↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Existing methods for instruction-tuning large language models (LLMs) for code generation are often expensive, relying on human annotation or proprietary models. This limits accessibility and reproducibility. The high cost of human annotation and the restrictions imposed by proprietary LLMs significantly hinder progress in open-source code generation.

SelfCodeAlign tackles this problem by introducing a fully transparent and permissive self-alignment pipeline. This method generates diverse coding tasks and validates model responses without human intervention or external LLMs. Results show that models fine-tuned with SelfCodeAlign outperform those trained with prior state-of-the-art self-supervised methods across various benchmarks. It also produces the first fully transparent, permissively licensed, self-aligned code LLM that achieves state-of-the-art performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in large language models (LLMs) and code generation. It presents SelfCodeAlign, a novel, fully transparent, and permissive pipeline for self-aligning code LLMs. This addresses the limitations of existing methods that rely on costly human annotations or proprietary LLMs. The work opens up new avenues for research into self-supervised LLMs training and evaluation, significantly impacting the development of open-source code generation models.

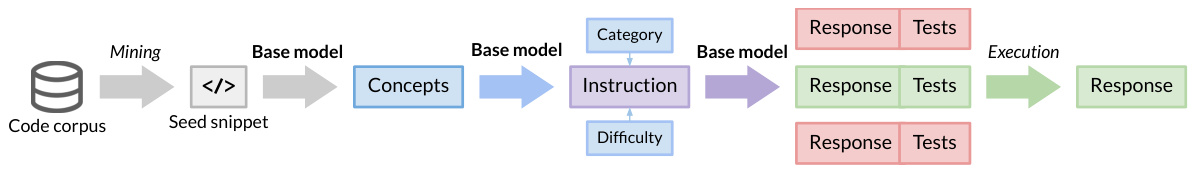

Visual Insights#

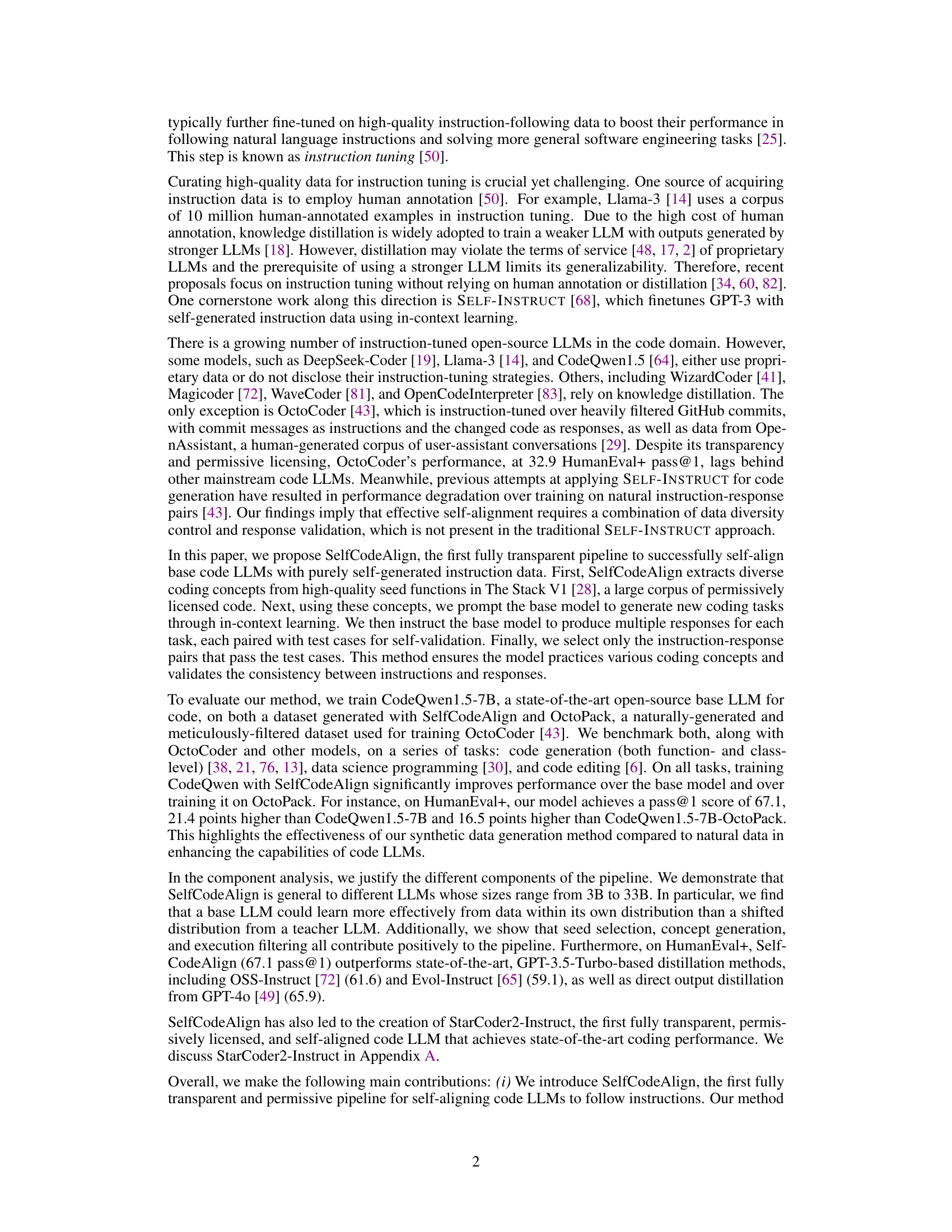

This figure illustrates the SelfCodeAlign pipeline. It begins with seed code snippets mined from a code corpus (The Stack). These snippets are fed into a base LLM to extract coding concepts. The base LLM then generates instructions using these concepts, along with a difficulty level and category. The base LLM generates multiple response-test pairs for each instruction. These pairs are then validated in a sandbox environment. Finally, the passing examples are used for instruction tuning. The figure visually depicts the flow of data through each stage of the pipeline, highlighting the use of the base model in multiple steps and the iterative nature of the response and test case generation and validation.

