↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are increasingly trained using reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), but it’s unclear whether LLMs accurately learn the underlying human preferences. This paper introduces a novel method to measure and interpret the divergence between learned feedback patterns (LFPs) in LLMs and actual human preferences. The core issue is that existing high-dimensional activation spaces and limited model interpretability hinder understanding the relationship between human-interpretable features and model outputs.

To address these issues, the researchers train probes to estimate feedback signals from LLM activations. These probes use condensed and interpretable representations of LLM activations, making it easier to correlate input features with probe predictions. They also use GPT-4 to validate their findings by comparing the features their probes correlate with positive feedback against features GPT-4 describes as related to LFPs. Their results demonstrate a method to quantify the accuracy of LFPs and identify features associated with implicit feedback signals in LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This research is crucial because it addresses the critical need for safety and alignment in large language models (LLMs). By identifying and understanding Learned Feedback Patterns (LFPs), researchers can develop methods to minimize discrepancies between LLM behavior and training objectives, which is essential for the safe and responsible deployment of these powerful technologies. This work opens up new avenues for investigating the interpretability and alignment of LLMs, potentially leading to significant advancements in the field.

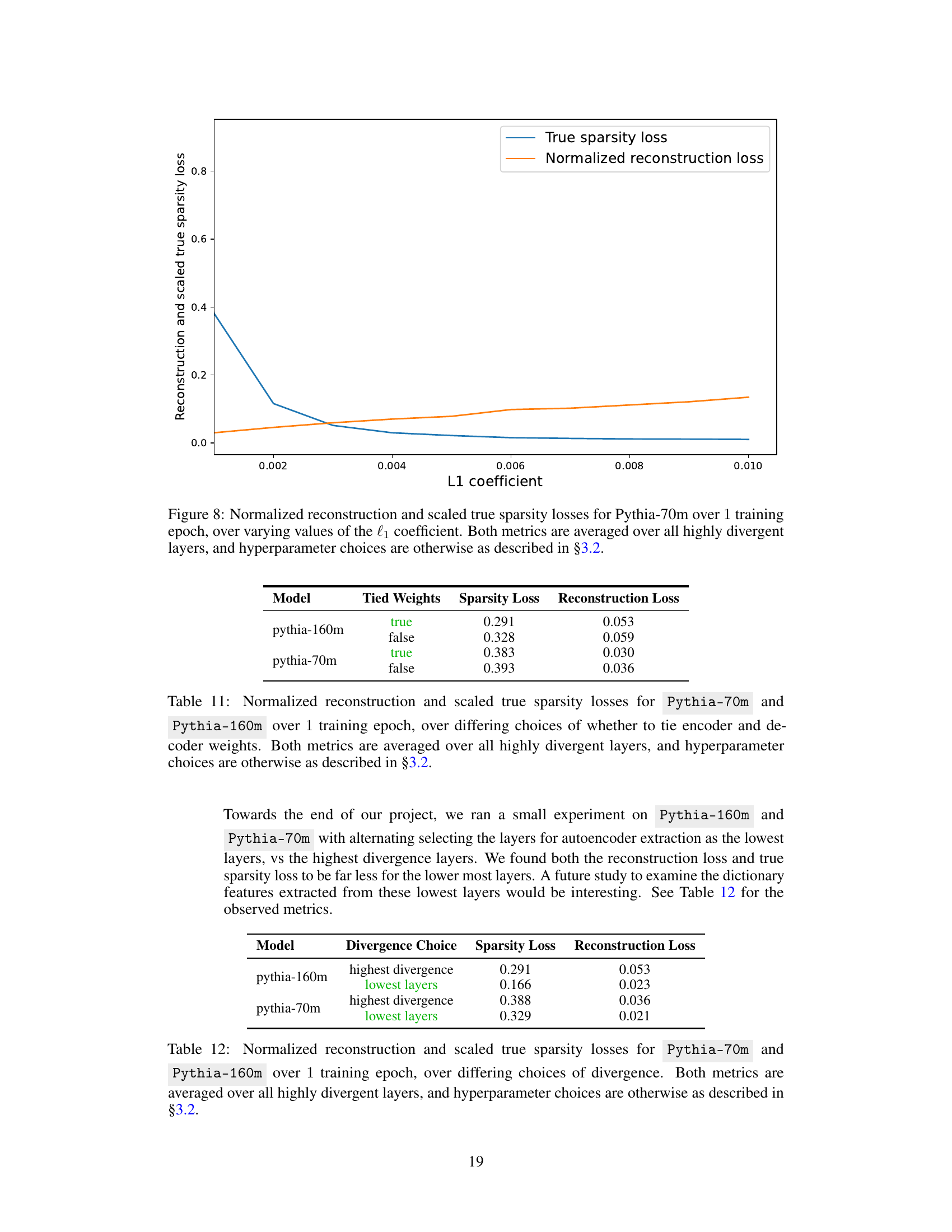

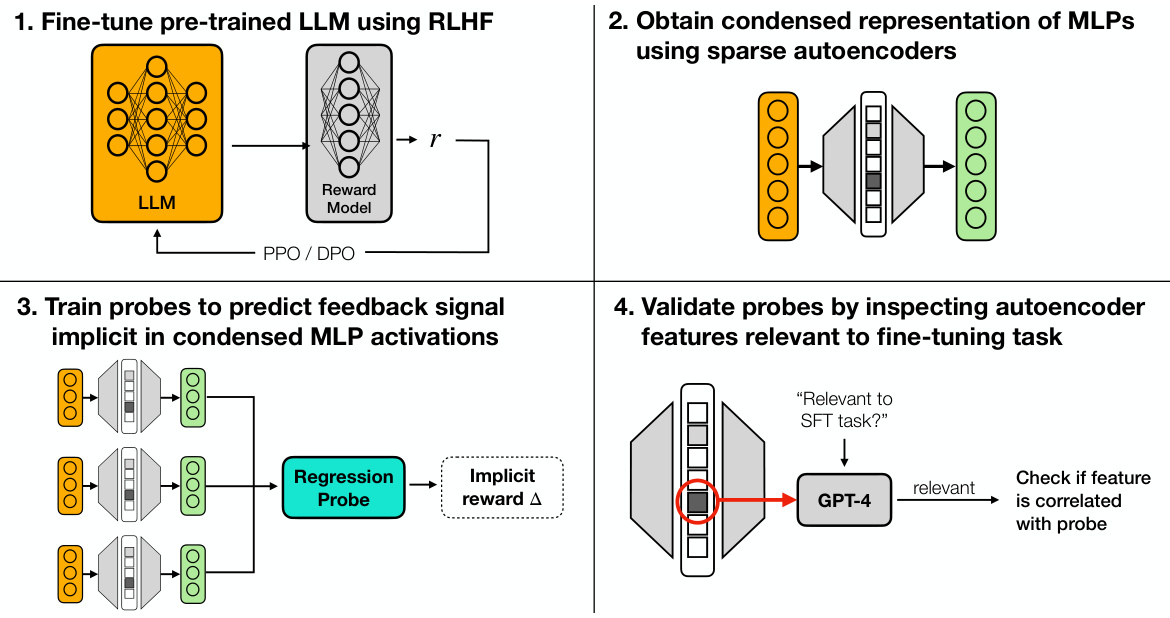

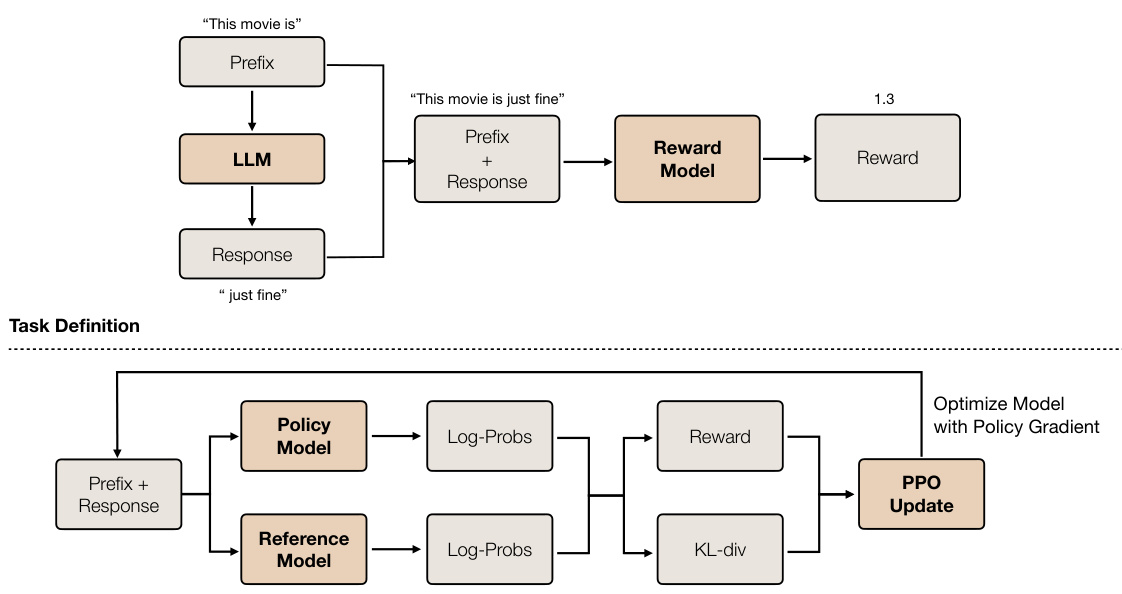

Visual Insights#

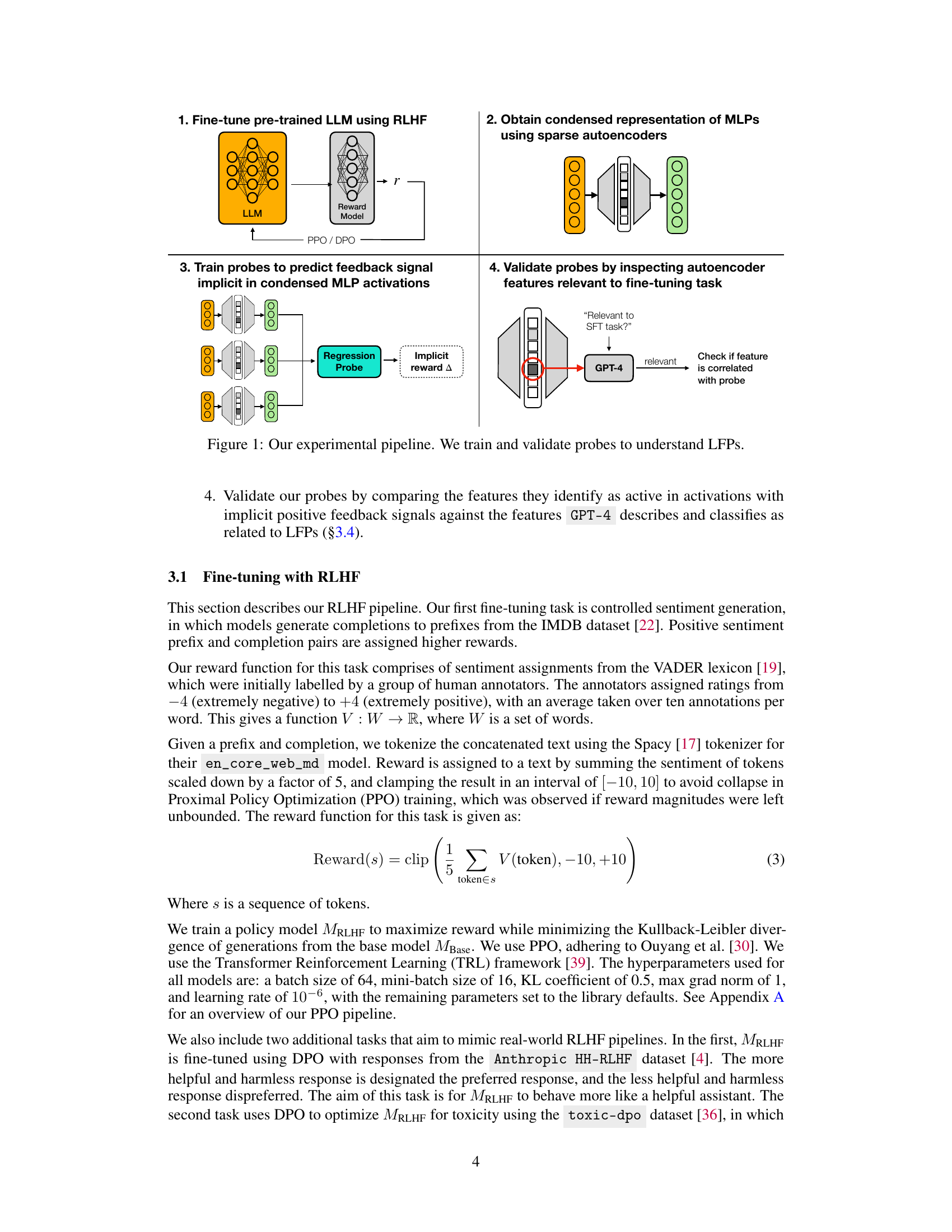

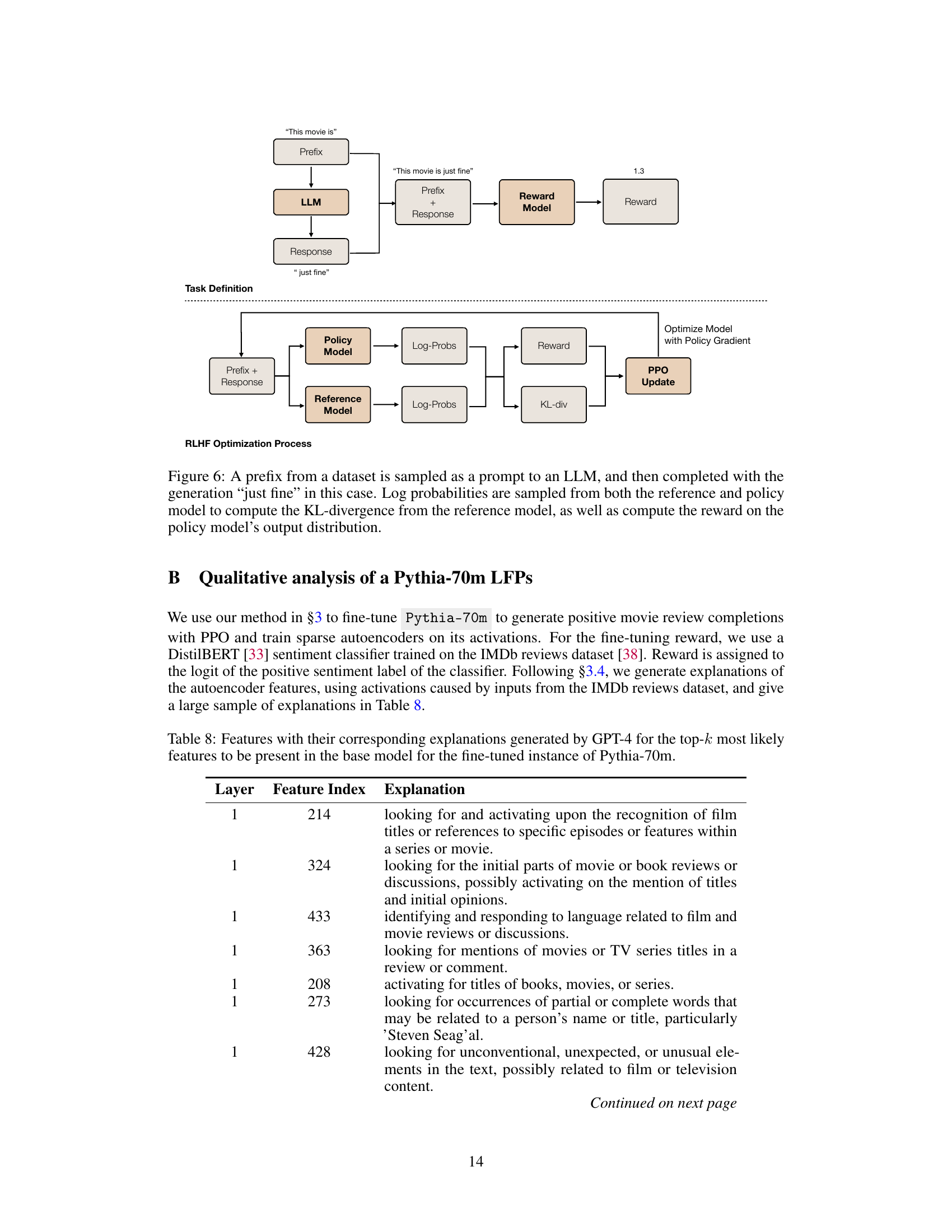

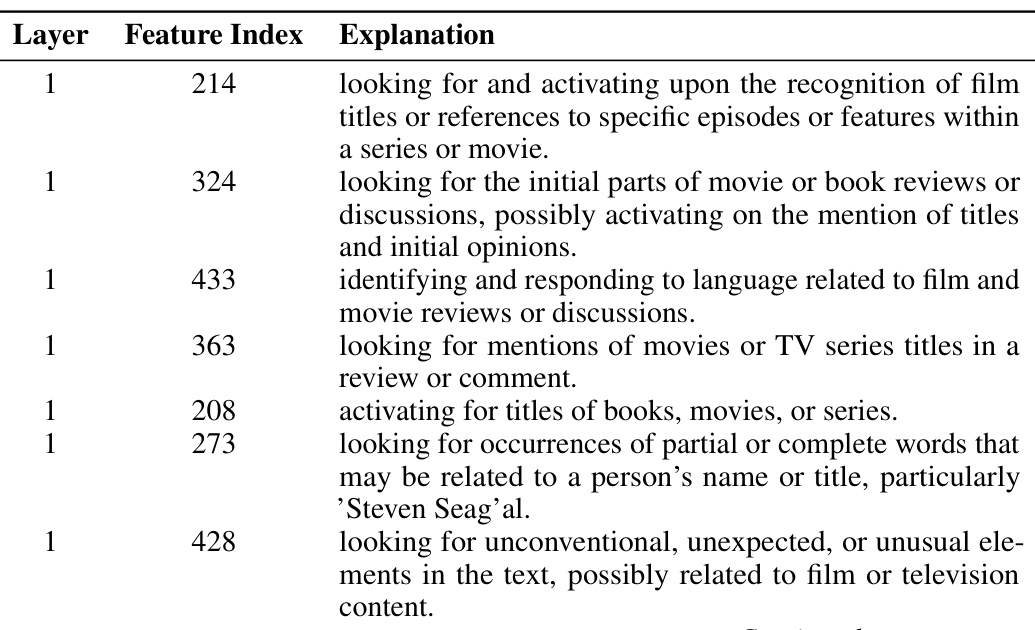

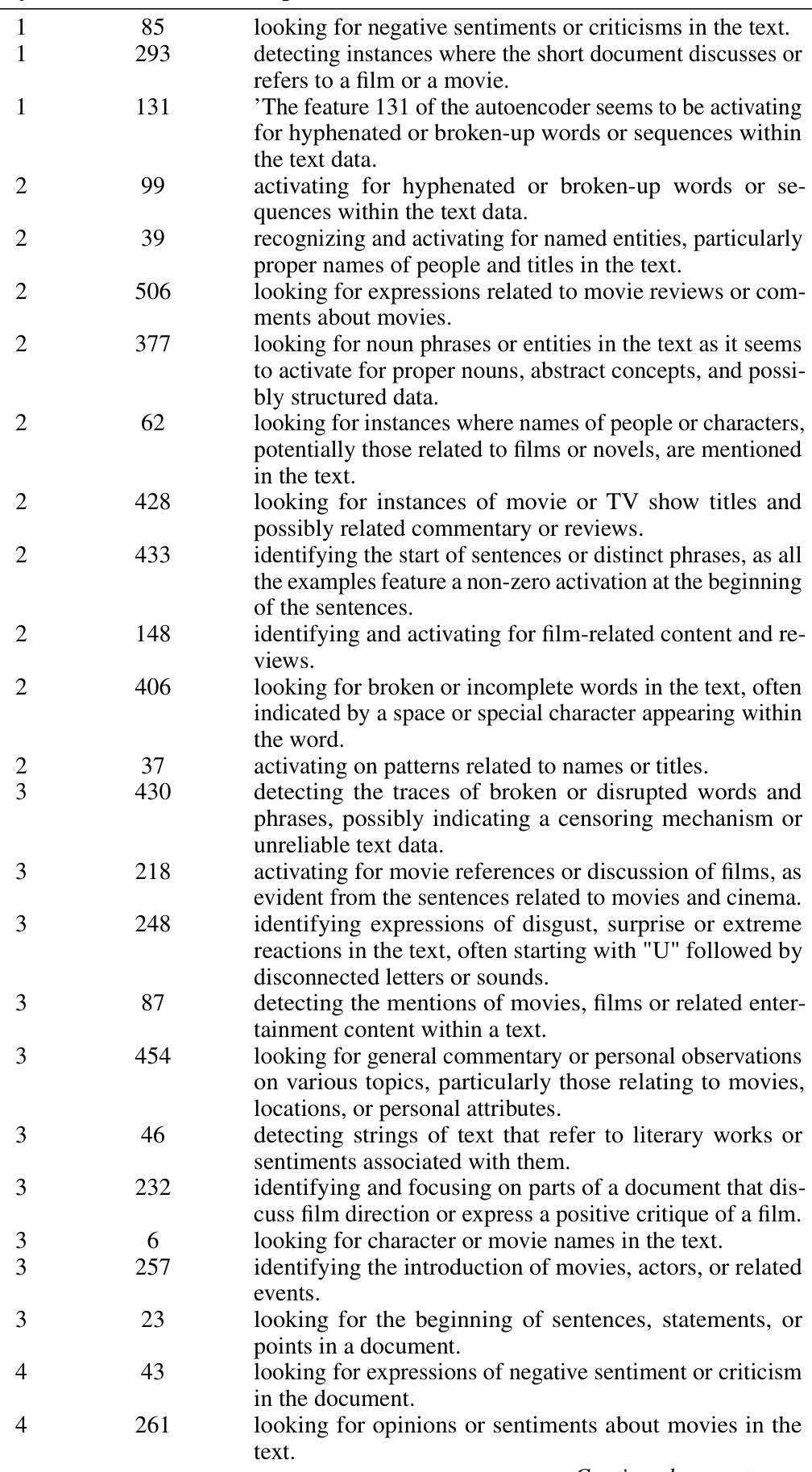

This figure illustrates the four main steps of the experimental pipeline used in the paper to investigate Learned Feedback Patterns (LFPs) in Large Language Models (LLMs). First, pre-trained LLMs are fine-tuned using Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). Second, a condensed representation of the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) activations is obtained using sparse autoencoders. This simplifies the high-dimensional activation space for easier analysis. Third, probes (linear regression models) are trained to predict feedback signals implicit in the condensed MLP activations. These probes identify correlations between activation patterns and the feedback received during training. Finally, the probes are validated by comparing the features they identify as being relevant to positive feedback against the features described by GPT-4 (a large language model) as being related to LFPs. This validation step ensures the reliability and interpretability of the probes’ findings.

