↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Unsupervised domain adaptation (UDA) tackles the challenge of training machine learning models on data from a different distribution than the test data. Existing UDA frameworks often rely on discrepancy measures based on f-divergence, but these can have limitations in theoretical guarantees and practical performance. Prior works suffered from issues such as overestimating target error, failing to bridge theoretical gap, and achieving slow convergence rates.

This paper presents an enhanced UDA framework. It refines the f-divergence-based discrepancy and introduces a new measure, f-domain discrepancy (f-DD). By removing the absolute value function and adding a scaling parameter, f-DD achieves improved target error and sample complexity bounds. The authors utilize localization techniques to further refine convergence rates, resulting in superior empirical performance on UDA benchmarks. The framework unifies previous KL-based results and demonstrates a clear link between theoretical analysis and algorithmic design.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in domain adaptation as it offers improved theoretical foundations and faster algorithms. It bridges the gap between theory and practice by refining existing f-divergence methods and introducing novel f-domain discrepancy, leading to superior empirical performance and opening new avenues for fast-rate generalization bound research.

Visual Insights#

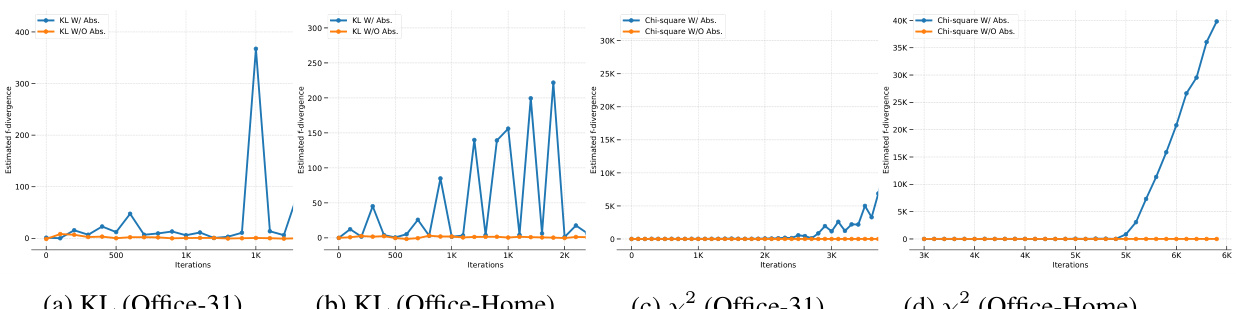

This figure compares the absolute f-divergence with and without absolute value function. The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis shows the estimated f-divergence. The plots show that using the absolute value function leads to an overestimation of the f-divergence, and that the absolute discrepancy measure can easily explode during training. This highlights the importance of using the proposed f-DD measure in domain adaptation.

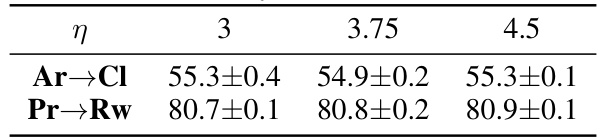

This table presents the classification accuracy achieved by different domain adaptation methods on the Office-31 benchmark dataset. The Office-31 dataset consists of images from three different domains: Amazon (A), Webcam (W), and DSLR (D). Each row represents a different method, and each column shows the accuracy for a specific transfer task (e.g., A→W indicates transferring knowledge from Amazon to Webcam). The results show the average accuracy across multiple trials, along with standard deviations. The methods compared include ResNet-50 (as a baseline), DANN, MDD, KL, f-DAL, and the proposed methods (KL-DD, x²-DD, Jeffreys-DD). The table highlights the superior performance of the proposed f-DD methods, particularly Jeffreys-DD, over previous state-of-the-art approaches.

In-depth insights#

f-Divergence Refined#

A refined f-divergence framework for domain adaptation is a significant improvement over previous methods. The core innovation is likely a novel discrepancy measure that leverages a tighter variational representation of f-divergence, eliminating the absolute value function and adding a scaling parameter. This leads to tighter theoretical bounds on target error and sample complexity, potentially bridging the gap between theory and algorithm observed in prior work. The improved framework also incorporates a localization technique, suggesting an approach to attain faster convergence rates, thereby enhancing both the theoretical guarantees and empirical performance. The proposed f-domain discrepancy (f-DD) is likely more robust, as it avoids potential overestimation issues arising from the absolute value function present in earlier methods. Overall, the paper emphasizes a more nuanced and precise approach to f-divergence in domain adaptation, leading to promising theoretical results and superior empirical performance.

