↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Programming by Example (PBE), generating code from input-output examples, is a significant challenge in AI. Large Language Models (LLMs), while initially ineffective at PBE, show substantial promise. Existing PBE methods often rely on restricted domain-specific languages, limiting their applicability and power.

This research investigates LLMs’ potential for solving PBE using general-purpose languages like Python. The authors demonstrate that fine-tuning pre-trained LLMs on PBE datasets dramatically boosts their performance, surpassing both traditional symbolic methods and advanced closed-source models. They explore different domains, revealing that success hinges more on the posterior description length than program size, and introduce an adaptation algorithm to bridge the gap between in-distribution and out-of-distribution generalization, improving the robustness of the system.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it bridges the gap between LLMs and the challenging field of program synthesis, particularly Programming by Example (PBE). It demonstrates that while LLMs are not inherently good at PBE, they can be dramatically improved through fine-tuning. This opens exciting new avenues for making PBE more accessible and powerful, potentially impacting millions of users of spreadsheet software and beyond. The methodology used and findings on the factors impacting success/failure of LLMs are also important contributions.

Visual Insights#

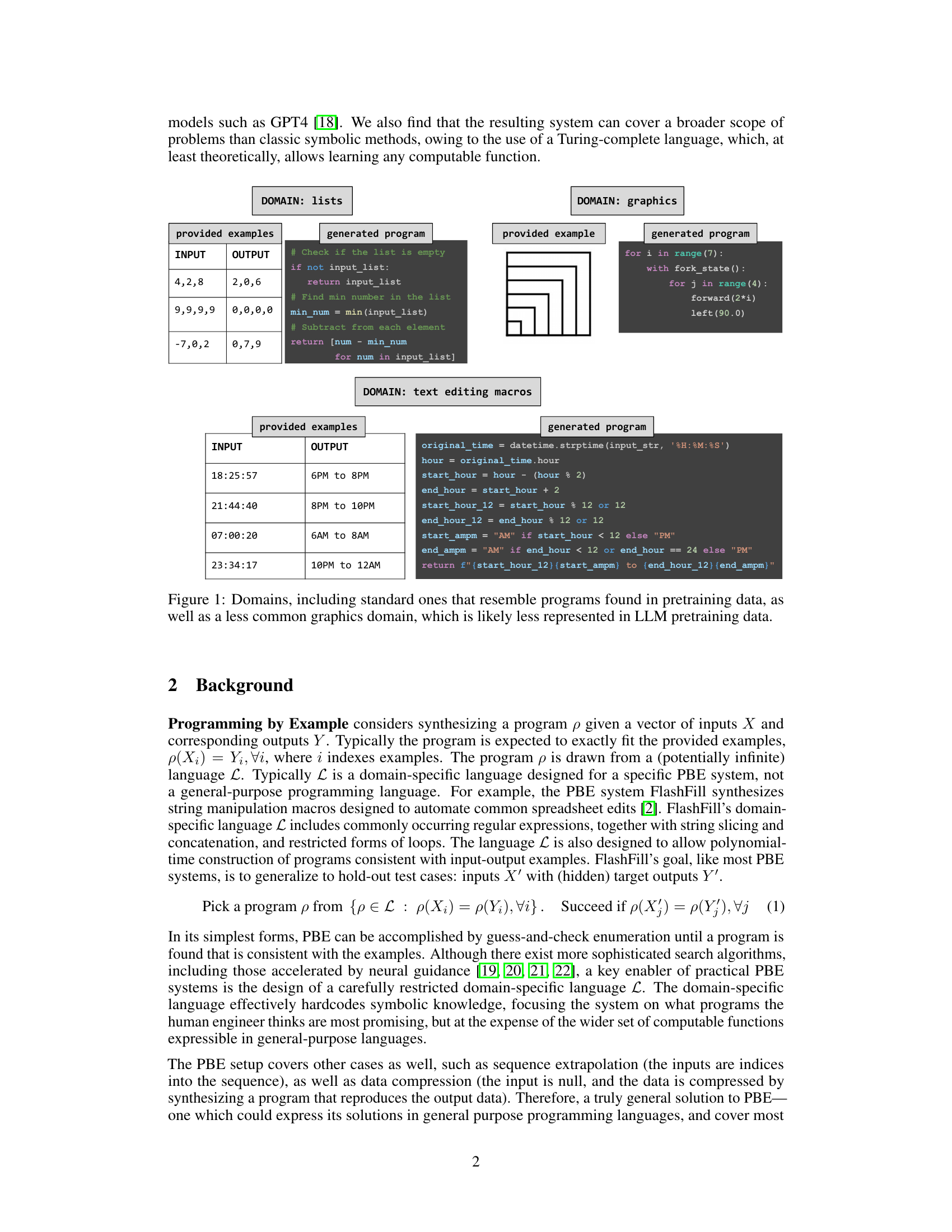

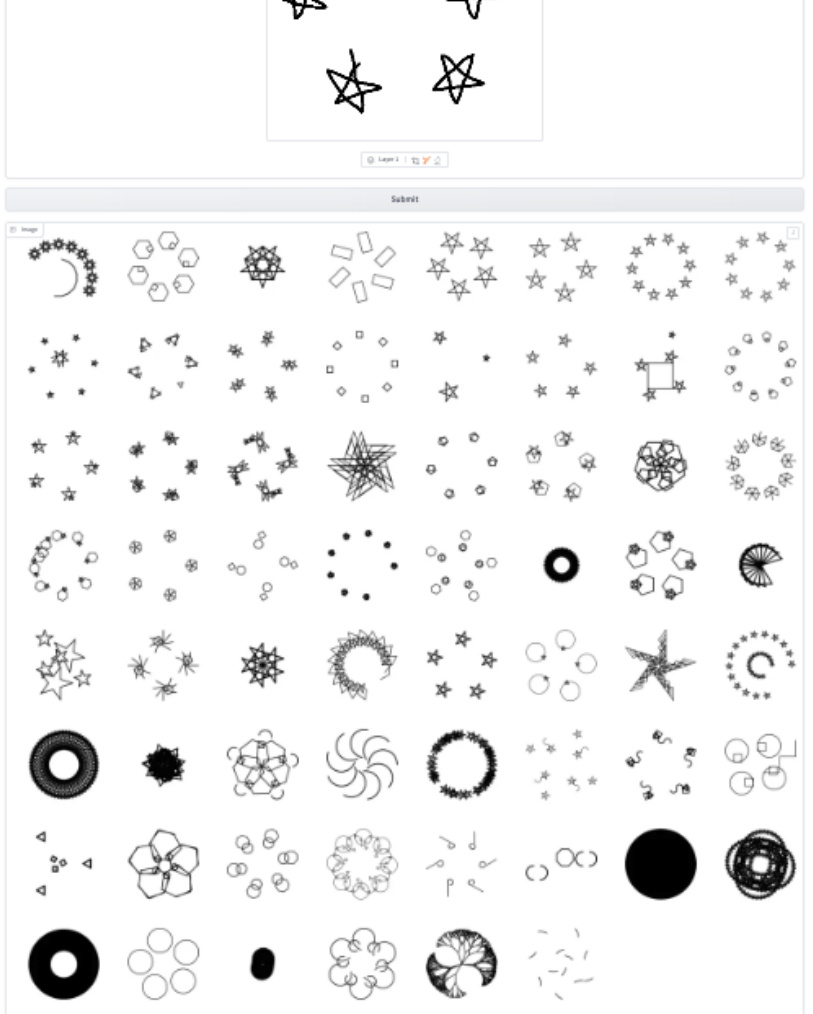

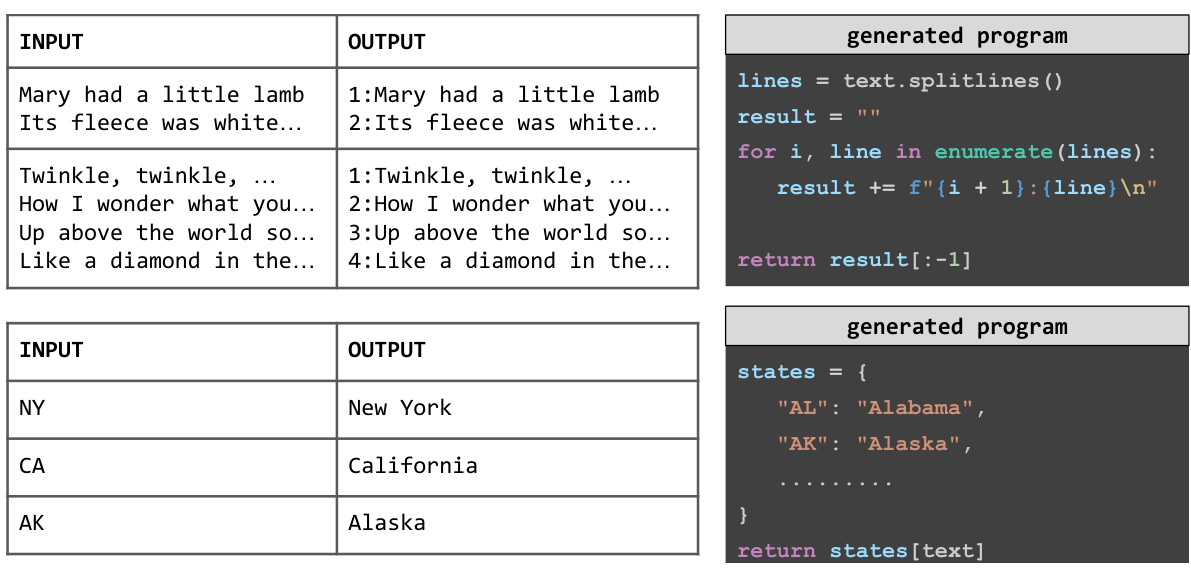

