↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Prior research using brain imaging during naturalistic language processing showed bilateral activation patterns, contradicting the well-established left-hemisphere dominance for language. This study investigates whether using more complex language models as fMRI predictors could reveal the known left lateralization. The study found that this was indeed the case, adding to our understanding of how brain regions process language.

The study utilized 28 large language models of varying complexity to analyze fMRI data from participants listening to continuous speech. They found that the accuracy of fMRI prediction improved with model complexity, and more importantly, this improvement was more pronounced in the left hemisphere than in the right, demonstrating left-hemispheric dominance. This finding bridges the gap between previous research and suggests more complex models are essential for better understanding brain activity during language processing.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it resolves the conflict between classic aphasia findings showing left-hemisphere language dominance and recent fMRI studies exhibiting symmetric brain activation during naturalistic language processing. By demonstrating a scaling law linking the complexity of language models to increased left-lateralization in fMRI predictions, it provides insights into brain-language relationships and encourages further research on the interplay of model complexity and hemispheric asymmetry.

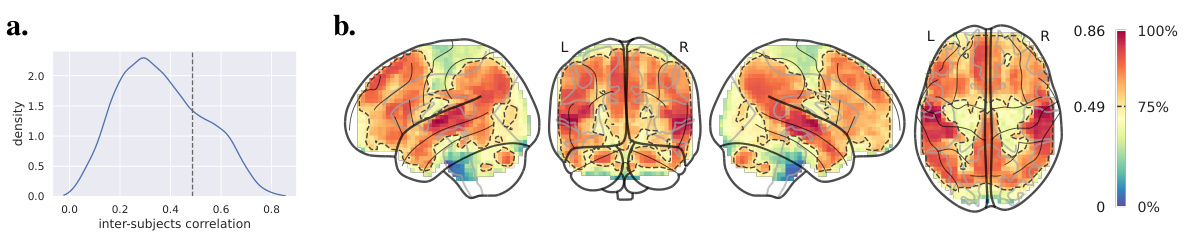

Visual Insights#

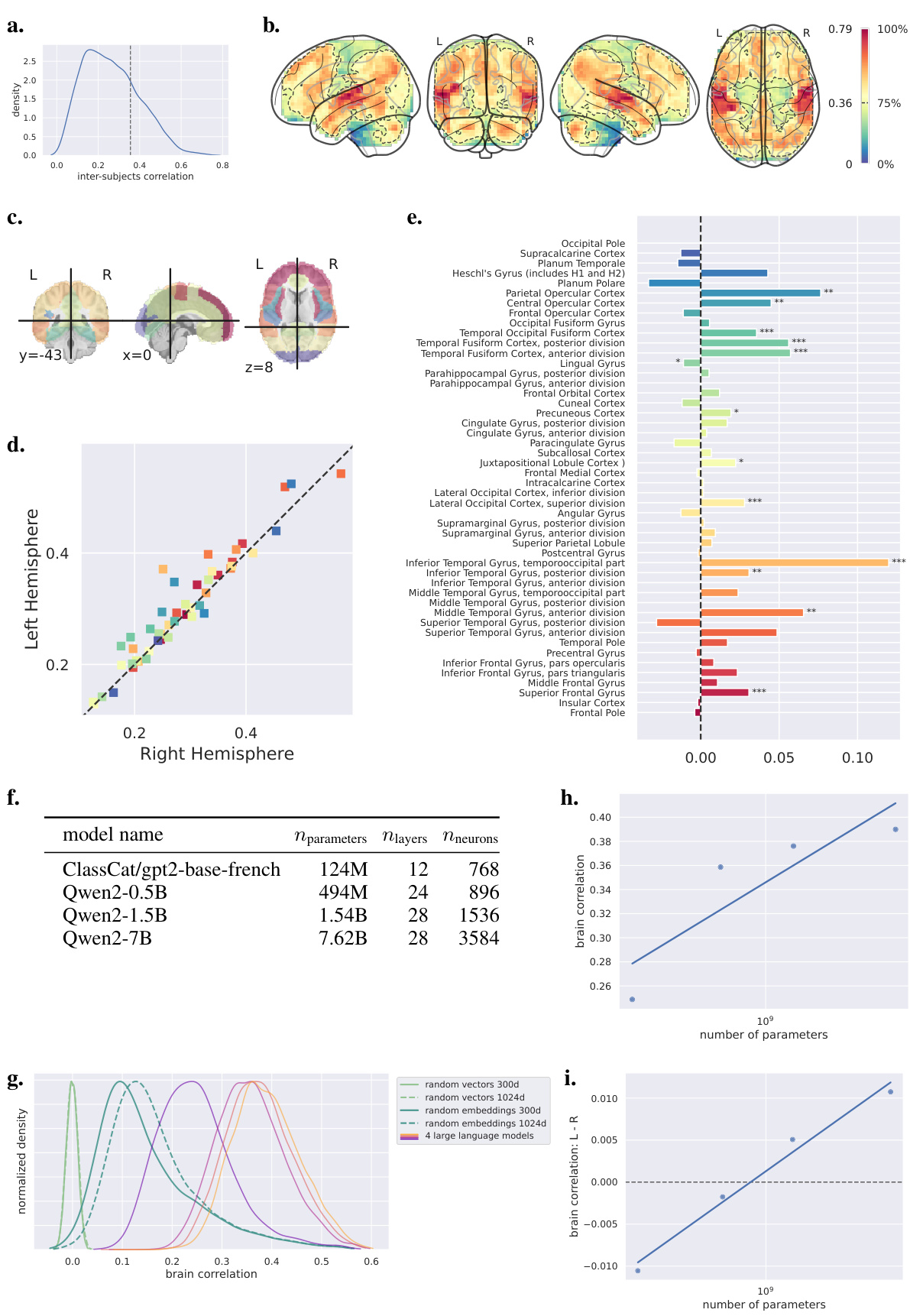

Figure 1 shows the results of analyzing inter-subject correlations in fMRI data. Panel (a) displays a distribution showing the correlation between the fMRI time courses of two subject subgroups. The vertical dotted line indicates the threshold used to identify the top 25% most correlated voxels. Panel (b) presents a glass brain visualization, highlighting these top 25% voxels with warmer colors. These voxels represent brain regions with high inter-subject reliability in fMRI responses, indicating consistent activation patterns across individuals. This suggests these regions are robust and significant for further analysis in the study.

