↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Fine-tuning large language models (LLMs) often relies on large, task-specific datasets, which are not always available. This limitation hinders the application of LLMs to specialized domains, like healthcare, where acquiring substantial amounts of high-quality data can be challenging. This paper tackles this issue, addressing the limitations of standard fine-tuning methods that often suffer from catastrophic forgetting and data mismatch.

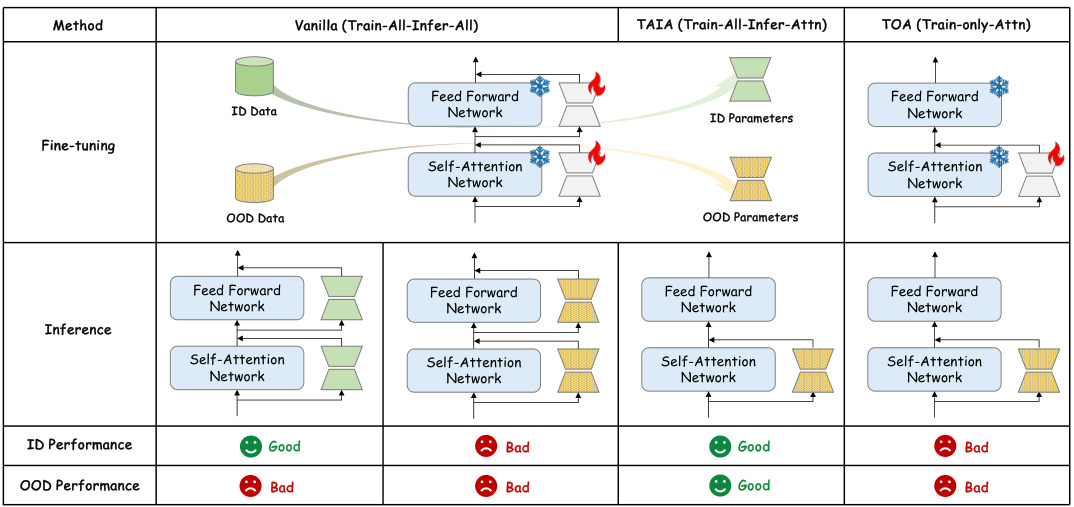

The proposed solution, Training All parameters but Inferring with only Attention (TAIA), is an innovative inference-time method. TAIA trains all LLM parameters but selectively leverages only the attention parameters during inference. This approach mitigates the negative effects of data mismatch. The researchers empirically validate TAIA on various datasets and LLMs, demonstrating superior performance to standard fine-tuning and base models, especially when dealing with OOD data. The method’s resistance to jailbreaking and improved performance on specialized tasks highlight its potential for enhancing LLM applications across diverse scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs) as it introduces a novel inference-time intervention (TAIA) that significantly improves LLM performance, particularly in data-scarce scenarios. TAIA’s effectiveness in handling out-of-distribution (OOD) data is a significant advancement, offering a robust solution for real-world applications where large, high-quality datasets are often unavailable. The findings open new avenues for exploring parameter-efficient fine-tuning and improving model adaptability.

