↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Deep learning models, especially Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), are increasingly deployed in critical applications like risk assessment and fraud detection. However, real-world changes necessitate model updates after deployment. Existing model editing techniques often fail to maintain overall accuracy while correcting specific errors, especially in complex GNNs where information propagates across nodes. This paper identifies a significant issue: gradient inconsistency between target and training nodes during model editing. Direct fine-tuning leads to decreased performance on the training data.

To solve this, the authors propose Gradient Rewiring (GRE). GRE first stores “anchor gradients” from the training data to maintain local performance. Then, it re-wires the gradient for the target node, ensuring that edits do not negatively impact the training data. Extensive experiments across different GNN architectures and datasets confirm that GRE effectively addresses model editing challenges, outperforming existing methods in accuracy and robustness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on editable graph neural networks (GNNs). It addresses the critical issue of maintaining model accuracy after editing, which is vital for real-world applications where models must adapt to changes. The proposed Gradient Rewiring (GRE) method offers a novel solution to this problem, potentially impacting the fields of recommendation systems, risk assessment, and graph analytics. The research opens up new avenues for research into more robust and adaptable GNNs.

Visual Insights#

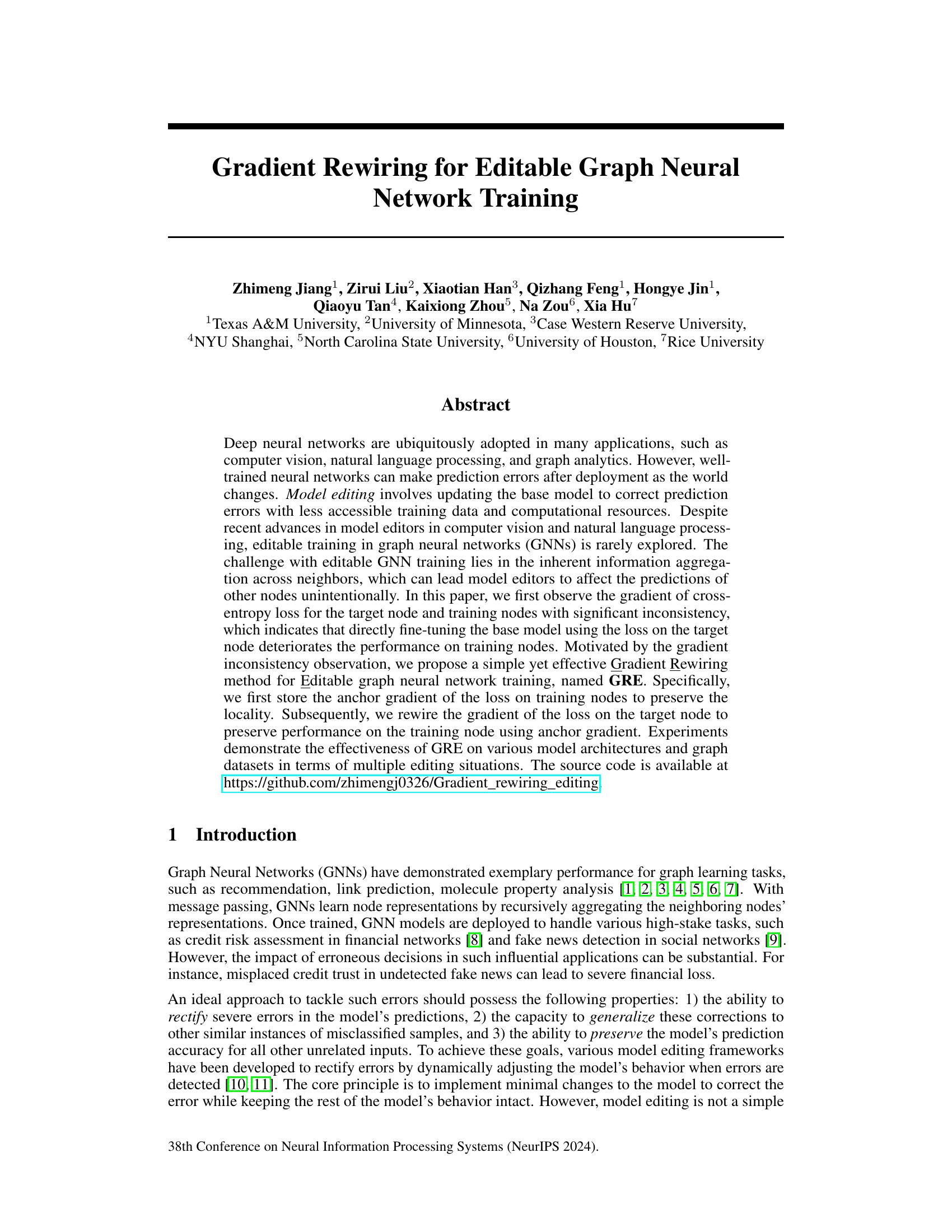

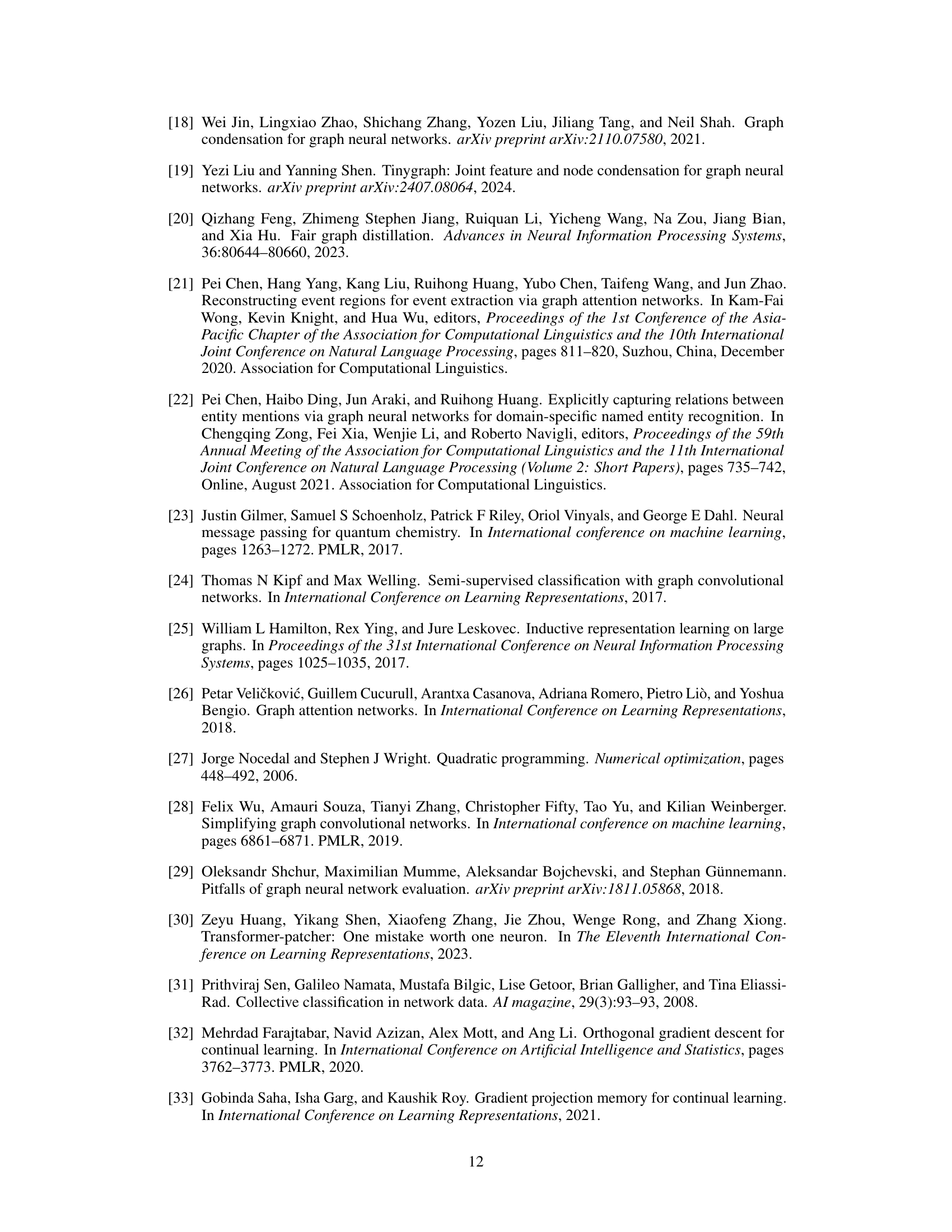

This figure shows the results of preliminary experiments that motivate the gradient rewiring method. The top row displays the RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) between the gradients of the cross-entropy loss for training nodes and the target node across different model architectures (GCN, GraphSAGE, and MLP). The middle row shows the cross-entropy loss over the training datasets during model editing, and the bottom row shows the cross-entropy loss on the target sample. The results illustrate the significant gradient inconsistency between training and target nodes, highlighting the challenges of directly fine-tuning the base model with the target loss.