This figure shows three different domains used to evaluate the performance of LLMs in programming-by-example (PBE) tasks. These domains represent varying levels of complexity and typicality in LLM training data. * Lists: This domain involves manipulating lists of numbers, which is relatively common in programming datasets used for pre-training LLMs. * Graphics: This domain is less common in LLM training data and involves generating graphics programs. This helps evaluate the model’s ability to generalize beyond typical programming tasks. * Text Editing Macros: This domain is somewhere in between in terms of frequency and focuses on string manipulations that is prevalent in spreadsheet software. This task evaluates inductive reasoning in transforming input strings into output strings. Each domain is visually illustrated with example inputs, outputs, and the automatically generated program (in Python) by the fine-tuned language model.

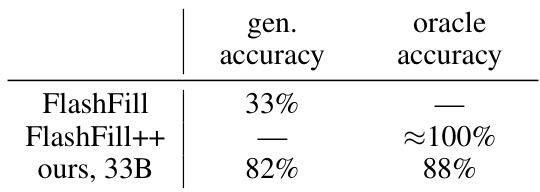

This table compares the generalization accuracy and oracle accuracy of three different text editing program synthesis systems: FlashFill, FlashFill++, and the proposed LLM-based system. Generalization accuracy measures the percentage of problems for which the generated program produces correct outputs on unseen test cases. Oracle accuracy measures the percentage of problems for which at least one correct program was generated, even if other incorrect programs were also generated. The results show that the LLM-based system significantly outperforms FlashFill in terms of generalization accuracy and achieves comparable performance to FlashFill++ in terms of oracle accuracy.

In-depth insights#

LLM-PBE Synergy#

The concept of ‘LLM-PBE Synergy’ explores the powerful combination of Large Language Models (LLMs) and Programming by Example (PBE). LLMs, with their code generation capabilities, offer a new approach to PBE’s challenge of automatically synthesizing programs from input-output examples. This synergy overcomes limitations of traditional PBE methods which often rely on restricted