Visual Insights#

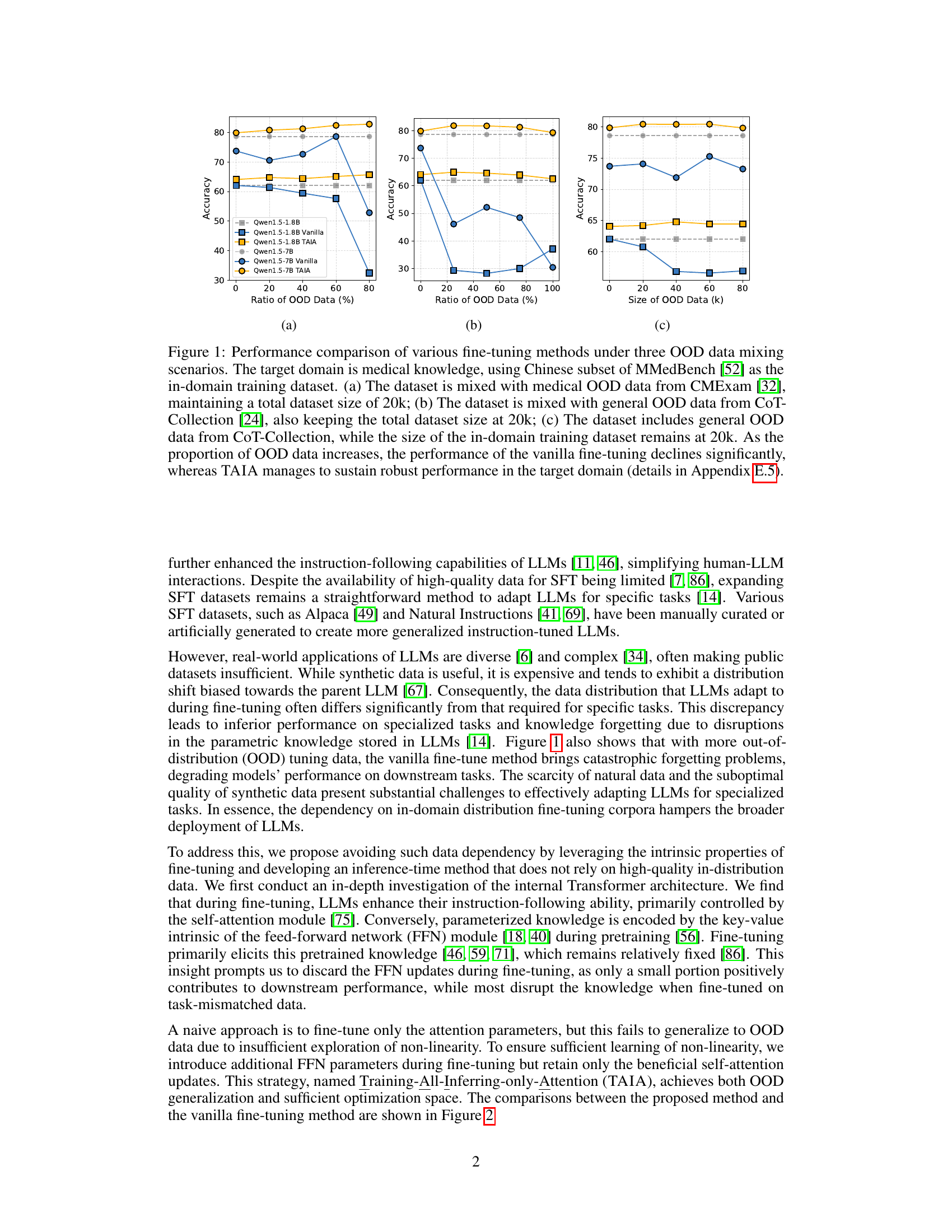

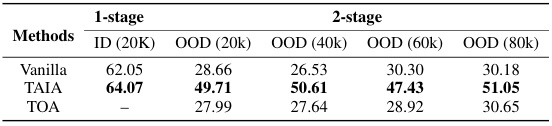

This figure compares the performance of different fine-tuning methods (vanilla and TAIA) when dealing with varying amounts of out-of-distribution (OOD) data in a medical knowledge domain. Three scenarios are shown: (a) mixing with medical OOD data, (b) mixing with general OOD data, and (c) increasing the amount of general OOD data while keeping the in-domain data constant. The results demonstrate that vanilla fine-tuning’s performance degrades significantly as the proportion of OOD data increases, while TAIA maintains robust performance.

