↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current video editing techniques struggle with accurate and localized modifications, particularly concerning motion control. Most methods focus on visual content changes, neglecting the nuanced control over motion, limiting the realism and fine-grained editing capabilities. This lack of integrated motion editing hinders the creation of high-quality, personalized videos.

ReVideo tackles this challenge by allowing users to specify both content and motion precisely within specific video regions. It uses a three-stage training process to decouple content and motion for more accurate control, along with a novel fusion module to combine these inputs effectively. The results demonstrate superior performance in various editing scenarios, including independent content/motion control and simultaneous adjustments, showcasing the method’s flexibility and robustness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents ReVideo, a novel approach to video editing that allows for precise control over both content and motion. This addresses a significant limitation of existing methods, which primarily focus on content manipulation. ReVideo’s ability to seamlessly integrate content and motion editing opens up new avenues for research in video generation and manipulation, pushing the boundaries of what’s possible with video editing.

Visual Insights#

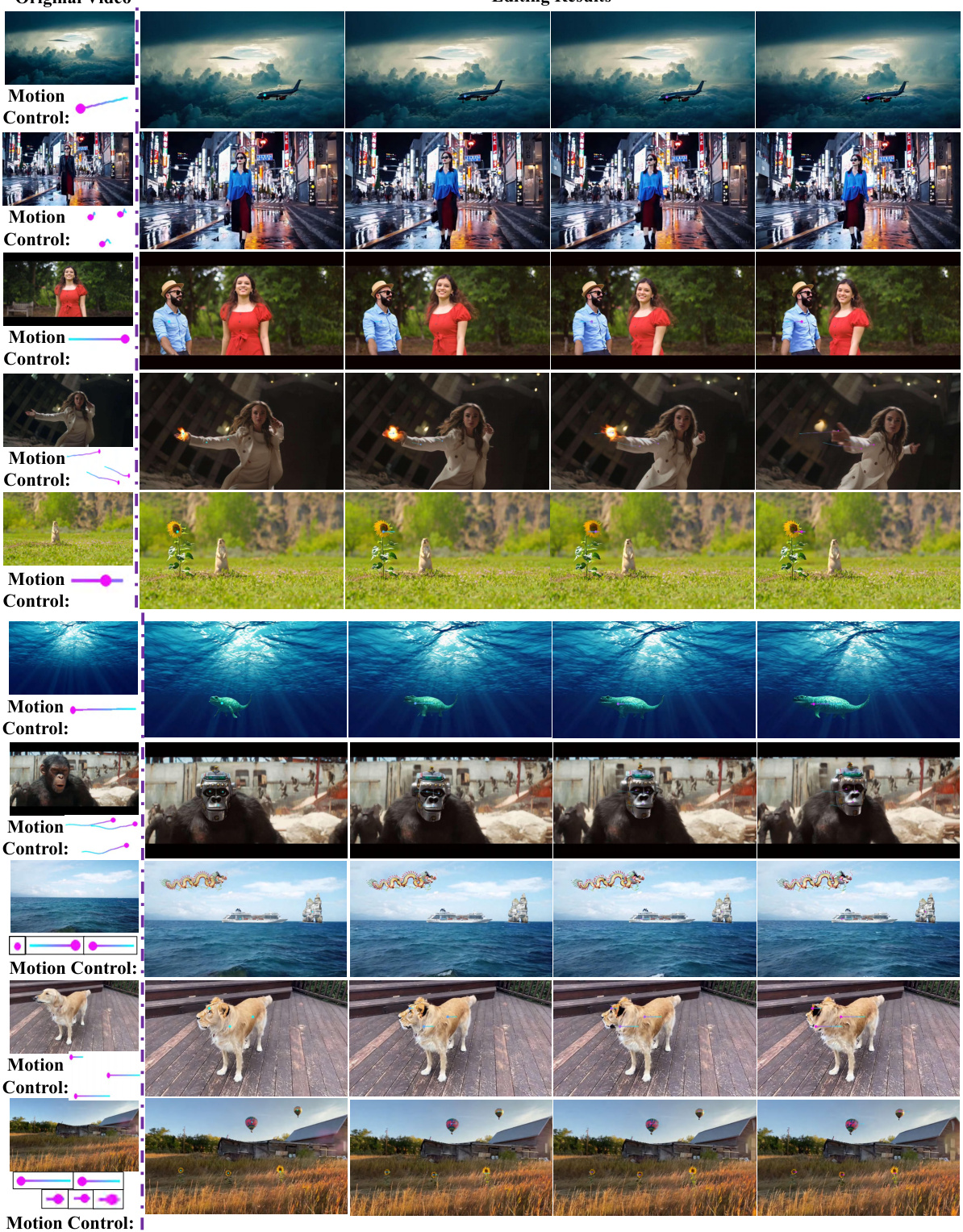

This figure demonstrates the ReVideo model’s ability to perform localized video editing by modifying both the content and motion of specific video regions. It showcases five examples of video editing tasks: changing content and trajectory, changing content while keeping the trajectory, keeping the content while customizing trajectory, adding new object-level interactions, and editing multiple areas simultaneously. Each row shows the original video segment, followed by the result of applying ReVideo with the indicated content and motion modifications. The motion control is visually represented by colorful lines on the video.

