↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many deep learning optimization algorithms are used in practice without a complete theoretical understanding. Adam, a prominent adaptive optimizer, is no exception. While empirically successful, a comprehensive theoretical analysis of Adam’s behavior, particularly its implicit bias, has remained elusive. This has led to several open questions regarding its fundamental differences compared to other optimizers like gradient descent. This paper seeks to tackle this gap in understanding.

This research focuses on understanding Adam’s implicit bias within the context of linear logistic regression using linearly separable data. The authors prove that when training data is linearly separable, Adam’s iterates converge towards a linear classifier that achieves the maximum l∞-margin, a finding that contrasts with the maximum l2-margin solution typically associated with gradient descent. Importantly, they show this convergence happens in polynomial time for a broad class of diminishing learning rates. The results shed light on the theoretical distinctions between Adam and gradient descent. The study provides a theoretical framework for analyzing Adam’s implicit bias and its convergence characteristics, offering a deeper understanding of its behavior and its practical implications for deep learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the theoretical limitations of Adam, a widely used deep learning optimizer. By clarifying Adam’s implicit bias towards maximum l∞-margin solutions on separable data, it offers valuable insights for algorithm design and optimization strategies in machine learning. This work also opens new research directions in analyzing convergence rates of adaptive optimizers and understanding their implicit regularization properties. These findings have direct implications for improving the efficiency and generalizability of deep learning models.