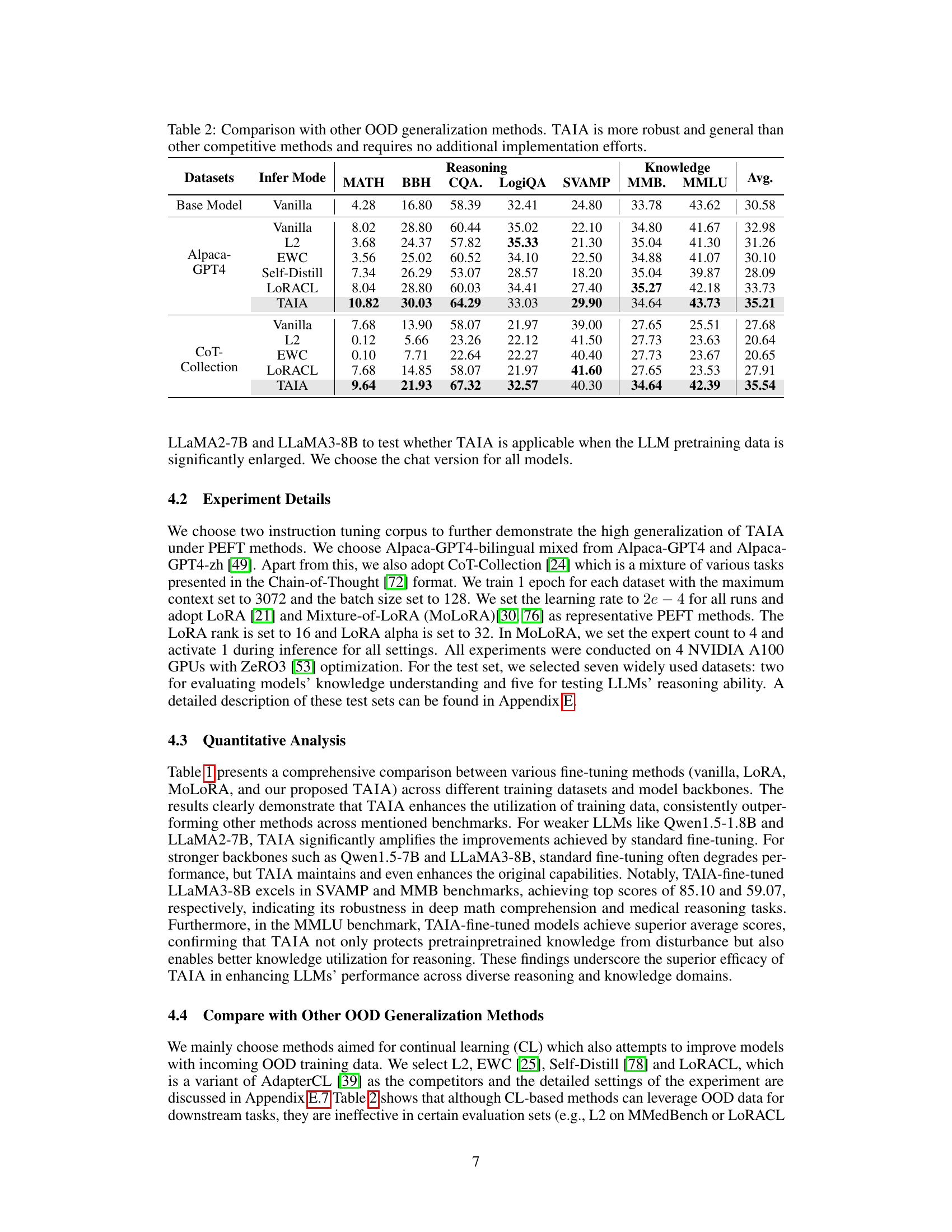

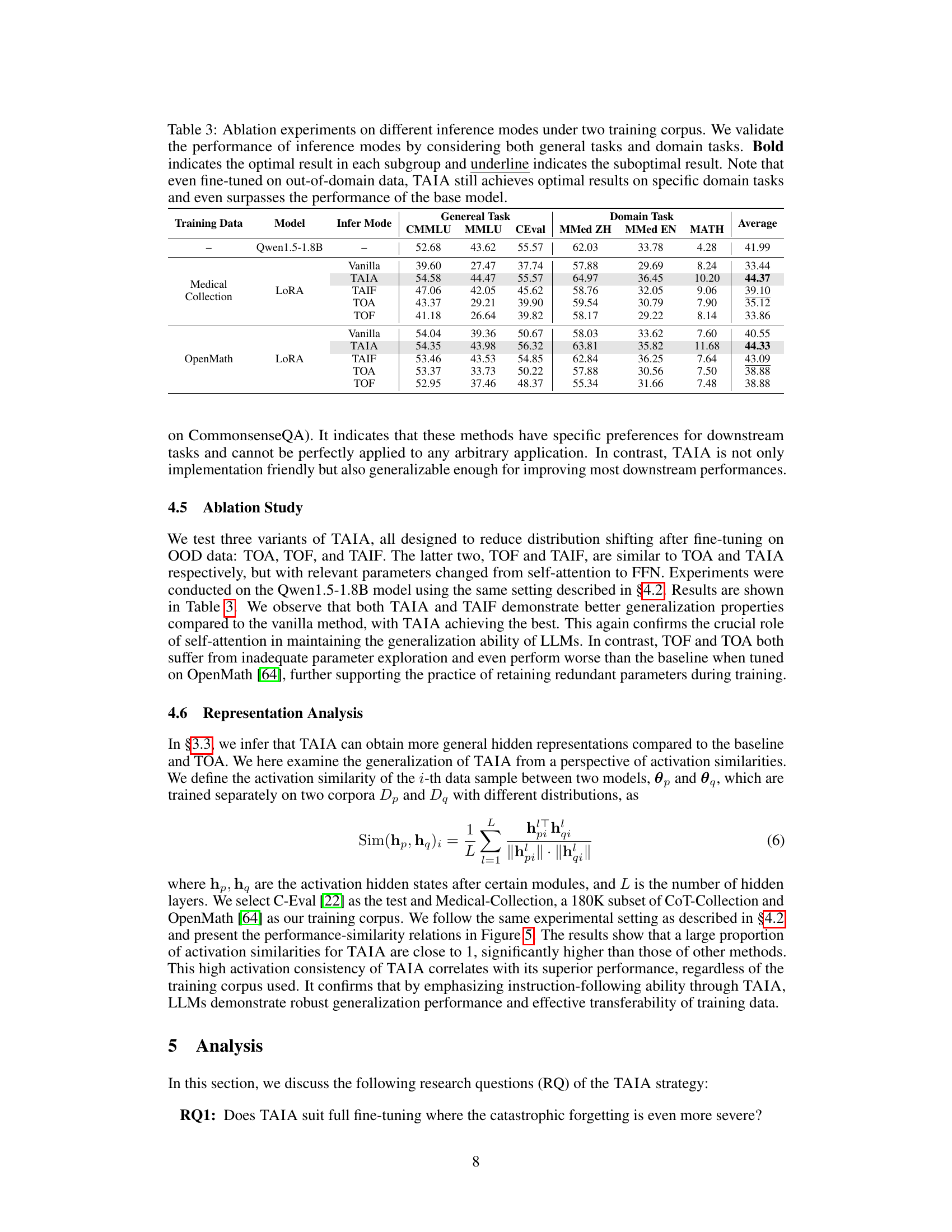

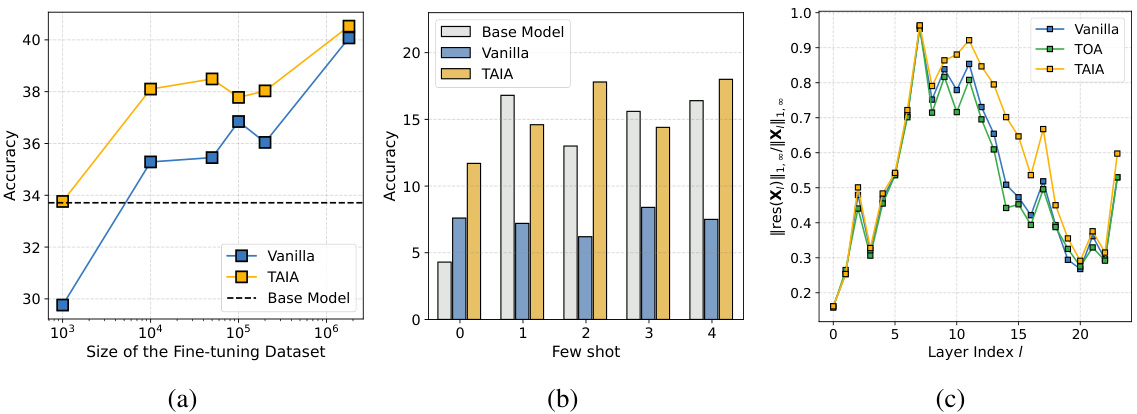

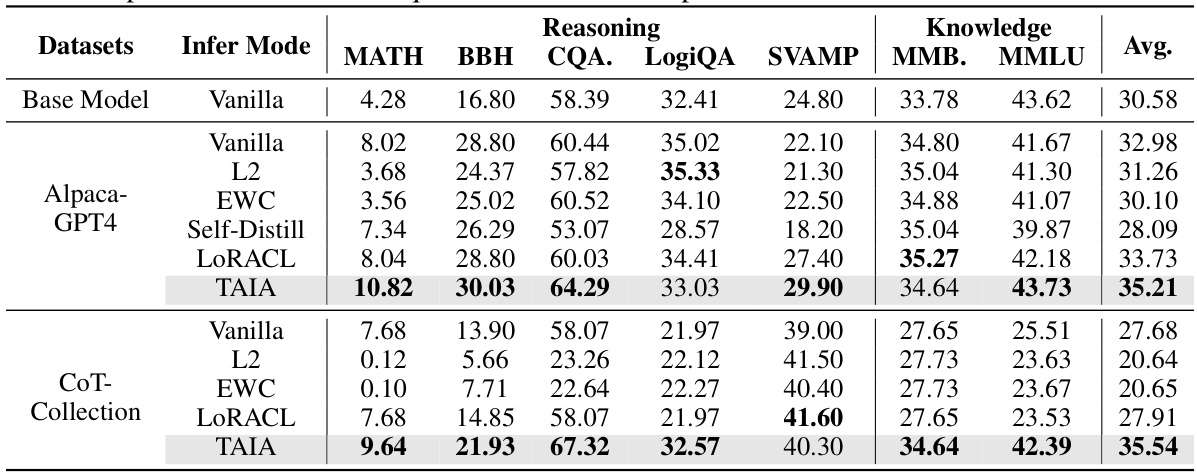

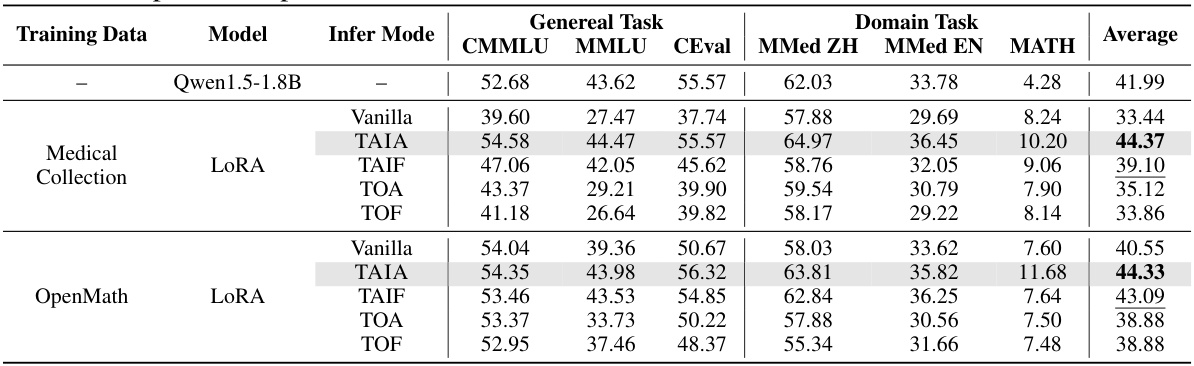

This table presents the results of validation experiments conducted to evaluate the performance of TAIA across various large language models (LLMs), training datasets, and fine-tuning methods. It shows the accuracy achieved on seven downstream tasks (MATH, BBH, CQA, LogiQA, SVAMP, MMB, MMLU) by different models trained using two distinct corpora (Alpaca-GPT4 and CoT-Collection) and two fine-tuning techniques (LoRA and MoLoRA). For each setting, three inference approaches were evaluated: Vanilla (full fine-tuning), TAIA (training all parameters but inferring only with attention), and the baseline model. The table highlights the optimal and suboptimal results for each subgroup and shows that TAIA generally achieves the best results across various settings.

In-depth insights#

TAIA: An Overview#

TAIA, or Training All parameters but Inferring with only Attention, presents a novel approach to fine-tuning large language models (LLMs). It addresses the challenge of limited high-quality, in-distribution data often encountered in specialized domains. The core insight is that not all parameter updates during fine-tuning contribute equally to improved downstream performance. TAIA leverages this by selectively using only the updated attention parameters during inference, while training all parameters during the training phase. This method demonstrates robustness to out-of-distribution (OOD) data, effectively mitigating catastrophic forgetting and improving performance across various downstream tasks. Its key advantage lies in its adaptability, allowing LLMs to perform well even with limited in-domain data, enhancing its applicability to specialized areas with data scarcity. The method’s simplicity and effectiveness are further highlighted by its superior performance compared to both fully fine-tuned models and base models in several experiments.

OOD Fine-tuning#

Out-of-Distribution (OOD) fine-tuning tackles the challenge of adapting Large Language Models (LLMs) to downstream tasks with limited in-distribution data. The core problem is the mismatch between the training data distribution and the target task’s distribution. This often leads to poor performance, especially in specialized domains lacking extensive high-quality datasets. OOD fine-tuning aims to leverage data from other, related domains to improve performance on the target task, thereby mitigating the reliance on scarce in-distribution data. Effective OOD fine-tuning methods require careful consideration of parameter updates, often focusing on selectively updating parameters most beneficial for generalization rather than wholesale fine-tuning. The success of OOD fine-tuning hinges on the ability to extract transferable knowledge from the auxiliary OOD data without incurring negative transfer or catastrophic forgetting. This involves sophisticated techniques that balance the exploitation of OOD information with the preservation of knowledge already learned by the model. An effective OOD fine-tuning strategy may involve parameter-efficient fine-tuning, regularization, or other techniques to manage the distribution shift. Ultimately, the goal is to develop LLMs that are more adaptable and robust, capable of performing well even when faced with data scarcity and distribution mismatch. Research in this area is crucial for expanding the practical applicability of LLMs across diverse domains.