f-DD: Novel Measure#

The proposed f-DD (f-domain discrepancy) offers a novel approach to measuring distributional discrepancies in unsupervised domain adaptation (UDA). Its key innovation lies in refining the f-divergence-based discrepancy, removing the absolute value function used in previous works. This modification leads to tighter error bounds and improved sample complexity without sacrificing non-negativity, bridging the gap between theory and practical algorithms. The introduction of a scaling parameter further enhances the flexibility and effectiveness of f-DD, allowing for recovery of prior KL-based results and achieving fast convergence rates. The use of a localization technique provides a sharper generalization bound, crucial for effective UDA. Empirical evaluations demonstrate superior performance of f-DD-based algorithms compared to prior art. Overall, f-DD presents a theoretically sound and empirically validated approach to UDA with significant improvements in both theoretical understanding and practical implementation.

Localized Bounds#

The concept of “localized bounds” in domain adaptation addresses the challenge of generalization by focusing on regions of the hypothesis space with high probability of containing the optimal hypothesis. Instead of globally analyzing the entire hypothesis space, this approach leverages local properties around a given hypothesis to yield tighter and more informative bounds on the target domain error. This localization technique is particularly crucial when dealing with high-dimensional data or complex models where global discrepancy measures may be overly pessimistic. By focusing on the local behavior, localized bounds offer a refined understanding of the generalization performance and lead to improved error bounds, faster convergence rates, and better practical performance compared to their global counterparts. The key advantages include reduced sensitivity to outliers and improved convergence due to lower variance in local estimates. However, selecting the appropriate region for localization requires careful consideration and depends on the nature of the problem and the specific algorithm employed.

Empirical Results#

An effective empirical results section should present findings clearly and concisely, emphasizing the key contributions. The paper should compare its approach against relevant baselines using appropriate metrics. The choice of benchmarks should be justified, and the results should be presented visually (e.g., tables, charts) to enhance readability and impact. Crucially, statistical significance should be assessed and reported to support the claims and ensure robustness of the findings. The discussion should then analyze the results thoroughly, explaining any unexpected outcomes or limitations, and relating them back to the theoretical framework. Finally, visualizations like t-SNE plots could further strengthen the analysis by offering insightful representations of the data. A strong emphasis on both quantitative and qualitative insights is essential for a persuasive empirical results section.

Future Research#

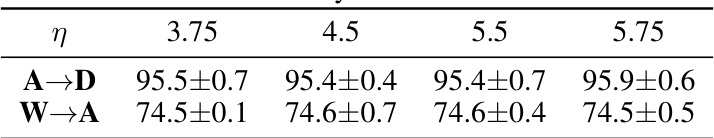

The paper’s conclusion suggests several promising avenues for future work. Improving the theoretical framework by exploring alternative generalization measures, such as the Rashomon ratio, is crucial. A deeper investigation into the impact of the scaling parameter (t) in f-DD and its optimization strategies is needed. The integration of pseudo-labeling techniques or other advanced data augmentation methods with the f-DD framework is important to explore. Extending the f-DD framework to handle more complex settings, like multi-source domain adaptation or situations with label shifts, represents a valuable direction. Finally, empirical evaluations should explore more advanced network architectures to further assess the capabilities and limitations of the proposed method.