Visual Insights#

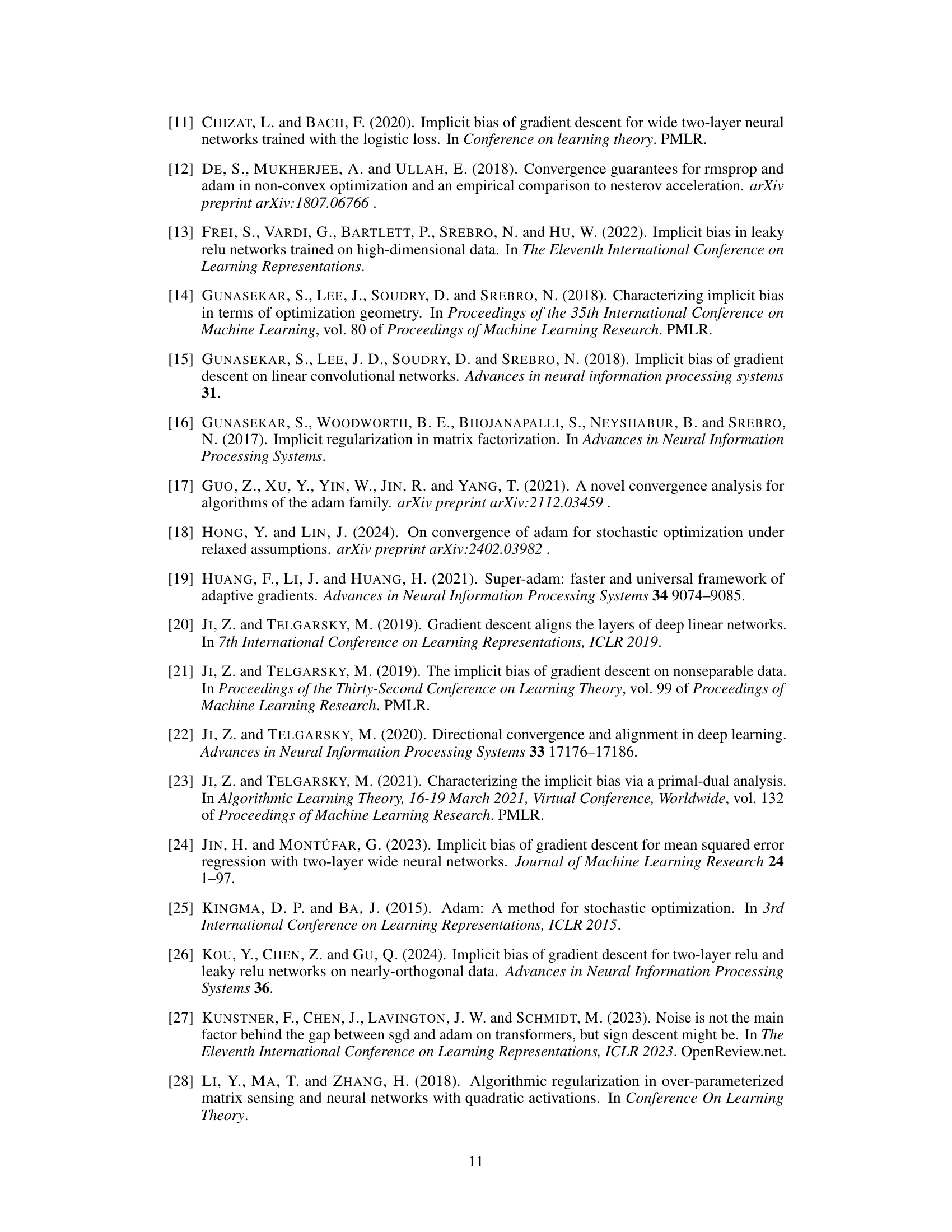

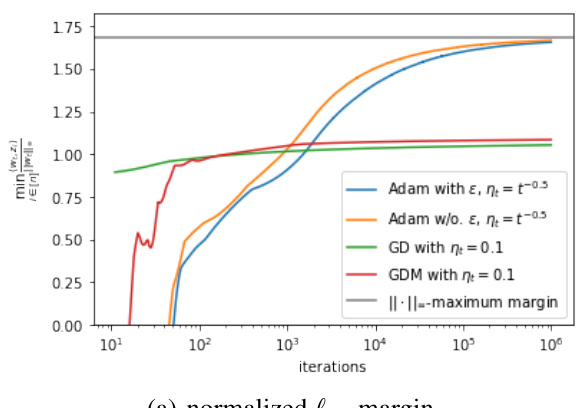

This figure compares the convergence of normalized l∞-margin and l2-margin for four different optimization algorithms: GD, GDM, Adam with and without stability constant (e). The plot shows that Adam (with or without e) converges towards the maximum l∞-margin while GD and GDM converge towards the maximum l2-margin, supporting the paper’s claim that Adam has a unique implicit bias towards maximizing the l∞-margin.

In-depth insights#

Adam’s Implicit Bias#

Adam, a popular optimization algorithm in deep learning, exhibits an implicit bias when training on linearly separable data. This bias, a fascinating area of research, reveals that Adam’s iterates converge towards a solution that maximizes the l∞-margin, a metric quite different from the l2-margin favored by standard gradient descent. This distinction underscores a fundamental difference in how these optimizers navigate the solution space, especially in high-dimensional settings where many solutions exist. The paper explores this implicit bias theoretically, providing insights into Adam’s behavior beyond empirical observations. A key contribution is the analysis of Adam without the stability constant, a more practical setting compared to existing research, thus yielding a more accurate understanding of its convergence behavior. The polynomial-time convergence towards the maximum l∞-margin further distinguishes Adam from its counterparts. While empirical validations support the theoretical findings, the study’s focus on linearly separable data limits its generalizability. Future work should explore the implicit bias in more complex scenarios and datasets to fully understand Adam’s behavior in practical applications.

Linear Classification#

Linear classification, a fundamental machine learning approach, aims to separate data points into distinct classes using a linear decision boundary. Its simplicity makes it computationally efficient and easy to interpret, but its effectiveness hinges on the data’s linearity. When data is linearly separable, meaning a hyperplane can perfectly partition the classes, linear classification achieves high accuracy. However, real-world datasets often exhibit non-linear relationships, which limits linear methods. To address this, strategies like feature engineering can transform data to enhance linearity, and the use of kernel methods allows for the implicit application of linear classification in higher dimensional spaces. Despite its limitations in non-linear scenarios, linear classification remains relevant as a baseline and building block for more complex methods. Its interpretability is crucial in applications where understanding the decision-making process is vital, making it a valuable tool when data allows for its effective use.