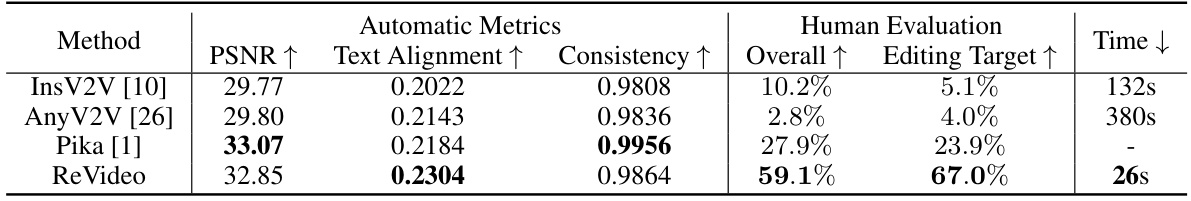

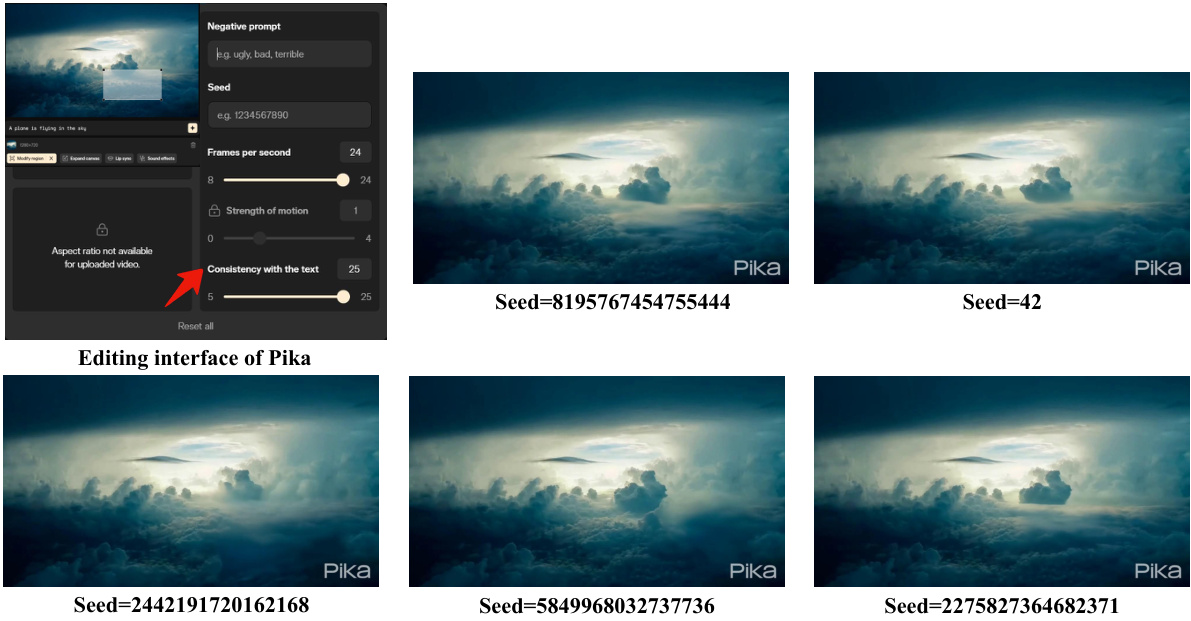

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed ReVideo model with three other existing video editing methods: InsV2V, AnyV2V, and Pika. The comparison uses both automatic metrics (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), CLIP text alignment score, and consistency score) and human evaluation (overall quality and editing target accuracy). The time taken for each method to perform the editing task is also included. The results show ReVideo’s superior performance across most metrics, indicating improved accuracy and efficiency in video editing.

In-depth insights#

Motion-Content Fusion#

The concept of ‘Motion-Content Fusion’ in video editing is crucial for achieving realistic and high-quality results. It tackles the challenge of seamlessly integrating manipulated content with the existing motion of a video. A naive approach might independently process motion and content, leading to jarring inconsistencies. A successful fusion strategy requires careful consideration of how these two aspects interact, likely through an intermediate representation that considers both visual information and motion vectors. This might involve using techniques like optical flow estimation to understand pre-existing motion, allowing for the synthesized content to seamlessly match existing trajectories. Furthermore, the fusion process must be robust to variations in lighting and texture. Methods like spatiotemporal adaptive fusion modules can dynamically weigh the contributions of motion and content at different spatial locations and temporal stages, ensuring a natural blend that minimizes artifacts. Ultimately, a successful ‘Motion-Content Fusion’ method will produce video edits that are perceptually indistinguishable from authentic footage, providing users with a powerful and intuitive tool for creative video manipulation.

Three-Stage Training#

A three-stage training strategy is employed to effectively address the inherent imbalance and coupling between content and motion control in video editing. The first stage focuses on establishing a strong motion control prior by training solely on motion trajectories, enabling the model to learn and understand motion dynamics independently. This decoupling is crucial, as the second stage then introduces content editing by training on data where edited content and unedited content are sourced from distinct videos. This isolates the motion control aspect from the influence of static content. This separation enhances the ability to control both aspects precisely. The final stage refines the model by fine-tuning specific components, thereby removing any residual artifacts or inconsistencies between the edited and unedited regions. This three-stage process is carefully designed to progressively resolve training complexities, resulting in a robust model that can accurately and seamlessly control both visual content and motion trajectories in videos.

Adaptive Fusion Module#

The Adaptive Fusion Module is a crucial component for effectively integrating content and motion controls within the video editing process. Its adaptive nature is key; it’s not a static merger of content and motion features, but rather a dynamic weighting mechanism that adjusts based on the temporal stage of the diffusion process and the spatial location within the video frame. This adaptive weighting, represented by a weight map (Γ), ensures that the influence of content and motion signals is appropriately balanced throughout the video generation. The module intelligently prioritizes the contribution of unedited content where it’s abundant and emphasizes motion control in areas requiring modification. This nuanced approach addresses the inherent imbalance between the dense and readily available unedited content and the sparse, abstract motion trajectories. This carefully designed fusion is vital for high-quality, localized video editing, especially in scenarios with complex motion or intricate content details. The spatiotemporal awareness of the module is a significant improvement over simple merging techniques, avoiding the common issue of motion control being overridden by the strong influence of pre-existing content. Ultimately, the Adaptive Fusion Module allows for the seamless merging of separately controlled content and motion information, producing realistic and high-quality video edits that are both locally precise and globally consistent.

Local Video Editing#

Local video editing, as explored in the provided research paper, presents a significant challenge in the field of video generation and manipulation. Existing methods often struggle with achieving both accurate and localized modifications, particularly concerning motion. The paper highlights the need to address the inherent difficulty of decoupling content and motion controls during the editing process. A key insight is the importance of carefully managing the interaction between user-specified edits and the existing video content; this requires sophisticated techniques to integrate modifications seamlessly into the original material without introducing artifacts or inconsistencies. The use of trajectory-based motion control and three-stage training are crucial in this regard, progressively improving the decoupling of content and motion and thereby increasing precision. The effectiveness of a spatiotemporal adaptive fusion module underscores the need for flexible, context-aware fusion of control signals, preventing the model from overly relying on pre-existing content at the expense of user-defined modifications. Successfully achieving this requires sophisticated strategies such as progressive decoupling, and adaptive module integration for robust and accurate control in local video editing.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the handling of complex scenes and dynamic backgrounds is crucial, as current methods struggle with significant scene changes or intricate lighting effects. Expanding the scope to handle more intricate motion editing tasks like realistic object manipulation, would be beneficial. A key area of improvement is refining motion control for better accuracy and user-friendliness, possibly through the incorporation of advanced interaction techniques. Addressing the computational cost, especially for long videos, is necessary for wider applicability. This may involve exploring more efficient network architectures or training strategies. Finally, extending the framework to support other video editing tasks such as inpainting, colorization, or style transfer could significantly enhance its capabilities. Investigating the potential benefits and challenges of integrating these tasks with motion and content control is worth pursuing.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates two architectural approaches for integrating motion and content control into a Stable Video Diffusion (SVD) model for video editing. Structure A uses a single trainable control module to fuse both content and motion information before feeding it into the SVD. This approach is more compact and efficient. In contrast, Structure B employs separate control modules for motion and content, which are then integrated into the SVD. While offering more independent control, this method increases complexity.