More visual insights#

More on figures

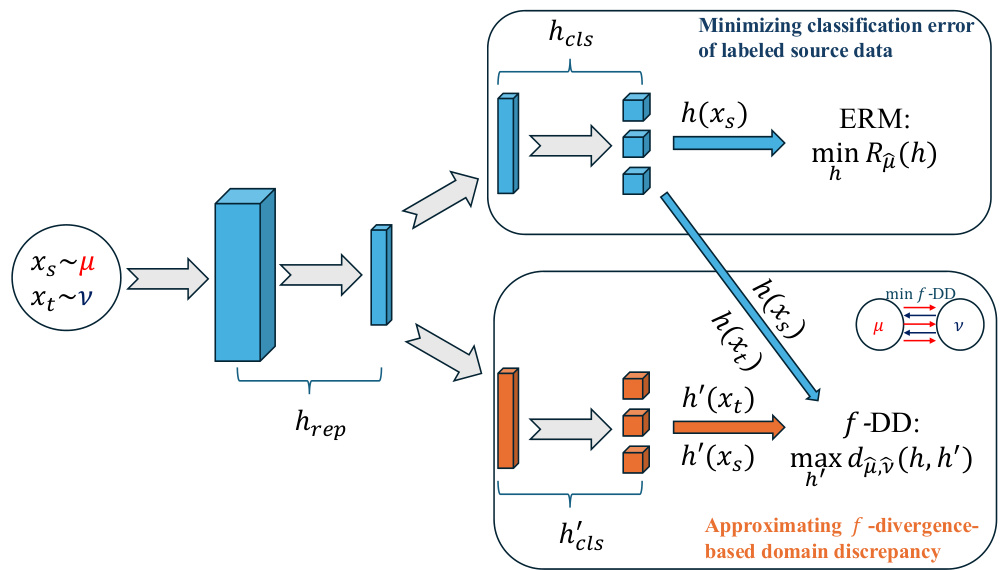

This figure illustrates the adversarial training framework used in the paper for unsupervised domain adaptation (UDA). It shows how the model learns by minimizing both the empirical risk (error) on the labeled source data and the f-domain discrepancy (f-DD) between the source and target domains. The f-DD, a measure of the difference in data distributions, is approximated using an adversarial approach. The figure highlights the two main components of the model: the representation network (hrep) and the classification network (hcls), along with their counterparts in the adversarial component (h’rep and h’cls).

The figure compares the absolute and non-absolute versions of KL and chi-square f-divergences across four different experimental settings (KL on Office-31, KL on Office-Home, chi-square on Office-31, chi-square on Office-Home). It shows that the absolute value version of the discrepancy tends to overestimate the f-divergence, leading to a breakdown in the training process.

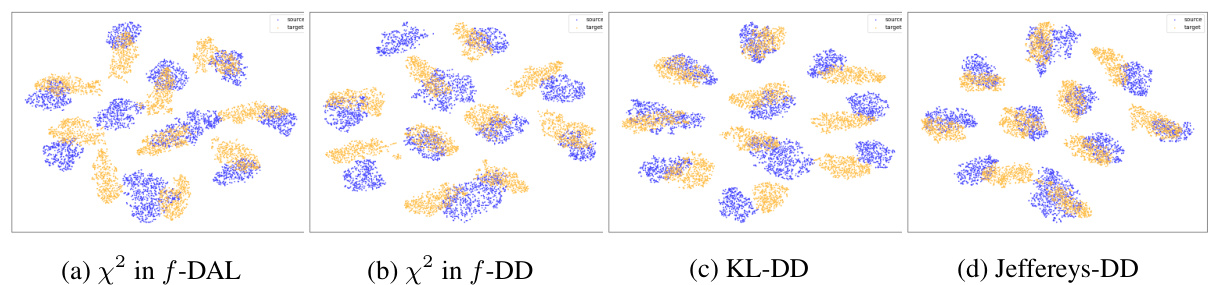

This figure visualizes the results of applying t-SNE to the representations learned by four different domain adaptation methods: f-DAL, f-DD using chi-squared divergence, f-DD using KL divergence, and f-DD using Jeffreys divergence. The source domain (USPS) is represented by blue points, and the target domain (MNIST) is represented by orange points. The visualization shows how well each method aligns the representations of the source and target domains. A better alignment indicates a more successful domain adaptation. The figure aims to show the improved representation alignment from f-DD compared to f-DAL.

More on tables

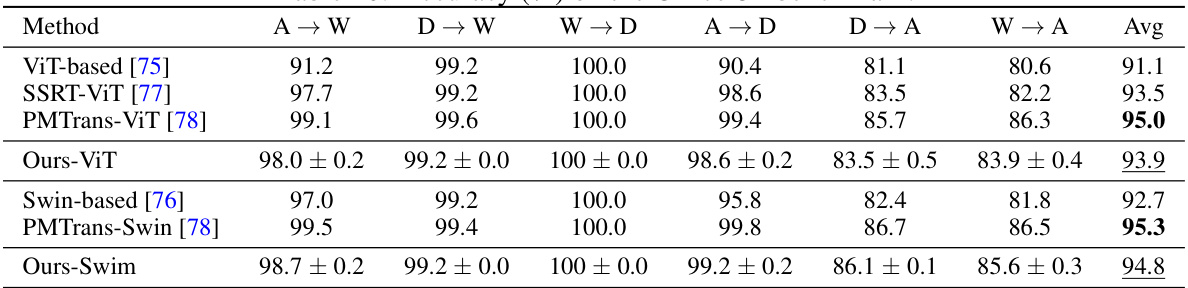

This table presents the accuracy results of different domain adaptation methods on the Office-Home dataset. The Office-Home dataset is more challenging than Office-31, containing four domains instead of three, resulting in a total of 12 transfer tasks. The table compares the performance of the proposed methods (KL-DD, x²-DD, and Jeffereys-DD) against several baselines, including ResNet-50, DANN, and MDD, across all 12 transfer tasks. The average accuracy across all tasks is also reported for each method.

