↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Analyzing neural signals is challenging due to noise and nonlinearities. Current methods like switching linear dynamical systems (SLDS) and decomposed linear dynamical systems (dLDS) struggle with robustness and accurately capturing complex dynamics. SLDS’s discrete state assumption doesn’t suit continuous neural fluctuations, while dLDS’s cost-based inference is noise-sensitive and struggles with multiple fixed points.

The paper introduces probabilistic decomposed linear dynamical systems (p-dLDS) to solve these issues. p-dLDS uses a probabilistic inference method to reduce noise sensitivity, incorporating hierarchical variables for sparsity and smoothness. A time-varying offset term handles systems with multiple fixed points, avoiding degenerate solutions. Evaluations on synthetic and real datasets (including brain-computer interface and clinical neurophysiology data) demonstrate p-dLDS’s superior accuracy and robustness in identifying interpretable and coherent structure where previous methods fail.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with neural time-series data because it introduces a robust method for identifying interpretable patterns in complex, noisy systems. It directly addresses the limitations of existing methods, paving the way for more accurate and reliable analyses across diverse applications, from brain-computer interfaces to clinical neurophysiology. The probabilistic framework and consideration of system nonlinearities improve model generalizability and open avenues for investigating neural dynamics more effectively.

Visual Insights#

This figure shows the graphical models for both the dLDS and the improved p-dLDS models. Panel A depicts the dLDS model, illustrating the relationships between dynamic coefficients, latent states, and observed data. Panel B shows the enhanced p-dLDS model, highlighting the addition of hierarchical variables for more robust probabilistic inference and the inclusion of a time-varying offset term to account for systems with multiple fixed points, thereby improving the model’s capacity to handle complex nonlinear dynamics.