Max l∞-margin#

The concept of “Max l∞-margin” in the context of this research paper likely refers to the maximum margin achieved in the direction of the L-infinity norm. This suggests the algorithm prioritizes finding a separating hyperplane that maximizes the minimum distance to any data point, when distance is measured in the L-infinity metric. The L-infinity norm focuses on the largest absolute value among the feature dimensions, making it particularly sensitive to outliers or features with highly varying scales. Thus, this approach likely aims to improve robustness against such issues. The theoretical analysis likely shows how the Adam optimizer, under specific conditions, converges toward this max l∞-margin solution for linearly separable data, potentially offering a novel theoretical perspective on the algorithm’s implicit bias in classification tasks, and demonstrating a fundamental difference from gradient descent which favors maximum l2-margin solutions.

Learning Rate Effects#

The learning rate is a crucial hyperparameter in Adam’s optimization process, significantly impacting its convergence behavior and the resulting model’s performance. Smaller learning rates lead to more stable, gradual convergence, but can be computationally expensive and prone to getting stuck in suboptimal solutions. Conversely, larger learning rates enable faster initial progress, but increase the risk of oscillations or divergence, preventing convergence to a good solution. The choice of learning rate is highly dependent on the specific problem, data characteristics, and model architecture. Adaptive learning rate methods, like those employed by Adam itself, attempt to mitigate these issues by dynamically adjusting the rate throughout training. However, even with adaptation, carefully tuning or scheduling the learning rate, perhaps through techniques such as learning rate decay, often proves essential for optimal performance. Analyzing learning rate effects requires investigating the algorithm’s trajectory, examining loss curves, and assessing generalization capabilities of the resulting model. Ultimately, the optimal learning rate is a delicate balance between speed and stability, requiring careful experimentation and potentially sophisticated scheduling strategies.

Future Research#

The paper’s exploration of Adam’s implicit bias on separable data opens several avenues for future research. Extending the analysis to non-separable data is crucial for real-world applicability, as linearly separable datasets are rare. Investigating the impact of different loss functions beyond logistic and exponential loss would enrich the understanding. Furthermore, analyzing the effect of the stability constant (ε), a key hyperparameter in practice, is needed to bridge the theoretical gap with practical implementations. Studying stochastic Adam and comparing its behavior to the full-batch version would advance theoretical understanding of Adam’s behavior in deep learning settings. Finally, a significant contribution would be developing tighter convergence rate bounds for the l∞-margin, especially for general learning rate schedules beyond the specific polynomial decay schedules. This detailed exploration of the various factors influencing Adam would significantly impact the field of optimization algorithms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