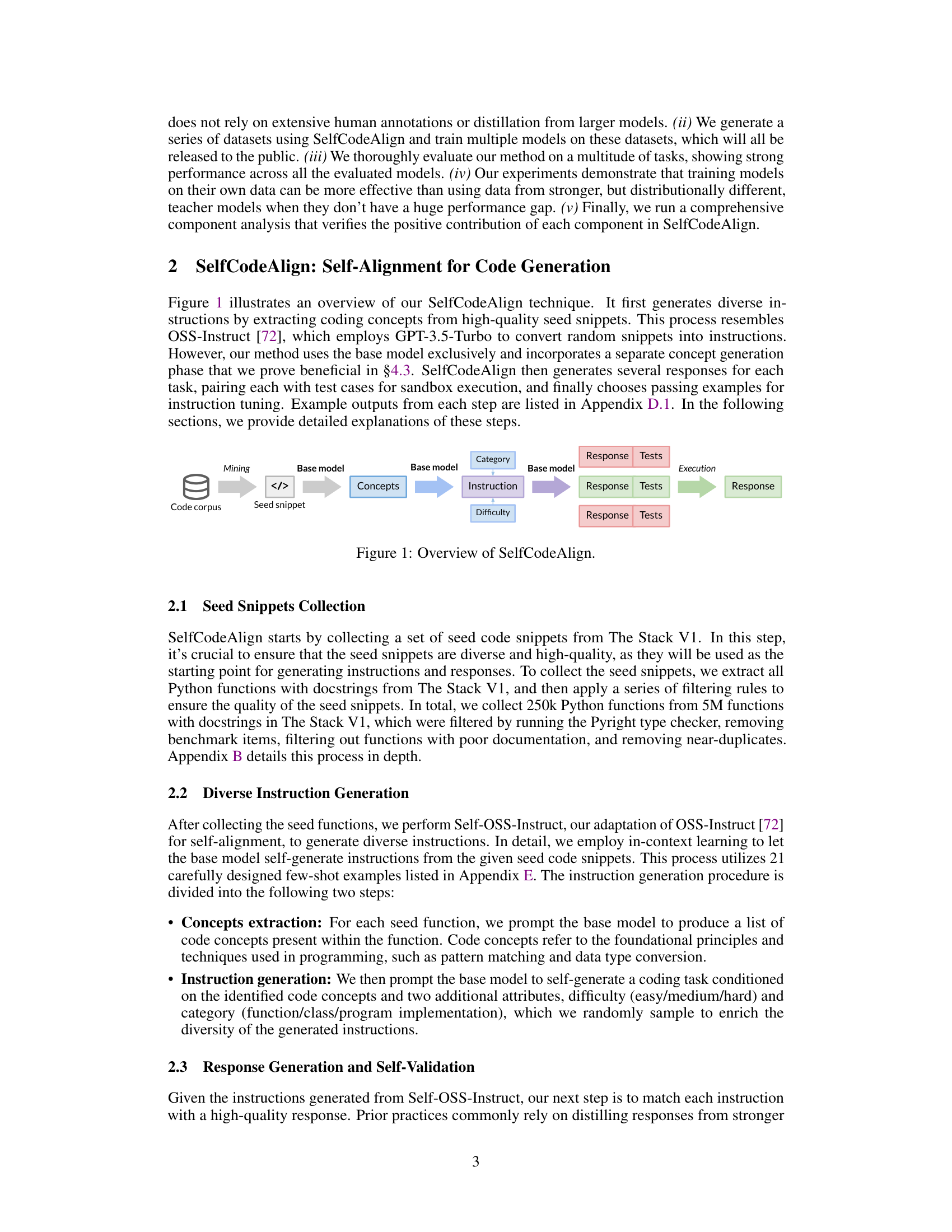

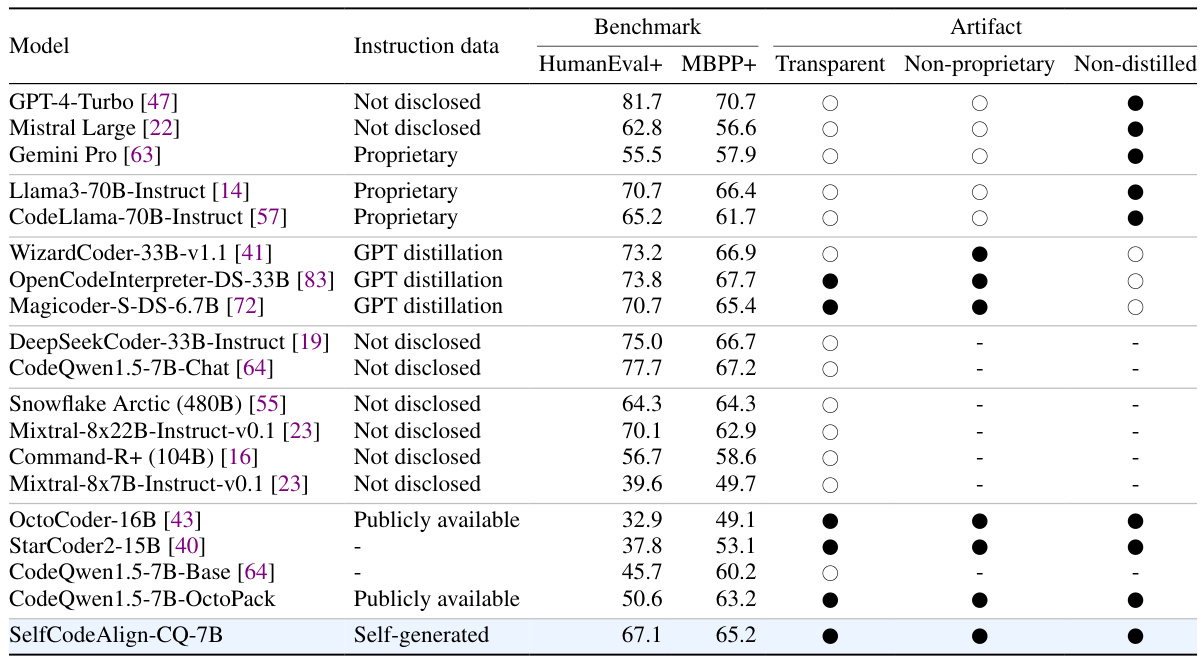

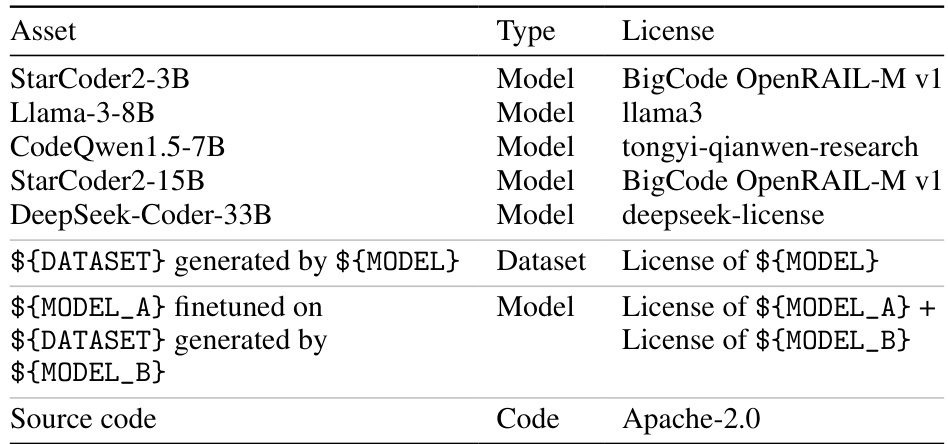

This table compares the performance (Pass@1) of various Large Language Models (LLMs) on the HumanEval+ and MBPP+ benchmarks for function-level code generation. It includes models trained with different methods (proprietary data, GPT distillation, self-generated data), highlighting the performance of SelfCodeAlign-CQ-7B in comparison to other models. The ‘Transparent’, ‘Non-proprietary’, and ‘Non-distilled’ columns indicate whether the model’s training data and methods are publicly accessible and free of distillation techniques.

In-depth insights#

Self-Alignment#

Self-alignment in the context of large language models (LLMs) is a crucial concept aiming to improve LLM performance without relying on extensive human annotations or external, potentially proprietary, data. The core idea is to leverage the LLM itself to generate its own training data, creating a closed-loop system. This approach offers the potential for greater transparency and broader accessibility. However, it introduces new challenges. The quality of self-generated data is paramount; poorly generated tasks and responses could hinder performance or introduce biases. Effective self-alignment often involves carefully designed processes for task generation, response validation, and filtering to ensure data quality and diversity. While self-alignment promises a more permissive and cost-effective path to instruction-tuned LLMs, rigorous evaluation is essential to demonstrate its effectiveness compared to traditional supervised fine-tuning and knowledge distillation techniques. The success of self-alignment hinges on the ability to generate high-quality and diverse data reflecting the target LLM’s strengths and weaknesses, making this a rich area for further research and development.

Code LLM#

Code LLMs represent a significant advancement in AI, demonstrating remarkable capabilities in various code-related tasks. Their pre-training on massive code datasets grants them a native understanding of programming languages and concepts, enabling them to perform tasks like code generation, debugging, and translation with impressive accuracy. However, these models often require further fine-tuning, often with substantial human annotation or distillation from larger, proprietary models which limits accessibility and transparency. Research into self-alignment techniques, such as the SelfCodeAlign method described in the provided paper, aims to address this limitation by training LLMs using data generated by the model itself without reliance on external datasets. This approach not only enhances transparency but also reduces reliance on costly human annotation and access to proprietary LLMs. Further research focuses on improving the efficiency and scalability of these models, especially for handling long contexts and complex programming tasks, and mitigating potential biases in training data. The ongoing development of open-source Code LLMs and self-alignment techniques will be key to unlocking the full potential of these technologies and promoting widespread adoption across various applications.