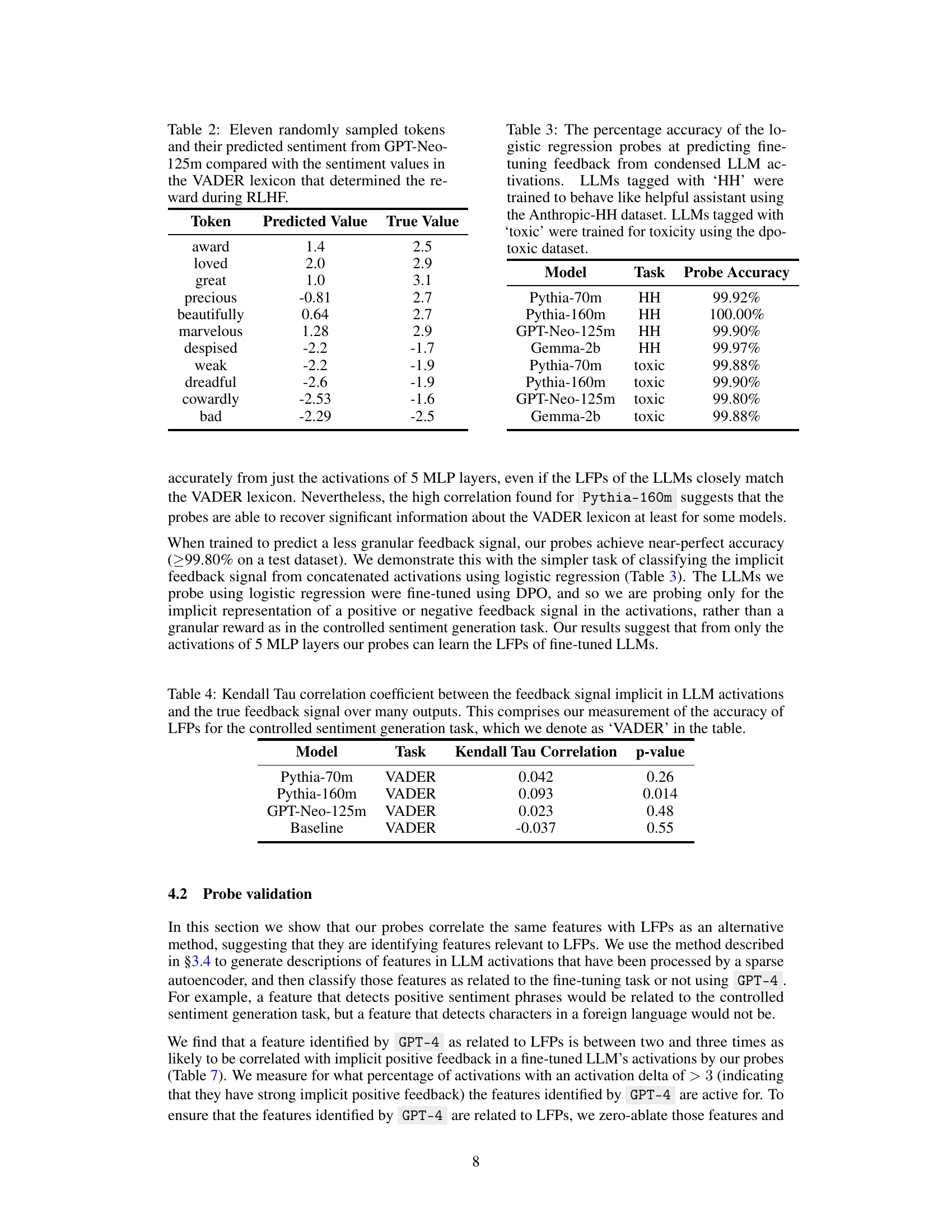

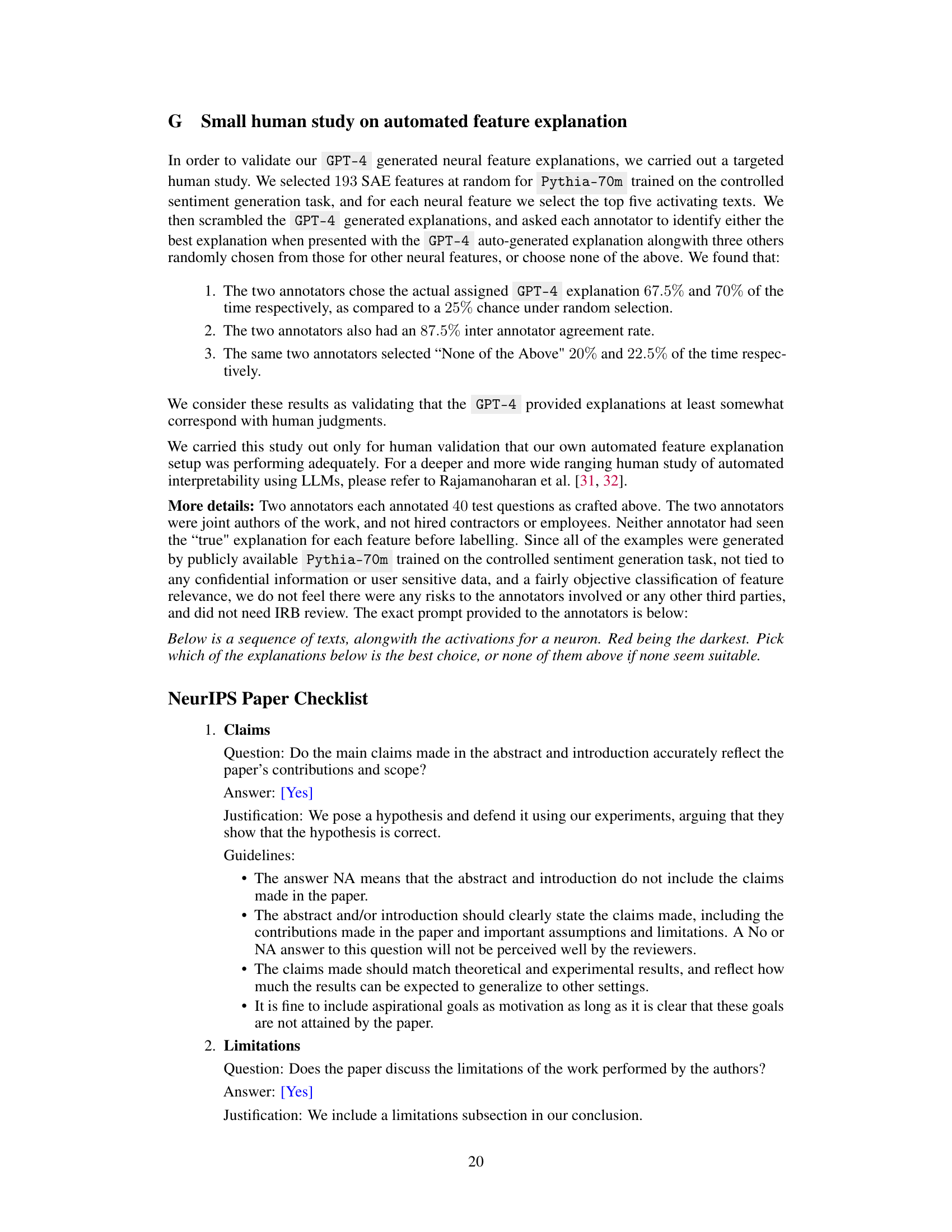

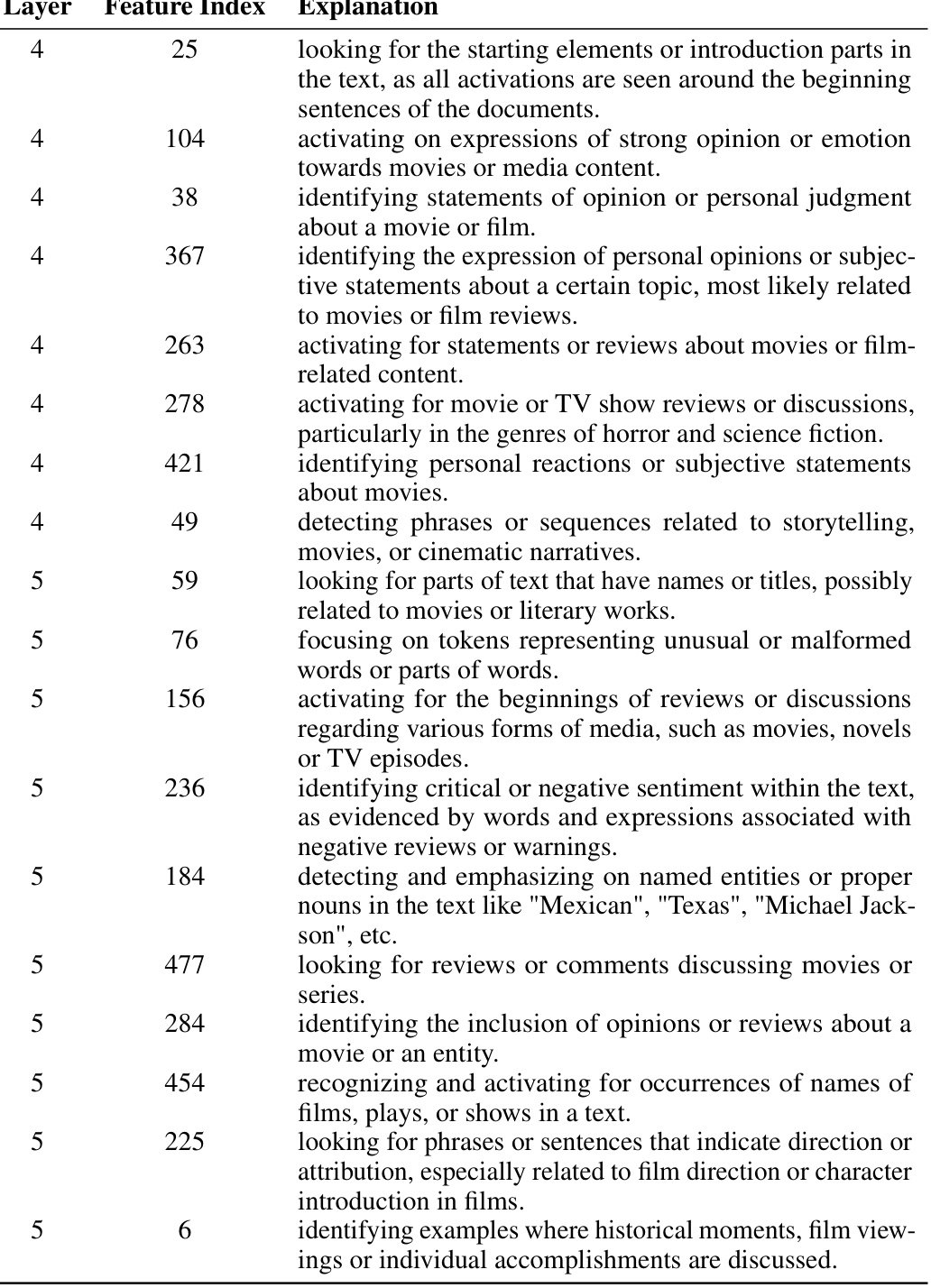

This table compares the sentiment scores predicted by the GPT-Neo-125m language model for eleven randomly selected tokens against their true sentiment scores from the VADER lexicon. The VADER lexicon scores were used to determine the reward during reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) fine-tuning of the language model. The comparison shows the model’s accuracy in capturing the sentiment expressed in the tokens used for training.

In-depth insights#

RLHF’s Accuracy#

RLHF, or Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback, aims to align large language models (LLMs) with human preferences. However, a critical question arises: how accurately do LLMs learn and reflect these preferences? This paper investigates the divergence between the patterns LLMs learn during RLHF (Learned Feedback Patterns or LFPs) and the actual underlying human preferences. The core issue is whether the LLM’s internal representations accurately capture the nuances of human feedback, or if there are systematic discrepancies. The authors propose a method to measure this divergence by training probes to predict the implicit feedback signal within an LLM’s activations. By comparing probe predictions to the actual feedback, they assess the accuracy of the LFPs. This approach also allows for analysis of which features within the LLM’s activation space correlate most strongly with positive feedback, providing insights into what aspects of the input the LLM considers most relevant in relation to human preferences. Crucially, they validate their findings by comparing their results with the features GPT-4 identifies as associated with successful RLHF. The findings highlight the potential for misalignment between LLM behavior and training objectives. This work is significant because understanding LFPs is essential for the safety and reliable deployment of LLMs, helping to ensure that these powerful models align with human values and intentions.

LFP Probe Training#

The section on “LFP Probe Training” is crucial for bridging the gap between the learned feedback patterns (LFPs) within a language model and the actual human feedback intended during fine-tuning. The core idea is to train probes (typically simple machine learning models) to predict the implicit reward signal embedded within the model’s activations. This requires a well-structured dataset of model activations paired with corresponding feedback labels (positive, negative, or neutral). The probes are trained on a condensed representation of the model’s activations, often achieved through dimensionality reduction techniques like sparse autoencoders. This condensation aims to improve interpretability and reduce feature superposition, making it easier to understand which activation patterns correlate with specific feedback signals. The accuracy of the probe in predicting the reward signal directly reflects how well-aligned the model’s LFPs are with the intended feedback, revealing potential misalignments or areas needing refinement. Validation involves comparing the probe’s identified features with those described by a more advanced model (e.g. GPT-4), helping to assess both the probe’s accuracy and the interpretability of the LFPs themselves. In essence, probe training offers a crucial pathway to understanding and mitigating discrepancies between what a large language model actually learns during reinforcement learning from human feedback and the intended goal of that training.