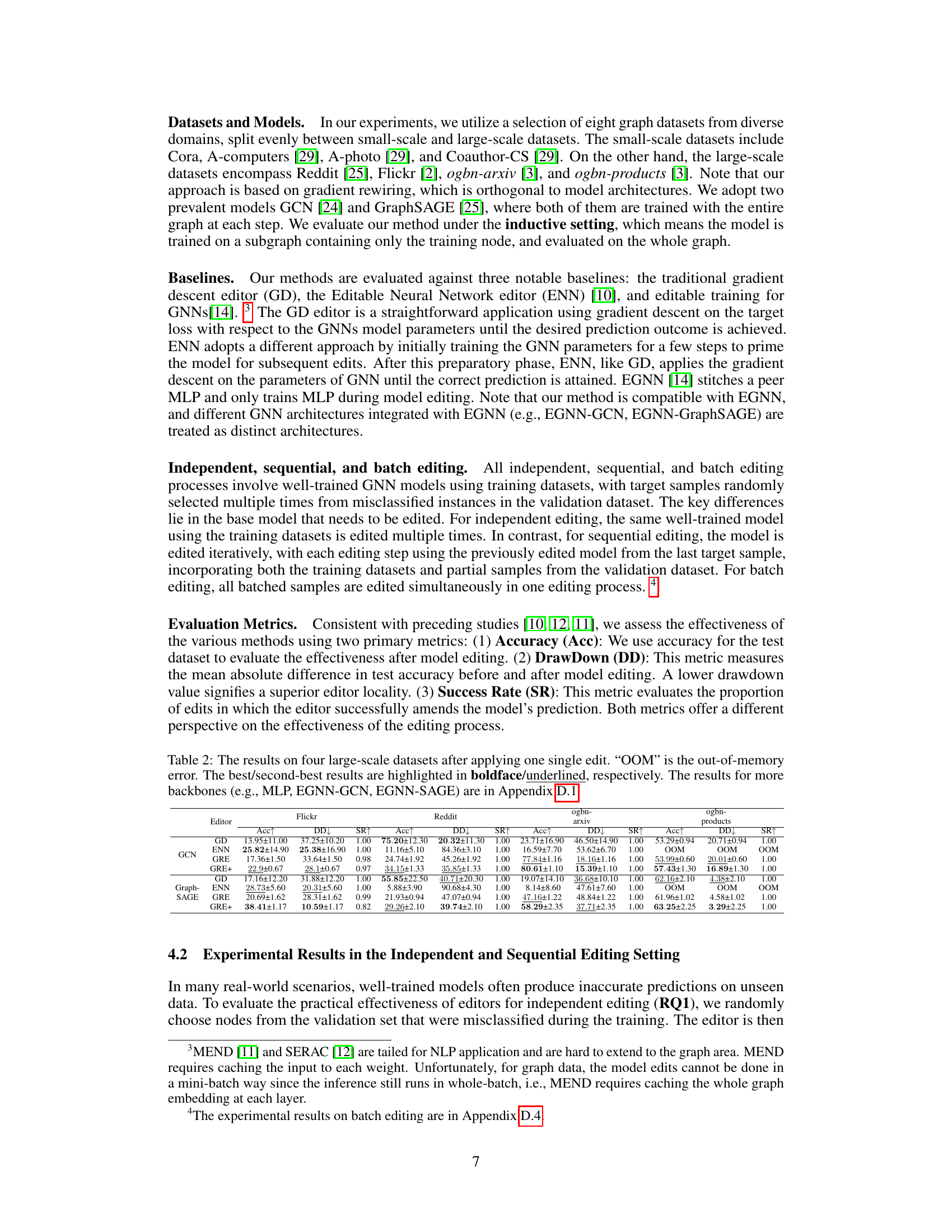

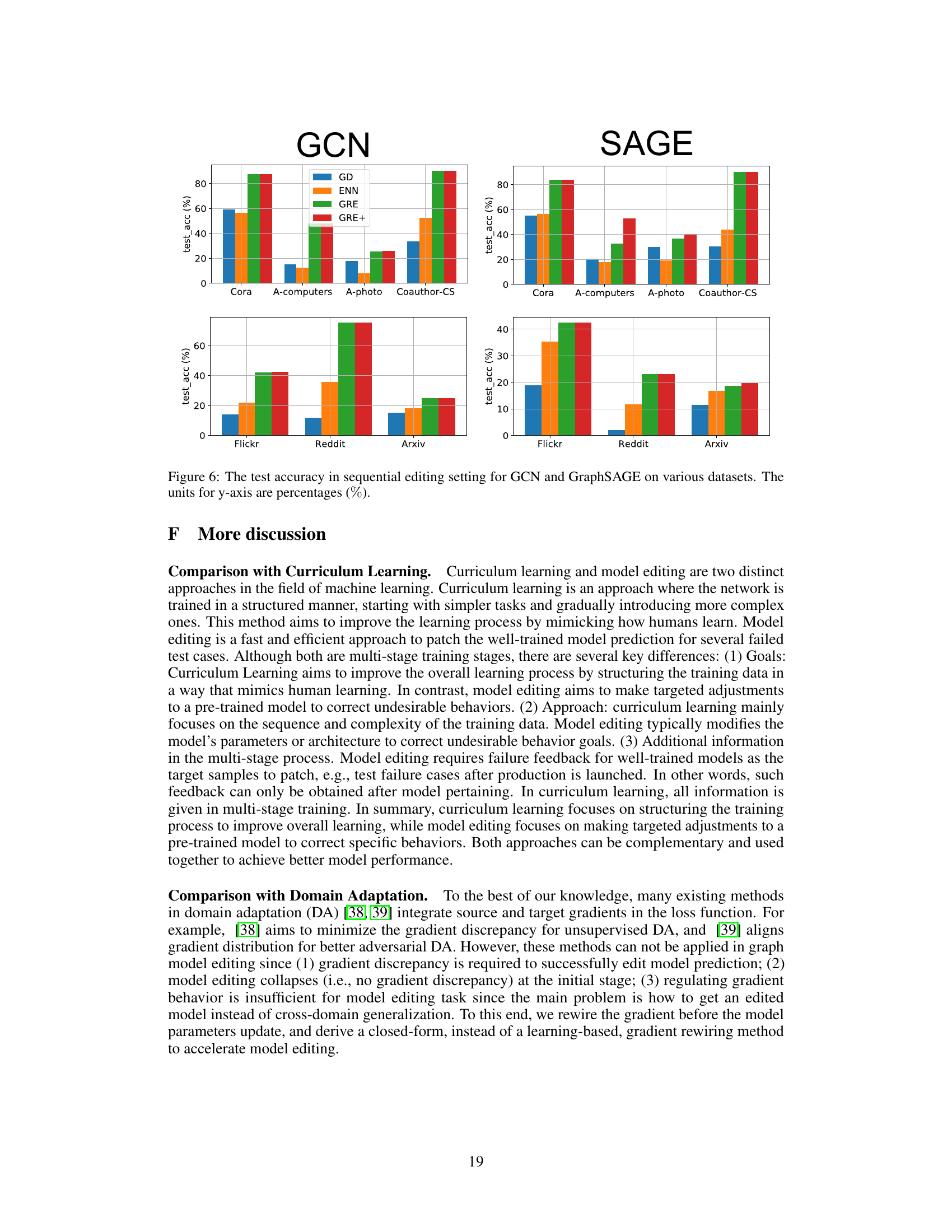

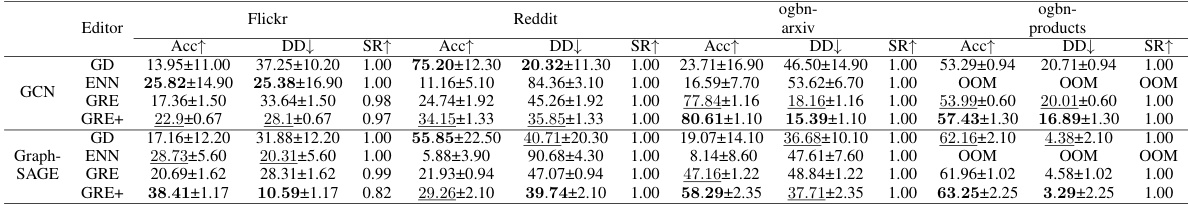

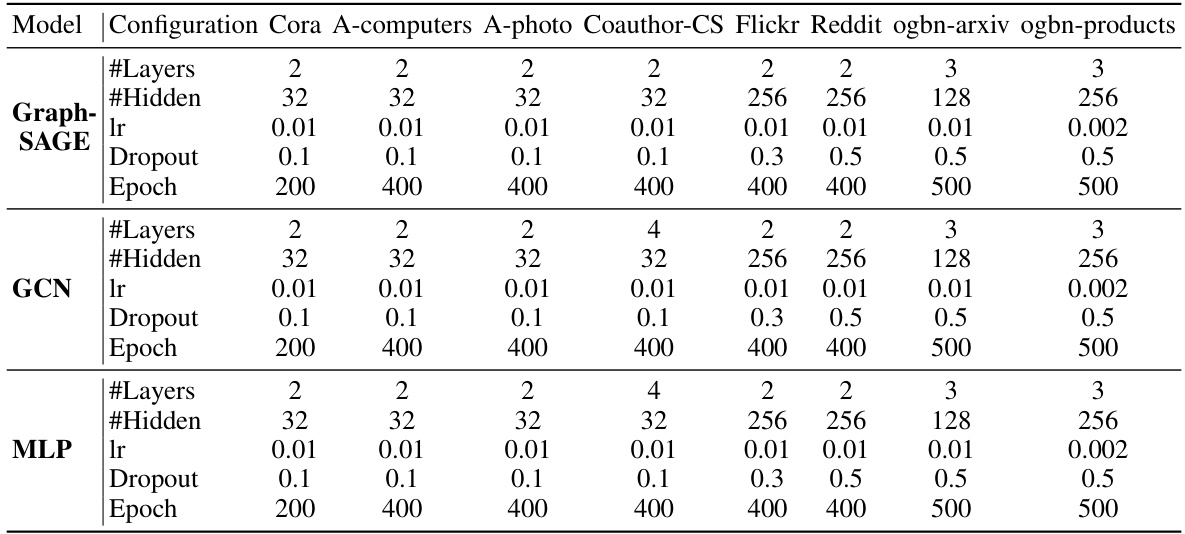

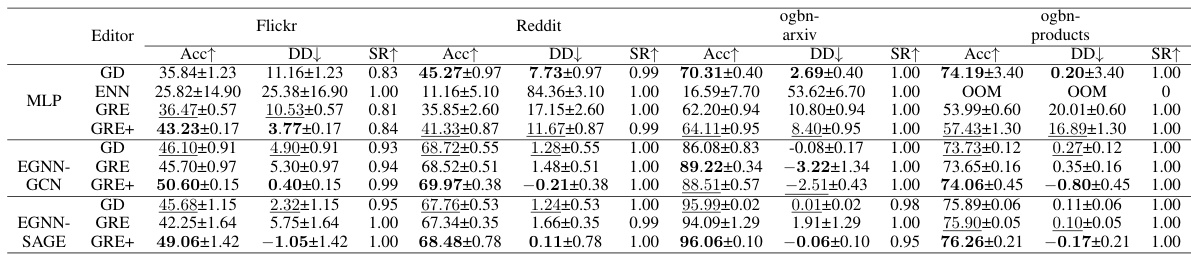

This table presents the results of applying a single edit to four small-scale datasets using different model editing techniques. The results are averaged over 50 independent edits. Key metrics include the edit success rate (SR), test accuracy after editing (Acc), and test accuracy drawdown (DD). Out-of-memory (OOM) errors are noted where applicable. The best and second-best results are highlighted.

In-depth insights#

Grad. Rewiring Edits#

The concept of ‘Grad. Rewiring Edits’ in the context of editable graph neural networks (GNNs) introduces a novel approach to address the challenge of gradient inconsistency during model editing. Directly fine-tuning a GNN based on the loss of a target node often negatively impacts the performance on other training nodes due to the inherent information aggregation in GNNs. This method addresses this by preserving the ‘anchor gradient’ of training nodes, essentially storing the original gradient direction to maintain local performance. Then, the gradient of the target node loss is ‘rewired’ using this stored anchor gradient, ensuring that edits do not unintentionally disrupt the performance of the training nodes. This approach is particularly relevant to scenarios where high-stake decisions are involved, such as in financial risk assessment or fake news detection, where even small unintended alterations in model behavior could be significant. The efficacy of this approach hinges on the accuracy of the pre-stored anchor gradient, which necessitates careful consideration of potential long-term drift or mismatches.

GNN Editing Limits#