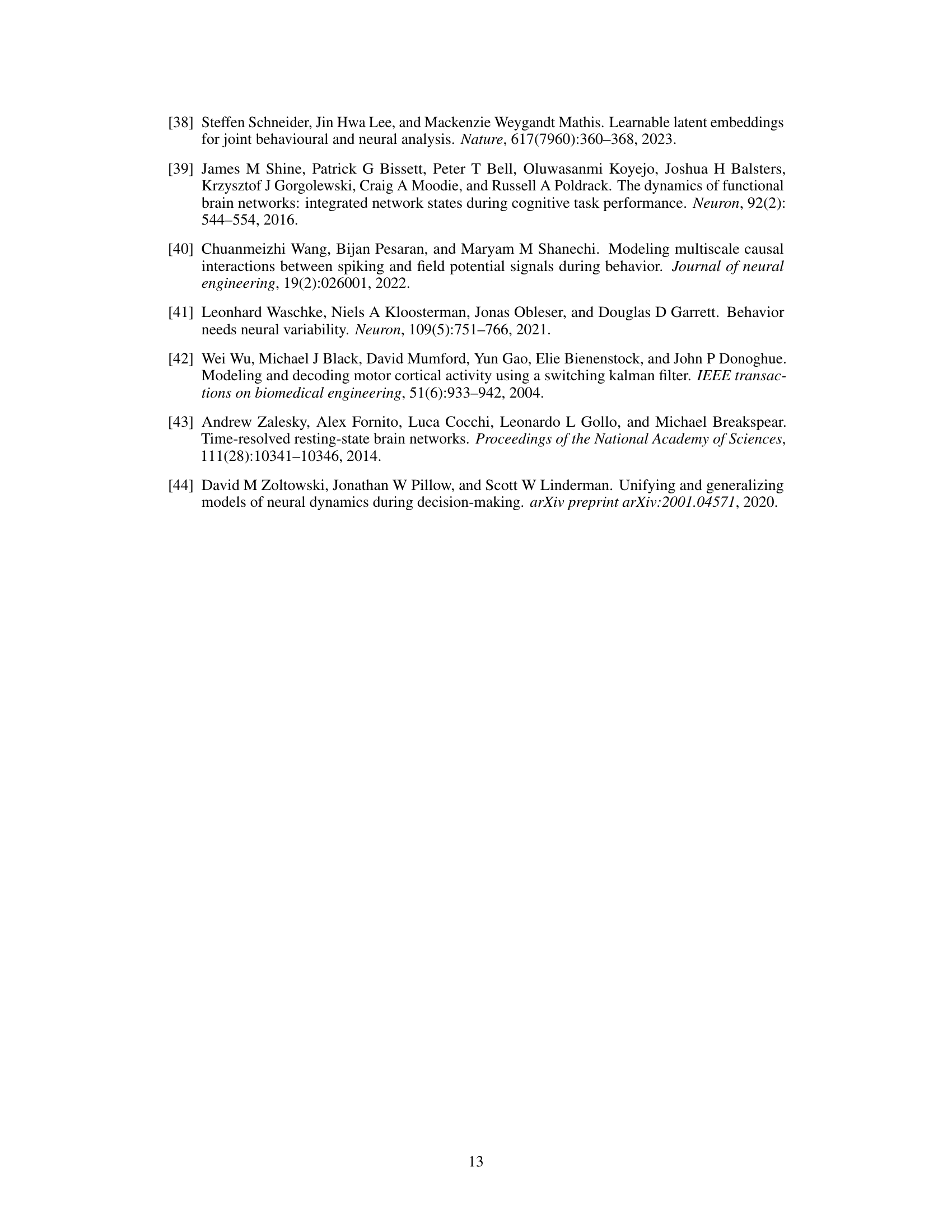

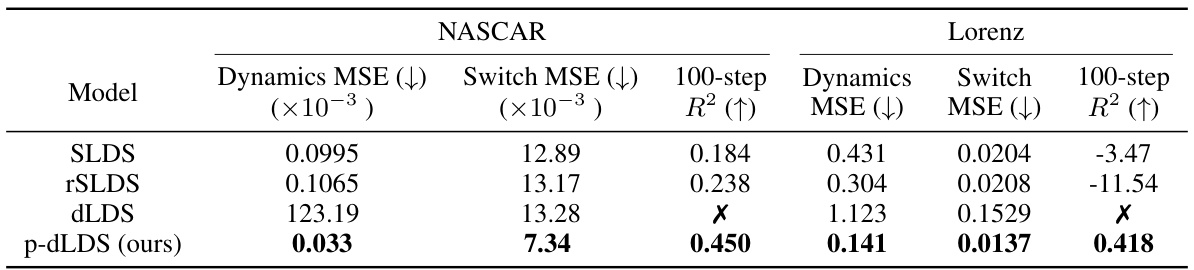

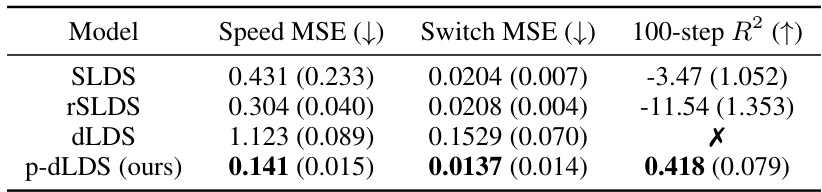

This table presents a comparison of the performance of several different models (SLDS, rSLDS, dLDS, and p-dLDS) on two synthetic datasets: NASCAR and Lorenz. The metrics used to evaluate performance are: Dynamics MSE (mean squared error of the latent dynamics), Switch MSE (mean squared error of switch events), and 100-step R². Lower values for MSE are better, and higher values for R² are better. The ‘X’ indicates that a metric’s value diverged to negative infinity for that model/dataset combination. The table shows that the proposed p-dLDS model outperforms the other models across all metrics and datasets.

In-depth insights#

Robust Latent Inference#

Robust latent inference tackles the challenge of accurately estimating hidden variables (latent factors) from noisy or incomplete data, particularly in dynamic systems. The core difficulty lies in disentangling the true underlying dynamics from observational noise and inherent system nonlinearities. A robust method should not only provide accurate estimates but also be consistent across similar datasets, even under varying noise levels. This robustness is crucial for extracting meaningful insights and ensuring the reliability of scientific conclusions drawn from the analysis. Key strategies for achieving robustness often involve probabilistic modeling, advanced inference techniques (like variational methods), and careful model design. Probabilistic approaches explicitly handle uncertainty, enabling more reliable estimation. Incorporating prior knowledge or structural constraints into the model can further improve robustness. Evaluation of robustness typically involves testing on various datasets with different noise characteristics and comparing performance to alternative methods. Ultimately, a robust latent inference method enhances the reliability and trustworthiness of results, allowing for more confident interpretations and applications of latent variable models in various fields.

p-dLDS model#

The core contribution of this work is the introduction of the probabilistic decomposed linear dynamical system (p-dLDS) model. Unlike prior methods, p-dLDS tackles the challenges of latent variable estimation in the presence of noisy and nonlinear neural data. This is achieved through a probabilistic framework that incorporates time-informed hierarchical variables to mitigate the impact of noise. A key innovation is the integration of a time-varying offset term, addressing limitations of existing models in dealing with systems possessing multiple fixed points. This extension significantly improves robustness and accuracy, particularly in the analysis of complex, nonlinear neural dynamics. The variational expectation maximization (vEM) algorithm employed enables effective inference and