domain-specific languages, hindering generalization. LLMs, by contrast, can operate in Turing-complete languages like Python, dramatically increasing the scope of solvable problems. However, pretrained LLMs are not directly effective at PBE. Fine-tuning is crucial for high performance, although it can lead to a deficit in out-of-distribution generalization. Adaptation techniques that leverage unlabeled data from the target domain are key to address this challenge, moving towards a more robust and versatile PBE system. The combination thus enhances PBE’s flexibility while also revealing the limitations of LLMs in pure inductive reasoning, highlighting areas for future research.

Fine-tuning Effects#

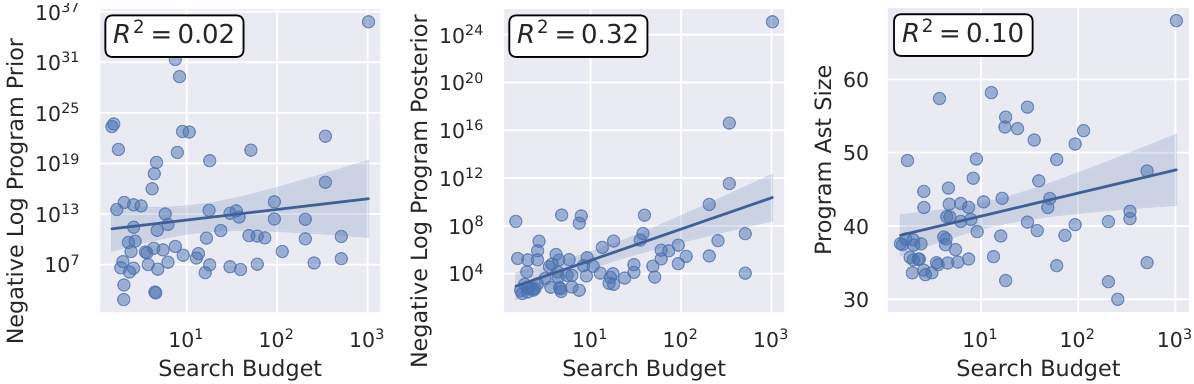

Fine-tuning’s impact on large language models (LLMs) for programming-by-example (PBE) tasks reveals a complex interplay of factors. While pretrained LLMs show limited PBE capabilities, fine-tuning significantly boosts performance, especially when the test problems align with the training data distribution. This highlights the importance of high-quality, in-distribution training data for effective LLM fine-tuning. However, a critical limitation is the models’ struggle with out-of-distribution generalization, suggesting that fine-tuning alone doesn’t fully solve the inductive reasoning challenges inherent in PBE. Adaptation techniques, using small unlabeled datasets of problems to further adjust the LLM, show promise in mitigating this shortcoming but don’t fully eliminate the issue. Analyzing the factors driving success or failure in fine-tuned models reveals that posterior description length, not program size, is the strongest predictor of performance, indicating that fine-tuning helps the model leverage input/output examples effectively for program generation, rather than just relying on simple pattern matching.