TAIA’s Inference#

TAIA’s inference mechanism is a crucial aspect of its effectiveness. Instead of using all fine-tuned parameters during inference, TAIA selectively leverages only the updated attention parameters, discarding the potentially disruptive FFN updates acquired during fine-tuning with out-of-distribution (OOD) data. This selective inference strategy is based on the observation that attention parameters are primarily responsible for enhancing instruction-following capabilities, while FFN parameters primarily store and retrieve pretrained knowledge. By retaining only the beneficial attention updates, TAIA enhances model robustness and generalization to OOD data. It essentially performs a knowledge distillation, prioritizing the instruction-following aspect over the potentially noisy FFN knowledge updates gained from OOD data. The efficiency of this approach is demonstrated by its superior performance across various downstream tasks compared to both fully fine-tuned models and base models. Furthermore, the method’s resilience to data mismatches, and its resistance to jailbreaking, suggest that TAIA offers a promising approach for adapting LLMs to specialized tasks in data-scarce environments.

TAIA’s Limitations#

The TAIA method, while promising, has limitations. Its reliance on pre-trained knowledge restricts its applicability to tasks where this knowledge is sufficient. For tasks requiring specialized knowledge, TAIA may underperform compared to methods that explicitly learn new knowledge. The effectiveness of TAIA depends heavily on the quality of the pre-trained model and the training data. Noisy or biased training data can negatively impact performance. Furthermore, TAIA’s reliance on self-attention during inference may limit its ability to capture complex non-linear relationships that are often essential for advanced reasoning tasks. Additional research is needed to address these limitations and explore scenarios where TAIA might not generalize well, particularly in cases with severe knowledge mismatches or insufficient high-quality training data. The limited empirical evaluations need to be addressed with a broader set of tasks and models for better validation. The need for a more comprehensive analysis of its potential limitations and failure modes is vital for a complete evaluation.

Future of TAIA#

The future of TAIA hinges on addressing its current limitations and expanding its capabilities. Reducing reliance on in-domain data is crucial, perhaps by identifying a minimal set of trainable parameters to maximize exploration while minimizing distribution shifts. A more granular approach to parameter selection, going beyond the coarse separation of self-attention and FFN modules, could significantly enhance generalization. Adaptive parameter maintenance strategies, rather than a simple separation, could further improve performance on knowledge-intensive tasks. Finally, exploring the applicability of TAIA across different architectural designs and its interactions with other fine-tuning methodologies is key to broadening its impact and establishing its robustness as a universally applicable technique for improving LLM adaptability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

