↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The ability of AI to plan and reason about actions is a significant challenge. Chess, a complex planning problem, has often been studied to address this challenge. Existing methods, however, often rely on computationally expensive search algorithms or are limited by the size of available datasets. This work tackles these issues.

This research introduces ChessBench, a large-scale benchmark dataset for chess, and trains large transformer models on this dataset to predict optimal moves. Surprisingly, these searchless models achieve strong performance, rivaling grandmasters, without explicit search and demonstrating highly non-trivial generalization. This suggests that large-scale transformers can capture complex planning strategies.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI researchers because it introduces a large-scale benchmark dataset for chess planning, directly addressing the limitations of existing datasets and pushing the boundaries of what’s possible with transformer models. It also presents a novel approach to evaluating the ability of AI systems to plan ahead without explicit search, opening up new avenues for future research in AI planning and general AI.

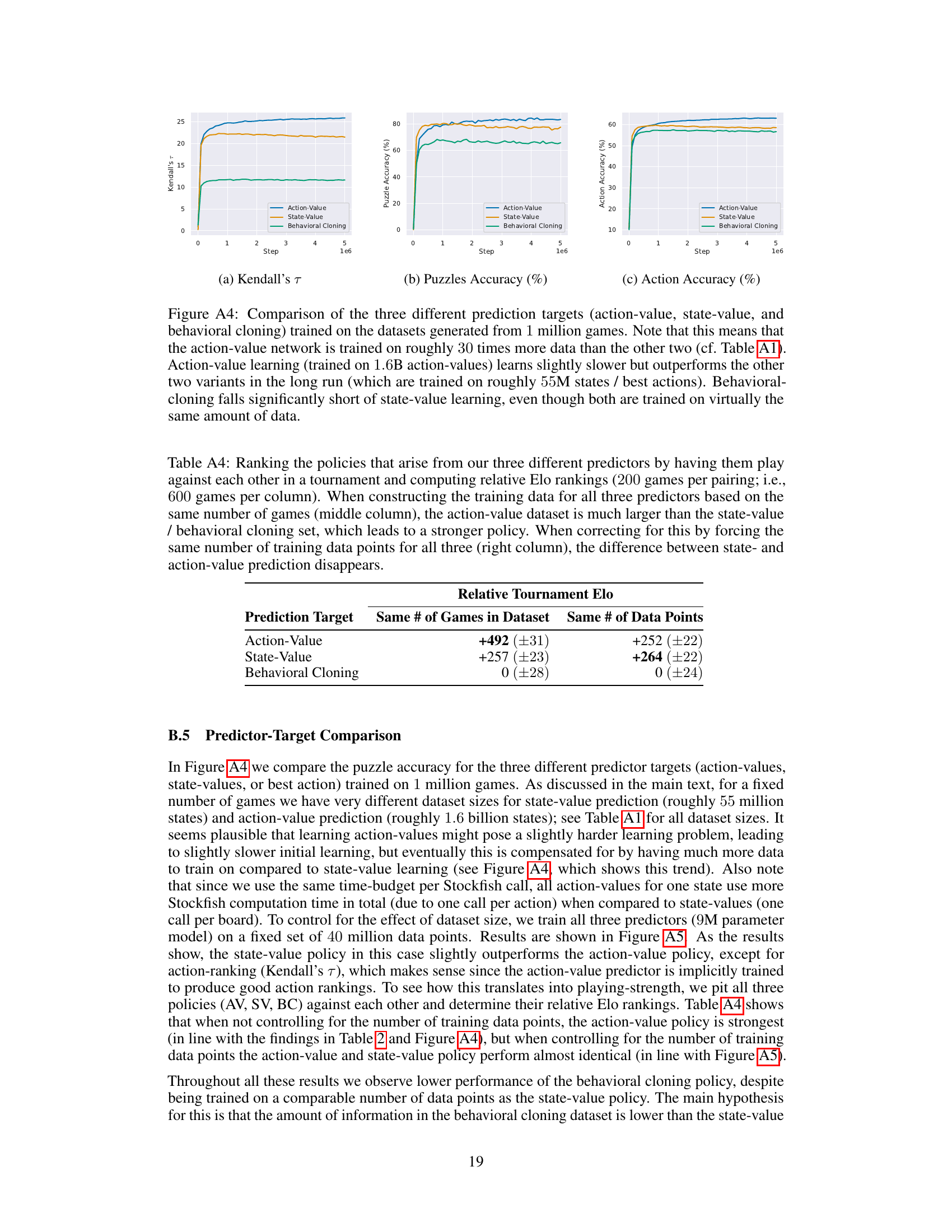

Visual Insights#

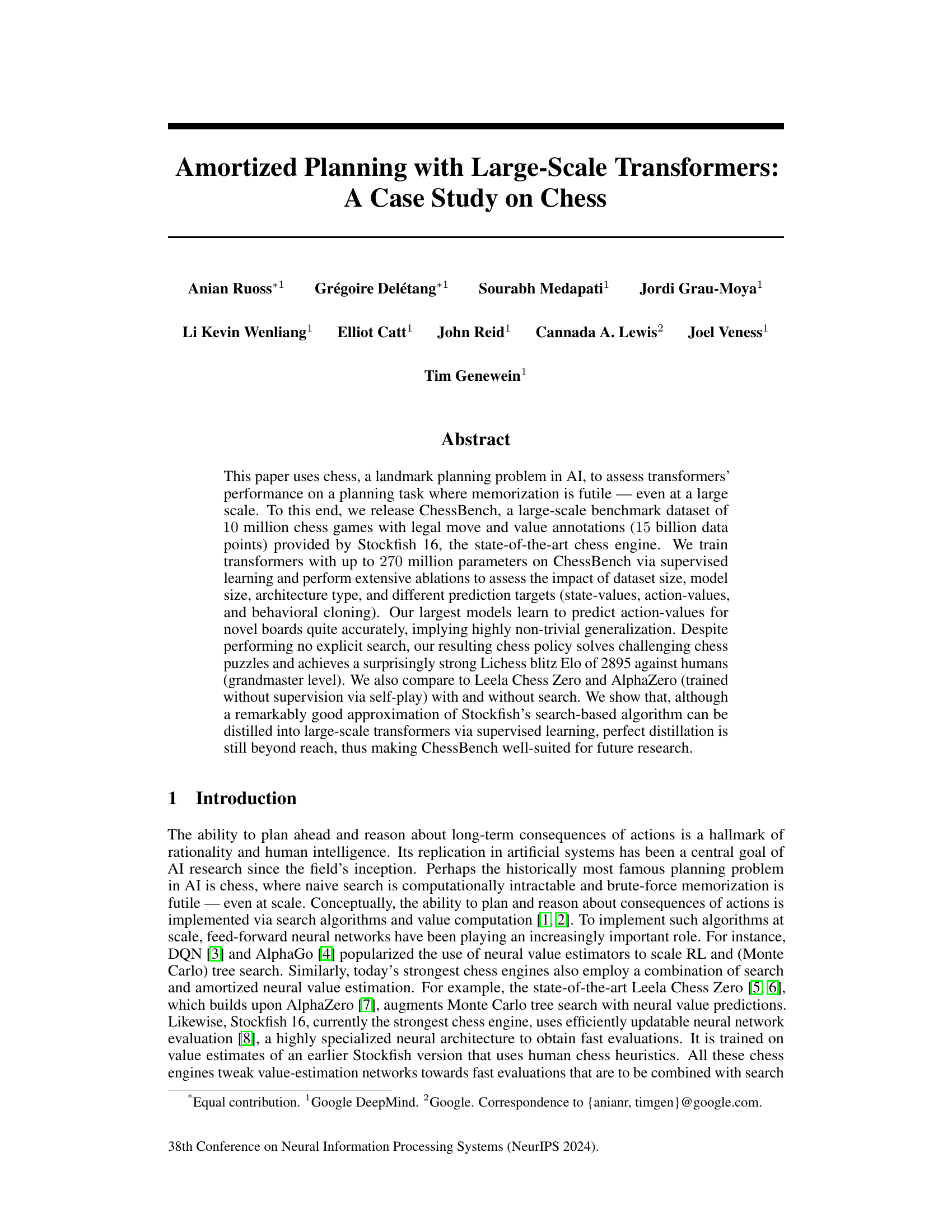

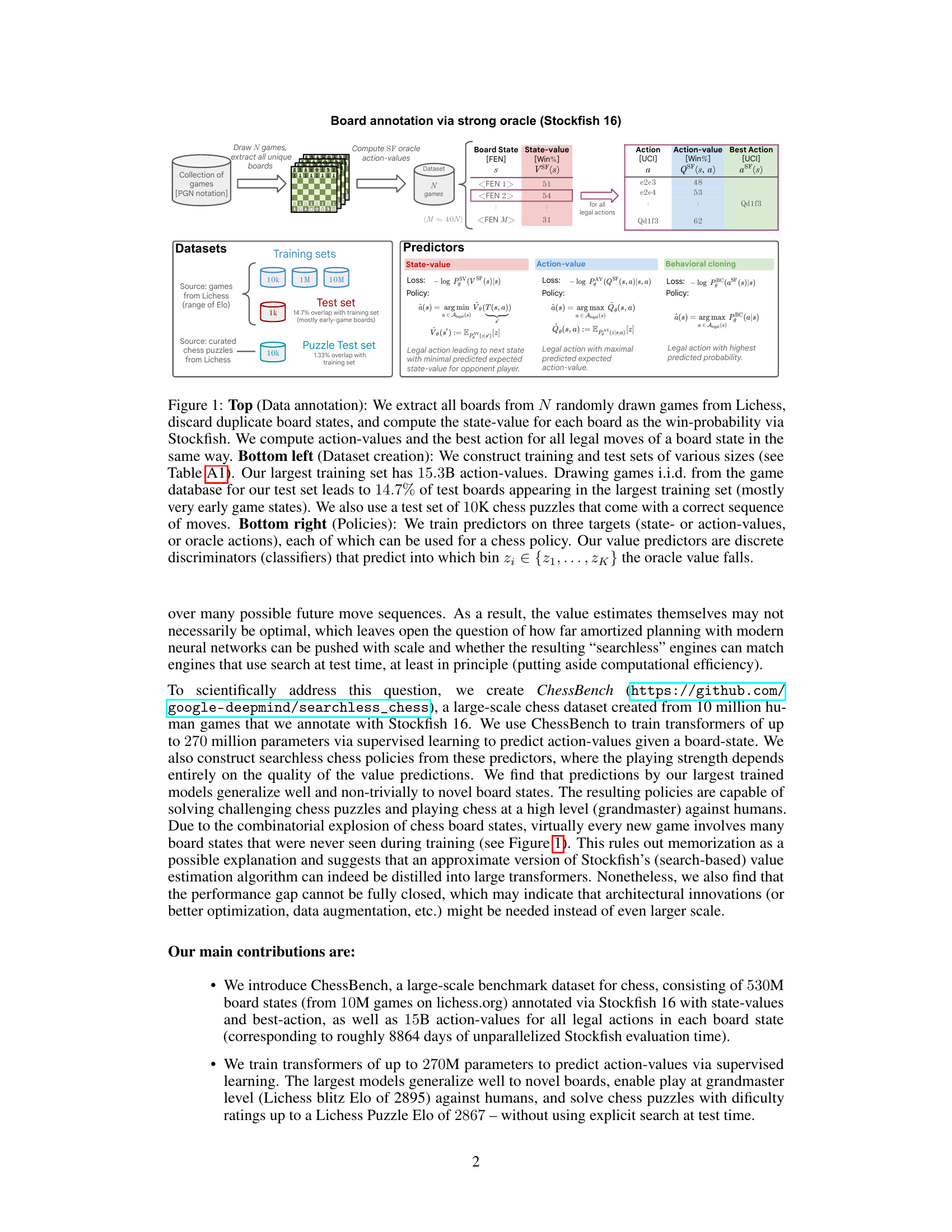

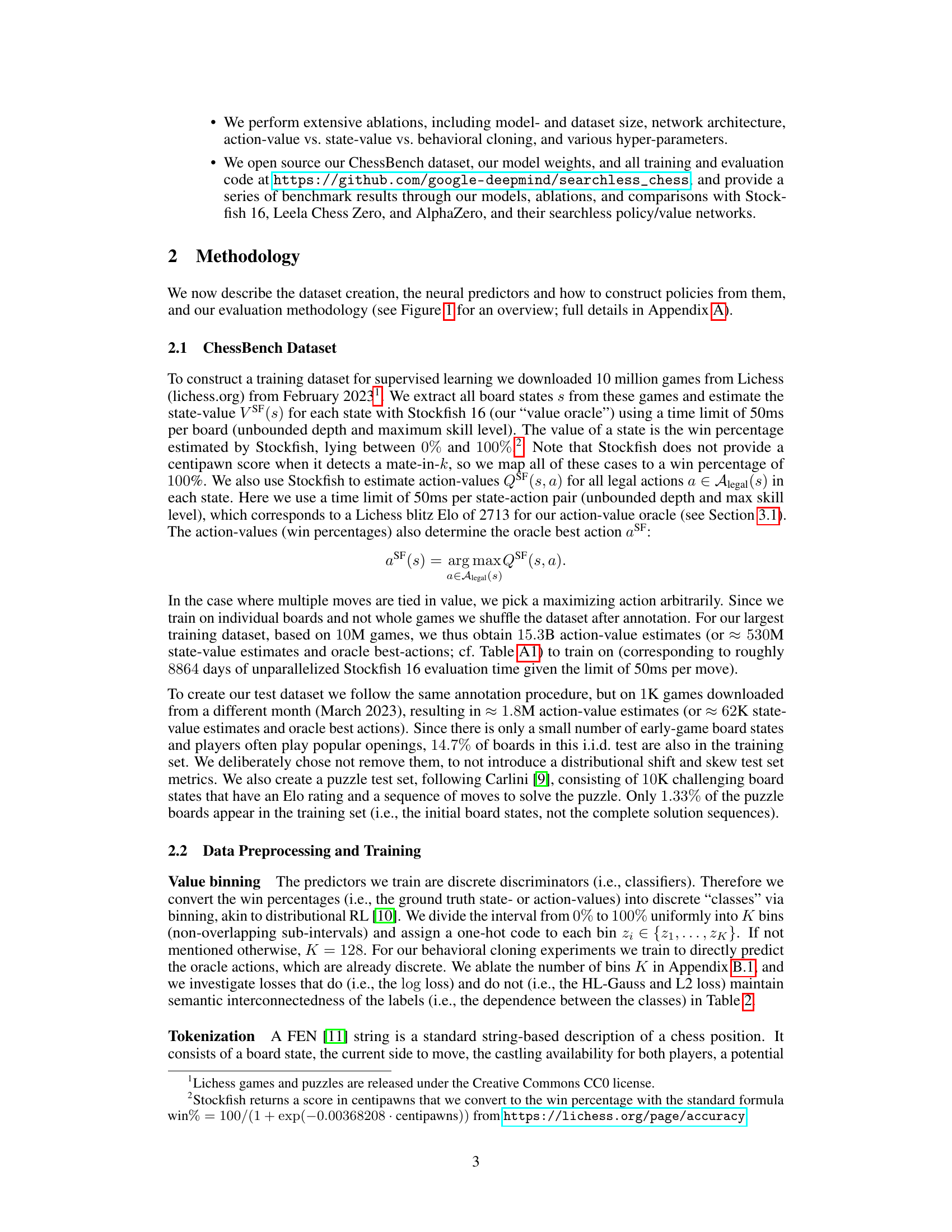

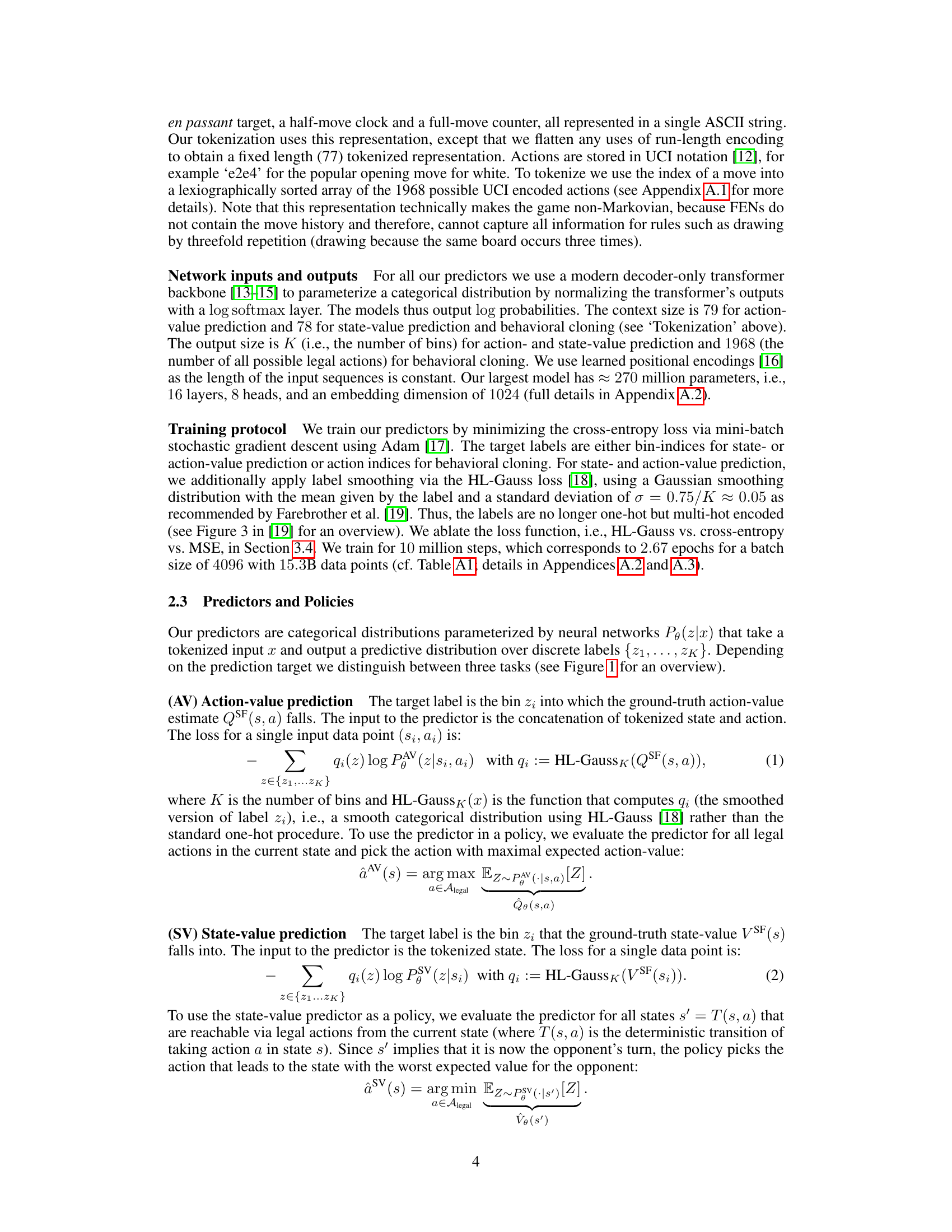

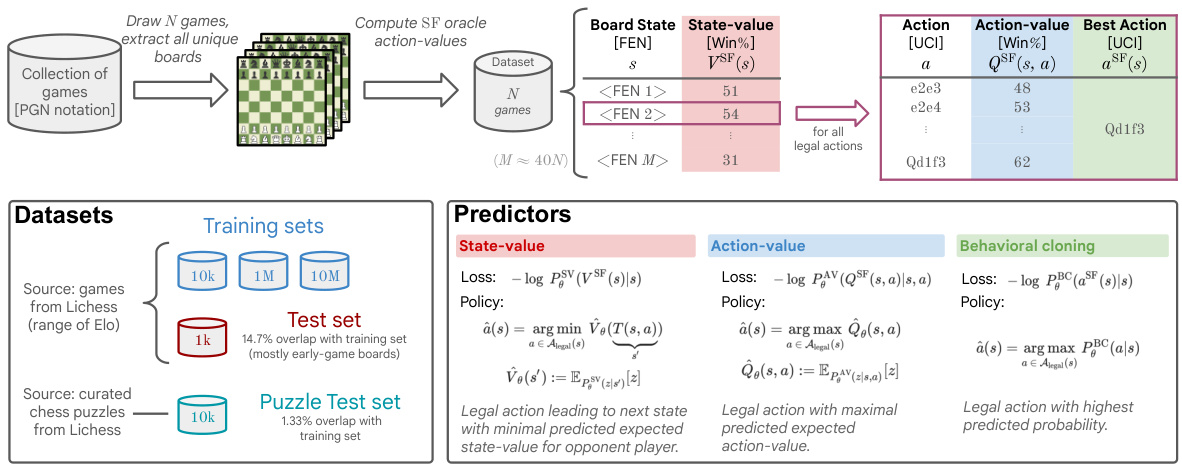

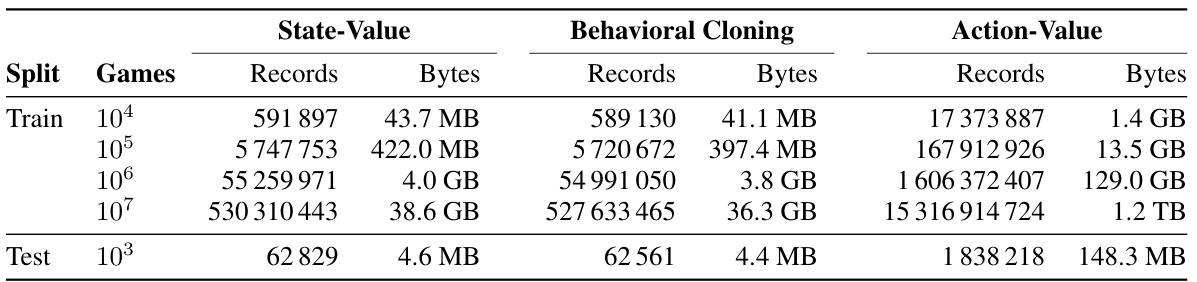

This figure details the data annotation process, dataset creation, and policy training process for the ChessBench dataset. The top section shows how board states and actions are annotated using Stockfish 16. The bottom left shows how the dataset is created, including the split into training and test sets of various sizes. The bottom right details the three types of predictors (state-value, action-value, and behavioral cloning) trained, and how these are used to create chess policies. The figure highlights the use of both game data from Lichess and curated chess puzzles to create the comprehensive dataset.