Instruction Tuning#

Instruction tuning, a crucial technique in enhancing large language models (LLMs), significantly improves their ability to understand and follow user instructions. It involves fine-tuning pre-trained LLMs on a dataset of instruction-response pairs, thereby bridging the gap between raw language understanding and task-oriented execution. This approach is particularly valuable for complex tasks like code generation, where accurately interpreting natural language instructions is paramount. Instruction tuning’s effectiveness hinges on the quality and diversity of the training data, with high-quality datasets leading to superior performance. However, acquiring such datasets often requires substantial resources, such as costly human annotation or reliance on proprietary LLMs, posing significant limitations. Self-supervised methods are actively being explored to overcome these limitations, by generating synthetic datasets from base LLMs, and thus enable more accessible and transparent instruction tuning for a wider range of LLMs.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section would ideally delve into expanding SelfCodeAlign’s capabilities. Addressing longer context lengths is crucial, as current limitations hinder the handling of complex codebases. Improving the quality of generated tests is another key area, as more robust validation is needed to ensure reliability. Furthermore, exploring SelfCodeAlign’s adaptability to different programming languages beyond Python would broaden its impact. Investigating the effectiveness of incorporating reinforcement learning to refine the self-alignment process and potentially reduce bias is also important. Finally, a comprehensive evaluation of SelfCodeAlign on more challenging coding tasks and a detailed comparison against other cutting-edge techniques would strengthen the paper’s conclusions. Addressing potential safety concerns related to the generation of untested code is paramount and deserves careful consideration.

Limitations#

A critical analysis of the ‘Limitations’ section of a research paper would delve into the acknowledged shortcomings and constraints of the study. Data limitations often surface, such as a small sample size or biases in data collection that could affect the generalizability of findings. Methodological limitations might involve the chosen research methods’ inherent biases or limitations in the way the data was analyzed or the limitations of the model itself, for instance. Resource constraints are also often highlighted, emphasizing that the availability of specific resources impacted the feasibility of the project or prevented a more comprehensive study. Finally, the discussion of limitations would address the study’s scope, outlining aspects that were not addressed or factors that were outside the scope of the current research, potentially influencing interpretation of the outcomes. Transparency about these limitations strengthens the paper’s credibility and encourages further research to address the gaps identified.