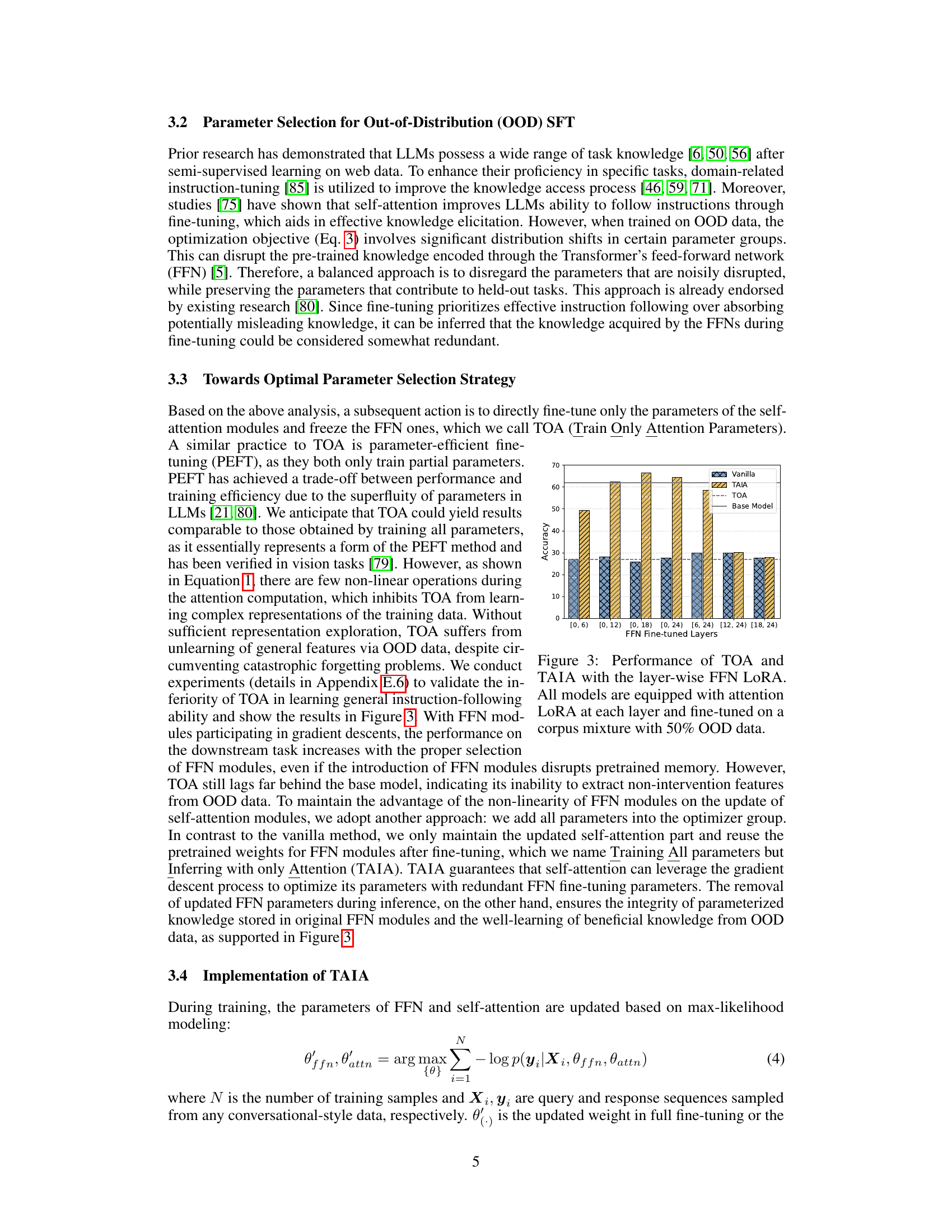

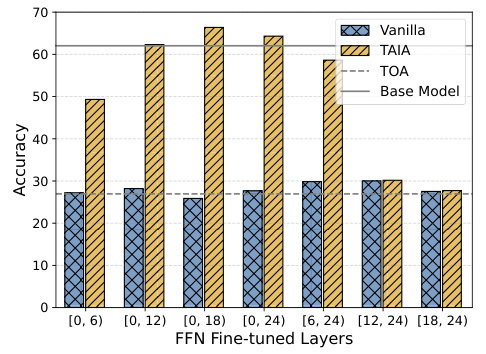

This figure shows the performance comparison between TOA (Train Only Attention Parameters) and TAIA (Training All parameters but Inferring with only Attention) methods. Both methods use LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) and fine-tune only part of the model parameters. The x-axis represents the number of FFN (Feed-Forward Network) layers that are fine-tuned. The y-axis represents the accuracy achieved on a downstream task. The figure demonstrates that TAIA consistently outperforms TOA, highlighting the benefit of incorporating some FFN parameter updates during training, even when only the attention parameters are used during inference.

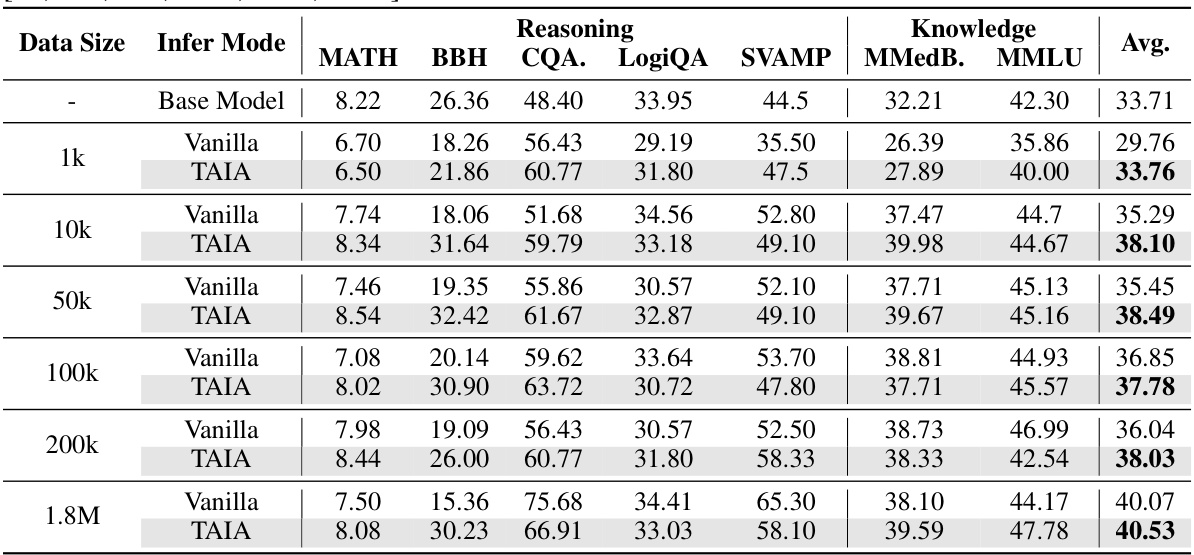

This figure presents a three-part analysis of the impact of fine-tuning dataset size on model performance using the TAIA method. Part (a) shows the average accuracy across different sizes of fine-tuning datasets, highlighting the performance gains of TAIA over the vanilla fine-tuning and base model. Part (b) focuses on few-shot learning performance using the MATH dataset, revealing TAIA’s ability to retain few-shot capabilities. Part (c) displays the layer-wise residual rank of the hidden states within the MATH dataset, demonstrating TAIA’s effectiveness in leveraging the representation capabilities of self-attention modules.

