↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) in computer vision often relies on heuristics and requires substantial computational resources and large datasets. Existing SSL algorithms struggle with efficiency and data-hunger, limiting their applicability in scenarios with limited data or resources. This hinders progress, particularly in areas like medical imaging where data acquisition is challenging.

This research tackles these challenges by reformulating the SSL loss function, providing theoretical justification and practical recommendations for improved efficiency. It emphasizes using a stronger orthogonalization constraint with a reduced projector dimensionality and incorporating multiple augmentations to minimize the reformulated loss. These changes lead to faster convergence, reduced computation, and the capacity to achieve the same accuracy with significantly less data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in self-supervised learning (SSL) as it provides theoretically grounded recommendations for improving SSL efficiency and data usage. It addresses the prevalent issue of data-hunger in SSL, offering practical solutions to enhance model training with limited datasets. The findings are relevant to current trends in computer vision and opens new avenues for research on efficient representation learning.

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the design of self-supervised learning (SSL) algorithms. Panel A shows the common use of augmentation graphs in vision pretraining, where augmentations of images provide generalizable features for downstream tasks. Panel B presents the authors’ proposed equivalent loss function for SSL pretraining. This new loss function aims to recover the same eigenfunctions as existing approaches but with improved efficiency.

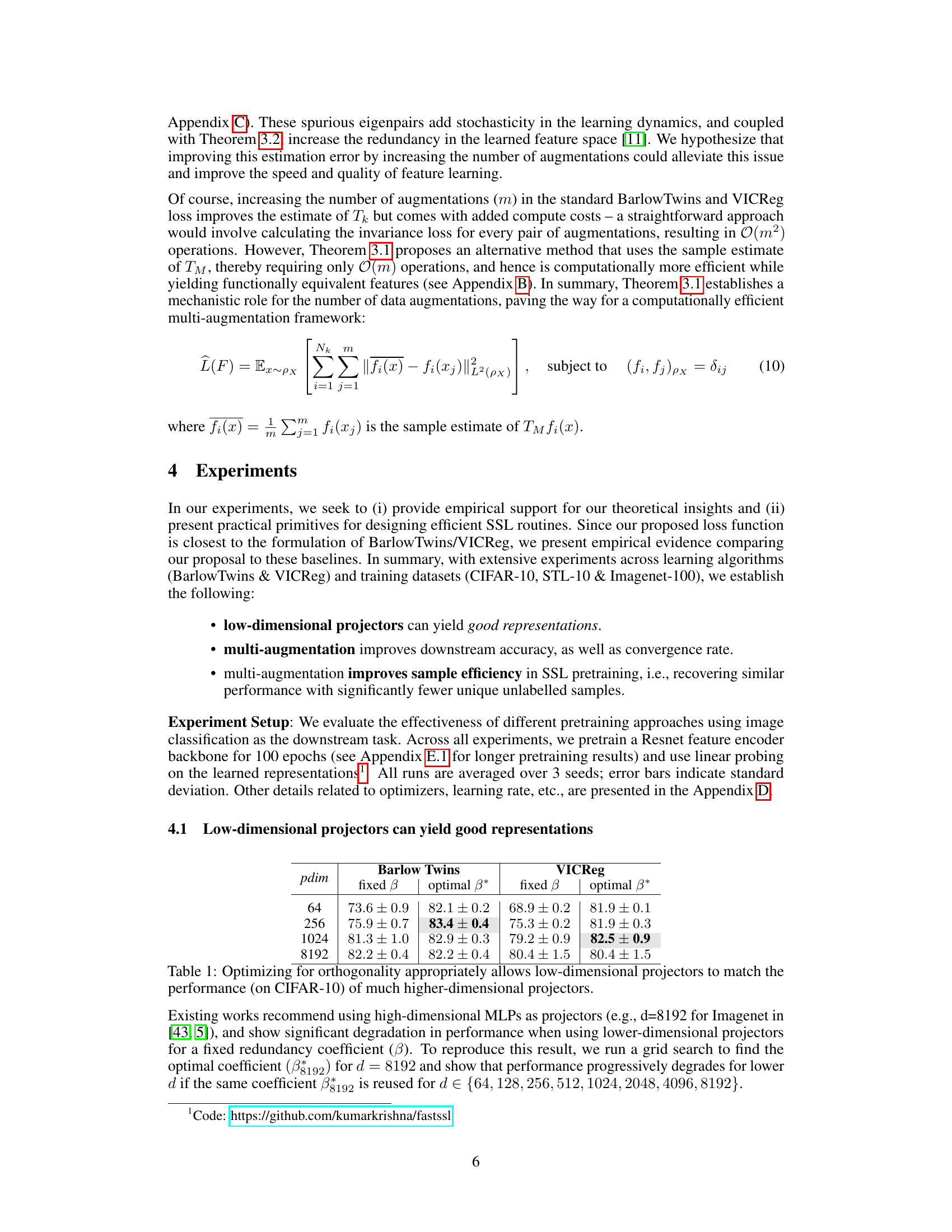

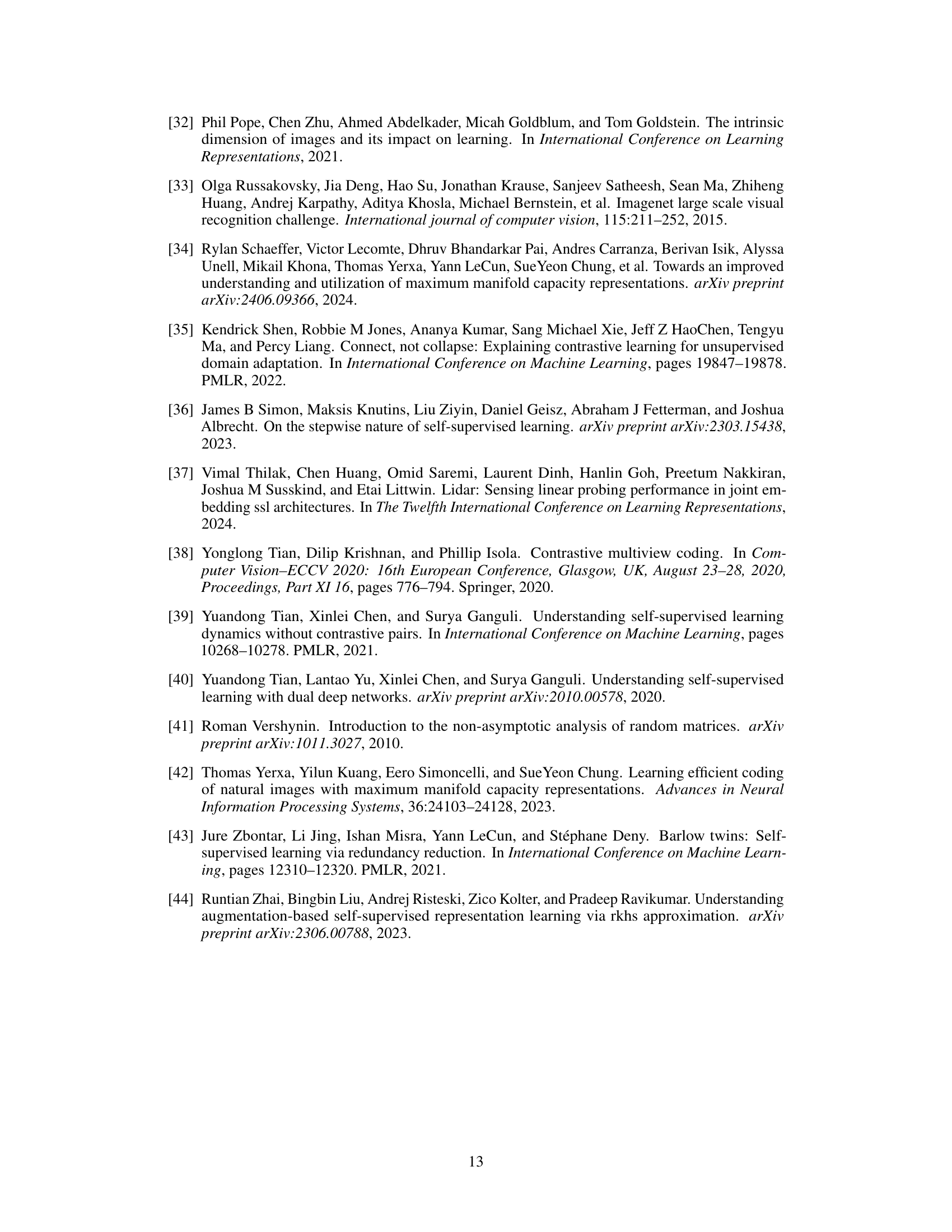

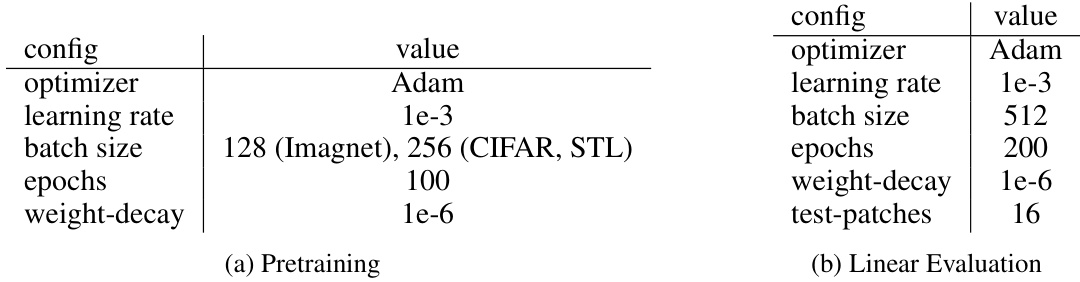

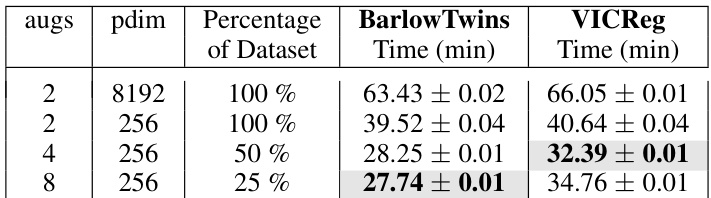

This table presents the results of experiments comparing the performance of Barlow Twins and VICReg models with different projector dimensionalities (pdim). It shows that using a properly tuned orthogonality constraint (beta), low-dimensional projectors can achieve similar performance to much larger, higher-dimensional ones, indicating that high-dimensionality is not always necessary for good representation learning with these methods.

In-depth insights#

Efficient SSL Loss#

The concept of “Efficient SSL Loss” in self-supervised learning (SSL) centers on reducing computational costs while maintaining or improving the quality of learned representations. The core idea revolves around reformulating the loss function, often a complex contrastive or non-contrastive method, into a functionally equivalent but more streamlined form. This typically involves leveraging theoretical insights to reveal inherent redundancies or inefficiencies in existing SSL frameworks. By simplifying the loss, the training process becomes more efficient, requiring less computational power and time. A critical aspect is maintaining the quality of the learned representations by ensuring the simplified loss still captures the essential properties of data similarity and invariance to augmentations. Theoretical analysis and empirical validation are crucial to verify that this efficiency gain does not come at the cost of representation quality. Ultimately, efficient SSL loss methods aim to make self-supervised pretraining more accessible and practical, particularly for applications with limited computational resources or large-scale datasets.