GNN editing, while showing promise in correcting model errors, faces inherent limitations stemming from the interconnected nature of graph data. Unlike image or text data, changes in a single node’s representation within a GNN ripple through its neighbors and potentially the entire graph, leading to unintended consequences and reduced model accuracy. This challenge is compounded by the gradient inconsistency often observed between the target node being edited and the training nodes, hindering the efficacy of direct fine-tuning. Gradient-based methods alone may struggle to address these issues, highlighting the need for more sophisticated approaches that consider the global impact of local edits. Therefore, further research focusing on preserving locality and managing gradient flow during editing is crucial to unlock the full potential of editable GNNs.

GRE+ Enhancements#

The GRE+ enhancements section would delve into the improvements made upon the basic GRE method. This likely involves addressing GRE’s limitations, particularly concerning the potential for instability and performance degradation on certain training subsets when updating a model based solely on target node loss. GRE+ might introduce a more robust optimization strategy by incorporating multiple loss constraints, perhaps splitting the training data into subsets and ensuring no subset’s loss increases post-editing. This approach aims to preserve locality, preventing unintended ripple effects across the entire graph during model editing. The enhancements would also detail how the anchor gradients are utilized in this multi-constraint setting and potentially present a more sophisticated method for re-weighting or combining gradients based on their consistency or significance to model performance. Experiments demonstrating GRE+’s superior stability and generalization capabilities compared to GRE and baseline methods (e.g. GD, ENN) across various model architectures and datasets would form a critical part of this section, highlighting the practical advantages of the refined approach.