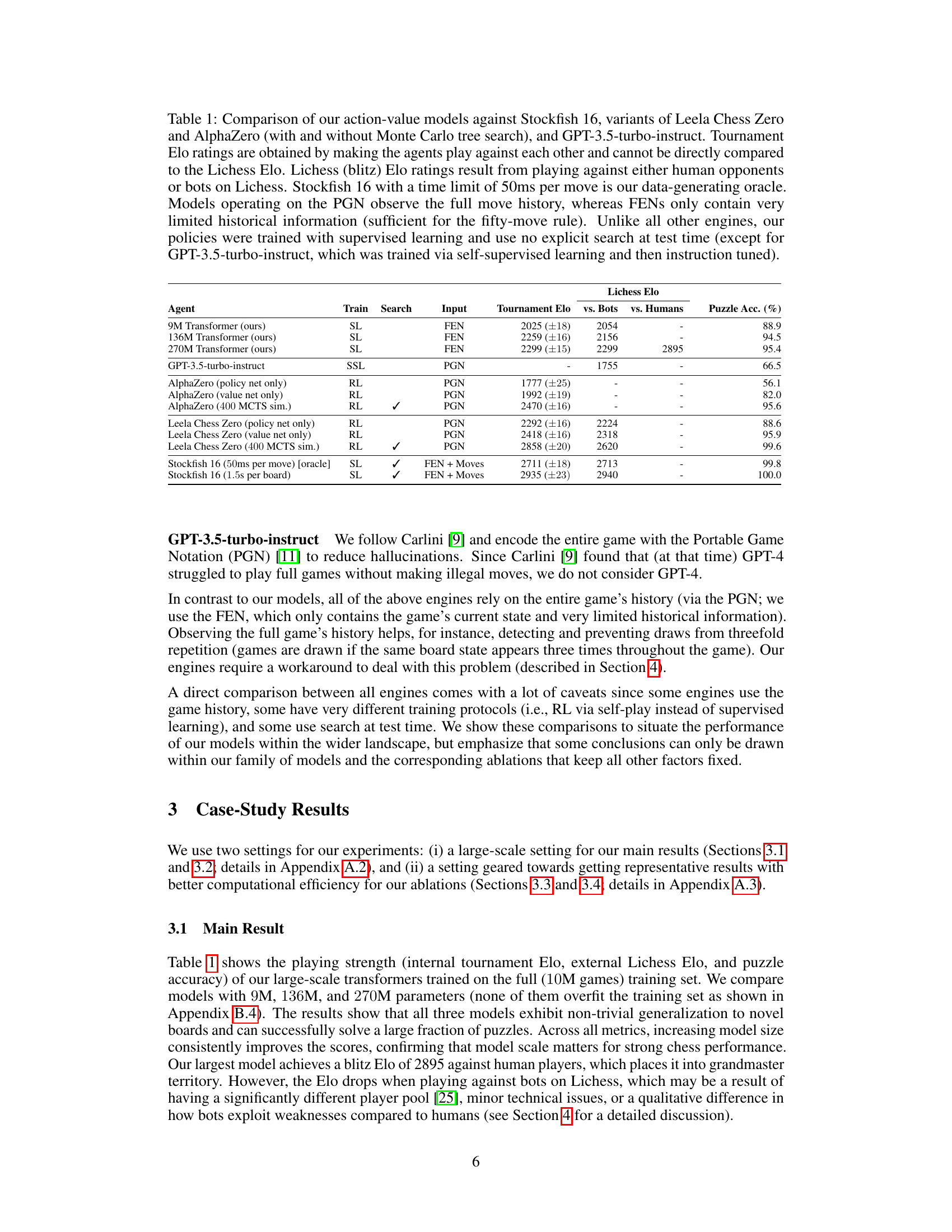

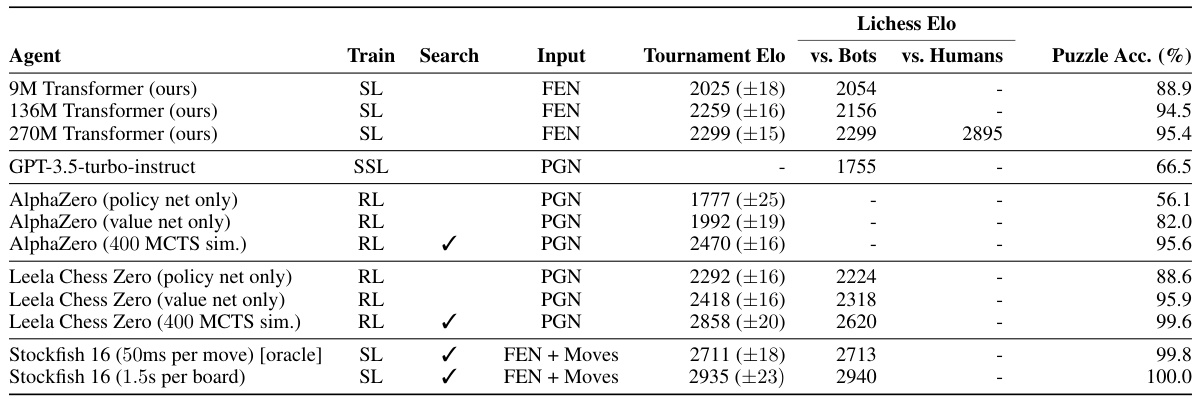

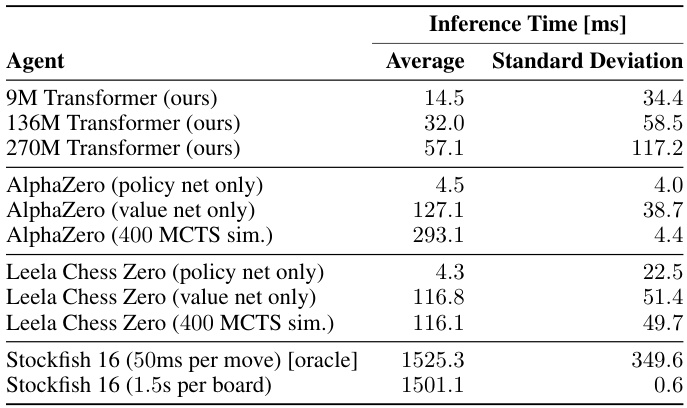

This table compares the performance of the authors’ action-value models against several other chess engines, including Stockfish, AlphaZero, and Leela Chess Zero. It shows the tournament Elo ratings (from matches against other engines), Lichess Elo ratings (from games against humans and bots), and puzzle accuracy for each engine. It highlights the fact that the authors’ models use no explicit search at test time, in contrast to most other engines, and were trained via supervised learning.

In-depth insights#

Chess Transformer#

The concept of a “Chess Transformer” is intriguing, suggesting the application of transformer neural networks to the game of chess. This approach likely involves using a transformer model to process chessboard states (represented as numerical or tokenized sequences) and predict optimal moves or game outcomes. A key advantage would be the potential for powerful generalization, allowing the model to play effectively even on previously unseen board positions. The approach contrasts with traditional chess AI which often relies heavily on explicit search algorithms. However, the success of a Chess Transformer heavily depends on the quality of training data and model architecture. Sufficiently large datasets of chess games, including annotations of move quality and outcome, would be essential for effective training and generalization. A successful Chess Transformer could potentially achieve strong performance without the computational demands of brute-force search algorithms, marking a significant advance in AI-based game playing.

Supervised Learning#

Supervised learning, in the context of the research paper, plays a crucial role in training transformer models for chess. The approach involves using a large dataset of chess games, annotated with move evaluations from a strong chess engine, to train the model to predict the optimal move given a game state. This is a powerful technique because it leverages the expertise of existing, high-performing chess engines to guide the learning process. Unlike reinforcement learning methods, such as AlphaZero’s self-play, supervised learning avoids the need for extensive trial and error, significantly reducing computational costs. The success of this approach demonstrates the potential of supervised learning for efficiently distilling the knowledge of complex systems into neural networks. However, a limitation is that the model’s performance is intrinsically limited by the quality of its training data. Therefore, the accuracy of the chess engine used for annotations directly impacts the model’s effectiveness.

ChessBench Dataset#

The ChessBench dataset represents a significant contribution to the field of AI research, particularly in the area of game playing and planning. Its large scale, encompassing 10 million games and 15 billion data points, addresses the limitations of previous datasets by providing sufficient data to train large-scale models effectively. The annotation process, utilizing the state-of-the-art chess engine Stockfish 16, ensures high-quality labels for both state-values and action-values. This comprehensive labeling makes the dataset suitable for training models that go beyond simple memorization, encouraging true generalization and planning capabilities. The inclusion of diverse data, such as games from various Elo ranges and curated puzzles, ensures the dataset’s robustness and its capacity to evaluate diverse model capabilities, furthering the possibilities of AI research in game playing. The dataset’s public availability promotes collaborative research and accelerates progress in the field.

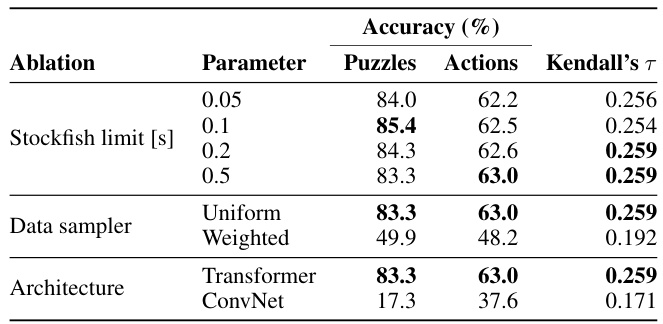

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model or system to assess their individual contributions. In the context of this research paper, ablation studies would likely involve isolating and removing different elements of the transformer model (layers, attention heads, etc.) or the training process (dataset size, loss function, hyperparameters) to analyze their effect on the model’s overall performance. By carefully measuring the impacts on various evaluation metrics, such as puzzle-solving accuracy, playing strength, and generalization, the authors would gain crucial insights into the importance of different model components and training strategies. Identifying components that significantly affect performance is key to improving future designs, pinpointing critical aspects of the architecture, and ultimately leading to potentially more efficient and effective models. Understanding the trade-offs between different components, especially in relation to computational costs, is essential for practical applications. The detailed results of such ablation experiments, meticulously documented, would provide valuable support to the overall conclusions of the study.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several avenues. Improving the model’s ability to handle long-term planning and complex strategic scenarios is crucial, potentially through architectural modifications or training methodology advancements beyond simple supervised learning. Investigating the use of reinforcement learning, particularly self-play, might allow the model to discover novel strategies and further refine its understanding of the game’s dynamics. Another important area is reducing the reliance on a computationally expensive oracle like Stockfish; creating methods for generating more efficient training data or incorporating alternative evaluation schemes could significantly improve the model’s scalability and efficiency. Finally, extending the model’s capabilities to other complex planning tasks beyond chess would test the generalizability of this approach and its applicability to various AI challenges.