Implicit Bias of GD#

The section titled ‘Implicit Bias of GD’ would delve into how the choice of gradient descent (GD) as the optimization algorithm subtly influences the learned features in self-supervised learning (SSL). GD’s implicit bias, meaning its tendency to prioritize certain features over others even without explicit constraints in the loss function, is a crucial aspect of SSL’s effectiveness. The analysis would likely explore how GD’s inherent preference for learning dominant eigenfunctions of the data augmentation kernel impacts feature representation learning. Stronger orthogonalization constraints are likely discussed as a means to mitigate GD’s bias and encourage a more balanced representation. The discussion would also probably cover how the number of data augmentations influences GD’s behavior; more augmentations providing a better estimate of the data similarity kernel, potentially leading to improved convergence and reduced bias. Ultimately, this section aims to provide a theoretical understanding of how GD shapes the learned representations, paving the way for more efficient and effective SSL strategies.

Low-dim Projectors#

The research explores the effectiveness of low-dimensional projectors in self-supervised learning (SSL). Conventional wisdom often suggests high-dimensional projectors are necessary for optimal performance. However, the study challenges this notion by demonstrating that low-dimensional projectors, when coupled with stronger orthogonalization constraints, can achieve comparable or even better results. This is theoretically grounded in the analysis of the implicit bias of gradient descent during optimization of the SSL loss function. The results indicate that the selection bias of gradient descent, favoring the learning of dominant eigenfunctions, can be mitigated by enforcing stronger orthogonality, making low-dimensional projectors surprisingly effective and computationally more efficient. This finding has significant implications for improving the efficiency and resource requirements of SSL, particularly important in resource-constrained settings.

Multi-Augmentations#

The concept of “Multi-Augmentations” in self-supervised learning (SSL) focuses on using multiple augmented versions of the same image during training, rather than just two. This approach is theoretically grounded in improving the approximation of the data similarity kernel, which is crucial for SSL. Increased augmentation improves the convergence rate and enables learning of better features. Empirically, this translates to faster training and even the ability to achieve comparable downstream performance with significantly reduced dataset sizes. The key advantage lies in improving the efficiency of SSL without sacrificing accuracy. This is particularly beneficial in data-constrained scenarios, where the improved sample efficiency can be a game-changer. However, it’s noted that there may be a trade-off in very low-data regimes, highlighting the importance of balancing the number of augmentations with the available data.

Sample Efficiency#

The research explores sample efficiency in self-supervised learning (SSL), a crucial aspect for applying SSL to data-scarce scenarios. The core idea revolves around leveraging multiple data augmentations to improve the efficiency of feature learning. The authors demonstrate that using more augmentations can lead to comparable or even better downstream performance with significantly reduced dataset sizes, up to 50% reduction in some experiments. This is achieved by improving the estimation of the data similarity kernel, a key element in SSL, which in turn leads to faster convergence and better feature representation. This approach directly addresses the data-hungry nature of many SSL methods, making them more practical for real-world applications constrained by limited data.

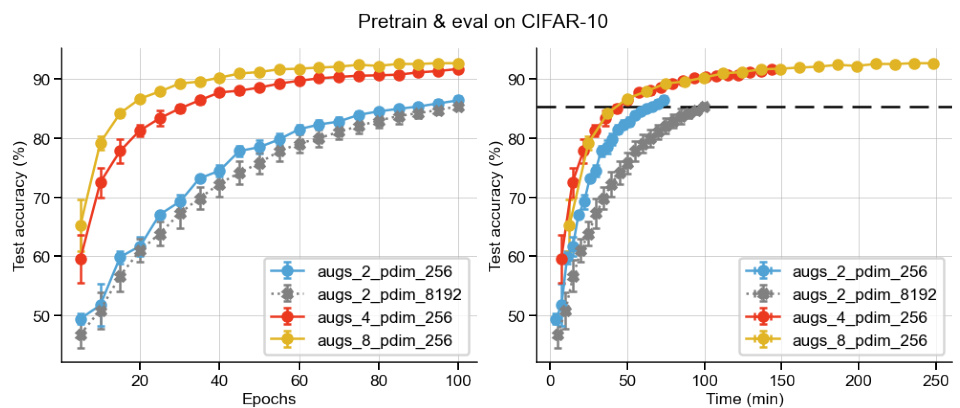

More visual insights#

More on figures

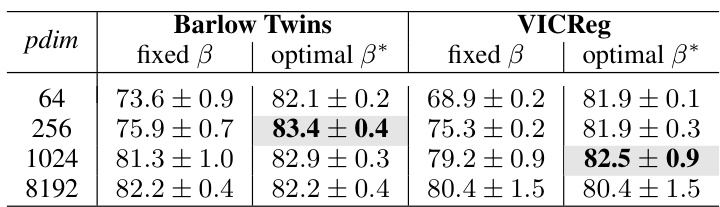

This figure shows that using a higher orthogonality constraint (β) with lower-dimensional projectors can achieve similar performance to higher-dimensional projectors across various datasets (CIFAR-10, STL-10, and Imagenet-100) and algorithms (BarlowTwins and VICReg). The results support the recommendation to use lower-dimensional projectors with appropriate orthogonalization.

This figure empirically validates the theoretical finding that using stronger orthogonalization with lower-dimensional projectors can achieve comparable performance to high-dimensional projectors in self-supervised learning. It shows that by tuning the hyperparameter beta (β), similar test accuracy can be obtained across different projector dimensionalities (d), disproving the common heuristic that very high-dimensional projection heads are necessary.

