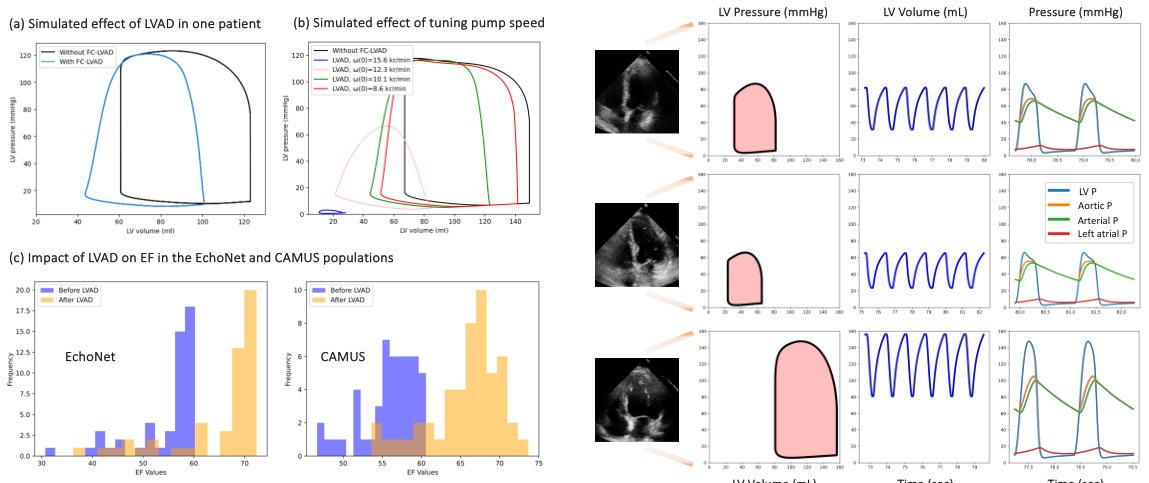

This figure demonstrates the results of in-silico experiments using the developed digital twin model. Panel (a) shows a comparison of pressure-volume (PV) loops for a single patient with and without a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) intervention. Panel (b) illustrates how tuning the pump speed affects the PV loop. Panel (c) presents the distribution of ejection fraction (EF) values before and after LVAD implantation for two datasets, highlighting a significant increase in EF after the intervention. The right side of the figure displays example PV loops for patients with different EF levels.

This figure shows the electric circuit model used in the paper, highlighting the nodes used to derive the system of ODEs that govern the model. Each colored circle represents a node where Kirchhoff’s current law is applied to obtain one of the five ODEs. The figure shows resistors, capacitors, diodes, and inductors, which together model the various components and dynamics of the cardiovascular system. The colored lines connecting the components represent current flow (blood flow in the hydraulic analogy). The fifth equation is obtained by applying Kirchhoff’s law for the total flow in the system.

This figure shows a simplified equivalent circuit of the left ventricle, represented using the Norton equivalent circuit theorem. The theorem states that any linear circuit can be simplified to a single current source in parallel with a single resistor connected to a load of interest. In this case, the load is the capacitor representing the pressure changes in the left ventricle. This simplification is used in the paper’s attempt to reduce the complexity of the model, especially to leverage linear circuit analysis to obtain the pressure changes in the left ventricle more easily.

This figure illustrates the Med-Real2Sim framework. Panel (a) shows a flowchart summarizing the two-step physics-informed self-supervised learning process: (1) pre-training a neural network on synthetic data to learn the forward dynamics of a physics-based model and (2) fine-tuning this model using real data to predict the model parameters from non-invasive measurements. Panel (b) shows a five-state lumped-parameter electrical circuit model of cardiac hemodynamics, which serves as the physics-based model in the proposed approach. The model includes components representing the left ventricle, left atrium, arteries, and aorta, as well as a left ventricular assist device (LVAD).

Figure 3(a) shows the learned parameters of the digital twin model for high and low ejection fraction (EF) patient groups in the EchoNet and CAMUS datasets. Figure 3(b) compares the average simulated pressure-volume (PV) loops of digital twins for patients with and without mitral stenosis (MS), demonstrating the differences in simulated hemodynamics and aligning with theoretical PV loops for MS patients.

This figure shows the learned parameters of the physics-based model for high and low ejection fraction patient groups in two datasets (EchoNet and CAMUS). The second part shows a comparison of the average simulated pressure-volume (PV) loops for patients with and without mitral stenosis (MS), illustrating the differences in simulated hemodynamics between the two groups. The simulated results align with theoretical PV loops for MS patients.

