↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Visualizing deep neural networks is crucial for understanding their inner workings. Recent advancements utilize piecewise affine functions for mesh extraction; however, non-linear positional encoding in modern neural surface representation learning introduces challenges for existing techniques. This necessitates new methods, especially as non-linear encodings enhance accuracy and speed.

This research focuses on trilinear interpolation as a positional encoding. It introduces an analytical mesh extraction method. The core contribution is a theoretical proof showing that, under eikonal constraints, hypersurfaces within trilinear regions transform into planes. This simplification enables precise mesh extraction. The proposed approach is validated empirically through experiments demonstrating both efficiency and accuracy, revealing a strong correlation between eikonal loss and hypersurface planarity.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

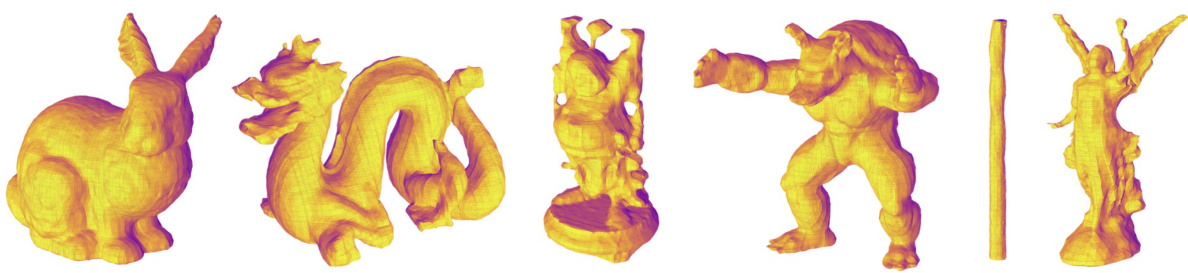

This paper is crucial for researchers in neural implicit surface representation and mesh extraction. It provides a novel theoretical framework and practical methodology for precise mesh extraction from piecewise trilinear networks, addressing challenges posed by non-linear positional encoding techniques. This work opens new avenues for visualizing and analyzing deep neural networks, improving our understanding of their geometry and decision boundaries, and has significant implications for various applications in computer graphics, computer vision, and AI.