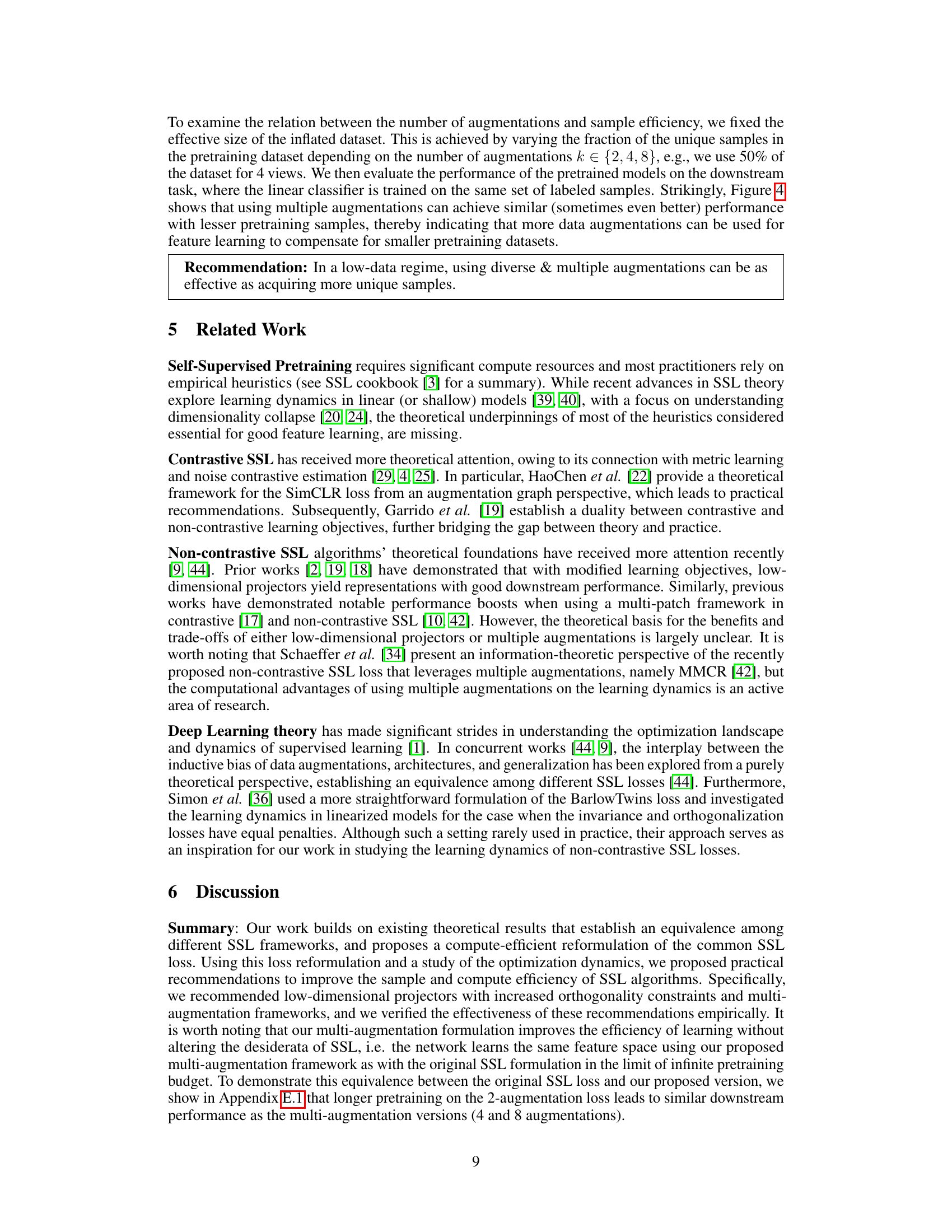

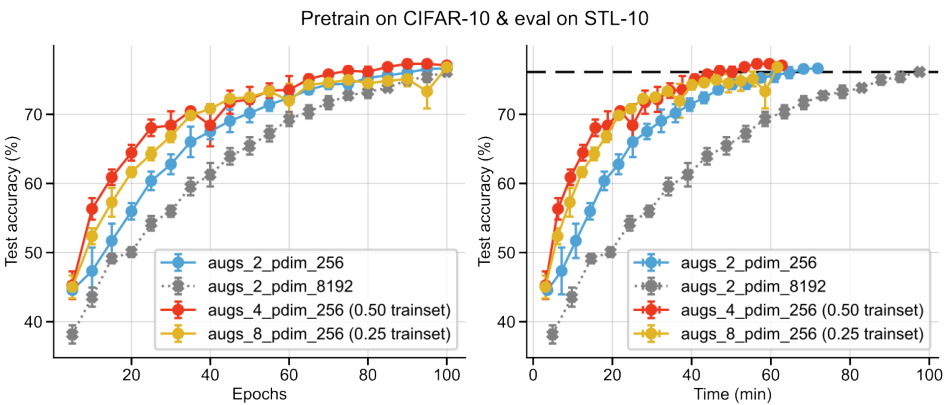

This figure empirically demonstrates the impact of using multiple augmentations in improving sample efficiency. It shows that with the same effective dataset size (number of augmentations multiplied by the number of unique samples), using more augmentations results in better performance across various datasets (CIFAR-10, STL-10, and Imagenet-100) and algorithms. However, the benefit plateaus in data-scarce scenarios.