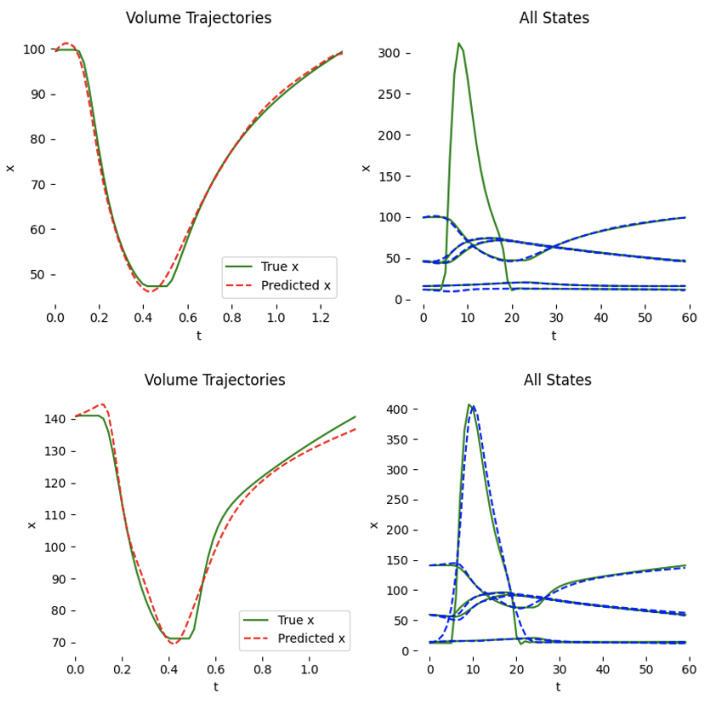

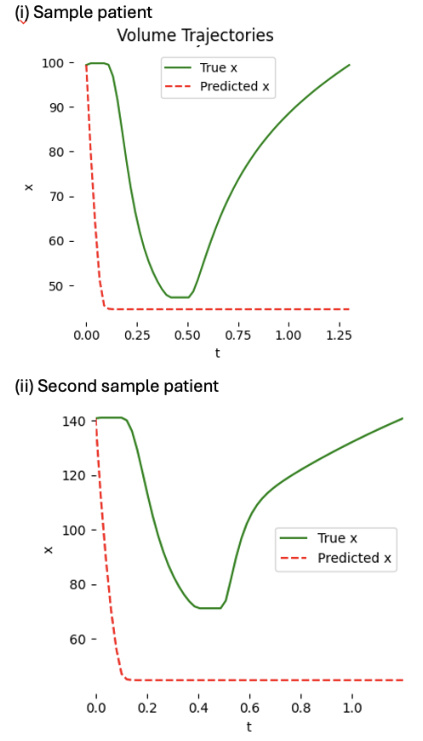

This figure shows two examples of patient-specific PINNs (Physics-Informed Neural Networks) trained on synthetic data. Each PINN aims to predict the left ventricle volume over time. While one PINN successfully learns and accurately predicts the volume curve, the other fails to do so even after extensive training (100,000 epochs), highlighting the variability and challenges in training these models.

This figure shows two examples of patient-specific PINNs (Physics-Informed Neural Networks) that were trained on synthetic data consisting of 60 time points. The top panels display the predicted versus true volume curves for two different patients. The bottom panels provide additional details of the model’s performance, showing the predicted and true values for each of the five states in the cardiac model (left ventricle pressure, left atrium pressure, arterial pressure, aortic pressure, and total flow) over time. Note that one patient’s model performs well, accurately learning the volume curve, while the other does not, demonstrating that the success of the model varies depending on the patient.

This figure illustrates the Med-Real2Sim framework. Panel (a) shows a flowchart summarizing the two-step physics-informed self-supervised learning process: a pretext task using synthetic data to learn the forward dynamics of a physics-based model, followed by finetuning on real data to learn the inverse mapping from non-invasive measurements to model parameters. Panel (b) shows the five-state lumped-parameter electric circuit model of cardiac hemodynamics used in the experiments, which includes a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) that can be activated or deactivated.

This figure demonstrates the results of counterfactual simulations using the LVAD intervention. The left side shows the effect of the LVAD intervention on an individual patient, illustrating changes in PV loops before and after the intervention (a and b). The right side shows the predicted PV loops for patients with normal, high, and low ejection fraction (EF). The comparison highlights how LVAD intervention influences the shape and parameters of the PV loops across various EF groups.