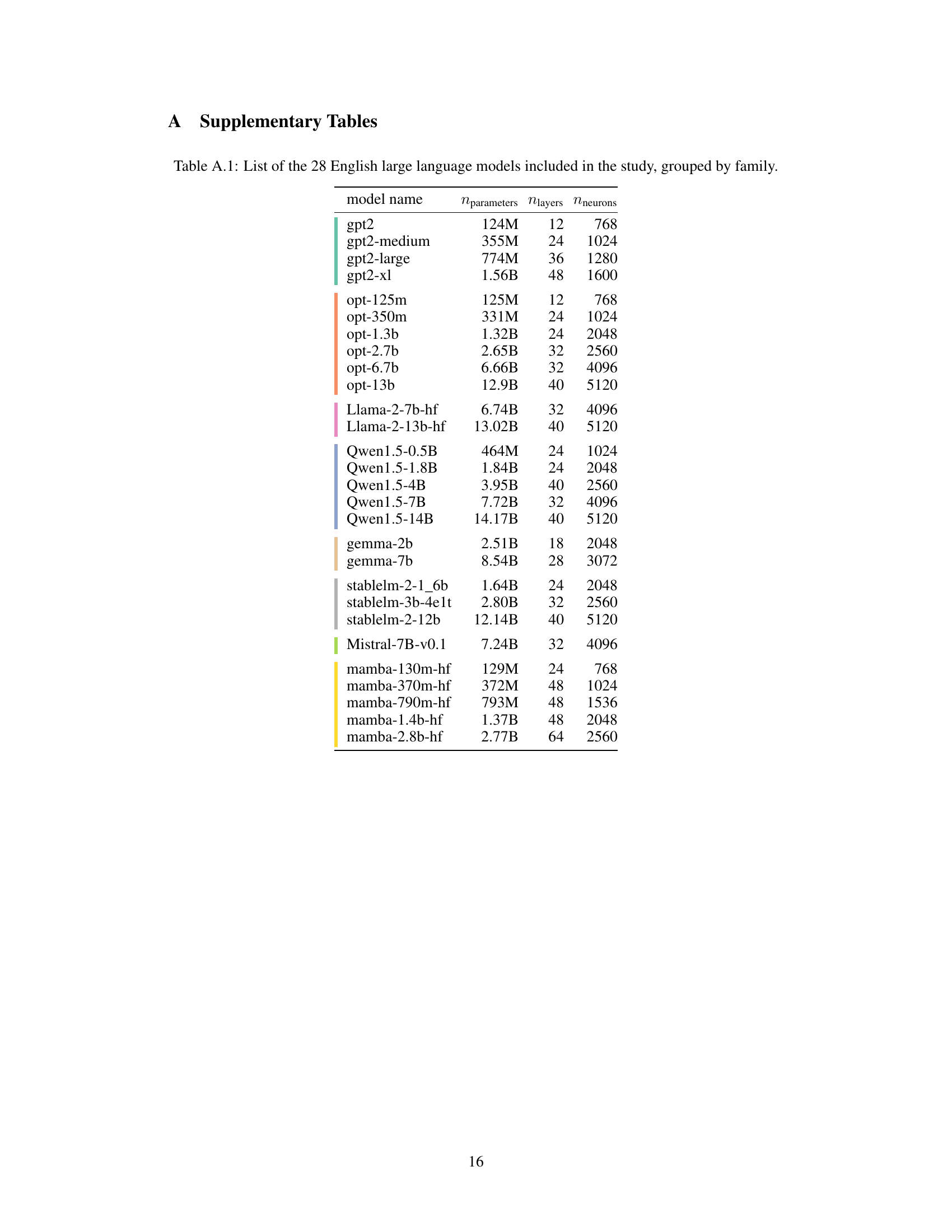

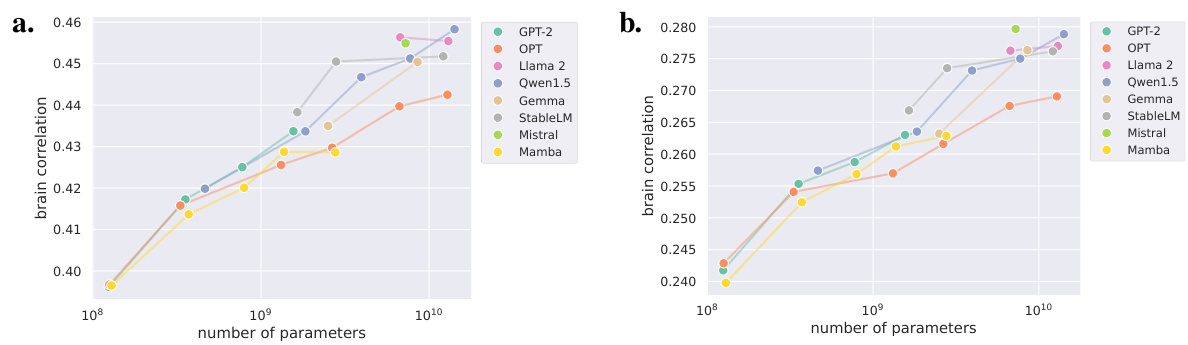

This table lists the 28 English large language models used in the study. For each model, it provides the number of parameters (Nparameters), the number of layers (Nlayers), and the number of neurons in each layer (Nneurons). The models are grouped by their family (GPT-2, OPT, Llama 2, Qwen, gemma, StableLM, Mistral, and Mamba).

In-depth insights#

Left-Hemisphere Bias#

The concept of “Left-Hemisphere Bias” in language processing is a cornerstone of neurolinguistics, yet its manifestation in fMRI studies using large language models (LLMs) has been surprisingly symmetric. This paper challenges the traditional view by demonstrating that increasing the complexity of LLMs recovers the expected left-hemisphere dominance. This finding is crucial as it reconciles the apparent discrepancy between classic aphasia studies showing left-hemispheric language dominance and recent fMRI studies employing LLMs, which exhibited bilateral activation. The authors propose that the left-hemisphere advantage becomes more pronounced as model complexity increases, suggesting that more sophisticated LLMs better capture the nuances of language processing that are preferentially localized in the left hemisphere. This research highlights the importance of model complexity in fMRI-based language studies and opens up new avenues for exploring the neural mechanisms underlying language processing.