More visual insights#

More on tables

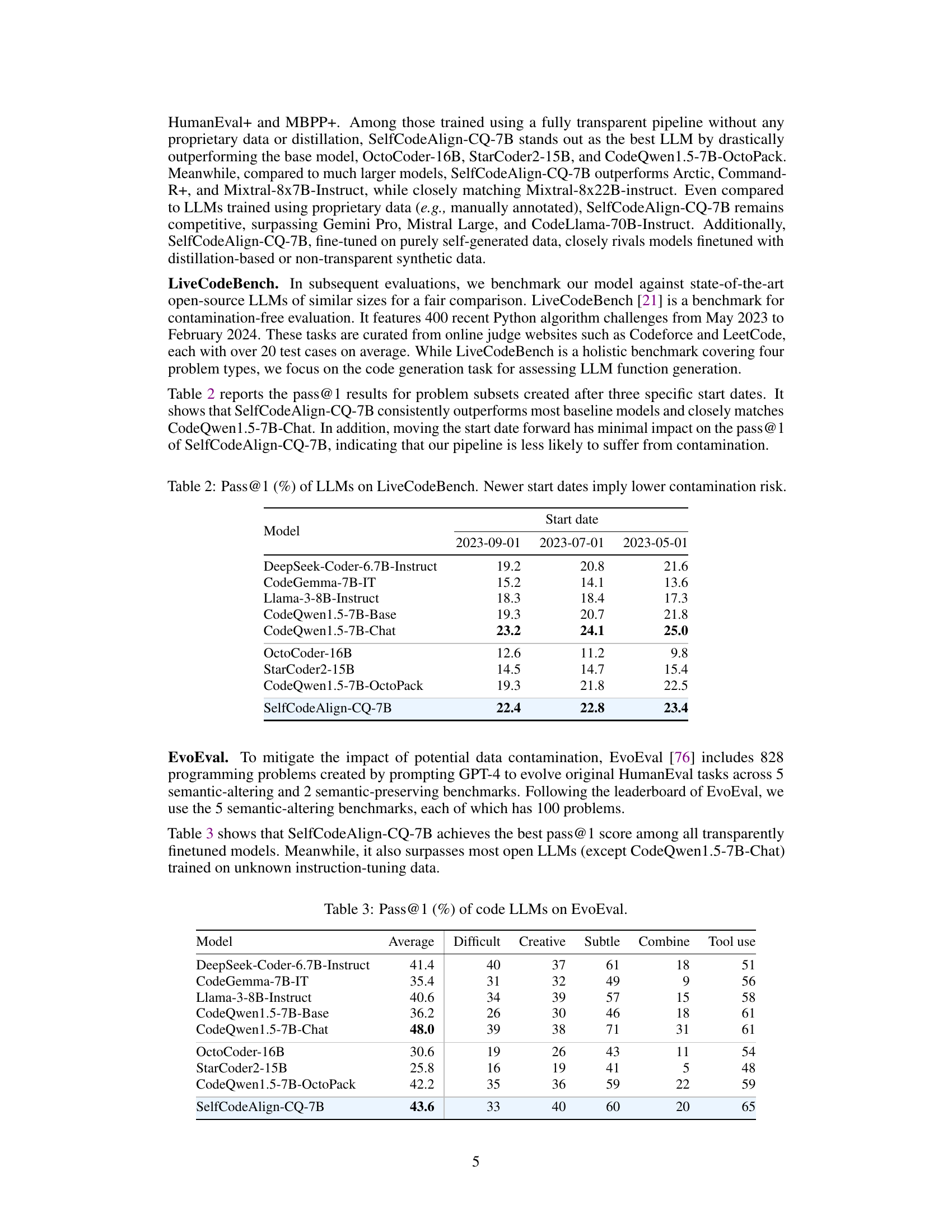

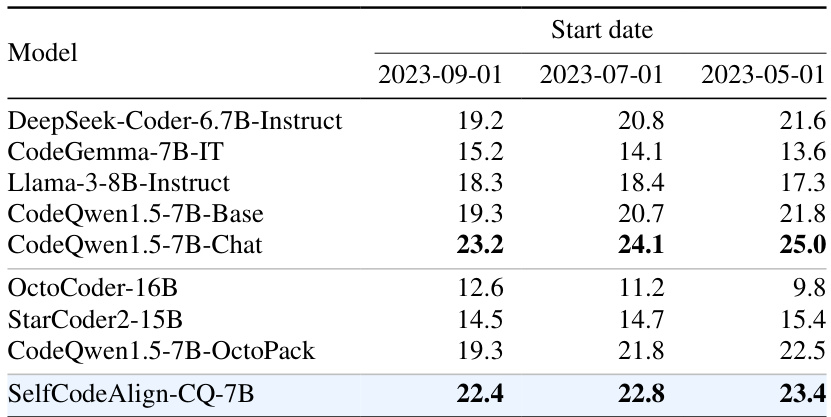

This table presents the pass@1 scores achieved by various LLMs on the LiveCodeBench benchmark. LiveCodeBench is a benchmark designed to mitigate data contamination issues. The table shows pass@1 scores for three different start dates (2023-09-01, 2023-07-01, 2023-05-01). A newer start date implies a lower risk of contamination because the data used in training the models was less likely to overlap with data from the benchmark tasks. This allows for a fairer comparison between models and assessment of their ability to generate code without relying on data from the same source as the benchmark.