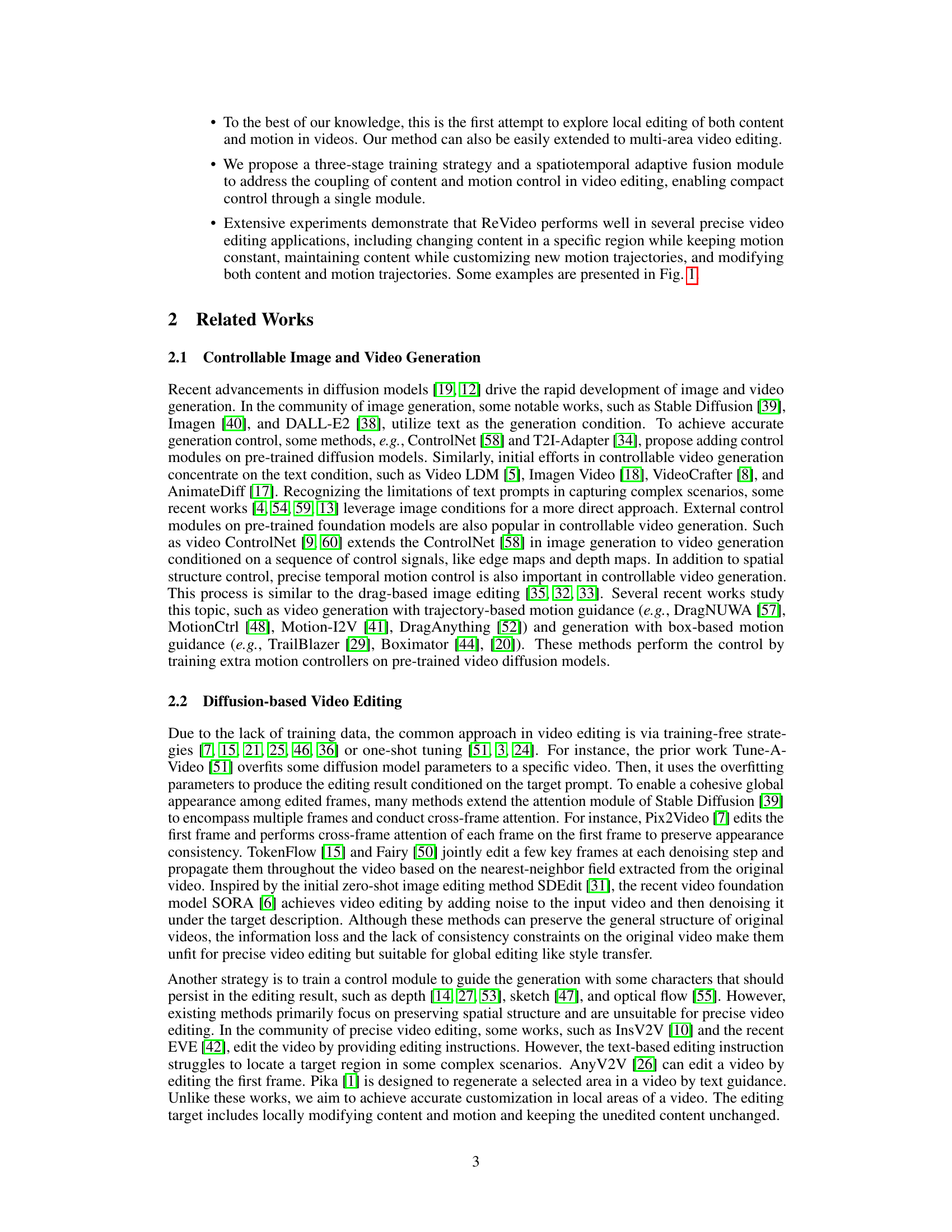

This figure presents a comparison of the motion control capabilities of two different architectures (Structure A and Structure B) from Figure 2, using various training strategies. Each row shows the results of a toy experiment, focusing on a specific area of a video. The results highlight the challenges in decoupling motion and content control during video editing, with various training approaches impacting the ability to control the motion independently from the unedited content.

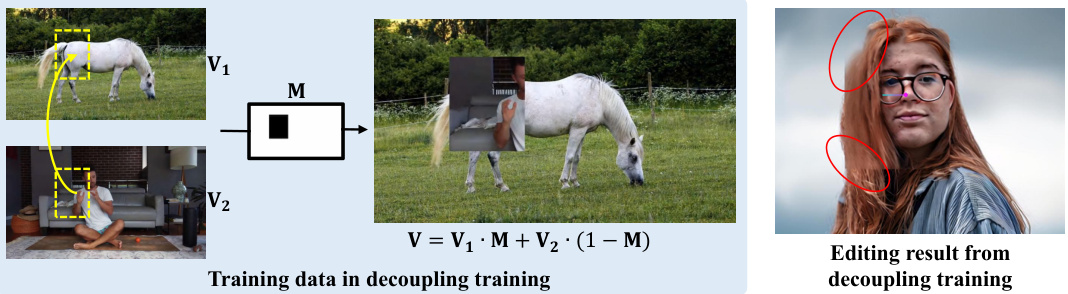

This figure demonstrates the data augmentation strategy used in the decoupling training stage. The goal is to decouple the learning of content and motion by presenting the model with training data where the content and motion are from separate video sources. The figure shows the process of combining two videos (V1 and V2) using a mask (M) to create a training sample (V) where the masked region has content from V1 and motion from a trajectory, and the unmasked region has content from V2. The result shows the successful separation of content and motion, leading to improved editing results, reducing artifacts at the boundary between edited and unedited regions. The right image shows an example of an editing result from this decoupling training strategy.