Generalization Limits#

The inherent limitations in achieving robust generalization within the context of Programming-by-Example (PBE) using Large Language Models (LLMs) represent a critical area of exploration. Fine-tuning LLMs on in-distribution data yields substantial improvements, but this success often fails to generalize to out-of-distribution examples. This highlights a crucial challenge: the model’s reliance on learned patterns specific to its training data, limiting its ability to extrapolate to unseen problem structures. Bridging this distribution gap requires innovative techniques that enable more robust generalization, such as those that leverage algorithm adaptation or incorporate advanced inductive biases to enhance the LLM’s inherent reasoning abilities. Addressing these generalization limits is essential for realizing the full potential of LLMs in solving complex PBE tasks and unlocking their applicability to more diverse, real-world problems.

Adaptation Methods#

Adaptation methods in the context of large language models (LLMs) for programming-by-example (PBE) tasks are crucial for enhancing the models’ ability to generalize to unseen problems. Fine-tuning, a common approach, involves training the LLM on a dataset of program-input-output triples. However, obtaining such datasets can be challenging, particularly for niche domains. The paper proposes an iterative adaptation strategy, starting from a small manually-constructed seed dataset and bootstrapping it by prompting the LLM to generate programs and inputs. The outputs are then obtained through program execution rather than relying solely on the LLM. This approach uses the LLM’s code generation capabilities to create synthetic training data for the task. This iterative adaptation process is similar to a wake-sleep algorithm which allows the LLM to handle out-of-distribution problems more effectively. The key idea is to use the LLM’s generation capabilities to create new training data from a seed dataset, expanding the model’s knowledge base and improving its generalization ability. This addresses the limitation of traditional PBE systems, which rely on restricted domain-specific languages, enabling the use of Turing-complete languages like Python. The success of the adaptation process depends on the selection of a suitable seed dataset that will guide the LLM’s code generation. However, generalization beyond the training distribution remains a significant challenge. The paper also discusses an algorithm to narrow the domain gap, showing that the fine-tuned model can effectively solve a wider range of problems than classical symbolic methods, but highlights the need for continued research on robust out-of-distribution generalization.

Future of PBE#

The future of Programming-by-Example (PBE) is bright, driven by advancements in large language models (LLMs). LLMs show promise in solving typical PBE tasks, potentially increasing the flexibility and applicability of PBE systems. However, challenges remain in achieving robust out-of-distribution generalization. Fine-tuning LLMs on diverse datasets significantly improves performance, but struggles persist when encountering problems far from the training distribution. Addressing this limitation is crucial for broader adoption, potentially through techniques like iterative adaptation or incorporating stronger inductive biases within LLMs. The integration of LLMs with existing symbolic approaches also holds significant potential. This combined approach could leverage the strengths of both paradigms, combining the LLM’s ability to generate diverse solutions with the accuracy and efficiency of symbolic methods. Furthermore, research into techniques for improving the scalability and efficiency of LLM-based PBE systems is needed to enable their deployment on resource-constrained devices and for use by end users.

More visual insights#

More on figures

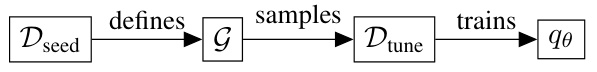

The figure illustrates the data generation pipeline and the fine-tuned model’s inference process. The left side shows how a seed dataset (Dseed) defines a prior (G) over programs, which is then used to generate a larger dataset (Dtune). The right side depicts the fine-tuned LLM (qe) performing inference in a graphical model, using the generated dataset to predict programs given input-output pairs (X,Y). The likelihood in this model is based on program execution, connecting the generated program’s output to the observed outputs.

The figure illustrates the data generation pipeline and the fine-tuned model for program synthesis. The left side shows how a seed dataset (Dseed) is used to generate a larger dataset (Dtune) by prompting a large language model (LLM) and running the generated programs to obtain outputs (Y). The right side displays the graphical model used for fine-tuning the LLM (qe). In this model, the prior over programs (G) is based on the seed dataset, and the likelihood p(Y|p, X) is determined by program execution.

This figure presents the performance of the fine-tuned model on three different domains: lists, strings, and graphics. The x-axis represents the search budget (number of samples generated and evaluated), and the y-axis shows the percentage of problems solved. Each line represents a different model, including various sizes of the fine-tuned model, GPT-4, and GPT-4 with chain-of-thought prompting. The figure demonstrates that the fine-tuned models outperform other baselines, especially in the list and string domains. The relatively flat performance curve for larger search budgets suggests that the fine-tuned models effectively solve most problems within their respective domains.