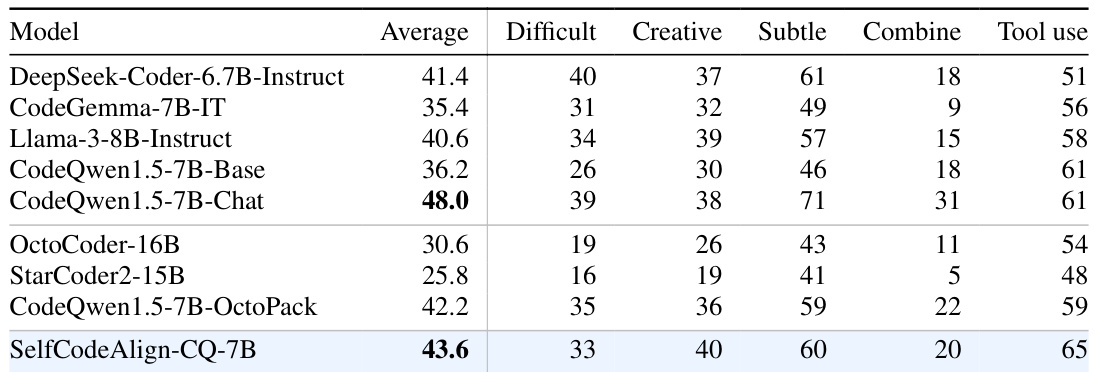

This table presents the performance of various code LLMs on the EvoEval benchmark, broken down by different task subcategories (Difficult, Creative, Subtle, Combine, Tool use). It compares the pass@1 scores (percentage of tasks where the model’s top-ranked code passed all tests) for different models. The models are evaluated on code generation tasks designed to assess various facets of code generation capability.

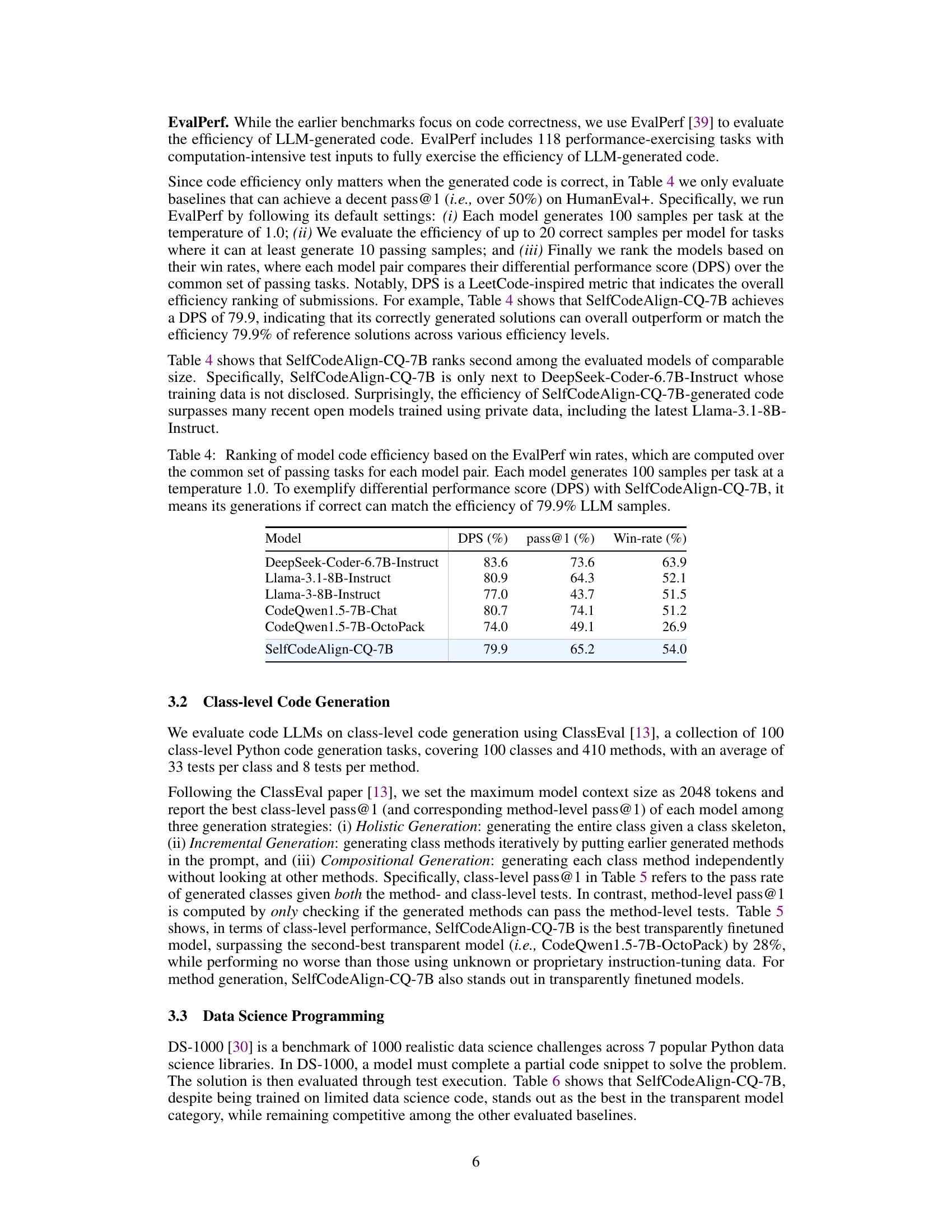

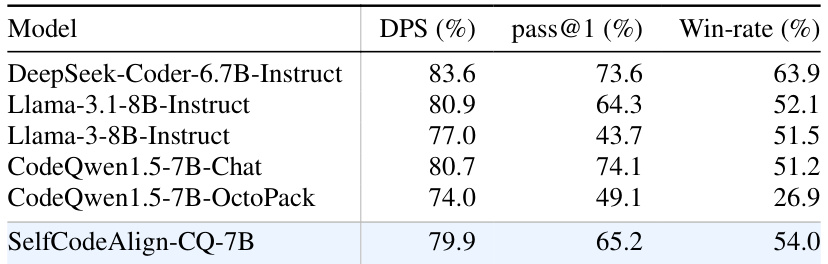

This table presents the ranking of different LLMs based on their code efficiency using the EvalPerf metric. The ranking is determined by comparing the performance of each model pair across tasks where both models produced correct code. The table includes the differential performance score (DPS), the pass@1 rate (percentage of correct code generation), and the win rate (percentage of times one model’s correct submissions outperform the other’s) for each model.