Visual Insights#

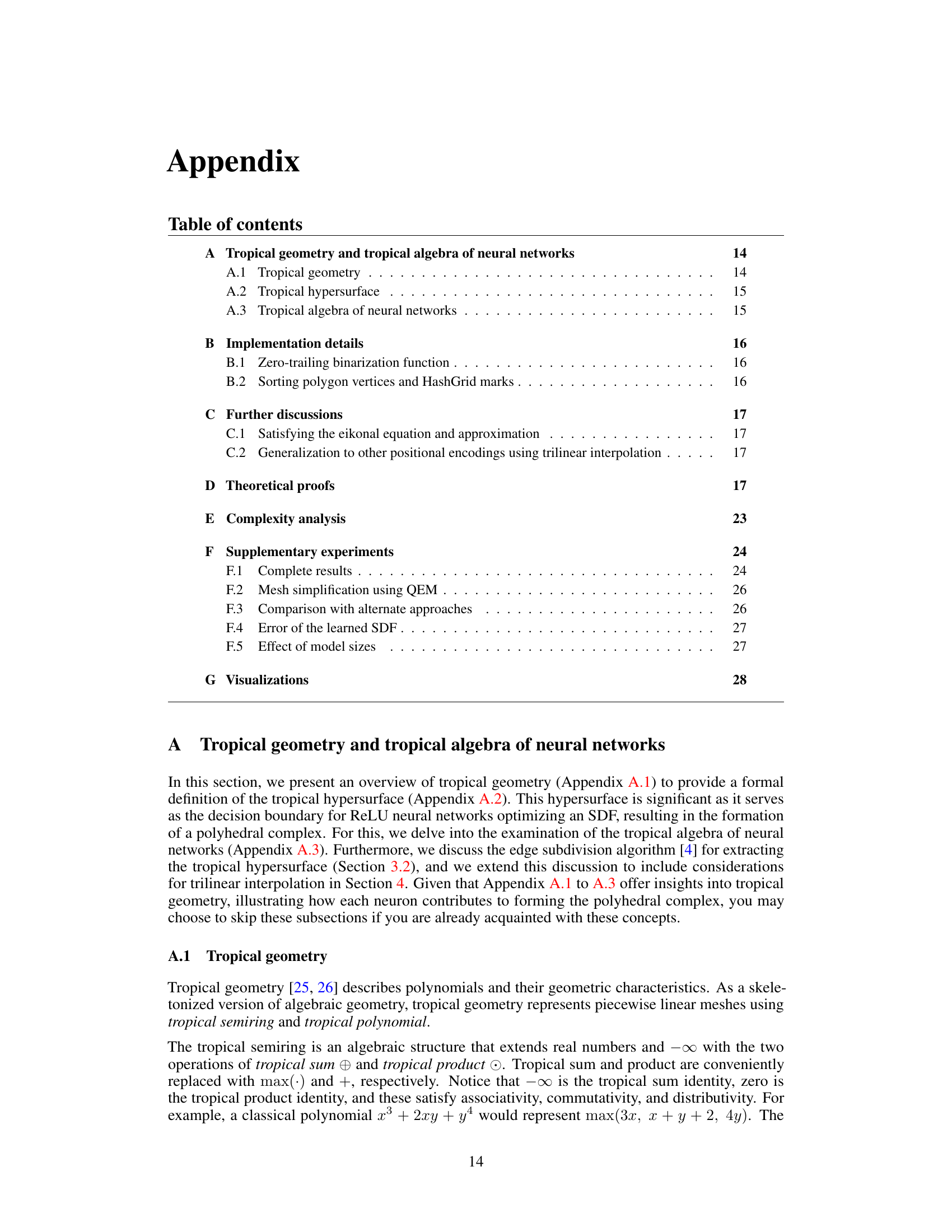

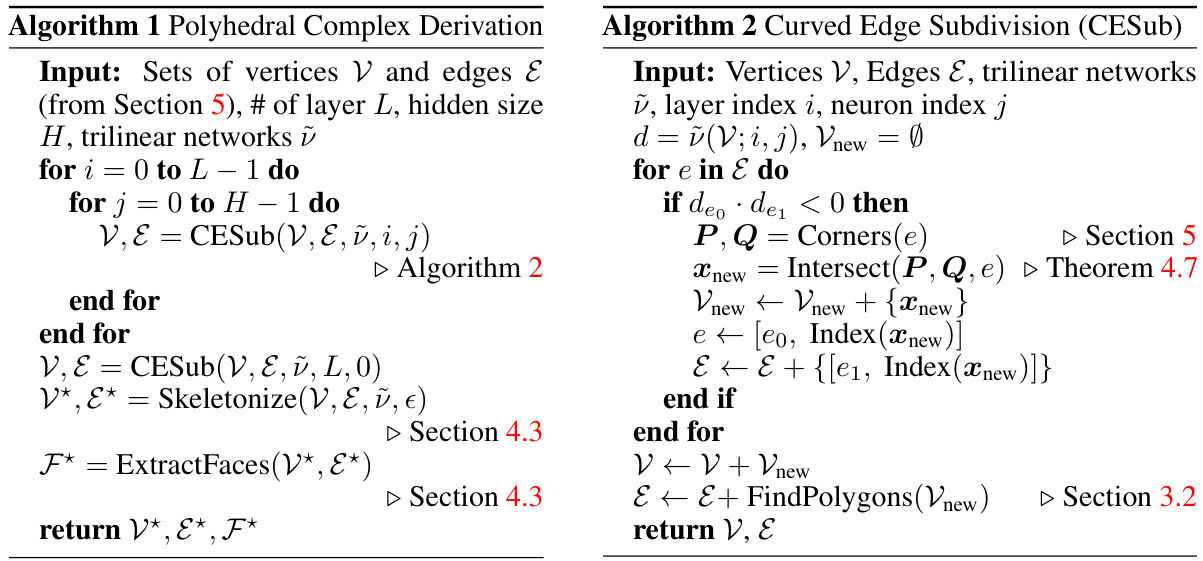

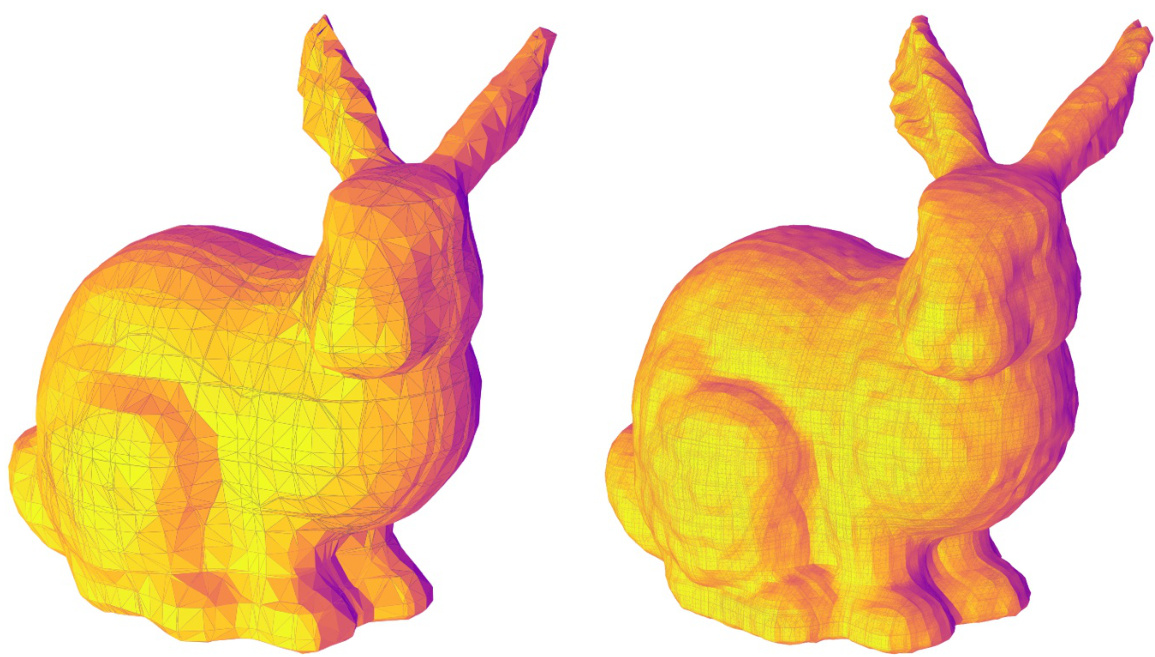

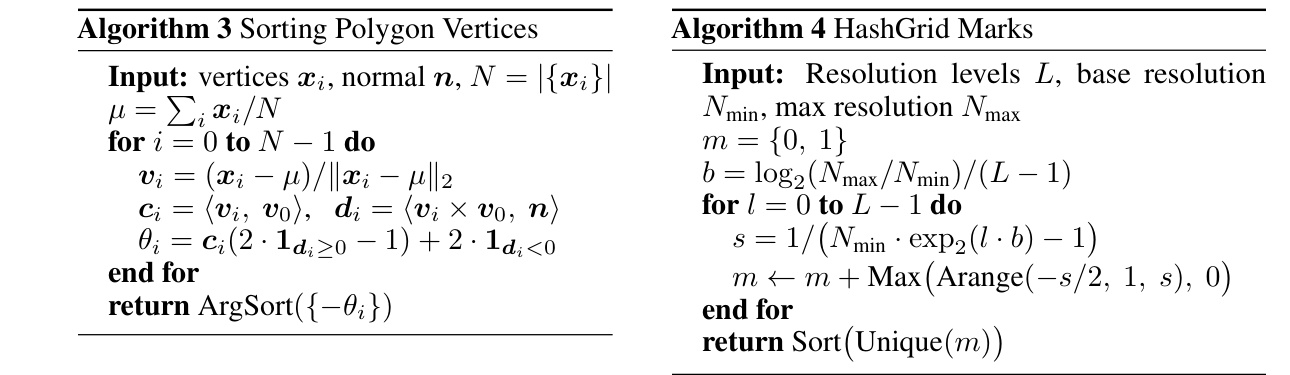

This figure illustrates the mesh extraction process from piecewise trilinear networks. It starts with a grid and progressively refines it through linear, bilinear, and trilinear subdivisions to accurately capture the curved surfaces. The process involves identifying intersecting polygons and using trilinear interpolation to approximate the intersection points.