LLM fMRI Prediction#

The application of large language models (LLMs) to fMRI prediction presents a fascinating intersection of artificial intelligence and neuroscience. LLMs offer the potential to decode complex brain activity associated with language processing, moving beyond simpler word embedding approaches. By correlating LLM activations with fMRI time series, researchers can identify brain regions strongly associated with specific linguistic computations. However, a significant challenge has been reconciling the often-symmetric brain activation patterns observed with the well-established left-hemispheric dominance in language processing. This discrepancy highlights the need for sophisticated analysis techniques and careful consideration of model complexity. Studies using LLMs of varying sizes show a scaling effect, with larger, more complex models increasingly revealing left-lateralization, potentially bridging the gap between computational models and the neurobiological reality of language. This opens exciting avenues for future research, including investigating how model architecture and training affect the predictive power and brain localization patterns. Further investigation is needed to resolve the precise neurological mechanisms behind the observed relationships between LLMs, fMRI signals, and the brain’s left-hemisphere dominance in language. This may involve more granular analyses across different brain regions, along with the integration of other relevant linguistic features.

Scaling Laws in fMRI#

The concept of “Scaling Laws in fMRI” investigates how the size and complexity of language models correlate with their ability to predict brain activity measured via fMRI. Larger, more sophisticated models generally show improved performance in predicting fMRI signals. This observation suggests a relationship between the computational capacity of the models and the neural processes underlying language comprehension. The scaling laws themselves reveal a quantitative relationship, often described as linear, between a model’s parameters (e.g., number of weights) and its prediction accuracy, suggesting a potential fundamental principle underlying brain-language interactions. However, the exact nature of this relationship and its implications are still under investigation. Further research is needed to explore the mechanistic underpinnings of these scaling laws, possibly revealing novel insights into brain function and language processing. This work also highlights potential limitations in the current understanding of brain organization and the need for more sophisticated modeling techniques.

Model Size & Asymmetry#

The research explores the relationship between model size and the emergence of left-right asymmetry in brain activation patterns during language processing. Larger language models demonstrated a stronger correlation with brain activity in the left hemisphere compared to the right, suggesting a left-hemisphere dominance for language processing, which is consistent with classic observations from aphasia studies. This finding challenges previous research using simpler models that revealed symmetrical bilateral activation patterns. The study suggests that the increased complexity and performance of larger models enhance their capacity to capture the left hemisphere’s specialized role in language. The scaling law observed in the relationship between model size and predictive accuracy is also intriguing, and is particularly strong in regions like the left angular gyrus. The study’s findings reconcile computational language model analyses with the well-established neurological understanding of language lateralization, offering valuable insights into the neural mechanisms underlying language comprehension.

Cross-Linguistic Findings#

A cross-linguistic investigation into the neural correlates of language processing would ideally involve analyzing fMRI data from multiple language groups. This would allow researchers to identify both universal aspects of language processing, reflected in consistent brain activation patterns across languages, and language-specific aspects, revealed by differences in activation patterns. A key question is whether the left-hemisphere dominance for language, a well-established finding in monolingual studies, generalizes across different linguistic structures. Similarities in brain activation patterns across languages would support the universality of certain neural mechanisms for language comprehension. However, differences could highlight how specific language characteristics shape the neural processes involved, emphasizing the interplay between universal cognitive capacities and language-specific learning and experience. Such an approach could provide critical insights into the neural basis of language, potentially uncovering both fundamental and variable aspects of the human capacity for language. The analysis needs to account for various factors, including the potential impact of language typology (e.g., differences in word order), writing systems, and cultural contexts. It is also crucial to consider statistical power and methodology in such a study to obtain reliable and meaningful results. Careful comparison across languages, using sophisticated analytic techniques, could contribute significantly to our overall understanding of the neurobiology of language.