More visual insights#

More on figures

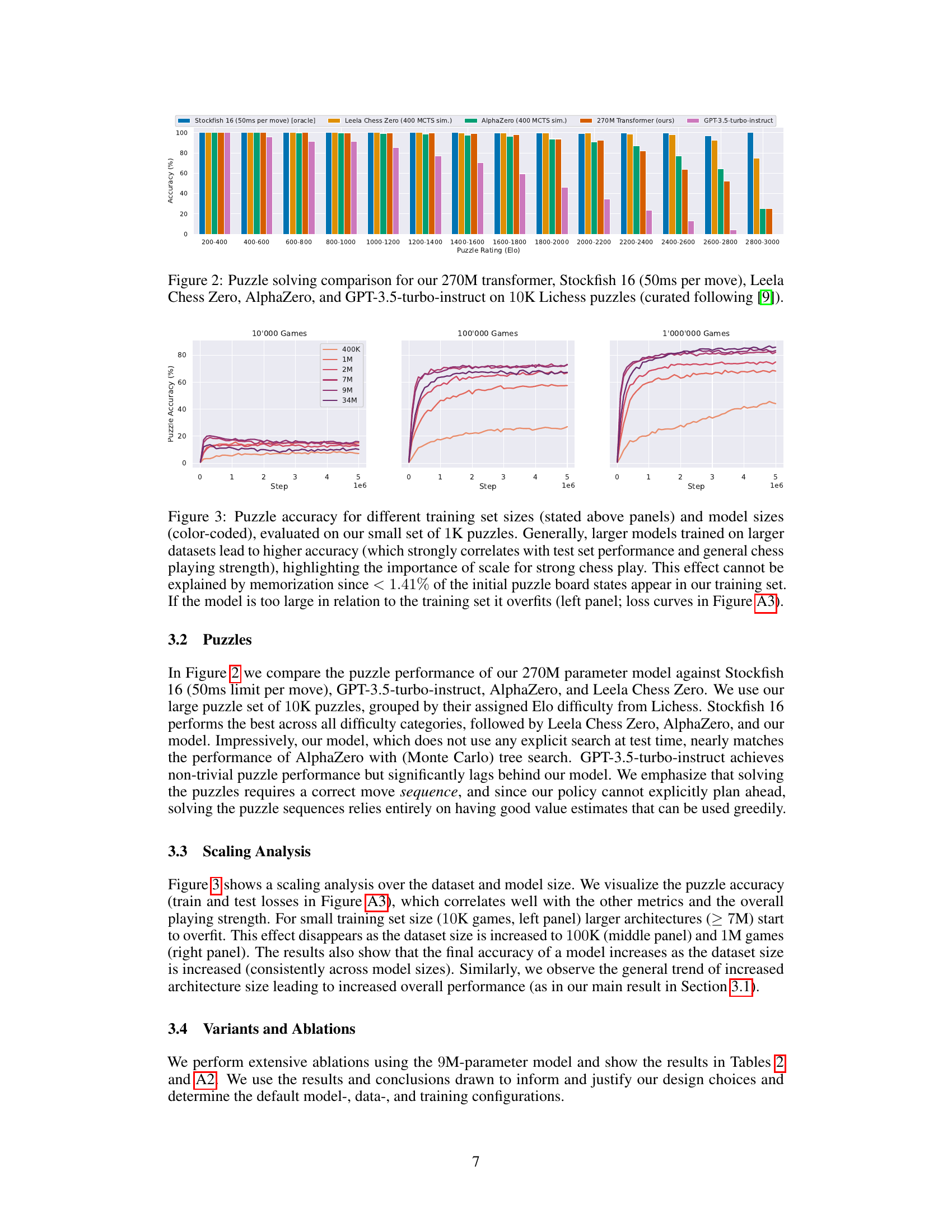

This figure compares the puzzle-solving performance of the 270M parameter transformer model against several other strong chess engines, including Stockfish 16 (with a 50ms time limit per move), Leela Chess Zero, AlphaZero, and GPT-3.5-turbo-instruct. The comparison is performed on a set of 10,000 curated Lichess puzzles, grouped by their Elo difficulty ratings. The figure shows the accuracy of each model in solving puzzles within different Elo rating ranges. The results demonstrate the remarkable performance of the transformer model, even without using explicit search during testing, especially in comparison to GPT-3.5-turbo-instruct.

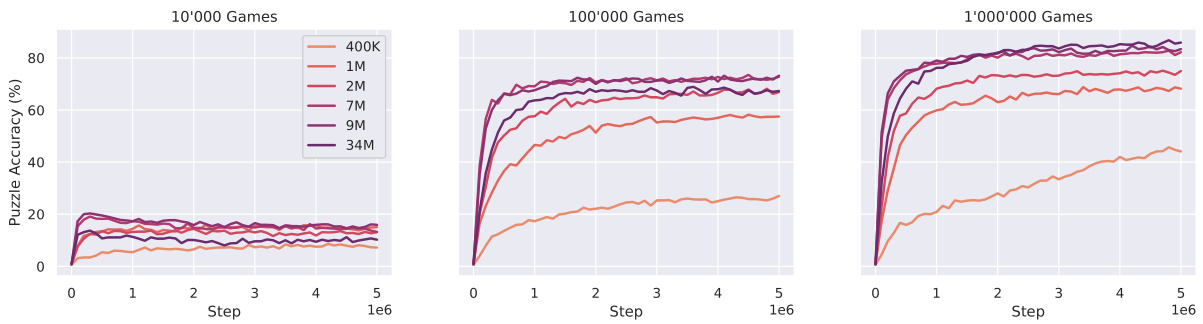

The figure shows the puzzle accuracy for different training set sizes and model sizes. It demonstrates that larger models trained on more data achieve higher accuracy. This is not due to memorization as only a small percentage of the test puzzles were in the training data. Overfitting is observed with the largest models on smaller datasets.

This figure illustrates the process of creating the ChessBench dataset and training three different types of predictors (state-value, action-value, and behavioral cloning). The top section shows the annotation process using Stockfish, while the bottom left shows the dataset creation with training and test sets of varying sizes. The bottom right describes the three policy training methods with their respective loss functions.

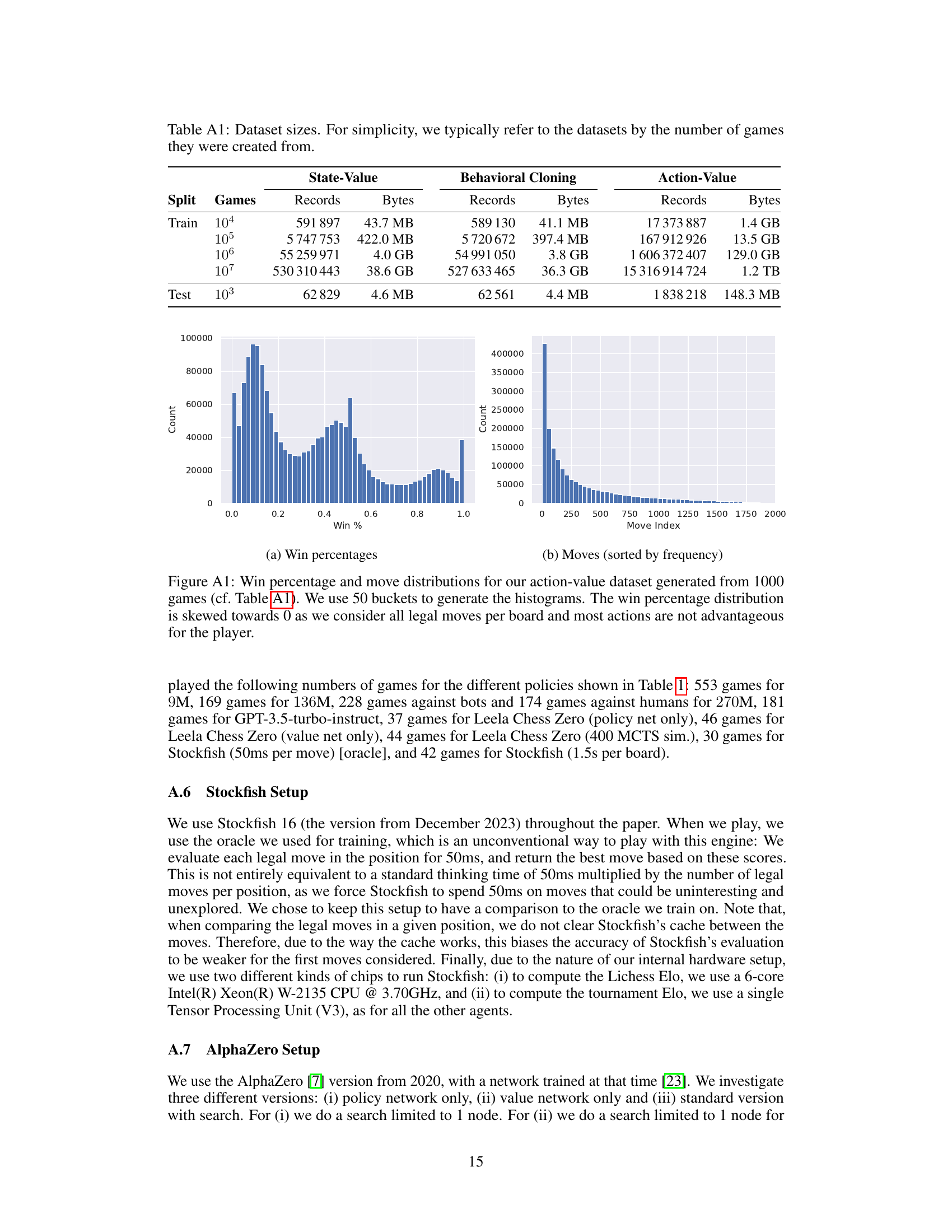

This figure shows the distribution of win percentages and move frequencies in a subset of the ChessBench dataset. The win percentage histogram demonstrates a skew towards 0%, reflecting that many moves in chess are not advantageous for the player. The move frequency plot provides insights into common moves at different stages of a game. Both distributions help to characterize the data used for training the transformer models.

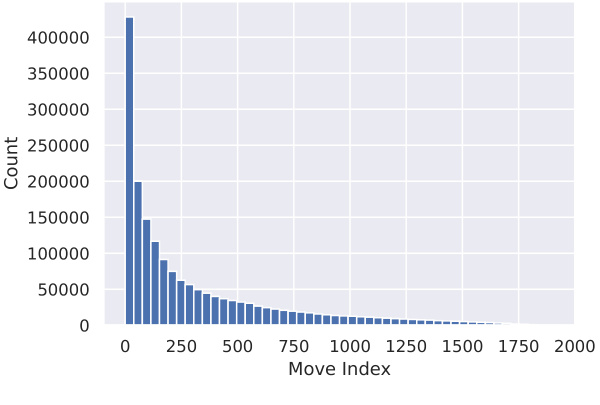

This figure shows two histograms. The first one visualizes the win percentage distribution of the dataset, which is heavily skewed towards 0%. This is because the dataset includes all legal moves, and most moves are not advantageous for the player. The second histogram displays the frequency of different moves in the dataset. The x-axis represents the move index, and the y-axis represents the count of the move. The distribution shows that some moves appear significantly more often than others.