learning within this richer probabilistic structure. The p-dLDS model offers a significant improvement over previous approaches by producing more consistent, accurate estimates of latent variables and generating interpretable and coherent latent structure, even when noise and nonlinearities are present. The model demonstrates an improved capacity for multi-step inference, accurately predicting dynamics beyond a single time step, marking a significant leap forward in the field of neural signal analysis.

Time-Varying Offset#

The concept of a “Time-Varying Offset” in the context of probabilistic decomposed linear dynamical systems (p-dLDS) is a crucial enhancement for handling the complexities of real-world dynamical systems. Standard linear dynamical systems often assume a single, stable fixed point, limiting their ability to model systems with multiple operating regimes or non-stationary behaviors. Introducing a time-varying offset term directly addresses this limitation. This offset acts as a flexible mechanism to capture gradual changes or abrupt shifts in the system’s underlying dynamics, effectively modeling nonlinearities and non-stationarities. By incorporating a time-varying offset, the p-dLDS framework becomes more robust and capable of capturing richer, more realistic dynamics, ultimately leading to more accurate latent variable estimation and a deeper understanding of the underlying system. Probabilistic treatment of the time-varying offset further enhances the robustness of p-dLDS, allowing for better generalization and reduced sensitivity to noise. This combined approach, then, leads to interpretable results, particularly in complex neural data where previous methods often fall short.

Synthetic Data Tests#

Utilizing synthetic datasets for testing is crucial in evaluating the robustness and generalizability of the probabilistic decomposed linear dynamical systems (p-dLDS) model. Synthetic data allows for controlled experiments, manipulating noise levels and system nonlinearities in a way not possible with real-world data. This approach enables a thorough assessment of the model’s performance under various conditions, identifying strengths and weaknesses not readily apparent in real-world applications where complexities can obscure the underlying dynamics. The choice of synthetic datasets is critical, requiring careful consideration of the underlying models used to generate the data and how well these capture the dynamics and structure present in the target neural signals. Comprehensive testing involves datasets designed to highlight potential model limitations, particularly those related to noise sensitivity and issues with convergence. The results from synthetic data testing provide valuable insights that inform the design and improve the model’s functionality, ensuring its reliability and accuracy in the analysis of real-world neural signals.