More visual insights#

More on figures

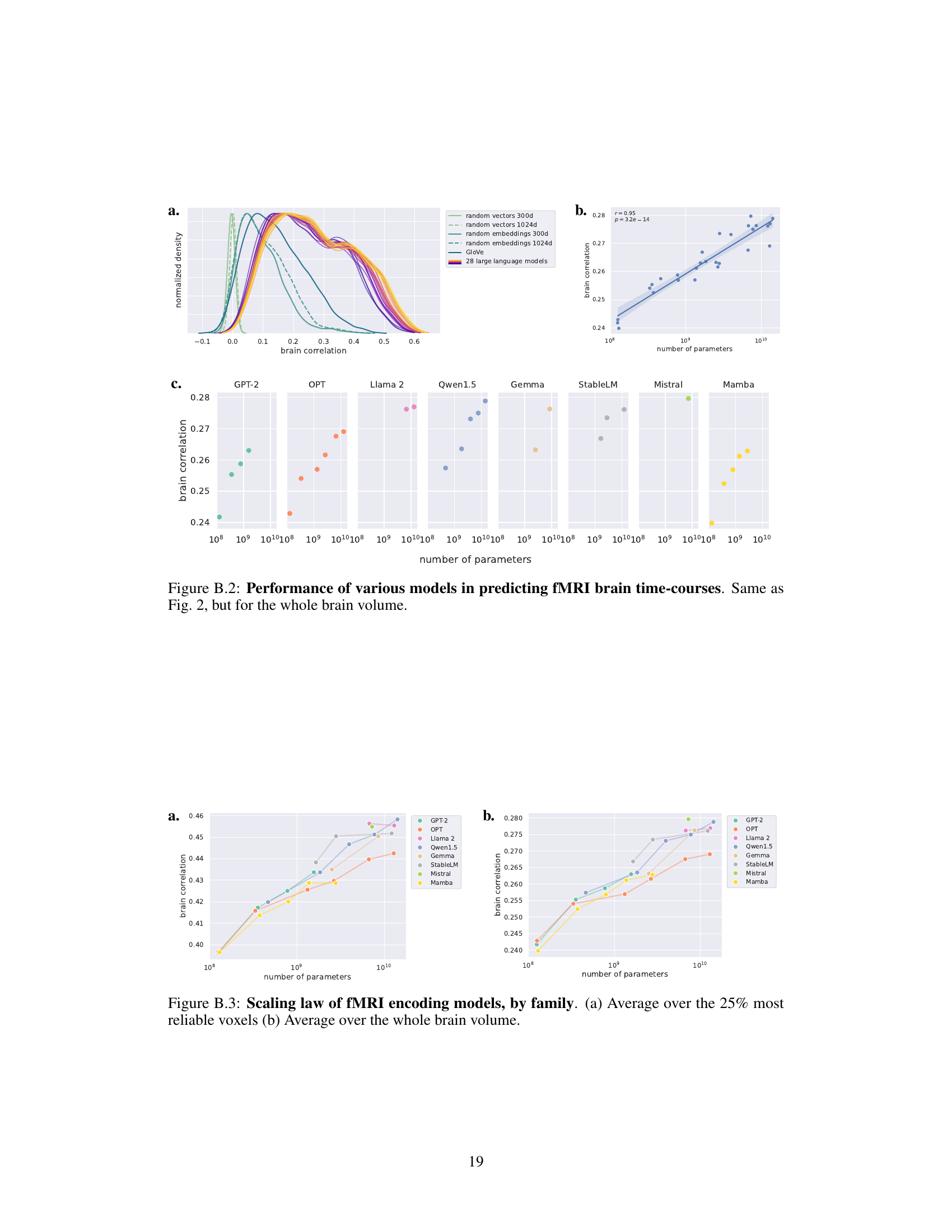

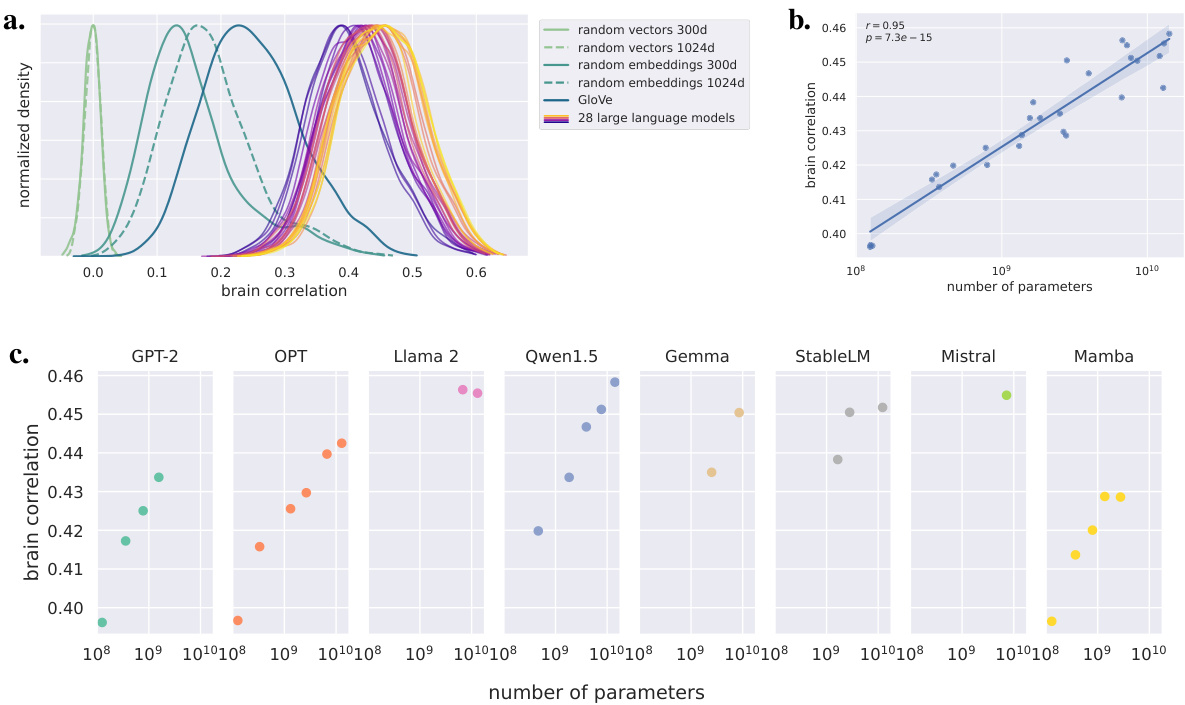

This figure displays the performance of various language models in predicting fMRI brain activity. Panel (a) shows the distribution of correlations between model predictions and brain activity for different models, including random baselines and GloVe embeddings. Panel (b) demonstrates a strong positive correlation between the model’s prediction performance and the logarithm of the number of parameters, indicating a scaling law. Panel (c) further breaks down this relationship by the family of language models, showing consistent scaling within each family but variations between families.

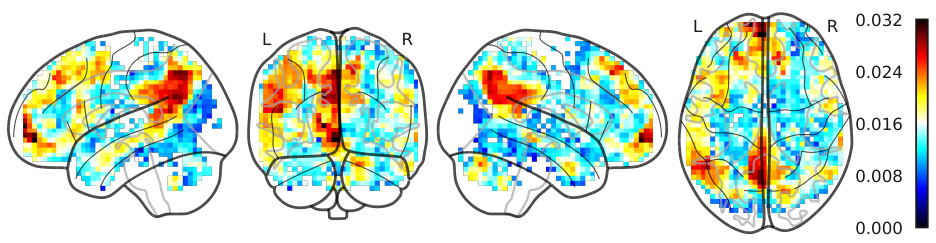

This figure shows the brain correlation maps for the smallest language model (GPT-2, 124M parameters) and the largest language model (Qwen1.5-14B, 14.2B parameters). The maps illustrate the difference in correlation (r-score) between the models’ predictions and the actual fMRI brain activity compared to a baseline model using random 1024-dimensional embeddings. The visualization reveals a more symmetrical pattern for the smaller model, while the larger model shows a clear left-hemisphere dominance for language processing. This difference highlights the emergence of left lateralization with increasing model complexity.

This figure shows brain correlation maps for two language models, one small (GPT-2) and one large (Qwen1.5-14B), in terms of their ability to predict fMRI brain activity. The difference in r-scores is shown, highlighting the increased correlation and asymmetry in the larger model relative to a baseline of random embeddings. The color scale represents the correlation between the model’s predictions and the observed brain activity.

This figure displays the relationship between the performance of language models on natural language tasks and their ability to predict fMRI brain activity. Panel (a) shows the correlation between brain activity and perplexity (a measure of model uncertainty) on the Wikitext-2 dataset. Panel (b) shows the correlation between brain activity and Hellaswag score (a measure of commonsense reasoning). Panel (c) focuses on the 10 largest models and shows the scaling relationship between model size and performance, and the relationship between model performance and brain correlation on both the Wikitext-2 and Hellaswag benchmarks.