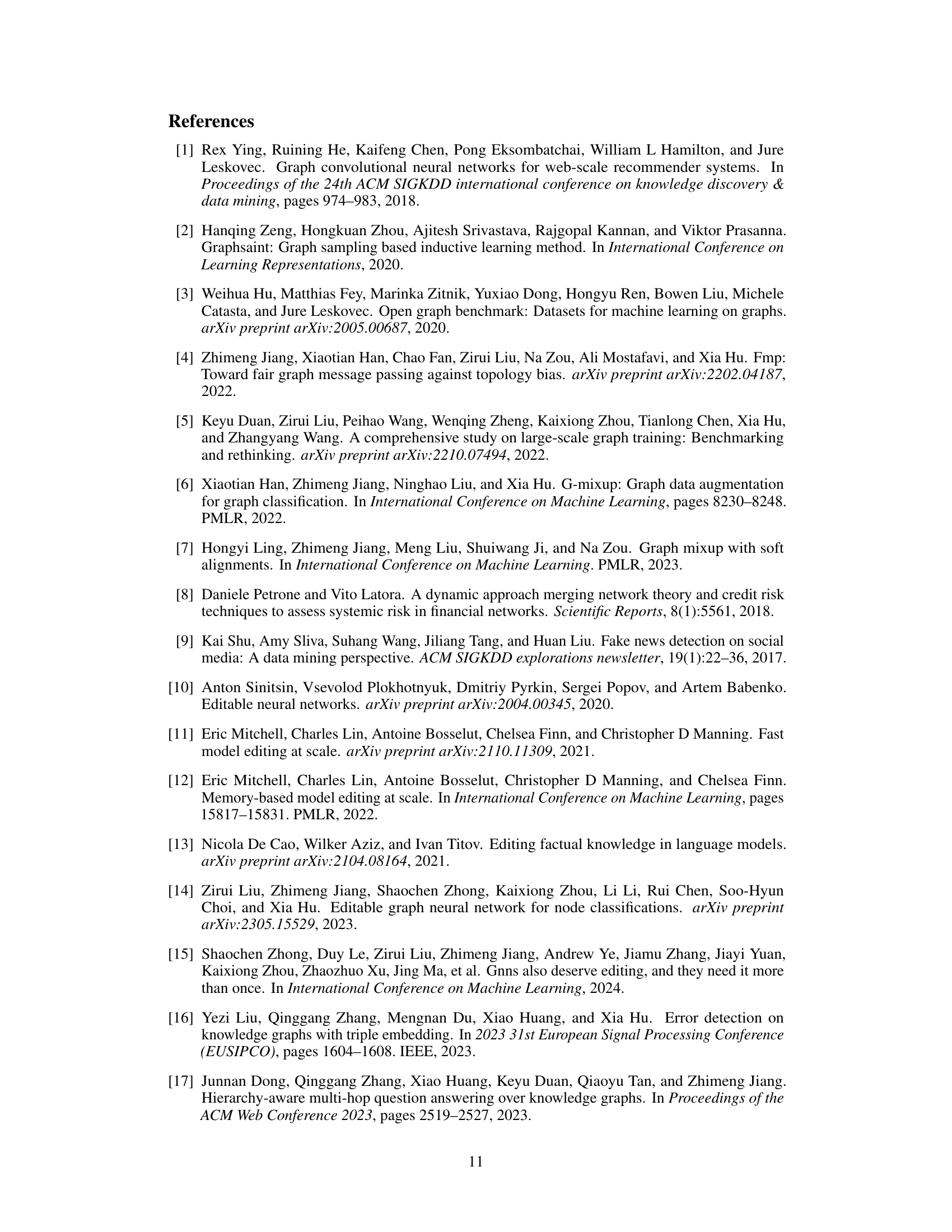

Hyperparameter λ#

The hyperparameter \lambda controls the balance between correcting the target node’s prediction and preserving the performance on training nodes. A higher \lambda prioritizes minimizing the gradient discrepancy, thus maintaining training node performance but potentially sacrificing target node accuracy. Conversely, a lower \lambda prioritizes target node correction. The optimal value of \lambda is likely dataset-dependent and should be determined empirically. The experiments indicate that the model’s performance is relatively insensitive to the specific value of \lambda, suggesting robustness to its selection, although there might be minor differences across various datasets and model architectures. Further investigation into the impact of \lambda on different graph structures and sizes could provide deeper insights and potential improvements to the gradient rewiring approach. This hyperparameter’s influence underscores the need for a careful balance between correction and preservation during editable GNN training.

Future GNN Editing#

Future research in GNN editing should prioritize addressing the inherent challenges of information propagation within graph structures. Current methods often unintentionally alter the predictions of nodes beyond the target, highlighting the need for more sophisticated approaches. Gradient-based methods show promise but could be refined for better locality preservation. Developing methods that learn to anticipate and mitigate the ripple effect of edits would be a significant advance. Exploring alternative loss functions tailored to GNN editing could offer improved performance. Finally, research should focus on scalability, enabling efficient editing of large, complex graphs. Furthermore, investigation of adaptive editing strategies, which can dynamically adjust the editing process based on the graph’s topology and node features, is vital. Ultimately, the goal is to develop robust and efficient editing techniques that can easily adapt to the ever-changing nature of real-world graph data.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows three subplots visualizing the results of a preliminary experiment on model editing. The top subplot shows the RMSE distance between gradients of cross-entropy loss for training data and the target sample. The middle subplot shows the training loss, and the bottom subplot shows the target loss during model editing for different architectures (GCN, GraphSAGE, and MLP). This experiment highlights inconsistencies in gradients that motivate the proposed gradient rewiring method.

This figure displays the results of preliminary experiments that compare the gradients of cross-entropy loss for different models (GCN, GraphSAGE, MLP) over both the training datasets and the target sample. The top section (a) shows the RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) distance between these gradients, illustrating their inconsistency. The middle (b) and bottom (c) sections show the training loss and target loss, respectively, during the model editing process. The inconsistency in gradients motivates the introduction of the GRE method proposed in the paper.

This figure presents a comparison of gradients and loss functions before and after model editing. It demonstrates that there is a large discrepancy between the gradients of cross-entropy loss over training datasets and the target sample, especially for GCN and GraphSAGE. The middle and bottom plots shows that direct fine-tuning using only target node loss deteriorates the performance on training nodes. This observation motivates the gradient rewiring approach proposed in the paper.