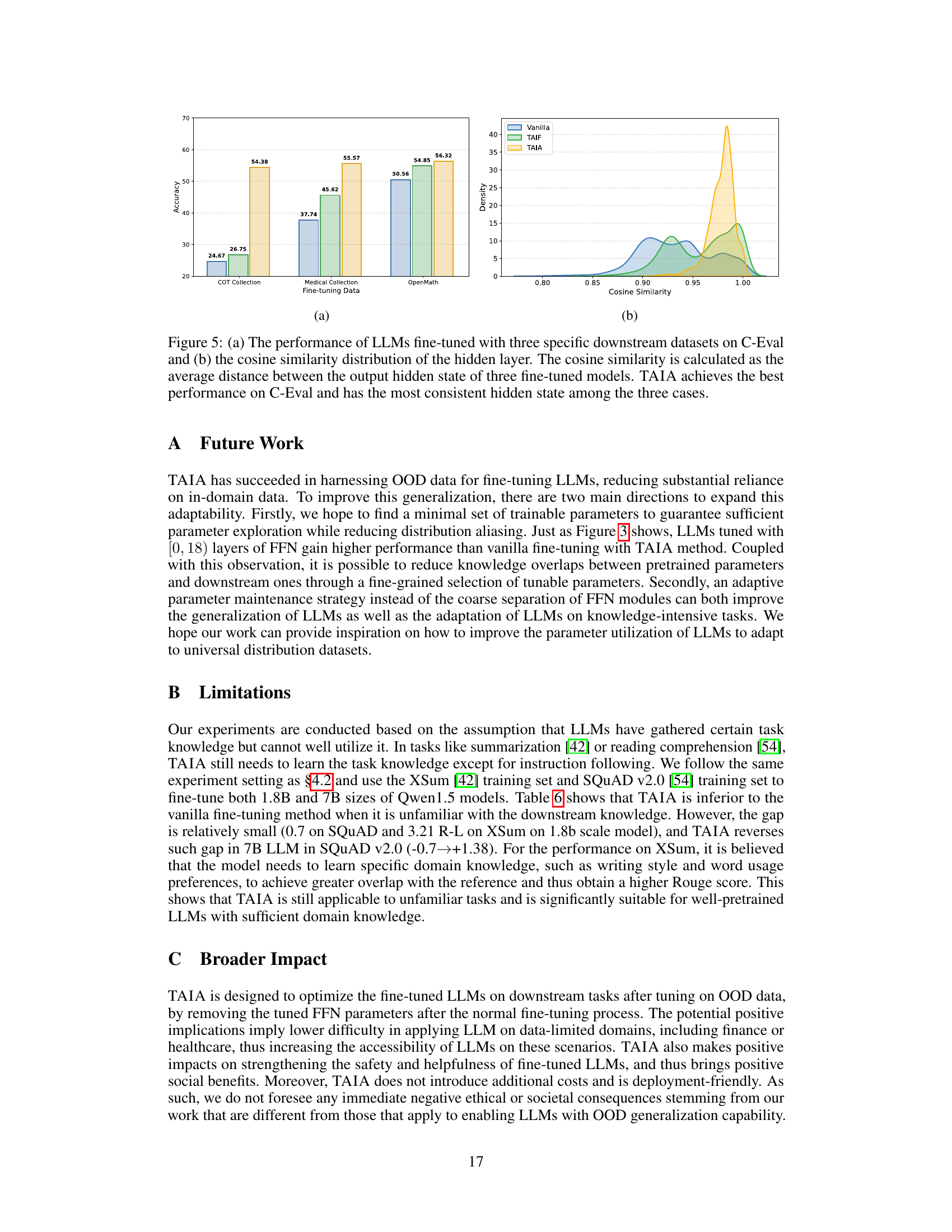

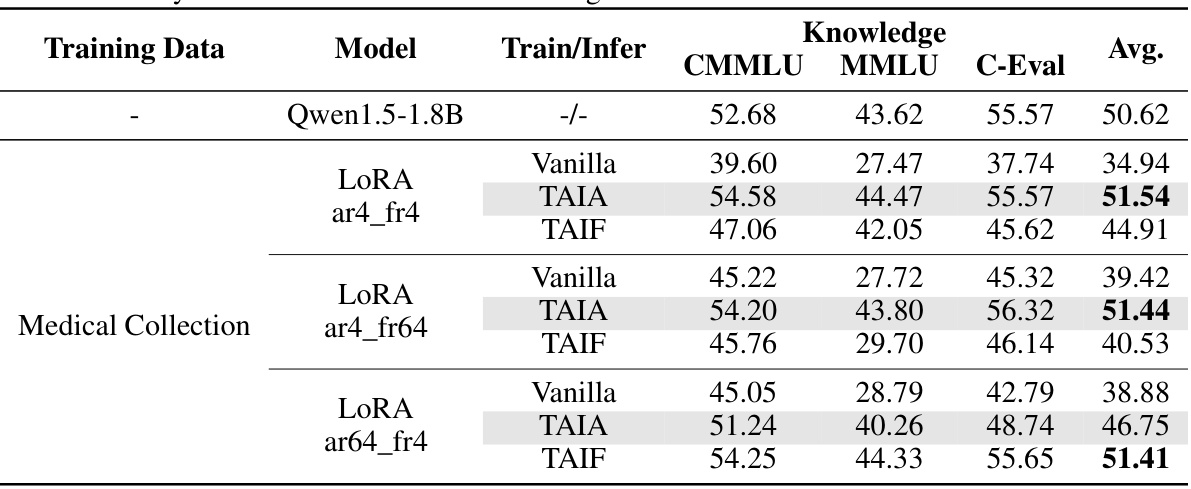

This figure shows the performance comparison of different fine-tuning methods (Vanilla, TAIF, and TAIA) on three downstream datasets (COT Collection, Medical Collection, and OpenMath) using C-Eval benchmark. The left panel (a) presents a bar chart showing the accuracy of each method on each dataset. The right panel (b) displays kernel density estimates illustrating the distribution of cosine similarity for the hidden states of the three models. TAIA consistently outperforms other methods and exhibits higher similarity among hidden states, indicating better generalization.

