↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many time-series forecasting tasks involve numerous variables, making model selection crucial. Current methods often focus on finding just one optimal subset of variables, limiting insights and potentially leading to misleading conclusions. Existing approaches also struggle to scale efficiently to high-dimensional data. This paper addresses these limitations.

The paper introduces ChronoEpilogi, a novel algorithm that efficiently discovers all minimal-size subsets of variables that optimally predict a target variable. It handles hundreds of variables effectively, significantly reducing model complexity. The algorithm is rigorously proven sound and complete under mild assumptions, and experiments confirm its efficiency and accuracy on both real-world and synthetic datasets. The multiple solutions provided allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the data and reduced risk of making flawed predictions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with time-series data, especially in high-dimensional settings. It introduces a novel algorithm, ChronoEpilogi, that efficiently identifies multiple optimal solutions for variable selection, providing valuable insights beyond a single optimal model. This has significant implications for knowledge discovery, causal modeling, and building robust forecasting systems.

Visual Insights#

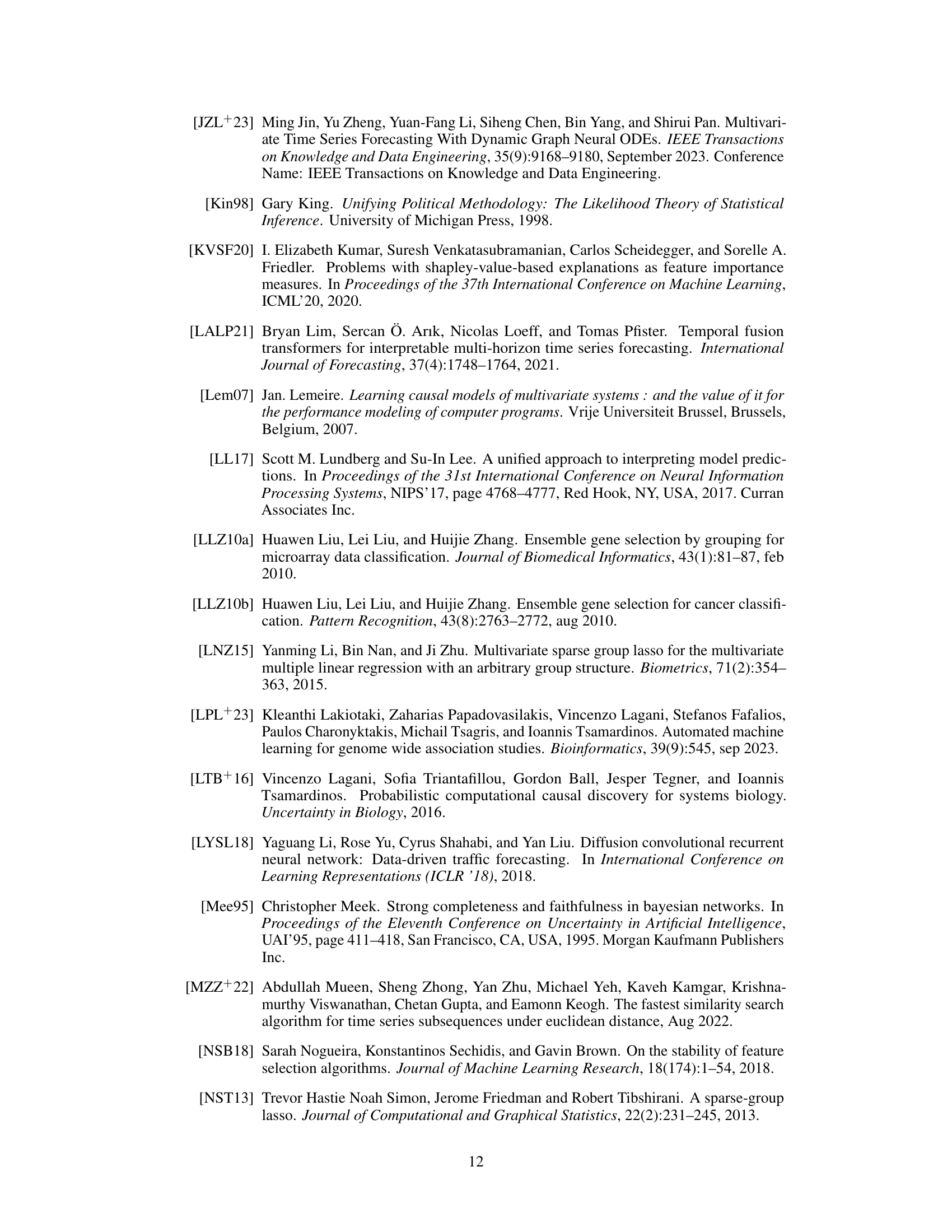

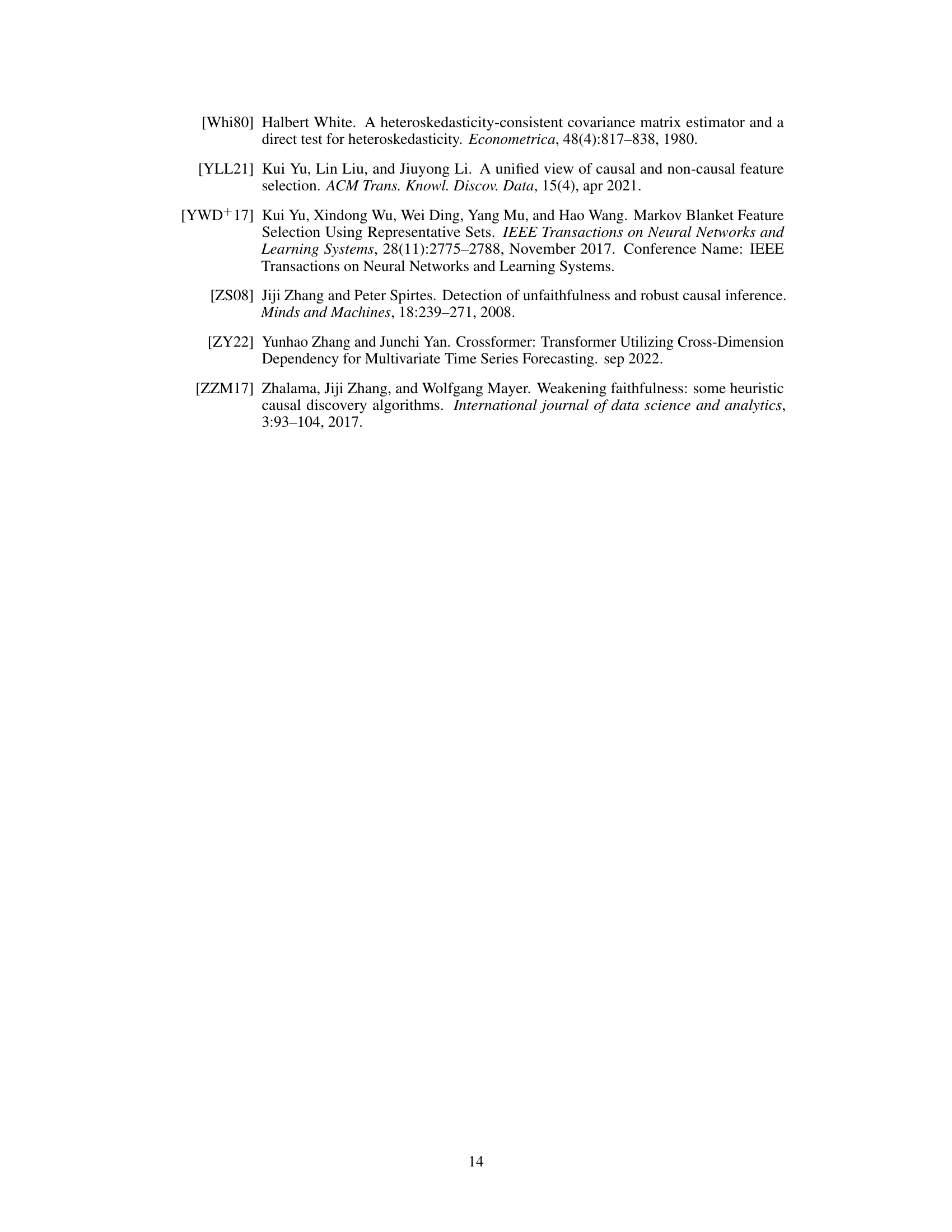