This figure presents the results of a preliminary experiment designed to show the gradient discrepancy between training and target nodes in different GNN architectures. The top row shows RMSE (root mean squared error) of the gradient difference between training and target samples. The middle row shows the training loss and the bottom row shows the target loss. The experiment demonstrates that there is a significant difference in gradients between training and target nodes, highlighting the challenges of directly fine-tuning the base model using target node loss.

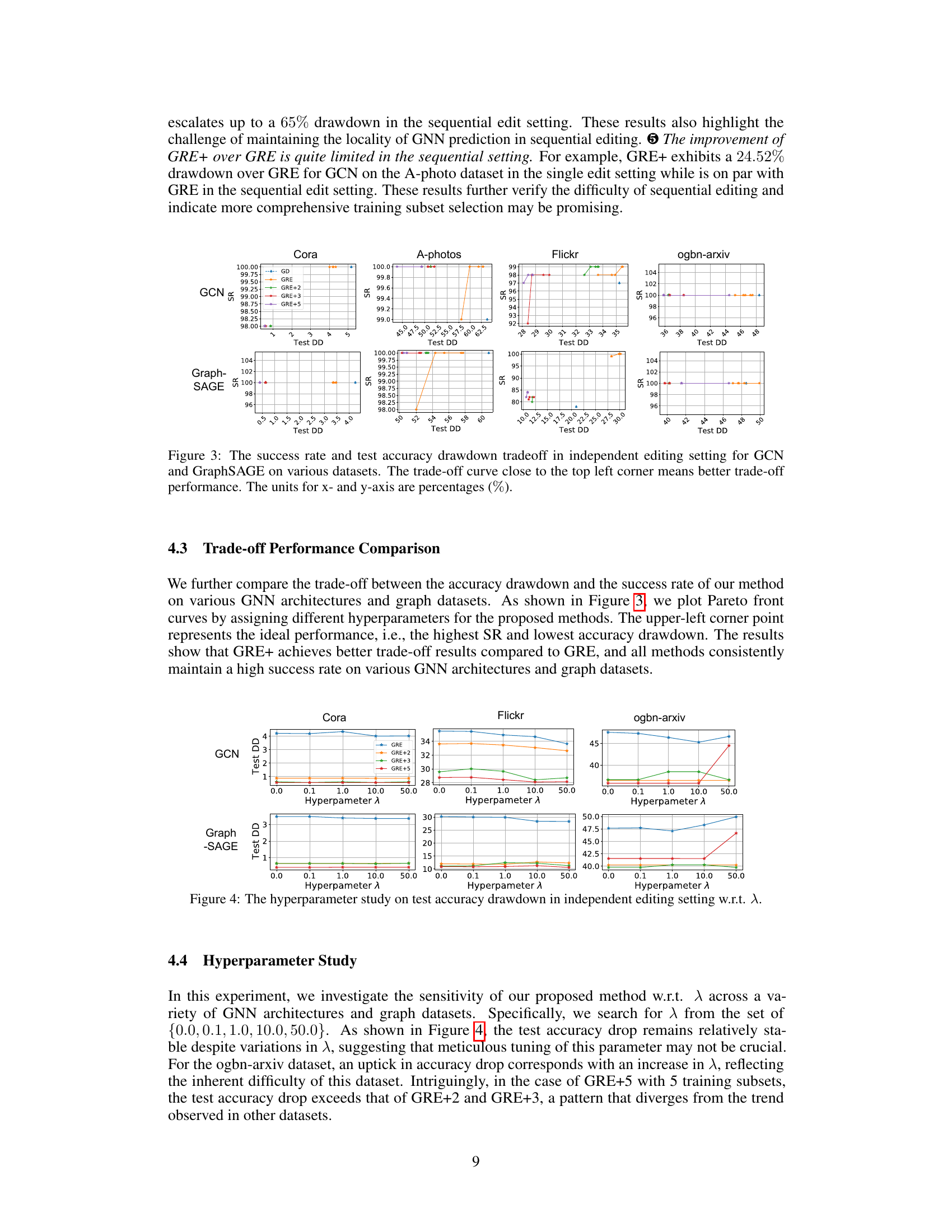

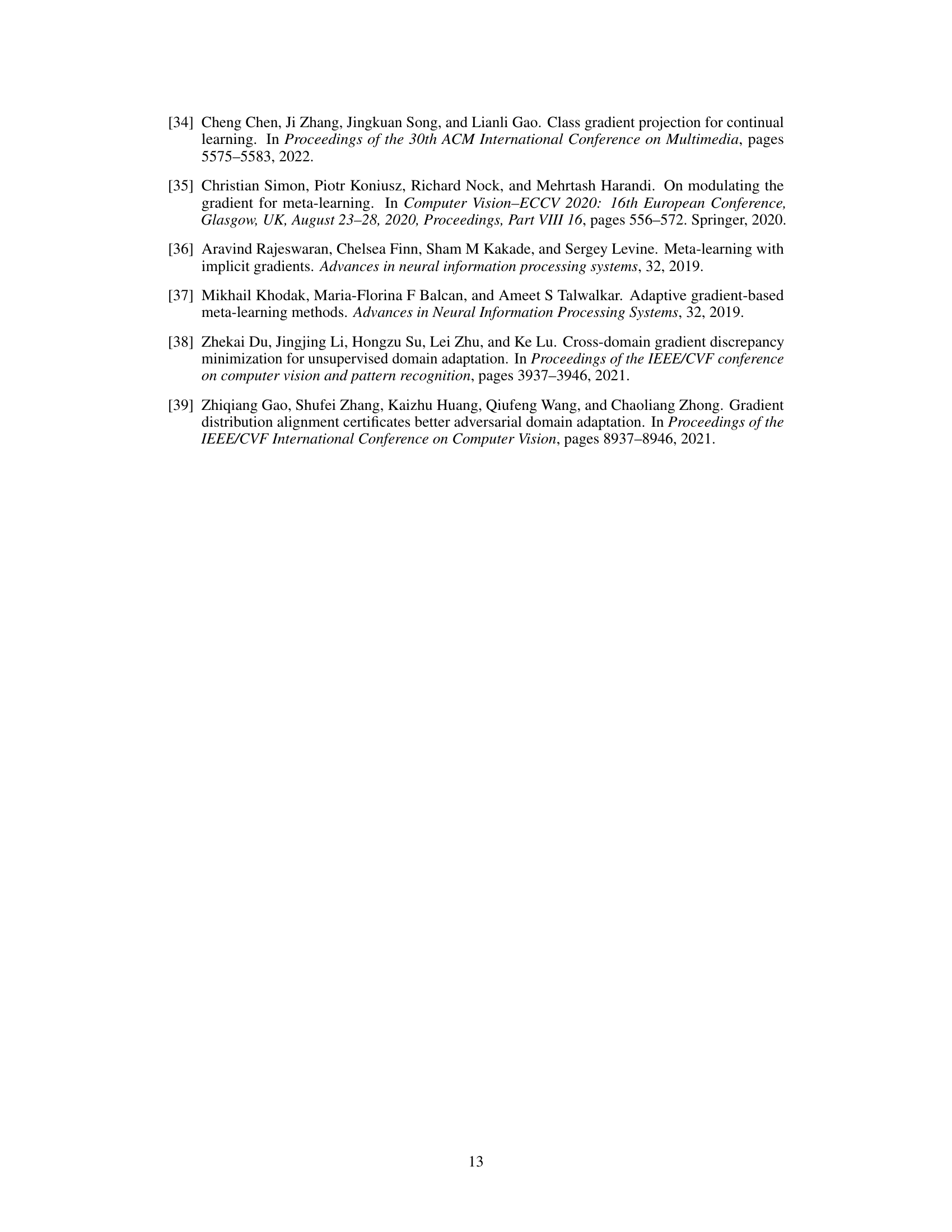

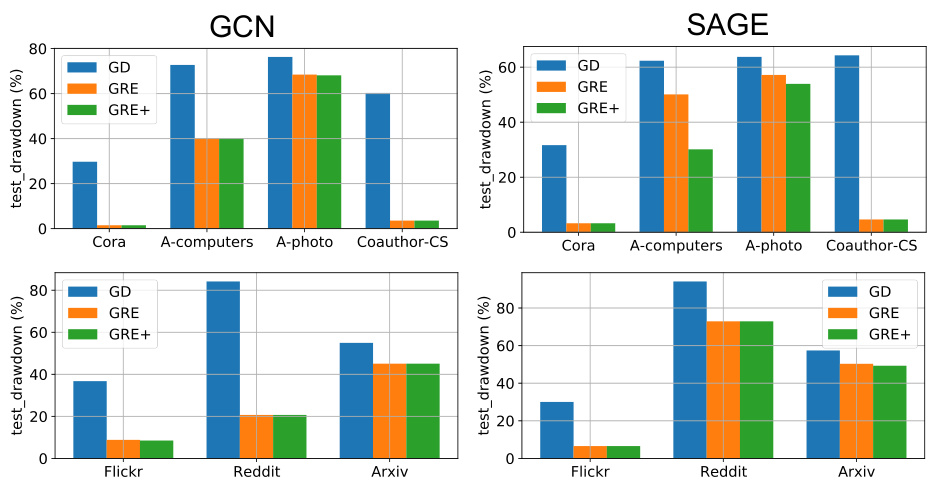

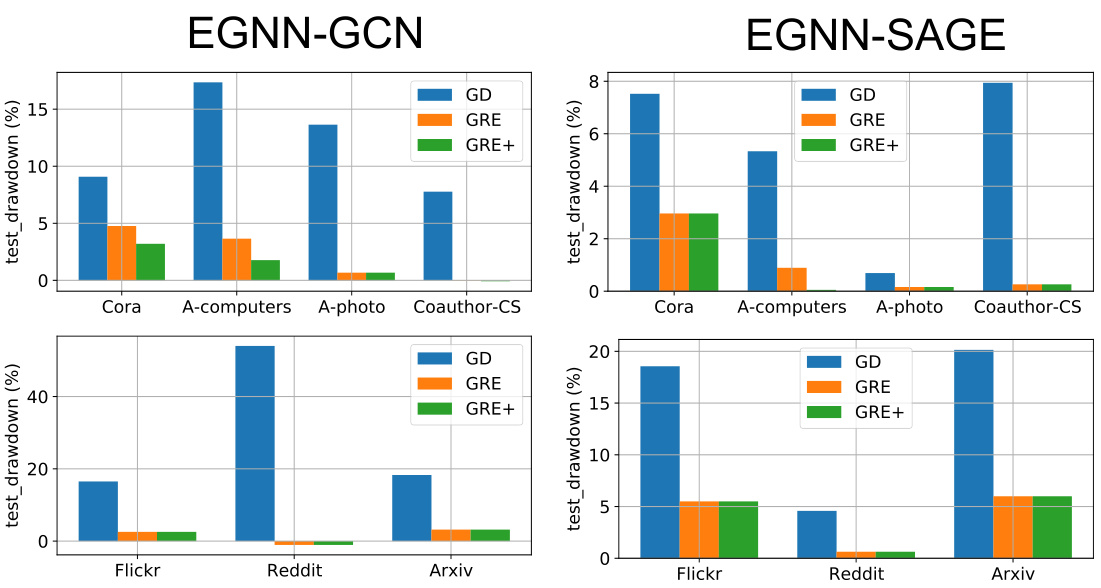

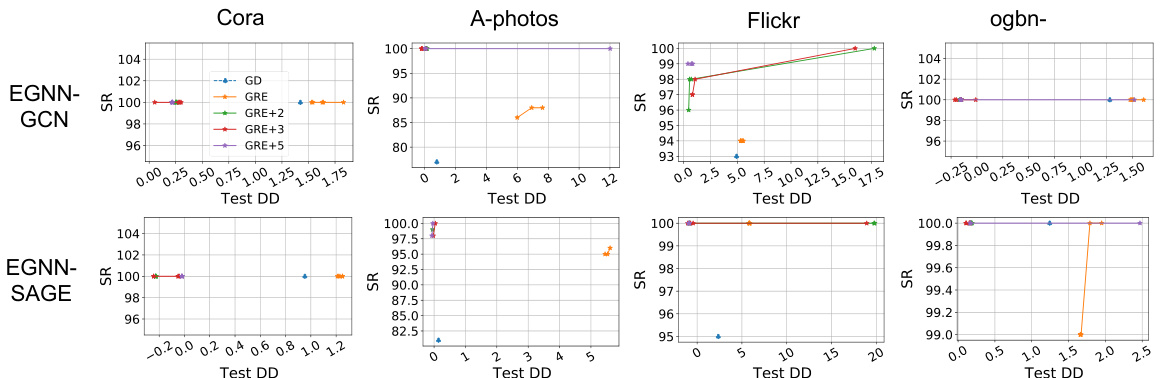

This figure displays the test accuracy drawdown for both GCN and GraphSAGE models across various datasets in a sequential editing setting. The x-axis represents the datasets (Cora, A-computers, A-photo, Coauthor-CS, Flickr, Reddit, Arxiv), while the y-axis represents the test accuracy drawdown (in percentages). The figure demonstrates the performance of different model editing approaches (GD, GRE, and GRE+) in maintaining test accuracy across multiple sequential edits. Lower drawdown values indicate better performance in preserving test accuracy during the editing process.

More on tables

This table presents the results of applying a single edit to four small-scale datasets. The results are averaged over 50 independent edits and show the success rate (SR), test accuracy (Acc) after editing, and test accuracy drawdown (DD). OOM indicates that the experiment ran out of memory.