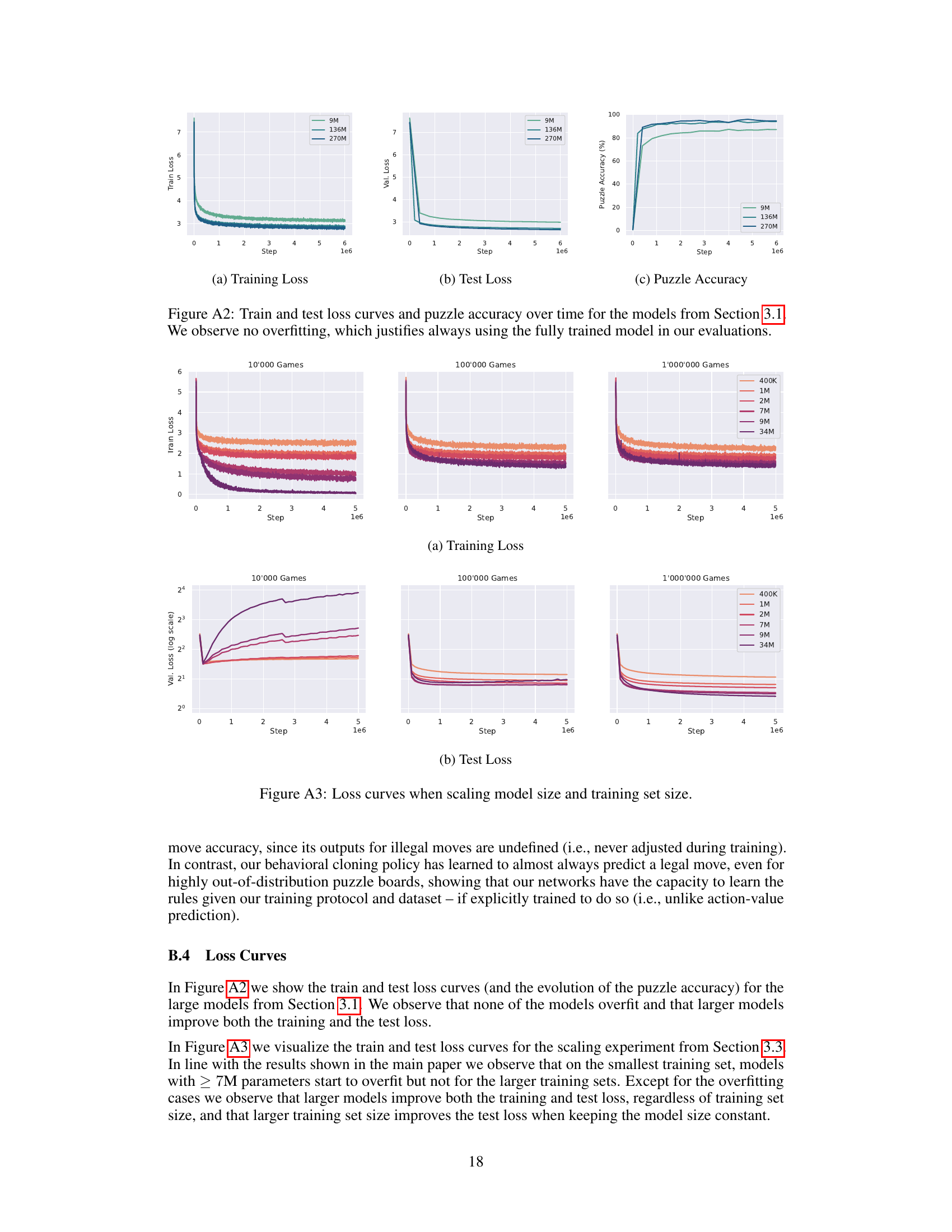

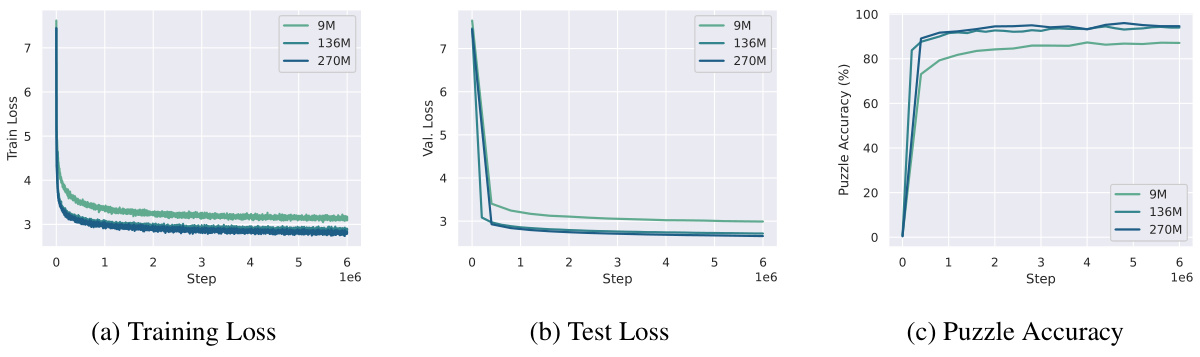

This figure displays the training and testing loss curves, as well as the puzzle accuracy over time, for the three transformer models (9M, 136M, and 270M parameters) described in Section 3.1 of the paper. The consistent decrease in both training and testing loss across all models indicates a lack of overfitting. The steady improvement in puzzle accuracy further reinforces the effectiveness of the training process. The absence of overfitting supports the authors’ decision to use the fully trained models in their evaluations, which is a common practice in machine learning to avoid bias from incomplete training.

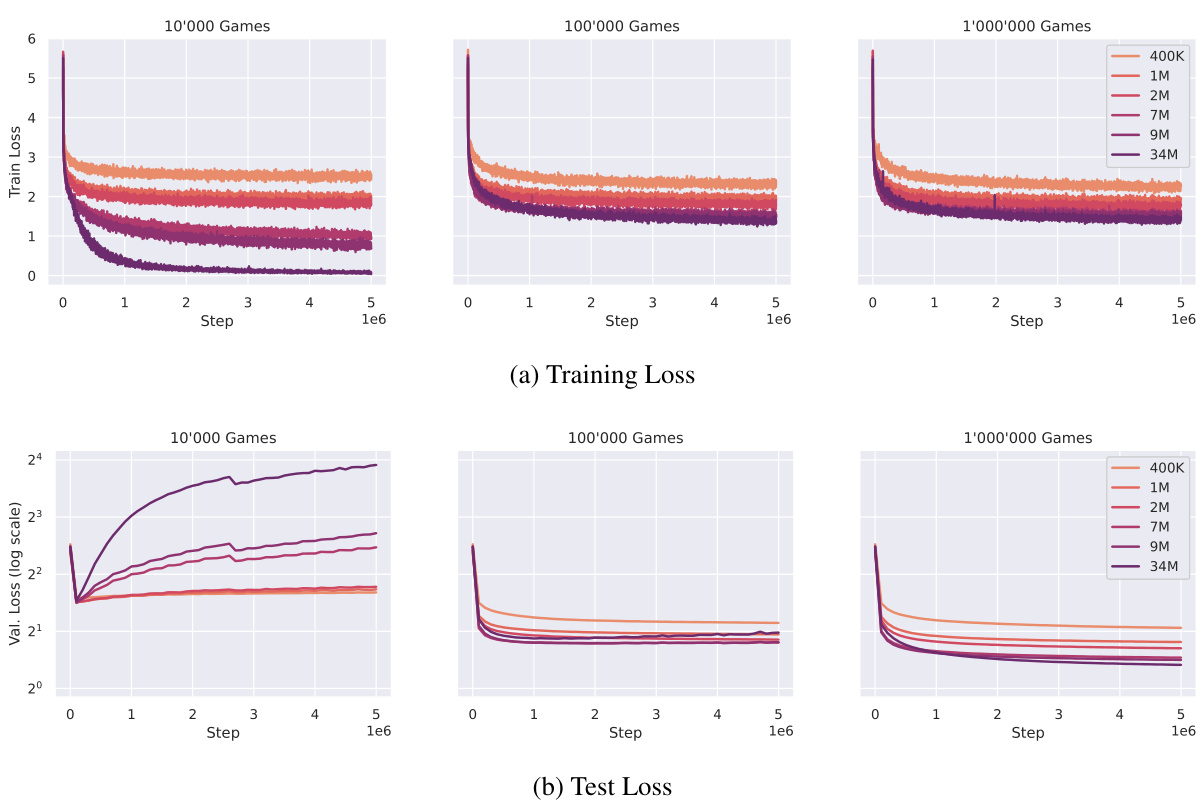

This figure shows the training and test loss curves for different model sizes (400K, 1M, 2M, 7M, 9M, 34M parameters) trained on different training set sizes (10K, 100K, 1M games). It demonstrates the impact of model and dataset size on model performance and the presence of overfitting for larger models trained on smaller datasets. The results show that larger models generally perform better, but only when there is enough training data to prevent overfitting.