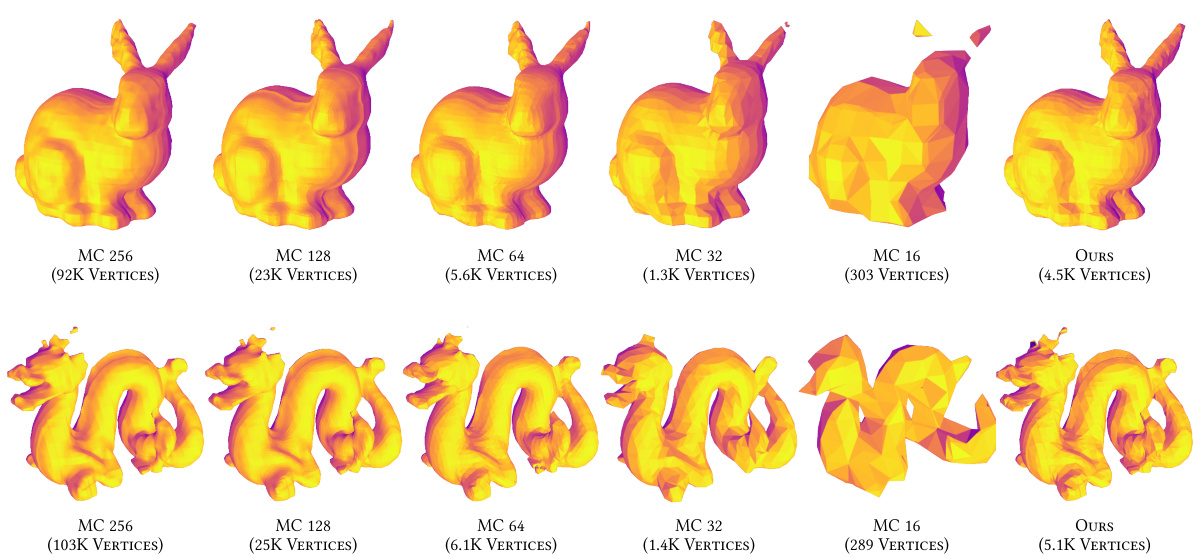

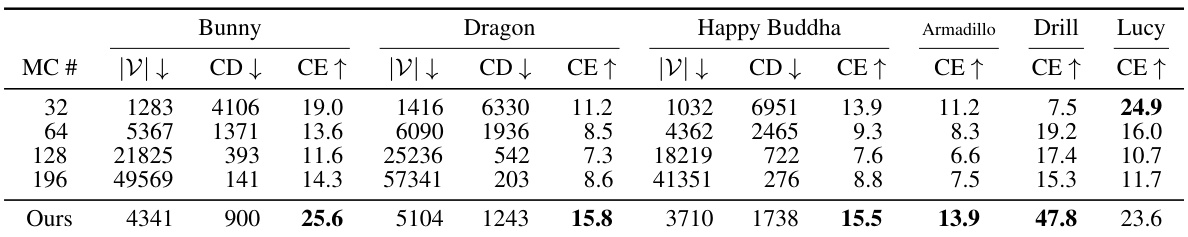

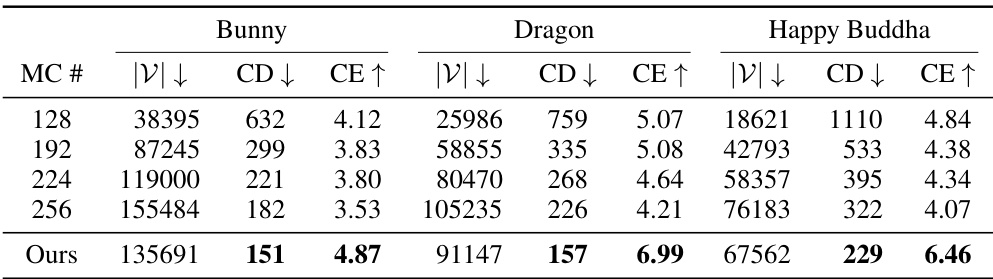

This table compares the chamfer distance (CD) and chamfer efficiency (CE) of the proposed method against marching cubes (MC) for various models from the Stanford 3D Scanning repository. Chamfer distance measures the similarity between two sets of points, representing the difference between the generated mesh and a ground truth mesh. Chamfer efficiency considers both the chamfer distance and the number of vertices in the mesh, providing a more comprehensive measure of the method’s performance.

In-depth insights#

Trilinear Meshing#

Trilinear meshing, in the context of neural implicit surface representation, presents a novel approach to mesh extraction. It leverages the inherent piecewise trilinear nature of networks employing trilinear interpolation for positional encoding, offering a significant advantage over traditional methods. Analytical extraction becomes possible by exploiting the transformation of hypersurfaces into flat planes within the trilinear regions under an eikonal constraint. This theoretical insight leads to efficient and accurate mesh generation. The method addresses challenges posed by non-linear positional encoding, prevalent in modern neural implicit surface networks, which often hinder mesh extraction techniques reliant on piecewise linear functions. Approximating intersecting points among multiple hypersurfaces is achieved with a parsimonious approach, enhancing broader applicability. Empirical validation via metrics such as chamfer distance, angular distance, and efficiency, coupled with an analysis of the correlation between eikonal loss and hypersurface planarity, demonstrates the method’s correctness and parsimony. This approach offers a compelling alternative to sampling-based techniques, potentially leading to improved efficiency and fidelity in visualizing and characterizing the geometry of neural implicit surfaces.

Eikonal Constraint#

The eikonal constraint, ||∇f(x)||=1, is a crucial regularization technique in neural implicit surface learning, ensuring the predicted function f(x) represents a signed distance function (SDF). This constraint forces the gradient of the function to have a unit magnitude at every point, implying that the surface’s level sets are equidistant, leading to a more accurate and stable mesh extraction process. In the context of piecewise trilinear networks, the eikonal constraint plays a significant role in simplifying the mesh extraction process; it transforms intricate hypersurfaces within each trilinear region into planar surfaces. This simplification is theoretically proven and empirically validated, resulting in a more efficient and accurate mesh representation of the underlying neural network. The effectiveness of the eikonal constraint is shown through the correlation between the eikonal loss and the planarity of hypersurfaces. Lower eikonal loss values directly correlate with increased hypersurface planarity, indicating a more accurate representation of the SDF and ultimately improving the mesh quality. By enforcing this constraint during training, the complexity of the mesh extraction is reduced, leading to a more efficient and robust method suitable for extracting meshes from complex neural implicit surface models.

Tropical Geometry#

Tropical geometry offers a unique lens through which to view neural networks, particularly those employing ReLU activation functions. Its piecewise linear nature aligns well with the inherent linearity of ReLU, allowing for the representation of neural network decision boundaries as tropical hypersurfaces. This perspective provides a powerful tool for analyzing the geometry of neural networks, offering insights into their expressivity, robustness and training dynamics. By translating the complex nonlinear functions of neural networks into a piecewise-linear framework, tropical geometry simplifies analysis and facilitates the extraction of meaningful structural information. The concept of tropical polynomials and their hypersurfaces provides a direct link to the decision regions defined by ReLU networks. This connection allows researchers to leverage existing tools and techniques from tropical geometry to analyze the behavior and characteristics of neural networks in a new and insightful way. Furthermore, understanding the relationship between tropical geometry and neural network architecture is key to enhancing the development and understanding of more efficient and interpretable models. However, extending the application of tropical geometry to neural networks that employ non-linear positional encoding, such as those using trigonometric functions or trilinear interpolation, presents a significant challenge. The theoretical work on this topic remains nascent and requires further investigation to fully capture the complexities of such models within the tropical framework.