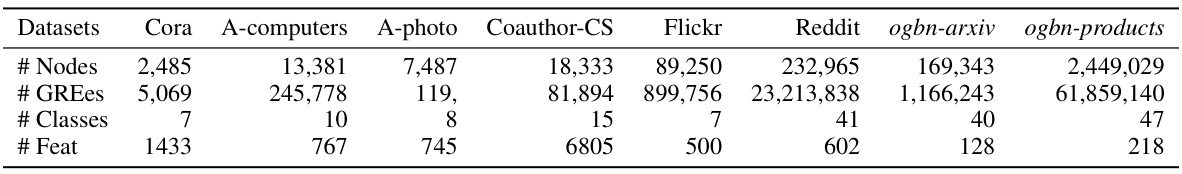

This table presents the key statistics of eight graph datasets used in the node classification experiments of the paper. For each dataset, it lists the number of nodes, the number of edges, the number of classes, and the dimensionality of the node features. The datasets vary significantly in size and characteristics, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed methods across diverse scenarios.

This table presents the results of applying a single model edit to four small graph datasets. The results are averaged over 50 independent trials for each dataset and model architecture. Key metrics reported include the success rate of the edit (SR), the accuracy after editing (Acc), and the test accuracy drawdown (DD). Out-of-memory (OOM) errors are also noted.

This table presents the results of applying a single model edit to four small graph datasets (Cora, A-photo, Coauthor-CS, and A-computers). The results are averaged over 50 independent trials. Key metrics reported include the success rate of the edit (SR), the increase in test accuracy after editing (Acc↑), and the test accuracy drawdown (DD). Drawdown measures the difference in test accuracy before and after editing, representing the impact of the edit on unrelated data points. The “OOM” designation indicates that the experiment ran out of memory.

This table presents the results of applying a single edit to four small-scale graph datasets. The results are averaged over 50 independent trials. Key metrics reported include the edit success rate (SR), test accuracy after the edit (Acc), and the test accuracy drawdown (DD), representing the decrease in accuracy after the edit. The table highlights the best and second-best results for each model and dataset.