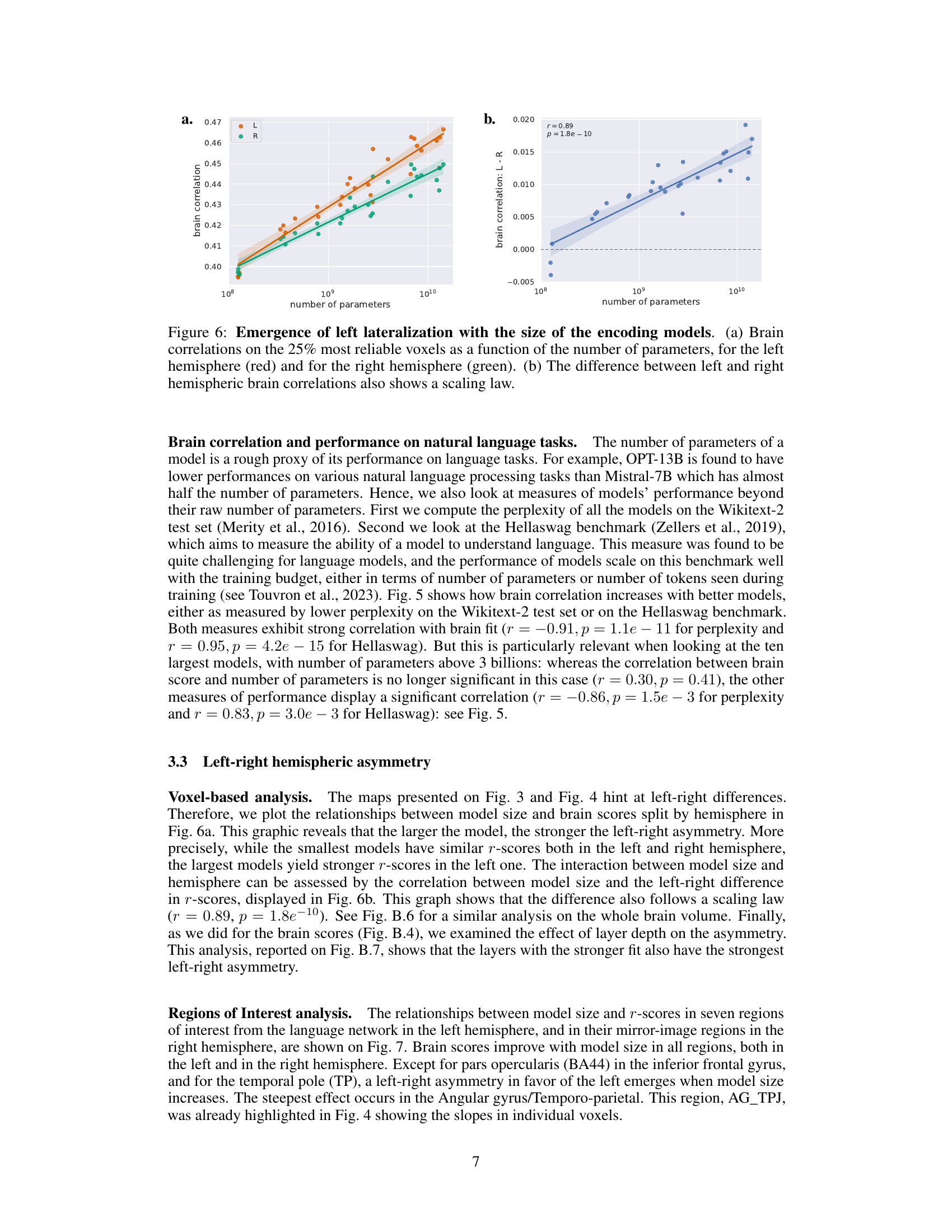

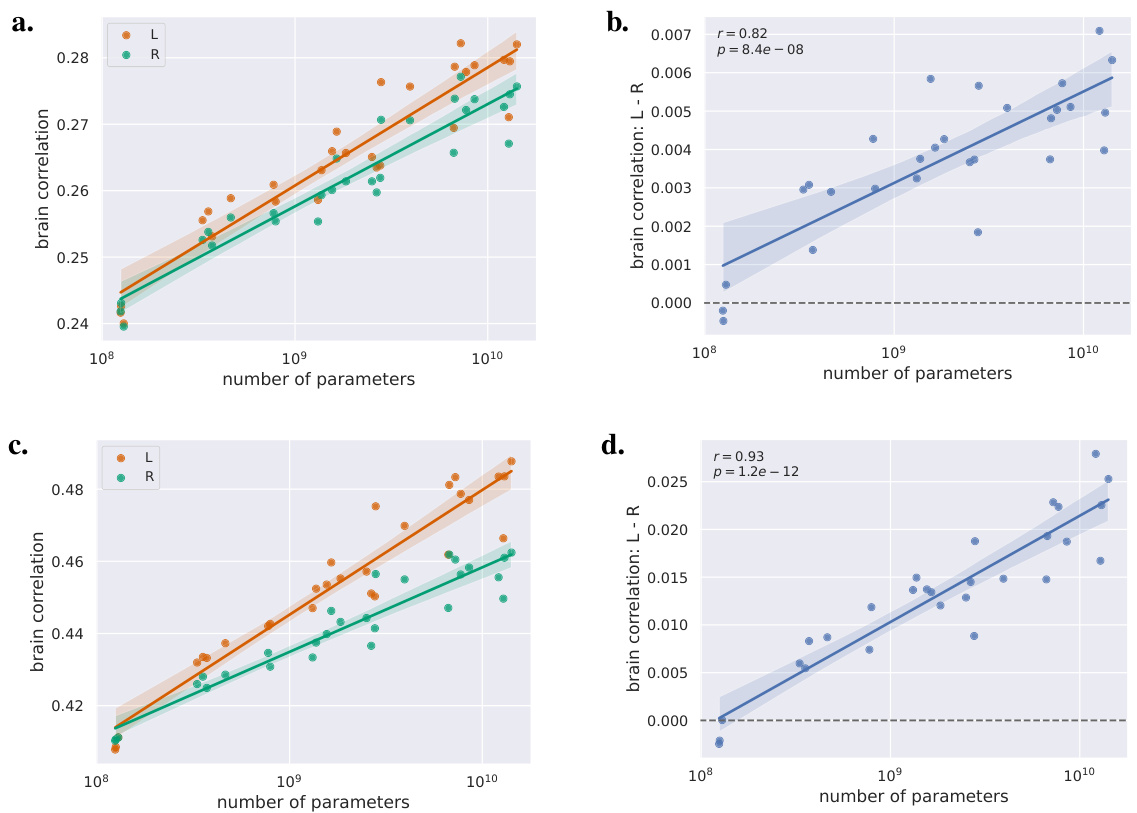

This figure shows two graphs. Graph (a) displays the relationship between the number of parameters of language models and their average correlation with brain activity in both the left and right hemispheres. It shows that as model size increases, brain correlations increase in both hemispheres but more strongly in the left. Graph (b) depicts the difference in brain correlation between the left and right hemispheres as a function of the number of parameters. This graph demonstrates that the left-right asymmetry increases as the language model’s complexity grows.