Mesh Extraction#

Mesh extraction from neural implicit surfaces is a crucial step in bridging the gap between learned representations and practical applications. Traditional methods often rely on sampling-based approaches like marching cubes, which can be computationally expensive and produce meshes with varying quality. The paper’s focus on analytical mesh extraction offers a potential solution, providing a theoretically-grounded and potentially more efficient alternative. By leveraging the piecewise linearity inherent in certain neural network architectures, particularly those using trilinear interpolation, the authors propose a method to extract a mesh directly from the learned representation. This approach promises significant improvements in speed and accuracy. However, challenges remain. Approximations are necessary to handle non-linearity, and the method’s efficiency and robustness will need further evaluation on a wider range of networks and datasets. The introduction of a novel theoretical framework based on tropical geometry is a major contribution, laying a foundation for future research in this domain. Overall, the prospect of analytical mesh extraction holds immense promise for enhancing the efficiency and quality of results in various applications of neural implicit surfaces.

Future Works#

The paper’s core contribution is a novel mesh extraction method from piecewise trilinear networks, addressing challenges posed by non-linear positional encoding in neural implicit surface representation. Future work could explore several promising avenues. One is extending the theoretical analysis to encompass a broader range of non-linear positional encodings beyond trilinear interpolation, potentially incorporating techniques like Fourier features. Another key area is enhancing the method’s efficiency, particularly for large-scale models, perhaps by optimizing the edge subdivision algorithm or leveraging parallel processing techniques more effectively. Investigating the robustness of the mesh extraction under different training parameters and loss functions would be beneficial, and exploring applications beyond visualization—such as shape manipulation or generative modeling—would significantly expand the method’s impact. Finally, a thorough quantitative comparison with existing mesh extraction methods across diverse datasets and model architectures is needed to definitively establish the proposed method’s overall effectiveness and position within the field. Empirically validating these extensions through comprehensive experimentation is critical for solidifying the approach’s practical value.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure visualizes the process of mesh extraction from a piecewise trilinear network. It starts with a grid (a), identifies trilinear regions using sign-vectors (b, c), extracts zero-set vertices and edges (d), and finally skeletonizes the mesh (e). Each stage highlights different aspects of the mesh extraction process.

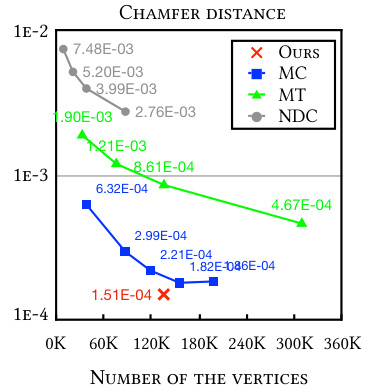

This figure shows the chamfer distance, a metric for evaluating the similarity between two sets of points from two meshes, for the bunny model using the Large model setting. It compares the proposed method with three other methods: Marching Cubes (MC), Marching Tetrahedra (MT), and Neural Dual Contour (NDC). The x-axis represents the number of vertices, and the y-axis represents the chamfer distance. The figure shows that the proposed method achieves lower chamfer distance with fewer vertices compared to the other three methods.

This figure illustrates the process of analytically extracting a mesh from piecewise trilinear networks. It starts with a grid and progressively subdivides it (linearly, bilinearly, then trilinearly) to handle intersecting regions, ultimately producing a mesh representation of the network’s decision boundaries.

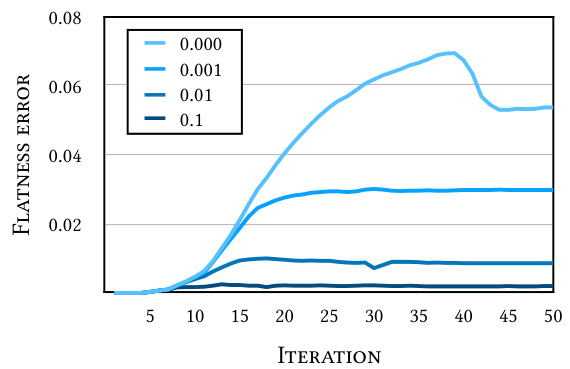

The figure shows the impact of different weights of the eikonal loss on the flatness error during training. The flatness error measures how well the hypersurfaces in the trilinear network approximate planes, as predicted by the theory. The plot shows that using a small weight for the eikonal loss (0.000-0.01) leads to higher flatness errors, meaning the hypersurfaces are not well approximated by planes. However, as the weight of the eikonal loss is increased, the flatness error decreases, indicating a better approximation of planes. The experiment is conducted using the unit sphere, demonstrating the correlation between the eikonal loss and the planarity of the hypersurfaces.