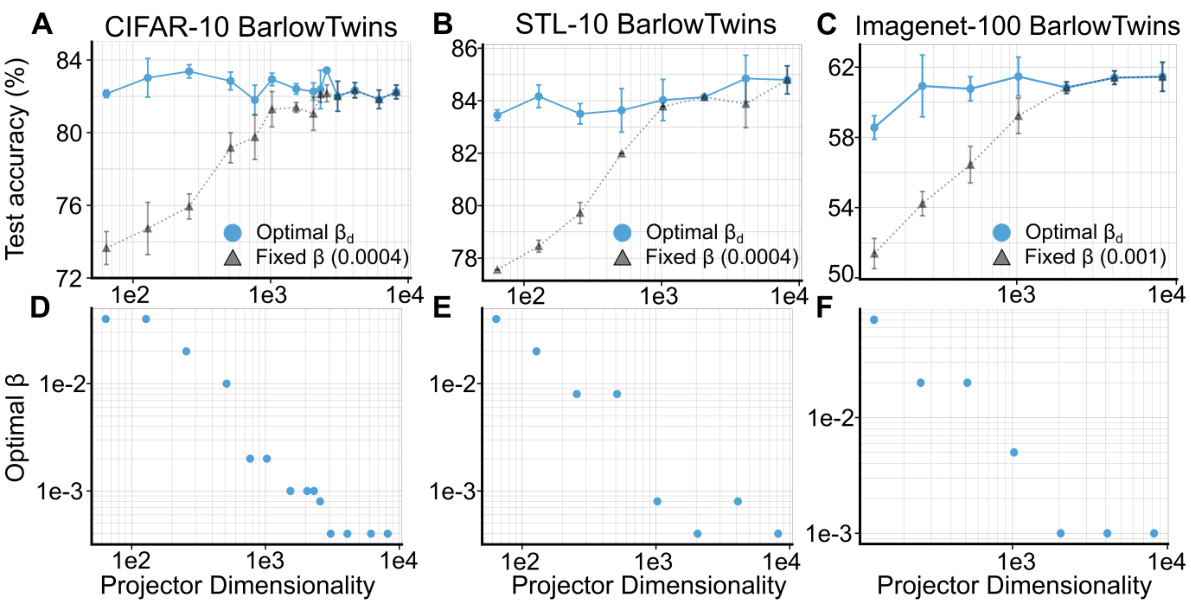

This figure shows the Pareto frontier for sample efficiency in self-supervised learning. The x-axis represents runtime (in minutes), and the y-axis represents the error rate (%). Different curves represent different training scenarios using various numbers of augmentations (2, 4, and 8) and different fractions of the full training dataset. The multi-augmentation approach (black circles) shows improved performance (lower error) at a reduced runtime compared to the baseline of 2 augmentations (blue triangles). The figure demonstrates that using more augmentations improves the Pareto frontier by enabling faster convergence or achieving similar performance with fewer samples.

This figure illustrates the concept of an augmentation graph, which represents the relationships between augmented versions of images. Panel (A) shows how augmentations from a single image form a cluster in the feature space, and these clusters can overlap. Panel (B) provides a more detailed view, using probabilities to model the connections between different augmentations.

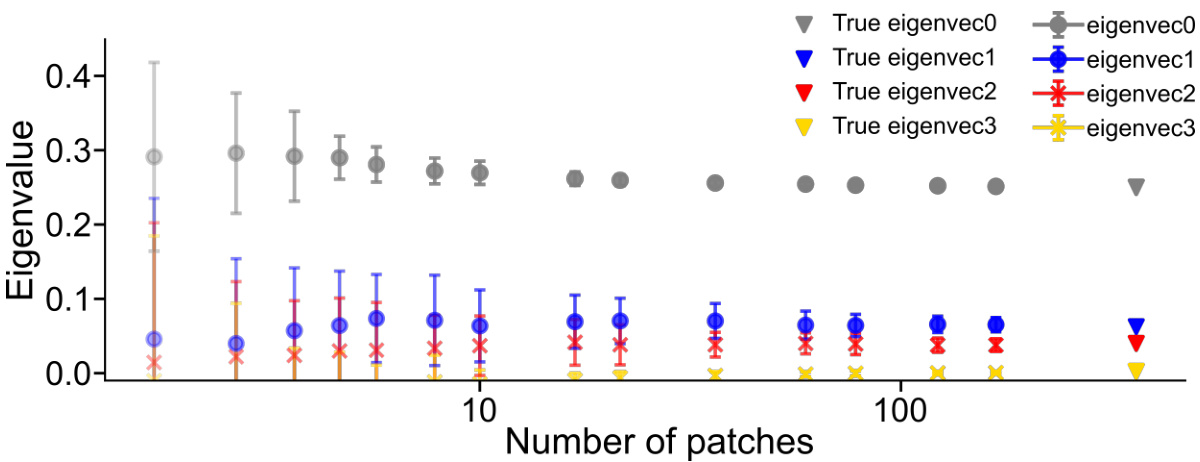

This figure empirically validates the subsampling ansatz introduced in the paper. The ansatz pertains to the eigenvalues of a sampled augmentation graph, particularly in scenarios with few augmentations per example. It shows that when the augmentation space is not sufficiently sampled, the eigenvalues corresponding to class information and pixel-level global information become very close to each other, and eigenvalues associated with augmentations changing both class and global information approach zero. This suggests that when only a few augmentations are used, the learning process may suppress class information in favor of pixel-level information, leading to increased smoothness in the learned feature space. The figure plots the eigenvalues and compares them between the true values from the complete augmentation graph and the values obtained from subsampled versions of this graph. Error bars demonstrate the variability of the eigenvalues due to the stochasticity of the subsampling process.

This figure empirically validates that low-dimensional projectors can achieve performance comparable to high-dimensional ones, provided an appropriate orthogonality constraint (β) is applied. It shows the test accuracy achieved across different projector dimensions (d) with both a fixed β and an optimized β for each d. The results support the claim that using a stronger orthogonality constraint with lower-dimensional projectors can be as effective as using a high-dimensional projector.