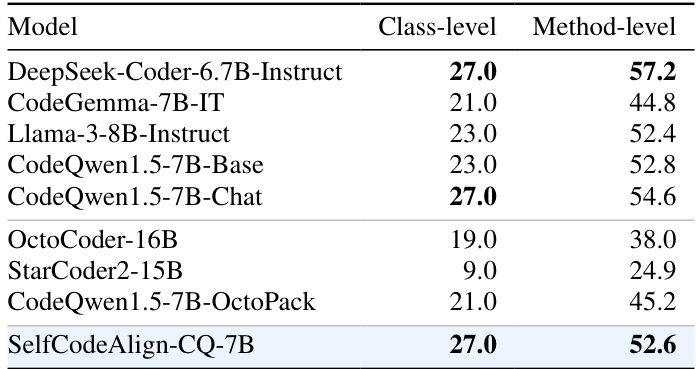

This table presents the performance of various code LLMs on the ClassEval benchmark, specifically focusing on class-level and method-level pass@1 scores using greedy decoding. The results are useful for comparing the effectiveness of different models in generating complete and correct class-level code.

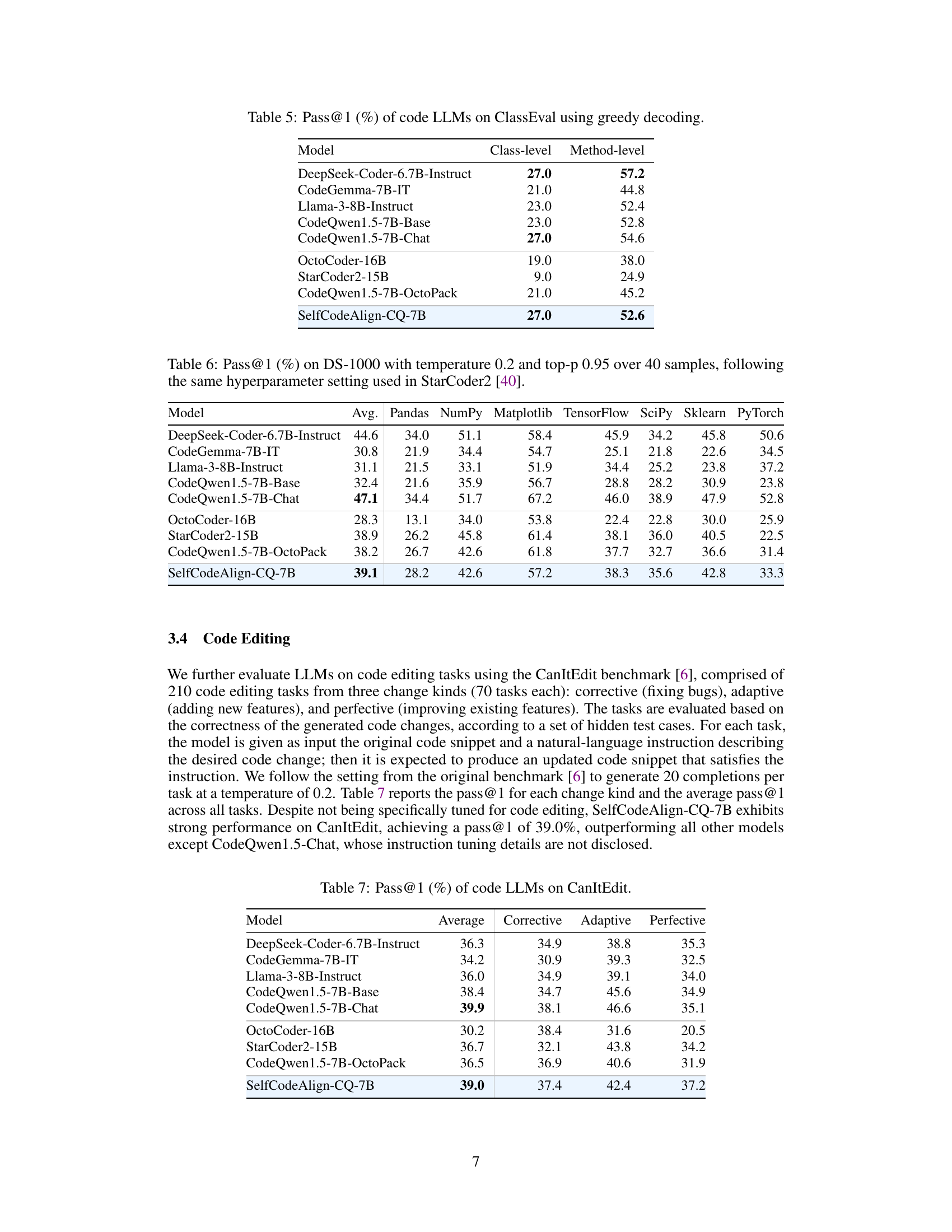

This table presents the pass@1 scores achieved by various large language models (LLMs) on the HumanEval+ and MBPP+ benchmarks for function-level code generation. The models are evaluated using greedy decoding. The table includes information about the type of instruction data used for training each model (proprietary, public, self-generated, distilled from GPT), and whether the model is transparent and non-proprietary. This allows for a comparison of different approaches to instruction tuning in code generation and highlights the relative performance of the self-aligned model compared to other methods.