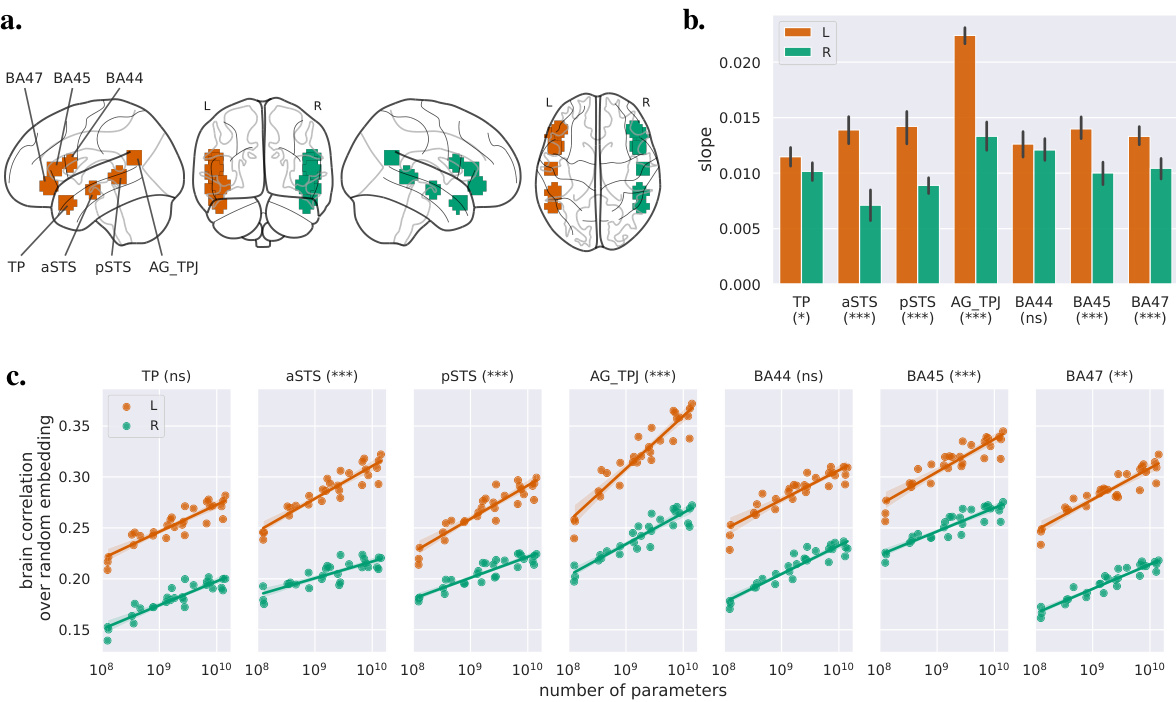

This figure shows the impact of the language model size on brain activity in seven regions of interest (ROIs) known to be involved in language processing. Panel (a) displays the locations of these ROIs. Panel (b) presents the slopes of the linear regression between the r-score (correlation between model predictions and brain activity) and the logarithm of the model’s number of parameters for each ROI, separately for the left and right hemispheres. The error bars represent 95% confidence intervals, and asterisks indicate the statistical significance of the difference in slopes between the hemispheres. Panel (c) shows the brain correlations (relative to a random baseline) as a function of model size for each ROI, and asterisks indicate the significance of the interaction between hemisphere and model size. The results indicate that larger models lead to stronger correlations with brain activity, and that this effect is more pronounced in the left hemisphere, especially in the aSTS, pSTS, AG/TPJ, BA45, and BA47 regions.

This figure shows the inter-subject reliability analysis. Panel (a) displays the distribution of inter-subject correlations, indicating the reliability of brain activity across participants. Panel (b) shows a glass brain representation of the 25% most reliable voxels, highlighting brain regions with high inter-subject correlation, which are further analyzed in the study.

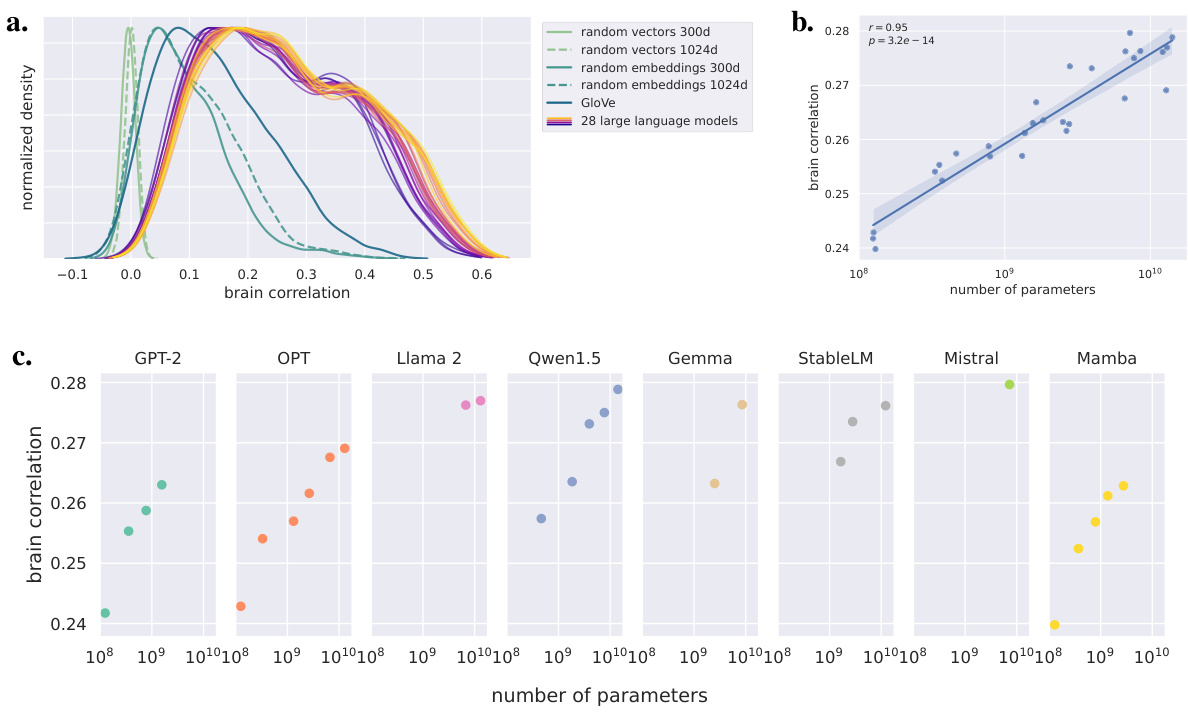

This figure shows the performance of different language models in predicting fMRI brain activity. Panel (a) compares the distribution of correlation coefficients (r-scores) for various models, including large language models and baselines. Panel (b) illustrates the relationship between the average r-score and the number of parameters (model size) in a logarithmic scale, demonstrating a scaling law. Panel (c) breaks down this relationship by the family of language models.