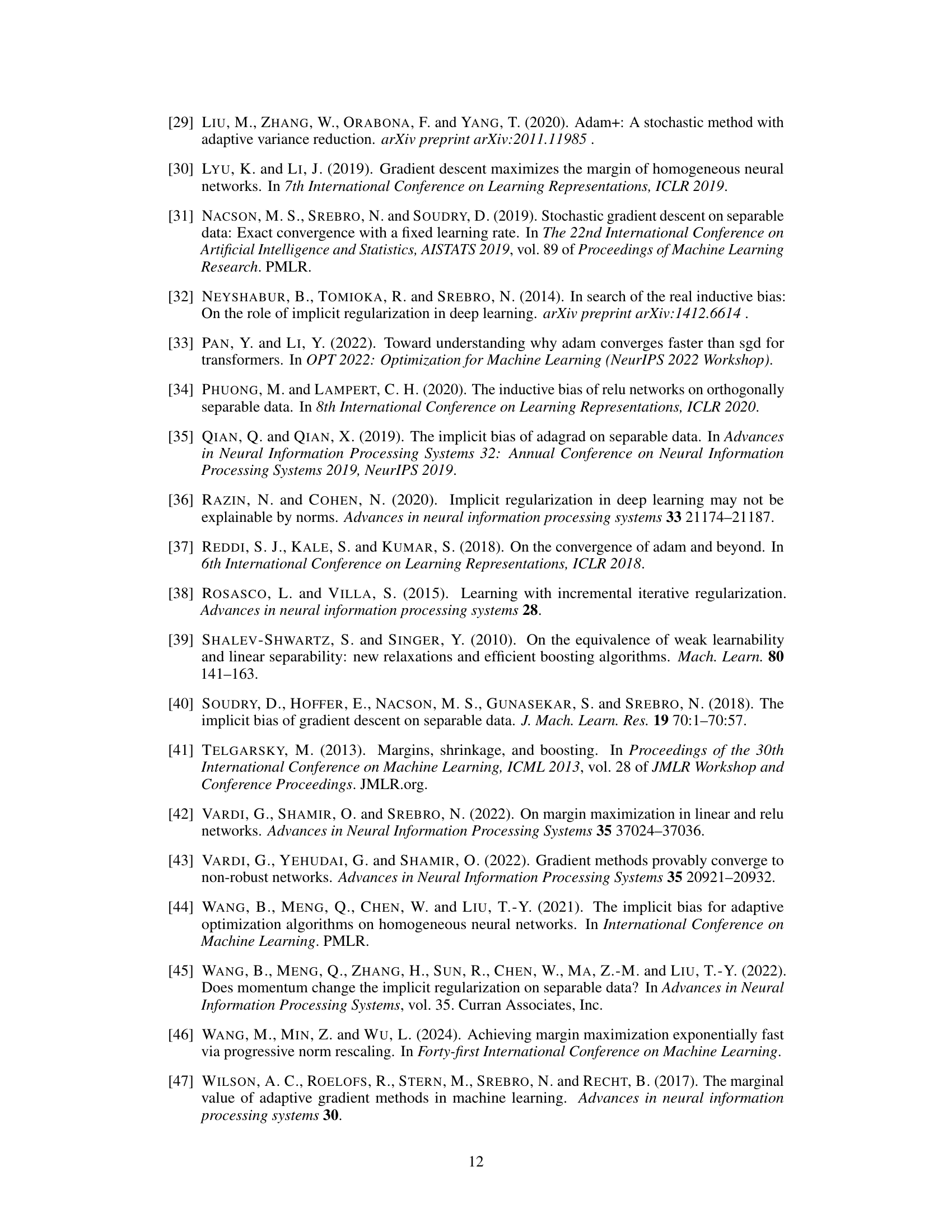

This figure compares the convergence behavior of four different optimization algorithms (Adam with and without stability constant, GD, and GDM) in terms of both l∞-margin and l2-margin. The plots illustrate how the normalized margins change over the number of iterations. The l∞-maximum margin is shown as a reference line, highlighting the algorithm’s implicit bias towards maximizing the l∞-margin in linear classification problems.

This figure compares the performance of four optimization algorithms (Gradient Descent (GD), Gradient Descent with Momentum (GDM), Adam with and without stability constant) in terms of normalized l∞-margin and normalized l2-margin. The results show that Adam, with or without the stability constant, converges to the maximum l∞-margin, while GD and GDM converge to the maximum l2-margin. This difference highlights the unique implicit bias of Adam towards maximizing the l∞-margin.

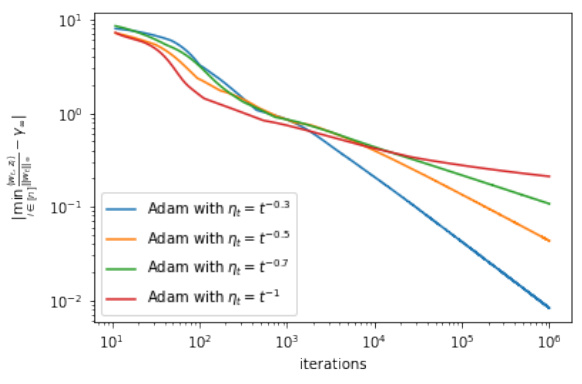

This figure displays the convergence rate of the normalized l∞-margin for Adam with different learning rates (ηt = Θ(t⁻ᵃ) where a ∈ {0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 1}). The log-log plots show the relationship between the number of iterations and the margin gap from the maximum l∞-margin. It demonstrates polynomial-time convergence (a < 1) and logarithmic convergence (a = 1), distinguishing Adam from (stochastic) gradient descent which converges at a speed of O(1/log t).

Full paper#