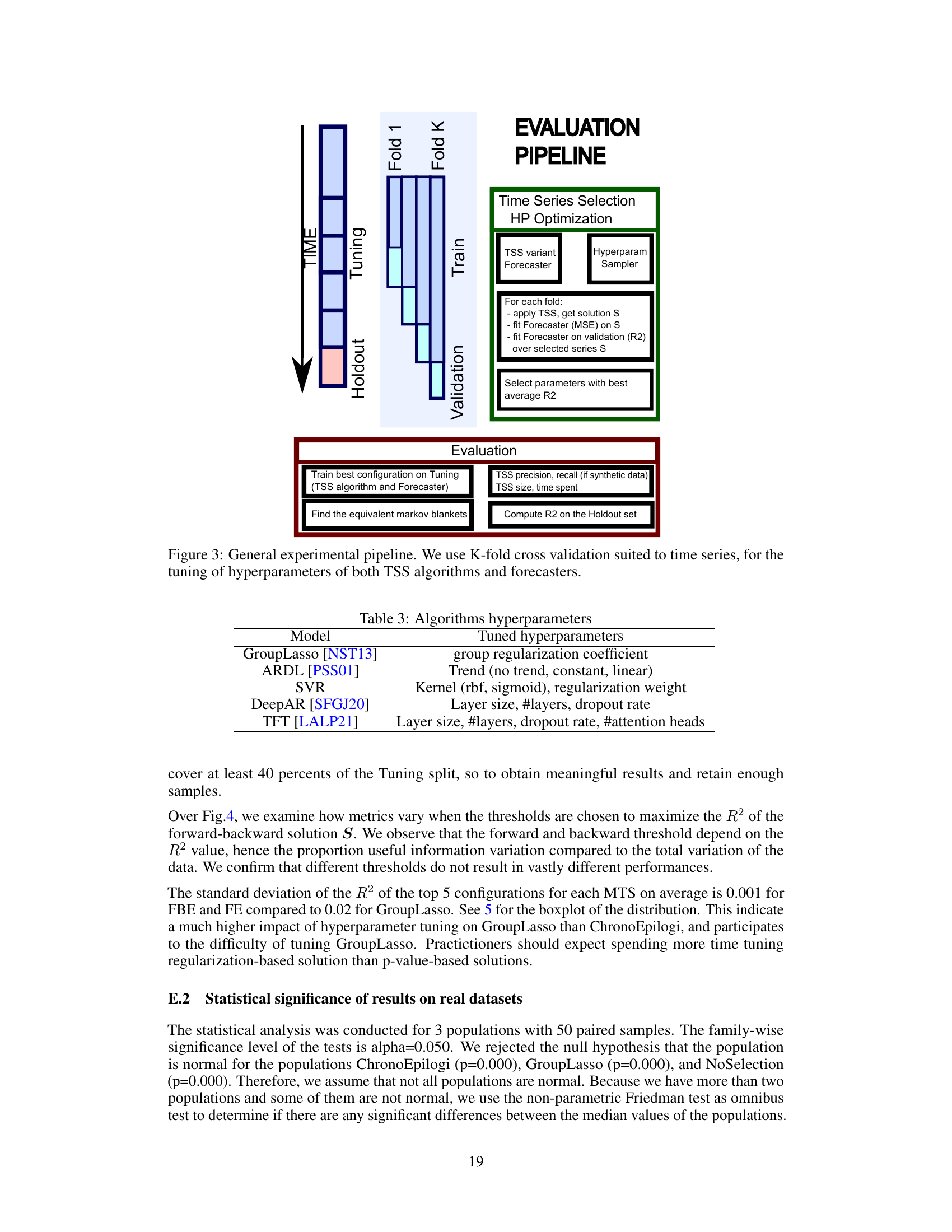

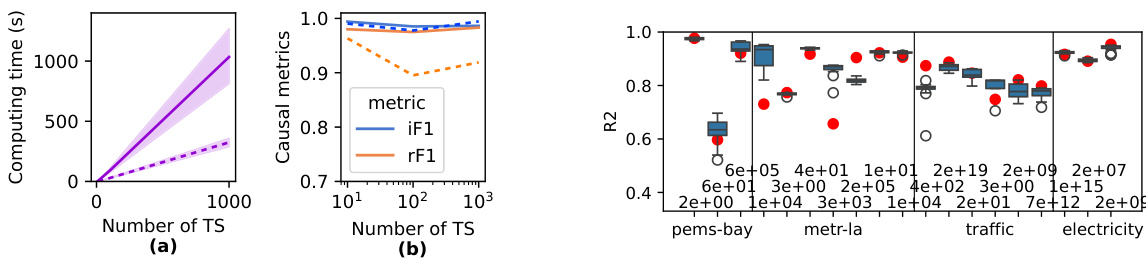

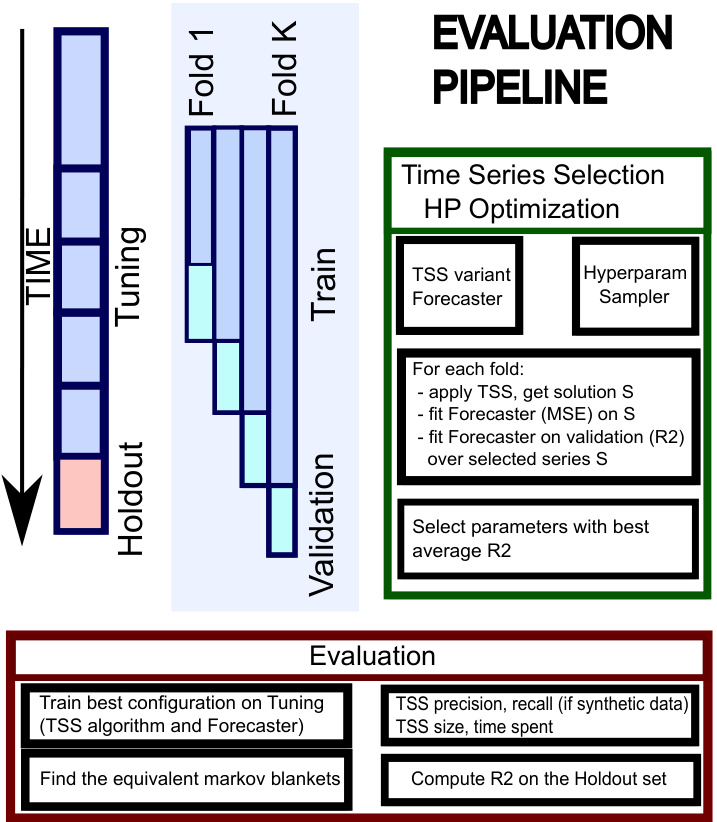

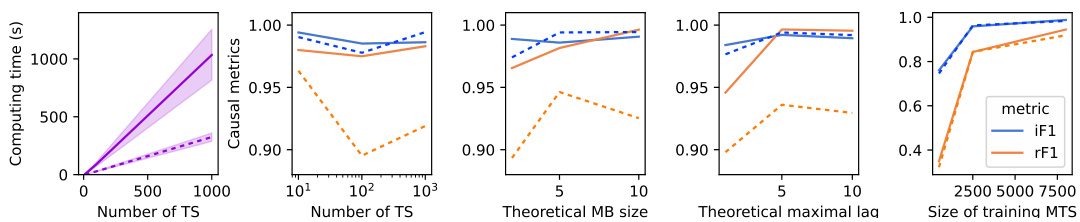

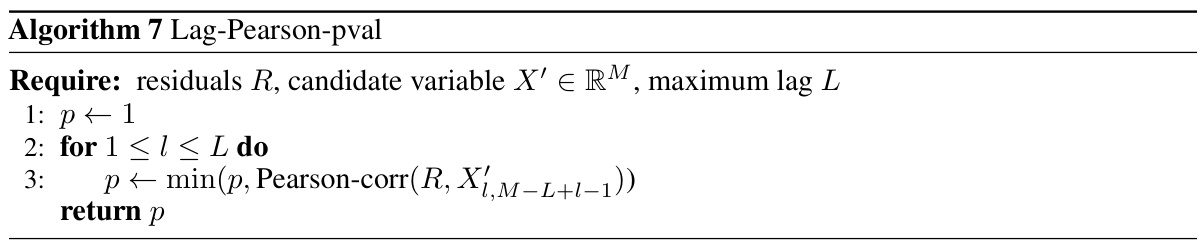

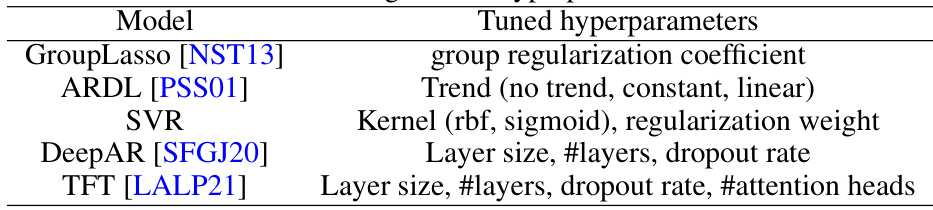

This figure presents a comparison of the performance of two versions of the ChronoEpilogi algorithm (FBE and FE) and their comparison with Group Lasso. Subfigure (a) shows the computing time of both algorithms on synthetic data, demonstrating that FE offers a significant speedup. Subfigure (b) displays the causal f1-scores (for irreplaceable and replaceable variables) of both algorithms across varying numbers of time series variables in the synthetic data. Finally, subfigure (c) shows the R-squared values achieved by the different methods on four real-world datasets (PEMS-BAY, METR-LA, Traffic, and Electricity). The red dots represent the R-squared value obtained by Group Lasso.

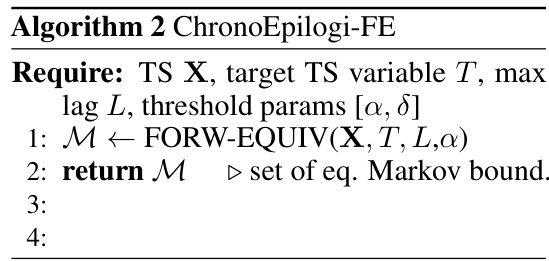

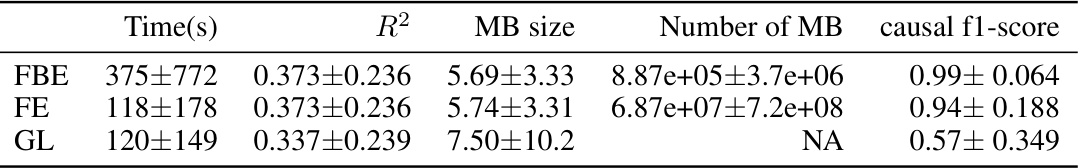

This table compares the performance of three algorithms: ChronoEpilogi-FBE, ChronoEpilogi-FE, and GroupLasso on a synthetic dataset containing 270 multivariate time series. The comparison includes computation time, predictive performance (measured by R-squared), the size of the selected variable sets (MB size), and causal f1-score. The results show that ChronoEpilogi-FE achieves comparable computation time and predictive power to GroupLasso, but with a significant improvement (30%) in causal f1-score.