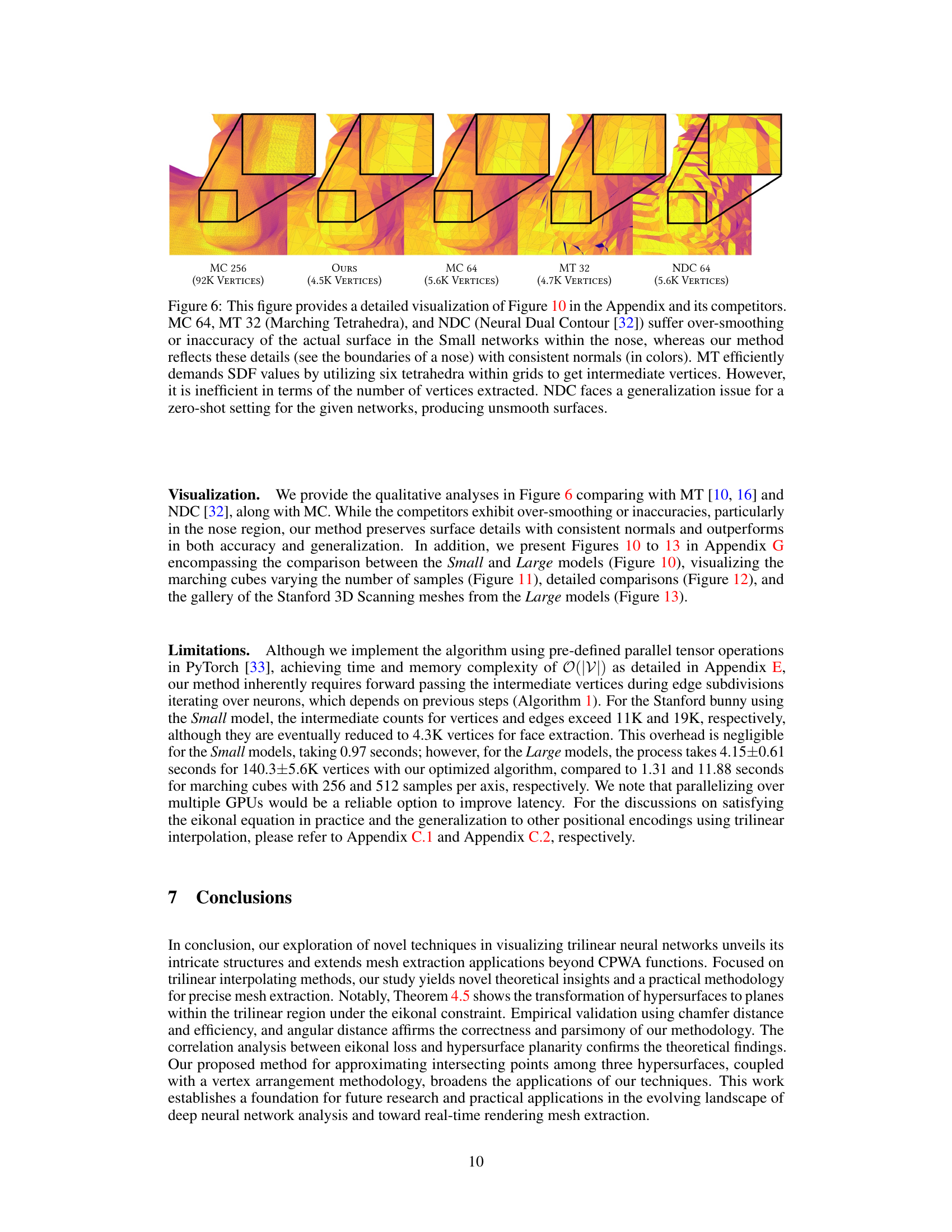

This figure compares the mesh generated by the proposed method with other methods (Marching Cubes, Marching Tetrahedra, and Neural Dual Contour) for a small neural network model. It highlights the proposed method’s ability to accurately capture fine details with consistent normals, while the other methods either suffer from over-smoothing or inaccuracies.

This figure illustrates how a classical polynomial is transformed into a tropical polynomial. Each color-coded region represents where a specific monomial term within the tropical polynomial takes on its maximum value. This visualization helps explain the concept of tropical hypersurfaces which are central to the paper’s theoretical analysis.

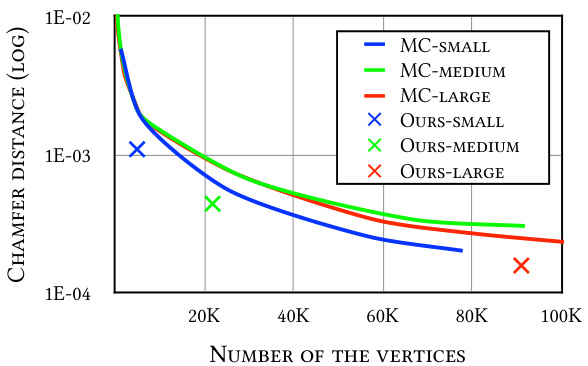

This figure compares the chamfer distance achieved by the proposed method with and without mesh simplification using Quadric Error Metrics (QEM). The results show that both methods benefit from QEM, indicating improved mesh efficiency. However, the proposed method consistently maintains lower chamfer distances, suggesting its effectiveness in retaining mesh quality even after simplification.

This figure illustrates the process of analytically extracting a mesh from piecewise trilinear networks. It begins with a grid, then progressively subdivides edges and faces to accurately represent the curved surfaces created by the neural network’s implicit function. The process handles intersections of surfaces, ultimately resulting in a complete mesh.

This figure illustrates the analytical mesh extraction process from piecewise trilinear networks. It starts by defining initial vertices and edges from a grid. Then, it shows how the mesh is refined through linear, bilinear, and trilinear subdivisions to handle intersections of polygons in the trilinear region. The process culminates in an accurate mesh representing the surface learned by the network.