This figure shows three different domains used to evaluate the effectiveness of LLMs in solving programming-by-example (PBE) tasks. The domains are: (a) List manipulation, which involves simple list processing algorithms; (b) Text editing macros, demonstrating tasks such as date formatting; and (c) Graphics programming using the LOGO/Turtle programming language. The figure highlights the variety of tasks and the varying levels of representation in typical LLM pretraining datasets.

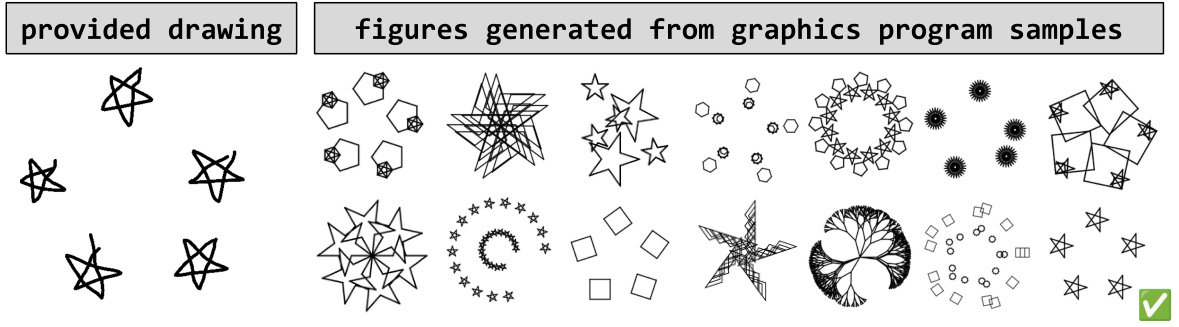

This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to generalize to out-of-distribution data. The model was initially trained on clean, computer-generated LOGO graphics. However, this figure shows the model’s performance when given hand-drawn images as input. While the model’s accuracy decreases, it still generates reasonable programs, indicating a degree of robustness and generalization capability.

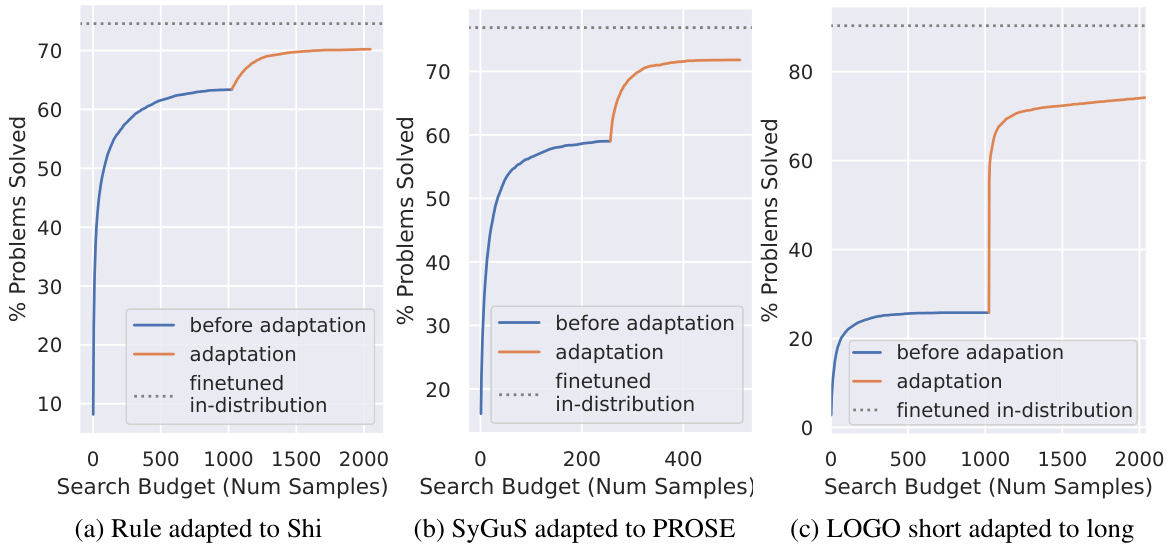

This figure shows the results of out-of-distribution generalization experiments on three different domains: List, String, and Logo. Each subplot displays the percentage of problems solved as a function of the search budget (number of samples). The blue line represents the performance before adaptation, the orange line shows the performance after adaptation, the dotted line shows the finetuned model’s performance on in-distribution problems, and the orange line represents the performance after adaptation. The results demonstrate that while there is some degradation in performance when the model is tested out-of-distribution, adaptation techniques can significantly improve the model’s ability to solve out-of-distribution problems.

This figure visualizes the specific problems solved before and after adaptation on LOGO graphics. Before adaptation, only a few out-of-distribution problems are solvable, often requiring a significant search budget. After adaptation, the system can solve similar out-of-distribution problems more quickly. However, it cannot generalize to problems drastically different from those initially solvable by the fine-tuned model. The results suggest that while adaptation helps, it’s not a complete solution for handling all out-of-distribution problems.