In-depth insights#

Multi-TS Variable Selection#

Multi-TS variable selection, a crucial aspect of time-series analysis, focuses on identifying the most informative subset of variables for predicting a target variable. This problem’s complexity arises from the high dimensionality and temporal dependencies inherent in multivariate time series. Effective methods must address the challenges of computational cost and the need to avoid misleading results from overfitting or information redundancy. The ideal approach should not only predict accurately but also provide insights into the data’s underlying structure and causal relationships. Scalability is paramount, especially with datasets containing hundreds or thousands of variables. Moreover, the existence of multiple optimal subsets adds further difficulty, necessitating algorithms that can discover and differentiate these alternative solutions for a richer understanding of the system.

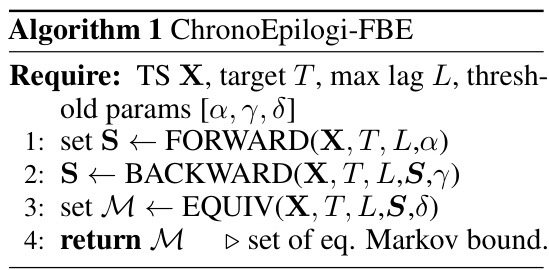

ChronoEpilogi Algorithm#

The ChronoEpilogi algorithm tackles the complex problem of multiple time-series variable selection (MTVS) by efficiently identifying all minimal-size subsets of variables that optimally predict a target variable. Its novelty lies in addressing the limitations of single-solution approaches, which often overlook valuable alternative causal models. The algorithm cleverly leverages the concepts of Compositionality and Interchangeability to ensure both soundness and completeness, meaning it finds all valid solutions without exhaustive search. This is achieved via a two-phase approach (Forward-Backward) and an Equivalence class identification phase, carefully designed to manage computational complexity while preserving accuracy. The algorithm’s scalability and efficiency are highlighted, particularly in comparison to existing methods like Group Lasso, demonstrating its potential for real-world applications involving high-dimensional time-series data.

MTVS: Scalability & Efficacy#

The heading ‘MTVS: Scalability & Efficacy’ suggests an evaluation of the Multiple Time-Series Variable Selection (MTVS) method. A key aspect would be demonstrating scalability, showing the algorithm’s performance with increasing numbers of time series variables. Efficacy would focus on the accuracy and predictive power of the MTVS models compared to existing methods, potentially using metrics like precision, recall, F1-score, and predictive R-squared. The analysis should also consider the trade-off between scalability and efficacy; can the method maintain high accuracy with a large number of variables or does the performance degrade? A comprehensive evaluation should include a range of datasets (synthetic and real-world), demonstrating consistent and robust performance across diverse scenarios. The results should highlight the advantages of the MTVS method in terms of both model performance and its ability to provide multiple optimal solutions, providing deeper insights into the data-generating process.