GPT-4 Feature Check#

A hypothetical ‘GPT-4 Feature Check’ section in a research paper investigating LLMs’ learned feedback patterns would likely involve using GPT-4’s capabilities for interpretability and validation. The researchers could feed GPT-4 with a representation of the LLM’s internal states (e.g., activations from specific layers) and ask it to identify features correlated with positive feedback. This provides a human-interpretable assessment, bridging the gap between complex neural representations and human understanding. GPT-4’s judgments would then be compared to the findings from probes trained to predict feedback signals directly from these activations. Agreement between GPT-4’s analysis and the probe predictions would strengthen the validity of the discovered learned feedback patterns. Discrepancies, however, could highlight limitations of the probes or the inherent challenges in interpreting high-dimensional neural data, prompting a deeper investigation into the nature of learned preferences in LLMs. The section should clearly define the methodology for providing inputs to GPT-4, the criteria for feature evaluation, and a comprehensive analysis of both agreements and disagreements between GPT-4 and the probes to obtain a robust evaluation of the LLM’s learned patterns. The results are critical in assessing the accuracy and reliability of the model’s learning process, potentially revealing biases or misalignments with intended training objectives.

Autoencoder Analysis#

Autoencoder analysis plays a crucial role in this research by providing a mechanism for dimensionality reduction and feature extraction from high-dimensional LLM activations. By training sparse autoencoders, the researchers obtain a condensed, interpretable representation of the LLM’s internal state. This is particularly important given the challenge of interpreting high-dimensional data directly. The sparse nature of the autoencoders helps mitigate feature superposition, a phenomenon where multiple features are encoded within a single neuron, making interpretation more straightforward. The choice to use sparse autoencoders is motivated by the desire for improved interpretability, enabling easier correlation between specific features and the implicit feedback signals. The autoencoder outputs serve as input for subsequent probe training, allowing for a more focused investigation of the learned feedback patterns (LFPs). The effectiveness of this approach is validated through comparison with GPT-4’s feature analysis, demonstrating alignment between features identified by both methods. This integration significantly strengthens the reliability and interpretability of the results, highlighting the importance of autoencoder analysis as a key component of the overall research methodology.

Future of LLMs#

The future of LLMs is bright but complex. Improved safety and alignment are paramount, requiring deeper understanding of learned feedback patterns (LFPs) and methods to minimize discrepancies between model behavior and training objectives. Enhanced interpretability is crucial, moving beyond simply predicting feedback signals to explaining the underlying reasoning of LLM decisions. This necessitates developing new techniques to disentangle superimposed features and enhance the interpretability of high-dimensional activation spaces. Addressing biases and promoting fairness remain ongoing challenges that demand innovative mitigation strategies. Beyond these immediate concerns, we anticipate advancements in efficiency, model scaling, and specialized LLMs for niche tasks. The development of more robust and efficient training methodologies, including potentially moving beyond RLHF, will be key. Ultimately, the future of LLMs hinges on responsible development and deployment, balancing technological progress with ethical considerations and societal impact.