This figure shows the test set performance of the models on three different domains: lists, strings, and graphics. The x-axis represents the search budget (number of samples), and the y-axis represents the percentage of problems solved. The plot shows that the fine-tuned models significantly outperform existing symbolic and neuro-symbolic methods across all domains.

This figure showcases three different domains used to evaluate the effectiveness of LLMs in Programming-by-Example (PBE): lists (algorithms operating on numerical lists), text editing macros (string manipulation), and LOGO/Turtle graphics (geometric drawing). The inclusion of the graphics domain is particularly relevant because it represents a less common programming paradigm, likely under-represented in the datasets used to train large language models. Each domain includes example input-output pairs and the corresponding generated Python program. The intention is to illustrate the broad applicability of LLMs to various programming tasks, some more familiar to LLM training and others less so.

This figure showcases three different domains used to evaluate the effectiveness of LLMs in solving programming-by-example (PBE) tasks. These domains represent varying levels of complexity and representation in typical LLM training data: 1. Lists: Involves manipulating lists of numbers, a common task in programming and well-represented in LLM training data. 2. Graphics: Uses a LOGO/Turtle-based graphics programming language, representing a less common domain likely underrepresented in LLM training data. This demonstrates the model’s ability to generalize to less familiar tasks. 3. Text Editing Macros: Focuses on tasks involving string manipulation common in text-editing applications. This also tests the model’s ability to handle string-based tasks. Each domain includes provided examples (input and output), and the generated program produced by an LLM attempting to solve the PBE task. The selection of these diverse domains helps to thoroughly evaluate the LLM’s generalization capabilities across various programming paradigms and levels of difficulty.

This figure shows examples of hand-drawn LOGO images used as input to test the model’s ability to generalize to out-of-distribution data. A graphical interface was created to allow users to input their own hand drawings. The figure showcases various generated outputs from the model for a sample budget of 64, demonstrating the diversity of generated LOGO programs based on the input hand drawing.

More on tables

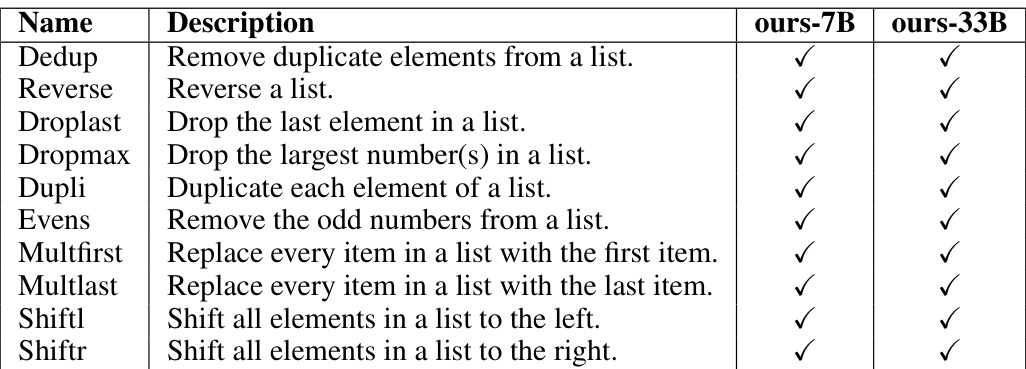

This table presents 10 example list-to-list transformation functions from the benchmark dataset 入². Each function is named, briefly described, and then marked with checkmarks to indicate whether the 7B and 33B models successfully solved the corresponding problem. This demonstrates the model’s success on a range of list manipulation tasks.

This table presents 10 list-to-list functions from the LambdaBeam benchmark [13]. Each function is described, and the last two columns indicate whether the function was solved by the 7B and 33B models, respectively.