This figure illustrates the analytical mesh extraction process from piecewise trilinear networks. It starts with a grid and progressively refines the mesh by subdividing edges and faces based on linear, bilinear, and trilinear interpolations. The process is driven by the eikonal constraint, which transforms hypersurfaces into flat planes within the trilinear regions, simplifying mesh extraction. The resulting mesh provides a precise and efficient representation of the network’s geometry.

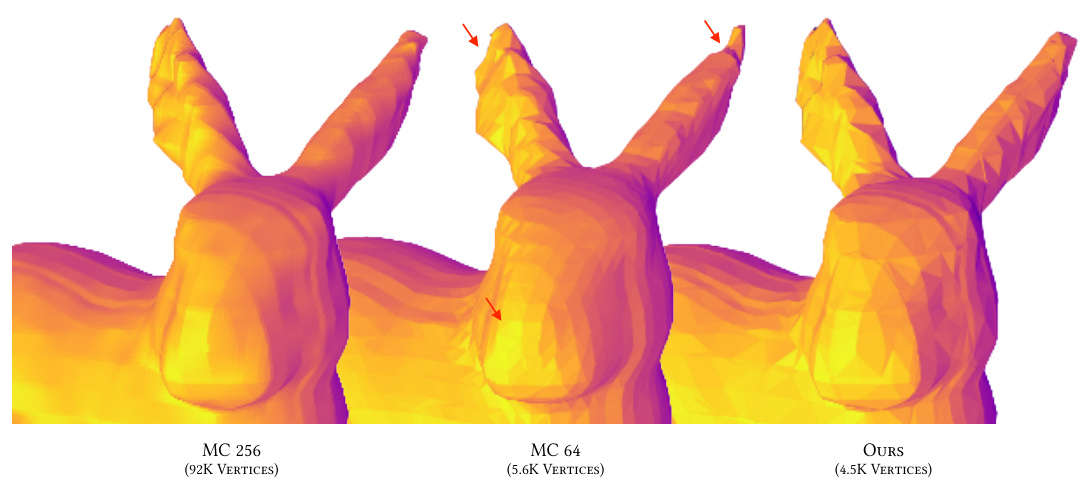

This figure compares the mesh generated by the proposed method with those generated by three other methods (Marching Cubes with 64 samples, Marching Tetrahedra with 32 samples, and Neural Dual Contouring with 64 samples) for a small-sized network. The figure highlights that the proposed method produces a more accurate mesh, especially around the nose area, which is a difficult region to accurately represent with conventional methods.

This figure illustrates the process of analytically extracting a mesh from piecewise trilinear networks. It starts with a grid and progressively subdivides it using linear, bilinear, and trilinear methods to capture intersections of hypersurfaces. The final result is a mesh representation of the learned signed distance function.

More on tables

This table compares the Chamfer distance (CD) and Chamfer efficiency (CE) of the proposed method against marching cubes (MC) with different grid resolutions for various 3D models from the Stanford 3D Scanning repository. Chamfer distance measures the difference between two sets of points, while Chamfer efficiency considers both CD and the number of vertices, offering a comprehensive evaluation metric. The table shows that the proposed method consistently achieves lower CD and higher CE compared to MC across all model resolutions, indicating improved accuracy and efficiency.

This table presents a comparison of Chamfer distance (CD) and Chamfer efficiency (CE) between the proposed method and Marching Cubes (MC) for various models from the Stanford 3D Scanning repository. Chamfer distance measures the similarity between two sets of points (meshes), and Chamfer efficiency considers both the CD and the number of vertices used in the mesh. Lower CD values indicate higher similarity, while higher CE values suggest better performance in terms of accuracy relative to the number of vertices used.

This table compares the chamfer distance (CD) and chamfer efficiency (CE) of the proposed method against marching cubes (MC) with different resolutions for three models from the Stanford 3D Scanning dataset. The chamfer distance measures the difference between the generated mesh and the ground truth mesh, while the chamfer efficiency balances this difference with the number of vertices in the mesh. Lower CD and higher CE are better, indicating higher accuracy and efficiency.

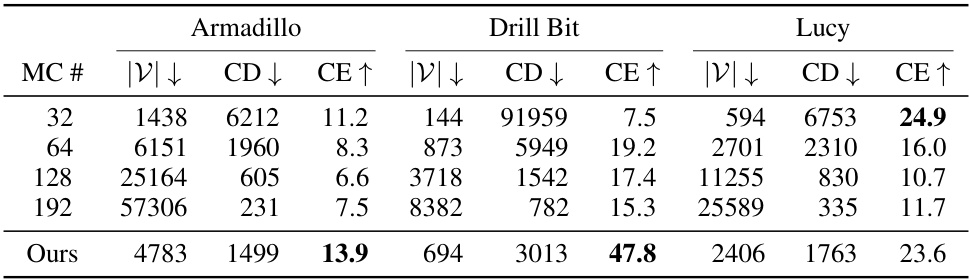

This table presents the Chamfer distance (CD) and Chamfer Efficiency (CE) for the Part B of the Stanford 3D Scanning dataset. It compares the performance of the proposed method against Marching Cubes (MC) at various resolutions (32, 64, 128, and 192 samples). Chamfer distance measures the similarity between two sets of points (the model and the ground truth), while Chamfer Efficiency considers the trade-off between the number of vertices and the CD. Lower CD values indicate better mesh quality, and higher CE values show a more efficient use of vertices to represent the surface.