Future Work#

The paper’s lack of a dedicated ‘Future Work’ section presents an opportunity for deeper exploration. Extending the probabilistic framework to encompass more complex emission distributions, such as Poisson processes for neural spiking data, would enhance the model’s applicability to diverse neural datasets. Investigating more sophisticated offset models could unlock improved modeling of systems with multiple, evolving fixed points. Analyzing the influence of varying window sizes on offset estimation and the model’s overall performance warrants further research. Finally, a crucial area for development is developing methods for automatically determining optimal window sizes, thereby enhancing the model’s adaptability and practicality in real-world scenarios. Investigating the potential for improved multi-step inference accuracy through alternative probabilistic approaches would also greatly benefit the model’s capabilities. These explorations would make the probabilistic decomposed linear dynamical systems (p-dLDS) an even more powerful and versatile tool for uncovering latent dynamics in complex neural systems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

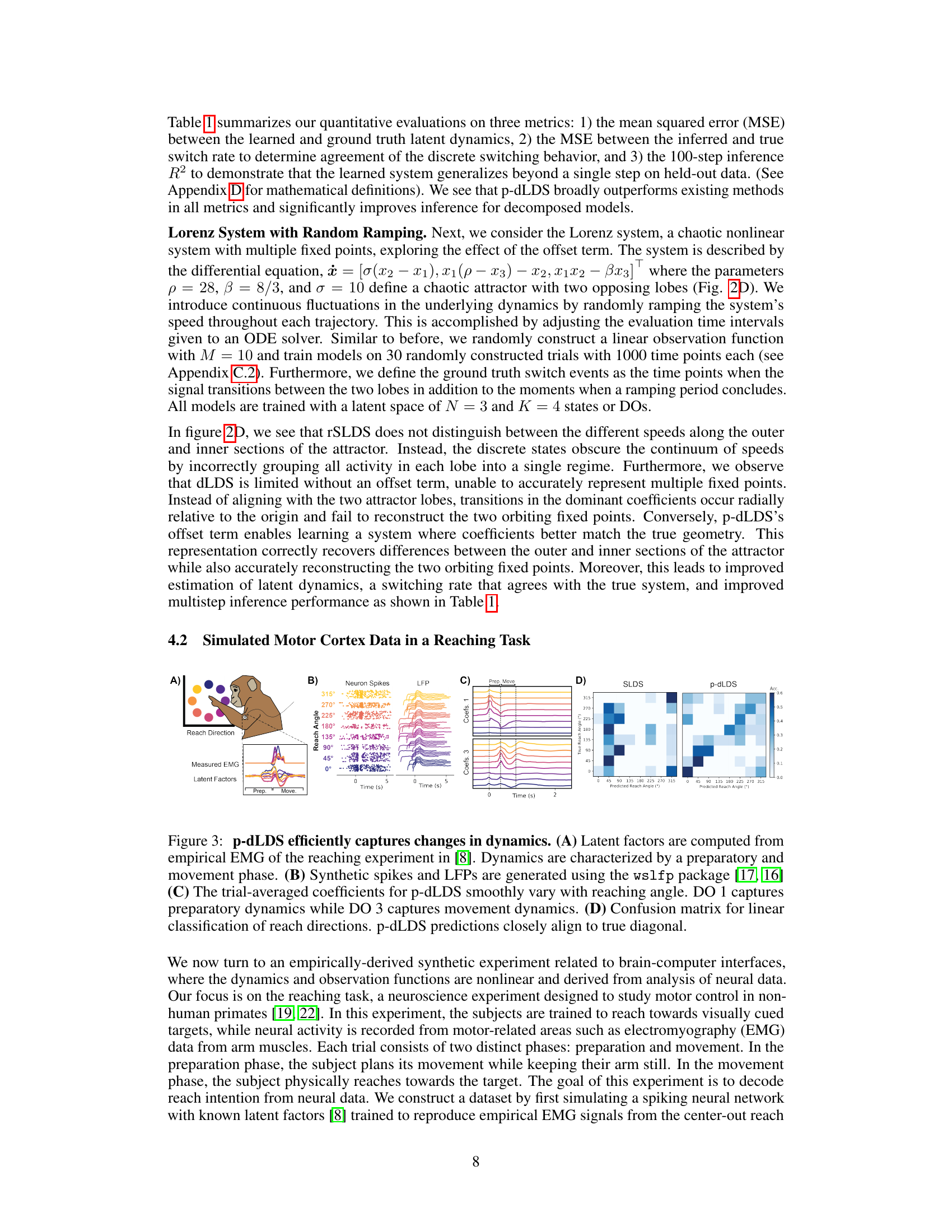

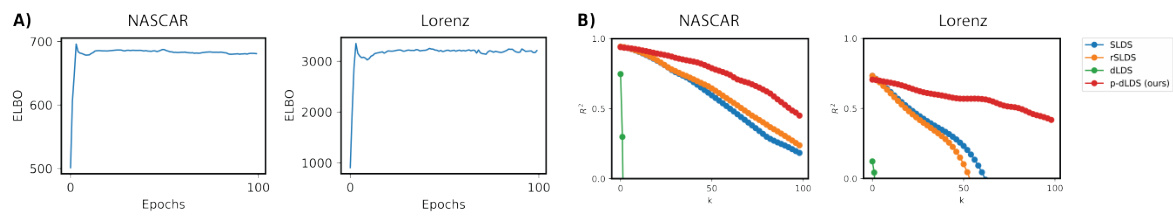

This figure demonstrates the performance of the proposed p-dLDS model compared to other models (SLDS, rSLDS, dLDS) on two synthetic datasets: NASCAR and Lorenz. The NASCAR dataset involves a track with segments of varying speeds. The Lorenz dataset is a chaotic system with two opposing lobes and varying speeds. The figure shows that p-dLDS accurately infers the latent states and dynamics in both scenarios, especially capturing the varying speeds and multiple fixed points in the Lorenz system, showcasing its robustness to noise and nonlinearities.