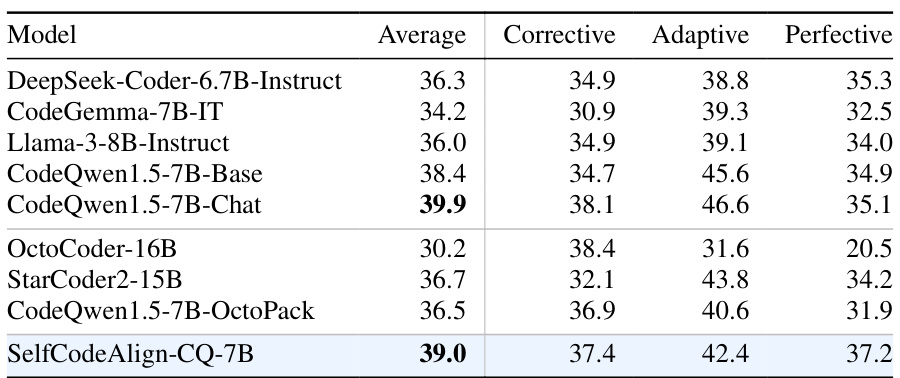

This table presents the performance of various code LLMs on the CanItEdit benchmark, specifically focusing on code editing tasks categorized as corrective, adaptive, and perfective. The ‘Average’ column shows the overall performance across all three categories. It allows for a comparison of the effectiveness of different LLMs in handling various types of code editing changes.

This table presents the HumanEval+ pass@1 scores achieved when finetuning various base language models (StarCoder2-3B, Llama-3-8B, StarCoder2-15B, DeepSeek-Coder-33B, and CodeQwen1.5-7B) using data generated by different data-generation models. Each row represents a different base model, and each column represents a different data-generation model. The values in the table show the pass@1 scores achieved when the base model is finetuned on the data generated by the corresponding data-generation model. The diagonal values represent the results of self-alignment (i.e., finetuning the base model on data generated by the same base model).

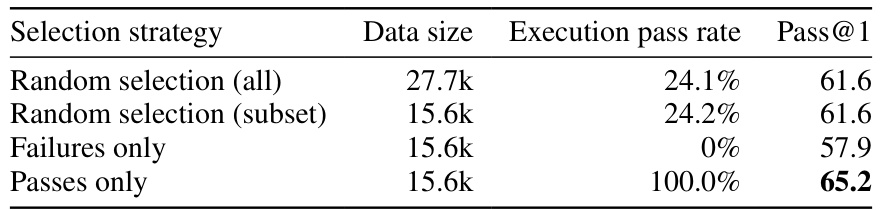

This table shows the results of four different experiments on HumanEval+, comparing four different response selection strategies. The four strategies are: Random Selection (all), Random Selection (subset), Failures only, and Passes only. For each strategy, the table shows the data size, execution pass rate, and Pass@1 score. The results demonstrate the importance of execution filtering and code correctness for self-alignment. The Passes Only strategy has the highest Pass@1 score (65.2).

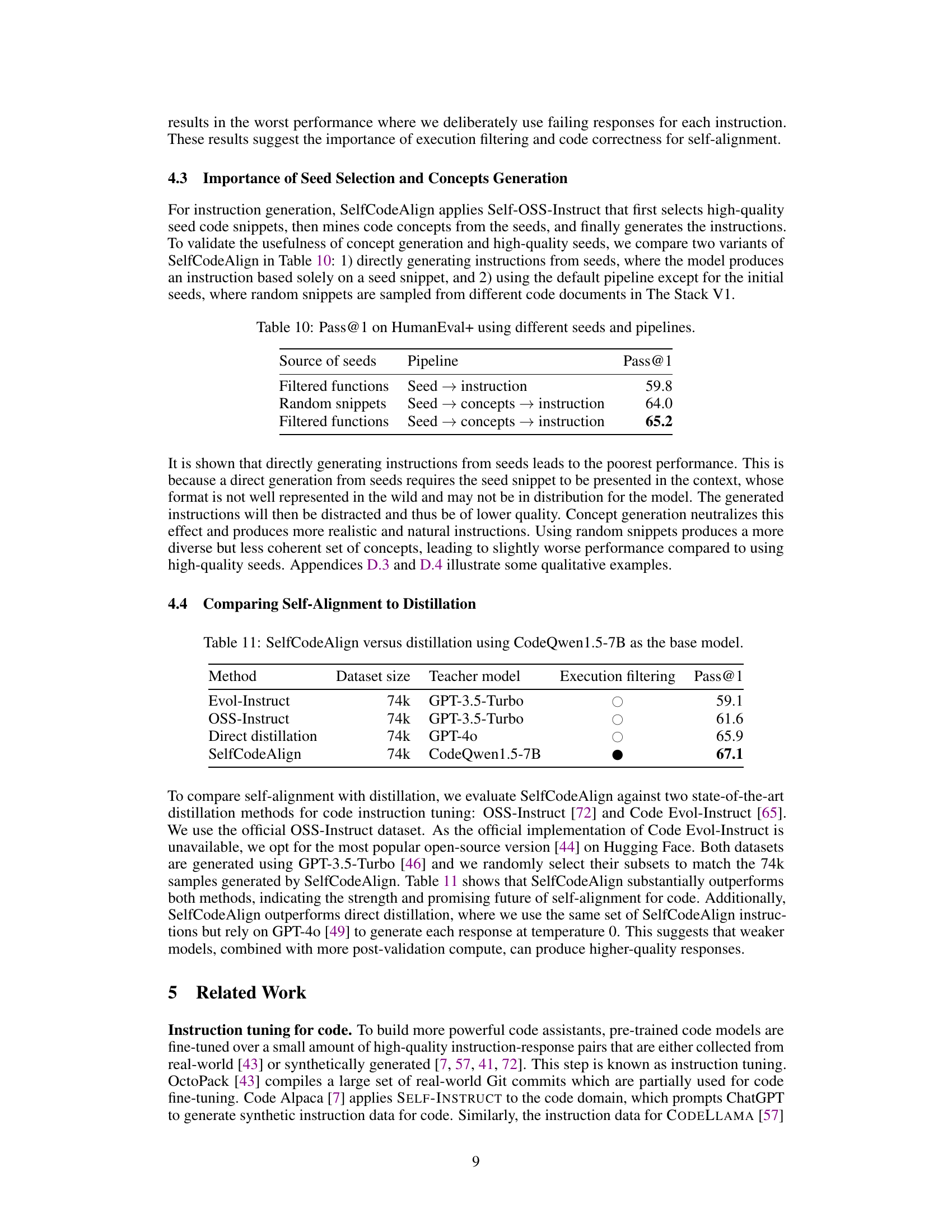

This table shows the performance of SelfCodeAlign on HumanEval+ using different seeds and pipelines. The first row shows the results of directly generating instructions from filtered functions, while the second row shows the results of generating instructions from random snippets after mining concepts. The last row shows the performance of using the original pipeline with filtered functions. The results show that the original pipeline performs best.