This figure displays the performance of various language models in predicting fMRI brain time courses. Panel (a) shows the distribution of correlation scores (r-scores) for each model, including baselines like random vectors and GloVe embeddings, compared to the 28 large language models. Panel (b) presents the average r-score as a function of the model’s number of parameters (log scale), revealing a scaling law. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval. Finally, panel (c) breaks down the results by model family, highlighting differences in performance across different language model architectures.

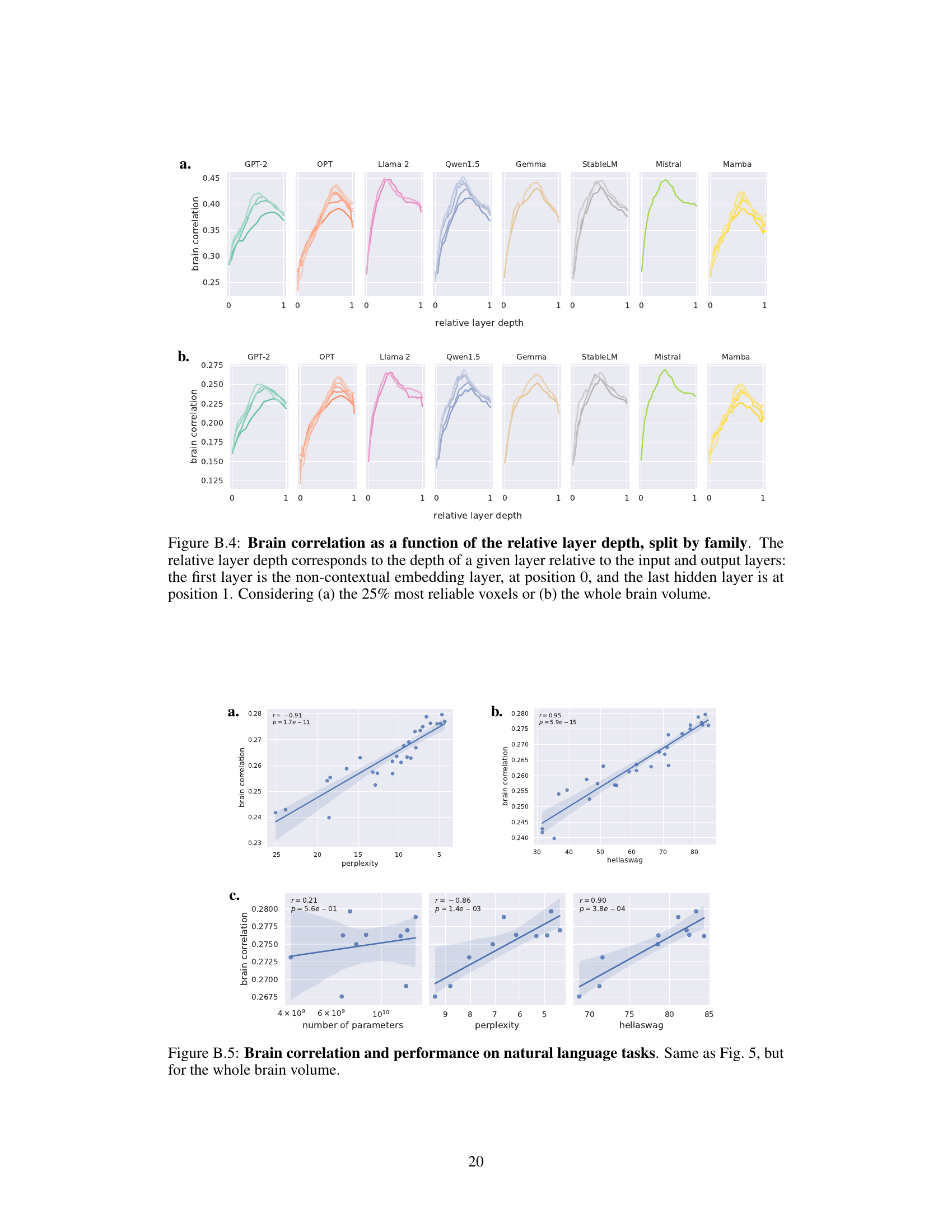

This figure shows the brain correlation as a function of the relative layer depth for each of the eight language model families used in the study. The x-axis represents the relative layer depth, where 0 is the embedding layer and 1 is the final hidden layer. The y-axis shows the brain correlation. Two subfigures are presented: (a) showing results for the 25% most reliable voxels and (b) for the whole brain volume. The figure illustrates the varying predictive power of different layers within each language model family regarding brain activity prediction.

This figure shows the performance of various language models in predicting fMRI brain activity. Panel (a) compares the distributions of correlation coefficients (r-scores) for different models, including large language models and baselines. Panel (b) illustrates a scaling law, where the average correlation increases linearly with the logarithm of the number of parameters in the model. Panel (c) breaks down this scaling law by model family, showing variations in performance across different model architectures.

This figure shows that as the size (number of parameters) of the language models increases, the correlation between model predictions and brain activity also increases, and this increase is more pronounced in the left hemisphere than in the right. Panel (a) displays the correlation for both hemispheres separately. Panel (b) shows the difference in correlations between the left and right hemispheres.

This figure shows the left-right difference in brain correlation as a function of the relative layer depth for different families of language models. The relative layer depth is a normalized measure of the layer’s position within the model, ranging from 0 (the embedding layer) to 1 (the last hidden layer). The figure is split into two subfigures: (a) shows the results for the 25% most reliable voxels, and (b) shows the results for the whole brain volume. The lines represent the average correlation for each layer, with shaded areas representing confidence intervals. This helps to visualize which layers of the models contribute most strongly to the left-right asymmetry in brain activity prediction.