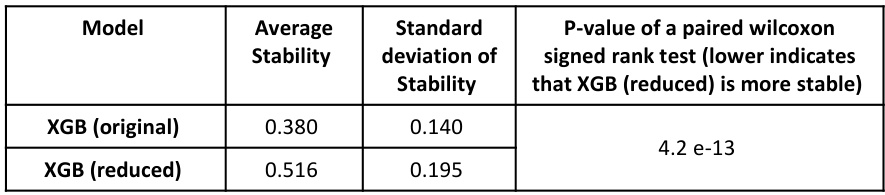

SHAP Explanations & Bias#

The section ‘SHAP Explanations & Bias’ would explore how SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values, used for interpreting model predictions, can be affected by the presence of multiple Markov boundaries in time series data. A key concern would be the instability of SHAP values for informationally equivalent variables, which are interchangeable within optimal forecasting models. The analysis might demonstrate that SHAP values distribute importance among these equivalent variables inconsistently across different data splits, leading to an underestimation of the overall importance of entire equivalent sets. This instability highlights a significant bias in SHAP explanations when dealing with systems containing multiple causal structures, making it unreliable for tasks like feature selection or causal inference. Addressing this bias might involve aggregating SHAP values across all equivalent sets or developing alternative explanation methods specifically designed to handle the inherent uncertainty present in such models.

Future Research: Non-linearity#

Future research into non-linearity within time series variable selection presents exciting avenues. Extending ChronoEpilogi to handle non-linear relationships between variables is crucial, perhaps by incorporating kernel methods or other non-parametric techniques to capture complex dependencies. Investigating the impact of non-linearity on the compositionality and interchangeability assumptions underlying ChronoEpilogi’s soundness and completeness is key. Developing efficient algorithms for identifying multiple Markov boundaries in the presence of non-linearity represents a significant computational challenge. Furthermore, research could explore how non-linear models affect the interpretation of Shapley values and other explainability metrics, addressing the issues highlighted in the paper regarding unstable attributions and potential misleading interpretations. Finally, empirical evaluations on real-world datasets with known non-linear characteristics will be needed to validate any proposed extensions and assess the algorithm’s effectiveness and scalability in practical scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

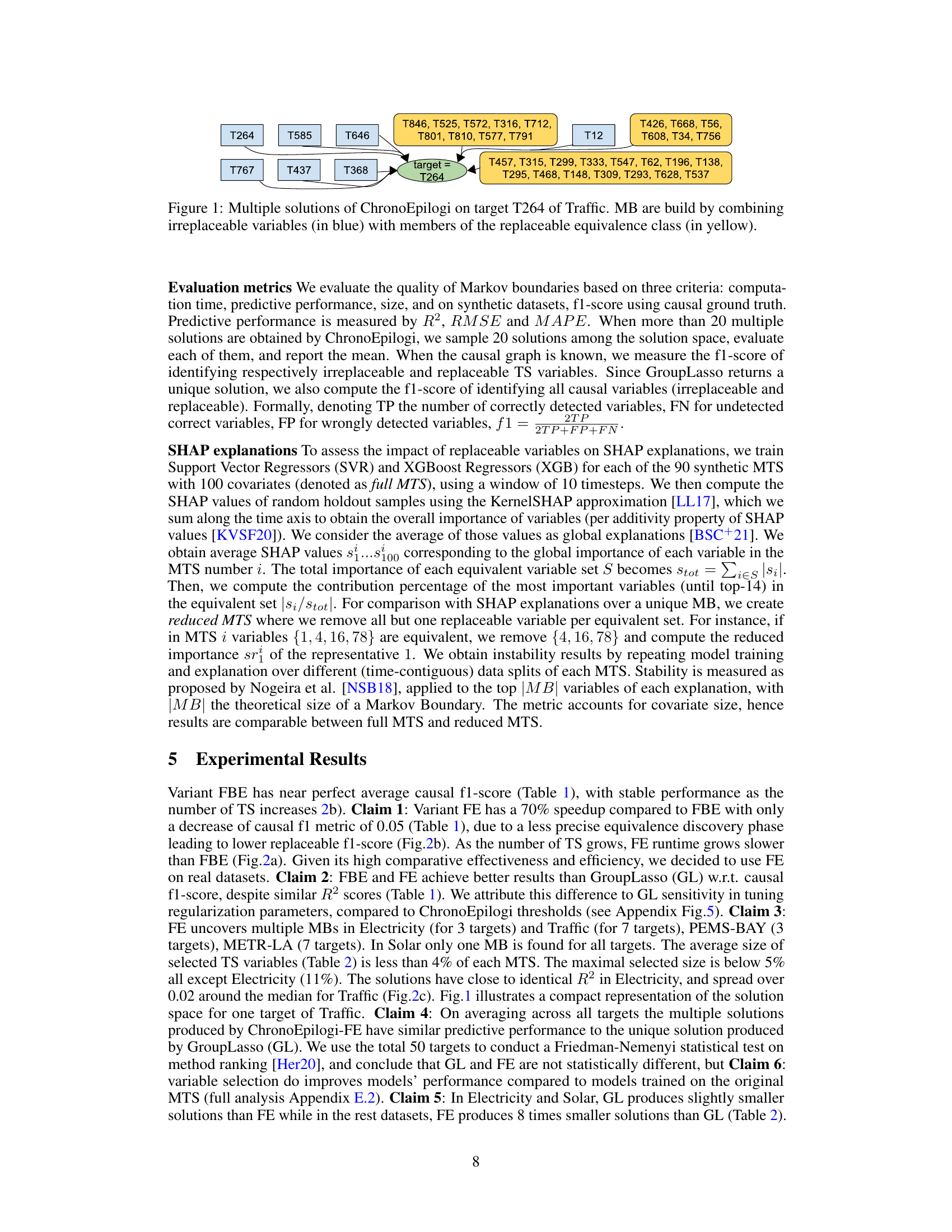

This figure shows an example of multiple solutions found by the ChronoEpilogi algorithm for a specific target variable (T264) in the Traffic dataset. The algorithm identifies multiple minimal-size subsets of variables that are equally effective for predicting the target. The figure visually represents these subsets, highlighting irreplaceable variables (those present in all optimal subsets) in blue and replaceable variables (those that can be substituted within an equivalence class) in yellow. This demonstrates the algorithm’s ability to uncover multiple perspectives on the data-generating mechanism.