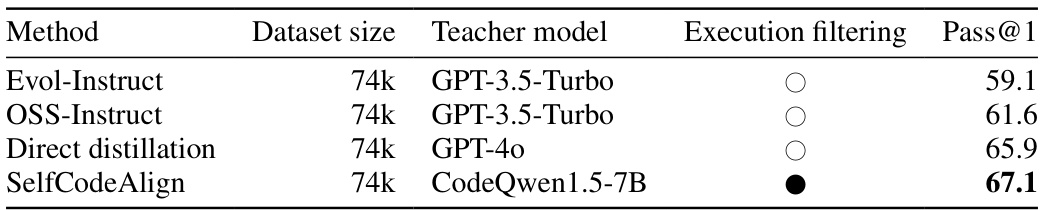

This table compares the performance of SelfCodeAlign against several state-of-the-art distillation methods for code instruction tuning. It shows the dataset size, the teacher model used for distillation (GPT-3.5-Turbo or GPT-40), whether execution filtering was used, and the resulting pass@1 score on HumanEval+. SelfCodeAlign achieves the best performance without relying on a stronger, external model for distillation.

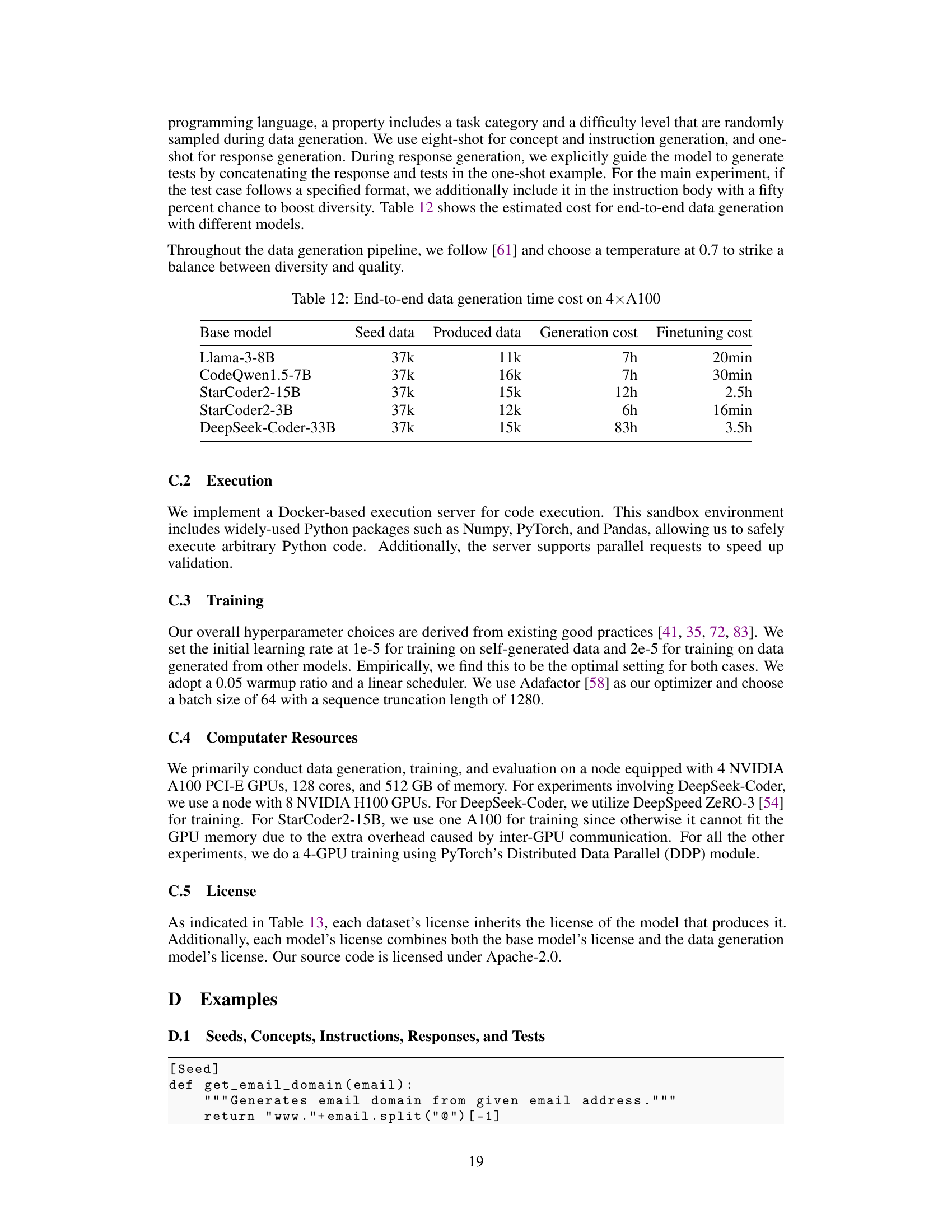

This table shows the estimated computational cost for end-to-end data generation using different base models. The cost is broken down into the time required for seed data generation, data production, overall data generation, and the subsequent finetuning process. Note that the amount of seed data used was fixed at 37k examples across all experiments.

This table compares the performance (Pass@1) of various large language models (LLMs) on the HumanEval+ and MBPP+ benchmarks for function-level code generation. It shows the pass@1 scores for each model, indicating the percentage of times the model generated a correct solution on the first attempt using greedy decoding. The table also indicates whether each model used proprietary data, knowledge distillation, or whether its training was fully transparent and non-proprietary.

Full paper#