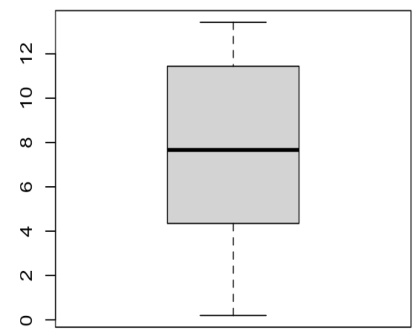

The figure shows box plots of the mean absolute error (MAE) on ejection fraction obtained from 20 patient-specific PINN and Neural ODE models. The box plots illustrate the distribution of MAEs, showing the median, quartiles, and range of errors for both model types. This helps visualize the variability in model performance across different patients.

This figure illustrates the Med-Real2Sim framework. Panel (a) shows a flowchart of the two-step physics-informed self-supervised learning process: First, a neural network imitates the forward dynamics of the physics-based model using synthetic data. Second, this model is used to finetune another model to predict physical parameters from non-invasive measurements. Panel (b) shows a five-state lumped-parameter electric circuit model of cardiac hemodynamics, which includes an optional left-ventricular assist device (LVAD).

More on tables

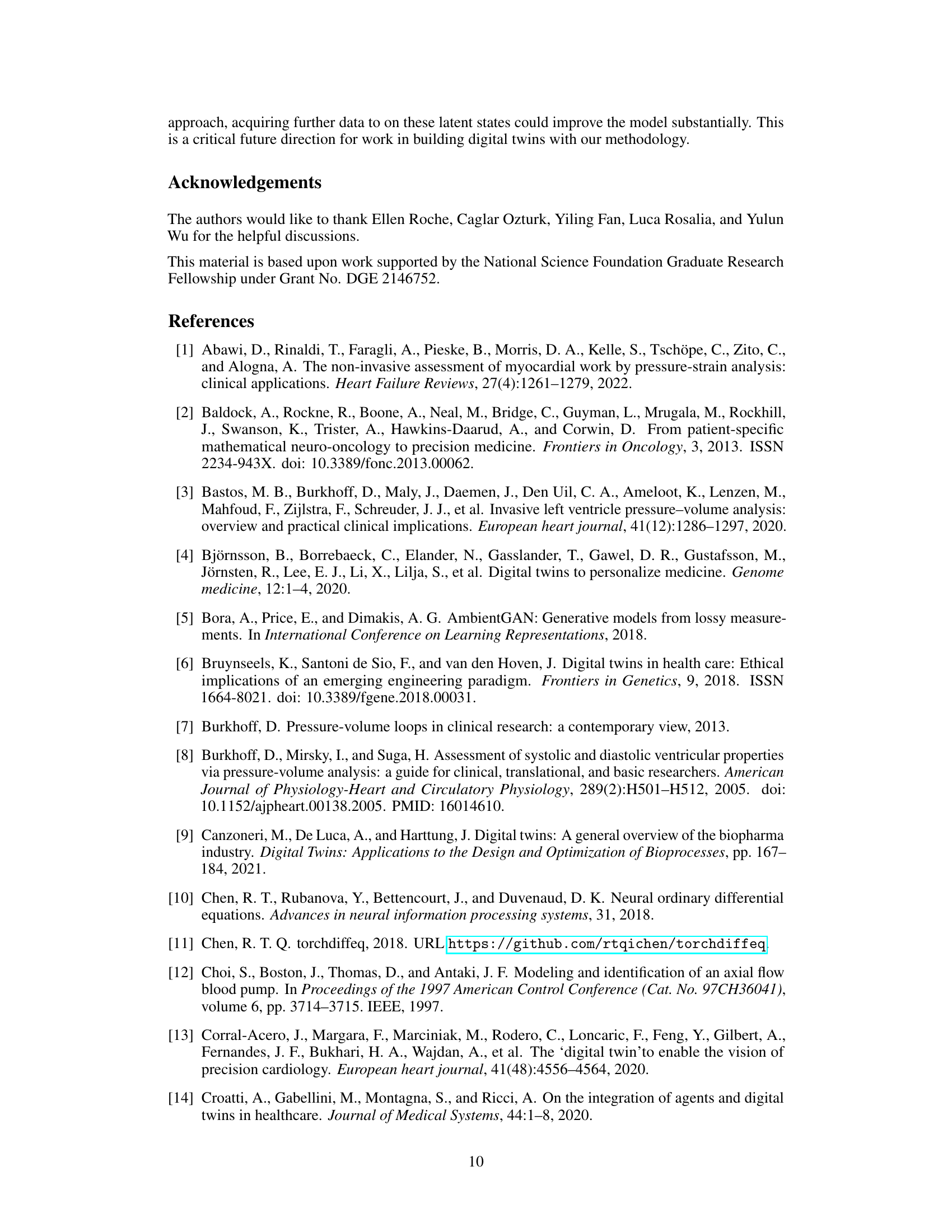