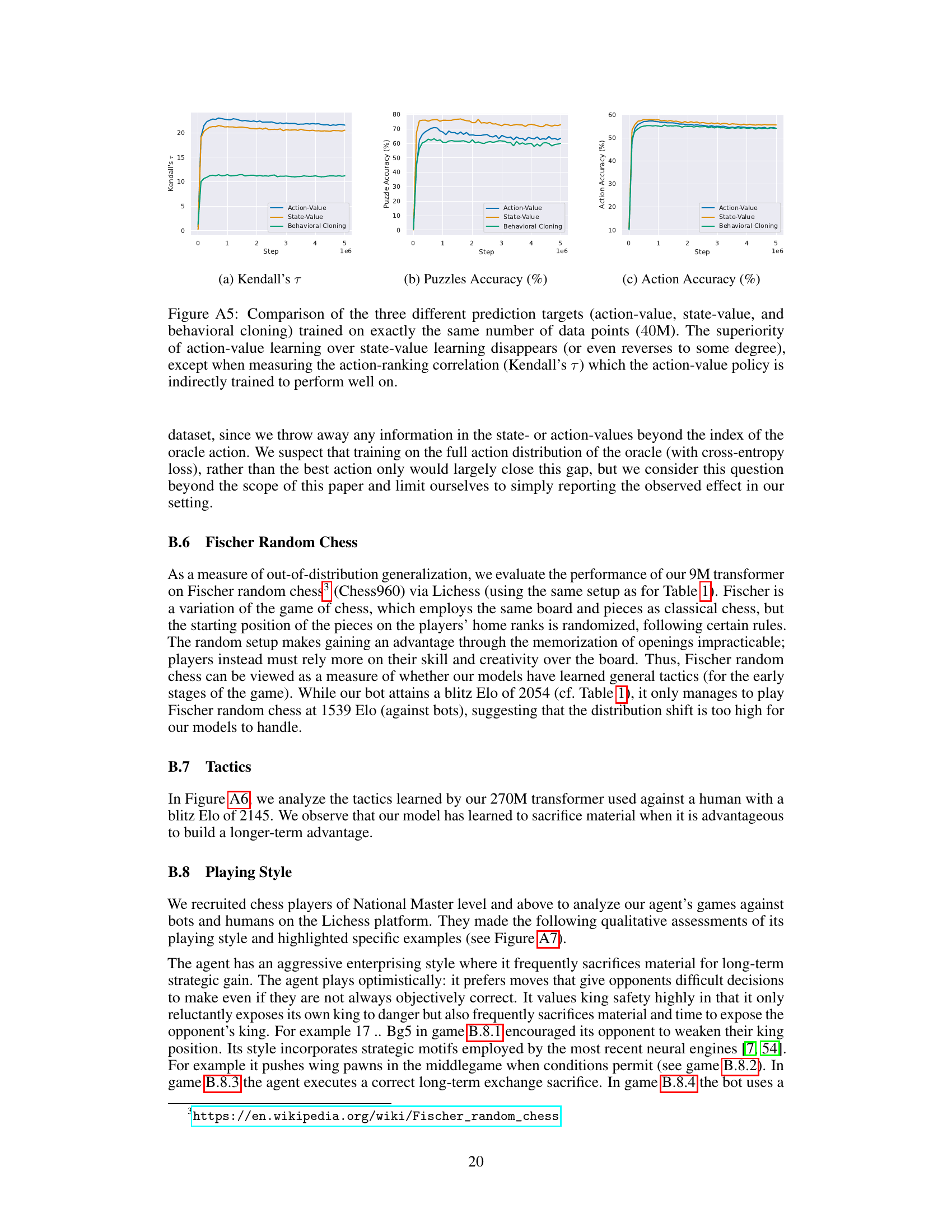

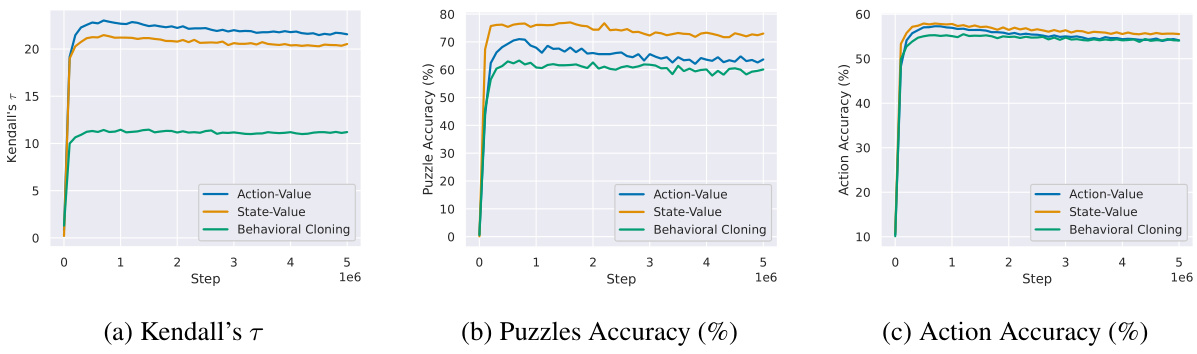

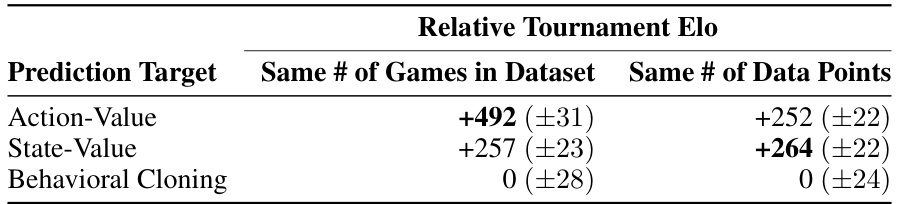

This figure shows the result of an ablation study on the effect of different prediction targets (action-value, state-value, and behavioral cloning) when the training data size is controlled. The results show that when the amount of training data is the same for all three targets, the superiority of the action-value approach diminishes. The action-value predictor still outperforms others in terms of Kendall’s Tau, which measures rank correlation, suggesting that the action-value target is still better at ranking actions.

This figure compares the performance of three different prediction targets (action-value, state-value, and behavioral cloning) when trained on the same amount of data. It shows that the action-value and state-value predictors perform similarly when given equal data, unlike what was observed when the datasets for each model were of differing sizes (Figure A4). The behavioral cloning method underperforms consistently.

This figure shows the process of creating the ChessBench dataset and training three different predictors: state-value, action-value, and behavioral cloning. The dataset is created by extracting unique board states from Lichess games and annotating them with state values and action values from Stockfish. Three different predictors are trained using this dataset, each with a different prediction target and loss function. The figure also shows the datasets used, including training and testing sets, and the policies generated for each predictor.

This figure illustrates the data annotation process, dataset creation, and policy training methods used in the paper. The top section shows how board states and actions are annotated using Stockfish, a strong chess engine. The bottom left shows the creation of training and test datasets of various sizes, highlighting the inclusion of chess puzzles as a test set. The bottom right illustrates the three different supervised learning approaches used to train the neural network predictors: predicting state values, action values, and behavioral cloning, and shows how the output of each predictor is used to create a chess playing policy.

This figure describes the data annotation, dataset creation, and training policies used in the ChessBench study. The top section illustrates how board states and their values (state-value and action-value) are extracted from Lichess games using Stockfish as an oracle. The bottom left shows the creation of training and testing datasets of varying sizes from this data, highlighting the overlap between training and test sets. The bottom right details the three different prediction targets (state-value, action-value, and behavioral cloning) used to train the transformer models and the resulting policies.

This figure illustrates the process of creating the ChessBench dataset and training three different types of predictors. The top section shows how board states and their corresponding values (state-value, action-value, and best action) are extracted from Lichess games using Stockfish. The bottom left section details the creation of the training and testing datasets of varying sizes, highlighting the inclusion of chess puzzles. The bottom right section explains the three different prediction targets used for training the models (state-value, action-value, and behavioral cloning), along with the policy learning methods.

This figure shows the overall workflow of the paper. The top part illustrates the data annotation process using Stockfish 16 to extract board states, compute state values, and action values. The bottom-left shows how the dataset is constructed, including training and testing sets with different sizes and compositions. The bottom-right displays the three different policies (state-value, action-value, and behavioral cloning) used in the paper, which are trained on different targets and used for policy prediction. The different predictors are trained on various sizes of datasets, which include datasets based on games from Lichess and chess puzzles from Lichess.

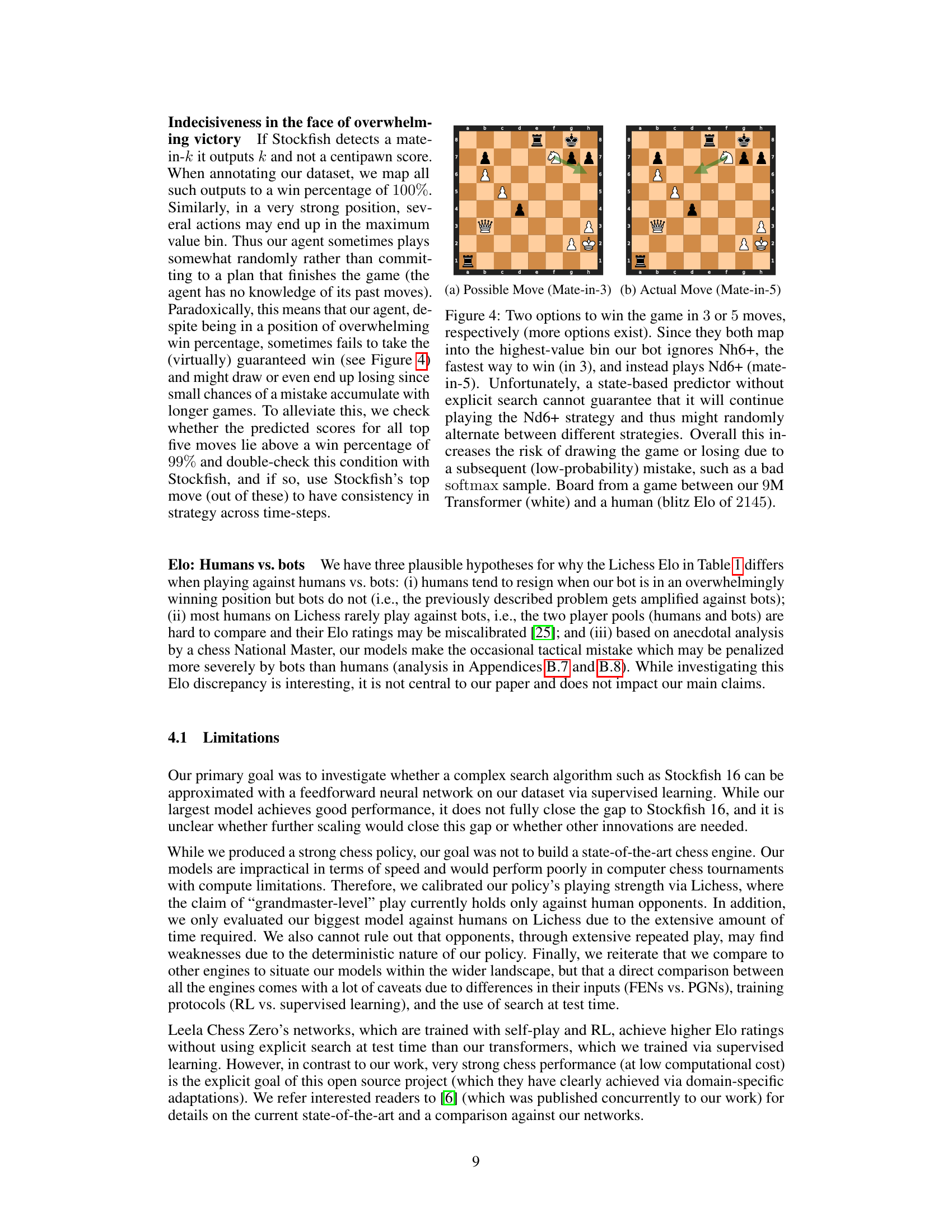

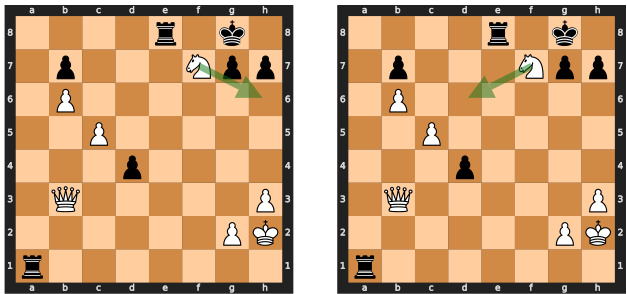

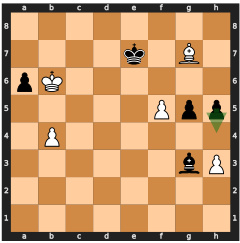

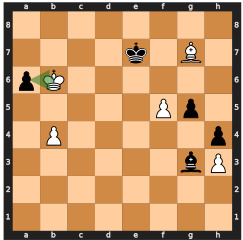

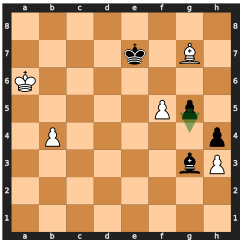

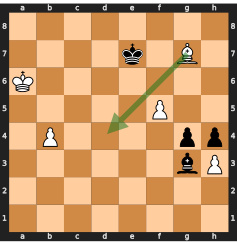

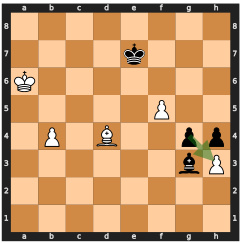

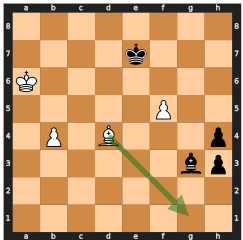

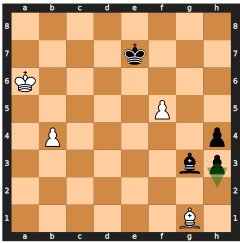

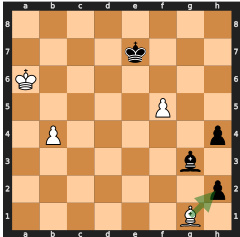

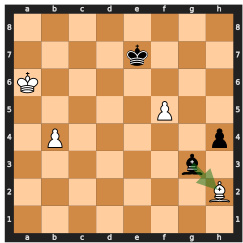

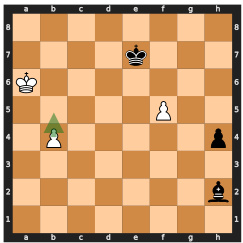

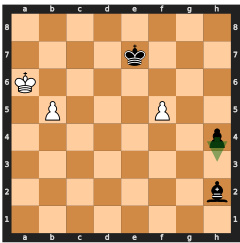

This figure shows two possible move sequences for winning a chess game, both leading to the same predicted win probability. The model, lacking search capabilities, fails to select the optimal (faster) winning sequence and instead chooses a longer one, demonstrating the limitations of searchless approaches to complex planning problems like chess.