This figure illustrates the Spatiotemporal Adaptive Fusion Module (SAFM) used in ReVideo. The left side shows the architecture of the SAFM, which takes content and motion encodings as inputs, uses a sigmoid layer to generate a weight map Γ, and combines the content and motion information to generate a fused condition feature fc. The right side displays the visualization of the weight map Γ at different timesteps during the video generation process. The weight map shows how the contribution of content and motion is dynamically balanced during the generation process.

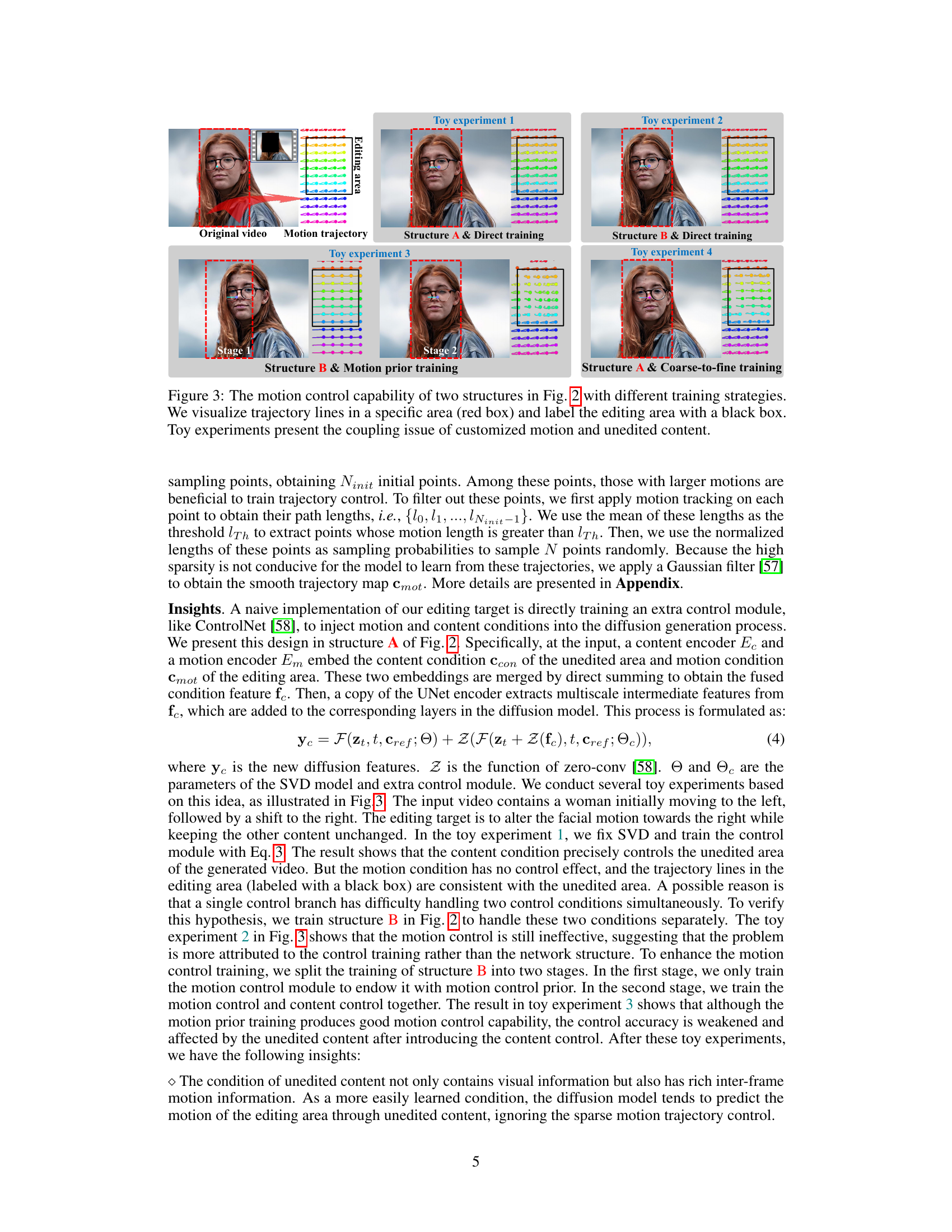

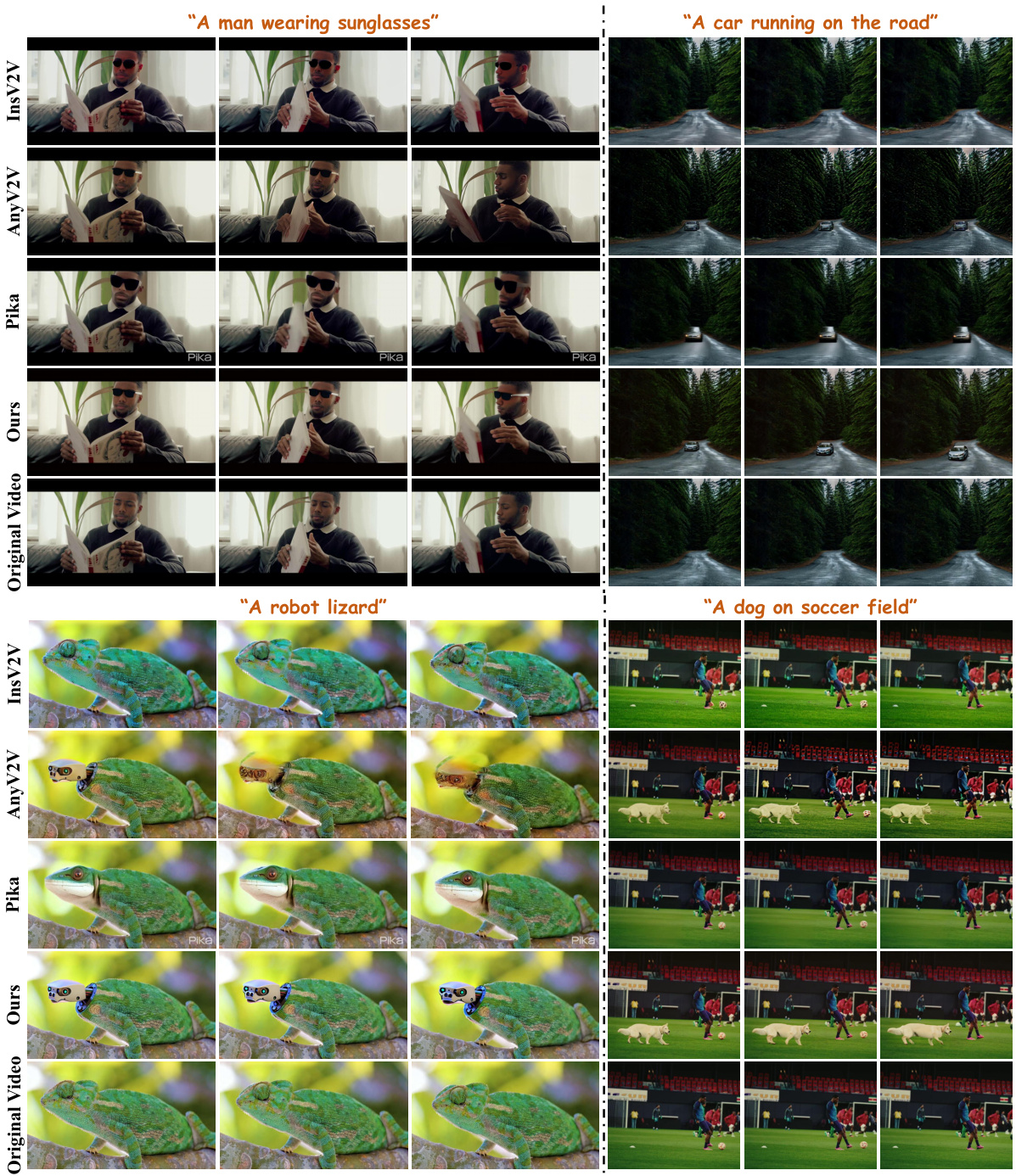

This figure presents a visual comparison of video editing results from four different methods: InsV2V, AnyV2V, Pika, and the proposed ReVideo method. Four example video editing tasks are shown, each displayed across the four methods. The goal is to demonstrate the ability of ReVideo to accurately edit both the content and motion of specific video regions, while maintaining the quality of unedited portions. The results highlight ReVideo’s superior performance in terms of visual fidelity, accurate content editing, and realistic motion control compared to the baseline methods.

This figure presents an ablation study of the ReVideo model, showing the effects of removing or modifying different components of the model. The top row shows the results without using the Spatiotemporal Adaptive Fusion Module (SAFM), and with SAFM but without time adaptation. The bottom row demonstrates results from tuning all control modules in stage 3, tuning only the spatial layers in stage 3, and finally the complete ReVideo model. The visual differences highlight the importance of each component in achieving accurate and high-quality video editing.