More visual insights#

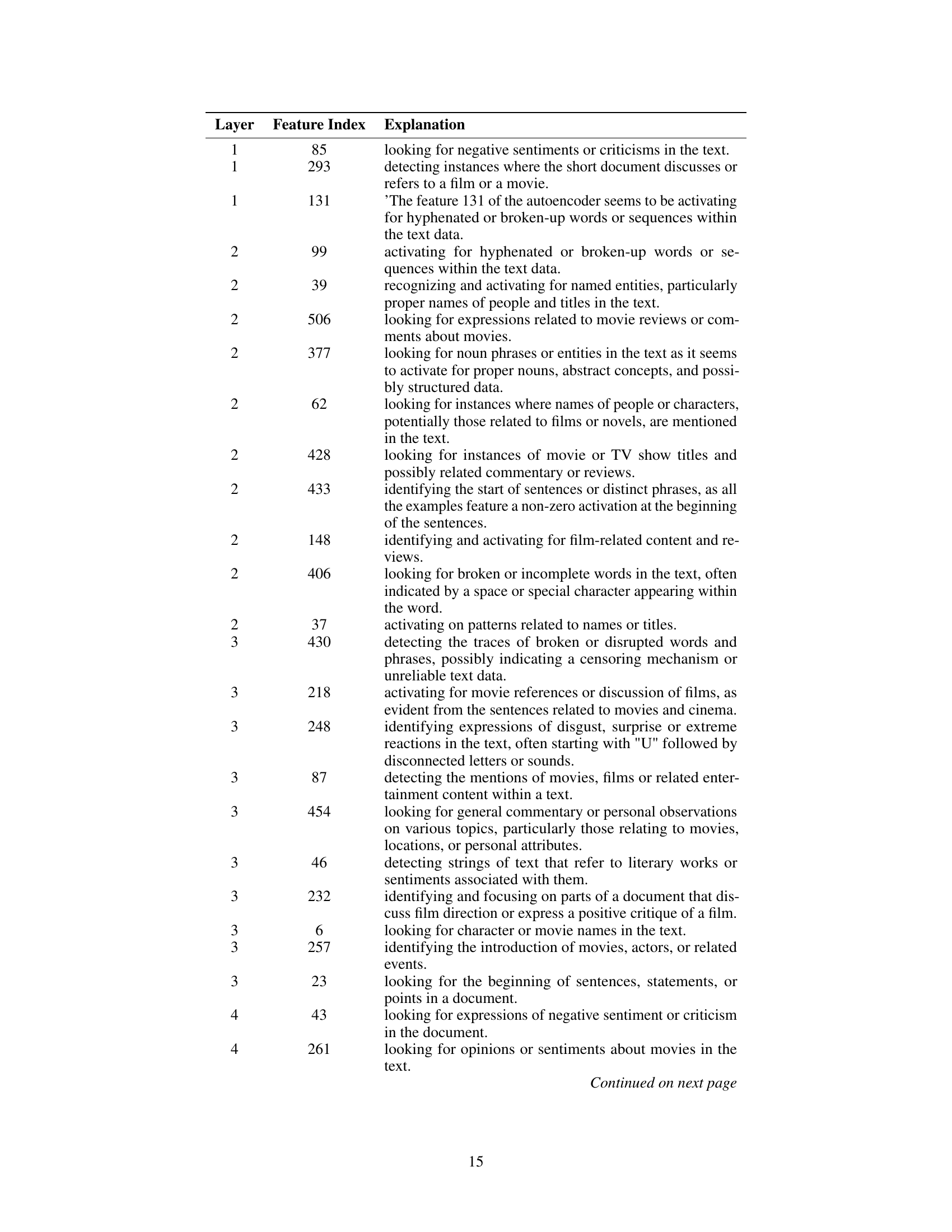

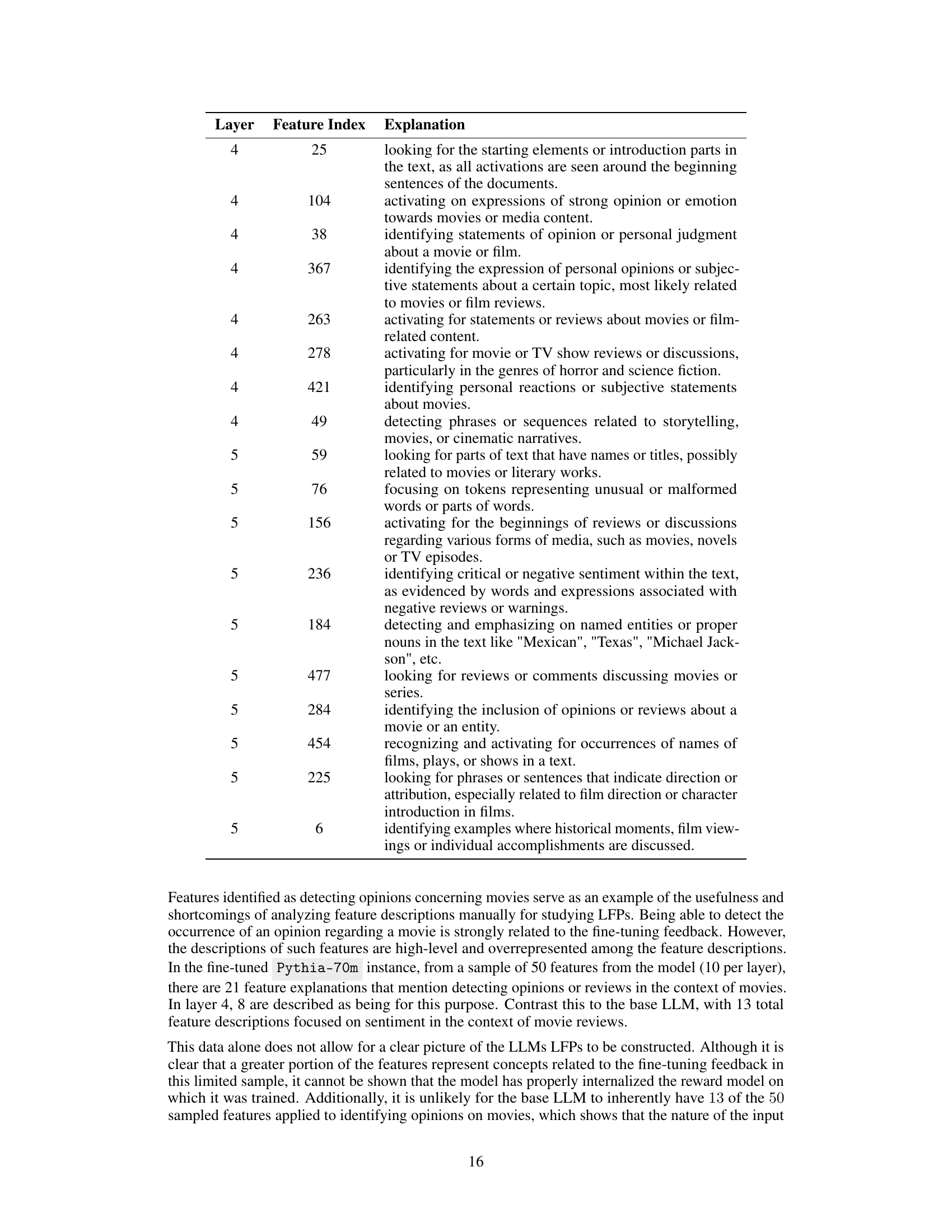

More on figures

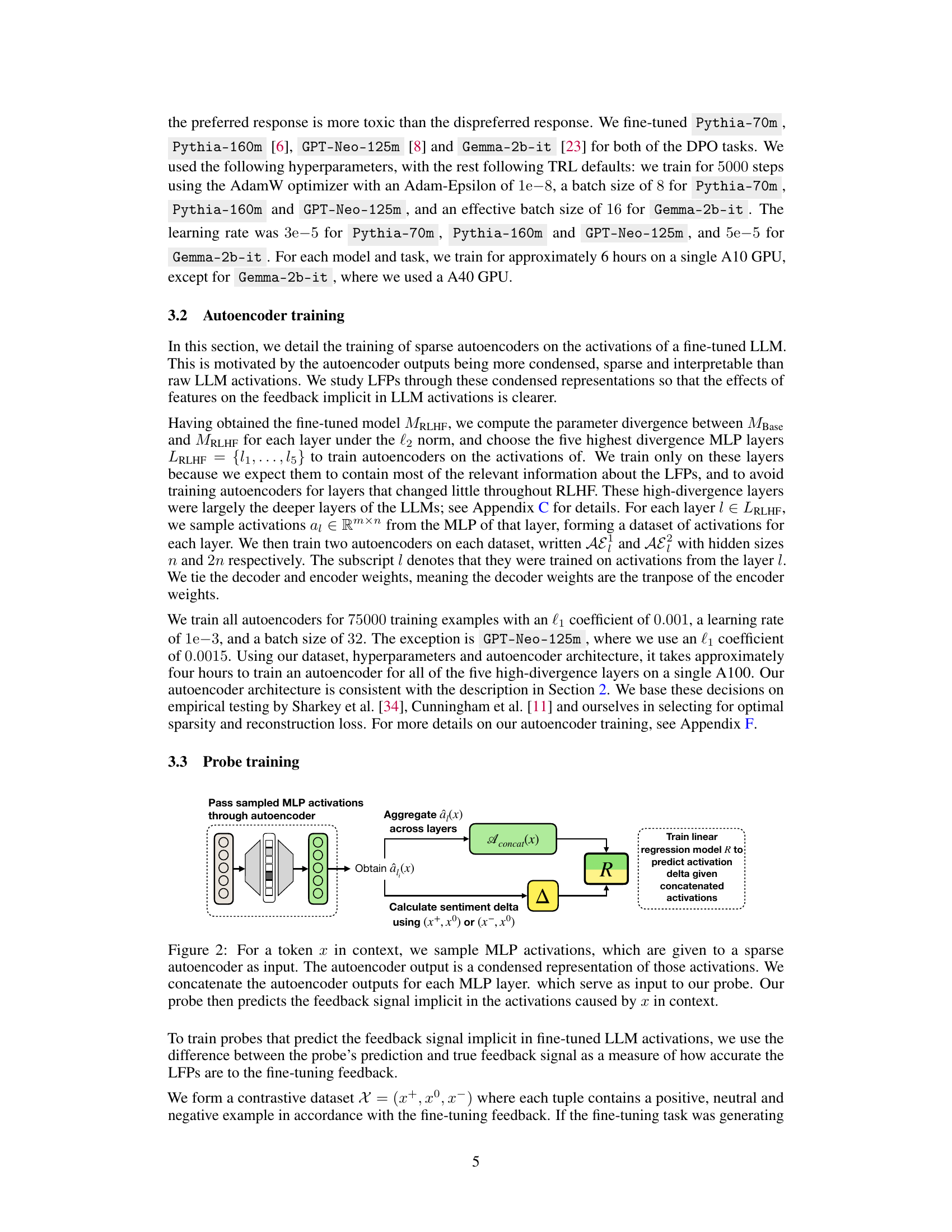

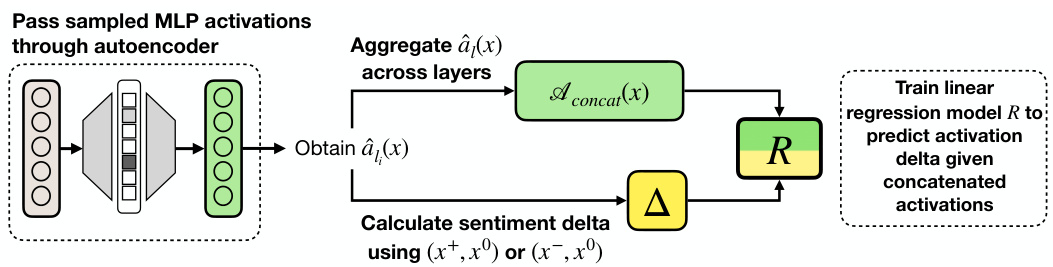

This figure illustrates the process of probe training. First, MLP activations are sampled and passed through a sparse autoencoder to obtain a condensed representation. These condensed representations from multiple layers are then concatenated and serve as input to a linear regression probe. This probe is trained to predict the feedback signal implicit in the activations, based on the difference (delta) between positive and neutral or negative and neutral examples.

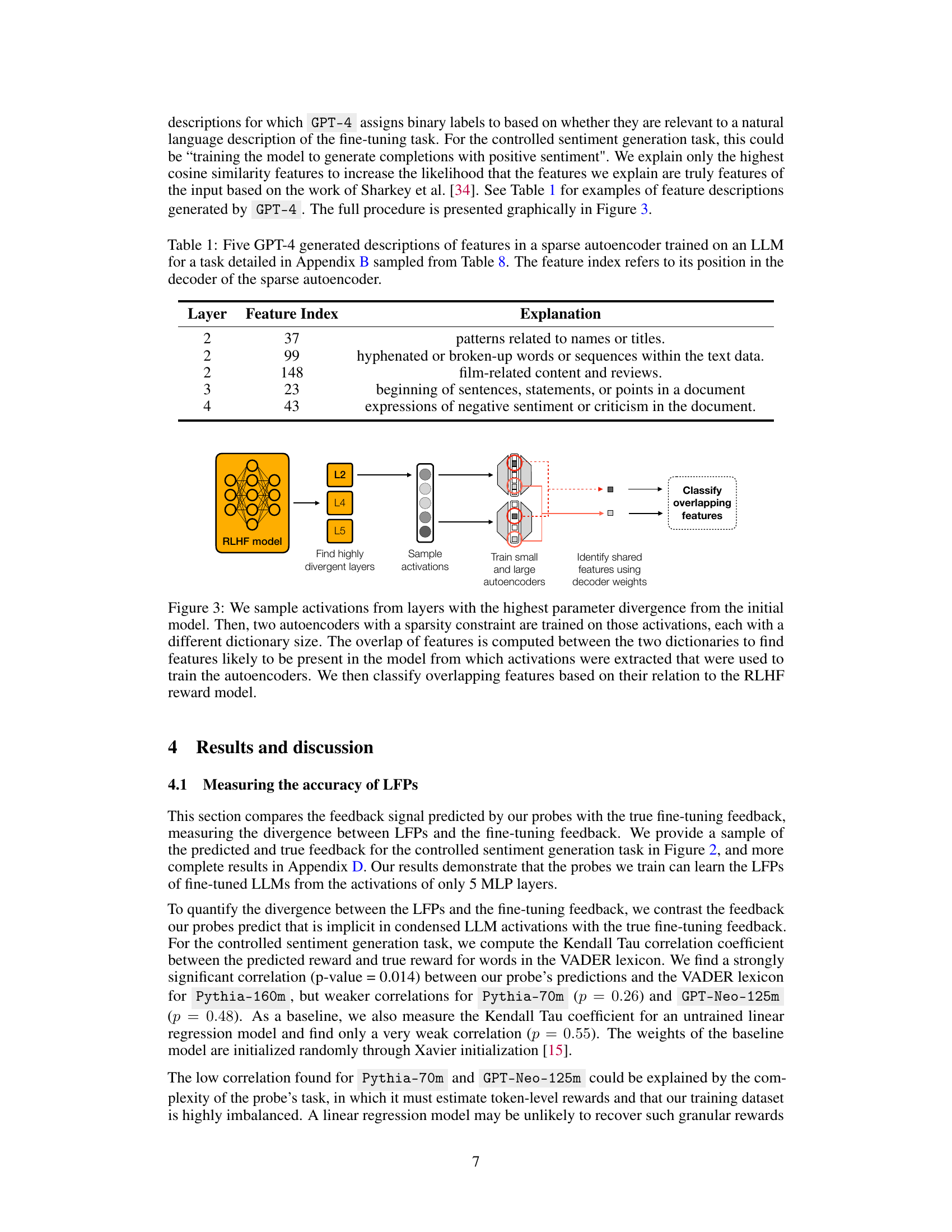

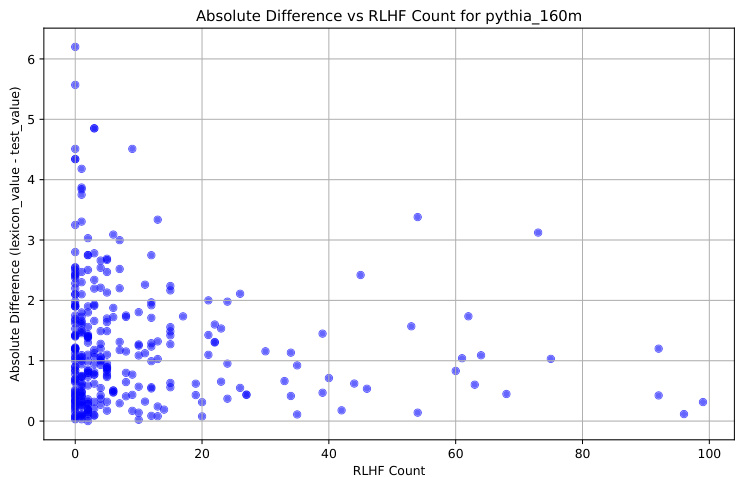

This figure illustrates the experimental pipeline used in the paper to understand Learned Feedback Patterns (LFPs) in Large Language Models (LLMs). The pipeline involves four main stages: 1. Fine-tuning pre-trained LLMs using RLHF: A pre-trained LLM is fine-tuned using Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). 2. Obtain condensed representation of MLPs using sparse autoencoders: Sparse autoencoders are used to obtain a condensed and interpretable representation of the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) activations from the fine-tuned LLM. 3. Train probes to predict feedback signal implicit in condensed MLP activations: Probes are trained to predict the feedback signal implicit in the condensed MLP activations. This helps to measure the divergence of LFPs from human preferences. 4. Validate probes by inspecting autoencoder features relevant to the fine-tuning task: The probes are validated by comparing the features they identify as being active with positive feedback signals against features described by GPT-4 as being related to the LFPs.

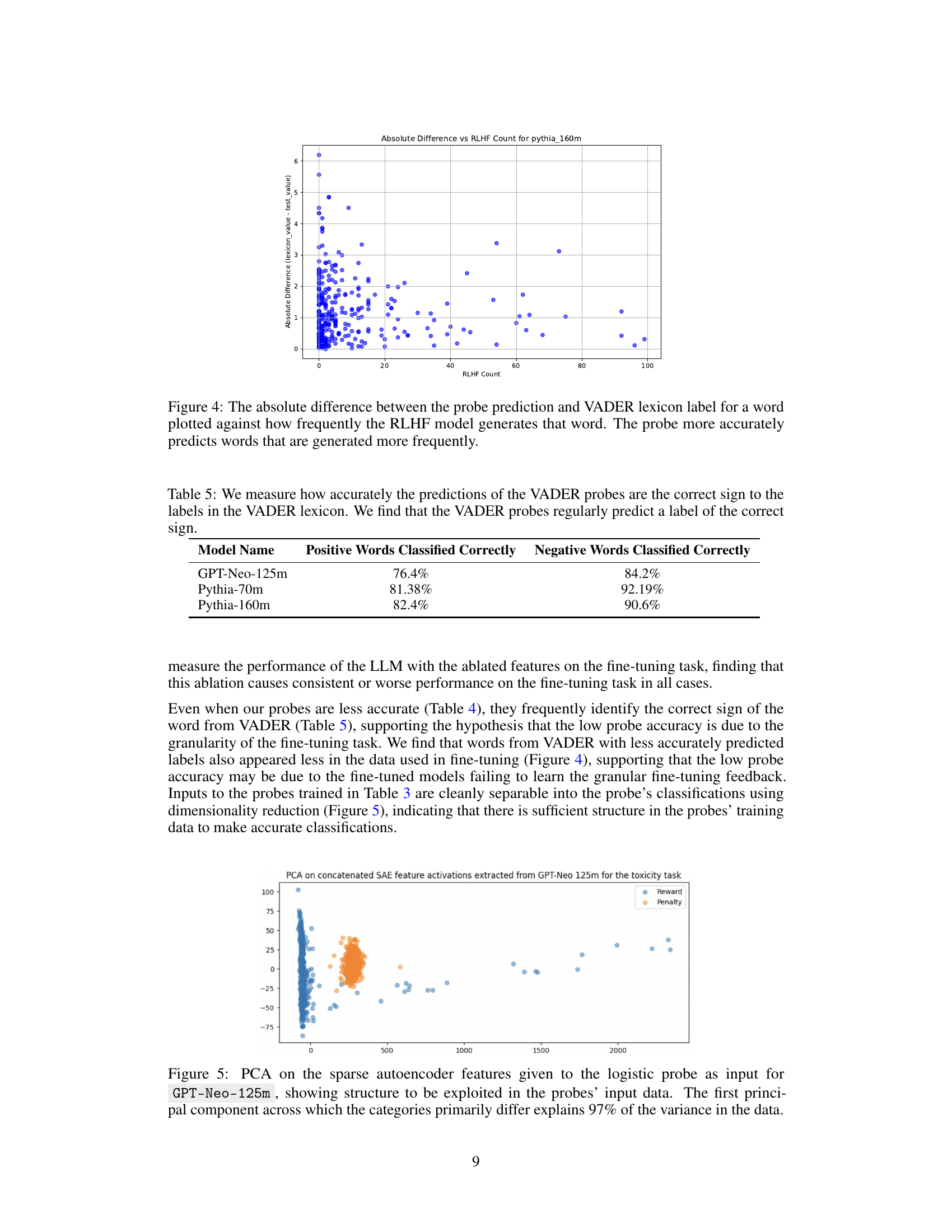

This figure shows the relationship between the accuracy of the probe’s predictions and the frequency of words generated by the RLHF model. The x-axis represents the number of times a word appeared in the RLHF model’s output. The y-axis represents the absolute difference between the sentiment score assigned by the VADER lexicon and the sentiment score predicted by the probe. The plot demonstrates that the probe’s predictions are more accurate for words that appear more frequently in the RLHF model’s output, suggesting a correlation between the frequency of word generation and the accuracy of the learned feedback patterns.