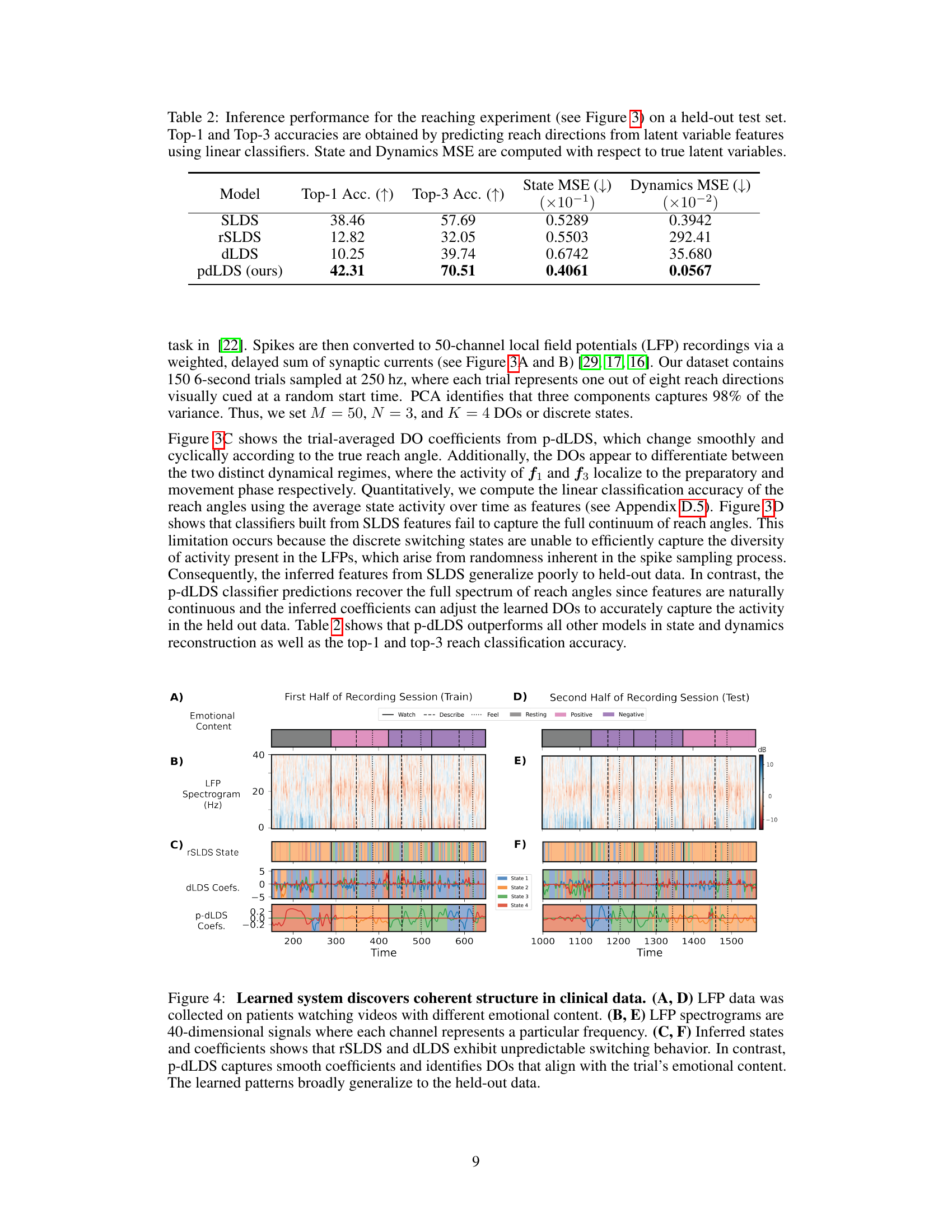

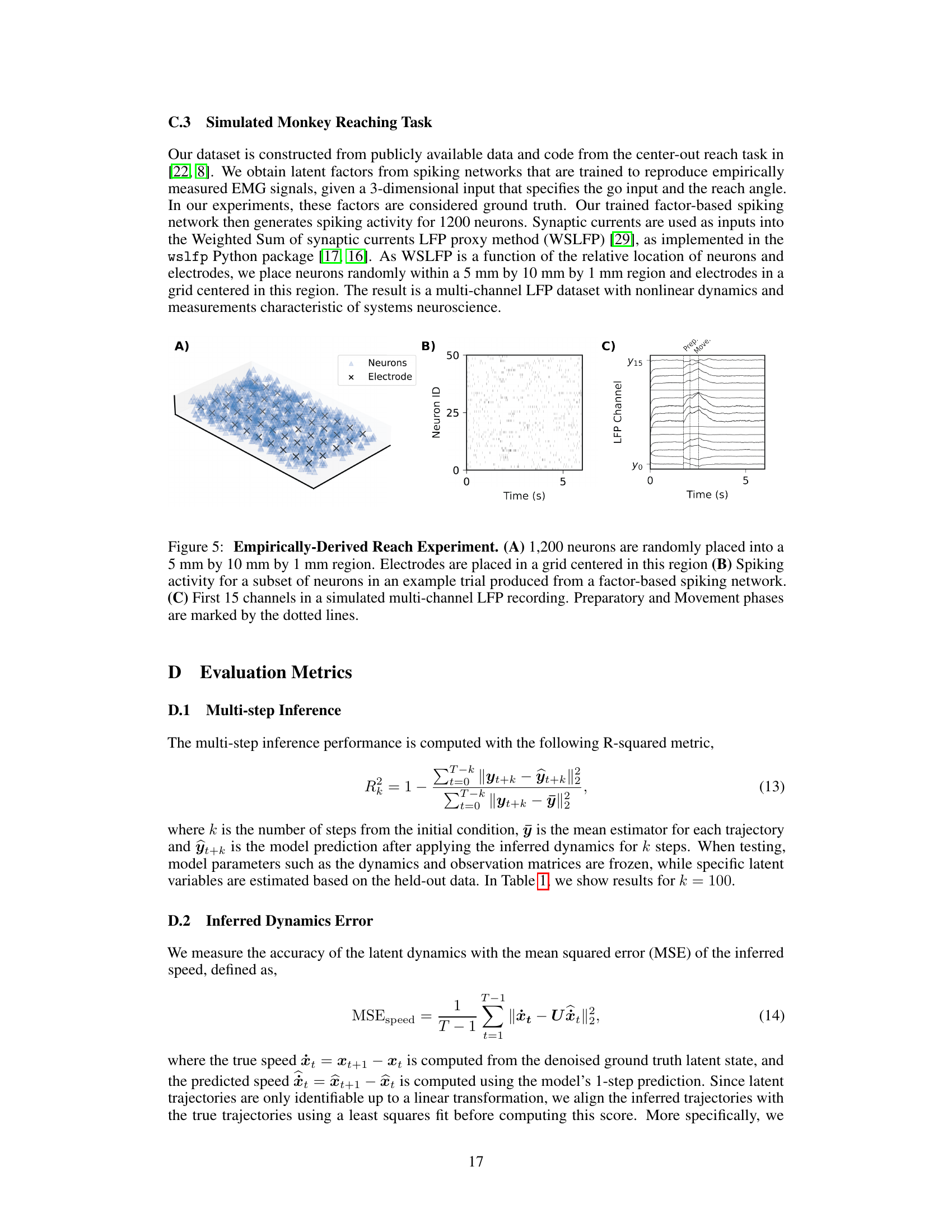

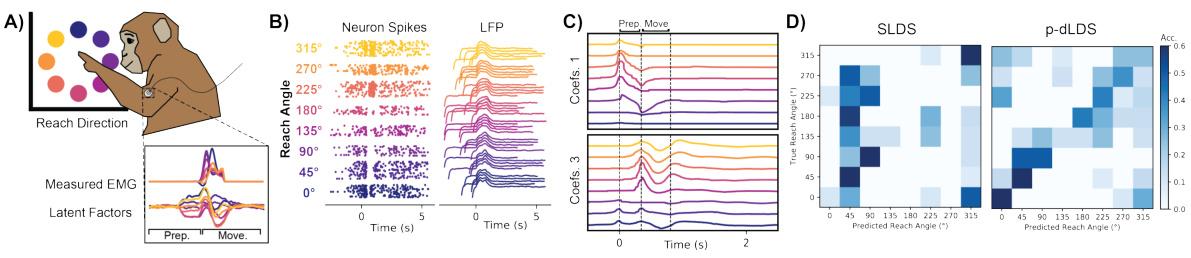

This figure shows how the probabilistic decomposed linear dynamical systems (p-dLDS) model effectively captures changes in neural dynamics during a reaching task. Panel A illustrates the experimental setup, with a monkey reaching towards different targets. Panel B displays the simulated neural activity (spikes and LFPs). Panel C highlights the smooth variation of p-dLDS coefficients with reaching angle, indicating the model’s ability to track dynamic changes. Finally, Panel D shows the high accuracy of reach angle prediction using p-dLDS, as demonstrated by the confusion matrix.