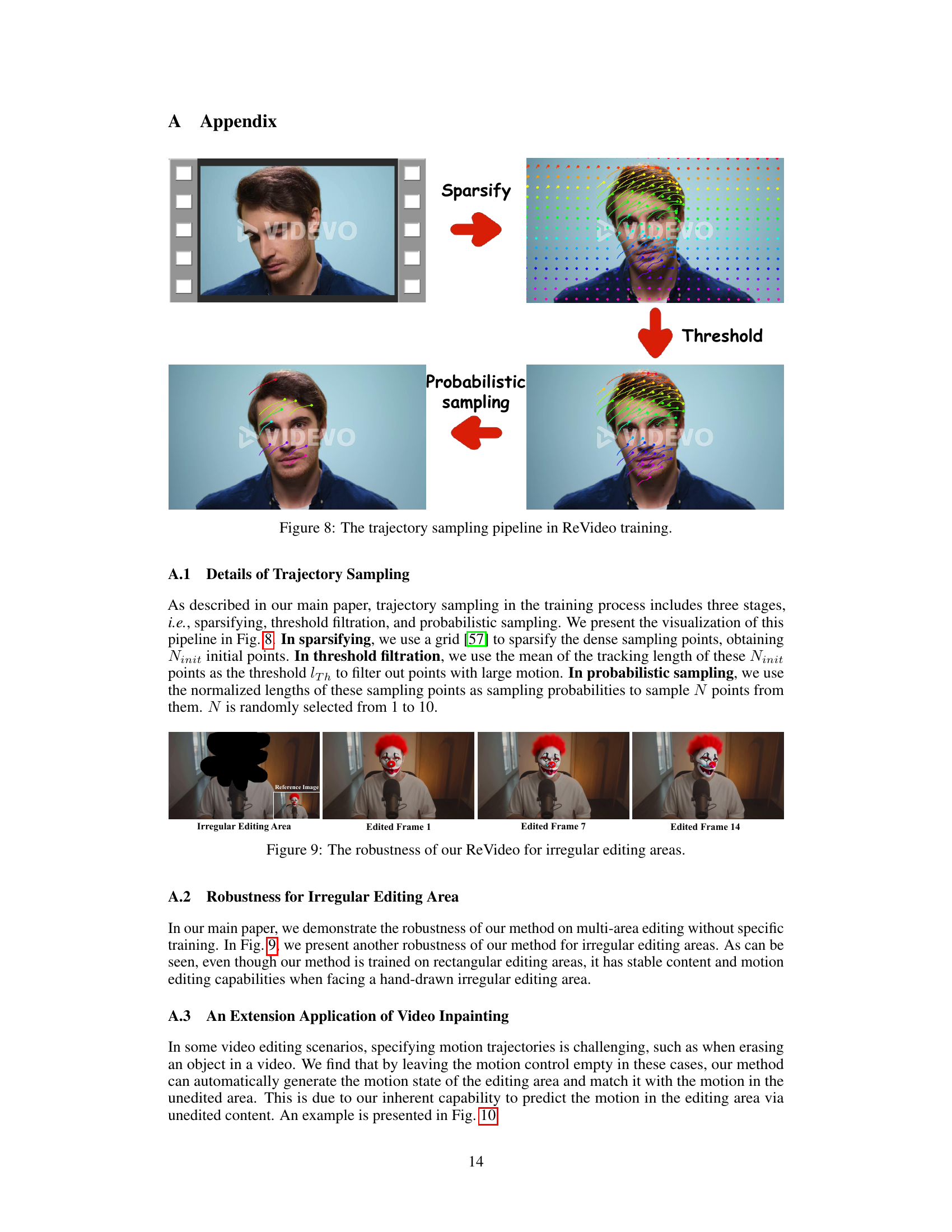

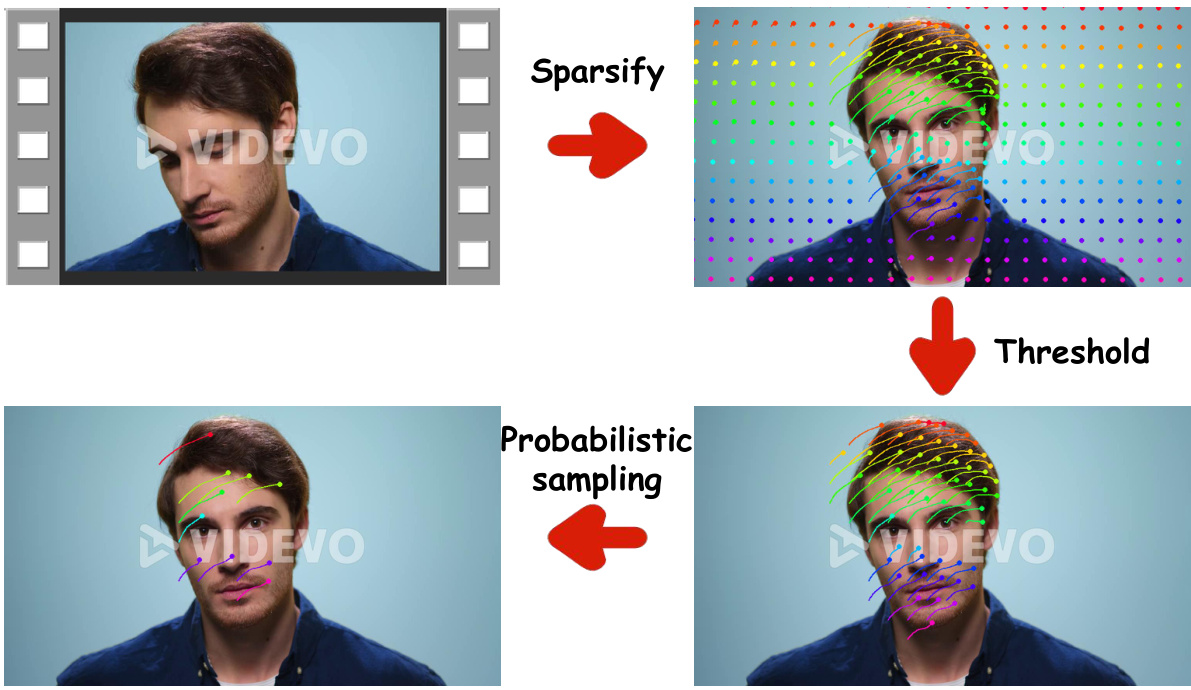

The figure illustrates the three-stage trajectory sampling pipeline used in the ReVideo training process. First, the dense sampling points are sparsified using a grid. Then, a threshold is applied to filter out points with motion lengths below a certain threshold. Finally, probabilistic sampling is performed, using the normalized motion lengths as probabilities to select a subset of points for the final trajectory map. This process ensures that the resulting trajectory map is both representative of the video’s motion and sufficiently sparse for efficient training.

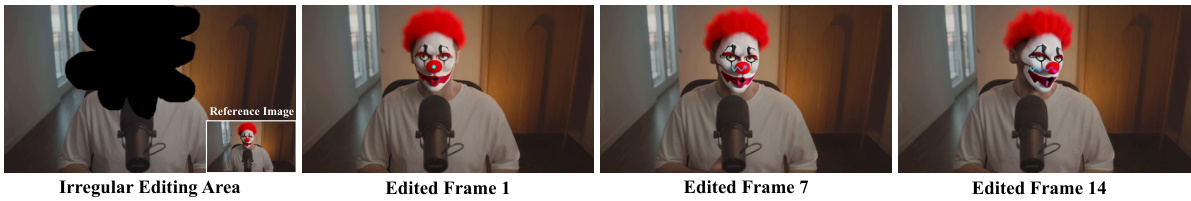

This figure demonstrates the robustness of the ReVideo model when handling irregular editing areas. Despite being trained on rectangular editing regions, the model successfully edits both content and motion in an area defined by a hand-drawn, irregular mask. The results show consistent editing across multiple frames (frames 1, 7, and 14 are shown). This highlights the model’s adaptability and flexibility beyond its training data.

This figure demonstrates ReVideo’s ability to precisely edit both content and motion within a video. It showcases four different editing scenarios: changing content while keeping the original trajectory, changing the trajectory while preserving the original content, changing both content and trajectory, and performing multi-area editing. Each scenario highlights the precision of the editing by using colorful lines to indicate the controlled motion trajectories. The figure visually displays that the method allows localized modifications to videos, and its application can extend to multiple areas simultaneously.

This figure shows two example scenarios demonstrating the challenges of applying the ReVideo method to more complex videos. The top row shows a video with a dynamic background and complex lighting, illustrating how the method attempts to integrate edits within a visually busy context. The bottom row demonstrates a scene change within the video sequence, highlighting the difficulties the approach faces in maintaining consistency across significant visual shifts.

This figure demonstrates the ReVideo model’s ability to perform local modifications on video content and motion. The top row shows the original video frames. Subsequent rows illustrate different editing scenarios: changing content while preserving the original trajectory, changing the trajectory while maintaining the original content, and simultaneously changing both content and trajectory. Colorful lines highlight the motion control applied in each edited video.