More on tables

This table presents the results of validation experiments conducted on various LLMs using two different training datasets (Alpaca-GPT4 and CoT-Collection). Four different LLMs were used, and each was fine-tuned using two different methods (LoRA and MoLoRA) with two different inference modes (Vanilla and TAIA). The performance is evaluated across seven different downstream tasks assessing reasoning and knowledge capabilities. The table highlights the optimal performance achieved by TAIA in most scenarios.

This table presents the results of validation experiments conducted on seven downstream tasks using four different base language models (LLMs) and two fine-tuning techniques (LoRA and MoLoRA). The experiments are performed using two different training corpora (Alpaca-GPT4 and CoT-Collection). The table shows the performance of the baseline model (no fine-tuning), vanilla fine-tuning, and TAIA across various evaluation metrics. The bold values highlight the optimal performance for each subgroup of models, datasets, and fine-tuning methods. The underlined values show suboptimal results, while TAIA generally shows superior results across a wide range of tasks and models.

This table presents the results of validation experiments conducted on seven different downstream tasks (MATH, BBH, CQA, LogiQA, SVAMP, MMB, and MMLU) using four different base LLMs (Qwen1.5-1.8B, Qwen1.5-7B, LLaMA2-7B, and LLaMA3-8B). Two different training datasets (Alpaca-GPT4 and CoT-Collection) and two different fine-tuning methods (LoRA and MoLoRA) were used. The table compares the performance of the vanilla fine-tuning method with TAIA. Bold values indicate the best performing method for each subgroup, while underlined values indicate the second-best performing method. The results show TAIA generally achieves better fine-tuning results.

This table presents the results of validation experiments conducted using two different training corpora (Alpaca and CoT-Collection) and four different base LLMs (Qwen1.5-1.8B, Qwen1.5-7B, LLaMA2-7B, and LLaMA3-8B). It shows the performance of various fine-tuning methods (vanilla fine-tuning, LoRA, and MoLoRA) and TAIA on seven downstream tasks across different categories (Reasoning, Knowledge, and Math). The table helps to demonstrate the effectiveness and robustness of TAIA across various model sizes and fine-tuning techniques, particularly when dealing with limited or mismatched data.

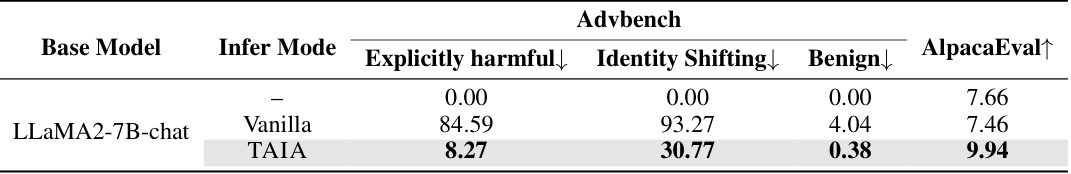

This table presents the results of a red-teaming experiment comparing TAIA and vanilla fine-tuning methods. The experiment aimed to evaluate the robustness of the methods against adversarial attacks. The results show that TAIA, in comparison to vanilla fine-tuning, resulted in lower attack success rates across different types of attacks. This indicates that TAIA is more effective in filtering out harmful features and improving the safety and helpfulness of the language model.