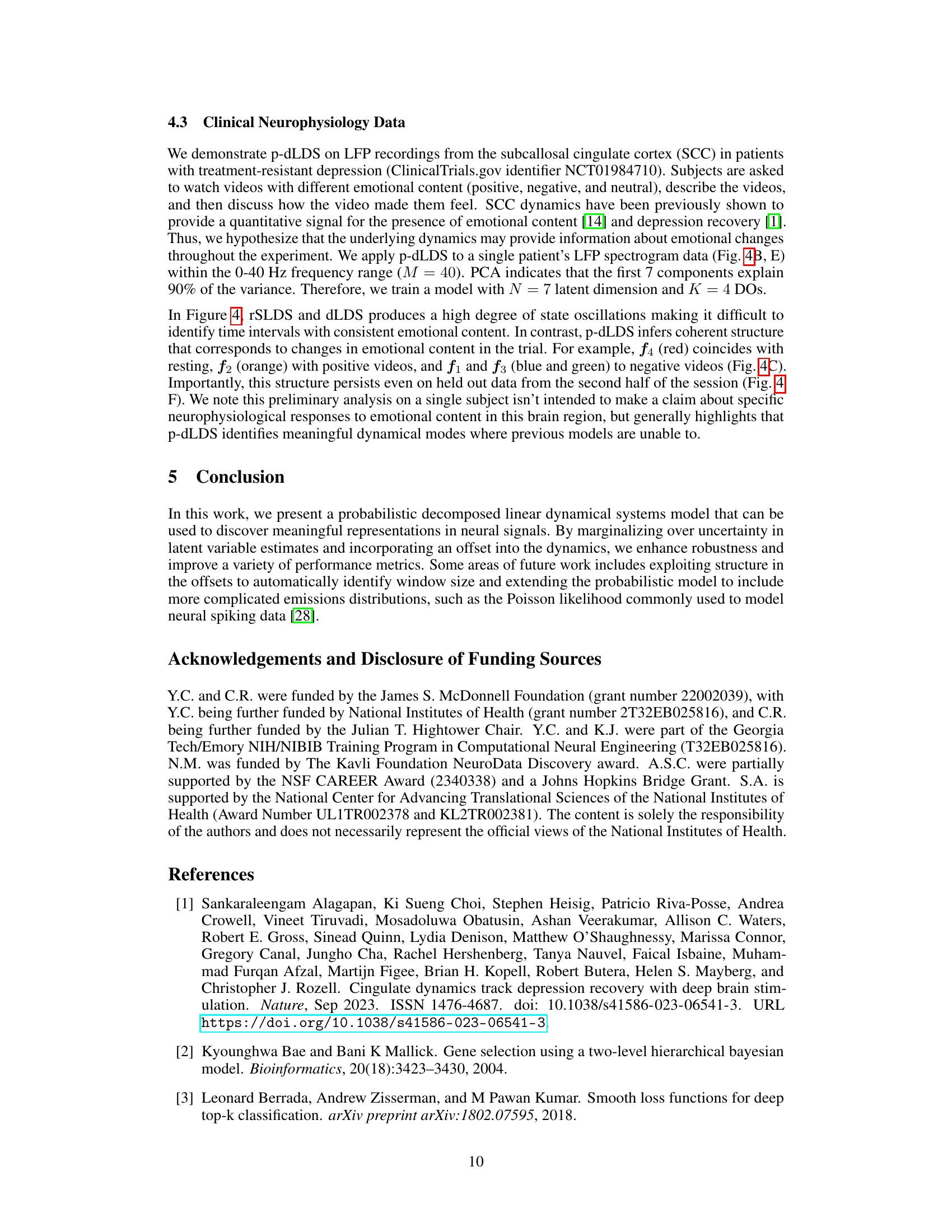

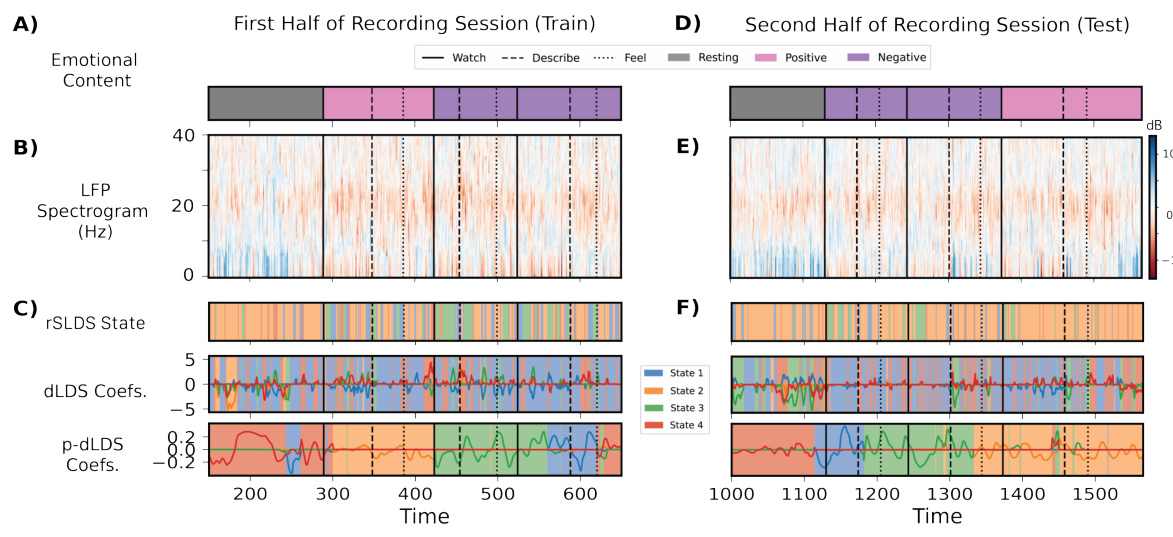

This figure demonstrates the application of the proposed probabilistic decomposed linear dynamical system (p-dLDS) model to clinical neurophysiology data. The data consists of local field potential (LFP) spectrograms from the subcallosal cingulate cortex (SCC) of patients watching videos with varying emotional content. The figure compares the performance of p-dLDS to that of rSLDS and dLDS in identifying coherent structure within the data. p-dLDS shows smooth, interpretable coefficient changes that align with the emotional content of the videos, unlike the other two models which show erratic switching behavior. This demonstrates the improved robustness and interpretability of the p-dLDS model.

This figure shows the setup and data used for the simulated monkey reaching task experiment. Panel A displays the spatial arrangement of neurons and electrodes in a 3D volume. Panel B presents the spiking activity of a subset of neurons over time, illustrating the preparatory and movement phases of a trial. Panel C shows the resulting simulated LFP (Local Field Potential) data from a subset of channels during a trial, again showing the distinct preparatory and movement phases.