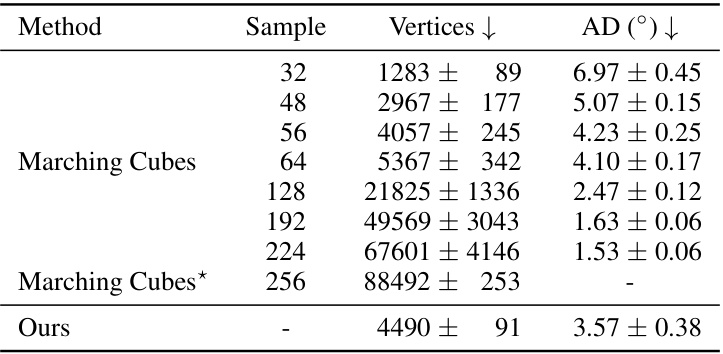

This table compares the Chamfer distance (CD) and Chamfer Efficiency (CE) of different mesh extraction methods (Marching Cubes with varying sample numbers and the proposed method) for the Stanford bunny model. The Marching Cubes results serve as a baseline using a high-resolution mesh as ground truth. The proposed method demonstrates significantly better Chamfer Efficiency, indicating a more accurate and parsimonious mesh representation. Error bars (standard deviation) are provided, reflecting the variability across three different random seeds during training. The table shows that the proposed method achieves a better balance between accuracy and efficiency compared to Marching Cubes, with significantly fewer vertices while maintaining a comparable level of accuracy.

This table presents the angular distance results for the Stanford bunny model. The angular distance measures how much the estimated surface normals deviate from the ground truth normals. The results are compared for different numbers of samples used in the marching cubes method, along with the results from the proposed method. Standard deviations are included, reflecting the variability across three independent runs with different random seeds.

This table presents the Chamfer distance (CD) and Chamfer Efficiency (CE) for four different models from the Stanford 3D Scanning repository’s Part A. The CD is calculated relative to a ground truth mesh created using marching cubes with 256³ samples. CE provides a normalized metric that balances the number of vertices in a mesh against its CD. The results are averages over three independent runs.

This table presents the chamfer distance and chamfer efficiency for the Part B of the Stanford 3D Scanning dataset. It compares the results of the proposed method to those obtained using marching cubes (MC) with different numbers of samples (32, 64, 128, and 192). The chamfer distance measures the similarity between two sets of sampled points from two meshes, while the chamfer efficiency considers both the chamfer distance and the number of vertices used, providing a concise measure of performance. Lower chamfer distances and higher chamfer efficiency are desirable. The results are averaged across three random seeds.

This table presents a comparison of chamfer distance (CD) and chamfer efficiency (CE) between the proposed method and the marching cubes (MC) method for various 3D models from the Stanford 3D Scanning repository. Chamfer distance measures the similarity between two sets of points, representing the surfaces of the models. Chamfer efficiency takes into account both the chamfer distance and the number of vertices in the mesh, providing a measure of how efficiently the mesh represents the surface. The table shows that the proposed method achieves significantly lower chamfer distances and higher chamfer efficiencies compared to the MC method. It also indicates that the proposed method uses far fewer vertices to achieve similar or better results than MC, demonstrating better efficiency.

This table shows the squared error (SE) of the predicted signed distance function (SDF) values on the surface of a trained model for different weights of the eikonal loss. The results demonstrate that as the weight of the eikonal loss increases, the SE decreases, indicating that the predicted SDF values converge to zero, which is consistent with the eikonal constraint. The table compares the results for different models (MC64, MC256, and the proposed method).

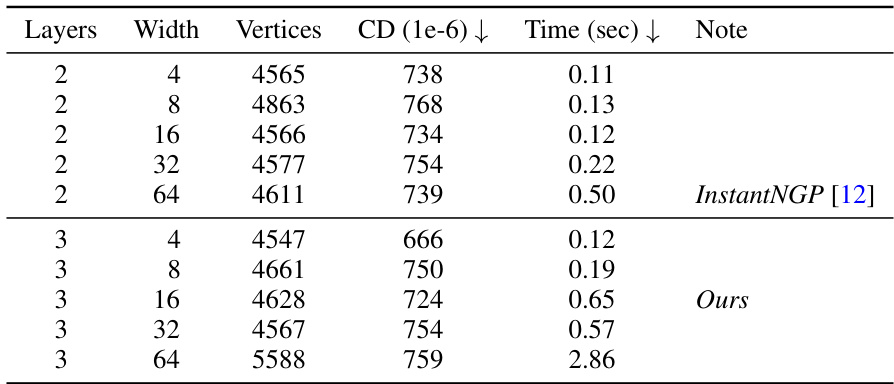

This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted to investigate the impact of varying the number of layers and width of neural networks on the performance of the proposed mesh extraction method using the Stanford bunny Small model. It shows the number of vertices generated, the chamfer distance (CD), and the processing time for different network configurations. The CD is a measure of the difference between the generated mesh and a reference mesh (ground truth). The table helps to understand the trade-off between model complexity, mesh accuracy, and computational cost.

Full paper#