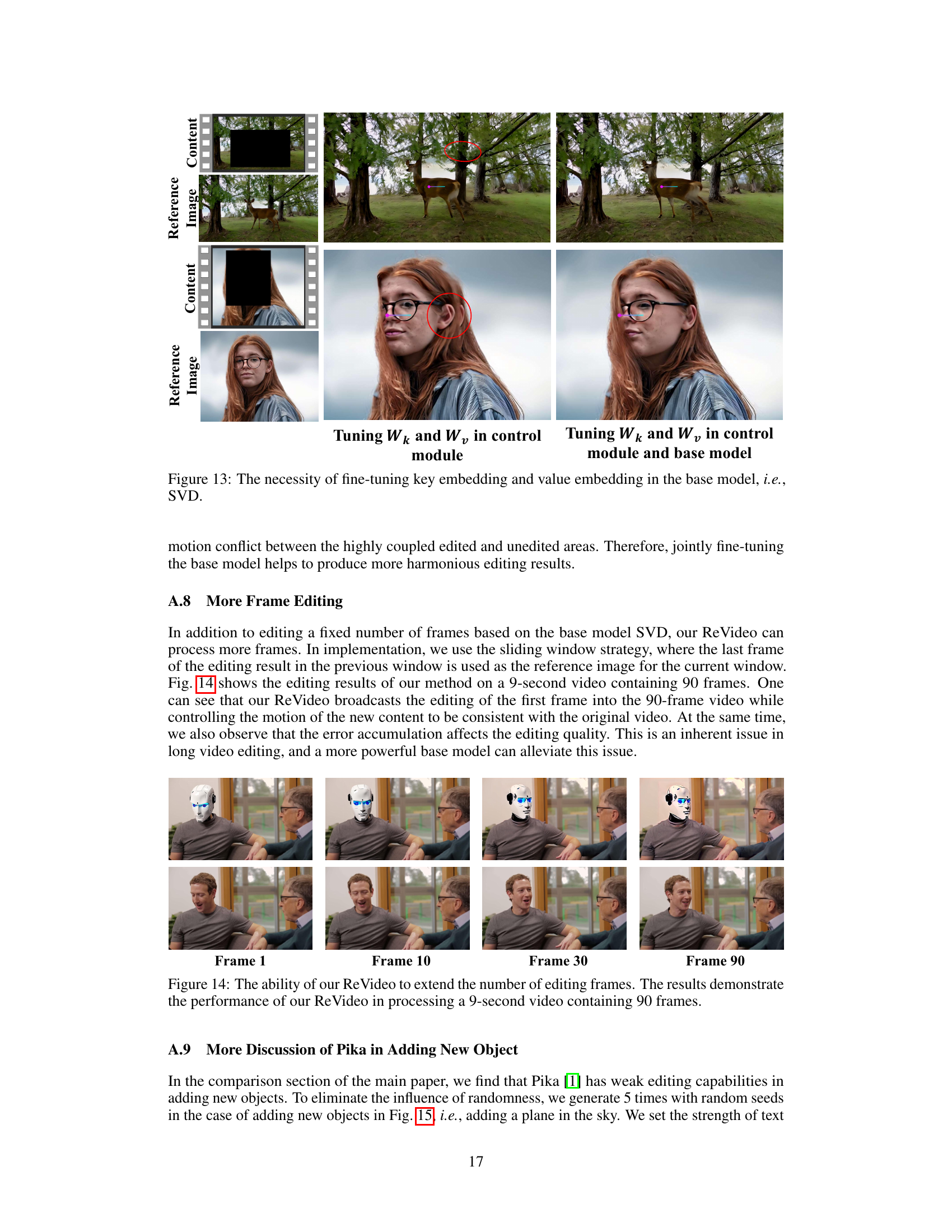

This figure shows the results of two ablation studies. In the first ablation study, only the key and value embeddings in the control module were fine-tuned. In the second ablation study, both the key and value embeddings in the control module and the base model were fine-tuned. The results show that fine-tuning both the control module and the base model leads to better results in terms of visual quality and consistency. The images demonstrate that fine-tuning the base model, in addition to the control module, helps to mitigate artifacts that can occur from the mismatch between the edited and unedited regions of the video.