This figure shows that using low-dimensional projectors with a stronger orthogonality constraint can achieve similar performance to high-dimensional projectors for both BarlowTwins and VICReg algorithms. It highlights that the optimal orthogonality constraint (β) is inversely proportional to the projector dimensionality (d).

This figure empirically validates the theoretical finding that using stronger orthogonalization with lower-dimensional projectors can achieve performance comparable to higher-dimensional ones. It shows the test accuracy on CIFAR-10, STL-10 and ImageNet-100 datasets for different projector dimensions (d) using both fixed and optimized orthogonality constraints (β). The results support the recommendation to use lower-dimensional projectors with appropriately tuned orthogonality constraints for improved efficiency.

This figure illustrates the difference between existing self-supervised learning (SSL) algorithms and the proposed method. (A) shows that existing SSL algorithms rely on heuristic choices regarding data augmentations and the projection dimensionality of the embedding network. In contrast, (B) illustrates that the proposed method is theoretically grounded and offers an equivalent, more efficient loss function for SSL pretraining, focusing on the eigenfunctions of the augmentation-defined data similarity kernel.

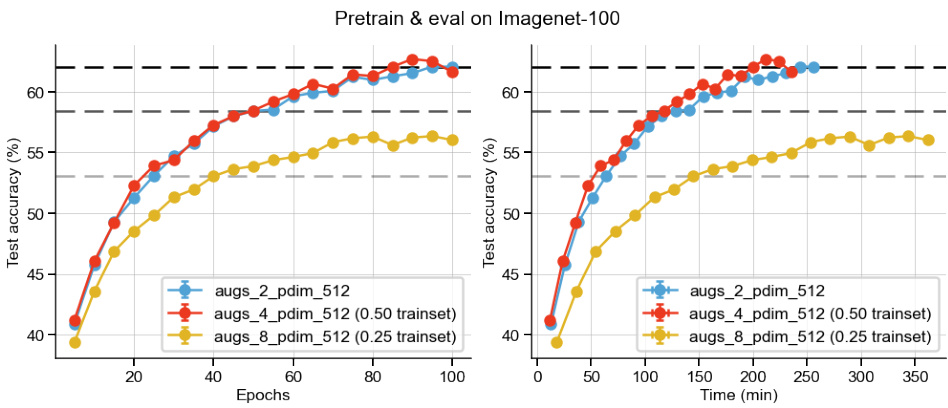

This figure shows the results of BarlowTwins pretraining on the full Imagenet-100 dataset using 2, 4, and 8 augmentations. The x-axis represents either training epochs or training time (in minutes), and the y-axis represents the test accuracy. The plot visually compares the convergence speed and final accuracy achieved with different numbers of augmentations. The goal is to demonstrate the impact of using multiple augmentations on both the speed and performance of the self-supervised learning process.

This figure shows the impact of using multiple augmentations on sample efficiency in self-supervised learning. It demonstrates that with more augmentations, similar performance can be achieved using a smaller subset of the training data. The results are shown across three datasets (CIFAR-10, STL-10, and Imagenet-100) and for two algorithms (BarlowTwins and VICReg). While the multi-augmentation approach shows promise in data-scarce situations, a trade-off point may be reached where excessive augmentations fail to further enhance performance.

This figure shows the test accuracy achieved by BarlowTwins and VICReg models with different projector dimensionalities (d) on CIFAR-10, STL-10, and Imagenet-100 datasets. It demonstrates that using a higher orthogonality constraint (β) with lower-dimensional projectors can achieve similar performance to higher-dimensional projectors, suggesting that high-dimensional projectors might be unnecessary. The optimal β value is inversely proportional to the projector dimensionality (d), as predicted by theory.

This figure empirically demonstrates the effect of using multiple augmentations in self-supervised learning (SSL). It shows that with a fixed effective dataset size (the number of augmentations multiplied by the number of unique samples), increasing the number of augmentations can lead to similar or even better performance in downstream tasks. This indicates that multiple augmentations can act as a form of data augmentation, making the training more sample-efficient. However, the figure also suggests that beyond a certain point, using too many augmentations may not lead to further performance gains, particularly in low-data regimes.

This figure empirically shows that using multiple augmentations in self-supervised learning improves sample efficiency. The results across three different datasets (CIFAR-10, STL-10, and Imagenet-100) and two algorithms (BarlowTwins and VICReg) demonstrate that achieving similar performance to using a full dataset and two augmentations can be done with smaller datasets and more augmentations. However, this benefit plateaus in very low data settings.

This figure empirically demonstrates the impact of using multiple augmentations on sample efficiency in self-supervised learning (SSL). It shows that by increasing the number of augmentations, similar performance can be achieved even with a smaller proportion of the original training data. The results are presented for three different datasets: CIFAR-10, STL-10, and Imagenet-100, each using BarlowTwins as the SSL algorithm. The figure highlights a trade-off: while multiple augmentations improve sample efficiency, they might not provide the same level of benefit when the initial dataset is already very small.

This figure empirically shows that using multiple augmentations in self-supervised learning can lead to improved sample efficiency. The results, shown across three different datasets (CIFAR-10, STL-10, and Imagenet-100), demonstrate that maintaining a constant effective dataset size (number of augmentations multiplied by the number of unique samples) while increasing the number of augmentations results in similar or even better performance compared to using fewer augmentations with a larger dataset. The figure highlights a trade-off: while this benefit is observed in data-rich settings, it may not hold true when dealing with extremely limited data.