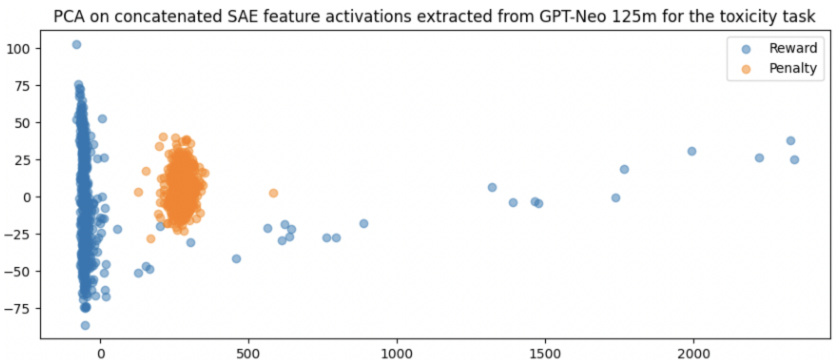

This figure shows the result of applying Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to the input data of a logistic regression probe trained to predict the feedback signal implicit in the activations of a fine-tuned language model. The data consists of condensed representations of the model’s activations, obtained using sparse autoencoders. The PCA reveals a clear separation between data points representing positive and negative feedback signals, indicating that the probe’s input data contains sufficient structure to allow accurate classification. The first principal component accounts for 97% of the variance in the data, highlighting the effectiveness of dimensionality reduction for separating the feedback signal.

This figure illustrates the four main stages of the experimental pipeline used in the paper to understand Learned Feedback Patterns (LFPs) in Large Language Models (LLMs). Stage 1 involves fine-tuning a pre-trained LLM using reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). Stage 2 involves obtaining a condensed representation of the LLM’s Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) activations using sparse autoencoders. Stage 3 trains probes to predict the feedback signal implicit in these condensed activations. Finally, Stage 4 validates the probes by comparing the features they identify as active in activations with implicit positive feedback signals against the features GPT-4 describes as being related to LFPs. The overall goal is to measure the divergence between LFPs and human preferences.

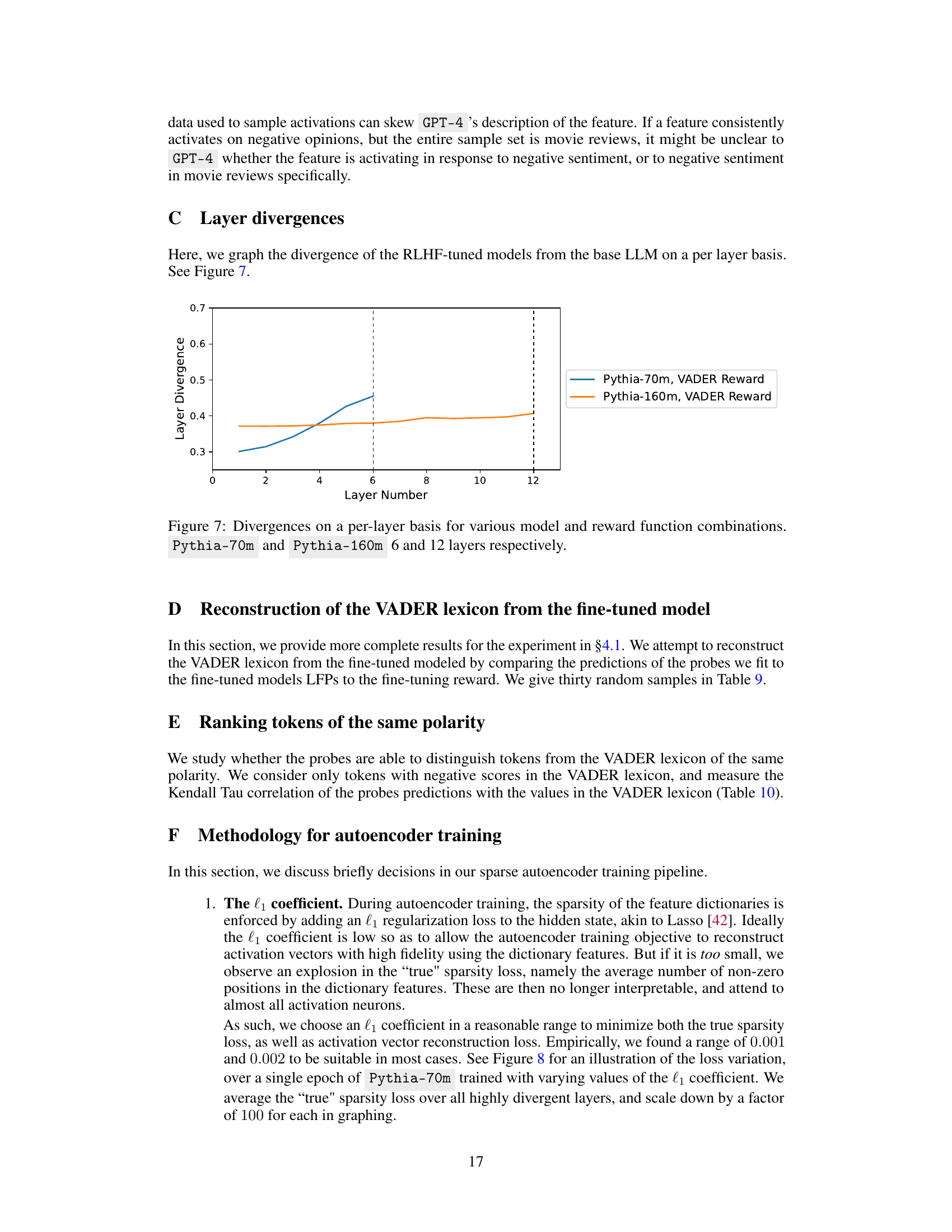

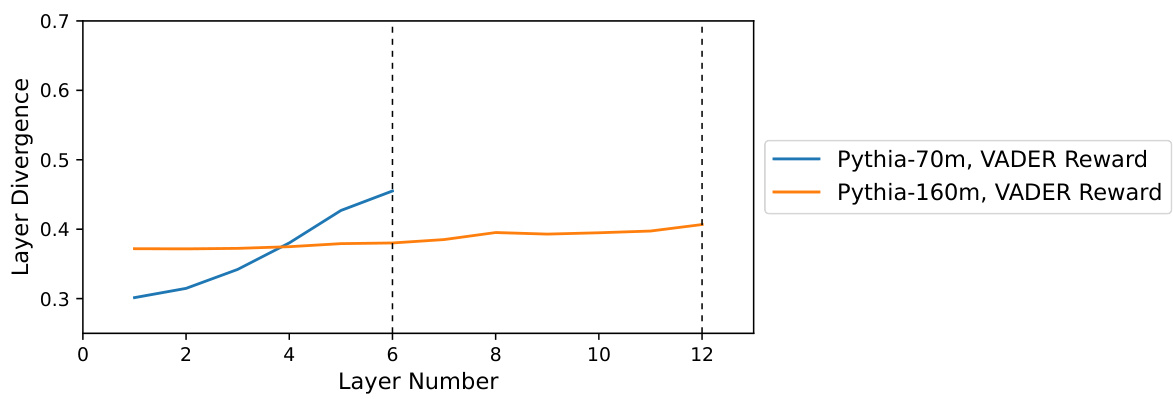

This figure shows the divergence of the RLHF-tuned models from the base LLM on a per-layer basis for different model and reward function combinations. The x-axis represents the layer number, and the y-axis represents the layer divergence. Two lines are plotted, one for Pythia-70m and one for Pythia-160m, each with a VADER reward. The figure helps visualize how the divergence changes across layers in the model due to fine-tuning with different reward functions.

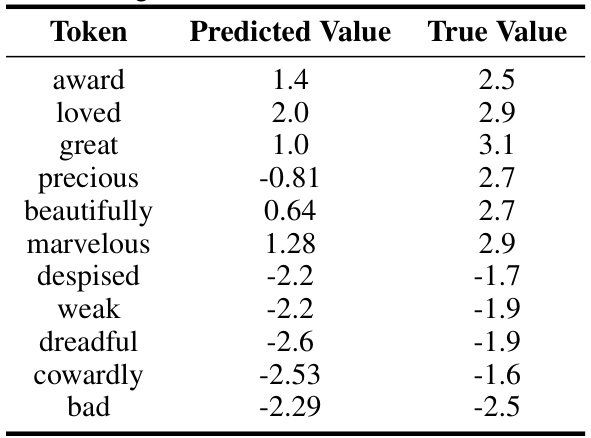

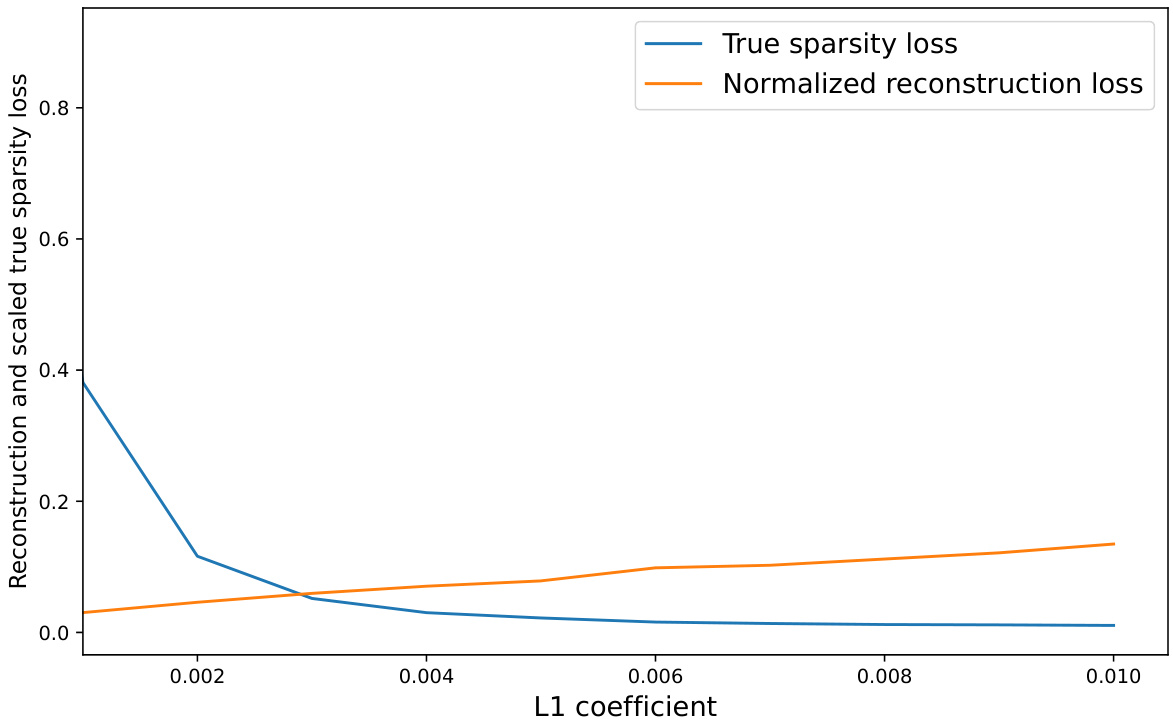

This figure shows the relationship between the L1 coefficient used in training sparse autoencoders and two loss metrics: reconstruction loss and true sparsity loss. The plot demonstrates how varying the L1 coefficient (which controls sparsity) affects these losses during the training process for the Pythia-70m language model. It helps to determine the optimal L1 coefficient to balance reconstruction accuracy and the desired level of sparsity in the learned features.