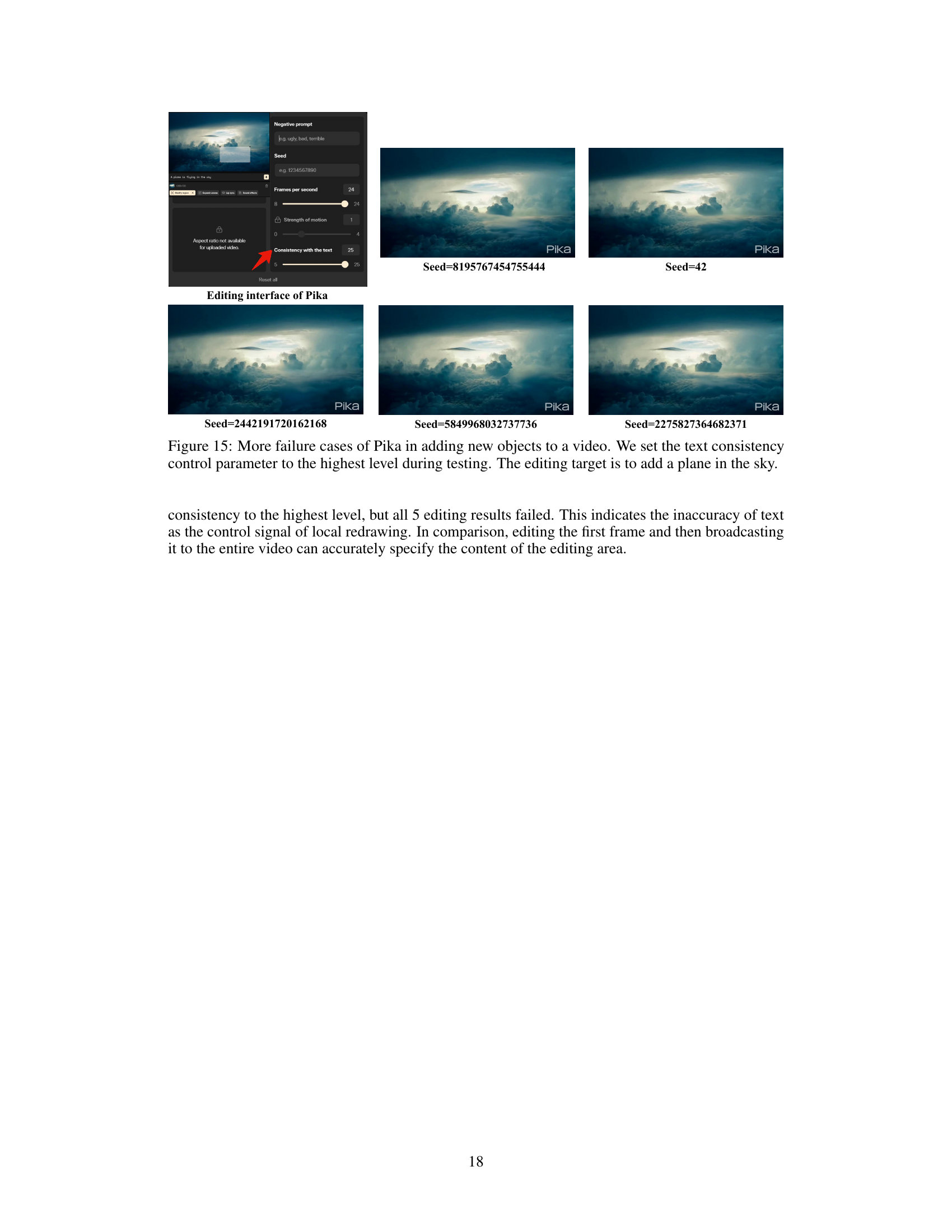

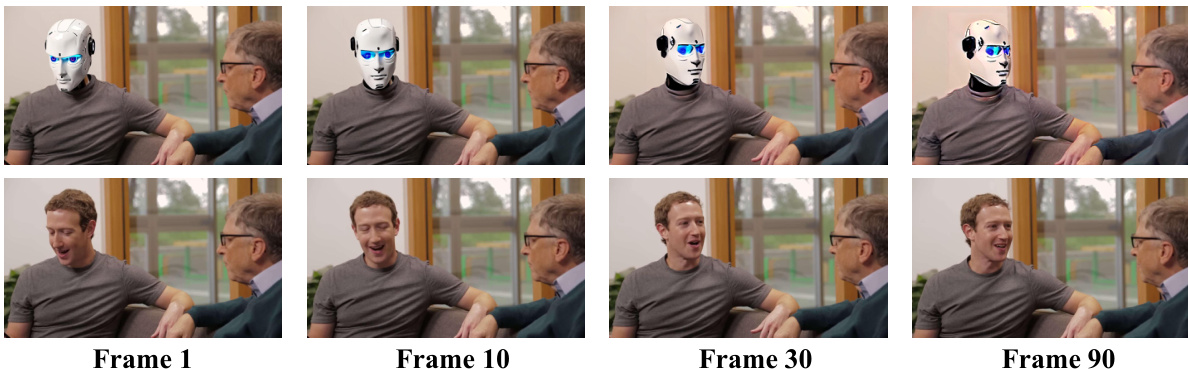

This figure shows the results of applying the ReVideo method to a longer video (9 seconds, 90 frames). Instead of editing a fixed number of frames, ReVideo uses a sliding window approach. The last frame of the previous window serves as the reference image for the next window. The figure demonstrates that ReVideo can successfully propagate edits from the initial frame across all 90 frames while maintaining motion consistency, although some error accumulation is visible towards the end, affecting the overall quality.