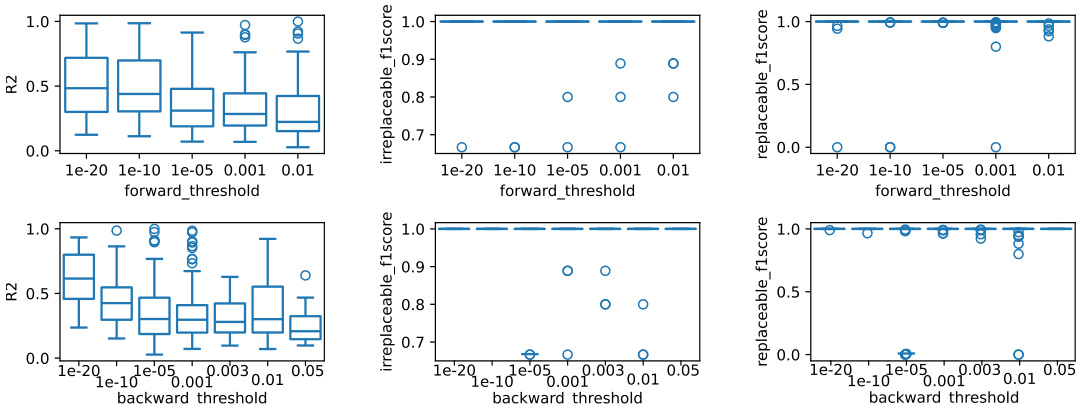

This figure shows how the performance of the FBE algorithm changes depending on the choice of forward and backward thresholds. The three metrics shown are R-squared (R2), F1-score for irreplaceable variables, and F1-score for replaceable variables. Each subplot shows the performance for one threshold while the other is kept constant. It helps determine the optimal threshold values that would produce the best performance of the algorithm.

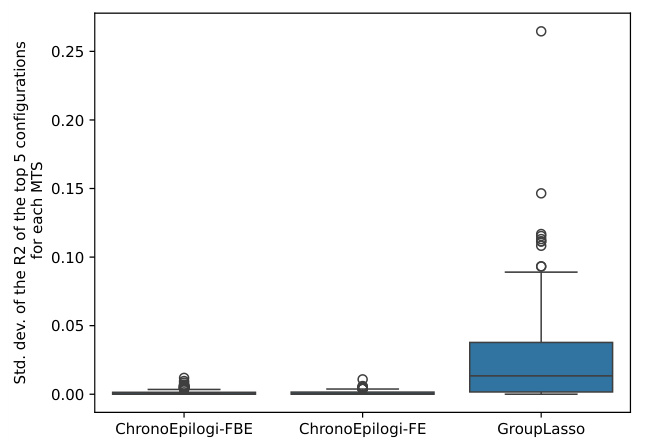

This figure shows the standard deviation of the R-squared values obtained from the top 5 hyperparameter configurations for each of the 270 synthetic multivariate time series (MTS) datasets. The comparison is made between ChronoEpilogi’s Forward-Backward (FBE) version, ChronoEpilogi’s Forward (FE) version, and GroupLasso. The box plot visualization effectively illustrates the variability in R-squared values across different hyperparameter settings for each method. This provides insights into the stability and robustness of each algorithm’s hyperparameter optimization process.

This figure presents the performance comparison of ChronoEpilogi’s two versions (FBE and FE) and Group Lasso in terms of computation time, causal f1-score (for irreplaceable and replaceable variables), and R-squared for both synthetic and real-world datasets. Panel (a) shows the computing time for both algorithms on synthetic datasets with varying numbers of time series (TS). Panel (b) shows the causal f1-scores (irreplaceable and replaceable) for FBE and FE on synthetic datasets. Panel (c) displays the R-squared values obtained by ChronoEpilogi on several real-world datasets, comparing multiple solutions (in boxplots) versus Group Lasso’s single solution (in red dots).

The figure shows the predictive performance (R-squared) of the ChronoEpilogi algorithm on the METR-LA and Traffic datasets. The boxplots illustrate the distribution of R-squared values across multiple runs and targets within each dataset, where multiple Markov Boundaries were identified. The figure highlights that while multiple solutions exist, their number decreases as the number of targets decreases, suggesting a relationship between the complexity of the system and the number of alternative optimal models.

This figure visualizes the PEMS-BAY dataset, overlaying sensor locations (dots) onto the highway and road network of San Jose. The color-coding of the sensors indicates their classification by ChronoEpilogi: green represents the target variable, blue indicates irreplaceable variables essential for prediction, red indicates redundant or irrelevant variables, and orange indicates replaceable variables within the same equivalence class. The spatial proximity of important (blue) sensors to the target (green) aligns with findings from the original LYSL18 paper, suggesting that geographically close sensors are more crucial for accurate prediction.

This figure shows an example of multiple Markov boundaries (MBs) identified by the ChronoEpilogi algorithm for a specific target variable (T264) within the Traffic dataset. Each MB represents a minimal set of variables sufficient for optimal prediction of the target. The figure highlights the concept of informational equivalence: irreplaceable variables (in blue) are essential to all MBs, while replaceable variables (in yellow) can be substituted within an equivalence class, resulting in different, yet equally predictive MBs.