This table presents the results of applying a single edit to four small-scale graph datasets. For each dataset and model architecture (GCN, GraphSAGE, and MLP), it shows the average success rate (SR), the average accuracy increase (Acc↑), and the average test accuracy drawdown (DD) over 50 independent runs. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of various model editing techniques by comparing their impact on model performance after correcting a single misclassified sample.

This table presents the results of applying a single edit to four small-scale datasets. The results are averaged across 50 independent edits for each dataset and model. The table shows the success rate (SR), the increase in test accuracy (Acc↑), and the decrease in test accuracy (DD↓) after applying the edit using different model editing methods (GD, ENN, GRE, GRE+). OOM indicates that the experiment ran out of memory.

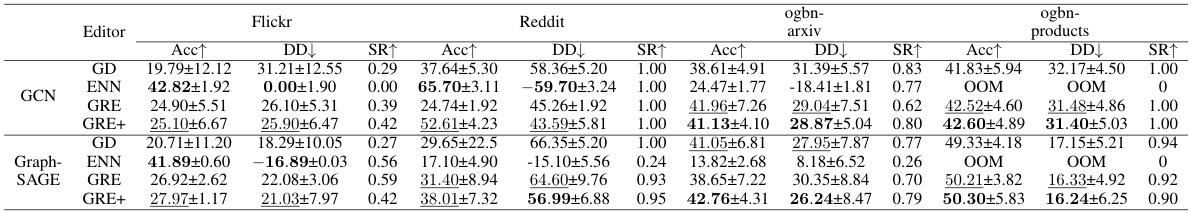

This table shows the edit time and peak memory usage for different model editing methods across four large-scale datasets (Flickr, Reddit, ogbn-arxiv, and ogbn-products). The methods compared include Gradient Descent (GD), Editable Neural Network (ENN), Gradient Rewiring (GRE), and Gradient Rewiring Plus (GRE+) with different hyperparameter settings (GRE+(2), GRE+(3), GRE+(5)). The ‘ET (ms)’ column represents the edit time in milliseconds, and ‘PM (MB)’ represents the peak memory usage in megabytes. ‘OOM’ indicates that the experiment ran out of memory.

Full paper#