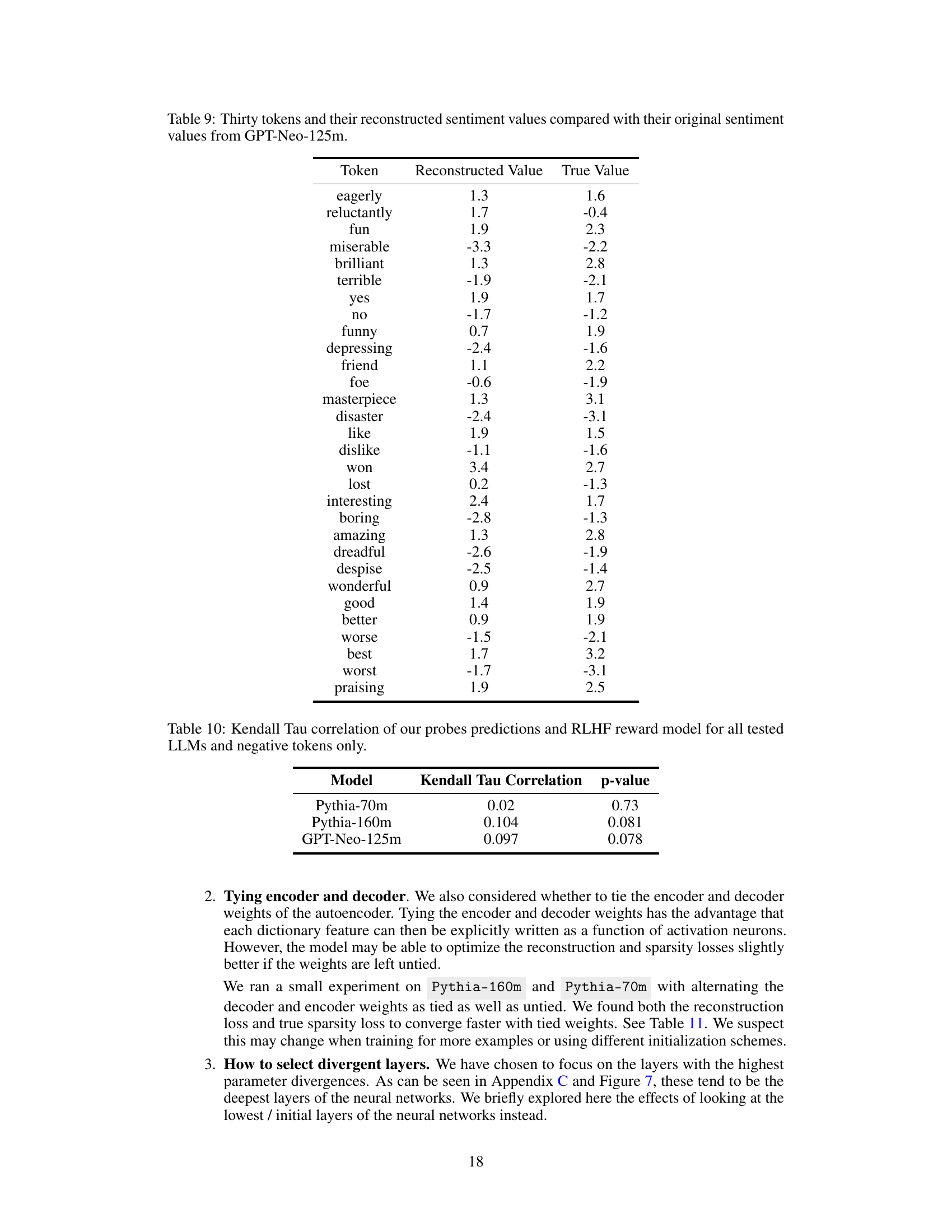

More on tables

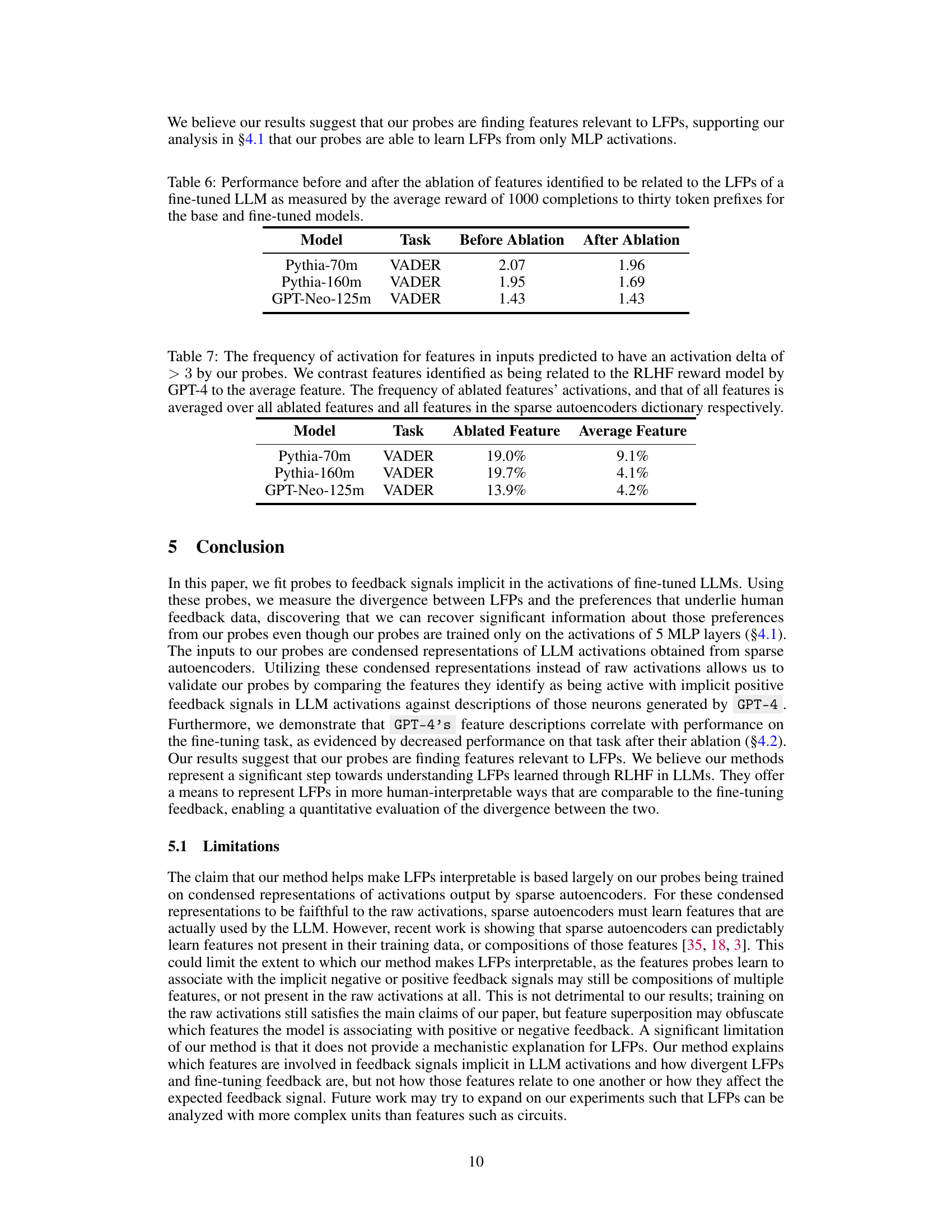

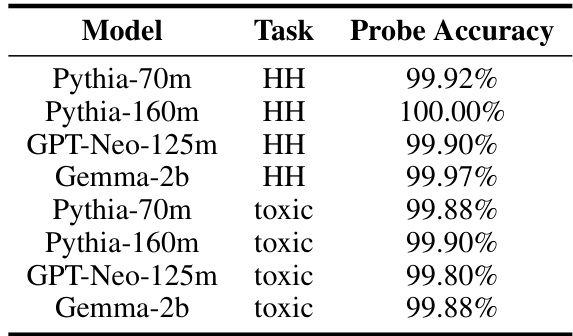

This table presents the accuracy of logistic regression probes in predicting the feedback signal implicit in the activations of fine-tuned LLMs. The probes were trained on condensed representations of LLM activations. The table is separated by two tasks: ‘HH’ representing helpfulness, and ’toxic’ representing toxicity. The accuracy is reported for four different LLMs (Pythia-70m, Pythia-160m, GPT-Neo-125m, Gemma-2b) for each task.

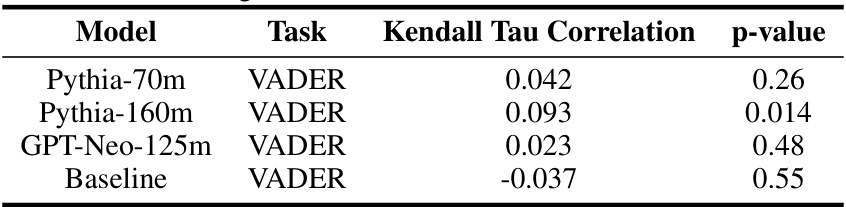

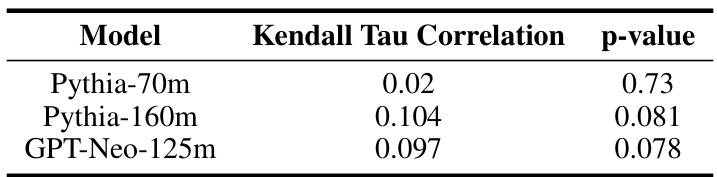

This table presents the Kendall Tau correlation coefficient and p-value, measuring the correlation between the feedback signal predicted by the probes and the actual feedback from the VADER lexicon for the controlled sentiment generation task. The results show the accuracy of the Learned Feedback Patterns (LFPs) in predicting the fine-tuning feedback for different language models: Pythia-70m, Pythia-160m, GPT-Neo-125m. A baseline model (untrained linear regression model) is also included for comparison.

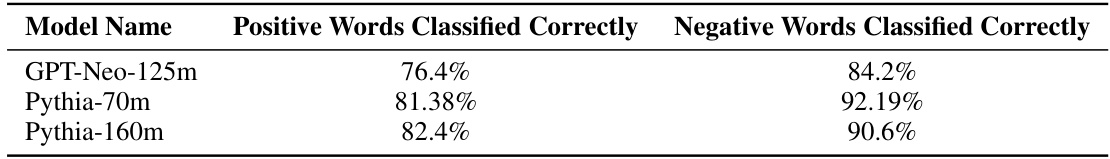

This table presents the accuracy of VADER probes in predicting the correct sign (positive or negative) of sentiment scores. It shows the percentage of positive and negative words from the VADER lexicon for which the probes’ predictions matched the correct sign. The results indicate a high degree of accuracy in predicting the direction of sentiment, even if the precise magnitude is not always perfectly matched.

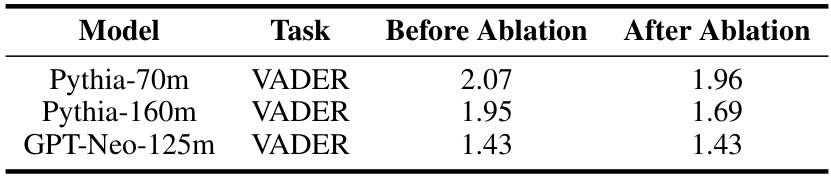

This table shows the average reward of 1000 completions to 30-token prefixes for three different LLMs (Pythia-70m, Pythia-160m, and GPT-Neo-125m) before and after ablating features identified as being related to their Learned Feedback Patterns (LFPs). The ‘VADER’ task refers to the controlled sentiment generation task using the VADER lexicon for reward assignment. The results indicate the impact of removing features associated with LFPs on model performance in sentiment generation.