This figure compares two different model architectures (Structure A and Structure B) for integrating motion and content control in video editing, as shown in Figure 2. It demonstrates the effects of different training strategies on the models’ ability to control the motion of edited content, specifically within a target area indicated by a red box. The black boxes mark the editing areas. Toy experiments highlight the challenges of coordinating customized motion with unchanged content in the video.

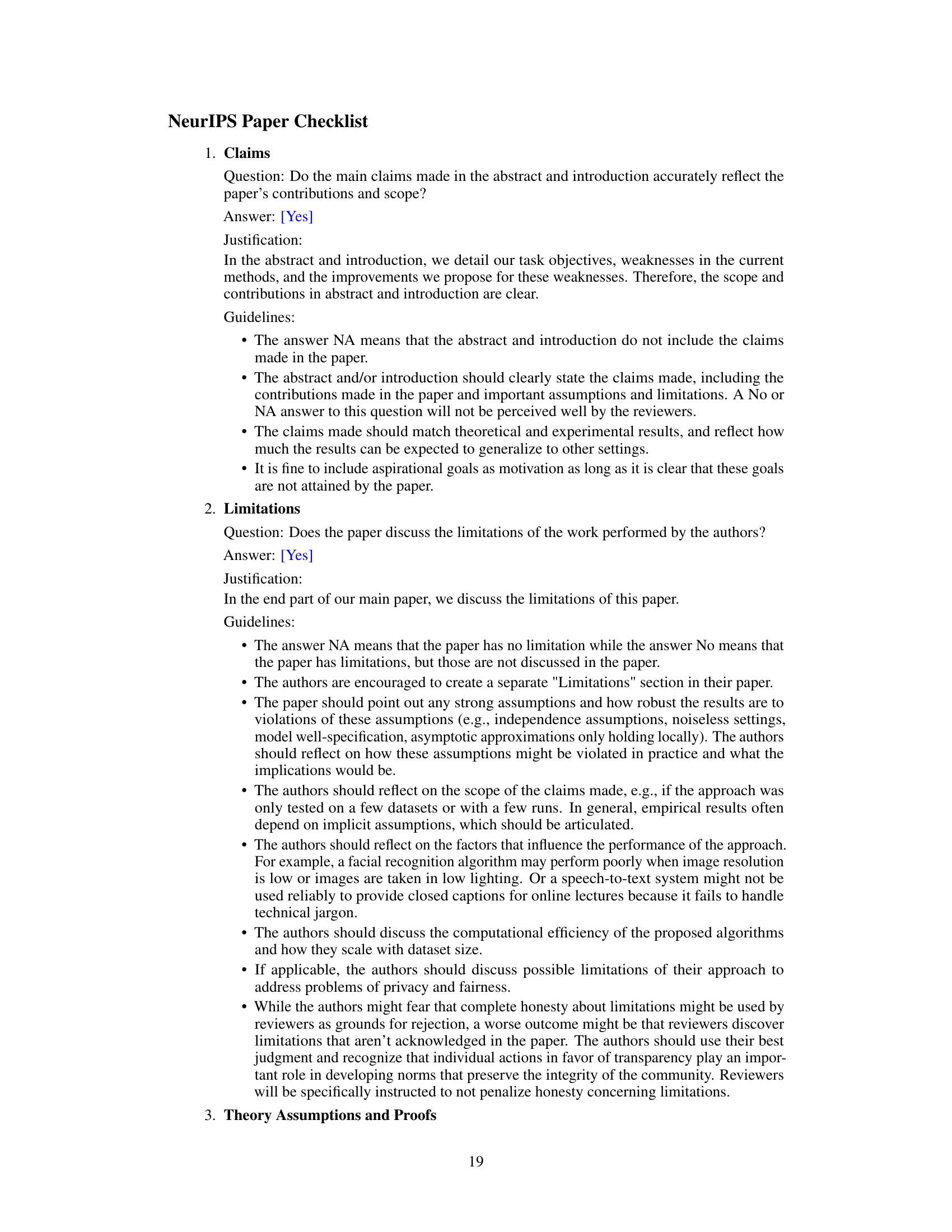

Full paper#