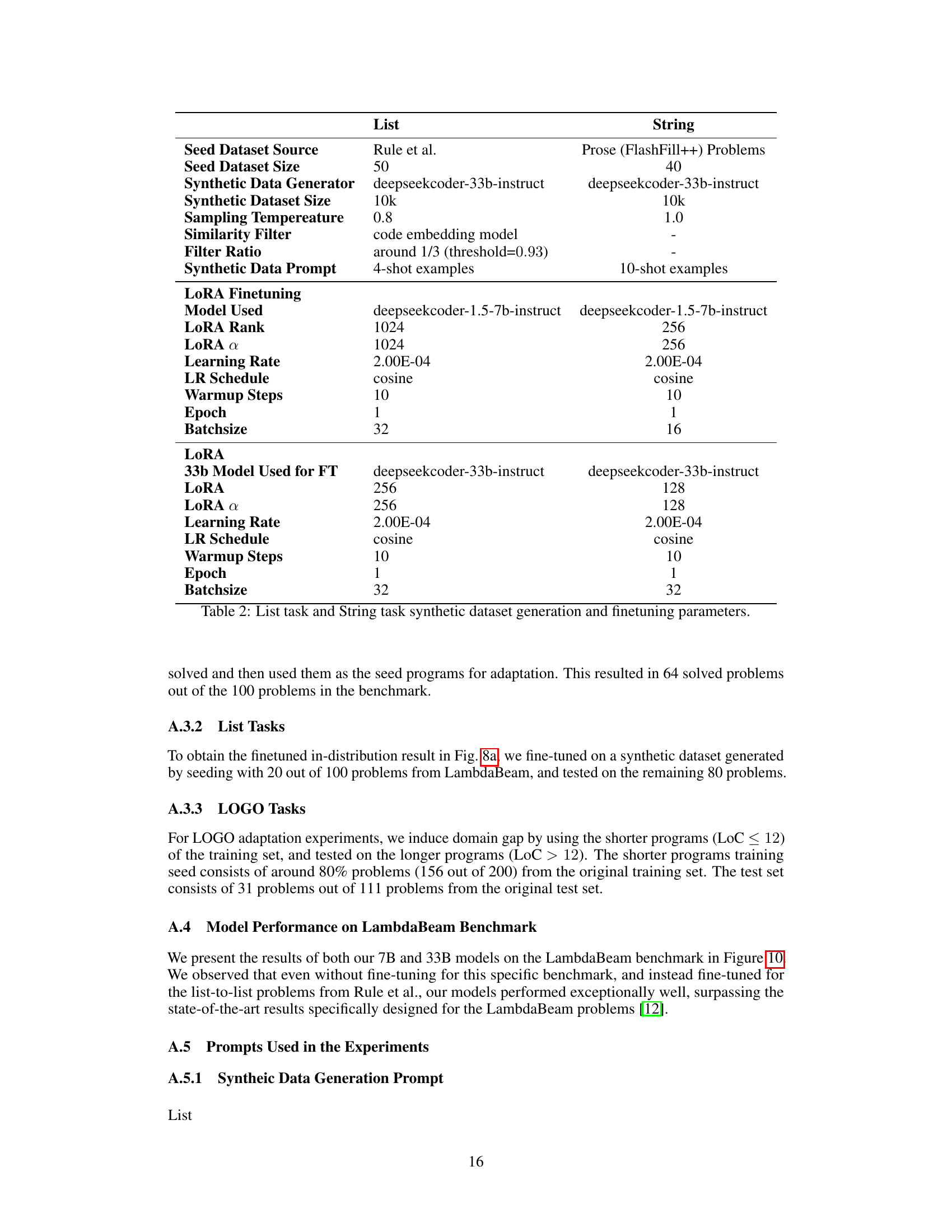

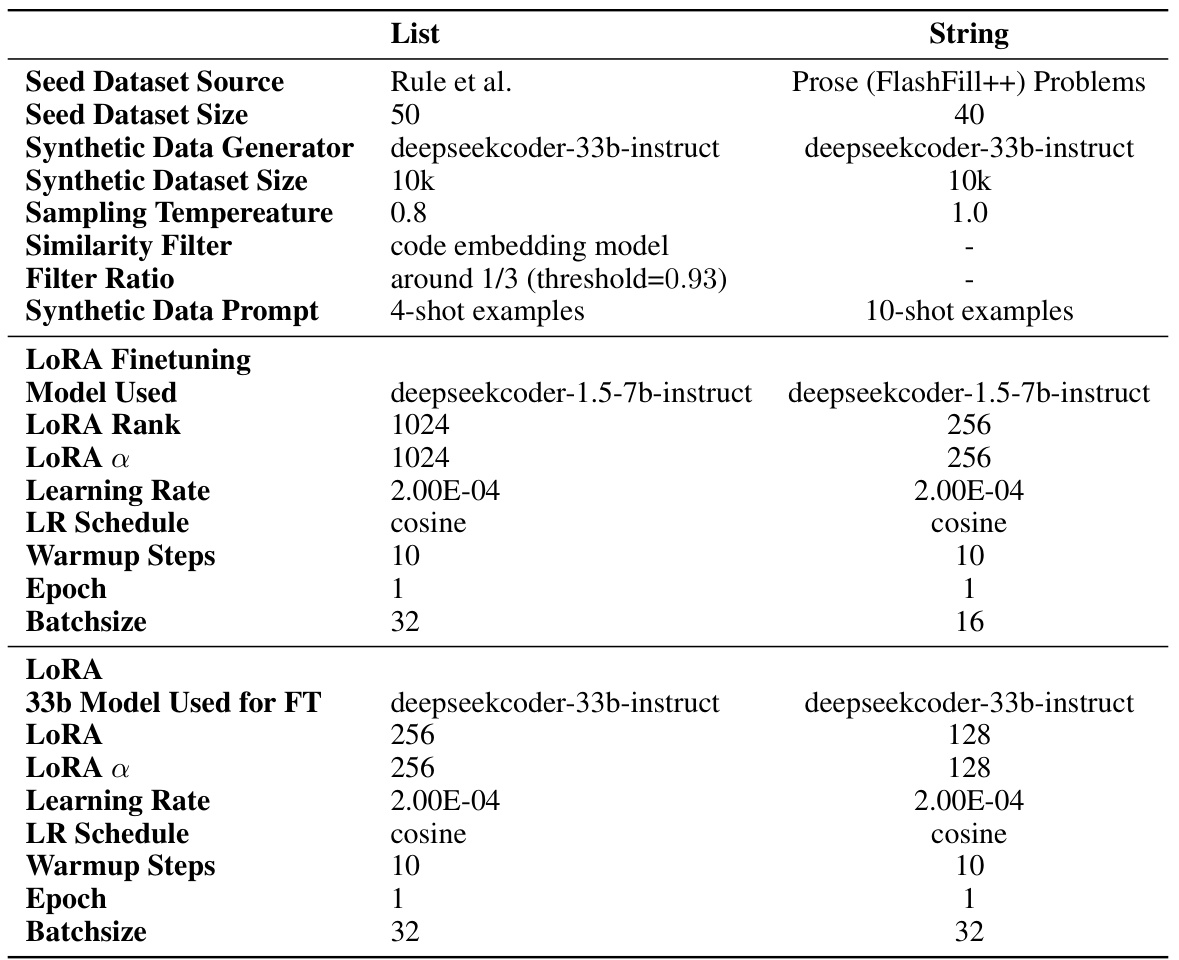

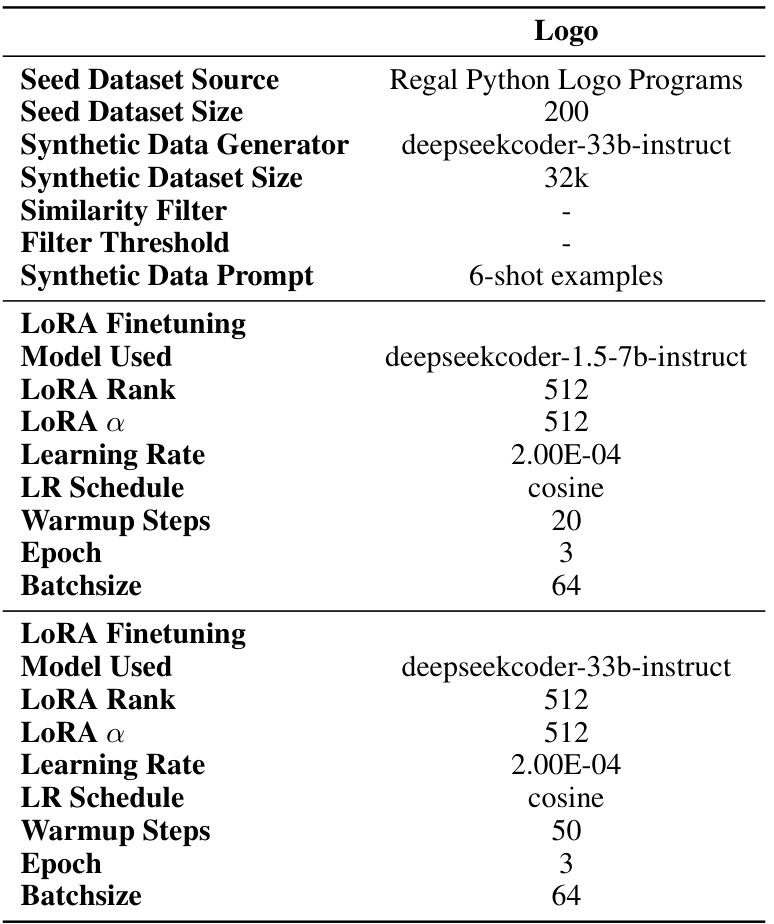

This table details the hyperparameters used in the synthetic dataset generation and fine-tuning processes for both the List and String tasks. It shows the seed dataset source, size, the model used for generating synthetic data, the size of that synthetic dataset, the sampling temperature used, the filter ratio for similarity filtering, and the type of prompt used. The fine-tuning parameters listed include the model used for fine-tuning, the LoRA rank, alpha, learning rate, learning rate schedule, warmup steps, number of epochs, and batch size. It separately shows these settings for a 7B and a 33B model.

This table details the hyperparameters used for generating synthetic datasets and fine-tuning the deepseekcoder model for the LOGO task. It shows the seed dataset source and size, the synthetic data generator model, the synthetic dataset size, similarity filter parameters, the filter threshold, the synthetic data prompt, and the LORA finetuning hyperparameters for both the 7B and 33B models.

This table presents ten different list transformation functions from the λ² benchmark [13]. For each function, a short description is given, along with checkmarks indicating whether the function was successfully solved by the authors’ fine-tuned 7B and 33B models. This demonstrates the models’ performance on a set of well-defined, relatively simple list manipulation tasks.

Full paper#