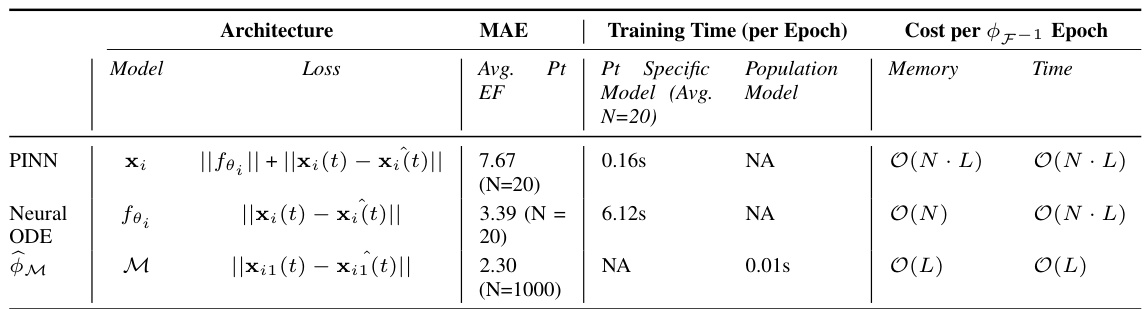

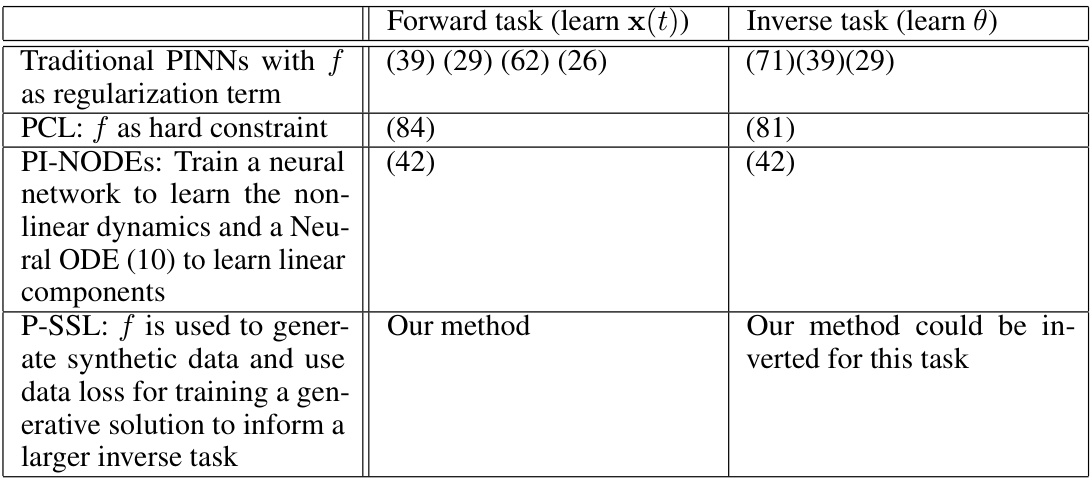

This table compares the performance of three different methods for learning the dynamics of a cardiac hemodynamics model: Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (Neural ODEs), and the proposed Physics-Informed Self-Supervised Learning (P-SSL) method. The comparison is based on the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) in predicting ejection fraction (EF), the training time per epoch, and the computational cost per epoch of inferring the inverse map F⁻¹. The table also shows the memory usage and time complexity of each method. The results indicate that the P-SSL method achieves comparable accuracy to the PINN and Neural ODE methods while being significantly more computationally efficient. Note that N represents the number of patient parameter sets and L represents the number of layers in the network or the number of function evaluations for the Neural ODE.