This figure empirically demonstrates the impact of using multiple augmentations in self-supervised learning. It shows that by increasing the number of augmentations, similar performance can be achieved even with a smaller number of unique training samples. The results are shown across three datasets (CIFAR-10, STL-10, and Imagenet-100) using two different self-supervised learning algorithms (BarlowTwins and VICReg). While multiple augmentations generally improve performance, a trade-off is observed in data-scarce scenarios.

This figure shows the test error rate of BarlowTwins model with different number of augmentations (2, 4, and 8) over 400 epochs. It demonstrates the impact of using multiple augmentations on the model’s performance and training convergence. The plot shows test error (%) against epochs on the left and training time in minutes on the right.

This figure empirically demonstrates the impact of using multiple augmentations in self-supervised learning. It shows that using more augmentations allows for achieving comparable performance with a smaller number of unique training samples, showcasing improved sample efficiency. This effect is observed across different datasets (CIFAR-10, STL-10, and ImageNet-100) and with two different self-supervised learning algorithms (BarlowTwins and VICReg). While increasing the number of augmentations generally improves performance, there’s a trade-off in very data-scarce regimes.

This figure empirically demonstrates that using multiple augmentations in self-supervised learning (SSL) can significantly improve sample efficiency. The results are shown across three different datasets (CIFAR-10, STL-10, and Imagenet-100) and for two different SSL algorithms (Barlow Twins and VICReg). While using more augmentations does increase the overall training time for the same number of epochs, the experiments reveal that comparable or even better performance can be obtained with fewer unique samples by leveraging more data augmentations.

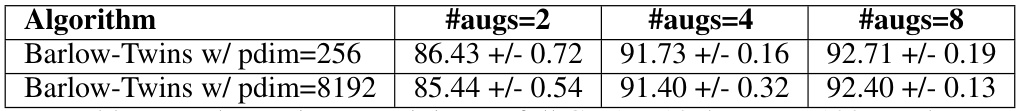

More on tables

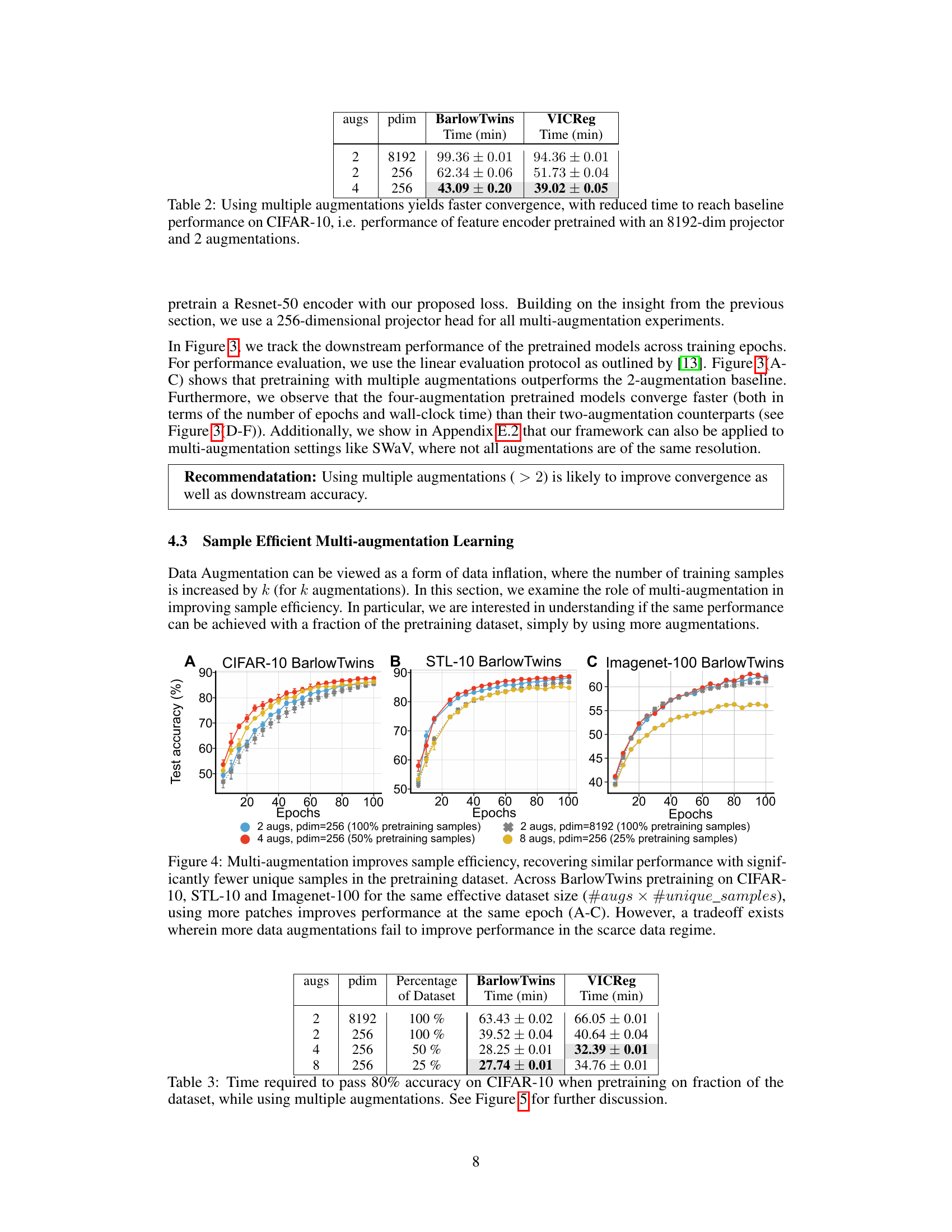

This table shows the time taken (in minutes) for BarlowTwins and VICReg to reach baseline performance on CIFAR-10. The baseline performance is defined as the performance achieved using an 8192-dimensional projector and only two augmentations. The table compares the time taken to reach this baseline performance under different conditions: using 2 augmentations with an 8192-dimensional projector, 2 augmentations with a 256-dimensional projector, 4 augmentations with a 256-dimensional projector, and 4 augmentations with a 256-dimensional projector. The results highlight that increasing the number of augmentations reduces the training time required to achieve baseline performance.