More on tables

This table presents a comparison of the performance of three algorithms: ChronoEpilogi-FBE, ChronoEpilogi-FE, and Group Lasso, on a synthetic dataset consisting of 270 multivariate time series (MTS). The algorithms were evaluated based on their computation time, predictive performance (measured by R-squared), and causal f1-score. The results show that ChronoEpilogi-FE achieves comparable computation times and predictive power to Group Lasso, but with a significant 30% improvement in causal f1-score.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of three algorithms: ChronoEpilogi-FBE, ChronoEpilogi-FE, and Group Lasso on a synthetic dataset of multivariate time series. The comparison includes computation time, predictive performance (R2), the size of the selected Markov boundary (MB size), the number of Markov boundaries found, and the causal f1-score. The results show that ChronoEpilogi-FE achieves comparable computation time and predictive power to Group Lasso while significantly improving the causal f1-score.

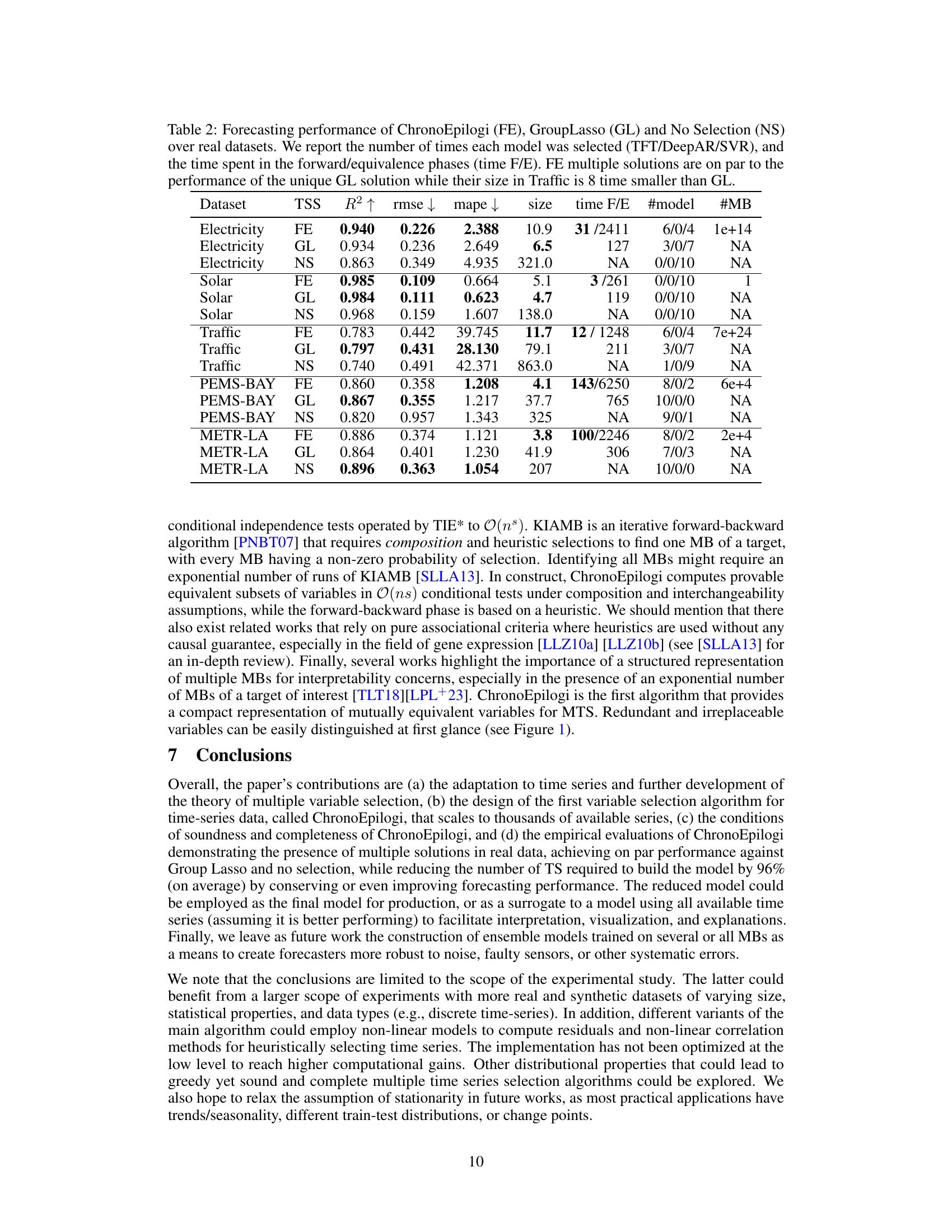

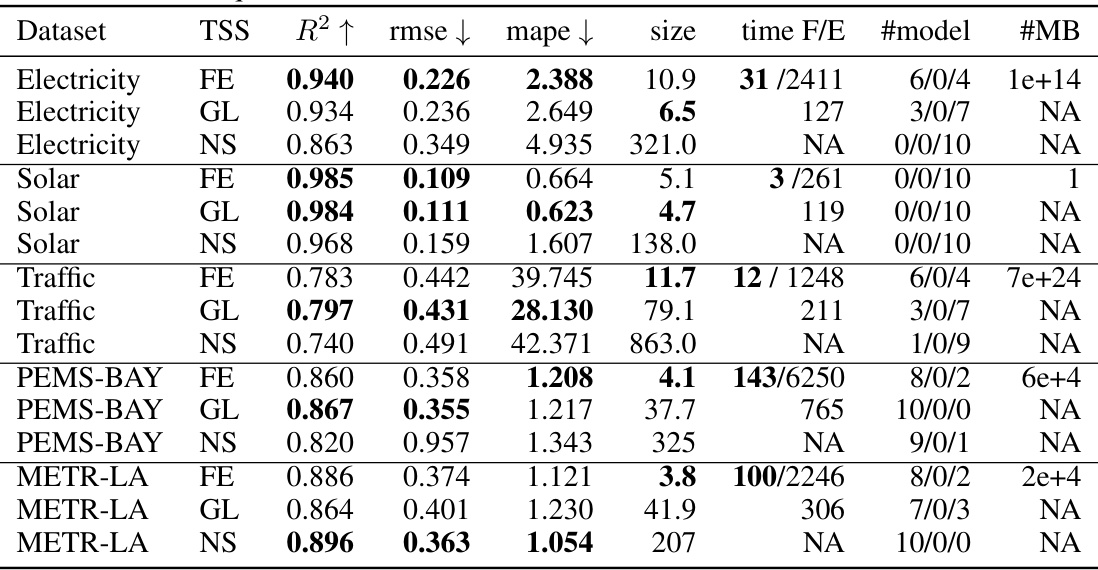

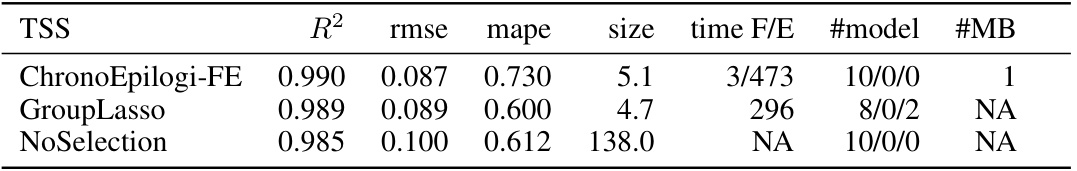

This table presents the performance comparison of three time series forecasting methods on five real-world datasets: Electricity, Solar, Traffic, PEMS-BAY, and METR-LA. The methods compared are ChronoEpilogi (FE), Group Lasso (GL), and No Selection (NS). For each dataset and method, the table shows the R-squared (R2), root mean squared error (rmse), mean absolute percentage error (mape), the number of selected variables (size), the computation time (time), the number of times each forecasting model (TFT, DeepAR, SVR) was selected, and the number of Markov boundaries (#MB) found by ChronoEpilogi. The results demonstrate that ChronoEpilogi achieves comparable predictive performance to Group Lasso while using significantly fewer variables, especially in the Traffic dataset.

This table compares the performance of three algorithms: ChronoEpilogi’s forward-backward (FBE) and forward-only (FE) variants and Group Lasso (GL) on a synthetic dataset of 270 multivariate time series. The comparison includes computation time, predictive performance (measured by R-squared), the average size of the selected variable sets, and the causal f1-score which assesses the ability to identify causal variables. The results show that FE is comparable in terms of speed and predictive accuracy to GL, while significantly improving causal f1-score.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of three algorithms (ChronoEpilogi FBE, ChronoEpilogi FE, and Group Lasso) on a synthetic dataset of multivariate time series. The comparison includes computation time, predictive performance (R2), the size of the selected Markov Boundary (MB), the number of MBs found, and the causal f1-score. The results show that ChronoEpilogi FE achieves comparable computation time and predictive power to Group Lasso, but with a substantially higher causal f1-score, indicating improved accuracy in causal discovery.