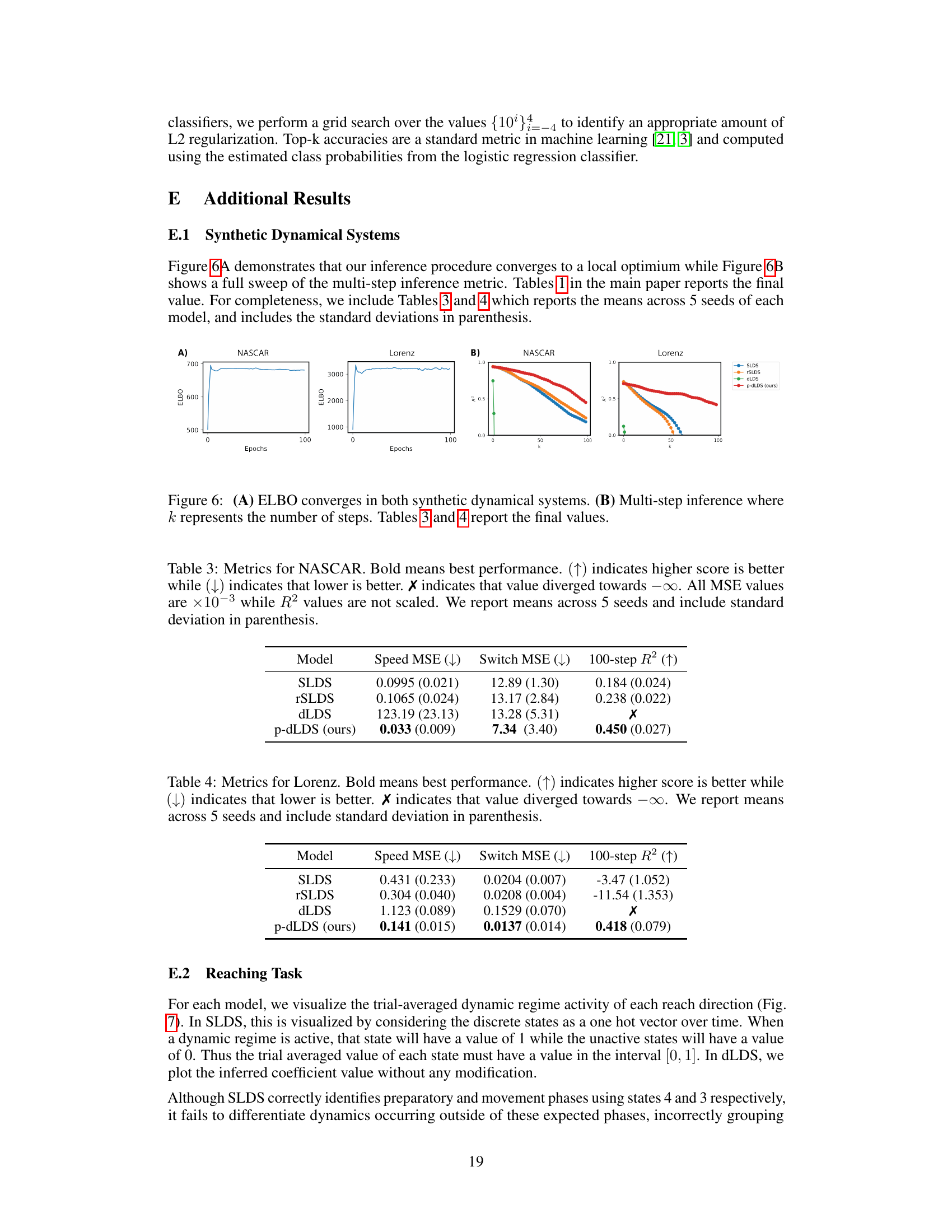

Figure 6 shows the convergence of the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO) during training for both the NASCAR and Lorenz datasets in (A), indicating successful model training. Panel (B) displays the multi-step inference performance (R-squared) for different values of k (number of prediction steps). The results illustrate the superior predictive capability of the proposed p-dLDS model compared to existing methods (SLDS, rSLDS, dLDS). The plots suggest that p-dLDS maintains better predictive accuracy over longer time horizons.

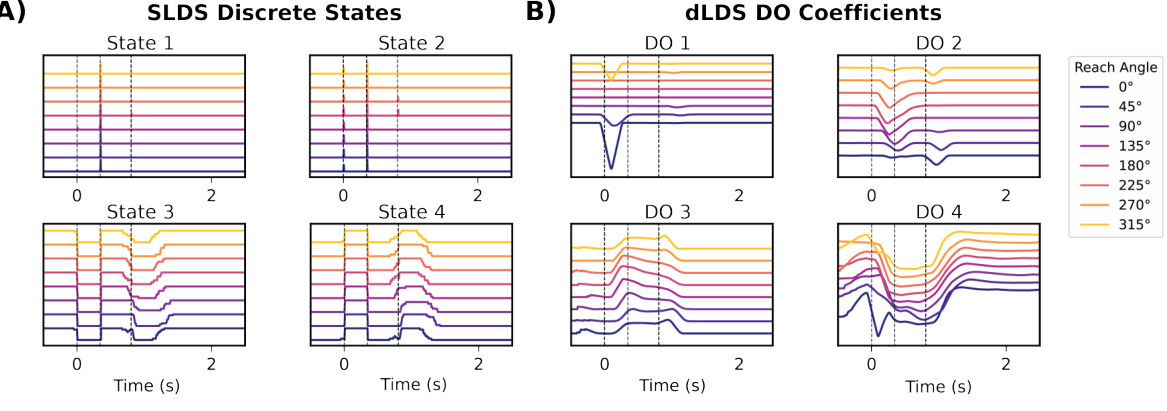

This figure compares the trial-averaged activity of SLDS discrete states and dLDS dynamic operator (DO) coefficients for eight different reach angles (0°, 45°, 90°, 135°, 180°, 225°, 270°, 315°). The preparatory and movement phases are indicated by dashed lines. It illustrates how the different models capture the dynamics of a reaching task. SLDS shows discrete state transitions, while dLDS shows continuous changes in DO coefficients.