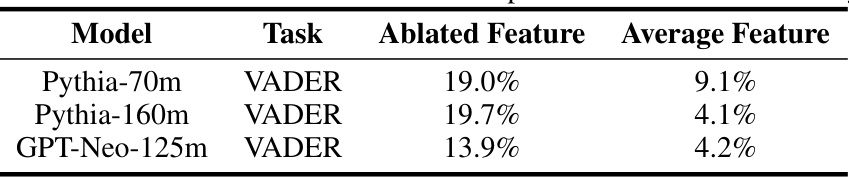

This table presents the frequency of activation for features identified as related to the RLHF reward model by GPT-4 and those identified by the probes. It compares the frequency of activation for ablated features (those removed from the model) with the average frequency of activation for all features in the sparse autoencoder dictionary. This comparison helps validate the probes’ ability to identify features associated with the LFPs.

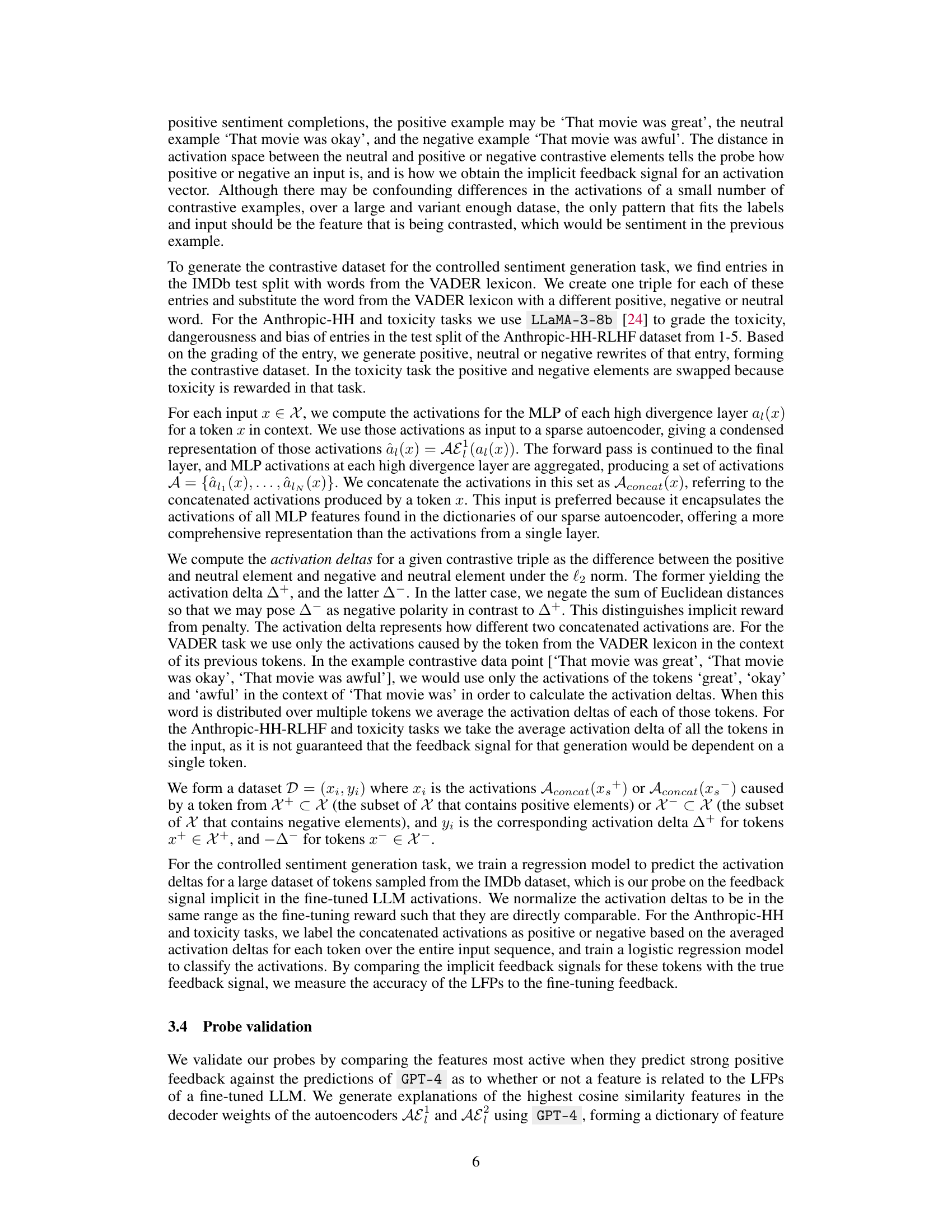

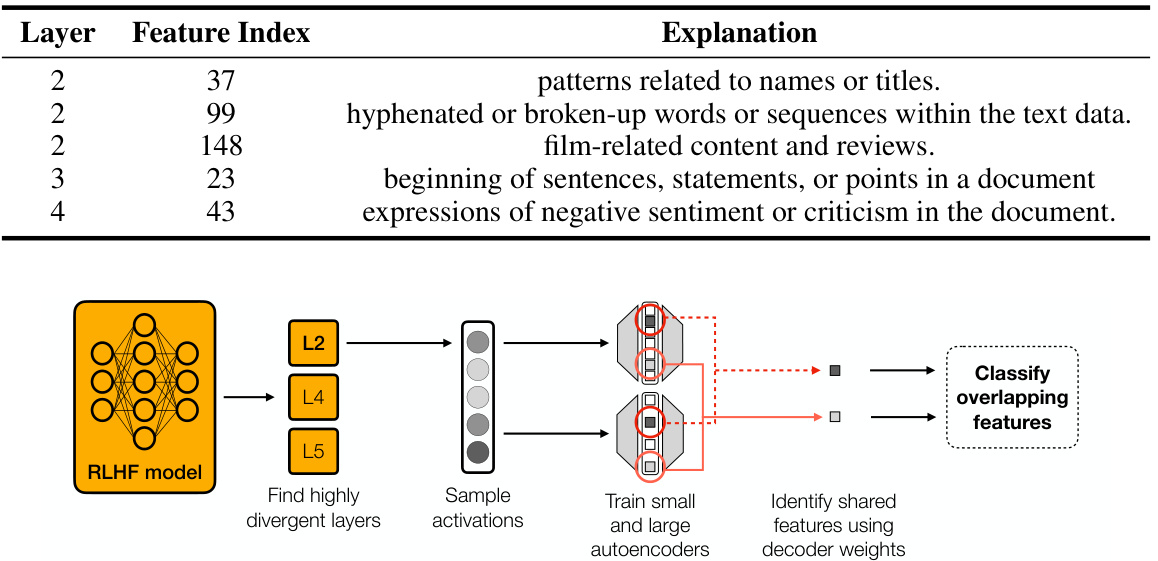

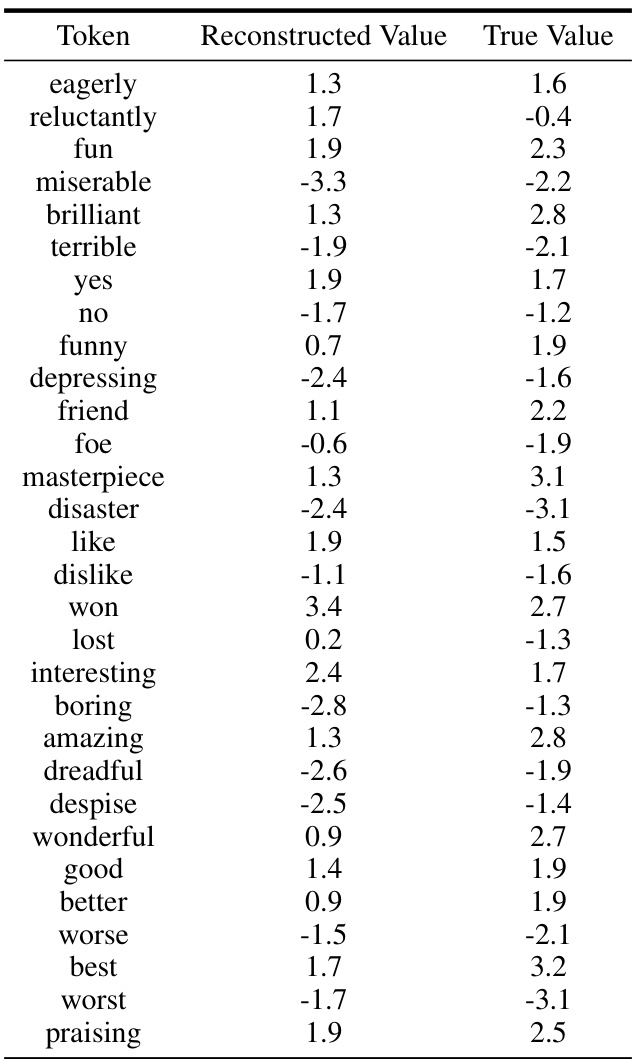

This table presents five examples of features identified by a sparse autoencoder trained on an LLM and the descriptions of those features generated by GPT-4. Each row shows the layer the feature is in, the feature’s index within that layer, and GPT-4’s description of the patterns the feature represents. These descriptions provide insights into the human-interpretable aspects of the learned patterns within the LLM’s activations.

This table presents five examples of feature descriptions generated by GPT-4 for features in a sparse autoencoder trained on an LLM. Each description is associated with a layer and feature index within the autoencoder’s decoder, providing context for understanding the feature’s role in the model’s processing of information related to a specific task (detailed in Appendix B). The table offers insight into the interpretability of the autoencoder’s learned features and their relevance to the task’s underlying concept.

This table presents five examples of feature descriptions generated by GPT-4 for features identified in a sparse autoencoder trained on an LLM. Each description explains a specific feature’s role in the LLM’s processing of the input text. The table also includes the layer and feature index of each described feature, providing context within the autoencoder’s architecture.

This table presents a comparison of sentiment scores. For thirty tokens, it shows the sentiment value as reconstructed by a model and the true sentiment value from the GPT-Neo-125m model. The purpose is to illustrate the accuracy of the model’s reconstruction of sentiment.

This table presents the results of calculating the Kendall Tau correlation between the predictions of the probes (which estimate the implicit feedback signal from LLM activations) and the true RLHF reward model, specifically focusing on negative tokens only. The Kendall Tau correlation measures the rank correlation between two ranked sets, indicating the strength of the monotonic relationship between the probe’s predictions and the actual reward values. The p-values associated with each correlation coefficient show the statistical significance of the observed correlations.

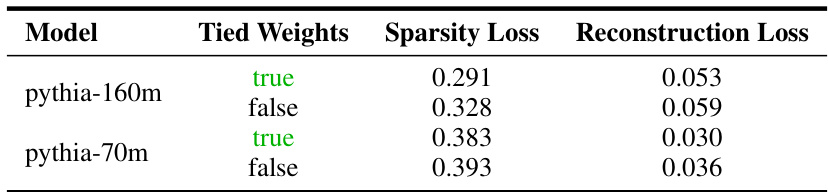

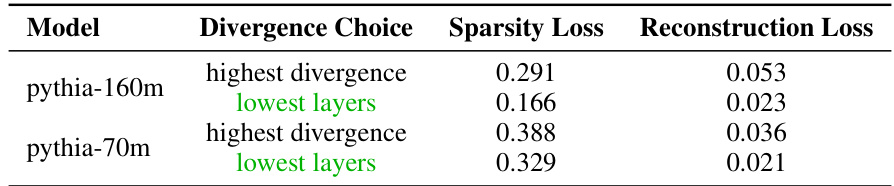

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing the performance of sparse autoencoders with tied and untied encoder and decoder weights. The experiment measures two metrics: normalized reconstruction loss and scaled true sparsity loss. The results are averaged across highly divergent layers in the models Pythia-70m and Pythia-160m, providing insights into the effects of weight tying on model performance and sparsity.

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing the performance of sparse autoencoders with tied and untied encoder/decoder weights. The metrics reported are normalized reconstruction loss and scaled true sparsity loss, averaged across all highly divergent layers in the models. The experiment aimed to determine the optimal weight-tying strategy for these autoencoders, which were used in a larger study of learned feedback patterns in large language models.

Full paper#