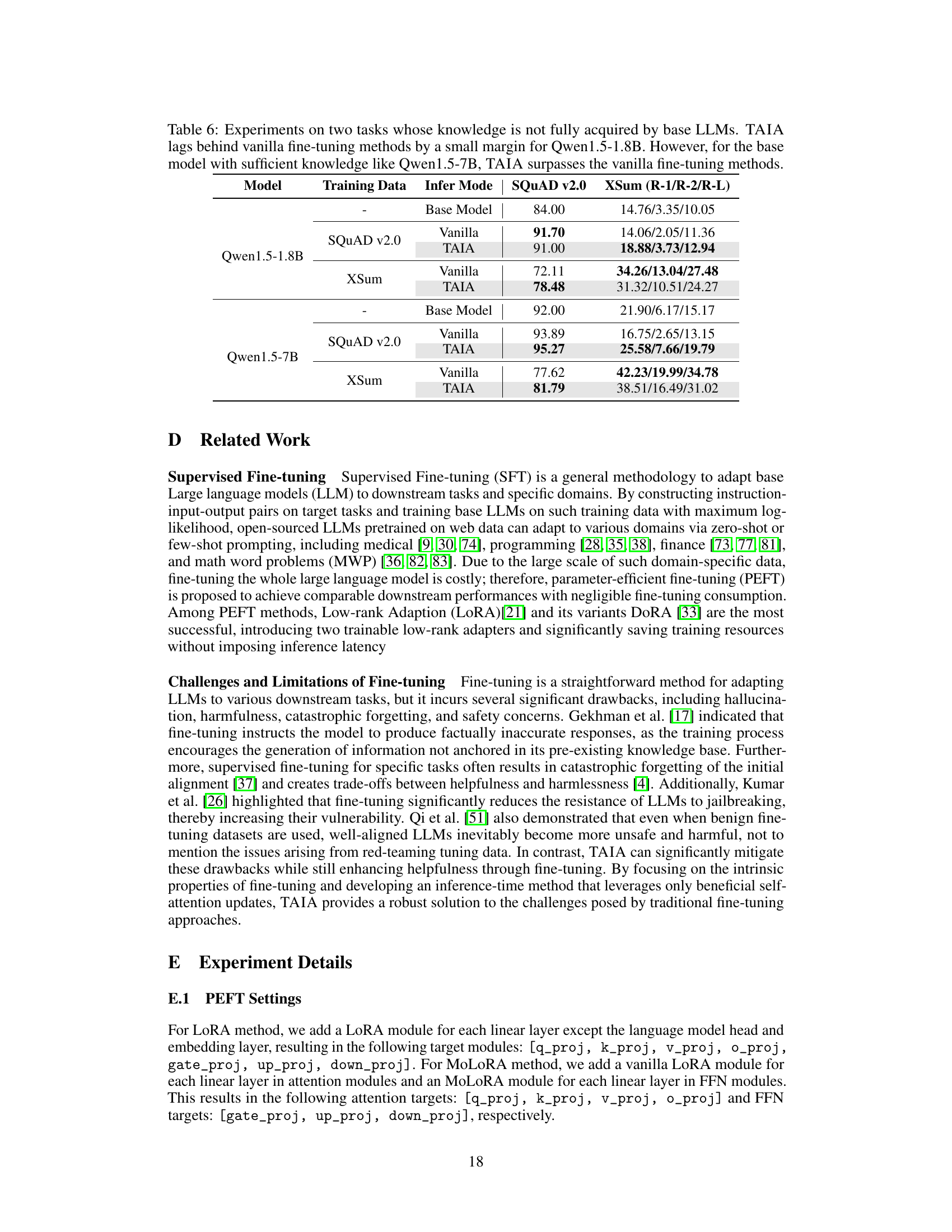

This table compares the performance of vanilla fine-tuning and TAIA on two tasks (SQUAD v2.0 and XSum) where the base LLMs may not have sufficient knowledge. It shows that while TAIA sometimes slightly underperforms vanilla fine-tuning on smaller models, it significantly outperforms vanilla fine-tuning on larger models where the base models already have a good understanding of the tasks. This highlights TAIA’s effectiveness when the base model already possesses relevant knowledge.

This table presents the results of validation experiments comparing different fine-tuning methods (Vanilla, LoRA, MoLoRA, and TAIA) on seven downstream tasks using four different base LLMs (Qwen1.5-1.8B, Qwen1.5-7B, LLaMA2-7B, LLaMA3-8B) and two training datasets (Alpaca-GPT4, CoT-Collection). The table shows the performance (accuracy) of each method on each task, highlighting the best-performing method (in bold) for each LLM and dataset combination. The results demonstrate that TAIA often outperforms other methods, particularly when fine-tuning on data that is not perfectly aligned with the test set.

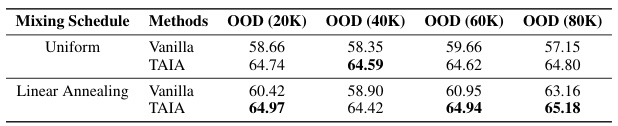

This table presents an ablation study on the impact of different out-of-distribution (OOD) data mixing strategies on the performance of vanilla LoRA tuning and the proposed TAIA method. Two data mixing schedules are compared: uniform mixing and linear annealing. For each schedule, the table shows the performance of both methods across four different ratios of OOD data (20K, 40K, 60K, 80K). The results demonstrate that TAIA consistently outperforms vanilla LoRA under both mixing strategies and across all OOD data ratios.

This table presents an ablation study on the impact of different out-of-distribution (OOD) data mixing strategies on the performance of TAIA and vanilla LoRA tuning. Two data mixing strategies are compared: uniform and linear annealing. The results show the performance of each method across various OOD data ratios (20k, 40k, 60k, 80k).

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing the performance of TAIA and vanilla LoRA tuning under different out-of-distribution (OOD) data mixing strategies. Two strategies were used: uniform mixing and linear annealing. The results show that TAIA consistently outperforms vanilla LoRA tuning across various OOD data ratios, regardless of the mixing strategy.

This table presents the results of validation experiments conducted using two different training corpora (Alpaca-GPT4 and CoT-Collection) and four different base LLMs (Qwen1.5-1.8B, Qwen1.5-7B, LLaMA2-7B, LLaMA3-8B). The experiments evaluated performance across seven downstream tasks, comparing vanilla fine-tuning (Vanilla), LoRA, and MoLoRA against TAIA. Results are shown in terms of average accuracy across the seven tasks, with bold indicating the best performing method in each subgroup and underlined indicating suboptimal performance.

This table presents the results of validation experiments conducted on seven different downstream tasks using four distinct LLMs (Qwen1.5-1.8B, Qwen1.5-7B, LLaMA2-7B, LLaMA3-8B). Two different fine-tuning methods (LoRA and MoLoRA) and two training corpora (Alpaca and CoT Collection) were employed. The table displays the average accuracy across these tasks for each model, fine-tuning method, and training corpus, comparing the performance of vanilla fine-tuning with the proposed TAIA method. Bold values indicate the best performance within each subgroup, and underlined values show the second-best. The table highlights the consistent superiority of TAIA across various settings.

This table presents the results of validation experiments on seven downstream tasks using two training datasets (Alpaca-GPT4 and CoT-Collection) and four different base LLMs (Qwen1.5-1.8B, Qwen1.5-7B, LLaMA2-7B, and LLaMA3-8B). It compares the performance of three fine-tuning methods: LoRA, MoLoRA, and TAIA. For each model and method, the table shows accuracy scores for each task. The bold values indicate the best-performing method for each group of experiments. The table demonstrates that TAIA generally outperforms other fine-tuning methods across different models and datasets.

This table presents the results of validation experiments conducted to assess the performance of the TAIA method across different models, fine-tuning methods, and datasets. The experiments used four different base LLMs and two fine-tuning techniques (LoRA and MoLoRA) and evaluated the performance on seven downstream tasks. The table highlights which methods achieved optimal and suboptimal results. Note that the TAIA approach frequently yields the best performance.

This table presents the results of validation experiments conducted to assess the performance of the TAIA method. Four different base LLMs were fine-tuned using two different training corpora and two fine-tuning methods (LoRA and MoLoRA). The performance of each model is evaluated across seven downstream tasks: MATH, BBH, CQA, LogiQA, SVAMP, MMB, and MMLU. The table highlights the best and second-best performing methods for each model-corpus-method combination. The results show that the TAIA method generally achieves optimal or near-optimal performance.

This table presents the results of validation experiments conducted using two training corpora (Alpaca-GPT4 and CoT-Collection) and four different base LLMs (Qwen1.5-1.8B, Qwen1.5-7B, LLaMA2-7B, and LLaMA3-8B). The experiments evaluate the performance of three fine-tuning methods (Vanilla, LoRA, and MoLoRA) along with TAIA across seven downstream tasks (MATH, BBH, CQA, LogiQA, SVAMP, MMB, and MMLU). The table highlights the best and second-best performing methods for each model and task, demonstrating TAIA’s superiority in achieving optimal fine-tuning results.

Full paper#