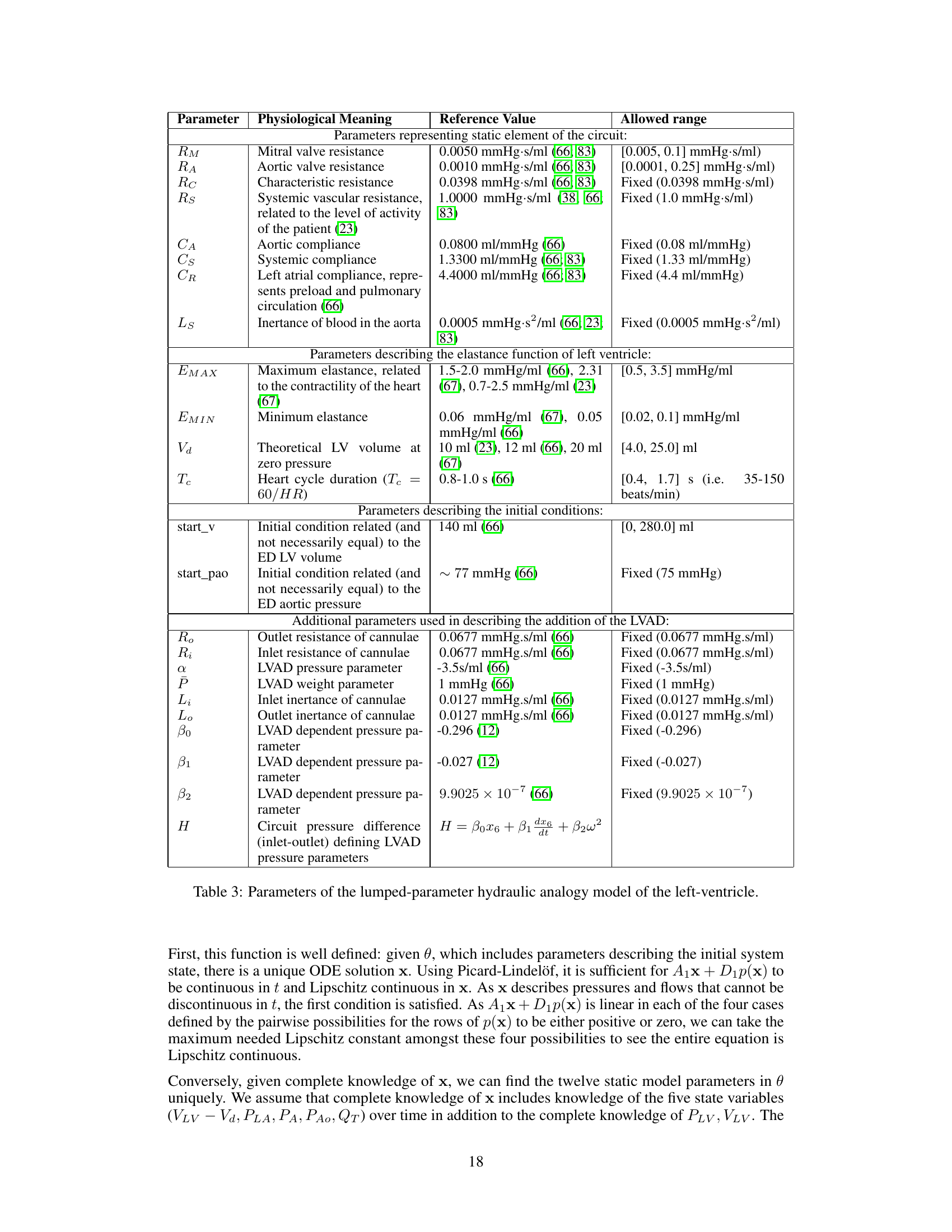

This table lists the parameters of the lumped-parameter hydraulic analogy model used in the paper. It breaks down parameters into categories: static elements of the circuit (resistances, capacitances, inertance), elastance function parameters (maximum and minimum elastance), and initial conditions. Additionally, it details parameters added to model a left-ventricular assist device (LVAD). Each parameter includes its physiological meaning, a reference value from prior work, and the allowed range used in the simulations.

This table compares different approaches to solving ill-posed inverse problems, focusing on the availability of data (paired, unpaired, or only one type of data) and the knowledge of the forward model (known or unknown). It highlights various techniques used, including traditional PINNs, reconstruction methods, and generative models such as CycleGAN and AmbientGAN. The table also shows how the authors’ method addresses this inverse problem by leveraging a partially known model and using a physics-informed self-supervised learning approach.

This table compares three different physics-informed machine learning methods for learning the parameters of a physics-based model of cardiac hemodynamics from non-invasive measurements. The methods are compared in terms of their mean absolute error (MAE) in predicting ejection fraction, the computational cost (memory and time per epoch), and whether they require patient-specific training. The results show that the proposed physics-informed self-supervised learning (P-SSL) method achieves comparable accuracy to more computationally expensive methods, while requiring significantly less training time and not needing to be trained on patient-specific data.

Full paper#