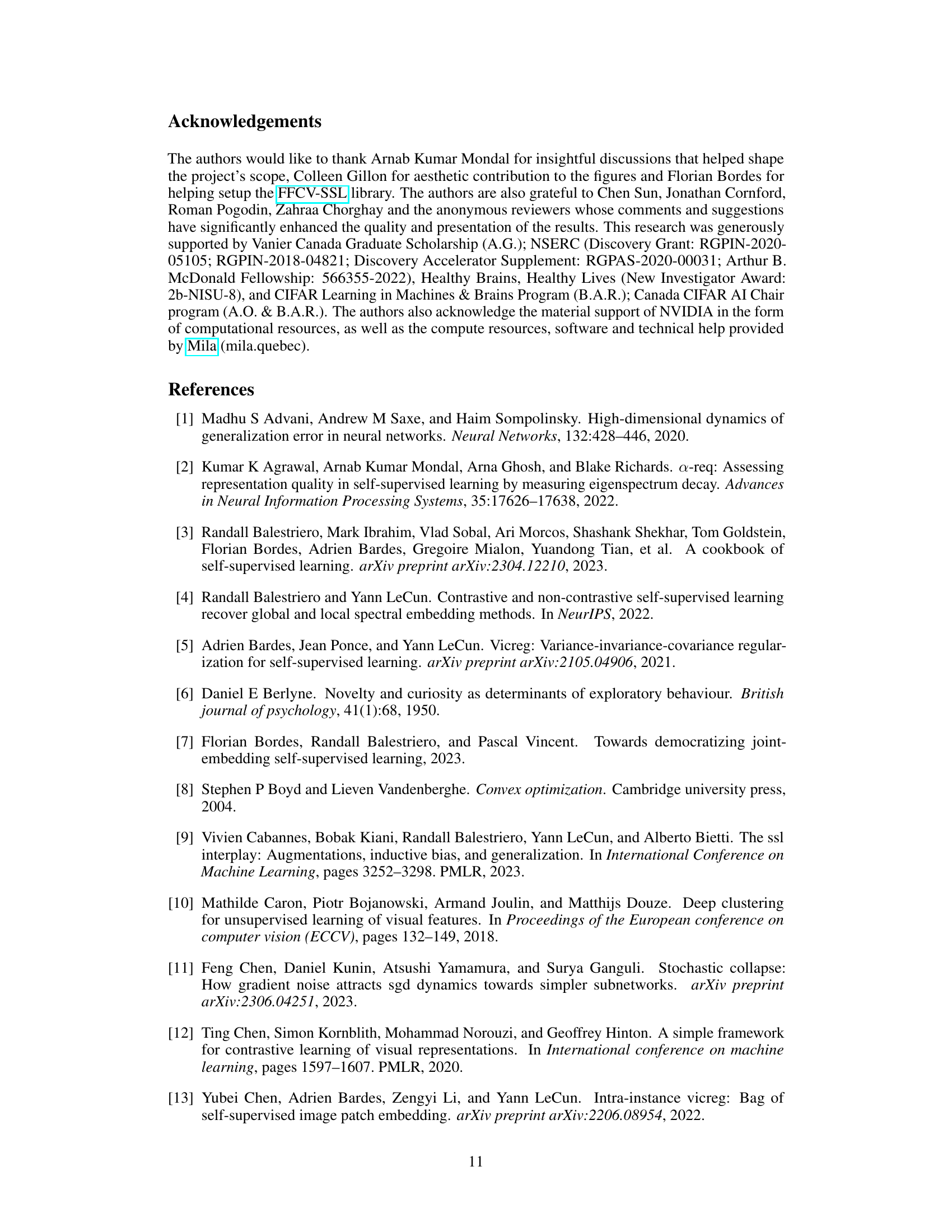

This table shows the time it takes to reach 80% accuracy on the CIFAR-10 dataset using different numbers of augmentations and different fractions of the dataset for pretraining. It highlights the time efficiency gains achievable by using more augmentations even with smaller datasets.

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing the performance of Barlow Twins and VICReg models with different projector dimensions. It shows that using a stronger orthogonality constraint with lower-dimensional projectors can achieve similar or better accuracy compared to models with higher-dimensional projectors. This supports the paper’s claim that low-dimensional projectors can be efficient for self-supervised learning.

This table presents the results of experiments comparing the performance of BarlowTwins and VICReg with different projector dimensionalities (pdim) on the CIFAR-10 dataset. It demonstrates that using a stronger orthogonality constraint (optimal beta) allows for achieving similar performance with low-dimensional projectors (e.g., 64) as with much higher-dimensional projectors (e.g., 8192), thereby reducing the computational cost without significant performance loss. The table highlights the importance of optimizing the orthogonality constraint for different projector sizes to achieve optimal performance.

This table shows that using the proposed method with a strong orthogonalization constraint, even low-dimensional projectors can achieve similar performance as high-dimensional projectors on the CIFAR-10 dataset. It compares the performance of Barlow Twins and VICReg with different projector dimensions (64, 256, 1024, 8192) using both a fixed beta and an optimized beta. The optimized beta is chosen specifically for each dimension to maximize performance, showing that the proposed approach can achieve high performance even with fewer parameters.

Full paper#