This table presents the results of forecasting experiments on five real-world datasets using three different methods for time series variable selection: ChronoEpilogi (FE), Group Lasso (GL), and No Selection (NS). For each dataset and method, it shows the R-squared (R2), root mean squared error (rmse), mean absolute percentage error (mape), the number of selected variables (size), the time taken for the forward and equivalence phases of ChronoEpilogi (time F/E), and the number of times each forecasting model (TFT, DeepAR, or SVR) was chosen as the best model during cross-validation. The table highlights that ChronoEpilogi achieves comparable performance to Group Lasso while significantly reducing the number of selected variables, especially for the Traffic dataset.

This table presents the results of the FBE algorithm on two real-world datasets: Traffic and METR-LA. It compares the performance (R2, rmse, mape) of the FBE algorithm to the FE algorithm and provides metrics such as the number of variables selected (size), computation time (time), and the number of Markov boundaries found (#MB). The results show that FBE generally improves predictive performance compared to FE but at the cost of higher computational time and a slightly larger number of selected variables. This highlights a tradeoff between performance and computational cost.

This table compares the performance of three time series forecasting methods (ChronoEpilogi-FE, GroupLasso, and No Selection) across five real-world datasets. The metrics reported include R-squared (R2), root mean squared error (rmse), mean absolute percentage error (mape), the number of selected variables (size), and the computation time of the ChronoEpilogi algorithm. The number of times each forecasting model (TFT, DeepAR, SVR) was selected and the number of Markov boundaries (#MB) identified by ChronoEpilogi are also listed. Noteworthy is that ChronoEpilogi achieves comparable predictive performance to Group Lasso, but with significantly fewer variables, highlighting its efficiency in variable selection.

This table compares the performance of three time series forecasting models on five real-world datasets. The models are ChronoEpilogi (FE), Group Lasso (GL), and a model with no feature selection (NS). The performance metrics are R-squared (R2), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), and the number of selected time series variables. The table also shows the number of times each forecasting model (TFT, DeepAR, SVR) was selected as the best performing model across multiple cross-validation runs, as well as the time spent on the forward and equivalence phases of ChronoEpilogi. The results show that ChronoEpilogi and Group Lasso achieve similar forecasting accuracy, but ChronoEpilogi selects significantly fewer variables, resulting in much smaller models.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of three different time series forecasting methods on five real-world datasets. The methods compared are ChronoEpilogi (FE), Group Lasso (GL), and No Selection (NS). For each method and dataset, the R-squared, RMSE, MAPE, and size of the selected features are reported, along with the time taken for the forward and equivalence phases of the ChronoEpilogi algorithm and the number of times each forecasting model (TFT, DeepAR, or SVR) was selected. The table highlights that ChronoEpilogi’s multiple solutions achieve comparable performance to the single solution provided by Group Lasso, with significantly smaller feature sets.

Full paper#