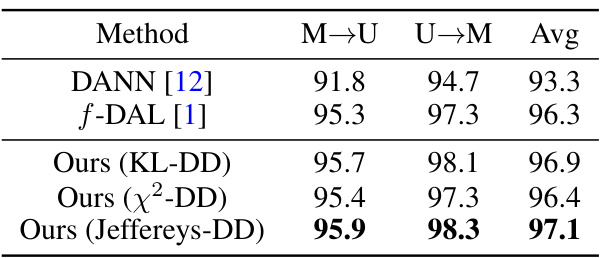

This table presents the accuracy results (%) of different domain adaptation methods on two digits datasets: MNIST to USPS (M→U) and USPS to MNIST (U→M). The methods compared include DANN, f-DAL, and the proposed KL-DD, x²-DD, and Jeffereys-DD methods. The average accuracy across both tasks is also provided for each method.

The table compares the performance of KL-DD and OptKL-DD on three benchmark datasets: Office-31, Office-Home, and Digits. OptKL-DD is a modified version of KL-DD that incorporates an optimization for the scaling parameter t. The results show that OptKL-DD does not significantly improve upon KL-DD across the three datasets.

This table presents the classification accuracy achieved by different domain adaptation methods on the Office-31 benchmark dataset. The Office-31 dataset contains images from three different domains (Amazon, Webcam, and DSLR) and 31 classes. The table shows the performance of various methods including ResNet-50 (source only), DANN, MDD, KL, f-DAL (from the paper being analyzed), and three variations of the proposed method (KL-DD, x²-DD, and Jeffereys-DD). Results are reported as mean accuracy ± standard deviation across different domain transfer tasks (e.g., Amazon to Webcam, Webcam to DSLR). The average accuracy across all tasks is also provided for each method. This allows for a comparison of the proposed method’s performance against existing state-of-the-art domain adaptation techniques.

This table compares the performance of the proposed Jeffereys-DD method with the f-DAL method and its combination with implicit alignment. The results show that Jeffereys-DD achieves higher accuracy on both the Office-31 and Office-Home datasets, demonstrating its effectiveness in domain adaptation.

This table presents the accuracy of different domain adaptation methods on the Office-31 benchmark. The benchmark consists of three domains: Amazon (A), Webcam (W), and DSLR (D). The table shows the accuracy for different domain transfer tasks (e.g., A→W, W→D, etc.) for several methods including ResNet-50 (as a baseline), DANN, MDD, KL, f-DAL (from the paper being referenced), and the proposed KL-DD, x²-DD, and Jeffreys-DD methods. The results are reported as average accuracy and standard deviation across multiple runs.

This table presents the accuracy results (%) of different domain adaptation methods on the Office-Home benchmark dataset. Office-Home has four domains: Artistic images (Ar), Clip Art (Cl), Product images (Pr), and Real-world images (Rw). The table shows the accuracy for each domain adaptation task (e.g., Ar→Cl, Ar→Pr, etc.) for various methods including ResNet-50 (a baseline), DANN, MDD, f-DAL (the method the authors are improving), and their proposed KL-DD, x²-DD, and Jeffreys-DD. The average accuracy across all tasks is also reported for each method.

This table presents the accuracy results (%) of different domain adaptation methods on the Office-31 benchmark. The Office-31 benchmark consists of three domains: Amazon (A), Webcam (W), and DSLR (D). The table shows the accuracy for various transfer tasks between these domains (e.g., A→W, W→D, etc.), and the overall average accuracy across all transfer tasks. Methods compared include ResNet-50 (source-only), DANN, MDD, KL (a different method using Jeffreys divergence), f-DAL, and the authors’ proposed KL-DD, x²-DD, and Jeffreys-DD.

The table compares the accuracy of different domain adaptation methods on the Office-31 benchmark dataset. It shows the accuracy of several methods across different domain transfer tasks (A→W, D→W, W→D, A→D, D→A, W→A) and reports the average accuracy. The methods include ResNet-50 (source-only), DANN, MDD, a KL-based method, f-DAL, and three variations of the proposed KL-DD, x²-DD, and Jeffreys-DD methods.

Full paper#