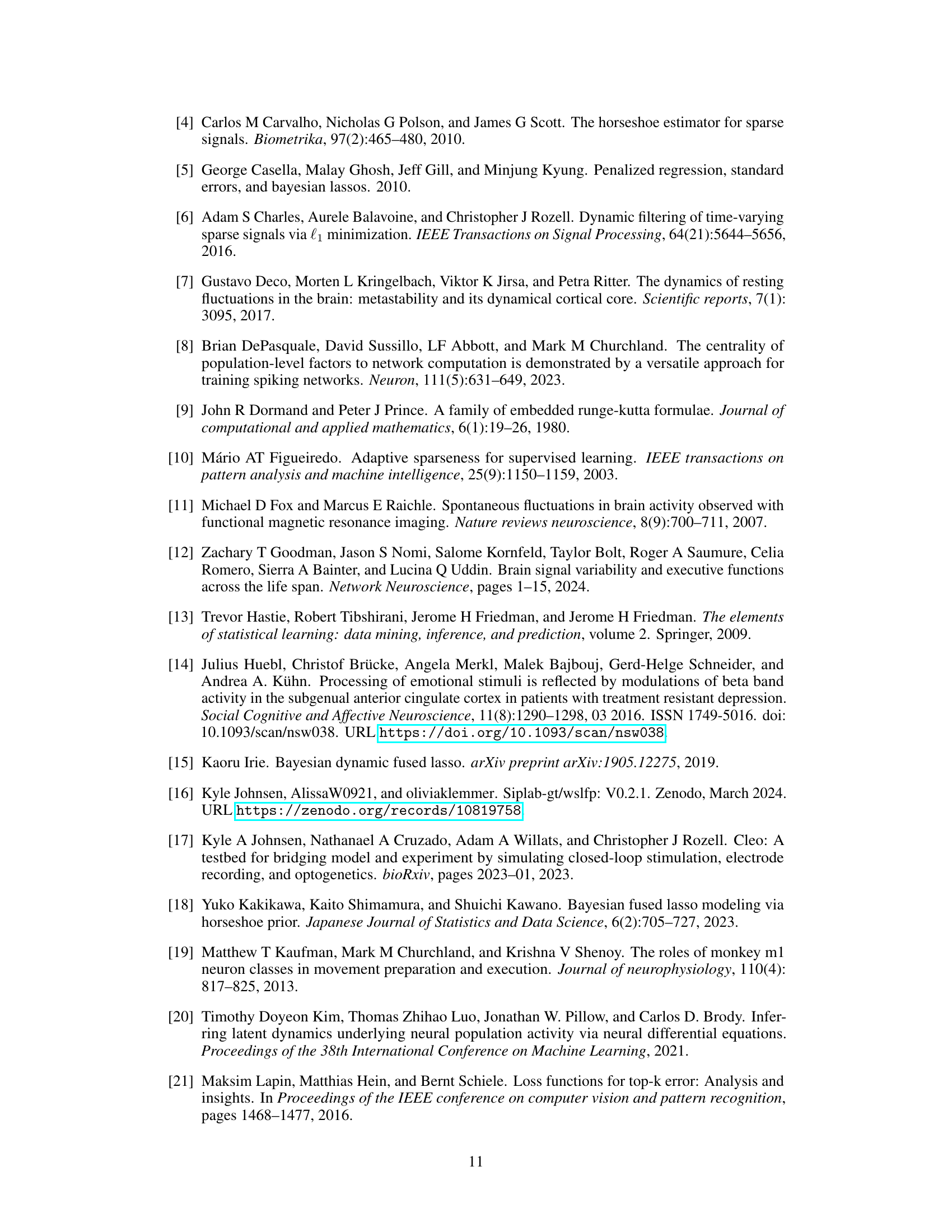

More on tables

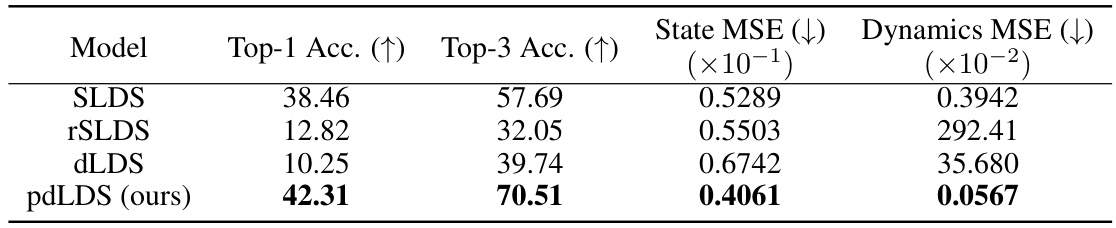

This table presents the performance comparison of different models (SLDS, rSLDS, dLDS, and p-dLDS) on a held-out test set for a reaching experiment. The metrics used are Top-1 accuracy, Top-3 accuracy, State MSE, and Dynamics MSE. Higher Top-1 and Top-3 accuracy indicate better performance. Lower State MSE and Dynamics MSE indicate better performance in terms of accurately representing the latent state and dynamics of the system. The table shows that the proposed p-dLDS model outperforms the other models across all metrics.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of four different models (SLDS, rSLDS, dLDS, and p-dLDS) on two synthetic datasets (NASCAR and Lorenz). The metrics used to evaluate performance are dynamics MSE (lower is better), switch MSE (lower is better), and 100-step R² (higher is better). The table shows that the proposed p-dLDS model outperforms the other models in most metrics across both datasets. The switch MSE metric specifically highlights the improved robustness of p-dLDS in accurately capturing the switching behaviour in dynamic systems, showing significantly lower error compared to other models.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different models (SLDS, rSLDS, dLDS, and p-dLDS) on two synthetic datasets (NASCAR and Lorenz). The metrics used to evaluate performance are: MSE of dynamics, MSE of switch events (lower is better, only for SLDS, rSLDS), and R-squared for 100-step prediction (higher is better). The table highlights the superior performance of the proposed p-dLDS model, particularly in terms of robustness and accuracy in predicting latent dynamics over longer time horizons.

This table presents the quantitative results of applying different models (SLDS, rSLDS, dLDS, and p-dLDS) to a simulated monkey reaching task dataset. The performance of each model is evaluated using four metrics: Top-1 accuracy (the percentage of times the model correctly predicted the reach direction), Top-3 accuracy (the percentage of times the model’s prediction is among the top three most likely directions), State MSE (mean squared error between the inferred and true latent states), and Dynamics MSE (mean squared error between the inferred and true latent dynamics). Lower MSE values indicate better performance.

Full paper#