This figure illustrates the data annotation process, dataset creation, and policy training methods used in the study. The top section details how board states and their corresponding values and best moves are extracted from Lichess games using Stockfish. The bottom left shows the construction of training and test datasets from various sources with sizes indicated. Finally, the bottom right explains the three training approaches: state-value, action-value, and behavioral cloning.

This figure details the process of data annotation, dataset creation, and policy training for the ChessBench project. The top section shows how board states and actions are annotated using Stockfish, a strong chess engine. The bottom left shows how the resulting data is split into training and testing sets, including a puzzle test set. The bottom right shows the three different types of predictors used (state-value, action-value, and behavioral cloning) and their corresponding policy creation methods.

This figure shows two possible move sequences for winning a chess game, both leading to the highest predicted value. The model chooses the longer sequence (mate in 5 moves), highlighting the limitations of searchless approaches in handling certain situations, where the model may not consistently follow the optimal strategy due to the random nature of its decisions and risk of making suboptimal choices.

This figure details the data annotation, dataset creation, and policy training process used in the study. The top section illustrates how board states and actions are annotated using Stockfish 16, a state-of-the-art chess engine. The bottom left describes the creation of training and testing datasets from Lichess games and puzzles. Finally, the bottom right illustrates the three prediction targets and policy learning methods.

This figure illustrates the process of creating the ChessBench dataset and training three different types of predictors for chess. The top part shows the process of annotating chess game boards with values and best moves using Stockfish. The bottom left part explains how training and testing datasets were created. The bottom right part details the three different policies that were trained for the chess AI and how the output was created.

This figure illustrates the data annotation, dataset creation, and policy training process for the ChessBench dataset. The top part shows how board states and action values are extracted from Lichess games using Stockfish. The bottom left shows how training and testing datasets of varying sizes are created. The bottom right details three different policy training approaches based on state values, action values, and behavioral cloning.

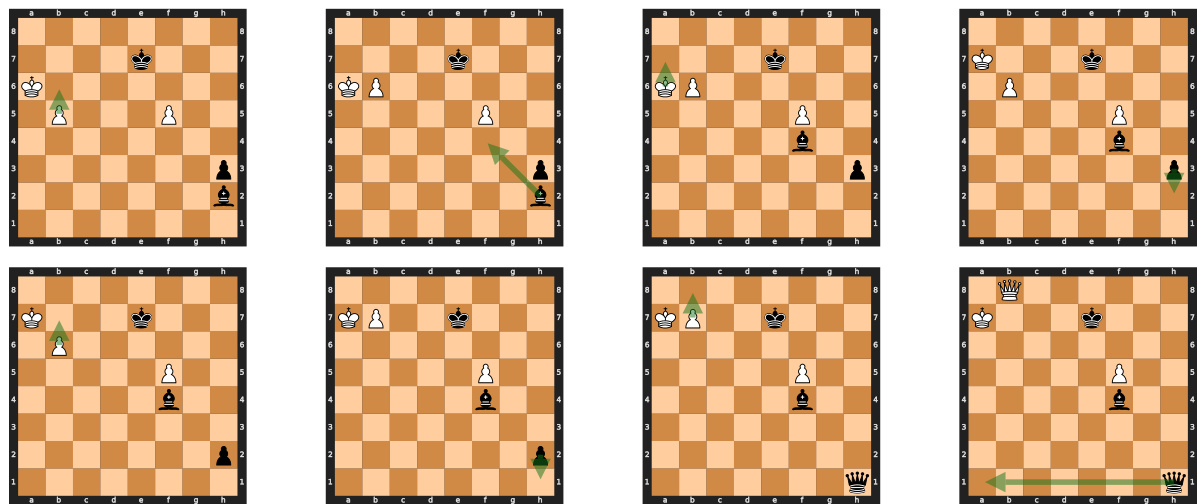

This figure shows several steps of a chess game between a 270M parameter transformer model and a human player. The model, despite material disadvantage, strategically sacrifices pawns to force a checkmate, demonstrating an understanding of long-term strategic planning in chess. The figure highlights the model’s ability to find complex tactical solutions, even if it involves material sacrifice. Each step is accompanied by an analysis from Stockfish, a strong chess engine, confirming the optimality of the moves played by the model.

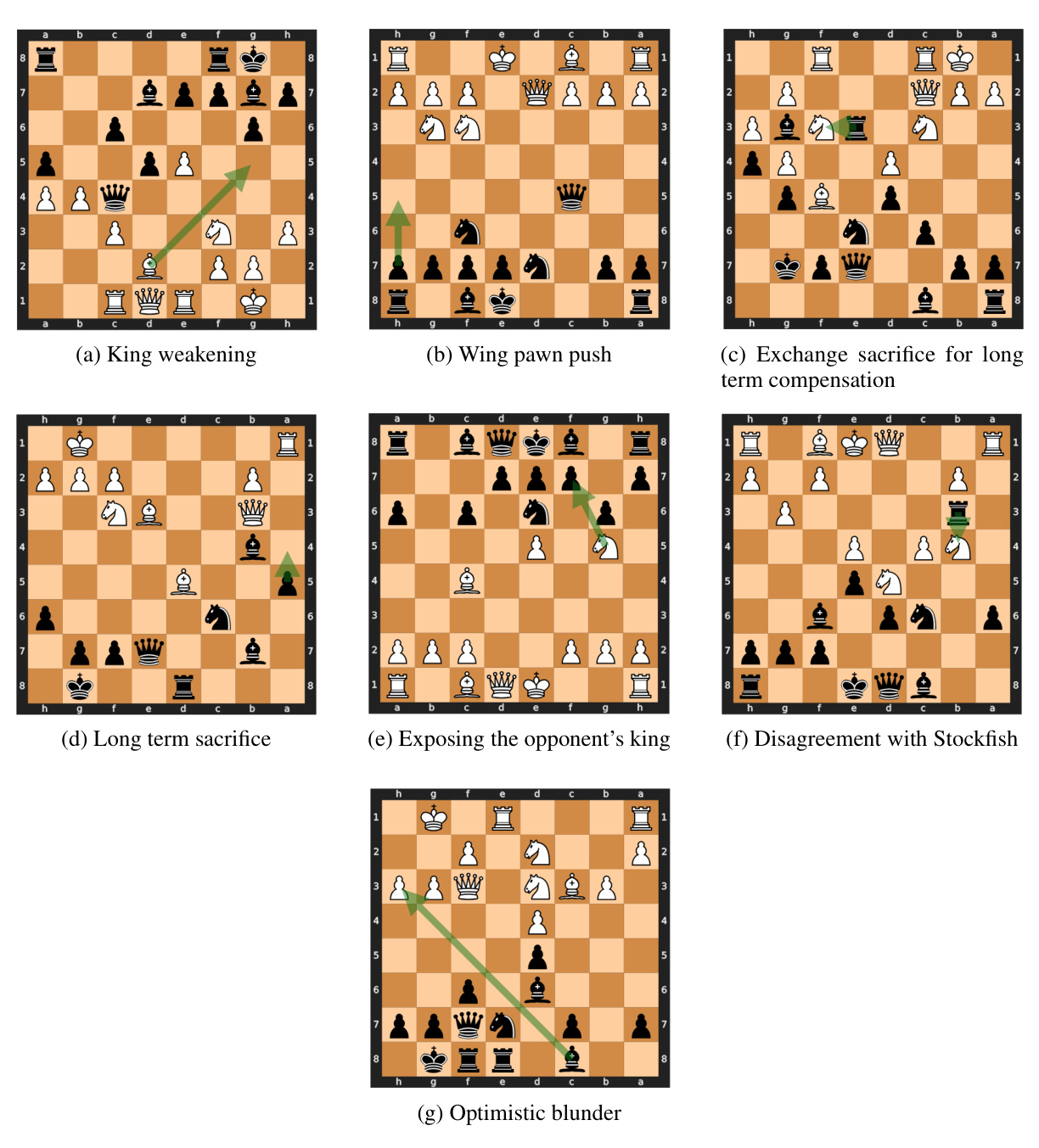

This figure visualizes seven examples of the 270M transformer’s playing style against human opponents in online chess games. Each example showcases a specific tactical or strategic decision made by the AI, highlighting its aggressive, enterprising style. The annotations describe the characteristics of the AI’s play, such as king safety, material sacrifices for long-term advantage, and the pursuit of moves that create difficult choices for human opponents, even if they are not objectively optimal according to traditional chess evaluation metrics. The figure provides visual evidence supporting the qualitative assessment of the AI’s playing style as discussed in the paper.