This figure demonstrates the relationship between the size of language models and their ability to predict fMRI brain activity, showing a clear left-right asymmetry. Panel (a) displays brain correlations (average r-score) for the left and right hemispheres separately as a function of model size (number of parameters), revealing that larger models correlate better with brain activity in both hemispheres. More importantly, panel (b) shows the difference in correlations (left minus right) also increases with the number of parameters, clearly indicating that the left hemisphere’s correlation with model predictions becomes increasingly stronger than the right hemisphere’s with growing model size. This supports the notion of increasing left-hemisphere dominance for language with larger models.

This figure displays the results of the analysis on seven regions of interest (ROIs) related to language processing. Panel (a) shows the locations of the ROIs. Panel (b) shows the slopes of the linear regression between r-score (brain correlation) and the logarithm of the number of parameters in the model for each ROI, separated by hemisphere. Error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. The significance level of the difference between left and right hemisphere slopes is indicated. Panel (c) shows the brain correlations over the random embedding baseline as a function of the logarithm of the number of parameters. The significance level of the interaction between hemisphere and model size is indicated. Table A.2 contains detailed statistics for all results.

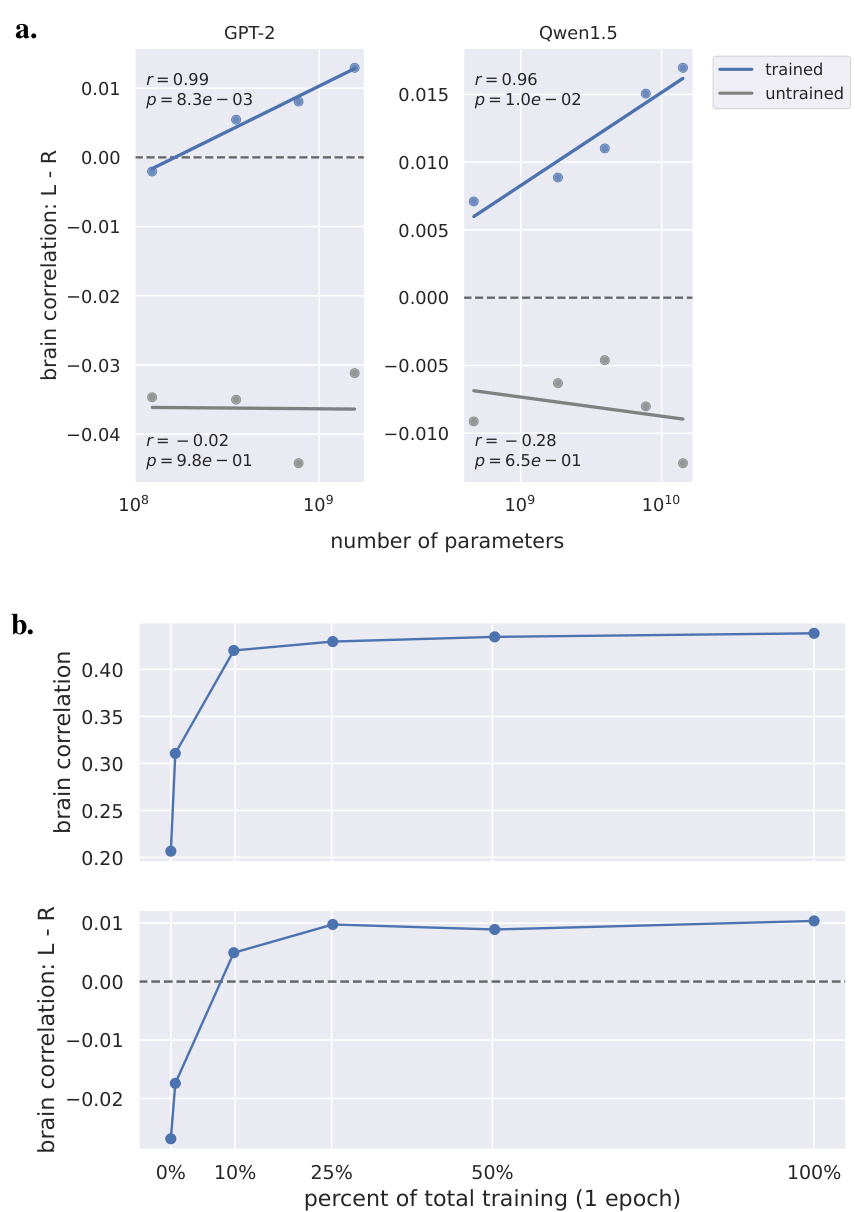

This figure displays the effect of model training on the left-right asymmetry observed in brain correlations. Panel (a) compares trained and untrained models from two different families (GPT-2 and Qwen-1.5), showing how the left-right difference increases with model size and training. Panel (b) shows the evolution of brain correlation and left-right asymmetry for a single model (Pythia-6.9B) during different stages of training, revealing a progressive shift towards left hemisphere dominance as training progresses.

This figure displays the inter-subject correlations in homologous cortical regions of the left and right hemispheres. Panel (a) shows the 48 cortical areas considered, based on the Harvard-Oxford atlas. Panel (b) shows the relationship between the inter-subject correlations in these regions, in the left and right hemispheres, respectively. Panel (c) displays the differences in correlations between the left and right regions. Statistical significance is indicated by stars (*: p<0.05; **: p<0.01; ***: p<0.001).

This figure displays the inter-subject correlation analysis, which is a model-free way to evaluate signal-to-noise ratio. It shows the distribution of inter-subject correlations, a brain representation of the reliable voxels, and a bar plot showing the correlation between left and right homologous regions. The analysis reveals a significant relationship between correlations in the left and right homologous regions, with a tendency toward stronger correlations in the left than in the homologous right regions.

This figure shows the individual analysis of five participants. The authors used nine large language models from the GPT-2 and Qwen-1.5 families to analyze the brain correlation with different model sizes. The results are presented in five sub-figures. (a) shows the brain correlation in the whole brain for each participant. (b) shows brain correlation for the left and right hemispheres, respectively. (c) illustrates the difference in brain correlation between the left and right hemispheres for each participant. (d) and (e) repeat the analysis in (b) and (c) but focus only on the best 10% of voxels in each hemisphere.

Full paper#