More on tables

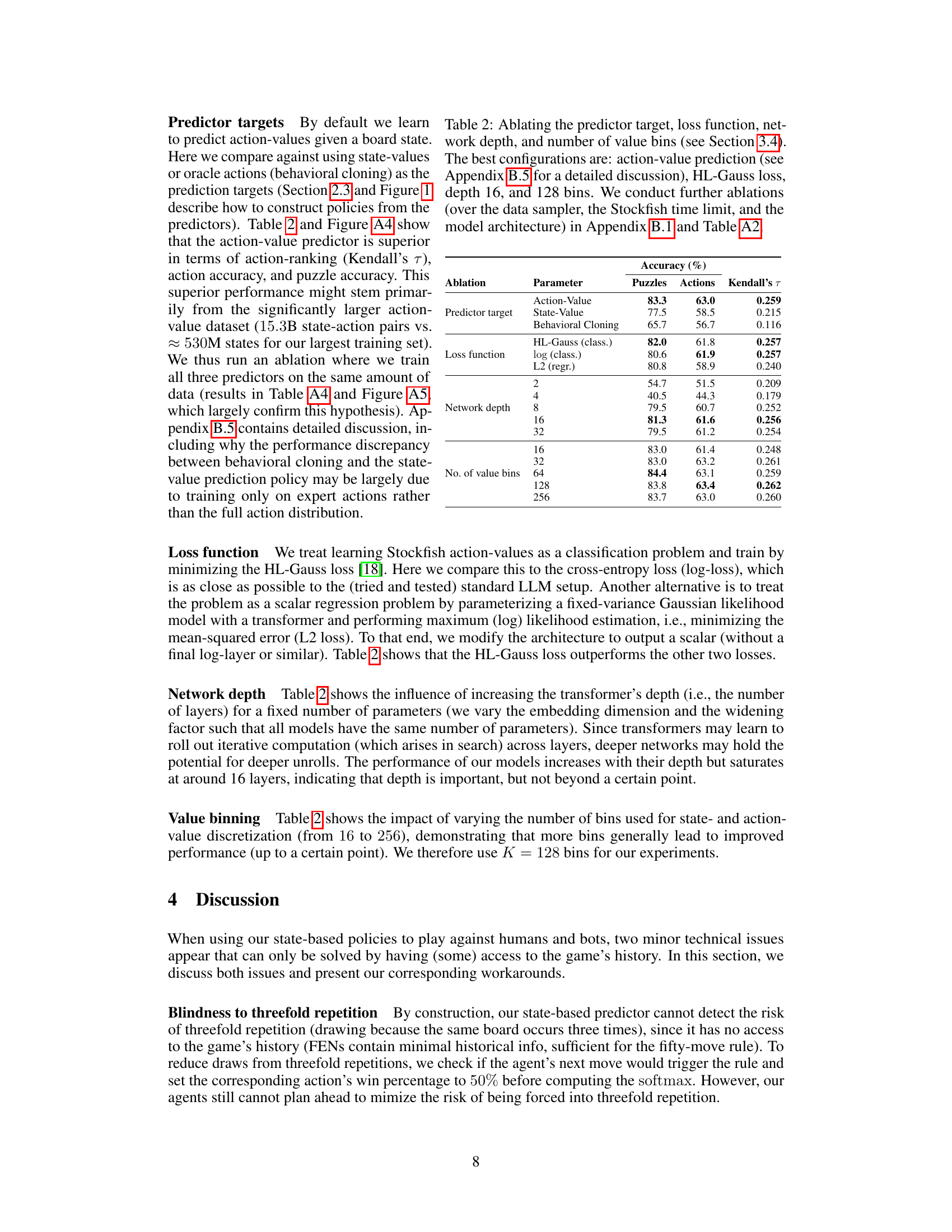

This table presents the ablation study’s results, comparing various model parameters and configurations. It shows the impact of different predictor targets (action-value, state-value, behavioral cloning), loss functions (HL-Gauss, log, L2), network depths (2, 4, 8, 16, 32), and the number of value bins (16, 32, 64, 128, 256) on the model’s performance. The performance metrics used are puzzle accuracy, action accuracy, and Kendall’s τ, indicating the correlation between predicted and actual action rankings. The table helps to identify the optimal hyperparameters for the model.

This table compares the performance of the authors’ action-value models against several other chess engines, including Stockfish, AlphaZero, and Leela Chess Zero. It shows the tournament Elo, Lichess Elo (against bots and humans), and puzzle accuracy for each engine. The table highlights the performance of the authors’ models, which achieve strong results despite not using explicit search at test time. It also points out key differences in training methods and input data (FEN vs. PGN) between the authors’ models and other engines.

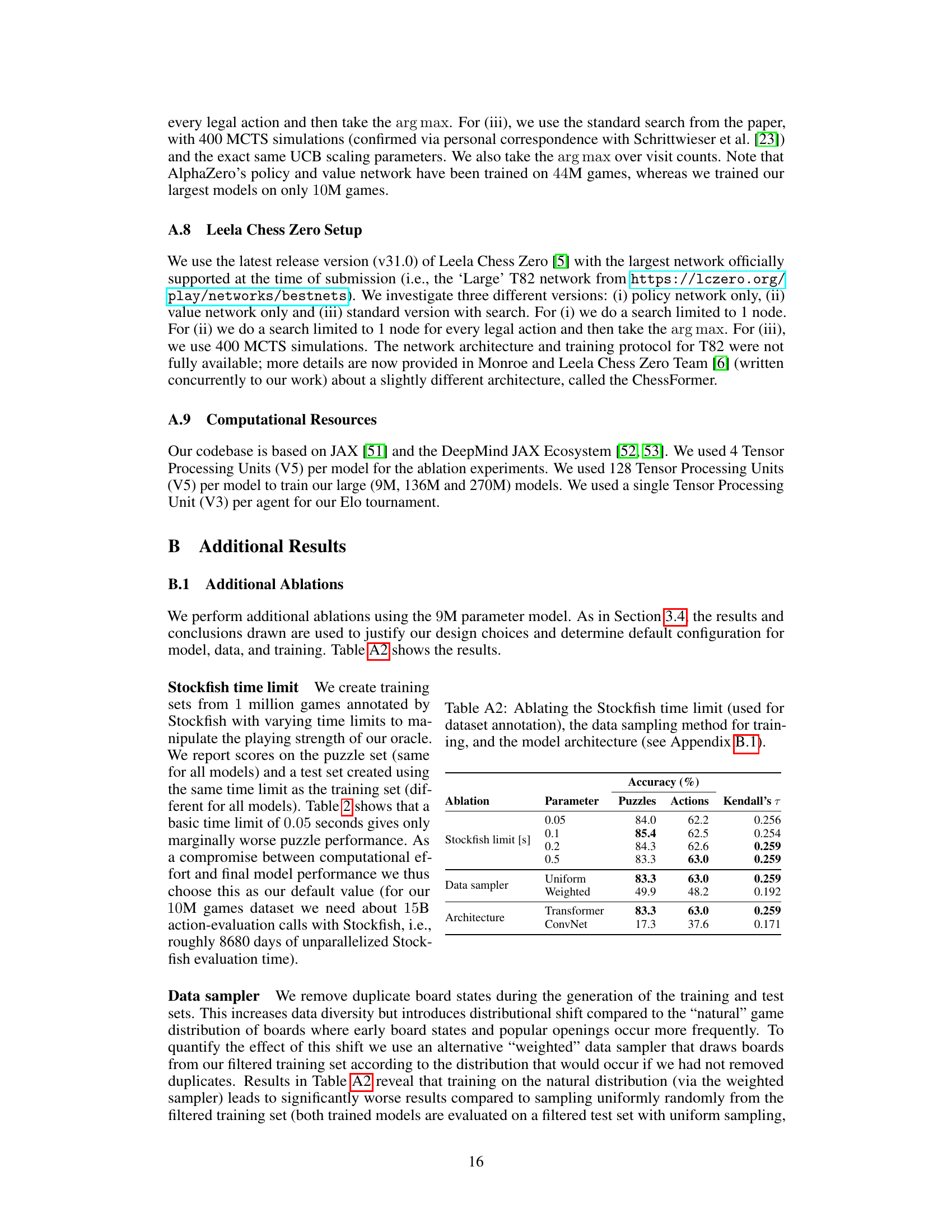

This table presents the results of ablations performed on the 9M parameter model, investigating the impact of Stockfish time limit, data sampling method, and model architecture on the model’s performance. The metrics evaluated are puzzle accuracy, action accuracy, and Kendall’s τ, which measures the rank correlation between the predicted and ground-truth action distributions.

This table compares the performance of the authors’ action-value models against other state-of-the-art chess engines, including Stockfish, AlphaZero, and Leela Chess Zero. It shows the tournament Elo, Lichess Elo (against both humans and bots), and puzzle accuracy for each engine. Key differences in training methods and search usage are highlighted, emphasizing the novelty of the authors’ searchless approach.

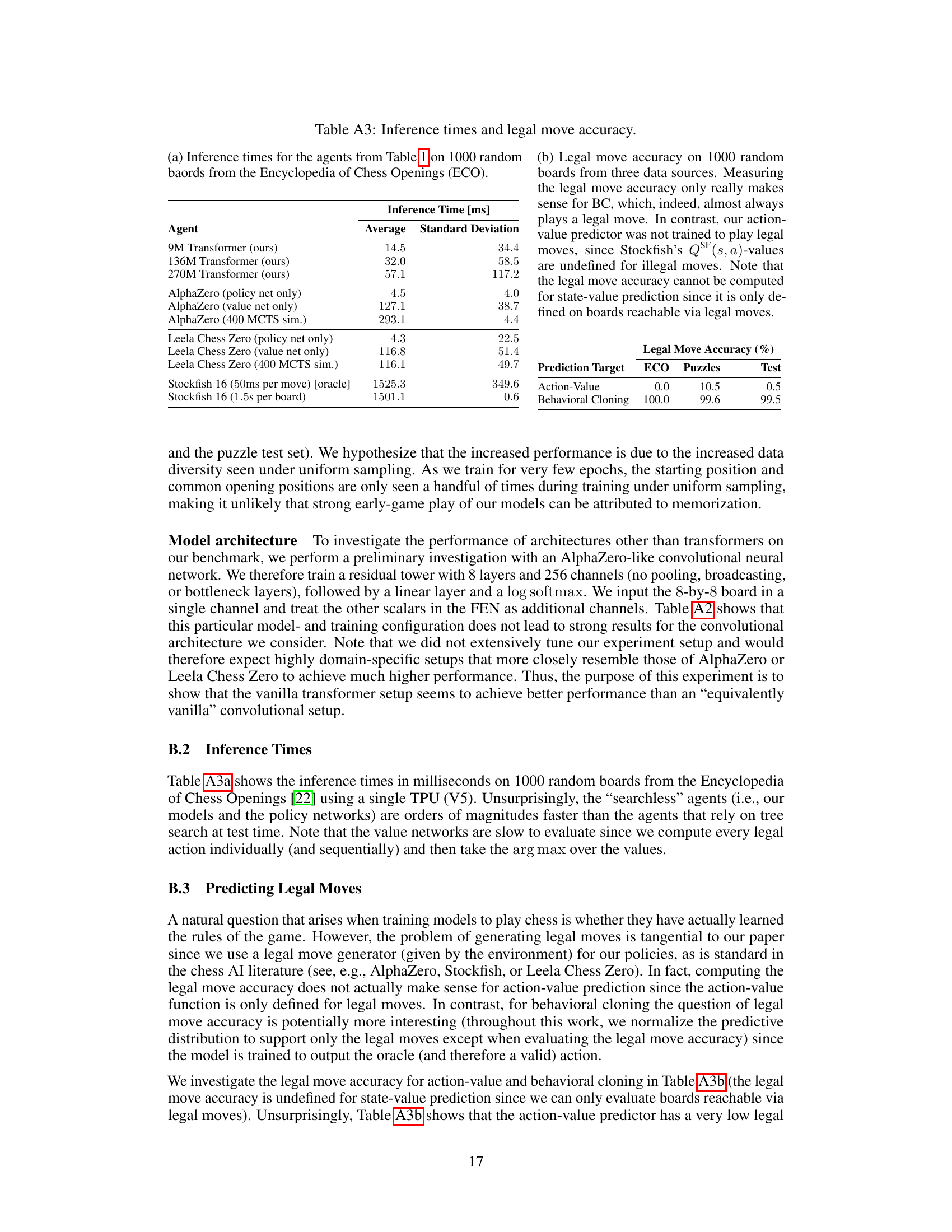

This table presents a comparison of inference times and legal move accuracy for various chess-playing agents. Inference times are measured on 1000 random boards from the Encyclopedia of Chess Openings (ECO). Legal move accuracy is assessed on 1000 random boards from three data sources: ECO, Puzzles, and a Test set. The table highlights the significant difference in inference times between agents that use search and those that don’t, with searchless agents being considerably faster. It also shows that behavioral cloning models are superior in terms of legal move accuracy compared to action-value models.

This table shows the results of a tournament between three different chess playing policies trained using different prediction targets (action-value, state-value, and behavioral cloning). The Elo ratings demonstrate the relative strength of each policy. The results are shown under two conditions: first, using the same number of games to create the training datasets, and second, using the same number of training data points for all three models. The table highlights how the larger dataset size for action-value prediction leads to a significant performance advantage. When the dataset size is equalized across methods, the difference between state-value and action-value prediction disappears.

Full paper#